DEVELOPMENT OF PHARMACEUTICAL DISTRIBUTION MODEL...

Transcript of DEVELOPMENT OF PHARMACEUTICAL DISTRIBUTION MODEL...

1

DEVELOPMENT OF PHARMACEUTICAL DISTRIBUTION MODEL FOR CUSTOMER

SATISFACTION

Submitted by

Muhammad Usman Awan

in accordance with the requirement for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Abdul Raouf Co-Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Niaz Ahmad Akhtar

(May 2008)

Institute of Quality and Technology Management Faculty of Engineering and Technology

Quaid-e-Azam campus, University of the Punjab Lahore - Pakistan

2

THIS RESEARCH WORK HAS BEEN DONE IN COLLABORATION WITH

INSTITUTE FOR RETAIL STUDIES,

UNIVERSITY OF STIRLING, UK.

FOCAL PERSON FOR THIS COLLABORATION WAS PROFESSOR DR. LEIGH SPARKS

HIS CONTACT DETAILS ARE

Prof. Dr. Leigh Sparks Institute for Retail Studies

University of Stirling FK9 4LA, Stirling UK

0044 1786 467384 [email protected]

3

CERTIFICATE

This is to certify that the research work described in this thesis is the original work

of the author and has been carried out under our direct supervision. We have

personally gone through all the literature review, data and results reported in this

manuscript and certify their authenticity. We further certify that the material

included in this thesis have not been used in part or full in a manuscript already

submitted or in the process of submission in partial / complete fulfillment of the

award of any other degree from University of the Punjab or any other institution.

We also certify that the thesis has been prepared according to the prescribed format

of University of the Punjab and we endorse its evaluation for the award of Ph.D.

degree through the official procedures of the University of the Punjab.

Prof. Dr. Abdul Raouf (Supervisor)

Sitara-e-Imtiaz Distinguished National Professor of HEC

Patron Institute of Quality and Technology Management

University of the Punjab

Prof. Dr. Niaz Ahmad Akhtar (Co-Supervisor)

Director Institute of Quality and Technology Management

University of the Punjab

4

SUMMARY

There are two major concerns associated with customer satisfaction for companies

competing in present era of intense global competition. Companies have to increase

customer satisfaction by incorporating quality management in their strategic and long

term corporate plans. Similarly satisfaction of each member of the supply chain has to be

increased by developing closer partnership type arrangements (Christopher and Lee,

2004). In the development of such partnership type arrangements, service quality is an

important tool because the relationship of service quality with improved supply chain

performance is widely accepted (Mentzer et al., 1999, 2001; Perry and Sohal, 1999).

TQM is customer satisfaction based management philosophy. Previous studies in TQM

can be categorized along several main research objectives. These include identifying

critical TQM factors, examining issues and / or barriers in the implementation of TQM

and investigating the link between TQM factors and performance (Sebastianelli and

Tamimi, 2003). The objective of this research is related to the identification of TQM

critical success factors and then its relationship to customer satisfaction so the literature

related to TQM critical success factors and customer satisfaction is reviewed in detail in

this dissertation. It has also been concluded in this dissertation that service quality is an

antecedent of customer satisfaction.

However most of the previous research in TQM and service quality is based in developed

countries. This research is an effort to reduce the existing gap of developing countries

based TQM and service quality studies. The research is divided into two sections. In first

section, survey questionnaire obtained from 51 pharmaceutical distributors is used to

identify critical success factors of TQM. Relationship of TQM implementation to

customer satisfaction is also developed in this portion of research. Second portion of

research is related to development of service quality scale in distributors-retailers

interface of pharmaceutical supply chains. Data collected from 413 respondents was

analyzed. Structural equation modeling using AMOS 7.0 software developed a valid and

reliable scale comprising of 4 dimensions and 10 items. This research has practical

implications for pharmaceutical distribution companies as it identifies that top

5

management has to increase its commitment for the implementation of TQM. Research

also develops a reliable and valid scale that can be used by to increase service quality in

distributors-retailers interface of pharmaceutical supply chains in Pakistan.

6

DEDICATED TO

My Parents (Zahoor-ud-din and Shahida Bano), Wife

(Rizwana) and Daughter (Maryam)

7

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All praises are for Allah Almighty, who created human beings and gave knowledge, and

provided me an opportunity to complete this research work for my Ph.D. studies.

I am grateful to my Supervisors, Prof. Dr. Abdul Raouf and Prof. Dr. Niaz Ahmad; as

without their kind guidance throughout this project, it was not possible for me to

complete it in stipulated time.

Special thanks and appreciation to Prof. Dr. Leigh Sparks, Institute for Retail Studies,

University of Stirling, UK for providing me intellectual guidance during my one year stay

at University of Stirling. Prof. Sparks not only guided me in analyzing the experimental

data but also spent a lot of time in brushing up all chapters of my dissertation. Prof.

Sparks provided me an opportunity to work with other Ph.D. students at University of

Stirling. I am highly indebted to Mr. Abraham Brown (a Ph.D. student at University of

Stirling) for helping me about the various statistical soft-wares used in my research. Mr.

Andrew Paddision (a senior lecturer at University of Stirling) helped me a lot when I was

writing the methodology chapter.

I really acknowledge the support of my friends Mr. Atif Shahbaz (Lecturer in Physics,

Government College University, Lahore) and Syed Atif Raza (Assistant Professor in

College of Pharmacy, University of the Punjab, Lahore) who encouraged me to enter in

Ph.D. program. Thanks are also due to my teachers who taught the Ph.D. course work. I

can not forget the time I passed with my beloved Ph.D. class fellow Colonel (retd) Latif

Aleem (late). May his soul rest in heaven (Amin). Colonel Aleem I really miss you a lot.

I particularly wish to thank Mr. Thomas Josef Steffen from Ms Schering Asia GmBH,

Mr. Najeeb-ur-rehman from Ms Muller and Phipps Pakistan and Mr. Tariq from Ms

Paramount distributors. It was not possible for me to complete field work of my research

with out their generous support. I would also like to acknowledge Mr. Muhammad

Khalid Khan, Mr. Muhammad Asif, Mr. Muhammad Abid Umer, Mr. Moazam Javed and

Mr. Muhammad Isteqar (staff members of my University) for their efforts and help,

8

which they provided me during my research work. Financial support from Higher

Education Commission, Government of Pakistan during the whole period of my Ph.D.

study is also highly acknowledged.

Last, but certainly not least, I would like to thank my family members. My parents pray

for me at each step in my life and allowed me to stay one year away from my home (at

University of Stirling, UK) for the first time in my life. My wife promised me four years

ago when we married that she would always “support my endeavours” and time since

than has been proof of her commitment.

9

ABBREVIATIONS

Total Quality Management TQM

Will Expectation WE

Should Expectation SE

Delivered Service DS

Perceived Service PS

Overall Perceived Service OSQ

Behavioral Intentions BI

Analysis of Moment Structure AMOS

Linear Structural Relations LISREL

Confirmatory Factor Analysis CFA

Comparative Fit Index CFI

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation RMSEA

Goodness of Fit Index GFI

Normed Fit Index NFI

Top Management Support TMS

Strategic Planning Process in Quality Management SPPQM

Quality Information Availability and Usage QIAU

Employee Training ET

Employee Involvement EI

Process Design PD

Supplier Quality SQ

Customer Orientation CFS

Bench Marking BM

Results of Implementing Quality Management RIQM

10

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE Page No.

