crJhapte'C 6 - Shodhgangashodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/29029/13/13_chapter 6.p… ·...

Transcript of crJhapte'C 6 - Shodhgangashodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/29029/13/13_chapter 6.p… ·...

crJhapte'C 6 eJnte'C-8lle~ionat ~naty8e8

=-

Development planning in Bangladesh can be characterized as a centralized

system of planning divorced from people participation. The approach to planning has

been interventions largely as an exercise in delivering resources to the poor by the

trickle-down route or through the contemporary approach of targeted development.

The policy regime of the last two decades has reinforced these iniquitous structures

and re legitimized them by elevating the values of individual accumulation into a

dominant value. This has resulted in unequal distribution of resources to the different

regions of Bangladesh leading to lop sided development in the country. Severe

deterioration in terms of trade and uncertainty in international aid environment

seriously affected Bangladesh's growth prospects in the early eighties. The

government, therefore, undertook a programme for macro-economic stabilization and

adjustment within the World Bank policy framework. During the last one decade the

Bangladeshi economy has achieved a modest and reasonably steady annual rate of

growth of GDP of 4-5 percent. Though there has been some reduction in incidence of

poverty, this growth rate has failed to bring about even development-both ecor.omic

and social within various divisions in Bangladesh

The failure of successive generations of development policy to eradicate

poverty and build a more inclusive development process originates in the incapacity

of the policy discourse to come to terms with the new realities of power, which have

sharply polarised the society in Bangladesh. Dissatisfaction with this approach has

gradually built up in Bangladesh, associated with a general disillusionment with

purely growth-oriented development strategies, which had resulted in neglect of the

social sectors and appears to have done little to reduce poverty levels in the country.

The mid-1980s in Bangladesh saw considerable ferment of ideas about human

resources development, focused especially in the Asian and Pacific region,

culminating in the emergence of a new perspective, most clearly expressed in the

Jakarta Plan of Action on Human Resources Development in the ESCAP Region

developed by ESCAP and adopted by the Governments of the countries of the region

at Jakarta in 1988. The Plan focused on the central role of human beings as the key

factor in the development process; called for balanced and integrated treatment of the

163

supply and demand factors in relation to human resources development; and

emphasized participation in economic activity, particularly employment. I

"Not only are .. .investments in human capital a vital source of increased

production, but the most important human capital investments, in health and

education, are simultaneously highly valued items of consumption in developing

countries and among the most important determinants of the quality of life. Thus, the

characteristics that, from a consumption perspective, reflect the individual's quality of

life constitute the quality of the individual's human capital from a production

perspective ... 2

Thus there has been a decisive shift in the development priorities of

investment from physical infi'a!;tructure to human resource development and poverty

reduction by raising significantly the share of public investment in education, health,

sanitation and family welfare. Donor agencies like the World Bank etc. have played

an important part helping the government in its commitment to social sectors. In order

to understand Bangladesh's socio-economic achievements and failures it is important

to examine the quality of life, fertility trends, migration levels and employment scene

of the various divisions in Bangladesh in detail.

6.1 Demographic Data by Division

Bangladesh is divided into six mam regions. They are Barisal, Dhaka,

Chittagong, Rajshahi and Khulna and the recently formed division Sylhet which was

earlier a part of Chittagong. The cultural background of the native people and their

geographical situation determines these regions. Dhaka region is in the central part of

the country and homes Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh. Chittagong region is

situated in the southeast region and includes the most important port and the second

largest city named Chittagong. The Rajshahi district is in the northwest part of the

country and is influenced mainly by the Indian culture. Khulna, the smallest of the

main regions, lies in the southern part of the country containing many islands in the

Bay of Bengal and the Sunderban rain forest.

2

ESCAP, Guidelines 10 an Integrated Approach to Human Resources Development Policy-Making, Planning and Programming, STIESCAP/997 (Thailand: 1991), p.l.

Lorraine Comer, Human Resources Development: The Theoretical Issues, Paper presented at Development Studies Conference on Mechanisms of Socio-economic Change in Rural Areas, (Australian National University: November 1991). p. 8.

164

Table 6.1 shows the divisional population of Bangladesh for the years 1991

and 1996. We find that there has been an increase in the urban population in all the

divisions. The urban population has increased by 18.9 percent for Dhaka, 16.78

percent for Rajshahi, 17.6 percent for Khulna and Barisal and 10.6 percent for

Chittagong The growth in the rural population has been slower in all the divisions

during the period 1991-1996. (Table 6.1)

Table 6.1 Population of Bangladesh by Division (in '000')

Divisions Rural Urban Rural Urban Percent Percent Change Change Rural Urban

1991 1996 1991-96 1991-96

Barisal 6756 1001 7265 1177 7.53 17.5

Chittagong 17108 4757 18628 5265 8.88 10.67

Sylhet 6394 756 6900 919 7.9 21.5

Dhaka 24320 9621 26321 11446 8.22 18.9

Khulna 10728 2515 11561 2958 7.76 17.6

Rajshahi 23694 3806 25677 4445 8.36 16.78

Source: National Data Bank, Bangladesh Data Sheet, 1997, (Dhaka: Statistics Division-Ministry of Planning, May 1998)

The sex ratio is usually expressed as the number of males for every 100

females. As we have discussed in Chapter three the sex ratio in Bangladesh is adverse

to women. It is observed that the sex ratio in all the divisions in Bangladesh is higher

in the urban areas as compared to the rural areas. There are more men than women in

the population of Bangladesh as can be seen from Table 6.2.

Table 6.2 Sex-Ratio by Administrative Divisions and Locality, 1974-1991

Divisions 1974 1981 1991

Tota. Urban Rural Total Urban Rural Total Urban

Bangladesh 107.7 129.4 105.9 106.4 125.8 103.3 106.1 118.1

Barisal 105.4 123.8 104.7 104.6 119.7 102.8 103.5 111.8

Chittagong 108.8 142.8 106.4 105.7 130.5 101.9 105.3 122.0

Dhaka 109.3 130.7 106.3 108.3 129.9 103.4 108.3 121.5

Khulna 107.2 125.8 105.4 107.1 120.6 104.7 106.2 113.7

Rajshahi 105.6 112.0 105.5 105.2 114.1 104.2 105.5 109.1

Source: Government of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Analytical Report of Population Census J99J-Volumtl J, (Dhaka: Statistics Division-Ministry of Planning, May 1994),

165

Rural

103.4

102.3

101.9

103.5

104.6

104.4

From table 6.2 it is foun~ that, Dhaka Division has the highest sex ratio in 1974 and

Barisal Division has the lowest sex ratio at total level for the last three censuses. In

urban area. however, Chittagong Division has the highest sex ratio, followed by

Dhaka. The very high sex ratio of urban population of Chittagong Division may be

explained by the fact that Chittagong is an industrial area. Commercial and industrial

enterprises, and Chittagong port are located in this division. This in tum has resulted

in a higher concentration of male population in this area due to internal migration. For

similar reasons in urban areas of Dhaka and Khulna divisions have higher sex ratio

than that of Barisal and Rajshahi. A high sex ratio indicates higher mortality for

females than for males. However, a fraction of the imbalance can be attributed to the

omission of females in census enumeration in Bangladesh like in all other South

Asian countries.

Table 6.3 Sex-Ratio by Administrative Divisions and Locality, Percentage ell 19811991 ange -

Divisions Percentage Change 1981-1991

Total Urban Rural

Bangladesh -0.28 -6.12 0.09

Barisal -1.05 -6.59 -0.48

Chittagong -0.37 -6.51 0

Dhaka 0 -6.46 0.09

Khulna -0.84 -5.72 -0.09

Rajshahi 0.28 -4.38 0.19

Source: The figures have been computed using the data from table 6.2

The percentage change in the sex ratio for the period 1981-1991 as shown in

table 6.3 shows an improvement in the sex ratio in urban areas in all the divisions. But

the percentage change in the sex ration for rural areas shows hardly any change for all

the divisions. This implies that though the sex ratio has shown an improvement during

the period 1981-1991 it still continues to be adverse to females especially in rural

areas in Bangladesh. The decline in sex ratio in the 1991 census may be attributed to

better coverage of women in the 1991 census, as well as to a decline in female

mortality.

166

1Jte percentage distribution of population by religious communities and by

.' administrative divisions is presented in Table 6.4. It is found that Dhaka division has

recorded the highest proportion of Muslim population during 1981 and 1991 censuses.

