Disruptive Reforms: China's Risks and Opportunitiesdesigned to reform and open up the economy....

Transcript of Disruptive Reforms: China's Risks and Opportunitiesdesigned to reform and open up the economy....

APRIL 2016

Disruptive Reforms: China's Risks and Opportunities

Stuart RaeChief Investment Officer

International Strategic Equities

Anthony ChanAsian Sovereign StrategistGlobal Economic Research

2

China has had a track record since the 1970s of successfully implementing policy objectives designed to reform and open up the economy. Indeed, the challenges facing China today remind many of the late 1970s. Back then, disruptive changes under Chairman Deng Xiaoping steered China from poor to middle-income, succeeding beyond expectations. Today, China needs further disruptive change to transition from middle- to high-income...and the outcome is not yet clear.

The key policy challenge facing China right now is that of reducing excessive systemic debt while avoiding a hard economic landing and preserving social harmony, and at the same time pushing through much-needed financial and economic reforms in the face of institutional inertia and the recalcitrance of vested interests. To effect such a change in any economy at any period in history would be difficult; to attempt it in the world’s second largest economy based on GDP1 at a time of geopolitical uncertainty and global economic weakness seems impossibly Herculean.

But then, in 1978, very few pundits thought China could succeed in lifting 500 million people out of poverty in one generation.

In the pages that follow, we attempt to provide a broader perspective on the current China debate. The front half of our paper explores long-term possibilities, followed by a discussion of some important, potential risks.

In making our case, we present a number of ways in which China’s reform path could disrupt the global investment landscape and create a sense of “future shock” for investors—particularly those who have maintained a bearish view of China’s prospects and have not hedged against the possibility of positive upside surprise (see “Brace Yourself: Six Disruptive Changes We Expect from China’s Reforms,” page 4).

A word of caution, however: we need to see significant progress on these disruptive changes in the next two or three years for us to be confident that China is indeed on track to complete its reform process, which, by any reasonable estimate, will take a decade or more. Given the pace of China’s reforms to date—which has outrun many people’s expectations and even surprised us on occasion—we believe that the country has a better-than-even chance of turning its aspirations into reality.

HERCULEAN GOALS: BIG RISKS, BIG REWARDS

1 International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2015

Disruptive Reforms: China’s Risks and Opportunities 3

CHINA’S POLITICAL WILL TO SUCCEEDLooking at China’s policy track record to date, we assign a high probability to our disruptive forecasts becoming a reality.

Our views have a historical basis in the country’s 12th Five-Year Plan—launched in 2011—and the 13th Five-Year Plan, released this year. As most investors know, the strategic objective of the recent plans is to rebalance China’s economy so that consumer demand will drive growth alongside the traditional dynamics of exports and investment.

This far-reaching structural change would be a huge challenge at the best of times, given the many social, economic and financial reforms required to implement it, including broad deleveraging across the economy and the introduction of market-based pricing mechanisms.

Unfortunately for Chinese policymakers, they face a global environment of weak growth and volatile financial markets. Consequently, they need to tread a fine line between two competing policy objectives: implementing reforms while keeping domestic growth high enough to underpin employment and avoid inflaming social tensions (a key political consideration for a one-party state).

From this has arisen much of the bearish sentiment that, at the time of this writing, continues to color most investors’ views. Many, for example, are nostalgic for the high growth rates of the first great wave of industrial expansion from the 1990s to the early 2000s, when China became the “factory to the world.” Others long for a decisive policy response, such as the massive fiscal stimulus of the global financial crisis. This kept the world’s economic pulse beating by ensuring that China remained an important marginal consumer of commodities.

More realistic investors are simply skeptical of China’s ability to manage its policy dilemma.

We agree that the old days of high nominal GDP growth are never coming back, but we don’t share the more pessimistic views regarding policy management—for two reasons.

First, China’s one-party political structure, backed by a network of elites with strong connections to both politics and business, is highly conducive to the successful implementation of national government policy. Compared to many other countries, China is very well placed to ensure that all available resources, from the political apparatus to privately owned companies, can work together quickly to achieve policy objectives.

Second, China has a long history of economic reform. The process fully began with the Fifth Five-Year Plan (1976–1980) under Chairman Deng Xiaoping, which steered China toward becoming a socialist market economy. The Ninth Five-Year Plan (1996–2000) under President Li Peng ushered in reforms to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the recognition of the role of the private sector in an increasingly market-oriented economy. We see the 12th and 13th Five-Year Plans as being direct descendants from these initiatives.

