DIKTAT PHONOLOGY.docx

-

Upload

baihaqi-bin-muhammad-daud -

Category

Documents

-

view

20 -

download

9

Transcript of DIKTAT PHONOLOGY.docx

P a g e | 1

CHAPTER ONEINTRODUCTION TO PHONOLOGY AND PHONETICS

Definitions:

PHONOLOGY: The branch of linguistics which studies the use of sound in human language. Phonetics is the study of the physical nature of speech sounds and speech production: how sounds are produced by the human body, what they are like as sound waves, and how the human ear processes speech. Phonology is the study of how sound is structured in languages -- for instance, which of all possible speech sounds a language uses to build its words, how syllables are built in a particular language, and other phenomena. Phonology & phonetics have been studied in detail for about 200 years. The mission of phonology is to understand how speech sounds and phonetic features are organized in a language so that they can be used to create CONTRAST, the differences between sounds that allow the creation of different words, which can then serve the purpose of symbolizing the thousands of concepts that constitute our mental world. The job of phonemes in language is to differentiate words from one another. For instance, the difference between the /s/ and /z/ sounds of English signals that 'sue' and 'zoo' are different words. Phonology makes very detailed descriptions of sounds

Understanding how speech sound are made helps linguists figure out where language came from and where are going

Understanding and learning about Phonology is important for a number of reasons, some of which were outlined in a study by Louisa Moats and Carol Tolman entitled “Why Phonological Awareness is Important for Reading and Spelling” a) Teaching non-native speakers, b) Predicting later educational issues, c) Learning other languages, d) Understanding sounds, e) Helping poor students and f) Stressing the importance of vocabulary

Phonology is one of the fields of speech therapy it is also related to other aspects such as phonetics, morphology, syntax and pragmatics

Phonology is the basis for further work in morphology, syntax, discourse and orthography design

Analyzes the sound pattern of a particular language by determining which phonetic sounds are significant and explaining how these sounds are interpreted by the native speaker

Phonology is the study of speech sounds in language or a language with reference to their distribution and patterning and to tacit rules governing pronunciation

Definition of Phonetics:

P a g e | 2

Phonetics is the study of human sounds and phonology is the classification of the sounds within the system of a particular language or languages.

Phonetics is divided into three types according to the production (articulatory), transmission (acoustic) and perception (auditive) of sounds.

Three categories of sounds must be recognised at the outset: phones (human sounds), phonemes (units which distinguish meaning in a language), allophones (non-distinctive units).

Phonetics (from the Greek word “phone”= sound/voice) is a fundamental branch of linguistics 1. Phonetics is the study of the articulatory and acoustic properties of the sounds of human language. 2. Phonetics is the study of the sounds of language. These sounds are called phonemes.

CHAPTER TWO

P a g e | 3

AREAS OF PHONETICS: ACOUSTIC, AUDITORY AND ARTICULATORY

Phonetic has three different aspects: Articulation Phonetics, Acoustic Phonetics and Auditory Phonetics

ARTICULATORY PHONETICS:

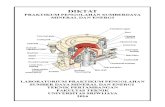

Articulatory Phonetics is describes how vowels and consonants are produced or articulated in various parts of the mouth and throat. The position, shape, and movement of articulators or speech organs such as the lips, tongue and vocal folds

Articulatory Phonetics is the study of how the vocal tract is used to produce (articulate) speech sounds. Further it studies how speech sounds are combined in words and in connected speech and how they vary their place of articulation in the vocal tract, their manner of articulation, whether the vocal cords are activated during production of the sound.

Articulatory Phonetics is a branch of phonetics which is largely based on data provided by other sciences, among which the most important are human anatomy and physiology.

All the sounds we make when we speak are the result of muscles contracting. The muscles in the chest that we use for breathing produce the flow of the air that is needed for almost all speech sound; muscles in the larynx produce many different modifications in the flow of the air from the chest to the mouth. After passing through the larynx, the air goes through what we call the vocal tract, which ends at the mouth and nostrils. Here the air from the lungs escapes into the atmosphere. We have a large and complex set of muscles that can produce changes in the shape of the vocal tract and in order to learn how the sounds of speech are produced it is necessary to become familiar with the different part of the vocal tract. These different parts are called articulators and the study of them is called articulatory phonetics.

Articulatory Phonetics consist of pharynx, velum, hard palate, alveolar ridge, tongue, teeth and lips

Articulator phonetics- focuses on the vocal structures of the throat that helps someone produce sounds. Articulatory Phonetics - describes how vowels and consonants are produced or “articulated” in various parts of the mouth and throat; The position, shape, and movement of articulators or speech organs, such as the lips, tongue, and vocal folds.

ACOUSTIC PHONETICS:

Acoustic Phonetics is an area that focuses on the physical structures of phonetics (the structures of sounds and their placement to produce words.

P a g e | 4

Acoustics Phonetics is a study of how speech sounds are transmitted when sound travel through the air from the speaker’s mouth to the hearer’s ear it does so in the form of vibration in the air.

Acoustic Phonetics is the study of the physical properties of speech sounds made by the human vocal tract.

Acoustic Phonetics is study the physical parameters of speech sounds. It is the most technical of all disciplines that are concerned with the study of verbal communication.

Acoustic phonetics- an area that focuses on the physical structures of phonetics (the structures of sounds and their placement to produce words. Acoustic Phonetics - a study of how speech sounds are transmitted: when sound travels through the air from the speaker's mouth to the hearer's ear it does so in the form of vibrations in the air; The spectro-temporal properties of the sound waves produced by speech, such as their frequency, amplitude, and harmonic structure.

AUDITORY PHONETICS:

Auditory Phonetics focuses on the perception of sounds or the way in which sounds are heard and interpreted.

Auditory Phonetics deals with the other important participant in verbal communication

Auditory Phonetics is the study of phonetics that focuses on the ear and its relationship to speech production and sounds are used for communication. Auditory Phonetics is the study of how people perceive speech sounds. It investigates how people recognize speech sounds as distinct from other sounds in the environment and how they interpret them.

Auditory Phonetics is the study of the way listeners perceive these sounds and deal with the other important participant in verbal communication

When discussing the auditory system we can consequently talk about its peripheral and its central part.

Auditory Phonetics investigates the perception of speech sounds by the listener and how sounds are transmitted from the ear to the brain and how they are processed.

The study of phonetics that focuses on the ear and its relationship to speech production and sounds used for communication. Auditory Phonetics - a study of how speech sounds are perceived: looks at the way in which the hearer’s brain decodes the sound waves back into the vowels and consonants originally intended by the speaker. the perception, categorization, and recognition of speech sounds and the role of the auditory system and the brain in the same

P a g e | 5

CHAPTER THREEROLES OF PHONOLOGY

Some requirement of a phonological feature system is as follows:

The system should be relatively economical It should enlighten us about which combinations of features can go together

universally and therefore which segments and segment types are universally possible. That is many universal redundancy rules of the sort in should not have to be written explicitly as they will follow from the feature system.

It should allow us to group together those segments and segmenting types which characteristically behave similarly in the world’s languages.

