Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities through … Entrepreneurship Activities through Strategic...

Transcript of Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities through … Entrepreneurship Activities through Strategic...

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities throughStrategic Alliances: A Resource-Based Approachtoward Competitive Advantage*

Bing-Sheng TengGeorge Washington University

abstract Corporate entrepreneurship (CE) activities may significantly benefit from interfirmstrategic alliances, although such benefits have not been sufficiently examined in the literature.In this paper, a resource-based framework is presented to examine how strategic alliances offerentrepreneurial firms needed resources that may not otherwise be available. We argue thatCE activities are likely to lead to resource gaps. We compare various options to fill resourcegaps, and identify the pros and cons of the alliance approach. We then discuss the resourceconditions that provide competitive advantage for a firm, if alliances are properly used to helpimplement CE. Finally, we examine how different types of alliance (e.g. joint ventures, R&Dalliances, and learning alliances) facilitate various CE activities, including innovation, corporateventuring, and strategic renewal.

INTRODUCTION

The past decade has witnessed high rates of change in the market place, in areas such astechnology, globalization, and industry boundaries. To be successful, a firm must havethe capacity to innovate faster than its best competitors. Essentially, this capacity is aboutidentifying new ways of doing business, developing new technologies and products, andentering new markets in new organizational forms. These activities are often collectivelycalled corporate entrepreneurship (Covin and Slevin, 1991), which can be defined as ‘thesum of a company’s innovation, renewal, and venturing efforts’ (Zahra, 1995, p. 227).

While entrepreneurship has been traditionally viewed as being individual-level activi-ties related to creating new organizations, the notion of corporate entrepreneurship (CE)extends the idea of being bold, proactive and aggressive to established firms. Thus, CEbecomes an integral part of the strategic management of a firm (Burgelman, 1983; Desset al., 1997). Despite the significant overlap, the two research areas of CE and strategicmanagement continue to be separate realms (Barringer and Bluedorn, 1999).

Address for reprints: Bing-Sheng Teng, Department of Strategic Management and Public Policy, School ofBusiness, George Washington University, 2201 G Street, NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA ([email protected]).

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKand 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

Journal of Management Studies 44:1 January 2007doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00645.x

One area that exemplifies the lack of connection between CE and strategic manage-ment is the role of strategic alliances in CE (Cooper, 2002). Strategic alliances areinterfirm cooperative arrangements aimed at achieving firms’ strategic objectives (Gulati,1995a; Parkhe, 1993). Examples of alliances include joint ventures, minority equityalliances, joint R&D, and joint marketing. Strategic alliances as a cooperative strategyhave become increasingly important in recent years (Doz and Hamel, 1998). Alliancesappear to be closely related to CE, as both aim at achieving flexibility for a firm ( Yoshinoand Rangan, 1995).

Researchers have studied how small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) utilize thealliance approach (Dickson and Weaver, 1997; Dollinger and Golden, 1992; Golden andDollinger, 1993; Marino et al., 2002; Steensma et al., 2000; Zacharakis, 1998). However,along with a few other papers (e.g. Cooper, 2002; Deeds and Hill, 1996), these studiescover some aspects of the linkage but do not offer a theoretical framework that relates CEand alliances systematically. Strategic management theories may help provide such alinkage. The aim of this paper is to provide an explanation of how strategic alliances helpfacilitate CE activities, through the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm. RBV empha-sizes internal sources of competitive advantage and the fact that firms possess heteroge-neous resources that cannot be perfectly imitated, substituted, or traded (Barney, 1991;Wernerfelt, 1984).

There is a potential fit between CE and RBV since entrepreneurship may be viewedas ‘carrying out new combinations’ (Schumpeter, 1934). Whether the new combinationstake the form of new products, new processes, new markets, or new organizations, theessence is a new way of combining internal and external resources. Indeed, ‘all typesof entrepreneurship are based on innovations that require changes in the pattern ofresource deployment and the creation of new capabilities . . .’ (Stopford and Baden-Fuller, 1994, p. 522). Thus, RBV is potentially a pertinent approach toward understand-ing CE, as entrepreneurship is about leveraging existing resources to obtain additionalresources (Greene et al., 1999).

Although researchers have paid attention to resource issues in CE (Alvarez andBarney, 2002; Barringer et al., 1998; Brush et al., 2001; Greene and Brown, 1997), muchless has been done to systematically and adequately apply RBV to CE. In the last fewyears, some progress has been made through two special issues on CE. In the Entrepre-

neurship Theory and Practice issue, Greene et al. (1999) study the role of the corporateventure champion from an RBV perspective, while Borch et al. (1999) examine howfirms’ resource configurations affect their competitive strategies. In the Strategic Manage-

ment Journal issue, Lee et al. (2001) identify internal capabilities as key determinants forperformance in technology-based ventures, while Rothaermel (2001) reports that firmsadapt to radical technological changes by exploiting complementary assets in alliances.

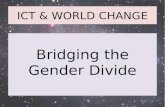

Collectively, these studies provide great insight into the role of resources in CEactivities. However, they fall short in offering a RBV framework of CE that systemati-cally answers a critical RBV question: how do CE activities lead to competitive advan-tage for a firm? To this end, an RBV framework will be developed in this paper based ona well-developed RBV concept that views resource conditions as a prerequisite forcompetitive advantage (Peteraf, 1993). According to this model as shown in Figure 1, CEactivities are likely to create resources gaps, which in turn encourage firms to employ

B-S. Teng120

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

strategic alliances to access external resources. Competitive advantage depends onwhether alliances and CE activities jointly lead to desirable resource conditions in thefirm.

The paper is divided into four sections. The first section is about why CE activitiestend to lead to resource gaps. The second section compares various options to fillresource gaps with a focus on strategic alliances. This is followed by a discussion on theresource conditions that will provide competitive advantage for a firm, if alliances areproperly used to implement CE. The final section examines how different types ofalliance may facilitate various CE activities.

RBV AND RESOURCE GAPS IN CE

Characteristics of CE

CE is the process through which firms innovate, form new businesses, and transformthemselves by changing the business domain or processes (Guth and Ginsberg, 1990).Firms actively engaging in these activities can be called entrepreneurial firms. Lumpkinand Dess (1996) suggest that an entrepreneurial firm has characteristics such asautonomy, innovativeness, risk taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness.Similarly, Covin and Slevin (1991, p. 7) define an entrepreneurial posture as the overallstrategic orientation of a firm that is ‘risk taking, innovative, and proactive’.

According to Stevenson and Jarillo (1990), a key feature of entrepreneurship is a focuson achieving exceptional growth, which is a goal that motivates firms to take risks andbecome innovative and proactive. In order to achieve growth, entrepreneurial firmsaggressively pursue opportunities in their environment. As such, Brown et al. (2001, p.954) believe that ‘contemporary definitions of entrepreneurship tend to center aroundthe pursuit of opportunity’. The ongoing pursuit of opportunities is not only a funda-mental objective of, but also an approach in, entrepreneurship (Kaish and Gilad, 1991).In order to pursue opportunities, entrepreneurial firms are unusually alert to opportu-nities (Kirzner, 1973).

CorporateEntrepreneurship

• Innovation • Corporate Venturing • Strategic Renewal

P3–6 Sustained Competitive Advantage

P1

P7–9

Resource Gap P2

Strategic Alliances Resource Conditions

• Joint Ventures • R&D Alliances • Learning Alliances

• Heterogeneity • Ex post Limits to

Competition • Imperfect Mobility • Ex ante Limits to

Competition

Figure 1. A resource-based framework of corporate entrepreneurship and strategic alliances

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 121

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

In short, CE takes place when a firm emphasizes growth through actively recognizingand exploiting opportunities. Entrepreneurial firms are growth and opportunity-oriented, while other firms’ actions are more limited by their current resources (Covin,1991; Wright et al., 2000). This view of CE complements other perspectives of CEcharacteristics. For example, it can be argued that an orientation toward opportunitiesrequires a firm to be risk taking, innovative, and proactive.

