contents...v contents Series Editors’ Preface viiIntroduction 1 Storytelling in the Islamic...

Transcript of contents...v contents Series Editors’ Preface viiIntroduction 1 Storytelling in the Islamic...

&

v

contents

Series Editors’ Preface vii

Introduction 1

Storytelling in the Islamic Tradition 7

Puppet Theatre 10

The Persian Passion Play 17

European Theatre in the Islamic World 27

Islamic School Drama 32

Al-Hakim and the Modern Egyptian Theatre 44

The Later Twentieth Century in Egypt and Elsewhere 49

Challenges of the Twenty-First Century 63

Further reading and bibliography 72Endnotes 77Index 82

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

1

&theatre & islam

Introduction

Perhaps no title in the already extensive, varied, and grow-ing series of books in the “Theatre &” series is likely to engender as much surprise as “Theatre & Islam.” While the-atre’s involvement with a wide range of human institutions and practices is a phenomenon that will be readily accepted by most readers, there has long been an assumption, per-haps especially firmly held by theatre scholars themselves, that Islam as a faith was so fundamentally opposed to thea-tre that the two were essentially incompatible. For evidence of this, one need look no further than the most widely read and highly respected scholarly study of world theatre his-tory in the late twentieth century, at least in the English-speaking world: Oscar Brockett’s History of the Theatre, first published in 1968 and with new editions appearing every five years or so, maintaining its unrivaled position into the new century.

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

2

&theatre & islam

As the decades passed, the new editions of Brockett’s key work faithfully reflected an increasingly global attention to theatre. Beginning with an attention only to Europe, the United States, and a few classic oriental forms, the History gradually added more and more material on Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The Islamic world remained unconsid-ered, however, and indeed was specifically presented as a part of the world outside the boundaries of theatre. In the ninth edition, the first of this century (2003), when such previously neglected regions as Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa had begun to receive significant attention, the Islamic world remained unconsidered. Indeed, the book assured its readers that they need not be concerned by this, because theatre was not a form of any interest or importance in this vast area of the world. The 2003 edition confidently reaffirms a statement also found in earlier editions: “[Islam] forbade artists to make images of living things because Allah was said to be the only creator of life … the prohibition extended to the theatre, and consequently in those areas where Islam became dominant, advanced theatrical forms were stifled.”1

There are many problems with both the argument and the conclusions of this self-confident and wide-ranging pronouncement. Certainly there is a long tradition of ani-conism (absence of material representations of natural or supernatural figures) in Islam, but Brockett does not men-tion the fact (although it comes up elsewhere in his text) that this same suspicion of images is a major concern in all three of the world’s major monotheistic religions (Islam, Judaism,

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

3

and Christianity), not so much because only God could cre-ate but more because of a fear (expressed most familiarly in the second of the Ten Commandments) of competition from the “graven images” of other rival deities. Brockett sug-gests that there is almost universal agreement on “Islamic” opposition to theatre, but there is in fact a wide variety of opinions, as there is in Judaism and Christianity. “Advanced” theatrical forms are of course a code for modern Western forms, while the many highly developed performative tra-ditions of the world that do not conform to this Western model, such as dance-drama, puppet theatre, or enacted storytelling, are conveniently ignored. Many of these use images of living beings, which in fact have never been gen-erally prohibited in Islam. True, certain Islamic sects and clerics have condemned such representation, but so did Augustine and Tertullian, but we can hardly use that as a basis for saying that Christianity as a whole prohibited such activity, as Brockett, Hildy, and many others in the West have for Islam. Yet this bias continues, as John Bell noted in a 2005 survey of Western scholarship and the ignorance of Islamic performance in the West. Because Brockett and Hildy’s book “is so widely used and respected,” its “faulty scholarship remains dominant, the voice of authority.”2

Unhappily, this view of the incompatibility of Islam with theatre has by no means been restricted to Western scholars; many Arab writers, from classic times to the pre-sent, take a similar position. Their concern has often been traced back to the Arabs’ first encounter with Greek her-itage through Syriac translations, which took place during

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

4

&theatre & islam

the golden age of the Abbasid dynasty (the second century of Islam). Mohammed Al-Khozai, for example, argues that by “this time Arabic poetry was maturing; and because of the new monotheistic faith, it was unlikely that Arab schol-ars would turn to what they considered a pagan art form.”3 The Greek drama posed a particular problem because of its celebration of simulacra and conflict. This constituted a real danger to the newly established monotheistic Arabo-Islamic structure and to the social and political orders. Mohammed Aziza concludes that because of these serious cultural differ-ences, “It was impossible for drama to originate in a tradi-tional Arabo-Islamic environment.”4

