David Campbell - Nietzsche, Heidegger And Meaning

Transcript of David Campbell - Nietzsche, Heidegger And Meaning

Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Meaning Author(s): David Campbell Source: Journal of Nietzsche Studies, No. 26 (AUTUMN 2003), pp. 25-54 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20717818 . Accessed: 11/01/2011 16:57Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=psup. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Nietzsche Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

Nietzsche, Heidegger, andMeaning

David

Campbell

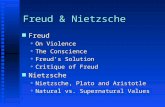

writes more or less unsystematically on many subjects, includ and politics. In this article I explore the pos Nietzsche ingmorality, art, religion, thatenquiry intomeaning unites his thought, so far as anything does. sibility

This topic iswide, but I focus on the suggestion inThe Genealogy of Morality, The Birth of Tragedy,1 and less systematic works of a theoryof interpretation that explains how terms such as "knowledge," "being," and "truth" come to have their meaning and, in cases such as Plato's, as he believes, to lackmean ing. Commentators often takeNietzsche's notion of meaning for granted; in attempting a sustained account, I look at Heidegger both as indebted to him and as responding critically. Thus I do not simply interprettheir writings but treat them as a starting point for analysis and systematic reflection, consis

with what they say. The firstpart of the article considers critically the tently suggestion in theseworks of a virtue ethics, based on self-interpretation,and also of a wider theory of interpretative meaning. The second part examinesHeidegger's comments.

Nietzsche

passively undergoing experiences and reproducing them symbolically in judg ments, but engages actively and in some ways creatively in experience. His starting point is therefore the autonomous agent. He emphasizes this again at the end of thework:

The second section of the Preface toGM declares that "the subject of the present work" is "the provenance of our moral prejudices." Nietzsche's ques tion here, then, is the origin ofmorality.2 Previously, however, in the first sec tion, he had asked how we are to understand ourselves. "We ask . . . 'Who are we, really?'. . .The sad truth is thatwe don't understand our own sub stance" (Preface, ?1). This anticipates his answer to the question of the ori gin ofmorality: itoriginates in us. He goes on to indicate thatour "substance" is in his view "will" or agency. The self is not simply a mirror to theworld,

Journal of Nietzsche Copyright ?

Studies,

Issue 26, 2003 Society. 25

2003 The Friedrich Nietzsche

26

David CampbellUntil the advent of the ascetic ... the ascetic ideal, man, ideal... the animal is and remains man, had no meaning a will. Let me repeat,

at all on this earth

now thatI have reached the end, what I said at thebeginning: man would sooner have thevoid forhis purpose thanbe void of purpose. (Ill, ?XXVIII) Nietzsche suggests, rather than states, a theory of self-interpretation. One understands oneself as interpretingfelt concerns and related abilities in terms of chosen, "willed" projects, particularly one's role. In thisway, one's life as agent has meaning both as felt or qualitative and as structured, and moral terms acquire both their sense and efficacy. He introduces this theory by assuming that there can be natural aristocrats and imagining that they inter

pret their"noble" and "high-minded" qualities and "mighty" abilities in terms of the "highly placed" role of ruler: Itwas the "good" themselves, thatis to say thenoble,mighty,highlyplacedand high-minded contradistinction who to all decreed that was themselves base, and their actions low-minded and plebeian.

... in to be good . . .The ori

gin of theopposites good and bad is tobe found in . . . thedominant temper of a higher,rulingclass in relation to a lower,dependent one. (I, ?11) The meaning of the terms "good" and "bad" is determined "not for a time . . .but only permanently" by the ruler's "decree." In thisway there comes about a common currency of values and social cohesion. This decree is not arbitrary, but a "quick jetting forth" from his character. The source of "supreme" value judgments is, then, the agent, somewhat as water under pres sure jets out a fountain. To find the origin of moral termswe need to look Nietzsche back, so to speak, to character, not ahead to consequences or "utility." dismisses the "lukewarmness which every scheming prudence, every utili

tarian calculus presupposes." He furtherhighlights impassioned agency by castigating its opposite, the "slave ethics" of the "low-minded," as merely passive and reactive rather than active and creative. "Slave ethics requires ... an outside stimulus in order to act at all; all its action is reaction" (I, ?X). speaks of the ruler's "triumphant self-affirmation" (I, ?X), sug that his will would be ascendant in its own terms only, if the cir gesting cumstance of a "pathos of distance" between a natural ruler and "plebeians" did not dictate his ascendancy over them.

Nietzsche

terms they typically deploy such as "pure" and "impure," and their idea of God as "nothingness." Their self-understanding as priests depends on their morbid feelings, and these on physical debility: interpreting

The feelings one interprets have a bodily basis, inwhat Nietzsche calls one's "physiology": in other words, perhaps, one's physical type. His dis cussion of "priests" is furtherevidence thathe operates a theory of self-inter pretation. Their "morbidity and neurasthenia" explain their turningaway from "action," their self-disgust and consequent asceticism, and hence themoral

Nietzsche,

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

27

Granting thatpolitical supremacy always gives rise to notions of spiritual which remindsus of itspriestlyfunction.In thiscon terize itselfby a termtext we encounter supremacy ... the ruling caste is also the priestly caste and elects to charac . . .The

desire for a mystical union with God is nothing other than theBuddhist'sdesire to sink himself in nirvana . . . here has the human mind

for the first time the concepts

pure

and

impure.

profoundand evil. (I, ?VI)

grown

both

thus to deny a role for the self in knowledge. Nietzsche admires this tendency for its part in formingWestern culture (III, ?XXIVff.), but nonetheless he attacks it for enabling those with morbid, feeble will to claim moral author ity and hence political power. His account of moral concepts thus includes a . . .democratic "genealogy of prejudice" (I.IV). Those with feeble passions are herdlike and servile, resent their weakness and their rulers' strength,and each other. "With the eyes of a thief [such a type] looks at everything pity splendid, with the greed of hunger it sizes up those who have much to eat; and always it sneaks around the table of those who give."3

means ascetic; "profound" means reflective, implying "Evil" here therefore the use of linguistic symbols (I, ?VI). Together, these characteristics produce the "will to truth," that is, a tendency to affirm an independent reality sym bolized in judgments that can be tested against it for truthand falsity, and

The uncreative majority, however, is supreme when united and, assisted by priests, codifies and institutionalizes compassion and altruism. In thisway the term "good" comes tomean "bad" and vice versa, and theiroriginal senses are forgotten.Natural rulers acquire a bad conscience, inappropriately feel ing ashamed of their superior qualities and repressing them.Democrats are convinced that their creed has objective natural or divine authority,but such a "spirit of seriousness" ismerely the fug of stifled passion. Altruism is afrom water. "The vermin 4man' occupies the entire stage . . . tame, hopelessly

"sublimate" from this noxious source, like alcohol, for instance, when freed

mediocre, and savourless, he considers himself the apex of historical evolu tion" (I, ?XI). Eventually altruism evaporates into nihilism, that is, loss or denial ofmean

of theweak with the joyful passion of the strong for life. Such proud defiance alone creates

ing and value. Nietzsche speaks of the "death of God" and predicts social fragmentation,with dire political consequences. He does not try to reinstate altruism on a sound footing, however, but answers the nihilistic resentmentmeaning.

eralize this type of explanation, describing any autonomous agent as self characterized; on this basis he explains "values" such as promise-keeping. Thus he envisages a type of individual who, far from being "neurasthenic" and self-denying, characterizes himself independently":

The self-characterization of rulers and priests and reaction of "plebeians" or "slaves" explains only one aspect ofmoral talk.Nietzsche goes on to gen

28

David CampbellThe from has and individual, ripest fruit is the sovereign of custom, autonomous the morality like only to himself, liberated again ... the man who and supramoral the right to make promises? come to comple of mankind ... he becomes on himself not according to consequences

independent, protracted will and a sensation in him a proud consciousness, lies in his own demands tion ... his measure moral. ... He determines himself

his own

authentically

. . .but fromhis beginning. (II, ?11)

