Complementary effects of clusters and networks on firm innovation: A conceptual model

Transcript of Complementary effects of clusters and networks on firm innovation: A conceptual model

J. Eng. Technol. Manage. 30 (2013) 1–20

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Journal of Engineering andTechnology Management

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jengtecman

Complementary effects of clusters and networks on firminnovation: A conceptual model

Devi R. Gnyawali a,1, Manish K. Srivastava b,*a R.B. Pamplin College of Business, 2011 Pamplin Hall, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061,United Statesb School of Business and Economics, 123 Academic Office Building, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931,United States

A R T I C L E I N F O

JEL classification:

L14

O32

Keywords:

Cluster

Network

Innovation barriers and catalysts

Vitality

Network orientation

A B S T R A C T

We develop a conceptual model that explains how a firm’s cluster

and network complement each other in enhancing the firm’s

likelihood of technological innovations. We identify critical

innovation catalysts-awareness and motivation—and innovation

barriers—resource constraints, organizational rigidity, and uncer-

tainty. Our conceptual model explains how various factors in the

cluster such as competitive intensity, social interaction intensity,

and cluster vitality and network factors such as resource potential,

acquisition orientation, co-development orientation, and network

vitality impact innovation catalysts and barriers and subsequently

the firm’s likelihood of generating incremental and breakthrough

innovations. We discuss several promising avenues for future

research.

Published by Elsevier B.V.

Introduction

Innovation is becoming increasingly critical for survival and growth of firms, but firms oftenstruggle to innovate (Ahuja and Lampert, 2001) partly because their internal resources andcapabilities become inadequate to engage in sustained technological explorations and resourcerecombinations (Fleming, 2001). Firms therefore seek resources from their strategic alliance networks(Ahuja, 2000a; Collins and Hitt, 2006; Phelps, 2010; Srivastava and Gnyawali, 2011) and geographicclusters (Ketelhohn, 2006; Pouder and St. John, 1996; Whittington et al., 2009) as these are valuable

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 906 487 1991; fax: +1 906 487 1863.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (D.R. Gnyawali), [email protected] (M.K. Srivastava).1 Tel.: +1 540 231 5021; fax: +1 540 231 3076.

0923-4748/$ – see front matter . Published by Elsevier B.V.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2012.11.001

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–202

reservoirs of external resources (Tallman et al., 2004). Clusters and networks, however, are likely towork differently with respect to the nature and flow of resources, therefore possibly resulting intotheir differential impact on firm innovation. Further, access to external resources does not necessarilylead to enhanced innovation unless the firm is motivated to pursue innovation opportunities and isable to overcome internal organizational barriers (Ahuja and Lampert, 2001). Our understanding ofthese important issues is limited as little research has systematically examined the mechanismsthrough which cluster and network conditions uniquely impact firm innovation. Accordingly, thepurpose of this paper is to address the following question: how do a firm’s cluster and networkconditions influence the firm’s likelihood of generating technological innovations?

In addressing the research question, we argue that in order to understand the specific effects ofcluster (defined as a set of co-located firms operating in related industries) and network (defined as aset of focal firm and its formalized partners) on innovation, researchers need to first understandfactors that may serve as barriers versus catalysts for innovation (Mohr, 1969). We therefore firstidentify important barriers that inhibit and important catalysts that enhance a firm’s likelihood ofgenerating technological innovations before discussing how they would be influenced by cluster andnetwork conditions. We suggest that competition and collaboration serve as underlying forces in bothcluster and network, but the ways in which they work and impact firm innovation differ between acluster and a network. We therefore use competition and collaboration as a basis for our theorizingand for identifying relevant constructs for our conceptual model. We build on prior research thatsuggests that competition in a cluster provides stimulus for innovation (Porter, 1998), and thatopportunities for informal interactions facilitate knowledge flow (Maskell, 2001; Saxenian, 1994;Tallman et al., 2004). In terms of network, we underscore the importance of resources stemming fromnetworks (Ahuja, 2000a; Baum et al., 2000; Powell et al., 1996) and argue that how a firm views itsnetwork and resources contained in it has important implications on the firm’s leveraging of suchresources in pursuit of innovations.

By building on prior literature (Chen et al., 2007; Chen, 1996; Porter, 2000; Saxenian, 1994), weargue that the primary role of a cluster lies in increasing a firm’s awareness of technologicaldevelopments and motivation to engage in innovation, and in reducing uncertainty in innovation.Further, we advance a concept of cluster vitality—the extent to which a cluster is imbued with newknowledge resources over time—, and suggest that cluster vitality is very critical for sustained flowof cluster benefits. In terms of network, we suggest that resource potential inside a network ishelpful in addressing important innovation barriers, but the extent and nature of networkresources a firm gains and leverages depend on the firm’s network orientation, i.e., how a firmviews and utilizes its network and the resources contained in them. We argue that a firm thatprimarily views its network as a way to acquire resources would derive benefits enhancing thelikelihood of, primarily, incremental innovations, whereas a firm that pursues its network for co-development of resources would derive benefits enhancing the likelihood of breakthroughinnovations. We further argue that network vitality—the extent to which a network is imbuedwith new knowledge resources over time—plays a critical role in realizing the specific resourcebenefits from the network.

We contribute to the innovation, cluster, and network literature in important ways. First, ouridentification and discussion of innovation barriers and catalysts provide insights into why and howfirms might struggle in their innovation efforts. An understanding of barriers and catalysts is a criticalfirst step in addressing them. Second, by explicitly developing cluster and network mechanisms andlinking them to innovation barriers and catalysts, we provide a theoretically richer base for futureresearch on how these important external conditions impact innovation pursuits and outcomes.Further, our conceptual model explains how cluster primarily strengthens the catalysts of innovation,and network primarily helps in overcoming the innovation barriers, and together how theycomplement each other in enhancing the likelihood of innovation. Third, the concepts of clustervitality and network vitality we advance in this paper provide an evolutionary perspective on clustersand networks and underscore the importance of temporal considerations in examining their effects.Finally, our conceptualization of network orientation provides novel insights on why and how firmsgain differently from their network resources and lays a very strong foundation for future conceptualand empirical research.

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–20 3

Conceptual background

Prior cluster literature suggests that clusters provide a common pool of resources (Krugman, 1991;Porter, 1990), opportunities for informal interactions and knowledge flow (Maskell, 2001; Tallmanet al., 2004), and stimulus for innovation via competition in the cluster (Porter, 1998). Moreover, sinceknowledge spillover tends to be geographically localized (Jaffe et al., 1993), membership in a clusterseems to provide access to knowledge residing in the cluster. Arikan (2009) suggests thatinnovativeness of cluster firms and breadth of their collective knowledge are critical for innovationopportunities created by cluster resources. However, the understanding of underlying mechanismsthrough which cluster influences firm innovation is rather limited. Similarly, prior research in thealliance network tradition has shown that a firm’s formal cooperative relationships or alliances withother firms contribute to innovation (Ahuja, 2000a; Baum et al., 2000; Powell et al., 1996). A firm’salliance network size (the number of partners), as an indicator of resourcefulness of the network, hasbeen shown to positively impact its innovation output (Ahuja, 2000a). Recent research delvesspecifically into various types of resources and demonstrates that diversity and quality of a firm’salliance network resources enhance the firm’s ability to generate innovations (Phelps, 2010;Srivastava and Gnyawali, 2011). While this growing body of literature has established that a firm’snetwork is a major source of external resources, we know little about how the characteristics of thefirm’s network influence its ability to overcome different innovation barriers. Moreover, althoughfirms’ networking behaviors are likely to be driven by both competition and collaboration motives(Madhavan et al., 2004), we know little about how these motives might manifest in the firms’ networkconfigurations and impact their innovation outcomes.

