DESIGN FOR EACH ONE (D4E1) AN INTRODUCTION...

Transcript of DESIGN FOR EACH ONE (D4E1) AN INTRODUCTION...

0

DESIGN FOR EACH ONE (D4E1)

AN INTRODUCTION

INDICE

DESIGN FOR EACH ONE (D4E1) .............................................................................................1

AN INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................1

INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1

DESIGN FOR (EVERY) ONE.............................................................................................1

DESIGN CONCEPTO .........................................................................................................2

METHODOLOGY CONCEPT ............................................................................................3

USER CENTERED DESIGN ..............................................................................................3

CREATIVE CONFIDENCE ................................................................................................6

Optimism ..............................................................................................................................8

Iterate ...................................................................................................................................8

THE USER-CENTERED DESIGN PROCESS ...................................................................9

DESIGN THINKING ......................................................................................................... 11

DEFINITION ..................................................................................................................... 12

IDEATION......................................................................................................................... 12

PROTOTYPING ................................................................................................................ 12

EVOLUTION ..................................................................................................................... 12

THE THREE LENS OF USER-CENTERED DESIGN ..................................................... 13

OPEN DESIGN .................................................................................................................. 15

RULES AND ETHICAL BASES IN OPEN DESIGN ....................................................... 16

DESIGN FOR EVERYONE D4E1 .................................................................................... 19

PHASES OF DESIGN FOR EVERY ONE (D4E1) ........................................................... 24

NEEDED DRIVEN PHASE .............................................................................................. 24

Contextual disability .......................................................................................................... 25

INSTRUMENTS ................................................................................................................ 25

FEASIBLE DRIVEN PHASE ............................................................................................ 26

VIABLE DRIVEN PHASE ................................................................................................ 28

COMPETENCES IN DESIGN FOR EVERYONE D4E1.................................................. 29

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRAFICAS ............................................................................... 30

1

DESIGN FOR EACH ONE (D4E1)

AN INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Design for (every) one D4E1 was founded in 2009 at the University of Howest College by the

prototyping assistant Bart Grimonprez, the occupational therapist Bart Mistiean and the design

researcher Lieven De Couvreur. The project was a reaction to the paradigm changes within

industrial design and occupational therapy. The main trigger was the EyeWriter Project (De

Couvreur, 2016) (L. De Couvreur, 1, 1, & 2 Richard Goossens, 2013a) by Mick Ebeling, Zachary

Lieberman, Evan Roth, James Powderly, Theo Watson and Chris Sugrue. This low cost tracking

system originally designed for the paralyzed graffiti artist TEMPT1. The EyeWriter system uses

low-cost cameras and open-source computer vision software to track the user's eye movements.

Through its experiential and social approach, computer developers discover new possibilities with

the available local resources and skills. Piracy activities involve some kind of excellence, for

example, exploring the limits of what is possible, therefore, doing something exciting and

meaningful.

The essence of a "hack" (Wikipedia, 2019) is done it quickly, efficiently and generally in an

inelegant way. However, the unussual result of exploration activity evokes strong feelings of

gratification. The beginning of each adaptation process is a conflict between the constraints of a

dynamic environment and significant objectives, activities and artifacts from human agents.

Within this philosophy, we want to highlight ingenuity and self-sufficiency from a human

perspective. The advent of networked computers and digital manufacturing make it possible for

"hacker" developers to produce or adapt their own unique tools. More often, these hackers can

even compete with the qualitative standards of mass production from large factories (Bakırlıoğlu

& Kohtala, 2019). This perspective opens a complementary design strategy alternative to

universal design. It is believed that open design can be a powerful engine to create a variety of

new possibilities and solve the many complex problems of the world.

Currently working between the University of Gent, Howest School, VLIR OUS and the Technical

University of Oruro (UTO) to implement this methodology of work in the UTO as a polar focus

in the region and Bolivia, allowing to disseminate this methodology and the proactive attitude of

D4E1.

DESIGN FOR (EVERY) ONE

The design for (all) one (D4E1) is a living micro-laboratory at Howest College. It originated at

the intersection of industrial product design and occupational therapy. The laboratory implements

open design principles in the context of design for well-being. The goal is to help minority groups

through open design to meet their social needs resulting from working conditions, education,

community development and health.

A new generation of manufacturers and health professionals take advantage of this opportunity

by producing adaptations of unique products in the homes of people, private workshops and

rehabilitation centers. While future health policies are encouraging for people to participate

effectively in the collaborative maintenance of their own health, little is known about the

dynamics of these processes in the community and about how professionals can participate in

them.

2

Design for each one is structured since the base of many common parts used in the enviroment of

the design and making of low scale (Charbonneau, Sellen, and Seeschaaf Veres, 2016), some

components such as the methodologies of User-Centered Design (DCU), Design Thinking, Open

Design (Open Design) and other components that make up D4E1.

DESIGN CONCEPTO

It is important to define the design concept to guide the interpretation of D4E1. Initially mention

that industrial design can be taken as a vector, composed of a magnitude, which also has direction

and meaning; creativity is the major component of design, being that design as such is an

eminently creative activity transiting from the abstract to the tangible and "applied", as

interpreting the design, in addition to this magnitude of creativity, a direction must be given and

a definite meaning. Creativity without proper direction and meaning can result in ideas and

creations that are not applicable to reality and, above all, are not very useful in time to solve a

problem.

In the text Fundamentals of Design in Engineering (García Melón & Universidad Politécnica de

Valencia., 2009), the autors do mentions some design features related to drawing, inventing,

making plans, documenting and transmitting, linking the term design very closely to maker

projects looking that the finished product characterizes in both cases. In the same work, the

definition is supported with others, as well (Reswick, 1965) defined as a creative activity that

involves the achievement of something new and useful without previous existence; (Pahl,

Wallace, & Blessing, 2007) refers to the use of the laws of science and is based on a special

experience, and is understood in terms of process to the transformation of information from the

condition of demands, needs, requirements and restrictions to the description of a structure

capable of satisfying those demands (Hubka, 1996), in addition to (Roozenburg & Eekels, 1995)

that point to how to conceive the idea of some artifact or system and express it in a way that can

be manufactured.

Because we conceive the process of designing as a creative activity that starts from the

identification of a need or requirement, aimed at generating artifacts or systems that can be

manufactured.

D4E1

Diseño

Abierto DCU

Diseño

Industrial

Pensamiento

de Diseño

PROCESO DE

DISEÑO

PROBLEMA

O CARENCIA SOLUCION

3

METHODOLOGY CONCEPT

Another component of industrial design is the methodology that is used in it, within the concepts

of it can be cited (Riba i Romeva, 2002), which defines the Methodology as a specific and orderly

form of activities to achieve a certain purpose . According to (Pahl et al., 2007) engineering design

methodologies are a concrete sequence of actions for the design of technical systems that derive

their knowledge of design science, cognitive psychology and practical experience in different

fields. Complementary (Blanco Romero, Maria Elena, 2018) says that Methodology refers to the

study of the set of methods used in a particular branch of thought or human activity, which should

also meet the following characteristics:

1. Be applicable to all types of design activities, no matter what specialty is involved;

2. Facilitate the search for optimal solutions;

3. Be compatible with the concepts, methods and results of other disciplines;

4. Do not rely on chance in the search for solutions;

5. Facilitate the application of known solutions to related tasks;

6. Be simple;

7. Reduce the workl oad, save time and avoid human error;

8. Facilitate the planning and management of team work in an integrated and

interdisciplinary product development process.