But in 1951 census Barisal division recorded the highest share of Muslim population,

which has been closely followed by Rajshahi division.] It is seen that, in the 1981, and

1991 censuses, the proportion of Hindus, Christians and Buddhists are seen to be the

highest in the divisions ofKhulna, Dhaka and Chittagong respectively.

Table 6.4 Division Wise Distribution of Bangladesh Population by Religious Communities 1981 and 1991

Division Percentage

1981 Muslim Hindu Buddhist Christians Others

Barisal 86.16 13.50 0.06 0.24 0.04

Chittagong 85.65 11.64 2.32 0.18 0.21

Dhaka 89.60 9.74 0.02 0.46 0.10

Khulna 80.05 19.42 0.01 0.44 0.08

Rajshahi 87.42 11.54 0.02 0.24 0.78

1991

Barisal 88.10 11.60 0.06 0.20 0.03

Chittagong 86.90 10.55 2.11 0.20 0.16

Dhaka 91.19 8.13 0.06 0.47 0.15

Khulna 83.61 16.00 0.02 0.30 0.07

Rajshahi 88.42 10.49 0.00 0.32 0.69

Source: Government Of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Analytical Report of Population Census 199/-Volume I, (Dhaka: Statistics Division-Ministry of Planning, May 1994)

6.2 Quality of life

Quality of life can be best described by a single parameter called the Human

Development Index (HOI). HDI comprises of. three components: life expectancy,

representing health status; educational attainment, representing knowledge; and real

GDP in term,s of purchasing power parity in US Dollars, representing the standard of

living. Bangladesh can be seen as lagging in the quality of life.

3 Government Of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Analytical Report of Population Census J 99 J-Volume I, (Dhaka: Statistics Division-Ministry of Planning, May 1994), pp. 104-105.

167

6.2.1 Human Development by Division

Compared with the other countries classified as having 'low human

development' (rankings between 131 and 175)4 Bangladesh's index was 10 percent

lower than average. This was largely due to poor scores for adult literacy. The 1997

global HDR, using 1994 data, estimated Bangladesh's HOI to be 0.36. s

Table 6.5 shows that three divisions are above the national average (by the

1997 HDR report data) while two are below. In descending order they are: Barisal,

0.420; Chittagong, 0.411; Khulna, 0.408; Dhaka, 0.386; and Rajshahi, 0.352. (Table

6.5) Of course the divisions themselves are also very heterogeneous in terms of

human development so they are not perhaps the best units to consider. Nevertheless

they provide some indications that might be used for broad-based targeting. From the

table one can see that Rajshahi is the state, which lags behinds in terms of almost all

human development indicators and also has the lowest HOI among all divisions. It is

not possible to compare the HDI indices over a period of time, as the data is not

available. Divisional data show considerable variability in adult literacy, and real

GOP per capita. As for other indicators such as life expectancy and infant mortality

the variability is much lower. This suggests that there is a greater need for developing

a spatial focus in designing policies when it comes to tackling the issues of primary

education, primary health and income-poverty reduction.

Table 6.5 Division Specific Human Development Indicators, 1994-95

Indieaton Barisal Chitta£on£ Dhaka Khulna

Life Expectancy at Birth (LE)

57.2 57.0 58.3 58.4

Adult Literacy 56.4 41.2 43 47.2

Combined Enrolment Ratio (CER)

41.20 37.38 37.90 44.11

Real GOP per capita (PPP$)

1431.57 2017.44 1320.50 1413.09

Human Development Index (HOI)

0.420 0.411 0.386 0.408

Source: UNDP, Bangladesh Human Development Report 1997, (UNDP, 1997).

UNDP, Human Development Report J997, (Oxford: 1998), p, 177.

ibid.

168

Rajshahi

56.5

35.2

38.82

1166.66

0.352

Bangladesh is facing a tremendous pressure on it~· resources to cater to

ecucation to new admission - seekers in primary education. Every year an

approximate number of 3.12 million 4 years old children are becoming 5 years old

and 3.53 million 5 years old children are becomIng 6 years 01d.6 Considering

education as a whole - primary, secondary and higher - the benefits are being reaped

disproportionately by the better-off hcuseholds. The bottom 20 percent of households

have access to only 14 percent of public spending on rural education while the top 20

percent get 29 percent. 7 A similar disparity emerges if the spending is allocated

between the 'poor' (about 52 percent of households in 1994) and the 'non-poor,.8 This

overall disparity is' largely because the wealthier families take more advantage of

secondary and higher education. Thu') while the bottom 20 percent receive only 6

percent of the benefits from secondary education the top 20 percent receive 35

percent.9

The government (and the private sector) in Bangladesh have cr~atedlprovided

facilities for education including schools, reading materials, recruitment and training

of teachers. However, the number of school teaching children has grown at such a fast

pace that the government facilities in the field of education are proving to be short

than the demand. As a result the NGOs have come to play an important part in

providing education to the people of Bangladesh especially to the rural and urban

poor (in the form of non-formal education) who cannot afford to go to the school for

various reasons.

Let us start by examining data on NGOs providing primary education for the

various divisions in Bangladesh. There are many NGOs offering Non-Formal Primary

Education (NFPE) in Bangladesh in all the divisions. Table 6.6 presents the division

wise nu~ber of NGOs offering NFPE Programmes, number of learning centres,

enrollment, and number of Teachers in Non-Formal Primary (NFP) Schools for the

year 1995. As can be seen from the table 6.6, in the year 1995 a total of 31 percent

(306) NGOs are involved in NFPE programme at the national level and a great

6

7

• 9

Government of Bangladesh, Education For All: The Year 2000 Assessment Bangladesh Country Report (Dhaka: Primary and Mass Education Division, 2000).

UNDP, Bangladesh Human Development Report /997, (Oxford: 1997), pp. 22-23 .

ibid.

ibid.

169

majority of learning centres (93 percent) and enrollment (92 percent) are located in

Dhaka Division.

There were 38,288 NFPE (table 6.6) schools at the national level in 1995 with

an enrollment of 1,342,362 of whom 63 percent are girls. The enrollment rate of girls

in primary schools for Bangladesh in 1995 was 47 percent quite below the enrollment

rate of girls in NFP schools in 1995. At the national level, number of teachers in the

NFP schools in 1995 stood at 40,347, per centre average teacher being 1.05. (Table

6.6) In all the divisions the enrolment of girls is much more than boys.

Table 6.6 Division-wise number of NGOs Offering NFPE Programmes, Number of Leaming Centres, Enrollment, and Number of Teachers in

F S I' BId 99 N P choo s ID angla esh.l 5 No.orNGOs No. or

Offering Non- NFPE Enrollment Teachers Location rormal Primary Centres

Education Pro2rammes

Male Female Total Total National Total 306 38288 493377 848985 1342362 40341

Urban 116 35846 452601 191895 1244496 37741 Rural 130 2442 40176 57090 97866 2606

Dhaka Total 118 35656 444160 189293 1228453 31226 (38.56%) (93.13%) (91.S I %)

Chittagong Total 19 420 4081 6028 10115 359 (6.21%' (1.1%) (0.15%

Rajshahl Total 75 1031 180.27 23929 41956 1239 (24.51%) (2.69"10) (3.13%)

Khulna Total 51 623 10519 14555 25134 651 (16.67%) (1.63%) (1.81%)

Barisal Total 33 311 4753 6576 11329 324 (10.78%) (0.81) (0.84%)

Sylhet Total 10 241 11171 13604 25375 548 (3.27%) (0.65%) ( 1.89"10)

Source: Government of BangJadesh, Education For All: The Year 2000 Assessment Bangladesh Country Report (Primary and Mass Education Division, Dhaka, 2000)

Note: Figures in the parenthesis show the division-wise percentage distribution ofNGOs, NFPE centres and enrollment.

On the whole, Dhaka Division has the highest concentration (table 6.6) of

NGOs (38.5 percent) while Sylhet Division has the lowest concentration (3.7 percent).

On an average, number of basic education centres per NGO in 1995 was 992 in Sylhet

Division followed by Chittagong Division (600 per NGO), Rajshahi Division had 489

centres per NGO, while Dhaka Division had the lowest position with 172 centres per

NGO. 10 Looking at enrolment in non-formal basic education centers in 1995 we find

10 Government of Bangladesh, Education For All: The Year 2000 Assessment Bangladesh Country Report (Dhaka: Primary and Mass Education Division, 2000).