One does not acquire good character and a sense of oneself by first taking goals and rules for granted. Instead, one first identifies whatever matters or makes a difference to oneself in particular, and then interprets this "passion" in terms of a role. Somewhat similarly, ifone cares about fine art or fishing, oneself as a budding artistor angler. Nietzsche, for instance, one may interpret however, is concerned with role choice as determining where one's values lie, not where one's talents lie. In fulfilling one's passion one makes explicit the values it implies; a self-interpretation is not derived from preconceived

for instance, on doing distinctively human things such as talking, tickling, or driving fast cars. Goals, rules, and values depend in this sense on choice. For Nietzsche, however, choice is responsible not only as liable to praise or blame but also as a settled response to feelings; it implies that one knows oneself and accepts its costs and benefits. Thus themetaphor of "jetting forth" does not imply thatone's choice is simply voluntarist, like playing the lotteryand winning the jackpot: good character is a prize hard won, commanding a high price and a cause for pride (I, ?VIII). By so interpreting felt concerns in terms of one's role, one also "creates"

values, but forms a background against which one conceives values. As a "jetting forth"of value judgments from one's character, this process is largely emotional and inarticulate rather than calculated and conscious. Values then depend on singling oneself out as author of one's biography, so to speak, not,

oneself: Nietzsche's theory has implications for the nature of the self and its realization, as he notes inGM. One's life gains an aim and narrative struc ture, and one acquires a sense of oneself as of a piece, enduring through time, and bearing rights and obligations. One makes the sense one does of one's life from this first-person stance. There cannot in general be a self that does not make sense to itself,more or less, and one interprets oneself and one's What it is to be a self thus depends on will, exercised in self values together.interpretation.

also explains terms such as "responsibility" and "conscience," togetherwith obligations such as promise-keeping, as expressions of virtu Nietzscheous, "aristocratic" character: "Those who promise [are] like sovereigns

. . .

whose promises are binding because they know that theywill make them . . .His proud awareness of the extraordinary privilege responsibility good. confers has penetrated deeply and become a dominant instinct.. . .Surely he will call ithis conscience (II, ?11). Nietzsche calls thismethod of explaining

Nietzsche.

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

29

moral concepts "etymological": understandably, given his philological train ing. But his "etymology" is also a "genealogy," attempting to show that values originate in character, and that this is a matter of choice or self characterization. Yet this is only one application of his etymological method; it also applies generally to "the objective areas of natural science and phys iology." He excuses himself from showing how, saying, "I cannot enlarge

upon the question now" (I, ?IV), but adds in parenthesis that "[t]he lordly right of bestowing names is such that one would almost be justified in see ing the origin of language itself as an expression of the rulers' power. They say, 'This is this or that' ; they seal off each thing and action with a sound and thereby take symbolic possession of it" (I, ?11). Such lordly "naming" is not a matter of picking out and labeling mean

ingswe perceive as though already formed independently of us. Nietzsche's methods include challenging such assumptions, but itdoes not follow that linguistic terms have in his view only rhetorical meaning. Instead, he seems tomean thatwe "bestow names" in the sense of stipulatingmeanings: words mean what we conventionally want them tomean. Perhaps we can concoct a nonmoral example by adapting his metaphor of the "aristocrat." In this fan ciful example, the term "forest" can be understood by recognizing connota tions with stag-hunting and the like in theminds of "nobles" who reserve theirwoods for such purposes. Just as we have to dig into "etymology" to

rediscover that "pure" meant originally "inactive," so we ordinarily "forget" that the term "forest" was originally interpretedas "hunting ground" and sup pose that it simply means something like "woodland." Thus, to extrapolate from Nietzsche's brief discussion, a "name" does not mean just what the namer wants it tomean, somewhat as words have meaning for Humpty Dumpty. Instead, a "name" initially expresses various connotations in the minds of whoever does the "naming," and so comes to denote convention ally whatever conjures up these connotations, thoughmany are subsequently lost or "forgotten." "Naming" consists neither in labeling preexisting mean ings nor in arbitrarily allocating a denoting use and specific sort of reference to a verbal sign that then over time accrues connotations; instead, denotation presupposes interpretation of objects in terms of interests. In thisway, his account of themeaning of moral terms, based on self-interpretation, gener alizes to a theory of semantic meaning based on interpretationof objects. If

for present purposes we can call self-interpretation"existential" as concerned with personal existence, and interpretation of objects also "existential" as concerned with what it is to be an object to which we refer, Nietzsche can be said to connect existential and semantic meaning. The background to this theory isNietzsche's attack on cognitivist meta physics. He describes themetaphysics of his "great teacher" Schopenhauer as noncognitivist (Preface, ?V). "'Amidst the furious torments of thisworld, the individual sits tranquilly' [while doubting! the cognitive mode of expe

30

David Campbell

pity each other. Nietzsche agrees that there is only a "will to power," as he calls it,which is inherently unstructured and indifferent to us. There is no given, preconceived end or telos that could remove the contingency of "exis tence" and redeem tragedy or justify its pain. But he questions his mentor's

rience" (TBT, ?1, p. 22). There is no ultimate, metaphysical truthor reality that could be a foundation for knowledge, but only a disorderly cosmic will or striving; human beings can do littlebut observe events, renounce self, and

view of "the value of ethics" (GM, 153), denying thatwe need to resign our selves to impotent passivity. Rather, will to power manifests itself in us as interpretation of "passion" or emotion strong enough not to end futility and disorder but, on the contrary, to overcome them by willing their "eternal"recurrence.

Empiricists also, among others, deny the possibility of metaphysical cog nition; but Nietzsche maintains that all cognitive assumptions need to be explained, while they exempt sensory cognition. For empiricists, further, "ideas" and their relationships in thinking derive from sensory experience, where forNietzsche they derive fromwill to power. Unlike them, also, he uses an aphoristic, epigrammatic writing style to exhibit a poetic mode of thinking that does not rely on explicit deductive argument, and to thwart an argued account of his thought. The present article nonetheless tries to see whether such an account is feasible. In general terms,will to power is a commanding drive to use whatever is available as a means to itself: there is in the end only a circle of control and

consumption. The term "power" is here an intensifier and does not indicate an external telos or aim of "will." Metaphysically, this inherently undiffer entiated process manifests itself as spatiotemporal, causally related natural units; conversely, since everything is a means to control, the process has no internal structure of means and ends. For any thing or object, to be is then

for order and meaning to interpret theworld inways that others may share. Truth as the adequacy of statements to represent facts can then be reduced to interpretation in response to constraints. Any number of such interpreta tions or "perspectives" is possible. Here will to power is a nihilistic circle of interpretation that continuously consumes and overcomes itself.The doctrine

not only tomanifest will to power but also to be reducible to it.Nietzsche's doctrine of the eternal recurrence of every state of the universe reflects this circularity,and in this respect is also a metaphysical doctrine. Ethically, virtue answers nihilistic resignation and not only expresses felt control or will to power but also reduces to it.Epistemologically, one is constrained by a need

of eternal recurrence reflects this circularity also. Nietzsche's epistemologi ca! particularism means that talk of knowledge and itsobjects expresses some manifests will to power. perspective or other,which in turn In emphasizing passion and control, Nietzsche hopes to avoid metaphys ical commitment. One reason he attacks Christianity is thathe assumes that