Indeed, many compare current President Xi Jinping to Deng Xiaoping for both his drive for economic reform and his success in making his authority within the Communist Party virtually unassailable. While the regime before Xi’s made the important reform of centralizing government, Xi has taken a crucial further step by consolidating his power.

All these factors line up, in our view, to increase the likelihood that China will succeed in its objectives.

Two factors will be decisive in determining success: the will and ability of the Chinese government to drive the

necessary changes.

4

BRACE YOURSELFSix Disruptive Changes We Expect from China’s Reforms

Below, we summarize the key ways we expect China will fundamentally reshape the global investment landscape within the next two to three years.

1. RMB VS. USD

Usage of China’s currency, the renminbi (RMB), will expand to account for nearly 50% of the country’s global trade settlements.

The RMB will become almost as important as the US dollar (USD) as a global trade settlement currency, and on par with the Swiss franc as an international reserve currency for Asian banks.

At the same time, the deglobalization of the world economy will continue, with three regions taking center stage—the Americas, Europe and Asia. Each will have its own currency bloc: the US dollar, euro and RMB.

This growing regionalization, and the increasing importance of the RMB, will dilute the dollar’s ability to transmit US monetary policy effects. Consequently, policy changes by the US Federal Reserve will have a less extensive direct impact on the world economy than in the past.

Evidence that such a decoupling is already under way can be seen from the fact that, when the Fed reduced interest rates to near zero in response to the global financial crisis, a number of Asian central banks raised rates. Since then, Asian central banks have variously raised and lowered rates. In the first half of 2015, as the Fed prepared to begin normalizing rates, some Asian central banks actually lowered theirs.

2. CHINA’S SLOWER-GROWTH ECONOMY WILL WIN INVESTOR SUPPORT

China’s economic growth will be running at “only” 5%–6% a year, well below the double-digit pace that prevailed during the country’s heyday as the world’s exporter. This will be considered normal by policymakers and by domestic and foreign investors.

The reason: a change in the dynamics driving the Chinese economy. While a fair proportion of GDP growth will come from recovering export demand (particularly in the US), domestic consumer demand will play a much bigger role than it did in the past.

Until recently, China’s policymakers saw strong headline growth as the key to maintaining high employment and social harmony. The increased share of consumption in the economy will lead to better quality and more sustainable growth, and this will favor economic and social stability.

A more diverse economy will mean more opportunities for investors, and 5% or 6% will still be an attractive growth rate relative to the rest of the world.

This will make China attractive to foreign capital, particularly as the country and Asia in general will come to be regarded as investment destinations in their own right, rather than as subsets of emerging markets—a change in attitude that in itself will add to the markets’ momentum.

3. BENCHMARK CHANGES WILL FORCE THE “BIG SWITCH”

The disruption likely to be the most personally felt by investors will be the need to adjust their portfolios when China is included in global market indices. We regard this as almost certain to take place within two to three years.

China’s government bond market is already the third largest in the world. This implies that fixed-income investors who follow cap-weighted benchmarks will need to reallocate about 30% of their sovereign bond portfolios to China when it enters the global bond indices.

The full inclusion of China A shares in global equity indices would increase China’s weight in an emerging-market universe from around 25% today to over 40%.

Bond and equity markets are likely to feel the effects as investors buy and sell to align their portfolios to the restructured indices.

Disruptive Reforms: China’s Risks and Opportunities 5

The investors who will benefit the most from this change will be those who research the China opportunity and position their portfolios appropriately before the “Big Switch” takes place.

4. CHINA’S CAPITAL MARKETS WILL MATURE

Investors who are early to the China opportunity will do well from sector plays—particularly those leveraged to the growth in consumption, such as consumer cyclicals and staples, healthcare and financial services.

After the initial rush to invest, we expect the rate of growth in China’s financial markets to slow. The key to finding good investment opportunities will lie less in sector plays and more in finely honed stock selection.

The markets will also become less volatile. Historically, volatility in China’s markets has been driven by the short-term outlook of retail investors, but China’s reform program will mean that more money coming into the market will be long term.

That will be partly a result of the growth of pension funds and insurers—another consequence of the rising consumer class—which will issue and invest in the market on a long-term basis, to match their liabilities.

It will also be partly a result of the growth in listed infrastructure funds, brought about by reforms in the SOE sector.

