E CYE MAGE YEL S ing ealth - Muttart · fundraising campaign to complete its YMCA building. In...

Transcript of E CYE MAGE YEL S ing ealth - Muttart · fundraising campaign to complete its YMCA building. In...

E1KE1CYE1MAGE1YEL

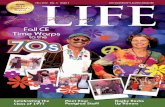

Sharingtheir

wealth

pVolunteerpioneers

5p

Fundraisingpros weigh in

6p

Fighting thefunding gap

7p

Immigrantsswell volunteer

ranks

10p

Virtualvolunteers

12p

Where doyour donateddollars go?

13p

Taking the stagein Rosebud

15p

Socialentrepreneurship

16

E EDITOR: KERRY POWELL, 429-5373; [email protected] EDMONTON JOURNAL WEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2005

AnEdmonton

Journalspecial

report onAlberta’s

volunteersand

not-for-profitorganizations

FILE PHOTOS FROMCANDACE ELLIOTT,BRIAN GAVRILOFF,

ED KAISER,JOHN LUCAS,

RICK MacWILLIAM,LARRY WONG,THE JOURNAL

AND FROM THECALGARY HERALD,

CANWEST NEWSSERVICE

RICK MacWILLIAM, THE JOURNAL, FILE

Clockwise from main photo:Jessica Moe, Krysten Lozier

with Farhana Hadi andDavid Williamson, Leslie

Genao, Miriam Marifa withKitty Gambler, Jane Xu,Vanessa Mansell, Dan

Garsonnin, from left, NancyStewart, Jean Thomson,

Elma Chavez, Chris Lees andDee MacPherson,

Tony Lau, Marcus Desireau,Frankie Moffat, Cindy

Gordon, Remy Lastiwka,Brian Eaton and Joe Shea

E2 NEW

E2 EDMONTON JOURNALWEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2005 S H A R I N G T H E I R W E A L T H

=GROUFG TGD FDMDROSHTY OE OUR EOUMCDRS% 7DRRHKK 7UTT@RT @MC

0R' 3K@CYS 7UTT@RT% WD G@VD ADDM @AKD TO L@JD FR@MTS TG@T GDKP

BG@RHTHDS GDKP /@M@CH@MS% WGDTGDR TGROUFG TGD @RTS% TGROUFG

DCUB@THOM% TGROUFG SOBH@K&SDRVHBD PROFR@LLHMF @MC RDBRD@THOM

OR TGROUFG LDCHB@K RDSD@RBG' 5M TGD K@ST *) YD@RS% WD G@VD L@CD

FR@MTS TOT@KHMF LORD TG@M :*( LHKKHOM TO BG@RHTHDS% PRHL@RHKY HM

-KADRT@% <@SJ@TBGDW@M @MC /@M@C@NS 8ORTG'

-KADRT@ W@S AUHKT AY VOKUMTDDRS $ PDOPKD GDKPHMF OMD @MOTGDR' 9UR

PROVHMBD BOMTHMUDS TO AD @ KD@CDR HM TGD M@THOM HM VOKUMT@RHSL'

=GUS% HM TGD /DMTDMMH@K YD@R% HTNS LOST @PPROPRH@TD TO EOBUS

@TTDMTHOM OM TGD VOKUMT@RY SDBTOR HM -KADRT@'=GD 7UTT@RT

2OUMC@THOM HS PKD@SDC TO L@JD TGHS POSSHAKD TGROUFG TGHS

SPDBH@K RDPORT'

=GD VOKUMT@RY SDBTOR CDPDMCS OM VOKUMTDDRS% AUT HT HS LUBG

LORD TG@M VOKUMTDDRS' 5T DMBOLP@SSDS GUMCRDCS OE TGOUS@MCS OE

PROEDSSHOM@KS @BROSS TGD BOUMTRY% WGO WORJ THRDKDSSKY TO L@JD KHED

ADTTDR EOR @KK OE US' 5T HS @ SDBTOR TG@T BOMTRHAUTDS LORD TO OUR FROSS

COLDSTHB PROCUBT TG@M @FRHBUKTURD% OR RDT@HK TR@CD% OR TGD LHMHMF%

OHK @MC F@S DXTR@BTHOM HMCUSTRY' 5T HS @ SDBTOR WGHBG TOUBGDS D@BG

OE US DVDRY C@Y'

=O @KKOW EOR TGD L@XHLUL BOVDR@FD @MC RDPORTHMF OM TGD

VOKUMT@RY SDBTOR%=GD 7UTT@RT 2OUMC@THOM G@S @FRDDC TO AD

TGD SOKD @CVDRTHSDR HM TGHS SPDBH@K RDPORT'=GHS WHKK @KKOW YOU TO

RD@C @AOUT TGD SUBBDSSDS @MC TGD BG@KKDMFDS OE TGD PDOPKD @MC

ORF@MHZ@THOMS WGO @RD WORJHMF EOR YOU TO L@JD -KADRT@ @M DVDM

ADTTDR PK@BD TO KHVD'

=GD BG@RHT@AKD SDBTOR DMIOYS SHFMH#B@MT PUAKHB SUPPORT @MC

TRUST $ @S WDKK HT SGOUKC' - L@IOR M@THOM@K RDSD@RBG PROIDBT WD

BOLLHSSHOMDC K@ST YD@R SGOWS TG@T @KLOST ,(? OE /@M@CH@MS

TGHMJ TG@T TGD BOUMTRYNS BG@RHTHDS G@VD @ ADTTDR UMCDRST@MCHMF

TG@M FOVDRMLDMTS OE TGD MDDCS OE TGD PDOPKD @MC TG@T +)? TGHMJ

TG@T BG@RHTHDS CO @ ADTTDR IOA TG@M FOVDRMLDMTS HM LDDTHMF TGOSD

MDDCS' 5M TDRLS OE TRUST% KD@CDRS OE BG@RHTHDS BOLD ADGHMC OMKY

MURSDS @MC LDCHB@K COBTORS% @MC WDKK @GD@C OE OTGDR PROEDSSHOMS'

=GHS HS SUPPORT @MC TRUST TGDY G@VD D@RMDC AY G@RC WORJ @MC AY

TGD HLP@BT TGDY G@VD G@C OM OUR BOLLUMHTHDS'

2OR HTS P@RT%=GD 7UTT@RT 2OUMC@THOM WHKK BOMTHMUD TO CO WG@T

OUR EOUMCDRS @SJDC OE US $ TO PROVHCD SUPPORT TO PDOPKD WGO

@RD BOMTRHAUTHMF TO TGDHR BOLLUMHTHDS'=GROUFG SUPPORT OE

PROFR@LS KHJD 6HCS HM TGD 4@KK HM 1CLOMTOM% .HF .ROTGDRS .HF

<HSTDRS ORF@MHZ@THOMS% OR TGD /@KF@RY /G@LADR OE >OKUMT@RY

9RF@MHZ@THOMS% BOMSTRUBTHOM OE E@BHKHTHDS SUBG @S TGD 7UTT@RT

/OMSDRV@TORY% SUPPORT OE LDCHB@K RDSD@RBG TGROUFG TGD 7UTT@RT

0H@ADTDS ;DSD@RBG @MC=R@HMHMF /DMTRD% KO@MS @MC FR@MTS TO

QU@KHTY BGHKCB@RD E@BHKHTHDS HM <@SJ@TBGDW@M @MC RDSD@RBG HMTO TGD

SDBTOR% WD WHKK BOMTHMUD OUR DEEORTS TO STRDMFTGDM TGD VOKUMT@RY

SDBTOR HM -KADRT@ @MC @BROSS /@M@C@'

=GD .O@RC OE 0HRDBTORS

=GD 7UTT@RT 2OUMC@THOM

,6:02 6@? 3;A:16:4 6: %('&#

-52 +A@@.>@ *;A:1.@6;: 5.? /22:

?A<<;>@6:4 ).:.16.: 05.>6@62? .? @52D C;>7 @;

69<>;B2 @52 ;B2>.88 =A.86@D ;3 8632 6: ;A> 0;A:@>D$

E3KE3CYE3MAGE3YEL

S H A R I N G T H E I R W E A L T H100 YEARSOF GIVING

From the native “Society of the Generous” — consisting of acommunity’s best hunters donating shares from a hunt to their lessfortunate members — to pioneer families helping each other raisea barn, a western spirit of volunteerism existed long before thecreation of Alberta’s provincial borders and formal government.

The Edmonton YMCA and YWCA areincorporated by special provinciallegislation. In 1908, the YMCA opens athree-storey facility housing “social”rooms, a lunchroom and classrooms.

19071905

Calgary launches a $50,000fundraising campaign tocomplete its YMCAbuilding. In 1910, Calgaryopens its first YWCA.

1909

EDMONTON JOURNAL WEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2005 E3

The changing faces of Alberta’s volunteersCHRISTINE PEAKE BREMNER

S p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a lEDMONTON

Alberta volunteers.According to the 2003 National

Survey of Nonprofit and VoluntaryOrganizations, there are 19,000 vol-unteer and not-for-profit organiza-tions in the province,with 2.5 millionvolunteers. These Albertans collec-tively contribute about 449 millionhours, the equivalent of 234,000 full-time jobs.

