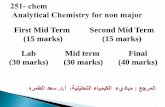

Eadd mid term report 2008 2010

-

Upload

east-africa-dairy-development -

Category

Business

-

view

1.845 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Eadd mid term report 2008 2010

Midterm Report

Milking for Profit

© East Africa Dairy Development 2011 www.eadairy.org

Regional Office Likoni Lane off Dennis Pritt RoadPO Box 74388-00200 Nairobi, KenyaTel: 254 20 3862366/77

Kenya OfficeElgon ViewPO Box 5201-30100, EldoretTel: 254 53 2031273/8

Uganda Office14 Lourdel Road, NakaseroPO Box 28491, KampalaTel: 256 41 4233481

Rwanda OfficeOff Umutara Polytechnic University RoadPO Box 115, NyagatareTel: 250 252 565 432

Writer and Editor Mary Anne Fitzgerald [email protected]

Design and LayoutGeorge Okello [email protected]

Photography East Africa Dairy Development photo library

CommunicationsAnn [email protected]

PrintingOffice and Beyond [email protected]

This report is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

EADD Partners

Introduction

Adopting Business Principles

Kenya

Uganda

Rwanda

More Is Better

The Village Bull

Field Studies

Home at Last

Kenya Banks Pioneer Small Loans to Farmers

Good Feeding Makes Healthy Cows

Bubusi Feed Mill

Reversing the Urban Drift

Corporates Help Expand Dairy Markets

Much in Common

A Town Called Lusozi

Women and Youth to the Fore

Communicating

Keeping Track

1

2

4

5

7

9

12

13

15

15

17

18

21

22

23

24

25

26

28

28

Table of Contents

Acronyms

ABS TCM African Breeders Service Total Cattle Management Ltd.

AHW Animal health worker

AI Artificial insemination

CAHP Community animal health practitioner

EADD East Africa Dairy Development

FSA Financial services association

ICRAF World Agroforestry Center

ILRI International Livestock Research Institute

M&E Monitoring and evaluation

SACCO Savings and credit cooperative organization

UDAMACO Umatara Dairy Marketing Cooperative Union

UN United Nations

UHT Ultra-high temperature processing

Foreword

Africa is a continent of economic promise. This

certainly holds true for the agriculture sector where

investment in small-scale and medium-sized

enterprise is driving rapid economic growth. The

beauty of agriculture is that it is resistant to external

shocks while its benefits reach down to those who are

living on less than $1 a day. And, of course, it feeds

the rest of us.

As Secretary General of the United Nations, Kofi

Annan called for a green revolution in Africa to meet

the Millennium Development Goal of halving hunger

by 2015. The livestock sector, which involves half

the rural population and contributes over 30% of the

continent’s agricultural Gross Domestic Product, is a

major player in this revolution. The dairy sub-sector

is particularly vibrant. In Eastern Africa 15 million

pastoralist and smallholder farmers produce more

than 15 billion liters of milk a year. With the appropriate

policies and healthy investment, its highlands and

savannas have the potential to rival India’s 100 billion

liter annual production. This would make the continent

self-sufficient in milk, save foreign exchange and shift

wealth to the rural areas. It is possible.

Inspired and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates

Foundation, a consortium of five partners with a long

history of supporting dairy production and marketing

in Africa joined together in 2008 to form the East

Africa Dairy Development Project (EADD). The idea

was to add value to farmers’ milk production through

producer-driven collective marketing and production

based on efficient, farmer-friendly technology. Three

years on, EADD has become one of the leading

market-oriented agro-livestock development initiatives

in Africa. Its 140,000 farming-family beneficiaries have

invested $3 million and receive some US$ 24 million

a year in incremental payments. Thanks to EADD,

68 farmer-owned cooperatives and companies have

either been formed or resuscitated. Nearly 20 SACCOs

and Village Banks have been established as well.

Today, halfway through EADD’s Phase 1 (2008-

2012), rural families in Central Uganda, Eastern

Rwanda and selected districts in Kenya can afford

to educate their children, enjoy basic banking

services, and buy farm inputs and services with

credit or cash. The continued success of about 70

producer enterprises subscribed to by thousands of

farming families will depend on sound governance and

management, modern technology, market expansion

and the continued availability of support services and

inputs. These vital ingredients need time to take root in

rural Africa.

The EADD consortium is in the process of putting

together a proposal for Phase 2 of EADD running from

2012 – 2017. This will see EADD expand its reach to

over 650,000 farming families in five countries - Kenya,

Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania and Ethiopia - through an

ambitious public-private partnership. We hope you will

join us in helping our vision come to fruition.

Moses NyabilaEADD Regional Director

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

EADD Partners

1

Heifer International

As the lead agency in the EADD consortium, Heifer

International holds primary responsibility for improving dairy

productivity and efficiency. It draws on experience in East

Africa dating back to the early 1980s when the organization

first provided support to rural farmers in Kenya and Uganda.

Heifer International manages the project as part of its Africa

Area Program and provides financial and programmatic

guidance as needed for overall coordination of the

implementing partners.

African Breeders Service Total Cattle Management Ltd.

(ABS TCM)

ABS TCM is a private, for-profit supplier of technical

assistance related to livestock breeding. It supports Heifer

International through the promotion of enhanced animal

breeding for increased dairy productivity within EADD project

areas. ABS TCM brings to the consortium a range of facilities

and expertise including livestock genetic delivery service,

liquid nitrogen production, capacity building related to milk

quality and livestock reproductive health and nutrition. As

a private partner, ABS TCM is committed to the promotion

of productivity-enhancing technologies and the creation of

viable business linkages in dairy value chains.

TechnoServe

TechnoServe leads the EADD consortium on market access

activities which include the procurement and financing of

chilling plants as well as technical support to traditional

market hubs and business development service providers.

It is considered a pioneer in private-enterprise approaches

to poverty alleviation in the developing world. In Africa,

TechnoServe maintains country offices in Kenya, Uganda,

Rwanda, Tanzania, Swaziland, Mozambique, South Africa

and Ghana. World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF)

ICRAF supports Heifer International by promoting the

production and distribution of improved animal feed and

fodder through farmer training on the production and

processing of improved feeds and the establishment of feed

demonstration plots. ICRAF ialso carries out research related

to feeds and promotes improved feed conservation such as

crop residue and storage.

International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)

ILRI is charged with leading the consortium on knowledge-

based learning activities and provides action research

to inform the implementation of EADD project activities.

ILRI involvement in EADD focuses on the documentation

of innovation and research related to dairy production;

knowledge sharing among partners; and informing project

design.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

Introduction

EADD will double the dairy income of 179,000 farming families by 2012

2

Kenya

110,000Rwanda

24,000Uganda

45,000

On a verdant hillside in Rwanda an illiterate genocide

survivor has leveraged the gift of a cow into three

micro-enterprises that bring in $635 a month. At a

bustling milk collection center a 27-year-old school

leaver loads metal canisters of milk onto the back

of a motorbike. Through an initial bank loan, he

has acquired three shop sites, his motorbike and a

crossbreed Friesian cow. His long-term vision is to

build his own milk-chilling plant. A headmistress in

Uganda, who is also chair of the board for the local

chilling plant, reports that student intake has swelled

and parents no longer default on fees.

Subsidized loans and micro-credit linked to

donor funding have been cited as cornerstones for

transforming Africa’s impoverished smallholders

into prosperous commercial farmers. In fact, some

agriculture experts say that every dollar lent leverages

twenty more in private capital. Obvious as it may seem

as an exit from poverty, access to credit has eluded

Africa’s farmers for generations. Similarly, smallholder

farmers are seldom taken seriously as budding

entrepreneurs.

