Development and Literacy: An Iranian Example - Politics... · Web viewIn contrast, the literacy...

Click here to load reader

Transcript of Development and Literacy: An Iranian Example - Politics... · Web viewIn contrast, the literacy...

Politics and Literacy Programs in Pre-Revolutionary IranWillard Uncapher

A Lecture for the International Communications AssociationTrinity College, Dublin, Ireland

[The following paper looks at literacy as a social construction, and the implementation of literacy programs as embodying implicit political agenda, taking Iran as its focus. These qualities of literacy are often unacknowledged in programs promoting literacy as a sure path the modernity and modern social and economic organization. We explore the complex meanings associated with reading, the distinctions of reading and writing, and the different kinds of literacies. An implicit application of this text would be the need to consider the social politics of any kind of directed ‘literacy’ or technological skills program, such as in ‘computer literacy.’ We also consider the role of technologies such as the telegraph in upsetting the authority associated with different readings, readers, and leaders. Please note that the original lecture was written on a different piece of software, and so the textual formatting below may have changed from original]

The historical transition from agrarian to industrial based economies, often termed "development" or "modernization," has been associated with a transformation in mental and cultural outlook as well. Whereas the agrarian view was thought to be suspicious of change, relying more on tradition than rational calculation and investigation, the new opportunities of industrial and technological advancement seemed to demand the adoption of some new sort of rational and open attitude. In so far as modernization was to be planned for a society, a much more modern work force would likewise have to be created.

The European model seemed to bear this out. The ideas of the factory system, with its division of labor and mechanization of production had been put in practice by Italian textile merchants three or four hundred years prior to English Industrial revolution (Pacey 1983:28). The German scientific expertise at the time of the Industrial Revolution exceeded that of British. It was only when, whatever the reason, these two lines of development could be brought together, a change in technology and in the habits of the work force, that the material benefits of the industrial revolution could be realized. While many additional elements obviously were needed for the British, their reserves of coal, the presence of Dutch capital, fear of Indian textile competition, the enduring lesson seemed to be that modernization needed not only technology, capital, energy, and market expansion, but also a modern work force at all levels of society.

More simply, if a society could somehow acquire the technical and capital inputs, then all that was left to be acquired was a forward looking, modern work force. And left to its own devices, this same work force could be an obstacle to change, blindly unable to recognize that change could be in its own best interest. The later development theories about the nature of a modernizing society, have their origins in 19th century social science, and ultimately in such Enlightenment writing as Comte. The presumed irrationality of religion as diagnosed by the Enlightenment had to become associated with the irrationality of its supporters. Hegel and the

1

Hegelians, in emphasizing the role of reason in the process of historical development lead the perspective of someone like Marx who in the Grundisse spoke of the necessity of the aware intellectual to speak for the voice-less proletariat. The point seems not simply that the 'masses' have need for an orator, but that, addicted to the opium of religion and other detritus of the past, they are unaware of the implications of their own situation, and thus are unmotivated to change it.

There were conflicting views of what would be necessary to create a 'modern' work force. The societies of old would be replaced, functionally in any case, by what Max Weber called the rational-legal structures and belief systems, and the attitudes of workers which may have worked in an era of more piece-meal production, and I use the term workers very broadly, would have to be replaced by more disciplined, schedule oriented outlook if they were work in industries. And people would have to become more 'open' and accustomed to evaluating change, and living in a pluralistic environment. And, according to some, people would have to be more willing to take responsibility for and to direct change within their own society.

Thus if national planners were to consider how to actively modernize their nation's economy, special consideration must be given to how to "modernize" the work force. A classic and optimistic consideration of the dynamics of this change is Daniel Lerner's Passing of Traditional Society (1958:59-62) which proposes a positive correlation between urbanization, literacy, exposure to media, and such consequences as political participation, "empathy" and "psychic mobility." The presence of literacy would help lift the inward looking peasant from a traditional orientation to a more modern, "empathetic" outlook; he or she would be able to acquire more information about what his or her choices were, and thus be able to participate more actively in society, and would be able to find out about the modern innovations in health and technology. With the channel open, the information of modernity could flow in.

Since then, if not before, literacy has assumed a prominent role in modernization programs, especially those conceived under the auspices of UNESCO. Literacy could even be taken as an index of modernity. Such faith seemed to be expressed in its intrinsic powers that whoever might acquire it could be said to be modern, to have faith in modernity, and to be ready to participate in the new industrial based economy. Conversely, those who "resisted" literacy were seen as "illiterates," which implied backward. They were unable or unmotivated enough to grasp the significance of the new. Therefore programs had to be organized to "motivate" them. What UNESCO proposed to do was be a clearing house for different organizational strategies by which to bring "literacy" to the people. Indeed to this day, most of their literacy literature has to do with organization, planning, and implementation (eg. Carron 1985)

The goal of "functional literacy" meant being able to read and write so as participate in everyday economic life. Literacy was therefore a thing, a uniform activity whose presence one could measure, and compare across societies. Implicit in this consideration of the role of literacy in modernization, but not so often explicitly stated, was an assumption that literacy by itself could produce some sort of cognitive changes in its possessors. This view has variously been called the 'autonomous' (Street 1984) and 'received' (Marvin 1984) or even Realist model of literacy. Literacy was itself catalyst and much research has gone into determining what the consequences of its acquisition might be.

2

According to Angela Hildyard and David Olson (1978:9), writing, by distancing the speaker from the hearer, and by engaging the literate in an attempt to create or interpret an "autonomous" text encourages the literate to consider the inherent logic of a statement, "to operate within the boundaries of sentence meaning." The peculiar logic which underlies this autonomous view somehow relegates the social into the 'interactive,' oral sphere, and the logical into the abstract, writerly sphere. Literacy, in its ideal form, somehow manages to dump any social associations, 'all things being equal,' while the oral, in its ideal form, is thought to operate with minimal attention to logical niceties. Even allowing for a certain rhetorical exaggeration, such a view should yield to empirical verification.

Such verification, say, in Luria (1976) describing his 1931 fieldwork in Uzbekistan on the effects of literacy and schooling presents a suspicious circularity. The increased logical functioning of the literates seems to indicate the respondents have learned how to speak in categories which connote (rather than denote) educated, proper discourse. Hildyard and Olson repeatedly cite Patricia Greenfield's (1972) examination the effects of schooling among the Wolof of Senegal. Her hypothesis "that context-dependent speech is tied up with context dependent thought, which in turn is the opposite of abstract thought" (1972:169) is backed, obviously, by inferences she must draw about the informativeness of speech and written events. Her conclusion as to the paucity of information in speech events depends a great deal on whether she was able to recognize the proper codes of the event, and was able to understand just the external restrictions incumbent on that particular expression, whether oral or literate. Such recognition would either depend on her oral/literate codes and her skill at recoding.