Therefore a design methodology can be defined as a set of activities and methods to achieve a

certain purpose. This definition supports it (Cross & Vázquez, 2001), arguing that it is "the study

of design principles, practices and procedures in a broad sense." Its central objective is related to

how to design, and includes the study of how designers they work and think, the establishment of

appropriate structures for the design process, the development and application of new design

methods, techniques and procedures, and reflection on the nature and extent of design knowledge

and its application to design problems."

USER CENTERED DESIGN

Although the design activity has been an activity immersed in the actions of the human being, it

has been classified and specialized as the technological and social conditions have changed;

According to (Giacomin, 2012) three well-defined design trends can be distinguished:

4

Technology-driven design, sustainable design and man-centered design, all of which pursue

different paradigms that generate different results at the same time.

The same author (ibid) makes mention of the origins of Human centered design, arguing to have

roots in fields such as ergonomics, computer science, science and artificial intelligence. The echo

of this development fits in with ISO 9241-210 "Ergonomics of the human-centered system

interaction" that describes the human-centered design as an approach to system design and

development that aims to make systems Interactive are more usable by focusing the use on human

factors / ergonomics:

The ISO 9241-210 standard specifically recommends six characteristics:

- The adoption of multidisciplinary skills and perspectives.

- Explicit understanding of users, tasks and environments.

- User-centered evaluation development / design adjustment

- Consideration of the whole user experience.

- Involvement of users throughout the design and development.

-Interactive process.

The design focused on the product, gathers the design specifications of the average of needs and

conditions of the population seeking to satisfy the needs of most of the users, despite the detail

put in the companies for covering all the requirements of the clients, the Human individuality

causes that several factors are not satisfied, resulting in two possible actions: that the user adapts

to the product or that the user rejects or does not use the product. In this framework, designing

for a "user" generally involves optimizing the characteristics of the product, system or service

based on a fixed or preconceived set of cognitive plans and lead to designs that are efficient

towards one or more predetermined patterns of use (Degani, 2004).

Thus, the human centered design of today is based on the use of techniques that communicate,

interact, empathize and stimulate the people involved (designers, builders and users), to obtain an

understanding of their needs, desires and experiences, which they often transcend beyond what

the people themselves understand in reality. Practiced in its most basic form, the human-centered

design leads to products, systems and services that are physical, perceptive, cognitive and

emotionally intuitive (Giacomin, 2012) and also that the definition of DCU proposed by (Norman,

DA and Verganti, 2011).

5

The IDEO foundation (www.ideo.org)1 makes reference to the fact that human-centered design

means believing that all the problems, like the seemingly intractable ones such as poverty, gender

equality and clean water, are solvable. On the other hand, it means believing that the people who

face these problems every day are the ones who hold the key to their response. It is believed that

there is enough social maturity to assume the innovation of solutions from the existing

environment. Being a human-centered designer means believing that as long as you stay rooted

in what you have learned from people, you and your team can reach the new solutions that the

world needs.

In the Field Guide to User-Centered Design (IDEO 2015) (Commons, 2015), it refers to designers

in the following way: "Designers focused on the user are different from other designers, we test

and test, we fail early and often, and we spend a surprising amount of time not knowing the answer

to the challenge, and yet we keep going, we are optimists, creators, experimenters and learners,

we empathize and iterate, and we look for inspiration in unexpected places. We believe there is a

solution and that by staying focused on the people for whom we are designing and asking the

right questions, we will come together, dream of a lot of ideas, some that work and others that do

not, we make our ideas tangible so we can try them, and then we refine them, and in the end, our

approach is equivalent to wild creativity, to an incessant impulse to innovate, in addition to

confidence. goes to solutions that never we had dreamed when we started. In this design

philosophy, the seven mentalities of the user-centered designer are stated:

1. Empathy,

2. Optimism,

3. The Iteration,

4. The Creative Trust,

5. Do,

6. Embracing ambiguity and

7. The learning of failure.

1 Our roots go back to 1978, when David Kelley established his design firm, David Kelley Design (DKD).

In 1991, David Kelley, Bill Moggridge and Mike Nuttall merged their companies and called it IDEO. "My

dream for the future of IDEO is the same as it was in these time: that everyone in IDEO will find their

vocation, that being here feels like working with friends, that we all enjoy our lives, that we are committed

to what feels like important work for what they put us personally on Earth to do. " David Kelley

6

Developing the bases of Human-Centered Design, we have:

CREATIVE CONFIDENCE

It is the part in which you take into account the ideas that you have and you have the ability to act

with them (design).

David Kelley, Founder, IDEO

Anyone can approach the world as a designer. Of course, everything necessary to unlock that

potential as a dynamic problem solver is confidence in creativity, this is the belief that we are all

creative, and that creativity is not the ability to draw or compose or sculpt, but it is a way to

understand the world.

Confidence in creativity is the quality with which the designers focused on the user when it comes

to making jumps, trusting their intuition and pursuing solutions they have not fully discovered. It

is the belief that you can and will come with creative solutions to big problems and the confidence

that you need to be immersed in them. Confidence in creativity can lead you to do things, to test

them, to fail, and to keep developing, sure that you will get the knowledge you need by innovating

along the way.

It can take time to build confidence in creativity, and part of getting there is trusting that the user-

centered design process will show you how, a creative approach to bring any problem is at hand,

as you start with small successes and then build the largest, you will see that confidence in

creativity grows and in a short time you can find yourself in the mentality that you are a very

creative person (Ideo, 2016).

Make It

You take the risk building the first prototype, plus you always win.

Krista Donaldson, CEO, D-Rev

As designers focused on a man, we believe in the power of tangibility. And we know that making

a real idea reveals so much more than theory can not. When the objective is to impact solutions

outside the world, you can not live in abstractions, you have to make them real. Designers focused

on the human being are doers, modifiers, craftsmen, and builders. We make use of anything at

our disposal, from cardboard and scissors to sophisticated digital tools. We build our ideas so that

we can test them, and because actually doing something reveals opportunities and complexities

that we would never have guessed were there. Doing is also a fantastic way of thinking, and helps

to focus the viability of our designs. On the other hand, to make a real idea is an incredibly

effective way to share it. And without the sincere and actionable retro feed of the people, we will

know how our ideas advance.

As you progress through the design focused on the human being process, no matter what you do,

the materials you use, or how beautiful the result is, the goal is always to convey an idea, share it

and learn to do it better. The most interesting of all is that you can create prototypes of anything

at any stage of the process from a service model to a uniform, from a storyboard to the financial

details of your solution. As designers focused on the human being, we have a bias towards action,

and that means getting ideas out of our heads and in the hands of the people (Ideo, 2016).

Learn from Failure

Do not think about what you are failing, think about what you are designing and learning from

the process.

