DE 3429 - Amazon Web Services · DE 3429. 1. Fantasy for flute and piano on the opera Il Trovatore...

Transcript of DE 3429 - Amazon Web Services · DE 3429. 1. Fantasy for flute and piano on the opera Il Trovatore...

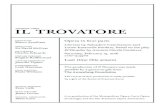

1. Fantasy for flute and piano on the opera Il Trovatore by Verdi (10:19)(Fantasia per flauto e pianoforte sull’opera Il Trovatore di G. Verdi)

2. Free transcription of Verdi’s Traviata for flute and piano (11:00)(Libera trascrizione sulla Traviata di Verdi per flauto e pianoforte)

3. Dramatic Fantasy for flute and piano on the opera Aida by G. Verdi (7:25)(Fantasia Drammatica per flauto e pianoforte sull’opera Aida di G. Verdi)

4. Fantastic piece on Verdi’s Ernani for flute and piano (7:59)(Ernani di Verdi pezzo fantastico per flauto e pianoforte)

5. Fantasy for flute and piano on the G. Verdi opera Don Carlo (7:40)(Fantasia per flauto e pianoforte sull’opera di G. Verdi Don Carlo)

6. Fantasy on Verdi’s Macbeth for flute and piano (10:03)(Macbeth di Verdi Fantasia per flauto e pianoforte)

7. Fantasy on themes from Verdi’s opera Rigoletto for flute and piano (10:59)Fantasia su dei motivi dell’opera Rigoletto di Verdi per flauto e pianoforte

Total Playing Time: 65:58

Verdi-Briccialdi Operatic Fantasies

Delos Executive Producer: Carol RosenbergerRecording and editing: Marco Taio

Recorded 0ctober 25th and 26th, 2012San Martino Church, Palazzo Pignano, Cremona, Italy

Cover photo: Pietro CarrieriBriccialdi photo courtesy of Gian-Luca Petrucci

7 & W 2013 Delos Productions, Inc., P.O. Box 343, Sonoma, California 95476-9998(707) 996-3844 • (800) 364-0645 • [email protected]

Made in USA • www.delosmusic.com

While transcriptions for certain solo instruments of pop-ular operatic arias and instrumental sections had beenaround since the late seventeenth century (i.e., earlyFrench opera transcriptions for organ), the widespreadpractice of operatic transcriptions (often called “fan-tasies,” as they are here) intensified considerably acrossEurope as the Romantic era took shape in the early1800s. As with so many of his other pioneering contribu-tions to music history, Franz Liszt – the supreme pianistof his day – probably did more to promote the popular-ity of virtuoso transcriptions than any other musician.Beginning in the early 1830s, he practically invented thesolo instrumental recital, bringing music that had hith-erto been restricted to more intimate salons and soiréesto public concert stages for the first time. This opened afloodgate of transcribed music from accomplished play-ers of other instruments well suited to solo performance:violin, flute, clarinet, oboe, etc. And by far the most pop-ular basic musical materials for such transcriptions werethe famous arias or other appealing primary themesfrom the most popular operas of the day. After all, operawas then the predominant musical craze; their mostmemorable melodies being something like today’ssmash-hit pop tunes among the general public.

It should be noted that transcriptions of these “hit tunes”were adapted either as theme-and-variations pieces, or assingle or multiple melodies arranged within a singlepiece; as such, they served a variety of purposes and func-

tions. Perhaps their most immediate purpose was to serveas the basis for flashy and technically spectacular vehiclesdesigned to show off the composer-performer’s own vir-tuosity and musicianship, thus generating further publicdemand for their concerts (as well as the bigger fees thatcame with growing public adulation). At the same time,many composers produced such transcriptions to paypersonal homage to the great opera composers of the day,and – by presenting concerts in smaller towns and citiesthat lacked opera houses – to further spread public popu-larity of their best melodies. Finally, in most culturedhouseholds of the aristocracy and the rapidly emergingmiddle class, amateur musical accomplishment was con-sidered a “social virtue” – and performing music en familleremained a popular domestic pastime. Accordingly, ac-complished amateurs comprised a steady market for as-sorted chamber works and arrangements of many otherkinds of music (like Liszt’s Beethoven symphony tran-scriptions): a market that music publishers of the day tookfull advantage of. Thus many such virtuosos (and theirpublishers) achieved not only more widespread fame, butconsiderable fortune as well from their transcriptions.

