DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

Transcript of DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

1/26

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?Paula Gerber and Brennan Ong*

This article examines how dispute avoidance processes (DAPs) are being

widely used around the world to prevent and/or manage constructiondisputes. Despite glowing reports, and the unprecedented success of DAPsat the international level, the process remains in its infancy in Australia. Thisarticle analyses the barriers that have prevented greater use of DAPs inAustralia, and considers how these can be overcome.

INTRODUCTIONSince the curtain closed on the first decade of the 21st century, we reflect on a significant movementthat was, not that long ago, viewed as the most exciting development to hit the constructionindustry.1 At the start of the new millennium, it was predicted that dispute avoidance processes(DAPs) which include dispute review boards, dispute adjudication boards and dispute resolutionadvisors would soon become widespread throughout the construction world, and the days ofacrimonious arbitration and litigation as the way of resolving construction disputes would be relegatedto the history books.2 Although alternative/appropriate dispute resolution (ADR) is now popular, andalliancing is increasingly used on major projects, the Australian construction industry remains plaguedby adversarial attitudes that create an us versus them environment, conducive to costly anddrawn-out disputes.3 Although DAPs have a proven track record of using proactive and real-timetechniques4 to prevent and manage conflicts that arise during construction, they have not enjoyed thedegree of support that one might expect from the Australian construction industry.5

The use of DAPs, in particular dispute boards (DBs), has seen exponential growth in the UnitedStates as well as the international arena.6 Since DAPs are a successful tool for keeping parties out ofexpensive and time consuming construction litigation and arbitration,7 it is timely to ask why theAustralian construction industry has not embraced DAPs and if this will change anytime soon.

This article seeks to answer these questions by exploring why the construction industry is prone todisputes and why it is notoriously litigious when it comes to resolving those disputes. This is followedby an analysis of the theoretical and practical aspects of DAPs, and the variety of models in usearound the world. The authors then explore the barriers to the greater adoption of DAPs in Australia,and conclude with a discussion about what can be done to help Australia join the DAPs revolution.

NATURE AND EXTENT OF CONSTRUCTION DISPUTESBefore one can begin to prevent and manage construction disputes, it is essential to have anunderstanding of the underlying causes of disputes. Therefore, the authors commence their analysis byseeking to expose the provenance of construction disputes.

* Dr Paula Gerber: Senior Lecturer in construction law at Monash University Law School. Brennan Ong: Research Assistant atMonash University Law School. This article is based on a presentation by the authors to a workshop organised by the DisputeResolution Board Australia (Sydney, 10 April 2010).

1 Gerber P, Dispute Avoidance Procedures (DAPs) The Changing Face of Construction Dispute Management (Part 1)(2001) International Construction Law Review 122 at 129.

2 Gerber, n 1 at 122.

3 Jones D, Project Alliances: (Why) Do They Work?, Paper delivered at the International Bar Association Conference (Durban,24 October 2002); Harmon KMJ, Construction Conflicts and Dispute Review Boards: Attitudes and Opinions of ConstructionIndustry Members (2004) 58 Dispute Resolution Journal 66 at 68.

4 Duran JE and Yates JK, Dispute Review Boards One View (2000) 42 Cost Engineering 31.

5 Jones D, Construction Project Dispute Resolution: Options for Effective Dispute Avoidance and Management (2006) 132 Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering and Practice 225 at 266.

6 Gould N, Establishing Dispute Boards: Selecting, Nominating, and Appointing Dispute Board Members , Paper delivered at theDispute Resolution Board Foundations 6th Annual International Conference (Budapest, 6-7 May 2006).

7 Loots P and Charrett D, Practical Guide to Engineering and Construction Contracts (CCH, Sydney, 2009) p 312.

(2011) 27 BCL 44

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

2/26

Conflicts and disputes

Figure 1 illustrates the traditional path of a construction conflict from inception to final resolution.Left unchecked, a conflict during the course of construction can readily escalate into a contractdispute, and from there to arbitration or litigation.

FIGURE 1 The Conflict-Dispute-Litigation Continuum

Within the construction industry, the terms conflict and dispute are often used interchange-ably when in reality they have distinct meanings. Many definitions of conflict exist, 8 but because ofthe interpersonal relationships present on any construction project, the most appropriate definition isperhaps best expressed as a situation that arises when individuals are faced with competing goals orideas.9 Given that many construction projects begin with the principal wanting the project completedfor the lowest cost, and the contractor wanting to maximise its profit, it is apparent that potential forconflict is present before ground is even broken. Add to that the multiplicity of people involved in aproject, all of whom have differing responsibilities and priorities, and the risk of conflict escalatesexponentially.10 Conflicts that remain unresolved are often formalised into claims, which has beendefined as:

A Contractors submission of a formal request to the Engineer (or the Employer) under the provisionsof the Contract or under the common law, for additional time or money arising out of circumstances orevents concerning the execution of the Contract.11

If claims are not settled through amicable settlement procedures as outlined in the contract, theyare readily transformed to disputes. Disputes therefore concern justiciable issues disagreements overthe existence of rights or legal duties, and over the extent and kind of compensation that may beclaimed by a party for an alleged breach.12 Thus, conflicts can be said to fall within the discipline ofpsychology and involve peoples opinions, attitudes and understandings of a situation, whereas

disputes fall within the discipline of law and involve the assertion of legal and/or contractual rights orentitlements.

Unfair risk allocation

Unresolved disputes often mature into formal legal processes, complete with disruptions and monetarylosses that impact directly on the successful completion of a project. There is a large body of literatureregarding the myriad of causes of construction conflict, including attitudinal differences,13 embitteredrelationships,14 and, in Australia, even the industrys male-centric genderlect.15 Most agree that it isthe operation of the construction contract that fosters high incidences of conflict.16 One of thefundamental functions of a construction contract is to allocate risk. However, at the time the contract

8 See generally Dana D, Conflict Resolution (McGraw-Hill, New York, 2000) pp 1-16.

9 Dana, n 8, p 8; Wilmot WW and Hocker JL, Interpersonal Conflict (5th ed, McGraw-Hill, Boston, 1998) p 1.

10 Pickavance K, Delay and Disruption in Construction Contracts (2nd ed, LLP, London, 2000) p 27.

11 Loots and Charrett, n 7, p 279.

12 Martin R, Construction Industry Disputes: How Did We Get Where We Are? (1989) 5 BCL 89.

13 Awakul P and Ogunlana SO, The Effect of Attitudinal Differences on Interface Conflicts in Large Scale ConstructionProjects: A Case Study (2002) 20 Construction Management and Economics 365; Gluklick E, Why Every ConstructionProject Needs a DRB (2002) 57 Dispute Resolution Journal 21.

14 Yiu TW, Forces to Foster Co-operative Contracting in Construction Projects (2007) 18 ADRJ 112.

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 5

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

3/26

is entered into, it is often difficult to accurately predict the risks that may be encountered on any givenconstruction project.17 Although the Abrahamson Principle that a risk should be borne by the partythat can best manage, minimise or transfer that risk18 has been around since the 1970s, it is stillcommonplace for risk allocation to be lopsided,19 which is likely to significantly increase the risk ofconflict during the project. Standard form contracts have attempted to redress this imbalance, but they

are often heavily amended,20

skewing the risk in favour of the party in the strongest bargainingposition. Trust, which is essential for the successful completion of a project, is difficult to promote ifat the outset the risk allocation is fundamentally flawed, thereby positioning parties in a constant stateof confrontation.21 Further, in the modern world of competitive tendering, the polarisation of goalsbetween a contractor and principal is further misaligned, with contractors forced to tender with smallermargins, thereby encouraging them to resort to opportunistic practices22 in the hope of recouping theirlosses. Claims for contract price adjustments become common place,23 further straining the relationsof all involved.

