Differential rent and the role of landed property

-

Upload

michael-ball -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

1

Transcript of Differential rent and the role of landed property

Differential rent and the role of landed property

by Michael Ball

La rente difftrentielle, dans la thtorie marxiste de la rente foncitre capitaliste, est souvent considtrte comme I’appropriation, par les proprittaires, des surprofits result. ant de la production sur les terres les plus fertiles, surprofits difftrentiels dont l’existence serait indkpendante de la ntcessitt du paiement de rente. Dans cette perspective, la rente difftrentielle n’influe pas sur le procts d’accurnulation du capital, ni sur la valeur d’tchange des marchandises.

La thtse dtveloppte ici est que I’analyse de la rente difftrentielle (type 11) dans ZA Capital rnontre que l’existence de cette rente conduit a des effets opposts, et que la conclusion selon laquelle la rente difftrentielle n’est qu’une redistribution de sur- profit prtexistant ne peut dtcouler que d’une probltmatique ricardienne ou margina- liste.

Aprts avoir explicitt les difftrences entre les theories de la rente difftrentielle de Marx et de Ricardo, il est montrt que la thtorie marxiste de la valeur constitue un tltment dtcisif de la constitution de ces differences. De plus, il rtsulte du rapport entre la thtorie marxiste de la valeur et celle de la rente difftrentielle que les effets de cette” cattgorie de rente sont distincts selon qu’il s’agit de l’agriculture ou de l’industrie. Et ceci permet, entre autre, de thtoriser l’impact des localisations sur le procts de produc- tion et sur la valeur des marchandises. Ce qui mtne, au bout du compte, ?I s’interroger sur la pertinence des cattgories rnarxistes de rente, rente difftrentielle comprise, pour l’analyse des mtcanismes crtateurs de rente dans les zones urbaines.

The theory of rent has been the subject of considerable controversy among marxists in recent years. In fact, there is little agreement over basic concepts within the theory, particularly those concerning the categories of rent de- veloped by Marx. Confusion within this body of theory is unfortunate as it makes the analysis of an important political question extremely difficult. This question concerns the role played by landed property in a social formation dominated by the capitalist mode of production.

Much of the controversy has concerned the question of whether rent is simply a residual category in the distribution of surplus value. The treatment of rent as a residual is based on the argument that it only represents surplus profits, the existence ofwhich is not dependent on the rent relation itself. This was’the conclusion of the debate between the classical economists which pro- duced the Ricardian theory of rent, and whose principal features have formed the basis of most subsequent theories of rent. Marxist theorists, on the other hand, have attempted to show that landowners can play a determinant role within capitalist societies by acting as a constraint on the accumulation of capi- tal and by influencing the distribution of land uses. This has been undertaken primarily by recourse to Marx’s concept of absolute rent. There has been

Michael Ball 38 I

much controversy over the usefulness of this category and the contexts in which it is applicable, particularly over whether it has a role in the analysis of urban rent. In contrast, Marx’s concept of differential rent has been treated as essen- tially similar to Ricardian rent : a residual in the distribution of surplus value which presents no major theoretical problems and is of little specific interest.

The purpose of this paper is to suggest that Marx’s analysis of ground rent never posited that absolute rent is the sole restriction placed by rent relations on the process of capitalist accumulation. It will be argued that differential rent also plays this role. This is because Marx’s theory of differential rent is different from that of Ricardo. The difference is not caused by some slight variation between their respective assumptions. Instead, it is the direct result of their treatments of the question of value; an issue which forms one of the fundamental bases of Marx’s critique of political economy. Central to this con- clusion is the influence of rent relations on the law of value. A detailed elabora- tion of this relationship will form a substantial part of what is to follow.

Examinations of ‘what Marx really said’ can be tedious and pedantic, and such examinations should not necessarily be taken at face value. A detailed reading of the original texts is required before any interpretation can be accepted as correct. The question of differential rent, however, does require such an examination because of the prevalence of the view that Marx’s theory was similar to that of Ricardo. Marx produces an analysis which is consistent with the operation of the law of value, obviating contradictions which arise from the Ricardian approach. Marx’s analysis indicates, for example, the way in which the effects of landownership and space should be analysed in the process which generates the exchange values of commodities, without produc- ing the indeterminacies of the Ricardian approach. Consideration of Marx’s theory of differential rent consequently has implications for issues of current concern and it is not just an arid theoretical exercise.

I The analysis of rent

Rent arises from the ability of landowners to appropriate the product of surplus labour; the means by which this will occur will depend on the prevailing rela- tions of production. In a social formation dominated by the capitalist mode of production it will take the form of landed property acquiring part of the surplus value generated by the exploitation of wage labour by capital. The initial definition of rent in this way highlights the nature of rent as the economic form of a social relation. This social relation is the situation of landed property in a social formation, where landed property is defined as the private owner- ship ofland. (This definition thus excludes the ownership of land by the state.) The role of landed property in a social formation extends considerably beyond the collection of rents, and the class situation of the agents of this category of capital can vary even within a social formation dominated by capitalism. For example, an analysis of the class situations oflandowners in modern Britain and the effects they produce (Massey and Catalano, 1978), shows that land-

382

owners cannot simply be treated as an homogeneous block. The theory ofrent consequently can form only an element in the theoretical framework required for consideration of landed property in capitalist societies.

The role ofrent theory has to be delimited even further. In order to examine the underlying structural relationships, theories are based on abstractions. So the applicability of a theory to the relevant concrete situation must be ascer- tained before recourse is made to that theory. This elementary procedure is often ignored. I t has led, for example, to an uncritical application of Marx's categories of rent to urban areas, even though those categories were developed by Marx in an abstract form for non-urban situations. It is necessary therefore tospell out at this stage the simplifying assumptions that will be made. It must be stressed that these assumptions are not required so as to produce an idealist model but in order to examine the structural relations that exist in the payment of rent.' The relation of the analysis to some of the situations which do not have these structural characteristics will be discussed in section IV par- ticularly its applicability to the urban context. Additional assumptions will also be made for expositionary purposes, to clarify the structure of the argument.

As rent relations under capitalism are being considered, it will be assumed that all production is capitalist, including that in agriculture. Further, that direct ownership of the land by the producer does not exist; the use of the land requires payment of rent to a landlord. Strictly this means that no ren't can be zero. Landlords will never rent out land unless they receive some payment in return, as Marx points out in his presentation of absolute rent. But only differential rent is being discussed here, so this difficulty will be ignored. Land is leased to users but to simplify matters the contradictions generated by the fixing of rent at the beginning of the lease will not be con- sidered; rent can be adjusted at any time and the landlord has complete know- ledge of the profits made by the user. Emphasis will be placed on the in- vestment of capital on different plots of land so, to avoid complications, a uni- form plot size will be assumed. It will also be assumed that only one market price for each commodity exists and no imports can occur. Finally, the issue of concern here will be the potential for earning excess profits from producing a commodity at one location as compared to another, and the effect of the intervention of rent relations in an attempt by landlords to appropriate those excess profits. The rent question therefore concerns the production of one com- modity (e.g. corn). In reality, land uses have to compete with each other for the use of land. This fact caused controversy and confusion amongst bourgeois economists during the nineteenth century (see Buchanan, 1g2g), as some felt that land use competition invalidated the Ricardian theory of rent. Obviously, any land use will incur a rent at least as great as any other competing use, as Mam noted (111, 767).2 This does not, however, negate the concept of dif-

O n the distinction between the theoretical method of historical materialism and the idealist notion of model building, see Althusser and Balibar (1970).

