Compilation thus far · 2017-09-19 · 28 protocol procedures. The purpose of this case report was...

Transcript of Compilation thus far · 2017-09-19 · 28 protocol procedures. The purpose of this case report was...

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Protocol-Based Patient Management for Return to High Intensity Exercise 11

Following Medial Meniscus Allograft Transplantation: A Case Report 12

13

Kate Sullivan, SPT, Sara Deprey, PT, DPT, MS, GCS, Matthew Walker, PT, MPT 14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

ABSTRACT 24

Background/Purpose: Meniscal allograft transplantation is a relatively new procedure 25

aimed at restoring normal knee mechanics following meniscectomy. Little had been 26

reported regarding rehabilitation patient management, complications, and optimal 27

protocol procedures. The purpose of this case report was to describe the protocol-based 28

patient management for a return to high intensity exercise following medial meniscus 29

allograft transplantation in a patient with a complication of tibial stress fracture. 30

Case Description: The patient was a fit 36 year old male with a 10 year history of knee 31

pain following medial meniscectomy. He was referred to physical therapy for protocol- 32

based rehabilitation after receiving a meniscus allograft transplantation. 33

Outcomes: After 17 weeks of therapy, normal ROM and strength had been restored. The 34

patient’s Lysholm Knee Scale and Subjective Knee Questionnaire scores were 96 and 35

88%, respectively. He was able to return to high intensity exercise with minimal pain and 36

judged his knee function as being 90% of ideal. 37

Discussion: Outcomes following meniscus allograft transplantation are generally 38

promising and despite an increase in surgical literature, an optimal protocol for 39

rehabilitation has yet to be established. Variations between protocols may impact length 40

of recovery as well as final outcomes. The utilization of randomized controlled trials in 41

future research may aid in determining optimal rehabilitation standards. 42

43

44

45

46

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE 47

Meniscal tears are of the most common knee injuries; the incidence of acute meniscus 48

injury has been estimated at 60-70 per 100,000 with approximately 850,000 related 49

surgeries per year.1 While partial and full meniscectomy were once the primary surgical 50

intervention, current practice emphasizes preservation of the meniscus through repair 51

procedures.2,3 This shift in practice models began when Fairbank4 suggested an increased 52

rate of degeneration following meniscectomy compared to intact knees. Current literature 53

continues to support Fairbank’s findings. In cadaveric knees following total medial 54

meniscectomy, Lee et al5 demonstrated an increased in average tibiofemoral contact 55

stress and peak contact stress of over 130%, leading authors to suggest that effort be 56

taken to preserve as much of the meniscus as possible to maintain normal biomechanics. 57

Despite current knowledge, partial and total meniscectomies remain the primary 58

treatment option for irreparable meniscal damage.1,6 Patients whom continue to have pain 59

following meniscectomy have few options.7 Conservative measures, including unloading 60

braces, anti-inflammatories, and physical therapy, may be implemented, though for 61

patients with persistent symptoms, there are 2 primary interventions. Arthroplasty, 62

though well supported in the literature, may not be an option for all populations due to an 63

increase rate of prosthetic wear with higher level activities.1 The alternative, is meniscal 64

allograft transplantation (MAT),8 an increasingly common option, particularly among 65

young and active patients. MAT was first described in the literature by Milachowski and 66

colleagues9 in 1987 and is generally indicated for patients younger than 50 with a 67

previous meniscectomy and pain localized to the meniscectomized compartment.1,9 68

Alhalki et al10 demonstrated that maximum and mean contact pressure were 75% lower 69

with MAT than in meniscectomized knees and medial tibiofemoral contact area was 70

comparable to normal knees. A systematic review of MAT literature found a 60% rate of 71

favorable outcomes, though the rate increased to 85% when only more recent literature 72

was analyzed.11 Kang, et al3 also reported a good to excellent outcomes rate of 85%. 73

Another study found that at follow-up assessments of at least 2 years, only 7 of 39 74

patients had unsuccessful outcomes though 90% (35/39) of patients were classified as 75

normal or nearly normal according to the International Knee Documentation Committee 76

Evaluation and 77% reported satisfaction with the procedure.12 Other than surgical 77

complications comparable to those of meniscal repair (incomplete healing, infection, 78

persistent symptoms, neurovascular injury,3 and arthrofibrosis),3,14 few authors have 79

reported complications. Rath and colleagues6 did report a 36% rate of allograft tears 80

within 66 months of transplantation; whether this was due to faulty biomechanics, patient 81

activity level, poor healing, or characteristics of the allograft was unclear. 82

Despite the growing body of surgical literature, very little has been published regarding 83

rehabilitation protocols. Current suggestions are based on knowledge of tissue healing 84

rates15 and protocols for meniscal repair.16 However, in regard to achieving optimal 85

outcomes, return to sport, and managing complications, there is little literature.2,3 86

Consequently, the purpose of this case report was to describe the protocol-based patient 87

management for a return to high intensity exercise following medial meniscus allograft 88

transplantation in a patient with a complication of tibial stress fracture. 89

90

PATIENT HISTORY AND SYSTEMS REVIEW 91

The patient was a fit 36 year old male first seen for outpatient physical therapy during 92

Week 2 of his recovery following arthroscopic allograft transplantation of the left medial 93

meniscus. He was evaluated and treated in a non-direct access environment. The patient 94

originally injured his left medial meniscus playing baseball approximately 21 years ago. 95

