Cornwall’s Trans-Peninsular · Wales, Ireland, Isle of Man, also the Galloway and Solway...

Transcript of Cornwall’s Trans-Peninsular · Wales, Ireland, Isle of Man, also the Galloway and Solway...

BAR B653

2020

BORLA

SE

Cornw

all’s Trans-Peninsular Route: Socio-Economic and Cultural C

ontinuity across the Cam

el/Fowey C

orridor

Cornwall’s Trans-Peninsular Route: Socio-Economic and Cultural Continuity across the Camel/Fowey Corridor

Mark Borlase

‘The Way of Saints’ from the Roman period to AD 700

B A R B R I T I S H S E R I E S 6 5 3 2 0 2 0

Published in 2020 by BAR Publishing, Oxford

BAR British Series 653

Cornwall’s Trans-Peninsular Route: Socio-Economic and Cultural Continuity across the Camel/Fowey Corridor

ISBN 978 1 4073 5476 7 paperbackISBN 978 1 4073 5618 1 e-format

doI https://doi.org/10.30861/9781407354767

© Mark Borlase 2020

Cover Image An impressionistic bird’s-eye Camel/Fowey corridor. Created by Mark and Kyle Borlase.

The Author’s moral rights under the 1988 UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act are hereby expressly asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be copied, reproduced, stored, sold, distributed, scanned, saved in any form of digital format or transmitted in any form digitally, without the written permission of the Publisher.

Links to third party websites are provided by BAR Publishing in good faith and for information only. BAR Publishing disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third-party website referenced in this work.

BAR titles are available from:

BAR Publishing 122 Banbury Rd, Oxford, ox2 7Bp, uk emaIl [email protected] phoNe +44 (0)1865 310431 Fax +44 (0)1865 316916 www.barpublishing.com

Borlase_title verso.indd 2Borlase_title verso.indd 2 23-03-2020 12:31:0723-03-2020 12:31:07

ix

ContentsList of Figures ................................................................................................................................................................... xvList of Tables .................................................................................................................................................................... xxiNote on Conventions ...................................................................................................................................................... xxii

1. Research Scope and Context ......................................................................................................................................... 1Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 1Research Scope and Context ........................................................................................................................................... 1

Topographical Setting, Isolation – Insulation – Identity ............................................................................................ 3Rationale Behind a Trans-Peninsular Route ............................................................................................................... 4Research Aims ............................................................................................................................................................ 4General Objectives of the Study ................................................................................................................................. 4

2. General Methodology and Approaches ........................................................................................................................ 7Approaches ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7Toponymic Evidence ....................................................................................................................................................... 7Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................... 8

The Hypothesis for a Route: Marine Environment v Overland Route ....................................................................... 8Tangible Evidence ...................................................................................................................................................... 8Supporting Evidence and Secondary Sources ............................................................................................................ 8A Thematic Approach Through Settlement and Overview of Research Sites ............................................................ 9Excavation .................................................................................................................................................................. 9

3. Out on a Limb: The Geomorphology of Cornwall, the Atlantic Climatic Influence and the Archaeological Context of the Study Period .....................................................................................................11

Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 11The Geomorphology of Cornwall ............................................................................................................................ 11Coastline Changes and Sea-Level Rises for the Camel and Fowey Estuaries ......................................................... 11

Cultural Aspects: Settlement Morphologies – a Discussion ......................................................................................... 12Enclosures: Diverse Typologies ............................................................................................................................... 13Socio-Political Dynamics and Identity in Settlement............................................................................................... 14Open Settlement ....................................................................................................................................................... 15Roman Military Influence in Cornwall and the Corridor ......................................................................................... 15Post-Roman Change in Settlement Pattern – Background to Social Change with Elements of Continuity Through Ceramics .............................................................................................................. 18Beach Sites ............................................................................................................................................................... 19Christianity ............................................................................................................................................................... 20Previous Archaeological Work ................................................................................................................................. 20

Major Sites Mentioned in this Study ............................................................................................................................. 20Trethurgy .................................................................................................................................................................. 20Carvossa ................................................................................................................................................................... 21Kilhallon ................................................................................................................................................................... 21Gwithian ................................................................................................................................................................... 21Tintagel ..................................................................................................................................................................... 22