Further, even though cluster and network research have evolved along different trajectories, recentresearch suggests that cluster and network could play complementary (Zaheer and George, 2004) oreven substituting roles (Whittington et al., 2009). Highlighting the complementary roles, Zaheer andGeorge (2004) note that being located in a geographic cluster is not enough for effective knowledgesourcing; firms need to have access to alliance network to achieve resource flows. In contrast,indicating a partial substitution effect between clusters and alliances, Whittington et al. (2009) findthat a firm’s positions in the global network and the local network have partial substitution effect onthe firm’s innovation output. Further, implying complementary roles, McCann and Folta (2011) positthat the effects of a cluster on innovation increases with increasing alliance experience. These recentdevelopments in the literature suggest promising roles of a firm’s cluster and network conditions oninnovation and underscore the importance of explicating the underlying mechanisms through whichthe effects would occur.

Our dependent construct is technological innovation, i.e., innovation generated throughtechnological means (Utterback, 1971). Technological innovation could be ‘‘an invention whichhas reached market introduction in the case of a new product or first use in a production process, in thecase of a process innovation’’ (Utterback, 1971, p. 77). Technological innovations are oftencharacterized as incremental or breakthrough; both types of innovations are important for survivaland growth of firms. Incremental innovations involve low degree of new knowledge recombinationand relatively minor improvements in current technologies or products (Dewar and Dutton, 1986;Phelps, 2010). Innovations that are breakthrough (Dewar and Dutton, 1986; Srivastava and Gnyawali,2011; Zhou et al., 2005) serve as the basis for many subsequent technological developments (Ahujaand Lampert, 2001), break new grounds for the firm, and lead to state of the art technological advances(Zhou et al., 2005).

In order to understand better how and why clusters and networks impact firm innovation, weunderscore the need to first understand factors that are important for innovation (Dosi, 1997;Dougherty and Hardy, 1996; Mohr, 1969; Rosner, 1968). Mohr (1969, p. 63) stressed that ‘‘innovationis directly related to the motivation to innovate, inversely related to the strengths of obstacles toinnovation, and directly related to the availability of resources for overcoming the obstacles.’’ Drawingupon the awareness, motivation, and capability perspective (Chen et al., 2007; Chen, 1996) that ishelpful in understanding firm behavior, we suggest that the pursuit of technological innovations by afirm begins with awareness: the firm needs to become familiar with relevant technological trends andforces in order to see fruitful innovation opportunities. Further, the firm needs to realize the need to

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–204

engage in innovation or ought to be motivated to do so. The ability to innovate, which often is based onresource endowments, is important but is relevant only when the firm is aware of importanttechnological trends and is motivated to engage in innovation. Our identification of innovation barriersand catalysts and subsequent discussion of cluster and network effects is based on this core point.

Innovation barriers

Firms often struggle or even fail in their innovation efforts due to several obstacles (Mohr, 1969).Based on our review of the innovation literature, we identify three barriers as being the most critical:resource constraints (Mansfield and Rapoports, 1975; Mone et al., 1998), uncertainty (Abernathy andUtterback, 1978), and organizational rigidity (Ahuja and Lampert, 2001; Dougherty and Hardy, 1996).Resource constraints indicate that the firm does not have the means, uncertainty indicates that thefirm does not know what to do, and rigidity indicates that in spite of knowing what to do and havingthe means the firm still may not be able do it because of resistance from its internal systems andprocesses and managers’ mindsets. These barriers act like clogs in a pipe—unless the focal firm is ableto overcome all key innovation barriers, its ability to innovate on a sustained basis will be very limited.We discuss below each of these barriers before explaining why and how a firm’s cluster and networkconditions might help it to mitigate the barriers and become more innovative.

Resource constraints

Resource constraints refer to the lack of the amount and type of inputs (such as technology and know-how) required for pursuing innovations. It is not just the volume of resources that matter, but the varietyof available resources is also critical. Resources are required to search for ideas, conduct experiments,pursue multiple projects, develop and test prototypes, and launch new products. Firms often struggle ininnovation due to resource constraints (Ahuja and Lampert, 2001; Dougherty, 1996; Galia and Legros,2004; Mone et al., 1998). The resource constraints become an even bigger barrier in case of researchprojects that involve pursuits of breakthrough innovations (Carbonell and Rodrıguez-Escudero, 2009;Srivastava and Gnyawali, 2011). While firms could attempt to develop resources internally, factors suchas path dependency, causal ambiguity, and time pressure debilitate their ability to develop resourcesinternally (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Dierickx and Cool, 1989). Sometimes it may not be economicallyworthwhile to develop resources internally when the focal firm requires them for a limited purpose.Changing environmental conditions warrant different types of resources and capabilities over time andthus create a gap between the current organizational resources and the resource requirements in orderto generate innovations (Grant and Baden-Fuller, 2004).

Uncertainty

Innovation entails, among other things, assessing the technological trends in the externalenvironment, knowing which technology or product has the most potential, and learning throughtrials and errors. Each of these things, however, involves high degree of uncertainty (Dickson andWeaver, 1997). Rapidly changing technologies, existence of multiple technology options, andtechnological convergence and divergence make it very difficult for a single organization to understandand deal with these conditions, discern a promising innovation path, and commit valuable resources for aparticular innovation path (Carbonell and Rodrıguez-Escudero, 2009; Folta, 1998; McGrath, 1997).Uncertainty makes it difficult for managers to accurately assess the current situation and future changes(Dickson and Weaver, 1997, p. 405) and to discern the desirable properties of the product, technologicalattributes, and configurations, and to predict the demand pattern (McGrath, 1997).

Organizational rigidity

Organizational rigidity—the inability of the organization to undertake new initiatives—serves as amajor innovation barrier, which is well recognized in the literature (Ahuja and Lampert, 2001;Dougherty and Hardy, 1996; Mohr, 1969). Organizational rigidity stems from deeply ingrained or

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–20 5

difficult to change mental models of the dominant coalition (Cyert and March, 1963; Hambrick andMason, 1984), established organizational routines (Nelson and Winter, 1982), and organizational culturethat values conformity and continuity. Because decision makers’ mental models influence how theyperceive opportunities and act on them (Hambrick and Mason, 1984), managers with deeply ingrainedmental models may not be able to notice and value new and critical technological trends. A myopicmindset may constrain managers’ ability to see value in many attractive projects (Levinthal and March,1993). Even if they notice some, they may not be willing to try out new things (Ahuja and Lampert, 2001;Rosner, 1968). Established organizational systems and processes that translate into regularly practicedroutines (Nelson and Winter, 1982) serve as another major source of rigidity (Leonard-Barton, 1992).Even though routines help to ensure coordination, reliability, efficiency, and control (Becker, 2004), thesame routines become ingrained in daily practices over time and resist the changes that are necessary forinnovation. Innovations are also likely to disturb the organizational truce (Kaplan and Henderson, 2005;Nelson and Winter, 1982). Many lucrative innovation projects may be rejected if they do not fit withcurrent organizational routines. While fostering innovation requires incentive system and culture thatreward experimentation and change, people fear and resist changes in the power structure andreallocation of organizational resources (Kaplan and Henderson, 2005).

Even more importantly, crippling effects would occur when multiple innovation barriers existsimultaneously and reinforce each other. For example, the resource barrier intensifies when the focalfirm enters into unfamiliar technological territories on its own. The innovation process becomes moreuncertain when the firm lacks the technical know-how and it does not have access to the know-how toundertake an innovation project. Organizational rigidity further intensifies in the face of uncertainty(Mone et al., 1998), making it difficult to get the critical mass (key managers of the organization) toagree on projects and commit resources to them. Thus, while each of the innovation barriers is criticalon its own, these barriers, in combination, make it extremely difficult for a firm to pursue innovationsrelying solely on its internal resources.