In economic impact, that’s morejobs than in the mining, oil and gassector plus the accommodation andfood services sector combined, ac-cording to Statistics Canada.

Further, these organizations em-ploy 105,000 paid staff members.

Despite these numbers, Alberta’snot-for-profit and voluntary sectorsees a problem looming. An increas-ing number of organizations reportdifficulty in attracting new volun-teers and retaining existing ones, re-sulting in more work falling on theshoulders of fewer people. Volunteerburn-out coupled with changing de-mographics produces a potential vol-unteer shortage.

The first of the baby boomers areapproaching 60; the tail end of thecohort is nearly 40. This generation,about 30 per cent of the province’spopulation, has been steadfast in vol-unteering. As they retire, will theycontinue this commitment?

The next generation, children of theboomers, are under pressure. If bothparents work, they find themselvesjuggling longer working hours, childrearing and sometimes parent care,leaving them with less time for recre-ational and voluntary activities. Addmore new immigrants, often dealing

with a new language and culture, andyou have an increasing demand forservices with a potentially decreasingvolunteer supply.

The volunteer sector has started itsstrategic planning. “It’s not yet a cri-sis, but we’re starting to get to thatpoint,” says Karen Lynch, executivedirector of Volunteer Alberta. “Oneway we’re addressing the situation isby getting youth involved in the com-munity, and we do this by increasingawards, showing appreciation, anddeveloping programs especially foryouth.”

An Edmonton example is the web-based Youth One, a program of theSupport Network.

“We offer a lot of services online, in-cluding a magazine written by youth,for youth,” says Jennifer Wong,youth supervisor. “One of our ser-vices is YouthVOLUNTEER!, whichconnects youth, aged 13 to 24, withvolunteer opportunities. It’s a clear-inghouse for other not-for-profitgroups and agencies.”

The best way to attract young vol-unteers is through example, Lynchfeels: “We know that when volun-teering is part of the family culture,children and teens will continue tovolunteer.”

Time is the problem. Parents maynot be able to commit to regularmeetings and ongoing programs, butthey may be willing to work on a spe-cific project such as a fundraisingevent or festival. It’s called episodicvolunteering, and more organiza-tions are restructuring and tailoringtheir activities to accommodate it, ac-

cording to Lynch.Edmonton’s high schools hold vol-

unteer fairs, and Miki Stricker, Festi-val Director of Edmonton’s Fringe,has attended a number of them.“What is great about Edmonton isthat high school students can earncredits for volunteer work, and Ithink it’s wonderful that high schoolsare trying to help.We’ve had somewonderful volun-teers come out ofthis program.”

Corporations, too,are recognizingtheir need to sup-port volunteeringwith more thanmonetary dona-tions. “CorporateCanada is realizingthat the kind of em-ployee who bene-fits the companyalso supports the community,”Stricker says. “Home Hardware inWetaskiwin is one example. Whenemployees who are members of thevolunteer fire department are calledinto action during work hours, theyknow that when they head out thedoor, they won’t lose any wages.”

It’s not just an aging population andlifestyle changes. Our ethnic compo-sition is being transformed. You cansee the diversity of our population intwo of Alberta’s major summer festi-vals: Edmonton’s Heritage Days andCalgary’s GlobalFest, largely run byvolunteer members of various cultur-al communities.

Within a number of ethnic commu-nities, volunteer organizations easethe transition into Canadian culture.Assist Community Services Centrehas helped Chinese immigrants withsettlement and integration servicesin Edmonton since 1977. WanfangLy-Lin, one of 295 volunteers, re-gards her work at the centre as a full-

time job.When the retired

nurse from Tai-wan is not at thefront desk, an-swering the phoneand referringclients, she’s afamily mentorthrough the BigBrothers/Big Sis-ters program.“The kids call megrandma,” shesmiles. She alsoeducates women

about the breast cancer screeningprogram.

“I had no idea of volunteering fulltime when I first came in,” she says,“and I’ve gained new skills andknowledge. I feel that I get more thanI give.”

Though Calgary and Edmonton at-tract the majority of new immigrants,Medicine Hat is getting its share, par-ticularly of African refugees.

“We’re a one-stop refugee settle-ment organization, the only one serv-ing Medicine Hat,” says Linda Gale,executive director of Saamis Immi-gration, “and our situation is com-pounded by a two-hour drive to the

closest federal immigration office.”The agency has four and a half staff

members and between 150 and 170volunteers. “Our volunteers are pre-dominantly ‘mainstream’ Canadians,aged 30 to 50, supplemented by theirfamilies. About half are immigrantsthemselves,” says Gale. “When weengage newcomers in volunteeringdepends on their skills. Those withgood language skills may find them-selves signing up as volunteer trans-lators within days.

“We introduce many of our clientsto volunteering through our localhomeless shelter,” she continues.

“One week, every second month,our organization staffs the soupkitchen. Some of our clients comefrom countries where volunteering isnot seen as valuable and part of theirculture, while others have well-de-fined skills in the area of volunteer-ing.”

In the short term, the imminent re-tirement of baby boomers may provea boon to the voluntary sector.Healthy, enthusiastic and experi-enced seniors may look for an outletfor their energies: a way to stay activeand contribute once their paid ca-reers are complete.

It’s possible that new immigrantsmay integrate themselves into broad-er community volunteer activitiesover time, just as previous genera-tions of new Canadians did. Today,organizations are looking at ways tostructure their activities to encourageyouth and more mature, episodic vol-unteers to use their time and skills toadvantage.

The volunteer sector has becomeaccustomed to adapting to new anddifferent needs, and the changingface of volunteerism will reflect theAlberta of the future.

An aging population, 21st-century lifestyles and immigration are changing the province’s demographics —and the landscape of volunteerism

Forget altruism. Volunteer, donate out of enlightened self-interest

My Uncle Alfie was the greatest philanthropist I ever knew.

He didn’t have millions of dollars.He was no captain of industry. Formuch of his life, he ran a small drygoods store on Fort Road, in northEdmonton.

He never endowed a museum. Noone ever named a concert hall or auniversity chair in his honour.

My uncle didn’t give the gift ofmoney. He gave the gifts of skill andtime.

The list of charities he worked forover the decades is too long to in-clude in its entirety. The Rotary Club;St. Anthony’s College for Boys; Good-will; the Jewish Seniors Drop-In Cen-tre; the Army, Navy, and Airforce Vet-erans Club; and the Robertson-Wesley United Church communitydinner program were just a few of hisfavourite groups and causes.

My uncle was a gifted amateurchef, and though he volunteered inmany ways, what he loved to do bestwas to organize and prepare nutri-tious, home-made meals for massesof people. Blintzes and latkes,spaghetti sauce and cabbage rolls andhamburgers, ginger snaps and honeycakes.

People would ask him to run their

charity kitchens, and he’d leap at thechance.

My uncle was Jewish, but his atti-tude to volunteerism was utterly ecu-menical. If he admired the work of agroup or agency, he’d be there tohelp. Orthodoxies and ideologiesnever interested him. People did.

He kept on volunteering, well intohis vigourous eighties. Our familyused to giggle over the fact that someof the frailer seniors he assisted wereactually 10 or 15 years his junior.

But please, don’t run away with theidea that my uncle was a saint. Hedidn’t volunteer out of some pureand selfless sense of duty. He did itbecause he loved it.

He loved being with people, and hisvolunteer work kept him from feelinglonely and blue when he was wid-owed, not once, but twice.

In the kitchen, my uncle was anartist, and like every artist worth hissalt, he had a healthy ego. Cookingfor crowds gave him an outlet for hiscreative energies — and guaranteedhim an appreciative audience. Noartist can survive long without ap-plause, and Uncle Alfie never mindeda little praise.

Being a volunteer made him feelneeded, wanted, important. Un-

doubtedly, my uncle’s work benefitedthe social fabric of our whole com-munity. But beyond enriching the lifeof our city, his volunteerism enrichedhis own life. It made him, a diminu-tive retired storekeeper from northEdmonton, feel that he mattered.

And that, really, is the secret to be-ing a great philanthropist. The wordphilanthropy comes from the Greekphilos, meaning loving and the wordanthropos, meaning human being.Philanthropy isn’t the gift of money.It isn’t even the gift of time. It’s thegift of love.

So please, don’t volunteer or donatebecause you feel you should. Don’trun yourself ragged or write bigcheques to impress your friends orneighbours or community leaders.Find a cause that you love, somethingthat really matters to you. Seek out away to help that makes you feel hap-py and useful and appreciated. Havefun. Participate in the life of yourcommunity, not out of some mar-

tyred sense of obligation, but becauseit makes you feel good.

In the end, it doesn’t really do muchgood to lecture people on their moralduty to donate their money or theirtime to earnest, worthy causes.

Sure, we all have a responsibility toour community, to our fellow citi-zens, to contribute to the well-beingof our city and province.

But in a time and place when somany people are stretched so thin,when we have so many bills to pay, somany jobs to juggle, so many familyresponsibilities to manage, it can beself-defeating to preach to people ontheir responsibility to volunteer ordonate.

Such well-meaning lectures can sim-ply make people feel resentful, over-whelmed, reluctant to step forward.