Tim Brown, CEO, IDEO

7

Failure is an incredibly powerful tool for learning. Designing experiments, prototypes, and

interactions and testing them is on the heart of Human Centered Design. So it is an understanding

that not everything will work while we seek to solve big problems, we are forced to fail. But if

we adopt the right mindset, we will inevitably learn something of that failure. Human-centered

design starts from a place which is not known what is the solution to a given design.

The challenge can only be found by listening, thinking, building, and refining our way to an

answer, getting something that works for the people we are trying to work with. "Fail early to

succeed before" is a common refrain around IDEO, and part of his power is the permission he

gives to get something wrong. By refusing to take risks on a problem, the solvers actually close

themselves to a real opportunity to innovate.

Thomas Edison expressed it well when he said: "I know I have not failed, I just found 10,000

forms that I have not worked yet." And for designers focused on man, what does not work is part

of finding what will work. Failure is an inherent part of human-centered design because we rarely

do well on our first attempt. In fact, doing it right on the first try is not the point at all, the point

is to put something in the world and then use it to keep learning, keep asking and keep trying.

When the designers focused on the human being do it well, it is because they were wrong in the

first attempt (Ideo, 2016).

Empathy

In order to obtain information, you have to obtain information from different people,

circumstances and places.

Emi Kolawole, Editor-in-Residence, Stanford University School

Empathy is the ability to enter other people's experience, to understand their lives, and begin to

solve problems from their perspectives. The design of centered on the human being is based on

empathy, on the idea that the people for whom you are designing are your roadmap towards

innovative solutions. All you have to do is empathize, understand them and bring them along with

you in the design process.

For too long, the international development community has designed solutions to the challenges

of poverty without really empathizing with them and without really understanding the people they

seek to serve. But by putting ourselves in the shoes of the person we are designing, DCU designers

can begin to see the world, and all the opportunities to improve it, through a new powerful lens.

Submerging yourself in another environment not only opens up new creative possibilities, it also

allows you to leave behind preconceived ideas and outdated ways of thinking. Empathizing with

the people you are designing is the best route to truly grasp the context and complexities of their

lives. But most importantly, it keeps the people for whom you are designing, at the center of your

work (Ideo, 2016).

Embrace Ambiguity

You want to explore as many possibilities as possible until the solution is revealed.

Patrice Martin, Co-Lead and Creative Director

Human-centered designers always start from the place of not knowing the answer to the problem

they are trying to solve. When starting from that position, we are forced to go out into the world

and talk to people. We are looking to serve. We also have the opportunity to open ourselves

creatively, to pursue many different ideas, and to arrive at unexpected solutions. Embracing that

ambiguity, and trusting that the human-centered design process will guide us towards an

innovative response, in reality, we give ourselves permission to be fantastically creative. One of

the qualities that human-centered design establishes is the belief that there will always be more

8

ideas. We no longer cling to the ideas of what we have because we know we will have more,

because the human centered design is a generative process, and because we work like this. In

collaboration, it is easy to discard the bad ideas, keep the problems in pieces and thus, finally,

reach the good designs, although it may seem counterintuitive. In the ambiguity of not knowing

the answer in reality, you establish the possibilities so that the designers focused on the human

being can innovate.

If we knew the answer when we started, what could we learn? How could we improve? With

creative solutions could we give? Embracing ambiguity actually frees us to seek an answer that

we initially can not imagine, which puts us on the path to innovation and lasting impact (Ideo,

2016).

Optimism

Optimism is the thing that leads them to the designers.

John Bielenberg, Founder, Future Partners

We believe that design is intrinsically optimistic, to assume a great challenge, especially in those

as big and intractable as poverty; The designers have to believe that this progress is even an option,

otherwise we would not do it and we would not even try. Optimism is the embrace of possibility

to the idea that even without knowing the answer, we know that it is out there and that we can

find it.

In addition to leading us towards solutions, optimism makes us more creative, encourages us to

move forward when we reach dead ends, and helps all stakeholders in a project. When you

approach problems, from the perspective that you will arrive at a solution, optimism infuses the

whole process with the energy and unity you need to navigate through the most thorny problems.

Human-centered designers are persistently focused on what could be, not on the countless

obstacles that can stand in the way. Restrictions are inevitable, and often push designers towards

unexpected solutions. But it is our animating nucleus. The belief that every problem is solvable,

that shows how deeply optimistic the designers focused on the human can be. (Ideo, 2016).

Iterate

When iterating we validate our ideas on the way because we listen to people for what design really

is.

Gaby Brink, Founder, Tomorrow Partners

As human centered designers, we adopt an iterative approach to solve problems because we

comment and retro feed the people we are designing as a critical part of the evolution of the

solution. Continually iterating the work, refining and improving, we place ourselves in a place

where we will have more ideas to try a variety of approaches, unlock our creativity, and reach

more quickly to successful solutions. The iteration keeps us agile, receptive and trains our focus

on getting the idea and, after a few passes, all the details towards perfection. If you aimed for

perfection every time you build a prototype or an idea, you would spend years refining something

whose validity was still in doubt. But when building, testing and iterating, you can move forward.

Your idea without investing hours and resources until you are sure that it is the only one. In the

beginning we iterate because we know that we did not do it well the first time, or even in the

second time the iteration gives us the opportunity to explore; do it wrong, follow our hunches,

and ultimately arrive at a solution that will be adopted. Adopting the iteration allows us to

maintain learning. Instead of hiding in our workshops, betting that an idea, product or service will

be a success, we quickly leave the world and let the people for whom we are designing be our

guides (Ideo, 2016).

9

THE USER-CENTERED DESIGN PROCESS

In order to face a design project, two aspects are rescued, the first one that every design process

is unique due to the variety and personalization of it, which can be improved at the same time

(Ostuzzi, 2017), on the other hand, the scheme presented by the Methodology of User-Centered

Design by IDEO follows three common phases to any of the cases:

Each of these steps are (IDEO,2015):

In this phase, you identify the need and learn to understand

the people, observing the user, their life, listening to their

hopes and desires, and under taking an intelligent challenge.

During the listen stage, the Design Team will compile

stories, anecdotes and inspirational elements. You will have

to prepare for the investigation and set up the field work

guide.

In this phase, is given meaning of everything that has been

heard, generates a lot of ideas, identifies opportunities to

design, test and refine his solutions.

In the stage of Creating, the team will work on an exercise

whose purpose will be to collect what has been observed in

people to put it into theoretical frameworks, opportunities,

solutions and prototypes. During this phase they will move

from a concrete thought to a more abstract thought in the

identification of themes and opportunities, and then return to

the concrete through solutions and prototypes.

In this stage the solution is brought to life, you discover how

to market your idea and how to maximize its impact on the

world. The Implementation stage is where you will begin to

realize your solutions through a financial model of income

and costs, the evaluation of capacities and the planning of the

implementation. This will help you launch new solutions in

the world.

10

The design process within each phase moves between the tangible and the abstract. The

Inspiration or Discovery phase begins by going out into the world and learning from people. The

inspiration phase is about reducing what you have learned and translating those lessons into

themes and patterns. This is followed by the prototype phase, where your ideas quickly evolve

into tangible designs fed back into real comments (IDEO, 2011).