These dynamics will not be as exciting as those of the old “casino style” Chinese market, but they will be attractive, and foreign investors will increasingly look to China as a core component of their diversified portfolios.

This will provide positive, long-term structural support for the market’s growth.

5. CHINA IS LIKELY TO INNOVATE AND SET GLOBAL TRENDS

“Made in China” will cease to be a turnoff for fussy Western consumers. Instead of being associated with cheap and not-particularly-well-made goods, the phrase will acquire a new cachet as Chinese manufacturers and consumers set trends that Western consumers—particularly the young—will want to follow.

The seeds of these trends have already been sown: in early 2015, Chinese company Estar Technology Group won the CES Innovation Award for its Takee 1 holographic smartphone, which allows users to touch and interact with its holographic screen.

Another example is the emergence of a class of young, affluent and educated Chinese consumers—the so-called millennials—which has sparked a new wave of investment opportunities as their tastes dictate trends in fashion and luxury goods, both in China and elsewhere.

6. IT WILL HOLD NEARLY HALF THE WORLD’S PURSE STRINGS

Whereas Western countries currently exert global influence—particularly in developing nations—through The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and other institutions, China will compete through institutions of its own, such as the recently launched Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

This will lead to geopolitical realignments—particularly in Eurasia and some parts of eastern Europe, where China plans significant project-related investment; for foreign investors, it will also create new investment opportunities outside China, but within the country’s sphere of influence.

6

CHINESE CURRENCY GOES GLOBALEach of our disruptive forecasts is based on our view of how current real-world events in China are likely to play out for the country, its citizens and global investors.

While it’s necessary to discuss each reform individually, it’s important to remember that they are all interlinked: their impact, in other words, will be cumulative and mutually reinforcing—and therefore likely to be all the more powerful.

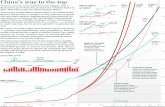

Let’s begin with the internationalization of the RMB. Today, about 25% of China’s trade is settled in RMB. As Display 1 shows, however, it’s not this absolute share that’s interesting as

much as the progress the currency has made since 2010, when the Chinese government reached an agreement with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority to make the RMB deliverable into the Special Administrative Region, thus beginning the currency’s internationalization. To distinguish between foreign exchange trades conducted inside and outside China, the offshore and onshore currencies were designated CNH and CNY, respectively (the underlying currency is the same, however).

Just two years later, in mid-2012, the RMB had become the settlement currency for 10% of China’s global trade; over the next 18 months, the proportion doubled, to 20%. The currency already accounts for 9% of the global letter-of-credit market, ahead of the euro and yen and behind only the US dollar.

Admittedly, this fast rate of growth partly reflects that the currency is coming off a low base; we still see it reaching 50% of China’s trade settlement, however, even if the process takes a few years instead of another 18 months. We do so not just because of how we see world trade dynamics evolving over the medium term, but also—as discussed earlier—because of our belief that Chinese policymakers are committed to the process.

DISPLAY 1: CHINA’S RMB TRADE SETTLEMENT SOARSGrowth in China’s Global Trade Settled in RMB

Total RMB Trade Settlement (Left Scale) Share of Total Settlement

PercentTr

ade

Sett

lem

ent

(RM

B Bi

llion

s)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

4Q:09 4Q:10 4Q:11 4Q:12 4Q:13 4Q:14 4Q:15

Through December 31, 2015Source: People’s Bank of China

We see the RMB becoming the settlement currency

for 50% of China’s global trade.

Disruptive Reforms: China’s Risks and Opportunities 7

Evidence of this can be seen in the way that China’s state-owned banks are providing liquidity for RMB settlement in global financial centers in Asia, Europe, the UK and Australia (Display 2). Thanks in no small part to their efforts, the RMB has become the fifth biggest payment currency in value terms (Display 3). According to a March 2015 survey of banks by Central Banking Journal and HSBC, the RMB’s share of global reserves could more than triple, to around 10%, by 2025.

In the run-up to this milestone, China has abandoned the currency’s trading band with the US dollar, using a basket of currencies as a more flexible guide to rate-setting instead. We also expect a few other things to happen: the CNH and CNY designations will disappear, with the currency becoming known offshore and onshore as RMB; and the country’s capital

account will be sufficiently liberalized so that the RMB is highly, if not fully, convertible globally. A significant step forward in RMB internationalization was the International Monetary Fund’s decision last year to include the RMB in their special drawing rights (SDR) basket, alongside the US dollar, Japanese yen, British pound and euro.

