Conceptualizing Essential Components of Effective High Schools

Transcript of Conceptualizing Essential Components of Effective High Schools

Prepared for Achieving Success at Scale: Research on

Effective High Schools in Nashville, Tennessee

Conceptualizing Essential

Components of Effective High

Schools

Courtney Preston | Ellen Goldring | James E. Guthrie

Russell Ramsey

Conference Paper

June 2012

The National Center on Scaling Up Effective Schools (NCSU) is a

national research and development center that focuses on identifying the

combination of essential components and the programs, practices,

processes and policies that make some high schools in large urban

districts particularly effective with low income students, minority

students, and English language learners. The Center’s goal is to develop,

implement, and test new processes that other districts will be able to use

to scale up effective practices within the context of their own goals and

unique circumstances. Led by Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College,

our partners include The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

Florida State University, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Georgia

State University, and the Education Development Center.

This paper was presented at NCSU’s first national conference, Achieving

Success at Scale: Research on Effective High Schools. The conference

was held on June 10-12, 2012 in Nashville, TN. The authors are:

Courtney Preston

Ellen Goldring

James E. Guthrie

Russell Ramsey

Peabody College, Vanderbilt University

and

National Center on Scaling Up Effective Schools

This research was conducted with funding from the Institute of Education

Sciences (R305C10023). The opinions expressed in this article are those

of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the sponsor

or the National Center on Scaling Up Effective Schools.

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 3

Conceptualizing Essential Components of Effective High Schools

The National Center on Scaling Up Effective Schools is an Institute of Education Science-

sponsored consortium of five universities, two urban districts, and an intervention support provider.

The Center is focused on identifying the programs, practices, and processes that make some high

schools in large urban districts particularly effective with low-income students, minority students,

and English language learners and transferring these practices to less effective schools. We focus

on high schools because it is there that scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress

show only moderate gains over the past two decades, and international assessments indicate that

gaps between American students and their counterparts in other nations are widest (Grigg,

Donahue, & Dion, 2007; Provasnik, Gonzales, & Miller, 2009; U.S. Department of Education,

1998). More than a quarter-century has passed since A Nation at Risk raised concerns about the

“rising tide of mediocrity” in American education (U.S. National Commission on Excellence in

Education, 1983). Despite the ambitious reforms that followed, high schools today have low rates

of student retention and learning, particularly for students from traditionally low-performing

subgroups (Becker & Luthar, 2002; Cook & Evans, 2000; Davidson et al., 2004; Lee, 2002, 2004).

While racial and ethnic gaps in reading and mathematics achievement between both 17-year-old

white and black students and white and Hispanic students narrowed between l978 and the early

1990s, these gaps have remained stagnant over the last two decades (Murphy, 2010). Currently,

gaps between black and Hispanic 17-year olds and their white counterparts range from two to more

than three years of learning (Rampey, Dion, & Donahue, 2009). Gaps are even wider in the senior

year of high school between native English speakers and English language learners. Differential

dropout rates, wherein low-income students, minorities, and English language learners leave school

at higher rates than other students, only compound the problem (Kaufman & Chapman, 2004;

Snyder, Dillow, & Hoffman, 2009).

Reviews of research on high school students suggest that three decades of urban high school reform

aimed at improving disadvantaged student achievement has not resulted in substantially narrowing

the achievement gaps (Becker and Luthar, 2002; Cook & Evans, 2000; Davidson et. al., 2004).

There is little evidence that any single program or practice will close more than a fraction of the

achievement gap and reduce high school dropout (Berends, 2000; Miller, 1995). Through studies of

several organizational and structural elements of schools, the literature indicates that structures

alone do not increase school effectiveness; the evidence is weak or mixed for any structural or

organizational change alone leading to improved student outcomes. The research clusters around

two areas: how schools divide and use time in the school day (e.g., scheduling) and how students

and teachers are organized within that time to meet the academic needs of students (e.g., course-

taking practices, personnel assignment).

Studies examining the subdivision of time within the high school day do not clearly indicate best

practices, programs, or policies. Block scheduling of academic courses is found to be both more

(Hughes, 2004) and less effective (Rice, Croninger, and Roelke, 2002) than traditional course

scheduling. Dexter, Tai, and Sadler (2006) find that college science performance is no different for

students who had either block or traditional scheduling in high school.

Substantially improving the learning opportunities for students from traditionally low performing

subgroups will require comprehensive, multifaceted, integrated, and coherent designs (Chatterji,

2005; Shannon & Bylsma, 2002; Thompson & O’Quinn, 2001).

The purpose of this paper is to present eight essential components of effective high schools that

emerge from a comprehensive review of the effective schools and high school reform literature,

and provide a framework for how these components are implemented and integrated (Dolejs, 2006,

Murphy, Beck, Crawford, Hodges, & McGaughy, 2001; Murphy, Elliott, Goldring, & Porter,

2006). We submit that far-reaching school improvement in high schools is rooted in a set of

essential components that emerge from the literature on effective schools in general and effective

high schools in particular; schools succeed not because they adopt piecemeal practices that address

each of these components, but rather they organize their collective practices into a coherent and

cohesive framework of aligned practices. In effective schools, these components are woven into the

school’s organizational fabric to create internally consistent and mutually reinforcing reforms; their

success is explained by more than the simple sum of their parts.

The conceptualization of the Center's framework suggests that these essential components can

work together in effective high schools to create deep connections, engagement, and attachment for

both adults (leaders, teachers, staff) and students, to the work, the norms and the outcomes of high

schools, while the inability to effectively implement these components to high quality and high

frequency can explain alienation, disengagement and lack of effort in high schools for students and

adults. It is through the teaching of subject matter via a rigorous and aligned curriculum for all

students (the content of schooling) and through distributed, learning centered leadership (inspiring

the vision and enacting it) that the other core components can be implemented and sustained to

achieve positive outcomes for all students--through developing the a sense of attachment and

engagement.

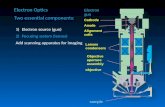

See Figure 1.

By alienation, we mean lacking a sense of belonging and engagement in a school setting (Schulz,

2011). This includes feelings of powerlessness or lack of agency, meaninglessness, normlessness,

social estrangement, and isolation (Taines, 2012; Smerdon, 2002; Mau, 1992). Feelings of

powerlessness are particularly salient in conceptualizing the continuum from alienation to

attachment for adults. Taines (2012) defines powerlessness as “a feeling of exclusion from the

decision making of societal institutions, discerning little political influence over the processes that

govern one’s affairs” (p. 57).

By attachment, we mean the degree to which individuals feel embedded in or a part of their school

community (Johnson, Crosnoe, & Elder, 2001). This includes a sense of belonging, commitment to

the work at hand, and a commitment to the institution itself, both its goals and purposes and the

structure and norms that govern how those goals are achieved (Smerdon, 2002).

In this paper we present a brief literature review of each of the components, and then end each

component by suggesting how these components can be operationalized to serve as the basis for the

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 5

design of interventions that can address the achievement gaps in high schools, and drive an

empirical research agenda. The literature review is based on a review of empirical research that

appeared in core education journals. We searched the table of contents and abstracts of twenty-two

journals, including American Educational Research Journal, Teachers College Record, High

School Journal, and Urban Education, for the words “high school(s)” from 1996 to present. We

then determined whether each article was relevant to our core components and sorted the articles

according to their relevant components for the authors to review1.