CE encompasses three major components: innovation, strategic renewal, and corpo-rate venturing (Zahra, 1995, 1996). Innovation refers to ‘creating and introducing newproducts, production processes, and organizational systems’, while strategic renewalmeans transforming the firm, or ‘revitalizing a company’s operations by changing thescope of its business, its competitive approach, or both’ (Zahra, 1996, p. 1715). Corpo-rate venturing involves entering new businesses through the creation or purchase of newbusiness organizations (Block and MacMillan, 1993; Chesbrough, 2002).

An orientation toward growth and opportunities tends to exist in all three types of CEactivities. First, corporate venturing is more likely when a firm is preoccupied with newopportunities for growth. One of the key drivers for the creation of new businesses is adesire to grow rapidly and take advantage of opportunities in new markets that areunattainable for the current organization (Block and MacMillan, 1993). By definition,new businesses are focused on growth. Second, innovation is encouraged by an entre-preneurial posture, as new products and production processes are often necessary inorder to seek new opportunities for growth (Covin and Miles, 1999). Innovation focuseson developing new resources and capabilities that offer growth opportunities. Third, aneed to seek opportunities for growth encourages strategic renewal efforts. Growth maybe achieved by revitalizing the business scope or the business model (Stopford andBaden-Fuller, 1994). In addition, pursuing new growth opportunities often requires asignificant change in the way that a firm conducts business.

CE and Resource Gaps

A firm’s CE activities have significant resource implications, which usually include aresource gap. The reason is that an entrepreneurial firm pursues opportunities, ‘regard-less of resources currently controlled’ (Stevenson and Jarillo, 1990, p. 23). The wholepoint of CE is to seek opportunities that stretch the resource base of the firm withoutentirely breaking with its resource base. Thus, an entrepreneurial firm often focuses onexpanding as quickly as possible, although it may not possess all needed resources(Barringer et al., 1998; Dougherty, 1995). Such a firm is viewed as risk taking andaggressive, precisely because its action is not entirely limited by its current resources. Theresult is often a certain resource gap in implementing CE (see Figure 1). As such,entrepreneurial firms are believed to be ‘resource-constrained’ (Brush and Chaganti,1997; Zacharakis, 1998). Although CE activities do not always lead to resource gaps (dueto possible slack resources in the firm), opportunity- and growth-oriented firms are muchmore likely to experience resource gaps.

The concept of resource gap is related to Cool and Schendel’s (1987) notion of risk,which has to do with the match (or difference) between one’s available resources and itsselected strategies. Since there are various types of resources, there are various types of

B-S. Teng122

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

resource gaps. A resource gap can be defined by the type and quantity of neededresources. For example, a firm may have a gap of $10 million in financial resources, whileanother may have a gap with respect to a strong R&D department (i.e. technological andhuman resources). Rapid-growth firms often lack managerial capacity and use variousmechanisms to mitigate the problem (Barringer et al., 1998). As such, ‘resource acqui-sition constitutes a major theme in entrepreneurship’ (Dougherty, 1995, p. 113). The factthat entrepreneurial firms tend to be more concerned with a lack of resources under-scores that resource gaps are a common issue in CE.

In entrepreneurial firms, resource gaps may not be avoided simply through internalallocation of resources, as these gaps result from a firm level growth orientation. Forinstance, corporate ventures may leverage their existing resources to get additionalresources from the parent firm (Greene et al., 1999); but such efforts often cause resourceshortages elsewhere in the firm. Bank One Corp., which was generally viewed asentrepreneurial, created Wingspanbank.com, a corporate venture, in 1999 to explore theonline banking market. In the first year alone the venture obtained over one hundredmillion dollars from the parent firm to launch the new business. The result was intensifiedresource constraints within Bank One, as its earnings were brought down 5 cents pershare (Osterland, 1999). Thus, when the overall firm aggressively pursues opportunitiesand growth, there is likely a firm level resource constraint. With a mandate for growth,various units will be intensively competing for internal resources. Thus, internal resourceallocation alone may not fill all resource gaps in an entrepreneurial firm. CE activitiesand firm level resource gaps tend to go in tandem.

Proposition 1: Since the CE activities of pursuing opportunities for growth are resourceintensive, firms engaging in CE activities are more likely to face resource gaps thanother firms.

FILLING RESOURCE GAPS

In order to carry out an entrepreneurial strategy, resource gaps need to be filled.Essentially, there are four different ways to fill a resource gap: internal development,market transactions, acquisitions, and strategic alliances. Table I compares the fouralternatives in terms of their possibility, cost, benefit, and risk.

Alternatives in Filling Resource Gaps

The first option is to fill resource gaps internally. The benefit of internal developmentand accumulation of resources is that it provides a firm with total control. Nevertheless,internal development is often not feasible for economic or competitive reasons. The firmmay lack internal ability to develop resources such as new technologies in a timelyfashion. This is especially true in a hypercompetitive environment in which the emphasisis on quick responses to opportunities (D’Aveni, 1994). Moreover, the risk in developingnew products, technologies, and capabilities is usually high.

When needed resources cannot be effectively or efficiently developed internally, thefirm has to locate an external source, or forego the opportunity. The second option is

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 123

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

Tab

leI.

Com

pari

ngal

tern

ativ

eap

proa

ches

infil

ling

are

sour

cega

p

Det

erm

inin

gfa

ctor

sIn

tern

alde

velo

pmen

tR

esou

rce

acqu

isitio

nin

fact

orm

arke

tsA

cqui

sition

s(o

fen

tire

firm

s)Str

ateg

ical

lian

ces

Poss

ibili

ty•

Inte

rnal

abili

ty•

Tra

dabi

lity

(tang

ible

)•

Tar

get

firm

avai

labi

lity

•Pa

rtne

rfir

mav

aila

bilit

y•

Tim

efra

me

•M

arke

tav

aila

bilit

y•

Ant

i-tru

stre

stri

ctio

nsC

ost

•H

igh

deve

lopm

ent

cost

•L

owtr

ansa

ctio

nco

st•

Hig

hpu

rcha

sepr

ice

•R

elat

ivel

ylo

wst

art-

upco

stB

enefi

t•

Tot

alco

ntro

l•

Effi

cien

cy•

Ow

ners

hip

ofth

een

tire

valu

ech

ain

•Fl

exib

ility

and

spee

d•

Shar

edco

sts

and

risk

sR

isk

•H

igh

risk

offa

ilure

•R

isk

ofno

tha

ving

com

petit

ive

adva

ntag

e•

Ris

kw

itha

lem

on•

Diffi

cult

toin

tegr

ate

•In

abili

tyto

dive

stun

need

edas

sets

•T

empo

rary

reso

urce

acce

ss•

Diffi

cult

tom

anag

e•

Ris

kof

oppo

rtun

ism

B-S. Teng124

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

resource acquisition in factor markets (Barney, 1986). An important premise is theresource’s tradability (Chi, 1994). Certain tangible resources such as physical, human,and financial resource can be purchased via product, labour, and capital markets.Certain technological, knowledge, and organizational resources may be obtainedthrough licensing, consulting, and outsourcing agreements, which are contract-basedmarket transactions. The benefits of this approach include low transaction costs and ahigh level of efficiency. However, the viability of this approach is also limited by marketavailability of the particular resource. For example, it is rather rare that a desirable brandname is available for purchase. Also, a risk of this approach is that publicly availableinputs are unlikely to have sustainable differentiating effects. Since key resources relatedto competitive advantages are usually not for sale, a reliance on external resource maylead to mediocrity.

The third option is an acquisition of another firm that possesses one’s needed resources(Park, 2002). Through an acquisition, a firm permanently obtains all resources of a targetfirm along its value chain. However, acquisitions may not be possible due to a lack oftarget firms and anti-trust restrictions. Acquiring firms also tend to pay a high price forstrong firms with valuable resources. The possibility of overpaying is high because of theasymmetry of information regarding the true value of the target firm; the seller usuallyknows better than the buyer. Thus, the seller usually appropriates a substantial share ofthe economic profit from the transaction. In addition, the acquisition mode runs the risksof (1) purchasing a firm with serious but previously unknown problems (i.e. a lemon), (2)difficulty in integrating two firms, and (3) difficulty in divesting unwanted assets. Indeed,most acquisitions fail to create synergy through integration (Birkinshaw et al., 2000).