DISPLAY 2: TOP 10 OFFSHORE RMB CENTERS IN THE WORLDPayment Value Sent and Received, Excluding China and Hong Kong

2.2

3.8

1.0

3.4

3.4

8.1

10.3

8.5

30.9

16.5%

2.1

2.3

2.4

2.5

4.8

5.4

9.3

10.8

22.5

28.4%

Malaysia#9 —> #10

Luxembourg#6 —> #9

South Korea#15 —> #8

Germany#8 —> #7

Australia#7 —> #6

France#5 —> #5

Taiwan#3 —> #4

US#4 —> #3

UK#1 —> #2

Singapore#2 —> #1

June 2014 June 2013

As of July 31, 2014 (latest available data)Source: SWIFT

DISPLAY 3: RMB CLIMBS IN WORLD PAYMENT CURRENCY RANKINGS (PERCENT)

#1. USD

#2. EUR

#3. GBP

#4. JPY

#5. CNY

#6. CAD

#7. CHF

#8. AUD

#9. HKD

#10. THB

#11. SGD

#12. SEK

#13. NOK

#14. DKK

#15. PLN

#16. ZAR

#17. NZD

#18. TRY

#19. MXN

#20. RUB

0.80

43.41

28.758.24

2.792.061.911.911.74

1.280.980.88

0.680.560.550.430.420.360.350.21

January 2015

As of January 31, 2015Customer-initiated and institutional payments; inbound + outbound traffic; based on valueSource: SWIFT

The RMB has become the fifth biggest payment currency

in value terms.

8

CONSUMERS COMMAND CENTER STAGEEconomic rebalancing is the ultimate goal of China’s economic reforms. Our sense of policymakers’ commitment to this strategy is based on our understanding of the imperative behind it: the need for China to avoid falling into the middle-income trap. This occurs when a developing economy loses its competitive advantage in export markets as wages rise (in 2013, the Asian Development Bank noted that average real wages for urban workers in China had tripled in less than a decade) and is unable to compete with developed economies in the export of higher value-added products.

The key to this monumental change lies in reorganizing the economy, the financial system and the capital markets so that capital can be allocated much more efficiently. This is, of course, no easy task. It involves greater use of private capital, sourced domestically and from overseas. As the government has recognized, there are three prerequisites necessary for this to happen: more effective application of the rule of law at all levels of government and in business; the introduction of market pricing into the financial system; and a restructuring of the SOE sector to encourage more private capital into wealth creation.

President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive targets the first prerequisite. While one might be skeptical about the prospects of the campaign’s success, given the apparently entrenched position of “gift giving” in Chinese culture, the campaign is widely regarded as having exacerbated the slowdown in China’s economic growth—an admittedly negative measure of its effectiveness (Display 4). The decline in gift giving (restaurant meals, wine, watches, etc.) hit the retail sector, and capital spending fell as management at SOEs became more cautious in their approach to investment.

Despite its monetary policy challenges, China continues to nudge its financial sector toward a more market-based pricing regime. In November 2014, for example, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) cut rates unexpectedly. At the same time, it allowed banks to price their deposits at 1.2 times the benchmark rate, compared to 1.1 times previously. This meant that, despite the lower absolute rate, the banks’ competition for deposits increased, creating a powerful incentive for smaller banks to attract deposits and helping to pave the way for a more dynamic market for retail savers and investors.

In other finance-sector changes, the government has tightened regulation over the shadow-banking sector and stopped provincial and municipal governments from sourcing funds through local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). Governments now have to raise funds in the public markets and seek Beijing’s approval before doing so, further consolidating and centralizing President Xi’s power base.

The scope to improve capital allocation and profitability in the SOE sector can be seen from the gap in the return on equity

DISPLAY 4: ANTI-CORRUPTION DRIVE HAS INTENSIFIED SLOWDOWN

Year

-ove

r-Ye

arPe

rcen

t Ch

ange

Industrial Production

Fixed Asset Investment

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Retail Sales Volume

Through February 2016Source: CEIC Data and AB

China is promoting consumer demand to drive GDP growth,

spur new industries and reinvigorate old ones.

Disruptive Reforms: China’s Risks and Opportunities 9

between Chinese state-controlled and non-state firms (Display 5). Some of this divergence is explained by differences in the mix of industries between the private and public sectors; nevertheless, the potential to improve is clear.