Perceived bias of the superintendentMost Australian standard form contracts are administered by a superintendent, who is also often theproject architect or engineer.24 As conflicts arise on a project, and ensuing claims are made, theresulting decisions of the superintendent are binding, unless overturned in a subsequent arbitralprocess.25 This process of the superintendent, who is paid by the principal, imposing binding decisionson the parties, has been criticised because of the difficulty of rendering impartial decisions. 26 Moststandard form contracts contain a provision which stipulates that the superintendent act reasonablyand in good faith.27 Even in the absence of such express words, it has been held that there is animplied term in construction contracts that the superintendent will act fairly and justly and with skill

15 A recent study concluded that there is a high incidence of conflict in the Australian construction industry because it is verymale dominated. It is argued that conflict can be reduced by increasing female participation and feminising communicative andbehavioural responses to conflict. See Loosemore M and Galea N, Genderlect and Conflict in the Australian ConstructionIndustry (2008) 26 Construction Management and Economics 125.

16 Fenn P, Lowe D and Speck C, Conflict and Dispute in Construction (1997) 15 Construction Management and Economics513.

17 Dorter J, Representations, Risk and Site Conditions (2004) 20 BCL 7.

18 Wassenaer A, In Search of the Holy Grail; Taking the Abrahamson Principles Further (2006) 1(4) Construction LawInternational 11.

19 Gluklick, n 13 at 21.20 Bell M, Standard Form Construction Contracts in Australia: Are Our Reinvented Wheels Carrying Us Forward? (2009) 25BCL 79 at 80.

21 Groton JP, Alternative Dispute Resolution in the Construction Industry (1997) 52(3) Dispute Resolution Journal 48.

22 Love PED et al, A Systematic View of Dispute Causation, Paper submitted to Building Research and Information for theCooperative Research Centres Guide to Leading Practice for Dispute Avoidance and Resolution (2008), http://www.construction-innovation.info/index.php?id=1086 viewed 10 December 2009.

23 Thompson RM, Voster MC and Groton JP, Innovations to Manage Disputes: DRB and NEC (2000) 16(5) Journal ofManagement in Engineering 51; Capper P (edited by Uff J and Odams M), Overview of Risk in Construction in RiskManagement and Procurement in Construction (Centre of Construction Law and Management, Kings College, London, 1995)pp 11-80.

24 Dorter, n 17 at 7.

25 For example, see AS 4000, cl 47.2. This refers to the requirement that in the event of a dispute, the superintendent can givea written decision on the dispute, together with its reasons. If either party is dissatisfied with the superintendents decision, the

dispute is referred to arbitration or litigation. See Aibinu AA, Ofori G and Ling FYY, Explaining Cooperative Behavior inBuilding and Civil Engineering Projects Claims Process: Interactive Effects of Outcome Favorability and Procedural Fairness(2008) 134 Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 681.

26 For example, see AS 4000, cl 1 and Annexure Part A. This refers to the requirement that the superintendent is the personappointed by the principal as named in Annexure Part A.

27 For example, see AS 4000, cl 20. This refers to the requirement that the principal is bound to ensure that the superintendentacts reasonably and in good faith.

Gerber and Ong

(2011) 27 BCL 46

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

4/26

to both parties to the contract.28 Regardless of whether the contract contains an express or impliedprovision regarding a duty to act impartially as between the parties, there remains a commonperception amongst contractors that the superintendent consciously or subconsciously prioritises therights and interests of the person who pays its fees that is, the principal.29

Evidently, this perceived lack of procedural fairness in the administration of constructioncontracts has been a significant drawback to the resolution of conflict. It contributes to the adversarialenvironment that compels construction project participants to adopt animus attitudes that impactnegatively on the successful completion of a project. A 2008 empirical study examining the effects ofperceived procedural fairness (or lack thereof) in the determination of construction claims found:

There was lower intensity of conflict and lower potential to dispute against unfavourable outcomeswhen the procedure for administering claims was perceived to be fair than when the procedure wasperceived to be unfair. Regardless of outcome received, contractors cooperative behaviour could beenhanced by administering the contract in fair ways.30

Although various factors31 have been identified as contributing to adversarial relationshipsbetween parties to a construction project, it is the absence of a perceived impartial bona fide on-sitedispute avoidance/resolution mechanism that is embraced by all participants, that most polarises theparties and facilitates the festering of conflict and disputes.

WHY PREVENTION IS BETTER THAN CURE

Several decades ago, a growing body of global research began preaching the merits of preventativemedicine. For example, an American Surgeon Generals report noted an emerging consensus amongscientists and the health community that the Nations health strategy must be dramatically recast toemphasize the prevention of disease.32 At the same time, Europeans were urged to quit smoking, startexercising and adopt healthier practices.33 The medical profession has recognised that it is cheaper andeasier to help people quit smoking than to treat lung cancer. Applying this philosophy to construction,the authors argue that it is time for the Australian construction industry and construction lawyers tochange their focus from treating the cancer that construction disputes represent, to actively promotingpreventative measures. As former United States Chief Justice Warren Burger eloquently stated:

The entire legal profession lawyers, judges, law teachers has become so mesmerized with thestimulation of courtroom contest that we tend to forget that we ought to be healers of conflict. 34

Construction lawyers can play a key role in healing conflicts by recommending DAPs to theirclients, and including appropriate clauses in construction contracts. As Figure 2 demonstrates, DAPsare designed to operate as a circuit breaker, preventing the escalation of conflicts into disputes,whereas ADR generally operates as a circuit breaker only after a dispute has matured and is well onthe path to litigation or arbitration. DAPs are the legal equivalent of preventative medicine, and arebased on the idea that, although conflict may be inevitable, disputes and their protracted resolution arenot.

28 Perini Corp v Commonwealth of Australia [1969] 2 NSWR 530 at 536.

29 Jones, n 3, pp 225-235.

30 Aibinu et al, n 25 at 690.

31 Awakul and Ogunlana, n 13 at 365-377; Loosemore and Galea, n 15 at 125-135; Fenn et al, n 16 at 513-518.

32 Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Healthy People: The Surgeon Generals Report on Health Promotion andDisease Prevention (1979) p 7.

33 See Abel-Smith B and Maynard A, The Organization, Financing and Cost of Health Care in the European Community,Commission of the European Communities, Social Policy Series No 36 (Brussels, 1979).

34 Burger W, The State of Justice (1984) 70 American Bar Association Journal 62 at 66.

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 7

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

5/26

FIGURE 2 Interrupting the Conflict-Dispute-Litigation Continuum

DAPs models

Just as ADR is the umbrella term that encompasses different forms of dispute resolution beyondarbitration and litigation, DAPs is the umbrella term used to describe a myriad of dispute preventionmechanisms that are being used on large-scale construction projects around the world. Each DAP

model shares similar features of being established at the commencement of a project for the purposeof preventing and managing disputes during the course of construction. However, the mechanismsused to achieve this goal vary with each model.

It is important to note that DAPs are not a substitute for the superintendent, who still has theresponsibility for carrying out the traditional duties of independent certification, including assessingprogress claims, extensions of time and variations. Rather, DAPs are designed as a readily accessibleresource that the parties can access during the course of the project to minimise or resolve conflicts,and prevent their escalation into disputes. The DAP models that have gained traction around the worldand are analysed in this article are: (1) dispute review boards (DRBs); (2) dispute adjudication boards(DABs); (3) combined dispute boards (CDBs); and (4) dispute resolution advisors (DRA). Models (1)to (3) are collectively known as DBs.

The dispute board or DB35 is the most prominent DAPs model, and is promoted in variousdifferent forms depending on the organisation advocating its use. Other models have also gainedtraction in different parts of the world which share many of the DBs characteristics and procedureswhen it comes to dispute avoidance. Each DAP model shares virtually identical procedures andtheoretical underpinnings regarding dispute avoidance; where they differ is the way they deal withdispute resolution when the parties have been unable to avoid a dispute. The following sectionexplores the dispute preventative rationales and workings of DBs before delving into the nuances anddifferences of each model.

Dispute boards

The primary purpose and benefit of any DB is its ability to avoid disputes and their associatedramifications by addressing the problems frequently encountered on construction projects. A DB isgenerally described as:

[A p]anel of one or three suitably qualified and experienced independent persons appointed under theContract. Its function is to become and remain familiar with the project at all stages, and to be availableat regular intervals to confer with the parties to assist in the avoidance of disputes, or if necessary to

provide a determination on a dispute referred to it.36

As shown in Figure 3, whether a DB is successful in avoiding disputes is dependent on fiveinterrelated factors, each of which is explored below.

