Corset XIX century

description

Transcript of Corset XIX century

1416

CIVILISATION IN RELATION TO THEABDOMINAL VISCERA, WITH

REMARKS ON THECORSET.

BY W. ARBUTHNOT LANE, M.S. LOND., F.R.C.S. ENG.,SURGEON TO GUY’S HOSPITAL ; SENIOR SURGEON TO THE HOSPITAL

FOR CHILDREN, GREAT ORMOND-STREET.

WE hear a great deal of civilisation, as it is called, andthe enormous advantages that accrue to humanity throughits influence. Perhaps the most apparent advantage is thesafeguarding the individual from the possibility of damageby his fellow creatures. While I would not wish to disputethe benefits which are derived from it, I would like to call yourattention to the fact that there are many very serious disad-

vantages associated with it. These deal chiefly with themechanical relationship of the individual to his surround-ings. I do not propose to do more than call attention to thenumber of conditions which very materially shorten the lifeof the man who makes his living out of laborious pursuits,and limit in a corresponding manner his capacity for the

enjoyment of life. These physical conditions represent thefixation and exaggeration of attitudes of activity, and are allprogressively depreciatory, since they necessitate a shortenedlife, not only of the joints affected, but of the entire body.Again, the fixation of attitudes of rest, such as lateral curva-ture, na1i-IOot, KnocK-Knee, <KC., nas a similar uamagngeffect, both on the altered joints and on the body generally,and materially affects the length of life and the capacity ofenjoyment of the individual.What I wish particularly to call attention to is the

disadvantage that the individual experiences from the habitof keeping the trunk constantly erect. This habit of keepingthe trunk erect from morning to night, whether the erect orsedentary attitude is assumed, is almost universal in thecondition of civilisation which exists with us in the present ,,

day. It is necessitated by our habit of using chairs and bythe fact that circumstances and surroundings do not lend Ithemselves to our lying or squatting on the floor. The erect iposture affects men and women differently, for the reasonthat the abdomen of the woman is relatively much longerthan that of the man, while the female thorax and pelvisdiffer materially from the male. The abdominal wall of thewoman is alo rendered less efficient by pregnancy and by thesupport afior led by her dress.To reiterate, I would formulate three general principles.

When an attitude of activity is assumed on a single occasioncertain tendencies to change exist. If this attitude isassumed habitually these tendencies to change becomeactualities, and the skeleton varies from the normal in pro- ’,portion to the duration and severity of the attitude. The Iskeleton is first fixed in the attitude of activity, and later Ithat attitude is progressively exaggerated. The same is trueof an attitude of rest assumed on a single occasion and alsowhen assumed habitually. The skeleton of the ordinary ornormal individual rests upon a combination of the tendenciesto change consequent on the assumption of complementaryattitudes of activity and of rest. Now, when the trunk iserect, there exist tendencies to the downward displacementof the viscera contained in the abdominal cavity. Theseveral viscera are influenced by this tendency in a varyingdegree in proportion as they themselves vary in weight. For

instance, the stomach and the large bowel are probably themost variable in weight, since a quantity of material collectsin them and passes along at a comparatively slow rate. Themore or less fluid nature of the contents of the large bowelassists in its accumulation at certain points, as, for example,in the cascum and in the middle of the transverse colon, Iwhile in the stomach the pressure is exerted on its convexity.The mechanics of the abdominal wall are such that the

muscles exert a firm pressure on the viscera and tend to

prevent their downward displacement. Still, in the abdomen,as well as in the body generally, the anatomy is so arrangedthat there must be a suitable relationship between theattitudes of activity and those of rest, or, in other words,that the erect posture, in which the viscera tend to drop, mustbe alternated snfficiently with a position in which all strainis taken off the viscera and the tendency for them to dropis in abeyance. This latter may be obtained by the

assumption of the recumbent or of the squatting posture.In the former the viscera tend to displace upwards by their-own weight, while in the latter they are forced upwards bythe forcible apposition of the thighs. In our state ofcivilisation the recumbent posture is only assumed at night,and even then only partially, since the heavy buttocks andthighs sink deeply into the bed. The squatting posture, socommon among savage races, is never employed. Thereforewith us, from an early hour in the morning till a late hourin the evening, or for at least 16 out of the 24 hours, the-

tendency to drop of the viscera exists, while during the

night this tendency is more or less in abeyance, but in adegree below the normal of the savage.Nature deals with this modification of the normal,

mechanical relationship of the individual to its surround-

ings in precisely the same way as it deals with anyspecialised mechanical function, whether active or passive.First, as regards the large bowel or cesspool of th&