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION 14 - 19 1.1. Research Problem 14 1.2. Purpose of the research 15 1.3. Significance of this Research 16 1.4. Structure of the thesis 18CHAPTER 2 – TQM, CUSTOMER SATISFACTION AND SERVICE QUALITY

20 - 39

2.1. Total Quality Management (TQM) 20 2.2. Critical Success Factors of TQM 22 2.2.1. TQM in Developing Countries 25 2.3. Customer Satisfaction 28 2.4. Service Quality 31 2.4.1 Models of Service Quality 31 2.5. Summary of the Chapter 38CHAPTER 3 – SERVICE QUALITY DIMENSIONS AND SERVICE QUALITY IN SUPPLY CHAINS

40 – 51

3.1. Service Quality Dimensions 40 3.2. Service Quality in Supply Chains 45 3.3. Pharmaceutical Sector of Pakistan 48 3.4. Summary of the Chapter 50CHAPTER 4 – METHODOLOGY 52 – 70 4.1. Research Questions 52

4.2. Research Strategy and Data Collection Methods 53 4.3. Selection and Refinement of the Questionnaires 57

4.3.1. Selection and Refinement of the Questionnaire (Research Questions 1 and 2)

57

4.3.1.1. Development of Theoretical Framework for Analysis

62

4.3.1.2. Sampling 654.3.2. Selection and Refinement of the Questionnaire (Research

Question 3) 66

4.3.2.1. Development of Theoretical Framework for Analysis

68

4.3.2.2 Sampling 70CHAPTER 5 – ANALYSIS OF TQM SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE 71 - 86 5.1. Scale Purification 71 5.2. Correlation Analysis 78 5.3. Regression Analysis 80 5.3.1. Regression when CFS is Dependent Variable 81 5.3.1.1. Stepwise Regression when CFS is Dependent 82

11

Variable 5.3.1.2. Summary of results when CFS is Dependent Variable

83

5.3.2. Regression when RIQM is Dependent Variable 845.3.2.1. Stepwise Regression when RIQM is Dependent

Variable 85

5.3.2.2. Summary of Result when RIQM is Dependent Variable

86

CHAPTER 6 – ANALYSIS OF SERVICE QUALITY SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE

87– 93

6.1. Scale Purification 87CHAPTER 7 – DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION 94– 98 7.1. Discussion / Conclusion of TQM Survey Questionnaire Results 94

7.2. Discussion / Conclusion of Service Quality Survey Questionnaire Results

96

7.3. Limitation and Suggestions for Future Research 97REFERENCES 99-109 APPENDICES 110-119 Appendix A: Rao et al., (1999) Questionnaire 110 Appendix B: Refined (TQM) Questionnaire Used in this Research 113 Appendix C: Cover Letter Send to Pharmaceutical Distributors 115 Appendix D: Parasuraman et al., (1988) Service Quality Dimensions and Items

116

Appendix E: Service Quality Questionnaire Items (Along with Dimensions and Abbreviations used in Analysis)

117

Appendix F: Cover Letter Send to Pharmaceutical Retailers 119

12

LIST OF FIGURES Title Page No. Figure 1.1 Structure of the thesis 19 Figure 2.1 Components of TQM philosophy and their

interrelationships 21

Figure 2.2 The Gronroos service quality model 32 Figure 2.3 Parasuraman et al., (1985) Service Quality Model 34 Figure 2.4 Parasuraman et al., (1988) Servqual Model 35 Figure 2.5 Boulding et al., (1993) A Dynamic Process of Service

Quality 37

Figure 2.6 Zeithaml et al., (1996) The Behavioral and Financial Consequences of Service Quality

38

Figure 3.1 Supply Chains Process Quality Model 45 Figure 4.1 Theoretical Framework for Regression Analysis on

Dependent Variable (CFS) 64

Figure 4.2 Theoretical Framework for Regression Analysis on Dependent Variable (RIQM)

65

Figure 4.3 Theoretical Framework for Development of Service Quality Scale

69

Figure 5.1 Framework for CFS 83 Figure 5.2 Framework for RIQM 86 Figure 6.1 CFA Model Development Using AMOS 7.0 89

13

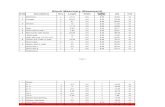

LIST OF TABLES

Title Page No. Table 1 Components of Various TQM Evaluation Models 22 Table 2 25 TQM critical success factors extracted from survey

based research 23

Table 3 14 “Vital Few” TQM Factors 24 Table 4 Attributes of Service Quality 43 Table 5 Comparison of Various TQM Measurement Instruments 58 Table 6 Comparison of RAO et al., (1999) Questionnaire and

Refined Questionnaire 62

Table 7 Summary of Goodness of Fit Statistics for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

74

Table 8 Reliability Analysis 76 Table 9 Item to Total Correlations 76 Table 10 Convergent and Discriminant Validity 78 Table 11 Correlation Among all Variables 79 Table 12 Correlation Among Variables Excluding CFS 80 Table 13 Variables Entered / Removed (b) 81 Table 14 Model Summary 81 Table 15 ANOVA (b) 81 Table 16 Coefficients (a) 81 Table 17 Variables Entered / Removed (a) 82 Table 18 Model Summary 82 Table 19 ANOVA (b) 82 Table 20 Coefficients (a) 82 Table 21 Variables Entered / Removed (b) 84 Table 22 Model Summary 84 Table 23 ANOVA (b) 84 Table 24 Coefficients (a) 84 Table 25 Variables Entered / Removed (a) 85 Table 26 Model Summary 85 Table 27 ANOVA (b) 85 Table 28 Coefficients (a) 85 Table 29 Sequence Wise List of Deleted Items 88 Table 30 Reliability Analysis 90 Table 31 Item to Total Correlations 91 Table 32 Correlation Among all Dimensions Emerged 92 Table 33 Dimensions and Items Constituting the Developed Scale 93

14

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION

The inspiration for this research comes from my previous experiences. As quality

management officer in a pharmaceutical company, I was responsible for implementing

quality management principles of parent company Ms Schering AG, Germany in a

pharmaceutical company located in Lahore - Pakistan. I always realized that because of

culture, level of technical advancement, national corporate business practices, state

legislation and many other factors, “one size does not fit all” so it was not possible to

implement quality management practices exactly in a way these were implemented in Ms

Schering AG, Germany. Later, my experience as lecturer at University of the Punjab

developed my interest in the subject of supply chain management. The blend of these

experiences focused my attention on quality management in pharmaceutical supply

chains. Preliminary literature review gave me marvelous knowledge about both these

subjects (quality management and supply chain management). However I realized that in

both subjects there is little work done in context of developing countries. This research is

an effort to reduce this gap in addition to provide an insight to pharmaceutical

distribution companies about TQM implementation and to satisfy their customers by

providing better service quality. This chapter introduces the problem, purpose and

significance of the research. At the end of the chapter is summary of the arrangement of

the thesis.

1.1: RESEARCH PROBLEM

Quality is a prerequisite for the survival of any business and firms should continuously

aim to delight customers (Khamalah and Lingaraj, 2007). TQM development is the result

of this intense global competition and companies with international trade and global

competition have paid considerable attention to TQM philosophies, procedures, tools and

techniques (Mahour, 2006). Karuppusami and Gandinathan (2006) have defined TQM as

an integrative management philosophy aimed at continuously improving quality and

process to achieve customer satisfaction. The TQM studies have been carried out in three

different ways: contributions from quality leaders (e.g. Crosby, Deming, Ishikawa, Juran

and Feigenbaum), formal evaluation models e.g. European Quality Award (EQA),

15

Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA), the Deming Award and empirical

research (Claver et al. 2003). However according to Rao et al., (1997) and Al-Khalifa

and Aspinwall (2000), most TQM studies have focused on organizations in developed

countries and there is lack of information about the nature and stage of TQM

implementation in developing countries. Thiagarajan et al. (2001) argue that the scant

attention given to research in the developed nations, complicated by the acknowledged

limitations of transferring research findings across national boundaries, has made efforts

to learn and transfer empirically sound knowledge to developing economies all the more

difficult. It is important therefore to create specific TQM knowledge focused on the

particular requirements of developing countries. This research is an attempt to remedy a

small part of this lack of information about TQM implementation in developing

countries. This research also reduces the existing lack of supply chain specific service

quality studies. The objective of this research is therefore twofold. Firstly, there is a

question on the relationship of TQM to customer satisfaction in pharmaceutical

distribution companies in Pakistan (a developing country). This portion of research also

identifies critical success factors of TQM in pharmaceutical distribution companies in

Pakistan. Second portion of the research is about the development of service quality scale

in distributors-retailers interface of pharmaceutical supply chains in Pakistan.