The major class features identify several categories of sounds which recur cross-linguistically in different phonological rules. Feature notation can also show why certain sounds behave similarly in similar contexts, within these larger classes. For instance, English /p/, /t/ and /k/ aspirate at the beginnings of words. All three are unaspirated after /s/; and no other English phoneme has the same range of allophones in the same environments. In feature terms although /p/, /t/, /k/ differ in place of articulation, all three are obstruent consonants and within this class are (-voice, -nasal, -continuant). A group of phonemes which show the same behavior in the same contexts and which share the same features constitute a natural class. More formally an natural class of phonemes can be identified using a smaller number of features than any individual member of that class. The class of voiceless plosives, /p/, /t/ and /k/ can be defined uniquely using only three features. If we subtract one of the plosives, we need more features since we must then specify the place of articulation and the same is true in defining a single plosive unambiguously

/p t k/ /p t / /p/

- voice - voice - voice - Nasal - nasal - nasal- Continuant - continuant - continuant

+ anterior +anterior - coronal

Phonological rules very typically affect natural classes of phonemes. For example, medial voicing of /f/ to /v/ did not affect that labial fricative, but also the other members of the voiceless fricative class, /s/ and /0/. If we wrote a rule for /f/ alone, it would have to exclude the other voiceless fricatives, so that the input would have to include ( +anterior, -coronal) however, the more general fricative voicing rule in requires fewer features to characterize the input as we would expect when a natural class is involved.

P a g e | 6

+continuant

+consonantal +voice +voice +voice

-voice

This rule also neatly captures the connection between the process and its conditioning context, and therefore shows the motivation for the development: the fricatives, which are generally voiceless, become voiced between voiced sounds. This will often mean between vowels as in beafon and blaford but it may also mean between a vowel and a voiced consonant and in baefde If voicing takes place between voice sounds, instead a having to switch off vocal fold can continue vibrating through the whole sequence. Voicing the fricative in this context is therefore another example of assimilation where one sound is influenced by another close to it the utterance.

Paradoxically phonological rules are not rules in one of the common, everyday English meanings of that word they aren’t regulations which spell out what must happen. Instead, they are formal descriptions of what does happen, for speaker of a particular variety of a particular language at a particular time. Some phonological rules may also state what sometimes happens, with the outcome depending on issues outside phonology and phonetics altogether. For example: if you say hamster slowly and carefully, it will sound like hamste or hamster depending on whether you drop your r in this context or not we return to this issue. If you say the word quickly several times, you will produce something closer to your normal, casual speech pronunciation and it is highly likely that there will be an extra consonant in there giving (hampste) or (hampste) instead. As the rate of speech increases, adjacent sounds influence one another even more than usual.

P a g e | 7

CHAPTER FOURPHONE, PHONEMES AND ORTHOGRAPHY

A. DEFINITION OF PHONE:

Phone is a speech sound as it is without taking into consideration its function in a given language. It's a representation on the phonetic level and is a phonetic unit.

Phone: Basic speech sound of a language. A minimal sound difference between two words for example: too vs. zoo. Not every sound made by a human speaker is phonetic, for example: Sniffs, laughs, coughs, breath.

Phones is any single phonetic segment irrespective of what its phonological status may be

The term phoneme has become very widely used for a contrastive unit of sound in language: however, a term is also needed for a unit at the phonetic level, since there is not always a one-to-one correspondence between units at the two levels. For example, the word ‘can’t’ is phonemically kɑ_nt (four phonemic units), but may be pronounced kɑ˜ t with the nasal consonant phoneme absorbed into the preceding vowel as nasalisation (three phonetic units). The term phone has been used for a unit at the phonetic level, but it has to be said that the term (though useful) has not become widely used; this must be at least partly due to the fact that the word is already used for a much more familiar object.

Three categories of sounds must be recognized at the outset: phones (human sounds), phonemes (units which distinguish meaning in a language), allophones (non-distinctive units).

B. DEFINITION OF PHONEMES:

Phoneme: Class of speech sounds. Phoneme may include several phones for example: /t/ in top, stop, little, butter, winter

Phoneme, however, is a representation of a speech sound and it's an abstractive unit. It is the smallest contrastive linguistic unit that is capable of bringing about a change of meaning.

The basic building block of any discussion of articulatory phonetics is phoneme. The technical term phoneme is usually used to refer to sound segments. Linguists define phoneme as the minimal unit of sound (or sometimes syntax). The study of phonemes is the study of the sounds of speech in their primary function, which is to make vocal signs that refer to the fact that different things sound different. The phonemes of a

P a g e | 8

particular language are those minimal distinct units of sound that can distinguish meaning in that language.

Sometimes we find various realizations of the same phoneme and these are called allophones. For example there are two types of /l/ in English. One is the dark 'l' and the other is the light /l/. The light /l/ always occurs at the beginning of a word and the dark /l/ can be found in the middle or at the end of the word. They differ slightly in terms the way we pronounce them so we are surely dealing here with the different values of consonants but they are not different phonemes because they do never bring a change of meaning. In the word 'lull' for instance we have both - the light /l/ is first and the dark /l/ is second. If we pronounce them the other way round, the word may sound odd to a native English speaker, but will be still understood as 'lull' - no change of meaning takes place. Allophones occur consistently in different words or in different positions in a word. They are in 'complementary distribution' - they don't contrast with each other. In the case of phonemes we are dealing with 'parallel distribution' - they may contrast in one place in a word.

In English, the /p/ sound is a phoneme because it is the smallest unit of sound that can make a difference of meaning if, for example, it replaces the initial sound of such words as bill, till, or dill, making the word pill. The vowel sound /ɪ/ of pill is also a phoneme because its distinctness in sound makes pill, which means one thing, sound different from pal, which means another. Two different sounds, reflecting distinct articulatory activities, may represent two phonemes in one language but only a single phoneme in another. Thus phonetic /r/ and /l/ are distinct phonemes in English.

Phonemes are not letters; they refer to the sound of a spoken utterance. For example, flocks and phlox have exactly the same five phonemes. Similarly, bill and Bill are identical phonemically, regardless of the difference in meaning.

Phonemes are The Sounds of Language. Phonemes include all significant differences of sound, including features of voicing, place and manner of articulation, accents, and secondary features of nasalization and labialization.

The component of English phonology most important to spelling is the English phoneme inventory: the letters in our alphabet are used to represent these phonemes. Phonemes are the individual sounds that words are composed of in our mental lexicon (our mental inventory of English vocabulary).

For practical purposes, the total number of phonemes for a language is the least number of different symbols adequate to make an unambiguous graphic representation of its speech that any native speaker could read if given a sound value for each symbol, and that any foreigner could pronounce correctly if given additional rules covering no distinctive phonetic variations that the native speaker makes automatically. For convenience, each phoneme of any language may be given a symbol.

This is the fundamental unit of phonology, which has been defined and used in many different ways. Virtually all theories of phonology hold that spoken language can be broken down into a string of sound units (phonemes), and that each language has a small, relatively fixed set of these phonemes. Most phonemes can be put into groups; for example, in English we can identify a group of plosive phonemes p, t, k, b, d, _, a

P a g e | 9

group of voiceless fricatives f, θ, s, ʃ, h, and so on. An important question in phoneme theory is how the analyst can establish what the phonemes of a language are. The most widely accepted view is that phonemes are contrastive and one must find cases where the difference between two words is dependent on the difference between two phonemes: for example, we can prove that the difference between ‘pin’ and ‘pan’ depends on the vowel, and that i and _ are different phonemes. Pairs of words that differ in just one phoneme are known as minimal pairs. We can establish the same fact about p and b by citing ‘pin’ and ‘bin’. Of course, you can only start doing commutation tests like this when you have a provisional list of possible phonemes to test, so some basic phonetic analysis must precede this stage. Other fundamental concepts used in phonemic analysis of this sort are complementary distribution, free variation, distinctive feature and allophone.