35 The DRB is generally accepted as the original DB model, on which all later models are based.

36 Loots and Charrett, n 7, p 286.

Gerber and Ong

(2011) 27 BCL 48

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

6/26

FIGURE 3 The Essential Elements of Dispute Avoidance

Procedural fairness

The superintendents dual responsibilities in acting as an agent for the principal and independentcertifier is inherently problematic, and contributes to the adversarial personas adopted by thecontracting parties. In addressing this perceived bias, all DB models empower both the principal andcontractor to collectively appoint the DB members. The three most commonly used methods formember selection of a three-person board are: Joint selection: The parties meet and discuss potential DB members and jointly agree on the

composition of the three-member DB. The parties or the members themselves may decide whowill be chair.

Nomination by each party: Each party nominates one DB member, subject to the other partysapproval. The two selected members then nominate a third member, subject to the approval of

both parties, who typically serves as Chair. Slate of candidates: Each party proposes a list of three to five potential DB members. Each party

then select one candidate from the others list. A new list is submitted if either party rejects anentire list. The two selected DB members select a third person from the original list, subject toapproval by both parties, to be Chair of the DB. 37

These methods are in stark contrast with the process of appointing a superintendent, which iscontrolled exclusively by the principal. Further, the manner in which the board members areremunerated also addresses the concerns of bias, as member fees are typically shared between theprincipal and contractor.38 It is for this reason that DBs are perceived as being neutral andindependent, while a superintendent is perceived as representing the interests of the principal.

The composition of the DB is also an important consideration in dispute avoidance and alleviatingany perception of bias. Parties are implored to select DB members based on their experience andtechnical competence in the type of construction being performed.39 This places the DB in a greater

37 The DRBF publishes a Practices and Procedures Manual that contains a comprehensive description of the DB concept and auser guide detailing the recommended DB procedures and a member guide detailing best practice guidelines for the use of DBmembers: DRBF, Practices and Procedures (2007), http://www.drb.org/manual.htm viewed 31 July 2010 (DRBF Manual).

38 The DRB, as advocated by the DRBF and ICC, recommends that the contractor and principal split costs 50/50. Under FIDIC,the fees are paid by the contractor who can in turn claim 50% back from the principal.

39 Duran and Yates, n 4 at 31.

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 9

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

7/26

position to understand the potential complexities of the project, and how to prevent such problemsfrom occurring. Parties dissatisfied with a superintendents determination are able to refer the disputeto the DB, with the knowledge that the DBs determination is not only based on the members owntechnical competencies, but shall be based solely on the provisions of the contract documents and thefacts of the dispute.40

Working knowledge of project issues

Litigation, arbitration, and mediation have become time intensive and costly endeavours, owinglargely to extensive fact finding and attempts to understand events that most likely occurred manyyears ago. DBs, however, are implemented at the commencement of the project,41 and the DBconducts site visits and meets regularly with the contracting parties and in caucus as a panel, so as tobecome highly conversant with the project.42 It has been noted that:

It is not prudent to rely on photographic and video evidence [for resolving disputes] since they have aneditorial point of view and can be altered [there] is difficulty in knowing if a photograph or videorepresents the rule or the exception.43

DBs, by witnessing the technical and physical conditions prevailing at the time of the dispute, areable to overcome the difficulties of ex post facto determinations and avoid the expensive task ofreconstructing historical events.44 Regular site visits and meetings also encourage frank and opendiscussions about contentious issues by the parties with the DB members.45 This, coupled with the

DBs familiarity with the project, means the DB members are well positioned to understand theprojects unique characteristics, which strengthens the DBs ability to identify potential conflicts early,and help the parties avoid disputes. On this note, the DB can, with the agreement of the parties, beasked to give an advisory decision46 to assist the parties on an issue, such as the correct contractualinterpretation, which may be preventing the settlement of a dispute. Such a course of action may meanthat formal hearings regarding this issue will be unnecessary.47 This is just one example of how DBscan work proactively to assist the parties to manage and resolve conflict.

Fostering positive relationships

A successful construction project requires an amicable working relationship between the contractingparties. However, parties often adopt adversarial attitudes that flow from poor communication,distrust, misunderstandings, misinterpretation of contracts, and an us versus them posture based onan imbalance in risk allocations. A study that analysed 24 construction disputes in the United States48

found that parties, when faced with a problem, choose either to compete or co-operate. Which path

they take is determined by their working relationship and perceptions of each other. Competitionoccurs when either party acts on the belief that mutual gains are not possible or will not be shared

40 DRBF Manual, n 37 at [2.10.5].

41 These are known as standing or full-term DBs. FIDIC also provides the option of ad-hoc DBs which is when a DABis formed only after a dispute arises. This has been subject to much criticism as the DB philosophy is highly dependent on theearly establishment of a DB. Ad-hoc DBs therefore pose many problems: First, it is difficult for parties already in a dispute toagree on amendments to the contract. Secondly, it is also difficult for the appointed DB panel to catch up on what happened inthe previous years; to deal with the old, usually complex disputes and at the same time with potential disputes. Its function asa dispute avoidance procedure will be significantly compromised. See Genton PM, The Role of the DRB in Long TermContracts (2002) 18(1) Construction Law Journal 8.

42 Jones, n 3, pp 225-235.

43 Altschuler MJ, Seeing is Believing: The Importance of Site Visits in Arbitrating Construction Disputes (2003) DisputeResolution Journal 36 at 42.

44 Chapman P, Dispute Boards for Major Infrastructure Projects, Paper presented at a seminar on the use of Dispute Boards

(Queensland, 30 November 2006).45 Altschuler, n 43 at 36.

46 DRBF Manual, n 37 at [2.10.5].

47 Chapman, n 44.

48 Mitropoulos P and Howell G, Model for Understanding, Preventing, and Resolving Project Disputes (2001) 127(3) Journalof Construction Engineering and Management 223.

Gerber and Ong

(2011) 27 BCL 410

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

8/26

equally, whilst co-operation involves parties seeking to make the overall project function moreeffectively, and are willing to compromise for the projects success.49 Thus, an initiative such as a DB,which promotes a positive working relationship between parties, will increase the likelihood that whena problem arises, the parties will co-operate rather than compete, thereby furthering the projectsgoals.50

Although contractual provisions alone cannot maintain good relationships between parties on aconstruction project, there is evidence that the presence of a DB fosters positive relationships becauseit signals to all parties that potential problems and disputes will be addressed in a fair manner.51 ThusDBs proactively promote an atmosphere of trust that is necessary for successful communicationamong project personnel.52

Reduction in claims

In the modern world of competitive tendering, there is potential for contractors to plague the projectwith frivolous issues and non-meritorious claims that waste everyones time. Another benefit of DBsis that their mere presence motivates the parties to resolve issues in an efficient and timely manner inorder to avoid having to bring the dispute before the DB.53 The relationship between the parties andthe DB:

makes it harder for people to bring claims, and particularly frivolous [ones] that they dont truly believein, to the panel usually the claims that end up coming to the DRB are only those about which there

are legitimate, difficult disputes that the parties cant legitimately resolve amongst themselves.54

This change in the parties behaviour appears to stem from a desire to maintain their credibility infront of the DB.

Efficient dispute resolution

While the primary function of a DB is to avoid disputes, it also functions as a real-time disputeresolution system in the event that a dispute cannot be avoided. The longer parties are enmeshed in adispute, the harder it becomes to reach a compromise because disputants become entrenched in theirpositions, and are wary of losing face despite the resultant negative effect on working relationshipsand the drain on financial resources.55 DBs make it possible for the owner and contractor to agree todisagree, knowing their claims will be resolved by the board. This allows both parties to continue withthe project without the adverse relationship that often arises.56 In other words, the parties canconcentrate on the project confident that the dispute will be resolved in a fair and timely manner bythe DB.