In the "Inspiration" phase, data is taken from the User's need as a starting point to set the challenge

and plan the design path, this is a concrete phase to receive the need for design in a real way.

Once we have a frame of reference, we move on to the next phase of "Ideation", in which research

about similar solutions is started, as well as a list of the most specific requirements based on a

deeper knowledge of the problem, the phase Research is characterized by the abstraction of not

having something specific focused and rather going towards the diverse, being therefore a

divergent stage. Once the investigation of the problem has passed, we enter the solution ideation

phase, a stage in which the information is synthesized in the generation of solution ideas, due to

the synthesis of ideas. This is a convergent and tangible phase to have results solution to the

problem; In this same phase we analyze and select one of the solution ideas to proceed to the

"Implementation" stage, knowing that we want to design a manufacturing strategy, find out

materials, tools, machinery and base products to be reused in a new modified function. This part

of the "Implementation" phase is an abstract and divergent phase, since once again we open the

possibilities of realization looking for the best manufacturing strategy. The last part of the

"Implementation" phase is a convergent and tangible stage, which deals with the physical

obtaining of the design through its manufacture.

A description of this iterative design process is given by the + ACUMEN foundation as shown

below (+ Acumen, 2019):

In the same way, IDEO describ at 3 phases of design as the follow shape (IDEO, 2011)

11

In accordance with the principles of user-centered design, the design will be developed according

to the scheme shown:

Although the user-centered design is well structured in the 3 phases, usually and due to the

interaction with the end user of the product, and in the proposed co-design with the user (Adikari,

Keighran, & Sarbazhosseini, 2013) the divergent convergent model is repeated several times

within the same phase.

DESIGN THINKING

In 2005, the Hasso Plattner Design Institute (d.school) was founded at Stanford University, after

the name of its main donor, SAP co-founder Hasso Plattner, based on the concept "Design

Thinking" developed by David Kelley , Larry Leifer. and Terry Winograd. Design thinking takes

into account the "context", that is, the requirements of people, technological possibilities and

economic viability. Design thinking provides a flexibility that contrasts with the rigidity of

analytical thinking; In addition, design thinking incorporates creativity into approaches (Boy,

2017).

The "Design Thinking" methodology structures the design process in 5 phases instead of 3 as

IDEO does, being these: Empathy, Definition, Ideation, Prototyping and Evolution (Dinngo,

12

2019), highlighting that the design process It is not a linear route and can go back and forth or

jumping stages if necessary, always pursuing the ultimate goal.

EMPATHY

The Design Thinking process begins with a deep understanding of the needs of the users involved

in the solution we are developing, and also of their environment. It must be able to put on the skin

of these people to be competent to generate solutions consistent with their realities (Dinngo,

2019).

DEFINITION

During the Definition stage, the information gathered during the Empathy phase must be sifted

and what really adds value and leads us to new interesting perspectives. We will identify problems

whose solutions will be key to obtaining an innovative result (Dinngo, 2019).

IDEATION

The stage of Ideation aims to generate endless options. You should not stay with the first idea that

comes to mind. In this phase, activities favor expansive thinking and value judgments must be

eliminated. Sometimes, the most bizarre ideas are those that generate visionary solutions (Dinngo,

2019).

PROTOTYPING

In the Prototyping stage, you return to real ideas. Building prototypes makes the ideas palpable

and helps to visualize the possible solutions, highlighting elements that we must improve or refine

before reaching the final result (Dinngo, 2019).

EVOLUTION

During the testing and evolution phase, we will test our prototypes with the users involved in the

solution. This phase is crucial, and will help identify significant improvements, failures to be

solved, possible shortcomings. During this phase, the idea evolves until it becomes the solution

that was being sought (Dinngo, 2019).

This process is summarized according to the diagram of (IDEO, 2011) as follows:

13

THE THREE LENS OF USER-CENTERED DESIGN

IDEO, makes mention that the User Centered Design (UCD) is a process and a set of techniques

used to create new solutions for the world. These solutions include products, services, spaces,

organizations and modes of interaction. The reason why this process is called "people-centered"

is due to the fact that at all times, it is focused on the people for whom the new solution is to be

created. The UCD process begins by examining the needs, dreams and behaviors of the people

who will benefit from the resulting solutions. It is intended to listen and understand what these

people want, what they need. That is called the dimension of what is DESIRABLE. Throughout

the entire design process we look at the world through this perspective. Once you have identified

what is desirable, you begin to see the solutions through what is FEASIBLE and what is VIABLE.

These perspectives are illustrated in the manner shown:

14

The solutions must end at the intersection of the three magnifying glasses, beginning with the

desirable as a gateway to the challenge.

15

The three magnifiers proposed by IDEO can be broken down in time together the assignment of

tasks for each phase and condition of the design.

OPEN DESIGN

In the attempt to universalize knowledge and technology, the concept of Open Design has been

developed and structured by different organizations and in diverse academic and work

environments as mentioned (Bakırlıoğlu & Kohtala, 2019), as : "that open design has emerged

together and as part of the phenomena that show citizens, consumers and users in post-industrial

economies, the interest in" openness ".

More participative and inclusive forms of design have been achieved, supported by more open

design processes, as well (Maldini, 2014) defines: Open design is an emerging phenomenon that

plays a crucial role in the current design landscape. It can be defined as a dynamic of democratic

participation, accessible and connected with users. So too (Micklethwaite, 2012) mentions: open

design (OD) has brought together ideas of shared creation and democratic access, leading to a

"participatory social innovation". Reference is also made to the open and shared creation of

physical objects. In the context of manufacturing, current developers with laser cutter equipment,

CNC routers and CNC milling cutters, and domestic equipment adapted for digital manufacturing,

point the way towards a more decentralized and customer-focused culture of "creators" (Igeo T.,

2011).

The researchers (Marttila & Botero, 2013) have framed these developments in the design

discourse as the "opening turn", particularly in the space of co-design. These authors consider that

the open design has two main lines of research and practice. The first chain that we can identify

is publicly available and publicly shared designs (for example, blueprints), this implies the free

exchange and adoption of designs, following the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) movement that goes back

to previous projects such as Nomadic Furniture in 1973 and Autoprogettazione? (Automatic

design) (Ostuzzi, 2017), which evolved through accessibility to data thanks to web 2.0

technologies and user generated content (for example, IkeaHackers.net, Openstructures.com).

This conception of open design is also linked to other lines of research in design, such as

Production (Marttila & Botero, 2013). Inter-part production is originally open source production

for software, but now also for tangible products.

As a research focus, the review of production between parts often puts in the foreground, how

communities create, define, relate and act to protect or exploit several shared common resources

(Redlich et al., 2016). The notion of Benkler, of production of parts based on the common good

(Boisseau, Omhover, & Bouchard, 2018) also weighs when researchers and professionals are

16

discussing and writing about open design, such as considering open source designs and

knowledge of design contribute to a common good that should be open and freely available.

The second line or chain that they identify (Marttila & Botero, 2013) is the open design activity

shared throughout the creation process. The authors connect this line of research and practice with

the type of open design promoted in the volume Open Design Now (Micklethwaite, 2012)

suggests that people who participate in the design activities to produce products (especially in fab

labs and makerspaces), also they work with co-design, as a participatory design.