170

that Dhaka Division had the highest concentration of enrollment (33.87percent)

followed by Rajshahi Division (23.81 percent) and Chittagong Division'

(20.31 percent), Barisal Division had the lowest enrollment concentration

(3 .65percent). II

We can see from table 6.7 that the girls attending school in all the divisions in

Bangladesh are far below the rate for boys at all levels of education. The need to

eliminate these disparities will require not only additions to existing educational

facilities and services, but also in some societies, the provision of new facilities and'

services exclusively for females. The large school attendance at the primary level

(Table 6.7) is assigned to the high priority accorded by the Bangladesh government to

achieving universal primary education by specified dates and have, over the years,

made significant strides in providing increased acceSs to primary education.

Consequently, despite the high population growth in Bangladesh during the

past two decades or more and the resultant concentration of population in the lower

age brackets, the gross enrolment ratios at the primary or first level have recorded

significant increases, though all those who enrolled did not complete the final grade.

A measure of this success can be accorded to the role NGOs have played in providing

non-formal primary education. (as has been discussed earlier section of the chapter)

Table 6.7 Percent of Population Ages 5-24 Years Attending School in each D' " bAd S 1991 IVISlOn ,y ~ge an ex,

Divisions 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female

Bangladesh 42.3 39.6 56.0 52.3 35.8 20.7 16.6 4.1

Barisal 44.5 44.2 60.2 58.0 39.5 22.2 18.8 4.2

Chittagong 45.4 42.4 58.9 53.1 36.8 21.4 16.5 3.6

Dhaka 41.0 38.1 55.5 52.7 36.2 23.9 17.9 5.4

Khulna 45.1 42.8 57.6 55.1 35.9 19.1 15.0 3.6

Rajshahi 38.9 35.7 51.0 47.3 33.1 16.4 15.2 3.0

Source: Government of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Analytical Report of Population Census 1991-Volume I, (Dhaka: Statistics Division-Ministry of Planning, May 1994).

II ibid.

171

One can obser,ve from table 6.7 that the school attendance goes on to decrease

sharply after the ages 10-14 for all the divisions implying that the drop out ratio is

high as the level of education increases. The ratio of drop out is higher among females

as compared to males because of reasons of early marriage, economic burden of

educating a girl and burden of household work. Nothing much can be said about the

quality of education as enrolment rates are a poor index of the quality of education . .

because they reveal neither what is being learned by the pupils who occupy the school

benches nor what proportion of pupils are irregular in attendance or leave the system

before achieving even basic literacy.

Table 6.8 Crude Birth Rate (CBR) By Division in Bangladesh, 1982, 1991 .-

Division 1982 1991 Percent Ch&nge in CBR 1982-1991

Barisal 33.6 28.0 -16.6

Chittagong 35.1 32.4 -7.69

Dhaka 34.6 30.8 -10.98

Khulna 33.7 30.5 -9.5

Rajshahi 33.9 33.2 -2.06

Source: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Demographic Report of Bangladesh-199l, Volume 4, Ministry of Planning (Dhaka: 1997)

Government involvement in the public health care is also particularly

important for the rural poor. When public health-care facilities are inadequate the rich

can turn to private clinics and doctors. But the rural poor have to use either the public

services or traditional or other untrained practitioners.

A look at the figures for CBR (Table 6.8), one can see that the CBR for all

divisions have gone down for all divisions in Bangladesh. The percenw.ge change in

CBR (table 6.8) during the period 1982-1991 shows that CBR fell by 16.6 percent for

Barisal, 10.98 percent for Dhaka, 9.5 percent for Khulna, 7.69 percent for Chittagong

and the lowest for Rajshahi (2.06 percent). Chittagong has the highest CBR in 1982

and occupies the second position in tenus of CBR among the various divisions in

172

1991. A fall in the CBR reflects not only increased use of contraceptives in the

country but also increase in the level of education among women in all the divisions.

Table 6.9 Crude Death Rate by Division in Bangladesh, 1991

Administrative Total Rural Urban Divisions B. Male Female B. Male Female B. Male

Sex Sex Sex

Barisal 9.0 9.4 9.1 9.7 9.9 9.6 7.2 7.3

Chittagong 10.2 11.3 9.7 10.5 10.6 9.9 7.5 7.7

Dhaka 9.1 9.0 9.2 9.5 9.4 9.6 7.0 7.1

Khulna 10.0 10.2 9.9 10.3 10.5 10.2 7.3 7.0

Raj shah i 9.0 9.7 8.8 10.2 9.9 9.2 7.2 7.3 .. Source: Bangladesh Bureau of StatistiCS, DemographIc Report oJBangladesh-J99J, Volume 4, Ministry of

Planning (Dhaka: December 1997).

Female

7.0

7.2

7.9

7.5

7.9

CDR figures as shown in table 6.9 shows that the CDR in 1991 for Chittagong

is highest among all divisions for both rural and urban areas and among women and

men. This trend is similar to the trend in CBR as we discussed before. This indicates

the problem of the isolation of the communities spread out in small settlements and

lack of coordination in utilizing of the local resources. While the Chittagong area

fares better economically than some of the other areas of the country, its development

in the social sector, especially health and sanitation, fails to measure up compared to

the resources available. 12 The reduction in CDR indicates the improved access to

health services and increased awareness about preventive and curative health care

among all the divisions.

6.2.2 Food for Education Programme

Understanding that poverty of parents is major factor for low enrollment in

school and high drop-out rates the government of Bangladesh introduced the Food

For Education Programme (FFEP) in all the divisions with a built-in strategy to attract

the poverty-stricken families to send their children to school, instead of engaging

them for earning a livelihood. The food given under the programme becomes the

income entitlement to poor families and this enables them to release their children

12 UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Reports Submilled by States Parties under Article 9 oJthe Convention, Bangladesh, CERD/C/379/Add.I, (New York: 30 May 2000), p.9.

173

from livelihood obligations as well as to send the c~ildren to primary schools and

retain them therein.

The main objectives ofFFEP are:

• to increase enrollm~nt rate,

• to increase attendance rate,

• to reduce dropout rate in order to ensure retention in, and completion of

primary schooling; and

• to improve the quality of education.

The programme covered 1,243 selected unions of 460 Thanas of Bangladesh.

Under this programme, one child from each eligible family is given 15 kg of wheat or

12 kg of rice and! or more than one child 20 kg of wheat or 16 kg of rice every month.

At present 2.2 million families covered under 17,203 primary level school in 1,243

unions are being benefited and the number of students benefited is 2.28 millions. 13 Of

the enrolled students a maximum of 40 percent poor student are ,::ntitle to receive food

grains.

It has been found from an evaluation that the FFEP has attracted children of poor

parents to a large extent. For example, gross enrollment under Food for Education

Programme has been quite a success as from the following data:

Table 6.10 Gross Enrolment under Food For Work Programme in Bangladesh

Division 1993 1995 1998 Both Female Both Female Both sexes Female sexes sexes

Bangladesh 405,797 191,370 481,204 235,027 533,469 268,632

Dhaka 116.780 56,400 139,205 67,708 153,673 77,492

Chittagong 89,934 39,020 106.523 49,908 121,961 59,163

Sylhet 36,892 19,236 41,837 21,822 45,520 23,900

Rajshahi 92,581 41,215 110,007 52,818 125.019 62,886

Khulna 17,422 23,443 55,562 28.185 56,599 28,685

Barisal 22,370 12,056 27,170 14,496 30,694 16,506

Source: Government of Bangladesh, Education For All: The Year 2000 Assessment Bangladesh Country Report (Dhaka: Primary and Mass Education Division, 2000)

13 Government of Bangladesh, Education For All: The Year 2000 Assessment Bangladesh Country Report (Dhaka: Primary and Mass Education Division, 2000).

174

The evaluation found qu.antitative impacts on enrollment, attendance, dropout and

repetition as follows: 14

• The enrollment in the programme schools increased from 405,797 in 1993 to

481, 200 (119percent) in 1995 and to 533,500 (131percent) in 1998, while in

non-programme schools the enrollments of surveyed schools were 86,000 in

1993, which increased to 101,000 (l17percent) in 1005 and 97,000

(l13percent) in 1998. (Table 6.10)

• The attendance rates of the students of the programme schools increased

consistently and sharply from 71.1 percent in 1993 to 77.7 percent in 1995 and

further to 81.8 percent in 1998. While these rates of those of non-programme

schools were low, though slowly rising from 66.4 percent in 1993, 69.5

percent in 1995 and 71.7 percent in 1998. The rate of' attendance of'

interviewed students was found at 90.8 percent in1998.

• The dropout rates of the students of' programme schools were a little above 1

percent with a declining tendency, while those rates for non-programme

schools were found around 6 percent.