And who can blame people for feel-ing suspicious of official exhortationsto volunteer or donate, when ourgovernments, at all levels, have beenbusy downloading their commitmentto the community, expecting citizensto provide or pay for more and moreof the basic social infrastructure weonce expected our public servants totake care of.

You don’t feel very generous whenyou get the sense that your “dona-tion” is really just some sort of invisi-ble tax.

So forget altruism. Volunteer or do-nate out of enlightened self-interest.You don’t have to have a lot of moneyor a lot of talent to find some way tohelp that makes you feel special, thatgives you a sense of connection toyour community — a sense of be-longing and a sense of purpose.

Give the gift of time or money, andgive yourself a gift at the same time.Cast your bread upon the water —and you may be surprised at whatyou receive in return.

p s i m o n s @ t h e j o u r n a l . c a n w e s t . c o m

True philanthropy is a gift of love, not money

Paul

aSim

ons

“Chef” Alfred Simons

BRUCE EDWARDS, THE JOURNAL

Wanfang Ly-Lin is a retired nurse who volunteers full time for the Assist Community Services Centre. She also volunteers as a famliy mentor through the Big Brothers/Big Sisters program.

“We know that whenvolunteering is part of the

family culture, childrenand teens will continue to

volunteer.”Karen Lynch,

Volunteer Albertaexecutive director

E2

S H A R I N G T H E I R W E A L T H100 YEARSOF GIVING

Edmonton becomes the first city inCanada to adopt the idea ofcommunity-based organizations,forming the Edmonton Federationof Community Leagues.

An amendment to the Criminal Code ofCanada allows pari-mutuel betting andparticipation in games of chance whereprofits are used for charitable orreligious purposes.

19111910

The first community league, Crestwood (formerly the142 Street District Community League), is formed inEdmonton. The league concerned itself with districtimprovements, shared use of the school, socialevenings, and organized sporting events.

1912

E4 WEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2005 EDMONTON JOURNAL

Voluntary sector a $75-billion boon to economy

CHRISTOPHER SPENCERS p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a l

EDMONTON

Canada has one of the largest not-for-profit sectors per capita in theworld, but that’s does not translateinto visibility or respect.

“You’ve got this diverse sector of theeconomy that’s in every communityin the country, but people generallydon’t see it as a sector,” says MichaelHall, vice-president of research forImagine Canada. “It’s definitely a sec-tor that’s under the radar for manyCanadians.”

A study recently completed byJohns Hopkins University and fund-ed in part by the federal governmentshows that not-for-profit, charitableand voluntary organizations accountfor about 8.5 per cent of the nationalGDP. Furthermore, they employmore than 11 per cent of the work-force.

Overall, the not-for-profit sectoradds $75.9 billion annually to theCanadian economy.

Among developed countries, onlyHolland has a larger not-for-profitsector per capita.

The size of the sector and the extentof Canada’s dependence on commu-nity organizations is partly a result ofyears of government funding cuts,says Keith Seel, director of the Insti-tute for Nonprofit Studies at MountRoyal College.

“Government, when it was reduc-ing its size, chose to move services itwas providing directly to the public,onto largely the not-for-profit sector.

“The challenge is that the govern-ment hasn’t sent the necessary re-sources over to deliver those servicesat the same level as the governmentitself was able to do.”

Senator Terry Mercer, a former na-tional director of the Liberal Party ofCanada, argues that the decline ofgovernment involvement and thegrowth of the not-for-profit sectorhave actually improved responsive-ness by creating a more decentral-ized welfare system with localleadership.

“I think now there is a recognitionthat communities need to take con-trol of their own destinies. We havesome tremendous success storiesacross the country.”

The full value of the transition willnot become apparent until the nextrecession, he adds.

“If the economy were in trouble,which it is not, I think the strength ofour not-for-profit sector would helpcushion the impact. We have thishuge infrastructure of organizationsacross the country which can help.”

Hall, the lead author of the JohnHopkins study, says the Canadianmethod of delivering social servicescombines the Anglo-American tradi-tion of philanthropy and volun-teerism with the northern Europeanmodel of public enterprise.

“We’ve got a very unique system inCanada which is very much a hybridbetween the private sector and thecommunity sector. You would thinkthat in countries where the govern-ment was more activist and morewilling to invest in social causes, thecommunity sector would have beenmuch larger. That wasn’t the case.We saw results coming out of Scandi-navia, where they have a very longtradition of government taking a veryactive role in society, not being aboveCanada.”

For example, the not-for-profitworkforce only accounts for 7.1 percent of jobs in Sweden. The UnitedStates and Great Britain are at 9.8and 8.5 per cent, respectively.

One notable difference betweenCanada and the other three countriesis that the number of paid employeesin the Canadian not-for-profit sectoris comparably high. When comparingactual rates of volunteerism, Canada

starts to fall behind.Canadian not-for-profit groups are

also more likely to be involved in pro-viding services such as education,health care and housing, while orga-nizations involved in expressive ac-tivities, such as arts, sports and reli-gion, are more prominent in othercountries.

Seel says the study shows that gov-ernment needs to make issues facing

not-for-profit organizations a higherpriority.

“Because we haven’t been perceivedto be an economic entity, we simplyhaven’t drawn any political attention.Without the political attention, thegeneral public hasn’t seen us as beingof the size and scale that we are.”

Mercer, who is also the chairman ofthe Association of Fundraising Pro-fessionals Foundation for Philan-thropy in Canada, says part of theproblem is that not-for-profit groupshave not taken enough responsibilityfor publicizing their contribution tothe economy.

“I don’t think that the Canadianpublic has any concept as to how im-portant charities are from an eco-nomic point of view. We have to beconstantly educating not just thepublic but also MLAs, MPs, city coun-cillors and members of the schoolboard of the value of the voluntarysector.

“The bottom line is that a healthyand vibrant charitable sector is a keyelement to a strong Canadian econo-my. It’s not just gas and oil in Albertaand cars in Ontario. It’s those chari-ties in every little community across

Not-for-profits must dobetter job of promoting

themselves: senator

“The bottom line is thata healthy and vibrant

charitable sector is a keyelement to a strong

Canadian economy.”Senator Terry Mercer,

chairman of the Associationof Fundraising ProfessionalsFoundation for Philanthropy

in Canada

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

0Non-profit

sectorexcludinghospitals,

universities,and colleges

Utilities Constr-uction

Trans-portation

Manufac-turing

2,073

1,541

132

9231,122

2,294

Empl

oym

ent(

thou

sand

s)

Canada’s non-profit and voluntary organizationworkforce in context

Source: 2000 National Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating;National Survey of Non-profit and Voluntary Organizations; International Labour

Organization; Report on Business Top 1,000, The Globe and Mail

Non-profitsector

includinghospitals,

universities,and colleges

Volunteeringa tradition in this family

DINA O ’MEARAS p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a l

CALGARY

Volunteering is a given for the Ea-glespeaker family, whether they’rehelping out during an event, or sit-ting on a board of directors — or twoor three boards.

Whiley and Au-tumn Eaglespeakerare immersed inbettering the livesand future of abo-riginal people, fol-lowing the exampleset by their uncleCasey Eaglespeak-er, a renownedaboriginal educa-tor, and mom Di-ane Eaglespeaker, afamily and housing advocate withthe Aboriginal Resource Centre Asso-ciation.

“In the aboriginal community,when somebody needed something, Iwould make myself available,” Dianesays. “I had lots of help to raise myfamily when I needed it.”

Raised in a traditional Blackfootfamily, Diane brought her childrenback to the Blood reserve in South-ern Alberta in the mid 1980s fromSeattle, where her father had moved

the family some 30 years earlier tokeep them out of residential schools.

Calgary’s aboriginal populationjumped 16 per cent between 1996and 2001, according to StatisticsCanada. Now numbering more than22,000 in a city of just under a mil-lion people, Calgary’s native resi-dents are among the most educated

and influentialrepresentatives oftheir peoples in Al-berta.

Linked to thisgrowth is a risingneed for services,from housing tohealth care. As co-ordinator of theTipi of CourageHIV/AIDS aware-ness program,

Whiley, 29, trains “warriors” to fightfor people’s health, by teaching themhow to protect themselves againstthe disease.

The stigma around HIV/AIDS is ahuge stumbling block for educationand prevention, something the Tipiof Courage is changing. Between 20and 60 volunteers are active at atime, with more than 150 on the calllist, including elders and advisors.

“From my perspective, aboriginalvolunteering is absolutely necessary

for this type of program to run,”Whiley says.

The program reached more than6,000 people in Alberta and Ontariolast year, and Whiley became the firstaboriginal to receive the YMCA PeaceMedal for his efforts.

Autumn, 27, admits she first ap-proached volunteering as a way tobeef up her resume.

“Now I want to help my community,I want to do more for people. My

mom really taught us to care aboutfamily and give back to the commu-nity. Because there have been timesthat we really struggled, and therewere people to help us.”

A volunteer on several boards likeher mom and brother, Autumn isnow working with the City of Calgaryto organize its first Aboriginal Aware-ness Week. She also works on pro-grams that help span the cultural, so-cial and economic gap natives experi-

ence when migrating to urban cen-tres from reserves.