The acquisition mode is often compared with the fourth option – the alliance mode(Hagedoorn and Sadowski, 1999). Strategic alliances are interfirm cooperative arrange-ments that allow firms to temporarily seek resources from others for one’s own benefit(Das and Teng, 2000; Grant and Baden-Fuller, 2004). As compared to the other options,strategic alliances are flexible and allow shared costs and risks among partner firms.However, strategic alliances have their share of pitfalls. Not only are good partners hardto identify, alliances are also difficult to manage due to shared decision making andcontrol, conflicting objectives of partners, and opportunistic behaviour (Parkhe, 1993).Moreover, since resource access in alliances is only temporary, there is uncertainty aboutthe long-term availability of resources.

Strategic Alliances and Resource Gaps

In this paper, the focus is on strategic alliances as a way to fill resource gaps. Becausestrategic alliances help access resources, RBV appears to be an appropriate theoreticalperspective for understanding alliances. Das and Teng (2000) develop a resource-basedtheory of alliances, which suggests that accessing essential and valuable resources notowned by the firm is the fundamental reason behind strategic alliances. Much additionalsupport is available in the literature for this view. According to the resource dependenceperspective, interfirm relations are developed to better manage a firm’s dependence onother firms’ resources (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978). In this sense, alliances may be used toco-opt support from other strong firms (Starr and MacMillan, 1990). Also, Ahuja (2000,

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 125

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

p. 319) notes that ‘resource deficiency’ induces interfirm linkages. Finally, Eisenhardtand Schoonhoven (1996, p. 137) suggest that ‘a logic of strategic resource needs’ is adriver toward cooperative relationships.

For entrepreneurial new ventures, research shows that strategic alliances are used tofill resource gaps (Brush and Chaganti, 1997; McGee and Dowling, 1994; Zacharakis,1998). In the context of CE, limited empirical research provides support for certainaspects of the same relationship. Barringer et al. (1998) report that rapid-growth firms usealliances to deal with a lack of managerial capacity. In sum, strategic alliances would beused more in situations with resource gaps than without resource gaps. Combining thisidea with Proposition 1, which suggests that entrepreneurial firms tend to face resourcegaps, it seems likely that entrepreneurial firms would have a higher tendency to formalliances than other firms (see Figure 1). Empirically, Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven(1996) cover one aspect of CE (i.e. innovation) and find that more innovative firms tendto be more active in alliance formation. It should be noted that active alliance formationdoes not necessarily suggest greater success in entrepreneurial firms. Whether CE activi-ties through alliances lead to competitive advantage will be examined in the next section.

Proposition 2: Since strategic alliances help fill resource gaps in CE activities, allianceswill be used more extensively by firms engaging in CE activities than by other firms.

RESOURCE CONDITIONS AND COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE IN CE

Since the word ‘entrepreneurship’ conjures up a positive image of being bold andinnovative, researchers generally see CE as positively related to competitive advantage(Zahra, 1996). For example, there is a belief that ‘entrepreneurship is an essential featureof high-performing firms’ (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996, p. 135). However, it seems unlikelythat CE always has positive effects on a firm’s competitive advantage. Empirical researchhas shown that an entrepreneurial strategy works under certain conditions but not others(Covin and Slevin, 1989). The contingent relationship between CE and environmentaland organizational variables has received increasing support (Dess et al., 1997).

Similarly, the integrative effects of CE and strategic alliances also appear to follow acontingent pattern. McGee et al. (1995) adopt a contingency approach and find thatstrategic alliances perform best with new ventures whose management teams have moreexperience. Sarkar et al. (2001) find that the positive effects of alliance proactiveness onfirm performance are stronger for small firms and in unstable market environments.Indeed, although strategic alliances assist in filling resource gaps in CE, their integrationdoes not necessarily provide competitive advantages to a firm. In this section, RBV isapplied to examine how strategic alliances help CE meet resource conditions that createcompetitive advantages (see Figure 1).

A Resource-Based View of Competitive Advantage

RBV suggests that the purpose of any strategy is to enhance the value-creation potentialof firm resources (Reed and DeFillippi, 1990; Wernerfelt, 1984). The potential forvalue-creation is based on certain conditions, such as resource characteristics (Barney,

B-S. Teng126

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

1991; Dierickx and Cool, 1989). Sustainable competitive advantage hinges on whetherthese positive conditions can be met. By this criterion, a combination of CE and strategicalliances should aim at meeting these desirable resource conditions. Barney (1991)suggests that resources that can lead to competitive advantage need to meet four con-ditions: valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and imperfectly substitutable.

These conditions are not limited to any single resource; rather, it is considereddesirable when a firm’s overall resource profile (i.e. combination of resources) meets thesefour conditions. Peteraf (1993) develops this line of thinking and proposes the followingfour resource conditions that are ‘cornerstones of competitive advantage’: heterogeneity,ex post limits to competition, imperfect mobility, and ex ante limits to competition.

First, heterogeneity refers to a condition of owning superior resources that are scarcein an industry (Peteraf, 1993) – this argument can be viewed as a combination of valueand rareness in Barney’s (1991) framework. Second, a condition of ex post limits tocompetition suggests that after a firm acquires certain superior resources, there are forcesthat limit competition for those resources. Two of the forces are Barney’s (1991) notionsof imperfect imitability and imperfect substitutability. Third, superior resources aresustainable if they cannot be perfectly traded, i.e. a condition of imperfect mobility.Imperfect mobility ensures that resources cannot be easily bid away from the company.Finally, ex ante limits to competition means that the cost of acquiring superior resourcesis not too high to offset any future benefits. We now discuss how CE can be fit withstrategic alliances to meet these four resource conditions.

Heterogeneity

The RBV suggests that each firm is idiosyncratic because of the different resources thatit has obtained over time (Wernerfelt, 1984). Resource heterogeneity is the degree towhich a firm has unique resources or a unique resource profile in an industry. To achieveresource heterogeneity, a firm needs to acquire superior or valuable resources that arescarce. With the help of an appropriate strategic alliance, CE activities can acquire suchresources for novel combinations (Stopford and Baden-Fuller, 1994).

Valuable resources usually reside in firms that have a different resource profile thanthat of the focal firm, i.e. low resource similarity. Following Chen (1996, p. 107), resourcesimilarity refers to the extent to which two firms possess ‘strategic endowments compa-rable, in terms of both type and amount’. Resource similarity strongly influencesresource fit between partners, or the match between one’s resource needs and another’sresource endowment. Researchers have emphasized the value of a complementaryrather than a supplementary fit (Das and Teng, 2000; Rothaermel, 2001). When partnerfirms have diverse resource profiles (or low resource similarity), chances are better thatone has resources that can fill a resource gap of another.

Nevertheless, a non-entrepreneurial firm may not prefer a complementary fit as ittends to be more concerned with protecting its own valuable resources in an allianceprocess. When there is low resource similarity, it may be concerned that other firms mayact opportunistically and appropriate its own superior resources through the alliance(Hamel, 1991). Thus, a better fit for a non-entrepreneurial firm is to maintain theresource heterogeneity it already possesses. It was proposed earlier that non-

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 127

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

entrepreneurial firms are less active with alliance formation. It seems that when they doget involved, they would play safe by allying with those with similar status and resources(i.e. a supplementary fit).

In contrast, entrepreneurial firms see a fit in focusing on low resource similarity in theiralliances (i.e. a complementary fit). Since an entrepreneurial firm is aggressive and risktaking (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996), it tends to work actively to get access to complemen-tary resources of its partner firms. While it is probably safer and easier to combine similarresources, bigger rewards are usually associated with bundling dissimilar resources. It isthe creative bundling of different resources, rather than simple accumulation of similarresources, that allows for new ways of doing businesses (Ellis and Taylor, 1987; Zahra,1995).

Therefore, focusing on a complementary fit in alliances is a good strategy for anentrepreneurial firm. In the process, the firm will obtain access to superior resourcesotherwise unavailable to it and further develop resource heterogeneity (Das and Teng,2002). Of course, alliances may result in increasing resource similarity between partnerfirms, as a result of interfirm learning (Mowery et al., 1996). A more important test,however, is whether the firm has achieved increased resource distinction (or heteroge-neity) as compared to its competitors.