Essential Components of Effective High Schools

Specifically the Center's work is guided by eight essential components that provide a robust

framework to more deeply understand effective high schools. The components are organized into

two broad categories. First are those that constitute the necessary elements to develop engagement,

commitment and shared norms and values. These include: Quality Instruction, the teaching

strategies and assignments that teachers use to implement the curriculum and help students to reach

high academic standards. (McLaughlin & Talbert, 1993; Wenglinsky, 2002, 2004). Another

component is Systemic Use of Data, including using data to inform classroom decisions, and

multiple indicators of student learning, (Kerr, Marsh, Ikemoto, Darilek, & Barney, 2006). The

third component is Personalized Learning Connections, developing strong connections between

students and adults that allow teachers to provide more individual attention to their students and

dialogue with each regarding unique circumstances and learning needs (Lee, Bryk, & Smith, 1993;

McLaughlin, 1994; Lee & Smith, 1999) as well as developing students’ sense of belonging,

(Walker & Greene, 2009). The fourth essential component is a Culture of Learning and

Professional Behavior. This component refers to the extent to which teachers take responsibility

for events in the school and their students’ performance, and the degree to which they collaborate

their efforts through such activities as school wide professional development (Little, 1982; Lee &

Smith, 1995). The fifth essential component is Systemic Performance Accountability, both external

and internal structures that hold schools responsible for improved student learning. External

accountability refers to the expectations and benchmarks from state and national bodies, while

internal accountability consists of the district- and school-level goals (Adams & Kirst, 1999;

Murphy, Elliott, Goldring, & Porter, 2006). The final component is Connections to External

Communities, the ways in which effective secondary schools establish meaningful links to parents

and community organizations, and relationships with local social services, and student work

experiences in the community (Ascher, 1988; Shaver & Walls, 1998; Mediratta & Fruchter, 2001;

Sanders & Lewis, 2004).

The second set are what we call the anchors of the other components. These two components hold

together the other components and cut across them. These are Learning-centered Leadership,

1 The authors recognize this review does not encompass the full body of literature on effective high schools, but for the scope of this

paper, we limit our review to peer-reviewed journals and future versions will be more inclusive. As our next step, we will review high school reform programs and models (such as Big Picture Learning) to see the extent to which they implement and engage around the

core components.

which entails the extent to which leaders hold a vision in the school for learning and high

expectations for all students (Murphy, Goldring, Cravens, & Elliott, 2007) and focus all leadership,

distributed on the other components, and Rigorous and Aligned Curriculum, which focuses on the

content that secondary schools provide in core academic subjects; it includes both the topics that

students cover as well as the cognitive skills they must demonstrate during each course (Gamoran,

Porter, Smithson, & White, 1997).

First, Quality Instruction encompasses the teaching strategies teachers employ to achieve high

standards for all students. Much of the research discussing the quality of instruction at the high

school level is descriptive, either explaining programs that have been developed and implemented

to increase student achievement, particularly in math, or case studies describing the practice of

effective teachers. Trends in this research cluster around common practices and specific classroom

foci. Common practices include collaborative group work and inquiry-based learning (Staples,

2007), formative assessment (Brown, 2008), scaffolding, and introducing new concepts concretely

(Alper, Fendel, Fraser & Resek, 1997). Foci include creating structures and classroom climate

where students are allowed to try and fail without negative consequences (Alper, et al., 1997),

making content not only relevant for real life, but important, and setting high expectations for all

students (Boaler, 2008).

The vast majority of more recent work on the quality of instruction has focused on developing

frameworks and corresponding classroom observation rubrics. These observation rubrics are either

subject-specific such as Mathematical Quality of Instruction (MQI) (Hill, Blunk, Charalambous,

Lewis, Phelps, Sleep, & Ball, 2008) and the Protocol for Language Arts Teaching Observations

(PLATO) (Grossman, Loeb, Cohen, Hammerness, Wyckoff, Boyd, & Lankford, 2010) or are

designed for use across subjects like the Classroom Assessment Scoring System-Secondary

(CLASS-S) (Pianta, Hamre, & Mintz, 2011) and Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching

(2007). Behind each of these rubrics is the articulation of a conceptualization of the quality of

instructional practices.

The framework guiding the Center's work on conceptualizing the quality of instruction in high

schools is the CLASS-S. The CLASS-S articulates domains and dimensions of quality instruction,

where dimensions describe various aspects of each domain (Pianta, Hamre, & Mintz, 2011). The

three core domains of the CLASS-S are instructional support, emotional support, and classroom

organization, with a fourth domain, student engagement as an outcome. Instructional support

includes teachers’ demonstration of their content understanding, how teachers facilitate student use

of higher order thinking skills, the quality of feedback teachers provide, and their use of

instructional dialogue to facilitate content understanding. Emotional support largely overlaps with

the academic engagement aspect of personalized learning connections and includes measures of

positive and negative classroom climate, teacher sensitivity and responsiveness to student needs,

and teacher’s regard for adolescent perspectives, i.e., the degree to which teachers provide

opportunities for autonomy and leadership as well as relevant applications of content. Finally,

classroom organization includes behavior management, productivity or the maximization of

learning time, and teachers’ use of a variety of instructional learning formats to maximize student

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 7

engagement.

This framework, as well as others, suggests that high quality instruction is rooted in a notion of

engaged learning (instructional dialogue, feedback, responsiveness), whereas low quality

instruction consistently allows students to be passive, and disengaged as learners (seatwork,

receivers of information, and limited accountability for learning).

Other research supports the notion that quality instruction is about engaging the student through

teaching. In English/Language Arts, empirical studies find that content is a significant predictor of

reading achievement (Carbonaro & Gamoran, 2002). Increased student voice, where students play

a more equal role with teachers in classroom discourse, and hours spent on homework also have

positive associations with reading achievement (Applebee, Langer, Nystrand, & Gamoran, 2003).

Additionally, Nystrand (1997) finds that a number of features of classroom discussion are related to

spring achievement scores: authentic questions that promote exploration instead of only

comprehension, more time for open discussion, and teacher questioning that build on student

responses.

A case study of a high school math department implementing a reform curriculum and teaching

methods found that instruction focused on collaborative group work where there were multiple

avenues for success, each student had a structured role, and students were required to justify their

answers and responsible for each others’ learning (Boaler & Staples, 2008). Teachers setting high

expectations and providing tasks with high cognitive demands were key elements in this reform as

well. A similar case study of a high school English department describes details how teachers

promote higher-level reasoning and students’ responses to their efforts (Anagnostopoulos, 2003).

Teachers collaboratively learned to write and wrote questions higher-order questions based on

Marzano’s and Bloom’s frameworks for higher order thinking skills. While students initially

needed teacher support to answer these questions about their reading, ultimately, they reported

becoming aware of the relationship between their effort and academic outcomes, as well as

developing the ability to identify distractions, learn new vocabulary, and better manage their time.