The point is not to puzzle the circularity of the evidence. Such a demonstration lies beyond the aim of this essay and has already been undertaken a bit discursively in Street (1984), and polemically in Fuglesang (1982). Whatever the ambiguous "evidence" finally is thought to demonstrate, the point is that literacy, like "modernity," is being conceived as a thing which, like a magic pill, is supposed to transform and liberate whoever swallows it. Literacy might not only modernize the society, by making new information available for example, it might by its very practice modernize and liberate the very thinking of the people that acquire it. It encourages a new depth in rationality, objectivity, as well as an ability to empathize with distant people and event. To bestow it on individuals seems not only an economic goal, but even a spiritual one: acquiring literacy frees one to participate in modern life; it enfranchises one; it extends the privileges of the minority to the masses; it breaks the manacles of the past, manacles one did not even know one had to endure until they were gone.

This enthusiasm for literacy programs was particularly in evidence in Iran in recent years. While there had been some foreign inspired state schools in Iran as early as 1851, reaching the number of no less than 50 by 1929 (Banini 1961:89), and a effort by Reza Shah to establish a state school system modeled on the French lycee in 1921, the efforts bore their results primarily in urban areas, and quite often the schools reached those already possessing some political or social status. One problem in expanding the school system was lack of qualified teachers. While a Teachers college was founded in Teheran in 1918, only gradually, with the appropriation of state funds for the training of some teachers abroad in 1928, and the Teacher Training Act of March 1934 did the number of qualified teachers gradually increase. The last act mandated the

3

establishment of 25 teachers colleges by 1939, a goal that was exceeded. Secondly there was a need to prepare and publish adequate textbooks, a task that was begun by the Ministry of Education in 1928, based again on French models, and making use of the Persian language. (Banini 1961:94; Furter 1973:9-10).

Some institutional conflicts and funding problems complicated the expansion of the basic state educational infrastructure. Despite all the centralization of the ministry, according to Zonis, there were still the problems of overlapping and competitive sectors. The Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Arts and Culture, gradual autonomy for the 8 Universities, and the expansion of a literacy administration expanded the bureaucracy at the expense of capital investment and the raising of low teacher's salaries. (Zonis 1971:224; Green 1982:27). Still, considering the recent beginnings of system, considerable progress was being made, even if notable criticisms about funding still could be advanced. In 1922 only 15 students were graduated from the Dar-ul-Fonun, then considered the only secular institution of higher learning (Banini 1961:108). By 1966 the number of institutions of higher education was given as 48, only to triple to 148 by 1978. University enrollments jumped from 1 percent of the population ages 20-24 in 1960 to 5 percent in 1975 (World Bank 1979:171), and numerous students were being trained abroad (Green 1982:30).

Most of this educational expansion, however, was concentrated in the urban areas. A 1956 census by the government put the illiteracy rate in rural areas at 78 percent for men and 93 percent for women (Furter 1973:10). In 1961-62, while 79 percent of urban school age children could attend primary school, the availability to their rural compatriots was set at only 24 percent. The stated purpose of the 1962 reform package, usually called the "White Revolution" was to eliminate the gap between the rural and urban populace. Whatever the pressures leading to the genesis of this movement (eg. Halliday 1979:103-137), many aspects of the plan, in particular the Land Reform program which sought to buy back land from the landlords who controlled entire villages, and "return it to the tiller." sought to bring about basic social change. The Literacy Corps (or Educational Corps) sought to provide basic instruction for all children, as well as some adult literacy programs. The goals of this literacy program included such objectives as "stimulating local political activity." (Furter 1971:11) Without literacy how could the rural people become interested in and critically knowledgeable about local politics?

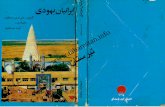

The literacy program was said to have at best mixed results. Despite an extensive organization allowing, for example, military draftees with secondary school education to do their service as primary school teachers ("sepahis"), the literacy rates did not change greatly in the rural areas. Even Furter writing for UNESCO mentions that in one program, of the 2,026 adults who attended the first half of a course, only 44 signed up to conclude it. While some effort went into better organization, there was also an effort to "motivate" people to become literate, to cast of "the burden of illiteracy” (see illustration). During the course of a special National Literacy Crusade in 1976 the Shah's wife, the Empress Ashraf visited the Crusade's activities in many provinces throughout the country, "issuing the necessary directives." (UNESCO 1978:92). The program kept in close contact with UNESCO world literacy program, and hoped for greater success by "decentralizing" the activities. The UNESCO document, listing the many conferences that were held and the many objectives that were formulated, and offering few statistics, ends with an organizational diagram. (UNESCO 1978:106)

4

Despite the stated objective of "decentralization," there is never any real indication as to how these programs were being received regionally, or even how literacy and those who possessed it were perceived. If literacy was merely a neutral technical competence to UNESCO and other modernization programs (Oxenham 1980:17), then such local differences were unimportant, being important in so far as they influenced the organization of the projects. However, evidence would suggest, as I will shortly demonstrate, that it would be naive not to consider such local perceptions and uses of literacy. If the UNESCO and other developmental literacy strategies seek to encourage "functional" literacy, so that the individual can function minimally in a "modern" society, then they must realize that, inversely, the promulgation of literacy also seeks to transform the social relations and conventions by which society "functions." Such interventions are rarely disinterested, or rarely remain disinterested.

In fact, the role and presence of literacy in Iran is particularly complex and is anything but heterogeneous throughout the society. It is well known, of course, that the area around Iran has the some of the earliest experience with writing, record keeping, and libraries in the world, as well as with the kind of bureaucracy that that sort of record keeping can produce. (Marshall 1983:47-51; Reichmann 1980:22-61) Many specifically Iranian texts have had considerable influence well beyond Iran. The book of Leviticus in the Old Testament testifies to influence of earlier Zoroastrian ritual purity writings and practices which had been codified in writing, and later selectively translated into Hebrew (during the Babylonian Exile).