Over the next 5 years the patient underwent 4-5 surgeries that ultimately resulted in a 96

subtotal meniscectomy; he also received multiple steroid injections to manage pain while 97

playing competitive baseball into college. Other than his recent transplantation 98

procedures, the patient’s last knee surgery was 8 years ago. His activity level has since 99

been limited to walking and upper body exercise due to severe medial left knee pain, 100

described as sharp, often shooting distally and proximally. The patient also experienced 101

catching, locking, and swelling. Previously treatment, (anti-inflammatories, an unloading 102

brace, and steroid injections), was less than successful. 103

Radiographic MRI analysis performed approximately 1 year prior to transplantation 104

revealed degenerative changes. Based on a diagnostic arthroscopy performed 4 months 105

prior to the transplantation, only 10% of the patient’s medial meniscus remained; the 106

lateral meniscus was intact and all ligaments were normal. At this time, the attending 107

surgeon documented that the patient met the criteria for meniscus allograft 108

transplantation with an estimated 85% chance of success. The patient agreed to this 109

treatment plan and underwent arthroscopic MAT without complications 4 months later. 110

At the initial evaluation during postoperative Week 2, the patient complained of left knee 111

pain, described as an ache, that ranged from 3/10 to 6/10 on the Numeric Rating Scale 112

(NRS) of 0-10 (0 being described as an absence of pain and10 as the worst pain 113

imaginable). NRS ratings have been shown to be highly correlated with ratings on the 114

Visual Analogue Scale.17 His pain generally increased with use and decreased with rest, 115

ice, and pain medication. He also complained of swelling, decreased motion, left knee 116

weakness, and numbness of the infrapatellar region. 117

The patient reported that he lives with his wife and 2 children from whom he could 118

receive assistance as needed; he was able to ambulate at home, including stairs, with 119

crutches. His job requirements did not include physical labor though he was occasionally 120

required to travel, which included sitting for flights of 12 hours or more and ambulating 121

across airports. Other than high blood pressure the patient was in good health. He did not 122

have a history of right knee injury or other orthopaedic conditions. Patient goals for 123

therapy were to decrease pain and increase strength and range of motion. Ultimately, his 124

goal was to return to high level exercise without significant knee pain. He also hoped to 125

more actively participate in coaching youth sports, including demonstration of drills and 126

jogging/running on uneven terrain. The patient appeared highly motivated to reach these 127

goals and expressed a good understanding of therapy, exercise, and physical training. 128

129

Clinical Impression I 130

Though the patient’s complaints of pain, decreased range and strength, and functional 131

limitations were typical for physical therapy settings, the surgical procedures leading to 132

his referral were quite uncommon. Similarly, complications and precautions, expected 133

rate of progress, and typical rehabilitation strategies following MAT were unknown to 134

the therapist. The extent to which degenerative changes associated with the previous 135

meniscectomy would impact prognosis and outcomes was unknown. A review of the 136

post-operative protocol 18 (Figure 1) provided by the surgeon and a thorough examination 137

were planned in order to establish the patient’s current status. 138

139

EXAMINATION 140

The patient ambulated with 2 axillary crutches and 50% weight bearing (WB) through the 141

left lower extremity; he wore a hinged knee brace locked in 0-90o of flexion for all WB. 142

The left knee was visibly edematous and warm to touch in respect to the unaffected knee. 143

Incisions were tender though dry and healing appropriately. 144

Range of motion (ROM) was measured19 with a universal goniometer. Right lower 145

extremity, left hip, and left ankle ROM were within normal limits; left knee ROM was 146

limited (Table 1). Knee passive ROM has been shown to have high inter- and intra-rater 147

reliability for both flexion and extension.20 High concurrent validity in relation to 148

radiographic assessment has also been demonstrated.20,21 Manual muscle testing (MMT)22 149

was used to assess strength of the right lower extremity and left hip and ankle. Strength 150

testing of the left quadriceps and hamstrings was performed in the available range (Table 151

1). MMT has been shown to be both a reliable and valid assessment of strength.23,24 The 152

patient reported decreased sensation inferior to the incisions which was attributed to the 153

surgical procedures. In Week 3, patellar mobility was normal in relation to the unaffected 154

side. In Week 5, the patient experienced an increase in pain after his knee “gave out” 155

while ambulating on uneven terrain. Increased edema was evident and he complained of 156

medial tenderness to palpation. Knee ligamentous stability, assessed with the valgus 157

stress test,25 provoked pain near the distal attachment of the medial collateral ligament 158

though joint laxity was comparable to the unaffected side. In Week 29, balance was 159

assessed with a single leg stance (SLS) test with shoes on in Week 29. The patient 160

maintained SLS with eyes open for 30 seconds bilaterally; SLS with eyes closed was 161

limited to 17 seconds on the right and 12 on the left. The Subjective knee Questionnaire 162

(Appendix 2)26 and Lysholm Knee Scale (Appendix 1)27 were completed in Weeks 25, 163

