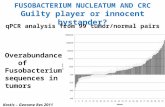

Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

Transcript of Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

Does Miranda Protect theInnocent or the Guilty?

Steven B. Duke*

Miranda v. Arizona' is probably the most widely recognizedcourt decision ever rendered. Thanks to movies and television,people the world over know about "Miranda rights." Govern-ments around the globe have embraced Miranda-like rights.Suspects in South Korea must receive their "Miranda warning"before being interrogated.2 So must those in Mexico,3 Canada,4and most European countries.5 Miranda's notoriety surely hassomething to do with the decision's kaleidoscopic symbolism. Tosome, Miranda embodies the respect due to criminal suspects. 6

* Professor of Law, Yale Law School. This article is an elaboration of remarks made

at the Chapman Law Review Symposium: Miranda at 40: Applications in a Post-Enron,Post-9/11 World (Jan. 26, 2007). I am indebted to Theresa Cullen, Sarah Raymond andGeoffrey Starks for their research assistance.

1 384 U.S. 436 (1966).2 The Korean Constitution protects the right against self-incrimination and Korean

courts have held that, in "the Korean version of Miranda," police must advise suspects oftheir right to silence prior to interrogation. If police fail to do so, any resulting statementis inadmissible. Kuk Cho, The Unfinished "Criminal Procedure Revolution" of Post-Democratization South Korea, 30 DENV. J. INT'L L. & POL'Y 377, 383 (2002).

3 The Political Constitution of the Mexican United States, art. 20, provides that thedefendant has a right not to be compelled to give a statement and to be informed of hisright to remain silent. It further provides that any "confession rendered before whateverauthority destined by the Public Minister or the judge, or before these without the assis-tance of counsel of any value shall be prohibited." INSTITUTO FEDERAL ELECTORAL,POLITICAL CONSTITUTION OF THE MEXICAN UNITED STATES 14 (1994).

4 Craig M. Bradley, The Emerging International Consensus as to Criminal Proce-dure Rules, 14 MICH. J. INTIL L. 171, 198 (1993).

5 See generally Craig M. Bradley, Mapp Goes Abroad, 52 CASE W. RES. L. REV. 375(2001) (surveying the rules in more than ten countries); Gordon Van Kessel, Quieting theGuilty and Acquitting the Innocent: A Close Look at a New Twist on the Right to Silence,35 IND. L. REV. 925 (2002).

Throughout Europe, there is near-universal recognition of a right to si-lence ... that applies to both the pretrial and trial stages of a criminal case.Those aspects of the right ... that require advice of the right and prohibit ad-verse inferences from silence also are generally accepted. Most civil law coun-tries of continental Europe have adopted rules that require suspects be in-formed of the right to remain silent prior to questioning as well as rules thatprohibit courts from considering [a] defendant's silence as evidence of guilt ....

Id. at 926.6 "Miranda ... allows us to celebrate our values of individualism without paying

any real price. As a cultural symbol, Miranda stands for the enshrinement of individualrights over the needs of the state for efficiency, equal justice for rich and poor before thelaw... " Patrick A. Malone, "You Have the Right to Remain Silent' Miranda after

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 551 2006-2007

552 Chapman Law Review [Vol. 10:551

To others, it represents the professionalism of the police.7 Stillothers regard Miranda as a glaring example of the SupremeCourt's ambivalence toward law enforcement, its lack of respectfor victims, and its willingness to "coddle criminals."8 Constitu-tional lawyers cite Miranda as an example of judicial usurpationof the legislative domain.9 And so on.

Rather than musing about the symbolic meaning ofMiranda, I want to examine a more mundane, yet eminentlypractical, question: whether Miranda protects the innocent, theguilty, or neither. That is an empirical question that we cannotanswer with entirely convincing proof; we can only debate andopine, which we have already been doing for more than four dec-ades. It is hard to conjure any other subject that has so occupiedlaw reviews, television dramas, talk shows, and op-eds. It maynow be impossible to say anything original on the subject andsince I have read only some of the debates, I can make no claimhere of originality.'0 Nonetheless, some answers seem clearenough that we should focus our concern about confessions in

Twenty Years (1986), reprinted in THE MIRANDA DEBATE: LAW, JUSTICE, AND POLICING 75,85 (Richard A. Leo & George C. Thomas III eds., 1998).

7 See Stephen J. Schulhofer, Miranda's Practical Effect: Substantial Benefits andVanishingly Small Social Costs, 90 Nw. U. L. REV. 500, 504 (1996).

8 See, e.g., Maxwell Bloomfield, The Warren Court in American Fiction, 1991 J. SUP.CT. HIST. 86 (1991), available at http://www.supremecourthistory.org/04_library/subs_volumes/04_c09_l.html; Richard A. Rosen, Reflections on Innocence, 2006 WiS. L.REV. 237, 244 ("Looking at the ensuing criticism of the decision, one would think that theCourt had opened the prisons and handed guns to departing murderers.").

9 See, e.g., U.S. DEP'T OF JUSTICE, OFFICE OF LEGAL POLICY, REPORT TO THEATTORNEY GENERAL ON THE LAW OF PRETRIAL INTERROGATION: 'TRUTH IN CRIMINALJUSTICE' REPORT NO. 1 (1986), reprinted in 22 U. MICH J.L. REFORM 437, 543 (1989)("Miranda violates the constitutional separation of powers and basic principles of federal-ism. Miranda's promulgation of a code of procedure for interrogations constituted a usur-pation of legislative and administrative powers... "); Dickerson v. United States, 530U.S. 428, 457-61 (2000) (Scalia, J., dissenting).

l0 In an effort to be original, some supporters and critics alike stretch pretty far.Daniel Seidmann and Alex Stein, for example, spend eighty pages arguing that when theguilty exercise the right to silence they help the innocent: if the guilty had to talk, theywould lie and their lies would make factfinders more skeptical of the innocents' truthfuldenials. Thus, even though the right to silence directly protects the guilty, it indirectlyprotects the innocent as well. Daniel J. Seidmann & Alex Stein, The Right to SilenceHelps the Innocent: A Game-Theoretic Analysis of the Fifth Amendment Privilege, 114HARv. L. REV. 430, 433-34 (2000). Professor Cassell floated a somewhat contradictorytheory, that if the police are stymied in their efforts to obtain confessions from the guilty,they will wring false confessions from the innocent. Ergo, they should be freer to obtainconfessions from everyone. Paul G. Cassell, Protecting the Innocent from False Confes-sions and Lost Confessions-and from Miranda, 88 J. CRIM L. & CRIMINOLOGY 497, 498-99 (1998). For responses to Seidmann & Stein, see Stephanos Bibas, The Right to RemainSilent Helps Only the Guilty, 88 IOWA L. REV. 421 (2003) and Van Kessel, supra note 5, at930-31. For a response to Cassell, see Richard A. Leo & Richard J. Ofshe, Using the In-nocent to Scapegoat Miranda: Another Reply to Paul Cassell, 88 J. CRIM L. &CRIMINOLOGY 557 (1998).

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 552 2006-2007

Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

other directions. We should give Miranda a rest.Part of what fuels the vast literature about Miranda are the

multitudinous meanings of the subject of the debate. When wespeak of Miranda, are we referring to the opinion of the WarrenCourt in June 1966, which was a mini-treatise on the hows andwhys and the good and bad of police interrogation, or to thewarnings that Miranda requires the police to give suspects dur-ing custodial interrogation? Do we also include in that referencethe Court's directives about how the police should respond whenthe suspect invokes his rights? And do we include what theCourt said about how the trial court should deal with variouseventualities?11 Since most of Miranda's dicta have been disre-garded by courts and the police in the four decades since the casewas decided, should we disregard that dicta as well when debat-ing the present-day impact of Miranda?12

In contemplating Miranda's effects on convicting the guiltyand the innocent, we might also ask what assumptions we aremaking about how the legal landscape relating to police interro-gation would look today if Miranda had never been decided, or if,as some have been seeking for four decades, it had been over-ruled.

In some of the debates, Miranda is regarded as havingclearly established (or "invented," some would say) the FifthAmendment's applicability to police interrogation. But that isuntrue. Brain v. United States did that in 1897, when the Courtsaid, "[W]herever a question arises whether a confession is in-competent because not voluntary, the issue is controlled by [theself-incrimination] portion of the Fifth Amendment.. .. "13 TheCourt reaffirmed the Brain position in Malloy v. Hogan,14 whichpreceded Miranda. If we assume, as some of Miranda's criticsastonishingly do, that before Miranda was decided, the policewere free to compel a suspect to answer their questions,15 we

ii For example, the Court said that the prosecution could not use as evidence at trialthe fact that the suspect declined to submit to interrogation, Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S.436, 468 n.37 (1966), and could not use a confession obtained without a waiver of theMiranda rights. Id. at 475-76.