As will be seen in flutist/musicologist Gian-LucaPetrucci’s thorough and informative biographic sketch,few – if any – of Europe’s notable nineteenth-centuryflute virtuosos achieved the kind of fame and fortunethat Italian master Giulio Briccialdi (1818-1881) enjoyed.As you listen to this CD’s survey of his brilliant fantasies

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM

on themes from the great operas of his countrymanGiuseppe Verdi, you will marvel at his care, creativityand craftsmanship – as well as the staggering virtuosity– that made him a legend in his time. Indeed, the intimi-dating technical difficulty of these pieces may possiblybe the reason why all but the Aida Fantasy have neverbeen recorded before.

— Lindsay Koob

Giulio Briccialdi is known to have produced 184 compo-sitions, including didactic, chamber, vocal, symphonic andoperatic works; however, tracking his output as a com-poser is complicated by the problem of not being able tomake specific references to the dates of composition, opusnumbers and manuscripts. Moreover, this problem is ag-gravated by the fact that he often published the samework with different publishers, under different titles andopus numbers. His primary priority was to distribute thematerial that either the composer or the publisher consid-ered important on account of its immediacy and topicalityin the wake of a soloist’s success, making it “à la mode”.This explains the immediate rush to print – and therefore,the almost complete absence of any manuscripts kept byBriccialdi himself; he must certainly have delivered theoriginal drafts of his works directly to the editors for print-ing without bothering to keep copies of his own. In orderto make all the information in our possession regardingthe works presented in this CD available and clear, wehave drawn up the following outline, which will providethe reader with some essential points of reference.

— Gian-Luca Petrucci

(Editor’s Note: Mr. Petrucci’s original outline below hasbeen expanded upon by adding at least partial referencesto the primary orchestral passages and/or arias treated ineach fantasy, as provided by the album’s artist, Mr. Tre-visani. However, seasoned opera fans are likely to noticeadditional themes as well as they listen. – LK)

1. Original title: Fantasia per flauto e pianofortesull’opera Il Trovatore di G. Verdi (Fantasy for flute andpiano on the opera Il Trovatore by Verdi)Autograph: unknown • Date of composition: unknown• Opus number: none • Dedication: To the distin-guished amateur musician and honorable advocateFrancesco Antonio D’Araujo, resident of Bahia • Origi-nal period edition: Milan, Tito Ricordi 1858

Il Trovatore – Verdi’s bizarre tale of a cross-generationalcurse and vengeful justice in fifteenth-century Spain –was first heard in 1853. The transcription treats aria andduet themes including hero Manrico’s “Mal reggendo al-l’aspro assalto” (At my mercy lay my enemy) from ActII, in which he explains to Azucena, his alleged mother,why he spared his enemy’s life in a duel. From Act IV,listen for heroine Leonora’s “D’amor sull’ ali rosee” (Onrosy wings of love), voicing her tender thoughts of lovefor Manrico after she has resolved to remain true to himby taking poison. You’ll further hear “Sì, la stanchezzam’opprime” (Home to our mountains), Manrico’s finalduet with Azucena; also “Che! ... non m’inganna quelfioco lume” (What? Does that dim light deceiveme?), where the doomed Manrico spends his own final

moments with the dying Leonora.

2. Original title: Libera trascrizione sulla Traviata diVerdi per flauto e pianoforte (Free transcription of Verdi’sTraviata for flute and piano)Autograph: unknown • Date of composition: unknown• Opus number: none • Dedication: none • Original pe-riod edition: Milan, Edizioni Lucca 1856

La Traviata – Verdi’s ever-popular opera on the subjectsof high-society frivolity and star-crossed romance – wasfirst performed in 1853. Among others, you’ll heararrangements of instrumental and aria themes like“Croce e delizia” (Torment and delight), Alfredo’s ar-dent declaration of love from his Act I duet with Vio-letta. There’s also Violetta’s deathbed lament, “Addiodel passato” (Farewell to the past) – and “Parigi, o cara”(Soon shall we leave Paris), her final duet with Alfredoas they give heartbroken voice to their hopeless dreamof happiness together (both from Act III).