• The repetition rates for the programme schools were around 1 percent, while

those for the non-programme schools were a little below 5 percent

The evaluation of qualitative impacts on learner's attitude learning and attendance

was as follows: IS

• Ninety two percent of the Head Teachers and 99 percent of the students of the

progran'Une schools interviewed and 94 percent of the Chairman!Members of

SMC asserted that the learner's willingness to learn increased because of

FFEP.

• Ninety seven percent of the Head Teachers, 99 percent of the students and 98

percent of the Chairman!Members of SMC expressed that the habit of

attendance of beneficiary students increased,

14 ibid.

15 ibid.

175

• Ninety four percent of the Head Teachers, 95 percent of the Guardians, 97

percent Chairman/Members of SMC and 92 percent of the Union (Chairmen!

members said that because of FFEP incidence of child labour declined.

• Out of 1284 students 71(5.5percent) have responded that they would dropout

if FFEP is discontinued.

The programme has demonstrated that if the factors, which are responsible for

low enrollment, are met parents can be motivated to send their children to school.

6.3 Fertility Regulation by Division

Current use of contraception is defined as the proportion of women or men

who reported they were using a family planning method at the time of the interview.

Differentials in current use of family planning by divisions of the country are large.

Table 6.11 presents the proportion of women currently using any contraceptive

methods by division in Bangladesh. In 1996-97 sixty two percent of married women

in Khulna division and 59 percent in Rajshahi division are using a family planning

method compared to only 21 percent of women in Sylhet division. Intermediate level

of use was reported for women in Dhaka (51 percent), Barisal (50 percent), and

Chittagong (39 percent) in the year 1996-1997 (Table 6.11). There are no remarkable

variations in relative popularity of methods by division, except that injectables are

more widely used in Khulna and Barisal than elsewhere. In all divisions, the use of

modem methods accounts for at least 80 percent of all use. 16

Table 6.11 Proportion of Women Currently Using any Contraceptive Methods, Bid h 1993 1994 d 1996 1997 b D' .. anea es : - an - )V IVlslon

Division Ban21adesh Demo2raphic and Health Survev (ODHS) Percent Change Proportion of Women Proportion of Women 1993-94-1996-97

1993-94 1996-97 Barisal 48.3 50.4 4.34

Chittagong 30.2 39.0 29.1

Dhaka 44.9 50.8 13.1

Khulna 55.6 62.7 12.76

Rajshahi 55.3 59.5 7.59

Sylhet - 21.3 -Source: S. N. Mitra. M AI-Sabir and Anne R. Cross, Demographic and Health Survey /996-/997.

(Dhaka: NIPORT, November 1997)

16 S. N. Mitra, M. AI-Sabir and Anne R Cross, Demographic and Health Survey /996-/997, (Dhaka: NIPORT, November 1997), chapter 4, p.24 ..

176

Compared to the figures in 1993-94 there has been a rapid increase in

contraceptive use among women in Chittagong, Dhaka and Khulna. Barisal and

Rajshahi are the two divisions where the increase in contraceptive use among women

has not been substantial. In Chittagong the contraceptive use increased by 29.1

percent, (has been calculated from table 6.11) while the increase was 13.1 percent for

Dhaka and 12.76 percent for Khulna, 7.59 percent for Rajshahi and 4.34 percent for

Barisal. We however cannot make a comparison for Sylhet, as it is a new division

created form the former Chitta gong division. The creation of Sylhet division, isolates

the sections of the former Chittagong division that have the lowest contraceptive use

levels, results in wider divisional differences than existed previously.

As we have discussed in the chapter earlier, the regional pattern of fertility

level in Bangladesh varies. Table 6.12 shows that TFR level in Chittagong division

has, in the years 1984-88 and 1991, been higher than in other divisions of Bangladesh.

Table 6.11 shows that CPR level in Chittagong division has, in the years 1993-1997,

been noticeably lower than in other divisions, although in terms of contextual socio

economic conditions, Chittagong appears to demonstrate a favourable environment

(higher literacy, higher income, high urbanization) for attaining a higher level of CPR

and lower level of TFR. The percentage change in TFR for the period 1984/85-1991

shows that the fall in TFR over the period has been greatest for Chittagong-23 percent

followed by Dhaka-17. 7 percent. (Table 6.12) The fall in the TFR for the period

1984/85-1991 has been very low in Khulna (3.15 percent) and Rajshahi (2.16

percent).

Table 6.12 TFR by division in Bangladesh, 1984-88 and 1991

Division TFR 1984-88 TFR 1991 Percent Change

1984-85-1991

Chittagong S.2 4.0 -23.07

Dhaka 4.4 3.62 -17.7

Khulna 3.8 3.68 -3.IS

Rajshahi 3.7 3.62 -2.16

Source: J. Cleland, Fertility Trends and Differentials in Bangladesh Fertility Survey-1989 Secondary Analysis, (Dhaka: NIPORT, 1993) and Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Demographic Report of Bangladesh-I 991, Volume 4, (Dhaka: Ministry of Planning, December 1997).

177

This deviant CPR pattern in Chittagong suggests the possibility of socio

cultural nonns; the conservative approach of women in Chittagong division has been

an issue, which has remained unaddressed in the family planning programme of

Bangladesh. From table 6.13 we get a picture of urunet need for any family planning

method by divi~ion in Bangladesh. The term unmet need is defined as the percentage

of currently married women in their reproductive ages who do not want additional

children and yet are not practicing contraception. 17 Here we find that the unmt:t need

for family planning is the largest in Chittagong division both in 1993-94 and 1996-97.

The other divisions on the other hand have registered a sharp fall in the unmet need

for any kind of family planning method. Unmet need for contraception was lowest

among women in Rajshahi and Khulna div~sions in surveys in 1993-94 and in 1996-

97. (Table 6.13)

Table 6.13 Percentage of Currently Married Women of Childbearing Age with Unmet Need for any Family Planning method by

Division 1993 94 and 1996 97 't - -Division Percentage of Total Percentage of Total

Number Number 1993-94 1996-97

Barisal 20.1 16.7

Chittagong 27.7 20.7

Dhaka 16.8 15.3

Khulna 15.6 12.1

Rajshahi 14.0 11.5

Sylhet - 22.5

Source: S. N. Mitra, M. Al-Sabir, and Anne R. Cross, Demographic and Health Survey 1996-1997. (Dhaka: NIPORT, November 1997)

A study by Islam and Rafiquzzamanl8, in 1995 identified the following reasons

for a low CPR in the Chittagong Division on the basis of the 1991 Contraceptive

Prevalence Survey (CPS):

17 C. F. WestofT, "The Unmet Need for Birth Control in Five Asian Countries ", Family Planning Perspectives. Volume 10, No.3, 1978: 173-181.

.1 A. Islam and M. Rafiquzzaman, Achievement and Challenges of the Family Planning Programme in the Chiltagong Division, Paper presented at the Regional Seminar on Bangladesh's Family Planning Programme: Achie"ement and Challenges, Organised by PDEU, Ministry of Planning, Chittagong, March 30, 1995.

178

• The field worker visit is very low (less than one fourth of the currently married

women of ~e childbearing age reported at least one visit during the last six

months prior to the date of the survey.

• The currently married women of the childbearing age who were visited by the

field worker reported mostly discussion on pills (81.6 percent) but discussions

on other methods were neglected.

• The problem in mobility of women and field workers 10 the Chittagong

division due to hilly and riverine areas.

All the above-mentioned problems, which were overlooked in the past, can be

resolved to a great extent through a planned action programme by the government

A crucial element of the family planning programme in Bangladesh has been its

system of Family Welfare Assistants (FW A) supported by the government and non

governmental organizations who visit the couples at home to provide contraceptiVf~

information, supplies and referrals. The 1996-97 Demographic and Health survey

finds that field worker visitation varies significantly by division. Only 20 percent of

women in Sylhet division and fewer than 30 percent of women in Chittagong division

reported to have been visited by a field worker, compared to around 34-36 percent of

women in Dhaka and Barisal and 42-45 percent of those in Khulna and Rajshahi

divisions. 19DifTerences in exposure to media as a means to family planning messages

by division are not large, except for Sylhet, where both men and women have less

exposure to family planning than their counterparts in other divisions. Thus one can

say that the low presence ofFWA's in division like Sylhet and Chittagong explain the

low use of contraceptives to some extent.