The scale and difficulty of this undertaking shouldn’t be downplayed. We fully expect to see problems along the way—such as, for example, corporate defaults and even collapses. As stated elsewhere, however, we are reasonably confident that China will succeed. Following is the sequence of events that we see as logically flowing from the reforms, assuming they are successful, to the changes that they are intended to achieve.

As a result of the corruption crackdown, China’s government and businesses, while still not perfect, will manage their finances with more discipline and integrity, and the overall standard of governance will improve. This will give investors comfort and contribute to capital being priced more efficiently. In SOEs and

privately owned businesses, higher governance standards and the competition for private capital will force management to become more market oriented. Productivity will continue to rise, helped by new technologies, and more export companies will move up the value chain.

The PBOC will create a more sophisticated monetary policy regime targeting a short-term rate within an interest-rate corridor system—that is, the policy rate will be changed inside a prescribed upper and lower level of interest rates. The freedom to change not only the policy rate but also the upper and lower bounds as circumstances dictate will give the PBOC much greater monetary policy flexibility.

A more market-oriented financial system will encourage product innovation, especially in the retail market, and growth in consumer and small business finance. Bank deposit insurance will position smaller banks as a safe alternative to the dominant five major banks, leading to a more even spread of risk. Domestic bond issues will also be priced off the policy rate, enhancing transparency. This, together with a surge in issuance by governments no longer able to self-fund through LGFVs, will contribute to the rapid expansion of China’s domestic debt markets.

Restructuring in the SOE sector will result in increased private participation in key industries such as telecommunications, energy and infrastructure, and these areas will grow. Profits will rise and new private companies will be formed and eventually listed on the country’s burgeoning stock exchanges. More disciplined and targeted investment in infrastructure will help to absorb the excess capacity created by governments when they had access to LGFVs for financing.

DISPLAY 5: CHINA’S PUBLIC-PRIVATE PERFORMANCE GAPReturn on Equity of Chinese Industrial Firms

Perc

ent

SOEs*

Non-SOEs

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

1998 2002 2006 2010 2014

Through December 31, 2014 *SOE = state-owned enterpriseSource: National Bureau of Statistics

Much remains to be gained from making the SOE sector

more efficient.

10

The consumer, meanwhile, will assume an increasingly important role as profit growth leads to higher wages and expansion in the services sector propels insurance, healthcare and pension schemes. For the first time in history, ordinary Chinese people will no longer need to worry so much about the costs of healthcare and old age. Their saving rates—long among the world’s highest—will begin to fall as they help to bring about a more stable and diversified economy.

CHINA’S CAPITAL MARKETS: FOREIGNERS WELCOMEOf all China’s reforms, the one most likely to reverberate around the world is the liberalization of the country’s capital markets. In just a few years, we expect this to lead to China’s bond and equity markets being incorporated into global indices, forcing a massive and disruptive reweighting of portfolios.

China began liberalizing its capital markets in 2002, when it launched the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) scheme, which allowed foreign investors to trade RMB-denominated Class A shares on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets. Since then, the scheme has been steadily expanded, and foreigners have also gained access to the interbank bond market. A further significant step was taken in early 2016 when China relaxed the rules governing the allocation of quotas—moving to a base quota driven simply by the size of the firm.

In 2011 the government established the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII) program to allow non-Chinese financial institutions to launch RMB-denominated funds for investment in mainland China. Like QFII, the RQFII program has grown steadily. China is also encouraging capital flows in the opposite direction, through the Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor (QDII) scheme, which allows authorized domestic firms to invest in offshore securities (Display 6).

In 2014, capital market liberalization accelerated with the launch of Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect (SHKSC), a system that enables share trading between the Hong Kong and Shanghai stock exchanges. The government is working on plans

for a similar program linking the Hong Kong and Shenzhen stock exchanges, which is likely to launch sometime in 2016.

Before SHKSC’s launch, index provider MSCI invited market participants to comment on whether China should be included in its global indices. The answer was negative, as there was not yet sufficient liquidity. The next time MSCI reviews its indices in mid-2016, however, the SHKSC will be another positive factor to consider.

Prior to its launch, offshore investors’ access to domestic Chinese equities was limited to about 80 A shares that were dual-listed on the Hong Kong equity market. As a result of SHKSC, foreign investors now have direct access to around 500 of the A shares—a roughly sixfold increase.