12 For some of that dicta, see infra note 18.13 168 U.S. 532, 542 (1897).14 378 U.S. 1, 7-8 (1964).15 See, e.g., Joseph D. Grano, Selling the Idea to Tell the Truth: The Professional In-

terrogator and Modern Confessions Law, 84 MICH. L. REV. 662, 683-84, 686 (1986) (re-viewing FRED E. INBAU & JOHN E. REID, CRIMINAL INTERROGATION AND CONFESSIONS(1962)) (noting that historically, the Fifth Amendment only applied to formal judicial pro-ceedings, not to out-of-court investigations, so whatever the police did in interrogationswas not "compelled" self-incrimination within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment). Seealso the famous refutation of these claims in Yale Kamisar, Equal Justice in the Gate-

2007]

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 553 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review [Vol. 10:551

might attribute to Miranda some substantial curbs on police ac-tivities and a reduction in confessions. But if the only innovationwe attribute to Miranda is the duty it imposed on the police todeliver the four-part advisement of rights and to respect the sus-pect's express desire to cut off questioning, a very different con-clusion about Miranda's effects might emerge. In attacks onMiranda as criminogenic or at least hindering law enforcement,the critics are rarely clear about what version or interpretation ofMiranda they find so friendly to felons.

Professor, now Judge, Paul Cassell is in the vanguard ofMiranda's critics, writing a dozen or more law review articles at-tempting to prove that Miranda was not only misguided, butperverse. 16 Unlike some of his allies, Paul Cassell is reasonablyclear about the Miranda that he is criticizing, at least in his morerecent articles on the subject. It is the skeletal Miranda that hasemerged after decades of judicially-inflicted erosion, a Mirandathat requires no more than the four-part warning and the rightto cut off questioning.17 That was not the Miranda that policethought they were trying to comply with in the immediate wake

houses and Mansions of American Criminal Procedure: From Powell to Gideon, FromEscobedo to .... in CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN OUR TIME 1, 19-36 (A.E. Dick Howard ed.,1965). See also Stephen A. Saltzburg, Miranda v. Arizona Revisited: Constitutional Lawor Judicial Fiat?, 26 WASHBURN L.J. 1, 14 (1986) (arguing that the drafters of the Self-Incrimination Clause could not have intended to prohibit judges from compelling self-incrimination, but to permit other officials to do so in secret sessions without any judicialprotection). Miranda also declared that the prosecution could not use as evidence at trialthe fact that the suspect declined to submit to interrogation. 384 U.S. at 468 n.37. Thisextended to the police station the Court's earlier ruling in Griffin v. California, 380 U.S.609, 615 (1965), that no adverse inference can be drawn at trial from the suspect's exer-cise of his Fifth Amendment right.

16 See, e.g., Cassell, supra note 10, at 503; Paul G. Cassell & Bret S. Hayman, PoliceInterrogation in the 1990s: An Empirical Study of the Effects of Miranda, 43 UCLA L.REV. 839, 842-43 (1996).

17 Since Cassell has himself proposed a set of warnings which include the right tosilence, his major objection is not to the warnings themselves but to the suspect's right tocut off questioning. See Cassell & Hayman, supra note 16, at 859 ("[I]t appears that mostof Miranda's harms stem from the cutoff rules, not the more famous Miranda warnings.").Cassell's own data suggest, however, that suspects rarely cut off questioning after theyhave made their initial "waiver." In Cassell and Hayman's study of interrogations inUtah, 83.7% of interrogated suspects waived their rights and only 3.9% changed theirminds later. Id. at 860. See also similar data cited in note 19, infra. Cassell's objectionsto Miranda might therefore appear almost trivial were it not that he also wants to permitthe police to continue to interrogate and cajole suspects who invoke their rights at anypoint in the process, whether from the outset or later. Paul G. Cassell, Miranda's SocialCosts: An Empirical Reassessment, 90 Nw. U. L. REV. 387, 497 (1996). In effect, Cassell'sproposal would tell the police that they need not respect the suspect's right to silence andcan ignore his attempts to invoke it. Such disrespect for the suspect's Miranda rights hasnever enjoyed support in the Supreme Court. Rather, fairly strict enforcement of the cut-off rules has been the norm. See, e.g., Michigan v. Mosley, 423 U.S. 96, 106 (1975); Ari-zona v. Roberson, 486 U.S. 675, 686-87 (1988); Minnick v. Mississippi, 498 U.S. 146, 156(1990).

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 554 2006-2007

2007] Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

of the decision. Many thought that Miranda made lawful inter-rogation almost impossible.i8

I. THE LIKELY IMPACT OF No MIRANDA WARNINGS

In the interest of clarity, let us speculate about only onething: what would be the likely effect on police interrogation, andon convicting the innocent and the guilty, if America repudiatedthe international movement that it spawned and told the policenot only that they were not required to warn suspects of theirrights, but that they were forbidden to do so?

About four out of five custodial suspects in the United Stateswho are asked to submit to interrogation do so, while one in fivedeclines. Those who decline usually do so when warned initially,but occasionally do so later in the course of the interrogation.19Paul Cassell claims that the Miranda warnings cause suspects toclam up (or at least to not confess) and that, as a result, manycriminals avoid conviction. Professor Cassell even asserted that"Miranda may be the single most damaging blow inflicted on the

18 The Miranda opinion clearly contemplates that in the typical police interrogationthe suspect will have counsel at his side. If that were the case, there would be very fewinterrogations. Many statements in Miranda created uncertainty about the continuingviability of custodial interrogation: "[The very fact of custodial interrogation exacts aheavy toll on individual liberty and trades on the weakness of individuals," Miranda v.Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 455 (1966); "Our aim is to assure that the individual's right tochoose between silence and speech remains unfettered throughout the interrogation proc-ess .... A mere warning given by the interrogators is not alone sufficient to accomplishthat end," Id. at 469-70; "[A] heavy burden rests on the government to demonstrate thatthe defendant knowingly and intelligently waived his privilege against self-incriminationand his right to retained or appointed counsel," id. at 475; "If authorities conclude thatthey will not provide counsel.. . they may refrain from doing so without violating the per-son's Fifth Amendment privilege so long as they do not question him during that time,"id. at 474; "Whatever the testimony of the authorities as to waiver of rights by an accused,the fact of lengthy interrogation or incommunicado incarceration before a statement ismade is strong evidence that the accused did not validly waive his rights," id. at 476;"[Any evidence that the accused was threatened, tricked, or cajoled into a waiver will, ofcourse, show that the defendant did not voluntarily waive his privilege." Id. As it turnedout, none of these statements has current vitality in the courts, but they caused difficul-ties in police interrogation in the first few years after Miranda was decided.

19 See Richard A. Leo, Inside the Interrogation Room, 86 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY,266, 302 (1996) [hereinafter Leo, Inside the Interrogation Room]; Cassell, supra note 17,at 495-96. Although the Court in Miranda stated that the suspect has the right to termi-nate questioning at any time, 384 U.S. at 445, 476 n.45, the Court did not require thatthe suspect be informed of that right and the police rarely add that bit of advice to thewarnings. Whether for that reason or others, if suspects do not invoke silence at the out-set, they rarely change their minds and terminate the interrogation midstream. See Pro-ject, Interrogations in New Haven: The Impact of Miranda, 76 YALE L,J. 1519, 1554-55(1967); Cassell & Hayman, supra note 16, at 860 & tbl.3; Richard A. Leo, The Impact ofMiranda Revisited, 86 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 621, 653 tbl.1 (1996) [hereinafter Leo,The Impact of Miranda Revisited] (stating that of 182 Mirandized suspects, 38 invokedtheir Miranda rights but only 2 of those did so after an initial waiver).

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 555 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review

nation's ability to fight crime in the last half century."20

Professor Stephen Schulhofer and others have taken issuewith Cassell's conclusions.21 Studies conducted after the policelearned to minimize Miranda's strictures and courts began to en-courage such minimization provide very little support for Cas-sell's analysis, most of which is based on "confession rates." Cas-sell says that the confession rates are somewhat lower in theUnited States than in England and Canada, where police havelong given pre-interrogation warnings that are less detailed thanthose required by Miranda.22 There are, of course, many factorsthat can influence confession rates that have nothing to do withthe content of a pre-interrogation warning or whether one wasgiven. Interrogation rates vary greatly among jurisdictions andpolice departments within the same state. If, for example, thepolice interrogate only people whom they have arrested andwhom they believe to be guilty, confession rates should be high.If, in contrast, the police frequently interrogate persons whomthey have not arrested or against whom they have little evidence,the confession rates will be lower. If police regard interrogationas merely a step in the investigation process, they are less likelyto experience a high confession rate than if they regard interro-gation as a phase of the prosecution.