This historical argument, even if correct, would apply largely to the early period of Islam (from the early seventh century), when the new faith was struggling to differentiate itself from its religious and cultural predecessors. However, the continuing opposition of many conservative Muslim clerics to representation in general and theatre in particular reflects a more basic concern, doubtless closely tied to the uneasiness in all monotheistic religions with the concept of representation. Both Arab and Western authors have, like Brockett and Hildy, long asserted that Islam as a faith does not allow taswir, the representation of either human or divine forms. This view has long circulated in the Arabo-Islamic intellectual and religious community, but in reality, there is no mention anywhere in Islam’s holy book, the Qur’an, speaking negatively about theatrical activity. Abdelkebir Khatibi and Mohammed Sijelmassi include an extensive study of this matter in their 1976 book The Splendor of Islamic

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

5

Calligraphy.5 In their critique of the reported Islamic injunc-tion against taswir, these authors state categorically that “the Qur’an does not expressly forbid the representation of the human form. In fact, no single verse refers to it at all.”6

The only authority for this injunction they could discover comes from the post-Qur’anic writings known as hadith. These are collections of sayings, reports, and commentaries on the Qur’an that were transmitted orally after the death of the prophet and later gathered and circulated by Islamic scholars. Although the authority granted to the hadith var-ies widely within the Islamic world, most Muslims consider them an important supplement to the Qur’an, though lack-ing its ultimate authority. One such hadith, collected by the Persian scholar al-Bukhari in the ninth century, seems to be a straightforward prohibition of figurative art: “when he makes an image, man sins unless he can breathe life into it.” Khatibi and Sijelmassi, after categorizing this hadith as “unverifiable,” go on to assert that even if it is authentic, the prohibition it articulates

was directed against the surviving forms of totemism which, anathematized by Islam, could conceivably reinfiltrate it in the guise of art. The principle of the hidden face of God could be breached by such an image. In one sense, theol-ogy was right to be watchful; it had to keep an eye on its irrepressible enemy – art.

In opposition to the widespread view that Islam is opposed to representation, they remind us of an alternative tradition

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

6

&theatre & islam

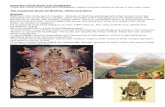

wherein the Prophet Mohammed “permitted one of his daughters to play with dolls, which are of course derived from the totemic gods. Moreover, there are numerous examples of figurative sculpture in Moslem art, and of drawings both of animals and humans.”7 On the whole, the Shia branch of Islam, centered in Persia, was more flexible on this matter, and the second Caliph8 al-Mansur, in the eighth century, even allowed representative sculpture in his palace in Baghdad.

When Islam was established as a new religion, in the early seventh century, not only the middle East, where it appeared, but all of Europe offered little of what most peo-ple today would call theatrical activity. The magnificent theatre culture of Greece and Rome now survived only in hundreds of crumbling monuments, used only for grazing animals or for looting stones to employ in more modest later structures. The only major theatre of that time was far to the east, where the spread of Buddhism, associated from the beginnings with masked dance performance, had by the seventh century established a major dramatic tradition in the Sanskrit theatre of India and significant dance theatre in Japan, China, and central Asia.

Islam, unlike Buddhism but like Christianity and Judaism, from the beginning emphasized not ritual but a sacred text and so did not, at least in its earliest manifesta-tions, generate theatrical material from within its own reli-gious observances. Nevertheless, as it developed in cultural significance and geographical extent, it inevitably interacted both positively and negatively with other elements of the

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

7

surrounding society. Although this society did not, as did the Sanskrit culture of contemporary India, have a signifi-cant theatre tradition, it nevertheless offered a variety of distinctly theatrical forms, all of which were inevitably influenced by the rise of Islam. Chief among these were the simple folk farces found in cultures around the world, pup-pet shows, and various forms of public address, particularly storytelling.

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

82

&&index

Abbasid dynasty, 4, 18Abiad, George, 31Adham, Ibrahim IbnAghasi, Hajji, 26Aglabite dynasty, 41Aisha, 8Al-Abid al Jalali, Mohammed ibn, 39Al-Bassan, Sulayman, 66–7Al-Bukhari, 5Al-Dakhil, Abdurraham, 43Al-Din, Salah, 29–31Al-Din Shah, Nasar, 26Al-Ghazi, Mohamed, 34Al-Haddad, Najib, 29–32Al-Hamid Ben Badis, Abd, 39Al-Hakim, Ali bin, Caliph, 9, 46,

48Al-Hakim, Tawfiq, 44–6Al-Haqrizi, 1Al-Haytham, Ibn, 11Al-Jawzi, Ibn, 8Al-Karim Qasim, Abd, 47