3. Original title: Fantasia Drammatica per flauto e pi-anoforte sull’opera Aida di G. Verdi (Dramatic Fantasy forflute and piano on the opera Aida by G. Verdi)Autograph: unknown • Date of composition: unknown• Opus number: op. 134 Dedication: To the distinguished flautists, the Hughesbrothers • Original period edition: Milan, Edizioni Ri-cordi 1875

The first performance of the opera Aida, Verdi’s tale oflove, war and tragedy in ancient Egypt, took place in 1871.Among the themes treated in this transcription are “Glo-ria all’Egitto” (Glory to Egypt), the grand triumphant pro-cession from Act II; the exotic orchestral prelude to Act III;and heroine Aida’s Act IV aria, “O terra, addio” (Farewell,O earth) – her poignant leave-taking from the world andits sorrows.

4. Original title: Ernani di Verdi pezzo fantastico perflauto e pianoforte (Fantastic piece on Verdi’s Ernani forflute and piano)Autograph: unknown • Date of composition: unknown• Opus number: none • Dedication: To the distin-guished Emanuele Giuseppe D’Araujo • Original periodedition: Turin, Edizioni Giudici e Strada 1858

Verdi’s early opera Ernani (first performed in 1844) re-volves around the intrigues and power struggles of thesame Spanish royal family depicted in his better-knownlater opera Don Carlo, only a generation earlier. The pri-mary music transcribed here is the first-act cavatina “Er-nani, Ernani involami,” (Ernani, save me) followed by“Tutto sprezzo che d’Ernani” (I scorn all that does notspeak to my heart of Ernani) – both sung by heroineElvira as she awaits (in vain) her impending rescue andelopement with the title hero: a banished prince turned“Robin Hood”-style outlaw.

5. Original title: Fantasia per flauto e pianofortesull’opera di G. Verdi Don Carlo (Fantasy for flute andpiano on the G. Verdi opera Don Carlo)Autograph: unknown • Date of composition: unknown• Opus number: op. 121 • Dedication: To his friend Luigi Lori • Original periodedition: Milan, Tito Ricordi 1868

Premiered in 1867, Don Carlo (set in 16th-century Spain)is one of Verdi’s many operas written on themes of revo-lution and liberation; here amid a welter of love-trian-gles, jealousy and horrors of the Spanish Inquisition.This transcription centers around “Carlo ch’è sol il nos-tro amore” (Carlo, who is our only love), the second-actromance and trio, in which Rodrigo begs Elisabetta tosee Carlo again – while Princess D’Eboli suggests that itis she whom Carlos loves instead.

6. Original title: Macbeth di Verdi Fantasia per flauto epianoforte (Fantasy on Verdi’s Macbeth for flute and piano)Autograph: unknown • Date of composition: unknown• Opus number: op. 47 • Dedication: To his friendTheobald Boehm, first flute in the Royal Orchestra ofMunich • Original period edition: Milan, Edizioni Gio-vanni Ricordi 1847

First staged in 1847, Verdi’s Macbeth – based on theShakespeare play – is one of his earlier operas. Bric-cialdi’s fantasy is based primarily on “Vieni! t’affretta!”

(Come! Hurry!) – Lady Macbeth’s first-act response to aletter from her husband recounting his fateful encounterwith the opening scene’s gathering of witches.

7. Original title: Fantasia su dei motivi dell’opera Rigo-letto di Verdi per flauto e pianoforte (Fantasy on themesfrom Verdi’s opera Rigoletto for flute and piano)Autograph: unknown • Date of composition: unknown• Opus number: op. 106 • Dedication: To the flute students of Instituto Musicale ofFlorence • Original period edition: Milan, Gio. Canti1862

Rigoletto, initially staged in 1851, is Verdi’s classictragedy of aristocratic arrogance, evil and violation of in-nocence. Among the arias transformed here are the duet,“Figlia! - Mio padre!” (Daughter! – My father!) – as Rigo-letto (the womanizing Duke’s court jester) greets hisyoung daughter Gilda, whom he is hiding from the des-picable Duke. Also listen for “E’ il sol dell’anima” (Loveis the sunshine of the soul), sung by the disguised Duketo Gilda as he plans to seduce her … then, “Ah, veglia odonna, questo fiore” (O woman, watch over this flower),a duet between Rigoletto and Gilda after he asks thegirl’s nurse to guard his precious daughter’s purity.