In a word ''rat'' - we have 3 phonemes (remember: representations of speech sounds): /r/, /a/, /t/. In a word ''sat' we also have 3 phonemes: /s/, /a/, /t/.

There is only one phoneme difference in the words above (/r/ - /s/). This phoneme brings about the change of meaning because surely the meaning changes depending on whether we pronounce /r/ or /s/ as the first speech sound of the given word.

Pairs such as 'rat' - 'sat', 'pot' - 'tot', 'car' - 'far' and many others are pairs differing in terms of only one phoneme are called 'minimal pairs' and the contrast between the two words in each pair is called 'minimal contrast'.

Phoneme is a fundamental unit in phonological structure for speech sound that contrast or distinguish words abstract mental representations of a phonological units of language

The smallest distinct sound unit in a given language: e.g. /»tIp/ in English realizes the three successive phonemes, represented in spelling by the letters t, i, and p.

There is an abstract as the basis of our writing, so there is an abstract set of units as the basis of our speech. These units are called Phonemes and the complete of these units is called the Phonemic system of the language.

The phonemes themselves are abstract, but there are many slightly different ways in which we make the sounds that represent these phonemes, just as there are many ways in which we may make a mark on a piece of paper to represent a paper to represent a particular abstract.

The phoneme is the smallest unit of sound which can differentiate one word from another: in other words, phonemes make lexical distinctions. So if we take a word like ‘cat’, [kat], and swap the [k] sound for a [p] sound, we get ‘pat’ instead of ‘cat’. This is enough to establish that [k] and [p] are linguistically meaningful units of sound, i.e.

P a g e | 10

phonemes. Phonemes are written between slashes, so the phonemes corresponding to the sounds [p] and [k] are represented as /p/ and /k/ respectively.

The phonemes is defined as a phonetic reality, “a family of sound in a given language, consisting of an important sound of the language together with other related sounds, which take its place in particular sound sequence.

The phoneme is defines as a phonological reality, the sum of the phonologically relevant properties of a sound

The phoneme is defined as psychological reality, “a mental reality the intention of as speaker or the impression of the hearer.

Phonemes are phonological (not phonetic) units, because they relate to linguistic structure and organization; so they are abstract units. On the other hand, [p] and [k] are sounds of speech, which have a physical dimension and can be described in acoustic, auditory or articulatory terms; what is more, there are many different ways to pronounce /p/ and /k/, and transcribing them as [p] and [k] captures only some of the phonetic details we can observe about these sounds.

Phoneme theory originated in the early twentieth century, and was influential in many theories of phonology; however, in recent decades, many phonologists and phoneticians have seen phonemes as little more than a convenient fiction. One reason for this is that phonemic representations imply that speech consists of units strung together like beads on a string. This is a very unsatisfactory model of speech, because at any one point in time, we can usually hear cues for two or more speech sounds.

To qualify as allophones of the same phoneme, two or more phones that is sounds, must meet two criteria. First their distribution must be predictable: we must be able to specify where one will turn up and where the other and those sets of contexts must not overlap. If this is true, the two phones are said to be in complementary distribution. Second, if one phone is exceptionally substituted for the other in the same context, that substitution must not correspond to a meaning difference.

C. DEFINITION OF ORTHOGRAPHY:

A single orthographic letter is realized in many different ways (in English)

– b comb, tomb, bomb

– c court, center, chess

– oo food, good, blood

P a g e | 11

– s reason, sunrise, shy, collision

• A single sound can be written in many different ways (in English)

– [i] sea, see, scene, receive, thief, miss

– [s] cereal, same, miss

– [u] true, few, choose, lieu, do

[ay] lie, prime, pry, buy,

CHAPTER FIVE

P a g e | 12

ARTICULATION: VOWELS AND CONSONANTS

A. ARTICULATION: VOWELS

Phonetically, vowels are produced without any obstruction of air and phonologically vowels usually occupy the centre of a syllable

Tongue and lip movements result in varying shapes of the mouth which can be described in terms of 1) closeness/openness, 2) frontness/backness and 3) the shape of the lips. These are the three criteria for the description of vowel phonemes

Closeness/Openness or the tongue height in American terminology refers to the distance between the tongue and the palate (and at the same time to the position of the lower jaw). If the tongue is high as in the last sound of the word “bee”, it is close to the palate, and we therefore speak of a close vowel. If the tongue is low, as in the third sound of the word “starling”, the gap between it and the palate is more open and we speak of an open vowel.

Between these extremes, there are three intermediate levels: If the tongue is in a mid-high position, i. e a bit lower than high, the resultant sound is a mid-close vowel, or half-close vowel. If it is mid-low, i.e a bit higher than low, we hear a mid-open vowel or half-open vowel.

A vowel that is made with a tongue height somewhere between mid-high and mid-low is simply called a mid vowel

Frontness/Backness refers to the part of the tongue that is raised highest. If it is the front of the tongue (in which case the body of the tongue is pushed forward), as in the last sound in “bee”, we speak of a front vowel. If the back of the tongue is raised highest (in which case the body of the tongue is pulled back), as in the middle sound in “goose”, the resultant sound is a back vowel.

Between these extremes, we recognize on intermediate position: If the centre of the tongue is raised highest, as in the second sound of the word “bird”, we speak of a central vowel.

The shape of the lips can be either spread, neutral or round. English does not utilize this contrast very much. As in most other languages, the spreading of the lips usually correlates with frontness and lip-rounding with backness. This means that there are no two phonemes in English that differ only in the shape of the lips.

Many linguists therefore do not regard this criterion as relevant in English. The effect that the shape of the lips has on the vowel quality can be heard when we compare the second sound in “hurt” (which is the same as the one in bird above). Both sounds are mid central vowels and they are identical with respect to closeness/openness and frontness/backness.

The closeness or openness of a vowel is shown by the vertical position of the symbol in the vowel chart. The higher the symbol, the closer the tongue is to the palate when articulating the corresponding sound. Conversely, the lower the symbol, the more open the gap between the tongue and the palate. In order words, close vowels occupy the upper part of the vowel chart and open vowels the lower part. Two horizontal lines mark the mid-close and mid-open positions.

P a g e | 13

Frontness or backness is indicated by the horizontal position of the symbols. The further left the symbol, the more front the part of the tongue that is raised highest when articulating the corresponding sound. Thus the symbols on the left of the vowel chart represent front vowels. The further right the symbol, the more back the part of the tongue involved. The symbols of the right then represent back vowels. It goes without saying that the vowel in the central area of the chart is central vowels.

The vowel systems of the most languages of the world can be represented by symbols that are evenly distributed within the vowel chart. This phenomenon is called vowel dispersion. Most vowel systems are arranged within a triangle. English belongs to the less than 10% of the languages whose vowels systems have a more or less quadrilateral shape. The vowel chart is then sometimes called a vowel quadrilateral.

In order to describe the vowels of any given language and compare the vowel systems of different languages more precisely than is possible by using only the distinctive features. Daniel Jones invented 18 reference vowels called cardinal vowels.

All cardinal vowels can be represented by phonetic symbols. Unfortunately, some of these symbols are identical with the symbols that we use to represent English vowels even though the quality of the sounds is quite different.

