COVER: Marines of Company - Marines.mil - The Official ... Cause Marine... · COVER: Marines of...

Transcript of COVER: Marines of Company - Marines.mil - The Official ... Cause Marine... · COVER: Marines of...

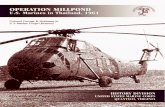

COVER: Marines of Company K, 3d Battalion, 6th Marines, cautiously approach the Panamanian Defense Force station in Vera Cruz during a search of the town. (Photo courtesy of Sgt Robert C. Jenks).

Just Cause: Marine Operationsin Panama 1988-1990

byLieutenant Colonel Nicholas E. Reynolds

U. S. Marine Corps Reserve

HISTORY AND MUSEUMS DIVISION

HEADQUARTERS, U.S. MARINE CORPS

WASHINGTON, D.C.

1996

Just Cause: Marine Operations

in Panama 1988-1990

by

Lieutenant Colonel Nicholas E . Reynolds

U. S . Marine Corps Reserve

HISTORY AND MUSEUMS DIVISIO N

HEADQUARTERS, U .S. MARINE CORP S

WASHINGTON, D .C .

1996

PCN 190 003134 00

For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office

Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328

ISBN 0-16-048729-3

PCN 190 003134 00

For sale by the U .S . Government Printing OfficeSuperintendent of Documents, Mail Stop : SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328

ISBN 0-16-048729-3

Foreword

The history of Marines in Panama from 1988 to 1990, the years bracketing OperationJust Cause, does not involve a great many Marines, and Marines made up only a small percent-age of the forces that went into battle during the operation itself in December 1989. But for aperiod of more than two years, the Marines in Panama were literally in foxholes on the frontlines. For the individual Marine, going to Panama meant going in harm's way. Although mostplanners thought of Panama in terms of low intensity conflict, the personal experience for manyMarines was very intense, and tested their courage, endurance, and professionalism.

One measure of the intensity of Just Cause lies in the fact that the contribution to thesuccess of the operation by Marine Forces Panama was Out of proportion to its size—that is,greater by far than for most other units of comparable size, measured in terms of prisoners cap-tured or objectives seized. At the same time, the experience in Panama yielded some interestinglessons about low intensity conflict, including lessons in mobility and patrolling that an earliergeneration of Marines who served in Central America would have understood.

To research and preserve the story of Marines in Panama, the History and MuseumsDivision deployed Benis M. Frank in the spring of 1991. Mr. Frank, who was then head of theOral History Section and is now Chief Historian in the division, walked the ground and inter-viewed Marines who participated in the operation. After his return to the United States, he con-ducted further interviews and supervised the collection of Marine Forces Panama records.

Once Mr. Frank had fulfilled the collection phase, a member of Mobilization TrainingUnit (Historical) DC-7, which supports the History and Museums Division, Lieutenant ColonelNicholas E. Reynolds, USMCR, assumed responsibility for the project, and completed the history.Lieutenant Colonel Reynolds joined the Marine Corps in 1975 after receiving a doctorate in his-tory from Oxford University, where he wrote a book on the German Army. Following active dutywith 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, he held a variety of reserve billets, including that of company com-mander at the Basic School during and after the Persian Gulf War.

In the pursuit of accuracy and objectivity, the History and Museums Division welcomescomments on this publication from interested individuals and activities.

MICHAEL F MONIGANColonel, U.S. Marine Corps

Acting Director of Marine Corps History and Museums

111

Foreword

The history of Marines in Panama from 1988 to 1990, the years bracketing Operatio n

Just Cause, does not involve a great many Marines, and Marines made up only a small percent -

age of the forces that went into battle during the operation itself in December 1989 . But for a

period of more than two years, the Marines in Panama were literally in foxholes on the fron tlines . For the individual Marine, going to Panama meant going in harm's way. Although mostplanners thought of Panama in terms of low intensity conflict, the personal experience for many

Marines was very intense, and tested their courage, endurance, and professionalism .

One measure of the intensity of just Cause lies in the fact that the contribution to th e

success of the operation by Marine Forces Panama was out of proportion to its size—that is ,

greater by far than for most other units of comparable size, measured in terms of prisoners cap-

tured or objectives seized. At the same time, the experience in Panama yielded some interestin g

lessons about low intensity conflict, including lessons in mobility and patrolling that an earlie r

generation of Marines who served in Central America would have understood .To research and preserve the story of Marines in Panama, the History and Museum s

Division deployed Benis M . Frank in the spring of 1991 . Mr. Frank, who was then head of the

Oral History Section and is now Chief Historian in the division, walked the ground and inter -viewed Marines who participated in the operation . After his return to the United States, he con-ducted further interviews and supervised the collection of Marine Forces Panama records .

Once Mr. Frank had fulfilled the collection phase, a member of Mobilization Training

Unit (Historical) DC-7, which supports the History and Museums Division, Lieutenant Colone l

Nicholas E . Reynolds, USMCR, assumed responsibility for the project, and completed the history .

Lieutenant Colonel Reynolds joined the Marine Corps in 1975 after receiving a doctorate in his-tory from Oxford University, where he wrote a book on the German Army. Following active duty

with 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, he held a variety of reserve billets, including that of company com -

mander at the Basic School during and after the Persian Gulf War .

In the pursuit of accuracy and objectivity, the History and Museums Division welcome s

comments on this publication from interested individuals and activities .

MICHAEL E MONIGA NColonel, U .S . Marine Corp s

Acting Director of Marine Corps History and Museum s

iii

Preface

This story is about the Marines who served in Panama around the time of Operation JustCause. Since the Marine forces comprised only a fraction of the troops in Panama, their contri-bution has been overlooked in some other histories. This is especially true of the Marines whoserved in Panama before and after the operation itself. Nevertheless, they faced, and met, a veryreal set of challenges of their own, and wrote one of the first chapters in the Marine Corps' his-tory of operations other than war since the fall of the Berlin Wall. The Marines who patrolledthe jungles of the Canal Zone in the period before Just Cause, in what was neither peace norwar, broke new ground. So did the young officers and NCOs who, for all intents and purposes,took over the reins of municipal government after the operation.

Since Benis M. Frank, the Chief Historian in the History and Museums Division, had done athorough job of interviewing the participants and collecting documents, both in the field andfrom sources in Washington, my job was relatively easy. I was able to rely almost exclusively onwhat is now the Marine Corps Historical Center's collection on Panama, including transcripts ofMr. Frank's interviews, as well as a variety of plans, operations, and reports. I also consulted anumber of command chronologies and secondary sources, and corresponded with a few of thePanama Marines.

Throughout, I was able to rely on the support and advice of many members of the staff of theHistory and Museums Division. Both the Director, Brigadier General Edwin H. Simmons, and Mr.Frank himself were kind enough to read the manuscript and give me the feedback I needed.Similarly, members of other sections provided valuable assistance: Danny J. Crawford, head ofthe Reference Section; Joyce M. Conyers of the Archives Section; Evelyn A. Englander, the librar-ian;JohnT Dyer, the art curator; and Charles R. Smith of the History Writing Unit, who edited thefinal manuscript. The former Division Deputy Director, Colonel William J. Davis, gave new mean-ing to the term "brother officer." I am grateful to him and all the other Marines who helped bringthe project to completion. Nevertheless, I alone am responsible for the opinions expressed, andany errors that may appear in the text.

NICHOLAS E. REYNOLDSLieutenant Colonel

U. S. Marine Corps Reserve

V

Preface

This story is about the Marines who served in Panama around the time of Operation Jus t

Cause . Since the Marine forces comprised only a fraction of the troops in Panama, their contri-bution has been overlooked in some other histories . This is especially true of the Marines wh oserved in Panama before and after the operation itself . Nevertheless, they faced, and met, a ver yreal set of challenges of their own, and wrote one of the first chapters in the Marine Corps' his-

tory of operations other than war since the fall of the Berlin Wall . The Marines who patrolled

the jungles of the Canal Zone in the period before Just Cause, in what was neither peace no r

war, broke new ground. So did the young officers and NCOs who, for all intents and purposes ,

took over the reins of municipal government after the operation .

Since Benis M . Frank, the Chief Historian in the History and Museums Division, had done a

thorough job of interviewing the participants and collecting documents, both in the field an d

from sources in Washington, my job was relatively easy. I was able to rely almost exclusively on

what is now the Marine Corps Historical Center's collection on Panama, including transcripts of

Mr. Frank's interviews, as well as a variety of plans, operations, and reports . I also consulted anumber of command chronologies and secondary sources, and corresponded with a few of th e

Panama Marines .Throughout, I was able to rely on the support and advice of many members of the staff of th e

History and Museums Division . Both the Director, Brigadier General Edwin H . Simmons, and Mr.

