Creating and Using Interactive Presentations in Distance ...

Creating a Large-scale, Third Generation, Distance Education Course

-

Upload

martin-james -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Creating a Large-scale, Third Generation, Distance Education Course

This article was downloaded by: [University of California Davis]On: 10 November 2014, At: 22:15Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,UK

Open Learning: The Journal ofOpen, Distance and e-LearningPublication details, including instructions for authorsand subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/copl20

Creating a Large-scale, ThirdGeneration, Distance EducationCourseMartin James WellerPublished online: 19 Aug 2010.

To cite this article: Martin James Weller (2000) Creating a Large-scale, ThirdGeneration, Distance Education Course, Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distanceand e-Learning, 15:3, 243-252

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713688403

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all theinformation (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform.However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make norepresentations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness,or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and viewsexpressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, andare not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of theContent should not be relied upon and should be independently verified withprimary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for anylosses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages,and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of theContent.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan,sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is

expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttp://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

Open Learning, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2000

Creating a Large-scale, Third Generation,Distance Education CourseMARTIN JAMES WELLERThe Open University, UK

ABSTRACT T171 ‘You, your computer and the Net’ is a large-scale distance educationcourse produced at the Open University in the UK. It offers an introduction to computersand the Internet aimed at a wide audience. The course is tutored entirely online and isdelivered via the World Wide Web. This paper outlines the course team’s strategy fordealing with a number of issues that arose as a result of the aims of producing such a coursewhich maintained the traditional quality of Open University material, whilst being adaptedfor a new presentation model. These issues included developing appropriate student skills,maintaining quality control, facilitating easy updating of material, ensuring studentinteraction with the material, and making the material accessible and meaningful to abroad range of students. The manner in which each of these issues has been addressed isoutlined. The course structure is a modular one based around accessible set texts, with wraparound academic material on the course web site. The course was piloted in 1999 with 900students, and demand for the course has been very high, with some 9000 students enrollingfor the course in 2000.

Introduction

Use of the Internet, and the web in particular, for distance education has been onthe increase with the development of third generation courses (Nipper, 1989). Suchcourses are characterised by two-way communication media which allow for interac-tion between the originator of the material and the student, between tutor andstudent, and between students. Virtual universities and Internet based courses areexamples of this third generation.

The use of the Internet as the delivery mechanism for distance education offers anumber of advantages over conventional methods:

1. Quick production. Traditional print or broadcast material can take a long time toproduce.

2. Quick alteration and up-to-date course material. Conventional materials such asprint, television, computer-based learning programs and so forth can be costly toalter on a large scale. Course material can therefore be kept up-to-date, which isparticularly relevant for fast-changing � elds such as ICT education.

ISSN 0268-0513 print; ISSN 1469-9958 online/00/030243–10 Ó 2000 The Open University

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

244 M. J. Weller

3. Interaction with, and feedback from, students. Interaction with tutors, thematerial’s originators, and other students, offers a much richer learning environ-ment for students. It also enables feedback on the material from students muchquicker than in a conventional distance education model.

4. Interactive materials. Use of interactive assessment tools, simulations, and ani-mations can be offered over the web. This increases the variation in material andthe level of activity for the student in the learning process.

5. Flexibility in study patterns. Students can study asynchronously and still partakein collaborative work, group discussions, and receive timely feedback from theirtutor.

It has a number of limitations also, which mean it is not suitable for all types ofmaterial, or teaching methodologies. It is poor in comparison with most conven-tional methods of delivery when issues of access and cost are considered. Particularlythere is a shift in some costs to the student, such as connection and printing costs.As is mentioned later the study method suggested in this course was to utilise thecomputer as the study tool, but many students still resorted to printing out much ofthe material. Provision of of� ine versions of the material also helped reduce connec-tion costs. The restrictions on bandwidth mean that delivery of video is still limitedfor educational purposes for most students who are accessing with a 28K modem.

Bates (1995) states that there is a tendency with new technologies to attempt tomimic the traditional classroom face-to-face method of teaching, or to add newtechnologies onto an existing model. This negates any advantages offered by anInternet-based delivery method, whilst increasing the cost of the course production.The use of web delivery has met with mixed success. Ward and Newlands (1998),for instance, report that students exercised a greater choice over study time, and hadless time and � nancial expenditure with web-based material compared to conven-tional lectures. However, they did not utilise the web fully, and often resorted tosimply printing out the materials. Warren and Rada (1998) report that in order toduplicate the productive interchanges found in face-to-face sessions, it was necessaryto impose certain practices on computer conferences, including stringent deadlinesfor participation.