Contemporary Inter-Trade Routes with Cornwall ........................................................................................................ 22Late Iron Age ............................................................................................................................................................ 22Trade Routes in the Roman Period ........................................................................................................................... 24Trade Routes in the Post-Roman Period .................................................................................................................. 25

4. The Camel and Fowey Corridor in Its Contemporary Setting: Tin, ‘Maritima’ and the Theory Underpinning a Cross-Peninsular Route ............................................................................................ 29

The Cassiterides: Cornwall in Late Prehistoric and Proto-Historic Times to ‘Invasion’ AD 43 .................................. 29Tin: The Contemporary Evidence ................................................................................................................................. 30Naval Matters ................................................................................................................................................................ 31Difficulties of Sailing the Celtic Sea and Wreck Evidence ........................................................................................... 33

02-Contents.indd 902-Contents.indd 9 23-03-2020 12:34:2423-03-2020 12:34:24

x

Cornwall’s Trans-Peninsular Route

Rounding the ‘Parte Occidentale’ ................................................................................................................................. 35Summary of Maritime Perspectives: Sea V Land – Validation of the Route Theory.................................................... 37

5. Camel and Fowey Corridor: Late Iron Age and Roman Periods............................................................................ 39Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 39Communications to and Across the Corridor: Signals of Evidence Through Fieldwork .............................................. 39

All Roads Lead to Minerals...................................................................................................................................... 39High Cliff .................................................................................................................................................................. 41East Leigh ................................................................................................................................................................. 43Pabyer Point ............................................................................................................................................................. 44Sites in Common ...................................................................................................................................................... 47

Research Findings: Settlement and Roman Involvement in the Corridor..................................................................... 49Kingswood Round .................................................................................................................................................... 49Lestow ...................................................................................................................................................................... 51Restormel ................................................................................................................................................................. 55Nanstallon Fort ......................................................................................................................................................... 58

Monetary Systems, Economy and Coin Evidence Across the Corridor ....................................................................... 59Continuity and Change: Independence Through Obdurate Traditionalism or Economic and Peripheral Determinism and Latent Romanitas .................................................................................... 62

6. The Corridor as a Christianised Landscape: of Saints, Lanns, Dedications and Memorial Pillars .................... 67Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 67Byzantine Connections.................................................................................................................................................. 67Continuity of Polity ....................................................................................................................................................... 68Christianity’s Influence ................................................................................................................................................. 68Memorial Pillars ............................................................................................................................................................ 69

Stones Through Time: Enlightenment ...................................................................................................................... 69Seaways of the Saints, Hagiographies and their Mark on the Landscape ..................................................................... 71

Saints Through the Corridor ..................................................................................................................................... 73Sampsonis: Hagiography Considered, Lanow, St Sampson Church and Langorthou .................................................. 75Place-Name Distribution Analysis with Lann Elements and Saint Dedications .......................................................... 84

7. East Camel Estuary Case Study: Settlement Sites, Continuity and Change in The Landscape .......................... 87Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 87Locational and Settlement Description ......................................................................................................................... 87Notes on Fieldwork from The Settlement Study Sites .................................................................................................. 88

Carruan ..................................................................................................................................................................... 88Middle Amble ........................................................................................................................................................... 92

Daymer Bay and Hinterland.......................................................................................................................................... 95St Enodoc and Trebetherick ..................................................................................................................................... 98Trebetherick ............................................................................................................................................................ 100Porthilly .................................................................................................................................................................. 101Lanow ..................................................................................................................................................................... 102Tregays on The Fowey River ................................................................................................................................. 103

Discussion ................................................................................................................................................................... 106Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 110

8. Discussion: Socio-Economic Dynamics, Settlement and Continuity ......................................................................111Site Maps ......................................................................................................................................................................111The Trans-Peninsula Land Route or the Longer Precarious Sea Passage? ..................................................................111Tangible Route Evidence ........................................................................................................................................... 113Evidence for Use of the Corridor as a Route and Exploitation of Resources ............................................................. 119Settlement Development, Form and Place in the Landscape and Outside Influences to AD700 ................................ 121Population ................................................................................................................................................................... 122Settlement Socio-Economic ....................................................................................................................................... 123Pushing Back the Boundaries: Current Perceptions Contradicted – Security Through Tin? ...................................... 124A Borderline Question: Roman Involvement and Romanitas ..................................................................................... 126Roman Interaction Through Design ............................................................................................................................ 126Absence of Roman Infrastructure, Continuity and Identity ........................................................................................ 128