1.2: PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH

The purpose of this research is to develop pharmaceutical distribution model for customer

satisfaction. This can be achieved only by obtaining quantitative results from a sample of

both internal and external customers of pharmaceutical distribution companies.

Quantitative research questions related to the internal customers address the effect of

TQM practices on customer satisfaction. Subsequently, this portion of research attempts

to identify critical success factors of TQM implementation in pharmaceutical distribution

companies. The research questions related to the internal customers for this research are

therefore:

1) Does TQM implementation relate directly to the customer satisfaction in

pharmaceutical distribution companies in Pakistan?

16

2) What are the critical success factors of TQM in pharmaceutical distribution

companies in Pakistan?

Pharmaceutical retailers are the external customers of pharmaceutical distribution

companies so it is important for pharmaceutical distribution companies to know that how

they can satisfy them. This can be done by knowing:

3) Which are the important service quality dimensions and items in the distributors-

retailers interface of pharmaceutical supply chains in Pakistan?

1.3: SIGNIFICANCE OF THIS RESEARCH

Most of the TQM related research cited in the literature is based on research in developed

countries (Rao et al. 1999). Quality gurus presented their ideas on the basis of their

individual experiences in developed countries. Formal evaluation models of TQM are

developed for companies operating primarily in the United States of America, Europe

and Japan. The demand for TQM can however no longer be the prerogative of the

developed world only. Some of the developing countries are breaking through traditional

trade barriers and open their markets to international competitors (Temtime and Solomon,

2002). TQM is thus becoming more significant in developing countries also. There is still

lack of information however about the nature and stage of implementation of TQM in

countries in some largely developing regions of the world including Asia, South America,

Africa and the Middle East (Sila and Ebrahimpour, 2003). The first aim of this research

is to reduce this lack of information about TQM in developing countries.

It is also the fact that in today’s global marketplace, individual firms no longer compete

as independent entities but compete as an integral part of supply chain links (Seth et al.

2006). Christopher (1992) also argued that a key aspect of business is that supply chains

compete, not companies. According to Waters (2003), organizations do not work in

isolation; they act as a customer when buy materials from their own suppliers and act as a

supplier when they deliver materials to their own customers. A wholesaler for example

acts as a customer when buying goods from manufacturers, and then acts as a supplier

when selling goods to retailers. It is important to satisfy each member of the supply

chain. There is a change in the landscape of supply chain management in recent years and

17

satisfaction of each member of the supply chain can be increased only by putting aside

the traditional arms-length relationship and by developing closer partnership type

arrangements (Christopher and Lee, 2004). In the development of such partnership type

arrangements, service quality is an important tool because the relationship of service

quality with improved supply chain performance is widely accepted (Mentzer et al.,

1999, 2001; Perry and Sohal, 1999). Regardless of this universal recognition for

realizing the importance of service quality in supply chains, it is little researched

(Nix, 2001). Most of the previous service quality research has been aimed at the end-use

customer (Faulds and Mangold, 1995; Perry and Sohal, 1999). There have been very few

studies on the development of service quality measurement scales in supply chains

(Beinstock et al. 1997; Mentzer et al. 1999, Rafele, 2004). These few studies are also

confined to specific sectors and are based in developed countries. Generalization of

findings of these studies in the global economy is not possible without further empirical

research (Rafele, 2004).

The second aim of this research is to reduce this research gap as this research is also

focused on service quality scale development at the distributors-retailers interface of

the pharmaceutical supply chains in a developing country. The author could find no

studies on the identification of critical success factors of TQM all sorts of companies in

Pakistan. Also little work has been done to examine the applicability of service quality

measurement scales to the service industries in developing countries (Jain and Gupta,

2004) and author of this thesis could find no studies on the development of supply chain

specific service quality measurement scale studies in any of the developing countries.

The pharmaceutical distribution sector was chosen as the object of the portion of research

related to TQM implementation because of its sectoral importance. No previous TQM

studies either in developed or developing countries appear to have focused on the

pharmaceutical distribution sector. Pharmaceutical supply chains are chosen as the object

of the portion of research related to service quality. Pharmaceutical supply chains also do

not appear in previous supply chains specific service quality measurement scale

development studies. The distributors-retailers interface is chosen as it has many non-

contractual dimensions in contrast to the manufacturers-distributors interface of supply

18

chains, which is frequently characterized by contractual agreements (Mangold and

Faulds, 1993).

This research will therefore contribute significantly to reduce the existing lack of TQM

and service quality studies in developing countries. This research will develop customer

satisfaction model for pharmaceutical distribution companies keeping in view the

requirements of external customers. As TQM implementation also helps to increase

customer satisfaction, the research will identify the relation of TQM to customer

satisfaction in pharmaceutical distribution companies. Critical success factors for TQM

implementation in pharmaceutical distribution companies in Pakistan are also identified

in this research.

1.4: STRUCTURE OF THE THESIS

Introduction, literature review, methodology, findings, discussion and conclusion are

components of this thesis. The first section introduces the problem, purpose and

significance of this research. The second section includes two chapters that intend to scan

past researches. Literature review helps to clarify the research objectives and provides a

theoretical framework that facilitates to define research problems and questions in section

three. Both chapters in literature review section have very different themes but are

connected in order to generate the framework to develop pharmaceutical distribution

model for customer satisfaction. Chapter two examines the philosophy of TQM and its

relationship with customer satisfaction. Critical success factors of TQM and

implementation of TQM in developing countries are discussed in detail. An effort has

been made to understand what customer satisfaction really is and how it can be achieved

by improving service quality. Literature related to various service quality models is also

discussed in this chapter. Third chapter is about the literature related to service quality

dimensions and service quality in supply chains. Context of the research is also described

in chapter three. The methodology, which is the third section of the thesis, is in chapter

four. At the start of this chapter research problems are defined and research questions are

identified. Decisions on the research approach for both portions of research are also made

in this chapter. Fourth section includes two chapters i.e. chapter five and six. Chapter five

is about the findings obtained from the portion of research related to TQM

19

implementation in pharmaceutical distribution companies. Findings obtained from the

portion of research related to development of service quality scale in distributors-retailers

interface of pharmaceutical supply chains is in chapter six. The eventual aim of chapter

seven (fifth section) is to bring the findings analyzed in chapter five and six to answer the

research questions of this research. In this chapter the implications of the research are

concluded, limitations of the research are presented and suggestions for future research

are made. The structure of this thesis is therefore close to the “linear-analytic structure”

proposed by Yin (1994) and can be illustrated as:

FIGURE 1.1: STRUCTURE OF THE THESIS

Section 1 Introduction

Chapter 1

Section 2 Literature Review

Chapter 2 – 3

Section 3 Methodology

Chapter 4

Section 4 Findings

Chapter 5 –6

Section 5 Discussion and conclusion

Chapter 7

References & Appendices

20

CHAPTER 2 – TQM, CUSTOMER SATISFACTION AND SERVICE QUALITY

In this chapter the literature related to TQM, customer satisfaction and service quality is

reviewed in detail with the objective to explore the relationship between these three fields

of research. Section 2.1 identifies customer focus as the core component of TQM

philosophy. The primary research is based in a developing country (Pakistan) so literature

related to critical success factors of TQM in context of developing countries is discussed

in detail in section 2.2. Literature related to the concept of customer satisfaction is

reviewed in section 2.3. Because service quality is a major determinant of customer

satisfaction, service quality models constitute the major portion of section 2.4.