In the same text (Micklethwaite, 2012), Michall Avel in the chapter of "The Generative Bedrock

of Open Design" writes about the value proposition and the push of open design, mentioning that

these are "distributed manufacturing" processes that emphasize opening capabilities related to

use. The main players in open design are consumers. While designers undoubtedly play a key role

in driving open design by producing and sharing appropriate design plans, BLUEPRINTS

ultimately, consumers involved in distributed manufacturing are the main players and the

rationale of the open design. According to traditional doctrine, design is primarily a preliminary

stage before commercial manufacturing and distribution. In contrast, the open design is aimed at

consumers engaged in manufacturing, through the channels of conventional manufacturing and

distribution. The open design implies that the design plans are available to the public, can be

shared, licensed under open access terms and are distributed digitally in general terms under a

code of ethics.

Open design means being able to freely share open-access digital plans that can be adapted at will

to comply with the established requirements, and that consumers can then use them to

manufacture products on demand commercially outside the platform, recognizing the authorship

of the base of the open source pieces that he used.

RULES AND ETHICAL BASES IN OPEN DESIGN

While the basic idea of open design is to share the designs and documentation of the developed

products, one must manage and maintain ethical rules of recognition of intellectual property,

mentioning the name of the designer of the product's origin, not entering a figure of plagiarism.

Vallace mentions in this respect that licensing agreements guarantee freedoms and are described

in the definition of open design "Protected", and the design may be modified and redistributed

(Vallance, Kiani, & Nayfeh, 2001). Anyone is free to use an open design as a functional element

or a proprietary or non-proprietary system provided that the element of the open design is clearly

identified. However, any individual or organization that uses or modifies an "Open Design" must

accept the terms specified in an Open Design license:

• Documentation or a design is available for free.

• Anyone is free to use or modify the design by changing the design documentation.

• Anyone is free to distribute the original or modified designs (paid or free of charge),

• Design modifications must be returned to the community (if redistributed).

In the Open Design environment, the precepts that are handled as design rules are those generated

by the Open Source Definition organization, which initially were oriented to share open software

design codes, but have subsequently been used as a framework of reference to share all open

design products.

Open Source Definition (open source, 2011) mentions: Open source does not only mean access

to source code. The distribution terms of the open source software must meet the following

criteria:

17

1. Free redistribution

The license shall not restrict any party from selling or giving away the software as a component

of an aggregate software distribution containing programs from several different sources. The

license shall not require a royalty or other fee for such sale..

2. Source code

The program must include source code, and must allow distribution in source code as well as

compiled form. Where some form of a product is not distributed with source code, there must be

a well-publicized means of obtaining the source code for no more than a reasonable reproduction

cost, preferably downloading via the Internet without charge. The source code must be the

preferred form in which a programmer would modify the program. Deliberately obfuscated source

code is not allowed. Intermediate forms such as the output of a preprocessor or translator are not

allowed.

Rationale: We require access to un-obfuscated source code because you can't evolve programs

without modifying them. Since our purpose is to make evolution easy, we require that

modification be made easy.

3. Derived works

The license must allow modifications and derived works, and must allow them to be distributed

under the same terms as the license of the original software.

Justification: The mere ability to read source isn't enough to support independent peer review and

rapid evolutionary selection. For rapid evolution to happen, people need to be able to experiment

with and redistribute modifications.

4. Integrity of the source code of the author

The license may restrict source-code from being distributed in modified form only if the license

allows the distribution of "patch files" with the source code for the purpose of modifying the

program at build time. The license must explicitly permit distribution of software built from

modified source code. The license may require derived works to carry a different name or version

number from the original software.

Justification: Encouraging lots of improvement is a good thing, but users have a right to know

who is responsible for the software they are using. Authors and maintainers have reciprocal right

to know what they're being asked to support and protect their reputations.

Accordingly, an open-source license must guarantee that source be readily available, but may

require that it be distributed as pristine base sources plus patches. In this way, "unofficial" changes

can be made available but readily distinguished from the base source.

5. Non-discrimination against persons or groups

The license must not discriminate against any person or group of persons.

Justification: In order to get the maximum benefit from the process, the maximum diversity of

persons and groups should be equally eligible to contribute to open sources. Therefore we forbid

any open-source license from locking anybody out of the process.

6. There is no discrimination against fields or efforts

The license must not restrict anyone from making use of the program in a specific field of

endeavor. For example, it may not restrict the program from being used in a business, or from

being used for genetic research.

18

Rationale: The major intention of this clause is to prohibit license traps that prevent open source

from being used commercially. We want commercial users to join our community, not feel

excluded from it.

7. Distribution of the license.

The rights attached to the program must apply to all to whom the program is redistributed without

the need for execution of an additional license by those parties.

Rationale: This clause is intended to forbid closing up software by indirect means such as

requiring a non-disclosure agreement.

8. The license must not be specific for a product

The rights attached to the program must not depend on the program's being part of a particular

software distribution. If the program is extracted from that distribution and used or distributed

within the terms of the program's license, all parties to whom the program is redistributed should

have the same rights as those that are granted in conjunction with the original software

distribution.

Rationale: This clause forecloses yet another class of license traps.

9. The license must not restrict other software

The license must not place restrictions on other software that is distributed along with the licensed

software. For example, the license must not insist that all other programs distributed on the same

medium must be open-source software.

Rationale: Distributors of open-source software have the right to make their own choices about

their own software.

10. The license must be technologically neutral

No provision of the license may be predicated on any individual technology or style of interface.

Justification: This provision is aimed specifically at licenses which require an explicit gesture of

assent in order to establish a contract between licensor and licensee. Provisions mandating so-

called "click-wrap" may conflict with important methods of software distribution such as FTP

download, CD-ROM anthologies, and web mirroring; such provisions may also hinder code re-

use. Conformant licenses must allow for the possibility that (a) redistribution of the software will

take place over non-Web channels that do not support click-wrapping of the download, and that

(b) the covered code (or re-used portions of covered code) may run in a non-GUI environment

that cannot support popup dialogues.

In summary, the open design suggests "design knowledge" without limitations in the exchange to

call the participation of people with different backgrounds to develop and iterate design solutions

(Bakırlıoğlu & Kohtala, 2019).

Open Design, designs a system for the co-creation of artifacts, which can be designed by a

participatory group or, equally, a unique project leader. The participation of end users is left open

to modify, personalize and innovate, and often translates into a unique and personalized product

(Richardson, 2016).

The open design can be seen as the open design platform referred to a set of predefined standards,

parts, assembly or software that allows the replication and modification of solutions in the context

of the platform or referred to design solutions that are stripped of their properties contextual to

facilitate the appropriation and iteration with different local and individual contexts (Ostuzzi, De

Couvreur, Detand, & Saldien, 2017).

19

In open design, we identify the need to differentiate not only open or non-open contributions and

open or non-open solutions, but also to clarify and distinguish processes, whether open to

participate or openly shared, and results, such as open, modular, or closed. Then mapping these

differentiations in relation to the study contexts, whether they are manufacturing by equipment,

batch manufacturing or hybrids (Bakırlıoğlu & Kohtala, 2019).