02-Contents.indd 1002-Contents.indd 10 23-03-2020 12:34:2423-03-2020 12:34:24

xi

Contents

Economy and Transition ............................................................................................................................................. 131Pottery Via the Atlantic Seaways: Tintagel’s Influence on the Fowey and Camel Corridor ....................................... 131The Decline of Pottery Imports in the Corridor: Precursor to Social Change? .......................................................... 136

Changes in Settlement and Social Structure........................................................................................................... 137Early Christianity in the Corridor: What Can be Learnt From Fieldwork and Can a Correlation be Found to Early Literary Evidence? ........................................................................................... 138

9. Conclusions: Exploring The Social Dynamics Behind a Trans-Peninsular Route ............................................... 141Roman Interaction ....................................................................................................................................................... 141Socio-Economy ........................................................................................................................................................... 142The Early Medieval Corridor and Christianity ........................................................................................................... 142Settlement .................................................................................................................................................................... 142Continuity .................................................................................................................................................................... 143The Corridor – Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 144Scope for Further Research ......................................................................................................................................... 144

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................................... 145Websites ...................................................................................................................................................................... 159Ancient Sources .......................................................................................................................................................... 159

02-Contents.indd 1102-Contents.indd 11 23-03-2020 12:34:2423-03-2020 12:34:24

1

1

Research Scope and Context

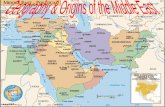

Figure 1.1. Cornwall, the Camel -Fowey study area outlined, major river systems and coastal features.

Introduction

This study is an exploration of a potential route across the breadth of the western part of the south west peninsula, which was formerly part of Dumnonia and is today the county of Cornwall. Essentially, the area under investigation encompasses a primary point on the south west peninsula coast at which it is feasible to make a land crossing with comparative ease, from the east, the north, or southern seaway approaches. The study sets out to determine the rationale behind how a potential trans-peninsular route may have evolved, its importance in the context of the wider Atlantic community, and how it influenced society and settlement from the Later Iron Age, but primarily the Roman period to AD 700.

Research Scope and Context

The route across Cornwall, is formed by the Fowey and Camel River valleys, which incise deep into the peninsula to nearly meet at its centre. Being linked by a short landbridge, the rivers provide accessibility to both the north and south coasts. Either side of the lower courses

of the two rivers are the two granite marilyns of Bodmin Moor to the east, and Hensbarrow Moors (312m) to the west. This geographical area is henceforth referred to as the ‘corridor’. At this point of the South West peninsula, the promontory that forms Cornwall narrows to around 30 kilometres. To the east of the corridor, the topography widens considerably with high moorland expanses. Only twenty kilometres east of the study area, the peninsula doubles in width. From the Fowey River mouth westward, there are some 125 kilometres to Land’s End along the south coast, and another 102 kilometres along the north coast from here to the mouth of the Camel. Utilising the rivers with a short land crossing, avoids well over 225 kilometres of the hazardous circuitous sea passage (Figure 1.2). There are many variables to consider with coastal passage-making, but under sail, the most direct course is rarely an option with distances potentially increasing by as much as fifty per cent.

The Cornish peninsula is strategically positioned on the Western Seaways in the Prehistoric and proto-historic periods. Shipping from the Mediterranean or Spain, for example, would progress north, past Brittany into the

CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 1CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 1 23-03-2020 12:45:4723-03-2020 12:45:47

2

Cornwall’s Trans-Peninsular Route

Mare Austrum, and have to proceed around Cornwall into the Mare Occidentale, to approach Wales and destinations further north. Thus, the western seaways rendered transport and cultural contacts to be possible between the Mediterranean, Iberian, Armorican and Gallic worlds to the inhabitants of the northern Celtic seaboards of Wales, Ireland, Isle of Man, also the Galloway and Solway peninsulas. Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly were therefore strategically situated at the hub of the of the Atlantic sea-routes.