Because the cardinal vowels are no part of a sound system of a language, their symbols are usually enclosed in square brackets, like any other concrete sound.

Front central back

Close (1) i (9) y (17) i (18) u (16) ш (8) u

Mid-close (2) e (10) Ф (15) (7) o

Mid-open (3) e (11) æ (14) Λ (6)

Open (4) a (12) (5) a (13)

Since the cardinal vowels are extremes, they occupy the very edges of the vowel chart. They are numbered counter-clockwise, beginning in the upper left corner. The vowels 1 to 8 are the Primary cardinal vowels. They can be described as close front, mid-close front, mid-open front, open back, mid-open back, mid-close back, and close back.

The secondary cardinal vowels are the vowels 9 to 16. They occupy the same position as the primary cardinal vowels in the vowel chart, but they sound less familiar to us because the shape of the lips is reversed. Vowels 9 to 13 are produced with rounded

P a g e | 14

and vowels 14 to 16 with unrounded lips. The two remaining cardinal vowels 17 and 18 are close central vowels with unrounded and rounded lips.

We now list the 5 long vowel phonemes, describe their manner of articulation and label them according to the two distinctive features:

The last sound in the word” bee” represented by the symbol /i:/. The front of the tongue is raised so that it almost touches the palate and the lips are slightly spread. This mean is A Close Front Vowel.

The second sound in “bird” represented by / /. This sound is also well known as a hesitation sound, usually spelt er. The centre of the tongue is raised between mid-close and mid-open position and the lips are a neutral shape. This mean is A Mid Central Vowel.

The third sound in “starling” represented by / a: /. The part of the tongue between the centre and the back is lowered to fully open position and the lips are in neutral shape. This mean is An Open Central-Back Vowel.

The second sound in “horse” represented by / : /. The back of the tongue is raised between mid-close and mid-open position and the lips are rounded. This mean is A Mid Back Vowel

The middle sound in “goose” represented by / u:/ The back of the tongue is raised so that it almost touches the palate and the lips are moderately rounded. This mean is A Close Back Vowel.

The middle sound in “fish” represented by / i/. The part of the tongue between the front and the centre is raised to just above mid-close position and the lips are slightly spread. This mean is A Mid-Close Front-Central Vowel.

The first sound in “egg” represented by /e/ the front of the tongue is raised between mid-close and mid-open position and the lips are slightly spread. This mean is A Mid Front Vowel.

The first sound in “apple” represented by / /. The front of the tongue is raised between mid-open and fully open position and the lips are slightly spread. This mean is A Mid-Open Front Vowel.

The second sound in “butter” represented by / / the centre of the tongue is raised between mid-open and fully-open position and the shape of the lips is neutral. This mean is Mid-Open-Open- Central Vowel.

The first sound in “olive” represented by / / the back of the tongue is lowered to almost fully open position and the lips are slightly rounded. This mean is An Open Back Vowel

The second sound in “pudding” represented by / / the part of the tongue between the centre and the back is raised to just above mid-close position and the lips are rounded. This mean is A mid-close central-back vowel.

The third sound in “spaghetti” the first sound in “ago” or the last sound in “mother” represented by / /, the centre of the tongue is raised between mid-close and mid-open position and the lips are in a neutral shape. This mean is A mid central vowel.

All English vowel phonemes in unstressed syllables, rather than as a phoneme in its own right. They prove the validity of their approach with word pairs like

P a g e | 15

“compete”/competition or “analysis/analyze where /i:/ and / / seem to be neutralized or reduced . This is called by neutral vowels or reduced vowel.

Below is the example of vowels in stressed and unstressed syllables and in reduced syllables The red type shows the vowel under consideration

Below is the example of vowels in stressed and unstressed syllables and in reduced syllables. The red type shows the vowel under consideration.

P a g e | 16

The distribution of tense and lax vowels in stressed syllables in American English

The distribution of tense and lax vowels in stressed syllables in British English

P a g e | 17

P a g e | 18

P a g e | 19

P a g e | 20

B. ARTICULATION: CONSONANT

Consonants are sounds that are produced by an obstruction of an air stream either in the pharynx or in the vocal tract.

There are 24 consonant phonemes in rules of phonology and in most other accents of English

Consonants therefore include all sounds which are not voiced (e.g. p, s ) all sound in the production of which the air has an impeded passage through the mouth (e.g, b, l rolled r) all sounds in the production of which the air does not pass through the mouth (e.g. m) and all sounds in which there is audible friction (e.g. f, v, s, z, h )

The distinction between vowels and consonants in not an arbitrary physiological distinction. It is in reality a distinction based on acoustic consideration, namely on the relative sonority or carrying power of the various sounds.

There are many more consonants than vowels. English only has a fraction of the full range of possible consonants, so illustration of many of these symbols involves more extensive consideration of languages other than English. Most English dialects systematically use the following consonants: (9) p pig b big m mug f fog v varmint _ thing d this t top s sop d dog n nog _ chuck _ shuck _ jug _ measure k cotg got ŋ hang h horse

Other segments used in English include r, l, z, h: this is only a partial list. There are a few additional phonetic segments found in English which, because they only arise due to general rules of the type to be discussed in the next chapter, are not immediately obvious: (10) _ voiceless bilabial fricative; variant of p found in words like rasps in casual speech. x variant of k found in words like masks in casual speech; also found in German, Russian, Greek, Scots (English). _ labiodental nasal; variant of m found before [f ] and [v] as in comfort. t_ dental t. Found in English before [_]: the word width is actually pronounced [wιt__]. Also how t is pronounced in French.n_ dental n; found in English before [_] as in panther. ʔ glottal stop; found in most dialects of American English (except in certain parts of the American south, such as Texas) as the pronunciation of t before syllabic n, i.e. button. Also stereotypical of British “Cockney” pronunciation bottle, coulda. ɾ flapped t in American English water

Some other consonants found in European languages, for instance, are the following. (11) pf, ts voiceless labiodental and alveolar affricates found in German (<Pfanne> [pfanə] ‘pan’, <Zeit> [tsait] ‘time’) _ voiced bilabial fricative, found phonetically in Spanish (<huevo> [we_o] ‘egg’) _ voiced velar fricative, found in Modern Greek ([a_apo] ‘love’) and Spanish (<fuego> [fwe_o] ‘fire’)

Many consonants are only encountered in typically unfamiliar languages, such as retroflex consonants (t , etc.) found in Hindi, Tamil and Ekoti, or uvulars and pharyngeals such as q, _, _ found in Arabic.