*Quotes from Cupitul are denoted by the volume and the page number, and are taken from the English edition by Progress Publishers: Lawrence and Wishart ( ICJ;'~).

Property and rent: a symposium

Michael Ball 383

ferential rent; and it will not concern US here, as the analysis is focused on what causes the excess profits which enable the payment of rent. Competing land uses simply complicate the issue; therefore only one commodity will be ,-onsidered at a time.

The theory of differential rent

This section will distinguish Marx’s and Ricardo’s theories of differential rent. An initial summary of the conclusions will help to highlight the thread of the aTgumen t .

The two theories in the agricultural context produce the same results only ifit is assumed that equal amounts of capital are applied to the different plots ofland in cultivation (i.e. differential rent I). Once unequal amounts of capital can be applied to those lands in cultivation (i.e. once differential rent I1 arises), Marx’s and Ricardo’s theories diverge. Marx continues to operate a rigorous theory ofvalue whereas Ricardo adopts a marginalist procedure of considering each additional investment of capital on an incremental basis, rather than treating the total investment of capital on each plot as a whole. This arises from Ricardo’s inability to break out of the theoretical straitjacket of consider- ing only concrete labour time. He therefore cannot examine values in terms of abstract labour time and as a consequence neither can he theorize the pro- cesses which create the socially necessary labour time for the production of a commodity.

The case of differential rent I will be considered first : that rent which arises from the application of equal amounts of capital to lands of varying fertility. With differential rent I, the exchange value of the agricultural commodity will be determined by the price of production on the worst The average cost of producing a unit of the commodity will be less on more fertile soils (in Marx’s terms, the individual price of production will be less). Farmers cultivating these more fertile soils will be able to sell their produce at the higher price prevailing in the market and they will make excess profits. But the owner- ship of the land by a landlord results in these excess profits accruing to the landlord as rent.

The effects caused by differential rent I were however not the same for Marx as those suggested by the classical economists. The latter had terided to assume that the progression of land brought into productive use would be from the most fertile to less fertile soils, which would imply a continuing rise over time of the price of the commodity. Marx argued that the introduction of progres- sively worse soils need not be the actual sequence of cultivation; therefore corn prices need not necessarily rise because of the expansion of production onto new lands. The criticism of the Ricardian assumption of a movement towards

8 ‘Worst’ simply means that soil in use which has the highest price of production, either because of its fertility or location. For simplicity, differences caused by fertility will be used to illustrate the argument.

384 Property and rent: a symposium

worse soils is essentially a point of logic, such a progression is not needed for the development of differential rent I ; the only necessary precondition is in- equality in the ‘fertility’ of different lands. I t is therefore not a fundamental criticism of the Ricardian theory of rent but a critique only of one of the sup- posed implications of that theory: the continual rise in the price of agricultural commodities. This criticism of the Ricardian ‘law of diminishing returns’ has however been seen by many marxists as the main factor distinguishing Marx’s analysis ofdifferential rent from that of Ricardo (cf. Lenin’s (191 3) comments in his essay Karl Marx) .

When the restriction that only equal amounts of capital can be invested on lands in cultivation is removed, the potential for differential rent I1 will exist. I t will now be shown how the introduction of differential rent I1 causes a divergence between the theories of rent of Marx and Ricardo. Marx continues tooperateaconsistent value theory : additional investments of capital on the same plot of land increase the total capital invested and total output. And, paraphrasing Marx, it is not possible to distinguish which part of the total output is a product of the initial capital invested and which part is a product ofthe subsequent investment, for all is grown upon the same soil (111, 728). In other words, the price of production per bushel must always be the current average price of production from that plot of land (cf. 111, 7 2 7 ) . Ricardo, on the other hand, treats separately each additional investment of capital and each addition to output generated by it. This is a marginalist pro- cedure which, once the discrete nature of capital investment is assumed away, reduces to the marginalproduct of each additional unit of capital so dear to neo- classical economics (cf. Blaug’s (1968) description of Ricardo’s theory of rent).

A simple numerical example will illustrate the immediate consequences of the two approaches. This is given in Table I . Assume only two plots of land are in production and that initially both have the same amount of capital applied to them. The output required for some reason increases by 40 bushels and this is met by an additional investment of a thousand on plot B. In keeping with the Ricardian expectation, diminishing productivity will be assumed to exist, so the additional investment on B only produced an extra 40 bushels whereas the first produced 50. The methods of Marx and Ricardo lead to very different conclusions as to the new market price and the new level of rents.

In Table I Marx’s terminology has been used with regard to the column headings. For Ricardo, investment on B has to be separated into two parts: the initial one, B,, and the new, B,. B, becomes the regulator of market price, for according to Ricardo: ‘The value of corn is regulated by the quantity of labour bestowed on its production on that quality of land, or with thatportion of capital, which pays no rent’ (edn I 95 I , 74, my emphasis). In the example here the Ricardian separation of the two capital investments on land B makes B, ‘that portion of capital, which pays no rent’; raising the market price above that produced by Marx’s averaging procedure. The effect on market prices of Ricardo’s treatment of additional investments of capital is not immediately apparent in his treatment ofthe issue, as he tended to argue in terms of physical

Michael Ball 385

output, ‘corn’ rents (e.g. his treatment of the matter in his Principles, edn 1951, 71-2).

This distinction between the consideration of marginal additions to capital and output and the averaging procedure of Marx might appear to be solely formal: they produce different results, but why choose one or the other? Marx’s use of the averaging procedure comes, however, from his understand- ing of the dynamic of capitalist accumulation; consequently it is a theoretical result of the problematic of historical materialism. Capitalist accumulation takes the form ofa continual change in production techniques as capitals strive to gain temporary advantages over competitors, who in turn have to adopt the new techniques to survive. This process of accumulation both aids the re- duction of concrete to abstract labour (see Kay, 1976) and determines the mechanism through which exchange values are derived, namely, the socially necessary abstract labour time ; i.e. the social average. Capitalist farmers are not exempt from this process, which is why Marx analyses the average price of production on each plot of land. (There are however differences between the agricultural and the non-agricultural cases, as will be shown later.)

