Development of the Three-Clinic Hearing Aid Selection ...b, 1997, 1998, 1999) pertinent to why...

Transcript of Development of the Three-Clinic Hearing Aid Selection ...b, 1997, 1998, 1999) pertinent to why...

J Am Acad Audiol 12 : 128-141 (2001)

Development of the Three-Clinic Hearing Aid Selection Profile (HASP) Gary P. Jacobson* Craig W. Newman' David A. Fabryt Sharon A. Sandridget

Abstract

The Three-Clinic Hearing Aid Selection Profile (HASP) was developed to assess a patient's beliefs about a number of basic considerations felt to be critical to the hearing aid selection (HAS) process. These characteristics are felt to be key to the acceptance of amplification and include motivation, expectations, cost of goods and services, appearance (cosmesis), attitudes about technology, physical function/limitations, communication needs, and lifestyle . The results of the first investigation suggest that we have been successful in developing a 40-item metric with adequate internal consistency reliability that assesses the aforemen-tioned characteristics. Second, results of the administration of this tool to a large group of individuals indicated that (1) age impacted scores on the Technology, Physical Function, and Communicative Needs subscales; (2) gender impacted scores on the Motivation, Expectation, Technology, Communicative Needs, and Appearance subscales; (3) previous hearing aid use affected scores on the Motivation subscale ; (4) level of education impacted scores on the Physical Function and Lifestyle subscales; and (5) self-perceived hearing handicap had an effect on Motivation and Communicative Needs subscale scores . Percentile data collected from this subject sample are presented as a benchmark against which to evaluate responses from individual patients . Case studies are presented to illustrate the potential clinical utility of this device .

Key Words: Amplification, expectations, hearing aid, outcomes measures, satisfaction

Abbreviations : ANOVA = analysis of variance, CIC = completely in the canal, COSI = Client Oriented Scale of Improvement, DSP = digital signal processing, HAS = hearing aid selec-tion, HASP = Hearing Aid Selection Profile, HHIA = Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults, HHIE = Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly

t is a common perception that a successful hearing aid fitting is, in large part, based on the ability to narrow the gap between a

patient's expectations of what a hearing aid will do and what the audiologist knows the hearing aid can do . That is, the recommendation of a par-ticular hearing aid fitting probably is best derived as a function of the partnership between the audiologist and the patient. Given this rela-

*Division of Audiology, Department of Otolaryn-gology-Head and Neck Surgery, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan ; (Department of Otolaryngology and Communicative Disorders, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio ; $Department of Otolaryn-gology, Mayo Clinic Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota

Reprint requests : Gary P. Jacobson, Division of Audiology, Henry Ford Hospital, 2799 West Grand Blvd ., Detroit, MI 48202

tionship, the assumption follows that a suc-cessful hearing aid fitting occurs when the patient is empowered in the hearing aid selec-tion (HAS ; also referred to by some as "hearing aid evaluation") process. This occurs when the patient is informed fully about the relative ben-efits of all types of hearing aids that are appro-priate for the patient's hearing loss, lifestyle, physical function, and communication needs, among other biopsychosocial considerations . Few patients, however, are capable of under-standing all of this information in a short period of time (i .e ., during the HAS appointment) . A more likely scenario is that the audiologist uses his/her professional expertise to counsel the patient to accept a style and level of hearing aid technology felt to be most appropriate. It is note-worthy that substantial information exists from

128

Development of the HASP/Jacobson et al

the many MarkeTrak surveys (Kochkin 1994a,

b, 1997, 1998, 1999) pertinent to why patients resist, dislike, or reject amplification . Although these investigations have provided information about group characteristics of hearing aid wear-ers and nonwearers, the information has not been used prospectively to assess each patient's views about these key characteristics prior to the audiologist's recommendation of a particular hearing aid . It is likely that, given this infor-mation, the number and types of possible hear-

ing aid fittings would converge on an "ideal fitting" based on the audiologist's expertise and

the patient's prefitting perceptions and needs .

In this regard, there are currently no assess-ment tools to assist the audiologist in the selec-tion of the most appropriate hearing aid from the

patient's point of view. That is, in an hour or less, an audiologist must effectively counsel a patient regarding all types of available amplification options, ascertain patient's wants and needs, recommend specific devices, and take earmold impressions . This process requires that the patient understand and process highly techni-cal information that is presented at a rapid rate in a rather limited amount of time . Because of this time limitation, clinicians are often forced to make assumptions regarding a patient's atti-tudes toward cost, cosmetics, and performance as they relate to hearing aids . Although experi-enced clinicians may develop specific expertise

or techniques for acquiring this information from patients during the HAS appointment, it remains a time-consuming and cumbersome process .

To this end, the general goal of this series of investigations was to develop a standardized measure to be administered prior to the HAS appointment . The measure would yield, in a time-efficient manner, information regarding a patient's perspectives in key areas pertinent to the selection of a hearing aid . In this way, the audiologist could spend his or her limited clin-ical time providing more intensive counseling about such issues as realistic expectations and communication strategies . More specifically, the

aims of this study were to (1) develop a simple

and standardized device that might be helpful in constraining the field of hearing aid choices

based on the individual needs of a given patient and (2) evaluate how patient characteristics (e .g ., age, gender, previous hearing aid use, magnitude of hearing handicap, and educational level) affect responses to items comprising this device . The metric described in the following two investi-gations, namely, the Three-Clinic Hearing Aid

Selection Profile (HASP), was developed by investigators at the Henry Ford Health Sys-tem, the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and the Mayo Clinic .

INVESTIGATION 1: DEVELOPMENT OF THE HASP

Method

Subjects

Participants were 130 adults seen for HAS appointments at the three clinics . There were 72 (55%) males and 58 (45%) females. The average age of this sample was 64.2 years (SD = 14.5 years, range = 14-90 years) .

Test Development

The initial set of 70 items comprising the alpha version of the HASP was generated based on the collective experience of the investigators with hearing aid patients and/or information regarding consumer acceptance of hearing aids from the MarkeTrak investigations (Kochkin, 1994a, b, 1997, 1998, 1999). Test items (Table 1) were generated in a manner so that they could be categorized as belonging to one of eight con-tent domains (subscales) . It was the investiga-tors' a priori assumption that having individual patient information for each of the subscales would be important for the appropriate selection and patient acceptance of amplification. Two of the eight subscales contained items specific to hearing aid use and related to

1. Motivation to wear hearing aids (Motivation) (12 items) and

2. Expectations from hearing aid performance (Expectations) (9 items) .

The remaining six subscales contained items that were nonspecific to hearing aid use. These categories were designed to assess a patient's per-ceptions of

3 . The importance of their physical appear-ance to others (Appearance) (10 items),

4. The cost of commercial goods and services (Cost) (9 items),

5. Attitudes toward technology (Technology) (7 items),

6 . Their own manual dexterity (Physical Func-tion) (7 items),

129

Journal of the American Academy of Audiology/Volume 12, Number 3, March 2001

Table 1 Items Comprising the Alpha Version of the HASP and Associated Item-Total Correlation Coefficients (in Parenthesis) .