The ability to call upon the assistance of a DB to resolve disputes contemporaneously helpspreserve the relations between the contracting parties which may assist them to avoid future disputes.Disputants are encouraged to approach the DB when either party recognises that a conflict isescalating, thereby allowing the DB to resolve the matter before either partys position becomeshardened.57 Although there are procedural differences in the way disputes are addressed by each DBmodel (discussed below), they all have in common the aim of resolving disputes while the project isstill underway, rather than after completion. The proximity of the hearing to the dispute allows greater

49 Mitropoulos and Howell, n 48 at 223.

50 Mitropoulos and Howell, n 48 at 224.

51 Duran and Yates, n 4 at 31.

52 Jones, n 3, pp 225-235.

53 Harmon, n 3 at 73.

54 As quoted from a survey respondent (whose background was in construction litigation) in a study that examined the attitudesand opinions of construction industry members towards the DRB. See Harmon, n 3 at 73.

55 Brown BR, The Effects of Need to Maintain Face on Interpersonal Bargaining (1968) 4 Journal of Experimental SocialPsychology 107.

56 Coffee JD, Dispute Review Boards in Washington State (1988) 43 Arbitration Journal 58.

57 DRBF Manual, n 37 at [6].

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 11

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

9/26

certainty to prevail, and parties are usually satisfied that all information germane to the issue has beenrevealed.58 It is the parties satisfaction and support in the DB process that aids in the prevention offurther disputes.59

Dispute review board

The DRB was the first of the DB models. It originated in the United States when the Army Corps ofEngineers introduced it to overcome frequent conflicts on tunnelling and dam projects, where thepotential for unforeseen ground conditions led to a high incidence of disputes.60 The first accepted useof a DRB was in 1975, on the second phase of the Eisenhower Tunnel in Colorado.61 The three majordisputes that arose during the project were each resolved by the DRB prior to practical completion. Itis therefore not surprising that in the following decade, DRBs were employed on four more projects,worth over US$66 million.62

The DRB concept was further developed and promoted by the American Society of CivilEngineers (ASCE), which in 1989 published a comprehensive Three-Party Agreement and DRBspecifications (the 1989 ASCE Guide). This Guide was updated in 1991, and again in 1996. Many ofthe people involved with the publication of these guides were also responsible for the publication ofthe subsequent Construction Dispute Review Board Manual, a book which explains the benefits,points out the pitfalls, describes the procedures, and provides guides and specifications necessary toimplement the DRB process.63 In 1996, because of the profound success of the DRB concept, the

Dispute Resolution Board Foundation (DRBF)64 was formed to promote use of the [DRB] process,and serve as a technical clearinghouse for owners, contractors, and board members in order to improvethe dispute resolution process.65 Although the DRBF is headquartered in Seattle, Washington, it nowoperates globally such is the vast worldwide acceptance of DBs.

In 2004, the DRBF published a Practices and Procedures Manual (PPM) which providesspecifications for DRB members and assists users in effectively employing the process. The PPMserves as a revision to the 1996 DRB Manual, and constitutes the fourth generation of documents thattrace their lineage to the 1989 ASCE Guide. The PPM is designed to be an authoritative andup-to-date explanation of the dispute board process66 and is frequently updated in recognition of thecontinual evolvement of the DRB concept.

58 Gerber, n 1 at 126.

59 The parties satisfaction and support in the process is critical in the prevention of further disputes as, unlike an arbitrator or

judge who walks away from the reference after the award or judgment, the members of a DB remain with the project untilcompletion. Impartiality and objectivity are vital qualities and should not be compromised or appear to be compromised for theDB to continue to work. See Chapman, n 44.

60 Duran and Yates, n 4 at 31.

61 Although the earliest reported use of a form of DRB (then called a Joint Consulting Board) was on the Boundary DamHydroelectric Project in northeastern Washington in the 1960s, the genesis of the more common use of DRBs occurred on thesecond phase of the Eisenhower Tunnel in Colorado. See Shadbolt RA, Resolution of Construction Disputes by DisputesReview Boards (1999) 16(1) International Construction Law Review 101 at 104; Bramble BB and Cipollini MD, Resolution of

Disputes to Avoid Construction Claims A Synthesis of Highway Practice (National Academy Press, Washington DC, 1995)p 20.

62 The DRBF provides statistics for both DRBs and DABs. See DRBF, Database, http://www.drb.org/manual/Database_2005.xls, viewed 10 December 2010 (DRBF Database).

63 American Society of Civil Engineers, Avoiding and Resolving Disputes in Underground Construction (Technical Committeeon Contracting Practices of the Underground Technology Research Council, 1991) pp 45-60; Matyas RM, Mathews AA,Smith RJ and Sperry PE, Construction Dispute Review Board Manual (McGraw-Hill Construction Series, New York, 1996);Gerber P, Book Review Construction Dispute Review Board Manual (1998) 60 Australian Construction Law Newsletter 34.

64 The DRBF originally stood for Dispute Review Board Foundation and initially sought to promote the DRB concept only.However, considering that DRBs were being used outside the United States, DRBF voted unanimously to pursue a name changeto the Dispute Resolution Board Foundation and promote all forms of DBs. See The Dispute Resolution Board Foundation,Changing Our Name to Dispute Resolution Board Foundation (2002) 6(1) Dispute Resolution Board Foundation Forum 1.

65 Coffee, n 56.

66 DRBF Database, n 62.

Gerber and Ong

(2011) 27 BCL 412

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

10/26

If parties are unable to avoid a dispute, they can refer it to the DRB for a formal hearing. TheDRB hearing is more like a site-meeting than a trial, and does not generally involve lawyers or expertwitnesses, because the DRB members have been selected for their expertise in the type of projectbeing undertaken.67 Both parties are afforded an opportunity to explain their position regardingcontentious matters in dispute and allowed to forward correspondence and other materials that may

help the DRB to reach a conclusion.68

The end product of the DRB hearing is a non-binding recommendation that is issued within atypically short time frame as set out in the contract specifications, or as determined by the DRB.69 Forexample, Florida Department of Transportations standard DRB operating procedure provides that theDRB is to issue a recommendation within 15 working days of the hearing.70

The DRBs recommendation outlines how the issue should be settled and is written so as toconvince both parties to accept the merit recommendations, and to facilitate a negotiated quantumsettlement when needed.71 The recommendation therefore supports, rather than supplants,negotiations between the parties. Even if a DRB recommendation is not followed, parties are betterpositioned to achieve settlement since they are able to use the DRBs report to further negotiations.72

Proponents of the DRB approach actually contend that the recommendation is often accepted by bothparties because they are aware that the recommendation is highly informed, from experts in the field,

and made in light of the DRBs extensive experience on the project.

73

The DRBs commitment to a non-binding recommendation makes it the most daring of all DBmodels in transforming the adversarial culture that has historically plagued construction projects. Itrepresents a paradigm shift away from the traditional focus of binding dispute resolution, in favour ofdispute avoidance and management, which encourages issues to be resolved at project level withouttraditional adversarial attitudes. The DRB represents the high watermark of the DB method, andembodies the ultimate commitment to collaborative and co-operative working relationships.

The most convincing argument for the use of DRBs is the fact that they work. From 1975 to 2007,1,373 United States construction projects were recorded as having used a DRB, with 810 of theseprojects complete as at 30 December 2007.74 Of these:

51% had all disputes resolved at site level without requiring any DRB hearing;

49% required a DRB hearing; and

97% were settled without the parties having to resort to any formal resolution.75

These findings demonstrate that DRBs are not only an efficient and successful mechanism for avoidingdisputes, but also an effective system of dispute resolution in the event that a dispute cannot beenavoided.

67 Gerber, n 1 at 126.

68 DRBF Manual, n 37 at [2.6].

69 DRBF Manual, n 37 at [2.7].

70 Florida Department of Transportation, DRB Operating Procedures, http://www.dot.state.fl.us/construction/CONSTADM/drb/OperatingProcedure.shtm viewed 31 July 2010.

71 DRBF Manual, n 37 at [2.8].

72 McKillop A, Dispute Review Boards Help Settle Disputes During Construction (2003) AACE International Transactions 1at 4.

73

Jones D, Construction Project Dispute Resolution: Options for Effective Dispute Avoidance and Management (2006) 132 Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice 225; Gould, n 7.