gastro-intestinal tract : it attempts to oppose the downwarddisplacement of the cascum into the pelvis by the formationof peritoneal bands, not inflammatory in origin, butfunctional, if I may so use the term, which pull upwards thehepatic flexure and secure it with as much firmness aspossible in the upper and back corner of the rightloin. Acquired bands secure the outer surface of the

ascending colon and cascum in a similar way to theperitoneal lining of the adjacent abdominal wall. Theyalso grasp the appendix, commencing at its base and

forming a new mesentery, which is more or less distinctfrom its normal mesentery. In this way a portion of theappendix takes on the function of a ligament of the csecum,tending to oppose its downward displacement. Unfortu-

nately tor its new function, the appendix being a hollowtube whose mucous membrane secretes fairly abundantly, itis ill adapted for this purpose. The pull exerted by theheavy loaded cascum upon such of the proximal portion ofthe appendix as is fixed by acquired adhesions to the abdo-minal wall produces a kinking of the appendix at the junc-tion of the fixed and mobile portions. In consequence ofthis secretion tends to accumulate in the distal portion ofthe appendix and concretions form in it, or it may becomemore or less acutely inflamed, producing varying conditionsof what is called appendicitis. And unluckily for the rightovary, the appendix becomes a near neighbour, and theirritation and annoyance of the ovary may result in a cysticdegeneration of that structure. Again, the recurringmenstrual engorgements of the ovary serve also to encouragethe appendix to manifest the effects of its mechanicaldisability at these periods.The transverse colon, especially when loaded, tends also

to fall into and occupy the pelvis. The abnormal acquiredfixation of the hepatic flexure in the right loin and of thesplenic flexure in the left loin help to oppose the downwarddisplacement. Some of the load is transmitted to the

ascenamg anu aescenamg coion uy means or acquireuadhesions, which connect the descending and ascendingportions of the transverse colon respectively to the

ascending and descending colon. Above the connexionof these tubes is direct, exaggerating very much thekink at the flexures. Lower down the strain is trans-mitted along an acquired mesentery which stretches fromone to another. The greater portion of the load i&transmitted along the great omentum to the convexity of thestomach, which may itself be loaded up at the same time.This abnormal drag on the convexity of the stomach is metby the formation of peritoneal adhesions or bands, whichattach the upper and anterior aspect of the pylorus to theunder surface of the liver. The upper attachment commencesin the vicinity of the transverse fissure and extends forwards,along the under surface of the liver, not infrequently attach-ing the gall-bladder or its duct. The effect of this upwarddrag upon the pylorus and of the pull on the convexityof the stomach is to interfere with its normal functioningand to result in its progressive dilatation. The strainon the stomach is experienced along its upper margin, and !especially on either side of the pyloric attachment. It wouldanpear that in the male subject the teariug strain is greater-on the upper aspect of the first piece of the duodenum,while in the female it is greater on the proximal side. This

varying distribution of strain would be readily accounted forby the different form of the abdomen in the two sexes.

Again, if the liver itself is mobile and displaced, and the

1417

pylorus no longer depends for support on it, the point of- strain in the concavity of the stomach approaches the

- eesophageal attachment in a degree proportionate to thedownward displacement of the liver. The importance ofthese points of strain is that in t,he presence of auto-

intoxication these two factors produce engorgement of themucous membrane, its excoriation, ulceration, and later itsinfection by cancer.The descending colon acquires a connexion to the peri-

toneum lining the abdominal wall external to it, partlyto fix it, and partly to transmit the strain exerted by thetransverse colon through it. The loop formed hy the sigmoid- section of the large bowel falls into the pelvis and struggleswith the c93cum. the transverse colon, and pelvic organs forthe mastery. As the contents of the sigmoid are fairlysolid, this piece of gut is a very unpleasant and obnoxiouscompanion. Therefore Nature endeavours to fix it in theiliac fossa as a straight immobile tube connecting the de-3cending colon with the rectum. This is effected in themanner already described—name)y, by the developmentof acquired bands of adhesions resembling peritoneum in

appearance. These tags connect first the outer surfaceof the meso-sigmoid and later the outer wall of the

sigmoid to the iliac fossa, till finally a straight fixedtube, whose muscular coat is comparatively thin, witha partial peritoneal covering, replaces the original mobileloop. The left ovary is in immediate relationship withthe outer aspect of the meso-sigmoid, and very fre-

quently becomes involved in the tentaele-like peritonealprocesses fixing the meso-sigmoid and later the sigmoid.Later it becomes embedded in the adhesions and then com-

pletely surrounded by them. After a time the ovary becomes

cystic and enlarged, when it forms around itself a serons

covering so that it moves freely in a cavity. This covering. , 1 J ’I J. rra.. ’I ’I . 1

gives way, and when the aperture is sufficiently large thecystic ovary escapes. It continues to enlarge and elevatesthe csecum, transverse colon, and stomach, and to a greatextent meets the disabilities consequent on intestinal stasis.of which it is itself in this instance both the effect and thecure. Unfortunately, these cystic ovaries are more often

malignant than was originally supposed. In a large numberof cases in which I have removed large cystic ovaries I havebeen able to demonstrate, beyond a shadow of a doubt, theprpQpnce of the nest or cavity in which the cystic ovarySMW.1)"" "’.