Frank himself were kind enough to read the manuscript and give me the feedback I needed .

Similarly, members of other sections provided valuable assistance: Danny J. Crawford, head o f

the Reference Section; Joyce M. Conyers of the Archives Section; Evelyn A. Englander, the librar-

ian; John T. Dyer, the art curator; and Charles R . Smith of the History Writing Unit, who edited th e

final manuscript . The former Division Deputy Director, Colonel William J . Davis, gave new mean-

ing to the term "brother officer." I am grateful to him and all the other Marines who helped bring

the project to completion . Nevertheless, I alone am responsible for the opinions expressed, and

any errors that may appear in the text .

NICHOLAS E . REYNOLDS

Lieutenant Colone l

U . S . Marine Corps Reserve

v

Table of Contents

Foreword .Preface V

Table of Contents Vii

First Reinforcements 2

First Firefights 6

Recovery and Consolidation 10

Neither War Nor Peace 10

The Evolution of Training 12

The New Year 14

The October Coup and Its Aftermath 16

Setting the Stage for Just Cause 18

Combat 22

La Chorrera 26

PDF Prisoners 26

More New Responsibilities 30

Christmas Eve 32

Christmas Day and After 32

Marine Reinforcements 32

Operation Promote Liberty 35

Notes 39

Appendix A Troop List 43

Appendix B Command and Staff, Marine Forces Panama 44

Appendix C Chronology 46

Appendix D Unit Commendation 48

Index 49

vii

Table of Contents

Foreword . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Preface v

Table of Contents vi i

First Reinforcements 2

First Firefights 6

Recovery and Consolidation 1 0

Neither War Nor Peace 1 0

The Evolution of Training 1 2

The New Year 1 4

The October Coup and Its Aftermath 1 6

Setting the Stage for Just Cause 1 8

Combat 2 2

La Chorrera 26

PDF Prisoners 26

More New Responsibilities 30

Christmas Eve 3 2

Christmas Day and After 3 2

Marine Reinforcements 3 2

Operation Promote Liberty 3 5

Notes 39

Appendix A Troop List 4 3

Appendix B Command and Staff, Marine Forces Panama 44

Appendix C Chronology 46

Appendix D Unit Commendation 48

Index 49

vii

¶

N0

0d)

0

it

1'I. 41

2

0"tp

C

1t

a)

z

C

Cl)

U

0U

U

a-

C

zCi')

T \ It1 (I

I

2- __/_ C)-I -'—.

02ç

I.

C

IU

U —V a Itflu•

£e !b 1 9C(5 flCCEgEC 01 I -(5 ;jj &a.

I 00I

Just Cause: Marine Operations in Panama1988-1990

First Reinforcements — First Firefight — Recovery and Consolidation — Neither War Nor Peace —The Evolution of Training — The New Year — The October Coup and its Aftermath — Setting theStage for Just Cause — Combat — La Chorrera — PDF Prisoners — More New Responsibilities —

Christmas Eve — Christmas Day and After — Marine Reinforcements — Operation Promote Liberty

Marines first came to Panama in 1856 to protectfortune hunters on their way to California acrossthe Isthmus, and returned a number of times forbrief periods, typically to restore law and order,between 1856 and 1900. When Panama secededfrom Colombia in 1903, in large part to make itpossible for the United States to acquire the rightsfor a canal under favorable terms, the Marine Corpslanded forces under Major John A. Lejeune to guar-antee Panamanian independence. Lejeune wasone of the first to realize that the Marines hadcome to Panama to stay, and, in 1904, his troops setup a semi-permanent barracks near Panama City.Until 1911, their primary mission was to safeguardthe canal that was under construction.'

By October 1923, a permanent Marine Barracksin Panama was established at the U.S. NavalSubmarine Base, Coco Solo. Over the followingdecades, Marine forces in Panama went throughperiods of expansion and contraction, reaching apeak of 36 officers, 3 warrant officers, and 1,571enlisted men in February 1945. They also wentthrough a number of redesignations and reloca-tions. In 1943, Marines in Panama were consoli-dated under Marine Barracks, Fifteenth NavalDistrict, which was renamed Marine Barracks,Rodman, Canal Zone, in 1976. In August 1987, theofficial title was changed to Marine Corps SecurityForce (MCSF) Company, Panama. Nevertheless, thestanding complement of approximately five offi-cers and 125 Marines remained at U.S. NavalStation Panama Canal, also known as RodmanNaval Station, which was located on the westernshore of the Canal near the Pacific Ocean exit.2

The title suggested the mission. By now, the pri-mary mission of the Marines in Panama was to pro-tect local naval installations, while that of U.S.Army units in the Canal Zone was to protect theCanal itself. In 1988, Army units operated underthe umbrella of U.S. Army South (USArSo), whichwas in turn a component of Southern Command(SouthCom). Both commands had their headquar-ters in Panama.

Over the years since 1903, relations with

1

Panama, which lay on either side of the American-controlled Canal Zone, were not always amiable.Due to the location of the Canal and its control bya foreign power, Panamanian interests clashed withthose of the United States from time to time.However, the signing of the Panama Canal Treaty in1977, which provided for complete Panamaniancontrol of the Canal by the year 2000, appeared toguarantee future cooperation between the twocountries.

The prospects for good relations, however,dimmed when General Omar Torrijos, thePanamanian leader who negotiated and signed thetreaty, died in a plane crash in 1981. His deathopened the way for a troublesome successor,General Manuel Antonio Noriega, who contrived tocontrol the nation through figurehead politiciansfrom his position as head of the country's armedforces. In 1983, Noriega became head of theNational Guard, which he soon combined with theAir Force and Navy to create the PanamanianDefense Forces (PDF).

By 1988, the PDF was as much a social and polit-ical system as a military force. It was a conglomer-ate of police, military, and paramilitary organiza-tions with a total strength in the neighborhood of15,000. However, it could only field some 3,000 to3,500 combat troops, largely trained and equippedby the U.S.Army. On the ground, the PDF had twobattalions in each of the country's 13 militaryzones, in addition to 10 independent companies, acavalry squadron, and a handful of special forces.The PDF's air arm had roughly 50 aircraft, while itsnavy could deploy 12 small vessels. Complement-ing Panamanian Defense Forces were the so-called"Dignity Battalions." Supposedly created tocounter American aggression, the Dignity Battal-ions were little more than formations of laborers,many of whom were unemployed, with an overlayof military discipline. There were 14 such battal-ions, each of which could deploy some 200 to 250members.

Although Noriega had a history of cooperatingwith American intelligence agencies, his involve-

Just Cause : Marine Operations in Panam a1988-1990

First Reinforcements — First Firefight — Recovery and Consolidation — Neither War Nor Peace —The Evolution of Training — The New Year — The October Coup and its Aftermath — Setting th e

Stage for Just Cause — Combat — La Chorrera — PDF Prisoners — More New Responsibilities —Christmas Eve — Christmas Day and After — Marine Reinforcements — Operation Promote Liberty

Marines first came to Panama in 1856 to protectfortune hunters on their way to California acros sthe Isthmus, and returned a number of times forbrief periods, typically to restore law and order ,between 1856 and 1900 . When Panama secededfrom Colombia in 1903, in large part to make i tpossible for the United States to acquire the rightsfor a canal under favorable terms, the Marine Corp slanded forces under Major John A . Lejeune to guar-antee Panamanian independence. Lejeune wasone of the first to realize that the Marines ha dcome to Panama to stay, and, in 1904, his troops se tup a semi-permanent barracks near Panama City .Until 1911, their primary mission was to safeguardthe canal that was under construction . '

By October 1923, a permanent Marine Barracksin Panama was established at the U.S . NavalSubmarine Base, Coco Solo . Over the followingdecades, Marine forces in Panama went throug hperiods of expansion and contraction, reaching apeak of 36 officers, 3 warrant officers, and 1,57 1enlisted men in February 1945. They also wentthrough a number of redesignations and reloca-tions . In 1943, Marines in Panama were consoli-dated under Marine Barracks, Fifteenth Nava lDistrict, which was renamed Marine Barracks ,Rodman, Canal Zone, in 1976. In August 1987, theofficial title was changed to Marine Corps Securit yForce (MCSF) Company, Panama . Nevertheless, thestanding complement of approximately five offi-cers and 125 Marines remained at U .S . NavalStation Panama Canal, also known as RodmanNaval Station, which was located on the westernshore of the Canal near the Pacific Ocean exit . '

The title suggested the mission . By now, the pri-mary mission of the Marines in Panama was to pro-tect local naval installations, while that of U.S .Army units in the Canal Zone was to protect theCanal itself. In 1988, Army units operated underthe umbrella of U .S . Army South (USArSo), whichwas in turn a component of Southern Command(SouthCom) . Both commands had their headquar-ters in Panama .