Other reason, which affects contraceptive use among women, is the socio

economic development of the region. Several studies20 have argued that the

development of communication and transportation systems facilitates rapid fertility

19

20

S. N. Mitra. M Al-Sabir and Anne R. Cross, Demographic and Health Survey 1996-1997, (Dhaka: NIPORT, November 1997), chapter 4, p. 35.

Ronald Freedman, Issues in the Comparative Analysis of World Fertility Survey Data, Papers of the East-West Population Institute No. 62, (Honolulu: East-West Center, 1979) and John, B. Casterline, "Community effects on fertility", in: John B. Casterline (ed.), The Collection and Analysis of Community Data, (Voorburg, Netherlands: International Statistical Institute, 1985),pp. 65-75.

179

decline by assisting the difl\lsion of new ideas and values about family and

reproductive behaviour. It haS been said in these studies that the greater is the value of

commercial centrality and the degree of village electrification, the greater is the

likelihood of the respondents practising contraception or intending to do so. The

greater is the distance {)f the thana from district headquarters, the lower is the

likelihood of the respondents practising contraception or intending to do so.

Tulshi D. Sahi l in his study examines the effects of community factors on

contraceptive behaviour in Bangladesh. In his study the general hypothesis is that the

rural environment influences reproductive behaviour via two mechanisms: the cost of

contraception and the demand for additional children. Although individual

characteristics are recognized as the most important proximate determinants of child

be~ing decisions, the rural environment "sets the stage" for fertility behaviour and

many personal and households characteristics that may be hypothesized to affect more

directly reproductive behaviour.

Logistic regression analysis by Saha22 of the data from various sources in his

study shows that the presence of commercial places has a significant effect on

contraceptive behaviour. If the community has more market-places and a better road

system (commercial centrality), the likelihood of contraceptive use is greater. Also

examined are certain aspects of spatial isolation in rural Bangladesh, looking at the

effects on contraceptive behaviour of the distance between the thana and the district

headquarters. As expected, the distance variable is negatively related to the use of

contraception. This means that the closer the thana is to the district headquarters, the

higher is both the level of contraceptive use and modem method use. Proximity to the

district centre and the presence of commercial places enable the diffusion of

information among potential contraceptive users.

The study by Saha also found that rural electrification might influence

contraceptive use through its effect on income, employment, investment and

consumption opportunities. Rural electrification appears to motivate women to use

contraception sooner than might otherwise be the case. However, the estimated effects

21

22

Tulshi D. Saha, "Community Resources and Reproductive Behaviour in Rural Bangladesh" Asia-Pacific Population Journal. Volume 9, No.1, 1994: 3-18.

ibid.

180

of village electrification are not substantial in size. The effect of the agro-economic

situation on contraceptive use is found negative in the study. If rural areas have more

small farm households and the agricultural wage rate is high (what we call the agro

economic situation), then the women living in these areas are less likely to use

contraception than their counterparts.

The above analysis shows a higher concentration of high contraceptive

prevalence rates only in the northern and western border districts of the country, while

a concentration of low rates appears in the southern and eastern border districts. Based

on this initial description of the spatial pattern, the question asked here is whether an

understanding of this pattern warrants a look beyond the current political borders of

Bangladesh.

Sajeda Amin, Alaka Malwade Basu and Rob Stephenson in their study on

Spatial Variation in Contraceptive Use in Bangladesh23, identify statistical

commonalities in the reproductive behavior of Bengali-speaking groups in the Indian

state of west Bengal that borders some areas of Bangladesh, which are separated by a

political boundary but are otherwise share common language i. e. Bengali and a

common culture.

Historical reasons promote an expectation of some commonalities in behavior

between Bangladesh and the state of West Bengal to the west of Bangladesh that

could serve as a partial explanation for the spatial patterns found within some areas of

Bangladesh. Bangladesh shares an extensive border with West Bengal, an Indian state

that has much in common with the Bengali population of Bangladesh. Apart from a

common political history, Bangladesh and West Bengal share the Bengali language

and a language-based ethnic identity. Thus, the' two areas share a cultural identity in a

way that sets West Bengal apart from the other Indian states that share a border with

Bangladesh.

In the studr4 it was found that women who lived in districts that bordered a

same-language state were significantly more likely to use contraceptives than were

23

24

Sajeda Amin, AlaJca Malwade Basu and Rob Stephenson, Spatial Variation in Contraceptive Use in Bangladesh: Looking Beyond the Borders, Working Paper no. 138, (New York: Population Council, 2000).

ibid.

181

women living in nonborder states in Bangladesh and West Bengal. The study fo~nd ",

that it is not proximity to a border per se, but proximity to a border state in which the

same language is spoken that appears to make a positive impact. A common language

promotes familiarity and, therefore, probably facilitates greater exchange, but a

common language is not enough to guarantee innovative behaviour, The specific

historical context, and in particular the role of language, in conferring a common

identity is important in promoting greater interaction and exchange across political

borders. In the case considered here, Bengali is the language common to both sides of

the Bangladesh-West Bengal border, and speaking Bengali confers upon residents a

common historical and cultural identity and facilitates the spread of ideas across two

politically separated groups.

Having a common language is not the only factor that eases communication

between populations; identification with a linguistic group may be important in

encouraging interaction with groups that share a language identity and in developing a

set of shared values and attitudes as well. This sense of language identity certainly

exists in both Bangladesh and West Bengal. It explains, in part, why the Bengali

speaking populations of Bangladesh and West Bengal who have lived under political

regimes hostile to each other for a considerable part of the last 50 years have enjoyed

continuing cross-border contact and exposure at a popular level through migration, the

radio, the printed media, and more recently, through television. A fair amount of

travel across the shared border apart from migration, has also occurred because the

border has remained relatively open.

The study further goes on to say that language as a way of defining ethnic

identity can influence behavior in several ways. First, by being shared across political

borders, it offers the potential for greater awareness of the world outside national

boundaries. In the case of Bangladesh, the considerable family planning propaganda

that was commonplace in India in the 1960s and 1970s may have been a direct

influence, although modernizing influences of the more urbanized West Bengal are

likely to have had a greater effect in this context. Second, the emergence of new

national and political identities in close proximity sharing a common language may

have resulted in more intense evaluation and scrutiny of such new ideas as family

planning than they would have otherwise received. The two populations examined

here, especially those segments living close to the shared border, may therefore have a

182

heightened capacity to evaluate and accept new influe~~es, such as those being

offered by the family planning program vis-a-vis contraception.

6.4 Urbanisation

The transfer of population from rural to urban areas and the gtowth of cities

are of major concern in the 20th century. Urbanisation has been considered from two

completely different points of view: either as an integral part of development or,

alternatively, as a drain of a country's resources and the antithesis of development.

Bangladesh exhibited very low rates of urbanization throughout the 1940s and 1950s

as there was very little industrial development during that period when it was a part of

Pakistan and hence there was very little incentive to move into towns. The proportion

of urban population to total population increased rapidly from a low 5.2 percent in

1961' to 20.1 percent in 1991 (table 5.6 in chapter 5 of this thesis) with an average

yearly growth rate of 7.4 percent in that period.

A rapid increase in urbanization during the 1970s was stimulated by a high

rate of natural population growth in the rural areas, adverse terms of trade in the rural

sector with the rest of the economy, a high rate of unemployment and

underemployment and sluggish agricultural performance during the decade of 1970s.

Even with the improved performance both by the economy and in the agricultural

productivity since early 1980s, rural-urban migration continued. Besides the attraction

of urban areas and the prospects of better jobs, rural-urban migration was stimulated

by natural hazards such as flood, cyclones and tidal surges that hit the country with

increasing frequency and marriage for women. In addition, frequent riverbank erosion

in Bangladesh results in many rural displacements who migrate to urban areas.

One must also keep in mind that the definition of urban areas has also

undergone a change. In the censuses 1901-1974 normally all places with Municipality

or Town Committee or Cantonment Area were treated as urban. From 1981 onward

Development Centers and Thana Headquarters having distinct urban characteristics

such as the majority of male working population engaged in non-agricultural pursuits,

an identifiable central place where amenities like roads, electricity, community

centers, water supply, sanitation, sewerage system etc. exist and which are densely

populated have also been considered as urban area. Urban areas have been classified

183

into 4 distinct classes for population census, 1991 on the basis of their functions and

sizes:2s -

• Megacity (MC);

• Statistical Metropolitan Area (SMA);

• Municipality Area (MA);

• Other Urban Areas (OUA).