Nietzsche,

Heidegger,

and Meaning

31

it claims metaphysical knowledge. His objection is not to the idea of tran scendence, since his "superman" is transcendent in a sense, as the name implies. Rather, he rejects transcendental arguments such as that theremust be objects outside experience to be mirrored or symbolized within it. most, At these arguments establish thatwe must believe that there are such objects, not that theyexist, and he explains thisbelief by our need for order and mean ing. Thus he questions two assumptions: that there are transcendent objects, and thatknowledge ismerely representation. These assumptions leave unex

plained both the notion of an object, as preconceived, and the notion of knowl edge, as reproducing something preconceived. He proposes to resolve this problem by explaining both knowledge and its objects as manifestations in us of will to power. In effect he distinguishes a judgment as representing fact and as a mental act expressing interest or power. Nietzsche's assumption that any metaphysics must be transcendental and cognitivist may seem unduly narrow; perhaps indeed he himself might be said to hold a metaphysics

hard to swallow, however, so far as theworld is not only a sort of event or manifestation of agency but also there.4Consonantly with his emphasis on will, moreover, Nietzsche thinks of human beings primarily as agents. One difficultywith this is thatwe are onlookers as well as agents, and interpre tation is an occurrence as much as a willed action; hence we can consider

of will or agency. His attack on Christianity is then curious given that will, along with intellect, is forChristians fundamental to the nature of both God and human beings. A metaphysics of sheer will is

such as power over others; as an intensifier, implies thatone copes well. Hence it will to power in human beings is a passion concerned with coping and control, and will in the sense of agency is the basis for choice. Such "choice" implies

things as instruments to ends other than control. For Nietzsche, however, at least afterThus Spake Zarathustra, will to power is our fundamental drive. He calls it "the emotion of command";5 thus it is a "passion" ratherthana psychological faculty.Ithas a bodily basis, and is stronger in some individuals than others. Will to power manifests itselfas felt ability in as distinct from a sense of achievement in completing an doing and making, activity or product. The term "power" does not here indicate an object of will

without effort, but ismade amid struggleand strife. Twilight of the Idols (IX.38), for instance, describes choice or "freedom" as "measured ... by the resistance which has to be overcome, by the effort it costs." Will to power in us is opposed to a spectator's passivity, sustains a feeling

voluntary, intentional action, not freewill: Nietzsche's theoryofmotivation is deterministic, thoughhe is interestedin feeling not simply as a causal antecedent of choice but as embodied and expressed in it. At the same time, such a notion of choice is not voluntarist in the sense thatflipping a coin decides an outcome

of life, and gives rise to virtue. Nietzsche is immor?list in some modes, but in others, and perhaps in the round, he suggests a virtue ethics.6 In his ver

32

David Campbell

sion, enhanced vitality overflows into particular virtues: "[a] heart [which] flows full and broad like a river ... wants to overflow, so that thewaters may flow golden from him and bear the reflection of your joy over all theworld."7 If we are to act virtuously, we must have this feeling, and promote values that sustain it. "Morality grows out of triumphant self-affirmation . . . spontaneously" (GM 1, ?10). "The worth of an action depends on who does it. . . . It is no longer the consequences but the origin of action which deter mines its value" (BGE, Part Two, ?32). A heightened feeling of life, that is, "strong" will to power, brims over into particular virtues, as opposed to either lacking or bottling up strong passion. One is then socially engaged, congen ial, honest, proud (megalopsychos), courageous, generous, just, courteous, exuberant, and playful; and one has presence, energy, sensibility, self-disci pline, and self-sufficiency (?284).8 In the case of generosity, for example,

"The noble human being aids the unfortunate but not, or almost not, from pity, but more from a superfluity of power" (?260). Well-being pours over intowell-doing: one undertakes obligations voluntarily from virtue, and one is accountable to others for discharging obligations only as having under taken them.A difficulty for this theory is that filial obligations, for instance, do not depend in thisway on undertakings. For Nietzsche, however, what gives meaning and value to one's life is a feeling of vitality both strong enough

tomeet its contingency, disorder, and pain and stable enough to persist if it recurred numberless times.9 Affirming eternal recurrence therefore stabilizes strong feeling. On this basis one makes the sense one does of one's life. Emotional debility, by contrast, manifests itself as incoherent self-interpre tation: one's will devises ways of defeating itself, and a vicious life is a botched expression of "weak," resentful feeling. Will to power is controlling, and so also therefore is virtue as manifesting it.Presumably we can cultivate or neglect virtue, butNietzsche does notmean thatwe control our character in the sense that choosing and acting are said to be under our control or "free"; his view of character is determinist. For Hume also the final term inmoral explanation is emotion; but unlike

Nietzsche, themoral standpoint is in his view universal. Moral judgments express "sentiments inwhich [aman] expects all his audience are to concur with him. He must here, therefore,depart from his private and particular sit uation . . . [to] some universal principle."10 For Nietzsche, however, one is virtuous so far as one expresses feeling particular to oneself. Such an ethic

moral obligations, commendations, and so on is particularist in holding that are products of virtuous feeling, not simply of "mechanical" universalizing or deduction from preconceived rules.We grade such feeling on a scale from,say, "excellent"

simply judging the actions "right" or "wrong" by universal rules. In a broadly similar sense, there is no "right" or "wrong" literaryessay. Thus virtues suchas courage, generosity, and courtesy are analogous to one another and form

to "poor"

or, as Nietzsche

says,

from

"strong"

to "weak,"

not

Nietzsche.

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

33

incapable of intellectual wisdom. Thus his ethics is self-regarding like Nietzsche's, though forAristotle, unlike Nietzsche, one's interests include those of family, friends, and fellow-citizens. His account, however, ismore structured thanNietzsche's, since his virtues are analogous as lying at their respective means. He also tabulates an analogy between vices as each in its own way an excess or defect, where Nietzsche has a catchall characteriza tion of vices as "weak," resentful, and self-defeating. But Nietzsche agrees thatethics has no metaphysical telos as its foundation, somewhat as Aristotle rejected Plato's foundationalism. Nietzsche's imperative is to "choose solitude": he associates the univer salist ethics of Utilitarianism and Kant with what is commonly called "moral

implies the thinking (logos) of the practically wise; a courageous act is not simply a reflexive, automatic deduction from a preconceived rule (though Aristotle seems to take for granted rules prohibiting murder, adultery, and so on). The end (telos) of "happiness" consists in so acting, at least for those

a class in that each is in its own way an expression of "strength," that is, heightened vitality in exercising coping skills. Aristotle also is particularist inholding thata virtue such as courage depends on feeling particular to oneself, at a mean between excess and defect that

which he believes his ethic "overcomes." Utilitarians say that actions ity," are right if they produce the best results for themajority regardless of feel ings particular to oneself; Nietzsche would protest thatgenerosity, for instance, is not merely calculated giving, and one ought to keep a promise even if no one benefits. Kant held that one ought to act from regard for duty, not sim ply from feeling; a duty in one situation is a duty in every similar situation,

feltmeaning. According toNagel, we need to distinguish knowledge that a bat navigates by echo location, for instance, from knowing what it is like to be a bat.11For Nietzsche, one could do what one ought for the reason that one ought without being moral, if the actions lack significance or importance for oneself in particular. This is not a matter of suiting one's narrowly per A sonal interest. virtuous person in a situation requiring her to do something rather than nothing typically asks what she ought to do given how she in par ticular feels, not simply what anyone, in the thirdperson, ought to do regard less of such feelings. Thus she keeps a promise because fulfilling such an

and thus objective relatively to us. For Nietzsche this takes a third-person, onlooker's view of action. One's motive then has no meaning of its own that could explain why one would want to act in thisway. One ought to honor one's promise, for instance, because this obligation matters to oneself in par ticular, not simply for the reason that anyone ought to do so. Virtue forNietzsche thus depends on the irreducible first-person stance of

when called on obligation matters to her even if she does not benefit and if, to fulfill it, she is disinclined, throughweariness, for example. To suppose thatwhat Nietzsche calls "passion" ismerely such capricious inclination