iu a certain proportion of cases the acquired tags or bandsof peritoneum do not grip the meso-sigmoid uniformly owingto the escape of the centre of the loop In this case they.attach only the extremities of the loop, approximating themto one another and kinking both. In c’mspqnpnce, anobstruction exists at the junction of the descending colonand sigmoid, and again in a more severe form at thp end ofthe sigmoid. In consequence of the latter obstruction the

loop becomes abnormally large and nature’s efforts beingonly partially effective produce a condition which is infinitelyworse than the normal loop. and a so-ca’led volvnlns results.The fixation of the sigmoid as a straight tuhe is unfortunatelyassociated with a diminution in its calibre and in its

muscularity, and irritation, abrasion, ulceration. and cancer- oi the mucous membrar e result. In some instances abscesses

form in or about the wall of the fixed sigmoid in consequenceof the traumatism to which it is hahituallv exposed from thepassage of its c intents being rendered difficult by its fixationand limited c ,libre and muscularity. Associated with theintestinal stasis are the very serious symptoms that ensuefrom the ahsorptinn of toxins into the symptom.The earliest feature is the inhibition of the respiratory

- centre, and accompanying this, and apparently consequenton it, is the very definite enfeeblement of the circulation.These patients depend more or less completely on theirdiaphragm for obtaining enough oxyen to carry on theirmechanical relationship to their surronnr3’ngs which becomesmore and more modified as the conditi..). progresses This

brings about the several resting postures with which we are all-so familiar and which we attempt to cure b exPrcises alone,regardless of the factor which produces them. Thpir resistingpower to the entry of organisms is subnormal and the organismwhich most commonly effects a footh")d i.; t,B1he.cle. Theyounger the suhj"ft the more Ieadilv does tuhNrcle appearto be able to invade some tissue damaged hy traumatism.The pulse is very feeb’e and soft. While the trunk is fairly ’vwarm, a hand passed over the shoulder of a toxic patient

comes very auruptlyat the level of the msettion ot the deltoidon a cold zone, and this coldness becomes more marked asthe hand descends to the fingers. The skin covering theback of the upper arm is reddish-blue, very thick and gela-tinous in appearance and consistence. It is not infrequentlyrough from the presence of large prominent papillse. Thiscondition causes much distress to the mothers of girls whowear short sleeves. The skin of the forearm is bluish andmarked into islands by lines of a darker hue which correspondto the superficial veins. The hand is mottled partly by blue,partly by yellow patches. The sensation imparted to thehand of the observer by that of the toxic patient is un-mistakable. It is cold and clammy, and moist on its palmarsurface. The ears are also bluish and feel cold, as also doesthe npse, but to a much less degree. These symptoms varyconsiderably with the surrounding temperature, but are

readily recognised in the warmest weather.The pigmentation of the skin in these toxic people is a

very marked feature. Like many of the symptoms whichresult from intestinal stasis, but in a greater degree, it varieswith the colour of the hair. While dark-haired people showpigmentation in a very marked manner, those with red hairshow it slightly or not at all. In some peculiar manner red-haired people appear to possess a comparative immunity tothe effects of intestinal stasis. Except for the face, theareas that show pigmentation most conspicuously are thoseexposed to friction, such as the inner aspects of the upperparts of the thighs, with the adjacent opposing surfaces ofthe buttock, the spines and abdomen where the corset ordress presses, the axillary folds, the bend of the elbow, andthe neck. Pigmentation commences in the eyelids, spreadsover the mouth, side of the nose, and later ovf-r the cheeks.