The Metropolitan area having population more than. 5 million

is termed as Megacity. Dhaka Statistical Metropolitan Area is the only

Megacity of Bangladesh, which has enumerated population of 6487459 and

adjusted population of 6844131.26 The City Corporation and the

adjacent areas having urban characteristics have been defined as

Statistical Metropolitan Area. Excluding Dhaka there are 3 SMAs in

Bangladesh namely Chittagong, Khulna and Rajshahi. The incorporated areas

administered i:>y the Government a'> urban area under the Paurashava Ordinance, 1977

are considered as Municipalities. There are 107 Municipalities in Bangladesh.

Given past and present trends, Dhaka metropolitan area COSMA), a megacity

holding over 8 million people, will reach 11 million people at the millennium, 14-16

million by 2010 and 15-20 million by the year 2020.27 Chittagong (CSMA) will

double in size by the year 2010 reaching an expected population in the range of 9-12

million, bigger than Dhaka's today.28 Together, and despite the relatively faster

growth projected for Rajshahi, Khulna and smaller towns, the two urban giants will be

the dominant cities of the next 25 years, home to almost half of the total urban

population or approximately 25-33 million in the year 2020.29 The 'push factor'

driving people to urban centers comes and will continue to come from the inexorable

growtIl of rural population and a lack of employment opportunities there.

2' Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Demographic Report of Bangladesh-I 991. Volume 4, (Dhaka: Ministry of Planning, December 1997).

26 ibid.

27 World Bank and Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies, Bangladesh 2020: A long Run Perspective Study. (Dhaka: University Press Limited, 1998), p. 15.

21 ibid.

29 ibid.

184

Table 6.14 Level of Urbanisation by Division 1981 and 1991

Division 1981 1991

Dhaka 38.52 53.94

Chittagong 38.36 38.72

Khulna 22.41 26.37

Rajshahi 10.34 17.08

Source: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Yearbook of Bangladesh /997 (Government of Bangladesh: Planning Commission, 1997).

The figures on urbanisation in table 6.14 show that Dhaka and Rajshahi are the

two divisions where the urban population has grown substantially during the period

1981-1991. For Dhaka the urban population has gone up from 38.52 in 1981 to 53.94

in 1991which is a phenomenal growth. In Rajshahi, the urban population has gone up

from 10.34 in 1981 to 17.08 in 1991. Khulna shows moderate growth in urban

population from 22.41 in 1981 to 26.37 in 1991. Chittagong shows only 0.36 percent

change in the level of urbanisation during the period 1981-1991.

Table 6.15 Internal Migration Rate by Direction in Bangladesh

Direction Migration rate (percent)

Rural to Urban 51.80

Urban to Urban 4.36

Total Urban Immigration 56.16

Source: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Demographic Report of Bangladesh-/99/, Volume 4, (Dhaka: Ministry of Planning, December 1997)

In the context of the increasing urbanisation the, role of migration is extremely

important in Bangladesh. Professor Nazrul Islam points out that migration has

contributed about 40 per cent to the urban growth in Bangladesh during 1974-81.30

Land scarcity, population growth and better employment opportunities seem to be the

30 CPO Dialogue Report 16, Dialogue on Population, Development and Urbanisation: The Emerging Issues, (Dhaka: Centre for Policy Dialogue, Sunday, July 4, 1999), p. 6.

185

principal factors behind the migration of people from rural to urban areas contributing

to the increasing urbanisation in Bangladesh.

As we see from table 6.15 the direction of migration is from rural to urban

areas. The rural to rural migration flows are movements for marriage and are usually

female dominated when females join their husband3 in their villages. More than 90

percent of the migrations are from rural to urban areas. In Bangladesh, there is a

general east-to-west migration trend, from Chittagong to Dhaka (which is the

principle division of destination for all migration), and from Dhaka to RajshahL31 The

inter-divisional data as presented in table 6.16 shows that Dhaka and Rajshahi are the

two divisions, which have gained people since 1974. Khulna that had been receiving

people till 1974 has substantially lost people to other districts.

Table 6.16 Net Migration by Division in Various Census Years in Bangladesh

Former Net Mierants Division 1951 1961 1974 1981 1991

Barisal 10964 -51140 -199018 -104802 -481000

Chittagong -78407 -208693 -345155 -1378570 -285000

Dhaka -100488 -135106 I 17757 261827 +642000

Khulna 59659 193444 286745 -48369 -298000

Raj shah i 108272 201495 139671 12780 +422000

Source: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Demographic Report of Bangladesh-1991, Volume 4, Ministry of Planning (Dhaka: 1997).

Thus we can say that the migratory flows have been towards the north

(Rajshahi) and the center (Dhaka) and slightly towards the southeastern regions

(Khulna till 1974). This shows th~t people have moved towards the rural areas of

those divisions where employment opportunities are available in the agricultural field.

The gains in the northern region may account for this. Secondly, people have moved

towards urban areas. This is evident by the move of population to Dhaka and

Rajshahi. Thirdly, people have moved to the sparsely populated areas to settle. This

can explain the few gains in the southeastern region. The maximum migration has

been to Dhaka. Dhaka being the capital city became attractive that it alone offset the

31 P Krishnan and G Rowe, "Internal migration in Bangladesh", Rural Demography, Volume 5, 1978: 1-23.

186

I

net loss of the whole region what was generated by the other districts of the region. In

the emergence of this new flow, it became evident that urban migration was getting a

huge momentum.

Thus, the move towards areas providing better occupational opportunities has

been the main reason for migration in Bangladesh.32 The increase: in the rate of

urbanization among other factors is indicative of the differential developmental

allocations between rural and urban areas on one hand, and the responsiveness of the

rural population to the changing realities in their survival efforts and their pursuits of

a higher standard of living and better employment opportunities. Thus we find that the

social relations of production and unequal distribution of resources or one can say

uneven development of the far flung areas has prompted people to move to areas

which can offer them not only better employment but also better quality of life which

comes with development of a region.

6.4.1 Urbanisation and its environmental impact

As the urban popul~tion in Bangladesh has grown rapidly and without any

planning on part of the state, the inadequate urban infrastructure in the country has

reflected problems like inadequate public facilities and poor housing, inadequate

water and power supplies, deficient solid waste disposal and sanitation facilities, air,

noise and water pollution.

For" example unplanned and random filling of low-lying areas of Dhaka has

obstructed the natural drainage system, thus creating environmental problems and an

ecological imbalance in the metropolis. It is estimated that in 1991, the urban slum

population totaled 9 percent (2 million out of the 22.5 million urban inhabitants), with

20 percent of the population of Chittagong and 10 percent each of Dhaka and Khulna

living in slum. (Table 6.17) A recent survey of Dhaka city conducted by the

Department of Environment, revealed that on average, 100 kgs of lead, 3.5 tons of

other particulate material, 1.5 tons of sulphur dioxide, 16 tons of nitrogen oxide, 14

tons of hydrocarbons and 60 tons of carbon dioxide were being released into the

32 R. H. Chaudhary, and G. C. Curlin, "Dynamics of Migration in a Rural Area of Bangladesh", The Bangladesh Development Studies, Volume 3, 1975: 181-230.

187

atmosphere daily from motor vehicles~" which are the cause of air pollution and hence "

a health hazard.33

Table 6.17: Urban Slum Population by Municipal Areas and Other . .. Bid h 1991 Municipalities 10 angla es ~

Urban Area Urban Slum Population Proportion of slum Population (million) population to total

(million) urban population (percentage)

Dhaka SMA 6.844 0.718 10.5

Chittagong SMA 2.348 0.458 19.5

Rajshahi SMA C.545 0.028 5.1

KhulnaSMA 1.002 0.100 10.0

Other 11.716 0.668 5.7 municipalities

All urban areas 22.455 1.972 8.8

Source: S. E. Arifccn and A. Q. M. Mahbub, (cds), A Survey in Dhalca Metropolitan Area-1991, Urban FPI MCH Working Paper No. 11 (Dhaka: International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research-Bangladesh-Centre for Urban Studies, 1993) and Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, A Short Report on the mapping and listing operation of Slum Areas of Bangladesh held during 1994/95, Mimeograph (Dhaka: PDS and SVR Wing and Population and Housing Census, 1995).

Forests resources are also suffering because of over-exploitation, a high rate of

encroachment by the growing population and improper management. Coupled with

the process of deforestation, flawed afforestation programmes have seriously exposed

Bangladesh to environmental vulnerability.34In the Chittagong Hill Tracts area, a

drastic reduction in the recycling period for slash and burn or shifting cultivation is

contributing to deforestation. The recycling period for slash and burn cultivation in

the CHT region is reported to be on a decline from between 15-20 years in 1900 to

between 3-5 years in recent years.3S With increasing aridity and recurrent drought, the

74,200 sq km Barind Tract area in the northwestern region of the country is heading

33

34

K. M. Hassan, "Dhaka Traffic Impact On Environment", Daily Star (Dhaka: 15 November, 1995)

Daily Star, "Loss of soil fertility" (Dhaka, 21" June, 1995).