Motivation subscale 39M I want to wear a hearing aid even if I still have difficulty hearing in some situations . (0 .48) 43M I know that a hearing aid will help me. (0 .63) 53M I am prepared to do what it takes to improve my hearing . (0 .61) 61 M I am certain that I want a hearing aid . (0 .65) 62M I am having a significant problem understanding speech . (0.53) 4M I would rather do it myself than have someone else do it for me . (0 .20) 14M I am the type of person who needs to hear everything . (0 .39) 18M I have been embarassed in public because of my hearing . (0 .44) 23M I get very frustrated if I don't hear every word that is being said . (0 .49) 24M The decision to obtain a hearing aid is mine alone . (0,24) 27M I have missed much in life because of a hearing problem . (0 .34) 46M I am always striving to improve myself . (0 .19)

Expectations subscale 35E A hearing aid will restore my hearing to normal just as eyeglasses restore vision to normal. (0 .61) 37E I expect that my hearing aid will improve my ability to understand speech in background noise. (0 .55) 41 E My hearing aid will make speech clear, distinct, and understandable in all situations . (0 .71) 68E A hearing aid will make it possible for me to understand speech in all situations . (0 .77) 69E My hearing aid will make speech sound natural. (0 .76) 12E I will not have to read lips when wearing my hearing aid . (0 .36) 16E I expect that I will learn how to operate my hearing aid immediately . (0 .49) 52E I will adjust to a hearing aid easily. (0 .30) 64E My hearing aid will never need repair. (0 .25)

Appearance subscale 5A If I were losing my hair, I would get a transplant, wear a wig or toupee, or take medicine to make it stop. (0.43) 10A I do not feel comfortable about leaving the house unless I look just right. (0.38) 31A There is nothing wrong with using plastic surgery to improve one's appearance. (0.41) 40A I am self-conscious about my appearance . (0.51) 49A I am often concerned about how others view my appearance . (0 .69) 8A I believe people should spend more time being concerned about how they look to others . (0 .42) 20A I am not content with my appearance . (0 .45) 25A I am concerned that wearing a hearing aid will make me look older. (0 .46) 26A If I had problems with my vision, I would wear contact lenses rather than eyeglasses . (0 .32) 54A I am very interested in my health and appearance . (0 .21)

Cost subscale 13C I am not an extravagant buyer (0.39) 51 C 1 don't think that I need the best that money can buy. (0.35) 55C When it comes to money, I don't like to take risks. (0.47) 60C I am a price-conscious consumer (0.48) 63C I only purchase items that I can afford. (0.38) 1C I am a bargain hunter. (0 .30) 9C I believe that most products are overpriced . (0 .37) 22C I do consider myself a wise shopper. (0 .23) 48C I am not willing to pay more money for higher-quality products . (0 .25)

Technology subscale 2T Computers have made our lives easier and better (0 .43) 11T I have or would like to have a cellular phone . (0 .44) 42T I feel that new technology has improved our lives. (0 .40) 50T 1 like gadgets such as remote controls and find them very useful . (0 .41) 59T 1 have a microwave oven and have used one for many years . (0 .37) 57T When I purchase a new device, I always read the owner's manual . (0.16) 67T I feel comfortable programming my VCR to record a TV show . (0.38)

Physical Function subscale 33P I do not have arthritis in my fingers . (0.38) 38P I have good sensation in my fingertips . (0.63) 66P I have no difficulty (or would have no difficulty) holding or shuffling cards . (0.50) 70P I can hold my hands steady, in one position, for at least 10 seconds. (0.51) 19P It is easy for me to use small objects such as paper clips, coins, small buttons, and/or zippers . (0.44) 3P I do not have any difficulty touching my fingers to my ear . (0 .47) 36P My vision for reading is good (i .e ., my best vision with or without eyeglasses or contact lenses) . (0 .25)

130

Development of the HASP/Jacobson et al

Table 1 Items Comprising the Alpha Version of the HASP and Associated Item-Total Correlation Coefficients (in Parenthesis) (Continued)

Communicative Needs subscale 21 CN It is very important for me to hear conversations with one other person . 29CN It is very important for me to be able to hear on the telephone . 44CN It is very important for me to hear the television and/or radio. 47CN It is very important for me to be able to hear in a place of worship, at a lecture, at a concert and/or movies . 65CN It is very important for me to hear conversations when 1 am in larger groups, for example, at a party.

15CN It is very important for me to hear conversations when I am in a restaurant .

Lifestyle subscale 32L 1 consider myself to be an active, busy, "on-the-go" kind of person . 34L Physical activity is an important part of my life . 45L 1 enjoy going to movies, lectures, parties, restaurants, and/or the symphony. 56L 1 am quite active and involved in lots of activities and social events . 58L I consider myself to be in good physical condition . 6L I like traveling and going on vacations . 7L I have taken measures to live a healthier lifestyle . 17L I am happiest when I am around many people . 28L I spend very little time at home reading or watching television . 30L I socialize often with friends and/or family members .

(0.50) (0.60) (0.52) (0.54) (0.68) (0 .43)

(0.57) (0.54) (0.62) (0.62) (0.48) (0 .32) (0 .34) (0 .37) (0 .14) (0 .38)

E = Expectations, M = Motivation, A = Appearance, C = Cost, T = (Fear of) Technology, P = Physical Function, CN = Communicative

Needs, L = Lifestyle

Items in italics were included in the beta (final) version of the Three-Cllnc HASP.

7 . Listening situations to which they are fre-quently exposed (Communicative Needs) (6 items), and

8. Their activity levels (Lifestyle) (10 items) .

Items were worded in such a way that they could be answered on a 5-point Likert scale with the anchors being strongly agree and strongly disagree . A strongly agree response received 4 points and a strongly disagree response received a score of 0 points . A neutral response received a score of 2 points . The alpha version of the HASP was administered using a paper-and-pen-cil format prior to hearing aid counseling but fol-lowing the audiometric evaluation .

Results

Complete alpha version HASPS were obtained from 120 of 130 subjects (92%), form-ing the data pool for the analysis . Ten subjects provided incomplete data, which were excluded from the analysis . Item E64 ("My hearing aid will never need repair.") was the most frequently unanswered item and was subsequently removed from the beta version of the HASP.