Proposition 3: As compared to other firms, firms engaging in CE activities benefit morefrom strategic alliances with a complementary rather than supplementary fit betweenpartner firms.

Ex post Limits to Competition

Ex post limits to competition involve obtaining resources imperfectly imitable andsubstitutable. CE activities are likely to lead to this desirable resource condition if astrategic alliance is focused on areas with strong first-mover advantage. First-moveradvantage broadly refers to the various benefits of taking actions earlier than competi-tors, including economies of scale, switching costs, limited demand and supply, andlearning curves (Liberman and Montgomery, 1988). While early market entry oftencreates first-mover advantage (i.e. entry barriers), there are a host of other first-moveractions such as developing new technologies, introducing new products, starting newmarketing campaigns, initiating price reduction, and even exiting the market early. Thekey lies in taking initiatives that lead to advantageous positions difficult and costly forcompetitors to replicate.

There is a good fit between CE and a focus on first-mover advantage because anentrepreneurial firm is more aggressive and proactive. CE is about being innovative andtaking a lead in the market. It also involves taking advantage of the benefits of risky andpioneering endeavours. A non-entrepreneurial firm, by comparison, would not pursuefirst-mover advantage aggressively, as it is preoccupied with the potential risks involvedin moving first, or ‘first-mover disadvantage’ (Liberman and Montgomery, 1998). Sucha firm tends to avoid becoming a first-mover since it is more concerned with theadditional uncertainty and resource commitment.

B-S. Teng128

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

For an entrepreneurial firm, the benefits from a pioneering effort lead to possessingresources that are difficult to imitate or substitute, and achieving positions difficult andcostly to replicate. For instance, it is very difficult to replicate one’s advantage based onname recognition. Similarly, first-mover advantage based on patented technology, con-tracts, and learning curves has limited imitability and substitutability.

Strategic alliances can be an effective approach in pursuing first-mover advantage inCE efforts ( Yoshino and Rangan, 1995). Since alliances can be quickly forged, they mayexecute CE activities swiftly enough to obtain an advantageous position ahead of com-petitors. Thus, in implementing CE, firms should focus their cooperative efforts on areaswith strong potential first-mover advantage, such as significant economies of scale, patentprotection, competitive niches with limited demand, and strong reputational effects. Inessence, alliances will be more desirable when they help carry out CE activities that aredifficult to imitate and substitute.

Proposition 4: As compared to other firms, firms engaging in CE activities benefit morefrom strategic alliances that help them develop first-mover advantage.

Imperfect Mobility

Entrepreneurial firms tend to generate imperfectly mobile resources when their strategicalliances focus on developing relation-specific assets. Relation-specific assets are ‘special-ized in conjunction with the assets of an alliance partner’ (Dyer and Singh, 1998, p. 662).Williamson (1985) suggests three ways that assets can be specified to a relation: sitespecificity, physical specificity, and human asset specificity. All three suggest a lack ofresource mobility. Site specificity is the immobility of locations. Physical specificity refersto a lack of mobility in terms of physical resources (e.g. machinery), if they are madespecific to the needs of a given firm or alliance. Finally, human asset specificity is thehuman knowledge developed in a relation that cannot be transferred to other settings.

Strategic alliances are often used to facilitate asset specificity, or developing relation-specific assets (Kogut, 1988). Relation-specific assets developed through alliances canreduce coordination costs and lead to more effective and efficient communications (Dyer,1996). When partner firms develop assets that are specific to their relationship, theireffectiveness in cooperation and their trust in each other increase significantly. Making‘nonrecoverable investments’ signals a high level of commitment in alliances (Parkhe,1993).

Notwithstanding their possible benefits, relation-specific assets may not be valuable toall firms. A non-entrepreneurial firm may prefer to limit its embeddedness in an alliance,which may have negative effects on the firm (Rowley et al., 2000). This firm may bepreoccupied with the potential high risk of opportunism. After all, asset specificity meansthat the resources cannot be traded or transferred to another firm without losing muchof the value (Dierickx and Cool, 1989). Therefore, developing relation-specific assetsmay be too risky a strategy for a non-entrepreneurial firm, in case it needs to exit froman alliance.

An entrepreneurial firm, however, would work well with a strategic alliance focused ondeveloping relation-specific assets. Again, when a firm is more aggressive and oriented

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 129

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

toward risk taking, it finds a fit with a strategy that relies on trust, long-term commitment,and mutual forbearance. Indeed, trust in a relationship can be seen as taking risk with (orbeing vulnerable to) someone in whom one has confidence (Das and Teng, 2001). Arisk-avoiding actor is less willing to trust precisely because of the inherent risk. Thus, anentrepreneurial firm will be more suitable to focus on relation-specific assets than anon-entrepreneurial firm.

Proposition 5: As compared to other firms, firms engaging in CE activities benefit morefrom strategic alliances with significant relation-specific assets.

Ex ante Limits to Competition

Limited ex ante competition ensures that potential benefits from superior resources arenot completely competed away during the bidding process. The key is for a firm to have‘the foresight or good fortune to acquire it in the absence of competition’ (Peteraf, 1993,p. 185). Good fortune aside, foresight and insight come from tacit knowledge about theresources and their possible utility. Not all firms have such tacit knowledge because of‘causal ambiguity’, or the lack of understanding of the utilities of resources (Lippman andRumelt, 1982). Causal ambiguity may come from several sources, including tacitness,complexity, and specificity (Reed and DeFillippi, 1990).

Tacit knowledge represents a specific type of resource. While the conventionaldichotomy is between tangible and intangible ones (Grant, 1991), Miller and Shamsie(1996) offer a typology of two broad types of resources: property-based and knowledge-based. Property-based resources are those assets legally owned by a firm, includingphysical, financial, patents and so on. In contrast, knowledge-based resources (or tacitknowledge) are more implicit and cannot be easily protected against unauthorizedtransfer. They include managerial, organizational, and certain technological resources.Like resources, resource gaps can be defined as primarily property-based or knowledge-based. In this sense, the resource gap in creating ex ante limits to competition is primarilya knowledge-based one.

CE activities may allow a firm to obtain valuable resources without a lot of competi-tion, if a strategic alliance focuses on obtaining tacit knowledge about these resources. Asnoted, strategic alliances such as joint ventures and learning alliances can be an effectiveway to share and develop tacit knowledge with partner firms (Doz, 1996; Hamel, 1991).However, knowledge transfer has both positive and negative effects for alliance partners;while it is usually beneficial to the learning party, its partner(s) may lose distinctivecompetence as a result of unintended knowledge appropriation. Nevertheless, knowledgetransfer is often essential for smooth alliance operation, and authorized knowledgetransfer is a key part of many alliances (Inkpen, 1998).

Despite the importance of knowledge transfer, a non-entrepreneurial firm may notbenefit as much from a focus on tacit knowledge, since it is more manageable to focus ontangible property-based resources such as patented technology or financial capital. Incontrast, an entrepreneurial firm tends to have a good fit with a focus on knowledge inalliances because innovation, a central entrepreneurial activity, depends on the use of

B-S. Teng130

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

tacit knowledge. Since CE is oriented towards seeking future opportunities, tacit knowl-edge such as foresight and insight is valued more by entrepreneurial firms.

Proposition 6: As compared to other firms, firms engaging in CE activities benefit morefrom strategic alliances in which significant tacit knowledge is developed and shared.

SPECIFIC CE ACTIVITIES THROUGH STRATEGIC ALLIANCES

As we discussed, strategic alliances benefit CE activities by helping fill resource gapsfaced by entrepreneurial firms. This section examines the specific ways that strategicalliances help carry out the various CE activities: innovation, corporate venturing, andstrategic renewal (see Figure 1). While there are many alliance types (e.g. joint produc-tion, minority equity alliances), three common types will be discussed in this paper: jointventures, R&D alliances, and learning alliances. These three types are not exclusive, asa joint venture may be formed for R&D or learning purposes (and hence an R&D orlearning alliance). In Table II the key features of various CE and alliance types are listed,based on which we will discuss the key issues in combining specific types of CE andalliance. While some of these issues are benefits of alliances, other issues are clearlypitfalls of alliances when combined with CE. Thus, alliances are more suitable to specificCE activities under certain conditions.