29, and 33. The Subjective Knee Questionnaire form was developed30 and modified26 for 164

knee assessment following ACL repair. This questionnaire was chosen to monitor patient 165

progress due to its assessment of higher level activities. The Lysholm Knee Scale has 166

been shown to have high construct validity and acceptable test-retest reliability and 167

internal consistency for assessing meniscal injuries.28 168

169

Clinical Impression II 170

The patient’s presentation was typical for a post-surgical status; current function 171

conformed to the surgeon’s protocol in regard to weight bearing and brace use. Based on 172

the exam findings and an unremarkable systems review, the patient was deemed 173

appropriate for therapy. Nevertheless, with an unfamiliar surgical procedure, a cautious 174

approach to treatment would be taken. Modality use was planned in addition to the 175

progression of interventions stated in the protocol. Incorporation of sports related 176

activities was planned to address the patient’s goals of returning to high intensity exercise 177

and coaching activities. Assessments would be in accordance with the protocol 178

timeframes and projected rate of progression. Likewise, the precautions/contraindications 179

stated in the protocol would be closely adhered to. 180

181

INTERVENTION 182

Treatment began at the initial evaluation and was based predominantly on the 3-phase 183

post-operative protocol developed and provided by the surgeon. The phases of the 184

protocol were based on time since surgery, though due to individual factors, advancement 185

though the protocol was adjusted according to the patient’s symptoms and tolerance. 186

Throughout rehabilitation, the patient was provided with a progressive home exercise 187

program and instructions for modification of his pre-existing independent exercise. 188

Goals for Phase I (0-8 weeks) included decreasing pain and edema, increasing ROM, 189

improving quadriceps recruitment, and regaining a normal gait pattern without crutches. 190

Electrical stimulation (ES) for pain and inflammation was initiated at the first visit. 191

Interferential current, preset on the clinic’s equipment, was adjusted to patient comfort 192

for 10 minutes following therapeutic exercise until Week 4 when inflammation and pain 193

were minimal. In Week 3, a separate ES treatment for neuromuscular re-education of the 194

vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) was initiated. Preset parameters were used with a 10:10 195

contract-relax ratio for 6 minutes with intensity set for tolerable muscular contraction. 196

The patient was instructed to perform a quad set, with progression to single leg raises, as 197

he felt his VMO contract. Therapeutic exercises and activities are displayed in Table 3. 198

Parameters were generally 2-3 sets of 10 though modified according to tolerance. 199

Resistance was progressed as tolerated so as to induce muscular fatigue. It should be 200

stressed that knee flexion greater than 90o in WB, as well as resisted hamstring exercises, 201

were contraindicated in order to minimize rotational stress on the allograft. Crutch use 202

was discharged in Week 4. During Week 5, the patient experienced an increase in; 203

therapeutic exercises were modified by to tolerance and ES was resumed on a preset 204

premodulated current for pain control for 10 minutes following therapeutic exercise. 205

Though the protocol called for discharge of the brace after Week 6, the patient was 206

instructed to continue wearing it as needed for pain control and community ambulation. 207

Pain continued into Week 8 when the patient made an appointment with the surgeon for 208

Week 11. 209

The goals for Phase II (8-12 weeks) were to achieve full active ROM, continue to 210

increase quadriceps strength, begin addressing proprioception and hamstring strength, 211

and continue to normalize gait as well as stair ambulation. The patient was absent from 212

therapy during Weeks 9-10 for travel. Upon return, the patient saw his surgeon; the 213

increased pain was attributed to a stress fracture where a surgical screw fixed the allograft 214

to the tibia. Despite this, the patient was cleared for therapy with a prescription for 215

progression as tolerated while avoiding moderate to high impact activities. Both ES 216

treatments were discontinued as VMO recruitment normalized and pain and inflammation 217

improved. Therapeutic exercises and activities were modified to better address 218

proprioception by adding unstable surfaces and distraction activities such as ball 219

throwing and catching. Normalization of gait and stair ambulation was also addressed. 220

Goals for Phase III (12-16 weeks) included achieving full and pain free active ROM and 221

progressing to functional and sport-specific activities. By Week 12, the patient had yet to 222

regularly demonstrate a normal gait pattern or regain full ROM, primarily do to pain; 223

progression to Phase III was delayed with a more gradual transition from the Phase II. 224

Ultrasound (3.3Hz, .4W/cm2 at 100% duty cycle) and premodulated ES were initiated to 225

address continued superior medial tibia pain and MCL tenderness per the surgeon’s 226

order. Eventual progression to high impact and ballistic activities was based on elicitation 227

of pain. Activities that increased pain were modified by decreasing range of motion, 228

resistance, and/or repetition; if pain persisted, the exercise was deferred. The patient was 229

again absent from therapy during Weeks 17 and 18. By Week 26 he was able to tolerate 230

mild to moderate ballistic and plyometric activities, which he also began successfully 231

incorporating into his independent exercise. During Weeks 29 and 30 the patient was 232

absent from therapy due to travel. Upon return he presented with increased pain and 233

edema after sitting. This was addressed with ultrasound and ES as previously described; 234

by Week 32 the edema had resolved and pain was present with only a select few 235

exercises. In Week 33 the patient was reassessed; it was determined that he was safe for 236

discharge and well prepared to continue progressing independently. 237

238

OUTCOMES 239

Normal extension active ROM25 and a strong vastus medialis obliquus contraction were 240

achieved by Week 9; normal flexion25 was regained by Week 14. Hamstring strength 241

reached 5/5 by Week 29; quadriceps femoris and hip flexion strength reached 5/5 by 242