Consonant symbols are traditionally given in tabular form, treating the place of articulation where the major constriction occurs as one axis, and treating properties such as voicing, being a continuant, or nasality as the other axis. Eleven places of

P a g e | 21

articulation for consonants are usually recognized: bilabial, labiodental, dental, alveolar, alveopalatal, retroflex, palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal and laryngeal, an arrangement which proceeds from the furthest forward to furthest back points of the vocal tract: see figure 9 of chapter 1 for anatomical landmarks. Manner of articulation refers to the way in which a consonant at a certain place of articulation is produced, indicating how airflow is controlled: the standard manners include stops, fricatives, nasals and affricates. A further property typically represented in these charts is whether the sound is voiced or voiceless. The following table of consonants illustrates some of the consonants found in various languages, organized along those lines.1 (12) Consonant symbols Consonant manner and voicing Place of vcls vcls vcls vcd vcd vcd nasal articulation stop affricate fricative stop affricate fricative bilabial p (p_) _ b (b_) _ m labiodental pf f bv v _ dental t_ t_ _ d_ dd d n_ alveolar t ts s d dz z n alveopalatal _, t_ _ _, d_ _ n retroflex t t s s d d z

z n palatal c (cç) ç _ __ _ n velar k kx x g g_ _ ŋ uvular q q_ _ G G_ , Gʁ _ , ʁ ŋ , N pharyngeal _ ʕ laryngeal_ ʔ h _ glottal

Consonants in English are distinguished from vowels on the basis of the modifications of pulmonary air in the oral cavity. Consonants are distinguished from one another on the basis of their differences in three respects: (a) manner of articulations, (b) place of articulation, and (c) voicing. By way of contrast, vowels are distinguished from one another on the basis of two criteria: (a) relative position of the tongue in the mouth, and (b) lip rounding.

Consonant is the general term that refers to a class of sounds where there is obstruction of some kind (i.e., complete blockage, or constriction) to the flow of pulmonary air. As it was mentioned earlier, there are six different degrees of obstruction. Therefore, consonants can be classified into six different categories on the basis of their manner of articulation:

TYPE PHONEME PLOSIVES /p/ /b/ /t/ /d/ /k/ /g/

FRICATIVES /f/ /v/ /θ/ /ð/ /h/ /s/ /z/ /ʃ/ /ʒ/ AFFRICATES /ʧ/ /ʤ/ NASALS /m/ /n/ /ŋ/

APPROXIMANT /r/ /w/ /j/ LATERAL /l/

However, as the table shows, more than one consonants fall within almost all of these categories. Therefore, other criteria are needed to distinguish one consonant from the other. For example, /p/ and /b/ cannot solely be distinguished on the basis of their manner of articulation. Moreover, they are articulated at the same place of articulation. Yet they are different since they assign different meanings to the two English words 'pat' /pæt/ and 'bat' /bæt/.

P a g e | 22

Consonants that share the same manner of articulation may be different in terms of place of articulation. Consonants are classified into nine different classes according to their place of articulation:

TyTYPE PHONEME BILABIAL /m/, /p/, /b/

LABIODENTAL /f/, /v/ INTERDENTAL /θ/, /ð/

ALVEOLAR /t/, /d/, /n/, /s/, /z/, /r/, /l/ PALATOALVEOLAR /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /ʧ/, /ʤ/

PALATAL /j/ LABIOVELAR /w/

VELAR /k/, /g/, /ŋ/ GLOTTAL /

Even those consonant that share the place and manner of articulation may be different in terms of voicing and nasality. According to the level of vibration of the vocal cords, consonants are classified into two groups: voiced, and voiceless:

TYPE PHONEME VOICELESS /ʧ/, /s/, /p/, /k/, /f/, /ʃ/, /t/, /θ/, /h/

VOICED /ʤ/, /z/, /b/, /g/, /v/, /ʒ/, /d/, /ð/, /w/, /j/, /l/, /r/, /m/, /n/, /ŋ/

On the basis of nasality, consonants are divided into two groups: nasal, and non-nasal. As you have already noticed, nasality is identified by a free flow of air through the nose.

TYPE PHONEME NASAL /m/, /n/, /ŋ/

NON-NASAL /ʤ/, /z/, /b/, /g/, /v/, /ʒ/, /d/, /ð/, /w/, /j/, /l/, /r/, /ʧ/, /s/, /p/, /k/, /f/, /ʃ/, /t/, /θ/, /h/

These differences in place of articulation, manner of articulation, nasality, and voicing led traditional phoneticians to assign different names to different consonants. The name that was given to any given consonant was based on the air stream mechanism which led to the articulation of that consonant:

Consonant name = Place of articulation + voicing + manner of articulation

For example the consonant /p/ would be identified as bilabial voiceless stop. By way of contrast, the consonant /b/ was defined as bilabial voiced stop. As such /b/ and /p/

P a g e | 23

were distinguished on the basis of the level of vibration of the vocal cords (i.e., voicing). /m/ was considered to be a bilabial nasal.

In traditional phonetics, consonants were named after their particular characteristics:

PHONEME TRADITIONAL NAME /p/ Bilabial voiceless stop /b/ Bilabial voiced stop /m/ Bilabial nasal /f/ Labiodental voiceless fricative /v/ Labiodental voiced fricative /θ/ Interdental voiceless fricative /ð/ Interdental voiced fricative /t/ Alveolar voiceless stop /d/ Alveolar voiced stop /n/ Alveolar nasal /s/ Alveolar voiceless fricative /z/ Alveolar voiced fricative /l/ lateral /r/ Alveolar approximant /ʃ/ Palatoalveolar voiceless fricative /ʒ/ Palatoalveolar voiced fricative /ʧ/ Voiceless affricate /ʤ/ Voiced affricate /j/ Palatal approximant /w/ Labiovelar approximant /k/ Velar voiceless stop /g/ Velar voiced stop /ŋ/ Velar nasal /h/ Glottal fricative

Also notice that earlier phoneticians had a tendency to distinguish approximants, glides, and laterals as fricatives. In addition, they also classified /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /ʧ/, /ʤ/, /r/, and /l/ as palatals.

A closer look at the names given to consonants reveals that only the minimum number of criteria needed to distinguish one consonant from the rest should be used to name that consonant. These features are called distinctive features. In addition to distinctive features, there are a number of characteristics of phonemes that can be guessed on the basis of their distinctive features. These predictable characteristics are called redundant features. Redundant features should not be mentioned in the naming of phonemes. The phoneme /ŋ/, for example, is voiced. However, the voicing feature has not been used in its name. This is because it is possible to guess that the phoneme /ŋ/ is voiced due to the fact that it is a nasal consonant. In other words, nasality can predict voicing. Therefore, voicing is said to be a redundant feature for nasal consonants, and is not used in their names. A feature which is redundant for one phoneme may be distinctive for another. For example, whereas voicing is considered to be a redundant feature for the phoneme /ŋ/, it is certainly a distinctive feature for the phonemes /g/, and /k/ because voicing is the only difference between them.

P a g e | 24

Phoneticians usually express redundant features in terms of statements which they call redundancy rules. Thus, the fact that voicing can be predicted by nasality is expressed in the following redundancy rule: whenever a phoneme is nasal, it is deemed to be voiced. Like other scientific fields, phonetics draws on a system of notations to simplify its redundancy rules. Take the following example: [nasal] [voiced] (where is read as 'rewrites as').

´

All consonants generally have two things in common: (a) They are made with an obstruction of air, and (b) they typically occur at the margins of syllables. By contrast, the sounds that (a) are produced without any obstruction of air, and (b) usually occur

P a g e | 25

at the centre of syllables are called vowels. The English frictionless continuants, i.e. the lateral approximant, IM, and the approximants, /r, j , w/, however, do not fit neatly into the consonant category nor into the vowel category. We have so far regarded them as consonant because they always appear at the margins, and never at the centre, of syllables.

CHAPTER SIXDimensions of Articulation: Voice Production, Place of

Articulation and Manner of Articulation

A. VOICE PRODUCTION

All sound that are produced by an egressive pulmonic air stream mechanism and therefore all English sounds pass through the glottis. If the glottis is narrow, and if the vocal folds are together, the air stream forces it’s called voiced.