GIULIO BRICCIALDI, born in Terni in Umbria onMarch 2, 1818, displayed a great talent for music fromchildhood and began to study the flute under his fa-ther’s guidance. After losing his father at the age of 12,he continued his studies withlocal teachers before moving toRome to perfect his techniqueas a pupil of GiuseppeManeschi, who taught at theSanta Cecilia Institute. Afterthat, Briccialdi began his pro-fessional career with the aim ofobtaining contracts with the or-chestras that were being as-sembled at that time to put onopera seasons of variouslengths in the numerous the-atres in every major city inItaly and Europe.

To become well known andsought after depended on thequality of an artist’s perform-ances, and in that respect Bric-cialdi must have been an absolutely extraordinaryphenomenon. Such must have been his personality andthe prestige he enjoyed that he was permitted (in keepingwith the performing practice of the time), to transcribe forflute the famous harp solo that precedes the soprano ca-

vatina “Regnava nel silenzio” in the first act of Donizetti’sLucia di Lammermoor, modifying to his own advantage andabilities an orchestral part that was otherwise hardly wor-thy of his talent as a performer. He went on to be in great

demand as a “first flute” who,moreover, could be dependedupon to elaborate on the inter-mezzi passages between acts insuch a way as to inspire ap-plause from the audience. Thisis probably the reason why Bric-cialdi never gained a permanentrole in any of the orchestras inthe prestigious theatres withwhich he collaborated in manycities, among them Naples(Teatro San Carlo), Milan(Teatro alla Scala), Bologna(Teatro Comunale), Venice(Teatro La Fenice) and Rome(Teatro Argentina).

Thanks to these wanderingsfrom one city to another – as

well as his noble and elegant figure and his ability to de-velop a good rapport with others – he soon became widelyknown. At the same time, the lessons he gave to amateurmusicians among the nobility – often capable and sophis-ticated instrumentalists who could fully appreciate the

value of an artist such as Briccialdi – enabled him to attainthe highly prestigious position of teacher to the Count ofSyracuse: the brother of Ferdinand of Bourbon, the King ofNaples. After resigning his post at the Neapolitan court in1839, Briccialdi came to Milan where he carried on hismany activities in an advantageous environment of greatartistic ferment and in closer proximity to those CentralEuropean countries where, no doubt, he sought to gain in-ternational recognition of his talent. This talent was soprodigious that in 1840, at just 22 years of age, he was in-vited to play at the same concert in the foyer of the Teatroalla Scala in Milan with Antonio Bazzini, a virtuoso vio-linist of the same age. His concertizing increased, and –despite his marriage in 1841 – Briccialdi became increas-ingly busy and ever more determined to make his markinternationally as a soloist.

For the next ten years, Briccialdi worked with great suc-cess in the capitals and musical centers of Europe, formingties with such important figures in his era’s world ofmusic as Gaetano Donizetti, Alfredo Piatti, Adrien Servais,Giovanni Bottesini and Sigismund Thalberg. At the sametime, he worked to promote new ideas regarding flute de-sign and construction in order to make the instrumentmore suitable to growing expressive needs. Briccialdi’sfame was such that the most active of the flautists inter-ested in organological research, the German TheobaldBoehm, thought it only natural to entrust him alone withthe task of making the prototype of his new flute known

throughout Europe. Briccialdi, who played an 1832 modelof the Boehm flute manufactured by Godfroy in Paris, ac-cepted readily and later described in his autobiographyhis genuine interest in the new instrument. However, de-spite months of practice, he encountered considerable dif-ficulty in playing the new Boehm flute during a solorecital given in Coburg under conductor Louis Drouet,one of the greatest flautists of the century. Although theflute-makers Rudall & Rose offered Briccialdi a contractto present in London the new instrument (to which theyhad the exclusive manufacturing rights in Britain), Bric-cialdi harbored ever-increasing doubts as to the instru-ment’s fingering problems.