The overall Cronbach's alpha was estimated

for each subscale as were the individual cor-rected item-total correlations . The objective of this analysis was to group items in such a man-ner that a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.70 or

higher would be obtained for each subscale . Items were excluded if the corrected item-total correlations were <_ 0 .30 . Following the initial analysis, the alpha coefficients were reassessed in an iterative fashion . This process ended when all corrected item-total correlations were >_ 0.30 and the alpha coefficient remained at approxi-mately 0.70 . As can be noted in Table 2, the Expectations, Motivation, Appearance, Lifestyle, Communicative Needs, and Physical Function subscales had Cronbach's alpha values greater

than 0 .70, and each item-total correlation exceeded 0.40 . The subscales of Technology and Cost had alpha values just above 0.66 with item-total correlations above 0.30 .

Through this process, the beta (final) version of the HASP was developed and is shown in Table 1. The final version had a total of 40 items that were comprised of the original eight sub-scales, each having five items . A patient's responses to each item again were on a 5-point Likert scale, with a strongly agree receiving a maximum of 4 points and a strongly disagree receiving a minimum score of 0 points . Accord-ingly, a maximum score for each subscale was 20 points (5 items X a maximum score of 4 points for each item = 20 points) . It was decided that the wording of the Cost and Appearance sub-scales was such that they should be reverse-scored for the subscale scores to be in a direction consistent with the other six subscales (i .e ., a

131

Journal of the American Academy of Audiology/Volume 12, Number 3, March 2001

Table 2 Item-Total Correlations for Items Comprising the Beta Version of the HASP and Cronbach Alpha

Values for the Eight HASP Subscales

Alpha Coefficient Item #

Item-Total Correlation Coefficient

Motivation 0.84 M39 0.56 M43 0.69 M53 0.70 M61 0.76 M62 0.53

Expectations 0.88 E35 0.68 E37 0.55 E41 0.77 E68 0 .83 E69 0 .77

Appearance 0.69 A5 0.45 A10 0 .38 A31 0.32 A40 0.49 A49 0.60

Cost 0.66 C13 0.48 C51 0.39 C55 0.41 C60 0.41 C63 0.38

Technology 0.66 T2 0.40 T11 0.46 T42 0.45 T50 0.33 T59 0.41

Physical Function 0.73 P19 0.37 P33 0.42 P38 0.66 P66 0.45 P70 0.49

Communicative Needs 0.79 CN21 0 .48 CN29 0 .61 CN44 0.52 CN47 0.55 CN65 0.65

Lifestyle 0.77 L32 0.65 L34 0 .61 L45 0.36 L56 0.61 L58 0.49

greater subscale score is generally considered more favorable from a clinical perspective and a lesser subscale score is generally considered less favorable) .

INVESTIGATION 2: EFFECTS OF SUBJECT CHARACTERISTICS ON

HASP SUBSCALE SCORES

Method

Subjects

The beta version of the HASP was admin-istered to another sample of 242 patients seen for HAS appointments at the hearing aid cen-ters of our three clinics. The mean age of this sample was 66.8 years (SD = 14.0), ranging from 21 to 96 years of age. Table 3 summarizes the demographic data for this sample of patients . Table 4 displays mean audiometric data demon-strating that the majority of subjects had a slop-ing mild to moderately severe sensorineural hearing loss with the mean word recognition scores consistent with audiometric configuration and severity.

Procedures

The HASP was administered after audiom-etry had been conducted but prior to any coun-seling associated with the HAS. As in Investigation 1, the HASP was completed using a paper-and-pencil format . In addition to com-pleting the HASP, patients also completed either the screening version of the Hearing Handicap

Table 3 Demographic Characteristics of the Subject Sample

Reported in the Second Investigation

Variable Sample Size (%)

Gender Male 135 (55 .8) Female 107 (44.2)

Age classification* Young 82(34.0) Old 159 (66.0)

Education levels < High school 58 (24 .7) High school 80 (34 .0) Associates degree 39 (16 .7) BA/BS degree 27 (11 .5) Postgraduate degree 31 (13 .2)

Hearing aid experience* Previous user 114 (47.3) New user 127 (52 .7)

Hearing handicapt No hearing handicap 19 (7 .9) Mild-moderate hearing handicap 84 (35 .0) Severe hearing handicap 137 (57 .1)

Missing information for *one subject ; tseven subjects ; ttwo subjects .

132

Development of the HASP/Jacobson et al

Table 4 Means and SDs for Right and Left Air-Conduction Thresholds (dB HL) and Word Recognition Scores (Percent Correct) for Patients in Investigation 2

Frequency (Hz)

250 500 1000 2000 3000 4000 6000 WRS (%)

Right ear Mean 37.14 38.91 44.14 53.03 61 .17 63 .45 6828 78.82 SD 24.88 24.31 24.31 21 .87 21 .13 21 .75 23 .67 24.10

Left ear Mean 21 , 12 20.74 20.39 50 65 59.91 61 .17 66 .16 81 .44 SD 21 .21 20.74 20.39 19 .81 18.98 20.31 20 .96 19.45

Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE-S ; Weinstein, 1986), for subjects who were 65 years and older, or the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults (HHIA-S ; Newman et al, 1991), for subjects younger than 65 years of age . The HHIE-S and HHIA-S are abbreviated (10-item) versions of the full HHIE and HHIA. Each of the 10 items is answered using a yes, sometimes, or no response format . A yes response is scored as 4 points, a sometimes response is scored as 2 points, and a no response is scored as 0 points . Accordingly, a maximum score on the HHIE/HHIA-S scales is 40 points, representing maximum self-perceived hearing handicap . The hearing handicap clas-sification system (Weinstein and Ventry, 1983) used with the full HHIE-A was adapted for the present investigation . A score of <_ 6 points on either the HHIA-S or HHIE-S was considered to constitute no hearing handicap . A score of >_ 8 points and <_ 18 points was considered a mild-moderate hearing handicap . A score of >_ 20 points was considered evidence of severe hearing handicap . As shown in Table 3, over half (57%) of the subjects reported a perceived severe handicap .

sified as old . Table 5 shows a summary of results for the HASP subscales . Only the Technology (t = 4.33, df = 239, p < .001), Physical Function (t = 4.31, df = 239, p < .001), and Communica-tive Needs (t = 2.16, df = 239, p = .03) subscales reached statistical significance . Specifically, younger patients tended to be more comfort-able with high technology and had fewer phys-ical (i .e ., manual dexterity) limitations . Older

patients had significantly fewer communicative needs .