2.1: TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT (TQM) In 1949 JUSE (Union of Japanese Scientists and Engineers) formed a committee of

scholars, engineers and government officials devoted to improve productivity and

postwar quality of life in Japan (Kanji, 1990). This step is historically considered as the

origin of TQM philosophy (Mahour 2006). This management philosophy was confined to

Japan until the early 1980s. It became international when previously unchallenged

American industries lost substantial market share in both American and world markets.

To regain the competitive edge, American companies began to adopt productivity

improvement programs, which had proven themselves successful in other developed

countries. One of these “improvement programs” was TQM. Since then, both the popular

press and academic journals have published a plethora of accounts describing both

successful and unsuccessful efforts at implementing TQM (Kaynak 2003).

According to Fynes and Voss (2002), one of the most problematic issues confronting

researchers in quality management is the search for an appropriate definition. There is no

consensus on the definition of TQM (Reed et al. 1996) as different people define it

differently. ISO 8402:1994 defines TQM as: “Management approach of an organization

centered on quality, based on the participation of all its members and aiming at long-term

success through customer satisfaction and benefits to all members of the organization and

to society”. Ugboro and Obeng (2000) also concluded that TQM is an approach used in

21

directing organizational efforts toward the goal of customer satisfaction. Khan (2003)

proposed a philosophy of TQM on the basis of four tenets and suggested that the absolute

customer focus is the core component of TQM philosophy. Other tenets of this

philosophy are employee empowerment, involvement and development, continuous

improvement and use of systematic approach to management (figure 2.1). Figure 2.1

shows that absolute customer focus is the core component of TQM philosophy.

FIGURE 2.1: COMPONENTS OF TQM PHILOSOPHY AND THEIR

INTERRELATIONSHIPS

Source: Khan (2003) Previous studies in TQM can be categorized along several main research objectives.

These include identifying critical TQM factors, examining issues and / or barriers in the

implementation of TQM and investigating the link between TQM factors and

performance (Sebastianelli and Tamimi, 2003). The objective of this research is related to

the identification of TQM critical success factors and then its relationship to customer

EMPLOYEE EMPOWERMENT, INVOLVEMENT

AND DEVELOPMENT

ABSOLUTE CUSTOMER

FOCUS

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

USE OF SYSTEMATIC

APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT

22

satisfaction so the literature related to TQM critical success factors and customer

satisfaction is reviewed in next sections (2.2 and 2.3). However because the research is

based in a developing country (Pakistan), problems in implementing TQM in developing

countries are also discussed (subsection 2.2.1).

2.2: CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS OF TQM Various studies have been carried out attempting to identify critical success factors of

TQM. They tend to emphasize three different areas (Tari, 2005; Claver et al., 2003) i.e.

contribution from quality leaders, formal evaluation models and empirical research. Dale

(1999) identifies management leadership, training, employee’s participation, process

management, planning and quality measures for continuous improvement as consistent

findings in the work of quality leaders such as Crosby, Deming, Juran, Ishikawa and

Feigenbaum. The Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA), European

Quality Award (EQA) and Deming application prize are common formal TQM

evaluation models used in the United States of America, Europe and Japan respectively.

The main components of these awards are summarized in Table 1. Leadership is the top

component of two of these awards.

TABLE 1: COMPONENTS OF VARIOUS TQM EVALUATION MODELS MBNQA EQA Deming Application Prize

Leadership Strategic Planning Human resources - orientation Process management Information and -analysis Customer and market -focus Business results

Leadership Employee management Policy and strategy Alliances and resources Process management People results Customer results Society results Key results

Policies Organization Information Standardization Development and usage of human -resources Activities ensuring quality Activities for maintenance and control Activities for improvement, result and future plans

Source: Tari (2005) According to Karuppusami and Gandhinathan (2006), Sila and Ebrahimpour (2005) and

Sebastianelli and Tamimi (2003), the research by Saraph et al. (1989) was the first

23

empirical research, which focused on the operationalization of TQM through the

identification of critical success factors. Since then the factors that determine success

and/or failure in TQM have attracted the attention of many researchers (Najeh and Kara-

Zaitri, 2007). Among these, studies by Sila and Ebrahimpour (2002, 2003), and

Karuppusami and Gandhinathan (2006) are significant because these researchers

summarize previous research in a systematic manner.

Sila and Ebrahimpour (2002) reviewed 347 survey based TQM studies published

between 1989 to 2000 and determined that during this period 76 studies in 23 countries

focused on the identification of TQM critical success factors. Sila and Ebrahimpour

(2002) used factor analysis to identify the 25 most commonly extracted TQM critical

success factors from these 76 studies. These factors are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2: 25 TQM CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS EXTRACTED FROM SURVEY BASED RESEARCH Sr. No. FACTORS

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20 21. 22. 23. 24.

Top management commitment Social responsibility Strategic planning Customer focus and satisfaction Quality information and performance Bench marking Human resources management Training Employee involvement Employee empowerment Employee satisfaction Team work Employee appraisal-rewards and recognition Process management Process control Product/service design Supplier management Continuous improvement Quality assurance Zero defects Quality culture Communication Quality systems Just-in-time

24

Sr. No. FACTORS 25. Flexibility

Source: Sila snd Ebrahimpour (2002) Sila and Ebrahimpour (2003) extended their previous research and analyzed and

compared these 25 factors across studies in 23 countries. They found that top

management commitment was the critical success factor covered in each country

included in the research.

Karuppusami and Gandhinathan (2006) used 37 TQM scale development studies

published between 1989 and 2003 to identify 56 critical success factors of TQM. They

selected these studies because the reliability and validity of the critical success factors

were statistically tested during these studies. On the basis of Pareto analysis,

Karuppusami and Gandhinathan (2006) sorted these 56 critical success factors in

descending order and divided them into two groups entitled “vital few” and “useful

many”. In the “vital few” group 14 factors accounted for 80% of the critical success

factors of TQM while the remaining 42 “useful many” factors accounted for 20% of

occurrences frequency only. The 14 factors identified as the “vital few” are given in

Table 3. Karuppusami and Gandhinathan (2006) also confirmed the finding of Sila &

Ebrahimpour (2003) that top management commitment is the most critical success factor

for TQM.

TABLE 3: 14 “VITAL FEW” TQM FACTORS Sr. No. Factors

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13.

Top management commitment Supplier management Process management Customer focus Training Employee relations Product / service design Quality data Role of quality department Human resource management and development Design and conformance Cross functional quality teams Bench marking

25

14. Information and analysis Source: Karuppusami and Gandhinathan (2006) This brief review of literature related to critical success factors of TQM therefore

suggests that top management / leadership support is overall the most common, important

and critical success factor in the implementation of TQM.

However most of the previous research in TQM cited in the review papers above is based

on research in developed countries. Quality gurus presented their ideas on the basis of

their individual experiences in developed countries. Formal evaluation models of TQM

are developed for companies operating primarily in the United States of America, Europe

and Japan. This research is based in a developing country (Pakistan) so it is essential to

identify the role of top management in previous TQM studies in developing countries.

Next subsection of this chapter is therefore about TQM implementation in developing

countries.

