David Grisman on Jethro Burns Legacy

Transcript of David Grisman on Jethro Burns Legacy

The following interviews were published on the Mandolin Cafe website, commemorating Jethro Burns 100th birthday, March 10, 2020. David Grisman was interviewed by Don Stiernberg and Don was interviewed by Scott Tichenor, proprietor of the Cafe.

David Grisman on Jethro Burns Legacy

What was your first exposure to Jethro’s playing?

I vaguely remember seeing the Homer & Jethro Kellogg’s Corn Frakes TV commercials in (I suppose) the late 1950s. Sometime around 1963 or 64 I bought the Playing It Straight LP at Sam Goody’s in NYC and brought it to my friend Steve Arkin’s house in Brooklyn to give it a listen. When the needle dropped down on the first cut, “If Dreams Come True”, we didn’t realize that the speed was set to 45 and not 33 rpm, so it was playing faster than normal. We didn’t realize this right away because that song is fairly slow, but when Jethro started taking off on his solo with more notes, our jaws dropped! Hearing that record was certainly a revelation as I’d never heard jazz played on a mandolin.

When did you first meet him in person?

Well, Donnie, with you as my witness, I first met the great one at a lesson I booked with him at Main Music in Evanston, Illinois, on a Tuesday afternoon in the summer of 1973. I was planning a cross country trip from the east coast and learned that Jethro gave lessons at that particular music store on Tuesdays, so I called on a Tuesday and booked a lesson, and planned my trip accordingly. It was an amazing lesson, to say the least, and after an hour or so, Jethro poked his head out the door and asked a teenaged kid if he wouldn’t mind waiting a bit, because his current student (me) had come from California. That kid was you, Don! I remember that I was so inspired by Jethro that I bought a set of Black Diamond strings (his brand at the time) and immediately put them right on my F-5! (They were off by the time I got back home!) Several years later, when I started The Mandolin World News, I got in touch with him and asked him if he’d like to contribute, and he generously offered “Jethro Speaks!” which became a regular feature.

Did any of Jethro’s approach to music and the mandolin make it’s way into your style of playing/writing?

Absolutely — and in countless ways. He had a way of combining a very disciplined, focused approach to studying the instrument with pure, light-hearted fun. Aside from stealing licks and trying to learn solos and tunes (which I never really could), Jethro was definitely a role model as a player and as a performer. He was so generous in sharing his wisdom, knowledge and also in the encouragement that he gave me in my efforts to have a career as a mandolinist and composer. And Donnie, this interviewI inspired me to write a “chord melody” tribute to the master, “Ode To Jethro” in honor of his 100th birthday and I just recorded it and its swinging corollary, “Jethro Swings” with Frank Vignola and my son Samson.

Some of your shared history with Jethro happened around Evanston/Chicago--the journey to get a lesson, the (original) DGQ appearance at Pick-Staiger Hall (Northwestern University) where Jethro opened, playing solo mandolin. Any recollections?

I certainly have many outstanding recollections from that time, but here’s a humorous one: When Jethro opened the show for us at Northwestern U., he told a joke about installing a “new” phone message machine, which had the outgoing message, “You have reached the home of the World’s Greatest Mandolin Picker, please leave your message and we’ll get right back to you.” The punch line was, when he listened to the first message, it said “Please have Mr. Grisman call me...” Well, aside being really flattered, I had a recording of that show, and used Jethro’s outgoing message as on my own answering machine!

How would you assess the impact/influence Jethro had and has on mandolin players in general? Were any of his techniques innovative?

Jethro has had an immense impact on us old-timers, (you, me, Sam Bush, Paul Glasse, Andy Statman and many others) and I know that his influence extends to many younger players as well (Aaron Weinstein and his many students). Innovation was Jethro’s middle name as well. Most of his techniques were certainly new when applied to mandolin playing, although many of them can be traced to the great Italian masters of the instrument and the idea of adapting popular tunes of the day formed much of Dave Apollon’s repertoire. Incidentally, Apollon was Jethro’s favorite mandolin player! In my view, Jethro played a major role in the

Don Stiernberg on Jethro Burns LegacyDavid Grisman told us his side of the project. What was it like from your perspective?

The Dawg made it all happen. Lucky for us he saved all of these original tracks. He made a master of everything Jethro and I recorded when the first two CDs were released in 1995 and in 1997) and he kept all of the songs we cut that had never been made public. Good thing because the original analog tapes have just about turned to dust. We found out when he was was having trouble finding one of the songs and he said to me, “you have the masters, can you find it?” I took the tapes to the studio that I work with here in Chicago. They tried to play the originals and that’s how I discovered they’re history. If not for his saving these we would have lost these songs and wouldn’t be having this conversation.

What’s it like for you to listen to this music 25 years later?

Because I was so close to the project and so close to Jethro there’s a lot of emotion in it for me. For the longest time I had a difficult time listening to the CDs and master tapes. It made me sad, but now after all these years with the high definition and remastering I’m having this revelation like, “Oh my God, this stuff was really GOOD!” I hadn’t heard the tunes, the so called “leftover tracks” in years. Hearing Jethro’s ideas again with a fresh set of ears after all this time, that’s one of the things that really makes this exciting for me. He covered a lot of territory on the mandolin. What a brilliant improviser. What was Jethro’s mood like during these sessions?

Each time we got together there would be a little of a warm-up period but that was part of the purpose of the project: he wanted to live and feel alive with his music in spite of what he was dealing with. He knew how much energy and strength he had and he’d pour it all out and when it was time, you knew it was over. It was like his lessons which were never measured in time. He wasn’t a clock watcher. He’d get his pick and stick it in the strings above the nut and say, “Alright” with a smile. That was signal the lesson was over and that would occur at the end of these sessions. And don’t forget, I was playing guitar and hanging on for dear life! We were really flying through this stuff.