Week 33 (Table 1). In Week 29, the patient could maintain single leg stance with eyes 243

open for 30 seconds bilaterally; with eyes closed he was limited to an average of 17 244

seconds on the right and 12 seconds on the left. At the time of discharge, the patient still 245

had mild and transient pain in the superior-medial tibia with high impact and ballistic 246

activities; increases in pain generally did not last more than 24 hours. All daily activities 247

and moderate exercise were performed pain free with the exception of stair ambulation 248

which evoked slight pain. Ligamentous stability was intact and previous medial knee pain 249

with valgus stress had resolved. Though not quantified, the patient reported improvement 250

in sensation in the infra-patellar region. Both the Lysholm Knee Scale and Subjective 251

Knee Questionnaire scored reflected near-normal function (Table 2). Prior to MAT, the 252

patient was unable to tolerate any lower extremity activity more strenuous than walking; 253

by discharge he was able to perform high impact, ballistic, and sports activities with only 254

minimal and transient pain. He also reported independent participation in a sport-based 255

exercise class and active participation in coaching youth sports. At Week 33, he rated his 256

knee as being at 90% of his ideal function. 257

258

DISCUSSION 259

Due to the encouraging outcomes,3,6,12 MAT is becoming increasingly common.31 To 260

provide optimal care, physical therapists must be familiar with the indications, outcomes, 261

complications, and, above all, rehabilitation protocol. Similarly, it is the responsibility of 262

therapists to participate in the critical examination of the effectiveness and practicality of 263

various protocols. This case report describes the protocol-based patient management, 264

complicated by a tibial stress fracture, of a previously active 36 year old male wishing to 265

return to high intensity exercise following MAT. Over the course of 31 weeks, 53 266

treatment sessions were completed. All treatment was based on the surgeon’s protocol, 267

though modifications were needed. During Week 5 the patient experienced an acute 268

increase in pain in the superior-medial tibia that was attributed to a stress fracture where a 269

surgical screw fixed the allograft. Progression was slowed and the patient was restricted 270

from ballistic activities until Week 26. The patient was discharged from therapy during 271

Week 33, 17 weeks longer than predicted by the protocol. 272

The patient had excellent outcomes nonetheless. By discharge, he had full and pain-free 273

active ROM. Hamstrings, quadriceps, and hip strength were comparable to the unaffected 274

side and gait was normal. Post-surgical pain was nearly eliminated, only occurring with 275

occasional stair ambulation and high impact activities. The Lysholm Knee Scale and 276

Subjective Knee Questionnaire results consistently improved over the last 8 weeks to 277

reach 96% and 88%, respectively. The patient also met his goals of returning to high 278

intensity exercise and active participation in coaching youth sports as tolerated. These 279

functional outcomes were comparable to those described by other short term studies and 280

case reports. Fritz et al15 and Baltaci et al8 reported Lysholm scores of 82 and 67 at 281

discharge, respectively. Baltaci8 reported active ROM of117o at discharge and 130o at the 282

1 year follow up. Cole and associates12 reported a Lysholm score of 71.6+19.7, as well 283

as significant improvements in pain. Heckmann at al16 reported 77% of patients returned 284

to participation in low impact sports and only 6% of patients had pain with daily 285

activities, compared to 77% pre-operatively. 286

Regardless of the patient’s outcomes, and though the reviewed literature revealed no 287

report of any fractures occurring in conjunction with MAT surgical procedures or 288

rehabilitation interventions, one must question whether the Phase I progression had any 289

influence on the development of the stress fracture, which substantially delayed progress 290

and necessitated additional therapy visits. Few protocols have been cited in the literature, 291

some more conservative than others. Though the examined protocols emphasized 292

allograft protection by avoiding tibial rotation through ROM limitations in weight 293

bearing and non-weight bearing, as well as delaying resisted hamstring strengthening 294

until at least Week 8,8,15,18 there was variability in the duration of these limitations. Time 295

to return to sport was also variable. 296

The protocol used in this case allowed for immediate 50% WB with crutches and the 297

brace locked in extension. By Week 2, the brace was unlocked for 0-90o ROM in WB; 298

non-weight bearing ROM was full. Crutches were discharged in Week 4 and the brace in 299

Week 6. Other protocols allow for immediate WB as tolerated though the brace is kept in 300

extension for 6 weeks, with brace discharge at 8 weeks.8,15 Baltaci and colleagues8 further 301

limit all ROM to 0-105o until 3 months post-op. Because there have not been reports of 302

complications following immediate full WB, the patient’s stress fracture was attributed 303

primarily to the increase in mobility after unlocking the brace. A brace locked in 304

extension not only limits motion, it serves as a physical and psychological reminder of 305

the recent surgical procedure and resulting fragility of the joint. A patient who had more 306

pain and limitation preoperatively may be apt to a premature and drastic increase in 307

activity due to the improvements in pain and function. Prevention of this complication 308

may have been best accomplished through thorough patient education regarding gradual 309

return to activity and the expected healing process, particularly for patients who 310

experience less pain in the early post-operative weeks than they did preoperatively. This 311

is something a protocol is unable to provide and must be developed based on the 312

experience and skill of the therapist in conjunction with the patient’s values. 313

Full ROM in WB was initiated at 8 weeks with closed chain resistance limited to 0-90o. 314