2.2.1: TQM IN DEVELOPING COUNTIRES Most of the developing countries have unique characteristics like lack of democracy,

instability, corruption, shortage of skilled labour force and raw materials, under

utilization of available production capacity, the inferiority and lack of quality standards,

high scrap, low purchasing power of customers, inadequate consumers know how, lack of

balance between import and export, foreign exchange constraints, incomplete

infrastructure etc. (Curry and Kadasah; 2002, Madu, 1997; Mersha, 1997) so the term

“poor quality” is synonymous with the products manufactured in these countries

(Mohanty and Lakhe, 2004). However, some of the developing countries are breaking

the traditional trade barriers and opening their markets to international competitors, so the

demand for quality can no longer be the prerogative of the developed world (Temtime

and Solomon, 2002). Speaking at Pakistan’s first convention on quality, quality guru

Crosby stated that nothing is more important to the prosperity of a developing nation than

quality. The only way a developing nation can increase its trade activities and develop a

sustainable basis is to improve the quality of its products and services (Djerdjour and

Patel, 2000).

26

According to Thiagarajan et al. (2001), while TQM in the West lacks theoretical support,

knowledge of in developing economies is almost totally lacking. The scant attention

given to research in the developed nations, confused by the acknowledged limitations of

most of the research findings across national boundaries, has made any efforts to readily

learn and transfer empirically sound knowledge to developing economies all the more

difficult. It is therefore, important to create TQM knowledge base keeping in view the

specific requirements of the developing countries as most of studies on quality

management practices have focused on developed countries only (Rao et al., 1997; Al-

Khalifa and Aspinwall, 2000) and there is still some lack of information about the nature

and stage of TQM implementation in some regions of the world such as Asia, South

America, Africa and the Middle East (Sila and Ebrahimpour, 2003). This research is an

attempt to reduce this lack of information about TQM implementation in developing

countries.

Mahour (2006) identified training and culture as two important barriers in implementing

TQM in developing countries. Literature review in the previous section concluded

that top management support is the critical success factor of TQM implementation

so in the following paragraphs these three factors (top management support,

employee training and culture are discussed with reference to developing countries.

Top management in developing countries is mostly not committed to quality initiatives

and is reluctant to delegate authority (Djerdjour and Patel, 2002). Studies (Al-Khalifah

and Aspinwall, 2000; Temtime and Solomon, 2002, Mersha, 1997) further indicate top

management support is the critical barrier in implementing TQM in developing countries.

Kaplinsky (1995) identifies reasons for lack of top management support for TQM in

developing countries and conclude that in developing countries, many enterprises are

family-owned and corporate growth and effective management are constrained by the

reluctance of the family to devolve responsibility to professionally trained outsiders.

A second critical barrier in implementation of TQM in developing countries is a cultural

change. Bruun and Mefford (1996) recommend that TQM programs in developing

27

countries should be accompanied by changes in organizational culture as programs that

are highly successful in the industrialized developed countries often fail in the developing

countries because these programs are uncritically adopted without any regard to their

congruence with the internal work culture of developing countries (Mendonca and

Kanungo, 1996). Yong and Wilkinson (1999) examine cultural issue with in the quality

management context from a human resource perspective and argue that “ Even in

culturally homogenous societies, the issue of cultural change plays a key role in

determining the success of quality management implementation, but because of the

competitive push for the adoption of TQM and the pervasiveness of prescriptive market

driven consultancy packages, managers have already neglected to tailor quality initiatives

to suit their own organizational cultures. Madu (1997) argues that as multinational

corporations have adopted strategies that work well with in the confines of developing

economies cultures, developing countries have to tailor quality management practices

according to their own culture, as issue is not whether quality management practices

should be adopted but how to implement these practices.

Another important concern about TQM implementation in developing Islamic countries

like Pakistan is that TQM is alien, not relevant to Islamic cultural and religious norms.

Khan (2001) criticizes those who advocate this judgment and argues that there are several

Ahadis (sayings of Prophet Muhammad P.B.U.H.) relating to ‘selling of goods,’ which

highlight the responsibility of the seller to explain all the shortcomings of the product

explicitly so as to adjust the buyer’s expectations to the appropriate level. After a clear

understanding of all the weaknesses of the product, when the buyer experiences the actual

product, he would, at the minimum, be satisfied if not delighted. Islamic norms of

business transactions insist on ensuring customer satisfaction that is also the core

component of the TQM philosophy. Therefore, it is incorrect to say that the TQM

philosophy is alien to Islamic cultural or religious norms and that it would not be

applicable in an Islamic country like Pakistan.

The third important factor affecting systemic adoption of TQM is employee training and

education as TQM demands a high degree of involvement of all employees and this

requires that all employees in the firm receive enough education and training (Gonzalez

28

and Guillen, 2002). According to Madu (1997), if the people of developing economies

are better trained and educated, they will be more able to contribute to planning their

future and the future of their companies but training infrastructure in these countries is

frequently underdeveloped and teaching techniques are still modeled on the now-outdated

managerial practices of mass production (Kaplinsky, 1995).

The important question is who can effectively change the culture and allocate sufficient

resources for employee education and training? Implementing quality management

requires a change of organizational culture and effective leadership is needed to be able

to transform the organization in a way that change may become acceptable. Similarly in

the perspective of culture, it is the responsibility of management to develop training

programs and enrich the knowledge of workers to understand the need for behavioral

modifications in order to adopt quality management (Madu, 1997). Therefore it may be

concluded that if top management is working effectively, other barriers in the

implementation can be over come and lack of top management support is the major

barrier in implementation of TQM in developing countries. This conclusion fortifies the

conclusion drawn in section 2.2.1 that top management support is the most critical

success factor of TQM.

2.3: CUSTOMER SATISFACTION The word “satisfaction” is formed combining Latin words satis (enough) and facere (to

do or make) (Rust et al. 1996). Since the mid-1980s, when quality management became a

widely practiced way to improve product quality, reduce costs and improve customer

service, the issue of customer satisfaction has brought about a great deal of ongoing

debate (Gustafsson and Johnson, 2004; Wirtz and Lee, 2003).

The definition of satisfaction also shows a strong heterogeneity (Florence et al. 2006).

Different authors have defined satisfaction in different ways but Giese and Cote (2000)

found that three overall components within virtually every definition of satisfaction might

be identified as these capture the specifics of the concept. These components are

* A response (affective or cognitive).

29

* The response concerns a particular focus (e.g. expectations, product and

consumption experience).

* The response takes place at a particular point in time (e.g. after choice, after

transaction, after consumption, based on accumulated experience).

The primary thread of debate in the satisfaction literature nowadays is focused on the

nature of the cognitive and affective processes that result in the consumer’s state of mind

referenced to as satisfaction (Jaronski, 2004). The cognitive dimension is the set of

information individuals accumulate through direct or indirect experience where as the

affective dimension is positive or negative evaluation (Florence et al. 2006). According

to this stream of satisfaction research, Yi (1991) categorized customer satisfaction

definitions either as an evaluation process or as an outcome of evaluation process. Oliver

(1981), Yi (1991) and Fornell (1992) describe satisfaction as an evaluation process where

as Tse and Wilton (1988) describes satisfaction as an outcome of evaluation process.

Satisfaction as an evaluation process is based on the disconfirmation of expectations

paradigm. Consumers form expectations towards product/service performance and these

expectations later serve as standards against which actual product/service performance is

evaluated (Oliver, 1980; Churchill and Suprenant, 1982) so it is actually the comparison

of expectations and actual perceived performance that results either in confirmation or

disconfirmation. If expectations are met, confirmation takes place, otherwise

disconfirmation occurs. Disconfirmation may be positive (when perceptions exceed

expectations) or negative (when expectations exceed perceptions). Therefore satisfaction

is the result of confirmation and positive disconfirmation where as negative

disconfirmation guides to dissatisfaction. Use of the term “positive disconfirmation” was

confusing so Anderson and Sullivan (1993) adopted the term “affirmation” as a substitute

for the term “positive disconfirmation”.