There was a document (Koren, Shpitalni, Gu and Hu, 2015) that perceived openness as end-user

processes designated as open design, which draws similarities with mass customization, such as

the user's authority to altering the design or artifacts is highly restricted.

There has been evidence of the use of open design products within the development of

copyrighted solutions for mass production, in this case the distinction of results is quite simple:

the open results are digital and physical artifacts with design, details, forms of production,

schemes, test results, others, openly available for anyone to replicate, adapt and alter. The closed

results are proprietary, a black box. Artifacts, without knowledge or right to replicate, adapt or

reveal them. In designs that contain both parts, open and closed modules, different strengths of

both are used for different purposes (Koren, Shpitalni, Gu, & Hu, 2015).

DESIGN FOR EVERYONE D4E1

Design for each one is: an open design methodology, focused on the user, which takes as a target

customers people with disabilities, so that in co creation between those involved, personalized

technical assistance teams are obtained for users seeking to increase their independence and

improve their quality of life.

"Design for every one" D4E1, proposes to create an inclusive bridge between the community of

designers and people with disabilities who are in rehabilitation. This is done by co-constructing

the solution with the participation of the team of designers, occupational therapists and users of

the team in the whole process simultaneously (L. De Couvreur, 2010).

The use of experience in the creation of prototypes and low-volume manufacturing techniques

allows products to be made that adapt to the emerging abilities and challenges of users with unique

disabilities, personalizing technical assistance products to users and preparing the user for the use

of them.

There are 7 considerations that support D4E1:

1. CONTEXT

People with disabilities, paramedics and designers who participate in the network, design and

construct innovative assistance devices for their own use and, subsequently, freely reveal their

design information to others. Then others are invited to replicate and improve the device, and

even to participate in the innovation process by revealing their improvements, or they can simply

replicate the design of the product and adopt it for their own internal use. Eric von Hippel (Von

Hippel, 2007) describes this type of open network as a place where "the development of

innovation, production, distribution and consumer networks can be built horizontally, with actors

that consist only of users of the innovation (more precisely: own users / manufacturers) ". The

user innovation network allows each individual (broken down) to develop assistance devices

according to their specific needs.

20

2. DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK

The objective is to create a general framework for co-designing assistive devices in a horizontal

network of innovation users and for disabled users. This framework tries to identify, share and

use "hidden solutions" in rehabilitation contexts and translate them into disruptive assistance

devices built with local resources. By applying this open network to the level of rehabilitation

engineering, we aim to:

• People with individual disabilities benefit directly from solutions that respond to their

specific problems.

• Manufactures can use this user-centered, open design approach to determine what should

be designed and, sometimes, what should not be designed or manufactured as universally

designed products.

3. ALL vs. ONE

Designing for one specific user is not new…in fact it is the oldest tailor-made approach we

know. The big gap that industrial progress opened up between the pro-fessional provision of

design and our common com-petence and readiness to see and solve the problems around us,

activated a new breed of active users na-mely Pro-ams; committed and networked amateurs

working to professional standards.

State of the art technology supports these professional standards and brings DIY (Do It

Yourself) back on the map as a valuable business model. Thanks to the rise of the internet

and flexible manufacturing processes, we are capable of making niche products on demand.

21

Designers will not longer only design for people, they will have to learn to design with people.

Co-creation requires a language that both designers and nonde-signers can use.

4. USER-PRODUCT ADAPTATION THROUGH CO-DESIGN

The World Health Organization recognizes disability “as a complex interaction between features

of a person’s body and the features of the environment and society in which he or she lives.”

When designing personal as-sistive devices little can be learned by objective data gathering and

analysis.

Problems involving disabled people have a certain “wicked component” which demands an

opportunity-driven approach; requiring decision making, doing ex-periments, launching pilot

programs, testing prototy-pes, and so on.

A certain amount of trial and error is necessary in un-tangling the physical, emotional and

cognitive needs of specific patients. Problem understanding can only come from creating possible

solutions, building know-ledge through validating specific solutions with indivi-dual users in

reallife contexts.

This is the point where co-design methodology comes in as a powerful engine for user-innovation.

Co-de-sign can be used as a set of iterative techniques and approaches that puts users at its heart,

working from their perspectives, engaging latent perceptions and emotional responses. The key-

roles in this co-design process are forming a trialogue around the aspects of assistive technology:

goal, technology and user.

(1) GOAL : Paramedic/occupational therapist:

The occupational therapist detects which type of as-sistive device the patient needs to achieve his

or her meaningful goals and by doing so he sets the starting point for the first iterations. In most

cases the patient and therapist have already physically hacked an uni-versal assistive device which

can be seen as a trans-lation of a latent need or a hidden solution for the pro-blem.

(2) USER: Patient/Caregiver

The patient is given the position of ‘expert of his/her experience’. In some cases when the patient

has dif-ficulty with communicating his feedback verbally, the caretaker plays an important role

as translator. De-pending on the level of creativity they join the design process by expressing

themselves in creating, using or adapting the assistive prototypes

22

(3) TECHNOLOGY: Industrial designer

The industrial designer becomes the facilitator bet-ween the occupational therapist and the patient.

He continuously translates user-values and behavior into product properties with local resources.

His main job is to ideate and create tools/prototypes, which enables the occupational therapist to

communicate on a physi-cal level with his patient.

5. ITERATIONS

The key language in this methodology is composed by physical prototyping. The user-

manufacturer has to be creative with the resources at hand, which leads in most cases up to a form

of “hacking design”. Product concepts are build and adapted out of re-used devices and basic

materials which are available in the local context.

During this process the user-manufacturer slowly shifts from experience prototyping to personal

manu-facturing. He keeps a track of existing, new and emer-ging technologies, has an overview

of available pro-duction processes within his environment.

23

6. STIGMERGY

The design of the assistive devices results in “open pro-ducts” under creative commons licenses

which other occupational therapists can build on and apply in vari-ous rehabilitation contexts. All

plans and design pro-cesses can be found on the web.

Based on the Fablab philosophy devices are produced that can be tailored to local or personal

needs in ways that are not practical or economical using with mass production. The intellectual

property of the source de-sign remains with the patient while the alteration and realization of the

final product anchor it in the resour-ces and realities of a local manufacturer.

7. VALIDATION

This initiative is organicly growing and realised without funding. Students industrial design and

occupational therapy from Howest university college work in mul-tidisciplinary teams with the

patients, caretakers and professional paramedics.Each year the eductation program closes with an

open design fair at the industrial design center, where all knowlegde is shared with companies,

NGO’s, acade-mics and famelies.

24

PHASES OF DESIGN FOR EVERY ONE (D4E1)

As user-centered design methodology proposed, D4E1 has 3 design phases are also taken: the

phase of what is NEEDED, the phase of what is FEASIBLE to do and the phase of the VIABLE

of building.

The meaning of this iteration was proposed by Conklin (Westcombe, 2007), and developed by

Lieven (L. B. J. De Couvreur, 2016), based on the graph shown below.