Baltaci and colleagues8 further limit closed chain flexion to 60o. At approximately 8-9 315

weeks, all protocols initiate stationary bike or stair master use.8,15,18 By Phase III, it was 316

expected that the patient have a normal gait pattern and full range of motion. The 317

protocol allowed for progression as tolerated for return sport and high level functional 318

activities. Due to the possible fracture, this particular patient did not begin 319

jogging/running before 7 months. Kang, et al3 predicted a return to running at 4-6 months 320

and return to full activities by 9 months so long as strength is at least 80-85% of normal. 321

Other protocols initiate running at 9 months8 with return to sport at 1 year post-op.8,15 322

While there have been many publications reporting the outcomes of MAT comparing pre-323

surgical to post-rehabilitation measures, little has been reported specifically on 324

rehabilitation outcomes. This makes it difficult to separate the changes that occur 325

following surgery from those following rehabilitation, leading to difficulty in deciphering 326

the implications of variability within differing protocols. For example: What components 327

of improved functional activity are related to post-op rehabilitation versus the restoration 328

of normal biomechanics through MAT? In order to accurately assess the impact of 329

various protocol components, as opposed to surgical outcomes, additional research is 330

necessary. Randomized clinical trials are suggested for assessing variables such as time 331

to full WB; WB ROM and brace use; discharge of the crutches and brace; and 332

incorporation of resistance training and closed kinetic chain activities. 333

334

Acknowledgements 335

Matthew Walker, PT, MPT was the primary treating physical therapist and oversaw all 336

patient management. 337

Sara Deprey, PT, DPT, MS, GCS, served as advisor to the author, providing guidance 338

and editing 339

340

341

342

REFERENCES 343

1. Brockmeier SF and Rodeo SA. Chapter 23 Knee. In: DeLee JC, Drez D, Miller 344

MD. DeLee: Delee and Drez’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine, 3rd Ed. Saunders; 345

2009. Accessed April 2, 2010 via MD Consult online. 346

http://www.mdconsult.com.pioproxy.carrollu.edu/php/192690172-3/homepage 347

2. Boyd KT, Myers PT. Meniscus preservation; rationale, repair techniques and 348

results. Article Review based on COKS meeting presentation in Cape Town in 349

March 2002. The Knee. 2003;10(1-11). 350

3. Kang RW, Latterman, Cole BJ. Allograft meniscus transplantation: background, 351

indications, techniques, and outcomes. J Knee Surg. 2006;19(3):220-230. 352

4. Fairbank TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 353

1948;30B(4):664-670. 354

5. Lee SJ, Aadalen KJ, Malaviya P, Lorenz EP, Hayden JK, Farr J, Kang RJ, Cole 355

BJ. Tibiofemoral contact after mechanics after serial meniscectomies in the 356

human cadaveric knee. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(8):1334-1344. 357

6. Rath E, Richmond JC, Yassir W, Albright JD, Gundogan F. Meniscal allograft 358

transplantation: two- to eight-year results. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:(4):410-414. 359

7. Heckmann TP, Barber-Westin SD, Noyes FR. Meniscal repair and 360

transplantation: indications, techniques, rehabilitation, and clinical outcome. J 361

Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(10):795-814. 362

8. Baltaci G, Ergun N, Bayrakci V. Rehabilitation and knee function after allograft 363

meniscal transplantation. Phys Ther Case Reports. 1999;2(3):91-98. 364

9. Milachowski KA, Weismeier K, Wirth CJ, Kohn D. Meniscus transplantation: 365

experimental study and first clinical report. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:626. 366

10. Alhalki MM, Hull ML, Howell SM. Contact mechanics of the medial tibial 367

plateau after implantation of a medial meniscus allograft: a human cadaveric 368

study. Am J Sports Med 2000;28(3):370-376. 369

11. Matava MJ. Meniscal allograft transplantation: a systematic review. Clin Orthop 370

Relat Res. 2007;455:142-157 371

12. Cole BJ, Dennis MG, Lee, SJ, Nho SJ, Kalsi RS, Hayden JK, Verma NN. 372

Prospective evaluation of allograft meniscus transplantation: a minimum 2-year 373

follow-up. Am J Sports Med, AJSM Pre-View. 2006;X(X):1-9. 374

13. Garrett JC. Meniscal transplantation: a review of 43 cases with 2- to 7-year 375

follow-up. Sports Med Arthrosc. 1993;1(2):164-167. 376

14. Felix NA, Paulos LE. Current status of meniscal transplantation. Knee. 377

2003;10:13-17 378

15. Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD. Rehabilitation following allograft meniscal 379

transplantation: a review of the literature and case study. J Orthop Sports Phys 380

Ther. 1996;24(2):98-106. 381

16. Heckmann TP, Barber-Westin SD, Noyes FR. Meniscal repair and 382

transplantation: indications, techniques, rehabilitation, and clinical outcome. J 383

Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(10):795-814. 384

17. Cork RC, Isaac I, Elsharydah A, Saleemi S, Zavisca F, Alexander L. A 385

comparison of the verbal rating scale and visual analogue scale for pain 386

assessment. The Internet Journal of Anesthesiology. 2004;8(1). Accessed 4/4/10 387

via http://www.ispub.com/ 388

18. Cole BJ. Cartilage Doc: The Cartilage Restoration Center at Rush. Rehab 389

Protocols. http://www.cartilagedoc.org/home.cfm. Accessed January 30th, 2010. 390