Over the years since 1903, relations with

Panama, which lay on either side of the American-controlled Canal Zone, were not always amiable .Due to the location of the Canal and its control bya foreign power, Panamanian interests clashed withthose of the United States from time to time .However, the signing of the Panama Canal Treaty in1977, which provided for complete Panamaniancontrol of the Canal by the year 2000, appeared toguarantee future cooperation between the twocountries .

The prospects for good relations, however ,dimmed when General Omar Torrijos, thePanamanian leader who negotiated and signed th etreaty, died in a plane crash in 1981 . His death

opened the way for a troublesome successor,

General Manuel Antonio Noriega, who contrived tocontrol the nation through figurehead politiciansfrom his position as head of the country's arme dforces . In 1983, Noriega became head of th eNational Guard, which he soon combined with theAir Force and Navy to create the PanamanianDefense Forces (PDF) .

By 1988, the PDF was as much a social and polit-ical system as a military force . It was a conglomer-ate of police, military, and paramilitary organiza-tions with a total strength in the neighborhood of15,000. However, it could only field some 3,000 t o3,500 combat troops, largely trained and equippe dby the U .S .Army. On the ground, the PDF had tw obattalions in each of the country's 13 militar yzones, in addition to 10 independent companies, acavalry squadron, and a handful of special forces .The PDF's air arm had roughly 50 aircraft, while it snavy could deploy 12 small vessels . Complement-ing Panamanian Defense Forces were the so-called"Dignity Battalions ." Supposedly created tocounter American aggression, the Dignity Battal-ions were little more than formations of laborers ,many of whom were unemployed, with an overlayof military discipline . There were 14 such battal-ions, each of which could deploy some 200 to 25 0members .

Although Noriega had a history of cooperatin gwith American intelligence agencies, his involve-

1

Canal Zone.ment in the drug trade eventually made it impossi-ble for the U.S. Government to continue to workwith him. Relations between the two countriesworsened markedly when, in February 1988, twoFlorida federal grand juries indicted him oncharges of racketeering and trafficking in nar-cotics. Due in part to the indictments, PanamanianPresident Eric Arturo Delvalle attempted to deposeNoriega, but without success. Instead Noriegaengineered Delvalle's dismissal. The result was fur-ther civil disorder and both implicit and explicitthreats to American lives and property, includingincursions into U.S. Navy installations.

First Reinforcements

The United States reacted to the heightened ten-sions first by updating contingency plans forPanama and then by sending reinforcements to theCanal Zone. The plans included provisions for aMarine Expeditionary Brigade to deploy to Panamaas part of Operation Elaborate Maze. But the

Pentagon was not ready for Elaborate Maze, and thefirst contingent of Marine reinforcements was agreat deal smaller, intended only to strengthenMarine security forces. The initial contingent wasa platoon from Fleet Anti-Terrorist Security Team(FAST) Company, Marine Corps Security ForceBattalion, Atlantic, based in Norfolk, Virginia. Akind of military SWAT team, the FAST platoon wastrained in close-quarter battle techniques. Arrivingin Panama on 14 March, the platoon was placedunder the operational control of the MCSE

Major Eddie A. Keith, the security forces com-manding officer, decided to use the platoon to pro-tect the Naval Stations Arraijan Tank Farm (ATF),where fuel was stored in 37 underground tanks foruse by all American forces in Panama. The tankfarm covered approximately two square kilome-ters of rolling grassland, apparently designed toresemble a golf course from the air, but was sur-rounded by dense jungle, which provided excel-lent avenues of approach both to the storage tanksand to Howard Air Force Base to the south. In the

Watercolor by Anthony F. Stadler

Referred to as the "Big House," the headquarters building of Marine Barracks,Panama, was built in 1965. Although headquartered at Rodman Naval Station,the barracks included a number of separate detachments scattered throughout the

2

t

1'

______

'a.

1 'i& 4A..jr 'i- - 't4A'tIF Tir •%t

____

4t:t , -k yM4 E' -t

Watercolor by Anthony F. Stadler

Referred to as the "Big House," the headquarters building of Marine Barracks,Panama, was built in 1965 . Although headquartered at Rodman Naval Station,the barracks included a number of separate detachments scattered throughout theCanal Zone.

ment in the drug trade eventually made it impossi-ble for the U.S . Government to continue to workwith him. Relations between the two countrie sworsened markedly when, in February 1988, twoFlorida federal grand juries indicted him o ncharges of racketeering and trafficking in nar-cotics . Due in part to the indictments, Panamania nPresident Eric Arturo Delvalle attempted to depos eNoriega, but without success . Instead Norieg aengineered Delvalle's dismissal . The result was fur-ther civil disorder and both implicit and explici tthreats to American lives and property, includin gincursions into U .S . Navy installations .

First Reinforcements

The United States reacted to the heightened ten-sions first by updating contingency plans fo rPanama and then by sending reinforcements to theCanal Zone . The plans included provisions for aMarine Expeditionary Brigade to deploy to Panam aas part of Operation Elaborate Maze . But the

Pentagon was not ready for Elaborate Maze, and th efirst contingent of Marine reinforcements was agreat deal smaller, intended only to strengthe nMarine security forces . The initial contingent wasa platoon from Fleet Anti-Terrorist Security Team(FAST) Company, Marine Corps Security Forc eBattalion, Atlantic, based in Norfolk, Virginia . Akind of military SWAT team, the FAST platoon wa strained in close-quarter battle techniques . Arrivingin Panama on 14 March, the platoon was place dunder the operational control of the MCS E

Major Eddie A. Keith, the security force's com-manding officer, decided to use the platoon to pro-tect the Naval Station's Arraijan Tank Farm (ATF) ,where fuel was stored in 37 underground tanks foruse by all American forces in Panama. The tan kfarm covered approximately two square kilome-ters of rolling grassland, apparently designed toresemble a golf course from the air, but was sur-rounded by dense jungle, which provided excel-lent avenues of approach both to the storage tank sand to Howard Air Force Base to the south . In the

2

3

[! kt 4t72Y. 1"2r

3

jungle, visibility was limited to a few feet, even byday, and movement was slow and exhausting. Therule of thumb was that a patrol could cover nomore than 500 meters in one hour. The ATF wasbounded on the north by the Naval AmmunitionDepot, or ammunition supply point (ASP), whichwas fenced. But for the most part the tank farmwas not fenced as it bordered the Pan-American, orThatcher, Highway, the best high-speed avenue ofapproach in the country Under the circumstances,it was nearly impossible for Marine security forces,with their limited resources, to guard the tank farmproperly, let alone both the fuel and ammunitionstorage facilities.

Soon after its deployment to the Arraijan TankFarm, the platoon reported the presence of intrud-ers, usually at night. The Marines described theintruders as individuals wearing black camouflageuniforms, carrying weapons and night visiondevices. Daily patrols found freshly dug fightingholes. When the security force reported its find-

ings through the chain of command, the standardresponse was that Panamanian Defense Forces didnot have night vision devices and that U.S. Armyunits had dug the holes during training exercises.However, the Marines conducted further research,and discovered that no Army units had trained inthe vicinity in recent months, and that the Armyhad sold night vision devices to Panama during thepast decade.3

While the FAST platoon patrolled the ATF, thepolitical climate continued to worsen and the 6thMarine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB) staff at CampLejeune, North Carolina, prepared for possibledeployment to Panama in accordance with contin-gency plan Elaborate Maze. Although SouthernCommand showed little, if any, enthusiasm for fur-ther Marine reinforcements, 6th MEB plannersassumed an all or nothing" approach. Should rein-forcements be ordered, the brigade was preparedto deploy most of its strength, to include twoinfantry battalions, a reinforced helicopter

Marines patrol up a small stream in the jungle surrounding the Arrajan TankFarm. The terrain provided intruders with good cover and avenues of approachboth to the fuel storage facility and Howard Air Force Base.