This velaric ingressive airstream mechanism produces implosive and click sounds through inhalation. A speech sound can also be generated from a difference in pressure of the air inside and outside a resonator. In the case of pharyngeal cavity, this pressure difference can be created without using the lungs at all whereby producing ejective sounds. This is called the glottalic egressive airstream mechanism. The main airstream mechanism in most of the world's languages, however, is the pulmonic egressive airstream mechanism which produces almost all the phonemes of the world's most important languages. In this case, the flow of air originates in the lungs. As such, it is called pulmonic airstream (or simply pulmonic air). It then moves outward through the resonators; hence, the name egressive. When articulators (i.e., parts of the vocal tract that modify the airstream) influence the flow of pulmonic air, sounds are produced. The nature of the modifications that produce one phoneme differs from those of any other phoneme. As it was mentioned earlier, modern or systematic phonetics uses binary phonetic features to describe the nature of these modifications

Pulmonic sound is air flow is directed outwards towards the oral cavity pressure built by compression of lungs for example in English [p], [n], [s], [l], [e]

Glottic Egressive Sounds is air flow is directed outwards towards the oral cavity pressure built by pushing up closed glottis

Glottic Ingressive Sound is Air flow is directed inwards from the oral cavity pressure reduced by pulling down closed glottis

P a g e | 26

Velaric Sounds is air flow is directed inwards from the oral cavity pressure reduced by forming velaric and alveolar closure and pulling down tongue

If the glottis is open, if the vocal folds are apart, the air passes through without causing the focal folds to vibrate. Sounds produced in this way are called voiceless.

B. PLACE OF ARTICULATION

There are thirteen possible places of articulation in the languages of the world, but not all of them are utilized in English. They are usually labeled according to the immobile, upper speech organ used in their production. The mobile, lower speech organ always lies directly opposite

An important feature for the description of consonants is the exact place where the air-stream is obstructed. The place of articulation names the speech organs that are primarily involved in the production of a particular sound

As it was noted earlier, the distinction between manner of articulation and place of articulation is particularly important for the classification of consonants. The place of articulation is the point where the airstream is obstructed. In general, the place of articulation is simply that point on the palate where the tongue is placed to block the stream of air. However, the palate is not the only place of articulation.

The place of articulation can be any of these points: (a) the lips (labials and bilabials), (b) the teeth (dentals), (c) the lips and teeth (labio-dentals—here the tongue is not directly involved), (d) the alveolar ridge (that part of the gums behind the upper front teeth—alveolar articulations), (e) the hard palate (given its large size, one can distinguish between palato-alveolars, palatals and palato-velars), (f) the soft palate (or velum—velar articulations), (g) the uvula (uvulars), (h) the pharynx (pharyngeals), and (i) the glottis (glottals).

After the air has left the larynx, it passes into the vocal tract. Consonants are produced by obstructing the air flow through the vocal tract. There are a number of places where these obstructions can take place. These places are known as the articulators. They include the lips, the teeth, the alveolar ridge, the hard palate, the soft palate, and the throat. Some phoneticians define articulators as the movable parts of the vocal tract.

Bilabial sounds are produced with both lips. There is only one fortis bilabial in English, namely /p/ as in “peach”, whereas there are two lenis bilabials in /b/ as in “banana” and /m/ as in “mango”

P a g e | 27

Some sounds are produced when the pulmonary air is modified (blocked or constricted) by the lips. If both of the lips are used to articulate a sound, then it is said to be a bilabial sound. Examples of bilabial sounds include /p/, /b/ and /m/. Sometimes, the upper teeth and the lower lip collaborate to produce a sound. In this case, the sound is said to be a labiodental sound. In English /f/ and /v/ are labiodental consonants

Labiodental sounds are produced by a movement of the lower lip against the upper teeth. There in one fortis labiodentals in English, namely /f/ as in “film” and one lenis labiodentals in /v/ as in “video”

The two 'th' sounds of English (ð and θ) are formed by forcing air through the teeth. The apex of the tongue is normally inserted between the upper and the lower teeth and air is forced out. This causes a friction which is realized in the form of two different consonant sounds: /ð/ as in this /ðɪs/, and /θ/ as in thin /θɪn/. If you say the soft /θ/ in /thin/ and then the hard /ð/ sound in /then/, you can feel the air being forced through the teeth. The tongue tip and rims are articulating with the upper teeth. These sounds are called dental or interdental sounds. The upper teeth are also used when you say /f/ and /v/. In this case however, air is being forced through the upper teeth and lower lip.

An alveolar sound is produced when the tongue tip, or blade, touches the bony prominence behind the top teeth. This prominence is in fact that part of the gum which lies behind the upper teeth. In English, the following phonemes are alveolar: /t/ as in tin /tɪn/, /d/ as in din /dɪn/, /s/ as in sin /sɪn/, /z/ as in zip /zɪp/, /l/ as in look /lʊk/, /r/ as in roof /ru:f/, and /n/ as in /night /naɪt/. Try saying all of these phonemes to yourself. They do not all touch in exactly the same way due to the manner of articulation. Some are plosives while the others are fricatives or laterals. But the place of articulation is clearly the alveolar ridge for all of them.

pppppPHONEME EXAMPLE PRONUNCIATION /ʃ/ sheep /ʃi:p/ /ʒ/ genre /ˈʒɑ:nrə/ /ʧ/ cheap /ʧi:p/ /ʤ/ jeep /ʤi:p/

Four sounds are said to be palatoalveolar. This is partly because the blade of the tongue straddles both the alveolar ridge and the front of the hard palate as air is forced through to make the sounds. These sounds include /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /ʧ/, and /ʤ/.

This is the hard bit of the arched bony structure that forms the roof of the mouth. The /j/ sound in yes is the clearest example of a palatal sound in RP. You can feel the fricative sound being forced between the tongue and the very top of your mouth. The blade of the tongue touches the hard palate to articulate palatal sounds. Earliest accounts of phonetics also classified affricates as being palatal. Today, however, they are considered to be palatoalveolar rather than palatal per se. Still, there are some phoneticians who prefer the older classification.

P a g e | 28

The soft palate is toward the back of the mouth. It is where the roof of the mouth gives way to the soft area behind it. It can just be felt with your tongue if you curl it as far back and as high as you can so that the apex of your tongue can feel the soft area of the back-roof of your mouth. The soft palate is technically called the velum and sounds which are produced by a constriction or blockage at this part of the vocal tract are called velar sounds. Thus, velar sounds are usually made when the back of the tongue is pressed against the soft palate. They include the /k/ in cat, the /g/ in girl and the /ŋ/ in hang. The glide /w/ is also regarded as a labiovelar sound, because it simultaneously uses both lips whilst raising the back of the tongue towards the velum. Try saying /wheel/ and /win/ and feel the position of your tongue.

Glottal sounds are those sounds that are made in the larynx through the closure or narrowing of the glottis. It was mentioned earlier that there is an opening between the vocal cords which is called the glottis. If pulmonary air is constricted or blocked at this place, glottal sounds are articulated. The glide /h/ as in Helen is an example of a glottal sound. It is physically impossible to feel the process using your tongue. It is as far back as you can get in your mouth. The /æ/ sound, as it appears in Arabic, is an extreme example of a glottal stop. The glottal stop is becoming a more widespread part of British English, but is still uncommon in RP. You also use your glottis for speech when you whisper or speak in a creaky voice.

