Comparing VA and Non-VA Quality of Care: A Systematic Review106 C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of...

Transcript of Comparing VA and Non-VA Quality of Care: A Systematic Review106 C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of...

HEALTH POLICYComparing VA and Non-VA Quality of Care: A Systematic ReviewClaire O’Hanlon, MPP1,2, Christina Huang, PhD, MPH1,2, Elizabeth Sloss, PhD3,RebeccaAnhangPrice,PhD3, PeterHussey, PhD4,Carrie Farmer, PhD5,andCourtneyGidengil,MD,MPH4

1Pardee RANDGraduate School, Santa Monica, CA, USA; 2RAND Corp., Santa Monica, CA, USA; 3RAND Corp., Arlington, VA, USA; 4RAND Corp.,Boston, MA, USA; 5RAND Corp., Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

BACKGROUND: The Veterans Affairs (VA) health care sys-tem aims to provide high-quality medical care to veteransin the USA, but the quality of VA care has recently drawnthe concern of Congress. The objective of this studywas tosystematically review published evidence examining thequality of care provided at VA health care facilities com-pared to quality of care in other facilities and systems.METHODS:Building on the search strategy and results ofa prior systematic review, we searched MEDLINE (fromJanuary 1, 2005, to January 1, 2015) to identify relevantarticles on the quality of care at VA facilities compared tonon-VA facilities. Articles from the prior systematic reviewpublished from 2005 and onward were also included andre-abstracted. Studies were classified, analyzed, andsummarized by the Institute of Medicine’s qualitydimensions.RESULTS: Sixty-nine articles were identified (including31 articles from the prior systematic review and 38 newarticles) that address one or more Institute of Medicinequality dimensions: safety (34 articles), effectiveness (24articles), efficiency (9 articles), patient-centeredness (5articles), equity (4 articles), and timeliness (1 article).Studies of safety and effectiveness indicated generallybetter or equal performance, with some exceptions. Toofew articles related to timeliness, equity, efficiency, andpatient-centeredness were found from which to reliablydraw conclusions about VA care related to thesedimensions.DISCUSSION: The VA often (but not always) performsbetter than or similarly to other systems of care withregard to the safety and effectiveness of care. Addi-tional studies of quality of care in the VA are neededon all aspects of quality, but particularly with regardto timeliness, equity, efficiency, and patient-centeredness.

KEY WORDS: veterans; Veterans Affairs; Veterans Health Administration;

quality; systematic review.

J Gen Intern Med 32(1):105–21

DOI: 10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

© Society of General Internal Medicine 2016

INTRODUCTION

Providing high-quality health care is central to our na-tion’s commitment to veterans. The Veterans Affairshealth care system (VA), the nation’s largest integratedhealth care system, provides comprehensive health ser-vices to US military veterans who are enrolled. Howev-er, the quality of VA care is a longstanding area ofconcern.1, 2 As a result, the Veterans Access, Choiceand Accountability Act (VACAA), passed in 2014, man-dated an independent assessment of health care capabil-ities and resources of the Veterans Health Administra-tion.3 As part of this assessment, the Interim UnderSecretary for Health for VA called for a comprehensiveevaluation of BVA’s ability to deliver high-quality healthcare to Veterans.^4

Previous studies have systematically reviewed aspects ofcare at the VA.5–7 Two peer-reviewed articles based on one ofthese7 summarized the available evidence on medical8 andsurgical9 care quality through 2009. This review indicated thatin most studies, the care provided in the VA compares favor-ably to non-VA systems. However, quality may have changedin the last 6 years since this review, and concerns about qualityof care have continued to mount.10 To assess the quality ofcare provided by the VA, we performed a systematic review ofpublished comparisons of the quality of care in VA facilities toother settings.

METHODS

Search Strategy

We defined quality of care using the Institute of Medicine’s(IOM) definition, which is Bthe degree to which health ser-vices for individuals and populations increase the likelihood ofdesired health outcomes and are consistent with current pro-fessional knowledge.^11 Given the existence of a recent sys-tematic review on the quality of health care delivered in VAversus comparable non-VA settings, we chose to explicitlybuild upon and expand this work.7We use consistent methods,including the same search terms (Online Appendix) and data-base (MEDLINE). The dates searched were limited to the past10 years (January 1, 2005, to January 1, 2015) to ensure areasonable scope and up-to-date studies.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article(doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2) contains supplementary material,which is available to authorized users.