DISPLAY 6: FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC INVESTOR SCHEMES GROWApproved China Investment Funds

USD

Bill

ions

QFIIRQFII

QDII

0

20

40

60

80

100

04 08 12 16

Through March 22, 2016Source: State Administration of Foreign Exchange

Disruptive Reforms: China’s Risks and Opportunities 11

This has created a dramatic change in the Chinese investment opportunity for global investors (Display 7). The bars show the difference between sector weights in the full China A share universe (represented by MSCI China A) and the more restricted set of Chinese stocks listed in Hong Kong (represented by MSCI China). This shows clearly how SHKSC is opening up a range of smaller-cap domestic sectors such as industrials and consumer, and correcting what was a large bias to sectors such as financials, telecoms and technology.

BENCHMARK INCLUSION IS KEY When China is included in global indices (equities and bonds), the impact on the country allocations of investors who track these indices will be significant. In tandem with these developments, we expect China’s equity markets to become less fragmented, with the sometimes confusing array of share subcategories becoming obsolete.

Similar developments will take place with regard to bonds. For instance, in early 2016, China enhanced bond market access by allowing foreign investors to tap into its interbank bond market without having to use QFII or RQFII channels. China’s government bond market is the third biggest in the world, suggesting that its inclusion in the global indices will force index-hugging investors to adjust their portfolios so that China accounts for around 30% of their sovereign exposures.

The potential for these developments can be seen from the fact that China’s equities and fixed income markets were worth about RMB44.5 trillion (US$7 trillion) at January 31, 2015. The amount of foreign capital permitted to be invested in China at that date was RMB715 billion, less than 2% of domestic market capitalization.

We expect over time that the RMB sovereign bond market will become as important as the US-dollar and Eurobond markets, encouraging more foreign corporates to issue in RMB. Eventually the RMB credit market’s liquidity and pricing will rival those of its US counterpart. By that time, investors all over the world will have at least some RMB exposure in their portfolios.

DISPLAY 7: DIFFERENCE IN SECTOR WEIGHTS BETWEEN MSCI CHINA A AND MSCI CHINA

(12.2)

(8.7)

(7.0)

(4.4)

(0.1)

1.6

5.0

5.8

8.2

11.8%

Technology

Telecoms

Financials

Energy

Utilities

Consumer Staples

Healthcare

Consumer Discretionary

Materials

Industrials

Larger in HK Listed Larger in A Shares

As of December 31, 2015Sectors based on the Global Industry Classification StandardSource: MSCI

When China is included in global indices, the impact on investors’ country allocations will be huge.

12

SOFT POWER TO THE PEOPLEChina may become a worldwide cultural influence, in our view, particularly as its creative industries—industrial design, advertising and marketing—develop the necessary “soft skills” to market overseas. Young Western consumers would be an obvious target market for “Chinese style.”

Such popular trends would be an aspect of China’s growing soft power—the ability to influence people or public opinion through constructive engagement. There is another side to China’s soft power, one that is already mapping out a realignment of the world’s most important economic and financial institutions.

China’s emergence as a world banker is taking place on a number of fronts. The internationalization of the RMB and the country’s huge foreign-exchange reserves make it likely, in our view, that the PBOC will rival the Fed as the lender of last resort in Asia. China is also setting itself up in competition with global lending institutions such as The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund by sponsoring projects in developing countries.

In the second half of 2014 alone, China signed agreements that will lead to the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and it joined calls for a “collective strategic study” toward the creation of a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific.

Even these major developments are, for China, part of a bigger picture. The scope of its vision is suggested by plans for a “New Silk Road” from central China through central Asia and eastern Europe to northern and southern Europe. For Chinese manufacturers, the ability to send their goods by rail along this route could cut to just 14 days the 60 days it currently takes to export to Europe by sea. The development of infrastructure along the route would be a boost for many struggling economies and would enhance China’s power and prestige throughout Eurasia.

REGIONALIZING THE PRODUCTION CHAINChina’s challenge to the global financial order, as represented by the NDB and AIIB, is symbolic not only of the country’s increasing power and assertiveness, but also, in our view, of a broader pattern of change. The US-dominated global hegemony of the last 30 years or so is, we believe, giving way to what might be called a process of “de-globalization” in which the world’s production chain will devolve into three main regions: Asia, Europe and the US/Latin America.

In China’s case, evidence for this can be seen in the way its share of imports in semifinished goods for domestic production has declined since 2004 (Display 8), as more international companies have relocated their facilities to the mainland to be close to the world’s biggest consumer market. From the regional perspective, there has been an increase since 2000 in the use of intraregional imports in semifinished goods (Display 9).