Also, from very early in Iranian history, written materials were found to be in a very complex relation to spoken discourse. In the Indo-European tradition, there has long been a tension between the authority of things spoken to things written, as evidenced by the long lag in writing down such sacred writings as the Vedas in India, as well as much Avestan material in Iran until after much other more mundane writings had been committed to script. The Sandhi system of transcribing Sanskrit in accordance to how it would be spoken demonstrates that it was spoken, and not written Sanskrit that was dev nagari, the language of the gods. In Sasanian times, the Zoroastrian mobads, or high priests, were famed for the vast amount of sacred material they had memorized (cf. Boyce 1979:126-138), and to this day, Parsi priests (and not long ago all Parsi males) are expected to memorize and be able to orally recite the entirety of the Gathas, the original 'text' of Zoroaster, and the oldest portion of the Avesta.

In Islam, which displaced Zoroastrianism, authority resides with the book, the Qur'an. The Qur'an and not the Prophet is the ultimate source of revelation, the Kalam Allah, the word of God. For Christianity it does not seem particularly important that Jesus would have spoken Aramaic, nor that the New Testament was composed in demotic Greek. Such facts are blithely forgotten in common Christian parlance. The final extreme to this tendency, so the perhaps apocryphal story goes, occurs when a fundamentalist Christian mother living in the American southwest was informed that her son should learn another language in school. She replied, "If English was good enough for Jesus, it's good enough for him." The Bible, her font of truth, and to which her minister referred with his beating hand, was clearly written in English.

This could never be true in Islam. The Qur'an cannot be translated; it simply is. The Picktall English version is entitled, "The meaning of the Koran," while Arberry's English version

5

is entitled, "The Koran Interpreted" and not simply, the Koran. This is proper Islamic usage. Further, the Qur'an, more than being a collection of moral and religious exhortations, also outlines the construction of a social fabric. These two facts together have considerable implications for literacy study in Iran. First, it means that elementary religious instruction, conducted in the "maktabs" or primary schools, and for many centuries generally the only formal schooling available to the common people, consisted in verbatim memorization and interpretation of an Arabic text. Since the script in Persian is adapted from Arabic, adding only a few extra letters, mastery of Arabic script initiated the student into written Persian as well. The rural areas of Iran were not always as unexposed to literacy as the UNESCO change agents thought. At this point, the question becomes who learned this literacy, and how did its use, its function, influence its form and praxis. I will return to this point in a moment. The second consequence of having a priscus text in Arabic raises such issues as to how literacy in itself might be viewed in Iran.

The priority of the book is captured in the Qur'anic expression the Ahl al-Kitab, the 'people of the book' which designates those people possessing a Sacred Book, one revealed by a prophet of God, and who thereby have legal protection in Islamic law. This includes not only Qur'an, but also revelations given to Jews, Christians, the Zoroastrians (thanks to the Avesta) and "Sabeans." (Corbin 1958:57; also Qur'an 2.59; 5.73; 22.17) The importance of having a "book" is perhaps captured in the famous story concerning the preservation of the Corpus Hermeticum in the city of Harran in Northern Mesopotamia. Even in 830 CE, a good portion of that city still were practicing "pagans." When the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun, on passing through the city in that year discovered their ancient practice, he inquired as to what Scripture or prophet they adhered to. They could not name one at that point, and the Caliph promised to return and convert them. The pagan religion for the great mass of people was far more a matter of cult than doctrine. So it fell to the intellectuals, the book readers, to name a book. Even as these learned individuals might have named, say Plato's Dialogues, they had to name an 'ancient' and 'religious' text, one with prophets and doctrines. And so a diverse group of practices and outlooks came to be protected and represented by a single text, and one which might only tangentially concern any of them, the Greek Hermetica. (Scott 1982:97-103)

Since the actual font of authority, both secular and spiritual, lay with the Qur'an, any subsequent written codification of law or tradition would have at best secondary, and hence tentative status. Even civil government in Shi' Iran has been commonly been regarded for many centuries as 'illegitimate' or temporary, awaiting the Mahdi, or Savior who will re-establish the law of the Qur'an. And since the Qur'an only dealt with a limited number of legal questions, ways would have to found to supplement it. Various legal systems were developed in the middle ages, the most prominent organization making use of the Qur'an, then the Sunna or Traditions of the Prophet, then Ijma (or consensus), and Quiyas (or analogical reasoning). As Fazlar Rahman states, echoing many other writers, the mutual relation-ship between these four principles is highly confusing. (Rahman 1966:68)

However the lines of accommodation were to be drawn, the final act of material, legal deference had to be subsumed under the icon of the book, and importantly a book that could not change. The book could only be interpreted. And this duty would fall to the Ulama (pl. of mullah). Central to understanding the role and status of literacy in Iran is the fact that there was

6

no central 'ecclesia' which organized the opinions of the Ulama, and hence there was no single body of organized opinion which would update the Scripture. The Ulama are not a priesthood. "The Ulama are essentially those who have acquired prominence in religious learning transmitted by former generations, and who can lay no claim to ultimate authority." (Algar 1969:vi) No one figure, and hence no one opinion dominates. Hence the prestige of any one figure or view can vary considerable from place to place, time to time, jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Hence despite the apparent inflexibility of having a fundamental text, in fact this text serves as the foundation of a system of great flexibility. What was important as a mullah, then, was the opinion one proffered and the lines of authority one used to 'authenticate' that opinion. As Mottahedeh points out, "A tradition that was transmitted through several alternate chains of authorities as judged to be more likely authentic than one transmitted through a single chain." (Mottahedeh 1983:201) The Jewish Yeshiva, the medieval Catholic studium, the Buddhist sangha colleges, the Chinese mandarin system all provide parallel instances of how the complex practice of authentication characteristic of classical scriptural schools, as well as in modern legal scholarship, can create a system of much variability connected to an ideology of 'the authentic.' What was important then was not so much the ever present texts, so much as the opinions they generate.

These opinions, while they are often written down to provide grist and direction to later thought, are most often worked out in spoken parley, leading to "pedagogical styles of disputation; scholarly apparatus of logic, hermeneutical rules, and appeal to authority." (Fischer 1980:33). There is in fact, a strong oral nature to scriptural schools, leading both to the common acceptance of certain rhetorical protocols in speech, and characteristic written forms. While writers like Goody (1977) have speculated at length on the intrinsic nature of "written" and "oral" discourse, in fact these two 'discourses' are found in complex interdependence. Certainly the written is never found without the oral, a crucial point by itself, and the 'oral' at this point in history manifests quite often the knowledge and organization generated by written materials.