As a result, the majority of rural households in East

Africa continue to scratch a living from subsistence

agriculture. Many keep local cows which typically

produce less than two liters of milk a day. Parents find

it hard to put enough food on the table, send their

children to school or pay for medicine when they get

sick. Although women do about 70% of the work in

the fields, gender disparity persists thus preventing

their advancement. Hopelessness propels young

people to join the ranks of the unemployed in the

cities.

It is against this background that the East Africa

Dairy Development Project (EADD) has introduced a

dairy model on a rare scale. It is an innovative mix of

training, technology, access to markets and supply-

side economics that puts the farmer in control of the

dairy-value chain from production to processor.

EADD takes farmers and their ambition to improve

their quality of life very seriously indeed. It intends to

double the income of more than 600,000 dairy-farming

families (nearly 4 million people) over the course of 10

years. Phase 1 (2008 – 2012) is a pilot project covering

179,000 subsistence farmers in selected districts of

Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. The methodologies that

are being tested will inform the second part of the

project.

Phase 2 (2012 – 2017) will extend the best practices

learned to another 500,000 farmers in Ethiopia and

Tanzania as well as the existing countries of operation.

After that, the assumption is that EADD’s technically

competent and business savvy farmers will be on

a financially sound footing and able to look after

themselves.

The EADD project has been designed and is being

run by a consortium of five internationally known

partners with a unique selling point. They have

pooled their technical, business and research skills

to lay the foundations for a sustainable and profitable

regional dairy sector driven by millions of farmers

who once lived below the poverty line. In addition,

EADD Operational Areas Phase 1 (2008 – 2012)

141,000Farmers registered and organized

into associations and groups

3,578Dairy Management Groups and

Dairy Investment Groups

$3,000,000Invested in chilling plants and

milk-collection centers

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

3

Farmers will be a major voice in what affects the industry. The EADD experience has stabilized prices in the marketplace to shift the balance of power dramatically from the processor to the farmer. Within the next five years farmers will be processing their own milk or at least going into partnership. Free enterprise in agriculture works.

Moses Nyabila Regional Director, EADD

EADD specifically targets women and youth. More

than 90% of adults in the households of EADD project

participants earn less than $2 a day. It is funded by

a $42.85 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates

Foundation. Part of the Foundation grant is a $2.5

million investment fund for Dairy Farmers’ Business

Associations, which was increased to $5 million in

2008 thanks to a Heifer International fundraising

campaign.

To date EADD has mobilized $3 million of

investment to build 22 new chilling plants, revitalize 13

existing ones and create 12 milk-collection centers for

the traditional market. Combined with the processor-

owned chilling plants used by some of EADD’s

farmers, EADD has 54 dairy hubs across the region.

Milk intake at dairy hubs has grown significantly

in Kenya (65%), Uganda (30%) and Rwanda (10%).

Microfinance associations, village banks, commercial

banks and the chilling plants’ check-off system of

credit against milk deliveries has given farmers,

youthful entrepreneurs and business men and women

the opportunity to engage in a range of enterprises

that extend well beyond the dairy sector. This has

in turn stimulated the local economies of hamlets,

trading centers and towns all over East Africa.

The project is coordinated by a regional team,

three country project teams, a Regional Advisory

Committee and a Project Steering Committee, each of

which maintains multi-partner representation. EADD

has also created direct roles for private dairy interests

and relevant government agencies in oversight of the

project. It works closely with government officials from

local to national level and ensures that all its activities

are aligned with government policy.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

4

Adopting Business Principles

An expanding dairy industry requires access to

markets, extension services, farmer training and credit

for business start-ups. But the operating environments

in East Africa are exceptionally diverse. It is not a case

of one size fits all. One of EADD’s great strengths

is its flexibility in adapting the paradigm to suit the

situation. Kenya, where the dairy industry is well

established, operates on volume. Twenty-one chilling

plants have been constructed so far with a minimum

of 2,000 members registered at each plant. Return on

investment is one year.

In Uganda, where sites are predominantly in

pastoralist areas, the return can take up to two years

and the volumes per chilling plant are lower. With

per capita income lower too and a slow response

to turnkey financing from commercial banks, EADD

has pre-financed the procurement of equipment in

some of the chilling plants so that construction can

begin. Rwanda has a significantly smaller market and

no culture of milk consumption. EADD works closely

with the government’s dairy industry and is looking at

cultivating the traditional market which means a new

focus on milk-collection and bulking centers.

The axis of the EADD project design is the dairy

hub which is used to deliver a comprehensive

package of services including artificial insemination

(AI), veterinary care and animal husbandry. The hub

is managed by Dairy Farmers’ Business Associations

and promotes Business Development Services

such as transporting milk, agrovet stores and the

commercial growing of fodder. Training, exchange

visits, demonstration plots and manuals reinforce the

farmers’ understanding of how to improve milk quality

and quantity.

The centralization of AI service providers,

Community Animal Health Practitioners and agrovets

at dairy hubs is popular with farmers. The fact that

they can buy on credit against a check-off system

stimulates consumer demand. And it gives farmers the

latitude to buy products and services when they need

them rather than when they can afford them. Chilling

plants also offer organoleptic and milk-density tests so

that milk quality meets the processors’ benchmark.

EADD uses a stage-gating system to chart the

progress of each chilling plant from inception at

Stage 1 to disengagement from EADD at Stage 5. By

Stage 4 chilling plants and Dairy Farmers’ Business

Associations are profitable, offer a range of extension

services and pay regularly to ensure their members will

continue to supply large quantities of milk. And chilling

plants offer value to buyers as they can guarantee

quality and quantity.

Governance is a key aspect that is weighted at

about 40% in the stage-gating. With training facilitated

by EADD advisers, corporate governance respects the

separation of board and management, holds regular

elections and returns clean audits.

‘The philosophy is that you can only support

to a certain point. Then we shift our resources to

other farmers. It’s about exit and sustainability and

empowerment. This year a number of Dairy Farmers’

Business Associations will have moved to Stage 4,’

explains Moses Nyabila.

EADD also fosters relationships with training

institutions to create a body of graduates that

will form the critical mass of skills required for the

implementation of Phase 2. Canada’s Coady Institute,

a center of excellence for community development

established by St. Francis Xavier University, offers

scholarships to management, board members and

EADD staff. EADD is currently developing curricula

with African universities.

When EADD started its project in Kenya in 2008,

it was clear to the country team that farmers were

not accruing any substantial benefits from the dairy

value chain. The collapse in 1999 of the state-owned

processor, Kenya Cooperative Creameries, had

opened up the sector to competition but industry

capacity utilization was a low 40%. Despite this, the

farm-gate price was weak and varied little between the

formal and informal markets. Farmers were not being

paid on time in the informal market and sometimes not

at all. The formal market, dominated by three major

processors, was more regular in its business dealings.

However, 80% of farmers favored the traders’ and

hawkers’ cash-based system that catered to their daily

financial needs. The delivery of extension services no

longer functioned properly. Neither were farmers able

to access information on husbandry, markets and

prices.

To ensure sustainability and profitability, the

Kenya team mobilized farmers to form public liability

companies that could operate on cooperative

principles. In its first three years of operation, EADD

established or revitalized 19 chilling plants. In 2010

they sold 49 million liters of milk, earning farmers

$13.7 million with net profits for the chilling plants

of more than $0.5 million. A further three plants are

scheduled to come on stream in 2011.