Another goal for the political sci-ence grad from Mount Royal Collegeis to educate aboriginal people aboutvoting and participating in the demo-cratic process.

“There’s such a stigma about feder-al anything,” she says. “There’s a lotof distrust. But if you want to get so-cial issues changed, the best way is towork from within.”

Building on their elders’ example, mother andchildren serve the First Nations community

THE HERALD

Autumn, Whiley and Diane Eaglespeaker in the downtown Calgary offices of the Aboriginal Resource Association Centre

“Now I want to help mycommunity, I want to do

more for people. … Becausethere have been times that

we really struggled, and therewere people to help us.”

Autumn Eaglespeaker

DIDYOU

KNOW?

VOLUNTARY SECTOR WORKFORCE

Canada’s charitable and not-for-profit sector, excluding hospitals, universities and colleges,represents:x 4.0 per cent of the national gross domestic product;x 1,016,856 full-time equivalent paid employees;x 524,489 full-time equivalent volunteers;x 9.0 per cent of the economically active population;x 10.2 per cent of nonagricultural employment

Including hospitals, universities and colleges, the sector represents:x 8.5 per cent of the Canada’s GDP;x 1,524,032 full-time equivalent paid employees;x 549,000 full-time equivalent volunteers;x 12.1 per cent of the economically active population;x 13.2 per cent of nonagricultural employment

S o u r c e : I m a g i n e C a n a d a

THE HERALD, FILE

Keith Seel, director of the Institute for Nonprofit Studies at the Bissett School of Business at Mount Royal College, Calgary

E5KE5CYE5MAGE5YEL

S H A R I N G T H E I R W E A L T H100 YEARSOF GIVING

The Edmonton Federation ofCommunity Leagues consists of42 leagues. By 1916, there will be146 member community leaguesin the EFCL.

First World War begins. With 45,136men serving overseas, Albertansrepresented one of the highest volunteerenlistment rates in Canada.

S o u r c e : w w w. a b h e r i t a g e. c a

19141913

The Fort SaskatchewanWomen’s Institute isformed to assist the Red Cross in its war relief effort.

1915

EDMONTON JOURNAL WEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2005 E5

Early women’svolunteerism set the stage

CHRISTOPHER SPENCERS p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a l

EDMONTON

Alberta may be famous for mascu-line symbols such as untamed cow-boys and greasy roughnecks, but themost prosperous province in one ofthe world’s most prosperous coun-tries was built as much by Martha asby Henry.

Mind you, therewas one big differ-ence: she didn’tget paid for herwork.

During theprovince’s forma-tive years, volun-teering was one ofthe few sociallysanctioned activi-ties available towomen outsidethe home. Thehardships of set-tlement, depres-sion and twoworld wars wereovercome by rely-ing on the vitalityof the “weaker”sex.

Some of the vol-untary organiza-tions womenjoined became theprogenitors of so-cial movements that promoted equalrights. The range of opportunitiesavailable in today’s paid workforce isa product of time freely given bywomen in the past.

A history of volunteerism shouldbegin by noting that the concept ofmutual help was a fundamental char-acteristic of native societies. Settlersquickly picked up upon the impor-tance of co-operation, as survival inthe harsh climate only proved possi-ble through joint effort.

In her 1852 memoir, Roughing It inthe Bush, Susanna Moodie recordedthat the pioneer experience pro-duced an uncommon spirit of kind-ness.

“The Canadians are a truly charita-ble people; no person in distress isdriven with harsh and cruel languagefrom their doors; they not only gen-

erously relieve the wants of sufferingstrangers cast upon their bounty, butthey nurse them in sickness, and useevery means in their power to pro-cure them employment. The numberof orphan children yearly adopted bywealthy Canadians, and treated inevery respect as their own, is almostincredible.”

Among the first women to ventureinto the westernwilderness werethe Sisters of Chari-ty, popularlyknown throughoutthe prairies as theGrey Nuns. Formost of the 19thcentury, this Ro-man Catholic or-der, founded byMarie-Marguerited’Youville in 1737,provided the onlyhealth care avail-able to the majorityof the people livingin Alberta. Not justvolunteer nurses,the Grey Nuns wereskilled administra-tors, and many ofthe organizationsthey created con-tinue as part of themodern medicalsystem.

As settlement in-creased, protestant women con-tributed to improvements in healthcare, social services and education byjoining missionary societies. Theyworked to alleviate poverty amongimmigrants and natives, but their ral-lying cry, “Christianize and Canadi-anize,” does not pass the test of mod-ern political correctness.

By 1912, about one in every eightCanadian women belonged to an or-ganization, religious or secular, thatwas exclusively female and which in-cluded a service component. Some ofthese societies, such as the Women’sChristian Temperance Union, arguedthat moral and social reform couldonly be achieved by invoking thepower of the state. Prohibition advo-cates subsequently emerged as lead-ers in the universal suffrage move-ment.

During the First World War, womengot the vote and the province wentdry.

With so many men serving over-seas, housewives put their domesticduties aside and voluntarily assumedtasks to keep the home front fromfalling into disarray. The St. JohnAmbulance and the Canadian RedCross provided free medical care tocivilians and wounded soldiers.Women collected clothes forrefugees, knit socks for the boys inthe trenches and raised funds to fi-nance hospitals and purchase mili-tary equipment.

Their efforts during the SecondWorld War were equally impressive.Nearly 50,000 Canadian womensigned up to join the Women’s Volun-tary Services. A further 45,000 en-listed in the military, releasing menfor combat by assuming administra-tive, clerical and communicationsduties. In both wars, women servedclose to the front lines in nursing sta-tions.

Until the oil discovery at Leduc in1947, the population of the provinceremained largely rural and agrarian.The United Farm Women of Albertaaddressed the problem of isolation byproviding an outlet for social contact,but also undertook dozens of projectsto improve the common good.Women took the lead in areas such asproviding agricultural education, de-veloping shelter belts, buildingschools and hospitals and lobbyingthe government to improve socialservices.

One of the most spectacular ruralvoluntary initiatives took shape inMyrnam, 200 kilometres east of Ed-monton, during the Great Depres-sion. Money was scarce so residentsof the District of Ukrainia built a hos-pital using volunteer labour. Itopened on July 28, 1938, and provid-ed free services with the exception ofovernight hospitalization, which cost$2 per day.

The Myrnam project is today recog-nized as one of the steps leading touniversal health care.

Urbanization, the trend for the last60 years, has not erased volun-teerism from the Alberta identity.People living in this province aremore likely to volunteer than otherCanadians. Women continue to takethe lead, accounting for 57 per centof the unpaid workforce.

Unfortunately, prosperity has notresolved the problems that tradition-ally inspired Albertans to take volun-tary action. Poverty continues de-spite the expansion of governmentsocial programs. Immigrants still facechallenges adjusting to Canadian so-ciety.

Prohibition did not eliminate vio-lence within families. Illiteracy, childabuse and access to health care arestill prominent political issues.

It would seem the concept of mutu-al help is as relevant for modern Al-bertans as it was for the pioneers.

Women’s voluntary organizations led the way for social movements that promoted equal rights

Philanthropy’s next generation

MELANIE COLLISONS p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a l

CALGARY

Venture capitalists seek out bud-ding enterprises with great ideas, butwho are short on cash. With theirbacking, an entrepreneur can grow abusiness to realize its full potential.

For the past 31⁄2 years, a group ofCalgarians have been learning to be“venture philanthropists.”

High-tech graph-ics entrepreneurBrad Zumwaltbrought the ven-ture philanthropymodel to Canadafrom Seattle fiveyears ago. Likeventure capital-ists, the partnerscontribute time,business expertiseand financial backing.

As venture philanthropists, howev-er, the partners help not-for-profit or-ganizations achieve their goals.

Writing a cheque is just the first stepin their relationship with a not-for-profit, says Social Venture PartnersCalgary executive director CammieKaulback. Contributing personally isat least as important. “It can changethe way they think about giving.”

“Before I got involved with SocialVenture Partners I hadn’t really got-ten involved with volunteer work atall,” says board member Ruth Capin-dale, who learned the ropes by acting

as SVPC’s lead partner, or liaison,with a couple of not-for-profits.

“My husband and I chose SocialVenture Partners because we wantednot only to donate some funding, butshare our experience with some ofthe non-profits, which would be agood learning experience for us.”Capindale’s husband is a financialadviser who was also new to volun-teering.

“It’s been very rewarding (becauseof) the level of ap-preciation the orga-nizations show,and seeing whatcan happen whenyou pull someoneout of the businesscommunity andput them in touchwith a non-profit.”

Harry Yee, CEOfor Calgary Bridge

Foundation for Youth, credits thePartners for helping his not-for-profitoutreach organization fulfil its poten-tial.

Their support has allowed Yee toexpand Bridge’s community-basedprograms for immigrant children. Asa result, Bridge’s clients are learningto integrate into Canadian culture.

“They have been an unbelievablepartner,” Yee says.

“Before they joined us we were onour own lonely little island. It was sohard to get help because there are somany organizations. I make one callto them, they send an e-mail to their

network, and they find someone whocan provide assistance. It (builds)confidence to do a lot more becausethere are people behind you.”