34 would

David Campbell

priately request an account either of its content or of why itmust apply to red things. Somewhat similarly, one simply sees thatone ought to keep one's promise, for example. What is particular to oneself on this theory is an intel lectual as opposed to a sensory perception. For Nietzsche, however, ont feels that this obligation matters. Intuitionists fail to explain why one would want to act on one's moral knowledge, but if, as forNietzsche, one cares about one's obligations, such caring explains one's subsequent actions. Nietzsche often contrasted his position with Christianity yet ignored, or failed to spot, an affinitybetween his view that joyful passion for life over comes its inherent senselessness and theChristian view that we can be grate He enlivens his account of emotional "health" by ful for life despite evil. opposing it to religious feeling, which he misrepresents as typically feeble

ted for present purposes, would be too simple. In some ways, Nietzsche's theory resembles intuitionism. The word "red," for instance, is descriptive, but a person blind from birth could not appro

imply a contradiction. Thus to say thathis ethics is narrowly egoistic rather thanmore broadly self-regarding, if such a distinction may be admit

with respecting persons, that is, they avoid malice, lust, envy, and so on; we can be glad for life though we tend to feel these things and, in addition, suffer pain and tragedy. Somewhat as for Nietzsche, one welcomes the eternal

and morbid. He would have been more accurate ifhe had said that Christianity is in his terms "healthy," the highest expression of will to power. Natural feel ings are forChristianity occasions for rejoicing so far as they are consistent

recurrence of one's life, such gratitude is a comprehensive felt intention, not simply a particular natural feeling; though it is also a kind of gift, not sim ply chosen, whereas forNietzsche good character requires heroic effort as well as choice. The grace of gratitude is also particular to oneself from the first-person standpoint, where Nietzsche wrongly assumed thatChristianity imposes a universal altruistic ethic regardless of perspective. Nietzsche calls himself "antichrist" because he believes, to this extentwrongly, thathe opposes misrepresents Christians not only as debilitated but Christianity. He further

also as compensating for their debility by conceiving of moral rules as pro hibitions in order to repress passion. In fact, however, moral rules on their view mark the frontiers of regard for persons, and forgiving others restores

we suppose, contrary to his self-regarding theory, that virtue at least in part concerns one's bearing toward others, and thus presupposes relationship with them. In these respects his ethical theory is then deficient. One might also question whether virtue must depend on feeling, as virtue

the equality disturbed by trespass. Hence this notion of theperson is notmilk and water, as Nietzsche alleges, but offers a means ofmaking sense ofmoral rules, and of uniting them under one concept: a unity that is not available to his theory that recognition of any such rule is simply a voluntary undertak ing. It also provides a more successful test of what is to count as a virtue if

Nietzsche,

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

35

as an end, not simply from felt interest or inclination towhich persons are mere means, and so monitors her feelings for traces of self-regard; but in so denying herself she in fact acts from a warped, ascetic kind of self-interested feeling. His point is not simply that she is deceived or muddled about her motives, but that judgment, unlike feeling, cannot of itself lead to action. The reason why altruism is illusion is that, as Aristotle and Hume put it, "intel lect" or "reason" alone cannot motivate us to act. A problem forNietzsche, however, is thatwhile such a judgment is plainly not a feeling, it is nonethe less typically accompanied by feeling. The Good Samaritan need not have

Nietzsche could reply that pride and humility are tied to what matters or makes a difference to oneself, and character is in this sense a question of feel we suppose thatwe act on judgment alone. An altru ing; we are deceived if ist may believe that she acts on a judgment that the person has inherentvalue

ethicists maintain. Pride and humility, for instance, seem to be matters of judgment concerning one's abilities, whether or not one also swells with a feeling of pride or shrinks with a feeling of humility. As a virtue ethicist,

which lies beyond the scope of this article is whether interpretation articu lates and shapes prior formless, "raw" emotion, or whether what we feel can not be separated in thisway fromwhat we thinkwe feel, expect to feel, andso on.

worth, morality is not simply an expression of feltmeaning or derived from it, as Nietzsche assumes. The notion of meaning is therefore less inclusive than he supposes. A wider question concerning the relation between judgment and feeling,

in a sense, contrary to his intention.This argument cannot be explored ade quately here, but itwould follow thatNietzsche's weakness is not thathe is a self-regarding virtue ethicist, but thathe is a virtue ethicist at all. If virtu ous social feeling presupposes the judgment that the person has inherent

felt compassion for themugged Levite he assisted, but such feeling would clearly have been appropriate. Indeed, Nietzsche believes that the "noble" aid the unfortunate not from altruistic "pity" but "more from a superfluity of power," and such lack of sympathy is from an altruistic stance small-minded

Nietzsche's other systematic work, The Birth of Tragedy, can like GM be regarded as offering a noncognitivist account ofmeaning; here he calls such an account "aesthetic." This work is the startingpoint for his perspectivism. When itwas first published, Nietzsche held that an elite generates an inter pretation of theworld that is then accepted universally. The world is, as he later described it, a seething, formless will to power. Only great artists such as the classical tragedians endure the threat of disorder and, without guide lines, createmyths thatprovide a monolithic order.Their orgiastic "Dionysian" energy and formalizing "Apollinian" principle are at odds except when achiev ing order in an artwork. This process is emotional and hence inexplicable.

For the slavish majority, meaning depends on making this aesthetic standard

36

David Campbell

Nietzsche

its own.12 In thisway, artists redeem our existence from its "terror and hor ror" and provide a socially unifying system of values (TBT, 1872). The aim is not beauty but coping, throughpleasure in the harmony of beauty. Art does not represent an unintended underlying reality but provides a feeling of order thatwe regard as objective once we forget its origin. Art is thereforewhat calls a "metaphysical supplement" that "overcomes" nature and existence." Thus he reduces belief in an objective order to a need "justifies

for control.

(?452). Previously he held that the process of artistic creation is inexplica ble; now an artist's ability is no more miraculous than that of an inventor, scholar, or tactician (HH, ?163). The source of value is thereforenot the artist but his work, whose perspective requires us to rethink our lives. Art does not make a universal ideal of the best in us: rather,we interpretour best accord ing to our perspective. Anyone may contribute to the perspective of some tra dition or other, and realize "the hero concealed within" (JW, ?78). Nietzsche thereforefirst supposed that artists supply a framework of order that is objective relatively to themajority in the sense of being unified rather than particular to individuals. But he later supposed originally instead that anyone can contribute to our interpretation, and it is now partic ular to individuals and their traditions, even when it seems unified.Whether and meaningsuch perspectives are "strong" or excellent, or "weak" and poor, is not deter

However, in his introduction to the later, 1883 edition of The Birth of Tragedy, headed "Towards Self-Criticism," Nietzsche rejects his earlier view thatvalues are universal. There are instead various particular "perspectives"

mined simply by arbitrary choice on voluntarist lines, as though Jack's hill could be Jill's pail, or murder wrong for Jack but right for Jill.A perspective is not merely tied to the individual's need formeaning but takes the form of a tradition or convention to which one contributes. Its criteria of meaning and value are not independent of individuals, yet are objective relatively to them as a tradition is public relatively to its contributors. In a similar way, moral motivation is particular to individuals yet connects with moral judg ment as general in form, and Nietzsche shows how these apparently opposed

particular and universal standpoints can be reconciled. BT and GM together reveal an approach that leads to perspectivism. The term "perspective" has an optical sense, but Nietzsche does not mean that there is a world independent of us that is somehow ambiguous, or indeci pherable, or that all see differently, as a house can be viewed from different sides. He means rather that each has a different notion of "the world," a nar These perspectives may be rative beguiling enough to be mistaken for truth. both incommensurable and compatible, but their fundamental concepts, such the category of "thing," evidently converge. Nietzsche's emphasis on per spectival diversity and self-directing control makes him more liberal politi cally than in othermodes, but his wider point is nonpolitical: each individual

Nietzsche.