74 As complete and reliable data for projects undertaken post 2001 are not available due to a lack of reporting, only projects witha construction start date on or prior to 2001 have been included. See Menassa C and Mora FP, Analysis of Dispute ReviewBoards Application in US Construction Projects from 1975 to 2007 (2010) 26(2) Journal of Management in Engineering 65;DRBF Database, n 62.

75 The DRBFs database was dissected and analysed with the results presented in Menassa and Mora, n 74 at 65-77.

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 13

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

11/26

Dispute adjudication board

The International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC), a prolific publisher of standard formcontracts for large international projects, introduced the DAB in response to the condemnation of thedual role being performed by the engineer as both the employers agent and independentcertifier/decision-maker. 76 In 1999, FIDIC published three major sets of Conditions of Contract (theRed, Yellow and Silver Books), all of which contained DAB provisions. 77

The DAB is, in effect, the European cousin of the DRB, and mirrors its aims, objectives78 andprocedural practices in avoiding disputes. The predominant difference between the two concepts is thatif a dispute is referred to a DAB, it makes a binding decision (unless and until it is overturned byarbitration),79 rather than a non-binding recommendation as is the case with the DRB. The parties thusempower the DAB to make decisions with which they will comply. Consequently, the DAB procedureinvolves a more formal approach than that which is utilised by DRBs. When seeking the assistance ofthe DAB:

a formal notice of dispute must be issued to the DAB by either party;

the DAB has 84 days to make its investigations, conduct a hearing (if required) and provide areasoned decision;

if either party is dissatisfied with the decision, it may give notice of dissatisfaction within 28 days;

if no notice is served, the DABs decision becomes final and binding; and

where a notice is served, parties are required to attempt to settle the dispute amicably, before thecommencement of arbitration not earlier than 56 days after the notice of dissatisfaction. 80

These strict protocols can delay the involvement and/or decision of the DAB to the detriment ofthe project. Because of the binding nature of the DABs determination, FIDIC has chosen to regulatethe operation of DABs in considerable detail. As a result, the informality and speed that is so crucialand advantageous to DRBs has been forsaken in favour of a more thorough and rigid procedure. Thisincreased formality has the potential to increase the hostility between the parties because they maybecome more entrenched in their positions.81 This perhaps explains why many FIDIC users aredeleting the DB provisions or, if obliged by funding institutions to retain the DB clause, ignoring itonce the contract is signed and fail[ing] to appoint the DB.82

76 The DAB first appeared in FIDICs 1995 Orange Book(Conditions of Contract for Design-Build and Turnkey). Subsequently,

test DAB provisions were added by Supplements, to the Red Book (Conditions of Contract for Works of Civil EngineeringConstruction) and the Yellow Book (Conditions of Contract for Electrical and Mechanical Works) before being formallyreleased in FIDICs 1999 Conditions of Contract (Rainbow suite of contracts). See Jaynes GL, FIDICs 1999 Editions ofContract for Plant and Design-Build and EPC Turnkey Contract: Is the DAB Still a Star? (2000) 17 InternationalConstruction Law Review 42 at 45; Ndekugri I, Smith N and Hughes W, The Engineer Under FIDICs Conditions of Contractfor Construction (2007) 25 Construction Management and Economics 791.

77 Although the DAB was a mandatory provision in the 1998 Test Editions of the contracts, the 1999 official release provided foroptional ad-hoc DABs in the Yellow and Silver Books, designed to be established only after a dispute has arisen and typicallyonly exists until it issues a decision on that particular issue, while only the Red Book provided for a mandatory standing DAB,established at contract commencement and is at play even before a dispute arises. See Jaynes, n 76 at 42.

78 Similar to a DRB, the Red Book incorporates a full-term DAB, comprised of one to three members, appointed at the start ofthe project.

79 The DAB approach stems from FIDICs traditional view that a binding determination is needed to progress the construction.See Jaynes GL, The Role of the DAB, Paper delivered at the Institution of Engineers of Irelands training and assessment courseon Dispute Adjudication Boards (Dublin, 19-22 January 2004).

80

FIDIC, Conditions of Contract for Construction 1999, cl 20.4.81 Boucly J-F, The Different Types of Dispute Boards, Paper delivered at the Dispute Resolution Board Foundations 8thInternational Conference (Cape Town, 2-4 May 2008).

82 FIDIC has established an Update Task Group charged with reviewing the three main FIDIC contracts (Red, Yellow and SilverBook) with a view of addressing the problems identified by many FIDIC users with a view to issuing a new edition in 2010 or2011. See Corbett E, Moment of Decision? The Future of Dispute Boards Under the FIDIC Forms and Beyond (2009) 4Construction Law International 20.

Gerber and Ong

(2011) 27 BCL 414

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

12/26

As identified earlier, the non-binding nature of DRB recommendation plays an important role inthe continuation of negotiation between parties, thereby preserving a consensual and less adversarialspirit. The DAB runs the risk of being perceived as more of an adjudicatory procedure than a disputemanagement system.83

Notwithstanding these shortfalls, the DAB approach is experiencing great success globally, and it

remains a useful on-site tool for avoiding disputes, and resolving those that cannot be avoided. Arecent study conducted by the Dispute Board Federation found that for every 100 DAB projects, 90%of issues are resolved at project level without a formal hearing, and of the 10% disputes referred to theDAB, only 1% of DAB decisions have ever been referred for further arbitral determination.84 Despitethe substantial differences in approaches, the successes experienced by the DAB and the DRB arecomparable, and may suggest that the benefits derived from dispute avoidance procedures have apositive bearing on the dispute resolution process.

Combined dispute board

In 2004, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC)85 published its dispute board rules in an effortto recognise a change in the demand for dispute processes from the business community.86 Thoseresponsible for devising the rules were persons with experience serving as members of both DRBs andDABs.87 As a result, the ICC rules are similar to the FIDIC procedure88 except that they give theparties the option of choosing one of three DAPs, namely: a DRB; a DAB; or a hybrid concept known

as a combined dispute board (CDB).89

The CDB is unique in that for any given dispute, the CDBshall issue a Recommendation unless the Parties agree that it shall render a Decision or it decides todo so upon the request of a Party and in accordance with the Rules. 90 The CDB recognises thepossibility that a party may require a binding decision that can be instantaneously implemented,notwithstanding the ability ultimately to challenge it in arbitration.91 If a party requests a bindingdecision from the CDB, then the decision will be binding on the Parties upon its receipt. 92

The issuance of a decision rather than a recommendation is an exception rather than the norm,and is only to be used where the circumstances warrant such an exception.93 Where controversy existsabout whether the CDB should issue a recommendation or decision, the Rules provide that the choiceultimately rests with the CDB. Guidelines are provided to assist the CDB in determining whether itshould render a binding decision, including whether: due to the urgency of the situation, a decision would facilitate the performance of the contract or

prevent substantial loss or harm to any party;

83 Griffiths D, Do DRBs Trump DABs in Creating More Successful Construction Projects? (2010) 14 Dispute ResolutionBoard Foundation Forum 1.

84 Results are based on a study of 500 global DAB projects conducted by the DBF. Wilson H, President of the Dispute BoardFederation, email to the authors (13 April 2010).

85 The ICC seeks to provide international business with the most efficient tools for resolving any type of commercial dispute.

86 Although DBs are essentially found in the construction and engineering field, the ICC rules have been conceived to be usedin all contractual disputes arising in the course of mid- or long-term contracts and applied not only on engineering contracts, butalso in other fields of business transactions. See Arrocha K, The ICC Dispute Board Rules, Presentation notes prepared for theDRBF 6th Annual International Conference (Budapest, 6-7 May 2006).

87 Koch C, Dispute Boards Under the FIDIC Contracts and the ICC Rules, Paper delivered at the International Chamber ofCommerce and FIDICs International Construction Contracts and Dispute Resolution Conference (Paris, 17-18 October 2005).

88 Koch, n 87.

89 ICC, Dispute Board Rules (2004), Arts 4 and 5, http://www.iccwbo.org/court/dispute_boards/id4352/index.html viewed31 July 2010.