Other case studies of teachers’ roles in collaborative learning, including group work and

discussions, focus on the importance of scaffolding. Scaffolding is important both in teaching

students discussion skills (Flynn, 2009) and in focusing students on the task at hand and making

them think through their actions, through prompts and probing and meta-cognitive questions

(Anderman, Andrzejewski, & Allen, 2011; Gillies, 2008). In a review of the research on the

relationship between classroom activity structure and the engagement of low-achieving students,

Kelly and Turner (2009) propose a set of guidelines for whole class discussion to reduce the risk of

participation: teachers must relinquish authority over the direction and topic of discussion and defer

evaluation of students’ comments in order to demonstrate that student ideas are important. They

provide examples of scaffolding to promote student motivation, engagement and effort: modeling

thinking, giving hints, asking for explanations, providing feedback instead of evaluation, treating

mistakes as opportunities, and emphasizing joint responsibility between students and teachers. The

absence of these teaching strategies can lead to classrooms where students are disengaged from

their teachers, other students, and the academic content learning; in a word, students are bored.

They describe a boring classroom as “one-way, tops-down, unengaged relationship with a teacher

whose pedagogy feels disrespectful because it is not designed to tempt, engage, or include

students” (Fallis & Opotow, 2003, p. 108).

A second component, Systemic Use of Data refers to “data use” or “data-based decision making” as

a practice critical to school improvement efforts. Yet it would be faulty to assume that access to

data alone will lead to more effective practice (Ingram, Seashore Louis, & Schroeder, 2004;

Schildkamp & Visscher, 2010; Spillane, 2012). Rather, research on systematic data use suggests

that effective practice requires a critical consideration of both which data and which forms of use

are most effective in improving academic performance. The empirical literature provides insights

on the sources, practices, and actors characterizing effective data use in high schools based on

largely correlational research. Although research specific to data use in high schools is scant, a

consistent finding across this work is that where data use is effective, the power to make data-based

decisions is diffuse, collaborative, and pervasively integrated into practice. In contrast, data-based

decisions made centrally and dictated to teachers breed resistance, foster mistrust, and do not

improve instructional practices. We thus suggest that data use is one mechanism to develop

engagement and commitment of educators to students, and to school goals through sharing and

distributing information and decision, and it can be a mechanism for helping adults and students

collaborate and receive feedback for continuing engagement in the 'work' of schooling.

The first characteristic of effective use of data in high schools is a diffusion of both the availability

and analysis of data. Studies of educational leadership, for example have found data use to be the

arena of school activity which best exemplifies the effectiveness of distributed leadership

(Copland, 2003; Schildkamp & Visscher, 2010; Spillane, 2012). Diffusion may be most critical in

high schools, which are commonly departmentalized around subject areas. When data access is

centralized in the hands of a principal, data use can be limited by the principal’s personal beliefs

and skills related to data use (Luo, 2008).

Though diffusion is necessary for effective data use, it is not sufficient. In Wilcox and Angelis’s

(2011) review of high school best practices, they found that the distribution of power to teachers to

make data-based decisions, enacted as a “solitary activity,” characterized low- and average-

performing schools. In high-performing schools, by contrast, teachers’ data use drives

improvement from the center of a school-wide feedback loop (Schildkamp & Visscher, 2010;

Wilcox & Angelis, 2011).

In addition to the relationships found between school-level achievement and collaboration, research

also suggests that collaborative data-based inquiry affects intermediate outcomes, increasing

teachers’ investment in school-wide issues, strengthening instructional efficacy (Huffman &

Kalnin, 2003), and characterizing both mature and successful school improvement efforts

(Copland, 2003; Tedford, 2008; Wilcox & Angelis, 2011). Ingram, Seashore Louis, and Schroeder

(2004) identified multiple barriers to data use in high schools, several of which stem from

disagreement over which outcomes matter most. Evidence suggests that teachers are more open to

collaborative data use when the definition of “data” includes surveys and interviews in addition to

student test scores (Wilcox & Angelis, 2011) and when teachers have ownership of both the

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 9

collection and analysis of data (Huffman & Kalnin, 2003).

Finally, once data are available and discussed collaboratively, it must permeate organizational

routines in order to be effective (Ingram, Seashore Louis, & Schroeder, 2004; Schildkamp &

Visscher, 2010; Spillane, 2012). That is, even when data are diffuse within the school and teachers

are organized to support collaboration, it is still not guaranteed that practices will improve. For

instance, without redirection and retraining, teachers may fall into patterns of ineffective data use,

such as devising strategies before considering evidence (Copland, 2003). The pervasiveness of

data-based decision making can even extend beyond instructional practice, as Copland found that

in schools with established routines of data-based inquiry, principals may look for teaching

candidates they believe will contribute positively to collaborative discussions tying practice to

performance feedback.

In our framework, we operationalize the effective use of data in high schools as schools where data

are available for all stakeholders to access, including parents, teachers, and students, teachers have

the capacity to use this data and act on what they learn from it (i.e., re-teaching), and there is a

culture of data use among members of the school community. We view data use as an important

component for creating shared commitment and engagement amongst adults and students.

A third component, Personalized Learning Connections involves developing strong connections

between students and adults that allow teachers to provide more individual attention to their

students (McLaughlin, 1994; Lee & Smith, 1999); personalized learning connections also refers to

developing students’ sense of belonging to school (Walker & Greene, 2009). Personalized learning

connections can exist in any high school on a continuum from strong and robust leading to

connectedness, to weak and non-existent, leading to alienation (Nasir, Jones, & McLaughlin, 2011,

Hallinan, 2008, Crosnoe, Johnson, & Elder, 2004).

The importance of understanding the extent to which there are personalized learning connections in

a high school is related to understanding the mechanisms and explanations for students dropping

out of high schools: student alienation and disengagement is a long-term process, but ultimately,

the consequence of alienation is dropout (Rumberger, 2001). Much of the research around high

school dropout seeks to understand the role of schools in predicting dropout (e.g. Patterson, Hale,

& Stessman, 2007; Lee & Burkham, 2003, Englund, Egeland, & Collins, 2008). Using data from

the High School Effectiveness Study, a part of NELS:88, Lee and Burkham (2003) find that

students in schools with stronger student-teacher relationships have decreased odds of dropping

out. However, the strength of the relationship between student-teacher relationships and dropout

differs across school size: as school size increases, the strength of the relationship decreases. Using

NELS:88 data, Rumberger and Larson (1998) address individual determinants of dropout and find

that measures of academic and social engagement (i.e., absenteeism, behavior, extra-curricular

participation) are predictors not only of dropout, but also of student mobility, suggesting that

student mobility is another form of disengagement.

Similarly, at risk students who participate in extra-curricular activities, specifically sports and

volunteering, are twice as likely to graduate from high school and enroll in college (Roeser & Peck,

2003; Peck, Roeser, Zarrett, & Eccles, 2008). Extra-curricular activities play a role in developing

personalized learning connections in high schools. In a review of the literature on school-based

extracurricular activities and their role in adolescent development, Feldman and Matjasko (2005)

find that the costs and benefits of participating in extracurricular activities vary across types of

activities and social contexts. Such activities do provide opportunities to develop social capital and

supportive networks, such as mentoring relationships with coaches and other adults. These supports

and networks, in turn, increase student connectedness, which has a positive relationship with

achievement and staying in school (Eccles, Barber, Stone, & Hunt, 2003; Mahoney, 2000).

Working during high school, on the other hand, has been found to have negative effects on

academic outcomes such as grades and progression towards graduation (Marsh & Kleitman, 2005).