Besides providing seed money,SVPC members guided the founda-tion’s strategic plan and organiza-tional structure. Various volunteershave helped with technology, policiesand financial software.

“They learn about the needs of anon-profit, the challenges,” Kaulbacksays. “We bring skills to the table, butthe learning is definitely a two-waystreet as people start to understandthe (not-for-profit) community andhow they can have an impact.”

On May 25, the venture philan-thropy group will celebrate reachingthe million-dollar investment mark.

“There are lots of senior philan-thropists in this town giving a lot ofmoney back, but when we’re talkingabout our million, we’re talkingabout people who have pooled theirmoney together,” Kaulback says.

“Some have made a lot of money,some are middle-class. We are al-ways looking to get more people in-volved. We’re trying to educate a fu-ture generation of philanthropists.How do you learn to be a good giver,especially if it’s new money?

“It’ll be interesting to see, in 10 or20 years, if the people from ourgroup are the leaders in the philan-thropic community. This is a safetraining ground.”

“There are educational sessionsthroughout the year,” Capindale

says. “I enjoyed doing it with my hus-band.

“It was valuable that we had an un-derstanding of what each other wasdoing.”

SVPC is already launching its ownnext generation of philanthropists.The partners’ children and teenagershave raised and given away $2,500,

based on the youngsters’ own evalua-tion of grant applications.

“Our partners are seeking out thatfeeling of doing important work,”Kaulback says.

“They are getting an intangiblething back that could be more valu-able than money.”

O n t h e N e t : w w w. s v p c a l g a r y. o r g

Safe training ground for ‘venture philanthropists’ connects their talents,financial backing with not-for-profit organizations

PHOTOS: COURTESY GLENBOW ARCHIVES

St. John Ambulance Voluntary Aid Detachment vehicle, in Edmonton, circa 1918

Red Cross workers perform a final check before shipping blood from theBlood Donor Clinic in Calgary to Winnipeg, during the Second World War.

Members of the United Farm Women ofAlberta at a Better Baby Show, in

Parkland, 1922

“The Canadians are atruly charitable people; no person in distress isdriven with harsh and

cruel language from theirdoors; they not only

generously relieve thewants of suffering

strangers cast upon theirbounty, but they nurse

them in sickness, and useevery means in their power

to procure thememployment.”

Susanna Moodie, in her memoirRoughing it in the bush

“We bring skills to the table, but the

learning is definitely a two-way street … .”

Cammie Kaulback

TED JACOB, THE HERALD

Social Venture Partners Calgary member Ruth Capindale is partnered with ServantsAnonymous Society and works with numerous other not-for-profit organizations,

including Fireworks Cooperative.

CHRISTOPHER SPENCERS p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a l

EDMONTON

A box of chocolates doesn’t go veryfar these days, when billion of dollarsare needed annually to sustain Cana-da’s growing not-for-profit sector.

Growing demand coupled with in-creasing competition has given rise tothe fundraising professional. Weasked independent consultants andrepresentatives from organizationslarge and small to talk about the chal-lenges and rewards of trying to gen-erate revenue for a worthy cause.

How has fundraising changedin the past 20 years?

x Paul Nahirney, president of Ed-monton-based consulting firm Nahir-ney and Associates and a fund-devel-opment instructor at Grant MacEwanCollege: “When I started out, interms of education, there would beseminars and workshops. Now youfind graduate-level programs. Youcan do a master’s degree. The Univer-sity of Indiana is thinking about im-plementing a PhD program. Thenumber of people in the field has justgrown tremendously. The number oforganizations needing to raise mon-ey has also increased dramatically.”x Julie Hamilton, senior develop-ment officer at the University of Al-berta and president of the Edmontonchapter of the Association ofFundraising Professionals: “There’s agrowth in the need by various chari-table organizations to hire fundrais-ers. One of the challenges we’ve seenin the sector is the decrease in gov-ernment funding for some of the pro-grams. As a result, organizationshave been compelled to includefundraising as part of their opera-tional planning.”x Gloria Stewart, direct marketingspecialist and president of Calgary-based Touchworks Communications:“We still use direct mail for acquisi-tion purposes. It’s just getting moreand more costly. As the privacy lawcame into force, some mailing listswent right off the market becausethey were not compliant. The cost ofrental lists has really started to in-crease, and then you’ve got your costof postage, print and production. Theeconomics are making it more andmore difficult to justify, but what oth-er resources do you have to feed yourpool of prospects?”

How do you make a cause standout amid all the noise and clutter?

x Stewart: “It’s important to make acompelling argument for why an or-ganization deserves to be funded.You have to make sure you are clearlystating what the mission of your or-ganization is and how the money isgoing to benefit someone.

“You can’t fall into the trap of beinggimmicky. That’s always a danger,particularly in direct mail. There’s al-ways a lot of formulaic direct mail,and I think there is a lot of evidenceto say that it works. In our organiza-tion, we use a lot of those techniques.But we don’t want to insult donors’intelligence. We have a pretty educat-ed population in Alberta, so I don’twant to talk down to people. But weneed to use clear language to makethe point.”x Michelle Regel, executive directorof the Calgary EMS Foundation:“The competition is something that’salways going to be there. Whetheryou’ve got more or less competition isso hard to gauge. It’s really a matterof focusing in on the target audiencesand working with them. I think thereis always going to be money for theorganizations that prove meaning-ful.”

Is there room amid the largeorganizations for small groups to

compete and survive?

x Hamilton: “I know that there is aperception about the university,that we’ve been seen as being like abig fishing trawler that can geteverything. We have a variety of lev-els of expertise on board, but we haveput resources behind it. We havehired fundraising staff. We do get ex-posed to very high-level donors be-cause of the kind of work that we’redoing. But that’s because this organi-zation has put money into fundrais-ing. Fundraising is an important partof the organization.”x Cherie Klassen, executive directorof the Alberta Council for Global Co-operation: “There are opportunitieswhere groups of charitable organiza-tions can work together, like theGreat Human Race, where peoplecan run for the charity of theirchoice. You need something to at-tract people to your particular cause.Celebrities work well, even localcelebrities.

“Things that provide an opportuni-ty to build community also work.When I was at Change for Children,we did something called Instrumentsfor Change, and we had a wholenight of ethnic music and silent auc-tions. Bill Bourne, Paul Bellows andother local celebrities played. It of-fered an opportunity to have peopleengaged in what we’re actually do-ing, rather than just sending in acheque.”x Regel: “Our run is unique becausewe do it at night. We line the pathwith our ambulances and we put allthe lights on, so people can run bythe lights of the ambulances. Wehave 500 to 600 people come outwith their dogs and their kids. It’s avery nice time.”

Are there fundraising strategiesthat are overrated?

x Nahirney: “In capital campaigns,where I spend most of my time, mostof the energy is devoted to solicitinggifts from individuals. Most peopledon’t appreciate that roughly 88 percent of all money that’s contributed

year to year comes from individualgifts. Too many people make assump-tions about corporations. The placeto concentrate your efforts is on indi-vidual donors, because that’s wheremost of the money comes from.”x Klassen: “I think people get reallytired of phone solicitation. I don’tknow from personal experiencewhether it works well or not, but itwouldn’t be a method of choice forme. I know the level of annoyancewith all of the phone solicitors is go-ing up.”x Stewart: “I think if you are respon-sible in the way you conduct telemar-keting, it can be very valuable. I’mnot a proponent of doing acquisitionsthrough telemarketing. I think that ifyou are using the phone to renew ex-isting relationships or to ask donorsto join a monthly giving program, Ithink you are going to see less resis-tance.”

What are some of the ethicaldilemmas that arise in fundraising?Hamilton: “The biggest factor that

we’ve been challenged with is per-centage-based compensation. Wewant to approach fundraising in away that will promote sustainabilityand encourage people to support or-ganizations and feel really goodabout the cause.

“If we get fundraisers who saythey’ll help you raise money, buttheir fee is 10 or 15 per cent of the to-tal raised, then we question whosemission is in the forefront. We advo-cate that if an organization was goingto hire a fundraiser, that personwould be on salary.

“We need to ensure that people askquestions of people soliciting funds,so that the profession isn’t under-mined but more importantly thecharitable sector doesn’t get a blackeye. We’re very focused on trying toensure that the charitable sector isstronger through our practices. Wewant to be sure that people are givingtheir money freely through philan-thropic mechanisms, that the moneyis in fact going where it is supposedto be going and that we are hon-ourable. Not everyone in the charita-ble sector is honourable, as in all sec-tors.”x Klassen: “One of the many ethicaldilemmas that charitable organiza-tions face is: do we take gaming mon-ey? That’s a really big one. Gamingmoney is easy. You can go out to acouple of bingos or casinos and makequite a bit of money. But if you’reworking in the public interest or forthe public good, and you are takingin sources of income that really harmthe most vulnerable people in our so-ciety, well, there are charitable orga-nizations that will refuse that moneybecause of the ethical dilemma. Iknow that a lot of our faith-based or-ganizations refuse gaming money.”x Nahirney: “One of the things I dowith my clients very early in the

process is to have them sit down anddeclare what their values and beliefsare, and to govern themselves ac-cordingly. If they have a problemwith being involved with gaming ac-tivities, so be it. They shouldn’t pur-sue it. It gets a little trickier whenpeople start looking at should wetherefore not accept money fromthose who have used gaming to raiseit. If you look at most service clubs,for example, many of them are in-volved in gaming activities to raisetheir funds.