It is only natural that there would have been a tendency to avoid the precarious sea passage around Land’s End and the Lizard peninsula. The navigator must cope with notoriously turbulent seas off Land’s End, where St Georges Channel meets the Atlantic and the English Channel creating ‘confused’ seas, even in relatively benign conditions. Furthermore, the complete absence of easy entry (especially in high seas) sheltered havens quashes contingency for safety in a state of encroaching weather deterioration. This research investigates the primary trans-peninsula corridor formed by the safe havens of the Fowey and Camel estuaries, and the associated communication links by road and river

between the two rivers. In doing so, the findings from the research will afford an opportunity to observe society through exploring its settlement patterns, the question of continuity through its material culture, how it impacted on the socio-economics of the region, and how this may have affected the identity of the populous.

Between Falmouth on the South Coast, around the Lizard, Land’s End and the full length of the North Coast there is some 100 nautical miles to the Camel estuary. The lack of safe refuge (Hayle and the Gannel are both very narrow and tidal) makes passage-making treacherous in inclement seagoing conditions. With the above issues duly considered, is a land crossing a more attractive option across Cornwall, and how does this alternative reflect in the archaeology?

The Roman influence and connection with Cornwall stems back to the pre-invasion Late Iron Age, with trading networks and movements of people (Henderson 2007, Cunliffe 1982, 1984, 1988a, 1998, 2001). There is a general dearth of information from the Roman period in Cornwall, partly due to a relative void in characteristic Roman material culture. Consequently, compared to the

Figure 1.2. February 8th, 2016 at 1430 hours, from Cligga Head, near St Agnes. Sea conditions deteriorate rapidly as winds veering north-west typically increase swinging to onshore. Now Beaufort severe gale 9 gusting storm 10, the frontal system has passed through. Only six hours earlier (a short time on a long passage) seas were ‘moderate’ to ‘rough’ in a manageable force 6 to 7, they are now building from ‘very rough’ to ‘high’ (spume blowing up to one kilometre inland and flying slate ‘missiles’ peel off cliff faces). The Gannel and Hayle rivers would be untenable in these conditions. The only safe haven is the Camel, around six hours distant; survival for small craft caught out not having read the potential weather signs, is desperate and perilous. Scenes such as this lend this passage notoriety. Photograph: author.

CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 2CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 2 23-03-2020 12:45:4723-03-2020 12:45:47

3

Research Scope and Context

remainder of England and Wales, relatively little work has been carried out. This has resulted in a somewhat vacuous picture of the Roman impact on Cornwall and the responses of the Cornish populous to Roman interests. Apart from two Roman forts, Nanstallon excavated in the 1970s by Fox and Ravenhill (1972) and the more recently confirmed fort at Restormel (Thorpe 2007), very little is known about the Roman involvement of west Dumnonia, and any contribution to enlighten on the overall picture is invaluable. The identity of this generally insular society, and their apparent obduracy to retain former traditions and cultures, generally resisting social change potentially brought in by overseas influence, is renowned. In the post-Roman period, whilst society continued to demonstrate insularity and elements of continuity, there is significant evidence for an introduction of Continental cultural influences.

This study investigates the impact of Roman contact with the communities of far west Dumnonia and offers to the record important material regarding Roman interaction, for not just Cornwall, but for comparison with similar peripheral provincial areas. The study follows on into the post-Roman period to identify patterns of change or continuation. In order to achieve a meaningful contribution to the clarification of influences on the populous, a thematic approach centred on settlement involving a series of micro-case studies will feature, spanning the period 200 BC to AD 700. From these it is hoped to draw out essential facts into the various components of the study body. Within the spectrum of settlement study in Cornwall, there is a good degree of knowledge of enclosed settlement, but our understanding of open settlement, spatially or quantifiably, to date is miniscule. Any research will augment the record for this period and help sharpen what is a blurred picture of society at this time, helping to alleviate the void in the data-set to some extent, simultaneously providing a contribution to Cornish archaeology.