Class cutting is another result of this alienation, what students describe as “boredom:”

disappointment in their education and feelings that they are not being challenged or engaged in

productive work (Fallis, 2003). Teachers can compound this class-cutting in their reactions to it,

indicating they do not care about students and whether they attend class.

Inside the classroom, teachers are the primary agents of developing personalized learning

connections. The vast majority of research describing teachers’ role in promoting personalization

of learning takes the form of qualitative case studies. Salient in this literature is the idea that the

burden for developing relationships with students falls on the teacher (Cothran, 2003; Anderman,

Andrezejewski, & Allen, 2011). To develop personalized learning connections, teachers must show

interest in their students, be enthusiastic, and care about them (Whitney, Leonard, Leonard,

Camelio & Camelio, 2005). Their interactions with students must occur both formally and

informally (Stronge, 2002). Teachers’ approach to discipline is a key factor in the development of

these relationships, from students’ perspectives. Students want to trust their teachers to be fair and

this trust is a key component in student respect of teachers (Gregory & Ripski, 2008; Cothran,

2003). This relational support that teachers provide students is positively associated with their

academic motivation (Legault, 2006).

Additionally, a number of structural factors can promote teachers forming such relationships with

their students: small school size (Lee, Smerdon, Alfed-Liro, & Brown, 2000), small class sizes,

weekly structured advisory periods (Darling-Hammond, Ancess, & Ort, 2002) with a clear purpose

and sufficient resources (personal and social services) for teachers (Nasir, Jones, & McLaughlin,

2011), and cross-discipline teaming of teachers wherein teachers share the same group of students

(Langer, 2000)

In the Center's work we operationalize schools with positive personalized learning connections as

schools with personalization for both academic and social learning, where students feel strong

connections to the school, both through classroom engagement and opportunities for involvement

in extra-curricular activities, and where these connections exist on a school-wide level with specific

social and academic structures in place to support the development of these connections. Examples

of such structures might include looping and discipline structures that require student discussions

with administration and support personnel.

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 11

Culture of Learning and Professional Behavior, the fourth component, refers to students and

teachers in effective high schools who take part in a strong culture of learning and professional

behavior. In terms of students, this culture is defined by a shared focus on high expectations for

students and emphasis on students’ academic needs among the administration, staff and faculty of

the school. Students internalize these cultural values as well, taking responsibility for their own

learning and working together to promote their academic success. For teachers, much of this

component also includes the notion of teacher professional learning communities and other

communities of practice the define norms of engagement, commitment and heightened

professionalism for learning.

There are four major aspects that determine and set the tone of a culture of learning and

professional behavior: 1. safety, including physical and social-emotional aspects; 2. teaching and

learning, including instructional quality and social, emotional and ethical learning, professional

development, and leadership; 3. relationships, including respect for diversity, school community

and collaboration, and morale and connectedness; and 4. environmental-structural aspects,

including aesthetics, resources, and extra-curricular activities (Cohen, McCabe, Michelli, &

Pickeral, 2009; Cohen, 2006; Freiberg, 1999).

The literature in this component clusters around teacher communities of practice, teacher

expectations of students, and student-teacher relationships. A culture of learning and professional

behavior is often supported by a teacher learning community as a means of professional

development. Research addressing teacher learning communities are largely case studies. These

may be Critical Friends Groups, teacher inquiry groups, professional learning communities, or

communities of teacher practice. While these groups take various forms, most have instructional

improvement as a goal and center around teacher collaboration (Emerling, 2010; Curry, 2008).

Different types of groups engage in different activities: Critical Friends Groups may engage in a

range of activities (Curry, 2008), teacher inquiry groups may focus on planning and implementing

specific strategies to address particular instructional problems (Emerling, 2010), and teacher

communities of practice may engage in data analysis and addressing student academic and social

needs (Levine and Marcus, 2010). Such communities work to build a culture of learning and

professional behavior by deprivatizing teacher practice and focusing on aspects of their work

teachers can control and change, working to change teacher practice which should lead to increased

student learning (Levine and Marcus, 2010; Vescio, Ross, and Adams, 2008). This sense of

collective efficacy has been found to predict student achievement across multiple subjects

(Goddard, LoGerfo, & Hoy, 2004).

Effective schools create a culture of learning and professional behavior among students through

school-level and teacher-level high expectations of students. These schools clearly state their

expectations for student behavior and academic performance (Wilcox and Angelis, 2011), and

teachers have an active commitment to the collective expectation of students, playing a crucial role

in student’s internalization of a culture of achievement (Gutierrez, 2000; Rhodes, Stevens, and

Hemmings, 2011; Pierce, 2005). Hoy, Tarter, and Hoy (2006) contend that a school’s culture is

built around three components: academic emphasis and high expectations, collective efficacy of

students and teachers, and faculty trust in parents and students. Effective schools create this culture

by pressing for and celebrating academic achievements, modeling success for teachers and

students, and creating useful communication pathways for students and families (Hoy et al, 2006)

When faculty and staff do not hold high expectations for all students, the result is alienation

(Patterson, Hale, Stressman, 2008); student disengagement due to low expectations is the primary

reason for class cutting (Fallis & Opotow, 2003) and eventual dropout (Patterson et al, 2008).

An effective culture of learning and professional behavior should lead to increased student effort

and ownership. Domina, Conley, and Farkas (2011) examine several secondary data sets and find

that students with higher expectations placed upon them exert higher effort in their classes;

Carbonaro (2005) also finds that students in higher tracks exert more effort, controlling for prior

achievement and prior effort.

In the Center, we operationalize this component as schools where both adults and students have a

culture of learning and high expectations among themselves: there are frequent opportunities for

teachers to collaborate around instructional issues and participate in professional development,

faculty have collegial relationships and a sense of collective efficacy, and students are supported

academically based on their performance. These opportunities may be supported by specific

practices such as professional learning communities, looping, and instructional coaching teams.

Systemic Performance Accountability refers to “new accountability” of education reform, where

outcomes take precedence over processes in the evaluation of scholastic performance (Elmore,

Abelmann, & Furhrman, 1996). The emphasis on outcomes is evident throughout the system:

schools and districts face sanctions specified under the federal No Child Left Behind Act; student

test scores increasingly determine grade promotion and graduation; and in a some locations student

test scores now constitute a portion of teacher performance evaluations. In theory the argument is

that as teachers and other educators are accountable for student outcomes, and there are real

consequences for student outcomes, standards of achievement will increase. Yet the literature on

systemic performance accountability in secondary schools finds that efforts to shift the focus of

educational accountability from educator processes to student learning outcomes do not always

achieve their desired effects on either processes or outcomes. However, the success or failure of an

accountability policy does not appear to be a function of the quality of the policy’s design but of

how those at the “street level” ultimately implement it (Anagnostopoulos, 2003; Anagnostopoulos

& Rutledge, 2007; Carlson & Planty, 2011; Hemmings, 2003).

One finding consistent across the literature is that the success of accountability policies, as

measured by either implementation fidelity or student achievement, is mediated by teachers’ beliefs

about their students (Metz, 1990). Specifically, whether teachers alter their practices in response to

new policies hinges on educators’ willingness to acknowledge connections between instructional

practices and student learning (personal responsibility), and between student learning and the

policy’s outcomes of consequence (data validity). Acknowledging these linkages determines

whether educators respond to accountability measures with instructional strategies or deflection

strategies.