The framework of customer satisfaction as an outcome of an evaluation process is based

on the satisfaction as states the paradigm developed by Oliver (1989). Oliver (1997) also

found that satisfaction relates to pleasurable emotions, those approaching excitement or

delight and tending toward contentment and relaxation; whereas dissatisfaction relates to

30

unpleasant, disappointing and angering emotions. Zeithaml and Bitner (2000) found that

satisfaction is related to relief. Studies by Folkes et al. (1987), Mooradian and Oliver

(1995) also investigated the relationship between satisfaction and emotion. These studies

documented that satisfaction is clearly related to affective evaluations and affective

evaluations are antecedents to satisfaction. Although cognitive states have some

influence on satisfaction, the concept is strongly related to affective states, or emotions

(Wicks, 2004).

Practically all research on customer satisfaction agrees that customer satisfaction is a key

component of economic success (Horvath, 2001). There are two different types of

evaluations of customer satisfaction from the economic psychology perspective. One is

transaction-specific satisfaction and the other is cumulative satisfaction (Johnson et al.,

1995). Satisfaction that occurs strictly at time of the service delivery is referred to as

transaction-specific satisfaction (Parasuraman et al., 1988; Bitner, 1990) whereas

cumulative satisfaction approach defines satisfaction as customer’s overall experience to

date with a product or service provider (Johnson and Fornell, 1991). Fornell et al. (1996)

argue that the cumulative satisfaction construct is better able to predict subsequent

behaviors and economic performance over a more transaction specific view because

customers make repurchase evaluations and decisions based on their purchase and

consumption experience to date, not just a particular transaction or episode (Johnson et

al., 2001).

The review of literature in this section concludes that satisfaction is mainly influenced by

affective states (emotions) and cumulative satisfaction has more vital role in economic

success of the companies as compared to the transaction specific satisfaction. The next

question is how to measure customer satisfaction?

Many experts concur that the most powerful competitive trend currently shaping

marketing and business strategy is service quality (Abdullah, 2006) because of its

apparent relationship to customer satisfaction (Bolton and Drew, 1991a). It has been a

long-standing debate in the literature whether service quality is an antecedent for

satisfaction or vice versa. Bitner (1990) and Bolton and Drew (1991b) suggest that

31

satisfaction is an antecedent of service quality. Zeithaml et al. (1993) used both terms as

synonymous because both use expectations and perceptions as key antecedent constructs

and both are related to the behavioral intentions, which affect financial success of the

business organizations. De Ryter et al. (1997) merged the concepts of service quality and

satisfaction in an integrative model and tested the model empirically. This model

concluded that satisfaction should be treated as a superordinate construct to service

quality as higher levels of service quality results in increased satisfaction. In this

research, the determinants of service quality are used as antecedents of customer

satisfaction. The following section therefore reviews literature about what service quality

is and how various authors conceptualize service quality concept.

2.4: SERVICE QUALITY Service quality has been a frequently studied topic in service marketing literature (Su et

al., 2008). Various definitions of service quality have been proposed in the past (Jain and

Gupta, 2004) although it is an elusive and abstract construct that is difficult to define and

measure (Cronin and Taylor, 1992). Different authors have defined it differently but most

widely accepted definitions are those proposed by Parasuraman et al., (1988) and Cronin

and Taylor (1992). Parasuraman et al., (1988) define service quality as the difference

between what the customer feels that a service provider should offer and his perception of

what the service provider actually offers. However Cronin and Taylor (1992) argue that

only perceptions of performance derive service quality and expectations have no value in

calculating service quality. The objective of literature review in subsection 2.3.1 is to

relate concept of service quality to financial success of the company via customer

satisfaction.

2.4.1: MODELS OF SERVICE QUALITY The model presented by Gronroos (1984) is considered as the first service quality model

(Wicks, 2004). In this model the author identified technical quality, functional quality

and image as dimensions of service quality (figure 2.2). Technical quality is defined as

“what the consumer receives as a result of interactions with a service firm” and functional

quality just “the way in which the technical quality is transferred” where as image is built

32

up by both technical and functional quality of service. Gronroos concluded that to

manage service quality, there must be no gap between the expected service and the

perceived service so the Gronroos also used the “Disconfirmation paradigm” used by

Oliver in 1980 in his classic model of customer satisfaction.

FIGURE 2.2: THE GRONROOS SERVICE QUALITY MODEL

On the foundations of model proposed by Gronroos, Parasuraman et al., (1985)

developed the gap model (figure 2.3) to measure the elements of service quality.

The various gaps envisaged in this Parasuraman et al., (1985) model (figure 2.3) are: Gap 1: Difference between consumers’ expectation and management’s perceptions of

those expectations, i.e. not knowing what consumers expect.

Gap 2: Difference between management’s perceptions of consumer’s expectations and

service quality specifications, i.e. improper service-quality standards.

Gap 3: Difference between service quality specifications and service actually delivered

i.e. the service performance gap.

Gap 4: Difference between service delivery and the communications to consumers about

service delivery, i.e. whether promises match delivery?

Perceived Service

Image

Technical Quality

Functional Quality

Expected Service

Perceived Service Quality

33

Gap 5: Difference between consumer’s expectation and perceived service. This gap

depends on size and direction of the above-mentioned four gaps. This gap constitutes the

theoretical basis of this gap model (commonly called SERVQUAL model) and states:

“The quality that a consumer perceives in a service is a function of the magnitude and

direction of the gap between expected service and perceived service” and mathematically

can be expressed as:

( )ijij

kj EPSQ −=∑= =1

where:

SQ = Overall service quality

k = number of attributes.

Pij = Performance perception of stimulus i with respect to attribute j.

Eij = Service quality expectation for attribute j that is the relevant norm for stimulus i.

34

FIGURE 2.3: PARASURAMAN ET AL., (1985) SERVICE QUALITY MODEL

Parasuraman et al., (1985) recognized reliability, responsiveness, competence, access,

courtesy, communication, credibility, security, understanding/knowing the customer and

tangibles as determinants of service quality. Subsequent work by Parasuraman et al.,

(1988) merged these determinants into the five-component 22-item scale known as

SERVQUAL (figure 2.4) on the basis of factor analysis (Cronin and Taylor, 1992).

Reliability, responsive and tangibles were retained as such as identified in 1985 whereas

communication, competence, credibility, courtesy and security merged as a construct

Word of Mouth Communications Personal Needs

Past Experience

Expected Service

Perceived Service

Service Delivery (including pre- and post-contacts)

Translation of Perceptions into Service

Quality Specs.

Management Perceptions of Consumer Expectations

External Communications to

Consumers

GAP5

GAP4

GAP3

GAP1

GAP2

CONSUMER

MARKETER

35

“assurance” where as access and understanding/knowing the customer merged to form

the construct empathy.

FIGURE 2.4: PARASURAMAN ET AL., (1988) SERVQUAL MODEL

Source: Cronin and Taylor (1992) Parasuraman et al., (1988) described these five dimensions as follow: Tangibility: Appearance of physical facilities, equipment and communication material

Reliability: Ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately

Responsiveness: Willingness to help customers and provide prompt service

Assurance: Knowledge and courtesy of the employees and their ability to convey trust

and confidence

Empathy: The caring and individualized attention, organization provides to its customers

For a number of years, the dominant operationalization of service quality has been

Parasuraman et al., (1988) SERVQUAL scale. The foundation of the measure rested on

the authors suggestion that service quality should be represented as the difference, or

‘‘gap,’’ between service expectations and actual service performance (i.e., the

disconfirmation paradigm) but Cronin and Taylor (1992) argue that, if service quality is

Reliability Responsiveness

Assurance Empathy

Perceived Service Quality

Tangibles

X1 X2 X3 X4 X10 X11 X12 X13 X14 X15 X16 X17 X5 X6 X7 X8 X9 X18 X19 X20 X21 X22

36

to be considered ‘‘similar to an attitude,’’ as proposed by Parasuraman et al., (1985,

1988), its operationalization could be better represented by an attitude-based

conceptualization. Therefore, they proposed that the expectations scale be discarded in

favor of a performance-only measure of service quality that they term SERVPERF

(Brady et al., 2002).

ijkj PSQ 1=∑=

where:

SQ = Overall service quality

k = number of attributes.