“I also encourage organizations totake a look at the corporate sector.Based on their program, they mightnot be able to be affiliated with cer-tain companies. An obvious examplewould be cancer- or health-relatedorganizations accepting funds fromthe tobacco industry. You just can’tdo that.”x Stewart: “If you are going to printsomething, make sure you can sub-stantiate it. If something happens inone area, for sure it is going to cloudpeople’s suspicion. People are morecynical than they have been before.We all have to mind our Ps and Qs.”

Is it hard not to get caught up in thebusiness side of things and lose

sight of the goal of helping people?

x Nahirney: “I try not to think toomuch in terms of strategy, more interms of relationship building. If youlook at the definition of philan-thropy, translated literally it meanslove of mankind. There’s no refer-ence to money at all.

“I think sometimes we get toowrapped up in developing strategiesand being focused on the bottomline; that we’re losing sight of what isthe most important item, which is de-veloping true and genuine relation-ships with people who have ex-pressed an interest in your particularcause, and trying to nurture that rela-tionship over a period of time.”x Klassen: “If you can combinefundraising with educational efforts,you are giving meaning to why youare raising the money.”x Hamilton: “It’s not just about ask-ing people for $300. It’s about askingpeople to become part of your orga-nization in a meaningful way. Thefundraiser’s role really is connectingdonors with the causes that are im-portant to them.”

Cash-starved agencies call in the pros

E6KE6CYE6MAGE6YEL

S H A R I N G T H E I R W E A L T H100 YEARSOF GIVING

There are 134 communityassociations registered with theFederation of CalgaryCommunities, the city’s largestvolunteer group.

Alberta’s volunteer helpingorganizations were strained whenthe Spanish Flu pandemic sweptthrough the province in 1918,resulting in 4,000 deaths.

19181917

Throughout the winter and into 1920, theAlberta Red Cross gives 46,000 articles ofclothing to 1,000 needy families in theprovince’s southern drybelt, hit hard bysuccessive droughts and recession.

1919

E6 WEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2005 EDMONTON JOURNAL

IAN SCOTT, THE JOURNAL, FILE

Charitable organizations can work together to raise funds, as in the Great Human Race, where people can run for the charity of their choice.

F U N D R A I S I N G R O U N D T A B L E

“ If you cancombine fundraising

with educationalefforts, you are givingmeaning to why you

are raising themoney.”Cherie Klassen

Alberta Councilfor Global Cooperation

“ If you lookat the definitionof philanthropy,

translatedliterally it means

love ofmankind.There’s no

reference tomoney at

all.”Paul Nahirney,

presidentNahirney and

Associates

“ It’s not just aboutasking people for $300.

The fundraiser’s role reallyis connecting donors with

the causes that areimportant to them.”

Julie Hamilton,Association of Fundraising

Professionals, Edmonton chapter

JOHN LUCAS, THE JOURNAL

Cherie Klassen

Government fundingcuts have spawned

professional fundraisers

ED KAISER. THE JOURNAL

Paul Nahirney

GREG SOUTHAM,THE JOURNAL

JulieHamilton

SUPPLIED

Michelle Regel

LEAH HENNEL, THE HERALD

Gloria Stewart

x In 2003-04, the provincialgovernment derived $1.2 billion ingambling revenue to support theAlberta Lottery Fund.x Charities directly earned a further$226 million from licensed gamingactivities, including $133 million fromcasinos.x More than 9,800 groups are eligibleto conduct bingos, casinos, pull-ticketlotteries and raffles in Alberta.x Between four and eight per cent ofteenagers are estimated to have aserious gambling problem. Nearly 80per cent of high school studentsgamble for money every year.x The Alberta Knights of Columbusand the Edmonton Food Bank areamong the groups that haveannounced they will no longer raisemoney through casinos due to ethicalconcerns.x Over three-quarters of Canadians(79 per cent) think charitiesunderstand the needs of Canadiansbetter than government.x Seven in 10 (72 per cent) thinkcharities do a better job thangovernment meeting the needs ofCanadians.x 57 per cent agree charities shouldbe expected to deliver programs andservices the government stopsfunding.x 70 per cent think charities have toolittle money to meet their objectives.

S o u r c e : Ta l k i n g A b o u t C h a r i t i e s2 0 0 4 , M u t t a r t Fo u n d a t i o n ,

A l b e r t a G a m i n g ;M c G i l l U n i v e r s i t y

BETTING IT ALL

E7KE7CYE7MAGE7YEL

S H A R I N G T H E I R W E A L T H100 YEARSOF GIVING

In Calgary, the Red Cross, SalvationArmy, Associated Charities andImperial Order of the Daughters ofthe Empire regularly hold “tag days”to raise money to help the indigent.

Edmonton’s Christmasstocking for the needyreceived $1 million indonations from the city’spopulation of 65,163.

1926

The first SalvationArmy seniors’residence, or EventideHome, is opened inEdmonton.

19261920

On Oct. 29, or BlackThursday, the U.S. stockmarket crash heralds thebeginning of the GreatDepression.

1929

EDMONTON JOURNAL WEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2005 E7

Can Alberta’s social deficit be tamed?CHRISTINE PEAKE BREMNER

S p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a lEDMONTON

A decade ago, the federal andprovincial governments decided toconquer the mountain of public debt.They tightened the purse strings, cut-ting programs and spending to thebone. Alberta is now debt-free andrunning surplus budgets; the federalgovernment, while still paying downthe national debt, is also in a surplusposition. The dragon of debt is cow-ering in its cave.

A hatchling was left behind: agrowing social deficit. Alberta’s vol-unteers were quick to fill some of thegaps in health care, education andsocial services. But has their willing-ness to act created the expectationthat volunteers will continue to pro-vide essential services, trading freetime for lower taxes?

The first volunteer groups to feelthe impact of income assistance re-ductions were the province’s socialservices agencies.

“When the social welfare programchanged in 1993 to ’96, we saw an in-crease in the number of people need-ing our services,” says Marjorie Benz,executive director of Edmonton’sFood Bank.

“We now have a booming economy,yet at the same time, we have an in-creasing number of people needingthe food bank. These are not onlypeople who receive social assistance,they are the working poor. We seethe best, and the worst: the public atits most generous, and the peoplewho fall through the gaps of everysocial safety net.”

Between 12,000 and 15,000 drawon the hamper program everymonth, says Benz, and 143 volunteeragencies (including churches) screenand refer those in need to the FoodBank.

The Bissell Centre in Edmonton’sinner city is one of those agencies.Ele Gibson, resource development di-rector, succinctly sums up the prob-lem: “More people, needing moreservices, more often.”

Community Development MinisterGary Mar, who’s responsible for thevoluntary sector, was not availablefor comment.

“The minister pursued increasedfunding for the voluntary sector inthe last budget, and is already work-ing towards next year’s budget,” saidspokesperson Cheryl Robb.

“As a government, we did allocatefunding to organizations in whichvolunteers work: health care, educa-tion, and aid to the disadvantaged.”

Health care certainly relies on thegenerosity of Albertans. This sum-mer, tens of thousands will walk, jog,run, swim, cycle and paddle to raisefunds for medical research. Manymore will buy lottery tickets to sup-port hospital improvements andequipment purchases and keep airambulances flying. And volunteerswill donate their time to assist andsupport patients and their families inhospitals and nursing homes.

Nearly 4,000 volunteers in Calgaryand area contributed 257,334 hoursof service in 2003-4, and throughhospital gift shops, raised $726,752,says Joan Addison, manager of vol-unteer resources for Calgary’s Alber-ta Children’s Hospital, Grace

Women’s Health Centre and Rock-yview General Hospital. Figures aremuch the same in the Capital HealthRegion, where some programs at theUniversity and Stollery Children’sHospital are so popular, they have awaiting list for volunteers.

Five years ago, Susan Beugin tookearly retirement and began volun-teering at Alberta Children’s Hospitalas a baby cuddler. She describes herwork as “very joyful. It’s enormouslysatisfying, everyone is very apprecia-tive, and you know you make a dif-ference.” Beuginusually volunteersthree days a week,three hours eachday.

A generation ago,the sight of a par-ent in the schoolsignalled a calami-ty. Today, parentschaperone fieldtrips, help in class-rooms on specialprojects, assist inthe office to checkon absentees, andserve on parent advisory commit-tees, though neither the CalgaryBoard of Education nor EdmontonPublic Schools tracks the number ofvolunteers or the hours they serve.

The Partners for Kids program, be-gun at Norwood elementary schoolin downtown Edmonton, is a part-nership between Success by 6, TheCentre for Family Literacy, and theFamily Centre, says Diane Betkowski,a retired teacher and the program’sco-ordinator.

“It’s a one-on-one program with anadult mentor, who spends 45 min-utes to an hour a week with a child,working on reading skills and build-ing cognitive skills.”