T171 You, Your Computer and the Net is an ICT entry-level course developed atthe Open University in the UK (OU). Its aim is to take computer beginners andprovide them with the skills needed to function productively with a personalcomputer and the Internet. It also aims to provide knowledge to place thesetechnologies in context, so that by the end of the course students are comfortableboth with using them and conversing about them and their wider implications.

Production of ICT courses has traditionally posed something of a problem fordistance learning establishments, in that it is a rapidly changing � eld. A traditionalprint-based OU course typically takes three to four years to produce and will be inpresentation for eight years. This means the course material needs to have a shelf lifeof up to twelve years (although partial rewrites are often undertaken to modernisematerial part way through a course). Most OU courses consist of materials that havebeen written speci� cally for the course. This is undoubtedly an expensive approach,and one model for overcoming this expenditure is to use existing texts, and provide

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

Creating a Distance Education Course 245

wrap-around academic material. This has been used successfully on some OUcourses (e.g. Weller & Hopgood, 1997). The traditional print-based production hasmeant that the OU has concentrated its investment in the production process toproduce materials as near to perfect on the � rst presentation. The costs during thepresentation stage of the course are then much lower. The feedback from studentscombined with the production methods means that changes to course material cantake some time to put into effect.

Given the factors outlined above, there were several aims for T171, which can besummarised as:

1. To produce a large-scale, broad appeal ICT course.2. To design a working method which allows for rapid production and alteration.3. To utilise an effective teaching methodology which would maximise the advan-

tages the Internet offers as a delivery mechanism.4. To teach both traditional study skills and those required to work effectively with

the new technology.

In order to achieve these aims we were therefore faced with a number of issues whichhad to be addressed:

1. How to ensure that students develop new skills of working with this technology,for example avoiding the ‘print it all out’ strategy described above.

2. To develop material which matches the OU’s usual high standards but in ashortened time scale.

3. To ensure that material can be updated or replaced easily without extensivecourse rewrites.

4. To ensure that students engage with material effectively, when they are unfam-iliar with the topic. This is what Laurillard (1998, p. 235) refers to as Meno’sparadox—‘How can you learn something you know nothing of?’.

5. To make material accessible to a wide range of students with different back-grounds and different needs.

The manner in which these � ve main issues were addressed in the course will bedetailed separately.

Developing New Skills

The traditional method of ensuring students develop skills is to integrate themwithin the assessment of the course. T171 uses HTML as the working format of thecourse, which means students are required to produce their assignments as HTMLdocuments, and their working notes are also in this format. Students were requiredto formulate their notes so that they developed into a study journal over the course.They were directed by exercises at various stages to develop this journal. Forinstance, one activity requires them to reformulate their journal, producing a newindex page according to categories representing their own interpretation of thematerial. This notion of organising material in different ways, and use of hypertextas a means of thinking about and working with material, is a skill the course team

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

246 M. J. Weller

believes will be of value as the information content students are required to deal withcontinues to grow.

Assessment in T171 is ostensibly web-based, in that students are required todevelop a small website for their end of course assessment, as well as ‘web-essays’for their continuous assessment component. This is assessed not only on its content,but also in its structure, design, use of the Internet as a resource, and so forth. Inthis manner the importance of producing material for this new medium is rein-forced.

By using interactive material, such as simulations of a modem connecting to aremote computer or microprocessor operation, and interactive questions, additionalbene� t is placed within the material. This provides an educational motive to engagewith the material in its presented form, rather than reverting to prior study patterns,such as printing large quantities of the content.

The course team realised that students often need to work away from theircomputers. Two independently published set texts were therefore used in the course(Cringely, 1996; Hafner & Lyon, 1998), which tell the basic story of the develop-ment of the personal computer and the Internet, respectively.

There was a strong emphasis on collaborative work via CMC in the course.Students were therefore required to engage in communication with other studentsand to co-ordinate their efforts. This was one aspect of the emphasis on computerconferencing in the course, which has no face-to-face tuition.