Innovation catalysts

While barriers inhibit the likelihood of innovation and therefore need to be minimized, catalystsincrease the likelihood and therefore need to be fostered. Research suggests that central enablers ofinnovation are awareness of technological trends and opportunities and motivation to innovate (Dosi,1997). In the economics literature, the presence of competitive conditions that motivate firms toengage in innovation is long recognized since Schumpeter’s early ideas about creative destruction.

Awareness

Awareness refers to a firm’s noticing of new technological developments and emerging markettrends that often result from the initiatives undertaken by competitors and other related firms (Chenet al., 2007; Chen, 1996). An understanding of the nature of new technologies developed bycompetitors and other firms and how they impact the focal firm would make the firm realize better theneed for innovation and take actions to do so. Increased awareness would make the firm moreaggressive (Chen, 1996) in initiating and launching promising innovation projects, and more likely tospeed up an existing project, or shelve a project that may not be appropriate given the competitive andmarket conditions. Awareness also helps in making more informed resource commitments. Noticing anew idea or finding a new opportunity may spur innovation efforts and help the firm in using itsresources and capabilities for generation of innovation more effectively or even developing/accessingnew capabilities for that purpose.

Motivation

Motivation refers to the firm’s willingness to engage in exploration and to garner as well as commitresources for innovation. Motivation influences a firm’s search intensity—the amount of efforts a firmdevotes to search for knowledge, new ideas, and new resources. A firm’s motivation for innovationcould come from pressure from competitors to be innovative, expected payoffs from innovation, and

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–206

availability of resources for innovation (Schumpeter, 1934). Lack of competition can lead to littlemotivation for innovation. As Apple’s former CEO Steve Jobs in explaining the reasons for Apple’sfailure in 1990s said, ‘‘what is the point of focusing on making the product even better when the onlycompany you can take business away from is yourself?’’ (Burrows, 2004). Firms with strongmotivation make concerted efforts to identify innovation opportunities, devote necessary resourcesfor innovation projects, and engage more deeply and systematically in innovation tasks, andconsequently increase the likelihood of successful innovations.

Role of cluster and network mechanisms

We define cluster as collection of firms operating in related industries (Arikan, 2009) that aregeographically proximate to each other. For the purpose of isolating the effects of cluster mechanisms,we assume an absence of inter-firm formal cooperative relationships within the cluster. We define afirm’s network as the set consisting of the focal firm (ego) and firms (alter) with whom the focal firmhas formalized cooperative relationships, along with all formal ties among those alters. This is alsoreferred to as an ego network (Everett and Borgatti, 2005). Formal modes of collaboration providestructured ways of knowledge flow among firms in a network.

We argue that competition and collaboration are at the core of both clusters and networks.However, these mechanisms operate at different levels and have different effects in clusters andnetworks. The intellectual heritage of competitive and collaborative mechanisms in the clusterliterature comes from the perspectives of Porter and Saxenian, respectively. Michael Porter in hisinfluential works (Porter, 1990, 1998, 2000) clearly suggested that the presence of competition amongco-located firms is the fundamental driver of the benefits from a cluster, but the literature has ratherignored this core driver while examining the benefits of clusters. Marshall (1920), Arrow (1962) andRomer (1986), on the other hand, argued that co-located firms generate knowledge externalities dueto specialization of firms operating in related industries. Their arguments led to the development of‘‘knowledge in the air’’ thesis (Marshall, 1920; Tallman et al., 2004), which suggests that informalknowledge spillovers in clusters make the co-located firms privy to the spillover. The findings relatedto geographic localization of knowledge spillover (Jaffe et al., 1993) and importance of geographicproximity in sharing of tacit knowledge (Polanyi, 1966) strengthened the importance of ‘‘knowledgein the air’’ thesis. Saxenian (1994) provided further clarity to this hypothesis by underscoring theimportance of informal communities and social interactions in such communities. She argued thatinformal social interactions in such communities serve as a backbone for knowledge spillover. Whilecompetition occurs at the firm level, informal interactions and exchanges occur generally at theindividual level. Accordingly, we select the two most important constructs, competitive intensity andsocial interaction intensity, capturing the core underlying mechanisms regarding a cluster’s benefits.

The intellectual heritage of competitive and collaborative or social mechanisms in inter-firmnetworks comes from the perspectives of Burt (1992) and Coleman (1988), respectively. According toBurt (1992), network based advantages arise from the absence of relationships among some players orthe existence of structural holes. Absence of relationships creates structural holes, which leads topartners competing with each other for the access to network resources or to counter others’ advantages(Madhavan et al., 2004). In contrast, Coleman (1988) argued for network-based advantages arising fromtrust, mutuality, and shared norms in cooperative relationships. This perspective emphasizes theimportance of relational exchanges and working together for greater common purposes (Madhavanet al., 2004). Based on these competing perspectives, we argue that firms differ in their networkorientations and therefore we would see two contrasting approaches of network configurations drivenby competitive or collaborative mindsets. Firms that enter into cooperative agreements driven by acompetitive perspective would configure their networks very differently than firms that view theirnetwork from a more collaborative perspective to build and nurture mutual relationships. Accordingly,we conceptualize such network orientations as ‘acquisition orientation’ and ‘co-development orientation’respectively. Because our focus is on resources and their roles, we identify network resource potential asa critical construct that represents resource endowment of the focal firm’s network and argue thatnetwork orientations have differential effects on the extent to which firms realize the potential providedby their network resources.

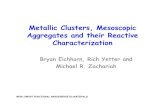

Cluster Factors• Compe��on intensity•

•

•

•

Social interac�on intensity Innova�on Catalysts• Awareness• Mo�va�on

Innova�on Barriers• Resource

Constraint• Uncertainty• Organiza�onal

Rigidity

Network FactorsNetwork resource poten�alAcquisi�on orienta�on

Co-development orienta�on

Likelihood of Innova�on• Incremental Innova�on• Breakthrough Innova�on

Cluster Vitality

Network Vitality

Fig. 1. A conceptual model of cluster and network effects on innovation.

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–20 7

Conceptual model and propositions

We develop our conceptual model in this section based on the research gaps and backgrounddiscussed in the preceding section. We graphically depict the model in Fig. 1. We suggest that theeffects of cluster lie primarily in terms of influencing awareness and motivation—the catalysts ofinnovation—, and in reducing the uncertainty barrier. Specifically, we argue that high intensity ofcompetition in a cluster contributes to increase in firms’ awareness of new technologicaldevelopments within the cluster and increases their motivation to engage in innovation. Further,high social interaction intensity in a cluster helps to reduce the uncertainty barrier by providingexposure to a wide range of ideas and knowledge from the communities of experts located in thecluster. We also suggest that cluster vitality leads to more effective realization of benefits ofcompetition intensity and social interaction intensity within the cluster. While resource benefits in acluster are rather indirect because of the lack of structural mechanisms for resource flows betweenfirms, the effects of network stem mainly from resources in the network because formalizedmechanisms for resource flows exist in the network. However, the extent and nature of benefitsdepend on the firm’s network orientation, i.e., how the firm views the network and consequentlymobilizes resources contained in it. Differences in the firms’ network orientations are fundamental tothe differential effects of networks on firms’ innovation outcomes. We further discuss how theeffectiveness of acquisition orientation and co-development orientation is influenced by networkvitality. We develop below specific arguments linking the cluster and network mechanisms with theinnovation constructs and state our propositions.