The EADD goal for its Kenya program is to double

the income of 110,000 impoverished dairy farming

families in the Rift Valley and Central Provinces where

dairy production is concentrated. Kenyan smallholders

sold an average of 3 to 5 liters of milk a day. Low

production meant low income which prevented

investment in feeds and breeds to boost yields. It

would need a minimum of 15 liters a day for families to

break out of the poverty that encircled them.

The same thinking applied to the chilling plants.

They had to run at capacity to cover debt obligations

and operating costs so volume was essential. The

challenge was to keep the chilling plants functioning

with an eye to the bottom line without sacrificing

benefits to farmers. Services to farmers instilled loyalty

which, in turn, created volume at the chilling plant.

The team concluded that in order to lift smallholders

out of subsistence farming, they had to design a

program based on business principles with profitability

driven by volume. The target was to sign up 2,000

farmers at every Dairy Farmers’ Business Association

to feed milk into each chilling plant’s 10,000-liter tank.

A feasibility study showed that both farmers and

processors suffered from the consequences of a poor

cold chain. Milk needs to be cooled within two to

four hours of being poured into the can or the quality

drops. It also revealed that Kenyan smallholders did

not adhere to best practices. They did not use AI or

fodder while preventive health care was minimal. And

farmers did not know the cost of their production or

if additional feed or a change in diet would boost a

cow’s milk yield.

By 2010 this had been dramatically turned around

with 68,000 farmers trained in better husbandry. At the

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

5

Kenya

Model farmer from Ol Kalou, Kenya.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

6

Nyala Dairy in Kenya

By the close of 2010, the average monthly profit

for chilling plants was $1,300 while just under $2

million was paid out to farmers. All the loss-making

chilling plants that had been taken up by EADD at

the time of its entry were now profitable.

same time, the Kenya project had registered more than

90,000 farmers, reaching 80% of the Phase 1 target.

Households were producing an average of 15 liters of

milk a day. And farmers were earning $4,500 a year

from the sale of milk and heifers.

EADD uses a financing model for raising plant

capital that is suited to Kenya’s well established dairy

industry. Farmers raise 10% of the $125,000 start-up

capital to create ownership and accountability. EADD

extends a 30% interest-free bridging loan redeemed

over five years by the chilling plant shareholders

through a minimal levy on every liter of milk sold. The

balance is covered by commercial debt.

Farmers exceeded their minimum equity targets.

However the operating environment in Kenya’s

banking sector did not lend itself to backing unproven

agriculture ventures. Calling on the flexibility and

innovative thinking that untried paradigms require,

EADD assumed responsibility for the outstanding

60% of the financing. It extended loans through its

investment fund on the premise that once chilling

plants demonstrated their profitability, commercial

banks would take over.

This assumption proved to be correct. Chilling

plants have been seeing an exceptionally rapid

return on investment. In April 2010, Kabiyet Dairies

Co. Ltd. was granted a commercial bank loan on

the basis of an $8,750 monthly turnover one year

after being commissioned. Now banks are vying for

chilling plant business at competitive interest rates in

acknowledgment of the potential demonstrated by

their start-up track record. Currently six commercial

banks – CFC-Stanbic, Cooperative Bank, Family Bank,

Fina Bank, K-Rep Development Agency and Kenya

Commercial Bank – are in various stages of financing

or refinancing chilling plants and equipment such as

motorbikes. The plants at Kabiyet, Lelan and Metkei

have secured commercial loans exceeding $335,000

at an average interest rate of 12%.

This year EADD is partnering with the Kenya

Institute of Management to develop an operational

performance award for hub management sustainability

and to rank chilling plant companies in terms of

profitability and corporate governance. This will

provide banks with a yardstick against which they can

assess a plant’s credit rating. The concept is being

replicated in Rwanda and Uganda.

In 2010 the Kenya team strengthened its data

system for tracking progress measured against project

milestones. Seventeen databases were installed at

chilling plants and connected to a master database at

the country office in Eldoret. Stored data include the

training records of farmers and statistics on registered

cows and all crossbred calves.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

7

In Uganda, EADD is doubling the income of 45,000

families by applying integrated interventions in dairy

production, market access and knowledge application.

The project area is in central Uganda, a region that

accounts for nearly 25% of national milk production.

Many of the selected sites are comparatively arid and

are inhabited by pastoralists.

Uganda’s nascent dairy sector presented challenges

that had not been encountered by Kenya’s longer

established dairy industry. Smallholders owned more

than 90% of the national herd. This consisted almost

entirely of native Zebu and Ankole which had been

bred with an emphasis on beef. Their milk yields

averaged a liter a day. Further complicating matters,

the areas initially chosen for the construction of chilling

plants tended to have a low population density and

were not well served with feeder roads.

Farmers were carrying their milk by foot and on

bicycle for distances of up to 30 kilometers. Because

volumes were low, especially in the dry season, the

milk could sit for three or four days at a collection

center before being trucked to a chilling plant.

While the market potential existed, it had not been

developed. About 90% of Uganda’s milk production

was sold informally to hotels, shops and independent

traders because the formal market, dominated by a

virtual monopoly, fetched lower prices.

EADD’s success was premised on high volumes in a

competitive marketplace. However, the Uganda team

soon realized that they would have to recalibrate the

EADD program design that had been so successfully

applied in Kenya if they were to achieve results.

The team halved the size of the chilling tanks to

5,000 liters to reflect the lower site volumes and

doubled the number of sites from 15 to 31 to widen

the net of farmer involvement. Today EADD works

with 10 chilling plants that are owned and managed

by farmers. The milk is bulked and chilled before

collection by commercial processors. Another seven

chilling plants are owned by processors and rented out

to farmers.

In Uganda traders handle 80% of all marketed

unprocessed milk. EADD has penetrated this vibrant

market by working with 14 traditional hubs that collect

milk for sale in the informal market. The majority of

farmers assisted by EADD are connected to these

traditional hubs. EADD helps to leverage their position

with raw-milk traders through collective bargaining and

Uganda

Girl carrying fodder

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

8

by stimulating the demand for quality milk. Although

they do not utilize EADD-procured chilling plants,

traditional market hubs are similar to chilling plant

hubs in that they are managed by Dairy Farmers’

Business Associations and provide dairy-related

Business Development Services.

By midterm, despite a slower than anticipated start-

up, the project’s key milestones had been achieved

ahead of schedule. More than 30,000 farmers (68%

of the end-project total) had signed up as members

of dairy hub cooperatives while 41,000 farmers were

already accessing EADD’s Business Development

Services. They reported improved milk yields and

attributed it to better bred and fed cows that were

healthy as a result of good husbandry.

Several achievements were highlighted as

exceptional in an independent evaluation conducted

mid-2010. EADD was instrumental in creating a

substantial growth in milk production and milk intake

at the chilling plants. The technical advice of EADD’s

business managers also helped to raise farm-gate

prices by creating competition in the formal and

informal markets.

By stimulating the industry and expanding farmer

profit margins, EADD had demonstrated to farmers

that investing in dairy improvements was worthwhile.

This was the tipping point needed to persuade

farmers to replace their locally bred Ankole and Zebu

cows with crossbred or purebred cows. The midterm

evaluation showed that the most striking difference

between EADD farmers and the farmers outside the

catchment area was the adoption of AI practice. One

out of two EADD farmers have herds where at least

half the cows are exotics compared to one out of five

farmers living outside the catchment area.