NEEDED DRIVEN PHASE

According to Wessels, 4 factors have to be taken to begin with the design of assistive technologies

(Wessels, 2003):

1. Personal factors.

2. Factors related to the equipment.

3. Factors related to the user's environment.

4. Factors related to the intervention.

Reviewing what is needed, we must see the human being as the social capital, and the individual

with disabilities must be supported with assistive technology so that they can rejoin society with

greater independence. The figure below is a conceptualization of assistive technology, the person

with disabilities and society (Forlizzi, 2008).

25

In the identification phase of what is needed, two unfavorable aspects look there:

a. They differ for each specific local context, as well as the dwelling of the disabled

person.

b. Many of these aspects are emerging, it is not predictable and changes continuously on

time.

In this phase of identification of the need, the person with a disability (user) must be visited to

define what they need, expressed in their own vision and requirement, as well as the vision of the

Occupational Therapist who helps define the type of device that It can be solution to your

requirement. At this point it should not be forgotten that the solution will be co-designed between

the Occupational Therapist User and Designer.

Contextual disability

Disability is a complex phenomenon, reflecting an interaction between the characteristics of a

person's body and characteristics or the society in which he or she lives (L. De Couvreur, 2015).

The design of the technical assistance tool will be the result of a solution to the 3 environments:

the person, their interaction environment and their occupation.

INSTRUMENTS

In this phase you can use a data collection instruments:

• Visit

• Poll

• List of requirements,

• others.

In more detail you can see the user-centered design guide (Commons, 2015).

26

As the design stage begins, and in accordance with its iterative and oscillating development

between the abstract and the tangible, in this same phase it is possible to investigate possible

solutions in similar cases of open design or in general.

The research is done using instruments such as technical help pages such as Instructables.com or

technical articles in coordination with the occupational therapist.

In this stage, it is also use the Proto morphism defined as prototyping focused on the user and its

ergonomics, to verify that the solution can be accommodated to the user and vice versa.

FEASIBLE DRIVEN PHASE

Once the solution ideas have been generated and the requirements of the user and occupational

therapist have been verified, we proceed to specify at least two designs from which the most

convenient one can be selected. A technique widely used for the collection of design options is

the morphological matrix, on the basis of which you can visualize and select the designs.

27

These designs must be analyzed, if they fulfill required functions and technical design conditions.

Verifying that the designs fulfill the requested functions, we proceed to make the selection of the

design to be developed. In this stage there are several techniques, the most used being the decision

matrix.

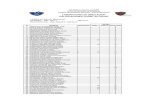

Ideas Cost

0,3

Manufacturin

0,2

Efficience

0,1

MMaintenance

0,2

Safty

0,1

Confiability

0,1

Total

1

DESIGN

1

1

0,3

3

0,6

4

0,4

4

0,8

4

0,4

3

0,3

2,8

DESIGN

2

2

0,6

3

0,6

3

0,3

3

0,6

1

0,1

2

0,2

2,4

Selected the solution, in this phase of feasibility, proceeds to select the materials, base product to

modify and manufacturing processes that will be needed.

When the modified product is mentioned, it refers to this as "physical hacking", which requires

the user-manufacturer to be creative with the available resources and skills, which leads to the

reuse of components and materials available in the local context (L. De Couvreur, 1, 1, & 2

Richard Goossens, 2013).

28

Also note that you must work with emphasis on proto morphism more than only prototyping, can

mention some differences between the two:

Prototiping / Hacking Proto morphism

The functions of the product are very

vaguely determined.

The key functions of the product are

fixed and personalized.

Different concepts (prototypes) are

shown/tested.

Multiple tests to "refine" the original

prototype.

The coordination with the user is not

very precise.

The goal is to tune the functions to the

specific user(s).

The function prevails over ergonomics. The function harmonises with the

ergonomic properties of the product.

You can describe this process in the following way:

VIABLE DRIVEN PHASE

In this third phase we proceed to manufacture the prototype with the materials and final

manufacturing processes to complete the construction of technical assistance. In this stage the

design modifications are also finished, ending the open design project and generating the technical

documentation for its dissemination.

29

By completing these stages, a public exposure is generated as the beginning of communication of

the result and its respective documentation. In this part the delivery of the product to the user is

also done fulfilling the requirement of Implementation of the solution.

COMPETENCES IN DESIGN FOR EVERYONE D4E1

Each step of the design process must meet four competencies necessary for its correct execution,

as follows:

1. EVALUATE = define / empathy

2. DESIGN = creativity / variation

3. IMPLEMENT = prototype / modification

4. CONTEXT = reaction / reflection

EVALUATE: Both the user's need and the proposed solution must be evaluated in a co-design

framework, which serves as a common language among all interested parts, which identifies

significant goals and shows personal limits to achieve. It is important to act with empathy to the

user to design elements that are adapted to their needs and are usable.

DESIGN: In the creative stages of the process, there must be a commitment to generate as many

alternatives as possible and contrast them with the list of user requirements; in this role, the

variation of approaches and solutions should be used.

IMPLEMENT: This competence indicates that the necessary amount of tests, modifications and

prototypes must be carried out to ensure the implementation of that step, both in the expectation

of solution and in the solution itself.

CONTEXT: In the analysis of the requirements as well as in the solution proposals, the context

of the user, staff and environment must be taken into account, the reaction of the same to the

proposed solution and its applicability of the solution in real conditions.

30

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRAFICAS

+Acumen. (2019). Introduction to Human Centred Design. Retrieved from

https://www.plusacumen.org/

Adikari, S., Keighran, H., & Sarbazhosseini, H. (2013). Embed Design Thinking in Co-Design

for Rapid Innovation of Design Solutions. (A. Marcus, Ed.) (1st ed., Vol. 8015). Toronto,

Canada: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39253-5

Bakırlıoğlu, Y., & Kohtala, C. (2019). Framing Open Design through Theoretical Concepts and

Practical Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. Human–Computer Interaction,

0024, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2019.1574225

Blanco Romero, María Elena, autor. (2018). Metodología de diseño de máquinas apropiadas

para contextos de comunidades en desarrollo. [Barcelona] : Universitat Politècnica de

Catalunya,. Retrieved from

https://discovery.upc.edu/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1510559__SMetodolog%EDa de

dise%F1o de m%E1quinas apropiadas para contextos de comunidades en

desarrollo__Orightresult__U__X7?lang=cat

Boisseau, É., Omhover, J.-F., & Bouchard, C. (2018). Open-design: A state of the art review.

Design Science, 4, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2017.25

Boy, G. A. (2017). Human-centered design of complex systems: An experience-based approach.

Design Science, 3, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2017.8

Charbonneau, R., Sellen, K., & Seeschaaf Veres, A. (2016). Exploring Downloadable Assistive

Technologies Through the Co-fabrication of a 3D Printed Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Dog

Wheelchair. In M. Antona & C. Stephanidis (Eds.), Universal Access in Human-Computer

Interaction. Methods, Techniques, and Best Practices (pp. 242–250). Cham: Springer

International Publishing.

Commons, C. (2015). Diseño centrado en las personas. (C. Commons, Ed.) (2nd ed.). New York.