Cluster competition intensity

Cluster competition intensity refers to the extent to which firms located in a cluster engage insimilar products and markets and thus are rivals to each other. Prior literature has long recognized therole of competition on firm innovativeness (Geroski, 1990). However, the presence of competitors ingeographic proximity adds an important dimension to competition (Carroll and Wade, 1991). Co-location of competitors increases competition intensity (Cattani et al., 2003) in the input factor marketas well as in the output factor market. Survival and growth of these firms often hinges on their ability

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–208

to offer superior products and possibly at lower prices. Consequently, innovation becomes the basisfor firm survival and growth (Porter, 2000). We suggest that competitive intensity in a focal firm’scluster enhances the firm’s innovation outcomes primarily by increasing the firm’s awareness of newdevelopments, motivation to engage in innovation projects, and consequently its heightenedinnovation efforts.

Due to geographic proximity, the behavior of next door competitors becomes much more visible(Pouder and St. John, 1996), and therefore it poses much stronger perceived threats. Additionally, thegeographic proximity also makes it easier for a focal firm to monitor its co-located competitors’actions more frequently and more closely (Porter, 2000). As the firm tracks those competitors withgreater intensity, it becomes even more aware of the new technological undertakings of thosecompetitors (Lomi and Larsen, 1996; Pouder and St. John, 1996). High awareness of thesetechnological developments encourages the firm to search for related technological developmentseven elsewhere. Similarly, other co-located firms’ behavior is also influenced by the focal firm’sbehavior. As the co-located firms enhance their innovation efforts, the total volume of knowledgepotentially available for spillover also increases. However, the knowledge spillover in a cluster is in ahighly fragmented form (Caniels and Romijn, 2005). Even more, due to the lack of formal firm-to-firmstructural mechanisms for resource exchange/sharing, the fragmented spillover is not accompaniedby flow of organizational resources. As the spillover is in a highly fragmented form, it often imbibesknowledge in the form of ideas and information. Therefore, fragmented spillovers could initiate thecluster firms to many new technological initiatives in the cluster which in turn contribute toenhancing both the awareness of innovation opportunities and the motivation to innovate.

Overall, greater awareness of technological developments and opportunities provides new ideasand impetus for innovation, high perceived threats from competitors provide strong motivation toengage in innovation projects, and available opportunities to informally learn from co-locatedcompetitors and their innovation initiatives provide valuable insights in the innovation process. Allthese would improve the quality of the focal firm’s innovation projects and the intensity of itsinnovation pursuits and subsequently enhance its innovation outcomes. We therefore propose that,

Proposition 1. The higher the competitive intensity within a firm’s cluster, the higher the likelihood ofinnovation by the firm primarily through (a) increased awareness of technological developments and (b)increased motivation to innovate.

Cluster social interaction intensity

Social interaction intensity refers to the frequency with which employees of a firm informallyinteract with employees of other cluster firms and engage in informal knowledge sharing (Arikan,2009). Two primary ways of social interaction in a cluster are (a) informal information exchangesthrough occasional and ad hoc encounters in local conferences, training programs, and other informalsettings and (b) mobility of employees within the cluster. Social interaction intensity is considered asone of the most effective mechanisms for knowledge sharing and transfer (Noorderhaven and Harzing,2009). Geographic proximity provides opportunities to socialize often through informal gatheringsduring and after work hours. Such social interactions play an important role in the flow of informationand knowledge within the cluster (Lissoni, 2001; Saxenian, 1994). Similarly, geographic proximityspreads information about new job opportunities and increases the chances of employees changingemployers within the cluster. Employees are often considered as ‘knowledge-carriers’ and when theymove they often carry and ‘transplant’ individual-level knowledge embedded in them (Almeida andKogut, 1999). Because employees more often move to firms within a cluster than to firms outside acluster (Almeida and Kogut, 1999; Breschi and Lissoni, 2009), such knowledge is primarily accessibleto cluster firms. Opportunities to talk about and hear each other’s views on industry and technologicalchanges and about new technological pursuits would help the employees shape and refine theirinnovation ideas and thereby reduce uncertainty in several important ways.

First, high social interaction helps to develop a common body of core knowledge or cluster-specificknowledge (Tallman et al., 2004) within a cluster. Such interactions over time also help to refine thecluster-specific knowledge and build subsequent innovations on such core body of knowledge with

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–20 9

greater confidence. Technological uncertainty gets reduced when cluster-specific technologicalknowledge serves as a core platform for subsequent knowledge generation and innovation. Second,opportunities to interact with each other often in informal settings (Cattani et al., 2003) helpemployees exchange information regarding technological trends and market conditions (Lissoni,2001; Saxenian, 1994) and know about the market ‘‘buzz’’ as well as new product developmentinitiatives of various firms within the cluster (Dahl and Pedersen, 2004). Employees may also shareinformation regarding current innovation initiatives in their teams, divisions, or companies. Moreinformation sharing about their innovation struggles and innovation initiatives helps to refine ideasand projects and reduces uncertainty associated with their own projects. Finally, high socialinteraction among cluster firms may also allow the flow of valuable market feedback on innovationprojects, help discern a viable innovation path, and may help commit resources in pursuit of that path.Informal feedbacks from a variety of sources about the technology and markets serve as a basis to dropsome initiatives or build more commitment to others. The more information a focal firm gets about thenew product development initiatives of other firms, about new technological developments in theindustry, and about market response to the innovation efforts, the more confidently it could channelresources for the viable projects and put forth concerted efforts on the projects.

It is important to note that social interaction is a double-edge sword: while social interaction doesbring in information and knowledge from other firms, it is also a source of knowledge leakage from thefocal firm. The co-located competitors become more motivated to ‘‘soak’’ knowledge from the firm andthe geographic proximity enhances the co-located competitors’ ability to do so. The co-locatedcompetitors can also identify and ‘‘poach’’ focal firm’s employees with critical knowledge more easily.The focal firm may witness greater attrition of valuable employees when it is located in such a cluster.Thus, high social interaction intensity increases the chances of knowledge leakage, and co-locatedcompetitors may make more systematic efforts to absorb the knowledge. We suggest that whileknowledge spillovers through informal interactions occur very quickly, the damage would be ratherlow due to the highly fragmented nature of the interactions and spillovers. Further, employee mobilitymay carry knowledge possessed by individuals, but not the firm-level knowledge (Lissoni, 2001). Thus,despite potential spillover, firms are more likely to keep their knowledge private and use clusterknowledge in order to reaffirm and refine their own knowledge. The positive benefits of reducedinnovation uncertainty and increased innovation capability are therefore likely to outweigh thepotential downsides. We therefore propose that,

Proposition 2. The higher the social interaction intensity within a firm’s cluster, the higher the likelihoodof innovation by the firm primarily through reduced uncertainty.

Competitive intensity and cluster social interaction intensity together play complementary rolesfor innovation related benefits from geographic clusters. Presence of both would be very important forsubstantial benefits from clusters. Competitive intensity enhances the awareness and motivation toinnovate, and social interaction intensity provides the basis for the flow of information, ideas, and, to acertain extent, knowledge, and helps building commitments on innovation projects. However, thecluster could become homogenized over time due to cross-fertilization, mobility of employees, andisomorphic pressures. We now turn to the importance of cluster vitality for the effectiveness ofcompetitiveness intensity and social interaction intensity.