Gender. Student's t-tests were used to exam-ine the effects that gender played in HASP sub-scale scores (Table 6) . Women showed greater motivation to obtain hearing aids (t = -3.16, df = 240, p = .002), had greater expectations of the hearing aids (t = -2.47, df = 240, p = .01), were slightly more comfortable with higher tech-nology (t = -1.95, df = 240, p = .05), and felt that they had greater communicative needs than men (t = -4.63, df = 240, p < .001). An unexpected finding was that men were significantly more appearance-conscious than women (t = 8.18, df = 240, p < .001).

Results

Group Analyses

The sample was analyzed as a function of age, gender, previous hearing aid use, educa-tional level and by severity of self-perceived hearing handicap (as reflected by the HHIE/A-S scores). The following are the results of the

group analyses . The alpha level was adjusted to compensate for repeated use of t-tests.

Age. Student's t-tests were used to examine age effect on HASP subscale scores . Those patients who were <_ 64 years were classified as young and those who were >_ 65 years were clas-

Previous Hearing Aid Use. The effect of previous hearing aid use on the HASP scores was

examined using Student's t-tests . As can be seen in Table 7, there were no statistically significant differences in the HASP subscale scores, with the exception of the Motivation subscale . Previous hearing aid wearers showed greater levels of motivation than new hearing aid wearers (t = 5.19, df = 233.1, p < .001) .

Education Level . Educational background of the subject sample was divided into five levels . These levels served as the grouping factors, with the HASP subscale scores serving as the dependent variables for a series of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) . Table 8 summa-

133

Journal of the American Academy of Audiology/Volume 12, Number 3, March 2001

Table 5 Means and SDs for HASP Table 7 Means and SDs for HASP Subscale Scores for Young and Old Subjects in Investigation 2

Subscale Sc New Hearing Aid

ores for Previous and Users in Investigation 2

HASP Subscale Young Old p Value HASP Subscale P revious User New User p Value

Motivation 15 .5 (2 .9) 15 .1 (3 .0) 35 Motivation 16 .2 (2 .4) 14 .4 (3 .2) < .001 * Expectations 13 .2 (3 .6) 12 .9 (2 .9) 58 Expectations 12 .7 (4 .0) 13.4 (3 .5) 16 Appearance 8.0 (3 .4) 8.3 (3 .4) 46 Appearance 8.4 (3 .5) 8.0 (3 .3) 29 Cost 5.7 (2 .6) 5 .8 (2 .6) 80 Cost 5 .8 (2 .5) 5 .7 (2 .7) 91 Technology 16 .0 (2 .7) 14 .4 (2 .7) < .001 Technology 15 .2 (3 .1) 14.7 (2 .5) 16* Physical 16 .0 (3 .0) 14 .0 (3 .6) < .001 Physical 14 .8 (3 .7) 14 .5 (3 .5) 56 Communicative Needs 17 .1 (2 .3) 16 .4 (2 .3) 032 Communicative Needs 16 .8 (2 .4) 16.6 (2 .3) 63 Lifestyle 14 .8 (3 .0) 14 .1 (3 .1) 09 Lifestyle 14 .4 (3 .1) 14 .2 (3 .0) 66

Also shown are probability values associated with Student's t-tests for each of the subscales.

Also shown are probability values associated with Student's t-tests for each of the subscales.

*Welch's test used due to unequal variances .

rizes the results of the statistical analyses of the data as a function of education level. Significant group differences were observed for only two subscales: Physical Function (F = 3.02, df = 4, p = .02) and Lifestyle subscales (F = 3.18, df = 4, p = .01) . Post hoc testing (Tukey) with Bonfer-roni correction for multiple comparisons (result-ing in an adjusted alpha = 0.005) for the Physical Function subscale revealed that individuals with postgraduate degrees had less physical limitations than individuals with a high school education (t = -2.99, df = 109, p = .003). Post hoc testing for the Lifestyle subscale showed that those with postgraduate education also had more active lifestyles than those with a high school (t = -3.25, df = 87, p = .002) or less than a high school education (t = -3.49, df = 109, p < .001).

Magnitude of Hearing Handicap. Table 9 summarizes the results of the statistical analysis on the basis of hearing handicap . The data were analyzed separately for each of the HASP subscales

Table 6 Means and SDs for HASP Subscale Scores for Male and

Female Subjects in Investigation 2

HASP Subscale Males Females p Value

Motivation 14 .7 (3 .0) 15 .9 (2 .8) 002 Expectations 12 .5 (3 .5) 13 .7 (4 .1) 014 Appearance 9 .6 (3 .1) 6 .4 (2 .9) < .001 Cost 6 .0 (2 .6) 5 .4 (2 .6) .08 Technology 14 .7 (2 .7) 15 .4 (2 .8) .05 Physical 14 .5 (3 .0) 14 .8 (4 .1) 52 Communicative Needs 16 .1 (2 .3) 17 .4 (2 .1) < .001 Lifestyle 14 .1 (2 .8) 14 .6 (3 .4) 24

Also shown are probability values associated with Student's t-tests for each of the subscales.

with a one-way ANOVA. The HASP subscale scores served as dependent variables, and sever-ity of self-perceived hearing handicap (i .e ., no handicap, mild-moderate handicap, severe hand-icap) served as the grouping factor. Significant group differences were observed for the Motiva-tion (F = 25.9, df = 2, p < .001) and Communica-tive Needs subscales (F = 5.2, df = 2, p = .006). Post hoc testing (Tukey with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons resulting in an adjusted alpha = 0.017) showed that, for the Motivation sub-scale, only the group comparisons between no handicap and severe handicap and between mild-moderate handicap and severe handicap were significant (no hearing handicap vs mild-moder-ate hearing handicap, t = -2.0, df = 101, p = .04; no hearing handicap vs severe hearing handicap, t = -6.10, df = 154, p < .001 ; mild-moderate hear-ing handicap vs severe hearing handicap, t = -5.83, df = 219, p < .001). Therefore, these find-ings suggest that a patient's motivation to obtain hearing aids increases as his or her self-perceived hearing handicap increases. Post hoc testing for the Communicative Needs subscale showed that the comparison of mild-moderate hearing handi-cap to those with severe hearing handicap was sig-nificant (t = -2 .69, df = 219, p = .008) . As anticipated, patients with severe hearing handi-cap had greater communicative needs than did patients with mild-moderate hearing handicap .