Other reasons for variations in interrogation rates includedifferences in the interrogation expertise of the police, in the timeavailable to the police to conduct interrogations, and the urgencyor necessity of the interrogation. Interrogations occur only whenthe police feel a need to conduct them and are rare where theperpetrator is caught in the act or is in possession of contrabandor stolen property shortly after the crime.23 The need for a con-fession also varies with the nature of the crimes that are beinginvestigated, and those natures vary over time and jurisdictions.Many crimes simply are not serious enough to warrant custodialinterrogation. The difficulties of concluding, based on differencesin confession rates, that criminals are being helped by Mirandawarnings are insuperable.

20 Paul G. Cassell & Richard Fowles, Handcuffing the Cops? A Thirty-Year Perspec-tive on Miranda's Harmful Effects on Law Enforcement, 50 STAN. L. REV. 1055, 1132(1998).

21 Schulhofer, supra note 7, at 547 ("For all practical purposes, Miranda's empiri-cally detectable net damage to law enforcement is zero."). See also Richard A. Leo, Ques-tioning the Relevance of Miranda in the Twenty-First Century, 99 MICH. L. REV. 1000,1007-09 & nn.41-51 (2001); George C. Thomas III, Plain Talk about the Miranda Debate:A "Steady-State" Theory of Confessions, 43 UCLA L. REV. 933, 942-43 (1996).

22 See Cassell, supra note 19, at 418-22.23 See Cassell & Hayman, supra note 16, at 854-59 (exploring reasons why Utah po-

lice did not interrogate); Project, supra note 19, at 1582-93.

[Vol. 10:551

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 556 2006-2007

2007] Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

Some critics focus alternatively on the numbers or proportionof suspects who decline to converse with the police-those whoinvoke their right to silence. As noted, those rates hover aroundtwenty percent. 24 Some seem to assume that whoever refuses tosubmit to interrogation after being warned of his rights does sobecause of the warning. But that is the post hoc, ergo propter hocfallacy: temporal succession does not establish cause and effect.Some suspects refused to talk to the police before Miranda.25

Even before Miranda, physical coercion was rare in Ameri-can police departments.26 Thus, a pre-Miranda suspect, even ifnot informed of his right to silence, often knew that he could notbe forced to talk and that if he refused, he would suffer at mostan adverse inference and a lost opportunity to talk himself out oftrouble. When the Miranda warning regime began, the warningsdid not tell many suspects much, if anything, that they did notalready know.27 Possibly as many as twenty percent of suspectsin the pre-Miranda era invoked silence.28 More pertinent to thedebate today, however, is how many suspects would invoke si-

24 See Leo, Inside the Interrogation Room, supra note 19, at 302.25 Id. In the New Haven study, of 127 suspects, 20 immediately refused to talk and

18 asked to see a lawyer or friend before receiving any warnings. It is unclear whetherthe 20 who refused to talk were different than the 18 who asked to see a lawyer or afriend. If they were, then 30% of all suspects invoked their rights without warnings. Ifthey were the same suspects, then about 16% invoked their rights.

26 Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 446-48 (1966) (noting that in the time leadingup to Miranda, physical brutality was the exception, and that most coercion was psycho-logical); Project, supra note 19, at 1549.

27 A pre-Miranda suspect might have been unaware that his silence could not beused against him at trial, a rule declared in Miranda, id. at 468 n.37, but this is not partof the required Miranda warnings. Moreover, common sense suggests that whatever therule about adverse inferences at trial, the police will draw an adverse inference againstone who refuses to cooperate, and this is the adverse inference that is uppermost in thesuspect's mind.

28 See Project, supra note 19, at 1571 n.135 (between 16% and 30% of New Havensuspects invoked silence without being warned). In a pre-Miranda study in Philadelphiain 1965, out of 4801 persons arrested, 1550, or slightly less than 32%, "refused to give astatement." However, they were given some warnings, even before Miranda, so they can-not all be counted as persons who would have "refused to give a statement" without anywarnings at all. Controlling Crime through More Effective Law Enforcement: HearingsBefore the Subcomm. on Criminal Laws and Procedures of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary.90th Cong. 200 (1967) (statement of Arlen Specter, District Att'y of Phila.). In one Cali-fornia city, during a three-month period in 1960, detectives conducted interrogations of399 persons arrested for felonies. Of those, 58.1% gave confessions or admissions. Ed-ward L. Barrett, Jr., Police Practices and the Law-from Arrest to Release or Charge, 50CAL. L. REV. 11, 43 (1962). Barrett does not report how many of the other 41.9% talkedand how many refused but it would be surprising if most of that group submitted to inter-rogation but did not say anything incriminating. The scholarly literature on interrogationpractices and consequences pre-Miranda is surprisingly sparse. See Ronald H. Beattie,Criminal Statistics in the United States-1960, 51 J. CRIM. L._ CRIMINOLOGY & POLICESC. 49 (1960); Caleb Foote, Law and Police Practice: Safeguards in the Law of Arrest, 52Nw. U. L. REV. 16, 17 (1957).

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 557 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review [Vol. 10:551

lence if police stopped warning suspects of their rights. Thatnumber could approach, or, paradoxically, even exceed thetwenty percent who now invoke silence after receiving warnings.

It nonetheless seems almost certain that Miranda warningsdo cause some suspects to reject interrogation.29 Some, perhapseven most, of those silence-invoking suspects are guilty.30 Even ifwe further assume that because they invoke silence, some ofthose guilty suspects avoid conviction,31 it still does not followthat the net effect of Miranda warnings is to impede convictingthe guilty.

We must also consider the possibility that the warnings ac-tually induce some suspects to talk rather than to remain silent.The warnings implicitly suggest to the suspect that the police arerespectful of the suspect's rights, that the police are not only law-abiding, but that they are also fair and objective. If deliveredwith the proper tone, the warnings could even suggest to thesuspect that the investigators are sympathetic, naive or gulli-ble.32 Surely Patrick Malone is right that "[s]killfully presented,

29 See Project, supra note 19, at 1571 tbl.17. This would seem to be true even if thewarnings impart no new or significant information to the suspect. They do at least intro-duce the issue of silence and make it easier for the suspect to invoke silence than if therehad been no mention of the matter by the police, requiring the suspect to raise the issuehimself.

30 There is, as far as I am aware, no evidence that virtually everyone who invokessilence is guilty, as is sometimes assumed by scholars. See, e.g., Seidmann & Stein, supranote 10, at 503. There is evidence that suspects with felony records are much more likelyto invoke silence than those whose records are clear, see Leo, Inside the InterrogationRoom, supra note 19, at 286, but concluding that they are more likely to be guilty becausethey have criminal records seems unwarranted. A different conclusion does seem justi-fied: they invoke silence more often because their previous experience with the policetaught them the advantages of silence. See William J. Stuntz, Miranda's Mistake, 99MICH. L. REV. 975, 993 (2001). While it will often end up to his advantage to cooperatewith law enforcement, the guilty suspect should rarely cooperate without a quid pro quo.Hence, it is usually unwise for guilty suspects to cooperate during custodial interrogation.Nonetheless, about 60% to 80% of suspects who submit to interrogation end up confessingor making incriminating statements. See, e.g., Leo, Inside the Interrogation Room, supranote 19, at 281; James W. Witt, Non-Coercive Interrogation and the Administration ofCriminal Justice: The Impact of Miranda on Police Effectuality, 64 J. CRIM. L. &CRIMINOLOGY 320, 326 tbl.3 (1973).

31 There appear to be no studies correlating silence-invoking with conviction, i.e.,what proportion of those who invoke silence are not convicted. Nor do there appear to beany studies attempting to show what proportion of those silence invokers are factuallyguilty.

32 Since courts are permissive in allowing the police to preface the warnings withtheir own observations and even to intermix their own observations with the warnings,see, e.g., Duckworth v. Eagan, 492 U.S. 195, 201-05 (1989), the police can suggest duringthe warning process that they are sympathetic to the suspect, that the victim "got whatshe deserved" or "I would probably have done the same thing." This signals to the suspectthat he is among sympathetic interrogators. The belief, or hope, that they can talk theirway out of trouble is a major motivator for suspects to submit to interrogation. See SaulM. Kassin & Rebecca J. Norwick, Why People Waive Their Miranda Rights: The Power of

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 558 2006-2007

20071 Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guiltv?

the Miranda warnings themselves sound chords of fairness andsympathy at the outset of the interrogation. The interrogatorwho advises, who cautions, who offers the suspect the gift of afree lawyer, becomes all the more persuasive by dint of his ap-parent candor and reasonableness."33 If a cop tells the suspectthat he need not answer, that he can have an attorney if hewants, is that not reassuring? The Court repeatedly said so in itsMiranda opinion.34 The Court's notion that a mere warningwould transform the interrogation from one of "inherent coer-cion" to an occasion for the suspect "to tell his story without fear"was astonishingly naive, since the warnings lose most of what-ever significance they have once the interrogation begins.35However, there was some truth to the Court's observation thatthe warnings serve to reassure and calm the suspect into waivinghis rights at the outset of the interrogation. The warnings mayalso increase the suspect's bravado during the early stages of in-terrogation, which of course facilitates the interrogators.36 So,against the guilty who are induced not to talk by the warnings,we have to compare the guilty who are induced to talk.3T Whichis the larger group? Nobody knows. It seems reasonable to

Innocence, 28 LAw & HUM. BEHAV. 211, 215-16 (2004); George C. Thomas III, Miranda'sIllusion: Telling Stories in the Police Interrogation Room, 81 TEX. L. REV. 1091, 1111(2003) (reviewing WELSH S. WHITE, MIRANDA'S WANING PROTECTIONS (2001)). For othertechniques police use to encourage waivers, see Leo, supra note 21, at 1019.