Cluster vitality

Cluster vitality refers to the extent to which a cluster is imbued with new knowledge resourcesover time. Increasing cluster vitality indicates conditions conducive for further innovation within thecluster (Arikan, 2009). New knowledge resources could occur through three primary means: locationof new firms within the cluster, inflow of new employees from outside the cluster, and enhancementof the knowledge of existing cluster firms. If new firms and employees from outside do not move to thecluster or if existing firms do not rejuvenate themselves, the cluster over time becomes morehomogenized (Pouder and St. John, 1996), lacks fresh ideas, and therefore firms within the cluster facegreater risks of spatial myopia (Maskell and Malmberg, 2007).

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–2010

Cluster vitality could decline due to crowding of firms. When crowding occurs, the cluster loses itsmagnetic power (Porter, 1990) to attract new firms and employees from outside the cluster. Since newfirms are often fountainheads of new knowledge, new ideas, and new resources (Geroski, 1990), lack ofnew firms in the cluster limits their inflows. As a result, crowding would adversely impact the resourceconditions within the cluster. As pointed out by Pouder and St. John (1996), crowding is more likely tooccur during the more mature stage of a cluster’s life cycle.

We argue that competitive intensity and social interaction intensity are not very effective whencluster vitality is low. One of the core underlying drivers of competitive intensity comes from thepower of competitive actions (Chen, 1996) undertaken by competitors that can change thecompetitive equilibrium. As fewer new ideas come to the cluster, innovative actions that are based onrather older ideas become increasingly less capable of disturbing the competitive equilibrium.Consequently, the power of the innovative actions undertaken by competitors goes down and thecompetitive intensity loses its bite—its power to coerce firms to enhance their innovation efforts goesdown. While social interaction still contributes to knowledge spillover, that spillover contains veryfew new ideas or fresh approaches. Due to continued recirculation of mostly existing ideas, thespillover does not contribute to generation of new ideas. The cluster-level beliefs about technologiesand market become more dominant and persistent (Pouder and St. John, 1996). Consequently, thecluster as an entity becomes devoid of new ideas and also less receptive to outside ideas. Thus, lack ofcluster vitality coupled with high social interaction intensity exacerbates the problem as older ideasthat contribute to reinforcement of existing beliefs get recirculated at a rather rapid rate.

Proposition 3. The lower the vitality of a firms’ cluster, the lower the effects of cluster competitiveintensity and cluster social interaction intensity on the likelihood of innovation by the firm.

As discussed above, cluster benefits are mainly in terms of increased exposure to opportunities,increased motivation to engage in innovation, and reduced uncertainty through informal learningfrom cluster members. We argue below that the effects of network lie in access and utilization ofpartners’ resources, which are helpful in reducing the resource constraints and organizational rigiditybarriers. Accordingly, resource potential of a network becomes a critical factor for a firm to deriveinnovation related benefits from the network, which we discuss next.

Network resource potential

Network resource potential refers to the amount and diversity of resource endowments of a focalfirm’s alliance partners. The greater the number of partners and their resource endowments, thehigher would be the focal firm’s network resource potential. We build on the prior literature thatunderscores the importance of network resources (Ahuja, 2000a; Burt, 1992; Coleman, 1988; Phelps,2010; Srivastava and Gnyawali, 2011) and argue that when network resource potential is high, thefirm’s likelihood of innovation increases by lowering both the resource barrier and the organizationalrigidity barrier.

High network resource potential helps the focal firm in addressing the resource barrier in severalways. First, the availability of more resources encourages the firm to engage in more experimentation,which lies at the core of the innovation process (Thomke, 2003) and requires significant amount ofresources. With more resources available, the firm could push more of the promising experimentationprojects into the development stage, scale-up the prototypes, and take more of the projects already inthe development stage closer to their commercial launch. As a result, fewer projects will meet theirpremature death due to the paucity of resources. Second, having more partners and access toresources of those partners also indicates that the firm enjoys higher status (Wasserman and Faust,1994), which further increases its visibility and reputation as a partner. As a result, the firm can attractmore resource rich partners (Gulati, 1999). With new partners and new resources, it could moreeffectively pursue more resource intensive innovation projects and pursue them with greater vigor.Finally, firms of higher status also have the power of endorsement (Stuart, 2000), which is likely tobring opportunities not easily available to others who lack such power (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978). Forinstance, the lower status firms in order to get connected with the high status focal firm may offer thefocal firm a preferential access to their current and future resources (such as sharing new product

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–20 11

development activities and offering early previews of technologies and products), which in turn wouldincrease the innovation likelihood of the focal firm.

While volume of resources is important, diversity of resources could be even more important inorder to develop and integrate a wide range of technologies and deal with technological convergence(Srivastava and Gnyawali, 2011). Diversity of resources could be achieved by having many partnersthat possess unique resources or a few partners with diverse resource profiles. When the partners andtheir resources are diverse, the firm can search broadly and access different types of resources andcapabilities possessed by the partners. Diversity of resources provides the firm a broader horizon,wider range of options for exploration of ideas, and increased ability to perform recombinatory search(Fleming, 2001). The availability of heterogeneous resources thus not only equips the firm to pursuedifferent permutations and combinations but also provides it with the means to realize those ideasand reject fewer lucrative projects. Taken together, partners that are endowed with a larger volumeand wide variety of resources help the focal firm to reduce resource constraints, a critical barrier thatcripples firms’ innovation efforts.

Proposition 4a. The higher the network resource potential of a firm, the higher the likelihood ofinnovation by the firm primarily through the reduction of resource constraints.

High network resource potential through access to volume and diversity of resources also helps thefocal firm in coping with the organizational rigidity barrier (Leonard-Barton, 1992). Two sources ofrigidity are important in our context: decision makers’ cognitions and organization’s systems andprocesses (Leonard-Barton, 1992; Tripsas and Gavetti, 2000). Two important options for overcomingthese barriers could be reducing those barriers or bypassing them. Reduction of cognitive barriers isnecessary for managers to engage in pursuit of novel solutions. Once cognitive barriers are reducedmanagers can now attempt to reduce or bypass the barriers arising from internal systems andprocesses. Access to partners with rich and diverse resources provides the managers with greaterexposure that would help them reduce their cognitive barriers. Srivastava and Gnyawali (2011, p. 799)argue ‘‘exposure to partners’ diverse technologies broadens the firm’s perspective and increases itsability to see fruitful opportunities that may arise at the confluence of multiple technologies’’.Increased exposure would widen the managers’ views and therefore make them less myopic and makethem more motivated to search for solutions more broadly (Sampson, 2007). The broader search forsolutions makes the managers more willing to accept different ways of doing things and differentapproaches to problem solving (Tripsas and Gavetti, 2000).

Access to diverse resources of partners could also be helpful in overcoming barriers stemming fromthe rigid systems and processes. Instead of attempting to change internal systems and processes fornovel pursuits, managers could opt for bypassing them. Formal partnerships between firms withdifferent resources allow them to create novel solutions while bypassing their internal barriers. Forinstance, as one manager whose firm has a collaborative project with Google mentioned (personalcommunication), most of the time when he refers to this strategic partnership, he gets little internalresistance and does not have to follow rigid internal steps. Similarly, the focal firm could use partners’systems and processes to pursue innovation projects or could jointly create new systems andprocesses instead of making struggling attempts to change internal ones. Both scenarios would lead toreduced role of internal rigidity in pursuit of innovations.

Proposition 4b. The higher the network resource potential of a firm, the higher the likelihood ofinnovation by the firm primarily through the overcoming of organizational rigidity.