Producing High Quality Material in a Short Time Scale

In order to produce teaching material in a shorter time scale than has been possiblepreviously, a number of decisions were taken. The � rst was to make the web thecentral method of delivery for course materials. The immediacy of the presentationmethod, and the proximity of the author to the � nished material, allowed for aquicker production cycle than print usually permits. This occurs primarily becausethe format facilitates iteration with the editor, and because removal of print sched-ules means the deadlines for � nishing material can be much closer to presentation.For instance, changes to the second module (see below) were still occurring whilstmodule 1 was being presented. A second major decision was to create a modularstructure. T171 consisted of three modules, with one academic author assigned permodule, with the other authors and course team performing the task of criticalreview. The modules were largely independent of each other, thus allowing parallelproduction. This is in contrast to traditional OU courses, particularly in thesciences, where modules often build on concepts introduced in earlier modules, thusrequiring sequential production and considerable cross-checking to ensure coher-ence is maintained.

The modules forming T171 can be summarised as follows:

· Module 1: Becoming a con� dent computer user—an introduction to basic com-puter skills and applications, using the Internet and group working. The materialwas taught in a generic manner, so it was not software package speci� c.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

Creating a Distance Education Course 247

· Module 2: The story of the personal computer—using the set text, AccidentalEmpires (Cringely, 1996), to tell the basic story of the development of thecomputer, the module explores technological, social and economic issues raisedby the material.

· Module 3: The story of the Internet—using the set text, Where Wizards Stay UpLate (Hafner & Lyon 1998), again to tell the basic story of the development of theInternet, the website material explores issues such as the development of proto-cols, paradigm shifts, and the social impact of the Internet.

Another important feature of the production model was the use of set texts. Theseformed the function of telling the ‘basic story’ of modules two and three. Both booksare very readable accounts of their respective stories, and not traditional academictexts. The web site represents the academic content, which wraps around the settexts.

The use of web-based material means the traditional roles of author, editor anddesigner are much less clearly de� ned than with a conventional course. Theproduction of material was therefore a more iterative process than in standardproduction. However, the author is much closer to the � nished material. The use ofdesign templates means the author can quickly produce material which is close tothe � nished article, although it still requires editing, reviewing and some � ne-tuningof design.

Easy Updating

The use of web-based material over print means material can be updated mucheasier and at considerably less cost. This is particularly relevant in a rapidly changing� eld. By making the course web-based, the course team could make use of externalwebsites which maintain up to date material on issues which are developing duringthe course. For example, the Microsoft anti-trust case in the US was of relevance toModule 2, but rather than continually update material, reference was made toexternal sites which were monitoring this case. Reliable external websites wereselected which could be relied on to maintain their content, but there is still aresponsibility on the module authors to ensure links remain valid. This meansauthors have to maintain a more active role in maintenance than is usual for OUcourses. This, combined with other aspects such as the need to update material andthe demand of computer conferencing, represents a shift in the workload, withpresentation now becoming a more substantive task than in the traditional OUcourse model. This has implications for the � nancial model of course production.

The modular approach offers the advantage of easy updating as well as quickproduction. The modules were independent to a degree, which means material inany module can be easily altered without inducing large changes throughout thecourse. This independence of modules was not absolute, as there was some inte-gration to allow for the development of study skills through the courses. Althoughthis has some implications for maintenance, the knock-on effects of any changes are

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

248 M. J. Weller

kept to a minimum, whilst ensuring progression of study skills for students throughthe course.

Engage with Material

Module 1 in particular was structured around an activity-based learning model. Forexample, using the web was formulated as a scenario where a small group ofstudents were required to create a web channel, each taking a particular topic. Thisformed part of the assessment for Module 1, so students were required to partakein the activity. A portfolio of evidence formed part of the end of course assessment,so students were required to produce evidence of conferencing, note taking, sum-marising and so on. In this manner the assessment reinforces various methods bywhich students can engage with the material, and with each other.

This emphasis on conferencing and group learning places learning as a socialfunction (Bates, 1995, p. 53). It is therefore important to introduce students to theuse of CMC early in the course, and to increase their communication skills. Salmonand Giles (1999) have proposed a progressive � ve-stage model for effective CMCuse. This can be summarised as:

· Stage 1—Gaining access to and using the CMC system. These are the pragmaticissues of setting up software, getting connected and sending some messages.

· Stage 2—Becoming familiar with the online environment. At this stage thestudents become accustomed to sending messages, and the rules of behaviour inthis environment.