Received January 26, 2016Revised April 28, 2016Accepted June 7, 2016Published online July 15, 2016

105

JGIM

Article Screening and Data Abstraction

Titles and abstracts identified by our literature search werescreened by two reviewers with experience screening andabstracting data for health-related systematic reviews (CO,CH) under the supervision of a senior member of the studyteam with extensive clinical and systematic review experience(CG) for inclusion in full-text screening. If the article present-ed comparisons of quality of health care in the VA and non-VAsettings in the US, the full text of each article was reviewedindependently by both reviewers (CO, CH). We extracted thedata sources, geographical areas, clinical conditions, qualitydimensions, and comparability of measures in each sample.Studies were excluded if they included no original data; werecase reports; or used non-contemporaneous comparisons, un-equal or non-representative samples, or dissimilar or indirectquality measures. Data from each article, including the size ofthe VA and non-VA samples, years of data collection, controlvariables, and primary and secondary outcomes, were ab-stracted by one reviewer and double-checked by another re-viewer (CO, CH). Disagreements were resolved by a seniorteam member (CG).

Quality Assessment

Article quality was assessed using the criteria developed inthe original review for assessing comparative health carequality studies.7 Briefly, six elements were used, includingwhether: (1) time periods during which the VA and non-VA patients were studied were sufficiently contemporane-ous; (2) VA and non-VA samples were comparable insize/scope; (3) quality measurements were assessed usingspecified and identical indicators with a similar assessmentformat; (4) quality measures were meaningfully associatedwith outcomes; (5) measures were clinically relevant andimportant; and (6) the statistical methodology was sound.Each factor was graded (A for excellent, B for acceptable,C for unacceptable). The overall subjective assessment ofthe article was created, but this assessment was not anBaverage^ of individual component grades. Thus, an articlewith a critical flaw could be graded BC^ and rejected, evenif it scored well on other criteria. Articles were graded byone reviewer and double-checked by the other reviewer(CO, CH). Disagreements were resolved in consultationwith the senior team member (CG).

Study Classification

Although we employed a nearly identical search andabstraction strategy, we organized article categories dif-ferently than the original review,7 which split articlesinto medical8 (non-surgical) and surgical9 care and byDonabedian’s quality triad of structure, process, andoutcome.12 To guide decision making about how toimprove quality at the VA, we organized our reviewusing the IOM’s six characteristics of high-quality care:

safe, timely, equitable, effective, efficient, and patient-centered,11 and then grouped similar kinds of outcomestogether. Timeliness as related to delays or wait timesfor receiving necessary medical care (e.g., time fromadmission to emergency surgery) was included in thisreview. Timeliness as it relates solely to access (e.g.,wait time for obtaining an appointment)—while a criti-cal issue currently facing the VA13—was not addressedbecause no studies directly comparing VA and non-VAsettings were identified.14 We included articles on effi-ciency if they assessed appropriateness (necessary careversus overuse). We excluded cost-efficiency articles, ascost comparisons between VA and other settings have anumber of limitations.15

We classified each study (both new and from theprior review) according to the direction of the statisti-cally significant differences in performance measures forthe VA care relative to a non-VA comparison group. IfVA quality of care was shown to be better than non-VAcare or if multiple results were reported and VA qualityof care was better in some instances and the same inothers, the study was classified as BVA better.^ If mul-tiple quality measures were reported and VA care wasbetter than non-VA on some and worse on others, thestudy was classified as Bmixed.^ If the quality of care inVA and non-VA did not differ, the study was classifiedas Bsame.^ If VA quality of care was shown to be worsethan non-VA, the study was classified as BVA worse,^ aswere studies with multiple results reported where thequality of care was worse in some instances and thesame in others.

Ensuring Comparability of Populations

Wherever possible, we report results adjusted for risk, comor-bidities, demographics, or other variables. Unadjusted resultsare noted. We included and emphasized studies that compareVA patients to veterans receiving care in non-VA settings. Wealso included studies that compared veterans receiving VAcare (referred to as BVA patients^) with individuals who arenot identified as veterans receiving non-VA care (referred to asBnon-veterans^).