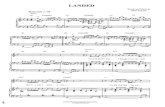

Table I -~ -

Price of Total price Output production Selling

of production (bushels) (per bushel) price -~ - _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ ~ _ _ ~

1 Initial situation A 1000 100 10 20 €3 1000 50 20 20

2 Increased investment on 8. according to Marx

A 1000 100 10 22.2 B 2000 90 22.2 22.2

3 Increased investment on B. according to Ricardo

A 1000 100 10 2 5 1000 50 20 2 5

B2 1000 40 2 5 25 @,

Proceeds Rent

2000 1000 1000 -

2222 1222 2000 -

2500 1500 1250 250 1000 -

The example in Table I assumed the existence of diminishing productivity; it is obvious however that this is not necmsary for the difference between the approaches of Marx and Ricardo, which is based on distinction between averages and margins. If the second investment on B leads to a more than portionate increase in output (i.e. the case of increasing productivity), the two approaches would still have produced different market prices and rent levels. Nevertheless, a number of subsequent illustrative examples will assume that

386 Property and rent: a symposium

diminishing productivity prevails, as this case illustrates the argument most forcibly. However, the implications of increasing productivity are considered towards the end of the next section, where it is shown that such production conditions do not alter the main conclusions of the argument. To avoid con- fusion in this discussion ofvarying productivities, it is worth noting that Marx’s use of the phrase ‘capitals of varying productivity’ should not be interpreted as implying that capital is itself productive; only the labour-power pur- chased by that capital is productive.

Ill

Having highlighted the major differences between Marx’s and Ricardo’s analyses of differential rent, some of the implications of marxist rent theory for agriculture and for manufacturing industry can now be examined. T h e central questions will concern rent and the determination of the exchange value of a commodity.

The role of the value system in situations where rent relations exist has never been analysed in any great detail. Marx did not make its role explicit in his discussion ofdifferential rent ; a careful reading of the sections on rent in Capital is required in order to draw out the theoretical relationships that are implied. An analysis of the law ofvalue in such situations is necessary in order to develop an understanding of the role of landed property. This will show that rent rela- tions do alter the operation of the law of value because of the intervention within these relations of production of the private ownership of land. It will also show that within the mamist system the existence of differential rent can affect prices by restricting the investment ofcapital. The absence of an analysis of the relationship between the law of value and rent relations has thus been the major factor in the development of erroneous views concerning differential rent.

Marx’s ability to theorize the processes which create the socially necessary labour time for the production of a commodity enables him to distinguish between the effects of differential rent in agriculture and in industry. Marx’s theory of differential rent in the agricultural case is one in which exchange value is determined by a marginal process. In the last section it was shown that the capital required to produce a unit of the commodity on the soil with the highest price of production determines the exchange value of the agricul- tural commodity. The particular type of land that plays this marginal role is determined by the relation between the aggregate quantity required on the market and the output produced on other lands in cultivation. Prices of pro- duction represent the average for each plot of land, with each having its own ‘individual average price of production’.

This mechanism is very different from the one by which the values of com- modities are determined in the industrial sector. Here Mam uses the concept ofthe normal conditions of production to derive values. To quote : ‘The labour time socially necessary is that required to produce an article under the normal

Differential rent in agriculture and manufacturing industry

Michael Ball 387

conditions of production, and with the average degree of skill and intensity prevalent a t the time’ (I , 39). This is not an arbitrary procedure but one which is based on the dynamic of capitalist production. As a result not all current production methods used to produce a commodity enter into the determina- tion of the socially necessary labour time. Only those techniques are included which are dominant (i.e. strictly socially necessary) within the particular in- dustry (cf. Marx’s statements on the value of cloth produced by hand-loom weavers when the use of power-looms dominates that industry (I, 39)).

The concept of normal conditions of production is therefore crucial in the determination ofvalues in the industrial sector. I t highlights the fact that the value of a commodity produced in this sector is not determined by a crude, mechanistic averaging of labour times over all production processes currently in use for the production of a commodity. Not all methods of production will enter into the determination of value. For example, at a particular point in time, one method of production may dominate an industry producing a spe- cific commodity. That method will consequently represent the normal condi- tions of production and the socially necessary labour time required by it will determine that commodity’s exchange value. If a new method of production is then introduced by some producers, which requires less labour time than the previous method, it is unlikely that this new process will immediately domi- nate production in that industry. Instead it is possible that, for a time, the normal conditions of production will still be represented by the old method of production. Producers using the new method will therefore be able initially to sell their output a t a value determined by the old process and they will make surplus profits. As they expand output, however, they will come increas- ingly into competition with the older method and will have to lower their selling price to below that of the producers using the older technique. This reduction in the value of the commodity will continue until the new method constitutes the normal conditions of production. Producers using the old method will either have to adopt the more efficient technique or be forced out of production by lower-cost competition. Initially, therefore, the old method of production determines values and, finally, the new method plays that role. During the intervening period neither of the two is the normal condi- tion of production, and the exchange value of the commodity represents an intermediate point between the labour time required by each of them.

There is consequently a dynamic process of adjustment of the values of com- modities produced in manufacturing industry. This process of adjustment is dependent on the normal conditions of production and the development of more efficient processes than that norm. This mechanism by which exchange values are determined for commodities in the manufacturing sector highlights an important difference between industry and agriculture. Even though the mechanism described for industry does not represent a strict arithmetical average, the process of determining values by use of the concept of a ‘norm’ (i.e. normal conditions of production) is, broadly, an averaging procedure; whereas, as we have seen, exchange values in the case of agriculture are deter-

388 Property and rent: a symposium

mined at the margin of cultivation. The reasons for this distinction need to be examined, firstly by looking at rent generated in the production of industrial commodities.

Landowners can extract rent from industrial capital as the latter can benefit from the increased productivity resulting from locating on particularly advan- tageous sites; the use ofwater power which avoids the need to expand capital generating power from stream is the example given by Marx. The existence of differential rent nevertheless does not alter in manufacturing industry the process determining the value of a commodity.

It has already been argued that, even in the absence of rent, the concept ofsocially necessary labour time does not imply that a commodity is produced by capitalists who operate exactly the same techniques at the same level of efficiency : those using more advanced techniques will earn excess profits, These profits will however be gained at the expense of capitalists operating less efficient methods, as competition will force the price of the commodity down towards its price of production under the most efficient technique. This will mean that all capitalists have to use the most advanced methods for pro- ducing the commodity to survive. There is consequently a continuing process by which the variation in actual labour inputs into a commodity is narrowed towards that of the most efficient technique, and the variation of actual labour times around the socially necessary labour time is limited.