C. MANNER OF ARTICULATION

Manner of articulation refers to the nature of the obstruction of pulmonary air flow. In order to fully appreciate the differences among speech sounds, as well as indicating the place of articulation, it is necessary to determine the nature and extent of the obstruction of airflow involved in their articulation. The type of airflow obstruction is known as the manner of articulation. The manner of articulation is particularly defined by four major factors: (a) whether there is vibration of the vocal cords (voiced vs. voiceless), (b) whether there is nine /nain/, dine /dain/ line/lain/

They all begin with voiced, alveolar consonants /n/, /d/, and /l/. Yet, they are all clearly different in both sound and meaning. The kinds of constriction made by the articulators are what make up this further dimension of classification. There are two common kinds of constriction that often occur in English: plosive and fricative. Also, there are other less common constrictions: nasal, affricate, lateral, and approximant. Traditional phonetics, however, used three cover terms to refer to all kinds of constriction: plosive, fricative, and affricate. In the following sections, these manners of articulation will be discussed with greater detail so that the reader can fully understand what they mean.

Occlusives require a complete closure of the speech canal, not just a restriction. This distinguishes them from the continuants. The occlusion is twofold: (a) the airstream is halted by a sudden closure in the oral cavity; (b) the trapped air is freed by abruptly releasing the closure. If the trapped air is gradually released, an affricate consonant is articulated. Occlusives in English include /p/, /b/, /m/, /t/, /d/, /n/, /k/, /g/, and /ŋ/. [p] is a voiceless bilabial stop consonant. The lips are pressed tightly together. The air is trapped behind the lips. The vocal cords are kept far apart, and the nasal cavity is closed by the velum. Then the trapped air is suddenly released. [b] is the voiced

P a g e | 29

counterpart of [p]. The only difference is that the vocal cords are close to each other and vibrate during the articulation of [b]. In the case of /m/, the nasal cavity is open.

/b/ and /p/ /t/ and /d/ /k/ and /g/

is a voiceless dental or alveolar stop. The tongue makes contact with the front teeth or with the alveolar ridge directly above them. There is no vocal cord vibration and the nasal cavity is blocked. [d] is a voiced dental or alveolar stop. It is produced in the same way as [t] but with vibration of the vocal cords. In the case of /n/, the nasal cavity is open to let the air pass through it [k] is a voiceless velar stop. With the tongue tip resting against the lower teeth, the back of the tongue makes contact with the soft palate. [g] is its voiced counterpart. Its articulation is the same as [k], but with vibration of the vocal cords. The corresponding velar nasal [ŋ] is usually voiced as well. Some languages have a glottal occlusive [ʔ] too. The glottal stop can be produced in either of the two ways: (a) by the sudden opening of the glottis under pressure from the air below, or (b) by the abrupt closure of the glottis to block the airstream. The glottal stop is always voiceless, as the complete closure of the vocal cords precludes their vibration.

Occlusives can be categorized into two major types: stops and plosives. The two categories are in inclusional distribution. That is, all plosives are stops but all stops are not necessarily plosive. This relationship can be schematically represented as: (PLOSIVE STOP). Plosive sounds are made by forming a complete obstruction to➙ the flow of air through the mouth and nose. The first stage is that a closure occurs. Then the flow of air builds up and finally the closure is released, making an explosion of air that causes a sharp noise. Try to slowly say /p/ to yourself. You should be able to feel the build up of air that bursts into the /p/ sound when you open your lips. It should be noted that a plosive cannot be prolonged or maintained so that once the air has been released, the sound has escaped. As such, plosive sounds lack the length feature. Contrast this quality of plosives with a fricative in which you can lengthen the sound. The plosive sounds in RP are: /b/, /p/, /t/, /d/, /k/, and /g/. As it was mentioned earlier, plosive sounds belong to a more general class of sounds called stops. A stop sound is one in which the flow of air is completely blocked only in the oral cavity. Stops also include such sounds as /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/. Take the following examples: moon /mu:n/, night /nait/, thing /0in/

P a g e | 30

You can feel that in the production of such sounds as /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/ the flow of air is completely blocked in the mouth. However, air can flow through the nose. As such, the air cannot burst into these sounds because they can be lengthened. In addition to these sounds, /ʧ/ and /ʤ/ are also marked by a complete blockage of pulmonary air in the oral cavity. Here, again, the blockage is not followed by an abrupt release. Rather, the blocked air is gradually released to create friction. Some phoneticians rank these two sounds among the stop consonants while many others classify them as affricates. Take the following examples: Jack /djak/, chat /tjat/

A fricative is the type of consonant that is formed by forcing air through a narrow gap in the oral cavity so that a hissing sound is created. Typically air is forced between the tongue and the place of articulation for the particular sound. Try it yourself. Say the /f/ in fin /fɪn/, the /θ/ in thin /θɪn/ and the /ʃ/ in shin /ʃɪn/. You should be able to feel the turbulence created by the sounds. It is possible to maintain a fricative sound for as long as your breath holds out. This is very different from a plosive sound. Other fricatives include the /v/ in van, the /s/ in sin, the /h/ in hat /hæt/, the /ð/ in that /ðæt/, the /z/ in zoo /zu:/ and the /Ʒ/ sound in genre /ˈʒɑ:nrə/.

Fricative consonants result from a narrowing of the speech canal that does not achieve the full closure characteristic of the occlusives. The shape and position of the lips and/or tongue determine the type of fricative produced. Phoneticians usually distinguish between so-called true fricatives and the related class of spirants. During the production of a fricative, the airstream can be directed in several ways. First, in the case of true fricatives, the tongue channels the air through the center of the mouth (like in the case of the dorsal fricatives). Second, the tongue can also channel the air down the side(s) of the mouth (like in the case of the lateral fricatives). Finally, in the case of labial and dental fricatives, the shape and position of the tongue is not important. This makes sense because the place of articulation is not, strictly speaking, in the oral cavity at all.

/f/ /v/

[f] is a voiceless labiodental fricative. The lower lip is brought close to the upper teeth, occasionally even grazing the teeth with its outer surface, or with its inner surface, imparting in this case a slight hushing sound. Considering its place of articulation, it is unimportant to class this sound as dorsal or lateral fricative. [v] is a voiced labiodental fricative. Its articulation is the same as [f], but with vibration of the vocal cords. Like [f], considering its place of articulation, it is unimportant to class [v] as dorsal or lateral fricative.

Among the fricatives are ones described as hissers and hushers. The realization of a hisser requires a high degree of tension in the tongue: a groove is formed along the whole length of the tongue, in particular at the place of articulation where the air

P a g e | 31

passes through a little round opening. English hissers are /s/, /z/, /ʧ/, and /ʤ/. The hushers are produced similarly, but with a shallower groove in the tongue, and a little opening more oval than round. The lips are often rounded or projected outwards during the realization of a husher. English hushers are /ʃ/, and /ʒ/.