Innovation

Innovation is believed to be the most common and important aspect of CE (Covin andMiles, 1999). Both corporate venturing and strategic renewal draw from the potentialbenefits of new products, processes, and systems. Another key feature of innovation is itsknowledge orientation, as it deals with generating know-how for doing things differently.Innovation, however, generally has a low success rate and is therefore believed to havethe highest degree of risk among all business activities (Teece, 1992). Firms haveemployed various approaches to improve the odds of innovation.

One such approach is to form strategic alliances for innovation. For instance, anR&D alliance can be formed to carry out joint research (Hardy et al., 2003). R&Dalliances can greatly assist innovation efforts, because firms are able to share R&D costand risk, as well as achieve economies of scale in research (Deeds and Hill, 1996). A keyfeature of R&D alliances is that partner firms contribute mostly intangible assets suchas technological know-how, although certain tangible resources such as equipments arealso necessary.

Since significant knowledge exposure is necessary in R&D alliances, firms face achallenge of protecting their distinctive competencies. It is found that partners oftensecretly appropriate firm-specific knowledge (Hamel, 1991). According to Gulati(1995a), the likelihood of opportunistic behaviour (e.g. appropriating technology) ishigher when joint R&D activities are involved. Thus, while R&D alliances reduce therisk in innovation, there is a risk in losing one’s distinctive competencies through col-laboration. Although all alliances are subject to this risk, it is of particular concern inR&D alliances.

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 131

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

Tab

leII

.C

orpo

rate

entr

epre

neur

ship

thro

ugh

stra

tegi

cal

lianc

es:k

eyis

sues

CE

activi

ties

Key

feat

ures

Allia

nce

type

s

Joi

ntve

ntur

esR

&D

allian

ces

Lea

rnin

gal

lian

ces

•Se

para

teen

titie

s•

Mos

tfo

rmal

stru

ctur

e•

Alig

ned

inte

rest

s

•C

ontr

ibut

eR

&D

-rel

ated

know

-how

•K

now

ledg

eex

posu

re•

Shar

eR

&D

outp

uts

•O

pen

know

ledg

eac

quis

ition

•A

bsor

ptiv

eca

paci

tyis

key

Inno

vatio

n•

Com

mon

aspe

ctof

CE

•K

now

ledg

e-or

ient

ed•

Low

succ

ess

rate

•In

tegr

ated

stru

ctur

em

eans

grea

ter

know

ledg

eex

posu

re•

Equ

itym

ayde

ter

oppo

rtun

ism

•Sh

ared

R&

Dco

stan

dri

sk•

Ris

kof

losi

ngdi

stin

ctiv

eco

mpe

tenc

ies

•H

ighe

rsu

cces

sra

teth

roug

hle

arni

ng•

Kno

wle

dge

acce

ssm

aybe

limite

dC

orpo

rate

vent

urin

g•

New

units

•N

ewbu

sine

sses

•So

me

stab

ility

isne

eded

•A

form

ofex

tern

alve

ntur

ing

•M

anag

eria

ldiffi

culty

•G

ener

ate

tech

nolo

gies

for

new

busi

ness

es•

Cho

ose

part

ners

inre

late

dbu

sine

sses

•L

earn

toen

ter

new

busi

ness

es•

Lea

rnin

gra

ces

lead

toin

stab

ility

Stra

tegi

cre

new

al•

Re-

depl

oyin

gre

sour

ces

•C

hang

eof

curr

ent

busi

ness

/app

roac

h

•U

nloa

dun

wan

ted

reso

urce

sor

obta

inke

yre

sour

ces

•Jo

int

vent

ures

asex

peri

men

ts

•Pr

ovid

ete

chno

logi

cal

foun

datio

nfo

rch

ange

•Sh

ared

tech

nolo

gym

eans

pote

ntia

lcom

petit

ion

•L

earn

from

part

ners

’ren

ewal

orin

dust

ryex

peri

ence

•U

ncer

tain

know

ledg

eap

plic

abili

ty

B-S. Teng132

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

As such, when innovation is carried out through an R&D alliance, a firm may beunknowingly creating future competitors with similar technological capabilities. Thereare a few steps firms may take to lower this risk. First, the trustworthiness of partner firmsis critical (Barney and Hansen, 1994). Firms with a good reputation from previousalliances are far less likely to secretly appropriate technology. Second, firms need torigorously guard against opportunistic behaviour in R&D alliances (Parkhe, 1993).Possible control mechanisms may include detailed specification, close monitoring, andlimited access.

To help deter opportunistic knowledge acquisition, firms may choose joint ventures astheir preferred alliance structure for innovation. A joint venture is a separate entityjointly owned by two or more firms ( Pearce, 2001; Yan and Gray, 2001). Among varioustypes of alliances, joint ventures are the most formal and integrative type. Joint venturepartners’ shared equity may align their interests and make them less likely to behaveopportunistically (Gulati, 1995a). Since equity arrangements are more difficult to dis-solve, firms may find themselves more embedded in joint ventures and hence become lessopportunistic (Das and Teng, 2000). In addition, equities can be used as collateralsagainst the cheating party, which again reduce the incentive of unauthorized knowledgeacquisition. Thus, although there is a higher degree of knowledge exposure in a jointventure setting, firms may still feel more secure with equity arrangements.

Furthermore, firms may also use learning alliances to advance innovation (seeTable II). Learning alliances are formed primarily for partner firms to learn from eachother’s knowledge base (Khanna et al., 1998). A learning alliance serves as the premisethrough which a firm intensively interacts with its partners and gradually absorbs theirknowledge (Doz, 1996). In contrast to opportunistically stealing knowledge, knowledgeacquisition in a learning alliance is open, specified, and encouraged. Apparently, whenit is possible to learn from others, the success rate of innovation efforts would increasedramatically. However, a common issue in learning alliances is that knowledge accesstends to be limited: firms usually allow learning to take place only in specified areasunrelated to their distinctive competencies.

The key to successful learning lies in firms’ learning capability (Lam, 2003;Stopford and Baden-Fuller, 1994), or absorptive capacity. Absorptive capacity refers to‘the ability of a firm to recognize the value of new, external information, assimilate it,and apply it to commercial ends’ (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990, p. 128). It is a criticalability to overcome various knowledge transfer barriers such as knowledge embedded-ness, tacitness, and organizational distance (Cummings and Teng, 2003). Absorptivecapacity can be developed over time and through past experience. Thus, firms withrich alliance experience tend to have stronger absorptive capacity and benefitmore from additional alliances (Gulati, 1995b). Theorists further argue that absorptivecapacity can be ‘partner-specific’ in a dyadic relation, and this capacity is critical indetermining whether a cooperative alliance creates value (Dyer and Singh, 1998; Laneand Lubatkin, 1998).

Proposition 7: Strategic alliances are more suitable for innovation efforts when (1)interfirm learning does not erode the firm’s distinctive competencies, and (2) the firmhas strong absorptive capacity to overcome knowledge transfer barriers.

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 133

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

Corporate Venturing

Corporate venturing involves creating or acquiring new units in order to generate newbusinesses (Chesbrough, 2002; Dougherty, 1995). The two elements of corporate ven-turing are new ventures and new businesses, both of which imply significant resourcecommitments. Generally a large investment is needed before a new business can generatepositive cash flow or income. Thus, corporate venturing tends to create some resourcetensions (or gaps) in the firm. As noted earlier, Wingspanbank.com as a corporateventure consumed more than one hundred million dollars in investment from the parentfirm Bank One during the first year of its operation.

Resource gaps created by corporate venturing can be filled through alliances such asjoint ventures (Child and Yan, 2003). In fact, joint ventures are a form of externalventuring because they represent a new and separate organization – jointly created incooperation with other firms. Through joint ventures, a firm is able to venture into newbusinesses and, not be limited by its current resources. Joint ventures are an effective wayto fill resource gaps of all types (both tangible and intangible) by getting access to thoseresources most embedded in partner firms (Das and Teng, 2000). First, it is easier forpartners to pool various tangible assets in joint ventures. A separate organizationalstructure facilitates the physical integration of contributed tangible assets. Second, jointventures are believed to be the most effective alliance structure for transferring intangibleresources such as tacit knowledge because joint venture partners need to work closelytogether (Inkpen, 2000; Kogut, 1988).