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 13

High school teachers do not adapt instruction in response to outcome-focused accountability

policies in cases where they do not believe their practices meaningfully contribute to the outcomes

of consequence. Instead, teachers deflect policies’ intended responses either with “cognitive

shields” (Anagnostopoulos, 2003) or tactical deflection strategies. As accountability policies

increasingly center on student learning, teachers in high schools see the onus for meeting increased

performance standards falling on students (DeBray, 2005). Other evidence suggests that teachers’

dissociation of their instructional practice and student achievement is a long-standing facet of

teachers’ professional culture (Ingram, Seashore Louis, & Schroeder, 2004). Thus when students

struggle to achieve performance targets set forth by accountability policy, teachers distribute blame

between students’ inadequate preparation and lack of motivation or interest (Anagnostopoulos,

2003; Anagnostopoulos & Rutledge, 2007; DeBray, 2005). As an alternative to cognitive

deflection, teachers may also employ tactical deflection strategies. These deflection strategies

include lowering expectations, accommodating problematic student behaviors, and altering results

(Anagnostopoulos, 2003). For instance, Carlson & Planty (2011) find evidence that where

accountability policies have ostensibly ratcheted up student graduation requirements, educators

manipulate the policy to allow students to graduate without meeting the new requirements. Such

practices may be partially responsible for disappointing effects of graduation requirements on

student achievement and college-going rates (Holme et al, 2010; Reardon et al, 2010).

The effectiveness of accountability policies also relies on outcomes of consequence that educators

understand and accept as valid measures of academic success. This concept appears throughout

literature on accountability, though under different phraseology: “coherent and good targets”

(Porter et al, 2004), “validity of outcomes chosen” (Schildkamp et al, 2010), a “coherent vision for

success” (Wilcox & Angelis, 2011). Given the difficulties and challenges noted in the literature, the

Center operationalizes Systemic Performance Accountability as the degree to which adults receive

regular oversight in their duties and responsibilities and are provided with frequent feedback for

improvement, and there is a system of rewards and consequences in place related to this system of

accountability.

Connections to External Communities refers to robust connections and relationships between

schools, families and other community agencies. The literature on high schools and parent and

community relationships is limited, especially when compared to the vast conceptual and empirical

literatures on parental and community engagement in elementary schools and in education in

general. The larger literature's focus on elementary schools does not take into account the unique

features of high schools, or the unique developmental needs of adolescents. While there is

agreement with the notion that "families, communities and schools hold shared and overlapping

responsibility for the healthy development and the social and academic success of all children

(Davies, 1995, p. 267)" less is understood as to how these aspirations are fulfilled in high school.

To the extent that the literature on the relationships between high schools and student achievement

does address external constituencies, the focus is primarily on parents, with much less attention to

the larger community in terms of social agencies, businesses and community assets. There is,

however, a growing literature on business partnerships as high schools design and implement

career ready standards and 'academies', schools-within a school that focus on themes or specific

areas of study to connect to the workplace.

The empirical research in high schools is clear: parental support and parent involvement matter, as

these provide sources of social capital. The existing literature suggests the much like other

components of effective high schools, connections to external communities tend to enhance the

high school student experience through developing attachments and social networks, while lack of

connections seems to contribute to alienation and disengagement. Interestingly, much of the

empirical research on high schools specifically is based on NELS 88 data, or other longitudinal

data from late 1980s.

The parental involvement literature primarily relates to what actions, or activities of parents are

important for high school student achievement and graduation, and how schools can help develop

parent involvement. In terms of what aspects of parental involvement are important for positive

student outcomes in high schools, Crosnoe (2001) explains that from an adolescent development

perspective parent involvement in high school involves four aspects: "parents' management of their

adolescents'' careers (e.g. helping to select courses), active assistance (e.g. helping with

homework), encouragement of educational goals, and attendance at school events (Muller, 1995)"

(Crosnoe, 2001, p. 212). Strayhorn (2010) reported similar findings in studying black high school

student achievement in mathematics. As part of a longitudinal study of 6 high schools in two states

in the late 80s, Crosnoe found that in general, parent involvement in the above areas decreases over

time in high school. The largest decrease is of parents of the college-preparatory tracks, while

general and remedial track parents' involvement is more stable over time. In a more recent study,

Crosnoe and Schneider (2010) found that students with lower test scores from 8th grade were more

likely to enroll in higher-level math classes in 9th grade when they discussed course selection with

their parents. Englund and colleagues (2008) concluded that parent-adolescent relationship are very

important in understanding high school dropping out and that teachers can help support students if

they do not have positive relationships at home.

As noted, most researchers explain the importance of these results in terms of social and cultural

capital in an adolescent developmental framework, and the importance of positive parent -child

relationships in helping adolescents navigate the high school experience. It should be noted that

this approach has also been criticized in terms of the 'highly defined, social constructed scripts' for

parent involvement (Smrekar & Cohen-Vogel, 2001, p. 75), one that is often rooted in one way

communication, rather than a partnership of overall support and development, taking into account

the cultural contexts and needs of families.

Research on how to involve parents is less prevalent as it pertains to high schools. Much has been

written about the importance of understanding cultural perspectives and barriers from parents'

points of view, creating a caring, welcoming climate. Bauch and Goldring (2000) found in a study

of high schools of choice that a supportive school environment, a caring atmosphere, and requiring

parent volunteering influences the opportunities teachers' perceive that the school provides for

parent involvement at school, the extent to which the school seeks parents' advice, provides

information to parents, and initiates contacts with parents. In particular, the organizational quality

perceived by teachers that most characterizes a communal school organization, a caring

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 15

atmosphere, appears to have the greatest impact on opportunities for parent involvement. In

addition, a supportive school environment has the greatest influence on the school's provision of

information to parents.

It is taking into account these perspectives of two-way partnerships, moving beyond parents to

broader community agencies, and fostering stronger parent-student relationships that the center

operationalizes this component as schools where there are diversified strategies for involving

parents from all sub-groups, support for student initiatives to create linkages between the school

and external communities, and connections with the community that strengthen the school such as

vocational training opportunities.

The Anchors of the Components

As noted above, we submit that Learning-Centered Leadership and A Rigorous and Aligned

Curriculum anchor the other six essential components. These two components hold together the

other components and cut across them. While none of the components in and of itself is sufficient

for an effective high school, learning-centered leadership and rigorous and aligned curriculum are

the aspect upon which the other components can be built and, in an effective school, holds strong

influence over how the other components are enacted.

Learning-Centered Leadership2

An important aspect of understanding how schools cultivate, support, and improve the essential

components of effective schools is school leadership. Prior studies suggest that schools whose

leaders organize their schools by articulating an explicit school vision, generating high expectations

and goals for all students, and monitoring their schools’ performance through regular use of data

and frequent classroom observations are linked to increases in their students’ learning (Leithwood

& Riehl, 2005; Murphy, Goldring, Cravens, & Elliott, 2007). Principals’ effects on student

learning are also likely mediated by their efforts to improve teacher motivation and working

conditions (Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom, & Anderson, 2010) as well as to hire high quality

personnel (Grissom & Loeb, 2011; Horng, Klasik, & Loeb, 2010). Finally, research suggests that

principals can play important roles in implementing instructional reforms. Quinn (2002) found that

in schools where principals actively work to secure curricular materials and act as instructional

resources for instructional reforms their teachers more frequently engaged in the new instructional

strategies.