33 Malone, supra note 6, at 79. A similar point is made in George C. Thomas III, IsMiranda a Real-World Failure? A Plea for More (and Better) Empirical Evidence, 43UCLA L. REV. 821, 831 (1996).

34 The Court suggested that the warnings would "relieve the defendant of the anxie-ties [the police] created in the interrogation rooms," 384 U.S. 436, 465 (1966), would en-able him "under otherwise compelling circumstances to tell his story without fear, effec-tively, and in a way that eliminates the evils in the interrogation process," id. at 466, andare "an absolute prerequisite in overcoming the inherent pressures of the interrogationatmosphere." Id. at 468.

35 "[O]nce suspects agree to talk to the police, they almost never call a halt to ques-tioning or invoke their right to have assistance of counsel." Stuntz, supra note 30, at 977."Once the interrogator recites the fourfold warnings and obtains a waiver ... Miranda isirrelevant to both the process and the outcome of the subsequent interrogation. Any pro-tection that Miranda might have offered a suspect typically evaporates as soon as an ac-cusatory interrogation begins ...." Leo, supra note 21, at 1015. See also supra note 19.Miranda's naivet6 has often been repeated by the Supreme Court. In Davis v. UnitedStates, for example, the Court said, "[T]he primary protection afforded suspects subject tocustodial interrogation is the Miranda warnings themselves" and that "comprehension ofthe rights to remain silent and request an attorney [is] sufficient to dispel whatever coer-cion is inherent in the interrogation process." 512 U.S. 452, 460 (1994) (quoting Moran v.Burbine, 475 U.S. 412 (1986)).

36 The New Haven study provides some support for this speculation. Law studentsobserved all police interrogations in New Haven during the summer of 1966. Suspectswho were warned of their rights made incriminating statements far more often (in 57% ofthe interrogations) than those who were not warned (30%). See Project, supra note 19, at1565. A major motivator for suspects to waive their rights is their hope that they can talkthemselves out of trouble. See supra note 32.

37 A similar point is alluded to in Thomas III, supra note 33, at 831.

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 559 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review

speculate, however, that after four decades of living withMiranda, the small number of suspects who are induced to re-main silent by the administration of the warnings is getting evensmaller while the number encouraged to talk is at least remain-ing stable.

Let us assume arguendo that the number of those induced toremain silent by the warnings exceed those who are induced totalk. If so, then the number of suspects who actually submit tointerrogation is somewhat reduced by the Miranda warnings-albeit much less than is commonly supposed.38 There is littlereason to assume that this number is more than three or fourpercent of those who are interrogated. Assuming such a net fig-ure, however, still does not answer the question of whether theguilty are helped or hurt by Miranda warnings.

If slightly fewer suspects submit to interrogation because ofMiranda warnings, there is no reason to doubt that those who dosubmit continue to confess or make incriminating statements (in-cluding provable lies) at the same or at a higher rate than wouldhave been the case without warnings.39 Once the police obtain awaiver, the trickery and psychological coercion that the Courtnoted in Miranda, together with any new interrogating trickslearned since then, can continue as before.40 As long as the policedo not physically torture the suspect or threaten him with imme-diate bodily harm, virtually anything goes. 41

II. THE COUNTERWEIGHT OF COGENCY

Assuming that a fraction of guilty suspects who would oth-erwise incriminate themselves do not do so because of theMiranda warnings, and that because they invoked their right toremain silent they cannot be convicted, there are two strongcounterbalancing effects of the warnings that almost certainly

38 Despite Miranda warnings, most suspects who are warned (78% to 96%) waivetheir rights. Richard A. Leo, Miranda and the Problem of False Confessions, in THEMIRANDA DEBATE, supra note 6, at 271, 275.

39 It is often assumed that the guilty are more likely to invoke silence than the inno-cent. See, e.g., Leo, Inside the Interrogation Room, supra note 19, at 279 n.71. If so, theremight be a slight reduction in the harvesting of incriminating statements if the proportionof silence-invokers were slightly increased by the giving of warnings. But that would betrue only if (1) the guilty make incriminating statements more often than the innocent(we certainly hope this is true!), and (2) the reduction in the numbers of suspects submit-ting to interrogation is not more than offset by the ill-advised bravado and garrulity thatthe warnings engender.

40 See Leo, supra note 21, at 1003.41 See Welsh S. White, Miranda's Failure to Restrain Pernicious Interrogation Prac-

tices, 99 MICH. L. REV. 1211 (2001).

[Vol. 10:551

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 560 2006-2007

Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

outweigh those losses.42 The first is the cogency effect of thewarnings and the waiver. A jury is more likely to believe that a

defendant's incriminating statements were truthful if he receivedMiranda warnings. One who receives warnings but nonetheless"waives" his rights to silence and to have a lawyer presentthereby makes his incriminating statements appear more clearlyvoluntary and reliable than if he made them without any warn-ings or waivers. According to the Miranda court, the warningsserve to dilute or even to eliminate the coercive nature of policeinterrogation.43 A Mirandized suspect who talks is arguably do-ing so without coercion, even if interrogated for half a day,44

whereas one who is not Mirandized is, according to the SupremeCourt, being interrogated in an "inherently coercive" atmos-phere.45 When coercion is seemingly eliminated or reduced, thesuspect's incriminating statements acquire more cogency. Al-though the Supreme Court's view of the power of a simple warn-ing to calm and comfort the suspect throughout a lengthy inter-rogation was extremely naive, prosecutors are free to make thesame argument to juries who will surely find it persuasive. Insum, although Miranda warnings may deter a small fraction ofsuspects from incriminating themselves, those who are not de-terred are more likely to be convicted because their incriminatingstatements acquire cogency from the warning and the waiver. Inits power to produce convictions, this cogency effect could out-weigh the evidence lost, if any, by the Miranda warnings.

Miranda's contribution to the cogency of a confession may beunnecessary, since juries are likely to believe a confession underalmost any circumstances.46 However, while confessions are ob-tained in many interrogations, they are by no means the typicalresult of an interrogation. According to Richard A. Leo's study of182 interrogations in the early 1990s, incriminating statements

42 The first counterbalancing effect is discussed in this Part. The second is discussedin Part III.

43 See Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 467 (1966). As the Court noted in Miranda,the pre-Miranda interrogation manuals suggested that if a suspect is reluctant to discussthe matter, he should be told that he has a right to remain silent and "[tihis usually has avery undermining effect. First of all, he is disappointed in his expectation of an unfavor-able reaction on the part of the interrogator. Secondly, a concession of this right to re-main silent impresses the subject with the apparent fairness of his interrogator." Id. at453-54 (quoting from FRED E. INBAU & JOHN E. REID, CRIMINAL INTERROGATION ANDCONFESSIONS 111 (1962)).

44 See State v. LaPointe, 678 A.2d 942, 949, 964 (Conn. 1996) (holding that confes-sions obtained from a suspect with a congenital brain defect during a nine-and-a-half hourinterrogation was voluntary, even though detectives wrote the confessions he signed).

45 Miranda, 384 U.S. at 467.46 See infra note 86.

2007]

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 561 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review

were obtained in 64%, but only 24% produced full confessions.47Thus, nearly two-thirds of the incriminating statements resultingfrom interrogations are not confessions and need the help of thecogency counterweight.