Despite the benefits, joint ventures are known for being difficult to manage ( Fryxellet al., 2002) and tend to be unstable (Yan and Zeng, 1999). Many joint ventures arerestructured or even terminated before they have a chance to fully achieve the partnerfirms’ objectives. Of the many explanations for alliance instability, internal conflicts andchanging needs of partner firms are critical (Inkpen and Beamish, 1997). Althoughinstability is a common issue in all alliances and does not necessarily signal failure, it canbe problematic when a joint venture is used to implement corporate venturing. Thereason is that the purpose of corporate venturing is to generate new businesses for the firmthrough new ventures (Ellis and Taylor, 1987). Thus, corporate venturing often demandsa certain level of stability in order to establish the new unit in a new environment. Sucha long-term orientation and stability tend to be lacking in some joint ventures. Changingstructures and/or early termination of joint ventures tend to create difficulties for acontinued pursuit of opportunities in a new area. Thus, in order for a joint venture to bea successful corporate venture, the firm has to manage this issue of instability.

While joint ventures directly represent a form of corporate venturing, R&D alliancesand learning alliances can be used to help a corporate venture succeed. Firms may useR&D alliances to generate technologies that facilitate their entry into new businesses.Since the new technologies are intended to rival existing technologies in the industry,incumbents are often reluctant to participate in R&D alliances that lead to market entryby new competitors. Thus, partners for such R&D alliances would most likely be firmsfrom related industries.

Meanwhile, learning alliances help firms’ corporate venturing as they learn how toenter new businesses (Inkpen, 2000). Thus, firms look for partners who are already in the

B-S. Teng134

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

business. Through an alliance with incumbents, firms can most easily obtain capabilitiesrelevant in the new business. However, a potential problem with learning alliances istheir lack of stability. In fact, learning alliances could be the least stable type of alliancesdue to learning asymmetry between the partners. According to Inkpen and Beamish(1997), partner firms often differ in their learning ability and effectiveness. The partnerthat accomplishes its learning objectives first may use its superior bargaining power todemand a restructuring of the alliance. The result is a high level of instability. Thus,while joint ventures have the benefit of a formal structure, learning alliances are inher-ently less stable. Since learning alliances are likely to become a learning race (Hamel,1991; Khanna et al., 1998), caution should be exercised in using such alliances forcorporate venturing, which demands a certain level of stability.

Proposition 8: Strategic alliances are more suitable for corporate venturing efforts whenstability of the alliance can be achieved.

Strategic Renewal

Strategic renewal is a firm’s transformation in terms of changing its scope of business orstrategic approach (Zahra, 1996). The success of strategic renewal critically depends onobtaining new resources and capabilities. According to Guth and Ginsberg (1990, p. 6),strategic renewal is ‘the creation of new wealth through new combination of resources’.To re-deploy existing resources toward a different approach for doing business, a firmoften needs to introduce new elements into its resource profile (Floyd and Lane, 2000).While tangible resources may be needed to carry out new activities or develop a newcorporate image, intangible resources such as knowledge may be needed to formulate aturnaround or restructuring strategy.

Among the various alliance types, R&D alliances specialize in developing technologiesthat may form the foundation for strategic renewal. In many industries, new technologieshave the potential to change the way businesses are conducted. Examples include themini-mill technology in the steel industry and the Internet technology for the retailindustry. Thus, when R&D alliances lead to major innovations, they may also set thestage for strategic renewal. Nonetheless, a potential problem of this approach is thatpartners often need to share R&D outputs of the alliance. Thus, the firm does not haveexclusive rights to a technology that may become its distinctive competency. Sharingtechnologies can be tricky as the partner may deploy them in a way that leads to directcompetition (Hamel, 1991). Such a scenario increases the difficulty of one’s renewalefforts, as the ‘new’ approach may not be unique after all.

Generally, R&D alliances are not appropriate when technology exclusivity is impor-tant for strategic renewal. However, a firm may choose certain R&D areas for collabo-ration that are less sensitive to, or even in need of, shared technology ownership andtechnology dissemination. One such situation is when renewal efforts are related tosetting an industry standard (Teng and Cummings, 2002). Strategic renewal will be moresuccessful when an alliance helps spread the new technology and enhance its acceptabil-ity in the industry.

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 135

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

Meanwhile, learning alliances bring in new knowledge that is essential for strategicrenewal. A learning alliance is valuable because CE aims at promoting ‘organizationallearning that leads to the creation of new knowledge’ (Zahra et al., 1999, p. 173). A firmmay learn from its partners about a new way of doing business and thus achieve strategicrenewal. Thus, a desirable partner would be a firm with significant experience inrenewing itself or in employing the new approach that the firm wants to learn from. Forinstance, it makes sense to have General Electric (GE) as a partner to learn from itsrenewal experience (in transforming itself from a manufacturing-oriented firm to aservice-oriented firm) or its renowned Six-Sigma approach. However, the learningapproach is subject to the uncertainty of knowledge applicability, in part because knowl-edge is often embedded in its specific environment (Szulanski, 1996). Despite stronglearning efforts, good practices may not be generalized and replicated. Thus, successfulexperience of other firms may not be applicable to one’s own renewal efforts.

While R&D and learning alliances help provide renewal-oriented technology andknowledge, joint ventures benefit strategic renewal as they can be employed as anintermediate approach toward restructuring (Hagedoorn and Sadowski, 1999). Throughownership transfer in the venture, firms may acquire or unload resources in order torealign their existing businesses. Nanda and Williamson (1995) discuss how firms usejoint ventures as an incremental spin-off approach to reduce the difficulty of restructur-ing. Since slack or undesirable resources are first put into a jointly owned entity, there isno immediate divestiture decision to make. This approach gives management time tore-evaluate the value of resources before they are finally spun off.

In particular, when a straight divestiture does not get a good price, the unwanted assetsmay be used to form a joint venture. Once the venture is on track, the firm may suggestthe partner purchase the entire venture and expect better returns on the assets (Nandaand Williamson, 1995). In this sense, joint ventures serve as real options for both sides toavoid total commitment at the beginning and to have the option of buying or selling ata more feasible time (Kogut, 1991). A real option gives the parties the right, but not theobligation, to take actions (i.e. buying and selling stakes in the venture) in the future (Foltaand Miller, 2002). For a similar risk-management purpose, joint ventures may also beused as experiments for firm-level strategic renewal efforts, especially when externalexpertise is needed. However, since the incremental approach takes time to execute,significant time pressure would make it inappropriate. Thus, ample time for strategicrenewal is a necessary condition for using alliances as real options.

Proposition 9: Strategic alliances are more suitable for strategic renewal efforts when (1)relevant knowledge and technology can be generalized and shared (such as for settingindustry standards), and (2) there is time for an incremental (or real options) approach.

CONCLUSION

Despite apparent overlaps, CE and strategic management remain separate research areas.In this paper, the two areas are brought together through a resource-based framework ofCE that emphasizes the role of strategic alliances in entrepreneurial activities. In terms oftheoretical implications, the paper makes several contributions to the literature.

B-S. Teng136

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

First, this paper represents one of the early attempts to extend an important strategytheory to the study of CE. RBV is arguably one of the most important theories instrategic management. RBV seems particularly pertinent to CE, which involves novelcombinations of resources in doing business. Many believe that the creative acquisitionand deployment of resources are the essence of entrepreneurship. The fact that RBV hasnot been adequately applied to CE is a manifestation of a lack of integration between CEand strategic management research. Thus, this paper fills a theoretical gap by examiningCE in light of a strategy theory.

For CE to truly benefit from a strategy theory, the theory has to be systematicallyapplied. To this end, two RBV concepts – ‘resource gaps’ and ‘resource conditions’ – areemployed. Resource gaps are a new concept developed in this paper, while resourceconditions are a well-established concept in RBV literature. Since CE activities are aboutpursuing opportunities and growth without much regard to current resource endow-ment, an entrepreneurial firm is likely to face resource gaps. This new concept issignificant as it represents a key resource-based difference between entrepreneurial firmsand other firms.