When not specific to high schools, studies of effective leadership have found positive effects for

instructional (Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008) or transformational leadership approaches

(Leithwood, Leonard, & Sharratt, 1998). Yet in comparison to elementary schools, high schools

face unique, less tractable challenges (Fernandez, 2011; Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, 2008). These

challenges may also demand different strategies. Research on high school leadership is limited.

One study of high school principals’ time use found that time spent on organization management

2 This section was written with Jason Huff as co-author.

issues is associated with positive school outcomes including student learning, staff satisfaction, and

parental assessments of the school, and that time devoted to instructional oversight characterized

principals had no positive effects (Horng, Klasik, & Loeb, 2010).

However, the body of empirical research on leadership practices in schools is limited in a number

of ways conceptually and in terms of its applicability to high schools. In particular there are very

few empirical studies devoted to high school leadership broadly defined. Conceptually, much of the

research on leadership in schools takes a predetermined dimension of leadership—such as

instructional leadership—and offers assessments or comparisons of leaders’ (most often

principals’) adherence to specific, discrete practices to the authors’ conceptualization of these

dimensions (see, for example, Goldring, Huff, May, and Camburn, 2008; Horng, Klasik, & Loeb,

2010; Supovitz, Sirinides, & May, 2010).

High schools are unique educational setting because of the greater autonomy and inertia of older

students, departmentalization around academic subject area, and the responsibility associated with

being the terminus of universal education. High schools also differ significantly from elementary

and middle schools because of their larger size, unique and heterogeneous student body, and their

role in providing students with an exodus into the larger society and workforce (Fuhrman and

Elmore, 2004; Jacobs and Kritsonis, 2006). These distinguishing features may exacerbate cultural

barriers to centralized decision-making and increase the importance of distributed leadership within

departments or other forms of professional learning communities.

A fruitful approach to articulating learning centered leadership in high schools is to follow

Spillane's (2012) notion of “practice,” rather than articulate a set of lists of behaviors as we

attempt to understand how leadership influences the enactment of the essential components

described above. Following Spillane’s (2012) work we use “practice” to refer to "more or less

coordinated, patterned, and meaningful interactions of people at work; the meaning of and the

medium for these interactions is derived from an ‘activity’ or ‘social’ system that spans time and

space. A particular instance of practice is understandable only in reference to the activity system

that provides the rules and resources that enable and constrain interactions among participants in

the moment" (p. 114). A key aspect of practice as developed by Spillane (2012) and Feldman and

Pentland (2003) is the notion of an “organizational routine,” which they define as “a repetitive,

recognizable pattern of interdependent actions, carried out by multiple actors” (Feldman and

Pentland 2003, p.105). These authors also offer one final distinction that is central to our

conceptualization of Learning Centered Leadership: the “ostentive” versus “performative” aspects

of organizational routines. Feldman & Pentland define these as the following: “The ostensive

aspect is the ideal or schematic form of a routine. It is the abstract, generalized idea of the routine,

or the routine in principle. The performative aspect of the routine consists of specific actions, by

specific people, in specific places and times. It is the routine in practice” (p. 101, 2003). They

argue that studies of organizational routines must include examinations of the “ostentive,”

intended, ideal forms of practices (such as recommendations or formal expectations for what a

group should do to examine school data) along with the “performative” aspect that focuses on what

different individuals actually do within the context of these expectations and their group. Only

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 17

when researchers pay attention to both can they capture organizational routines in their intent and

in their actual implementation.

This focus on practices and routines is consistent with a distributed perspective of leadership

(Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001) as it transcends one person or specific roles (our

definition of leaders in these schools includes administrators, department chairs, and leaders of

other groups such as professional learning communities), and it also acknowledges the extent to

which leadership is dependent upon interactions between multiple actors in schools.

Existing research reveals a complex relationship between the leadership of school principals and

student achievement—principals' influences on student learning outcomes are often indirect,

mediated through multiple factors within the school. Researchers have produced extensive

evidence that principals’ practices can influence student learning when they focus on a) organizing

school structures, processes and resources that support student learning and b) strategies that more

closely support teachers’ high quality instruction (Hallinger & Heck, 1996a; Heck & Hallinger,

2009; Supovitz, Sirinides, & May, 2010; Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom, & Anderson, 2010; Horng,

Klasik, & Loeb, 2010). It is these structures and strategies that are the focus of our

conceptualization: strong leadership sets and implements vision for all stakeholders, supports the

development of quality instruction, supports the development of a rigorous and aligned curriculum,

promotes personalized learning connections for students, promotes ongoing analysis and review of

school level data, garners and allocates resources to support student learning, and promotes the

development of teachers’ instructional expertise.

Rigorous and Aligned Curriculum

Rigorous and Aligned Curriculum focuses on the content that schools provide in core academic

subjects (Gamoran, Porter, Smithson, & White, 1997) and is a second anchor that cuts across the

other components. On the whole, high school curricula are driven by state standards, as required

under No Child Left Behind (2002). Research on curriculum at the high school level centers around

differences between vocational/technical curriculum or remedial courses and college preparatory

curriculum, case studies of implementing new packaged curricula, the effects of increasing

curricular requirements for graduation, and access to curriculum, specifically advanced courses, for

different groups of students.

A number of studies address the effects of constrained curriculum, effectively requiring the same

college preparatory curriculum for all students. Lee and Burkham (2003) find that students in

schools with more constrained curriculum have lower odds of dropping out. Constrained

curriculum includes requiring specific college preparatory courses for students, including Algebra I

in the ninth grade (Allensworth, Nomi, Montgomery, & Lee, 2009) or replacing remedial math

courses with transition courses (Gamoran et al, 1997). These studies find that, while achievement

growth for students in transitional courses falls between that of students in transitional classes that

of students in Regents classes, it is not significantly different from either. Further, Allensworth et al

(2009), find increased failure rates and lower GPAs for the lowest ability students. The failure of

requiring Algebra I to improve academic outcomes, while increasing the number of students

receiving Algebra I credit begs the question of whether schools changed the content of courses

being offered or merely renamed remedial courses. Gamoran et al’s finding (1997) that math

achievement is greater in classes where more content is covered supports this hypothesis.

Case studies consider the implementation of constrained curriculum as well. A new technical high

school in Florida requires the same course sequence for all of its students in their first two years,

where every course either fulfills a graduation or college entry requirement or prepares students to

choose a technical course of study (Blasik, Williams, Johnson & Boegli, 2003). Descriptive

comparisons of student achievement in reading and math scores show students outscoring both

county and state averages.

Others studies explore the factors explaining both contexts in which advanced courses are offered

and patterns of student enrollment in these courses. A mixed methods study of eight high schools’

efforts to increase the number of African-American students enrolled in advanced math courses

demonstrates the overlap among the essential components of effective high schools. Teachers’

commitment to students, including accessibility outside of class hours and structured tutoring

opportunities (PLC), commitment to collaboration (CLPB), and use of specific instructional

strategies including cooperative learning and using materials relevant to students’ live (QI)

contribute to this increased enrollment (Gutierrez, 2000). Another study in Florida finds the

number of students taking Advanced Placement courses is, over time, increasingly driven by the

students’ prior preparation, but controlling for school size, teacher resources do not play a role in

the number of advanced courses offered (Iatarola, Conger, & Long, 2011). Further, schools with

higher percentages of minority students and students eligible for free or reduced price lunch are

less likely to offer advanced courses. In Texas, twenty percent of white students are enrolled in

Advanced Placement courses, while only ten percent of black, Hispanic, and economically

disadvantaged students are (Moore & Slate, 2008).