Farmers cite training in farming and business

skills, exchange visits with other farmers, and

timely and convenient payments for milk delivered

as the primary attraction for being a member of a

chilling plant cooperative. Already 4,250 farmers

have been on learning trips and have introduced

best practices on their farms. The other incentives

for cooperative membership are the Dairy Farmers’

Business Associations that link farmers to stable

markets, SACCOs (savings and credit cooperative

organizations), and dairy-related goods and services.

Farmers say they like the products on offer such as

high quality feeds, veterinary products and genetically

improved semen.

Farmers were reluctant to form companies so EADD

chose to work through cooperatives instead. It was

a way of organizing that was familiar to Ugandans.

EADD then formed about a dozen 30-member Dairy

Interest Groups at each site to enable farmers to

collectively access dairy-related services and to

market milk. Uganda pioneered a decentralized

structure that has been replicated across the region.

It is based on a devolved cluster concept that has

improved the efficiency of project implementation.

The extension-service system has been revitalized

by centralizing the extension workers at the hub sites

from where they can adapt feeding and breeding

strategies to each cluster’s unique needs.

An EADD business adviser is attached to each hub

to help formulate and implement a business plan.

Advisers, who serve as ex-officio board members, Farmers in Wakiso being trained in milk testing and grading

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

9

also facilitate the training of board members and

management staff in sound corporate and financial

practice. Operational plans and budgets, facilitated

by Deloitte, are participatory and informed from the

bottom up by the cluster teams. Generic business

plans for the Dairy Farmers’ Business Associations

have been revised into site-specific, concise

documents pitched to farmers and funders using

annual implementation plans and EADD action plans.

In March 2011, EADD entered into an agreement

with the Microfinance Support Center to extend

loans for the construction of chilling plants at the

concessionary rate of 9%, which compares favorably

to the commercial rate of 25%.

EADD also works closely with the government

through the Dairy Development Authority to align its

dairy hub model with national policy and strategies.

EADD is helping to upgrade the Entebbe Dairy Training

School to ensure the long-term continuation of

vocational and outreach training.

EADD’s future strategy for Uganda is to continue

to think small. Government policy prohibits the bulk

transportation of warm milk for distances greater than

50 kilometers. As the market expands, EADD will

assist with the construction of chilling plants, many

of them satellites to established chilling plants, with a

tank capacity of 1,000 to 2,000 liters.

Rwanda’s hilly topography and good rainfall have

earned it the sobriquet, the Switzerland of Africa. It

is also one of the most densely populated countries

on the continent with more than half the population

living below the poverty line. The EADD target is

to transform the lives of 24,000 families by helping

them to exit poverty. EADD works closely with the

Government of Rwanda to achieve its goals for the

growth of the dairy industry.

The EADD Rwanda country office was opened in

Nyagatare District in May 2008, prior to a feasibility

study conducted in September and October of that

year. As a result, site selection and the formulation of

a business plan were carried out simultaneously with

farmer sensitization and mobilization. In 2009, EADD

expanded its presence to two more districts, Gatsibo

and Rwamagana.

The program design for Phase 1 was to establish

10 new chilling plants. Initially, however, EADD took

on six existing chilling plants. During the first half

of the project, until it was disbanded, access to the

cooperatives that owned the chilling plants was

through UDAMACO, an umbrella organization for 23

local cooperatives. Early on in its engagement EADD

seconded a consultant to UDAMACO to assist it in

writing a 10-year strategic plan.

At the time of EADD’s entry, the dairy industry

was still in its early stages but had been given a

boost through a government program initiated in

2006 to give a cow to every smallholder homestead.

About half the milk produced was either consumed

domestically or lost along the production chain.

Almost all the rest was sold in the informal market as

few Rwandans could afford packaged milk.

Rwanda

When you talk to a farmer, he doesn’t want to know

your institutional affiliation. He wants to know how

you can help him. Before EADD came along, milk was being wasted. Now chilling plants receive over

1,000,000 liters a month. It’s changing the face of the villages.

William MatovuUganda Country Program Manager

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

10

Where milk collection centers existed, they operated

on a slim margin that was vulnerable to rainy season

milk gluts. The centers either owned milk shops or

relied on transporters who sold to their own buyers.

Annual per capita milk consumption was 12 liters

compared to 100 liters for Kenya and 22 liters for

Uganda.

Milk yields were very low as more than half the

milking cattle were local breeds and nutrition was

inadequate. Cows fed almost exclusively on grass,

a fodder source that was entirely dependent on the

weather. As a result, prices fluctuated considerably

between the rainy and dry seasons making it

impossible for a farmer to budget on an annual basis.

In addition, they were difficult to find in stores outside

Kigali, and farmers had little knowledge of their

application.

Weak consumer demand was a key challenge. The

dairy hub model is based on the premise that incomes

double when farmers use their credit to access

services that improve their lives. But if farmers have

limited milk sales, this does not happen.

Penetration into the formal market was very limited

as Rwanda’s two processors were operating on low

capacity. So EADD’s Rwanda team changed tack. It

took a serious look at the traditional market, which

is led by milk bars where local fast food is served

alongside one-liter mugs of milk. Other outlets

included hotels and a government school feeding

scheme that is facilitated by the UN’s World Food

Program. In the absence of reliable data on retail

outlets and consumer habits, Tetra Pak agreed to

co-sponsor consumer research to ascertain consumer

segments, household milk-buying patterns and milk’s

penetration and distribution in the cold chain.

The recalibrated marketing approach placed a new

emphasis on the importance of collection centers

where milk is bulked but not necessarily chilled. The

lessons learned were twofold. First, during the start-

up phase in countries where the dairy industry is not

yet entrenched, consumer demand may have to be

ramped up in order to stimulate farm supply. Second,

chilling plants are not essential to the dairy hub model.

Dairy hubs are a channel for accessing credit and

associated services regardless of how and where the

bulked milk is sold.

EADD also had to conform its financing package

to the government model for turnkey chilling

plants. At a uniform cost of about $55,000, farmers

contribute 18% of the equity. The Government of

Rwanda contributes 40% in the form of land and

funding. EADD extends an interest-free loan of 21%

which is matched by a low-interest loan from the

Rwanda Development Bank, the state investment

arm for development financing. In another divergence

The daily trip to chilling plants can be up to 2o kms

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

11

from EADD’s investment blueprint, the Rwanda

Development Bank is responsible for the tendering,

procurement and installation of equipment. Despite

the concessionary terms, farmers struggle to raise the

equity. After three years, only two sites have achieved

fully paid-up farmers’ equity.

Initially, farmers were slow to buy in to the EADD

concept of commercializing the dairy sector. They

were accustomed to organizing in cooperatives

and receiving equipment and services from the

government. Even so, by the end of 2010, the third

year of operation, farmers had responded to the

new technology with the result that productivity had

increased significantly.

The Government of Rwanda continued to give

EADD its full support and contributed AI equipment,

seed, biogas digesters and financing to the project. It

also acknowledged that the project’s training, technical

support and services had already transformed milk

production from a household sideline to a profitable

business that had raised the living standards of

smallholders over a very short period of time. This

was evidenced by a significant improvement in milk

production and milk quality. The best performing

business indicator for 2010 was the value of milk sales

from farmers at $1.38 million, a jump of 70% over the

previous year.