Norwood has 105 mentors, and theprogram has been expanded to Ab-bott elementary and Parkdale juniorhigh. Brea Murray, 21, was in her firstyear studying elementary education

at the University of Alberta when shestarted mentoring a young girl atNorwood three years ago.

“I love it,” she says. “My student ishappy to see me, and I feel that I’vehelped her make progress with herreading.”

The police services of Edmontonand Calgary both depend on volun-teer assistance.

Edmonton introduced its VictimService Unit, staffed by volunteers, in1979. The unit’s aim is to comfort thefamilies and victims of crime-related

trauma and assistthem in dealingwith the criminaljustice system, saysSgt. Bob Pagee,volunteer co-ordi-nator.

All applicants arerequired to under-go the samescreening as policeofficers, and areasked to commit toone year of service.The unit has 139trained volunteers

who work at least one three-hourshift a month.

Volunteers also staff the front coun-ters in community police stations andpatrol their communities as addition-al “eyes on the street,” says Const.Joe Spear, volunteer co-ordinator inthe south-side office.

Realtor Shami Sandhu spendsmany evenings with the Mill WoodsCommunity Patrol. He and fellowvolunteers use their own vehiclesand pay for their own gas, while citypolice provide a radio to link themwith a police officer.

“It’s made a difference,” says Sand-hu, who’s also president of the MillWoods’ Presidents Council.

“We keep an eye on local wateringholes and community functions, aswell as driving through residentialareas.”

Patrol members also pitch in for

special events such as Grey Cup andthe Klondike Days parade.

In Calgary last year, 828 volunteerscontributed over 67,000 hours to po-lice programs.

“If you counted the number of gov-ernment departments who dependon volunteers to help them do theirjobs, you’d be hard-pressed to find adepartment that doesn’t,” says ValMayes, executive director of the Ed-monton Chamber of Voluntary Orga-nizations.

The chamber is a member of theFramework for Action Group, whichcomprises a number of leaders fromthe voluntary and not-for-profit sec-tor who meet almost monthly withrepresentatives of the Ministry ofCommunity Development.

“The fact that there is such a groupis progress, and that they meet withus regularly is a good thing,” Mayessays.

“But it takes time to build a formalrelationship between the govern-ment and the voluntary sector, andthis group is trying to work out across-departmental understanding ofthe impact of the voluntary sector.”

In a speech to the Calgary Chamberof Voluntary Organizations in Febru-ary, Gary Mar acknowledged thepressures facing voluntary organiza-tions.

“However, even an enhanced roleas a funding partner will never takethe place of committed individualsand voluntary organizations workingin their communities,” he said.

“We do not want your job. We wantto help you to do it.

“One answer to rising demand maywell be more money, and I know youwill be creative in attracting it. Youwill need to be. There is only a finiteamount of money out there.”

Albertans have been amazinglywilling to give their time and theirmoney when they perceive a need.The question that remains is this: willthe social deficit dragon devour Al-berta’s volunteers?

Government’s determination to conquer the public debt left volunteers to step in and fill the gap in services

JIMMY JEONG, THE JOURNAL

Shami Sandhu runs a volunteer community patrol in Mill Woods. The full-time realtor useshis own car and pays for his own gas to help keep the streets of his neighbourhood safe.

Chrysalis clients give back to their community

JAC MACDONALDJo u r n a l S t a f f W r i t e r

EDMONTON

Stan Fisher has seen plenty of heart-warming transformations occur withmentally handicapped and develop-mentally disabled clients at Chrysalis:AnAlbertaSociety for Citizens withDis-abilities.

But the society’s president and chiefexecutiveofficer has also seenChrysalisclients create heartwarming transfor-mations in other people.

“Thesekinds of stories willbring tearsto your eyes,” he says.

Chrysalis helps mentally handi-capped adults integrate into the work-force or places them in volunteer posi-tions in not-for-profit organizations.Some clients with multiple handicapsattend life skills programs.

A common job is assisting seniors in

long-term care centres and nursinghomes. They help perform simple butvaluable tasks like escorting seniors tomedicalappointments or to thehair sa-lon. They also chat and kibitz withthem. It brings seniors out of theirshells, Fisher says.

For example, “Mary, who was neverconcerned about her personal appear-ance,now looks forward togoing to thebeauty parlour andgets dressedfor theoccasion.”

Last year, Chrysalis clients donated70,000 hours in127 different volunteersites, from helping seniors at St.Michael’s LongTermCareCentreinEd-monton, to feeding the animals andcleaning cages at the Calgary SPCA.

The society was launched in Edmon-ton in 1968 as the Western IndustrialResearch and Training Centre to helptrain mentally handicapped adults togive them a role in the community.

Vocational services, job trainingin thecommunity, and employment wereadded in the mid-1980s.

“We want to show that our clients cangive back to the community,” Fishersays.

Chrysalis serves 450 clients a year in

Edmonton and 200 a year in Calgary,helping them get into jobs as varied asthelaundry at Dow Chemical, recyclingat aFortis warehouse,or packagingma-terials at an auto parts distributor.

TheChrysalis CharitableFoundationassists the Chrysalis Society by raisingmoney to support its programs.

The foundation holds two major an-nual fundraising events, Spring Inspi-

rationinCalgary and theWesternMar-di Gras in Edmonton.

The society has also ventured into itsown entrepreneurial activities. Thewoods division builds custom palletsandcrates,and theplastics divisionpro-duces plasticbottles in various sizes.Allsales support Chrysalis programs andservices for citizens with disabilities.

j m a c d o n a l d @ t h e j o u r n a l . c a n w e s t . c o m

Citizens with disabilitiesventure into workforceand volunteer efforts

‘Everybodyknows about

Brooks in Kenya’DINA O ’MEARA

S p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a lBROOKS

Daba Beranda fled his home coun-try of Ethiopia in 1996, seeking asy-lum as a 26-year-old student from apolitical regime that had impris-oned, tortured and killed many ofhis compatriots. For six months heshared scant food supplies andprimitive shelter with 20,000 othersin an East African refugee camp be-fore being sponsored to Canada bythe International Red Cross.

Volunteers with immigrant aidesocieties in British Columbia helpedBeranda acclimatize, showing himhow to find a place to live, go formedical help, even how to use a to-ken when changing buses. The over-whelming support from perfectstrangers touched Beranda, who, onmoving to Alberta, started workingin the public sector to help immi-grants like himself.

“As a new Canadian, it’s my obliga-tion to help others and counselthem, help them integrate intoCanadian society,” he says, fromBrooks’s Global Friendship Centre.

Today, Beranda acts as liaison offi-cer at the centre, working with agroup of approximately 150 volun-teers to provide information andsupport to a continuous flow ofnewcomers to the small prairietown. The centre organizes orienta-tion programs, provides English as aSecond Language courses, and oth-er projects to explain the often baf-

fling differences between southernAlberta and African culture.

“Once you start volunteering withpeople of other cultures, it justopens up the world,” Doreen Med-way, centre executive director, saysof her work.

Immigrants represent more than aquarter of Brooks’s population, anestimated 3,500 people out of12,000 residents. Almost three-quarters of the newcomers are fromAfrica, 48 per cent of those from Su-dan. The change to southern Alber-ta from the Dark Continent consti-tutes much more than living in a dif-ferent country, one refugee said.“It’s like moving from one planet toanother,” he told Medway.

Many suffered through terrifyingordeals before reaching the sanctu-ary of Canadian soil. They come tothe centre numb, shell-shocked sur-vivors with horrifying tales that canburn out the brightest volunteer ifnot vigilant against being caught upin the sadness, Medway says.

One program that has provenhighly successful at bringing the dif-ferent cultures together in a healingway has been a community garden.“We try to educate both sides,” shesays. “Immigrants get to plant theirfood, we introduce them to ours, it’sreally a good way of mixing Canadi-ans and newcomers.”

Immigrants flock to Brooks be-cause of readily available jobs atLakeside Packers, a beef-processingplant on the outskirts of town.When asked how he had heardabout the town, one refugee said,somewhat incredulously: “Every-body knows about Brooks inKenya.”

Another bonus is the establishedAfrican community, which Medwaysays has brought the town alivethrough its vibrant cultures. Newbusinesses have started opening,catering to newcomers but that allresidents can enjoy, like grocerystores catering to African tastes, andnew restaurants.

Town council has been mindful ofhow the influx of new culturescould impact residents, but racist in-cidents are much more of an issuewithin the immigrant communitythan with white Canadians, Med-way notes. Refugees come to Brooksfrom both sides of warring coun-tries, bringing with them deeply in-grained prejudices and conflictsthat often spill out on the prairielandscape.

The volunteers at the centre worktoward instilling a sense of toler-ance and acceptance among thenewcomers as part of Canada’s mul-ticultural society.

“I was used to living in fear,” Be-randa says.

“Now I have a place to work, live,study. Canada is a free society, so it’sreally, for me, I’m born again.”