III. THE COUNTERBALANCING EFFECT OF MIRANDA ON JUDGES

A second weighty counterbalance is the effect that Mirandawarnings have on judges: psychologically, politically and doctri-nally. If warnings were delivered by the police and a waiver wasgiven or signed, it is almost impossible to persuade a judge thatthe resultant confession or admission is "involuntary."48 Thewarning/waiver not only helps to persuade the jury of the defen-dant's guilt, it helps the trial judge deny the defendant's motionto suppress.49 The focus of the pre-Miranda judicial inquiry hasbeen shifted from whether the confession was voluntary towhether the Miranda warnings were given and a waiver exe-cuted. This shift makes granting a motion to suppress difficultand makes denying it easy.50 I do not think the waiver addsmuch, if anything, to the voluntariness of a confession, but I amnot a judge who would be the target of the public clamor that in-evitably follows a judicial ruling suppressing incriminating evi-dence despite police compliance with Miranda. Miranda is asubstantial factor in the twenty-first century reality that thesuppression of confessions by trial judges on involuntarinessgrounds is almost as rare today as four-legged chickens.51

47 Leo, Inside the Interrogation Room, supra note 19, at 280.48 White, supra note 41, at 1220.49 As the Court observed in Dickerson v. United States, 530 U.S. 428 (2000), when

the police have "adhered to the dictates of Miranda," the accused can rarely make even "acolorable argument that a self-incriminating statement was 'compelled."' Id. at 444 (quot-ing Berkemer v. McCarty, 468 U.S. 420, 433 n.20 (1984)).

5o As Professor Leo notes, "[T]rial judges have learned to use Miranda to simplify thedecision to admit interrogation-induced statements and to sanitize confessions that mightotherwise be deemed involuntary if analyzed solely under the more rigorous FourteenthAmendment due process voluntariness standard." Leo, supra note 21, at 1027.

51 In a study of 7035 cases in three states, Professor Nardulli found only five (.07%)cases that were lost as a result of a court's suppression of a confession. Peter F. Nardulli,The Societal Cost of the Exclusionary Rule: An Empirical Assessment, 1983 AM. B. FOUND.RES. J. 585, 601. In a subsequent study of 2759 cases in Chicago, judges suppressed con-fessions in only .04% of all cases. Peter F. Nardulli, The Societal Costs of the ExclusionaryRule Revisited, 1987 U. ILL. L. REV. 223, 227, 232. In a Westlaw search of all federal andstate cases decided in 1999 and 2000, Welsh White found only nine cases in which thecourts held a post-waiver confession involuntary. Four of those cases were expresslybased on state law rather than the Due Process Clause. White, supra note 41, at 1219n.54. It seems likely, moreover, that violations of Miranda's warning and waiver ruleswere present in some of those cases. I asked a long-time trial judge recently if he hadever suppressed a confession. He said, with apparent pride, "yes." I asked him for thedetails and he explained that the police had questioned the suspect without administeringany Miranda warnings. "Did the State lose the case?" I asked. "No," he replied. "After

[Vol. 10:551

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 562 2006-2007

2007] Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

IV. DIMINISHED CONCERN FOR THE INNOCENT

Before Miranda, a major concern of the Supreme Court wasthe voluntariness of confessions. The Court was developing somerather stringent (if unclear) requirements on the admissibility ofconfessions.52 Miranda, however, has been a major contributor tothe demise of that concern and to an inversion of the law govern-ing involuntary confessions. Many confessions that would havebeen found involuntary in 1966 are considered voluntary today.

The currently-applied tests for voluntariness are less de-manding than the pre-Miranda tests. 3 Even more importantthan its articulation of voluntariness criteria is the message theSupreme Court sends to the lower courts in its case selection anddecision patterns. In the three decades prior to Miranda, theSupreme Court held that confessions were involuntary in at leasttwenty-three cases.54 In the four decades since Miranda, how-ever, the Court has decided only three voluntariness cases, andhas only held two confessions involuntary: Mincey v. Arizona55and Arizona v. Fulminante.56 The Court has also moved from avoluntariness test related to the reliability of the confession to adoctrine that explicitly rejects such a concern. Police misconduct,not reliability, is now the sole determinant of involuntariness.57

they got the confession, they Mirandized him and got another confession, which was ad-missible. He was convicted." Cf. Oregon v. Elstad, 470 U.S. 298, 300 (1985). For an espe-cially unusual case, an appellate ruling holding a confession involuntary, see Common-wealth v. DiGiambattista, 813 N.E.2d 516, 518 (Mass. 2004), where a conviction forburning a building, in which no one was injured, rested largely on the defendant's confes-sion, which was obtained through lies about nonexistent evidence, expressions of sympa-thy, and minimization of the offense with implicit offers of leniency. Perhaps four-leggedchickens are slightly more common than judicial findings of involuntariness. See Postingof Bart Dabek to Science & Technology, http://www.aboutmyplanet.com/index.php?s=four-legged+chicken (Mar. 15, 2007).

52 See generally Yale Kamisar, What is an "Involuntary" Confession? Some Com-ments on Inbau and Reid's Criminal Interrogation and Confessions, 17 RUTGERS L. REV.728, 741 (1963); Welsh S. White, What is an Involuntary Confession Now?, 50 RUTGERS L.REV. 2001, 2008-20 (1998).

53 Louis Michael Seidman, Brown and Miranda, 80 CAL. L. REV. 673, 745-46 (1992)(stating that because the Supreme Court is not interested in reviewing voluntarinesscases, "lower courts have adopted an attitude toward voluntariness claims that can onlybe called cavalier"); White, supra note 51, at 2009 ("[Plolice interrogators have in somerespects been afforded greater freedom than they were during the era immediately pre-ceding Miranda.").

54 White, supra note 41, at 1220.55 437 U.S. 385, 401 (1978).56 499 U.S. 279, 282 (1991). The third case was Colorado v. Connelly. 479 U.S. 157,

159 (1986), discussed infra.57 Professor Godsey observes that prior to Miranda, the Court in its voluntariness

decisions emphasized the subjectivities of the suspect, such as his age, background,strength of character, and mental condition at the time of the interrogation, but Mirandamade these concerns virtually irrelevant to its "waiver" questions. Mark A. Godsey, Re-thinking the Involuntary Confession Rule: Toward a Workable Test for Identifying Coin-

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 563 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review

Although the Court in Miranda took full note of the coercivepressures of custodial interrogation and the effectiveness of psy-chological coercion, including the power to obtain confessionsfrom the innocent,58 the remedy the Court fashioned to counter-act those pressures is almost totally ineffective. In what has be-come essentially a faux remedy, the Miranda warning regimehas virtually replaced a vibrant and developing voluntariness in-quiry that took into account the vulnerabilities of the particularsuspect as well as the inducements and conditions of the interro-gation. As far as the Supreme Court is concerned, that protec-tion of the innocent has vanished from the law of confessions.

In its immediate aftermath, the Miranda decision was com-monly believed to do much more than prescribe a set of warningsand related rights. Some thought that defense lawyers wouldhave to be assigned to police stations and to participate in all in-terrogations.59 Many thought that this would virtually eliminateconfessions as tools for convicting the guilty.60 There is languagein the opinion that supported many of these fears and predic-tions.61 But none of them came to pass. As others have noted incountless law review articles, the courts have pretty much cutthe flesh out of the Miranda opinion and left it with only itsskeleton-the four-part warnings and the right to cut off ques-tioning.62

The Miranda court explained at length how police use psy-chological coercion to obtain confessions without using force or

pelled Self-Incrimination, 93 CAL. L. REV. 465, 489-90 (2005). As a result, the tests ofconfession admissibility after Miranda had virtually nothing to do with reliability. Seealso White, supra note 52, at 2021-23 (1998). The rejection of reliability concerns wasmade complete and total in Colorado v. Connelly, 479 U.S. 157, 159 (1986), where theCourt held that a confession that was ordered by the "voice of God" and made by a psy-chotic was nonetheless "voluntary."

58 Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 455 n.24 (1966).59 Leo, The Impact of Miranda Revisited, supra note 19, at 672.60 As Donald Dripps observes, Miranda was preceded by Escobedo v. Illinois, 378

U.S. 478, 492 (1964), in which the Court held that there is a Sixth Amendment right tocounsel whenever the police begin to "focus" on the suspect. This "implied the end of po-lice interrogation." DONALD A. DRIPPS, ABOUT GUILT AND INNOCENCE: THE ORIGINS,DEVELOPMENT, AND FUTURE OF CONSTITUTIONAL CRIMINAL PROCEDURE 75 (2003).Miranda implicitly rejected both the Sixth Amendment's application and the "focus" test,and thereby "saved police interrogation from the jaws of Escobedo." Id. at 76. By substi-tuting the Fifth Amendment for the Sixth, the Miranda court allowed interrogation withits dubious holding that one who is in an "inherently coercive" environment can nonethe-less waive the right to silence.

61 See supra note 18.62 What survives the four-decade erosion of Miranda are the following requirements:

(1) to give the four-part warnings prior to obtaining an admissible confession in a custo-dial setting, (2) to respect the suspect's invocation of silence, and (3) to respect his re-quest for the assistance of counsel. In (2) or (3), all "interrogation must cease." Miranda,384 U.S. at 473-74.