Loss of flesh is a very serious symptom and is productiveof necessity of many secondary troubles. In the pelvis theloss of fat aids in producing the elongated contractedcervix uteri and the flexions of the uterus which are so

commonly present in these cases. In the loin it removesthat elastic support which keeps the range of movement ofthe kidney in what is regarded as normal. The loss of fatin the face and neck produces an appearance of age, distress,and disappointment which is most pathetic, particularly inthe young subject. The loss of muscularity is shown in acomplete want of tone, the muscles being flaccid and in-elastic. In the case of the abdominal muscles this is

particularly serious, since one important factor in controllingthe position of the viscera is lost more or less completely.The individual is also unable to lead an active physical lifebecause of the poor muscular development. The musclesare not only small and feeble, but become very soft andfriable, so that they tear readily, and when sutured yield andafford no security to the ligature. The condition of thebreasts is also a very important one. First, the upper andouter zone of the left breast, and later the same portion of theright, show changes. In the young subject they become hardand nobhly, and may be sore and painful at the menstrualperiods. Later in life they develop a cystic charge, which mayhe painless or may be associated with attacks of pain owingto the distension of one or more cysts. Still later these

degenerating breasts are very liable to develop cancer.

Though the degenerative change commences in the upper andouter zones it may spread to the entire breast. It is verymuch more common in the virgin, and only arises in themarried woman when intercourse is abstained from or is veryirregular. These toxic people have very little or no sexualappetite, just as they lose their appetite for food and evenhate the sight or smell of it. Perhapi the most interestingand accurate description of the influence of intestinalstasis on the sexual appetite has been written by RudyardKipling in " The Lhrht that Failed." I do not think Kiplingknew that his heroine was affected by intestinal stasis andprobably constipated, but he describes an individual withthat accuracy of observation and power of description inwhich I believe he has no equal. I need not recall the red-haired companion of the heroine, as I am sure all are

perfectly familiar with the characters in the novel.Perhal s one of the greatest of the many great men of whom

America can hoaf-t was Brigham Young ; he by irrigation’’onred a very poor district into one of the most fertile ofthe United States. He also attempted to popularise poly-gamy, and his efforts in this direction were met bv a successalmost i-qiial to those in the direction of agriculture. I amunable to form any definite opinion as to how his action was

1418 T

influenced by the knowledge of the influence of intestinalstasis on women, and the benefit which these people derive ifrom matrimony. His views on this subject certainly did notmeet with encouragement in the United States, partly, Isuppose, because of religious or legal objections, and probablyto a great extent from the ignorance of the public and evenof our profession on the subject of intestinal stasis. I aminclined to think that when women know more about the

physiology of life they may exert some influence on legisla-tion. This is more likely to develop, in the first instance, inthe United States, where both men and women hold broaderviews and are less tied by creeds and tradition than they arein the old world.The mental condition which is brought about by auto-

intoxication is most distressing. While it renders the sub-jects miserable, and unable to concentrate their attentionon work or pleasure or to control their tempers, it makesthem most unpleasant companions. An alcoholic woman

may be cheerful under the influence of her drug, but in nocircumstance does the toxaemia of intestinal stasis produceother than a depressing influence on the mind and on the1__J_ Medical ____

body generally. iviecticat men are very tond or calling tilis s

condition neurasthenia. These patients readily becomemelancholic. They frequently suffer severely from headache,either continuously or at intervals, and they awake in themorning with a headache, feeling they have obtained no restor advantage from their sleep, and that they are just as tiredand exhausted as when they went to bed. The world seems

always chill and gloomy to them, quite apart from theintestinal pain and discomfort which they so often experi-ence. My friends have often said to me that they weresure patients would never submit to such a serious opera-tion as removal of the large bowel. They forgetthat to these sufferers life has no attraction, and therisk of the operation at least affords them a chance of

escaping from it. I do not think that any patient hasexpressed to me the slightest anxiety on this score, buthas most willingly grasped the opportunity of partingwith his other troubles at all costs and at the earliestopportunity.

-- -- - - - - -

The patients usually suffer from abdominal symptoms,varying from a colicky pain due to obstruction at a flexureor at the sigmoid, or to a flatulent distension of the stomachor intestine due to decomposition produced by the delay inevacuation of the contents, or to the presence of a

pancreatitis or of gall-stones. These conditions haveresulted, partly from a direct infection of the pancreatic orbiliary ducts by organisms from the small intestinewhose level in the small intestine has been materially raised by stasis, and partly from a reduced resisting power to organisms consequent on the auto-intoxication.This infection of the pancreatic and biliary ducts does notappear to take place in such cases of intestinal stasis asarise early in life. I have never seen it in patients in whomloss of flesh has been a marked feature before 20 years of

age. Infection of the gall-bladder and later of the pancreasarises in stout patients who develop intestinal stasis at orbeyond middle life. It would seem that the loss of flesh andof vigour consequent on the toxæmia of intestinal stasis soaffects the mechanics of the gall-bladder as to produce anaccumulation of bile in it and in association with the infec-tion of the ducts to determine the formation of stones in it.Here again intestinal stasis is responsible for an inflamma-tion of these structures followed later by a cancerous