This process cannot occur when the increased productivity is conferred by locating at a particular site. At a given level of technology, capital in general cannot overcome production advantages that are peculiar to a specific plot of land and consequently excess profits gained on this land can be extracted by a landlord. Differences between locations create variations in the actual labour inputs required to produce a commodity even for industrial capital. But these variations in productivity between different locations do not lead Marx to conclude that the value of industrial commodities should be derived by the same process that is adopted for the exchange value of agricultural commodities: namely that exchange value is determined by the price of pro- duction on the marginal site in operation. Instead he still uses a procedure for industrial commodities which makes value equivalent to the average labour time expended. If production on more advantageous sites is such that it domi- nates production of that commodity, producing on those sites will be the normal conditions of production. Value consequently will be determined by the abstract labour time required for production at these locations and against which all production at other locations must compete. On the other hand, if production on more advantageous sites represents only a relatively small part of the industry, it will not represent the normal conditions of production. Production on these sites will therefore generate excess profits, as the labour time required on them will be lower than the socially necessary labour time, and the owners of such lands will be able to acquire those excess profits as rent (111,647). Capital will however try continually to overcome the produc- tivity gains conferred by particular sites by altering the process of production.

Michael Ball 389

The same mechanism which drives capital to adopt techniques which improve labour productivity will induce capital to negate the production advantages of particular sites. Capitalists who succeed in doing so will be able to earn above-average profits by stealing a march on their competitors who, in turn, will have to respond by altering their production processes in order to maintain their profit levels. The ability to overcome such locational advantages will, of course, vary from industry to industry depending on the characteristics of the particular production processes used, the degree of technological change, and the specific nature of the locational advantage.

Nevertheless, the nature of locational advantages can be delimited. First, they can be considered only in terms of specific time periods, when a particular process of production is the norm. Like capitalism itself, they are therefore limited in time, and are not a historical entities. In addition, their effects within any industry at a given point in time can be analysed only in comparison with other locations and with other contemporary production methods in that in- dustry; two factors which themselves will be interrelated. consequently, exchange value cannot be assumed a priori to be independent of the existence of these more favourable locations. For exchange value is dependent on the labour time required under normal conditions of production, so the relation of production at more advantageous sites to the normal conditions of produc- tion will be crucial in the determination of the magnitude of exchange value. Locational advantages are just one of a series of possible production advantages that an individual capitalist can enjoy. Thus in this context they must be con- sidered in the same way as other production advantages: in relation to the overall structure of the industry producing the commodity.

Only by looking at the overall structure of the industry can the relationship between production at the more advantageous sites and the normal conditions of production in the industry be derived. And only in this way can it be deduced whether these locations will generate excess profits, which can be appropriated as rent, or whether they will become the normal conditions of production. In the latter situation, production at other locations will result in either below-average profits or bankruptcy, instead of excess profits at the more favourable location.

Marxist value analysis thus enables the consideration of the spatial dimen- sion in the analysis of production in manufacturing industry, without at the same time generating insurmountable theoretical inconsistencies. As Massey (1974) has shown, this is something that neoclassical economics has never been able to achieve in its attempt to incorporate the existence of space within the framework of its aspatial theoretical analysis.

The relationship between the theory of differential rent and the theory of value, therefore, has a twofold nature. For industrial commodities the only influence on value of the variation in productivities between production at different locations is through its effect on the average amount of labour time expended; whereas for agricultural commodities, and given raw materials, exchange value is determined on the marginal land in operation. This separa-

390 Property and rent: a symposium

tion could relate to an implicit consideration of the relative importance of such differences in productivity for these sectors, their importance for industrial capital being comparatively low. But such a distinction, which would be based on empirical grounds, does not constitute a theoretical answer and cannot be considered adequate. A theoretical discussion of the industrial case has already been presented ; now the agricultural case needs to be considered further.

When analysing differential rent I, some mechanism must exist which ensures that the price ofproduction on the ‘worst’ soil is the one that determines market price. This is done by assuming that capitalist farmers compete with each other and that they are prepared to continue investing in production as long as they receive the average rate of profit. I t is also assumed that the market price will be directly responsive to changes in supply, rising when there is a shortage and falling when there is a glut. If, for example, the demand for corn rises, the market price will rise making it profitable to bring additional land with a higher priceofproduction into cultivation. The price will continue to rise until there is a sufficient increase in production to meet the shortfall in supply.* All this is obvious, but it highlights an important assumption implicit in most of Marx’s discussion of differential rent 11, namely that the overall price of production for the agricultural commodity is determined by the ‘worst’ soil on which the ‘normal’ amount of capital is invested (111, 706), even though lands are being cultivated which have lower prices of production. This assumption, as we shall now see, implies that some mechanism is operat- ing which inhibits the competitive movement of capital in agriculture.

In the previous section it was shown that, in Marx’s terms, the average price of production of each soil is the crucial factor in determining the level and pattern of differential rent. Investment by capitalist farmers is influenced, therefore, by the relative magnitude of the average prices of production of each soil; thus the existence of surplus profits should result in additional in- vestment of capital. If the price of production (which includes the average rate of profit) on the worst soil determines the market price, and farmers are prepared to invest additional capital in cultivation as long as they receive the average rate ofreturn, farmers with soils which have lower prices of production than the market price will continue investing on those lands until their prices of production have reached, or become, the market price, as the total capital invested on each soil type still yields the average rate of profit.

The fact that farmers are influenced only by the average price of production of each soil produces an interesting result. If there was a free movement of capital in agriculture, the drive for accumulation by capitalist farmers would result in additional capital being invested in each soil type until prices of pro- duction had been equalized across all lands under cultivation. As there would then be no differences between the prices of production of each soil type, there

4 If account is taken of Marx’s criticism of the view that increases in supply are only obtained by moving onto less fertile land, such increases in the demand for corn nerd not always be met by introducing land with a higher price of production. If lands with higher prices of production are not required, the market price need not rise.

Michael Ball 39 I

would be no surplus profit which could be extracted by a landlord, and there- fore no differential rent would be paid.

Marginalists and the classical economists would not reach this conclusion as they assume that the farmer invests only up to the point where the last unit of capital produces the average rate of profit. In terms of the example given in Table I , the additional investment of 1000 on B would produce for Ricardo a situation where no additional investment could take place. The amount of capital, B,, only received the average rate of profit so subsequent investments would produce below-average returns. In Marx’s analysis, how- ever, additional investment on B could continue, in the absence of rent, because a substantial surplus profit is still made on the total capital invested on B after the additional investment of 1000. It should be noted that in this discussion changes in the amount of the commodity produced have been assumed not to affect the market price. More realistically the increased supply would reduce the area under cultivation and therefore lower the market price.

The existence of landed property acts as a barrier to this equalization of individual prices of production. Once rent has been paid on the lands with the lower prices of production, there is no reason why the landlord should acquiesce to a loss of rent which must ensue if the farmer were to increase output by additional investment of capital at the expense of rent. The landlord will demand the same level of rent, but the additional investment of capital by the farmer up to the point where ‘average individual prices of production’ are equal across all lands in cultivation will remove all the surplus profit that can be appropriated as rent, so additional investment is restricted by the need to pay rent. This means, however, that landed property has acted as a barrier to the investment of capital. This necessitates the earlier introduction of more land and higher market prices. In other words, once the possibility of investing varying quantities of capital on different lands is introduced into the analysis. Marx’s theory of differential rent shows that rent affects prices, and restricts the accumulation of capital.