[Vol. 10:551

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 564 2006-2007

2007] Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

threats of force-how they lie to the suspects, create phony accu-satory witnesses, falsely accuse suspects of other crimes, promiseleniency and employ phony expressions of sympathy-and theCourt seemingly disapproved of these methods.63 Yet lowercourts have, with virtual unanimity, condoned them all.64 Oncethe Miranda warnings are given, the old techniques continue.Some new ones have been added, like asking the suspect, whodenies guilt, to imagine or dream about how he might have doneit if he had done it-as in O.J. Simpson's recent unpublishedbook, If I Did It.65 Once the suspect articulates a fanciful sce-nario of guilt, he then is pressured to admit that the fantasy istruth. That sometimes succeeds with innocent suspects. 66

As has been repeatedly demonstrated, there are seriousthreats to the innocent in contemporary interrogation techniquesand their judicial condonation. People confess to crimes thatthey did not commit.67 Some do this for publicity and attention,68others because "God" told them to,69 others to escape the pres-sures of interrogation,70 others because the police persuaded

63 Id. at 449-55.64 See White, supra note 41, at 1217-18.65 See Edward Wyatt, Publisher Calls Book a Confession by O.J. Simpson, N.Y.

TIMES, Nov. 17, 2006, at C1.66 See, e.g., JOAN BARTHEL, A DEATH IN CANAAN 49-140 (Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

1977) (1976) (detailing the interrogation of Peter Reilly about the death of his mother);JOHN GRISHAM, THE INNOCENT MAN 87-93 (2006). A related technique, not noted by theCourt in Miranda, is to suggest to the suspect that he must have "blacked out" or had a"memory problem" that does not allow him to consciously recall what he did. GISLIGUDJONSSON, THE PSYCHOLOGY OF INTERROGATIONS, CONFESSIONS AND TESTIMONY 228(1992).

67 GUDJONSSON, supra note 66, at ch. 10; Richard A. Leo & Richard J. Ofshe, TheConsequences of False Confessions: Deprivations of Liberty and Miscarriages of Justice inthe Age of Psychological Interrogation, 88 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 429 (1998); StevenA. Drizin & Richard A. Leo, The Problem of False Confessions in the Post-DNA World, 82N.C. L. REV. 891 (2004). The basic strategy of modern interrogation is to persuade thesuspect that it is in his interest to confess. The first stage in that process is to convincehim that his conviction is certain regardless of what he says or does. The second is to of-fer him inducements to persuade him that it will be beneficial to him to confess. Id. at914-15.

68 Among the confessions that are internally generated and not in any sense theproduct of interrogation pressures are those motivated by a desire for notoriety. See GUD.JONSSON, supra note 67, at 226. About 200 people confessed to the Lindbergh kidnapping.See Alan W. Scheflin. Book Review, 38 SANTA CLARA L. REV. 1293, 1296 (1998) (reviewingCRIMINAL DETECTION AND THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CRIME (David V. Canter & Laurence J.Alison eds., 1997)). A recent example is John Mark Karr, who confessed to the murder ofJonBenet Ramsey but was released when it was determined that there was no corrobora-tion and he could not even be placed in Colorado when the crime occurred. See JudithGraham, Confession Raises More Questions than Answers: Prosecutor Cautious as DoubtsAre Raised on Suspect's Story, CHI. TRIB., Aug. 18, 2006, at Al, A8.

69 Colorado v. Connelly, 479 U.S. 157, 161 (1986).70 See Innocence Project, Understand the Causes, http://www.innocenceproject.org/

understand/False-Confessions.php (last visited Apr. 2, 2007).

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 565 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review

them that it was in their interest to falsely confess,71 and stillothers because they have been at least temporarily persuaded oftheir guilt by skilled practitioners of coercive persuasion, i.e., po-lice interrogators.72 We have no way to quantify reliably whatpercentage of all confessions given are false, since there is rarelyany DNA or other forensic evidence to refute the confession.However, in several studies of innocents wrongly convicted,stretching over nearly a century, false confessions have been ob-tained in 14-25% of the cases. 73 Among those persons who havebeen convicted and later exonerated by DNA results, about one-fourth had confessed.74

Stripped of its muscle by narrowing interpretations,Miranda not only provides no significant protection for suspects,guilty or innocent, it actually assists the police in their efforts toconvict whomever they believe to be guilty.75 If the Court hadnot imposed the warnings on the police, they would eventuallyhave discovered their value and given them anyway. It is no ab-erration that Miranda is being copied all over the world and thatthe police and prosecutors like it.76 Miranda no longer has any-thing significant to say about the legality of interrogation meth-ods or the reliability of confessions. Yet since Miranda has beena major focus of debates about confessions, it serves mainly todistract lawyers, scholars and judges from considering the realproblem of interrogation, which is how to convict the guilty while

71 Id.72 See id.73 Drizin & Leo, supra note 67, at 902.74 Innocence Project, supra note 70.75 The problem of false confessions is exacerbated by the apparent fact that police,

who typically presume guilt of the suspect until persuaded otherwise, surprisingly, haveno special skill in evaluating credibility. Chet Pager reports the following on that subject:

One widely cited 1991 study assessed the lie detection ability of 509 sub-jects, including officers from the CIA, FBI, National Security Agency, Drug En-forcement Agency, California police, judges, psychiatrists, and college students.Accuracy rates ranged from 53% to 58%, with no expert group performing sig-nificantly better than untrained college students. Previous studies involvingfederal law enforcement officers, police, detectives, and investigators foundsimilar accuracy results, which fell in the mid-fifties. Despite their increasedconfidence, experts are no better than inexperienced civilians at distinguishingtruth from falsehood, and some studies have found that experts, despite (or be-cause of) their years of experience, perform even worse than laypersons.

Chet K.W. Pager, Blind Justice, Colored Truths and the Veil of Ignorance, 41WILLAMETTE L. REV. 373, 380-81 (2005).

76 See All Experts, Miranda Warning: Encyclopedia, http://en.allexperts.com/e/mlmilmirandawarning.htm (last visited Apr. 2, 2007); Richard A. Leo, The Impact of MirandaRevisited, supra note 19, at 666 (1996). In 1988, an American Bar Association surveyfound that an overwhelming majority of police, prosecutors and judges surveyed reportedthat compliance with Miranda did not hinder law enforcement efforts. Leo. supra note21, at 1022.

[Vol. 10:551

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 566 2006-2007

2007] Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

protecting the innocent.7Many scholars have proposed changes in the law to increase

the reliability of confessions and to reduce the pressures of inter-rogation. They include putting time limits on interrogation,T7putting lawyers in the interrogation room,79 and prohibiting someor all police fraud and trickery.8O These proposals have varyingmerit in that some would reduce risks to the innocent while in-terfering minimally with efforts to convict the guilty, while oth-ers, such as putting lawyers in the interrogation room, wouldgravely curtail the utility of police interrogation. An overarchingproblem with all of these proposals is the presumed remedy fortheir violation: suppressing the defendant's statements. Such adrastic remedy chills much of what might otherwise be warmsupport for some of these proposals.

IV. MORE NUANCED REMEDIES ARE NEEDED

We need to face the fact that judges simply are not going tothrow out confessions just because psychological coercion wasused or some rule relating to interrogation was not fully obeyed.81

77 Some might quibble that the "real problem" is not convicting the guilty while pro-tecting the innocent but rather protecting the right of the suspect to be free from coercionthat renders his statement "involuntary." I acknowledge that this is a problem, too, but Ido not think it is of the same magnitude as my version. In any event, the two problemsoverlap considerably. Another bothersome concern, outside the scope of this article, is the"distributive justice" problem described by William Stuntz. Noting that Miranda substi-tutes a right of silence for a system that regulates interrogations, he argues that this sub-stitution rewards sophisticates who understand the interrogation system and does virtu-ally nothing for those who, by reason of limited education, inexperience, and otherdisadvantages, do not know what they are getting into when they agree to be interviewed.Stuntz, supra note 30, at 978.

78 Apart from mentally ill people who confess for irrational reasons, the innocentwho confess usually do so only after lengthy interrogation. Professor White recommendedan upper limit on interrogation of six hours, after earlier suggesting a five-hour limit.Compare White, supra note 52, at 2049, with Welsh S. White. False Confessions and theConstitution: Safeguards against Untrustworthy Confessions. 32 HARv. C.R.-C.L. L. REV.105, 145 (1997). See also infra notes 111-14 and accompanying text, stating that over90% of interrogations last no more than two hours whereas the interrogations that pro-duce false confessions typically last three times that long, or more.