Other indicators also reflected an enthusiastic

response on the part of farmers to EADD interventions

such as AI. EADD’s farmer-to-farmer approach to

training and information dissemination proved to

be extremely popular. More than 90% of registered

farmers undertook some form of training, a

considerably higher uptake than in Uganda (75%) and

Kenya (55%). Veterinary inputs and AI ranked second

and third respectively in farmer demand for services

and inputs.

By the start of calendar year 2011, 10 existing

chilling plants had been rehabilitated and were making

a modest profit. More than 20,000 farmers had

registered at 16 sites which was more than 85% of the

four-year project target. EADD had also established

13 satellite centers to accommodate the farmers who

lived long distances from chilling plants. These centers

are equipped with pulverizers to convert crop residue

into improved feed. Seven sites have become properly

functioning hubs that offer three or more services to

nearly 17,000 members. They range from AI, agrovets,

tractor hire and plowing services to pulverizers for rent

and mobile phone charging.

Since the intervention of EADD, all chilling plants

have seen a modest increase in their profits. And

business indicators have all exceeded their annual

targets. In 2010 7,400 farmers were trained in

governance and group dynamics to enable them to be

knowledgeably involved members of Dairy Farmers’

Business Associations. About 70% were women and

young people. Nineteen farming families pioneered a

pilot domestic biogas project initiated in conjunction

with the Ministry of Infrastructure. Three chilling plants

won tenders to supply schools with milk as part of the

school feeding scheme.

Pouring milk into a cooling tank

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

12

Farmers attend a meeting

They arrive amid shouts and the groan and wheeze

of revving engines. It is 8 a.m. and Kabiyet town, set

at 2,000 meters atop a grassland plateau in Kenya’s

Rift Valley Province, is alive with noise and movement.

Donkey carts, bicycles, motorbikes, minivans and

pickups vie for space on the dirt forecourt of Kabiyet

Dairies as gum-booted transporters unload a

seemingly endless stream of metal churns brimming

with milk.

North Keiyo District has long been in the heartland

of Kenyan dairy production. But when Kenya

Cooperative Creameries, a state-owned processing

monopoly, was declared bankrupt in 1999, the local

dairy industry virtually collapsed. Farmers turned

elsewhere to sell their milk but lacked bargaining

power and were hostage to discriminatory prices.

Many switched to maize growing and saw their

lifestyle deteriorate. School fees went unpaid. People

walked barefoot or in sandals made from discarded

car tires. Cattle dips closed and East Coast Fever was

rampant. The building where milk was collected and

bulked was boarded up and fell into disrepair.

Then EADD agreed to assist with the renovation of

the abandoned collection center. Five months after

Kabiyet Dairies Co. Ltd. was registered in January

2009, the plant was commissioned. The first day it

cooled 1,623 liters of milk. The next day it was 2,223

liters and by the end of the month more than 7,000

liters. The momentum was unstoppable.

By January 2010, a year after company registration,

the plant was receiving 37,000 liters a day and farmers

were subscribing to AI services to switch from their

traditional longhorns to high-yielding Holsteins. It

had taken just a year and a half for the dairy hub to

become a successful, farmer-owned chilling plant

poised to exit the EADD project and operate as a

profitable stand-alone business.

The Kabiyet experience is not only a success

story, it underscores the impact the EADD volume-

driven program design has on communities. The

number of shops has more than doubled. There are

More Is Better

8%Net profit margin

$2,800,000Sales revenue generated by

3,500 farmers

$368,000Monthly turnover

Kabiyet Dairies Co Ltd performance in 2010

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

13

three petrol stations (compared to the previous one)

to cater for all the newly acquired vehicles. Monthly

turnover at Kabiyet Dairies’ agrovet store is $7,500.

General trading stores are selling 200 kilos of sugar

a day instead 25 kilos. School intake has grown by

more than 35%. Fee arrears have dropped 80%

thanks to the Kabiyet Financial Services Association

which uses the check-off system to advance parents

school fees against milk deliveries. Cases of theft and

disturbances dropped from 116 to 49 over the course

of a year.

In Kenya volume has been attainable even in poorer

communities with a per capita income of less than

$1 a day. At Metkei, one of EADD’s first site choices,

four cooperatives joined together to form a limited

company which attracted 2,000 shareholders. Paying

the $8.75 share price was challenging, but it was

achieved in installments. At the time of EADD’s entry,

the local cows were typically yielding three cups of

milk a day. Now daily yields average seven liters. The

plant has 3,500 regular suppliers who generated a

revenue of $1.85 million in 2010.

The root of our success is that we demystify

innovations. We involve the farmers in whatever we do, and they give us feedback. We are a single, holistic entity.

Ken Biwott Manager, Metkei Multipurpose Co Ltd

The first step in attaining high-yielding milk production

is to own the right breed of cow. East Africa’s

indigenous cattle are hardy and resistant to local

diseases, adapted to survival even without good

husbandry. But they have never been prodigious

milk producers. EADD’s country feasibility studies

showed that the milk output was almost universally

low. Typically a cow produced less than two liters a

day. Based on existing herds, farmers would need

to own more than 100 cows to increase their income

through the sale of surplus milk. Yet large herds require

extensive pasture and lots of water. Neither resource

was easily available. There had to be another solution.

The starting point for EADD’s program in the first

year of implementation was to talk to farmers about

why they should consider changing the profile of

their herds. Small was better. Genetically improved

was better still. Crossbreeding with exotics such as

Friesians, Holsteins, Ayrshires and Jerseys allows

farmers to reduce the size of their herds dramatically

while improving the output of milk.

The way to do this efficiently and on a large scale is

through AI. Traditionally farmers used natural breeding

through the services of a few local bulls. It did little

to improve the quality of the animals. AI, on the other

hand, is a technology that allows farmers to meet their

breeding goals by introducing quality genetics from

performance-tested bulls.

In the first two years of project implementation,

AI service providers had performed nearly 120,000

inseminations, about half of them through EADD-

funded chilling plants. While past records show that

breeds are improved by crossing local cows with

exotic quality bulls, It takes five to 10 years for AI

to make its full impact on household incomes. By

midterm of the project’s Phase 1, crossbred cows

constituted at least half of the herds belonging to

The Village Bull

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

14

more than 95% of beneficiary farmers, according to

an external evaluation. And farmers had been trained

in keeping breeding records for animal passports and

traceability.

At first EADD staff seconded from ABS TCM

encountered resistance among some farmers, who

were reluctant to sell their prized bulls. Farmer

education forums, the distribution of educational

material and the experience of model farmers who

were already using AI gradually persuaded the

skeptics to switch methods. With AI now an intrinsic

aspect of local dairy culture, the straws of semen

provided by EADD’s AI technicians are known as ‘the

village bull’.

In Rwanda, EADD partners with the government’s

Rwanda Animal and Research Development Authority

and the Eastern Region Animal Genetics Improvement

Cooperative to ensure sustainability of the AI program.

Rwanda’s government-subsidized program imported

10,000 units of gender-sorted bull semen in 2010, the

largest consignment of its kind ever exported to Africa.

In Kenya, AI is moving away from a public-sector

extension service to become a highly successful

commercial enterprise. The rate of successful

impregnations is above 80%.

In Uganda, where 95% of cattle were local breeds,

EADD persuaded the government to change its policy

on breeding and promote AI. Because farmers found

the cost of insemination high, the EADD team reduced

the price for a straw of semen by 15-20% and added

a further 10% discount on every 30 straws purchased.