Pij = Performance perception of stimulus i with respect to attribute j.

The use of performance-only measures is suggested by a number of other studies

(Babakus and Boller, 1992; Boulding et al., 1993) though still there is no consensus that

which of the two scales (SERVQUAL or SERVPERF) is more suitable for service

quality measurement (Jain and Gupta, 2004).

Another major strategic implication in Parasuraman et al., (1988) model was proposed by

Boulding et al., (1993). Boulding et al., (1993) reported that firms can try either to

increase perceptions or lower expectations in their quest to increase overall service

quality. Boulding et al., (1993) concluded that although expectations directly do not

affect service quality, it does not mean that they have no effect at all. Boulding et al.,

(1993) classified expectations as “will expectations” (WE) and “should expectations”

(SE) and recommended that firms should manage customers “will expectations” (WE) up

and “should expectations” (SE) down if they want to increase customer perceptions of

overall service quality.

The second important contribution of Boulding et al., (1993) model is to link service

quality to behavioral intentions. Overall perceived service (OSQ)------Behavioral

intentions (BI) link of this model propose that overall perceived service quality is related

to the behavioral intentions of the customers.

37

FIGURE 2.5: BOULDING ET AL., (1993) A DYNAMIC PROCESS MODEL OF

SERVICE QUALITY

In this model WE = Will Expectation, SE = Should Expectation, DS = Delivered Service

PS = Perceived Service

OSQ = Overall Perceived Service

BI = Behavioral Intentions

Bitner (1990), Bolton and Drew (1991a,b), Cronin and Taylor (1994) and Venetis and

Ghauri (2004) also find that service quality has a positive impact on customer’s

behavioral intentions. Zeithaml et al., (1996) supported this relationship of perceived

service quality to behavioral intentions and concluded that behavior of the customers has

direct influence on the financial health of the company as service excellence enhances

customers’ inclination to buy again, to buy more, to become less price sensitive and to

tell others about their positive experiences. The model (figure 2.6) proposed by Zeithaml

et al., (1996) suggests that when service quality is superior, behavioral intentions of the

customers are favorable and thus customers are retained. This customer retention results

in financial gains and the case is vice versa when service quality is inferior as behavioral

intentions are unfavorable and customers defect from the company.

WE

SE

DS

PS OSQ BI

38

FIGURE 2.6: (ZEITHAML ET AL., 1996) THE BEHAVIORAL AND FINANCIAL CONSEQUENCES OF SERVICE QUALITY

The review of models proposed by Gronroos (1984), Parasuraman et al., (1985,1988),

Boulding et al., (1993) and Zeithaml et al., (1996) in this section strengthens the

relationship of service quality to the behavioral intentions of the customers and financial

gains for the business organizations.

2.5: SUMMARY OF THE CHAPTER In this chapter the literature related to TQM, customer satisfaction and service quality is

reviewed in a systematic order. The chapter starts with brief history of the TQM. Review

of TQM literature suggests that absolute customer focus is the core component of TQM

philosophy. Available literature suggests that top management support is one of the most

critical success factors of TQM, however in developing countries mostly top management

is not committed to TQM implementation. This research will recheck this finding.

Though there is significant heterogeneity in defining customer satisfaction, it has been

concluded that affective processes are the main antecedents of satisfaction and from the

economic psychology perspective, cumulative satisfaction is more important.

Relationship between customer satisfaction and service quality is established in which

service quality is an ancestor of customer satisfaction. Various models of service quality

are presented in section 2.3. This section suggests that service quality relates to the

Favorable

BEHAVIORAL INTENTIONS

SERVICE QUALITY

Superior

Inferior

Remain

BEHAVIOR

Defect

+$ Ongoing Revenue

Increased Spending Price Premium

Referred Customers

FINANCIAL CONSEQUENCES

– $ Decreased Spending

Lost Customers Costs to Attract New

Customers

Unfavorable

39

behavioral intentions and favorable behavioral intentions are must for financial success of

the firms. This means higher the service quality; higher are the chances of financial

success because of increased customer satisfaction.

40

CHAPTER 3 - SERVICE QUALITY DIMENSIONS AND SERVICE QUALITY IN SUPPLY CHAINS

In the chapter two, it is concluded that TQM is a management philosophy based on

customer satisfaction and that an increase in service quality directly effects customer

satisfaction. This conceptual and empirical link of service quality to customer satisfaction

has turned service quality into a core-marketing instrument (Venetis and Ghauri, 2004).

Curiosity over the measurement of service quality is therefore high and researchers have

devoted a great deal of attention to service quality research (Abdullah, 2006).

Johnston (1995) categorizes service quality studies into five major debates. First there is

debate over similarities and differences between the constructs of service quality and

customer satisfaction. The second debate is about the worth of the expectation-perception

gap view of service quality. Thirdly there is concern with the development of models that

help understanding of how the perception gap arises and how managers can minimize its

effects. Fourthly the definition and use of “zone of tolerance” in service quality is

debated. Finally the identification of dimensions of service quality is critical. The

research intention of this research is related to this fifth debate because according to

Chowdhary and Prakash (2007) the question “Is there a universal set of determinants that

determine the service quality across a section of services?” is still unanswered. Therefore

literature related to dimensions of service quality is reviewed in section 3.1. Section 3.2 is

about service quality in supply chains because this research is based in a supply chains

setting. The sector selected for this research is pharmaceutical sector so section 3.3 is

about Pakistani pharmaceutical market.

3.1: SERVICE QUALITY DIMENSIONS Whilst there has been considerable progress as to how service quality should be

measured, there is little advancement as to what should be measured. Researchers

generally have adopted one of two perspectives. These perspectives are the “Nordic

perspective” and the “American perspective” (Brady and Cronin, 2001). The “Nordic

perspective” was proposed by Gronroos (1984) and the “American perspective” was

proposed by Parasuraman et al. (1985, 1988).

41

In the “Nordic perspective”, Gronroos (1984) identified 2 dimensions of service quality

(technical quality and functional quality). He defined technical quality as “what the

consumer receives as a result of interactions with a service firm” and identified

employees technical ability, employees knowledge, technical solutions, computerised

systems and machine quality as its 5 attributes. Gronroos (1984) defined functional

quality as “the way in which the technical quality is transferred” and identified behaviour,

attitude, accessibility, appearance, customer contact, internal relationships, service-

mindedness as its 7 attributes. He concluded that the technical and functional quality of

service built up the corporate “image” of the company.

The “Nordic perspective” of service quality was the first to be published in scholastic

literature. However, the first seriously dedicated program of research to answer the

questions “what’s the best way to define service quality?” and “what’s the best way to

measure it?” was launched by Parasuraman et al. (1985,1988) (Schneider and White,

2004). This program developed the “American perspective” of service quality.

Parasuraman et al. (1985) built up a 34-item service quality scale comprising 10

dimensions (reliability, responsiveness, competence, access, courtesy, communication,

credibility, security, understanding/knowing the customer and tangibles). Subsequent

work by Parasuraman et al. (1988) resulted in the service quality measurement scale with

22-items on 5 dimensions. The dimensions reliability, responsiveness and tangibles were

retained as identified in 1985 whereas communication, competence, credibility, courtesy

and security merged as a new dimension “assurance”. Access and understanding /

knowing the customer merged to form the dimension “empathy”. Parasuraman et al.

(1988) codified this scale as SERVQUAL and defined its 5 dimensions as:

Tangibility: Appearance of physical facilities, equipment and communication material.

Reliability: Ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately.