79 Charles J. Ogletree, Are Confessions Really Good for the Soul?: A Proposal toMirandize Miranda, 100 HARV. L. REV. 1826, 1842 (1987); see also Akhil Reed Amar &Ren4e B. Lettow, Fifth Amendment First Principles: The Self-Incrimination Clause, 93MICH. L. REV. 857, 858 (1995) (allowing a judge to compel answers from the defendant).

8o Welsh S. White, Police Trickery in Inducing Confessions. 127 U. PA. L. REV. 581,602 (1979). But see Laurie Magid. Deceptive Police Interrogation Practices: How Far isToo Far? 99 MICH. L. REV. 1168, 1209 (2001) (arguing that "additional limits on deceptionare unwarranted").

81 The same fate can be predicted for proposed "reliability hearings," where, as acondition to admissibility, the trial judge holds a hearing and finds the defendant's state-ment to be reliable. For details of one such innovative proposal, see Sharon L. Davies,The Reality of False Confessions-Lessons of the Central Park Jogger Case, 30 N.Y.U.REV. L. & Soc. CHANGE 209, 241-43 (2006). I support pretrial reliability hearings not be-

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 567 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review

The conventional remedy for "involuntary" confessions, Mirandaviolations, and other illegal interrogation methods is to excludethe confession from evidenceS2 and, in at least some cases, to ex-clude derivative evidence as well.83 An exclusionary ruling keepsprobative evidence from the jury and sometimes threatens to de-stroy the prosecution's case and free a guilty and dangerous de-fendant. That probably does not happen three times a year, de-spite more than a million felony prosecutions.84 Focusing onMiranda compliance and an undemanding "voluntariness" re-quirement assures that virtually all confessions will be admissi-ble in evidence, but does nothing to help the jury determine howmuch weight to give to incriminating statements made by the ac-cused. We need to think about more nuanced remedies that willhelp the jury accurately evaluate the reliability of such state-ments. Three candidates-videorecording, expert testimony andcautionary instructions-are briefly discussed below.

Although it is possible to convict many defendants withouttheir confessions, there is no doubt that confessions are oftennecessary for convictions.85 They are powerfully incriminating:juries almost always convict a defendant who has confessed, evenwhen there is little or no corroborating evidence and even wherethere is evidence of innocence.86 Jurors are not aware of how un-reliable evidence of confessions or incriminating statements canbe.87 First, there is uncertainty about what the defendant actu-ally said to the police and in what context. This is true even if awritten confession is obtained. If the only way to reconstruct theinterrogations and their context is through the memory of thosepresent-the police and the defendant-there is great risk of er-

cause I think they will result in exclusion of unreliable confessions-they will not-butbecause they will provide pretrial discovery that will help the defendant attack the reli-ability of the statement before the jury. If the interrogation is recorded, however, theneed for other evidence related to the interrogation will be minimized.

82 Minnick v. Mississippi, 498 U.S. 146, 156 (1990).83 See Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States. 251 U.S. 385, 391-92 (1920) (hold-

ing that information obtained illegally cannot be used for any purpose). But see Oregon v.Elstad, 470 U.S. 298, 307 (1985), where the Court distinguishes between "prophylactic"violations of Miranda, to which the "fruit of the poisonous tree" prohibition does not ap-ply, and "coercion of a confession," to which the prohibition does apply.

84 See supra note 51.85 Virtually all who write about confessions concede this. Confessions are less im-

portant where there is strong corroboration and much more important where there is lit-tle, and it is in the latter case that the primary risk of false confession exists.

86 Drizin & Leo, supra note 73, at 962; Leo & Ofshe, supra note 67, at 481; Saul M.Kassin & Katherine Neumann, On the Power of Confession Evidence: An Empirical Test ofthe Fundamental Difference Hypothesis, 21 LAW & HUM. BEHAV. 469, 470 (1997); Saul M.Kassin & Holly Sukel, Coerced Confessions and the Jury: An Experimental Test of the"Harmless Error" Rule, 21 LAW & HUM. BEHAV. 27, 42 (1997).

87 Leo & Ofshe, supra note 87, at 962.

[Vol. 10:551

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 568 2006-2007

Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

ror.88 Memories of the details of conversations are shockinglyunreliable-worse by far than eyewitness identification memo-ries.89 Apart from inaccuracies, testimony about interrogations isnecessarily incomplete. The subtle pressures, assurances anddeceits that accompany police interrogation will inevitably be leftout of the story or at least minimized.90 This is exacerbated bythe fact that the defendant is often neither very bright nor veryarticulate, and he rarely has anyone to corroborate his story.

A. Videorecording

Perhaps the least controversial remedy for abuses in the in-terrogation room is compulsory videorecording of the interroga-tion.91 This has been done in England since 1984.92 Alaska re-quires it as a matter of due process and has been videorecordingfor more than two decades.93 Many police departments through-out the country have long been videorecording selectively.94 AnIllinois Commission headed by Thomas P. Sullivan recentlyspoke to 238 law enforcement agencies in thirty-eight states thatcurrently record custodial interviews in at least some felony in-vestigations. The Commission found that "[t]heir experienceshave been uniformly positive."95 Among the advantages to lawenforcement are that the detectives can focus on the suspectrather than taking copious notes while interrogating;96 when thepolice review the recordings later, they often observe incriminat-

88 "Interrogation still takes place in privacy. Privacy results in secrecy and this inturn results in a gap in our knowledge as to what in fact goes on in the interrogationrooms." Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 448 (1966).

89 Steven B. Duke, Ann Seung-Eun Lee & Chet K.W. Pager, A Picture's Worth aThousand Words: Conversational Versus Eyewitness Testimony in Criminal Convictions,44 AM. CRIM. L. REV. 1 (2007).

90 The temptation of the police to "testily" (that is, to lie on the witness stand) tosupport the admissibility or reliability of evidence is also a factor that cannot be ignored.See generally Gabriel J. Chin & Scott C. Wells, The "Blue Wall of Silence" as Evidence ofBias and Motive to Lie: A New Approach to Police Perjury, 59 U. PITT. L. REV. 233, 234(1998).

91 See Yale Kamisar, Foreword: Brewer v. Williams-A Hard look at a DiscomfitingRecord, 66 GEO. L.J. 209, 236-43 (1977); Gail Johnson, False Confessions and Fundamen-tal Fairness: The Need for Electronic Recording of Custodial Interrogations, 6 B.U. PUB.INT. L.J. 719, 735-37 (1997). See also cases and other authorities collected in Common-wealth v. DiGiambattista, 813 N.E.2d 516, 529-31 (Mass. 2004). "Videotaping" is nolonger the appropriate description since videorecording is increasingly done digitally.

92 Johnson, supra note 91, at 745.93 Stephan v. State, 711 P.2d 1156, 1159 (Alaska 1985).94 William A. Geller, Videotaping Interrogations and Confessions (1992), reprinted in

THE MIRANDA DEBATE, supra note 6, at 303, 304-05.96 THOMAS P. SULLIVAN, NORTHWESTERN UNIV. SCH. OF LAW CTR. ON WRONGFUL

CONVICTIONS, POLICE EXPERIENCES WITH RECORDING CUSTODIAL INTERROGATIONS (2004),available at http://www.law.northwestern.edu/depts/clinic/wrongful/documents/SullivanReport.pdf [hereinafter SULLIVAN REPORT].

96 Id. at 10.

2007]

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 569 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review

ing statements that they would have forgotten or not perceived inthe first place,97 recordings "dramatically reduce the number ofdefense motions to suppress statements and confessions,"98 andincrease the number of guilty pleas.99 Judges prefer the re-cordings to having to hear and resolve conflicts in testimonyabout the interrogation and its results.100 It appears that theonly opposition from law enforcement is from those who have nottried videorecording.101

A common objection to a recording requirement for custodialinterrogations is that when suspects are informed or realize thesession is to be recorded, they will refuse to be interviewed or willat least "clam up" and become untalkative. But according to theSullivan Report, these concerns are "unfounded."102 First, moststates do not require that the suspect be informed that he is be-ing recorded.103 Even when the suspects are informed, they usu-ally do not object to being recorded and there is little evidencethat their responses to interrogation are adversely affected byknowledge of the recording. Once the interviews get underway,initial hesitation fades and the suspects focus on the subject ofthe interview.104 In those rare instances when suspects object tothe recording, the interview can proceed without recording, pro-vided the objection is documented.105

Another concern frequently heard is that the police will tryto circumvent the requirement by conducting their interrogationsoff camera and will only use the recording to preserve the resultsof the earlier interrogations, a "recap." If the entire custodial in-terrogation is required to be videorecorded, however, the recapapproach would be unlawful and it is unlikely that the recapcould be passed off as an entire interrogation. Thus, the only ef-fective way to circumvent the recording requirement would be tointerrogate in a non-custodial setting. This might be consideredanalogous to interrogating "outside of Miranda," getting the con-fession, then Mirandizing the suspect and having him repeat

97 Id. at 11. This would seem especially important where the credibility of the con-fession rests on the claim that the suspect provided details of the crime that he could nothave learned anywhere but at the crime scene.