EADD also created 22 AI satellite centers in remote

areas to cater for pastoralist farmers who found it

difficult to access services. The centers offer breeding

and veterinary services as well as semen and breeding

supplies. They are staffed by AI technicians and

Community Animal Health Practitioners. Largely as a

result of these initiatives, AI uptake increased by 25%

in 2010.

The success of AI uptake lies in efficiency and

affordability. By midterm of Phase 1, more than 400

Community Animal Health Practitioners had been

trained as accredited AI service technicians. About

95% of AI technicians are under 35 in line with EADD

policy to target younger people. For cultural reasons,

few women have signed up to be inseminators, but the

barriers are crumbling. Between 2008 and 2011, the

proportion of AI providers who are women grew from

3% to 11%.

Farmers need proper training too. Keeping a

record of each cow’s breeding cycle is important for

achieving high conception rates. So is understanding

how to use the heat-detection system to establish

when a cow is in estrus. EADD has trained more than

100,000 farmers to make informed decisions on when

and how to breed.

Even though efficient systems and subsidies have

greatly reduced the cost of AI ($10 -15) to the farmer,

affordability remains a major challenge. Hubs offer the

service on credit, but many farmers are not able to pay

for AI solely from milk proceeds. EADD is overcoming

this through subsidies. AI service providers are also

facing difficulties in funding their business start-up

costs to buy equipment and a motorbike. EADD is

considering financing mechanisms for new providers.

If you sample from the same bull, you can’t

improve more than 2% in a generation. If you

choose from the global pool of elite genetics,

the improvement is 200% in a generation. You’re

leveraging with scientific knowledge to rapidly

change an indigenous animal into a viable dairy

unit.

Nathaniel MakoniTeam leader, EADD breeding section

Field Studies

A field with a resident herd of Ankole cows is

not the average seat of learning, but it is ideally

suited for the purposes of Paul Chatikobo,

the AI training coordinator for EADD in

Rwanda. Here, in the rain-splashed grass

and mud, attentive Community Animal Health

Practitioners undergo two weeks of practical

application in AI having completed a week

of theory in a conventional classroom. Most

students are men in their 30s. While AI is not

yet widely accepted as a woman’s job, several

young women have broken the gender barrier

and enrolled in the class.

The school is a public-private partnership

between EADD, the state-run Institute of

Agricultural Science and Research and the

Eastern Region Animal Genetic Resources

Investment Corporation, a for-profit company

owned and run by Rwandan AI experts. It

was established to lay the foundation for a

sustainable AI sector in Rwanda. It trained 164

students in the first 22 months of operation.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

15

Set amidst softly rolling hills and lush pastures,

Urugero Farm in Rwanda’s Nyagatare District is

home to 26 crossbreed Friesian cows. Each one was

bred on site with AI in 2009 and 2010. With the cows

yielding 50 liters a day, the profits from this dairy

business are healthy as the herd’s owner, 50-year-old

Celestin Bwimana, is quick to point out. In 2010 his

net earnings from milk sales were $4,000, an eightfold

increase on his annual income before he went into the

dairy business.

That is not bad for a man who was born a refugee in

neighboring Uganda. Celestin came to the land of his

birthright in 1995, the year after Rwanda’s genocide,

as a beneficiary of a government resettlement scheme

on land excised from the Akagera National Park.

Celestin was allocated 19 hectares of bush which

his herd of 23 native Ankole cows shared with lion,

leopard, buffalo, zebra and impala.

‘We didn’t own the land so we didn’t bother to

clear it. The cows didn’t give any milk. We kept them

because that’s what people do,’ he explains, referring

to the Rwandan belief that livestock ownership

confers social status. Meanwhile Celestin and his wife

struggled to raise their children on their $500 annual

income from a canteen they had built to cater for the

village secondary school.

Then three years ago two events coincided to

change Celestin’s life dramatically. The Rwandan

government gave him a title deed. It was the incentive

he had been waiting for to improve his land. As a

refugee, Celestin had not been exposed to agriculture.

Now he intended to earn a living from it. But how was

he going to go about it?

The answer came in the form of EADD’s Joseph

Karake. The two met at a recruitment drive for the

Isangano chilling plant. Celestin’s cows did not

produce surplus milk for sale. He had signed up as

Home at Last

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

16

a member anyway, lured by the prospect of being

trained in dairy management, getting access to a

market and receiving reliable payments. ‘Joseph told

us to change our cows so that we could get milk.

That’s what convinced me – the milk yield,’ he says.

Celestin’s enthusiasm caught Joseph’s attention. He

signed him up as one of the 13,000 farmers who have

gone on exchange visits to farms and business hubs

in East Africa to observe best practices in operation.

On his return Celestin sold his old herd and began to

breed a new one by crossing high-yielding Friesians

with the hardy local Ankole cattle. A novice in animal

husbandry, he was advised every step of the way

by EADD’s breeding specialist, Margaret Mukawera.

EADD’s senior dairy specialist, Betty Rwahumzi,

visited regularly to talk about milk quality, hygiene and

mastitis.

Celestin proved to be a quick and enthusiastic

learner. For a small facilitation fee provided by EADD,

he now trains others in dairy essentials such as

breeding, husbandry, feeding, fodder growing and

record keeping. And in a role switch that brings a smile

to his face, he receives farmers on exchange visits

from Uganda and Kenya.

‘EADD showed us how to change the way we live,’

says a beaming Celestin from his recently built office

in one of the fields. Milk sales paid for its construction

as well as for the purchase of motorbikes to transport

the milk to the chilling plant and for his daily commute

to and from his house in the village. Milk also funds the

schooling for his six children.

‘I have a five-year vision. I’m putting all my profits

into improving the farm and building a larger house

for the family. After that, I’ll start saving my money,’ he

says.

Celestin Bwimana’s annual income has increased eightfold.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

17

Justus Ndigwa, 33, is an independent AI technician

attached to Kenya’s Ol Kalou chilling plant. He visits

clients in his catchment area on his fully paid-up

motorbike. He often trains Dairy Management Groups

on breeding, feeding, milk quality and good husbandry.

And for a fee, he will organize farmer exchange

visits. Justus, who can count on a minimum monthly

revenue of $1,000, will soon be moving his wife and

two children into a newly constructed, $11,250 three-

bedroom home. In sum, his prospects are bright.

It was not always that way. Four years ago Justus

was earning $125 a month as an extension services

manager at a dairy farmers cooperative. He could not

even afford to rent a room in which to lodge his new

bride. Then he linked up with the Ol Kalou chilling

plant as an accredited professional AI service provider.

Ol Kalou provided progeny-proven semen together

with an AI kit and facilitated an interest-free loan

to cover their cost. Justus still needed $1,560 for a

motorbike so that he could reach his clients’ scattered

farms. He approached a bank for a commercial loan,

knowing that his association with Ol Kalou would

establish his creditworthiness.

Before EADD had a presence in Ol Kalou, Justus

would not have been able to secure a loan for a

motorbike and, arguably, would not have been able to

start up his business. The agriculture sector has been

habitually shunned as a poor risk. Now, with advice

from EADD’s business advisers, the tables have been

turned.

EADD has been able to open up this avenue through

its evolving partnerships with commercial banks. While

banks showed interest in financing chilling plants,

they were less inclined to become involved in the

time-consuming prospect of small loans to individual

Kenya Banks Pioneer Small Loans to Farmers

farmers. Then in 2010 a dialogue was started with

Family Bank, which was already lending to Kenyan tea

farmers, most of whom received monthly payments for

their tea leaves of less than $60.