· Stage 3—Asking for and giving information. This is a useful stage for manystudents, and often this is the level they remain at. At this stage students requestinformation of the tutor or other students, for example regarding an assignment,and freely exchange information.

· Stage 4—Group discussion. At this stage the group works together with a speci� coutcome, and with different roles.

· Stage 5—Looking for additional bene� ts. At this stage students are responsible fortheir own learning, and need little support.

In Module 1 in particular students are carefully brought through these stages bymeans of a number of exercises, for example setting up the client software for theFirstClass conferencing system is an early activity (Stage 1). Students then proceedthrough some exercises where they send messages to dummy students and discusstheories of group behaviour as part of a group activity (Stage 2). They are directedto speci� c support conferences to gain help with software packages, e.g. Windows,Of� ce software, etc. (Stage 3). An element of the � rst two assignments is basedaround group work, where students have to work towards a group goal, such asproducing a web channel (Stage 4). By the time they commence Module 2 moststudents should be at stage 4 and some at stage 5. The material in Modules 2 and3 could therefore rely on these skills being in place, and utilise discussion as alearning method.

Throughout the course ‘study guides’ are delivered fortnightly as an e-mail

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

Creating a Distance Education Course 249

attachment. In Modules 2 and 3 the students adapt these to create their own studyjournal on their hard disks. There are also a number of tutor group activities whichallow students to share information, and to compare study approaches. As has beenmentioned, the assessment model reinforces the importance of this approach.

Accessibility

T171 was aimed at a broad audience, not just technology or computer students. Asan entry-level course it did not assume any prior knowledge, and many students maybe new to study, or returning after a long time away from study. The coursetherefore needed to be accessible to a wide range of students. One key aspect inachieving this accessibility was the use of the readable set texts mentioned above.This approach uses a narrative-based method as a means of exploring the issuesraised by the material. The importance of narrative as an educational methodologyis emphasised by the use of multimedia, where many students feel ‘lost’ without aconventional narrative structure to guide them through (Plowman, 1997). This isparticularly germane to web-based material, where hyperlinked documents providea much looser narrative structure. In addition many students feel intimidated byconventional computer science-based courses. The narrative-led teaching methodol-ogy places an emphasis on demythologising the subject, by placing it within acontext. It also allows the material to naturally cover a broad spectrum of issues,including the technology (for example the architecture of a computer), the socialimpact of computers and the Internet (for example the implications of the ‘Infor-mation society’), the industry (for example the role of Microsoft) and so on.

There was some preparatory material, which was based around an existing OpenUniversity pack called ‘Working With Windows’. This would allow students whowere complete beginners to start the course with some familiarity of the basicoperation of a personal computer. There were a number of other exercises includinga web browser tutorial and a keyboard tutor. This allows students with a broad rangeof experience to study the course.

Once again the use of conferencing aids the realisation of this aim. Within thematerial there are a number of ‘embedded conferences’ that focus on a seededdiscussion relating to the material students have just read. There were also a numberof support conferences where students could ask for speci� c help from their peers,and from expert moderators. These covered various software packages, e.g. generalWindows support, word processors, HTML, etc.

Course Presentation

The course has the overall structure of three modules, with a website addingacademic wraparound material to readable set texts. The course lasts for 32 weeks,with four tutor-marked assignments (TMAs) and one end of course assessment.Students are guided through the material by regular study guides which are deliv-ered as e-mail attachments. Tuition is conducted online and a number of group

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

250 M. J. Weller

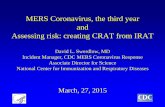

FIG. 1. T171 course structure.

activities are embedded within the material. The course structure can be sum-marised in Figure 1.

A pilot study of the course was presented in 1999, with over 900 students.Demand for the course was considerable, and estimates for student numbers in2000 are in excess of 9000. The drop-out rate for students on the pilot presentationof T171 was slightly more than that of the existing entry-level foundation course,T102, which had been running for � fteen years. The demographics of the currentcohort of students show that the course is divided fairly evenly according to gender(approximately 44% female), a large proportion of students are new to the OU, andmany of them are principally taking non-technological degree pro� les. Detailedevaluation of the course is being undertaken.