Was he gigging during the final months when these cuts were recorded?

There was a bit of a slowdown in terms of the gigs but not much. The last time he played in public was just a few months before he passed. His brother-in-law Chet Atkins was in Chicago for a gig at Orchestra Hall. Chet invited Jethro to be the opening act knowing his circumstance and it seemed planned this would be a nice last appearance for him in front of a large audience. He came out and played solo in his style, told jokes, made fun of Chet, and I believe they played some numbers together at the end of the show. I don’t think anyone in the audience knew he was ill. The nature of his illness was such that he had cancer for three years before it took him and he didn’t want people to know because he didn’t want it to interrupt his work. He played great right up to the end.

What mandolins and guitars were used on these recordings?

At the time Jethro was mostly playing a new Gibson F-5L. Of course I wanted him to use the famous red two-point but it only made it onto a few cuts. I don’t think we used any others. I was using a late 1940s Gibson L-5 and that’s on most of the tracks but I also used a 1938 Epiphone Emperor. It’s interesting that for both guitar and mandolin we all think about how critical the instrument is, what kind of picks, what kind of strings. All these years later — even when the first two CDs of this came out — I can’t tell which guitar or mandolin is being used. For whatever it’s worth, Jethro always used those little thin Fender teardrop guitar picks.

We were surprised to see the inclusion of Django Reinhardt’s “Tears” among the new cuts. We were aware he was an admirer of Django but the selection of this one and the unique arrangement caught us off guard.

Django was his hero. There were a few cats regularly mentioned as influences but Django was always the most frequent. Another one was Dave Apollon. When Jethro met Dave for the first time one of the things they bonded over was their mutual love of Django. They ran into each other by accident at a record store in Las Vegas in the early 60s. Jethro’s story was he introduced himself to Dave. It was in the day when you could

listen to the record in a booth before you bought it so he found one of the Homer & Jethro jazz records in the store and had Dave listen to it. Dave listened to Jethro’s first solo, smiled and said, “Ah, you like Django just like me!” He used to play “Swing ’39” and “Nuages”, but he’d also pull out some lesser known ones like He played a bunch of them on guitar too.

It must have been a proud moment for you when Homer & Jethro were named to the Country Music Hall of Fame.

I was lucky enough to witness their posthumous induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame on October 4, 2001. I was in Nashville for IBMA when the ceremony was held and Homer’s son, Trent Haynes, was kind enough to share an extra ticket to the ceremony. I really wanted to be there because that was one of the things Jethro said was his only regret in music. He used to say to me, “Donnie, I wish we would have made it into the Country Music Hall of Fame.” It was great to finally see the dream realized.

What else would you like to share about the release of this project?

All these years later I’m realizing what strikes me hearing these cuts better than ever before is that this was music he wanted to play. He was playing it the way he wanted to play it and it wasn’t a commercial project. He was doing this just for the love of the music and his wanting to impart his wisdom about the mandolin to future generations. It was like a gift from him. I would hope people take that into account when they listen to it.

His style of playing has something to offer just about anyone interested in mandolin playing. The ideas are subtle and he made things sound easy. He definitely made it look easy and because of that it’s easy to miss how difficult some of it was. If you try to play or transcribe some of his music you quickly find out he contributed a lot to the art of mandolin playing. One of the things David said when we released the first two CDs was, “man, his whole vocabulary is on here!” And it’s true.Listeners will get ample displays of Jethro’s unique virtuosity. From the mandolin player standpoint, what he did with chord voicings, chord-melody and swinging single-note improvised melody lines was completely innovative and unsurpassed to this day.

development of contemporary mandolin playing and should be seen in the context of a great continuum of which we both are, humbly, a part. We all owe him a huge debt!

You produced several of Jethro’s best recordings, and in fact, most of the few from his huge discography that actually are about mandolin playing. Whose idea was it to make Tea For One? Back to Back? Did Jethro ever comment about getting the opportunity to showcase his mandolin playing in those contexts? Any other recollections of those sessions and the associated gigs and hangs?

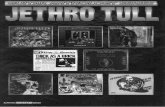

The day I met Tiny Moore (at Tiny Moore Music in Sacramento) and found out that he and Jethro had never met, I drove straight to the Kaleidoscope Records office on my way home and asked them if I could put Tiny and Jethro together and record the album which became Back To Back. Fortunately, they were very enthusiastic about the idea and allowed me to hire the stellar rhythm section of Ray Brown, Shelly Manne and Eldon Shamblin to back them up. I budgeted four 3-hour sessions for the project but they were done in three! It was a real joy to experience — they all were 59 years old at the time and I’ll never forget that Tiny was in tears at the end. Both he and Jethro were blown away by that rhythm section and the fact that a record company cared enough to pull out all the stops! It was also a thrill for me personally to join them on a few cuts which featured three mandolins.

Tea For One was also my idea, inspired by having Jethro as a solo opening act for the quintet. That record was recorded live (with an audience) in the studio to augment a few solo studio sessions without an audience. Again Kaleidoscope Records stepped up to the plate and made it possible. There were quite a few live performances with Tiny and Jethro and my quintet, including The Great American Music Hall in San Francisco, the Paul Masson Winery in Saratoga and the Austin City Limits TV show, which also included the great Johnny Gimble. They were all incredible musical experiences that I will never forget. It was a great privilege to be in the right place at the right time!

Did Jethro ever say anything funny to you?

No never. He was absolutely humorless ... NOT!