19. Norkin CC, White DJ. Measurement of Joint Motion: A Guide to Goniometry. 3rd 391

Ed. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company; 2003. 392

20. Watkins MA, Riddle DL, Lamb RL, Personius WJ. Reliability of goniometric 393

measurements and visual estimates of knee range of motion obtained in a clinical 394

setting. Phys Ther. 1991;71:90-97. 395

21. Gogia PP, Brazzta JH, Rose SJ, Norton BJ. Reliability and validity of goniometric 396

measurements at the knee. Phys Ther. 1987;67(2):192-195. 397

22. Reese NB. Muscle and Sensory Testing. 2nd Ed. St. Louise, MO: Saunders 398

Elsevier; 2005. 399

23. Bohannon RW. Manual muscle test scores and dynamometer test scores of knee 400

extension strength. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67(6):390-392. 401

24. 24. Cuthbert SC, Goodheart GJ. On the reliability and validity of manual muscle 402

testing: a literature review. Chiropr Osteopat. 2007;15(4):1-23. Accessed via 403

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1847521/ Access 4/4/10 404

25. Magee DJ. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 5th Ed. St. Louise, MO: Saunders 405

Elsevier; 2008. 406

26. Wilk KE, Romaniello WT, Soscia SM, Arrigo CA, Andrews JA. The relationship 407

between subjective knee scores, isokinetic testing, and functional testing in the 408

ACL-reconstructed knee. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20(2):60-73. 409

27. Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. 410

Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;198:43-49. 411

28. Briggs KK, Kocher MS, Rodkey WG, Streadman JR. Reliability, validity, and 412

responsiveness of the Lysholm Knee Score and Tegner Activity Scale for patients 413

with meniscal injury of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88A(4):698-705 414

29. Kocker MS, Steadman JR, Briggs KK, Sterett WI, Hawkins RJ. Reliability, 415

validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm Knee Scale for various chondral 416

disorders of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86:1139-1145. 417

30. Noyes FR, Barber SD, Mooar LA. A rationale for assessing sports activity levels 418

and limitations in knee disorders. Clin Orthop. 1989;246:238-249. 419

31. Canale & Beatty: Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 11th ed. 2007. Mosby, 420

Elsevier. Accessed via MD Consult. 4/13/2010. 421

422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443

TABLES AND FIGURES 444 445 Table 1. ROM and Strength from initial evaluation (Week 2) to discharge (Week 33). 446

Week 2 Week 11 Week 15 Week 20 Week 29 Week 33 Knee Flexion AROM / PROM 82o/85o 115o/118o 129o/134o WNL* WNL WNL Extension Knee AROM / PROM -4o/-2o WNL WNL WNL WNL WNL Knee Flexion Strength 3-/5** 4-/5† 4/5† 5/5 5/5 5/5 Knee Extension Strength 3+/5** 4-/5† 4/5† 4+/5 5-/5 5/5 Hip Flexion Strength 4/5 4/5 4/5 4+/5 5-/5 5/5 *WNL = Within Normal Limits **Patient reported knee joint pain †Patient reported tibia pain 4+/5 447 448 Table 2. Subjective Assessments of Function 449

25 weeks 29 weeks 33 weeks

Lysholm Knee Scale 81/100 88/100 96*/100

Subjective Knee Questionnaire Total Score 79% 84% 88%

Subjective rating of knee function 70% 70% 90%**

*In Week 33, the portion of the Lysholm Knee Scale in which the patient assessed himself as having less than full function was "Stair Climbing," which he rated as "slight problem."

**The portions of the Subjective Knee Questionnaire in which the patient assessed himself below full function were: Pain ("I have occasional pain with strenuous or heavy work. I don't think that my knee is entirely normal"); Overall Activity ("I can partake in sports including strenuous ones but at a lower level. I must guard my knee and limit the amount of heavy labor or sports"); Stairs ("slight, mild problems"); Running ("slight, mild problems, run at half speed"); and Jumping and Twisting ("slight, mild problems, some guarding")

450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464 465 466 467 468

469 Table 3. Exercise Logs 470

Week 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Exercise Heel Slides x x x x x x x x Quad Sets x x x x x x x x Single Leg Raise x x x x x x x x Short Arc Quad x x x x x x x x Heel Raises x x x x x x x Mini Squat x x x x x x x

Terminal Knee Extension x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Bike x x x x x x x Trampoline

Lunges x x x x x x x Squats x x x x x x x Single Leg Stance x x x Marching x Balance Board

Side to side weight shift x x x x x x x Squat x x x x x Forward/Back Balance x x x x x x x Pulley

Knee Extension x x x x x Knee Flexion x x x x x Hip Flexion x x x x x Step Lateral Step-up x x x x x

Dorsiflexion with Theraband x x x x

Balance Beam (3.6mx10cm) Lunges forward/back x x

Single Leg Stance x x

471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490

491 Week 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Exercise Bike x x x Elliptical Trainer x x x x x x x x x x Trampoline

Squats x x Lunges x x x Marching x x x x x x x x x x x x x Balance Board

Squat x x x x x x x Side to side weight shift x x x x x x x Forward/Back Balance x x x Balance Beam

(3.6mx10cm) Lunges forward/back x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Side Lunge x x x x x x x x x x x x x