4

4 I, ' 'I,,

ssr,i4',iç., I,, 4

-; i :'(t*.•"Wi'-t c'\' _,I\et 4)l —

'-0

-, jr2T •4t \ \

___

ttt*4

__

I -— -r - ,ar-

I S I -

____

S. '_ •--a- :_' - t':t'0 "_a . -....r'

jungle, visibility was limited to a few feet, even byday, and movement was slow and exhausting . Therule of thumb was that a patrol could cover nomore than 500 meters in one hour. The ATF wa sbounded on the north by the Naval Ammunition

Depot, or ammunition supply point (ASP), whic hwas fenced . But for the most part the tank farmwas not fenced as it bordered the Pan-American, o r

Thatcher, Highway, the best high-speed avenue ofapproach in the country. Under the circumstances ,it was nearly impossible for Marine security forces ,with their limited resources, to guard the tank far mproperly, let alone both the fuel and ammunitionstorage facilities .

Soon after its deployment to the Arraijan TankFarm, the platoon reported the presence of intrud-ers, usually at night . The Marines described theintruders as individuals wearing black camouflageuniforms, carrying weapons and night visiondevices . Daily patrols found freshly dug fightingholes . When the security force reported its find-

ings through the chain of command, the standar d

response was that Panamanian Defense Forces di d

not have night vision devices and that U .S . Army

units had dug the holes during training exercises .However, the Marines conducted further research ,and discovered that no Army units had trained i n

the vicinity in recent months, and that the Armyhad sold night vision devices to Panama during the

past decade . 'While the FAST platoon patrolled the ATF, the

political climate continued to worsen and the 6t h

Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB) staff at CampLejeune, North Carolina, prepared for possibledeployment to Panama in accordance with contin-gency plan Elaborate Maze . Although Souther nCommand showed little, if any, enthusiasm for fur -ther Marine reinforcements, 6th MEB plannersassumed an all or nothing" approach. Should rein-forcements be ordered, the brigade was preparedto deploy most of its strength, to include twoinfantry battalions, a reinforced helicopte r

Marines patrol up a small stream in the jungle surrounding the Arraijan TankFarm. The terrain provided intruders with good cover and avenues of approac hboth to the fuel storage facility and Howard Air Force Base.

4

Watercolor byAnttsony F Stadler

A panoramic view of Rodman Naval Station reveals its situation on the northernshore of Balboa Harbo from where it controlled the Pacific entrance to the Canal.

squadron, and a detachment of OV-10 Bronco air-craft. On 31 March, Fleet Marine Force, Atlantic(FMFLant), ordered the MEB to deploy in accor-dance with a Joint Chiefs of Staff directive. The fol-lowing day, an advance party of three brigade staffofficers flew to Panama to coordinate the move-ment of forces.4

On 1 April, the Pentagon formally announcedthat 1,300 additional U.S. troops would be sent toPanama, including 300 Marines, once again simplyto enhance security in view of the growing tensionand unrest. Since the full strength of the brigadewould not be needed, FMFLant, nevertheless,decided that the 300 Marines would deploy as aprovisional Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF)built around a reinforced rifle company under theadministrative control of 6th MEB. The idea was forthe MAGTF to serve as cadre for the eventualdeployment of the entire brigade. For that reason,the MEB supplied the command element, while 2dMarine Division provided a rifle company and 2dForce Service Support Group, a group of 40Marines, to form Brigade Service Support Group 6

5

(BSSG-6) SouthCom's commander, GeneralFrederick F Woerner, USA, decided that the pres-ence of a large number of Army and Air Force air-craft in Panama precluded the need for any Marineair assets. The MAGTF, therefore, was not a true'air-ground" task force, a fact which some Marinecommanders, wholeheartedly committed to theMAGTF concept, regretted despite the fact that theMarines in Panama were more of a security forcethan a maneuver element.5

Marine reinforcements began flowing intoPanama on 6 April, under the command of thebrigade's chief of staff, Colonel William J. Conley,the senior officer present. Colonel Conley arrivedin Panama to facilitate the movement of thebrigade, not to command. However, sinceSouthern Command did not see the need for addi-tional Marine forces beyond the reinforced riflecompany, and since the Pentagon decided to stopwell short of executing Elaborate Maze, the MEBcommander never deployed, and Colonel Conleyassumed command.

The provisional MAGTF initially came under the

4

-a

yWatercolor byAnthony F. Stadler

A panoramic view of Rodman Naval Station reveals its situation on the northernshore of Balboa Harbor, from where it controlled the Pacific entrance to the Canal.

squadron, and a detachment of OV-10 Bronco air -craft . On 31 March, Fleet Marine Force, Atlantic

(FMFLant), ordered the MEB to deploy in accor-dance with a Joint Chiefs of Staff directive . The fol-lowing day, an advance party of three brigade staff

officers flew to Panama to coordinate the move-ment of forces . '

On 1 April, the Pentagon formally announcedthat 1,300 additional U .S . troops would be sent toPanama, including 300 Marines, once again simplyto enhance security in view of the growing tensio n

and unrest . Since the full strength of the brigadewould not be needed, FMFLant, nevertheless ,decided that the 300 Marines would deploy as aprovisional Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF )built around a reinforced rifle company under th eadministrative control of 6th MEB . The idea was forthe MAGTF to serve as cadre for the eventua ldeployment of the entire brigade . For that reason ,the MEB supplied the command element, while 2 dMarine Division provided a rifle company and 2 dForce Service Support Group, a group of 4 0Marines, to form Brigade Service Support Group 6

(BSSG-6) SouthCom's commander, Genera l

Frederick F. Woerner, USA, decided that the pres-ence of a large number of Army and Air Force air-

craft in Panama precluded the need for any Marin e

air assets . The MAGTF, therefore, was not a true

"air-ground" task force, a fact which some Marin ecommanders, wholeheartedly committed to theMAGTF concept, regretted despite the fact that theMarines in Panama were more of a security forc ethan a maneuver element. '

Marine reinforcements began flowing int oPanama on 6 April, under the command of thebrigade's chief of staff, Colonel William J. Conley,the senior officer present . Colonel Conley arrive d

in Panama to facilitate the movement of th e

brigade, not to command. However, since

Southern Command did not see the need for addi-tional Marine forces beyond the reinforced rifle

company, and since the Pentagon decided to stop

well short of executing Elaborate Maze, the ME B

commander never deployed, and Colonel Conley

assumed command .The provisional MAGTF initially came under the

5

operational control of U.S. Navy South (USNavS0),and the rifle company, Company I, 3d Battalion, 4thMarines, began to operate in direct support of thecommander of Rodman Naval Station, where theMAGTF planted its flag. Soon thereafter, an agree-ment was reached between Colonel Conley andRear Admiral Jerry G. Gnecknow, USN, USNavSocommander, that he, Colonel Conley, would assumecontrol of all Marine ground forces in the event ofan emergency. The understanding formed the basisfor the eventual establishment of Marine ForcesPanama (MarForPM), whereby Colonel Conleyassumed operational control of all Marine forces incountry. Neither the agreement betweenGnecknow and Conley nor the mission ofCompany I changed when, on 9 April, operationalcontrol of Marine Forces Panama shifted from U.S.Navy South to the newly established Joint TaskForce Panama UTF Panama).6

First Firefights

Company I was chosen to deploy to Panama inlarge part because it was available and because itwas on air alert. The Company was well trained,having recently cycled through a combined armsexercise at Twentynine Palms, California; coldweather training a Bridgeport, California, and FortMcCoy,Wisconsin; and jungle training on Okinawa,as well as a Marine Corps Combat ReadinessEvaluation. Most recently, its parent battalion hadrehearsed for the Panama contingency, practicingmissions such as defending a fuel farm or antennasite and dealing with intruders. Much of the train-ing was on company commander's time, forcingcommanders to rely on their own judgment andgiving them the opportunity to mold their compa-flies into cohesive, professional forces.7

Before deploying, the company was reinforcedby an 81mm mortar section of two mortars, a sur-veillance and target acquisition (STA) platoon, acounter-intelligence team, and a squad of engi-neers. Arriving in country, the Marines made them-selves as comfortable as possible in the Rodmangymnasium, while their commander, CaptainJoseph P Valore, conferred with Major Keith, thesecurity force commander. Since it appeared thatthe company would deploy to the tank farm,Valorethen conducted a reconnaissance of the area anddebriefed members of the FAST platoon. On 7April, Colonel Conley gave Captain Valore a rough