Two years passed without the planned official presenta-tion taking place, and Rudall & Rose – noticing his loss ofinterest in the new flute designed by Boehm – asked Bric-cialdi and other flautists to develop a system that had thesound and intonation of the Boehm flute, but kept the fin-ger positions of the old flute. In 1849, during his Londonperiod as an adviser to Rudall & Rose, Briccialdi inventedthe B-flat thumb key for the Boehm flute, which greatlysimplified the fingering and was adopted so universallythat it is still known today as the “Briccialdi B”. Still inLondon and barely recovered from a devastating boutwith cholera, Briccialdi suffered a nagging infection of thelips, which prevented him from playing for some time.Nevertheless, his fame was such that this enforced periodof recovery served only to increase his public’s desire to

hear his concerts again. He generated such enthusiastic re-sponse that the sophisticated (and severe) critic RichardShepherd Rockstro (1826-1906) – himself a flautist, teacherand inventor of another model of the flute – wrote in hiswork, A Treatise on the Flute: “I have no hesitation in say-ing that Briccialdi was one of the finest performers that Iever heard on any instrument. His perfect intonation, var-ied style, and consummate mastery over his instrumentare to be remembered but not described, and his tonemade such an impression upon me that I immediately setit up as a model to be imitated if possible.”

Briccialdi remained in England until 1851, the year inwhich the improvements he had made to the Boehm flutewere officially presented at the Great Exhibition in Lon-don. At the age of thirty-three, after years of success andwidespread recognition, he returned to Italy – where healternated between performing as a soloist in the role offirst flute in various orchestras and principal of ensembleand orchestra, while composing music for the theatre. In1854, in fact, he accepted a commission to compose theopera Leonora de’ Medici (libretto by Francesco Guidi); Heconducted its first performance the following year atTeatro Carcano in Milan. At that time Briccialdi was one ofthe first conductors to use a baton and to come from theranks of wind players, rather than from the strings, as wasthe tradition.

Like Verdi and other leading Italian artists of his day, Bric-cialdi shared the ideals of his era’s political intelligentsia,

who strongly advocated the unification of Italy – and hepersonally took part in various fundraising concerts insupport of General Giuseppe Garibaldi’s proposed un-dertakings. Meanwhile, in flute-playing circles, the con-troversy continued on the use of the Boehm flute asopposed to the old design with his numerous improve-ments. Disputes arose among the most highly ratedflautists in Italy, and Briccialdi – while participating ac-tively in the discussion – continued to consider improve-ments on the flute of his invention. In 1871, he was giventhe post of flute teacher at the Florence Institute of Music,where his design was adopted as the official instrument –re-igniting old disputes that became increasingly harsh,causing him great disappointment. Nevertheless, in orderto demonstrate the validity of his system, he intensifiedhis presence in Italy as a concert flautist, performing withsingers and other famous instrumentalists. Finally, in 1879,he was appointed flute professor at the Florence Insti-tute, where he gained further recognition for his model offlute. But his already-precarious health deteriorated – andhe passed away on December 17, 1881, at the age of sixty-three. Briccialdi was one of the greatest flautists of thenineteenth century; his legend was destined to carry onthrough the deepest essence of his example: art combinedwith craftsmanship, bel canto combined with virtuosity.

© GIAN-LUCA PETRUCCI

Raffaele Trevisani, recognized as one of the outstandingflutists of his generation, has been praised consistently bypublic and critics for his style, musicality and beautiful tonequality. “Trevisani is one of the very few pupils of Sir JamesGalway,” wrote Pan of his London debut in 1998. “Mr. Tre-visani has inherited many of Galway’s qualities and addedsome of his own.....thrilling sound and splendid technique....electrifying clarity... sculpted with great artistic precision.The applause and cheers which followed were more appro-priate to La Scala than Wigmore.” He has also received unan-imous praise from Jean Pierre Rampal, Maxence Larrieu andJulius Baker.

Mr. Trevisani, a native of Milan, began his solo career with ISolisti Veneti, performing in numerous prestigious concert se-ries in Italy and around the world. He has also performed assoloist with the Orchestra da Camera di Padova e del Veneto,I Pomeriggi Musicali di Milano, I Cameristi della Scala, ISolisti della Scala, the Orchestra of Teatro Lirico of Cagliari,the Kammerorchester “Arcata” Stuttgart, the Bielefelder Phi-larmoniker, the Orquestra Sinfonica do Estado de Sao Paulo,the Orquestra Sinfonica de Santo Andrè, the Orchestra “Can-telli,” the Istanbul State Symphony Orchestra, the MoscowChamber Orchestra, the Silesian Philarmonic Orchestra of Ka-towice, Israel Strings Ensemble, the Chamber Orchestra ofSouth Africa, The Orquestra Sinfonica do Paranà, the SukChamber Orchestra, and many others.