Heidegger,

and Meaning

37

relates to his world fromwithin, not as a neutral observer with a 'View from nowhere." At the same time,Nietzsche is not a relativistwho claims that sen tences are true or false only in relation to the parochial perspective they express. Thus any perspective can be criticized from another perspective, so long as doing so is not "offensive" (JW, ?335). But no perspective can be

do as he likes: now all are freewhere justice is done by recognizing theirpar ticular contributions (HH, ?300). Once artists gave universal meaning, and justice was equity: now justice is "love with open eyes," giving each his due

criticized from a supposedly "objective" standpoint that is above criticism rather than perspectival: there is no such Archimedean view. This has particularist ethical implications. Previously the artistwas free to

justice is tied to self-realization, which can take heroic effort, so that a judg ment is an exercise of power, and true if itfits a living perspective; hence tra ditions no longer become ossified, but ideas can be reviewed and invented

from his own perspective. This means treating contributors justly, not per sons equally: Nietzsche consistently rejects such equality.We need this sense of justice to grow in everyone and the instinctfor violence toweaken. Further,

integrated, and resolute, one's sustained joy in living is attractive. One does not thwart felt concerns and desires but interprets them so as to "become what you are," that is, authentic or "strong" (D, ?448). Autonomous respon sibility is also solitary,unlike the relational responsibility of a master or slave,

ary elite determines the rules of justice. Strength now lies in autonomy as well as passion. Autonomy consists in freely choosing a personal "style" that integrates conflicting feelings into "an artistic plan," that is, a sustainable order of pleasures (JW,?290). One's choice cannot be justified safely in advance, for instance by preconceived rules; it involves risk and self-overcoming, as distinct from self-preservation. Since one shapes one's narrative, it is an artwork; values such as honesty and integrity are aesthetic, notmoral or religious. One develops a life-enhancing structure of satisfactions by doing what one in particular cares about. Gifted, proud,

(GM, ?155). This view of justice, as regard for each perspective according to its "strength," suggests an interplaybetween libertyand equality thatpartly subsumes, rather than fully supplants, Nietzsche's earlier view that a vision

for instance; Thus Spake Zarathrustra speaks of a solitary rambler on icy peaks. One detaches oneself from sociocultural forms and ties, including the language inwhich one expresses oneself and the criteria of concepts in it, in order to determine what one's own passions are and express them in a proj ect. Autonomy does not imply independence from such forms, since passions do not arise in a vacuum and projects involve direct or indirect relationships. Somewhat similarly, a passion for football, for instance, implies teamwork

and rules; a researcher relies on professional controls, the contributions of other scholars and a shared specialized vocabulary, and asks others to trust him.13Virtue then concerns an individual's relation to herself as self-deter

38

David Campbell

mining, true to herself, and so on, not her relation to others; but while self interpretationplays a central role inNietzsche's account of virtue, this does not entail that she can just choose either herself or her character: not only is good character won by long hard labor, as noted earlier, but she also does not just choose the ethical language inwhich she expresses herself and the cri teria of concepts in it,as forHumpty Dumpty words mean just what he wantsthem to mean.

Although Nietzsche takes an aesthetic rather than a religious view of val ues, his shift from a universal to a particularist stance has a religious ana majority logue. The medieval world picture was transmitteddownward to the by a priestly hierarchy, and claimed a universality that ruled out dissent; later the priesthood embraced all believers, whatever their particular experience and point of view. Nietzsche somewhat similarly argues that an elite, unified sense of theworld leads to social instability and mediocrity; excellence or

virtue and social harmony depend on perspectival diversity. This analogy is confirmed by his evoking medieval practices such as self-flagellation to attack altruism as ascetic, though weakened by the fact that both earlier and later religious doctrines demand self-denying altruism. Previously, Nietzsche had asserted thatculture depends on slavery.He does not now do so, not simply because he wants individuals to be treated justly but also because he no longer assumes uniform standards and needs themas

ter-slave distinction to explain them.His target is still the "objectivist," cog moral judgments are true if theyfit "moral facts" such as nitivist theory that that lying, stealing, and killing are wrong. He rejects the theory that these are facts, as distinct from the nontheoretical belief that the actions are wrong:can attach no sense to the notion of such

we

edge of it. Indeed objectivists themselves differ inwhat they call right or good, reflecting different agendas. The source of difficulty is the assumption thatknowledge claims in general, not only claims concerning ethics and the Will to power is fundamentally a matter of physics self,fit preconceived facts. and biology, but here, at the level of human motivation, it concerns knowl edge. Human beings feel a need for stable meaning and control and, tomeet this need, create the "fiction" of thingsor natural units; thusknowledge claims

a nonsensory

"fact"

or knowl

"The most dangerous of all errors,"Nietzsche says in thePreface toBeyond Good and Evil, is "denying perspective." A piece of knowledge does not sim ply fit fact, but serves powers or interests, that is,will to power. "There are no things (?they are fictions invented by us)."15 The notion of an occurrent object presupposes its interpretation as an instrument that,according toGM,

reduce to interpretations of experience: "I set apart with high reverence the name ofHeraclitus. When the rest of the philosopher crowd rejected the evi dence of the senses because these showed plurality and change, he rejected their evidence because they showed things as if they possessed duration and . . . [He] will always be right in this, thatbeing is an empty fiction."14 unity.

Nietzsche.

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

39

we subsequently "name." For instance, what it is for a tree to be is explained by potentialities for, say, food, shelter, and fuel.We give meaning to judg ments about an actual tree by interpreting such potentialities as a group; it is not as thoughwe could first reproduce the fact of there being a tree symbol ically in a judgment such as "This is a tree" and then investigate the predi cates. This direction of explanation also means thatwe firstunderstand any object in relational terms: for example, wood is first serviceable, then cellu lar. Judgments ascribing physical properties depend for their meaning on cer tain sorts of relational judgments, and these in turndepend for their meaning on interpretativecoping skills. The same statement may thenboth correspond

with fact and provide an adequate interpretation, and the questions what the thing also is "in itself," and whether italso exists "in itself," apart from inter pretation, are misleading. Hence talk of "things" is "fictional" or conven tional. A routine objection to what we may here loosely call linguistic conventionalism is that while it may purport to explain the variability of con as "east" or "work," it fails to explain the invariability of logical, cepts such

mathematical,

and categorial concepts. Nietzsche could possibly reply on perspectivist lines that such a dichotomy need not be exhaustive: there can be indefinitelymany incommensurable but compatible kinds of linguistic convention, each with its own cluster of public criteria and type and degree of rigidity or flexibility. This reply fails, however, so far as invariability is not a type or degree of rigidity.

time; in parallel fashion, he holds thatwords mean what we want them to mean conventionally rather than voluntaristically. We ordinarily speak of "existence" in connection with spatiotemporal, causally related objects, how ever, not with their prior conditions such as will to power. Thus to say that an object exists is not to indicate its independence but to express in conven tional form our intention to speak of unity, causality, and so on. In thisway, Nietzsche defends ordinary talk of real things against doctrines such as Plato's concerning an unintended metaphysical reality. The theory of will to power

Nietzsche claimed to have "abolished Being." He does notmean thatnoth ing exists: will to power exists, and is finally all that there is. He is not an mind creates a world from nothing, so to speak; idealist who believes that the it is down to us that things are serviceable, and thus that they are as they yet are. To this extent his view is both controlling and nonvoluntarist at the same

both explains such ordinary talk in the sense of supporting it as useful illu sion, and at the same time explains such metaphysics in the contrary sense of undermining pernicious illusion. Nietzsche's aim, however, is not merely to distinguish useful and pernicious illusions. Even while vindicating ordi nary talk, he does not leave itundisturbed, but finally reduces it to a mani

festationof will to power. Like "metaphysics," itattempts to control knowledge and truthby conceiving of things as existing independently. He therefore replaces both ordinary and metaphysical ontological assumptions with an