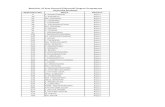

Percentile Plots. Figure 1 graphically dis-plays the percentile data obtained for each sub-scale. As can be seen, for our patients, the 95th percentile corresponded to a HASP score of 19 or 20 for six of the subscales (Motivation, Expec-tation, Technology, Physical Functions, Com-municative Needs, and Lifestyle), suggesting that our subjects were highly motivated, had

134

Development of the HASP/Jacobson et al

Table 8 Means and SDs for HASP Subscale Scores for the Five Levels of Education for Subjects in the Second Investigation

HASP Subscale < High School High School Associates Degree BA/BS Postgraduate

Motivation 15 .6 (2 .8) 15 .1 (2 .7) 15 .5 (2 .9) 14 .4 (3 .7) 15 .2 (3 .6) Expectations 14.0 (3 .6) 13 .0 (3 .8) 12 .9 (3 .7) 11 .4 (3 .9) 12 .8 (4 .0) Appearance 8.5 (3 .4) 7 .5 (3 .3) 8 .3 (3 .4) 8 .9 (2 .3) 9 .1 (4 .2) Cost 5.5 (2 .6) 5.8 (2 .7) 5.6 (2 .3) 5.9 (2 .3) 6 .2 (3 .1)

Technology 14.4 (26) 14 .6 (2 .3) 15 .6 (2,8) 14 .8 (3 .8) 16 .1 (3 .0) Physical 14 .3 (3 .1) 13 .9 (3 .7) 15 .4 (3 .3) 15 .0 (4 .5) 16 .1 (3 .2)

Communicative Needs 16 .7 (2 .3) 16 .8 (2 .2) 16 .5 (2 .3) 16 .0 (2 .9) 17 .1 (2 .2) Lifestyle 13 .8 (3 .0) 13 .9 (2 .7) 14 .8 (3 .9) 14 .2 (2 .7) 15 .8 (2 .6)

high expectations, felt comfortable with tech-nology, had high communicative needs, and led active lifestyles . On the other hand, the subjects, as a group, tended to be concerned about appear-ance and especially the costs of goods and ser-vices as seen by lower scores for the Appearance and Cost subscales . The interval between the 95th and 5th percentiles ranged from 7 to 13 points across the HASP subscales .

DISCUSSION

R ecently, the emphasis in the audiology lit-erature has focused on the application of hearing aid outcome measures to address the questions of treatment effectiveness (e.g ., unaided vs aided benefit and satisfaction ; Wein-stein, 1996), treatment efficiency (e .g ., differences among aided benefit and satisfaction ; Valente et al, 1997 ; Newman and Sandridge, 1998 ; Ricketts and Dhar, 1999), and cost effectiveness (e.g., relative value among different hearing aids in terms of purchase price ; Mulrow et al, 1990; Newman and Sandridge, 1998) . Although sev-eral instruments have been developed for the expressed purpose of quantifying subjective fit-ting outcome (e.g ., Walden et al, 1984; Cox and Alexander, 1995) or modified for purposes of

quantifying hearing aid benefit (e .g., Taylor, 1993), each fails to provide a systematic method for assisting audiologists to select the "best" hearing aid at the outset. In contrast, the HASP is an attempt to provide information that may assist the audiologist in the choice of hearing instruments at the outset, thereby acting more as an "in-come" rather than an "outcome" measure . Our interest in the development of the HASP grew out of frustration in not having adequate tools to determine which specific style and hearing aid options might best serve both the audiologic and nonaudiologic needs of an individual patient. As clinicians, we were ford-ing that the majority of time spent during the HAS appointment was directed toward provid-ing patients with descriptive information about the ever-increasing number of available hearing aid technologies and designs . In turn, insufficient time was left to assess the nonaudiologic factors critical to the selection of an appropriate level of technology and counsel the patient about other management concerns (e.g., realistic expec-tations, adjustment) crucial to the overall suc-cess of the hearing aid fitting. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a measure that might provide clinicians with a systematic method for making a number of fundamental

Table 9 Means and SDs for HASP Subscale Scores for No Hearing Handicap, Mild-Moderate Hearing Handicap, and Severe Hearing Handicap Groups in Investigation 2

HASP Subscale No Hearing Handicap Mild-Moderate Hearing Handicap Severe Hearing Handicap

Motivation 12 .5 (3 .9) 14 .2 (3 .0) 16 .3 (2 .3) Expectations 12 .9 (4 .1) 13 .2 (3 .8) 12 .9 (3 .8) Appearance 8.7 (3 .6) 8.4 (3 .8) 8.1 (3 .2)

Cost 6.1 (3 .0) 6.0 (2 .5) 5.5 (2 .6)

Technology 14 .9 (2 .4) 15 .2 (2 .9) 14 .8 (2 .8) Physical 14 .7 (4 .6) 15 .1 (3 .2) 14 .4 (3 .6) Communicative Needs 15 .8 (2 .3) 16 .2 (2 .6) 17 .1 (2 .1) Lifestyle 15 .1 (2 .8) 14 .5 (2 .7) 14 .1 (3 .3)

135

Journal of the American Academy of Audiology/Volume 12, Number 3, March 2001

Motiv Expect Appear Cost Tech Phy Comm Lifestyle Func Needs

HASP Subscales

Figure 1 Display of "empty" matrix used to plot indi-vidual patient HASP subscale scores against the per-centile responses of the subject sample . The lines illustrate the 5th through 95th percentiles for each of the eight HASP subscales. Please be aware that both the Appear-ance and Cost subscales are reverse scored (i.e ., a zero subscale total is scored as a maximum, 20-point, positive response). Motiv = Motivation, Expect = Expectation, Appear = Appearance, Tech = Technology, Phy Func = Physical Function, Comm Needs = Communicative Needs.

decisions during the HAS process based on sev-eral patient characteristics .

The HASP was designed to be administered prior to the HAS appointment in order to pro-vide the clinician with information regarding patient motivation, expectations, communicative needs, and lifestyles, as well as concerns/per-ceptions regarding cost, appearance, technol-ogy, and the existence of physical limitations. It is noteworthy that items comprising only three of the eight subscales (i .e ., Expectations, Moti-vation, and Communicative Needs) were designed to relate specifically to hearing and hearing aids . In contrast, the content of items comprising the remaining five subscales was designed to be more generic in nature, provid-ing a more global picture of the individual . That is, we believed that having a greater under-standing of the patient's core belief and atti-tude system would be beneficial in constraining the choices of hearing aids in the selection process.

The results of the present investigation demonstrated that the HASP has adequate inter-nal consistency reliability for each of the eight subscales. Further, the group performance on each of the eight subscales was analyzed as a function of age, gender, education level, self-perceived hearing disability/handicap, and pre-vious hearing aid use. Although the relationships among the demographic variables are probably not completely independent, the outcome of the

exploratory group demographic analyses revealed several interesting observations.