UN, Population and Environment Dynamics, Poverty and Quality of Life in Countries of the ESCAP region, Asian Population Study Series N. 147, (New York: 1997), p. 35.

188

.-I

towards a se~(,us desertification problem. 36 A changing hydrological cycle, including

a tremendotiS shortage of fresh water in the dry season, is exacerbating the process.

Development projects like the commissioning of the Farrakka Barrage in India

at a distance of 15 m from the Bangladesh border has created problems for the south

western region of Bangladesh. The most devastating effect of the upstream diversion

of Ganges waters has been the marked increase in salinity both in surface water and

groundwater, in the .southwestern region of Bangladesh. Because of the reduction of

the dry season Ganges flow, the salinity in the Khulna area shot up from 380 micro

mho in the 1974 to more than 26000 micro-mho in April 1992.37

The salinity has now moved inland, significantly affecting the greater districts

of Kushita, Jessore, Khulna, Faridpur and Barisal and engulfing more than 25000 sq

km, with an antecedent problem of crop damage and yield reduction, loss of potable

water, an increased incidence of water borne diseases and degradation in public health

affecting the life millions. It has also disrupted industrial operations in the Khulna

industrial belt, entailing a huge investment in importing fresh water over long

distances to keep industrial units working.38

Wi~in strategically located towns that are in line to emerge as new urban

growth centers in Bangladesh, investments in developing infrastructure and other

facilities can further integration and, through well laid-out linkages between satellite

or secondary cities, could promote the growth of a balanced urban system. Although

such a pattern of development could mitigate the unbalanced urbanization now

concentrated in one or two cities, the investment required will be a limiting factor.

Care should be taken not to invest in secondary towns without sufficient economic

justification. Urban developments outside Dhaka primarily depend on the pattern of

investment in physical infrastructure and the nature of future economic development.

For example, completion of the Jamuna Bridge is certain to increase the importance of

Rajshahi SMA (RSMA) as a regional center for the western districts. In addition, the

recent water accord with India may also stimulate new irrigation farming in Rajshahi

36 A Hossain, "World Desertification Day: Bangladesh Perspective", Daily Star, 17th June 1995).

37 M Asafuddowlah, "The Ganges has atrophied; in less than a decade she will die", Holiday weekly (Dhaka, 22- September 1995).

31 ibid.

189

region with a spillover impact on non-farm activities. towns, which could become

important in generating their own economic and demographic "pull", are Raj shahi ,

Nawabgonj, Bogra, Naogaon, Sirajganj, Joypurhat, and Natore in the western

districts. Northwestern district towns, such as Gaibandha, Dinajpur, Nilphamari,

Lalmonirhat, and Kurigram, are also likely to receive spillover benefits depending

upon the specific economic response to the new opportunities created by the Jamuna

Bridge and new regional transport links.

Though the level of urbanisation in the CHT has been almost negligible

internal colonization in the CHT by the government in Bangladesh to contain ethnic

minorities and to exploit the natural resources of the sparsely populated area of the

CHT has created enormous environmental damage to the area. Migration to CHT has

been of two types; one natural and the other political. Natural migration included

people who migrated in search of jobs and business opportunities. The political

migration was the influx of settlers under government sponsorship from other districts

of the country.

In 1978-1979, the Bangladesh government decided to launch a secret scheme

to organize and subsidize the settlement of tens of thousands of new Bangladeshi

immigrant families each year. Between 1978 and 1984 the government of Bangladesh

transferred half a million poor Bangladeshi settlers to CHT for political purpose. They

were allotted free ration, housing and other facilities including agricultural land. The

provisions of the 1900 CHT Regulation related to land settlement and transfer were

amended for providing land rights to the settlers. The Army and other law enforcing

authorities and the settlers committed massacres, genocide, riots, arsons, religious

persecutions, rapes etc. to drive out the indigenous people from their lands and

homesteads and to make room for the settlers. The Shanti Bahini responded by an

armed struggle, albeit a low-level insurgency in the area. The repressive action of the

Bangladeshi forces in reaction to the insurgency by the Shanti Bahini forced them

tribal people to take refugee in the neighbouring states ofIndia.39

Side by side the CHT conflict was identified publicly as economic problem,

with an aim to mislead the international community as well as to have fund for

implementation of the plans and programs against the Shanti Bahini and the

39 Saleem Samad, "Environmental Refugees ofCHT', Holiday, (Dhaka: 12 November, 1994).

190

indigenous people. In the name of developm~nt of livelihood of the people and the

CHT, in 1976 the CHT Development Boru-d was established. In reality the CHT

Development Board formulated and implemented anti-insurgency plans and

programs, such as, construction of road networks to facilitate military deployment in

the remote part of the CHT, deforestation to deprive the Shanti Bahini guerillas

hideout etc. From its creation up to June 1999, the Board has implemented 1,135

socio-economic development projects, spending TIc 685 million for the development

of the region.4o

In 1982 the G.O.C (General Officer in Command) of24 Infantry Division of

Bangladesh Army who was empowered to launch military operation in CHT was

made Chairman of the CHT Development Board. He utilized the fund provided by

various international organizations like Asian Development Bank, World Bank etc.

for implementation of development projects in the CHT for military purposes and

resettlement of the Bangladeshi settlers from the mainland Bangladesh.

Developmental projects like the Kamaphuli hydro-electric project for example

submerged 54,000 acres of settled cultivable land affecting about 100,000 people, 90

percent of whom were chakmas.41

The Bangladeshi settlers, with the connivance of the almost totally

Bangladeshi administration, have been able to take over land and even whole viIlages.

There is a severe population pressure cn land in Bangladesh generally and the land in

the CHT has been regarded as readily available. One excuse often given for allowing

or encouraging this immigration is the relatively low population density in the CHT.

In 1988, further settlement of Bengalis into the CHT was stopped by a government

order under Ershad's regime. However it was under the regime of Sheikh Hasina in

1997 a accord was signed between the government and the tribal leaders whereby a

CHT regional council would be set up which will d.irect and supervise the

dev.!lopment process in the hill area and resettlement ofChakma refugees·from India.

The process of forced settlement by the Bangladeshi government has led not

only to the alienation of the Chakmas from their land, economic life and culture but

40 UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Reports Suhmilled by States Parties under Article 9 of the Convention, Bangladesh, CERD/C/379/Add.1, 30 May 2000, p. 8.

41 Partha. S. Ghosh, "India-Bangladesh: Love's Never Lost" in Cooperation and Conflict in South Asia, (Dhaka: University Press Limited, 1989), p. 74.

191

have brought significant demographic changes in Bangladesh. This is clear from

large-scale migration from Chittagong (table 6.16) and the low rise in urbanisation in

the area. Political migration along with government sponsored development projects

have displaced population not only within the country but also outside and has also

played havoc with the development of the area.

Thus various development projects like the Kamaphuli multipurpose and

horticulture projects failed owing to a lack of understanding of the Hill people's needs,

desires and wishes and the ignorance of planners about the likely damage to the

environment. In the sixties, seventies and early eighties, planners in the developing

world were unaware of environmental impact of developmental projec'ls as a result of

which no environmental impact assessment was conducted. Therefore, the Kamaphuli

mUltipurpose and horticulture projects had nothing to do with the tribal insurgency, as

both projects had been set into motion prior to the outbreak of the conflict. Projects,

which were Undertaken after the emergence of Bangladesh, during the period of the

insurgency, had failed primarily because of the political motivation behind them. The

purpose behind the projects was to dampen the ongoing insurgency by pouring money

into development projects in the mistaken belief that once the region was developed,

there would be no feeling of deprivation among the tribal people.42

6.5 Employment Scenario in Various Divisions in Bangladesh

Labour force participation is affected by many different factors: most

importantly, by the extension of schooling, changes in the economy and changes in

cultural nonns about appropriate activities for women. Table 6.18 shows the

economically active population by sex and division in Bangladesh for the period

1974-1991.