The second contribution of the paper is that CE is linked with an increasingly popularstrategy – strategic alliances, which, like CE, are critical in a hypercompetitive environ-ment that demands a high level of flexibility. A combination of the two and an under-standing of their interaction are, therefore, important and worthwhile. To this end, theresource gap concept helps link CE efforts and strategic alliances. Since CE activitiestend to create resource gaps, strategic alliances are a logical option used to fill theseresource gaps. We compare alliances to a complete list of other options in filling resourcesgaps – internal development, market transactions, and acquisitions. In addition, wediscuss how various alliance types (i.e. joint ventures, R&D alliances, and learningalliances) may facilitate various CE activities. Such an examination offers a more fine-tuned understanding of their relationships, including when and how various alliancesbenefit specific CE activities.

Finally, we argue that a strategic alliance does not necessarily create value in CE. Weexamine when and how alliances help CE achieve competitive advantage and createvalue. We propose a contingency framework of CE and strategic alliances based on theresource-based view of competitive advantage. Essentially, RBV suggests that competi-tive advantage is created only if certain resource conditions are met. These conditionsinclude heterogeneity, ex ante and ex post limits to competition, and imperfect mobility.To meet these conditions in the resource acquisition process, strategic alliances should beused to fit the specific needs of CE. For example, it is argued that a strategic alliancefocused on first-mover advantage is valuable for CE to meet the condition ex post limitsto competition. This contingent examination deepens our understanding of the interac-tive relationship between CE and strategic alliances.

It would be interesting to compare the proposed RBV framework of CE with severaltraditions in economics that are related to CE, such as the industrial organization (IO),Chamberlinian, and Schumpetarian economics. To the extent RBV focuses on theinternal sources of competitive advantage, the proposed model is least similar to IOeconomics, which sees strategies as a response to the structure of the industry in whichthe firm competes (Porter, 1980). In contrast, RBV is closely related to Chamberlinian

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 137

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

economics, which focuses on the impact of unique resources of firms (such as reputation)on strategies (Barney, 1986). In a complementary manner, the proposed frameworkmaintains that the success of CE activities is based on filling one’s unique resource gaps.Finally, our model has deep roots in Schumpetarian economics that views above-normalreturns coming from ‘creative destruction’, or innovative combinations of resources thatoverwhelm one’s competitors. In our model, competitive advantage indeed comes fromCE activities that make competitors hard to imitate or follow.

The paper has several implications for future research. Since RBV is an importantperspective for understanding CE activities, a host of additional questions relating toRBV can be asked. For example, how does the resource profile of a firm affect its CEactivities? What resource characteristics encourage or discourage CE activities? Does thenature of resource gaps influence the type of CE activities? Answering these questionswould help develop a comprehensive resource-based theory of CE that is missing in theliterature.

Besides, while strategic alliances facilitate entrepreneurial efforts in the market place,their possible negative impact on CE should be examined. That is, what are the risks andpitfalls of using strategic alliances to achieve CE? Will a reliance on external resources(via strategic alliances) diminish a firm’s ability to develop resources internally in thefuture? How should strategic alliances, acquisitions, market transactions, and internaldevelopment of resources be collectively employed for more effective CE? Futureresearch that attempts to answer these questions will help achieve a balanced view ofcombining CE and strategic alliances.

NOTE

*I would like to thank Mark Heuer and Kalpana Seethepalli for reviewing this article, which was presentedat the 2003 Academy of Management annual meeting in Seattle, USA.

REFERENCES

Ahuja, G. (2000). ‘The duality of collaboration: inducements and opportunities in the formation of interfirmlinkages’. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 317–43.

Alvarez, S. A. and Barney, J. B. (2002). ‘Resource-based theory and the entrepreneurial firm’. In Hitt,M. A., Ireland, R. D., Camp, S. M. and Sexton, D. L. (Eds), Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating a NewMindset. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 89–101.

Barney, J. B. (1986). ‘Types of competition and the theory of strategy: toward an integrative framework’.Academy of Management Review, 11, 791–800.

Barney, J. (1991). ‘Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage’. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120.Barney, J. B. and Hansen, M. H. (1994). ‘Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage’. Strategic

Management Journal, 15, Winter Special Issue, 175–216.Barringer, B. R. and Bluedorn, A. C. (1999). ‘The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and

strategic management’. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 421–44.Barringer, B. R., Jones, F. F. and Lewis, P. S. (1998). ‘A qualitative study of the management practices of

rapid-growth firms and how rapid-growth firms mitigate the managerial capacity problem’. Journal ofDevelopmental Entrepreneurship, 3, 97–122.

Birkinshaw, J., Bresman, H. and Hakanson, L. (2000). ‘Managing the post-acquisition integration process:how the human integration and task integration processes interact to foster value creation’. Journal ofManagement Studies, 37, 1–32.

Block, Z. and MacMillan, I. C. (1993). Corporate Venturing: Creating New Businesses within the Firm. Boston, MA:Harvard Business School Press.

B-S. Teng138

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

Borch, O. J., Huse, M. and Senneseth, K. (1999). ‘Resource configuration, competitive strategies, andcorporate entrepreneurship: an empirical examination of small firms’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,24, 49–70.

Brown, T. E., Davidson, P. and Wiklund, J. (2001). ‘An operationalization of Stevenson’s conceptualizationof entrepreneurship as opportunity-based firm behavior’. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 953–68.

Brush, C. G. and Chaganti, R. (1997). ‘Cooperative strategies in non-high-tech new ventures: an exploratorystudy’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21, 37–54.

Brush, C. G, Greene, P. G. and Hart, M. M. (2001). ‘From initial idea to unique advantage: the entrepre-neurial challenge of constructing a resource base’. Academy of Management Executive, 15, 64–78.

Burgelman, R. A. (1983). ‘Corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management: insights from a processstudy’. Management Science, 29, 1349–63.

Chen, M.-J. (1996). ‘Competitor analysis and interfirm rivalry: toward a theoretical integration’. Academy ofManagement Review, 21, 100–34.

Chesbrough, H. W. (2002). ‘Making sense of corporate venture capital’. Harvard Business Review, 80, 90–9.Chi, T. (1994). ‘Trading in strategic resources: necessary conditions, transaction cost problems, and choice

of exchange structure’. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 271–90.Child, J. and Yan, Y. (2003). ‘Predicting the performance of international joint ventures: an investigation in

China’. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 283–320.Cohen, W. M. and Levinthal, D. A. (1990). ‘Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and

innovation’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128–52.Cool, K. O. and Schendel, D. (1987). ‘Strategic group formation and performance: the case of the US

pharmaceutical industry, 1963–1982’. Management Science, 33, 1102–24.Cooper, A. C. (2002). ‘Networks, alliances, and entrepreneurship’. In Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., Camp,

S. M. and Sexton, D. L. (Eds), Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating a New Mindset. Oxford: BlackwellPublishers, 203–17.

Covin, J. G. (1991). ‘Entrepreneurial versus conservative firms: a comparison of strategies and performance’.Journal of Management Studies, 28, 439–62.

Covin, J. G. and Miles, M. P. (1999). ‘Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advan-tage’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 47–63.

Covin, J. G. and Slevin, D. P. (1989). ‘Strategy management of small firms in hostile and benign environ-ments’. Strategic Management Journal, 10, 75–87.

Covin, J. G. and Slevin, D. P. (1991). ‘A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior’. Entrepre-neurship Theory and Practice, 16, 7–24.

Cummings, J. L. and Teng, B. (2003). ‘Transferring R&D knowledge: the key factors affecting knowledgetransfer success’. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 20, 39–68.

Das, T. K. and Teng, B. (2000). ‘A resource-based theory of strategic alliances’. Journal of Management, 26,31–61.

Das, T. K. and Teng, B. (2001). ‘Trust, control, and risk in strategic alliances: an integrated framework’.Organization Studies, 22, 251–83.

Das, T. K. and Teng, B. (2002). ‘The dynamics of alliance conditions in the alliance development process’.Journal of Management Studies, 39, 725–46.