As might be predicted, younger patients were more comfortable with higher technology, had fewer physical (manual dexterity) limita-tions, and reported greater communicative needs in comparison with older adults . Studies have consistently shown that older adults have fewer communication demands in a variety of listen-ing environments and fewer perceived emotional and social/situational hearing handicaps (Gor-don-Salant et al, 1994 ; Erdman and Demorest, 1998) in comparison with young adults . It is not surprising, therefore, that older adults are less likely to pursue audiologic recommenda-tions, including being fit with amplification (Dodds and Harford, 1982 ; Garstecki and Erler, 1996; van den Brink et al, 1996; Brooks and Hallam, 1998) . Yet, in the present study, there were no age-related differences observed for the Motivation subscale . This finding is not sur-prising, given that the HASP was administered to patients already scheduled for the HAS appointment . That is, subjects enrolled in the present investigation had already decided to pursue obtaining amplification, thereby forming somewhat of a self-selected subject sample .

Evaluation of gender differences demon-strated that women were found to be more highly motivated and had greater expectations and communicative needs. Previous studies have suggested that women place greater importance on communication in social situations (Erdman and Demorest, 1998) and are willing to assume responsibility for effective communication (Garstecki and Erler, 1998).

Previous users demonstrated higher levels of motivation toward hearing aid use than first-time candidates . These results are not surpris-ing, given the fact that this subject sample was returning to pursue the purchase of new hear-ing aids when the HASP was administered.

For our subject sample, individuals with higher levels of education were found to have fewer physical limitations and a more active lifestyle. Again, these observations were not unexpected, given that higher levels of education are more closely associated with white-collar jobs, which are typically less physically demand-ing. In addition, there is a reported inverse rela-tionship between socioeconomic level and prevalence of disease and disability (Dunkle and Kart, 1991). Accordingly, higher income potentially results in greater access to medical and preventive health care .

136

Development of the HASP/Jacobson et al

Lastly, as the severity of self-perceived hand-icap became greater, based on responses of the HHIE/HHIA-S, motivation and communication needs significantly increased . These findings are consistent with other reports indicating that individuals with hearing loss pursue audiologic assistance only after they believe that their hearing problem has progressed to a point where they need intervention (van den Brink et al, 1996; Kochkin, 1998) . Accordingly, increases in perceived handicap influence an individual's likelihood to seek help and follow up on audio-logic recommendations .

The percentile scores generated from the present data set may be used to establish a ref-erence to which the responses of individual patients can be compared . That is, the percentile data presented in Figure 1 may serve as a norm-referenced benchmark against which to plot a given patient's responses to the HASP. These data are most helpful in demonstrating how the HASP can be useful at the time of the HAS in helping the clinician recommend the style and level of technology for an individual patient . In this regard, consider the following illustrative cases :

0 Case 1 is a 57-year-old male attorney with a bilateral precipitously sloping high-fre-quency sensorineural hearing loss above 1000 Hz. Following the audiologic evalua-tion, he was administered the HHIA-S and

scored 18 points, suggesting a moderate perceived hearing handicap . At the begin-ning of the HAS appointment, he completed the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI; Dillon et al, 1997), indicating that he specifically wanted to hear better in the courtroom, during business meetings with his partners and clients, when talking with his young grandson, on the telephone, and at restaurants . His scores on the HASP are displayed in Figure 2 . Note that his scores are at or above the 90th percentile except for Appearance, which falls at the 5th per-centile . Based on his high communicative needs (COSI), the use of multimicrophone technology was discussed ; however, this option was eliminated following the patient's expressed strong desire to obtain completely-in-the-canal (CIC) hearing aids only (see appearance score on the HASP). Therefore, a seven-band, two-channel digital signal

processing (DSP) CIC hearing aid with a spe-cially designed high-frequency ski-slope fit-ting rationale was recommended and fitted

2o

15

X10

Motiv Expect Appear Cost Tech Phy Func Comrn Lifestyle Needs

HASP Subscales

Figure 2 HASP for Case 1. Based on his profile, he is strongly motivated, has high expectations (which may not be realistic), is extremely appearance conscious (as noted by the low score), is not concerned about the cost of goods

and services, is comfortable with technology, does not have any significant physical limitations, has high communi-cations needs, and has an active lifestyle . Note that the X's represent the patient's data in this and future figures. Motiv = Motivation, Expect = Expectation, Appear = Appearance, Tech = Technology, Phy Func = Physical Function, Comm Needs = Communicative Needs.

binaurally. His 3-week post HHIA-S indi-cated a significant reduction in self-per-ceived hearing handicap as indicated by a post score of 6 points . This resulted in a pre-/post-difference score of 12 points and exceeded the critical difference value of 10 points, which is considered to be a true change in perceived benefit following inter-

vention (Newman et al, 1991) . The Knowles Hearing Aid Satisfaction Survey (Kochkin, 1992) was completed 3 months postfitting (Figure 3, A and B) . As can be seen, he was satisfied with his hearing aids in a variety of listening conditions . In this case, the HHIA-S and the Satisfaction Survey out-come measures served as external criterion validity indicators of the patient's benefit from and satisfaction with amplification . Further, this case illustrates the usefulness of multiple assessment tools during specific phases of the rehabilitative process-from the initial audiologic evaluation (HHIA) to the HAS (HASP, COSI) to the follow-up appointments (HHIA, Satisfaction Survey) .

" Case 2 is a 73-year-old retired female teacher with a bilateral moderate-to-severe sen-sorineural hearing loss . Although retired, she continues to volunteer as a tutor at a neighborhood elementary school and is active in her church. Her HASP is displayed in Figure 4. Particularly noteworthy are her apprehensions about technology (< 10th

137

Journal of the American Academy of Audiology/Volume 12, Number 3, March 2001

A Satisfaction Rating B Satisfaction Rating

Overall Improves Clearness Improves Use in Noise Natural

`o

N

Satisfaction COL Hearing Sounding One-to-One Small Groups Large Groups Concert/Movie Restaurant Phone Satisfaction Items Listening Situations

Figure 3 The Knowles Satisfaction Survey for Case 1. A illustrates how satisfied the patient is for selected items. Note that "improves Quality of Life" (QOL) is rated on a 3-point scale rather than a 5-point scale. B illustrates satis-faction with specific listening conditions .

percentile), high communication needs (> 50th percentile), and active lifestyle (> 80th percentile) . Based on her profile, an initial clinical decision may be to avoid recommending "advanced technology" hear-ing aids . Following a brief discussion with the patient, it was ascertained that she was concerned with the use of remote controls or "gadgets" and not opposed to the use of newer signal processing strategies to improve her communication abilities. The patient was fit with binaural "mid-priced" two-channel DSP in-the-ear hearing aids . On postfitting testing, she had significantly reduced her self-perceived handicap and was very satisfied overall. Thus, a patient's apprehension of technology does not pre-