Few studies address curricular alignment between high schools and institutions of higher education

(IHEs). A fixed effects analysis of partnerships between school districts and IHEs in California

finds increased graduation rates and increased numbers of students who graduate having completed

necessary requirements for admission to either the California State University system or University

of California system. (Domina and Ruzek, 2010). These partnerships provide student services and

teacher professional development and may even be involved in district planning and policy-

making. Similarly, a fixed effects study of Tech-Prep programs, which promote articulation

agreements between high schools and community colleges, finds positive effects on high school

graduation and two-year college enrollment (Cellini, 2006).

An important aspect of the curriculum discussion is the extent to which high schools implement

tracking and whether there is variability and/or compression of schooling experiences. Effective

schools work to compress pre-existing variability by promoting equal and equitable access to

school resources and promoting the inclusion of all students in all aspects of the schooling

experience, in other words there is a focus on opportunities to learn. Effective schools also create

variable and differentiated experiences to meet the needs of diverse learners. Studies of how

schools organize students and teachers into courses and programs yield mixed results. Several

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 19

authors find that tracking through ability grouping is not an effective practice (Betts & Skholnik,

2000; Boaler & Staples, 2008); assigning all students to the highest track has been found to be both

beneficial (Burris, Wiley, Welner, & Murphy, 2008; Domina et al, 2011) and detrimental

(Allensworth, Nomi, Montgomery, & Lee) for student achievement. Cellini (2006) finds that

Tech-Prep programs may increase overall achievement while simultaneously diverting capable

students from four-year colleges.

More recently, the process of tracking students into courses in high school has shifted from a rigid,

deterministic model to more flexible curricular choice (Allensworth, Nomi, Montgomery, & Lee,

2009). Schools may also organize smaller schools within the full high school through academies or

other programs. Reorganizing schools by creating smaller “schools-within-schools” was found to

increase achievement and attendance (Darling Hammond, Ancess, & Ort, 2002). Small school

reorganization was found to be more effective when schools were “started-up” instead of converted

(Shear, Means, Mitchell, House, Gorges, Joshi, Smerdon, & Shkolnik, 2008). High school career

academies appear to increase student outcomes, but may not be cost effect or exceed the benefits of

taking more academic courses (Maxwell, 2002). While tracking practices are increasingly less

formal, “neotracking” through highly differentiated curricular choices tends to stratify by race and

class (Mickelson & Everett, 2008; Ready & Lee, 2008; Lucas & Berends, 2002; Heck, Price, &

Thomas, 2004; Lewis & Cheng, 2006).

Most of the literature describes the stratification and the potential dangers of allowing it to exist,

while falling short of offering best practices or policies to prevent or correct it. Mickelson &

Everett (2008) look at North Carolina high school student’s choice to pursue differentiated courses

of study (e.g., Vocational, College Preparatory) and report that this policy reproduces the

stratification by race and class of opportunities to learn, and conclude that graduates “may not be

prepared either for higher education or for the workplace” because of their curricular choices (p.

536). Lewis and Cheng (2006) analyze tracking and expectations through a survey of principals to

reconcile the finding that “socioeconomic status predicts the dominant track in schools” and

conclude that these stratifications may be a result of differential beliefs and expectations for certain

classes of students (p.91). Similarly, Iatarola, Conger, and Long (2011) study the factors

determining a school’s decision to offer IB/AP courses and find that schools choose to offer

advanced courses only when high-achieving students--in reality or perception--enroll in the school,

suggesting a lack of open access to advanced courses. The literature suggests that effective schools

should work to compress variability in course selection by race and class and ensure all students

have access to advanced courses (Muller, Riegle-Crumb, Schiller, Wilkinson, and Frank, 2010).

Effective schools may also create variability by offering transition classes (Gamoran, 1997),

schools-within-schools (Ready & Lee, 2008), career academies (Maxwell, 2002), college outreach

programs (Domina, 2009), and other differentiated programs to meet student needs. These

programs are targeted at subgroups within a school to meet a specific need, such as informing at-

risk students about the college application process. The findings on the effectiveness of these

programs are mixed, suggesting that the structures, programs or practices intended to create

variable experiences for certain subgroups are dependent on other key components, such as

Personalized Learning Connections or Quality Instruction.

We define Rigorous and Aligned Curriculum as vertical alignment of curriculum both between

grade levels and feeder schools, focus on increased enrollment and access to rigorous curriculum

like AP courses, and the degree of flexibility in the enrollment of courses, and in the

implementation of state and district curriculum and instructional calendars.

Conclusion

The National Center on Scaling up Effective Schools will follow a conceptual framework

developed from the effective schools literature in general as well as specific research on these

components as they pertain to high schools to research on these components are implemented

relatively highly effective, as measured valued -added measures, and less effective high schools.

These case studies will then inform the design of interventions for improving student learning and

reducing drop in a small sample of high schools in the same districts as the case studies. Although

the literature reviewed in this paper is not definitive, and it does point at the lack of depth of

empirical research on high schools, it does suggest that these components are plausible places to

focus in-depth inquiry into how to change high schools so more students reach successful

outcomes. We submit that these eight components are essential for the creation, transformation, or

sustaining of an effective high school. However, no component is sufficient, in and of itself, to

create or sustain an effective high school. The components overlap and intertwine with and support

each other to foster the conditions necessary for increased attachment and engagement, on the part

of all school community members, thereby improving student outcomes. These eight components

reviewed and conceptualized herein, with learning-centered leadership and a rigorous and aligned

curriculum as the anchors, taken together, are the essential components of effective high schools.

We set forth the hypothesis that trying to change the "DNA" of high schools in a fundamental way

through implementing and enhancing the work of teaching and learning and leading around the

core components will greatly enhance the engagement, commitments and achievements of high

school students and the adults who guide, teach and mentor them.

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 21

References

Adams, J. E., & Kirst, M. (1999). New demands for educational accountability: Striving for results

in an era of excellence. In J. Murphy & K. S. Louis (Eds.), Handbook of research in educational

administration (2nd ed., pp. 463–489). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Allensworth, E., Nomi, T., Montgomery, N, & Lee, V. (2009). College preparatory curriculum for

all: Consequences of requiring Algebra and English I for ninth graders in Chigaco. Educational

Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31, 4: 367-391.

Alper, L., Fendel, D., Fraser, S., & Resek, D. (1997). Designing a high school mathematics

curriculum for all students. American Journal of Education, 106:1, 148-178.

Anagnostopoulos, D. (2003). The New Accountability, Student Failure, and Teachers' Work in

Urban High Schools. Educational Policy, 17: 3, 291-316.

Anagnostopoulos, D., & Rutledge, S. (2007). Making sense of school sanctioning policies in urban

high schools: Charting the depth and drift of school and classroom change. The Teachers College

Record, 109(5), 1261–1302.