Raffaele Trevisani has played in some of the major halls ofJapan (Bunkakaikan, Suntory Hall, Nikkei Hall), USA,Canada, South America, Russia as well as in Italy (Teatro allaScala, Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, Settimane Musicali inStresa, Amici della Musica in Florence, Società dei Concertiin Milan, Accademia Filarmonica “Bellini” in Catania,…), Eu-rope, (Wigmore Hall in London, Musikhalle in Hamburg,Rudolf-Oekter-Halle in Bielefeld, Philarmonie Gustav-Siegler-Haus in Stuttgart), Switzerland, Turkey, Slovenia andIsrael. He has participated in well-known music festivalssuch as Settimane Musicali in Stresa, Settembre Musica inTurin, Palaces of St. Petersburg International Music Festival,Rheingau Music Festival, International music festival of Ma-puto, Mozambique and the Campos de Jordao Music Festi-val. He played for the celebrations of “Ten years of freedom”in Pretoria (South Africa).

He performed three flute concertos written for him by Italiancomposers Carlo Galante and Alberto Colla and by South-African Hendrik Hofmayr. In 2009 he performed another newconcerto for piccolo and strings written for him by Braziliancomposer Ernani Aguiar. He has been invited to play andgive masterclasses in the most prestigious flute festivalsaround the world (Boston, Frankfurt, Detroit, Chicago, Rome,Las Vegas, Milano) and to perform as guest artist and teacherat the “Sir James Galway International Flute festival and Mas-terclasses” in Switzerland.

ARTIST BIOS

He has recorded for the Italian RAI, the German SDR, theJapanese NHK, the English BBC, the Russian Television andthe Brazilian Television; moreover, Globo Brazilian Televisionand RAI Corporation Television in New York (for the pro-gram “Italiani in America”) have dedicated to him specialswith interviews and live concerts. He has recorded CDs forStradivarius, AS Disc, Hanssler Classic, and four differentCDs for the prestigious Italian magazine of classical music“Amadeus.” He is currently a Delos recording artist.

He has been invited to play with Maxence Larrieu and, forItalian Television, with James Galway. He is a flute teacher atthe “International Academy of Music” of the Foundation ofthe Civic Schools of Milan.

The Milanese pianist Paola Girardi studied at the “CivicaScuola di Musica” in Milan with Lucia Romanini Marzorati,graduating with honors, in 1978, from the “G. Verdi” Conser-vatory in Milan at the young age of 17. She won numerouscompetitions for young artists, among them: The NationalYoung Pianist Competition in Bari and the International Com-petition in Senigallia. She then completed postgraduate stud-ies with Maria Tipo and Konstantin Bogino, and also studiedwith Paul Badura-Skoda attending the “O. Respighi” Acad-emy in Assisi and the Chigiana Academy in Siena, where shereceived a diploma with honors.

Ms. Girardi has given numerous concerts as soloist and in thisrole she has collaborated for two years with the AngelicumChamber Orchestra of Milan and with the Orchestra of theLitta Theater in Milan. She has recorded for Italian RAI, theRAI Television Corporation in New York, and for GloboBrazilian Television.

Pursuing her interest in chamber music, Ms. Girardi hasstudied with the Tchaikowsky Trio, the Quartetto Academ-ica, the Fine Arts Quartet and the Trio of Trieste. During hercareer, she has collaborated with renowned musicians suchas Maxence Larrieu, James Galway and Ilya Grubert, andhas also been pianist for their postgraduate courses in Italyand abroad.

She plays regularly with Raffaele Trevisani, giving concertsin Europe, USA and Japan. She is also his partner in severalCDs recorded for Delos. She is a piano teacher at the “Inter-national Academy of Music” of the Foundation of the CivicSchools of Milan.

Paola Girardi and Raffaele Trevisani live in Milan, and concer-tize together in Italy and internationally. They have been hus-band and wife since 1988.