40

David

Campbell

account of their origin, namely, the attempt to objectify Being "anthropo morphically."16 "We can say nothing about the thing itself.... A quality exists for us. . . .Knowing is nothing but working with the favourite metaphors. But in this case first nature and then the concept are anthropomorphic. . . . We produce beings (Wesen)."11Hence any belief thatBeing, knowledge, and truthare independent of art, that is, the art of interpretation, is illusion.18To say that there are thingswith properties and so on makes sense only as mean Talk of things ismetaphorical, not ing that it is as (/"thereare such things.19 as hinting at their independence, but in conveying the intention to talk in this

way. Nietzsche therefore explains such talk by its force or "will to power." This is not to say that linguistic meaning reduces to rhetoric, but that it is a matter of conventional "naming," as he calls it inGM. Since there is in the end only will to power, it is in this sense impossible to speak with a straight face about knowledge of "Being" or objective truthand reality. Nietzsche's defense of ordinary talk of thingsmight appear to contradict he his view that these are fictions; further, might be supposed to offer a the ory of truth that tries but fails to resolve this contradiction. But there is no we assume that he aims at a theory of meaning, not of such contradiction if

For he can then be said to take the coherent line that truth is a product truth. of interpretation,useful for ordinary talk but, philosophically, a fiction rather than a subject matter towhich one could refer literally, or about which one could intelligibly theorize. "Metaphysicians" suppose thatknowledge is contingent on a foundation notion. of truth; but truth is on the contrary a contingent, not foundational,

The notion of an unintended reality is a perspective, but one that lacks many such meaning: a fiction in the sense of a lie. There could be infinitely of experience: Plato, Locke, and Kant, for example, all in their interpretations differentways assert an unintended reality. Nietzsche thus "abolishes" the notion of reality as the subject matter ofmetaphysics inPlato's mode of read ing off, and recasts it as an expression of perspective without the imprimatur of fixed and final "truth."His suggestion is then that the criteria of knowl

with the theory so expressed is that it fails to explain the difference between saying that the painting really is a work of art, not kitsch, for instance, and that it really is a painting, not, for instance, an illusion or hallucination. Nietzsche would reply, however, that this distinction has no systematic appli cation; it concerns only specific cases of deception, and any perspective can

edge are aesthetic in that a perception is objective, not illusory, for instance, meets its implicit public criteria, somewhat as we are not misled about if it whether a certain painting by Rembrandt really is a work of art.A problem

be criticized from the standpoint of another. what you are doing Nagel points to a parallel contrast between "a sense that is . . . important to you . . . [and that it is] important in a larger sense: impor tant, period."20 Such a "larger" meaning is not only synoptic and final, as

Nietzsche.

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

41

or ten Nagel indicates: it seems also to have dramatic unity and heightening sion, togetherwith qualitative or emotional richness and depth. Thus for a romantic or pantheist, a landscape, for instance, can seem to convey a mes sage thatdoes not quite form itself intowords, having what might be called a quasi-literal symbolic meaning somewhat like a printed page, as distinct

frommetaphorical meaning whether as frost patterns look like leaves, for instance, or as when we say it is "as if the landscape has meaning. For Nietzsche, on the other hand, theworld is a disorderly will that surges up in us as a superabundant energy and feeling of health or wholeness. The narra tives we subsequently invent have internal unity and give a deceptive sense of truth but, as merely perspectival, have no systematic application. Heidegger, unlike Nietzsche, connects such a feeling of wholeness with intimations of universal rather than perspectival significance. At the same time, he followed

Nietzsche's

noncognitivism; whether such meaning should instead be under stood cognitively, as romantics, for instance, assume, is a wider question that cannot be investigated here.Will to power, then, is "meaning" forNietzsche not only in this specialized sense but also in the senses inwhich we speak

variously of the "meaning" of art, religion, science, politics, morality, and the self, as well as of knowledge, language, being or objectivity, and truth.

Heidegger The theory of meaning thatwe have attributed toNietzsche was made more explicit by Heidegger. We need not, however, examine his debt or expound his theory inmore detail than is required to show where his view of tech nology diverges in general fromNietzsche's theory of will to power, as the background to his more specific criticisms. According toHeidegger, I lack reason to exist in the sense of actualizing a preconceived end, yet try tomeet such contingency by actualizing 'one' (das Man), that is, by acting as anyone would inmy circumstances; however, I am authentic or genuinely myself only so far as I interpretand choose pos

sibilities particular tomyself. So far he and Nietzsche agree, but where Nietzsche demands solitude, Heidegger assumes social interaction. I cannot perceive my possibilities except against a background of universal everyday

as a human being is to stand out from oneself as interpreter to receive and express the existence of particular things.Man is 'being-in-the-world' since subject and object are united in him before they are distinguished (BT, 33). Heidegger's metaphor for themind is a forest clearing, where light enters

concerns, so that I have littleoption but to remainmostly inauthentic.He ties this notion of self-interpretation to interpretation in general.21 To exist as a thing is to stand out or emerge intodisclosure, through interpretation; to exist

42

David Campbell

unhindered and surrounding trees and other objects are disclosed; the dis closure of things, and of man towhom they are disclosed, are co-original. Self-interpretation is thus tied to interpretation of things as instruments to felt concerns; Heidegger calls concern in general 'care' (Sorge). Aristotle attributed Being only by analogy in the various categories of thing, relation, and so forth,22 but care lets us make a project of ourselves inwhich every has itsmeaning, so unifying themeaning of Being. thing We cannot be said simply to believe (or desire, think, and so on) butmust,

The term "technology" might suggest only bridges, computers, and so on, but Heidegger has inmind techne in general, that is, art or skill as a form of

logically, believe something or other; hence phenomena can have no under lying unintended reality. Objects are in the first instance available or handy forprojects (zuhanden), not simply occurrent (vorhanden): judgments ascrib ing physical properties depend for their meaning on certain sorts of relational and these on interpretativecoping skills, that is, on "technology." judgments,

knowing. Here knowing is not conceived simply as an act of reading off that is complete at any moment, but as implying a degree of understanding that can be greater or less, depending as it does on a dynamic process of first interpretingpotentialities instrumentally, then interpreting these instruments as having theirown potentialities for furtheruses, and so on in a kind of pro gressive loop. Experience has a fivefold structure that depends on art and thus on technology (BT, 97-104). Tools form a context, such as a factory, to

which products give unity; nature yields material and power that are "before" us in leading to their uses; science aims at a theoretical understanding of material objects; and intersubjectivity,that is, the social organization of labor, means that there is always someone who knows what a particular tool is for. This structure concerns production and utility, and lets us cope by distin guishing what is and is not serviceable, and the human from the nonhuman or natural. Thus it provides a spatiotemporal context: objects are "near" if available and serviceable, "distant" ifnot; theyhave a "past" as already mat tering to us, a "future" as ahead of us in roles, and are "present" as disclosed in tasks.What is initially indeterminate is assigned a role: how things such as leather or shoes are depends on our interest in there being such things, that is, as Heidegger says, on themeaning of theirBeing.

puters work, and so we have power without relating to them as objects over against us. The premodern view, derived fromAristotle, was less subject to this tendency. Artifacts such as tools were only means to ends determined independently; for instance, money has no value inherently but only as a

Technology "lets things be" as instruments,much as will to power does forNietzsche; but forHeidegger, unlike Nietzsche, things are not reducible to instrumentality.Our tendency to reduce things tomere means is itself an expression of will to power, and we need to rescue a sense of the being of things from this tendency. For instance, most of us do not know how com