Goody (1977) has maintained, for example, that 'oral' discourse is volatile and malleable, while literate knowledge is fixed, restricting spontaneity. The written text provides a consistent reference by which laws and critical knowledge can be advanced. When Parry (1982) examined scriptural schools in India, he pointed out the conservatism of the oral traditions, with their emphasis on "an elaborate system of mnemonic checks and phonetic rules (vyasa siksa)... designed to ensure the exact replication of the proper sound." (1982:12) Explicitly disputing Goody, he argues that the written text introduces a new interpretational volatility, if only because the innovations in opinion can be disguised by the ideology of 'authoritativeness.' "It is the fact that the guru can appeal to a text as though it were immutable which allows him to dress up his own interpretation as the authoritative one." (Street 1984:99)

Further, this interrelation of the 'oral' and the 'written' becomes more complicated when one considers that the written is being composed to reflect oral practices, and quite often on oral models of organization, such as in the common scholastic literary form of the "debate," the clash then resolution of two points of view. (cf. Curtius 1953:62-79 on Europe; Perdue 1976 on Tibet). In particular, in the scriptural schools books are very often written to encourage spoken

7

exposition. The books are not meant to be read alone. What is important in many school books is not to put in all the logical transitions, but to provide the outline of the formal argument. The 'real' exposition is meant to take place in person, in the interaction with the needs and questions of the students. When the oral traditions and input are not considered or are lost over time the meaning and role of the scholastic texts becomes difficult to fathom. Sometimes the books consist of collected selections of materials which can be useful to illustrate or augment an oral exposition. Taken together, this interaction of 'authoritative' texts and spoken opinion produce a system of a fair amount of flexibility by which to balance tradition and innovation.

The direction of these opinions are by no means confined to theological debates. These opinions about what the right way of doing things were meant to have consequences in the Islamic world not only in sacred but also secular issues. As Mottahedeh further points out, "Learning existed in the first instance to discover the law, and in the first instance the learned justified their profession to the masses by offering authoritative opinions on the law." (Mottahedeh 1983:200) Since it is the nature of Islamic "law" to include advice on ordinary problems of living, it is the role of the learned portion of the Ulama to have a broad background of precedent, adage, and advice, all of which "presumes" and ultimately justifies itself as relating to a fundamental, and commonly accepted text and way of doing things. In contrasting the madrasa, or Islamic 'college' to priestly mnemonics and hereditary recruitment, Fischer writes, "by contrast, in the madrasa type of education, though ritual accuracy and rote learning may be important, understanding and scholarship are never incidental; they are the most valued goals to be attained... The madrasa or yeshiva is not merely a place of preparation for the ritual leader, it is also a kind of legislature and judiciary." (Fischer 1980:33)

Yet if it is a judiciary, it certainly is a patchwork kind. Among the Ulama, there has been no clear hierarchy by which to establish lines of appeal, to render definite opinions. Further, in the Madrasa system, there are no degrees. The object is to acquire as much knowledge as one can, and this is associated with whom one has studied rather than how high one rose in a system of abstract equivalences. Matters of individual precedence are agreed upon informally. "Mullahs properly trained by their teachers to use reason to give an authoritative opinion of the law were called mujtahids, jurisconsults. And only man with reason had the intellectual instruments needed to determine if another man had reason in the same degree; only a jurisconsult could appoint another jurisconsult- still another quasi-genealogical tie." (Mottahedeh 212-203). Only rarely, in Najaf and later Qum did a something like a formal system of prestige ever arise, and even then, the collegial attitude generally prevailed.

Nor was the operation and jurisdiction of the legal operations particularly well defined. In theory one did not appeal, a problem in itself, yet because of the overlapping and ill defined jurisdictions, there were no clear rules about this. Since Mohammed was himself a trader, not only have merchants been held in high respect, but the Ulama, with their often close matrimonial ties were quite often wealthy themselves. In the Isfahan are in 1946, 47 per cent of the landowners in the area were Ulama, hence there was considerable room for a 'conflict-of-interest.' (Asfar 1985:221)

The system was clearly open for renovation or organization. Certainly many of the more prominent mujtahids would have seen this expansion of their own particular influence in their

8

own interest. Changes in communication technology itself would be one fuel. For example, in the 1860's telegraph lines were strung throughout Iran. During the Tobacco Concession crisis in the 1890's, Iranian mullahs sent protests to Mirza Shirazi in Samarra, Syria, then one of the most prominent and influential Shi' mujtahids. From afar, Shirazi was able to make considerable impact on Iranian politics, to the point of having the law revoked. "Whatever their motives, by this period the telegraph helped create a national market in mullah opinions as well as in commodity prices." (Mottahedeh 217; Teheranian ).

Further, tensions between the Ulama and the increasingly centralized state served to unify the positions of the Ulama and to encourage them to set in motion forces which ultimately limited their own powers rather than expanding them. The excesses of the later Qajar regime in the late 19th century, particularly irritating in the case of wholesale economic concessions to foreign interests, as well as immunity concessions the foreigners living in Iran ("Capitulations"), as well as suspicions by the Ulama in general of the intentions of the central government, the autocracy of the Qajars, led many of the mullahs to support to national legal changes. During the 1906 Constitutional Revolution, the Ulama played a prominent, even crucial role in agitating for a national constitution. Yet as members of the Ulama soon realized, a constitution would provide the means by which laws could be created and enforced outside of their own jurisdiction. (Keddie 1981:63-78; Upton 1960:20-35; Banani 1961:14-27) The tension between the workings of these two legal systems provides a number of important insights into the role and meaning of literacy in Iran.

The movement of judicial thinking, after all, would be towards a single code of conduct. The reason that the Europeans had insisted on legal "capitulations" for their nationals residing in Iran, was "because no one knew what laws foreigners would be judged by. After all, there might be many Shi'ah law books, but where were the actual laws?" (Mottahedeh 1985:225). In 1914, Dr. Mossadegh, one of the most important figures in modern Iranian history, and a Swiss lawyer by training, wrote a book in Persian, entitled, Capitulations and Iran, where he urged that Iran adopt a written code "and thereby deprive the Europeans of their excuse, even if the adoption of a single code went against the grain of Shi'ah tradition." (Ibid.:226) When Reza Shah became prime minister, he likewise cited the capitulations as he began reforming the judiciary system (Banini 1961:70-71).