90 ICC, n 89, Art 6; Koch, n 87.

91 For example, a party may require an immediate decision if it is at risk of bankruptcy if it does not receive the claimed paymentimmediately.

92 The parties shall comply with the decision without delay, notwithstanding any expression of dissatisfaction. See ICC, n 89,Art 5.

93 Dorgan CS, The ICCs New Dispute Board Rules (2005) 22 International Construction Law Review 142.

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 15

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

13/26

a decision would prevent disruption of the contract; and

a decision is necessary to preserve evidence.94

Although CDBs have been described as a true innovation in the landscape of Dispute Boards,they have also been referred to as nothing more than an awkward, rather than a useful,

compromise.95

There is certainly the potential for a CDB to increase tensions between the contractingparties through the process of deciding whether to issue a recommendation or decision.96 However,the utility of the CDB is difficult to objectively evaluate, as there is little empirical data availableabout their usage and effectiveness.

Dispute resolution adviser

The DRA, as developed by Colin Wall in Hong Kong in late 1990, is a hybrid system that is said tocombine the best aspects of other DAP models, as well as ADR.97 The DRA evolved from modelsconsidered for use in the United Kingdom, among which included the Independent Intervenor, 98

which employs an impartial mediator or conciliator at the commencement of the project who can becalled upon by the parties if a dispute arises, and issue a prompt binding decision,99 and the DisputeAdvisor100 which modifies the independent intervenor approach, so that the independent third partycan only advise on the means of settling disputes [and] in some circumstances, assist in theirresolution but it is anticipated that his primary duty as an adviser will not undermine the authority of

the Engineer under the contract.101

Although the DRA was based around these British models, the final product sought to providegreater flexibility by combining the dispute prevention attributes of a DRB with partnering102

techniques to re-orient the parties thinking and encourage negotiation through the use of amulti-tiered dispute resolution process.103 Like the DBs, the DRA is jointly chosen and appointed bythe contracting parties at contract commencement, and is encouraged to monitor progress through sitevisits, conferring with the project participants at regular intervals and providing informal advice forthe resolution of potential problems before they mature into disputes.104 The DRA thus sharesvirtually identical procedures and theoretical underpinnings of the DBs when it comes to disputeavoidance, but differs markedly in its dispute resolution approach.

94 ICC, n 89, Art 6.3.

95 Dorgan, n 93 at 142-150.

96 Boucly, n 81.97 Wall CJ, The Dispute Resolution Adviser in the Construction Industry (1993) 21 Building Research & Information 122.

98 Clifford Evans spoke about this concept in 1986 in an address to the Wales Branch of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators andthe South Wales Association of the Institute of Civil Engineers. The concept has since been adopted as contractual adjudication.See Wall CJ, The Genesis, Development and Future use of the Dispute Resolution Adviser System, Paper delivered for theSociety of Construction Law Hong Kong (Hong Kong, 17 November 2004) pp 1-25.

99 Fenn P and Gameson R, Construction: Conflict: Management and Resolution (Chapman and Hall, London 1992) pp 328-329.

100 The concept was introduced in a paper presented by Kenneth Severn in 1989 entitled New Concepts in the Resolution of Disputes in International Construction Contracts, which was the product of ideas from a working party of the CharteredInstitute of Arbitrators, including Clifford Evans. See Wall, n 98, p 5.

101 Fenn and Gameson, n 99, pp 328-329.

102 Partnering is a form of relationship contracting formed by way of a partnership charter which is superimposed on acontractual agreement that theoretically binds the parties to act in the best interests of the project. In essence, the charterrepresents a mission statement for the life of the project and a written commitment to excellence. For example, the goals and

objectives that would probably be identified include the avoidance of disputes and litigation, ensuring no project cost overrunsand that the project will be completed within the contract sum and enhancing mutual trust between the contracting parties. See,generally, Eilenberg IM, Dispute Resolution in Construction Management (UNSW Press, Sydney, 2003) pp 142-156; Jones, n 5at 266.

103 Fenn and Gameson, n 99, pp 328-329.

104 Cheung S and Suen H, A Multi-attribute Utility Model for Dispute Resolution Strategy Selection (2002) 20 ConstructionManagement and Economics 557; Wall, n 98, pp 13-15.

Gerber and Ong

(2011) 27 BCL 416

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

14/26

If initial negotiations fail to resolve a conflict at the job level, then the guidelines for formaldispute resolution include: the DRA recommends what he/she considers to be the most appropriate form of ADR technique,

be that mediation, mini-trial or expert determination;105

if the conflict remains unresolved, the DRA prepares a report summarising, in a neutral manner,

each partys viewpoint and his/her recommendations. The report is designed to assist seniorproject personnel decide on how best to resolve the dispute; and

if disputants are unable to negotiate and reach a settlement, the dispute is referred to short-formarbitration,106 where the DRA helps the parties to choose a technical arbitrator suitable for theparticular dispute.107

Thus, the DRA is a system starting with maximum party control and then introducing a series ofsteps with each one becoming more interventionist and as a last resort, final resolution by way ofshort-form arbitration.108

The DRA was first used by the Hong Kong governments Architectural Services Department onthe 1991 Queen Mary Hospital refurbishment project,109 and its success in avoiding disputes on thatproject prompted the department to develop a policy of using a DRA on all its projects where the costwas over HK$200 million, and if it is a complex project, then the contract value need only be overHK$100 million.110 Like DBs, the DRA has experienced outstanding results. Since its inception in

1991 to the end of 2004, 53 projects have used a DRA, and only one project experienced a dispute thatprogressed as far as requiring short-form arbitration.111 This is compelling evidence that projects thatutilise a DRA are more likely to be completed with few disputes. The Hong Kong governmentrecently committed to the wider adoption of DRAs on public works projects. Ms Carrie Lam, HongKongs Secretary of Development, noted in a 2009 address to the ADR forum:

the construction sector must move with the times, or better still, ahead of the trend. Governmentencourages a wider use of the partnering approach and DRA system in public works contracts, with anaim to encourage the resolution of all differences in opinion before formal disputes arise.112

The success of the DRA system has prompted the inclusion of a DRA on 15 recent contracts(equivalent to 50% of all upcoming major contracts in Hong Kong). Although the DRA has enjoyedgreat success in Hong Kong, it has really not been embraced elsewhere. Colin Wall, founder of theDRA concept, believes there is no reason why it cannot be used on construction jobs outside of HongKong. Indeed, the DRA system was actively promoted for use in construction preceding the 2000

105 Mini-trials are classified as an ADR procedure which resembles a mediation hearing and is explained as a settlement processin which the parties present highly summarised versions of their cases (in a private forum) to a panel of senior executives of bothparties who are often assisted by a neutral chairman. It seeks to convert a legal dispute back into a business problem and aimsto bring the businessmen on each side of the fence directly into the resolution process in the hope that compromises can bereached. Expert determination is based upon the decision of an independent third party. The parties agree to be bound by thedecisions of an independent expert.

See, National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, ADR Terminology: A Discussion Paper, http://www.nadrac.gov.au/www/nadrac/nadrac.nsf/Page/Publications_PublicationsbyDate_NationalADRTerminologyADiscussionPaper viewed 31 July 2010.

106 For a discussion of the key characteristics of short form arbitration, see Wall, n 98, p 17.

107 Wall, n 98, p 6.

108 Gerber, n 1 at 123.

109 Contract required the refurbishment of a then 56-year old general hospital. The added complexities of the contract, whichincluded a requirement to keep the ward hospitals, hospital kitchens, radiology department and operating theatres operationalduring refurbishment, meant that unless an innovative approach to the management and resolution of construction conflict wasadopted, the contract would be beset by disputes: Wall, n 98, p 17.

110 Wall, n 98, p 19.

111Wall C, Do Pre-arbitral Procedures Work, Are They Necessary or Are They Simply Killing Construction Arbitration as WeUsed to Know It?, Paper presented to the Society of Construction Arbitrators Annual Conference (Lisbon, 4-7 May 2007).

112 Lam C, Speech delivered at the Alternative Dispute Resolution Forum (Hong Kong, October 12 October 2009),http://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/200910/12/P200910120167.htm viewed 31 July 2010.