Marx summarizes the argument thus :

Thus although differential rent is but a formal transformation of surplus profit into rent, and property in land merely enables the owner in this case to transfer the surplus-profit of the farmer to himself, we find nevertheless that successive investment of capital in the same land, or, what amounts to the same thing, the increase in capital invested in the same land, reaches its limit far more rapidly when the rate of productiveness of the capital decreases and the regulating price remains the same; in fact a more or less artificial barrier is reached as a con- sequence of the mere formal transformation of surplus-profit into ground rent, which is the result of landed property. The rise in the general price of production, which becomes necessary here within more narrow limits than otherwise, is in this case not merely the cause of the increase in differential rent, but the existence of differential rent as rent is a t the same time the reason for the earlier and more rapid rise in the general price of production-in order to ensure thereby the in- creased supply of produce that has become necessary. (111, 737)

392 Property and rent: a symposium

So far one result of the rent relation has been shown: it stops individual prices of production from being equalized in agriculture. Rent relations create the very conditions which enable the appropriation of rent : surplus profits on intra-marginal lands. The effects are, however, even more pervasive. This can be seen by looking at two of the tables on differential rent I1 revised by Engels in Capital.

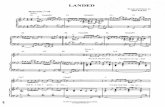

Table 2 shows the initial situation of equal quantities of capital applied to five different soil types yielding differential rent I on all but the worst soil. Table 3 shows the situation after additional capital with lower productivity has been invested in the intra-marginal soils. The market price is still assumed to be determined by the worst soil, A. ‘Price of production’ in these tables

Table 2

Price of Price of Type of production Output production Selling price Proceeds Rent

soil (shillings) (bushels) per bushel (shillings) (shillings) (shillings)

A 60 10 6 6 60 0 B 60 12 5 6 72 1 2 C 60 1 4 4 28 6 84 24 D 60 16 3 75 6 96 36 E 60 18 3 33 6 108 48

_ _ ~ -.

(Taken from Table XI, Ill. 717)

refers to the total capital engaged on each soil, plus the average mass of profit on capital. A column showing price of production per unit of output has been added; this is the price of production to which Marx refers in his text.5

It can be seen that the price of production per bushel on all the soils B to E has increased as a result of the additional investment. The effect on the total rent paid on each soil type has varied, soils C to E will pay increased rents but soil B now pays less: 6 shillings instead of 1 2 . Given the property relations in existence, a landowner leasing land to a tenant capitalist farmer, this reduction in rent on the B soil could not occur. The farmer renting B would have leased the land in the initial situation for I 2 shillings; he is still contracted to pay that rent when the additional investment is considered. As it reduces the surplus profit on that soil the investment will not take place. The new investment must at least create a rent equal to that previously charged; thus the initial rent has acted as a barrier to investment.

Let us assume that the additional investment on lands C to E did take place but not that on B. The market price will be determined by the worst soil; lands A and B will be in the position described by Table I and C, D and E

These tables are being used here to illustrate a specific point and they should not be treated as the actual progression of agricultural investment.

Michael Ball 393

as in Table 2 . If the market demand rises to a level above the new aggregate supply and the additional investment on B represents the cheapest way ofmeet- ing this increase, the market price will have to rise. The investment on B will only take place if total proceeds equal I 32 s, the sum of total price of produc- tion, I 20, and the rent of I 2 . The market price will therefore have to rise to 6.29s. This will increase the excess profits on the other soils, including the previous no-rent land, which will now pay a rent of 2.9s. The existence of differential rent has once again increased market price and all lands in cultiva- tion pay rent. This was the procedure used by Engels in his recalculation of Marx’s table on rent on the worst soil (111, 740).

Marx’s treatment, in Capital, chapter XLIV, ofdifferential rent on the worst soil presents certain difficulties as, contrary to the rest of his analysis of differen- tial rent, he initially adopts Ricardo’s marginalist approach. Engels corrects

Table 3

Price of Price of Type of production Output production Selling price Proceeds Rent

soil (shillings) (bushels) per bushel (shillings) (shillings) (shillings)

A 60 10 6 6 60 0 B 60+60=120 12+9=21 5 71 6 126 6 C 60+60=120 14+105=245 4 9 0 6 147 27 D 60+60=120 16+12=28 4 2 8 6 168 48 E 60+60=120 18+135=31 5 3 8 1 6 189 69

(Taken from Table XIV, 1 1 1 , 718)

this error in an editorial comment in the manner just described. I t is worth, however, examining this issue in greater detail. The example in Table I

showed the difference between Marx’s treatment of the average price of pro- duction of each soil and Ricardo’s emphasis on the increments of capital in- vested. The Ricardian approach to the additional investment on soil B made the productivity of the second application of capital determine the market price. This led to the generation of differential rent on B, where none had existed before, because the initial investment on that land now produced a rent of250. Marx adopted this argument of Ricardo’s in his presentation of differential rent on the worst soil, whereas the correct marxist method would not have produced this result. Table I shows that using the average price of production for soil B produces no differential rent on B when the additional thousand is invested. Marx seems to have been aware of his error for he points it out on the page following his erroneous argument, with this statement:

But from the point of view of differential rent, a peculiar difficulty arises here owing to the previously developed law-according to which it is always the individual average price of production per quarter for the total production (or the total outlay of capital) which acts as the determining factor. (111, 741)

394 Property and rent: a symposium

However, he does not go back and correct this error.6 Differential rent on the worst soil can still occur within a correct marxist

analysis of rent. It arises, however, from the intervention of landed property through the rent relation, and not from the existence ofpricing based on margi- nal products. How this occurs has already been presented in the discussion of the numerical example given in Tables 2 and 3, and it is given by Engels in his reformulation of Marx’s example of differential rent on the worst soil (111, 740). The fact that it is caused by the intervention of landed property might lead to the supposition that such rent on the worst soil is simply another version of absolute rent. But Marx gave a rigorous definition of absolute rent, one of the necessary conditions for whose existence was the demand for a posi- tive rent on all lands in cultivation, even when they would otherwise generate no excess profit which could be appropriate as rent. This is not the situation being considered here ; therefore it cannot be considered as absolute rent.

At this point it should be considered whether the conclusions reached about the role of differential rent are dependent on the existence of a diminishing productivity of additional investments of capital. The main point that has been made with regard to differential rent in agriculture is that, in the absence of this form of rent, prices of production would have a tendency to be equalized across all lands used in the production of a particular agricultural commodity. With diminishing productivity and no payment of differential rent, capitalist farmers using intra-marginal lands will continue to invest additional capital until the price of production of those lands rises to equal that of the marginal land in production. It is not necessary, however, to have diminishing pro- ductivity for this tendency for prices of production to be equalized. This equalization would still take place no matter what the particular combinations of productivity. This is true even in the extreme case of all the lands enabling increasing returns from additional applications of capital. If all lands did, in fact, generate increasing productivity, those with the lowest price of production would compete with the other lands until they were the only ones left producing the commodity. Then their price of production would deter- mine market price, and no surplus profits on intra-marginal lands would remain to be appropriated as differential rent. In other words, for differential rent to exist some barrier to the accumulation of capital in agriculture must also exist.