6

operations order for the defense of the tank farm,as well as other nearby installations.8

Captain Valore used the information he obtainedto analyze the situation and the mission. He real-ized that he would need to plan carefully, since hismission was ambitious for a reinforced rifle com-pany, given the terrain and the threat. He conclud-ed that the best way to cover the terrain and tominimize the threat to his Marines was to usepatrolling techniques, as opposed to manning fixedpositions. He knew that the "old" way, oncedescribed as "one man standing post in a littleshack underneath a light surrounded by jungle,"was a thing of the past.9 Initially, he planned to usea system of patrol bases, whose locations wouldchange at regular intervals. However, he soondecided that, rather than waste time and effortmoving command posts and communicationsequipment, it would be more efficient to find andimprove one set of good positions. Accordingly,Captain Valore divided the tank farm into twozones, and assigned each zone to one platoon as atactical area of responsibility. '°

Before deploying his Marines, Valore had toaddress a critical issue—weapons policy. Securityforce policy prohibited Marines from having around in the chamber under routine conditions.Concerned for the safety of his Marines, and deter-mined to demonstrate his trust in their judgment,Valore raised the issue with Colonel Conley.Conley agreed to permit Valore's Marines to patrolwith a loaded magazine in their weapons and around in the chamber. Valore's policy made sense.Under then-current rules of engagement, Marineswere permitted to return fire, but if they did nothave a magazine in the weapon and a round in thechamber, they might not live to return fire.

The Marines' weapons policy was a highlycharged issue. Although Valore focussed more onthe immediate threat than on the past, a number ofmore senior Marine officers, including LieutenantGeneral Ernest T Cook, Commanding General,FMFLant, remembered the 1983 tragedy at MarineAmphibious Unit Headquarters in Beirut, Lebanon.Then, a restrictive weapons policy was one of thecontributing factors which made it impossible forsentries to stop the truck bomb which took thelives of 241 Marines, sailors, and soldiers.Determined not to get "stung" twice, Cook and hisstaff endorsed more aggressive and forward-lean-ing policies as that of Captain Valore, both in the

operational control of U.S . Navy . South (USNavSo) ,and the rifle company, Company I, 3d Battalion, 4t h

Marines, began to operate in direct support of the

commander of Rodman Naval Station, where theMAGTF planted its flag . Soon thereafter, an agree-ment was reached between Colonel Conley an d

Rear Admiral Jerry G. Gnecknow, USN, USNavS ocommander, that he, Colonel Conley, would assumecontrol of all Marine ground forces in the event o fan emergency. The understanding formed the basisfor the eventual establishment of Marine ForcesPanama (MarForPM), whereby Colonel Conle y

assumed operational control of all Marine forces i ncountry. Neither the agreement betwee nGnecknow and Conley nor the mission o fCompany I changed when, on 9 April, operationa lcontrol of Marine Forces Panama shifted from U .S .Navy South to the newly established Joint Tas kForce Panama (jTF Panama) .

First Firefights

Company I was chosen to deploy to Panama inlarge part because it was available and because i twas on air alert . The Company was well trained ,

having recently cycled through a combined arm sexercise at Twentynine Palms, California ; coldweather training at Bridgeport, California, and For tMcCoy,Wisconsin ; and jungle training on Okinawa ,as well as a Marine Corps Combat ReadinessEvaluation . Most recently, its parent battalion hadrehearsed for the Panama contingency, practicingmissions such as defending a fuel farm or antennasite and dealing with intruders . Much of the train-ing was on company commander's time, forcingcommanders to rely on their own judgment an dgiving them the opportunity to mold their compa-

nies into cohesive, professional forces . 'Before deploying, the company was reinforce d

by an 81mm mortar section of two mortars, a sur-veillance and target acquisition (STA) platoon, acounter-intelligence team, and a squad of engi-neers . Arriving in country, the Marines made them-selves as comfortable as possible in the Rodma ngymnasium, while their commander, CaptainJoseph P. Valore, conferred with Major Keith, thesecurity force commander. Since it appeared thatthe company would deploy to the tank farm,Valorethen conducted a reconnaissance of the area an ddebriefed members of the FAST platoon. On 7April, Colonel Conley gave Captain Valore a rough

operations order for the defense of the tank farm,

as well as other nearby installations ."Captain Valore used the information he obtained

to analyze the situation and the mission . He real-

ized that he would need to plan carefully, since hi smission was ambitious for a reinforced rifle com-pany, given the terrain and the threat . He conclud-

ed that the best way to cover the terrain and tominimize the threat to his Marines was to us epatrolling techniques, as opposed to manning fixed

positions . He knew that the "old" way, onc edescribed as "one man standing post in a littleshack underneath a light surrounded by jungle, "

was a thing of the past . 9 Initially, he planned to usea system of patrol bases, whose locations wouldchange at regular intervals . However, he soondecided that, rather than waste time and effortmoving command posts and communications

equipment, it would be more efficient to find andimprove one set of good positions. Accordingly,Captain Valore divided the tank farm into twozones, and assigned each zone to one platoon as a

tactical area of responsibility. '°Before deploying his Marines, Valore had to

address a critical issue–weapons policy. Security

force policy prohibited Marines from having around in the chamber under routine conditions .Concerned for the safety of his Marines, and deter -mined to demonstrate his trust in their judgment ,Valore raised the issue with Colonel Conley.Conley agreed to permit Valore's Marines to patro lwith a loaded magazine in their weapons and around in the chamber. Valore's policy made sense .Under then-current rules of engagement, Marine swere permitted to return fire, but if they did no thave a magazine in the weapon and a round in th e

chamber, they might not live to return fire . "The Marines' weapons policy was a highly

charged issue . Although Valore focussed more onthe immediate threat than on the past, a number o fmore senior Marine officers, including Lieutenan tGeneral Ernest T Cook, Commanding General ,FMFLant, remembered the 1983 tragedy at Marin eAmphibious Unit Headquarters in Beirut, Lebanon .Then, a restrictive weapons policy was one of th econtributing factors which made it impossible fo rsentries to stop the truck bomb which took thelives of 241 Marines, sailors, and soldiers .Determined not to get "stung" twice, Cook and hi sstaff endorsed more aggressive and forward-lean-ing policies as that of Captain Valore, both in th e

6

field and around Marine offices and housing onRodman.'2

Southern Command viewed the policy differ-ently General Woerner was under orders fromWashington both to protect American interests andnot to exacerbate the situation. It was a delicateand difficult balance. At the same time, long-timemembers of the U.S. military community in Panamaargued that the Marines were over-reacting to thethreat and that their aggressiveness could provokea response in kind from the PDE Marine comman-ders defended their policy by pointing out thatthey occupied exposed positions in the jungle,where they faced a threat from intruders whichpredated their weapons policy. The Marines, theypointed out, were responding to an old threat, notcreating a new one.

In one form or another, the dispute continuedthroughout the existence of Marine ForcesPanama. Whatever the merits on either side of theargument, it was understandable that there wouldbe cultural differences between the Marines andthe other Southern Command troops. Unlike mostof their American counterparts in Panama, theMarines were combat troops on unaccompanied90-day tours, except for Colonel Conley and prin-cipal members of his staff, who were on 180-day

7

tours. As opposed to living in base housing andhaving the freedom of the city, the Marines workedlong hours, usually under field conditions, for up totwo weeks at a time. The two weeks of duty typi-cally were followed by a two-day rest period,which might include some base liberty but neverinvolved liberty off base, a precaution to preventincidents between Panamanian Defense Forces andindividual Marines.

Events soon transpired to test the assumptionsof the Marines' weapons policy. On 9 and lOApril,shortly after the two platoons from Company Irelieved the FAST platoon at the tank farm,unknown intruders began to probe their lines. Onthe night of 11 April, a squad-sized Marine patrol inthe vicinity of "K tank in the northeast sector ofthe farm made contact. The patrol split into twogroups in an attempt to trap the intruders. When aflare misfired, igniting with a pop" like a gunshot,one element opened fire with M-16 rifles, mistak-ing the flare for an intruder's weapon.Unfortunately, they fired in the direction of theother element, mortally wounding CorporalRicardo M. Villahermosa, the patrol leader.Villahermosa was evacuated to Gorgas ArmyCommunity Hospital, where he died in the earlymorning hours of 12 April.13

field and around Marine offices and housing o nRodman . ' Z

Southern Command viewed the policy differ-

ently. General Woerner was under orders from

Washington both to protect American interests an d

not to exacerbate the situation . It was a delicate

and difficult balance . At the same time, long-timemembers of the U .S . military community in Panam aargued that the Marines were over-reacting to thethreat and that their aggressiveness could provoke

a response in kind from the PDE Marine comman-ders defended their policy by pointing out thatthey occupied exposed positions in the jungle ,where they faced a threat from intruders whic hpredated their weapons policy. The Marines, theypointed out, were responding to an old threat, notcreating a new one .