This implies that the trend toward divergence and desynchronization in global growth patterns that has become evident over the past few years will intensify. We believe it will also galvanize the dynamics that will eventually lead to China shaking off its status as an emerging market and to its being seen by investors as worthy of portfolio allocations in its own right.

China’s growing soft power is expanding its

sphere of influence.

Disruptive Reforms: China’s Risks and Opportunities 13

STAYING THE COURSEAll this, of course, is subject to the caveat that China needs to navigate a challenging path to avoid a hard economic landing, stay the course with its reform program and maintain social stability. Yet, progress in China’s reforms is often a case of “two steps forward and one step back.”

For instance, there’s no shortage of negative headlines about China’s current economic woes. The latest bearish view warns of China’s imminent demise due to a huge debt buildup and the

inability to simultaneously achieve a stable currency, stimulative monetary policy and a halt to capital flight.

Overall, we consider this perfect storm a tail risk, rather than a base case. While the country’s economy clearly faces another few years of uncertainty, we think the risks will be contained as long as the government sticks to its reform agenda. What follows is our perspective on the near-term “bear case” for China, and why we don’t believe it will transpire.

DISPLAY 8: CHINA IS CONSOLIDATING ITS PRODUCTION CHAIN INTERNALLYImports’ Share of Semifinished Goods for Domestic Production

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

95 97 99 01 03 05 07 09 11

Perc

ent

Shar

e

Germany

S. Korea

Japan

ChinaUS

Through January 1, 2011 (latest available data)Source: World Input-Output Database and AB

DISPLAY 9: PRODUCTION CHAIN HAS BECOME MORE REGIONALIZED2012 Share of “Semifinished Goods” Imports from Same Region

25.4%

55.9%

53.9%

US/Latin America

Europe

Asia +10.9%

+4.1%

+2.4%

Change(2000–2012)

As of December 31, 2012 (latest available data)Source: United Nations and AB

14

SHORT-TERM PRIORITIES COMPETE WITH PROGRESS Since July of 2015, after the Chinese equity market crashed, Beijing has resorted to heavy-handed directives to support local equities and the stability of the RMB. Besides exacerbating global anxieties and risk aversion, these moves have also called into question China’s genuine desire for capital market liberalization.

However, we don’t conflate these tactical policy missteps with Beijing abandoning its strategic reform agenda. Instead, the fear of social discontent has been a key driver, in our view. The poten-tial impact of a stock-market crash on the already weak domestic consumption and investment in today’s slow-growth era like-ly crossed policymakers’ minds. Seen in this light—and against the broader liberalization moves already discussed—we believe short-term priorities have temporarily sidetracked, rather than permanently derailed, the long-term objective.

LOAN SPIKE IS A LEGITIMATE WORRYChina pessimists also express concern over the massive jump in Chinese lending. The buildup has startled investors who are already rattled, intensifying fears that the country’s financial system could be close to collapse. While these concerns are un-derstandable, we think they may be overdone.

While China’s total debt level is high, it is not outrageous com-pared to many other countries. Relative to GDP, the level in the US and many other developed nations is actually higher (Dis-play 10). But the rate of increase does represent a more serious concern—rapid debt growth has often been followed by crises

in other countries in the past. However, there are some impor- tant elements of the Chinese situation that should be noted. It is essentially a closed system, with most of China’s debt issued by state-owned banks to state-owned or controlled entities—making it highly unlikely that the government would foreclose on itself. Also, consumer leverage, which was a key problem in 2008’s financial crisis, is relatively low in China today.

That said, China is taking measures to bring debt growth rates under more control: Lending standards have become tighter, unprofitable SOEs are being reformed or shut down (though this is happening more slowly than many had hoped), the shad-ow-banking system is undergoing scrutiny, and a massive bond-swap program for local governments is being launched to re-duce their cost of servicing debt. Generally speaking, while debt is an issue, the central government is making strides, and we don’t foresee a near-term implosion.

DISPLAY 10: ON MEASURES OF INDEBTEDNESS, CHINA IS IN GOOD COMPANYDebt-to-GDP Ratio of Select Countries

Japan

Ireland

Greece

France

US

China

UK

Australia

South Korea

Germany

Country Debt-to-GDP Ratio

413%

358

326

278

255

248

245

242

231

179

As of October 2015Debt-to-GDP ratio ref lects both fiscal debt and nonfinancial private sector credit. Source: Bank for International Settlements, International Monetary Fund and AB

Worries over China’s debt are understandable, but may be based on an overly simplistic

assessment of the risks.