In principle the new codes were to be merely codification of pre-existing Shari'ah or religious learning. In a concession to the Ulama, the constitutionalist had guaranteed in the second article of the Supplement to the Constitution, that no law would be enacted by the Majlis or Assembly which were contradictory to the shari'ah. The new Judicial Code of 1928 on general topics was a verbatim translation of the civil code of France, while in matters of "personal status" it was to be a "codification" and simplification of the Shari'ah. (Ibid.:71) The idea, then, was to eliminate the arbitrary nature of the old system while adhering to its ideals, and at the same time to put in place a system of checks and balances over civil authority.

However this reformation proceeded, it would clearly progressively disenfranchise the mujatahids as the central, secular government gained in institutional cohesion. In 1932, the registration of legal documents such as property transactions, one of the most important functions of the shari'ah courts, and one their most important sources of income was transferred

9

to the secular courts. In 1936, the Shari'ah courts were for the most part done away with all together as the state now insisted that all judges should hold a law degree. (Ibid.:73)

With the 'arbitrariness' of the old system eliminated, the new judicial system should have brought a new coherence to local law courts. Yet more is involved in instituting such a system than having civil officials oversee an amalgam of new and traditional law. All of a sudden officials with the backing of central State are put in a position to arbitrate in local disputes, something which occurs quite often on the basis of such documentation. And the meaning of whatever is documented, in a legal sense, can be redefined by that central authority, albeit within the bounds of political reality of that central authority. And the key to documentation, to enciphering, storing, and deciphering, is literacy. While many of the laws might be similar to the old on the face of it, their application now assumed a new dimension. When the practices involved in using the old legal system shifted from an oral to a literate dominance, they likewise shifted control of the system from the locality to the State, that amorphous other referred to in Persian as the Dulat. Paradoxically, rather than eliminating arbitrariness, the new legal system emphasized it on a local level, and one of the crucial elements in effecting this was the dissemination of literacy.

That a patchwork of learned opinion should be less arbitrary than uniform law might seem paradoxical, and yet it makes considerable sense. The traditional Ulama had been closely tied to the ethos of the people of the people that they might judge if only by the fact that their livelihood depended on them, and that an unpopular mujtahid or mullah had no ultimate claim on the people he served. Without a central ecclesia, the mullah had to be particularly sensitive to community standards. To begin with, without a clear hierarchy, with no clear degree system, and because of tradition, most anyone who put on a robe and grew a beard (if he could), might appeal to the people as being a mullah. While the local populace might be strongly religious, and have great respect for learned mullahs, still they would not be above laughing even scorning some mullahs as being too "hypocritical," too "serious," or simply "lazy." (Street 1984:132). There was no automatic respect due to their office.

And likewise, the mullah would generally be engaged in some local trade. As was pointed out, Muhammad had also been a trader. The mullah had to make for their own living and usually meant combining some teaching for payment and fees for the performance of some religious service, such as presiding over wedding, funerals, or leading in certain festivals, with participation in some local forms of labor. (Ibid.:132) The local mullah had to be accepted by and integrated into the local community.

The more learned, urban mullahs, arranged more hierarchically by prestige, and some with regular legal courts, were dependent on tithes and other taxes paid voluntarily. The two major religious taxes were the zakat and the khoms. The zakat was a kind of property tax, while the khoms was a 20 percent tax on one's "surplus," however defined, which one paid to the mullah of one's choice, but then often used as part of a general fund. (Pessaran 1985:42). These taxes were institutionalized during the Safavid dynasty (1500-1722) as part of that dynasty's espousal of Shi'ism as the state religion. The funds generated in this manner help consolidate the political and economic independence of the Ulama from the state, yet it likewise made these Ulama particularly dependent on the bazaar and public opinion. (Pessaran 1985:17) The

10

flexibility in offering learned opinion based on texts would have to be sensitive to public sensibility of right and wrong.

This was not particularly true of the new State system. Grace Goodell (1986) has offered a very suggestive account of how Development plans by the State were perceived locally at two sites in south western Iran. She describes the village of Rahmat Abad as at once near to the origins of urban civilization (in lower Mesopotamia) and yet relatively untouched by it. Succeeding governments had come and gone, leaving the village relatively alone. There had been a central landlord, as in other such Iranian villages, but the people themselves had been allowed to provide for themselves. The village operated with "extraordinary predictability and economic rationality, which derived from its free, public intercourse, individual and group initiatives, individual and corporate responsibility, unrestricted flow of information, and the intelligibility and reliability of past as well as future events." (Ibid.:4)

As Clanchy (1979) suggest with regards to medieval England, the development of writing takes place within an (relatively) oral framework of thought and custom which has proved adequate to provide for orderly transfer of land titles, inheritance claims, and so on. Any new system can only be accepted tentatively, and Clanchy suggests that the oral framework of though would continue to dominate the uses of literacy. While disputes could be negotiated by a mullah or the town elder, Goodell states that, "the village's primary rule that everyone should at least speak to one another." (Goodell 1986:218). Such a village now had to face "sustained development" which defied predictability. During the land reform, land might be given out then taken back again. The intrusion of the State and its literacy could only but be viewed with suspicion. Literacy meant initiation into systems controlled by the State, the Dulat.

This is not to say that the villagers were somehow unexposed to literacy or completely uninterested in acquiring what UNESCO might call functional literacy. Written materials had a marked presence in village society, but the role conceived for these materials was often quite different. Written words might be seen as possessing intrinsic power: "Tragically, the boy Ahmad's suicide in Rahmat Abad was caused by some Dezfullis insisting that, by writing scandal about a kinsman on a piece of paper, he had turned it into truth (although his uncle in the village pooh-poohed writing on paper as constituting nothing by 'mere scribble.')" (Ibid.:260) Obviously the social and personal contexts of such an event are very complex and involve a great deal more than literacy, but this traditional attitude towards what literate documents might mean and how they might be used demonstrates the something of literacy's complex presence and power. The Qur'an, likewise, is still that actual, given word of God, the ultimate reference. "To my friends in the shahrak the fact that the Christian gospels had not been written down as God dictated them on the spot (which the Qur'an was, like a State proclamation) disproved Christianity." (Ibid.:220)

But the real problems of disseminating 'functional literacy' does not stem from tradition, but rather from a mismatch between literacy and its presumed uses. Literacy doesn't exist as a thing itself, but as something to be used. When the opportunities to learn 'functional' literacy first appeared in the village, there was much interest. Similarly, when the land reform bill buying the land from the large landowners and giving it to the villagers was passed in the early 1960's the villagers of Rahmat Abad collectively began to make a considerable investment in new farm tools and to construct new buildings. However, a few years later, in part in response to US

11

agronomists warnings about the inefficiencies of small plot size, much of this land was turned over to large, foreign investment concerns (all of which soon began to lose money. cf. Afshar 1985b:58-71; Lambton 1969:347-366). Likewise, while UNESCO and others presumed that the "literate" villagers would now be able to read the instruction manuals about how to drive tractors, and become more interested in "participating in local politics" the uses of literacy were fairly well controlled by the State. In fact, the State would seem to be interested in literacy precisely because they could control it. Informal, customary relationships, in part perpetuated and exemplified by the Ulama and their relationship to texts was to be replaced by formal relationships and Dulat.