In one form or another, the dispute continue dthroughout the existence of Marine Force sPanama. Whatever the merits on either side of th eargument, it was understandable that there wouldbe cultural differences between the Marines andthe other Southern Command troops. Unlike most

of their American counterparts in Panama, th eMarines were combat troops on unaccompanie d

90-day tours, except for Colonel Conley and prin-cipal members of his staff, who were on 180-day

tours. As opposed to living in base housing and

having the freedom of the city, the Marines worked

long hours, usually under field conditions, for up t otwo weeks at a time. The two weeks of duty typi-cally were followed by a two-day rest period ,which might include some base liberty but neverinvolved liberty off base, a precaution to preven tincidents between Panamanian Defense Forces an d

individual Marines .Events soon transpired to test the assumptions

of the Marines' weapons policy. On 9 and 10 April ,

shortly after the two platoons from Company Irelieved the FAST platoon at the tank farm ,unknown intruders began to probe their lines . Onthe night of 11 April, a squad-sized Marine patrol inthe vicinity of "K" tank in the northeast sector ofthe farm made contact . The patrol split into twogroups in an attempt to trap the intruders . When aflare misfired, igniting with a "pop" like a gunshot ,one element opened fire with M-16 rifles, mistak-ing the flare for an intruder's weapon.Unfortunately, they fired in the direction of theother element, mortally wounding Corpora lRicardo M. Villahermosa, the patrol leader.Villahermosa was evacuated to Gorgas ArmyCommunity Hospital, where he died in the earl y

morning hours of 12 April .' '

7

The incident renewed the debate over theweapons policy among Marine and Army groundcommanders. At a meeting on the 12th with theJoint Task Force commander, Major GeneralBernard Loefike, USA, whose primary duty wascommander of U.S. Army South, the only Marinepresent, Major Alfred F Clarkson of the MEB staff,vigorously defended the Marine policy, citing guid-ance from the Commandant of the Marine Corpsand adding his own view that it was morally wrongto send Marines in harm's way without fully loadedweapons. Colonel Conley fully supportedClarkson's position, and made certain that Marinecommanders had the authority they needed toimplement the right weapons policy for the con-ditions they faced.14

The average Marine rifleman, whose morale wasalready shaken by Villahermosa's death, had muchthe same worry-that he would now be orderedback into the jungle without a loaded weapon.Captain Valore put that worry to rest by visitingthe line platoons and telling his Marines that thepolicy had not changed. As he had in the past, hemade it clear that he had full confidence in theirjudgment and professionalism. Valore's actions didmuch to restore morale and re-energize the com-pany.15

At dusk on the 12th, U.S. Army remote battle-field sensors on loan to the Marines detectedmovement by approximately 40 persons whoappeared to be approaching the tank farm fromthe direction of the Pan-American Highway. Thesensor activation was confirmed by the detach-ment of surveillance and target acquisitionMarines from 3d Battalion, 4th Marines.* Thedetachment, in place at listening posts in the west-ern sector of the ATF approximately 700 metersfrom the company command post, reported byradio that they had seen and heard intruders. Aspecially-equipped Air Force AC-i 30 Specter orbit-ing the area also confirmed the sightings.'6

Captain Valore left his position in order to inves-tigate the reports, and spotted approximately 12intruders between the highway and the tank farm.At that point, he decided to begin consolidating hisforces in the center of the ATE Soon thereafter, his

*The Army's remote battlefield sensor system apparentlywas operated by a detachment of Sensor Control andManagement Platoon (SCAiMP) Marines from the 2d MarineDivision which deployed with Captain Valore's company.

8

Marines received and returned fire, aiming downthe line of tracers that came at them. The 13-mansurveillance 'detachment, still in position to thewest of the company, reported that the intruderswere probing their positions, and Sergeant MichaelA. Cooper, the noncommissioned officer in charge,immediately requested illumination.. Eighty-onemillimeter mortars near the company commandpost fired the mission. Putting the illumination togood use, Cooper reported that he could see thatthe intruders were armed and well-equipped, andthat they moved like professional soldiers. Whenthe intruders continued to advance despite theillumination rounds, he urgently called for the mor-tars to drop high-explosive rounds on pre-plottedtargets near his position. Knowing that Cooperwas a professional who would not overreact,Captain Valore authorized the fire missions, andthe mortars fired 16 high-explosive rounds in addi-tion to the 98 rounds of illumination they hadalready fired. He also authorized Cooper's Marinesto return fire. Valore could hear the results, heavyfiring, almost immediately.'7

A few minutes later, around 1930, the companyitself took fire from a ravine to its front. Valoredirected company First Sergeant Alexander J.Nevgloski to return fire with a Mark 19 chain gun,which then fired a total of 222 40mm rounds.Within minutes, the fire from the Mark 19 alongwith the fire from the mortars effectively sup-pressed the threat, and firing died down.'8

Sometime after 2200, General Loefike arrivedon scene, wearing civilian clothes and wanting toknow what happened. After being briefed byCaptain Valore, he ordered the company to ceasefire and not to reengage unless fired upon. He alsoordered the Marines to remain in place and to per-mit any intruders to leave the area. Loefike saidthat he was in touch with the PDF, whose com-manders had assured him that they did not haveany troops in the area. Captain Moises Cortizo, anEnglish-speaking PDF officer, stood next to GeneralLoefflce, and restated the Panamanian position.'9

After receiving General Loeffke's order, Valorepulled back Cooper's detachment from the west-ern sector of the tank farm while the rest of hisMarines held their positions. Using night visiondevices they watched as a number of the intrudersapparently received first aid, and saw others, eitherwounded or dead, being evacuated. Sensor activa-tions confirmed their sightings. There was further

The incident renewed the debate over theweapons policy among Marine and Army groun dcommanders . At a meeting on the 12th with theJoint Task Force commander, Major GeneralBernard Loeffke, USA, whose primary duty wa scommander of U.S . Army South, the only Marinepresent, Major Alfred F. Clarkson of the MEB staff,vigorously defended the Marine policy, citing guid-ance from the Commandant of the Marine Corp sand adding his own view that it was morally wron g

to send Marines in harm's way without fully loade dweapons . Colonel Conley fully supportedClarkson's position, and made certain that Marin ecommanders had the authority they needed toimplement the right weapons policy for the con-ditions they faced . 7 4

The average Marine rifleman, whose morale wa salready shaken by Villahermosa's death, had muchthe same worry-that he would now be orderedback into the jungle without a loaded weapon .Captain Valore put that worry to rest by visitin gthe line platoons and telling his Marines that th epolicy had not changed. As he had in the past, hemade it clear that he had full confidence in thei rjudgment and professionalism . Valore's actions didmuch to restore morale and re-energize the com-pany ' '

At dusk on the 12th, U.S . Army remote battle -field sensors on loan to the Marines detecte dmovement by approximately 40 persons wh oappeared to be approaching the tank farm fro mthe direction of the Pan-American Highway . Thesensor activation was confirmed by the detach-ment of surveillance and target acquisitionMarines from 3d Battalion, 4th Marines . * Thedetachment, in place at listening posts in the west -ern sector of the ATF approximately 700 meter sfrom the company command post, reported byradio that they had seen and heard intruders . Aspecially-equipped Air Force AC-130 Specter orbit-ing the area also confirmed the sightings . "

Captain Valore left his position in order to inves-tigate the reports, and spotted approximately 1 2intruders between the highway and the tank farm .At that point, he decided to begin consolidating hi sforces in the center of the ATE. Soon thereafter, hi s

*The Army's remote battlefield sensor system apparentl ywas operated by a detachment of Sensor Control andManagement Platoon (SCAMP) Marines from the 2d Marin eDivision which deployed with Captain Valore's company.