Nietzsche

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

43

means to other goods.23 Thus preindustrial technology could reveal the struc tureofmeans and ends. The danger is now that the distinction between means

problem. Technology "enframes" or gathers together and arranges nature while rejecting the deviant and recalcitrant. This involves a will tomastery that thwarts and conceals rather than discloses the Being of things and of

and ends disappears in technological systems.24 Technology has become self referential, having a role only for rational organization, so thatends are sub sumed tomeans and instrumentality. The problem is control with a view not to utility but to power. Nietzsche failed to see that such control presents a

nerable nowadays, encountering ourselves as essentially meaningless and merely anxious about what we are. "Nowhere does man today any longer encounter himself, that is, his essence" (QT, Krell, 308). Yet this anxiety is our "saving power" since it indicates our plight, and we can counteract will

enjoy the sort of happiness that consumption and control can yield, but one has no basis for a goal or narrative that could give a sense of oneself. Technological control is, in otherwords, overbearing.We are at our most vul

human beings (QT, 300ff.): "Everywhere everything is ordered to stand by [as] standing-reserve [and] no longer stands over against us as an object [but] disappears into objectlessness" (QT, 298-300). For example, the system of air travel is from the technological standpoint a process of control. Aircraft are not objects in theirown right; similarly, the passengers merely so to speak fuel the system and are not subjects in their own right.One may perhaps

tomastery by reflecting on our role in technology.We are not mere means within a technological process but have a hand in it; conversely, we can inter pretwood, for instance, as supplying cellulose tomake paper (299-300), yet it is not down to us thatwood has this potentiality. Further, it is not simply down to us ifwe interpretnature for our purposes, but also a potentiality in us to do so. Thus we can be open to themeaning of things and of human exis tence, which are then illuminated and articulated, and we are enlightened. The problem with technology is psychological, and only indirectly philo sophical, in thatwe are disposed by the history ofWestern philosophy since

Socrates to think of things simply as instruments (QT; also OWA, 162-66). Plato explained changeable ordinary things as copying their eternally pres ent Forms; for an object to be depends on an unintended realm of Being. This tendency to objectify Being as inert "presence" was modified by Descartes so that for something to be means for it to be present to the human subject.25 For scientists, the role of the human subject was then to extend knowledge in order towin benign control of nature. In thisway we come to reduce Being and knowledge to instrumentality; Plato's defense of Being led to its aboli tion. Heidegger thinks thatNietzsche is right to seeWestern philosophy as

finally nihilistic, but wrong to see Plato's aim of defending Being as mis guided.26 Nietzsche's perspectives merely express psychological attitudes, whether concerning worldviews (Weltanschauungen) such as a particular

44 Dasein

David

Campbell

might assume, or systems of particular historical epochs such as Platonism, Aristotelianism, Cartesianism, and so forth.That is, philosophi cal systems as perspectives are what Heidegger calls "ontic," not as Nietzsche to which his reduction could apply. We escape supposes ontologies nihilism by providing an alternative foundational account of Nietzsche's

Being to Plato's,27 namely, that technology provides not only control but also truth in the sense of phenomenological disclosure of Being (aletheia). Thus, for instance, water is experienced as wet, even though this experience is inseparable from its instrumentality as thirst-quenching, lubricating, and so forth. Such a notion of truthas disclosure contrasts with truthas independ ent of the human subject.28 saw that forNietzsche will to power and eternal recurrence have no but subsume ends as mere means, and are in this nihilistic sense cir telos, cular. Yet willing eternal recurrence makes truthfulnessor integrity,creativ We

ity and joy, possible, and thus the annihilation of nihilism. If his theory of will to power is applied consistently, however, these ends also are subsumed as mere means, and in this respect their claim to "overcome" such nihilism is not sustained. Heidegger's reading therefore fits better thanNietzsche's and creativitymight seem to suggest. Heidegger agrees insistence on integrity that things are means, but not that they are mere means. Nietzsche reduces

meaning but tomeaninglessness. Five detailed comments on Nietzsche arise fromHeidegger's discussion of technology. These concern truth, the categories, existence, and choice. First, the process of interpretationconnects us to things as intentional objects means for them and us to exist. For both writers, such and lets us say what it a process implies 'Becoming' as distinct from 'Being.' But forNietzsche, Becoming

but talk of theBeing of things to instrumentality, we cannot talk about a world at all, even to say as Nietzsche does that it ismetaphor and illusion, without an interpretative structure of ends, and in general of things, in so to speak their own right. Nietzsche does not reduce Being and truth to interpreted

actualization possible. Nietzsche tried to reduce Being-talk to a mythopoeic psychological and physiological process; but ifeach particular thing ismerely a phase, so to speak, in a process of control, nothing can be said to exist in its own right,and true-or-false judgments about things are impossible. Thus What Nietzsche thinks ismere will tomastery has no grasp of Being or truth. talk formed by felt interests, forHeidegger concerns what there is, namely, the Being of objects disclosed in a world not simply of our making. Mind and world clarify each other in a "hermeneutic circle" of what he calls "objec

makes talk of objects is prior toBeing: the process of interpretation provisionally possible, but finally impossible. For Heidegger, on the other hand, the process of Becoming does notmake Being only provisionally pos sible, but lets beings or thingsfinally be. InAristotle's terminology,but revers ing his direction of explanation, the potentiality to be a thingmakes its

Nietzsche

Heidegger,

and Meaning

45

nature, theory,and social organization for their actualization. Up to a point, Heidegger's argument follows roughly Nietzschean lines. Aristotle held that the actuality of a thing is its end (telos), fulfilling and thus explaining the potentiality to be that thing. For Heidegger as forNietzsche, the reverse is the case: potentiality, not actuality, explains the thing. We can understand things by means of the art (techne) of interpreting and so dis

There must be something to interpretprior to our interpreting,a potentiality not of our making and not fully under our control. Nietzsche fails to draw this distinction: will to power has two aspects at once, thatwhich we inter pret and the activity of interpreting it.For Heidegger, on the other hand, we free something that is a potential tool to become an actual tool, and products,

it so exists; yet we do not bring hammers and computers into existence out of nothing. Thus Heidegger is not an idealist who holds that to be is to be perceived, and that the notion or narrative of "the world" is simply a yarn spun as itwere from nothing by themind and wrongly credited with truth.30

tive subjectivity."29For instance, it is not down to us that a stone is service able as a makeshift hammer, though it is not a hammer unless we so inter pret it.How we read theworld is not how it is, like interpretinga Rorschach inkblot.Tautologically, the hammer cannot be said to exist as a hammer before

What it is for a tree to be is explained closing their"possibility" or potentiality. for, say, food, shelter, and fuel; their actualization as fruit, by potentialities planks, and firewood derives from these (speaking logically rather than causally). We do not firstpicture, as itwere, or reproduce symbolically, the fact that this is a tree in the judgment, "This is a tree," and then investigate the potentialities for fruit and so on. Rather, by interpretinga certain set of potentialities as instrumentalwe give meaning to judgments concerning the

even if Nietzsche explains the sense inwhich a particular hammer, for instance, might really be an artwork in some genre, this is not what ismeant by say ing that it really is an object as distinct from an illusion. Heidegger in effect escapes this sort of charge since, on his view, how a stone can be a hammer for certain purposes is not as forNietzsche simply down to us but, as he putsit, "withdrawn" from us.

actual tree.Hence producing meaning is prior to reproducing facts in judg ments. For Heidegger, however, such an account leads to a notion of irre whereas Nietzsche understands truthreductively and finally ducible truth, mean eliminates it; thus his theory is incomplete. Indeed any argument that is prior to truth has to fail, since these are equiprimordial. In otherwords, ing

Similarly,Heidegger broadly agrees that truthin the case of occurrentmate rial objects is a property of judgments that correspond with fact. For this test to apply, such judgments must already have a meaning, disclosed in under standing objects as available. For instance, I do not need to thematize a cer tain hammer as an object unless itbreaks and needs to be repaired. Its felt meaning, as meeting needs, is a prior condition of rational assumptions and