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 17

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

15/26

Sydney Olympics, but was ultimately not adopted.113 Perhaps it is the lack of a dedicated industrybody devoted to promoting the use of the DRA (like the DRBF for DRBs and FIDIC for DABs) thathas stifled the more widespread adoption of this DAP model.

Global impact

DAPs have featured in a variety of projects in the international arena, and are fast becoming arequisite system for both dispute avoidance and resolution. Through to the end of 2006, it is estimatedthat DBs had been planned, or used, in over 2,000 global projects, with a combined construction valueof over US$100 billion.114 New models,115 based on the DB concept, continue to evolve, with thedominant purpose of dispute avoidance first, and dispute resolution only if avoidance is not possible.With this in mind, the balance of this article focuses on Australias limited experiences with DAPs, thereasons behind this slow uptake, and what can be done to change this.

DAPS IN AUSTRALIA: A DISAPPOINTING HISTORY

It appears that the DRB is the only DAP model to have been used in Australia, with the first recordeduse of being in 1987. This was a result of an American contractor, Hatch & Jacobs, promoting it toSydney Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board (MWSDB) for use on the Sydney oceanoutfall tunnels and ocean risers project.116 There were no unresolved issues on any of the contracts atcompletion, but it is not known if there were any formal DRB referrals. However, MWSDB was

obviously impressed with the DRB, and arranged for it to be used on the Warragamba Dam project in1988, which also had no disputes outstanding at completion. Unfortunately, in the 23 years sinceDRBs were introduced into Australia, only 21 projects have used a DRB.

The 21 projects that have used a DRB have achieved the following outcomes: 117

100% success in achieving contract close out by, or very soon after, the date for practicalcompletion;

most projects were completed close to, or ahead of, time and very close to the original contractsum; and

only three disputes were referred to a DRB for a formal hearing and the recommendations fromthose hearings were all accepted by the parties.

These outstanding results reflect the global experience, and thus it is difficult to understand whythere has not been a greater uptake of the concept in Australia. Although there is some evidence of anupward trend in the use of DRBs in Australia,118 one cannot say that DAPs have been embraced bythe Australian construction industry. The following discussion highlights the authors preliminaryfindings regarding the barriers to more widespread use of DAPs in Australia.

Barriers to usage

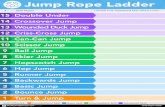

There are four principle barriers to the use of DAPs in Australia, as illustrated in the diagram below.

113 Wall, n 98, p 23.

114 DRBF Manual, n 37 at [1.3].

115 The most recent variant is the Independent Dispute Avoidance Panel (IDAP) which was established in 2008 to help theOlympic Delivery Authority avoid contractual disputes during the work to deliver the venues and infrastructure for the London2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. The IDAP has been charged with the responsibility of finding pragmatic solutions toproblems which may arise before they become disputes that could require lengthy resolution. Given the scale and complexity ofthis project, the IDAP is made up of 10 construction professionals. More interestingly, a dedicated dispute adjudication panel hasalso been established, which is made up of a further 10 members experienced adjudicators and different from the members ofthe IDAP. At the present time, confidentiality agreements restrict further information being provided on the process. See London

Olympics, http://www.london2012.com/press/media-releases/2008/04/independent-panel-set-up-to-smooth-london-2012-construction.php viewed 31 July 2010.

116 Peck GM, Dispute Resolution Takes Hold in Australia and New Zealand (2006) 10 Dispute Resolution Board FoundationForum 1 at 18.

117 Statistics presented by Peck GM at the Dispute Boards: Lessons Learned Seminar (Sydney, 10 April 2010).

118 See The Dispute Resolution Board Australasia (DRBA), List of Australian & New Zealand DRBs , http://www.drba.com.au/images/australiasian%20drbs%2023%2006%2010.pdf viewed 31 July 2010.

Gerber and Ong

(2011) 27 BCL 418

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

16/26

FIGURE 4 Factors impeding the uptake of DAPs in Australia

Lack of familiarity

In a 1998 survey of dispute resolution practitioners in the Australian construction industry, only 28%of those surveyed responded that they had any familiarity with DRBs, while only 8% had any directexperience with the concept.119 At the time of the survey, the DRBF had recorded over 400international DB projects, but only four of these were in Australia, which may explain this lack offamiliarity with the concept. This result can be contrasted with the 80%-90% of respondents who werefamiliar with ADR models such as mediation and expert determination. A lack of familiarity withDRBs leads to parties sticking with the mechanisms that they know and understand, and which arealready being used by the market.

Since the 1998 survey, 17 DRB projects have been used in Australia, and with the establishmentin 2003 of the Dispute Resolution Board Australasia (DRBA), an industry body dedicated topromoting the use of DBs in Australia, one might expect to now see higher levels of familiarity withDRBs, and DAPs more generally, among the Australian construction industry. However, the process isundoubtedly still in its infancy in this country, with only 21 projects having so far used a DRB. Thus,levels of familiarity and understanding of DAPs remain limited.

Absence of clauses relating to DAPs in Australian standard form contracts

Although standard form contracts continue to be heavily amended,120 they invariably form the basedocument for most contracts used in Australian construction projects. Having DAPs provisions instandard form contracts would result in an increase in familiarity with the concept, and potentially alsoan increase in their use. When standard form contracts started to include ADR clauses, the Australianconstruction industrys familiarity with, and understanding of, concepts such as mediation and expertdetermination increased significantly.121 Similarly the inclusion of clauses relating to DABs in FIDICin 1995 saw a consequential increase in the understanding and profile of DAPs globally.

There is no need for Australia to re-invent the wheel when it comes to contract clauses relatingto DAPs, since numerous models are available from other jurisdictions. The authors analyse the

experience of three organisations, from different jurisdictions, which have successfully embeddedDAPs clauses into their standard form contracts.

119 Trainer P, Dispute Avoidance and Resolution in the Australian Construction Industry Part 1 (1998) 17(1) Arbitrator39.

120 Bell, n 20 at 80.

121 Altobelli T, Mediation in the 90s: The Promise of the Past (2000) 3(1) ADR Bulletin 8.

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 19

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

17/26

State Highway Department standard form contracts (California and Florida)

The California Department of Transport (Caltrans) played a critical role in the DRB movement whenit began a trial of DRBs in 1994, offering them on all projects valued at US$2.5 million and over. 122

An extensive process evaluation aimed at assessing their effectiveness was conducted on behalf ofCaltrans in 1996, which revealed many recommendations that were subsequently implemented by

Caltrans, and continue to be considered best practice within the industry.

In 1998, following the success of the trial of DRBs on its projects, Caltrans mandated that DRBsbe used on all contracts which had an engineers estimate greater than US$10 million, and calculatedto have a duration of at least 200 working days.123 Between the introduction of the DRB process onCaltrans projects in 1994 and 2002, 282 disputes were heard by a DRB. Parties accepted 60% of therecommendations issued by the DRB, and most of the remainder were either settled by negotiation, ornot pursued further. Testament to the success of the process is that only four of the 282 disputes(1.4%) remained unresolved post-completion and were submitted to arbitration.124

In 2002, motivated by these successful outcomes, Caltrans seized the opportunity to make DRBsavailable on a greater number of projects, and in addition to mandatory DRBs on projects overUS$10 million, it introduced optional DRBs in contracts with an engineers estimate greater thanUS$5 million and at least 150 working days duration.125 In 2007, Caltrans began mandating the use ofa one-person DRB, called a disputes review advisor, on all projects greater than US$3 million and

less than US$10 million and longer than 100 days duration.126

Like Caltrans, the Florida Department of Transport (FDOT) successfully trialled the use of DRBsin 1994, and now mandate that all contracts valued over US$15 million must use project specificDRBs. Today, having experienced profound success with the concept, FDOT makes DRBs availableon all its projects.127 Between 1994 and 2006, FDOT used DRBs on more than 600 projects valued atover US$10 billion; from these, 220 disputes were referred to a DRB for a formal hearing. All but five(97.7%) were resolved without requiring arbitration or litigation. With such unprecedented success,other notable state highway departments,128 including the Washington Department of Transport andthe Boston Department of Transport, followed suit and embedded DRB provisions in their standardform contracts. It appears that the widespread adoption of the DRB concept by these state highwaydepartments has contributed to the extensive use of DRBs in the United States. Such is the stronginfluence of these state highway departments that of the 810 construction projects that used a DRB inthe United States, and were completed by 30 December 2007, 77% came from these four jurisdictions,that is, California, Florida, Washington and Boston.129

Interestingly, it is a road authority that is at the forefront of DRB usage in Australia. QueenslandMain Roads (QMR) has taken note of the successful use of DRBs by its American counterparts, and

122 The Barrington Consulting Group, Inc, Dispute Review Board Process Evaluation (submitted to Caltrans, 1997) pp 1-89.

123 State of California Department of Transportation, Construction Program Bulletin (2002), http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/construc/cpb/cpb02-3.pdf viewed 3 February 2010.