Now that these elements in Marx’s theory of rent have been elaborated, the differences between industry and agriculture over the role of differential rent and the determination of exchange values can be examined. In looking at the industrial sector emphasis was placed on the importance of the concept of normal conditions of production in determining the value of an industrial commodity. It was shown that there is a tendency driving production in in- dustry towards the most efficient technique, which would then become the

It should nevertheless be remembered that Volume I11 of Capital consists only of draft notebooks which were not revised by Marx for publication. Instead Engels published them after Marx’s death.

Michael Ball 395

normal means of production. The mechanism which moves processes of pro- duction towards a norm in the industrial context is permanently fettered in agriculture by the need to pay rent. The inequality in the prices of production on different lands is perpetuated by the existence of the rent relation. Thus, there can be only a restricted covergence towards such a norm in agriculture. The rent relation in effect places an artificial restriction on output from the more productive soils. Market value will, therefore, be determined by produc- tion under the least favourable conditions: by the land with the highest price of production. ‘This is determination by market value as it asserts itself on the basis of capitalist production through competition; [in the agricultural case] the latter creates a false social value. This arises from the law of market value, to which the products of the soil are subject’ (111, 661, my emphasis). With the existence of private landed property, agricultural production could only avoid this restriction on investment by breaking its link with the land.’

We now have two opposing adjustment processes : more productive locations only affect the average labour time required to produce a commodity in the industrial sector whereas price is determined on the marginal land in agri- culture.s Industrial capitalists attempt to adopt the lowest-cost technique, but in agriculture capitalist investment is made until the price of production equals that of the highest price of production land in cultivation. This apparent con- tradiction results primarily from the fact that two different effects are being compared. Additional capital can be employed to overcome competition which arises from lower-cost techniques which have, in turn, been created solely from the application of capital, whereas the same cannot take place when the increased productivity arises as a result of different productivities of land. I t is possible, however, to argue that industrial capitalists with advantageous sites would also continue to invest until their price of production was equal to the industrial average, in the absence of differential rent. If they could do this, the aggregate output of the sector would rise, competition would force high-cost producers out of production, and the average price of production would be less. So that although the adjustment process of industrial and agricultural producers located on better lands would be different in the absence of rent, the effect of rent on prices still occurs in both cases. I t is the existence of rent itselfwhich gives rise to different effects in the industrial and agricultural cases. In the absence of rent, both sectors would tend towards asituation with each capitalist facing an individual average price of production

’ It should be noted that the argument about the role of rent in agriculture has shown only that rent acts as a restriction on investment. This conclusion is compatible with substantial actual investment in agriculture and increases in agricultural labour pro- ductivity.

* This highlights another distinction between Marx and Ricardo. As Ricardo could not theorize the different mechanisms that determine market values in the agricultural and industrial contexts, he was forced to conclude that all values (including those in manufacturing industry) were determined by labour required in the least efficient pro- duction process in operation (see his Principles, edn I 95 I , 73).

396

which equalled the sectoral average, and the difference between marpins and averages of the type described would be of no concern.

Property and rent: a symposium

IV

The conclusion of the previous section was that the rent relation creates the very existence of surplus profits appropriated as rent. The opposite conclusion has been adopted, however, by most marxists as the correct position on dif- ferential rent. Differential rent is treated as a product of the capitalist mode of production as such, not of the intervention of private landownership within that mode of production. Rent in this latter formulation is therefore simply a distributional result in the sphere of exchange; an appropriation of surplus value which has no consequences for the sphere of production. Lenin takes this position, for example, in a brief exposition of Marx’s work in his essay Karl Marx (191 3). Kautsky in The agrarian question adopts a similar line: ‘To summarize, differential rent results from the capitalist character of production, not from the private ownership of land’ (see Banaji, I 976, 2 I ). Marx himself is not consistent in this matter; for much ofhis analysis he also adopts this latter position. For example, in the chapter on absolute rent in Capital he states that: ‘Differential rent has the peculiarity that landed property here merely intcr- cepts the surplus-profit which would otherwise flow into the pocket of the farmer . . .’ (111, 755); and he goes on to state that landed property is not the cause of this surplus profit. He reaches the same conclusion in his letter to Engels, z August I 862 (Marx: Engels Selected correspondence, I 24). Recent writers on the question of rent have also taken this position. Cutler and Taylor (1972) have argued that differential rent is a necessary relation of distribution under capitalism, representing the excess profits which they say must arise on more fertile lands. Similarly, both Edel ( I 976) and Lipietz (1974) argue that differential rent does not affect prices. The latter even attempts to demon- strate Marx’s theory by the use of the first derivative of a neoclassical produc- tion function. He does suggest, however, that there is a small difference between the two problematics concerning a divergence over the ‘behaviorial hypotheses’ [sic] used in determining which profit is maximized (the farmer’s or the general rate of profit). Elsewhere, Edel (1974) and Cutler (1975) have suggested that Marx’s theory is essentially the same as Ricardo’s. Of course, non-marxist commentators have been even more convinced of the similarity of Marx’s and Ricardo’s theories of differential rent ; for example, see Blaug (1968) and Scott (1976).

In a static sense, when the amount ofcapital invested on each land is given, the argument on rent presented in section I11 produces a conclusion similar to those of the writers mentioned above. Prices of production for different lands, in this static case, will not be equal; excess profits will exist, which can be appropriated as rent. Thus, at any point in time, rent will appear solely as an appropriation of excess profits, and these profits will also appear to exist before the demand for rent. But a cause cannot be deduced simply from the

Does differential rent create its own conditions of existence?

Michael Ball 397

realm ofappearance; and it has been argued in this paper that once the process of capitalist accumulation is considered, the apparent independence of excess profits from the rent relation is no longer tenable. The position which suggests the two are independent rests, therefore, on a neglect of the dynamic of capital- ist accumulation. In a dynamic context additional investment can take place, and rent will act as a limitation on additional investment if the latter encroaches upon the demand for rent.

This conclusion is only true, however, if Marx’s procedure is adopted, of using individual average prices of production. Rejection of this procedure, not surprisingly, leads to a rejection of its conclusions. So once the possibility of further investment of capital on each land is accepted, the difference between the position which argues that rent relations sustain the surplus profits neces- sary for the existence of differential rent, and the one that says they do not, rests, in a formal sense, on the adoption of either averaging or marginal pro- cedures. The first position is the logical conclusion of an analysis based on a consideration of averages for each plot and the second is produced from an analysis which looks at the marginal results of each separate investment of capital on any particular land. In the second approach additional investment will cease, irrespective ofthe demand for rent, once the marginal unit of capital earns only the average rate of profit; even if intra-marginal investments on the same land are generating above-average profits. If averages are used, how- ever, the perpetuation of such excess profits will take place only when rent is demanded.