46

David

Campbell

pretation, and it ismisleading to ask what the thing is "in itself," and whether it also exists "in itself," aside from appearances.31 But Heidegger goes on to maintain in effect thatNietzsche wrongly confuses the question of how a judgment such as "This coat is yellow" is formed, that is, of the conditions of itshaving meaning, with thequestion whether it is trueor false. Nietzsche's reductive theory implies that the perception of color, for instance, is illusory because it relies on interpretation,and the distinction between truthand illu sion applies to specific cases, not systematically. Heidegger contends in reply

oblique way: ifwe are to understand p, for instance, the statement "This is a hammer," theremust be a degree of agreement as to whether is true. makes this sortof point inPhilosophical Investigations, 2A?-A2.) (Wittgenstein But the same statement may then function both as a judgment and as an inter

procedures concerning the fit of judgments about itwith fact. 'The pointing out which assertion does is performed on the basis of what has already been disclosed" (BT, 199). This is not to say that the reverse does not hold in an

of categories, but simply to establish an irreducible categorial structure. Nietzsche, on the other hand, explains categorial structure provisionally but finally undermines it. Third, one could also extrapolate fromHeidegger's theory to reply in a similarway toNietzsche's treatmentof existence or Being. Nietzsche explains

such identity, so that it is interdependent with but not derived from them. Heidegger therefore explains the structure that experience must have if it is to be intelligible, in accordance with the categories of "thing," "prop erty," "relation" and so on. As he says, "The goal of all ontology is a doc trine of categories" (IM, 187). He does not aim to provide a complete list

ing of an orange, say, as a natural unit that is also edible, but does not make it either edible or a unit. Thus the unity is underived, and interpretation lets us understand the underived identity of individual things. In Heidegger's terms, the categories of availability and occurrence are equiprimordial with

sional objects. The second comment concerns categorial structure. For Nietzsche, will to power is inherently undifferentiated, and objects as natural units derive from it, just as they reduce to it.A difficulty he faces is that unity or self identity seems to be underived and irreducible. As Heidegger puts it, "Over . . the against appearance being is the enduring . always identical" (IM, On Heidegger's theory,by contrast, interpretationdiscloses themean 202).

that the fact that I can experience an illusion, such that it is false to say that I see a yellow coat, does not mean that it is ultimately false, a fiction or mere convention to speak of yellow coats, or generally of colored three-dimen

the existence of things by their origin in the process of 'Becoming,' that is, will to power. A difficulty is that existence seems underived and irreducible. In Heidegger's words, "Over against becoming being is permanence ... the already-there" (IM, 202). This problem is compounded forNietzsche ifhe

Nietzsche.

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

47

thing about what ismeant by saying that things exist, but it fails to explain what it is for them to exist, so far as that concerns what we must necessar we are to say anything at all. ily, not simply conventionally, say if

figuration of will to power. But the latter,as the basic character of beings, as the essence of reality, is in itself that Being which wills itselfto be Becoming."32 Thus Nietzsche's account of things as "fictions" may ormay not tell us some

assumes that the process of will to power exists, since its 'being' is then log ically prior to its 'becoming' : "Art as will to semblance is the supreme con

unified meaning escapes Nietzsche's reduction. Further, Nietzsche replaces a nihilistic response to contingency with an affirmative response, so sus taining his reduction. Thus his strategy for dealing with a nihilistic attitude is also an attitude, that is, the same kind of thing,on the principle that it takes a thief to catch one, so to speak. In these terms,Heidegger's strategy seems less effective: he adds a different sort of thing, namely, a doctrine of cate gories, in order to avoid Nietzsche's reduction (on the ground thatwe can not conceive of a world, even as contingent, without them).

Heidegger makes these points concerning truth,the categories, and exis tence without offering extended supporting argument, at least in their imme diate context. One might wonder whether in that case his own doctrine of

If all of this suggests a standoff,however, the dispute does not quite end here: there are also doubts about the reductive form of Nietzsche's argument. For Nietzsche, our ascribing objective authority tomorality is caused by debil

These claims assume that a causal explanation for a belief invalidates it by reducing the explanandum to the explanans. In some such way, a man's claim thatwhisky is good for him might be redefined as no more than an expres sion of his desire to drink, that is, as an oblique comment on himself, not the comment on whisky it might seem. But a difficultywith this is that a correct causal explanation need not either invalidate or validate a belief; in that case, there is no ground for reducing the belief to its explanation. Being motivated by a desire to drink does notmake a man's belief that whisky is good for him either fanciful, if, for example, alcohol assists tired heart muscles, or alter natively true, if, for instance, he is an alcoholic. Indeed reductionism as a form of argument is self-defeating, since eliminating the explanandum also

ity;hence any such authority is illusory. Similarly, the belief that things are independent of us is an illusion explained by our need for order and control.

by implication eliminates the explanans, there being nothing then that does any explaining. Whether or not these objections are conclusive, there does seem to be a residual problem between Nietzsche and Heidegger that iswider than their stated arguments.

We conclude with the fourthcomment, which concerns choice. Disclosure depends on intentional acts, and Heidegger seems to have inferredwrongly inBeing and Time that this involves thewill or choice. He went on to regard

48

David

Campbell

without labor somuch as thatchoice is now uncontrolling.We do not "seize" themeaning of Being and "wrest" it from everyday prattle as inBeing and Time; instead, we "wait" with docility and "listen" attentively to Being. His

disclosure as instead an event or occurrence (Ereignis), unlike an action that iswilled or chosen.33His account ofmeaning here is often described as "non voluntarist," but Heidegger does not mean that choice determines character

Heidegger concludes that "Man is not the lord of beings. Man is the shep herd of Being" (LH, 221). We can become less controlling by using the pre Socratics and poets such as H?lderlin to illuminate theworld and bring the meaning of Being into resolution (Entschlossenheit) in the sense perhaps of optical focus; though the fine arts and similar activities are "marginal" and cannot easily become the focus of attention in a technological age. Thus

declaration that "Only a god can save us" is not religious but metaphorical: in some such way, Plato did not will his profound effect but was inspired.34

Heidegger distanced himself furtherfrom the controlling will to power that he found inNietzsche. Heidegger assumed thathis general theory is connected somehow with his social and political beliefs, and some commentators look between the lines

throughout his writings for theNational Socialist agenda that is explicit in places (such as IM, 42, 50). We need now to look at these beliefs as the back ground to his 'turn' (Kehre) toward an uncontrolling account of technology. One early anxiety about technology was that factoryworkers were in effectan extension of machines; today employees are often defined as "human

lem here or various sorts of problems, some perhaps more theoretical than others. Some questions might well be political, concerning pay and condi tions of work, for instance, or the right not to be dismissed unfairly; others managerial, concerning, for instance, damage to an employee in her relations with colleagues and clients by arbitrarily changing her role. Heidegger, how

resources," for instance, and thus by implication treated like resources such as raw materials and equipment. Heidegger thought that in such ways our humanity or, as he said, our spirituality is distorted,marginalized, and ignored. A fuller discussion of his view might well consider whether there is one prob

trial rationalization destroys the sense of an enduring community and place He with a common language and history.35 meant that "ethnic" Germans could lead mankind back to true spirituality. (Ironically, this folksy reaction soon found itself industrializing ways of killing people, in battle and "camps") Human meaning is in any case essentially historical, notArchimedean; accord ingly, a certain nostalgia is true to civilized values and conserves the best in us. Indeed in harking back to the pre-Socratics he went beyond nostalgia;

ever, assumed that there is one general kind of problem and, initially, that it is political, though having to do with what we now call moral education rather thanwith rights and the like in employment. He upheld the folk values of crafted implements and rustic cosiness (Gem?tlichkeit), suggesting that indus

Nietzsche

Heidegger,

and

Meaning

49

and his attempts to ground such meaning historically in language were often weakened by overstretched "etymology," as he liked to call it.