The State controlled what would be printed as well. Since the Shah's censors could demand that any printed book be "withdrawn," few legitimate publishers could afford to invest very much money in books that might prove controversial, so there came to exist a system of 'prior restraint.' (Halliday 1979:49). What was published then would have to be acceptably benign. This is not to say that no books would be published that might be of interest locally. However, such interest takes time to develop.

Take the introduction of some form of fiction, for example. The idea that someone should learn to read so that they can enjoy the intrinsic pleasures of reading written texts, novels for example, is by no means obvious. One would have to understand first whether this sort of reading was to be a solitary activity, and if so, what value a local culture might ascribe to such a-social or even anti-social behavior. And if reading was to be followed up as a public form, such as by reading out loud, or re-telling out loud stories one has read, one would have to investigate what social conventions would pertain here as well. Perhaps the idea of telling the story of someone you don't know, about someone who is neither 'real' nor recognizable within traditional story telling oeuvres would contradict the sense of what is expected of story telling. As Kenneth Burke, C. Smith-Rosenberg and others have repeatedly pointed out, the contents and form of the book are produced in accordance with shared conventions about what a book is to look like. Such conventions would govern how one describes one's characters, does the 'action' begin. Elizabeth Eisenstein (1979) has reminded us that it took over a century for the impact of printing to be widely felt in Europe. And it did so in the context of social relation-ships which used printing, and not because of something immediately obvious within printing itself. Given the difficulty in acquiring different literate skills, the so-called resistance to literacy noted by UNESCO might originate not only in that the new texts address no practical need, except those of the State; it could be that they address no obvious pleasurable need either.

Where literacy, however defined, has made headway, there has been no need for native puppet theatres and other 'native media' extolling literacy, no need for posters illustrating the 'burden of illiteracy,' no theatrics of the Empress of Iran showing up to encourage and enthuse people, but rather there has been a perception of needs, generally defined by local society, which makes the gains in acquiring literate skills worth the effort spent in acquiring them.

Even then the "literacy" might not resemble what UNESCO and other planning officials expect literacy to look like. That is because literacy is not one "thing" but a complex of skills, whose "proper" usage, in terms of writing, reading, and talking about written materials is socially defined. And this can vary, as Bourdieu and others have emphasized, according to one's

12

education and social position. The "maktab literacy" which Brian Street (1984:129-180) investigated in North-Western Iran near Mashed is a good illustration of this.

The maktabs, as was pointed out earlier, are the traditional Qur'anic primary schools run by local mullahs on a commission basis. They are meant to provide basic instruction in the elements of faith and often in how to 'read' the Qur'an. The quality of instruction can vary considerably, and the schools are present only if there is someone at hand willing to teach. As with the Qur'anic schools among the Vai people in Liberia examined by Scribner and Cole (1981), and in Morocco as examined by Spratt and Wagner (1986) the emphasis at the maktab is on rote memorization, recitation, and knowledge of basic story lines. In so far as we define literacy as a practice involving texts, then the knowledge which these students have acquired, that is, the conventions of writing right to left and textual layout (Street 1984:153), then this is some sort of literacy. Much more impressive is, firstly, the notion that some students "may" go on to read Arabic script (Ibid.:134) since, as was pointed out earlier, this provides an access to both Arabic and written Farsi (modern Persian)- Street gives no figures- and, secondly, the notion that this literacy in turn facilitated what Street goes on to call "Commercial Literacy." (Ibid.:158)

In this commercial literacy, both dealers and producers in the fruit markets, fruit being the major local produce, recorded their transactions in special notebooks according to agreed upon conventions which allowed for various promissory agreements. The meaning of the page was to a great extent encoded, apparently, by the location of marks on the page layout. This use of layout resembles, according to Street, the layout that many of these merchants and fruit growers had first acquired at the maktab. And importantly, this writing, while a product of local merchants and growers, was conventionalized enough to have quasi-legal status in the region. (Ibid.:174) These documents could be 'signed' by one's thumb-print by those who could not otherwise print their name, which seems quite often the case. When the individuals involved needed a system of documentation, they were able to develop it out of the literacy they knew. As there was no great perceived need to extend literacy further, this system was able to operate in apparent homeostasis. This still leaves open the question, however, as to when more broadly defined literacy skills, such as might allow an individual to read the newspaper, might become imperative or strongly desired.

This can begin to be answered with the experience of the Qashqa'i, a Turkic speaking nomadic pastoral tribe located not too far distant from the region which G. Goodell had examined above in South-Western Iran, discussed above. The Qashqa'i have seen one of the most significant increases in 'functional' literacy in Iran. Two major reasons stand out. First, these people are undergoing an obvious and dramatic change in their political, economic, and cultural existence, increasingly shifting from nomadism to agro-pastoralism and regional wage-labor. (Beck 1981:99) While Reza Shah subjected all the nomadic tribes in Iran to various settlement schemes from the 1920's onward, the Qashqa'i quickly returned to their nomadic ways following Reza Shah's abdication in 1941. Even still, given many of the unintended effects of the Land Reform Bill, the Forest and Range Nationalization Bill of 1963, and the previous removal of a number of top tribal leaders, it was clear that new opportunities for their young people needed to be considered. Whereas the village of Rahmat Abad, and other such traditional agricultural villages saw themselves threatened by the government, the Qashqa'i saw themselves

13

involved in larger, more identifiable, and in many ways irreversible changes. Literacy would be needed, if only as an option, for the young people to make their way in changing world.

Equally important, however, was the general consensus among many of the Qashqa'i that such literacy was needed. This fact is captured by the remarkable success of "Tent Schools" begun by Mohammed Bahmanbegi in 1953. At that time literacy was "a rare skill of limited economic importance." (Barker 1981:140). Scribes were employed by the ruling khans to carry on their correspondence, and their was some penetration by non-Qashqa'i maktab schools, but in general literacy was not needed. What Bahmanbegi established were schools which could follow the major Qashqa'i groups on their travels. Barker sees their initial support as a matter of prestige by the Khans, but the knowledge of Bahmanbegi of tribal 'psychology,' time tables, and traditions was of crucial in establishing tribal support.