SLS on Foam with Body Blade x x x x

Pulley

Knee Extension x x Knee Flexion x x Hip Flexion x x x x x x x x x x Terminal Knee Extension x x x x x x x x Walking Side Squats x x x x x x x x x x x x x Hip ABD x x x x x x Hip ADD (B) x x x x x x x x x x x

Walking Lunge forward/ back x x x x x x x x x x

Walking Lunge back/ forward x x x x x x

Step

Lateral Step-up x x Lateral Over and Back x x x x x x x x x x Forward Step-up x x x x

Dorsiflexion with Theraband x

Single Leg Stance x x x Clams x x x x x x x x 90o and 45o lunges x x x x Compass Lunge x x x x x x x x Clocks x x x x x x x x x x Slide Board x x x x Bosu Ball Squats x x x x Skater Squats x x x x x x x x

Golfer's Lift on Foam x x x x x x x x

Deep Squat x x x x x x x x x Single Leg Wall Squat x x x x x

Wide Squat with 180o o

jump turn x x x x x x Clams: sidelying with hips and knee flexed, externally rotate top leg keeping feet together

Compass Lunge: lunge forward to "north," with right leg, step back, lunge to north-east, east, south-east, etc; lunge backward for "South," repeat backward lunge with left leg, lunge south west, etc.

Clock: SLS squats on flat portion of half foam roll; reaching with cane in right hand across body to "9 o'clock," squat with reach to "10 o'clock" etc around to 3 o'clock and back.

Skater Squats: Left SLS squat with right leg reaching behind left in adduction, mimicking speed skater's turn stride Golfer's lift on foam: SLS on 2" foam pad, forward hip hinge; reaching for and lifting 3-5# weights

Wide squat with 180o jump turn: patient squats as though catching a ground ball, jumps to turn 180o with squat; alternate directions

492 493 494 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528 529 530 531

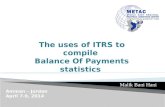

FIGURE 1.18 532 MENISCAL ALLOGRAFT TRANSPLANTATION 533

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 534 535 536

WEIGHT BEARING

BRACE ROM THERAPEUTIC EXERCISE**

PHASE I 0-8 weeks

0-2 weeks: partial weight bearing - (up to 50%) 2-6 weeks: as tolerated with crutches – discontinue use of crutches at 4 weeks when gait normalizes

0-1 week: locked in full extension for sleeping* 0-2 weeks: locked in extension for all weight bearing activities 2-6 weeks: Locked 0-90o-discontinue brace after 6 weeks

0-2 weeks: non-weight bearing 0-90o 2-6 weeks: as tolerated, non-weight bearing

0-2 weeks: heel slides, quad sets, patellar mobs, SLR, SAQ 2-8 weeks: addition of heel slides, total gym (closed chain), and terminal knee extensions- activities with brace until 6 weeks, then without brace to tolerance NOTE: No weight bearing with flexion >90o during phase I

PHASE II 8-12 weeks

Full, without crutches

None Full active range of motion

Progress closed chain activities, begin hamstring work, lunges 0-90o of flexion, proprioception exercises, leg press 0-90o – flexion only, begin stationary bike

PHASE III 12-16 weeks

Full with a normalized gait pattern

None Full and pain free

Progress phase II exercises and functional activities such as: single leg hops, jogging to running progression, plyometrics, slideboard, and sport-specific skills

537 538 *Brace may be removed for sleeping after first post-operative visit (day 7-10) 539 **Avoid any tibial rotation for 8 weeks to protect meniscus 540 541 542 COPYRIGHT 2003 CRC ® BRIAN J. COLE, MD, MBA 543 544 545 546 547

APPENDIX 1.27 548 Lysholm Knee Scale 549

Name___________________________ Date ____________ Therapist _______________ 550 By completing this questionnaire, your therapist will gain information as to how your knee 551 functions during normal activities. Mark the box which best describes your knee function today. 552 553 1. LIMP 554 [ ] None 5 555 [ ] Slight or periodic 3 556 [ ] Severe and constant 0 557 2. SUPPORT 558 [ ] None 5 559 [ ] Cane or crutch needed 2 560 [ ] Weight bearing impossible 0 561 3. LOCKING 562 [ ] None 15 563 [ ] Catching sensation, but no locking 10 564 [ ] Locking occasionally 6 565 [ ] Locking frequently 2 566 [ ] Locked joint at examination 0 567 4. INSTABILITY 568 [ ] Never gives way 25 569 [ ] Rarely during athletic activities/physical exertion 20 570 [ ] Frequently during athletic activities/physical exertion 15 571 [ ] Occasionally during daily activities 10 572 [ ] Often during daily activities 5 573 [ ] Every step 0 574 5. PAIN 575 [ ] None 25 576 [ ] Intermittent and light during strenuous activities 20 577 [ ] Marked during strenuous activities 15 578 [ ] Marked during or after walking more than 2m (1.2mi) 10 579 [ ] Marked during or after walking less than 2m (1.2mi) 5 580 [ ] Constant 0 581 6. SWELLING 582 [ ] None 10 583 [ ] After strenuous activities 6 584 [ ] After ordinary activities 2 585 [ ] Constant 0 586 7. STAIRS 587 [ ] No problems 10 588 [ ] Slight problem 6 589 [ ] One step at a time 2 590 [ ] Impossible 0 591 8. SQUATTING 592 [ ] No problem 5 593 [ ] Slight problem 4 594 [ ] Not beyond 90o of flexion at the knee (halfway) 2 595 [ ] Impossible 0 596 Reprinted with permission. Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating Systems in the Evaluation of Knee Ligament 597 Injuries. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1985;43-49. 598