It is observed that during the period 1974-1991, the male population for

Bangladesh has increased by about 54 percent43, while the economically active male

has increased by about 44.41 percent (table 6.18). The high proportion of young age

popUlation entering into education could explain the slow rate of labour force growth

~1 CPD Dialogue Report 28, Dialogue on Population and Sustainable Development: Selected Issues a/Greater Chillagong,( Dhaka: Center for Policy Dialogue, 2000), p. 6.

43 Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Yearbook 0/ Bangladesh 1997 (Government of Bangladesh: Planning Commission, 1997), p. 24

192

among males. On the other hand a rapid growth in female labour force has been

observed.

Table 6.18 Economically Active Population in Bangladesh by Division for Various Census Years

Division Economically Active Population in '000' 1974 1981 1991 1974-1991(percent

chan~e)

Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Bangladesh 19650 877 22430 1189 28378 2289 44.41 161

(304031 (21879) Raj shah i 4694 229 5459 328 7058 511 50.36 123.14

(7522) (5403) Khulna 2317 64 2779 84 3469 225 50 251.56

(3715) (2707) Barisal 1436 44 1545 55 1867 146 30.01 231.8

(2038) (1552) Dhaka 6014 216 7072 415 9106 793 51.41 267.1

(9680) (6650) Chittagong 5189 324 5575 307 6878 614 32.54 89.5

(7448) (5567)

Source: Government Of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Analytical Report of Population Census 1991-Volume I, (Dhaka: Statistics Division-Ministry of Planning, May 1994)

Note: Figures in the parenthesis are adjusted so as to include household based economic activity.

Many studies have shown that women's economic activities in societies such

as Bangladesh are hidden or disregarded because the society perceives their work as

more wifely or daughterly duties than as economic contributions.44 Though the female

population has increased by 57.0 percent4S during 1974-1991, the economically active

female has increased by 161.0 percent. (Table 6.18)

It is also noticeable from the table 6.18 that over the period 1974-1991 the

percentage change in economically active population in Bangladesh is higher among

females than males for Bangladesh as a whole and in all the divisions. The largest

increase in labour force in Dhaka and Khulna divisions for males and females may be

explained by the in-migration of working force from the other divisions in search of

wider employment opportunities. Female labour force for all the divisions shows an

increasing trend during the period 1974-1981. But the percentage change in female

Barkat-e-Khuda. "Female employment in Bangladesh: Evidence from Census and Micro Level Studies" Demography India, Volume 14, No.2, 1985:236-246 and Ben J. Wallace, Rosie Mujid Ahsan, Shahnaz Huq Hussain and Ekramul Ahsan, The Invisible Resource: Women and Work in Rural Bangladesh (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1987).

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Yearbook of Bangladesh 1997 (Government of Bangladesh: Planning Commission, 1997), p. 24.

193

economically:::active population for Chittagong shows a slower rate of increase as

compared t~;'the percentage change for other divisions. (Table 6.18)

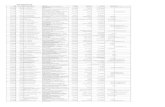

Table 6.19 Crude Activity Rates for Population by Sex and Division in BId h 1961 1991 an~a es,-,- -

rnvlsioa Crude Aclivl~ Rales 1974 1911 1991 ~rcetll chule 1981-1991

BoIIiSe Male Fe .. ale Bolio Male F_al BolloSes Male F_ale Bolio Male Fe.ale Sex Sex

Ban,ladWI 21.7 53.0 2.5 27.1 49.9 2.8 28.8 R9 4.4 6.27 4.0' 57.1 (47.Ql ~3.!l ..i40.~

Rajshalti 21.4 52.7 2.7 27.3 50.4 3.3 28.9 52.6 4.0 5.86 4.36 21.21 _(47.!l ~3.~ ..i40.~

Khulna 27.2 R3 1.6 26.0 49.0 1.7 29.1 53.1 3.7 11.9 8.36 117.64 ~48.~ ~4.~ ..i42.!l

Barisal • • • • • • 27 49.2 4.0 - - -(46.0) (51.3) (40.5)

Dhaka 29.2 54.0 2.1 28.5 RI 3.3 30.3 53.6 5.1 6.31 3.47 S4.S4 (47.8) (54.5) (40.5)

Chillaaon, 29.6 53.4 3.6 26.0 46.3 1.9 27.S 49.2 4.6 5.76 6.26 142 (4S.6) (SO.9) (40.0) -

Source: Government Of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Analytical Report of Population Census 1991-Volume I, (Dhaka: Statistics Division-Ministry of Planning, May 1994)

Note : Figures in the Parenthesis show crude activity rate including household based economic activity.

• Part ofKhulna Div:sion

Crude activity rate is an approximate measure of the size of the labour force. It

is defined as the ratio of economically active population 10 years and over to the total

population of all ages and expressed in percentage. The crude activity rate by division

during 1974.-1991 (as can be seen from Table 6.19) indicates that the rate has fallen

down in 1981 as compared to the rate for 1974 for all the divisions but goes up in the

year 1991. Table 6.19 shows the decreasing trend in crude activity rate for all the five

divisions over the decade for the period 1974-1991 except for Khulna and Rajshahi.

In 1974 the crude activity rate was 28.7 for Bangladesh as a whole, which came down

to 27.1 in 1981 then going up to 28.8 in 1991. (Table 6.19)

For male and female the same at national level was 53 and '2.5 in 1974 which

has fallen at 51.9 and 4.4 respectively in 1991. (Table 6.19) This reduction in crude

activity rate over two decades indicate partially the higher attendants rates of boys and

girls in schools and colleges and also the effect of changes in definition. The fall in

the national female activity rate during the period 1974-1991 may be due to the

exclusion of household works from economically active population both in 1981 and

1991 censuses. The percentage change in crude activity rate (table 6.19) for the period

1981-1991 shows an increase for the country as well as for all the divisions. The

194

percentage change in crude activity rate for the period 1981-1991 is higher for

females in all the divisions as compared to males.

Table 6.20 shows the main source of household income by division. It is found

that the dependency on agriculture and own lan~share cropping as a source of

household income is the highest in Rajshahi division i.e. 70.8 percent and the lowest

in Chittagong division (53.4percent). The dependency on employment as a source of

income is the highest in Chittagong division (13.4percent) and the lowest in Rajshahi

division (6.4percent). (Table 6.20) In business as a source of household income the

dependency is the highest in Dhaka division (14.5percent) and the lowest in Rajshahi

division (10. 7percent). The dependency on non-agriculture labour as a source of

household income is the highest (3.9percent) in Barisal Division. Thus one finds that

the main occupation in all the divisions still remains to be agriculture.

Table 6.20: Main Source of Household Income by Division-1991.

Main Source Raj.babl Kbulna Barisal Dhaka Chittllgong or Household

Income No. percent No. percent No. percent No. Percent No. percent

Own land/share 8279 47.9 3731 41.9 1112 42.0 8687 39.3 6419 35.8 cropping

Livestock 66 0.4 27 0.3 18 0.4 72 0.3 78 0.4

Forestry 2 0.1 16 0.2 2 0.1 8 0.3 68 0.4

Fishing 132 0.8 114 1.3 168 3.3 246 1.1 329 1.8

Pisciculture 14 0.1 37 0.4 6 0.1 18 0.1 30 0.2

Agricultural 3717 21.5 16S3 18.6 842 16.7 308S 13.9 26S7 14.8 Labour

Non-agricultural. 484 2.8 314 3.S 19S 3.9 S26 2.4 673 3.8 Labour

Handloom 137 0.8 S8 0.7 7 0.1 211 1.0 S9 0.3

Industry 154 0.9 103 1.2 28 0.6 269 1.2 194 1.1

Business 18S3 10.7 1184 13.3 658 13.1 3204 14.5 2446 13.7

Hawker 39 0.2 20 0.2 II 0.2 90 0.4 47 0.3

Transport (Non- 18S 1.1 ISS 1.7 S3 1.1 411 1.9 264 I.S Meeh) .-Transport (Mech) 53 0.3 38 0.4 14 0.3 159 0.7 128 0.7

Construction 127 0.7 86 1.0 64 J.) 266 1.2 200 1.1

Religious - - - - - - - - - -Employee 1098 6.4 811 9.1 428 8.S 2918 13.2 2405 13.4

Rcnt/Remittancc 10 0.1 12 0.1 6 0.1 142 0.6 161 0.9

Service 918 5.3 538 6.0 415 8.3 1820 8.2 1748 9.8

Others - - - - - - - - - -Source: Government Of People's Republic of Bangladesh, Analytical Report of Population Census

J99J-Volume J. Ministry of Planning, (Dhaka: May 1994).

195

A look at table 6.21 shows that the daily average agricultural';Vage has not