Couvreur, L. De, 1, W. D., 1, J. D., & 2 Richard Goossens, 3. (2013). The Role of Subjective

Well-Being in Co-Designing Open-Design Assistive Devices. International Journal of

Design, 7(3). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy-

ub.researchport.umd.edu/docview/1468157559?accountid=28969%5Cnhttp://sfx.umd.edu/

ub?url_ver=Z39.88-

2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&genre=article&sid=ProQ:ProQ%3Aabigl

obal&atitle=The+Role+of+Subjective+Well-Be

Cross, N., & Vázquez, F. R. P. (2001). Métodos de diseño: estrategias para el diseño de

productos. Limusa. Retrieved from https://books.google.be/books?id=J8etAAAACAAJ

De Couvreur, L. (2010). D4E1. Retrieved March 31, 2019, from

http://designforeveryone.howest.be/

De Couvreur, L. (2015). Adaptation by product hacking. A cybernetic design perspective on the

co-construction of Do-It-Yourself assistive technology. https://doi.org/10.4233/uuid

De Couvreur, L. B. J. (2016). Adaptation by product hacking: A cybernetic design perspective on

the co-construction of Do-It-Yourself assistive technology. Gentt University.

Degani, A. (2004). Taming HAL: Designing Interfaces Beyond 2001. Palgrave Macmillan.

Retrieved from https://books.google.be/books?id=SG07muS_S2EC

Dinngo. (2019). Design Thinking. Retrieved March 29, 2019, from

http://www.designthinking.es/inicio/

Forlizzi, J. (2008). The Product Ecology: Understanding Social Product Use and Supporting

Design Culture. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DESIGN, 2(1), 11. Retrieved from

http://mendeley.csuc.cat/fitxers/9075f52c8d4ec8bb79e62677559fe221

31

Garcia Melon, M., & Universidad Politecnica de Valencia. (2009). Fundamentos del diseno en la

ingenieria. Valencia : Universidad Politecnica de Valencia. Retrieved from

https://discovery.upc.edu/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1393709__Sfundamentos del dise%F1o

en la ingenieria__Orightresult__U__X7?lang=cat

Giacomin, J. (2012). What is Human Centred Design. In 10o P&D Design 2012, Congresso

Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design, São Luís (MA) (p. 14).

https://doi.org/10.2752/175630614X14056185480186

Hubka, V. (1996). Design science : introduction to the needs, scope and organization of

engineering design knowledge / Vladimir Hubka and W. Ernst Eder. London : Springer,.

Retrieved from https://discovery.upc.edu/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1109884__SDesign

Science __Orightresult__U__X7?lang=cat

Ideo. (2016). HCD Toolkit, 2nd Editio, 188. Retrieved from http://books.ideo.com

IDEO. (2011). Educadores. Educarchile (1st ed., Vol. 1). Chile: Creative Commons.

IDEO. (2015). Field Guide to Human-Centered Design Design Kit. (IDEO.org, Ed.) (1st ed.).

Canada.

Igeo T., M. C. (2011). A Strategist ’s Guide to Digital Fabrication. Retrieved from

https://www.strategy-business.com/article/11307?gko=63624

Koren, Y., Shpitalni, M., Gu, P., & Hu, S. J. (2015). Product design for mass-individualization.

Procedia CIRP, 36(December), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2015.03.050

Marttila, S., & Botero, A. (2013). The ‘Openness Turn’ in Co-design. From Usability, Sociability

and Designability Towards Openness. Co-Create 2013: The Boundary-Crossing

Conference on Co-Design in Innovation, 99–110.

Micklethwaite, P. (2012). Open Design Now: Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive by Bas van

Abel, Lucas Evers, Roel Klaassen and Peter Troxler. Design Journal, 15(4), 493. Retrieved

from http://mendeley.csuc.cat/fitxers/ec980b35dc73b2bbcf668c690b282308

Norman, D. A. and Verganti, R. (2011). INCREMENTAL AND RADICAL INNOVATION:

DESIGN RESEARCH VERSUS TECHNOLOGY AND MEANING CHANGE. In 5th

Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces (pp. 22–25). Politecnico di

Milano, Milano, Italy.

open source. (2011). The Open Source Definition (Annotated). Retrieved March 26, 2019, from

https://opensource.org/osd.html

Ostuzzi, F. (2017). Open-ended design : explorative studies on how to intentionally support

change by designing with imperfection. Ghent University. https://doi.org/8539015

Ostuzzi, F., De Couvreur, L., Detand, J., & Saldien, J. (2017). From Design for One to Open-

ended Design. Experiments on understanding how to open-up contextual design solutions.

The Design Journal, 20(sup1), S3873–S3883.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352890

Pahl, G. (Gerhard), Wallace, K., & Blessing, L. (2007). Engineering design : a systematic

approach. London : Springer. Retrieved from

https://discovery.upc.edu/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1368828__SEngineering design a

systematic approach __Orightresult__U__X4?lang=cat

Redlich, T., Buxbaum-Conradi, S., Basmer-Birkenfeld, S. V., Moritz, M., Krenz, P., Osunyomi,

B. D., … Heubischl, S. (2016). Openlabs - open source microfactories enhancing the fablab

idea. Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

2016–March, 707–715. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2016.93

Reswick, J. B. (1965). Prospectus for the engineering design center. (& M. Graham, C.R., Ed.).

Cleveland, Ohio.

32

Riba i Romeva, C. (2002). Diseño concurrente [Recurs electrònic] / Carles Riba Romeva.

Barcelona : Edicions UPC,. Retrieved from

https://discovery.upc.edu/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1227498__SRiba, Dise%F1o

concurrente__Orightresult__U__X2?lang=cat

Richardson, M. (2016). Pre-hacked: Open Design and the democratisation of product

development. NEW MEDIA , 18(4), 653. Retrieved from

http://mendeley.csuc.cat/fitxers/bf2d9f6dcd0fe48fa183fd1e2db45a31

Roozenburg, N. F. M., & Eekels, J. (1995). Product design : fundamentals and methods.

Chichester [etc.] : Wiley. Retrieved from

https://discovery.upc.edu/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1120065__SProduct design:

fundamentals and methods__Orightresult__U__X4?lang=cat

Vallance, R., Kiani, S., & Nayfeh, S. (2001). Open design of manufacturing equipment. … on

Agile, Reconfigurable Manufacturing, …, 1–12. Retrieved from

http://diyhpl.us/~bryan/papers2/open-source/Open design of manufacturing equipment.pdf

Von Hippel, E. (2007). Horizontal innovation networks by and for users. In Industrial and

Corporate Change (pp. 293–315). Oxford University.

Wessels, R. (2003). Non-use of provided assistive technology devices, a literature overview.

Technology and Disability, 15(4), 231. Retrieved from

http://mendeley.csuc.cat/fitxers/96c67ca555bc98978b466558a64a551c

Westcombe, M. (2007). Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems

J. Conklin. The Journal of the Operational Research Society, 58(5), 696. Retrieved from

http://mendeley.csuc.cat/fitxers/ea553fb0a480149d2dbe19e66c5da830

Wikipedia. (2019). Hacker. Retrieved March 27, 2019, from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hacker