The network resource potential creates enabling conditions for the firm to enhance its innovationgeneration capabilities by allowing it to access and acquire network resources. But the extent to whichthe firm actually benefits from the resource potential would depend upon how the firm views andmobilizes the network resources. As we noted earlier, literature on inter-firm network has offered twosomewhat opposing views on network and their roles: structural hole versus closure (Burt, 1992;Coleman, 1988). The former has a more competitive orientation whereas the latter has a morecollaborative orientation (Madhavan et al., 2004). As we noted earlier, by building on these centralideas and putting them in the context of resources and innovation, we argue that firms predominantly

Table 1Acquisition and co-development network orientations.

Acquisition orientation Co-development orientation

Managers’ view of

network and its role

on innovation

� Network and ties viewed as means to get

specific resources and other support to

enable the focal firm to pursue its own

innovation priorities

� Network and ties viewed as a way to combine

partners’ resources and capabilities, create

new ones, and jointly explore new

technologies and pursue common innovation

priorities

� Locus of innovation is internal efforts � Locus of innovation is joint efforts

Network’s structural

conditions

� Large but sparse network � Small and dense network

� Many partners with mostly bilateral ties � Fewer partners and mostly multilateral ties

� High structural autonomy � Low structural autonomy

� High centrality of focal firm

Network’s nodal

characteristics

� Highly resourceful partners with overlapping

resources and capabilities

� Highly resourceful partners with

complementary resources and

tacit knowledge

� Focal firm more powerful than others

Network ‘s relational

conditions

� Ties with fixed purpose and low multiplexity � Repeat, long term, and multiplex ties

� Limited trust between partners � High trust between partners

� R&D and exploration ties

Inter-organizational

mechanisms

� Pooling of volume of resources � Combining partners’ resources and

capabilities in a new way

� Formal, contractual exchanges

(can be one-way or quid pro quo)

� Greater reliance on relational mechanisms

� Informal intelligence gathering � Joint problem solving

Time horizon � Short term � Longer term

Nature of resources

involved

� Mostly explicit knowledge and

tangible resources

� Mostly tacit knowledge and intangible

resources

� Volume of resources is critical � Variety of resources is critical

Primary innovation

barriers addressed

� Lack of volume of resources � Lack of diversity of resources

� Greater resolution of market uncertainty � Greater resolution of technological

uncertainty

� Reduction of internal rigidity

Innovation outcomes � Limited likelihood of breakthrough

innovations

� Greater likelihood breakthrough innovations

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–2012

adopt one of the two network orientations—acquisition or co-development—which in turn leads todifferences in the ways in which they mobilize their network resources for innovation. Table 1provides an illustrative summary of these two orientations. Although these two orientations are notmutually exclusive and firms may exhibit elements of both orientations, we examine them and theireffects separately for conceptual clarity.

Acquisition orientation

Acquisition orientation refers to the firm’s view of network as a way to gain information,knowledge, and other resources from the partners and pursue innovation projects on its own. Thelocus of innovation in this case is the firm rather than the partnership. As indicated in Table 1, severalconditions characterize acquisition orientation of a firm’s network. An acquisition oriented network isstructured in such a way that the focal firm can access resources of a large number of partners, thusleading to many ties in the firm’s network, but sparse inter-partner ties. Similarly, in such a network,the focal firm is likely to be more powerful than the partners so that it can more easily acquireresources from the partners. The firm also views the network with a shorter time horizon withfrequent churning of partners (Koka et al., 2006) and eschews making rather long term commitments.Further, in a such a network, the presence of inter-organizational mechanisms for knowledge sharing

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–20 13

(Dyer and Singh, 1998) is essential because existence of knowledge transfer routines facilitates regularand systematic flow of resources from the partners. By being able to mobilize its network resourcesthrough the ties, the focal firm is able to enrich its resource base.

A firm with the acquisition orientation is likely to increase its overall resource base and utilize suchresources for its innovation needs. Enhanced resource strength would then be used by the firm topursue innovations on its own rather than working with others in joint pursuits. Because openexchanges and interactions are unlikely to take place with the partners, the firm is more likely to getexplicit knowledge and general resources rather than tacit knowledge and complex resources. Further,the firm’s innovation projects and innovation pursuits are likely to be limited to what it already knowsbest. Acquisition orientation implies a competitive intent with the goal of out-learning the partner(Hamel, 1991) and taking advantage of information asymmetry (Burt, 1992). Such a competitivebehavior would make its partners rather suspicious and they may not share their best resources. Takentogether, while these resource conditions and partnering behavior would contribute to the firm’sability to undertake more innovative projects, but the nature of such projects is likely to be moretoward well understood and familiar than toward rather unfamiliar, risky, and resource-intensive.Therefore, acquisition orientation is less likely to increase the firm’s capability to generatebreakthrough innovations that require combination and blending of multiple resources, undertakingof major risky projects, and investment of a large amount of resources. Based on the above reasoningwe propose that

Proposition 5. A firm with an acquisition orientation of its network is likely to be effective in generatingmore incremental innovations than breakthrough innovations.

Co-development orientation

A firm with co-development orientation sees its network of relationships primarily as a way ofjointly building capabilities and pursuing innovation together with its partners. The firm engages injoint projects and joint problem solving (Uzzi, 1996) with the network partners. Building a high levelof trust and making rather long term commitments with partners are critical in the co-developmentorientation. As illustrated in Table 1, firms with co-development orientation are likely to havenetworks with fewer but cohesive partners, and such a network will have more dense interactions andhigh mutual trust among the partners. Similarly, the firm would seek out and retain partners thatpossess more tacit knowledge resources. Inter-personal and inter-organizational trust that exists instrong ties enhances search effectiveness through the integration of search routines of both partners(Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000; Lorenzoni and Lipparini, 1999). Search routines are often quite complex(Mone et al., 1998) and when multiple partners are involved, the routines become even more complex.A good understanding of each other’s routines, aspirations, and concerns developed through therepeated ties will help the firms integrate already complex search routines (Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000).Moreover, richness in exchanges and willingness to search for solutions jointly and to co-commitvaluable resources would enable integration of their search routines and enhance the effectiveness oftheir joint search processes (Lorenzoni and Lipparini, 1999). Due to similarity of routines, high level oftrust, and possession of unique resources, firms are likely to co-commit resources for risky projectswith potentially high gains, blend unique resources together to create innovation capabilities, andutilize such capabilities in their joint pursuit of major innovation efforts. The focal firm would getpartners not only with rich resource endowments (Ahuja, 2000b) but also with high motivation tocombine their resources with those of the focal firm and high commitment for undertaking major andrisky projects. The firm could pull together key strengths of all the partners in orchestrating theinnovation process (Dhanaraj and Parkhe, 2006). All these factors suggest that a firm with co-development orientation is likely to engage in and generate more breakthrough innovations. Bybringing multiple partners together and recombining complementary resources in the partnership,the focal firm is likely to succeed in initiating and pursuing breakthrough innovation projects.

Proposition 6. A firm with a co-development orientation of its network is likely to be more effective ingenerating breakthrough innovations than would a firm with an acquisition orientation of its network.

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–2014

Network vitality

Network vitality indicates the extent to which the network is imbued with new resources,especially knowledge resources, over time. A firm’s network vitality can increase through the increasein partner-vitality (new members) (Rosenkopf and Padula, 2008) and/or increase in resource vitality(e.g. resource enrichment of existing network members) of the partners. Firms could increase partner-vitality by forming partnerships with new members and dissolving some of the old partnerships (Kokaet al., 2006). They could increase resource vitality by enhancing the resource base of the existingpartners. Firms become ‘‘rusted’’ when their ability to develop new resources and capabilitiesconsiderably declines over time (Srivastava, 2007). A good indicator of ‘‘rusted’’ firms could bedeclining innovation output of firms over time. Resource vitality increases when the existing membersin the network are dynamic and vibrant and continually enrich their resource bases. Firms with vitalnetwork would bring in new resources from outside and develop more inside. Over time, a focal firm’snetwork loses vitality when it is connected with the same set of firms over a long period of time andthose firms are also losing steam and becoming ‘‘rusted’’. Deactivating ties with such ‘‘rusted’’ firmscould free valuable firm resources which could be more productively utilized in establishing new tieswith more innovative and dynamic firms.