Marines received and returned fire, aiming down

the line of tracers that came at them. The 13-mansurveillance detachment, still in position to thewest of the company, reported that the intruder swere probing their positions, and Sergeant Michae l

A. Cooper, the noncommissioned officer in charge ,immediately requested illumination . . Eighty-on emillimeter mortars near the company comman dpost fired the mission . Putting the illumination t ogood use, Cooper reported that he could see tha t

the intruders were armed and well-equipped, an dthat they moved like professional soldiers . Whenthe intruders continued to advance despite theillumination rounds, he urgently called for the mor-tars to drop high-explosive rounds on pre-plotte dtargets near his position . Knowing that Coope rwas a professional who would not overreact ,Captain Valore authorized the fire missions, an dthe mortars fired 16 high-explosive rounds in addi-

tion to the 98 rounds of illumination they ha dalready fired . He also authorized Cooper's Marinesto return fire . Valore could hear the results, heavyfiring, almost immediately. "

A few minutes later, around 1930, the companyitself took fire from a ravine to its front . Valoredirected company First Sergeant Alexander J .Nevgloski to return fire with a Mark 19 chain gun ,which then fired a total of 222 40mm rounds .Within minutes, the fire from the Mark 19 along

with the fire from the mortars effectively sup-pressed the threat, and firing died down . '

Sometime after 2200, General Loeffke arrive don scene, wearing civilian clothes and wanting t oknow what happened. After being briefed byCaptain Valore, he ordered the company to ceas efire and not to reengage unless fired upon . He alsoordered the Marines to remain in place and to per-mit any intruders to leave the area . Loeffke saidthat he was in touch with the PDF, whose com-manders had assured him that they did not haveany troops in the area . Captain Moises Cortizo, a nEnglish-speaking PDF officer, stood next to Genera lLoeffke, and restated the Panamanian position . 1 9

After receiving General Loeffke's order, Valor epulled back Cooper's detachment from the west -ern sector of the tank farm while the rest of hi sMarines held their positions . Using night visio ndevices they watched as a number of the intruder sapparently received first aid, and saw others, eithe rwounded or dead, being evacuated . Sensor activa-tions confirmed their sightings . There was further

8

corroboration. Security force Marines, who hadmanned a roadblock on the highway to preventPanamanian reinforcements from reaching thetank farm, witnessed the evacpation of woundedby blacked-out ambulances.20* /

At dawn, teams of Marines Iwept the area, look-ing for evidence to confirm the presence of theintruders. They did not fmd much. There weresigns that bodies had been dragged through thearea, and there was debris such as fresh, foreign-made battle dressings, scraps of camouflage utilityuniforms, and chemical light sticks. But there wereneither bodies nor spent ammunition shells.However, Marines later learned that the automaticweapons carried by some Panamanian soldierswere equipped with brass-catchers.2'

During the next several days, Captain Valore andhis Marines were debriefed extensively by ColonelConley's staff, by Naval Investigative Serviceagents, and by Army intelligence specialists. Manyof these official visitors also walked the groundover which the fight had occurred, repeating ques-tions that had been asked by others. There waseven an order from U.S. Army South for theMarines who fought in the jungle that night to sub-mit to a urinalysis, which they did, with negativeresults.22

What the Marines told the debriefers was consis-tent, and detailed. Some of their testimony wasalso graphic. For example, when one of Cooper'sMarines described his experiences during the fire-fight, he began by telling the debriefer how he had"gone to ground," and tried to make himself invisi-ble. Nevertheless, one of the passing intrudersspotted him at a distance of 8 to 10 feet away Asthe intruder began to swing his weapon towardsthe Marine, the Marine shot him twice in the chestwith his M-16. Upon impact, the intruder fell backand hit the ground so hard that "his legs flopped inthe air."23

Even after the debriefings, doubts persisted.Some members of the joint task force staffacknowledged the threat, but wondered if theMarines had overreacted. More frustrating for theMarines were lingering questions about the facts.

*Valore remarked to another Marine officer that, just beforeGeneral Loeffke's arrival, he had ordered his reserve to flankthe intruders. This movement did not take place due toLoeffke's intervention. (Maj William J. Philbin intvw with author,23Jun94.)

9

Matters took a turn for the worse when SouthernCommand's Public Affairs Officer failed to rejectsuggestions that the Marines had fired at shadows.Noriega exploited the opportunity, using his pro-paganda machine to plant stories about drug abuseamong the Marines, implying that the events of 11and 12 April were drug-induced hallucinations.24

Marine Forces Panama overcame the challenge toits credibility and professionalism. Colonel Conleyand Captain Valore closed ranks behind theirMarines, who reciprocated in kind. On the night of13 April, when Captain Valore walked into one ofthe clubs at Rodman, all of the Marines presentcheered him. He later said that this was one of thehighlights of his career, and that he was moved bythe bonding and mutual trust among men whowere now combat veterans:

The [pre-combat] tension was there; it was released. I[had] gained their credibility. They knew I was going tostand behind them, whatever it took... They coulddepend on me to look out for them, [and] not play poli-tics or worry about other things... You have a mission toaccomplish: you've got to take care of your Marines.5*

Valore's Marines stood down from the tank farmfor a few days of rest and recreation at Rodman. Areinforced Army battalion took their place. On 14April, Army sentries guarding the ammunition sup-ply point challenged a small group of intruders,who responded with gunfire, and a patrol from the3d Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group, operatingwest of Howard Air Force Base engaged anothergroup of well-disciplined intruders. It was nowclear that the Marines were not the only Americansoldiers to encounter intruders and to defendthemselves.26

In the months that followed, there were occa-sional incidents, but nothing on the scale of the 12April firefight. In retrospect, the aggressive Marineresponse appeared to have had the desired effect;the Marines had recognized the threat andresponded accordingly. Information obtained fromPanamanian officers following Operation Just

*Marine Forces Panama officially reported that, despite thechallenge to Marine credibility, morale was excellent.Headquarters Marine Corps took note of Valore's andNevgloski's performance, awarding both the Bronze Star Medalwith Combat "V." Sergeant Cooper received the NavyCommendation Medal. All of the Marines involved were award-ed the combat action ribbon. (Maj Joseph P Valore ltr to author,Nov93)

corroboration . Security force Marines, who ha dmanned a roadblock on the highway to prevent

Panamanian reinforcements from reaching the

tank farm, witnessed the evacuation of wounde dby blacked-out ambulances.Z°*

r~!

At dawn, teams of Marines swept the area, look-ing for evidence to confirm the presence of th e

intruders . They did not find much . There were

signs that bodies had been dragged through the

area, and there was debris such as fresh, foreign-

made battle dressings, scraps of camouflage utility

uniforms, and chemical light sticks . But there were

neither bodies nor spent ammunition shells .

However, Marines later learned that the automatic

weapons carried by some Panamanian soldier s

were equipped with brass-catchers .' '

During the next several days, Captain Valore an d

his Marines were debriefed extensively by Colone l

Conley's staff, by Naval Investigative Servic eagents, and by Army intelligence specialists . Manyof these official visitors also walked the groun dover which the fight had occurred, repeating ques-tions that had been asked by others . There was

even an order from U .S. Army South for the

Marines who fought in the jungle that night to sub-mit to a urinalysis, which they did, with negative

results . 2 2

What the Marines told the debriefers was consis-

tent, and detailed . Some of their testimony wa s

also graphic. For example, when one of Cooper' s

Marines described his experiences during the fire -

fight, he began by telling the debriefer how he ha d

"gone to ground," and tried to make himself invisi-

ble . Nevertheless, one of the passing intruder sspotted him at a distance of 8 to 10 feet away. Asthe intruder began to swing his weapon toward sthe Marine, the Marine shot him twice in the ches t

with his M-16 . Upon impact, the intruder fell back

and hit the ground so hard that "his legs flopped i n

the air. " 2 3Even after the debriefings, doubts persisted .

Some members of the joint task force staff

acknowledged the threat, but wondered if the

Marines had overreacted . More frustrating for the

Marines were lingering questions about the facts .

* Valore remarked to another Marine officer that, just before

General Loeffke's arrival, he had ordered his reserve to flank

the intruders . This movement did not take place due t o

Loeffke's intervention . (Maj William J . Philbin intvw with author,

23Jun94 .)