Disruptive Reforms: China’s Risks and Opportunities 15

WALKING A FINE FX LINEInstability in China’s currency represents another worry for China bears. The ongoing liberalization of China’s currency and capital account could be under threat if the RMB falls, capital outflows intensify and foreign reserves dwindle. We believe that Beijing will continue to walk a fine line, keeping the RMB broadly stable against a basket of key currencies, which may imply some further weakness against the US dollar if the dollar strengthens.

China is facing a well-known conundrum of juggling three con-flicting goals: reducing interest rates to stimulate growth and avoid a credit crisis, curbing capital flight, and keeping the cur-rency stable. The bottom line is, something has to give. At the start of 2016, capital flight seems to be winning.

Are capital outflows a problem for China? Not yet, and we don’t think they will be. RMB weakness has led to outflows, but we expect the net outflows to slow or stop as the currency stabiliz-es. Keep in mind that China still has ample reserves of US$3.2 trillion. Part of the decline is also related to Chinese corporations redeeming USD-denominated bonds and issuing RMB-denom-inated bonds, which counts against reserves. Lastly, China is still running a trade surplus, so reserves are replenished on an ongoing basis.

DOES A CURRENCY WAR AWAIT?Some fear that the devaluation of the RMB will spark a currency war that could lead to a widespread fall in Asian currencies. We don’t foresee this outcome. China is no longer fighting to be the low-cost producer to the world, so it is not likely to undertake a massive devaluation to boost exports.

Recent policy communications from the PBOC have repeatedly emphasized the referencing of its currency to a basket of cur-

rencies. Indeed, despite the volatility of the RMB’s exchange rate against the US dollar, its levels against the currency basket have been quite stable of late.

We think this stability against the currency basket will remain the policy objective in the near term (Display 11). All told, what’s our view? In short, we’re not in the camp forecasting a big devalua-tion. Nor do we expect the PBOC to start a depreciation of the RMB against a broad currency basket—if it did, the RMB would fail to gain much credibility as a reserve currency.

BRACE FOR THE FUTURE Undoubtedly, there will be bumps along the way. Yet, if China does indeed successfully meet these challenges, the effect, in our view, will be a sense of future shock among investors who have not prepared for it. We believe that the best way for investors to position themselves ahead of such an event is to devote more effort to balancing exposure to both the risks and opportunities in China in their portfolios.

DISPLAY 11: BASKET REMAINS STEADY DESPITE SPOT RATE DROP VS. USDRMB Exchange Rates and Currency Basket

CNH/USD

CNY/USD

90

95

100

105

Oct 15 Nov 15 Dec 15 Jan 16

Inde

x

CFETS RMB Basket*

As of January 13, 2016December 31, 2014 = 100*China Foreign Exchange Trade SystemSource: Bloomberg and AB

Investors would be wise to understand not just China’s downside risks, but also

the upside opportunities.

BER-1283-0416bernstein.com

The [A/B] logo is a registered service mark of AllianceBernstein, and AllianceBernstein® is a registered service mark, used by permission of the owner, AllianceBernstein L.P.

© 2016 AllianceBernstein L.P.

NOTE TO ALL READERSThe information contained herein reflects the views of AllianceBernstein L.P. or its affiliates and sources it believes are reliable as of the date of this publication. AllianceBernstein L.P. makes no representations or warranties concerning the accuracy of any data. There is no guarantee that any projection, forecast, or opinion in this material will be realized. Past performance does not guarantee future results. The views expressed herein may change at any time after the date of this publication. This document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. AllianceBernstein L.P. does not provide tax, legal, or accounting advice. It does not take an investor’s personal investment objectives or financial situation into account; investors should discuss their individual circumstances with appropriate professionals before making any decisions. This information should not be construed as sales or marketing material or an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, product, or service sponsored by AllianceBernstein or its affiliates.

INFORMATION ABOUT MORGAN STANLEY CAPITAL INTERNATIONAL (MSCI)MSCI makes no express or implied warranties or representations and shall have no liability whatsoever with respect to any MSCI data contained herein. The MSCI data may not be further redistributed or used as a basis for other indexes or any securities or financial products. This paper has not been approved, reviewed, or produced by MSCI.