Motiv Expect Appear Cost Tech Phy Func Comm Lifestyle

HASP Subscales Needs

Figure 4 HASP for Case 2. This case illustrates how the HASP can be used for counseling with respect to specific issues . The patient demonstrated a low score for the Technology subscale, which might have resulted in a recommendation for a traditional product, yet, when her options were explained, the use of a specific type of higher level technology was found to be most appropriate for her. Motiv = Motivation, Expect = Expectation, Appear = Appearance, Tech = Technology, Phy Func = Physical Function, Comm Needs = Communicative Needs.

clude his or her use of advanced signal pro-cessing hearing aids . It is important to note that advanced technology hearing aids need to be assessed from two perspectives : hard-ware (e.g., remote controls, memory switches) and software (e.g., processing strategies and fitting rationales). For many individuals, the newer signal processing technology actu-ally offers a more simplified ("automatic") approach to hearing aid use in comparison with analog linear processing hearing aids requiring the use of a volume control.

Further, patient profiles may assist audiologists to better understand factors that may lead to the rejection of amplification. Consider the follow-ing two cases:

" Case 3 is a 78-year-old new hearing aid user with a bilateral, mild-moderate, high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss . She demonstrated a HHIE-S score of 24 points, suggesting a severe perceived hearing hand-icap . The HASP administered at the time of the HAS is shown in Figure 5 . The profile shows that the patient's score on the Moti-vation subscale fell below the 50th per-centile for the subject sample . The scores on the Technology subscale indicated that she appreciates the benefits of technology, and the results of the Physical Function sub-scale (5th percentile) indicate problems with manual dexterity. Further, scores on the Lifestyle subscale (below the 5th percentile) suggest that she lives a relatively inactive or sedentary life . The initial clinical decision was made to accommodate the reduced man-ual dexterity by selecting an amplification system that uses a remote control. This decision was supported by her appreciation of the benefits of technology. Therefore, she

138

Motiv Expect Appear Cost Tech Phy Func Comm Lifestyle Needs

HASP Subscales

Figure 5 HASP for Case 3 . Note that the Motivation subscale score falls between the 20th and 50th percentiles for the sample group. Whereas scores on the Technology subscale indicate that the patient appreciates the bene-fits of technology, scores on the Physical Function sub-scale (5th percentile) suggest that she has problems with finger/hand/arm mobility and scores on the Lifestyle subscale (below the 5th percentile) suggest that the patient lives a relatively inactive or sedentary life . Motiv = Motivation, Expect = Expectation, Appear = Appearance, Tech = Technology, Phy Func = Physical Function, Comm Needs = Communicative Needs.

0

was fit binaurally with a full-shell, hybrid analog/digital multichannel, multimemory product with a directional microphone and remote control ; however, her communication needs, lifestyle, and motivation did not sup-port the use of this system. It was not sur-prising that when she returned the hearing aids for credit during the right-to-return period, she commented that she stayed at home "99 percent of the time" and did not need the hearing aids . It might have been predicted at the outset that a patient with a sedentary lifestyle and with limited social interactions may have difficulty experienc-ing the benefits of a hybrid analog/digital multichannel, multimemory product with a directional microphone and remote control . Accordingly, follow-up intervention should include investigating the use of assistive listening devices for specific listening situ-ations in the home in order to reduce the self-perceived handicap, as indicated by the HHIE-S . Case 4 is an 82-year-old female with a bilat-eral, mild to severe, sloping sensorineural hearing impairment . Both the HASP and HHIE-S were administered prior to the HAS appointment . She scored 8 points on the HHIE-S, suggesting mild perceived hearing handicap . Her HASP is shown in Figure 6 .

Development of the HASP/Jacobson et al

Motiv Expect Appear Cost Tech Phy Func Comm Lifestyle Needs

HASP Subscales

Figure 6 HASP for Case 4. Note that all of the subscales are at or below the 50th percentile with the Physical, Com-municative Needs, and the Lifestyle subscales falling on or below the 5th percentile of the subject sample. Motiv = Motivation, Expect = Expectation, Appear = Appearance, Tech = Technology, Phy Func = Physical Function, Comm Needs = Communicative Needs.

Note that her score on the Motivation sub-scale falls far below the 50th percentile for our sample, as do her scores on the Expec-tations, Cost, and Technology subscales . Her score on the Physical Function sub-scale suggests that she has significant man-ual dexterity problems (< 5th percentile) . Also, scores on the Communicative Needs (5th percentile) and Lifestyle subscales (<5th percentile) suggest that she has an inactive lifestyle with limited social interactions . The limited communication interactions may account, in part, for the low score on the HHIE-S, reflecting minimal perceived hear-ing handicap . She further reported that she was at the clinic at the request of her daugh-ter and physician . Although this patient was a candidate for amplification based on her audiologic evaluation, the results from the HASP and the HHIE-S clearly suggested otherwise . The patient and audiologist were in accord that she was not ready to obtain amplification at this time .

In summary, it is our contention that the HASP has the potential to provide the dispensing audi-ologist with a number of practical benefits :

1 . Patient counseling : The HASP provides a quick and efficient means to assess patient motivation in obtaining amplification, their expectations of what a hearing aid will and will not do, and their degree of communi-cation needs as a function of their lifestyle . Additionally, the HASP provides insights

139

Journal of the American Academy of Audiology/Volume 12, Number 3, March 2001

into patients' beliefs and perceptions in other areas that may influence the selection of a particular hearing instrument . The information obtained from the HASP can then serve as a basis for counseling during the HAS. Based on the profile, specific areas can be queried for more in-depth under-standing-for example, the issue of appear-ance as illustrated in Case 1 or the fear of technology as in Case 2. Expectations can be assessed as realistically high or not. Inas-much as satisfaction represents the degree to which we are able to meet expectations, one might predict that patients having unre-alistic expectations will be dissatisfied when their hearing aids fail to meet those expec-tations . By appropriately assessing the patient's psychosocial factors a priori, selec-tion of the appropriate amplification sys-tem should be maximized-thus ultimately increasing patient satisfaction and reducing the rate of return for credit .

2. Clinician accountability : At present, there is little empirical evidence to support the rec-ommendation of a hearing aid for a partic-ular patient. Yet, there is a plethora of new technologies available to dispensing audi-ologists, and the task can seem over-whelming at times. Having a tool that directs the audiologist to a particular style, cost range, and/or level of technology, as can be obtained from the HASP, would not only be beneficial during the HAS but would also serve as justification to support the selection of a particular amplification system.