Al-Khozai, Mohammed Aziza, 4Al-Mansu, Caliph, 6Al-Musabbihi, 9Al-Naqqash, Marun, 28, 31Al-Qabbani, Ahmed Abu Khalil,

28–9Al-Qadidi, Ibrahim, 40Al-Qaradawi, Yusuf, 43Al-Qardhi, Jawq Sulayman, 30Al-Rashid, Harun, 48Al-Sabur, Salah Abd, 48Al-Sharqawi, Abd al-Rahman, 49Al-Sibaci, Shaikh Ahmad, 50Al-Wahhab, Abd, 33Ali Kahn, Hoseyn, 22Ali Shah, Fath, 26Alloula, Abdelkader, 65Armenian theatre, 28Augustine, 3

Baccar, Jalila, 67–70Bakathir, Ali Ahmed, 46

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

83

Bakr, Abu, 8Béjart, Maurice, 51Belaid, Chokri, 69Bell, John, 3Ben Ali, Zine al-Abidine, 68Berbers (Amazigh), 35, 37–8Bhabha, Homi, 60Bible, 24, 42Buddhism, 6Brockett, Oscar, 1–4Brook, Peter, 51, 53Bruyn, Cornelius de, 20–1

Cerulli, Enrico, 23Chaoui, Abdelouahed, 36China, 6, 11Chodzko, Alexandre, 22Christianity, 3, 6Crombecque, Alain, 53–5

Dabashi, Hamid, 55dance, 3Daniyal, Ibn, 11–14Djody, Setiawan, 58

Effendi, Roestam, 56El-Qurri, Mohammed, 36–7, 39

Fals, Iwan, 58Farag, Alfred, 50fatwa, 12, 52Francklin, William, 20Free Schools, 32–40, 42

Gauhar, Madeenha, 61Gogol, Nikolai, 50Grotowski, Jerzy, 51, 53

hadith, 5, 7Haq, Zia ul, 61, 63Halle, Adam de la, 12Hanifa, Abu, 48, 56Hijazi, Salama, 31hikayat, 10Hildy, Frank, 3–4Hinduism, 24Hitler, Adolph, 66Hussein Ibn Ali, 17–27, 49, 52Hussein, Sada, 53

Indonesia, 14Irarna, Rhoma, 58

Japan, 6Judaism, 2–3, 6

Kahtami, Mohammad, 54kathakali, 51Kerbala, Battle of, 18Khatibi, Abdelkebir, 4–5Khomeni, Ayatollah, 52, 54

Louix X, 47

Malekpour, Jamshid, 23–4Medjoubi, Azzedine, 65Mohammed, 6–9, 18, 43–4, 58,

64Moses, 25Muawiyah I, 18mu’in al buka, 21–2

Nadjib, Emha Ainun, 57Nadeem, Shahid, 61–3Nasser, Gamal Abdel, 47–8

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

84

&theatre & islam

Niebuhr, Carsten, 19Noer, Arifin C., 57Noh drama, 11, 51

Olearius, 19Osborne, Barrie, 44

Pelly, Sir Lewis, 22puppet theatre, 3, 9, 11–17

Qajar dynasty, 24, 27Qasim, 21qissa, quass, 8Qur’an, 4–5, 7, 12, 24, 36, 45–6,

59, 61

Rendra, Wahya Sulaiman, 58–9Reza Shah, 27Rumi, 23

Sabra, Shaikh Umar, 42salafiyya, 33–6, 38, 41, 64, 67,

69–70samajat, 10Sanskrit theatre, 6–7Sanu, Ya’cub, 28Sarumpet, Ratna, 58, 60Shah, Bulha, 61

Shah, Mohammed, 51Shah, Nasseredin, 24–5Shakespeare, William, 67Shia Islam, 6, 8, 13, 18, 70Sijelmassi, Mohammed, 4–5Stambuli, Khalifa, 41storytelling, 7–11, 18Sufi faith, 12–13, 23, 25, 48, 56–7,

59, 61–4, 70Suharto, 59–60Sunni Islam, 8–9, 13, 18, 64

tableaux vivants, 19takiyehs, 26–7Tasbrizi, Shamse, 23Talib, Ali Ibn Abi, 9ta’zieh, 9, 17–27, 49, 51–5, 70Teeuw, A., 56Tertullian, 3Torres, Abdelkhalak, 35–7, 39,

41

Umayyad dynasty, 8, 18, 43

Wilson, Robert, 51Winet, Evan, 57

Yazid I, 18–20, 23, 52

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608

Copyrighted material – 9781352005608