It has been argued in earlier sections that a consistent theory of value demands the adoption of the average price of production for each land, and that this is more accurate than the marginalist procedure. It has also been shown that Marx regarded the individual average price of production as a fundamental basis of his theory of rent. Nevertheless the conclusions about dif- ferential rent presented here might seem controversial. However, marxists who wish to use the Ricardian approach have to demonstrate the correctness of a number of factors. First it has to be shown why the marginalist approach should be used when considering rent, and this has to be shown for all sectors where differential rent arises: in manufacturing industry as well as in agri- culture. Second, how the use of marginalism when examining rent relations does not conflict with the operation of the law of value in other situations, where the values of the same commodities are based on distinctly non-mar- ginalist concepts. And, finally, why Marx was wrong in his approach to dif- ferential rent.

The role of differential rent in the value system and its effects on prices of production was not emphasized by Marx. He never points out that his treatment of the investment of additional capital on the same land was different from that ofRicardo. Instead Marx’s criticisms of Ricardo were centred on the ‘law of diminishing returns’ and Ricardo’s inability to theorize the possibility of absolute rent. In this context, given the almost universal acceptance of the Ricardian theory of rent and its apparent similarity to that of Ma=,

398 Property and rent: a symposium

it is not surprising that most marxists have accepted that Marx’s theory is just a logically sounder version of the Ricardian doctrine. But why did Marx not give greater emphasis to the differences between his theory and Ricardo’s? Especially as by the end of the chapter on absolute rent in Capital, the impres- sion is given that absolute rent is not of major importance for capitalism.9 No adequate explanation of this omission can be given.

The incomplete nature of Volume 111 of Capital is well known, and much of the section on differential rent is in note form, particularly the last two chapters (chapters 43 and 44) where the implications for accumulation and prices of this category of rent are examined. The Theories of surplus value was written before Capital, Volume 111, and there is a more rigorous treatment of differential rent in the latter work. There is a distinct impression that Marx had developed his ideas on rent between writing these two works. For instance, Marx did not feel it necessary to examine the two types of differential rent separately in Theories of surplus value. Additional investment of capital receives scant treatment there, with the detailed analysis of differential rent I1 only appearing in Capital. Yet it is the latter which distinguishes Marx from Ricardo on differential rent. References can be found in Theories which imply tacit approval of Ricardo’s marginalist treatment of additional capital, even though Marx himselfused the averaging procedure (e.g. Volume 11, p. 332), but such comments cannot be found in Capital. Reference has already been made to Mam’s confusion over differential rent on the worst soil, where he presents a Ricardian exposition but subsequently realizes his error. Finally, Engels points out in the preface to Capital, Volume 111, that in the original sequence ofwritings for the part on ground rent in the third volume of Capital.the section on differential rent had been put at the end, after that on absolute rent. Engels later changed the order before publication on the basis of Marx’s suggested headingsfound in the manuscript (111, 726). These factors could account both for the relative incompleteness of the differential rent section and for its lack of integration with the rest of Marx’s argument on rent.

9There is an interesting decline in the emphasis given to absolute rent in Capital as compared to Theories of surplus value, where it played a prominent role. By the time he wrote the chapter on it in Capital, Marx seems to have developed a more rigorous analysis of the conditions for its existence, in which two conditions are necessary, but are not sufficient (the demand for rent on otherwise no-rent land and a low organic composition of capital in agriculture). Also, absolute rent is no longer quantified, nor is mention made of the situation where it allows negative differential rent on which emphasis was placed in Theories of surplus value. In addition Marx was at pains to point out in Capital the transient, historically specific nature of absolute rent, even within the capitalist mode of production. The conditions under which it would cease to exist were carefully spelt out. These criteria are particularly restrictive and lead to the em- pirical conclusion reached by Marx that absolute rent where it exists a t all can only be small (111, 7 7 1 ) .

Michael Ball 399

v Implications and applications

m e examination of the theory of differential rent is now complete. To con- clude, some implications of theory will be discussed, including an examination ,,fthe effects of the abstractions outlined in section I . Space constraints will limit consideration to a few matters only.

Differential rent plays a greater role in capitalism than is sometimes sug- gated. This is particularly true for the agricultural sector where it has been shown that exchange values, and therefore prices, are higher as a result of the demand for differential rent. Differential rent creates this situation because it retards the investment of capital in agriculture. What seems to be solely a distributional relation in the sphere of exchange thereby restricts the develop- ment ofthe forces ofproduction. Rent relations do not only appropriate surplus value; they also raise the value of agricultural commodities, thus raising the value of labour-power and reducing the rate of surplus value in non-agricul- tural sectors as well.

The possibility of imports has been ignored in the analysis. There is no mason, however, to expect that the fundamental conclusions would be much altered by their existence. If imports dominate the market for a particular agricultural commodity, for example (and there is no necessary reason why they should), market price will be determined by the price of imports rather than the ‘worst’ soil. But the process of accumulation in agriculture will not be altered so the effect of rent on accumulation will still take place. Moreover, with the existence of imports the effect of rent on the value of agricultural commodities could now be transmitted from one nation-state to another.

The price of land: I t is useful to consider the extent to which the conclusions on differential rent are altered by the direct ownership of land by the control- lers of production, for example, the capitalist farmers. Property rights are transferable and therefore landownership can command a price, which will be determined by two factors : the rental stream expected to accrue from the land and the rate of interest at which that flow of rents is capitalized.

The simplest way to bring out the effects of ownership is to assume that a producer has just purchased a plot of land. As the purchase price of land is based on the rental flow, the main effects of rent will still be operative. Thus the mere transference of ownership has not substantively altered the role of rent. This statement, however, must be qualified because of potential changes in the level of rent. Because the price of land is based on the expected rental flow, the circumstances which determined this flow could change and with it the prospective flow of rents. The outlay made by the capitalist to purchase the land will no longer correspond to the rental flow, therefore the barrier tb the investment of productive capital on the land could be lowered.

Urban rent: Finally, the issue arises of whether the previous discussion can be transposed into an urban context. Much of the recent debate about Marx’s

400

theory ofrent has been concerned with urban areas and much has simply trans- ferred the agricultural case into an urban situation.1° But the ability to make a direct transfcr is questionable, particularly if the attempt generates a fruitless search for differences in productivity across urban space similar to those dif. ferences in productivity which enable the appropriation of profit as rent in agriculture.

The role of rent in the industrial context has already been shown to be quite different from that in agriculture. Even so, other potential land uses in urban areas cannot be equated with productive industry. The relation between exchange value and productivity at any particular location was shown to be crucial for differential rent to arise in an industrial sector, and this relationship cannot be expected to be reproduced for the other major land uses in urban areas. For them location either does not affect their value but only their market price (e.g. housing), or they are unproductive users. A comparison of these non-industrial activities with the agricultural case will highlight the problems of transferring differential rent to the urban context.