Further Issues and Conclusions

T171 raises a number of broader issues for the Open University. As mentioned,there is an increase in the presentation load of such a course, both in the effortrequired to continually update material, and the workload associated with intensiveonline communication. This is in contrast to the traditional OU course model,where presentation is relatively low in terms of course team effort and additionalcosts. What such a shift in presentation costs (both in terms of � nances and

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

Creating a Distance Education Course 251

resources) may mean for the OU’s course production model has yet to be fullyexplored.

Another area of broader signi� cance is that of assessment. Students are encour-aged to participate in group activities, and much of the rapid growth of the web itselfhas been facilitated by the easy proliferation of design, images, etc. However, thismakes the plagiarism easier to perpetrate and potentially more dif� cult to detect.The use of portfolio based assessment goes some way to address this. Due to theregular and often intense interaction with students over the duration of the course,many tutors reported that they established a good relationship with their students,and thus were able to verify work as being that of the student. Working in thismedium offers possibilities for structuring, design, and use of external resourceswhich challenge the conventional forms of assessment. This is an area which this,and similar, courses have only begun to address, both in terms of what students areasked to produce and how that work is assessed and monitored.

We can now review the original aims of the course, and see to what extent thesehave been satis� ed by the model outlined above. The � rst of the aims was toproduce a large-scale, broad appeal course. The student demand for the course, andthe diversity of the student cohort, seems to indicate that, at this stage at least, thishas been achieved. The second aim was to devise a working method to allow forquick production and alteration of material. The course, which is designed to engagea student for some 200 hours and leads to the award of 30 CATs (Credit Accumu-lation and Transfer) points, was produced in a year, which represents a considerableimprovement on most OU course production cycles. Much of the time was spent indevising the working model, and setting up a suitable technical structure for thecourse. Much of this is a one-off investment, and future courses which adopted asimilar model could improve upon this time frame even further. There are a numberof such modules now in development in diverse topics. The third aim was to utilisethe Internet as a delivery mechanism by adopting a suitable teaching strategy. Theuse of the web material plus set text, in addition to the emphasis on conferencingand group work, suits the material, and offers the advantages of the Internet outlinedat the start of this paper. Whether it is an effective learning mechanism for studentscan only be known in detail when full evaluation of the course has occurred. The lastaim was to teach both traditional and new study skills. The use of exercises, groupwork and the assessment strategy has been the means by which this has beenimplemented. Again early feedback is positive, but � rm conclusions must await theoutcome of the evaluation.

In conclusion the model developed by T171 seems to support large-scale thirdgeneration distance education courses, which are distinct from ‘campus’ models,and in many aspects from the � rst and second generation distance educationmodels.

Dr Martin James Weller, Lecturer in Telematics, Faculty of Technology, The OpenUniversity, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK. E-Mail: [email protected]

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014

252 M. J. Weller

References

BATES, A.W. (1995) Technology, Open Learning and Distance Education (London, Routledge).CRINGELY, R.X. (1996) Accidental Empires (London, Penguin).HAFNER, K. & LYON, M. (1998) Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet (New

York, Simon & Schuster).LAURILLARD, D. (1998) Multimedia and the learner’s experience of narrative, Computers and

Education, 31, pp. 229–242.NIPPER, S. (1989) Third generation distance learning and computer conferencing, in: R. MASON

& A. KAYE (Eds) Mindweave: Communication, Computers and Distance Education (Oxford,Pergamon).

PLOWMAN, L. (1997) Getting Sidetracked: Cognitive Overload, Narrative and Interactive Learn-ing Environments, in: Virtual Learning Environments and the Role of the Teacher, Proceedingsof UNESCO/Open University International Colloquium, Milton Keynes, UK.

SALMON, G. & GILES, K. (1999) Creating and implementing successful on-line learning environ-ments: a practitioner perspective, European Journal of Open and Distance Learning, Feb.1999. Available at http://kurs.nks.no/evrod1/eurodlen/index.html

WARD, M. & NEWLANDS, D. (1998) Use of the Web in undergraduate teaching, Computers andEducation, 31, pp. 171–184.

WARREN, K.J. & RADA, R. (1998) Sustaining computer-mediated communication in universitycourses, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 14, pp. 71–80.

WELLER, M.J. & HOPGOOD, A.A. (1997) Implementing a Learning Model for a Practical Subjectin Distance Education, The European Journal of Engineering Education, 22 (4), pp. 377–389.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

alif

orni

a D

avis

] at

22:

15 1

0 N

ovem

ber

2014