Responsiveness: Willingness to help customers and provide prompt service.

Assurance: Knowledge and courtesy of the employees and their ability to convey trust

and confidence.

42

Empathy: The caring and individualized attention, organization provides to its

customers.

While there is no global consensus that either the “Nordic perspective” or the “American

perspective” is the more appropriate approach, the “American perspective” dominates the

literature (Schneider and White, 2004) because the development of the “American

perspective” generated a “cottage industry” of replicate studies in various conditions,

sectors and countries. Parasuraman et al. (1988) claimed that the 5 dimensions and 22

items proposed in their “American perspective” are generic in nature and applicable to all

service organizations.

However, the service quality measurement scale developed by Parasuraman et al. (1988)

has been the subject of criticism since its development (Johnston, 1995). Buttle (1996)

provides a detailed critique of the issues surrounding the 5 dimensions of the

Parasuraman et al. (1988) service quality scale, mainly on the basis of number of

dimensions and contextual stability.

Carman (1990) found that the 5 dimensions of service quality measurement scale

proposed by Parasuraman et al. (1988) are not so generic that users should not add new

dimensions they believe are important. He found that if a dimension is extremely

significant to customers it is possible to be decomposed into a number of sub-dimensions

and vice versa. Babakus and Boller (1992) also empirically assessed the scale proposed

by Parasuraman et al. (1988) and suggested that the number of service quality dimensions

is dependent on the service being offered. Seth et al. (2006) summarized some of the

service quality studies published from 1984 to 2000 over a variety of service industries

(Table 4).

43

TABLE 4: ATTRIBUTES OF SERVICE QUALITY RESEARCHERS ATTRIBUTES Gronroos (1984) Technical quality, functional quality, corporate image Gronroos (1988) Recovery, attitudes and behaviour, accessibility and flexibility,

reputation and credibility, professionalism and skills, reliability and trustworthiness

Parasuraman et al. (1985)

Credibility, access, reliability, communication, understanding the customer, courtesy, competence, responsiveness, tangibles, security

Parasuraman et al. (1988)

Assurance, responsiveness, tangibles, reliability, empathy

Haywood-Farmer (1988)

Behavioral aspects (Timeliness, speed, communication verbal , non-verbal), courtesy, warmth, friendliness, tact, attitude, tone of voice, dress, neatness, politeness, attentiveness, anticipation, handling complaints, solving problems), professional judgement (diagnosis, advice, skill, guidance, innovation, honesty, confidentiality, flexibility, discretion, knowledge), physical facilities and processes (location, layout, de´cor, size, facility reliability, process flow, capacity, balance, control of flow, process flexibility, timeliness, speed, ranges of services offered, communication)

Lehtinen and Lehtinen (1991)

Physical quality (physical products + physical environment), interactive quality (interaction with persons and equipment’s), corporate quality, process quality, output quality

Mersha and Adlakha (1992)

Knowledge of service, thoroughness/accuracy of the service, consistency/reliability, willingness to correct errors, reasonable cost, timely/prompt service, courtesy, enthusiasm/helpfulness, friendliness, observance of announced business hours, follow up after initial service and pleasant environment

Ennew et al. (1993) Knows business, knows industry, knows market, gives helpful advice, wide range of services, competitive interest rates, competitive charges, speed of decisions, customized finance, deals with one person, easy access to sanctioning officer

Ghobadian (1994) Competence, access, reliability, responsiveness, credibility, understanding the customer, courtesy, communication, tangibles, security, customization

Rosen and Karwan (1994)

Reliability, responsiveness, tangibles, access, knowing the customer, assurance,

Johnston (1995) Responsiveness, care, availability, reliability, integrity, friendliness, courtesy, communication, competence, functionality, commitment, access, flexibility, aesthetics, cleanliness/ tidiness, comfort, security

Philip and Hazlett (1997)

Pivotal attributes (acquired information) Core attributes (reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy) Peripheral attributes (access, tangibles)

Dabholkar et al. (2000) Reliability, comfort, features, personal attention Source: Seth et al. (2006)

44

On the basis of overview of Table 4, it can be concluded that there seems to be no

agreement on the dimensions of service quality. Different authors have identified

different service quality dimensions in different studies. Chowdhary and Prakash (2007)

also report variations from unidimensionality to two, three, four, six and even eight factor

structures in the previous service quality studies.

Contextual stability is another issue. Cronin and Taylor (1992) suggest flexibility in the

Parasuraman et al. (1988) service quality measurement scale items and argue that high

involvement services such as healthcare or financial services have different service

quality items than low involvement services such as fast food or dry cleaning.

Researchers must also therefore consider the individual items of service quality for each

service industry. Brady and Cronin (2001) also suggest that from a theoretical

perspective, even if the 5 service quality dimensions proposed by Parasuraman et al.

(1988) are generic, something specific must be reliable, responsive, empathetic, assured

and tangible. To identify this “something” for each context is critical. Moreover, this

scale was developed in Western culture so its contextual stability across diverse cultures

is also an issue (Parikh, 2006). Based on Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, Donthu and

Yoo (1998) studied the effect of culture on consumer service quality expectations and

concluded that as a consequence of cultural orientation, consumers differ in their overall

expectations with regard to service quality dimensions.

On the basis of this literature review, it may be concluded that despite the fact that the

“American perspective” dominates the service quality literature and many service quality

studies are based on the service quality measurement scale proposed by Parasuraman et

al. (1988), there is actually no generic scale for measurement of service quality. There is

no universal set of dimensions and items that determine the service quality across a

section of service industries in different cultures, so service quality measurement must be

adapted to fit the context. Therefore there is a need for the development of context

specific service quality measurement scales. Such context specific service quality

measurement scales may help managers to gauge, manage and improve service quality in

particular sectors with more simplicity and effectiveness.

45

3.2: SERVICE QUALITY IN SUPPLY CHAINS In today’s global marketplace, individual firms no longer compete as independent entities

but compete as an integral part of supply chains links (Seth et al. 2006). Christopher

(1992) also argued that a key aspect of business is that supply chains compete, not

companies. According to Waters (2003), organizations do not work in isolation; they act

as a customer when they buy materials from their own suppliers and act as a supplier

when they deliver materials to their own customers. A wholesaler for example acts as a

customer when buying goods from manufacturers, and then acts as a supplier when

selling goods to retailers. It is therefore important to satisfy each member of the supply

chain. Beamon and Ware (1998) extended the concept of TQM into supply chains. Beamon and

Ware (1998) proposed a generic model (figure 3.1) to provide procedural approach to

assess, improve and control the quality of various supply chains processes.

FIGURE 3.1: SUPPLY CHAINS PROCESS QUALITY MODEL

Source: Beamon and Ware (1998) This model represents a shift from static models to customer satisfaction based model of

supply chains. This model consists of seven modules.

Module 4: Identify current quality

performance measures

Module 6: Improve process

Module 3: Define quality

Module 5: Evaluate current process and set

quality standards

Module 2: Identify customers & their

requirements, expectations, and

perceptions

Module 7: Control & monitor process

Module 1: Identify the process, technology and tasks being performed

46

The purpose of module 1 is to define the process and activities being performed. Once

these activities have been identified, then the activities are assigned to process stages.

These stages may include inbound and outbound transport, warehousing, production

planning/inventory control and customer service. In this research the area of research is

customer service.

The objective of module 2 is to identify customers (both external and internal) and their

requirements, expectations and perceptions.

Module 3 refines the definition of quality in the supply chains system and suggests that

during development of system definition of quality the following questions must be

answered:

- What are the goals of the supply chains process? (objectives)

- What are the internal and external customer requirements/expectations from the

supply chains process? (customer requirements)

- What is our competitor’s definition of quality? (benchmarking)

Beamon and Ware (1998) conclude that if the current supply chains process has a