The urban situation does not correspond to that in agriculture because the type of production, in which land intervenes as a condition of production, is very different. The main effect is that the relationship between the market price of the commodity produced and the rent extracted differs: the com- modity produced in agriculture being ‘corn’ and on urban land, ‘buildings’. What creates the main difference is the type of market structure being con- sidered. Corn is sold at a uniform market price so that corn rents will be deter- mined by quantitative differences in yields (and transport costs) between the various points of production. Buildings, however, have no uniform market price, even for specific uses. Instead, the price at which a building can be leased or sold will depend on its location. This does not correspond to the agricultural case where the effect of location was not to alter the price at which the com- modity was sold but its individual average price of production. Thus the rela- tionship between rent and market price cannot be assumed to be the same in the urban and the agricultural context.

The use to which agricultural land is put is directly productive, a commodity is produced and the farmer pays rent out of the revenue from its sale. In urban areas, however, although the construction of the ‘built environment’ requires the expenditure of labour, the uses to which those buildings are put need not produce surplus value. In fact, the unproductive activities of commercial and banking capital occur where land values are highest. This is not meant to imply a moral condemnation of those sectors but is merely noted in order to show the different role played in the reproduction of the capitalist mode of production by urban land, and the ownership of that land, as compared with agriculture.

In addition, the relationship between landlord and tenant farmer is not reproduced in the urban development process. A developer might purchase

lo Edel (1976) gives a survey of much of the recent urban work and Scott (1976) considers the French literature on this issue.

Property and rent: a symposium

Michael Ball 40 I

or lease the site from the landowner, employ a separate builder to construct the building, borrow funds from a bank to finance the development, and sell to purchasers who might themselves have to borrow to pay for the dwelling. The chain could be extended even further if the purchaser of the new dwelling intended to rent it to another party. The relations between all these separate

could fundamentally affect both the final price paid for the building and the rent to the initial landowner.” The simple transference from the agri- cultural case to the urban situation can lead to the search for some universal element which differentiates one plot of urban land from another. This element is inevitably accessibility which then becomes the dominant determinant of land rents and uses. Other factors can be recognized within this framework, such as the environmental quality of certain areas or the monopoly control Over large tracts by specific institutions (e.g. ‘finance capital’ or the remnants offeudal landholdings). But these other factors are inserted as deviations from the supposed ideal case ofdifferential rent caused by variations in accessibility. The absence of a uniform market price is replaced by an analysis of demand at the level of the individual, either by vague statements about variations in productivity for firms or by recourse to variations in ‘utility’ for households (cf. the work of Alonso (1964)). Within this type of formulation the structural effects of location have, therefore, been relegated to a level where locational factom are a mere element in individual choice. The attempted application of the marxist concept of differential rent to urban areas can thus lead to an analysis within an idealist problematic.

A similar argument can be applied to the use of the category of absolute rent in the urban context. Nevertheless, rejection of the categories of rent used for agriculture does not mean that the analysis of urban rent must take place irr a theoretical vacuum. But neither does it mean that a theory needs to be developed which specifies, in a detailed manner, the class relations which generate urban rent and into which the various historically unique elements ofspecific urban areas can be slotted in order to explain their particular devia- tions from this ideal ‘theoretical’ specification. Such an analysis would have no place within the marxist problematic. Instead, urban rent must be subject to the same kind of theoretical analysis as that undertaken in Capital of mer- chants’ and banking capital. Marx’s analysis of merchant capital, for example, specified the reasons for its ability to extract surplus value from industrial capi- talists, the fact that it was not itself productive, its historical development and the forms it took. But he tried to specify neither the levels of profit earned by merchants’ capital (other than those which relate to the rate of profit for the system as a whole, of which merchants’ capital cannot be independent),

l1 The relation between landlord and capitalist farmer in agriculture is obviously a simplification of the structure of agricultural production (e.g. farmers use loan capi- tal). The amount of surplus value that can be appropriated through the agricultural sector, however, is determined by this struggle between landlord and farmer and its effect on the market prices ofagricultural commodities. In the urban case, on the other hand, the appropriation of surplus value through the rent on buildings is determined by the structural relations between all the agents that have been specified.

402 Property and rent: a symposium

nor their exact class position in a social formation, nor their size, nor the turn. over time of their capital. Such questions can only be asked in concrete situa. tions, using the concepts developed within historical materialism. The same is true of urban rent relations. Urban rent relations represent a struggle over surplus value between fractions of the bourgeoisie. But the exact magnitude of the rents cpnnot be deduced from theoretical generalizations but only from the analysis of concrete situations. Theoretical analysis, in isolation from a concrete situation, can only examine certain forms which that struggle might take : for example, the relation between property speculation and the specula- tive booms that can occur with a surfeit of money capital.

Given these conclusions, it seems unreasonable to expect any general theoretical analysis to provide an adequate answer about specific urban rent levels. What is required are concrete analyses which take account of social relations and the historical development of the area in question. These would have to include consideration of such factors as accessibility and the physical environment, but only within the context of such a strccture, and not as the dominant determinants which then provide a socially ‘neutral’ explanation of rents.

Birkbeck College, London

VI References

Alonso, W. I 964 : Location and land use. Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press.

Althusser, L. and Balibar, E. 1970: Reading Capital. London: New Left Books.

Banaji, J. 1976: Summary ofselected parts of Kautsky’s ‘The agrarian ques- tion’. Economy and Society 5.

Blaug, M. I 968 : Economic theory in retrospect. London : Heinemann Educational Books.

Buchanan, D. 1929: The historical approach to rent and price theory, Ecom- mica. Reprinted in Fellner, W. and Haley, B., editors, Readings in the theory of income distribution, American Economic Association.

Cutler, A. 1975 : The concept of ground-rent and capitalism in agriculture. Critique of Anthropology 415.

Cutler, A. and Taylor, J. 1972: Theoretical remarks on the theory of the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Theoretical Practice 2.

Edel, M. 1974: The theory of rent in radical economics. Boston studies in urban political economy working paper I 2.

1976 : M a d s theory of rent: urban applications. In Housing and class in Bri- tain, London : Housing Workshop of Conference of Socialist Economists.

Kay, G. 1976: A note on abstract labour. Bulletin of Conference of Socialist Economists 5 , March.

Lenin, V. I g I 3 : Karl Man. Collected Works, volume rg. Lipietz, A. 1974: Le tribut foncier urbain. Paris: Maspero. Massey, D. 1974: Towards a critique of industrial location theory. London:

Centre f o r Environmental Studies Research Paper 5.

Michael Ball 403

Massey, D. and Catalano, A. I 978 : Capital and land: landownership by capital

Ricardo, D. I 95 I : On the principles of political economy and taxation, Sraffa edi-

Scott, A. 1976: Land and land rent: an interpretative review of the French

in Great Britain. London : Edward Arnold.

tion. London : Cambridge University Press.

literature. Progress in Geography 9.