Excited by the prospect of expanding into the dairy

sector and reassured by EADD’s track record, Family

Bank dispatched team members to attend Dairy

Management Group meetings and visit homesteads

and chilling plants to gauge the farmers’ needs. The

Women lead as account holders, savers and borrowers in financial

services associations.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

18

result of this footwork is a unique financing package

tailored to the input requirements of Kenyan dairy

farmers. Working through the dairy hubs, Family Bank

intends to build up a portfolio of 5,000 customers by

the end of 2011. The loans are usually for business

start-up and expansion and tend to be less than

$1,250.

‘We serve those who once were considered

unbankable,’ explains David Odongo, who heads

Family Bank’s agribusiness department, ‘Thanks to

EADD and the dairy hubs, we can ascertain a farmer’s

security and assets. The chilling plant verifies average

monthly earnings which equates to the company pay

slip. We also collateralize the farmer’s most important

asset, which is the cow. Each cow is entered in a

database and given a performance rating based on

its yields. This has a bearing on the value we give it.

Some are worth $1,000.’

Commercial banks are definitely filling a financing

gap for transporters and service providers. In the first

quarter of 2011 Family Bank disbursed 234 loans for

the purchase of motorbikes. Another 170 applications

are in the pipeline. Other loan applications are for the

purchase of fodder seed, veterinary drugs, AI, stocking

herds and the partial financing of domestic biogas

installations.

Fodder makes a big difference to milk production,

particularly during the dry season. Sound feeding

practices using homemade feed concentrates, hay

and silage sustain steady milk yields. This, in turn,

stabilizes the year-round milk supply and therefore

farm-gate prices. East Africa has constantly changing

mini ecosystems across the region. It took EADD

feed specialists two years to fine tune the feeding

requirements for each site. In fact, the process is

ongoing. When farmers upgrade their herds to exotics

and crossbreeds, the feeding strategy changes again.

Feed comprises up to 70% of the cost of milk

production on small holdings and is a key component

of cost-benefit analysis. EADD recommends farmers

improve pasture by planting Napier grass and legumes

such as Chloris gayana, Mucuna prurien, and Lablab

uncinatum to provide protein. It also recommends

that farmers mix their crop residues with molasses to

make silage. Solutions such as these go a long way to

boosting profit margins.

EADD also supports the invention of new

technology. Kenyan George Kinuthia modified a

hammer mill by adding a cutting blade and came up

with a low-cost EADD pulverizer for on-farm silage

making. This model has been replicated in all three

countries where it is made locally for sale and rent

through chilling plants.

EADD emphasizes farmer education on feeding

and growing fodder through training, exchange visits

and demonstration plots belonging to EADD model

farmers. To date some 2,000 farmer trainers have been

trained in improved feed practices. As a result, more

than 125,000 farmers (75% of the Phase 1 target) are

using quality feeds.

In Uganda, more than 38,000 farmers are already

using high-value feed for their milking cattle, partly

Good Feeding MakesHealthy Cows

A farmer gets a receipt for milk delivered at Ol Kalou dairy in Kenya.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

19

FARMERs ADOPTING IMPROvED PRACTICEs

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

KENyA

Feed conservation

practices

AIFeed concentrates Improved fodder

crops

Catchment beneficiaries

Catchment non-beneficiaries

Control

Catch

men

t a

rea in

percen

tage

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

UGANDA

Feed conservation

practices

AIFeed concentrates Improved fodder

crops

Catchment beneficiaries

Catchment non-beneficiaries

Control

Catch

men

t a

rea in

percen

tage

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

RWANDA

Feed conservation

practices

AIFeed concentrates Improved fodder

crops

Catchment beneficiaries

Catchment non-beneficiaries

Control

Catch

men

t a

rea in

percen

tage

source: EADD Midterm Evaluation Report 2010

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

20

thanks to commercial feed companies that supply on

credit to many of the agrovet stores. The bulk retailing

comes with a discount which means that farmers can

buy mineral licks, premixes and meal more cheaply

than at other retail outlets. Local seed supply systems

are also being developed so that farmer groups can

grow and bulk pasture seeds for sale. In Kenya, where

the prolonged dry season can last up to six months,

three out of four farmers have attributed their high milk

yields to improved feeding.

George Kariuki lives on the family farm perched

2,000 meters above Nakuru town on the floor of the

Rift Valley. He is an EADD farmer trainer and model

farmer who grows frost-resistant varieties of Napier

grass in his demonstration plots. George, who

facilitates exchange visits for local farmers, pioneered

his own variation of the pulverizer and uses it to make

three tons of silage to carry his milking herd through

the dry season. As a result, his cows have doubled

their production to up to 40 liters a day. ‘I’m very

happy with EADD,’ he beams, ‘We see people doing

things differently, and it plants ideas in our minds and

makes us ambitious. Without knowledge, you can’t

move.’

EADD also encourages Dairy Farmers’ Business

Associations to introduce Dairy Management Groups

to the idea of growing fodder commercially and to

link interested farmers to banks that will fund start-

up costs. Even so, most farmers do not consider

growing fodder for sale to be a worthwhile commercial

enterprise. But if they knew the story of Pharo

Ngaranbe, a Rwandan smallholder, they might change

their minds.

Pharo, 55 and a primary-school leaver, was barely

making a living growing sorghum, beans, sweet

potatoes and bananas on his one-hectare farm.

Then he met Bernard Nzigamasabo, the EADD feeds

specialist, and expressed an interest in starting

up fodder demonstration plots. EADD gave Pharo

improved fodder seeds and helped him negotiate a

supply contract with the nearby Umutara Polytechnic

University’s livestock department.

Three years on, Pharo has bought a second hectare

of land from a neighbor and is renting another six

hectares on which he grows commercial quantities

of Brachiaria grass. He also has his own small herd

of zero-grazing Jersey crossbreed cows and grows

improved fodder seeds for sale to other farmers.

source: EADD Midterm Evaluation Report 2010

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

21

He advertises his wares on a local radio station. His

annual income has been sufficient to build a new

house and to send his seven children to private school

and university.

To maintain his commercial fodder business Pharo

employees 50 laborers and has taken out medical

cover for each of them. So far he has trained more

than 350 dairy farmers on fodder and feeds best

practices. Recently his fodder store was blown down

in a storm. He intends to raise a loan from the bank to

rebuild it using his fodder account to demonstrate his

creditworthiness.

‘I learned all this through the training I got from

EADD. It’s a question of maximizing my skills and

knowledge. Now I want to help my neighbors escape

poverty too,’ he says.

A model farmer pulverizes fodder for the dry season.

In Uganda it is not unusual to see cows wandering by

the side of the road or on the common land around

villages and towns. This free-grazing method cuts

down on fodder and labor costs, but cows are not

able to find sufficient food. And their diet lacks vital

minerals and proteins. Supplementary feeds can

make up the balance, but they are costly and hard to

find. Even when farmers travel up to 30 kilometers to

the nearest town, there is no guarantee they will find

concentrates in stock or that the sales assistant will be

able to advise on the correct feed amounts.

EADD’s Uganda feeds team considered how best

farmers could access quality supplementary feed at a

reasonable cost and concluded that a localized feed

mill was the answer. They partnered with the Bubusi

Dairy Farmers’ Business Association and the National

Agriculture Advisory Service for the pilot turnkey

project. Bubusi is a traditional market hub north of

Kampala where farming is intensive, a mix of crops

and two to five cows on plots of land not larger than

two hectares.