We argue that network vitality has differential moderating impact depending on whether a firmhas acquisition orientation or co-development orientation of its network. In order to illuminatecontrasting moderating impacts of network vitality we consider two situations: when the partnervitality is relatively low but resource vitality is high, and when both partner vitality as well as resourcevitality is high. In the first case, the focal firm is connected with the same set of partners for a longperiod of time and those partners are very actively engaged in enriching their resource bases. Weargue that network vitality in this case positively moderates the effects of co-development networkorientation but negatively moderates the effects of acquisition orientation. Long term relationshipswith the network partners allow the co-development oriented focal firm to develop mutual trust andresource sharing interorganizational routines, which create an environment conducive forcommitting highly valuable resources and engaging into co-creation innovation activities. Generatingground breaking innovations often requires sustained long term commitment of resources. Over time,the network members get more connected with one another, which contributes to the development ofstructural trust (Srivastava, 2007) that in turn creates more cohesive structure for resource sharingand exchange opportunities (Coleman, 1988; Madhavan et al., 2004). On the one hand while effectiverelational mechanisms get well developed, on the other, the network member firms are also highlydynamic and continually engaged in enhancing and enriching their resource bases, which enhancestheir ability to contribute valuable resources toward the co-creation innovation activities. Thus, weexpect that well-developed relational mechanisms and enhanced ability to contribute highly valuableresources together contribute to increased effectiveness of co-development orientation in generatingmore ground breaking innovations.

In contrast, acquisition oriented firms thrive on flexibility and structural advantages which arisemore from the absence of certain types of relationships (Burt, 1992) than from the presence ofrelationships. Being connected with the same set of partners for a long time contributes to thedevelopment of a web of obligations, commitments and expectations of relationships that essentiallyreduce the freedom and flexibility of the focal firm (Gargiulo and Benassi, 2000). Further, maintainingmultiple structural holes by the focal firm in its network also becomes increasingly difficult asunconnected partners in the network find more opportunities and have great motivation to getconnected in order to counter the appropriation power of the focal firm (Madhavan et al., 2004). Thus,low partner vitality creates adverse situations for the acquisition oriented firm and cripples the firm’sability to leverage network resources.

In the second case, i.e., when both partner vitality and resource vitality are high, we argue thatnetwork vitality will have a negative moderating impact on the effectiveness of co-developmentorientation, but will have a positive impact on the effectiveness of acquisition orientation inenhancing the likelihood of generating breakthrough innovations. As we noted before, co-development orientation thrives on trust, social cohesiveness, and development of interorganizationalresource sharing routines, but a high level of churning of network members goes against the

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–20 15

development of these. Development of social cohesion and structural trust could be adverselyaffected. Thus, even though the resource vitality will have a positive effect as there are new resourcesto tap into, the unstable network mars the focal firm’s ability to fully leverage the benefits of resourcevitality. On the other hand, this situation is almost tailor-made for acquisition oriented network firm.The firm’s network has a high degree of churning that provides the focal firm the much neededflexibility and freedom to play the role of ‘tertius inugens’ (Obstfeld, 2005). While the structuralconditions are more favorable for the acquisition oriented firm, the high resource vitality of networkmembers also allows the focal firm to tap into new and rich resources of those members. Thus, thefocal firm is able to access new and rich resources with greater frequency and greater ease allowing itto combine those with its internal resources; consequently the firm enhances its ability to generatemore high impact innovations.

Proposition 7a. When partner vitality is low and resource vitality is high, network vitality positivelymoderates the effect of co-development orientation and negatively moderates the effect of acquisitionorientation on the likelihood of innovations as stated in Propositions 5 and 6.

Proposition 7b. When both partner vitality and resource vitality are high, network vitality negativelymoderates the effect of co-development orientation and positively moderates the effectiveness ofacquisition orientation on the likelihood of innovations as stated in Propositions 5 and 6.

Discussion and implications

As ‘‘the boundary between a firm and its surrounding environment is more porous’’ (Chesbrough,2003, p. 37), firms are reaching out in order to enhance their ability to generate innovations (Powellet al., 1996). Companies tap ‘‘networks of inventors, scientists, and suppliers’’ and even competitors intheir innovation efforts (McGregor, 2006, p. 66). To advance our understanding of the role of externalfactors on firm technological innovation, we developed a conceptual model explaining how twoimportant external factors—network and cluster—influence the likelihood of technological innova-tions. We also identified conditions in which a firm could generate breakthrough innovations byutilizing cluster and network benefits. The innovation barriers and catalysts we identified provide amore concrete basis to examine the underlying issues that firms need to address in their innovationefforts and channel their cluster and network resources accordingly.

Contributions

We highlight three most noteworthy contributions to the literature. First, our identification ofinnovation barriers and catalysts and explicit theoretical connection with the network and clusterconditions provide us with a more nuanced understanding of how a firm’s cluster and network playcritical and often complementary roles in enhancing the likelihood of innovation. Our conceptualframework offers a deeper understanding of possibilities with clusters and networks and at the sametime explicates their limitations. We further note that while for their primary benefits clusters andnetworks play complementary roles (Zaheer and George, 2004), they could also play partiallysubstituting roles (Whittington et al., 2009) when we compare the primary benefits of one with thesecondary benefits of the other. For example, interorganizational networks could also be used forinformation gathering purpose for their secondary benefits. However, if a firm deploys its networkmainly for informational purpose, a primary benefit of a cluster, such a use of a network for suchsecondary benefits will be an inefficient and rather inappropriate utilization of the firm’s resourcesgiven the costs of creating and managing a network. Additionally, as for the sake of isolating the clusterand network mechanisms and for parsimony of conceptual model, we assumed the absence of formalinterorganizational ties for a focal firm within its cluster; now if we release that constraint, we can seehow the increase in overlap between the firm’s network and cluster leads to increased benefits fromboth initially. A cluster increases awareness of the environment and of opportunities, enhancesmotivation to engage in innovation, and provides informal knowledge inflows, and the formalizednetwork ties help the firm mobilize organizational resources from within the cluster. However, as

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–2016

network vitality and cluster vitality tend to dissipate over time, high overlap between a firm’s cluster andnetwork would magnify the adverse effects of dissipating vitality. Further, the relatively inherentflexibility available in rejuvenating a firm’s network by replacing rusted ties would be lost when most ofthose ‘‘friends’’ happen to be their ‘‘neighbors’’ as well (Srivastava, 2007). Also, when the firm’s networkpartners are highly interconnected and are located in the firm’s geographical neighborhood, the focalfirm may face greater risk of knowledge leakage. In this situation, the focal firm would not only lose itsexplicit and tacit knowledge but would also face the risk of its partners being in better positions to takeadvantage of the knowledge leakage. We believe this nuanced understanding of primary and secondarybenefits of networks and clusters would help us address some of the apparent contradictions in theliterature regarding their effects (Whittington et al., 2009; Zaheer and George, 2004).