124 Nichols JW, DRBs Overtake Arbitration in California (2003) 7 Dispute Resolution Board Foundation Forum 1.

125 California Department of Transportation, Construction Manual (2009) Ch 5, http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/construc/manual2001viewed 31 July 2010.

126 DRBF Manual, n 37 at [1.3].

127 Ellis R, Disputes Review Board & Project Disputes, Presentation notes for FICE/FDOT Design Conference (Orlando,30 July 2006); see also Sadler D, FDOT Use of Disputes Review Boards, http://www.construction.transportation.org/Documents/Sadler,FDOTDisputesReviewBoards.pdf viewed 31 July 2010; Florida Department of Transportation, Guideline for Operation

of a Regional Dispute Review Board, http://www.dot.state.fl.us/construction/CONSTADM/DRB/Guideline.shtm viewed 31 July2010; DRBF Manual, n 37 at [2.11].

128 California, Florida, Massachusetts and Washington are the largest users. The highway departments of Idaho, Minnesota,Mississippi, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia and Wisconsin also have active DRBs: see DRBF Manual, n 37 at[1.3].

129 Thirty-five per cent of the projects were in California, 21% in Florida, 15% in Washington, and 6% in Boston. See DRBFDatabase, n 62; Menassa and Mora, n 74 at 65-77.

Gerber and Ong

(2011) 27 BCL 420

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

18/26

since 2006, its design and construct contracts have included a standard option for DRBs. This maytrigger a significant increase in the use of DRBs by the QMR, and in Australia generally. 130 It iscrucial that QMR, perhaps in collaboration with the DRBA, undertakes extensive evaluation, similarto that conducted by Caltrans, in order to appreciate and understand the myriad of outcomes that flowfrom having a DRB on a project. Such results should be widely publicised, so as to increase awareness

of, and familiarity with, the concept in this country.ConsensusDOCs (United States)

ConsensusDOCS is a relatively new suite of American standard form contracts released in 2007. Itprovides the contracting parties with the option of electing to refer disputes to a project neutral/DRBif bona fide negotiations fail to resolve a dispute.131 ConsensusDOCS differs from other Americanstandard form contracts in that it is endorsed by a diverse coalition of 29 leading constructionindustry associations with members from all stakeholders in the design and the constructionindustry.132 Given this expansive involvement of construction industry associations, it has beendescribed as an unprecedented effort the most significant industry development in the last20 years. The diverse buy in amongst all parties will literally transform the industry.133 Byendeavouring to represent the best interests of the project, rather than a single party, ConsensusDOCSseeks to directly address the perception of bias that has plagued standard form contracts, based onwhich organisation is responsible for drafting the contract. The ConsesusDOCS lump sum contractprovides that:

The Project Neutral/Dispute Review Board shall be available to either Party, upon request, throughoutthe course of the Project, and shall make regular visits to the Project so as to maintain an up-to-dateunderstanding of the Project progress and issues and to enable to Project Neutral/Dispute Review Boardto address matters in dispute between the Parties promptly and knowledgeably. The ProjectNeutral/Dispute Review Board shall issue nonbinding findings within five (5) business Days of referralof the matter to the Project Neutral, unless good cause is shown. 134

ConsensusDOCS continues to gain favour in the commercial and industrial markets, with theresult that several owner and contractor organisations, such as the Construction Owners Association ofAmerica and the Associated General Contractors of America, have ceased development of their ownstandard form contracts in favour of promoting the ConsensusDOCS suite of contracts.135 It isanticipated that ConsesusDOCS market penetration will see an even greater use of DRBs in America.

FIDIC (Europe)

FIDIC contracts are one of the most heavily used standard forms for international projects. Given

FIDICs standing in the international community, the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), whichincludes the World Bank,136 require their borrowers and aid recipients to use a modified version ofFIDICs Red Book on any projects they fund.137 The Dispute Board Federation138 has reported thatthe widespread influence of these funding bodies139 has resulted in almost 94% of all DBs in usearound the world being in the form of a DAB pursuant to a FIDIC contract. 140 In fact, the success ofthe DAB in MDB funded projects in China, for example, has prompted the Chinese government to

130 Queensland Main Roads currently have DRBs on three projects valued at AU$540 million.

131 The term project neutral is not defined in ConsensusDocs but appears to be in effect a one-person DRB.

132 ConsensusDOCS, Why ConsensusDOCS, http://www.consensusdocs.com viewed 9 December 2010.

133 Perlberg B, Consensusdocs Built by Consensus for the Projects Best Interest, Paper delivered at the ConstructionSuperconference (San Fransisco, December 2007).

134 See ConsensusDOCS, 200 Standard Agreement (LS) [lump sum], cl 12.3. Also available is ConsensusDOCS, 300 Tri-PartyAgreement for collaborative project delivery; ConsensusDOCS, 410 Design-Build Agreement (GMP) [guaranteed maximum

price].135 Loots and Charrett, n 7, p 39.

136 Other banks include the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction andDevelopment, and the Inter-American Development Bank Group.

137 For example, in 2004, the MDBs, in collaboration with FIDIC, published the Master Bidding Documents for Procurement ofWorks and Uses Guide (known as the Harmonised Conditions of Contract) a modified version of the new Red Book, whichsimplifies the use of the FIDIC contract for the MDBs, their borrowers and others involved with project procurement. See

DAPs: When will Australia jump on board?

(2011) 27 BCL 4 21

-

8/4/2019 DAPs When Will Australia Jump on Board

19/26

recommend the use of DABs to parties entering into construction contracts in its standard documentson construction bidding. Although the procedure is not mandatory, it is strongly endorsed by theChinese government.141

The penetration of FIDIC into other international markets will undoubtedly further promote theDAB concept as a reputable system for dispute avoidance and dispute resolution, and given FIDICs

stature in the international arena, the DAB looks likely to play a prominent role in exposing the worldto DAPs. The Dispute Board Federation has therefore stated that the best way to market the use ofDBs outside America is to promote the use of the FIDIC Red Book.142 Australia, however, standsapart from the rest of the world in not embracing FIDIC as a standard form contract for majorinfrastructure projects. The explanation for this is not entirely clear, but may be due to the plethora ofAustralian standard form contracts with which the construction industry is familiar and comfort-able.143

Commitment to relationship contracting

The third possible explanation for the limited uptake of DAPs in Australia might be the countrysfocus on a different system of managing conflicts and disputes, namely relationship contracting.Australias love affair with partnering and alliancing may have diverted attention away from DAPs.144

In stark contrast to the 21 projects that have used a DRB in Australia, there have been over 340projects that have used some form of relationship contracting.145 Relationship contracting has been

defined as:a process to establish and manage the relationships between the parties that aims to: remove barriers;encourage maximum contribution; and allow all parties to achieve success [It] requires the parties tobecome result focused and willing to challenge conventional standards. The focus is on a cooperativeendeavour to improve project outcomes rather than establishing a legal regime to penalisenon-conformance.146

Unlike DAPs, relationship contracting diverts the attention away from conflicts and disputes, andinstead focuses on fostering collaborative working relationships with the inferred belief that this willlead to successful project outcomes. The two approaches are markedly different in that DAPs involvethird parties (DB members) to assist with the avoidance and resolution of disputes, whereasrelationship contracting endeavours to internalise all issues, and requires the contracting parties to