EADD came up with a formula for the meal and

concentrates and helped the farmers to source

ingredients that were relatively cheap but which

provided quality. The team also helped the farmers

to draw up a business plan and linked them to an

equipment supplier that offered flexible repayment

terms. The start-up capital was funded by farmers’

share contributions and a soft loan guaranteed by

EADD. The mill came on stream in November 2010. It

has a production capacity of 1.2 tons a day and does

a brisk business.

‘We want to put a smile on farmers’ faces. That’s

our homework,’ says Jane Kugonza, EADD’s team

leader for feeds in Uganda.

Bubusi Feed Mill

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

22

Reversing the Urban Drift

Young people in their 20s and 30s know only too

well that dairy provides a route out of enduring,

generational poverty. The Silanga Youth Group at

Kabiyet borrowed $600 from the District Youth Fund

to purchase three heifers for members who did not yet

own cows. Now all have seen a substantial rise in their

standards of living. The group also helps to support

the community’s orphans and people living with HIV.

Selly Cherotich, 33, is a Silanga member. She and

her husband own a Friesian and a Jersey and are

paid-up shareholders at Kabiyet. Like their fellow

shareholders, they have learned how to prepare hay

and silage to feed their cows through the dry season.

Consistent milk yields is one of the reasons why

Kabiyet was able to more than double the farm-gate

price when negotiating a contract with New Kenya

Cooperative Creameries.

Selly is the mother of seven children including two

sets of twins. She supports and schools them on milk

proceeds. ‘I’m a school graduate, but most of our

parents couldn’t find the money to let us finish school.

Anyway, I’ve never been able to find a job. We want it

to be different for our children, and EADD has raised

our morale,’ she says.

In neighboring North Nandi District Juliana

Maiyo is treasurer of the all-women Kemeliet Dairy

Management Group. The women formed it in 2008

even though none of them owned cows, because they

saw the potential in dairy. They began to buy milk from

farmers and to transport it in bulk to the Tanyikina

Dairy Plant. At the same time, because they were

already organized, the Kemeliet group was among the

first to receive EADD training on fodder establishment,

animal health, farming as a business, silage making

and water harvesting. These improved methods have

paid off for Juliana. She has been able to buy another

crossbreed cow for $375 and her other two cows are

in calf. She has also built a cow barn to store hay. She

is never behind with school fees and there is always

nutritious food on the table at mealtimes.

Juliana banks at the Tanyikina Financial Services

Association which is managed by 24-year-old

Jasper Langat. It pays advances against milk

delivery for anything customers need. This includes

health insurance through the dairy hub’s Tanyikina

Community Health Program. In just over a year the

bank’s members have grown tenfold to 2,000.

‘Women make up the highest number of account

holders. They seem to have a better grasp of saving

and borrowing. One of my female clients dropped out

of secondary school because her parents couldn’t

afford the fees. She bought a share in Tanyikina Dairy

and in the bank too. Now she has 28,000 shares and is

about to build her own store,’ Jasper says.

‘At first it was difficult to persuade people to entrust

us with their money.’ he continues, ‘They would

deposit it and then withdraw it three days later to see

if it was still all there. That’s changed now, of course.’

Jasper, who is native to the district, left a job in Nairobi

to run the bank. Since his return home a year ago,

several brick buildings have been constructed at

Tanyikina, he says.

Purity Chipchirchir, 28, dropped out of school but now runs her

own store and milk-trading business.

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

23

Tetra Pak seals its agreement with EADD and

Metkei Multipurpose Co. Ltd. with a cheque of $31,250.

EADD’s business-based approach to development has

attracted multinationals such as Nestlé and Tetra Pak.

When Nestlé established its regional headquarters

in Nairobi, Kenya in 2008, it knew that working

with EADD would dovetail with its own corporate

philosophy of supporting rural development through

stimulating processor demand for chilled milk. The

company chose Kabiyet Dairies in Kenya’s Rift Valley

Province to pilot a blueprint for milk collection and

marketing.

Kabiyet is developing operating procedures

for hygiene and quality norms that meet rigorous

international standards. A technical expert seconded

to the dairy from Nestlé provides assistance with raw-

milk quality and safety management from farm gate to

factory. Once established as a model of export-quality

milk production, the dairy will be able to market its

milk to Nestlé for regional export as powdered milk.

It will also become a training ground for other chilling

plants in the region.

Corporates Help Expand Dairy Markets

One of Nestlé’s strategies is ‘Keep it simple. Keep

it small’. New chilling plants and those undergoing

expansion have adopted the multinational’s

recommendation for installing low-tech, low-cost,

low-capacity (1,500 – 2,500 liters) coolers. Similar

partnerships with local processors have been entered

into with local processors - New Kenya Cooperative

Creameries (Kenya), Sameer (Uganda) and Inyange

(Rwanda) – to establish dairy-hub benchmarks for raw-

milk quality.

Tetra Pak is assisting with the introduction of quality

protocols at Kenya’s Metkei and Kokiche chilling

plants. As a result, some 30,000 farmers have been

able to negotiate competitive prices for supplying

milk to the New Kenya Cooperative Creameries

UHT processing plant. Tetra Pak intends to offer its

package of a value-chain performance, milk-quality

assurance and management training to more chilling

plants.

EADD sees the partnerships with Nestlé and Tetra

Pak, the world’s largest milk buyer and milk packager,

as a marketing incentive for processors to adopt a

quality-based pricing scheme. This in turn would be

an incentive for farmers to invest in good feeding,

breeding and hygiene practices.Group photo of the Kabiyet-EADD-Nestlé partnership

EADD MIDTERM REPORT 2008 – 2010

24

Madeline Madamu and Stephen Kaberuka are

exceptional examples of courage and determination

triumphing over adversity. Most likely they have

never met, but they share similar experiences. They

both own purebred Friesian cows and are EADD

Community Animal Health Practitioners. Both are

model farmers who have swapped best practices in

exchange visits with Kenyan and Ugandan farmers.

Both are survivors of the 1994 Rwanda genocide.

Just a few years ago neither knew much about

cattle or the dairy industry. Madeline lived in a mud-

brick house empty of furniture and grew barely enough

to feed her six children. Stephen was a penniless

manual laborer who worked piecemeal for his

neighbors. Left for dead from a bullet wound, he had

lost 26 family members including his wife and children.

Madeline had lost her husband, parents and siblings.

Their homes had been burned to the ground.

Today Stephen, who has remarried, is a prosperous

entrepreneur who runs several micro-businesses

from his hillside homestead overlooking the town of

Rwamagana. He rents his neighbor’s land to grow

chloris and Napier grass as fodder for his four cows. In

a good year he harvests 30,000 pineapples for export.

He has installed a biodigester fuelled by cow waste

Much in Common

to light his house. His wife runs a bakery business.

His son uses one of his two motorbikes to deliver milk

to the local chilling plant. His children and the four

orphans who live with the family attend private school.

He is in the throes of constructing a fee-paying school

from where he will teach good farming methods.

With a monthly income of about $385 from milk sales

alone, he is regarded as a wealthy man in the eyes of

the community. He traces his success back to 2008

when he received a gift of a cow. He then joined a

dairy hub which gave him access to bank credit and a

succession of loans to improve his farm.

Like Stephen, Madeline’s life changed for the

better thanks to the cow she was given by Heifer

International. Madeline also joined a dairy hub and