The subtitle of Barker's article, "A paradox of Local Initiative and State Control," is apt. What Bahmanbegi wanted was to help maintain the status and independence of the Qashqa'i in a changing world, and to provide for a more equitable society. These are obviously similar objectives to those of UNESCO. Herein lies the paradox. The program has been successful because it has been widely supported among the Qashqa'i, and its success has contributed greatly to their cohesion and identity. According to David Marsden, "Despite the disbanding of the Qashqa'i confederacy, and the removal of the traditional political infra-structure, the Qashqa'i have managed to survive as a distinct entity, largely through the colossal efforts of one man, Mr. Mohammed Bahmanbegi." (Marsden 1976:17) While this overstates the point, as Marsden himself demonstrates, it points to the fact that the literacy and educational effort had become instrumental as facilitating intra-societal cohesion on many levels. As Marsden then goes on to state, "The Tribal Education Office... has become something more than a mere educational office: it has become a communication channel for a great many tribal affairs." (Ibid.:17)

The new communication channel which this infrastructure was creating in fact was replacing an older one which had been eliminated under the two shahs. In fact, the roles and presence of the teachers were particularly complex. Barker states that the educators and their supervisors were "called upon by tribe’s people to serve as mediators with the government when that function was largely abolished for the tribal elite." (Barker 1981:156). While most writers about the Qashqa'i "Tent Schools" have concentrated on the 'heroic' role of Bahmanbegi, in the same way in which UNESCO type development programs tend to emphasize the role of the 'change agent,' the historical and cultural moment in which Bahmanbegi had begun his schools was in fact making uses for his schools for which he probably had not planned out.

For one thing, the maktabs and Ulama associated with the lowlands would not have been of the same significance among the Qashqa'i, particularly in legal issues which would be handled by the various Khans, or tribal leaders. (Barth 1961:147-53; for a slightly dissenting view of Barth, Fazel 1985:90-92). The nomads had been for the most part self-governing along their own traditional patterns. As their position and role changed, the khans could only take up some of their old mediating functions, although the role of family status and hierarchy is still crucial in understanding nomadic society. But the very role of the hierarchy was to wield the particular nomadic society into a cohesive unit. The lowland villages had operated in more discrete units, even though they were bound by numerous ties, such as matrimonial, trade, and so forth. The

14

kind of communication pattern the literacy agents wanted to establish was with the State. In contrast, the literacy agents and teachers among the Qashqa'i were making use of otherwise weakening communication patterns. In so doing, then, they were helping to preserve the cohesiveness of the Qashqa'i.

The paradox is that these literacy agents and educators were also dismantling Qashqa'i society. The overall impact has been to encourage settlement. There were still few jobs associated with the nomadic life style which needed literacy or formal education. The successful graduates might become teachers among the Qashqa'i again, which was not a mean position since their salaried income might augment their family's wealth. Yet outside the tribe, the prospects were not often so cheery. Often prompted by unrealistic hopes about social mobility, families were willing to make great sacrifices to send their children to these schools. In fact, the educated individuals often faced unemployment or low paying wage-labor jobs which represented as best a considerable lowering of standard of living. (Fazel 1985:88; Beck 1981:111).

Further the content of the courses was by no means as congenial to the Qashqa'i cultural identity as were the forms by which this content was taught. The tribal schools taught Iranian history in Persian, and not Qashqa'i history in Turkish. Since the textbooks were the same as in all Iranian schools, with only a few exceptions, they were imbued with the ideology of Iranian nationalism, law, and outlook. There is little wonder as to why the central government had been so generous in funding these schools. Among the lowland villages like Rahmat Abad, the designs or at least the sense of the alien nature of the outside State, the Dulat, had been fairly obvious. The literacy agents were often young army conscripts, or university students awaiting better jobs from the cities who had little in common with the people they were teaching. (Street 1984:197-200). Among the Qashqa'i, the end result of what it meant to become literate was lost or overlooked in the very success of the social mechanisms which facilitated the expansion of the schools.

The resistance or acceptance of literacy, therefore, was the result not of 'backward' 'inward' psychological attitudes, or blind adherence to outmoded traditions. Rather the problem was that literacy was not a thing in itself, a neutral skill, but instead was a social practice and deeply imbedded in expectations which the people involved had of each other. Literacy is an exercise in communication, and the people acquiring it had to want to communicate with the people offering it. They weren't communicating with 'modernity.' And the choice of accepting literacy was by no means obvious since the local societies had long since evolved legal, mercantile, and entertaining arrangements which worked well and made sense. It is these very arrangements that common sense comes out of.

In his 'radical' literacy efforts in Brazil, Paolo Friere (1972, 1985) has argued that there is an 'ideological' component to literacy programs, whether recognized or not, and that in teaching literacy, we should recognize and include this idea in the teaching itself. Literacy teaching should be participatory and cooperative; its synechdotal sign should be cooperation and not warfare. I would argue that the success of many of Freire's programs derives not from changed rhetoric nor changed content, but from the extended community his program helps to establish. The possibility of communication existed between these communities and individuals, and

15

literacy becomes the means by which to realize it. The desirability of calling one's program 'warfare' or 'cooperation' depends on the values of the society itself. Bahmanbegi referred to his tent schools as ordus, which to a previous generation among the Qashqa'i would have meant the large gathering of khans and warriors to make war preparations. (Barker 1981:154).

What the area around Rahmat Abad lacked, and the Qashqa'i not too many miles distant had, was a cooperative framework into which literacy and the teaching of literacy would be a boon. What the Shah wanted in the lowlands was to stay in control of the literacy process. It was one aspect of his very means of control, and was perceived as such. (Teheranian 1984) The attempt to 'decentralize' the teaching organization in Iran (Carron 1985) did not change what the role of literacy was to be. Literacy programs cannot be divorced from the politics of those that promulgate them, and this is especially true when, as I have examined above, one considers how interconnected literacy and legal systems always are. If they are to extend the communication networks then the people involved will have to see this to their advantage.

The attempt to 'enthuse' and 'motivate' people may have some initial impact. All people want to better their lives. They want to better the lives of the people they care about, and the promise that by 'casting off the burden of illiteracy' one might do just that can be very attractive. However, a sustained effort, whether individually or in terms of a community commitment makes a testimony to the state of that society. It is a society with enough trust to communicate.