The various components of this study on communications and society in Cornwall, surrounding the Roman period, will create a holistic framework of information on which to hang further hypotheses and intellectual discussion within the broad scope of these elements.

Although concentrating on the Roman and post-Roman period, the study commences earlier, with contextual discourse on the pre-Roman period, involving one Late Iron Age micro-study designed to reinforce debate on later-period social structures. It was also important to construct a background to an argument made that, although there is little tangible evidence, there are nuances of established Roman trading networks, between the peoples west of the Tamar, and the external world in pre-conquest times. The cut-off date is AD 700, as it was by the year 698 that Christendom in Carthage fell to the Islamic Arab caliphate (McEvedy 1992, 34) effectively ceasing any Atlantic based Mediterranean trade contact, although this had probably declined many years beforehand.

Topographical Setting, Isolation – Insulation – Identity

The geomorphology of the far South West peninsula consists of a string of granite batholiths, two of the largest being Dartmoor and Bodmin Moor, all with their surrounding metamorphic geologies. The River Tamar rises six kilometres from the north coast, cutting south between these two highland areas, creating a natural boundary that all but severs the peninsula. Today the river forms the modern border for Cornwall, as it has done as early as the tenth century, probably earlier (Doble 1997, 6). The result is the ‘topographical truncation’ of society from its neighbouring regions of south-western Britain, creating what most regard as culturally and historically distinct identities (Quinnell 2004; Holbrook SWARF 2008, 157). This is marked by the Brythonic form of insular linguistics, which has only recently died out as a primary language in the west a few centuries ago, although there is a now a ‘nationalistic’ revival. Cornwall is far more akin to that of Brittany, Wales and Ireland, which have shared linguistic, cultural and historical links, a thread that runs through this paper. This identity is apparent in the periods covered by the study, in that the archaeological and historical record shows that culture and society was disparate in very many ways from the rest of England. West Dumnonia was never as fully integrated into the Roman world as the remainder of southern and eastern England. If this was the case, why is it that the archaeology of the western area of Dumnonia does not demonstrate as greater Roman military presence as that of Wales or Brittany? Particularly, as the metamorphic sequencing around the granite extrusions, which run down the spine of Cornwall and the far West Devon are rich in minerals, including the comparatively rare mineral cassiterite.

The above factors are inextricably linked to the morphology and existence of the Camel and Fowey trans-peninsula route in that it potentially forms a communication corridor between the maritime Celtic spheres. In the development of political boundaries, rivers formed significant natural landscape features. In the south west peninsula, the River Parrett has been considered the boundary of Dumnonia, and just as the River Camel is the early boundary for the Hundreds of Cornwall, the River Tamar, can be expected to form a political sub-kingdom of Dumnonia (Dark 1994, 126). The Ravenna Cosmology written c 700 first mentions a place named Duro-Cornoviorum meaning fort of the Cornovii. Also, from around 700, Aldhelm describes a journey to Dumnonium through Cornubia (Padel, 2019). These are the earliest collective references recognising people west of the Tamar. The subject of ethnicity and the maritime influences of the ‘Cornovii’ entity of Dumnonia, (Todd 1987, 203; Thomas 2009), is exhaustive and beyond the limitations of this study. However, where it does arise, it has been assessed within the limits of the core subject. Similarly, an integral facet of this research concerns settlement study, providing evidence on the morphology of the route and is symbiotically related with the core theme. Although these ancillary subjects are inevitable to achieve the overall goal, it is recognised that they are involved

CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 3CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 3 23-03-2020 12:45:4823-03-2020 12:45:48

4

Cornwall’s Trans-Peninsular Route

and complex. It was therefore the intention of this study to deal with these aspects only as far as is necessary to complement and substantiate evidence for the fundamental research questions; intrinsically, to determine how a trans-peninsula route impacts upon the communities and society surrounding the route.

Focused research intends to stimulate new ideas on the physiognomies of the Roman and early medieval social dynamics across the seascape and landscape of Cornwall. Past studies have revealed a degree of evidence concerning society, but this contribution intends to assess the spectrum of evidence exposed by this body of research on Roman interaction, continuity or social change across the study period.