Matters took a turn for the worse when Souther nCommand's Public Affairs Officer failed to rejectsuggestions that the Marines had fired at shadows .Noriega exploited the opportunity, using his pro-

paganda machine to plant stories about drug abuse

among the Marines, implying that the events of 1 1

and 12 April were drug-induced hallucinations . 24Marine Forces Panama overcame the challenge t o

its credibility and professionalism . Colonel Conleyand Captain Valore closed ranks behind thei rMarines, who reciprocated in kind . On the night of

13 April, when Captain Valore walked into one o f

the clubs at Rodman, all of the Marines present

cheered him. He later said that this was one of th e

highlights of his career, and that he was moved b ythe bonding and mutual trust among men who

were now combat veterans :

The [pre-combat] tension was there ; it was released . I

[had] gained their credibility. They knew I was going t o

stand behind them, whatever it took . . . They coul d

depend on me to look out for them, [and] not play poli-

tics or worry about other things . . . You have a mission t o

accomplish: you've got to take care of your Marines ." *

Valore's Marines stood down from the tank farm

for a few days of rest and recreation at Rodman . A

reinforced Army battalion took their place . On 1 4

April, Army sentries guarding the ammunition sup-

ply point challenged a small group of intruders ,

who responded with gunfire, and a patrol from th e3d Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group, operating

west of Howard Air Force Base engaged another

group of well-disciplined intruders . It was now

clear that the Marines were not the only America n

soldiers to encounter intruders and to defend

themselves . "In the months that followed, there were occa-

sional incidents, but nothing on the scale of the 1 2

April firelight . In retrospect, the aggressive Marin eresponse appeared to have had the desired effect ;the Marines had recognized the threat and

responded accordingly. Information obtained fromPanamanian officers following Operation Jus t

* Marine Forces Panama officially reported that, despite th e

challenge to Marine credibility, morale was excellent .

Headquarters Marine Corps took note of Valore's and

Nevgloski's performance, awarding both the Bronze Star Medal

with Combat "V." Sergeant Cooper received the Navy

Commendation Medal . All of the Marines involved were award-

ed the combat action ribbon . (Maj Joseph P. Valore ltr to author,

Nov93)

9

Cause, executed 20 months later in December1989, confirmed what the Marines had said aboutthe 12 April engagement. The intruders werealmost certainly troops from the 7th RifleCompany known as the "Macho de Monte," one ofthe few elite formations in the PDF, possibly rein-forced by a few members of the Special Anti-ter-rorist Security Unit, the Panamanian equivalent ofDelta Force. There is some evidence that one ormore Cuban advisors may have accompanied the'Macho de Monte' on their 12 April sortie.27

Why did the intruders attack the fuel storagearea? It is unlikely that the tanks themselves werethe targets. Even when protected by a company ofMarines, many of the tanks remained vulnerable, asdid pipelines and other peripheral installations. Ifsabotage had been the mission, the intruders prob-ably could have succeeded. Far more likely, con-sidering the timing of the attack, a few days afterthe arrival of Marine reinforcements in-country,and supported by documents seized in December1989, is the conclusion that the Marines them-selves were the main target. The object was toembarrass and harass while testing the virility andcompetence of the Panamanian military elite. Theanti-Marine propaganda campaign in the press hadonly just begun, and, as Noriega himself later com-mented: "Never before has there been a moreeffective laboratory for armed men. Nor has theopportunity [ever] been so propitious for trainingin low intensity conflict, as that which exists todayin Panama."28

Recovery and Consolidation

The month that followed was a period of relativecalm. It was one of diplomatic, rather than militaryactivity, which gave Southern Command and theMarines an opportunity to prepare for future intru-sions. The events of mid-April demonstrated theneed to resolve ambiguities in the system of com-mand and control. On 25 April, SouthCom activat-ed Area of Operation Pacific West, and formalizedthe arrangement whereby Colonel Conley becamethe commander of all of the Marines in-country, aswell as temporary attachments from the U.S. Army,including 293 soldiers of the 519th Military PoliceBattalion and Company B, 1st Battalion, 508thInfantry Regiment. Marine Forces Panamaremained under the operational control of thejoint task force, which meant that Colonel Conley

10

would continue to report to General Loeffke, eventhough the normal chain of command would havehad him to report to Admiral Gnecknow.29

In the meantime, Marines in the intelligencefield analyzed the threat, and generated a collec-tion plan in an attempt to predict future incur-sions, and the routes that they would take.Company I, after its two days of rest, went back online for another 14 days. In addition to routinepatrolling, day and night, the company improvedand hardened six observation and listening postsin both the tank farm and ammunition supplypoint.* Throughout the period, the Marine forcesconducted training exercises. First there were all-Marine, in-house exercises in the deployment ofmobile reaction forces to trouble spots. The reac-tion forces included jeep-like HMMWVs carryingheavy machine guns and TOW missiles, a signifi-cant increment in the kind of firepower which hadbeen used to good effect to suppress enemy fireon 12 April. Then there were a series of exerciseswith other services, codenamed Purple Storni foroffensive evolutions and Purple Blitz for defensiveevolutions and casualty evacuations.3

Not content with routine exercises and coun-termeasures, the Marines experimented with othermeans of accomplishing their mission. Air Forceand Navy dog teams regularly joined the Marineson patrol. Army specialists helped the Marines setup a speaker system which, when triggered,informed intruders in Spanish that they were onU.S. Government property and that it was in theirbest interest to return to where they had comefrom. At night, the Air Force continued to fly AC-130 Specter missions in support of the Marines,using beacons and infrared devices to search forintruders. There also were attempts to interceptradio transmissions between groups of intruders.However, these attempts were unsuccessful, appar-ently because the intruders relied mainly on othermeans of communication.3'

Neither War Nor Peace

The period of relative calm came to an endaround 1900 on 19 July, when sensor activationsalerted the Marines of Company L, 3d Battalion, 4th

* The ammunition supply point remained a Marine respon-sibility even though it was often patrolled by Army infantryattached to Marine Forces Panama.

Cause, executed 20 months later in December1989, confirmed what the Marines had said abou tthe 12 April engagement . The intruders werealmost certainly troops from the 7th Rifl eCompany, known as the "Macho de Monte," one o fthe few elite formations in the PDF, possibly rein -forced by a few members of the Special Anti-ter-rorist Security Unit, the Panamanian equivalent ofDelta Force . There is some evidence that one o rmore Cuban advisors may have accompanied th e"Macho de Monte" on their 12 April sortie . 27

Why did the intruders attack the fuel storag earea? It is unlikely that the tanks themselves wer ethe targets . Even when protected by a company ofMarines, many of the tanks remained vulnerable, asdid pipelines and other peripheral installations . Ifsabotage had been the mission, the intruders prob-ably could have succeeded. Far more likely, con-sidering the timing of the attack, a few days afterthe arrival of Marine reinforcements in-country,and supported by documents seized in December1989, is the conclusion that the Marines them -selves were the main target . The object was toembarrass and harass while testing the virility andcompetence of the Panamanian military elite . Theanti-Marine propaganda campaign in the press ha donly just begun, and, as Noriega himself later com-mented: "Never before has there been a mor eeffective laboratory for armed men . Nor has theopportunity [ever] been so propitious for trainingin low intensity conflict, as that which exists toda yin Panama ."2 8

Recovery and Consolidation

The month that followed was a period of relativecalm. It was one of diplomatic, rather than militar yactivity, which gave Southern Command and th eMarines an opportunity to prepare for future intru-sions . The events of mid-April demonstrated th eneed to resolve ambiguities in the system of com-mand and control. On 25 April, SouthCom activat-ed Area of Operation Pacific West, and formalize dthe arrangement whereby Colonel Conley becamethe commander of all of the Marines in-country, aswell as temporary attachments from the U .S . Army,including 293 soldiers of the 519th Military Polic eBattalion and Company B, 1st Battalion, 508thInfantry Regiment. Marine Forces Panamaremained under the operational control of th ejoint task force, which meant that Colonel Conley

would continue to report to General Loeffke, eve n

though the normal chain of command would havehad him to report to Admiral Gnecknow. 29

In the meantime, Marines in the intelligenc efield analyzed the threat, and generated a collec-

tion plan in an attempt to predict future incur-sions, and the routes that they would take .Company I, after its two days of rest, went back o n

line for another 14 days . In addition to routinepatrolling, day and night, the company improve dand hardened six observation and listening post sin both the tank farm and ammunition supplypoint . * Throughout the period, the Marine forcesconducted training exercises . First there were all-Marine, in-house exercises in the deployment ofmobile reaction forces to trouble spots . The reac-tion forces included jeep-like HMMWVs carryin gheavy machine guns and TOW missiles, a signifi-cant increment in the kind of firepower which hadbeen used to good effect to suppress enemy fireon 12 April . Then there were a series of exerciseswith other services, codenamed Purple Storm foroffensive evolutions and Purple Blitz for defensiveevolutions and casualty evacuations ." '