infection.I have endeavoured to indicate the importance of the fall

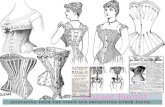

of the viscera in the erect posture. Obviously the mosteffectual means of mf eting this condition is by theexercise of a sufficient pressure exerted appropriately on thelower abdomen. For a long time women have been in thehabit of wearing corsets for the purpose of supporting theirdress and of affording attractive outlines to their bodies.The English corset is disastrous in that it exerts a constrict-ing encircling pressure on the abdomen about the lower costalmargin and exaggerates the tendency to downward displace-ment of the viscera. The straight-busked French corset ismuch less harmful, and if skilfully made and applied servesto exert a moderate pressure on the lower. abdomen.The corset that is most efficient is one that, while

exerting a firm and constant pressure in a backwardand upward direction on the abdomen below the umbilicus,leaves the upper portion of the abdomen quite free.

Owing to a want of knowledge of the pathology of intes-tinal stasis the corset has not received the attention itdeserves, so that by far the most important factor in thetreatment of intestinal stasis and of its effects has been leftin abeyance. I would strongly urge its therapeutic value onthe medical profession as being the most effectual means Iknow by which the trouble to which I have called attentionin these remarks may be avoided or mitigated.Cavendish-square, W.

ON RHYTHMIC INTERRUPTERS FOR USEIN ELECTRO-THERAPEUTIC WORK.

BY H. LEWIS JONES, M.D. CANTAB., F.R.C.P. LOND.,MEDICAL OFFICER IN CHARGE OF THE ELECTRICAL DEPARTMENT,

ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S HOSPITAL; LATE PRESIDENT OF THEBRITISH ELECTRO-THERAPEUTICAL SOCIETY.

THE advantage of using regularly varying currents inmany of the procedures of electrical treatment is graduallybecoming more widely recognised, and although suchcurrents have not yet come into general use, I considerthat they are shortly destined to do so. One of the causeswhich have delayed their adoption has been the difficulty ofobtaining apparatus for providing regularly varying currents,but this has now been overcome.During rhythmical electric stimulation the tissues stimu-

lated are given recurrent intervals of repose in the course ofthe treatment, and time is thus given for renewal of blood-supply and fatigue is prevented. A sustained stimulationwithout any intervals tends to induce fatigue quickly, par-ticularly in weak or paralysed muscles, and it is probablethat harm may be done by electrical applications which setup a sustained tetanisation in such muscles. If experimentalproof were needed of the value of rhythmic stimulation, it isto be found in the experiments of Debedat upon the musclesof young rabbits. He showed that rhythmic stimulationof the muscles of one hind limb for 10 minutes daily caused,after 20 days, an increase of 40 per cent. above the weightof the corresponding untreated limb. The current used wasthat of an induction coil. With continuous current also

applied rhvthmically the increase was only 18 per cent.When similar applications, but with no rhythmic intervals,were used the gain in weight was nil both for interruptedand continuous currents. Bordier, working with human

subjects, has obtained similar proofs of the good effect of £

rhythmic currents, for he reports an increase in girth of £half an inch in the arm after two months of rhythmicstimulation.By the term rhythmic interrupter "is meant a mechanicaldevice for turning currents on and off in a regular periodicmanner, and there are two main varieties of rhythmicinterrupter, giving different effects, and both are valuable inmedical treatment. In the older type the current is simplyswitched on and off at a uniform rate, the change fromI I on " to I I off " being abrupt ; while in the newer type thereis a gradual growth of current from zero to its maximum,followed by a similar gradual decrease to zero again. Thisis the most generally useful type of rhythmic interrupter,but the first type requires some brief notice, too. It will,perhaps, suffice to say that for sudden turning on and offof current a simple metronome with wires dipping into mercurycups and out of them filJs the requirements completely. This

apparatus is well known in physiological work and is knownas Kronecker’s (more correctly Bowditch’s) metronome. This

type of rhythmic interrupter, in one form or another, has beenin use since the very early days of electro-therapeutics. It isof very great utility in electrical diagnosis, and I have foundit valuable in the treatment of wry-neck and of other

spasmodic affections, and in functional aphonia. It appearsthat for these cases the steady rhythm- of the make andbreak has a psychological effect of a useful kind, and whentreating functional aphonia I insist on the patients countingin time with the beats of the instrument, with the sameobject. With this metronome the rate of the rhythm canbe varied within sufficiently wide limits, and the duration ofeach period of flow of current can be regulated by adjust-ments of the mercury cups and the dipping wires to permitof the dipping wire to plunge either deeply or slightly, asdesired.