Rationale Behind a Trans-Peninsular Route

Extending well inland and connected by a short land bridge, the Camel and Fowey estuaries provide a conduit for communication between the north and south coasts. Preston-Jones notes that the rivers create a corridor of great strategic significance across mid-Cornwall. She believes it may be no coincidence that at its centre, Bodmin rose as the singular most important religious house in Cornwall (2013, 17). The alternative passage around the sea areas of Land’s End is notoriously hazardous for small shipping. Even today, the reputation of these waters has un-affectionately earned the ship ‘The RMV Scillonian III’ (plying between Penzance and the Isles of Scilly) the label of ‘the great white stomach pump’. In fact, the service ceases altogether between early November and mid-March largely due to sea conditions. The problems of ‘circumnavigation’ around the peninsula are manifold, but foremost, to be safe in any kind of strong wind, a square-rigged sailing ship would have to sail well out to sea for at least a mile, or even several miles, in order to gain safe sailing manoeuvrability. A modern-day disaster emphasised this when the nineteenth century-built brigantine, Maria Assumpta, foundered off the Rumps with loss of life whilst running out of sail room in 1995.

Thus, unless exceptionally fortunate, the vagaries of sailing round the ‘Parte Occidentale’ dictate that this is not just an ‘as the bird flies’ mileage, and an unfavourable wind is likely to be encountered at some stage of the passage. This may entail an extension of many nautical miles and hours, and can be hazardous when met with deteriorating conditions, particularly off headlands where the additional dangers of overfalls, enhanced tidal and wind effects, can all create difficulties.

Conversely, the safer riverine and portage route of the Camel and Fowey corridor is just thirty-three kilometres from shore to shore. It can be covered in daylight on horseback from Fowey to Padstow, or up to two days easy trekking by foot, equine pack animals, ox cart, even sledge with opportune trading potential on route. Trans-shipping cargoes further into the interior of the river system can

reduce overland portage considerably; between Restormel to Pendavey, just south of Wadebridge, the distance is only thirteen kilometres.

These navigational factors then, form the basis for the hypothesis for an evolving trans-peninsular route. This is examined, along with the corridor through which it passes, extracting associated derivative material, which can inform on the Romano-British society of west Dumnonia, informing on the question of cultural continuity, social dynamics and identity in the post-Roman period up to AD 700.

Research Aims

The intentions and aspirations of this work have been outlined in the above introductory passages and the process can be briefly summed up as follows:

• The study was designed to examine the notion that a trans-peninsular route existed across Cornwall utilising the Camel and Fowey Rivers and to assess and test the rationale and validity for its use for trade and commerce. Archaeological features across the corridor’s landscape were examined which advanced an understanding of settlement morphology, and informed on contemporary society, economy, and exploitation of resources. Finally, identifying if settlement may have differed, or be similar to, settlement patterns across west Dumnonia spatially and in character.

• Rivers form uncompromising focal landscape features, often physical divides between territories. Two Roman forts lie on the line of the Fowey and Camel raising the concept that a Roman frontier may exist (Thorpe 2007, 7). The study investigated this question and to what extent Roman involvement influenced indigenous society. Interconnected within this topic is the question of the dearth of Roman infrastructure across west Dumnonia, therefore an objective of this study was to explore and enlighten where possible this phenomenon. Accordingly, the question of the status of Roman interaction with the local populous was a subject of interest. Inter-twined with this is the complex study of identity, which was dealt with in a discursive manner where it arose.

• From research results obtained from this multi-period settlement study, it was possible to explore the phenomena of cultural continuity/change as well as socio-economic evidence through what was discovered from the material culture across the corridor.

General Objectives of the Study

To advance the physiognomies of settlement and social change in the Camel and Fowey environs, it was an objective to establish a broad chronology of the different genre of settlement, and where possible to determine the nature of the activity, character of the settlement and spatial patterning. Accordingly, to inform on the social and economic base and resource exploitation. This evidence

CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 4CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 4 23-03-2020 12:45:4823-03-2020 12:45:48

5

Research Scope and Context

helped explain the requirement and nature of a cross-peninsular route, as well as society as a whole throughout the different periods. In addressing these questions, it was then possible to place the settlement characteristics of the Camel and Fowey environs in context with the rest of west Dumnonia and identify contrasting or similar settlement patterns.