D’Aveni, R. A. (1994). Hypercompetition: Managing the Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering. New York: Free Press.Deeds, D. L. and Hill, C. W. L. (1996). ‘Strategic alliances and the rate of new product development: an

empirical study of entrepreneurial firms’. Journal of Business Venturing, 11, 41–55.Dess, G. G., Lumpkin, G. T. and Covin, J. G. (1997). ‘Entrepreneurial strategy making and firm perfor-

mance: tests of contingency and configuration models’. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 677–95.Dickson, P. H. and Weaver, K. M. (1997). ‘Environmental determinants and individual-level moderators of

alliance use’. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 405–25.Dierickx, I. and Cool, K. (1989). ‘Asset stock accumulation and the sustainability of competitive advantage’.

Management Science, 35, 1504–13.Dollinger, M. J. and Golden, P. A. (1992). ‘Interorganizational and collective strategies in small firms:

environmental effects and performance’. Journal of Management, 18, 695–716.Dougherty, D. (1995). ‘Managing your core incompetencies for corporate venturing’. Entrepreneurship Theory

and Practice, 19, 113–35.Doz, Y. L. (1996). ‘The evolution of cooperation in strategic alliances: initial conditions or learning

processes?’. Strategic Management Journal, 17, Summer Special Issue, 55–83.Doz, Y. L. and Hamel, G. (1998). Alliance Advantage: The Art of Creating Value through Partnering. Boston, MA:

Harvard Business School Press.

Corporate Entrepreneurship Activities 139

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

Dyer, J. H. (1996). ‘Specialized supplier networks as a source of competitive advantage: evidence from theauto industry’. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 271–92.

Dyer, J. H. and Singh, H. (1998). ‘The relational view: cooperative strategy and sources of interorganiza-tional competitive advantage’. Academy of Management Review, 23, 660–79.

Eisenhardt, K. M. and Schoonhoven, C. B. (1996). ‘Resource-based view of strategic alliance formation:strategic and social effects in entrepreneurial firms’. Organization Science, 7, 136–50.

Ellis, R. J. and Taylor, N. T. (1987). ‘Specifying entrepreneurship’. In Churchill, N. C., Hornaday, J. A.,Kirchhoff, B. A., Krasner, O. J. and Vesper, K. H. (Eds), Frontiers of Entrepreneurial Research. Wellesley,MA: Babson College, 527–41.

Floyd, S. W. and Lane, P. J. (2000). ‘Strategizing throughout the organization: managing role conflict instrategic renewal’. Academy of Management Review, 25, 154–77.

Folta, T. B. and Miller, K. D. (2002). ‘Real options in equity partnerships’. Strategic Management Journal, 23,77–88.

Fryxell, G. E., Dooley, R. S. and Vryza, M. (2002). ‘After the ink dries: the interaction of trust and controlin US-based international joint ventures’. Journal of Management Studies, 39, 865–86.

Golden, P. A. and Dollinger, M. (1993). ‘Cooperative alliances and competitive strategies in small manu-facturing firms’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17, 43–56.

Grant, R. M. (1991). ‘The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: implications for strategyformulation’. California Management Review, 33, 114–35.

Grant, R. M. and Baden-Fuller, C. (2004). ‘A knowledge accessing theory of strategic alliances’. Journal ofManagement Studies, 41, 61–84.

Greene, P. G. and Brown, T. E. (1997). ‘Resource needs and the dynamic capitalism typology’. Journal ofBusiness Venturing, 12, 161–73.

Greene, P. G., Brush, C. G. and Hart, M. M. (1999). ‘The corporate venture champion: a resource-basedapproach to role and process’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23, 103–22.

Gulati, R. (1995a). ‘Does familiarity breed trust? The implication of repeated ties for contractual choice inalliances’. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 85–112.

Gulati, R. (1995b). ‘Social structure and alliance formation patterns: a longitudinal analysis’. AdministrativeScience Quarterly, 40, 619–52.

Guth, W. D. and Ginsberg, A. (1990). ‘Guest editors’ introduction: corporate entrepreneurship’. StrategicManagement Journal, 11, Summer Special Issue, 5–15.

Hagedoorn, J. and Sadowski, B. (1999). ‘The transition from strategic technology alliances to mergers andacquisitions: an exploratory study’. Journal of Management Studies, 36, 87–107.

Hamel, G. (1991). ‘Competition for competence and inter-partner learning within international strategicalliances’. Strategic Management Journal, 12, Summer Special Issue, 83–103.

Hardy, C., Phillips, N. and Lawrence, T. B. (2003). ‘Resources, knowledge and influence: the organizationaleffects of interorganizational collaboration’. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 321–47.

Inkpen, A. C. (1998). ‘Learning and knowledge acquisition through international strategic alliances’. Academyof Management Executive, 12, 69–80.

Inkpen, A. C. (2000). ‘Learning through joint ventures: a framework of knowledge acquisition’. Journal ofManagement Studies, 37, 1019–44.

Inkpen, A. C. and Beamish, P. W. (1997). ‘Knowledge, bargaining power, and the instability of internationaljoint ventures’. Academy of Management Review, 22, 177–202.

Kaish, S. and Gilad, B. (1991). ‘Characteristics of opportunities search of entrepreneurs: sources, interests,general alertness’. Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 45–61.

Khanna, T., Gulati, R. and Nohria, N. (1998). ‘The dynamics of learning alliances: competition, coopera-tion, and relative scope’. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 193–210.

Kirzner, I. (1973). Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.Kogut, B. (1988). ‘Joint ventures: theoretical and empirical perspectives’. Strategic Management Journal, 9,

319–32.Kogut, B. (1991). ‘Joint ventures and the option to expand and acquire’. Management Science, 37, 19–

33.Lam, A. (2003). ‘Organizational learning in multinationals: R&D networks of Japanese and US MNEs in the

UK’. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 673–703.Lane, P. J. and Lubatkin, M. (1998). ‘Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning’. Strategic

Management Journal, 19, 461–77.Lee, C., Lee, K. and Pennings, J. M. (2001). ‘Internal capabilities, external networks, and performance: a

study on technology-based ventures’. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 615–40.

B-S. Teng140

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2006

Liberman, M. B. and Montgomery, D. B. (1988). ‘First-mover advantage’. Strategic Management Journal, 9,41–58.

Liberman, M. B. and Montgomery, D. B. (1998). ‘First-mover (dis)advantage: retrospective and link with theresource-based view’. Strategic Management Journal 19, 1111–25.

Lippman, S. A. and Rumelt, R. (1982). ‘Uncertain imitability: an analysis of interfirm differences inefficiency under competition’. Bell Journal of Economics, 13, 418–38.

Lumpkin, G. T. and Dess, G. G. (1996). ‘Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking itto performance’. Academy of Management Review, 21, 135–72.

Marino, L., Strandholm, K., Steensma, H. K. and Weaver, K. M. (2002). ‘The moderating effect of nationalculture on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strategic alliance portfolio exten-siveness’. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26, 145–60.

McGee, J. E. and Dowling, M. J. (1994). ‘Using R&D cooperative arrangements to leverage managerialexperience: a study of technology intensive new ventures’. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 33–48.

McGee, J. E., Dowling, M. J. and Megginson, W. L. (1995). ‘Cooperative strategy and new ventureperformance: the role of business strategy and management experience’. Strategic Management Journal, 16,565–80.

Miller, D. and Shamsie, J. (1996). ‘The resource-based view of the firm in two environments: the Hollywoodfilm studios from 1936 to 1965’. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 519–43.

Mowery, D. C., Oxley, J. E. and Silverman, B. S. (1996). ‘Strategic alliances and interfirm knowledgetransfer’. Strategic Management Journal, 17, Winter Special Issue, 77–91.

Nanda, A. and Williamson, P. J. (1995). ‘Use joint ventures to ease the pain of restructuring’. Harvard BusinessReview, 73, 119–28.

Osterland, A. (1999). ‘Nothing but net; Bank One’s Wingspan leaves bricks and mortar behind’. BusinessWeek, 2 August, 72.

Park, C. (2002). ‘The effects of prior performance on the choice between related and unrelated acquisitions:implications for the performance consequences of diversification strategy’. Journal of Management Studies,39, 1003–19.

Parkhe, A. (1993). ‘Strategic alliance structuring: a game theory and transaction cost examination ofinterfirm cooperation’. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 794–829.

Pearce, R. J. (2001). ‘Looking inside the joint venture to help understand the link between inter-parentcooperation and performance’. Journal of Management Studies, 38, 557–82.