3. Method for developing a pool of suggested "first-choice" hearing aid types and styles : The HASP, along with other subjective (e.g ., COSI, HHIE-A) and objective measures (e.g., audiometry), may prove instrumental in developing an "expert clinician" algo-rithm that could generate a pool of "appro-priate" hearing aid fittings drawn from any manufacturer's product line. This is an excit-ing prospect, and the predictive accuracy of the tool needs to be investigated .

4. Teaching graduate students and clinical fel-lows : The use of the HASP forces students and clinicians to consider more than the audiogram when selecting hearing aids . In this regard, the HASP might serve as a good teaching tool when supervising novice clinicians .

5. Quality improvement projects document-ing multisite comparisons: The content of the

HASP makes it possible to ask questions per-tinent to whether there are differences in the perceptions of patients seen at multiple practice locations within the same system . For example, one author (GPJ) has evalu-ated the differences in responses of patients seen at seven Henry Ford Health System dispensing locations within the Detroit Met-ropolitan area. The results of this analysis suggested no differences in patient percep-tions regarding any of the HASP subscales despite the substantial differences in the socioeconomic characteristics of patients seen at some of the practice sites. In conclusion, we have developed a self-

report prefitting tool with the following char-acteristics : (1) it is brief so that patients can complete it within a reasonable time period either at home or in the office setting ; (2) it is easily administered and lends itself to either a paper-and-pencil or computer administration format ; (3) it can be used as a benchmark against which a hearing aid candidate's profile of responses can be compared against a larger sample of individuals seeking hearing aids ; and (4) it is broad in scope, assessing domains of function that are important in the selection of hearing aids .

Acknowledgment . The authors wish to thank the fol-lowing individuals without whose help these investiga-tions would not have been possible : Patricia Aldridge, MA, Lisa Bauer, AuD, Jaynee H. Calder, PhD, Nancy Damron, MA, William Dickinson, MA, Noreen D. Gibbens, MS, Lisa Lee, MA, Christine Paul, MA, Wendy Rizzo, MA, Ginnette Ruckel, AuD, Gail Sterling, MS, and Debra West, MA of the Henry Ford Health System ; Deborah Bucher, MA, Janet Fraser, MA, Ann Guzhauskas, MA, Julie Jones, MA, Lorrie Lombardo, MA, Richard Nodar, PhD, and Cynthia Wagner, MS, of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation ; and Jim McPherson, MA, and Melissa DeJong, MA, of the Mayo Clinic .

This manuscript was presented, in part, at the American Speech-Language Hearing Association meet-ing in San Francisco, CA, November 18-21, 1999 .

REFERENCES

Brooks DN, Hallam RS . (1998) . Attitudes to hearing dif-ficulty and hearing aids and the outcome of audiological rehabilitation . Br JAudiol 32:217-226 .

Cox RM, Alexander GC . (1995). The Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) . Ear Hear 16:176-186 .

Dillon H, James A, Ginis J. (1997) . Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids . J Am Acad Audiol 8:27-43 .

Dodds E, Harford E. (1982) . A community hearing con-servation program for senior citizens . Ear Hear 3:160-166 .

140

Development of the HASP/Jacobson et al

Dunkle RE, Kart CS . (1991) . Social aspects of aging and communication. In : Ripich DN, ed . Handbook of Geriatric Communication Disorders. Austin, Tx: Pro-Ed, 81-96.

Newman CW Sandridge SA. (1998) . Benefit from, satis-faction with, and cost-effectiveness of three different hearing aid technologies . Am JAudiol 7:115-128 .

Erdman SA, Demorest ME . (1998) . Adjustment to hear-ing impairment II : audiological and demographic correlates . J Speech Hear Res 41:123-136 .

Garstecki DC, Erler SF. (1996) . Older adult performance on the Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired. J Speech Hear Res 39:28-42 .

Garstecki DC, Erler SF. (1998) . Hearing loss, control, and demographic factors influencing hearing aid use among older adults . J Speech Hear Res 41:527-537 .

Gordon-Salant S, Lantz J, Fitzgibbons P. (1994) . Age effects on measures of hearing disability . Ear Hear 15 :262-265 .

Kochkin S. (1994x). MarkeTrak IV: impact on purchase intent of cosmetics, stigma, and style of hearing instru-ment . Hear J 47(9):1-7 .

Kochkin S. (1994b). MarkeTrak IV: will CICs attract a new type of customer-and what about price? Hear J 47(11) :49-54 .

Kochkin S . (1997) . MarkeTrak IV : what is the viable market for hearing aids? Hear J 50(1):31-38 .

Kochkin S. (1998) . Marke'Irak IV : correlates of hearing aid purchase intent . Hear J 51(1):30-38 .

Kocbkin S . (1999) . Marke`Irak V: "baby boomers" spur growth in potential market, but penetration rate declines . Hear J 52(1):33-48.

Mulrow CD, Aguilar C, Endicott JE, Tuley MR, Velez R, Charlip WS, Rhodes MC, Hill JA, DeNino LA. (1990) . Quality-of-life changes and hearing impairment : a ran-domized trial. Ann Intern Med 113:188-194 .

Newman CW, Weinstein BE, Jacobson GP, Hug GA. (1991) . Test-retest reliability of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults . Ear Hear 12:355-357 .

Ricketts T, Dhar S. (1999) . Comparison of performance across three directional hearing aids . J Am Acad Audiol 10 :180-189 .

Taylor KS . (1993) . Self-perceived and audiometric eval-uations of hearing aid benefit in the elderly. Ear Hear 14 :390-394 .

Valente M, Sammeth CA, Potts JL, Wynne MK, Wagner-Escobar M, Coughlin M. (1997) . Differences in performance between Oticon Multifocus Compact and ReSound BT2-E hearing aids . J Am Acad Audiol 8:280-293 .

van den Brink RH, Wit HP, Kempen GI, van Heuvelen MJ. (1996) . Attitude and help-seeking for hearing impair-ment . Br J Audiol 30:313-324 .

Walden BE, Demorest ME, Hepler EE . (1984) . Self-report approach to assessment benefit derived from amplifica-tion . J Speech Hear Res 27:49-56 .

Weinstein B. (1986) . Validity of a screening protocol for identifying elderly people with hearing problems . ASHA 28:41-45 .

Weinstein BE . (1996) . Treatment efficacy : hearing aids in the management of hearing loss in adults . J Speech Hear Res 39:S37-S45 .

Weinstein BE, Ventry IM . (1983) . Audiometric correla-tions of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly. J Speech Hear Disord 48:379-384 .