The Roman interaction with the native populous of Cornwall is still in the formative stages of understanding. With the two forts of Restormel and Calstock (on the Tamar), only recently added to the record to join the fort at Nanstallon and the villa at Magor, the Roman involvement is possibly greater than previously thought. In order to enquire into these Roman questions, examination of a number of Romano-British sites helped understand the use of the landscape across the corridor, thus use of the route. In this context, any material arising from research of this nature can then help us understand Roman contact with the indigenous society.

Cornwall’s National Mapping Programme has discovered several times more enclosures and features than has been previously understood to exist throughout Cornwall (Young 2012, 69–124). A recent paper discussing those identified in the Camel estuary environs (which are particularly rich in enclosures and crop marks), concluded stating that a number of questions, such as function of the enclosures and contemporaneity of any unenclosed roundhouses in association with them, remain unanswered (Young 2012, 110). It was therefore an objective of this study to investigate a selection of settlement sites and present a series of micro- and macro-case studies to help enlighten on these questions and their inter-relationship with the route. In order to address questions on phasing and inter-site contemporaneity, a programme of judicious excavation sampling and geophysics was a remit of this study. This allowed the issue of characterisation of enclosures and the differentiation between the generic term ‘round’ as enclosures or settlements to be engaged. Definitions will be dealt with later, but it was the intention that this study would further help in characterising enclosures, both in function and form. This has been carried out by surveying a sample of small enclosures to determine if there is a generic stock enclosure, or other form, that can be differentiated from an occupied round. This exercise not only helped inform on the function of a sample of small enclosures, but accordingly the socio-economic raison d’étre of their presence. The information arising, can then be inserted into the overall settlement pattern and morphology dynamics, reflecting on population levels, maritime settlement, trading status, and the importance of the Camel and Fowey corridor as a route. This will ultimately help us consider how well these river systems were used and how this reflected on settlement patterning. In summarising, did use of River Camel as a conveyance medium underpin the dense settlement of its environs? Thus, an objective was to understand how the route affected settlement or vice versa and if it was

affected in a significantly contextually different way from other areas.

CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 5CH01_pp001-006_v3.indd 5 23-03-2020 12:45:4823-03-2020 12:45:48

210mm WIDTH

BAR BRITISH SERIES 653

The Camel and Fowey rivers incise deeply into Cornwall, nearly meeting in the middle. This book is a landscape study of the Camel/Fowey corridor which forms a natural trans-peninsular portage route across Cornwall, avoiding circumnavigating the notoriously hazardous Land’s End sea route. The author investigates the effect this route had on society through micro and macro settlement studies involving an extensive programme of geophysical analysis. This has generated fresh insight into the socioeconomic and continuity dynamics of this part of Cornwall, together with the interaction between Romans and the indigenous population. The findings explore sociopolitical influences in the Roman period and cultural continuity into the post-Roman period.

Mark Borlase combines a family interest in history and archaeology with a personal interest in landscapes, environment, sailing, and ecology. These interests led to a journey which began with an evening course in GCSE archaeology and culminated in a PhD from the University of Bristol.

‘An entirely original approach that has produced a fantastic amount of detail … a “tour de force” in how to deal with landscape archaeological surveys.’

Professor Stephen Upex, University of Cambridge

11.7mm 210mm WIDTH

Printed in England

BAR B653

2020

BORLA

SE

Cornw

all’s Trans-Peninsular Route: Socio-Economic and Cultural C

ontinuity across the Cam

el/Fowey C

orridor

Cornwall’s Trans-Peninsular Route: Socio-Economic and Cultural Continuity across the Camel/Fowey Corridor

Mark Borlase

‘The Way of Saints’ from the Roman period to AD 700

B A R B R I T I S H S E R I E S 6 5 3 2 0 2 0

210 x 297mm_BAR Borlase CPI 11.7mm ARTWORK.indd All Pages210 x 297mm_BAR Borlase CPI 11.7mm ARTWORK.indd All Pages 30/3/20 10:58 PM30/3/20 10:58 PM