Second, the concepts of network and cluster vitality that we advanced here provide a usefulconceptual lens to examine the network and cluster dynamism (Rosenkopf and Padula, 2008). Anunderstanding of vitality would also be helpful in configuring a firm’s network (Dhanaraj and Parkhe,2006) and in making a decision about cluster membership and degree of reliance on the cluster. Forinstance, given that the level of cluster vitality is exogenous to a firm, when cluster vitality startsdeclining, a firm primarily relying on its cluster for external resources might face a difficult choice:continued presence in the cluster may be detrimental to its goals, while re-location to another clustermight be prohibitively expensive. However, a firm that relies on both cluster and network for externalresources might benefit more by using a switching strategy: rely more on the cluster when clustervitality is high, and shifts toward the network when cluster vitality is low. Similarly, firms that rely to agreater extent on the network also need to actively manage the level of their network vitality.Additionally, they need to configure their network by explicitly taking into account the risks ofknowledge leakage. The role of competition mechanism within the cluster suggests that when thecluster firms compete both in the input factor market and output factor market, the formal ties withdirect co-located competitors will be less effective. So, within a cluster formal network ties withdownstream network partners and upstream network partners where the partners may compete inthe input factor market or the output factor market, not in both, will be more effective.

Third, our conceptualization of acquisition and co-development orientation provides a uniqueapproach to understanding networks and their effects on firms. We have argued that a firm is likely togenerate breakthrough innovations when it pursues its network for resource co-development becausecombining expertise with partners allows resource recombinations (Fleming, 2001) and pursuit of riskyprojects to generate breakthrough innovation. A firm with an acquisition orientation of its network is lesslikely to be viewed by others as a genuine collaborator and therefore may not be trusted forcommitments of highly valuable resources. However, resource acquisition orientation could be helpfulin protecting a firm’s core knowledge assets. When both partners in a relationship have an acquisitionorientation, they may be able to benefit from what each other has, but the co-opetitive tension (Gnyawaliet al., 2006) is also likely to be high between the partners. Our discussion of network orientation also hasimportant implications for partner selection: partners’ network orientations have to match in order forthe relationship to be effective. If one has an acquisition orientation but the other has a co-developmentorientation, then the relationship is unlikely to be stable, and trust and mutual commitment to eachother will be low. Similarly, in clusters, when competitive intensity and social interaction intensity bothare high, a firm rich in knowledge based resources may find itself at a competitive risk. The focal firm’shigh stock of technological knowledge makes it an attractive target for other co-located competitors.Therefore, high competition intensity and the firm’s knowledge base increase the co-locatedcompetitors’ motivation to acquire the knowledge from the focal firm, and high social interactionintensity may provide them with the means to do so.

Directions for future research

In addition to the research implications stemming from our conceptual model and thecontributions discussed above, we wish to highlight a few more promising directions for futureresearch. In proposing our conceptual model we focused specifically on cluster and network factorsand assumed firm-level factors as constant. Future research could examine the extent to which clusterand network effects vary depending on firm characteristics, including firms’ internal resources and

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–20 17

capabilities. Illustrative questions include: what kinds of firms benefit more from cluster resourcesand versus from network resources? Are cluster and network resources complementary for some typeof firms and substitutes for other types? Further, it is possible that firms pursuing the acquisitionorientation but rich in internal resources and capabilities can still leverage their network resourcesand integrate those with their internal resources and be able to enhance their likelihood ofbreakthrough innovations. Or firms that are internally resource-rich but pursuing a co-developmentorientation might be able to disproportionately benefit from their network resources in generatingbreakthrough innovations.

This paper also provides a strong foundation for empirical research in several ways. While it wouldbe difficult to empirically tackle the entire conceptual model in one study, a good starting point wouldbe to examine whether and to what extent cluster and network conditions do indeed help address thebarriers and catalysts identified in this paper. Building on our discussion of barriers and catalysts,future research could more systematically develop specific enablers and barriers especially in pursuitof breakthrough innovations. Such an investigation would then set the stage to empirically examinewhether and to what extent the cluster and network conditions complement each other in addressingthe barriers and catalysts for various kinds of innovations. Another intriguing research path would beto develop indicators of the acquisition orientation and the co-development orientation andempirically examine their effects. We have pointed out in Table 1 illustrative indicators of theseorientations along several dimensions, which future researchers could further specify and fine-tunealong the technological, relational and structural dimensions of network orientation. For example,based on the logic of technological complementarity being critical for co-development, researcherscould use the technological distance between the focal firm and its direct partners for thetechnological dimension. Low distance may indicate the presence of an acquisition orientation whilehigh distance (more complementarity) may indicate a co-development orientation. In the relationaldimension, the presence of more contractual, bilateral and single-shot alliances may indicate anacquisition orientation, whereas the presence of more equity based, multilateral, repeated alliances,and alliances with new partners may indicate a co-development orientation.

Managerial implications and conclusion

Our model helps managers to develop a better understanding of how networks and clusterscontribute in unique ways to overcome key innovation barriers and act as catalysts of innovation. Wealso suggest that a firm’s network is a resource which needs to be nurtured and managed like any othercritical resource at the disposal of a firm. Managers need to make sure that the network evolves andmaintains vitality over time so that the network does not become a liability. As prior research(Dhanaraj and Parkhe, 2006) suggests, firms need to effectively orchestrate their network to enhanceinnovation. Our paper clearly suggests that the design and management of the firm’s network must bea key strategic consideration of managers to ensure that the network continues to provide innovationopportunities and resources and reduces underlying innovation barriers. In terms of a cluster-basedstrategy, managers need to look for clusters with high competitive intensity and vitality in makingtheir cluster entry decision and take advantage of social interaction in order to benefit from theirpresence in the cluster. It is important, however, to avoid being overembedded in the cluster. Finally, afocus on cluster alone may deprive the firm from unique and rare resources and specific mechanismsfor resource flows, whereas a focus on network alone may make the firm miss critical information ontechnological trends and major innovation opportunities.

In conclusion, with the intent to develop a nuanced understanding of the role of cluster andnetwork conditions on firm innovation, this paper started off with the identification of critical barriersand catalysts for innovation and then explicated how the barriers and catalysts could be impacted byvarious cluster and network mechanisms. Our conceptualization of the underlying competitive andcollaborative aspects of cluster and network and explication of how these aspects manifest differentlyin a cluster and in a network have provided a deeper understanding of the differential roles of clustersand networks on innovation. Future research could build on our conceptual foundation to empiricallyexamine how a firm’s cluster and network uniquely serve as complementary forces in reducing thebarriers and in enhancing the catalysts and impact the firm’s likelihood of generating innovations.

D.R. Gnyawali, M.K. Srivastava / Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 30 (2013) 1–2018

References

Abernathy, W.J., Utterback, J.M., 1978. Patterns of industrial innovation. Technology Review 80 (7), 41–47.Ahuja, G., 2000a. Collaboration networks, structural holes, and innovation: a longitudinal study. Administrative Science

Quarterly 45 (3), 425–455.Ahuja, G., 2000b. The duality of collaboration: inducements and opportunities in the formation of interfirm linkages. Strategic

Management Journal 21 (3), 317–343.Ahuja, G., Lampert, C.M., 2001. Entrepreneurship in the large corporation: a longitudinal study of how established firms create

breakthrough inventions. Strategic Management Journal 22 (6–7), 521–543.Almeida, P., Kogut, B., 1999. Localization of knowledge and the mobility of engineers in regional networks. Management Science

45 (7), 905–917.Arikan, A.T., 2009. Interfirm knowledge exchanges and the knowledge creation capability of clusters interfirm knowledge

exchanges and the knowledge creation capability of clusters. Academy of Management Review 34 (4), 658–676.Arrow, K.J., 1962. Economic Welfare and Allocation of Resources for Invention. Princeton University Press, Princeton.Baum, J.A.C., Calabrese, T., Silverman, B.S., 2000. Don’t go it alone: alliance network composition and startups’ performance in