BibliographyAfshar, Haleh. 1985a. “An Assessment of Agricultural Development Policies in Iran.” in Afshar, H. ed., Iran: A Revolution in Turmoil. Albany: State University of New York.

1985b. “The Iranian Theocracy.” in Afshar, H., ed., Iran: A Revolution in Turmoil.

Algar, Hamid. 1969. Religion and State in Iran, 1785-1906: The Role of the Ulama in the Qajar Period. Berkeley: Univ. of California.

Barker, Paul. 1981. “Tent Schools of the Qashqa'i: A Paradox of Local Initiative and State Control.” In Bonine & Keddie

Banani, Amin. 1961. The Modernization of Iran: 1921-1941. Stanford: Stanford Univ.

Beck, Lois. 1981. “Economic Transformations Among Qashqa'i Nomads, 1962-1978.” In Bonine & Keddie 1981 _____, and Nikki Keddie. The Qashqa'i People of Southern Iran. Los Angeles: UCLA Museum of Cultural History Pamphlet Series, #14

Bayot, Mangol. 1982. Mysticism and Dissent: Socio-religious Thought in Qajar Iran. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse Univ. Press.

Bonine, Michael E. and Nikki Keddie, 1981. Modern Iran: The Dialectics of Continuity and Change. Albany: State Univ. of New York.

16

Boyce, Mary. 1979. Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. When Boyce's work on the Sasanians appears, it will provide the definitive text on Sasanian literacy, a major source in understanding the archeology of Iranian literacy. It will appear as, Ao History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. 3 (Handbuch der Orientalistic 1.viii.1) Leiden: Brill.

Carron, G and A. Bordia, eds. 1985. Issues in Planning and Implementing National Literacy Programs. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning.

Clammer, J.R. 1976. Literacy and Social Change: A Case Study of Fiji. Leiden: Brill.

Clanchy, M.T. 1979. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard.

Corbin, Henry. 1957. “L'Interiorisation du sens en hermeneutique soufie iranienne.” In Eranos-Jarbuch. Zurich: Rhein-Verlag. (A crucial study examining in two historical instances of how literate practice can be tied to meditative regimen. This practice of anagogy, also found in Tibetan Lam Rim, has rarely been examined in Western literature. It has natural affinity to aspects of reception theory)

Dumont, Bernard 1973. Functional Literacy in Mali: Training for Development. Paris: UNESCO.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. 1979. The Printing Press as the Agent of Change. Princeton: Princeton Univ.

Fischer, Michael M.J. 1980. Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard.

Freire, Paolo. 1972. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin

_____. 1985. The Politics of Education: Culture, Power & Liberation. South Hadley, Mass.: Bergin & Garvey.

Fuglesang, Andreas. 1982. About Understanding: Ideas and Observations on Cross-Cultural Communication. New York: Decade Media Books.

Furter, Pierre. 1972. Possibilities and limitations of functional literacy: the Iranian experiment. Paris: UNESCO

Ghassemlow, Bahman 1974. Bildungsokonomische und Sozialpolitische Implikationen der Erwachsenenbildung von Analphabeten In Iran. Hamburg: Deutsches Orient-Institut.

Goodell, Grace. 1986. The Elementary Structures of Political Life: Rural Development in Pahlavi Iran. Oxford: Oxford.

17

Green, Patricia. 1972. (Wolof)

Halliday, Fred. 1979. Iran: Dictatorship and Development. London: Penguin.

Hasan, Abul. 1978. The Book in Multi-Lingual Countries. Paris: UNESCO

Hillman, Michael C. 1981. “Language and Social Distinctions.” In Bonine & Keddie 1981

Keddie, Nikki. 1981. Roots of Revolution.: An Interpretive History of Modern Iran. New Haven: Yale.

Lambton, Ann K.S. The Persian Land Reform: 1962-1966. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lerner, Daniel. 1958. The Passing of Traditional Society: Modernizing the Middle East. Glencoe: Free Press.

Luria, A.R. 1976. Cognitive Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard.

Marsden, David J. “The Qashqa'i Nomadic Pastoralists of Fars Province.” In the Catalogue of The Qashqa'i of Iran, World of Islam Festival 1976, Whitworth Art Gallery, Univ. of Manchester.

Marshall, D.N. 1983. History of Libraries: Ancient and Mediaeval. New Delhi: Oxford and & IBH Publishing.

McCall, Daniel F. 1962. Africa in Time Perspective: A Discussion of Historical Reconstruction from Unwritten Sources. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Mottahedeh, Roy. 1985. The Mantle of the Prophet: Religion and Politics in Iran. New York: Pantheon.

Ong, Walter J. 1982. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen.

Oxenham, John. 1980. Literacy: Writing, Reading and Social Organization. London: Routlege & Kegan Paul.

Purdue, Daniel. 1976. Debate in Tibetan Buddhist Education. Dharmshala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. Distribution limited to Dharmshala.

Reichmann, Felix. 1980. The Sources of Western Literacy. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press (Contributions in Libarianship and Information Science, #29).

Scribner, Sylvia and Michael Cole. 1981. The Psychology of literacy. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard.

18

Shivastava. Om. 1981. Literacy Work Among Small Farmers and Tribals. New Delhi: Marwah Publications.

Spratt, Jennifer E. and Daniel A. Wagner. 1986. “The Making of a Fqih: the transformation of traditional Islamic teachers in modern cultural adaptation. In White, M. and S. Pollack, The Cultural Transition: Human Experience and Social Transformation in the Third World and Japan. Boston: Routedge & Kegan Paul

Sjostrom, M and R. 1983. How do you Spell Development: A Study of a Literacy Campaign in Ethiopia. Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies.

Street, Brian V. 1984. Literacy in Theory and Practice. (Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture: 9) Cambridge: Cambridge Univ.

Teheranian, Majid. 1984. “Dependency and Communication Dualism in the Third World: With Special Reference to the case of Iran.” In G. Wang and W. Dissanayake, eds., Continuity and Change in Communication Systems. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex.

UNESCO. 1978. Literacy in Asia: A continuing challenge. Bangkok: UNESCO Regional Office for Education in Asia and Oceania.

Upton, Joseph M. 1960. The History of Modern Iran: An Interpretation. Cambridge, Mass: Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard.

Williams, J.A. 1972. Islam. New York: Washington Square.

World Bank. 1979. World Bank Development Report. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Zonis, Marvin, 1971. Higher Education and Social Change: Problems and Prospects. In Yarshater, 1971.

19