Anderman, L., Andrzejewski, C., & Allen, J. (2011). How do teachers support students’ motivation

and learning in their classrooms? Teachers College Record, 113, 5: 969–1003.

Applebee, A., Langer, J., Nystrand, M., & Gamoran, A. (2003). Discussion-based approaches to

developing understanding: Classroom instruction and student performance in middle and high

school English. American Educational Research, 40, 3: 685-730.

Ascher, C. (1988). Urban school-community alliances. New York: ERIC Clearinghouse on Urban

Education.

Bauch, P., & Goldring, E. (2000). Teacher work context and parent involvement in urban high

schools of choice. Educational Research & Evaluation, 6(1), 1-23

Becker, B.E., & Luthar, S.S. (2002). Social-emotional factors affecting achievement outcomes

among disadvantaged students: Closing the achievement gap. Educational Psychologist, 37(4),

197-214.

Berends, M. (2000). Teacher-Reported Effects of New American School Designs: Exploring

Relationships to Teacher Background and School Context. Educational Evaluation and Policy

Analysis. 22(1), 65-82.

Betts, J. R., & Shkolnik, J. L. (2000). The effects of ability grouping on student achievement and

resource allocation in secondary schools. Economics of Education Review, 19(1), 1–15.

Blasik, K., Williams, R., Johnson, J. & Boegli, D. (2003). The marriage of rigorous academics and

technical instruction with state-of-the-art technology: A success story of William T. McFatter

Technical High School. The High School Journal, 87, 2: 44- 55.

Boaler, J. & Staples, M. (2008). Creating mathematical futures through an equitable teaching

approach: The case of Railside School. Teachers College Record, 110, 3: 608–645.

Brown, B. (2008). Assessment and academic identity: Using embedded assessment as an

instrument for academic socialization in science education. Teachers College Record, 110:10,

2116-2147.

Carbonaro, W. (2005). Tracking, students’ effort, and academic achievement. Sociology of

Education, 78(1), 27–49.

Carbonaro, W. & Gamoran, A. (2002). The Production of Achievement Inequality in High School

English. American Educational Research Journal, 39, 4: 801-827.

Carlson, D., & Planty, M. (2011). The ineffectiveness of high school graduation credit requirement

reforms: A story of implementation and enforcement? Educational Policy, 20(10), 1-35.

Cellini, S. (2006). Smoothing the transition to college? The effect of Tech-Prep programs on

educational attainment. Economics of Education Review, 25, 394-411.

Chatterji, C. M. (2005). Achievement gaps and correlates of early mathematics achievement:

Evidence from the ECLS-K-first grade sample. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13(46).

Retrieved September 3, 2009, from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v13n46/v13n46.p

Cohen, J. (2006). Social, emotional, ethical, and academic education: Creating a climate for

learning, participation in democracy, and well-being. Harvard Educational Review, 76, 201–237.

Cohen, J., McCabe, L., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy,

practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record, 111(1), 180–213.

Cook, M. & Evans, W.N. (2000, October). Families or schools? Explaining the convergence in

white and black academic performance. Journal of Labor Economics, 18, 729-754.

Copland, M. A. (2003). Leadership of inquiry: Building and sustaining capacity for school

improvement. Educational Policy and Analysis, 25(4), 375-395.

Cothran, D., Kulinna, P. & Garrahy, D. (2003). ‘‘This is kind of giving a secret away...’’: students’

perspectives on effective class management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19, 4: 435-444.

Crosnoe, R. (2001). Academic orientation and parental involvement in education during high

school. Sociology of Education, 74, 3, 210-230.

Crosnoe, R., Johnson, M., & Elder, G. (2004). Intergenerational bonding in school: The behavioral

and contextual correlates of student-teacher relationships. Sociology of Education, 77, 1: 60-81.

Crosnoe, R. & Schneider, B. (2010). Social capital, information, and socioeconomic disparities in

math course work. American Journal of Education, 117, 1, 79-107.

Conceptualizing Essential Components of

Effective High Schools Conference Paper | February 2012 23

Curry, M. (2008). Critical Friends Groups: The possibilities and limitations embedded in teacher

professional communities aimed at instructional improvement and school reform. Teachers College

Record, 110 (4): 733-774.

Danielson, C. (2007). Enhancing Professional Practice: A Framework for Teaching. Alexandria,

VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Darling-Hammond, L. Ancess, J. & Ort, S. (2002). Reinventing high school: Outcomes of the

Coalition Campus Schools Project. American Educational Research Journal, 39, 3: 639-673.

Davies, D. (1995). Commentary. In L. Rigsby, M. Reynolds, & M. Wang (Eds.), School-

Community Connections. (267-280). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Davison, M.L., Young, S.S., Davenport, E.C., Butterbaugh, D., & Davison, L.J. (2004). When do

children fall behind? What can be done? Phi Delta Kappan, 85(10), 752-761.

DeBray, E. (2005). A comprehensive high school and a shift in New York State policy: A study of

early implementation. The High School Journal, 89(1), 18–45.

Dexter, K. M., Tai, R. H., & Sadler, P. M. (2006). Traditional and block scheduling for college

science preparation: A comparison of college science success of students who report different high

school scheduling plans. The High School Journal, 89(4), 22–33.

Dolejs, C. (2006) Report on Key Practices and Policies of Consistently Higher Performing High

Schools. American Institutes for Research.

http://www.betterhighschools.org/docs/ReportOfKeyPracticesandPolicies_10-31-06.pdf

Domina, T. (2009). What works in college outreach: Assessing targeted and schoolwide

interventions for disadvantaged students. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31(2), 127–

152.

Domina, T., Conley, A. M., & Farkas, G. (2011). The Link between Educational Expectations and

Effort in the College-for-all Era. Sociology of Education, 84(2), 93.

Domina, T. & Ruzek, E. (2010). Paving the way: K-16 partnerships for Hhgher education diversity

and high school reform. Educational Policy, doi:10.1177/0895904810386586.

Drago-Severson, E. (2007). Helping teachers learn: Principals as professional development leaders.

Teachers College Record, 109, 1, 70-125.

Eccles, J., Barber, B., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent

development. Journal of Social Issues, 59, 4: 865-889.

Elmore, R. F., Abelmann, C. H., & Fuhrman, S. H. (1996). The new accountability in state

education reform: From process to performance. In H. Ladd (ed) Holding schools accountable:

Performance-based reform in education, 65–98.. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Emerling, B. (2010). Tracing the effects of teacher inquiry on classroom practice. Teaching and

Teacher Education, 26, 377-388.

Englund, M., Egeland, B. & Collins, A. (2008). Exceptions to high school dropout prediction in a

low-income sample: Do adults make a difference? Journal of Social Issues, 64, 1: 77-94.

Fallis, R. & Opotow, S. (2003). Are students failing school or are schools failing students? Class

cutting in high school. Journal of Social Issues, 59, 1: 103-119.

Feldman, A. & Matjasko, J. (2005). The role of school-based extracurricular activities in

adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of Educational

Research, 75, 2: 159-210.

Feldman, M. & Pentland, B. (2003). Reconceptualizing organizational routines as a source of

flexibility and change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48, 1, 94-118.

Fernandez, K. E. (2011). Evaluating school improvement plans and their effect on academic