APPENDIX 2.26 599 SUBJECTIVE KNEE SCORE QUESTIONNAIRE 600

601 PLEASE CHECK THE STATEMENT THAT BEST DESCRIBES THE CONDITION OF 602 YOUR KNEE. 603 604 PAIN 605 20 - I experience no pain in my knee. 606 16 - I have occasional pain with strenuous sports or heavy work. I don't think that my 607

knee is entirely normal. Limitations are mild and tolerable. 608 12 - There is occasional pain in my knee with light recreational sports or moderate work. 609 8- I have pain brought on by sports, light recreational activities, or moderate work. 610

Occasional pain is brought on by daily activities such as standing r kneeling. 611 4- The pain I have in my knee is a significant problem with activities as simple as 612

walking. The pain is relieved by rest. I can't participate in sports. 613 0- I have pain in my knee at all times, even during walking, standing, or light work. 614 615 Intensity: A. [ ] Mild B. [ ] Moderate C. [ ] Severe 616 Frequency: A. [ ] Constant B. [ ] Intermittent 617 Location: A. [ ] Medial B. [ ] Lateral C. [ ] Anterior 618

D. [ 1 Posterior E. [ ] Diffuse 619 Occurs: A. [ ] Kneel B. [ ] Stand C. [ ] Sit D. [ ] Stairs 620 Type: A. [ ] Sharp B. [ ] Aching C. [ ] Throbbing 621 D. [ ] Burning 622 SWELLING 623 10 - I experience no swelling in my knees. 624 8- I have occasional swelling in my knee with strenuous sports or heavy work. 625 6- There is occasional swelling with light recreational activities or moderate work. 626 4- Swelling limits my participation in sports and moderate work. Occurs infrequently with simple 627

walking or light work. Occasionally with simple walking or light work-about three times 628 a year. 629

2- My knee swells after simple walking activities and light work. The swelling is relieved by rest. 630 0 - I have severe swelling with simple walking activities. The swelling is not relieved by rest. 631 STABILITY 632 20 - My knee does not give out. 633 16 - My knee gives out only with strenuous sports or heavy work. 634 12 - My knee gives out occasionally with light recreational activities or moderate work; it 635

limits my vigorous activities, sports, or heavy labor. 636 8- Because my knee gives out, it limits all sports and moderate work. It occasionally 637

gives out with walking or light work. 638 4- My knee gives out frequently with simple activities such as walking. I must guard my 639

knee at all times 640 0- I have severe problems with my knee giving out. I can't turn or twist without my knee 641 giving out. 642

643 Stiffness: A. [ ] None B. [ ] Occasional C. [ ] Frequent 644 Grinding: A. [ ] None B. [ ] Mild C. [ ] Moderate D. [ ] Severe 645 Locking: A. [ ] None B. [ ] Occasional C. [ ] Frequent 646 647 648 649

OVERALL ACTIVITY LEVEL 650 20 - No limitations. I have a normal knee, and I am able to do everything including strenuous 651

sports and/or heavy labor. 652 16 - I can partake in sports including strenuous ones but at a lower level. I must guard my and 653

limit the amount of heavy labor or sports. 654 12 - Light recreational activities are possible with RARE symptoms. I am limited to light work. 655 8- No sports or recreational activities are possible. Walking activities are possible with RARE 656

symptoms. I am limited to light work. 657 4- Walking activities and daily living cause moderate problems and persistent symptoms. 658 0 - Walking and other daily activities cause severe problems. 659 660 WALKING 661 10 - Normal, unlimited. 662 8- Slight, mild problems. 663 6- Moderate problem, flat surface up to half a mile. 664 4- Severe problems, only 2-3 blocks. 665 2- Severe problems, need cane or crutches. 666 667 STAIRS 668 5- Normal, unlimited. 669 4- Slight, mild problems. 670 3- Moderate problems, only 10-15 steps possible. 671 2- Severe problems, require banister for support. 672 1- Severe problems, only 1-5 steps with support. 673 674 RUNNING 675 10 - Normal, unlimited, fully competitive. 676 8- Slight, mild problems, run at half speed. 677 6- Moderate problems, only 1-2 miles possible. 678 4- Severe problems, only 1-3 blocks possible. 679 2- Severe problems, only a few steps. 680 681 JUMPlNG AND TWISTING 682 5- Normal, unlimited, fully competitive. 683 4- Slight, mild problems, some guarding. 684 3 - Moderate problems, gave up strenuous sports. 685 2- Severe problems, affects all sports, always guarding. 686 1- Severe problems, only light activity possible (golf/swim). 687 688 If I had to give my knee a grade from 1 to 100, with 100 being the best, I would give my knee a: 689 690 691 Reprinted with permission. Wilk K, Romaniello W, Soscia S, Arrigo C, Andrews J. The 692 Relationship Between Subjective Knee Scores, Isokinetic Testing, and Functional Testing in the 693 ACL-Reconstructed Knee. JOSPT Volume 20 Number 2 August 1994. © William and Wilkins 694 695 696 697 698 699