HISSER HUSSER

Spirants involve the same restriction of the speech canal as fricatives, but the speech organs are substantially less tense during the articulation of a spirant. Rather than friction, a resonant sound is produced at the place of articulation. [s] is a voiceless alveolar fricative (also a hisser). This apico-alveolar hisser is produced by bringing the end of the tongue close to the alveolar ridge. Hissers like /s/ can be divided into three categories, according to the precise part of the tongue that comes into play: (a) coronal hissers which involve the front margin of the tongue (as in English), (b) apical hissers which involve the very tip or apex of the tongue (as in Castilian Spanish), and (c) post-dental hissers where the front part of the tongue body is involved (as in French). The quality of the sound is noticeably altered in these three types of hissers. The IPA uses diacritical marks to indicate distinctions of this magnitude. [z] is a voiced alveolar fricative (and a hisser). The same mechanism that produces [s] also produces [z] but with vibration of the vocal cords. In general, the remarks made for the voiceless sound are equally valid for the voiced variant. Other hissers are [ʧ] and [ʤ]. [ʧ] is a voiceless palatal fricative. The tongue body forms a groove and approaches the hard palate. In terms of general tongue shape, this articulation qualifies as a hisser. [ʤ] is a voiced palatal fricative. It is articulated in the same way as [ʧ] but with vibration of the vocal cords. [ʃ] is a voiceless alveolar fricative (and a husher). The tip of the tongue touches the alveolar ridge. The groove in the center of the tongue is shallower than is the case for hissers. [ʒ] is its voiced counterpart.

Basically, friction and fricatives develop from tense articulations. When the articulation is lax, resonance, and thus a spirant, occurs. Also realize that many spirants can be thought of as the lax counterparts of stop consonants. English interdentals /ð/ and /θ/ are spirants.

/0/ /

P a g e | 32

is a voiceless dental spirant. The tongue tip is held close to the upper teeth, either behind them (dental) or just underneath them (the interdental articulation). This spirant is the lax counterpart of the stop [t]. Considering its place of articulation, it is unimportant to class this sound as a dorsal or lateral fricative. [ð] is the voiced counterpart of /θ/. Its articulation is the same as /θ/ but with vibration of the vocal cords. This spirant is the lax counterpart of the stop [d].

Fricatives Spirant Lateral

Laterals are generally considered to be a special case, since physically speaking they could be grouped among the fricatives and spirants. They are called laterals since, during their production, the back of the tongue makes contact with the hard palate while the front of the tongue sinks down, channeling the air laterally around the tongue, down the side (or sometimes both sides) of the mouth. On the other hand, for non-lateral articulations, the back of the tongue rests against the top molars, and the air flows over the tongue down the center of the mouth. There are two distinct types of lateral: (a) lateral fricatives, where the articulation, requiring a great deal of muscular tension, resembles that of the fricatives (except for the position of the tongue), and (b) non-fricative lateral, often called liquids, whose articulation is very close to the spirants. It is interesting to note that the location of the lateral channel through which the air flows is unimportant. That is, whether it is on the left, the right, or both sides of the mouth, the nature of the sound produced is unchanged. English laterals are usually non-fricative. In addition, no distinction is made between voiceless and voiced variants because it is very rare for a language to distinguish laterals according to voice. English liquids are /r/ and /l/.

To produce a lateral sound, air is obstructed by the tongue at a point along the centre of the mouth but the sides of the tongue are left low so that air can escape over its sides. In fact, the tongue is strongly flexed and the air is forced through a narrow oval cavity, producing a hushing sound. /l/ is the clearest example of a lateral sound in English. Both the clear [l] and the word-final dark [ɫ] allophones (i.e., the variants of the same phoneme) of /l/ are lateral sounds. When an alveolar plosive is followed by the lateral /l/, then what happens is that we simply lower the sides of the tongue to

P a g e | 33

release the compressed air, rather than rising and lowering the blade of the tongue. If you say the word 'bottle' to yourself you can feel the sides of the tongue lower to let out the air.

An approximant is a consonant that makes very little obstruction to the airflow. Approximants are divided into two main groups: semivowels (also called glides) and liquids. The semivowels are /h/ as in hat /hæt/, /j/ as in yellow /ˈjeləʊ/, and /w/ as in one /wʌn/. They are very similar to the vowels /ɜ:/, /u:/ and /i:/, respectively. However, semivowels are produced as a rapid glide. The liquids include the lateral /l/ and /r/ sounds in that these sounds have an identifiable constriction of the airflow, but not one sufficiently obstructive enough to produce a fricative sound. Approximants are never fricative and never completely block the flow of air.

A nasal consonant is a consonant in which air escapes only through the nose. For this to happen, the soft dorsal part of the soft palate is lowered to allow air to pass it, whilst a closure is made somewhere in the oral cavity to stop air escaping through the mouth. You can feel if a sound is a nasal sound or not by placing your hand in front of your mouth and feeling if any air is escaping or not. There are three nasal sounds in English. The /m/ in mat /mæt/, the/n/ in not /nɒt/ and the /ŋ/ in sing /sɪŋ/ or think /θɪŋk/.

The nasal “occlusives” of the vast majority of the world's languages are voiced. Very few not-so-famous languages have voiceless nasals too. During the production of these nasal “occlusives”, the soft palate is lowered to a greater or lesser extent, allowing a portion of the airstream to pass through the nasal cavity. Occlusion occurs in the mouth only; the nasal resonance is continuous. Indeed, many linguists rank the nasals among the continuants. /m/ is a bilabial nasal. The mouth is configured just as for the corresponding bilabial stop /p/ and /b/. The lips are pressed tightly together. The air builds up and is suddenly released. /n/ is a dental or alveolar nasal. The mouth is configured just as for the corresponding dental or alveolar stop /t/ and /d/. The tongue makes contact either with the front teeth, or with the alveolar ridge directly above them. /ŋ/ is a velar nasal. The configuration of the mouth is very close to that of the corresponding velar stop /k/ and /g/. With the tongue tip resting against the lower teeth, the back of the tongue makes contact with the soft palate. But as the soft palate is lowered (to allow air to flow through the nasal cavity), the tongue's movement is more important for the nasal than for the oral sound.

An affricate is a plosive immediately followed by a fricative in the same place of articulation. The /ʧ/ in chap /ʧæp/ and the /ʤ/ in jeep /ʤi:p/ are the two clear affricates in English. If you think about it, the /ʧ/ sound is made up from the plosive /t/ and the fricative /ʃ/ sounds. Likewise, the /ʤ/ sound is made up from the plosive /d/ immediately followed by the fricative /z/.

P a g e | 34

CHAPTER SEVENTRADITTIONAL ARTICULATORY PHONETIC

1. INTRODUCTION

P a g e | 35

P a g e | 36

P a g e | 37

P a g e | 38

P a g e | 39

P a g e | 40

P a g e | 41

P a g e | 42

P a g e | 43

P a g e | 44

P a g e | 45

P a g e | 46

P a g e | 47

P a g e | 48

P a g e | 49

P a g e | 50

P a g e | 51

P a g e | 52

P a g e | 53

P a g e | 54

P a g e | 55

CHAPTER EIGHTTYPOLOGY OF VOWELS

P a g e | 56

P a g e | 57

P a g e | 58

REFERENCE

Birjandi, Parviz and Allameh Tabatabaii. 2005. “An Introduction to Phonetics”. Teheran. University of Zanjan

Hussain, Sarmad. 2005. “Phonetic and Phonology an Introduction”. Lahore. Centre for Research in Urdu Processing

Oden, David. 2005. “Introducing Phonology” London. Cambridge University Press

Roach, Peter. 1991. “English Phonetics and Phonology” A Practical Course 2nd . London. Cambridge University Press

Skandera Paul and Peter Burleigh. 2005. “ A Manual of English Phonetics and Phonology. German. Gunter Narr Verlag Tubingen