98 Id. at 8.99 Id. at 12.

loo Id. at 13.lo An earlier study found the same thing: law enforcement opposition to taping came

mostly from those who were unfamiliar with the practice. Geller, supra note 94, at 305.102 SULLIVAN REPORT, supra note 95, at 20. Cassell & Hayman, supra note 16, at 897

(finding no inhibiting effects when suspects in their sample were recorded).1O3 SULLIVAN REPORT, supra note 95, at 20.104 Id.105 Id. at 22.

[Vol. 10:551

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 570 2006-2007

2007] Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guiltv?

it.106 Some courts have disapproved of that stratagem 107 andsimilar rulings could be made when recording is involved. Onthe other hand, as the Court in Miranda correctly implied, thedangers of involuntary confessions are relatively remote in non-custodial interrogations. I see no profound objection to allowingthe police to interrogate briefly on the street or in a suspect'shome and to using the fruits thereof either as evidence at trial orto facilitate on-camera interrogations in a custodial setting.

The temptations to evade recording requirements seem notto be a major problem in those jurisdictions that require the re-cording of interrogations. The advantages of recording the actualinterrogation rather than merely its fruits are substantial. Forone thing, it avoids claims of off-camera threats, promises andother improprieties. 108 If a suspect begins the interrogation withevasions and lies, then admits the crime without extensive prod-ding and cajolery, a stronger piece of evidence has been createdthan if merely the results are recorded.109 More than ninety per-cent of normal interrogations last less than two hourslO and itseems unlikely that in most of those interrogations it was neces-sary for the police to employ techniques that were extreme ordespicable.l In a typical interrogation, incriminating state-

106 Another way police go "outside Miranda" is to continue to question the suspectafter he invokes his right to silence or to consult counsel. If an incriminating statementfollows, it can be used to impeach the suspect at trial. See Charles D. Weisselberg, Sav-ing Miranda, 84 CORNELL L. REV. 109, 189-92 (1998).

107 See, e.g., Missouri v. Seibert, 542 U.S. 600 (2004).108 SULLIVAN REPORT, supra note 95, at 17. Even where recording was not manda-

tory, the consensus of law enforcement officers queried by the Sullivan Commission wasthat recording the entire interrogation rather than the final statements was preferable.In addition to avoiding claims of off-camera skullduggery, full recording also defeats a de-fense claim that "negative inferences should be drawn because the entire session couldhave been recorded by the flick of a switch, whereas the detectives chose instead to recordonly a rehearsed final statement." Id. at 17-18.

log A dramatic example of the importance of recording the entire interrogation is theCentral Park Jogger Case, where the police conducted unrecorded interrogations followedby taped final confessions. The defendants in that case were later shown to have beenconvicted falsely. See Crime, False Confessions and Videotape, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 10, 2001,at A22; Saul Kassin, False Confessions and the Jogger Case, N.Y. TIMES, Nov. 1, 2002, atA31.

11o Leo, Inside the Interrogation Room, supra note 19, at 279 (noting that of 182 po-lice interrogations observed in the early 1990s, more than 70% lasted less than an hour;92% less than two hours); Barrett, Jr., supra note 28, at 42 (noting that nearly half of allpre-Miranda interrogations were completed in 30 minutes or less, nearly three-quartersin an hour or less, 95% in less than two hours).

iii In a study of 182 actual interrogations in a major urban police department, con-ducted by forty-five different detectives, Richard A. Leo observed and catalogued the tac-tics employed. Most involved some negative incentives (suggestions that there is no otherplausible course of action) and positive incentives (suggestions that the suspect will feelbetter or otherwise benefit if he confesses). In 90% of the interrogations, the detectivesconfronted the suspect with incriminating evidence, usually true (85%) but sometimesfalse (30%). The longest interrogation lasted four-and-a-half hours. Leo, Inside the Inter.

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 571 2006-2007

Chapman Law Review

ments are obtained without extreme conduct that would seri-ously embarrass the police or that would create grave doubtabout the voluntariness or reliability of the statements."12 There-fore, to interrogate and then recap and record is, in most cases, aduplication of effort. The kind of interrogation that is likely toproduce a false confession-a lengthy interrogation113 suffusedwith trickery, cajolery, good guys and bad guys, fake evidenceand so forth-is surely uncommon in most police departmentsand the police will rarely, if ever, expect to engage in such an in-terrogation at the outset. Accordingly, when they would wish tointerrogate off camera, it is usually too late: the interrogation hasalready occurred on camera.

Videorecording will not always help the defendant. Experi-ence strongly suggests that more often it will help the prosecu-tion convict him. But in those exceptional cases where intensepsychological pressure has been employed or there is little cor-roborating evidence, there is no substitute for a videorecording ofthe entire interrogation. Courts should not wait for legislaturesto require such recording. They should encourage it either byholding that it is required by due process, as the Alaska Courtdid,114 or in the exercise of their supervisory power, as the Min-nesota Supreme Court did,115 or as in Massachusetts, by instruct-ing juries that "because of the absence of any recording of the in-terrogation in the case before them, they should weigh evidenceof the defendant's alleged statement with great caution andcare."116

rogation Room, supra note 19, at 278-79. Some police fear that these common tactics,especially minimizing the moral seriousness of the offense, will have to be curtailed ifthey record. This concern does not loom large in the Sullivan Report. SULLIVAN REPORT,supra note 95, at 22.

112 Of the 182 interrogations observed by Richard A. Leo in the early 1990s, only fourof them involved what Leo regarded as "coercive" methods. Leo, Inside the InterrogationRoom, supra note 19, at 282-83.

113 In a study of 125 "proven false confessions," Steven Drizin and Richard Leo foundthat in the 44 confessions in which the length of interrogation was determinable, 84%lasted more than six hours, "34% between six and twelve hours; 39% between twelve andtwenty-four hours; 7% between twenty-four and forty-eight hours; 2% between forty-eightand seventy-two hours; and 2% between seventy-two and ninety-six hours. The averagelength of interrogation was 16.3 hours and the median length of interrogation was twelvehours." Drizin & Leo, supra note 67, at 948-49.

114 Stephan v. State, 711 P.2d 1156, 1162 (Alaska 1985). It would not be a majorstretch to find a due process violation in the failure to record an interrogation. The Su-preme Court has intimated that it would be a due process violation to destroy or fail topreserve evidence if the police did so in order to gain an advantage over the defendant.See Arizona v. Youngblood, 488 U.S. 51, 58 (1988).

115 State v. Scales, 518 N.W. 2d 587, 589 (Minn. 1994).116 Commonwealth v. DiGiambattista, 813 N.E.2d 516, 533-34 (Mass. 2004). A Ca-

nadian court recently held that a failure to record an interrogation warrants a jury in-struction that the failure constitutes "an important factor to consider in deciding whether

[Vol. 10:551

HeinOnline -- 10 Chap. L. Rev. 572 2006-2007

Does Miranda Protect the Innocent or the Guilty?

B. Expert Witnesses

Given the ignorance of juries about the innocents' propensityto confess falsely and the evidence that such confessions aremuch more common than was supposed prior to the DNA revolu-tion, one might expect courts routinely to admit the testimony ofpsychologists in cases where there is a plausible claim that theconfession was coerced, or in any event unreliable because of themethods and circumstances under which it was obtained. Suchan expectation would be premature.

The strongest case for admissibility of expert confession tes-timony would appear to be the psychiatrist or psychologist whotreated the confessor before he was interrogated or at least con-ducted extensive psychological testing and examinations thereaf-ter. Such an expert could testify to the psychological traits of thedefendant that would incline him toward giving a false confes-sion. Is he pathologically gullible or deferential? Does he have aperverse need to please his interrogators, such that he might con-fess to a crime just to please them? How intelligent is he? Suchtestimony would certainly provide the jurors with evidence thatwould not otherwise be known to them and that any rational per-son would consider relevant in assessing the reliability of theconfession. The Supreme Court declared such evidence immate-rial, however, on the issue of voluntariness. In Colorado v. Con-nelly, the Court held that coercive police activity alone deter-mines involuntariness.117 Unless the police were aware of somespecial vulnerability of the suspect and exploited it, the Courtstated, his vulnerabilities have nothing to do with whether hisconfession is voluntary or involuntary. In Connelly, the defen-dant approached a police officer and confessed to a murder.Later, at the police station, he confessed to a child's murder. Thefollowing day, he told the police he had confessed because voiceshad told him to do so. A psychiatrist who examined him testifiedthat he was psychotic and was following instructions from the"voice of God." Accordingly, the psychiatrist testified, these