“We now have abooming economy, yet

at the same time, we havean increasing number of people needing the

food bank.”Marjorie Benz, executive director

Edmonton’s Food Bank

JOHN LUCAS, THE JOURNAL

Tamara Favaro with Chrysalis president and CEO Stan Fisher

“ It’s like moving fromone planet to another.”African refugee resident of Brooks

E8KE8CYE8MAGE8YEL

S H A R I N G T H E I R W E A L T H100 YEARSOF GIVING

Drought, grasshopperinfestations, windstormsand fires leave much ofsouthern Alberta abarren wasteland.

The Calgary Salvation Army, inan appeal for funds, reports itprovided 29,776 free mealsand 10,900 temporary jobs inthe previous year.

1930

SecondWorldWarbegins.

1939

Volunteer initiatives include victory bond sales,and community drives to collect paper, rubberand scrap metal for the war effort. Women’sauxiliaries form to collect donations for hospitals,the armed forces and European war victims.

1940s1930s

E8 WEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2005 EDMONTON JOURNAL

Professionalathletes step up

to the plate

CHRISTOPHER SPENCERS p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a l

EDMONTON

Alberta’s professional athletes makea common man’s wage, but they havean uncommon commitment to thecommunity.

Salaries for football players start at$35,000. A rookie on a lacrosse teamearns as little as $8,000. (The NewYork Yankees are paying third base-man Alex Rodriquez $25,705,118.)

It might seemspecial to somepeople that ath-letes drawingmodest salariesare willing to do-nate time to chari-table causes — butthey don’t thinkso.

“We’re all put ina position to helpout anyway wecan with any char-ities that we can,and I think being a professional ath-lete you are thrust into the position ofbeing able to do things,” says JamieCrysdale, a Calgary Stampeder offen-sive lineman who has played in theCFL for 12 seasons. “You can basical-ly become involved in as many thingsas you want because the opportuni-ties are there.”

“I’m a Christian man and I believein giving back and helping out a tonwhere I can and when I can,” agrees

Rocky Thompson, the popular en-forcer for the Edmonton Road Run-ners hockey club. “I have a family ofmy own, and I want to be a positiverole model. I want the young com-munity to look up to me in a sense.Not to be narcissistic or anything likethat, but I want to help out and I’m inthat position.”

It’s a position that became more im-portant last season, when a labourdispute shut down play in the NHL.Several Oiler players left for Europe,

leaving localgroups with adearth of celebri-ties.

“Whether there’sa lockout or thereisn’t, I’ve alwaysbeen involved inthe community,”Thompson says.“This is a great op-portunity for mein Edmonton toperhaps get outeven more, be-

cause there has maybe been more ofa need.”

The Calgary-born defenceman wasone of the most visible contributorsto the 2004 Christmas Bureau cam-paign.

“I actually got some hands on, wasable to give out the gift certificates tothe people that needed them. Thatwas a really rewarding feeling, to seethe look when they got the stuff. Thatwas really awesome.”

For Edmonton Eskimo quarterbackJason Maas, getting involved in theteam’s Stay in School program was away of integrating into the communi-ty. Before signing his first CFL con-tract in 2000, he played college foot-ball at the University of Oregon.

“I wanted to have a home and stayin a place year-round. I like Edmon-ton so much that it made it very easyfor me to do that,” says Maas, whogrew up in Arizona.

He finds time to meet with studentsat about 40 schools during the wintermonths.

“You want to leave them with thelasting impression that school is im-portant, that leading is importantand that being a good person in thecommunity is important. I feel this isthe most important thing I do, get-ting out in the community and talk-ing to kids.

“I try to do just about anything peo-ple ask me to do. I’m really open to it.I don’t say no too often. In the off-season, I’m pretty much fair game.”

Tracey Kelusky’s volunteer activitiesalso include speaking to the childrenabout the importance of school. Ascaptain of the Calgary Roughneckslacrosse team, he says it is criticalthat his teammates be seen helpingout where they can.

“We’re trying to build the sport tothe next level. The guys know thattheir job is not just to play but to pro-mote the game,” says Kelusky, whoalso contributes to Right to Play, anorganization that brings sports tochildren living in refugee camps.

Crysdale, the brawny Stampederlineman, has a special motivation forhis efforts as a fundraiser on behalf ofthe Kids Cancer Care Foundation ofAlberta.

On May 20th, 2004, he had a hell ofa day.

He was getting ready to go seeAerosmith in concert at the Saddle-dome when his wife told him that shewas pregnant with their third child.

Five hours later, he was at the Al-berta Children’s Hospital with his

three-year-old daughter, Grace. Shehad just been diagnosed withleukemia.

Last September, Crysdale and hiscolleagues on the Stampeders raised$15,128 for the hospital’s cancer unitthrough a Shave Your Lid for a Kidcampaign. After her father’s appoint-ment with a set of clippers, Gracewasn’t the only one in the familywithout hair.

“I didn’t even have to ask guys toparticipate,” he remembers. “Theywere more than willing to step upand show their support that way.”

After several months of chemothera-py, Grace’s leukemia seems to be un-der control. She and her brother,Thomas, have a new sister: Annabella.

Daddy’s hair is not growing as fastas his family.

“I’ve kept it short,” reports Crys-dale, who also serves as a spokesmanfor the Calgary Urban Projects Soci-ety. “It’s easier to manage that way. Iwas losing it, so this gave me an ex-cuse to get rid of it all.”

Players believe their role in their communities goes beyond their modest paycheques

Community league movement facing new challengesCHRISTINE PEAKE BREMNER

S p e c i a l t o Th e Jo u r n a lEDMONTON

They have different names acrossthe country: community associa-tions, residents’ associations, neigh-bourhood associations and commu-nity leagues. Nowhere do they flour-ish more strongly than in Edmontonand Calgary.

Edmonton was the first city inCanada to form a community league:the 142 Street District (now Crest-wood) in 1917. It was described asnon-sectarian and non-political(meaning non-partisan) “open toboth sexes on equal conditions,” withthe aim to better the communitythrough social and recreational op-portunities. By 1921, there were ninecommunity leagues and the Edmon-ton Federation of CommunityLeagues was formed to provide sup-port. Today, 147 community leaguesserve the citizens of the city.

The first Calgary community associ-ations were formed in the 1920s tocreate recreational programs and fa-cilities, such as outdoor skating rinks.The Federation of Calgary Communi-ties has served the city’s communityassociations for over 50 years,though it was not officially incorpo-rated under the Societies Act until1961. There are currently 134 regis-tered community associations in Cal-gary, created from 183 communitydistricts.

All these leagues and associationsare operated by volunteers. Whilebookkeepers, ice makers or rink at-tendants may be paid for their ser-vices, the executive board and com-mittee members donate their timeand energies to run the programs,

community halls, skating rinks andsports fields. As in many volunteerorganizations, fundraising absorbsmuch time and effort. It’s affectingthe viability of some leagues and as-sociations and their ability to attractand retain volunteers.

Programs at riskAccording to Russ Dahms, execu-

tive director of the EFCL, “About athird of the leagues are doing well,with the community engaged and in-volved; another third are doing okay,and the final third are struggling.This can be attributed to a number offactors but, primarily, they are theage of the neighbourhood and its vol-

unteer base, the age of its infrastruc-ture, and the programs they’re ableto offer.” Adds Don Kuchleyma, im-mediate past president of the EFCL:“The successful ones have financialstability.”

For many leagues, rising utility andinsurance costs mean a constantcampaign to keep the doors of theircommunity halls and skating rinksopen. “This reduces the ability ofleagues to offer programs, whenfundraising efforts go to basic operat-ing costs,” notes Shane Bergdahl,EFCL president. “We may still be ableto offer skating or soccer and keepthe lights on, but we may have to sac-rifice the dance classes.”

Brenda Brown, executive director ofthe FCC, concurs: “Many associationsare struggling to meet operatingcosts. Many of them are using casinosand bingos, and they’re heavily re-liant on gaming funds to keep going.”Both cities provide funding, butgrants seldom keep pace with costs.

“Money for specific projects is easyto get,” Kuchleyma explains. “Youcan sell that you’re putting a brick ina wall, but it’s difficult to get peopleto commit to keeping the lights onand the buildings warm.”

Says Edmonton mayor StephenMandel: “I agree that we need tocome up with better ways to free upour volunteers to do the work theyneed to do rather than paying for op-erating costs.” City departments arereviewing this issue, and will reportto council on June 4.

Bob Lang, president of the FCC,states: “Communities deal with gen-eral issues, as opposed to specialneeds, and this often doesn’t fit need-specific funding. All levels of govern-

ment have to recognize while not-for-profit organizations can provide ser-vices cheaper, it still costs money.While corporate Canada has steppedin to help, it hasn’t replaced the fund-ing that was available.”

Shane Bergdahl feels that raisingthe profile of the community leaguescan help to attract new funding andmore volunteers. “Communityleagues do a lot of things that the ma-jority of Edmontonians don’t knowabout.

“The leagues were the foundationfor the School Patrol. The majority ofplaygrounds in the city were builtand paid for by community leagues.Without leagues, we would not havemany of the city’s recreational facili-ties — Millwoods Recreation Centreand the skateboard park, for exam-ple.”

In both cities and across theprovince, minor hockey, minor soccerand zone baseball grew out of themovement. In a changing landscape,the community movement has re-mained constant, thanks to the ef-forts of generations of volunteers.