RESULTS

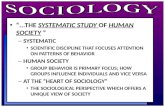

Searches yielded 461 articles, 306 of which were rejected atabstract screening; 155 proceeded to full-text screening. Datawere extracted from 69 articles; 31 of these were also includedin the previous review,7 yielding 38 new articles (Fig. 1).Included articles were categorized by quality dimension: safe-ty (34), timeliness (1), equity (4), effectiveness (24), efficiency(9), and patient-centeredness (5). Studies were sufficientlyheterogeneous to preclude pooling or other meta-analysis, soresults are presented narratively. The 34 articles on safety and24 on effectiveness are summarized in Table 1.

106 C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic Review JGIM

Safety

Safety measures focused on avoiding illness/injury topatients resulting from medical care, such as complica-tions following surgical procedures. Studies of morbidityand mortality were also included in this category, aswere studies about adherence to safety guidelines orbest practices. In 22 of 34 articles on safety, VA gener-ally performed as well (11 studies) or better (11 studies)than non-VA settings. VA fared worse in nine studiesand had mixed performance in three studies.

Mortality. VA facilities generally performed comparably orfavorably relative to other settings in terms of mortality.Mortality rates associated with specific conditions16–19 orfollowing surgery20–26 were often similar for VA patientscompared with non-veterans, and occasionally lower.17 How-ever, some studies found higher surgical mortality among VApatients compared with non-veterans.19, 22, 26–29 Lower mor-tality rates were observed after cataract surgeries for VApatients compared with veterans who are Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.30 Mortality among veterans residing inVA nursing homes and community nursing homes was simi-lar.31 Veterans undergoing dialysis treatment in VA and non-VA settings experienced similar mortality.32 Adjusted mortal-ity was lower among male VA patients compared with maleMedicare Advantage beneficiaries over 65 years old;33–36

results were similar for females.34 Mortality within 1 year ofadmission after hip fracture was 21 % lower among veteransadmitted to non-VA hospitals compared with VA patients.37

Mortality rates have declined more quickly in VA over timethan in non-VA settings.38

Morbidity.VA facilities had mixed results with respect tomost studies of morbidity. Postoperative morbidity waslower for VA patients compared with non-veterans insome surgeries,22, 25, 39 while for other surgeries it wassimilar.40–44 In a study comparing quality of care innursing homes, veterans in VA nursing homes were lesslikely to develop a pressure ulcer than veterans in com-munity nursing homes.31 However, other studies foundthat morbidity among VA patients is worse after pancre-atectomy28 and for male patients only after gastric by-pass, compared to patients in private sector hospitals(unadjusted).41

Complications.VA facilities had mixed results with respect tocomplications after surgery. Surgical complication rates weresimilar among VA patients and non-veterans.21, 23, 29 Highercomplication rates were observed for VA patients undergoingcataract surgeries than veterans who were Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.45 Among all kidney transplant recipi-ents, VA patients had higher graft failure risk than non-veterans.27

Other Safety Measures. VA hospitals were more likely tofollow best practices for central venous catheter bloodstreaminfection prevention comparedwith non-VA hospitals.46 How-ever, performance on the Agency for Healthcare Research and

Fig. 1 Flow Diagram of Included and Excluded Studies. Of the 461 articles identified using our search strategies, 306 were excluded at title/abstract screening and 155 were screened for inclusion using the full text of the article. Of these, 86 were excluded, leaving 38 new articles fordata abstraction. These articles were combined with the 31 articles from the prior review that met inclusion criteria, resulting in the 69 articles

included in this systematic review.

107C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic ReviewJGIM

Tab

le1Evidencetableforsafety

andeffectiveness

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

New

articlesabstracted

forthisreview

Bean-Mayberry

B,et

al.,2007

Effectiv

eness

[mixed]

Mult

ctrs

VA

comprehensive

Wom

ens’

Health

Centers

[N=8]

2003

Nat’l

Departm

entof

Health

andHum

an(D

HHS)Services

NationalCenters

ofExcellence[N

=13]

2003

None

Availabilityof

services

Preventivecancer

screeningand

generalreproductiv

eservices

were

uniformly

availableat

allcenters,

although

DHHScentersoffered

extensivereproductiv

eservices

on-site

morefrequently,andVA

centersmore

oftenhadon-site

mentalhealth

care

B

Boitano

LT,

etal.,2012

Safety[sam

e]Single

ctr

Veteransat

aVA

hospital[N

=322]

2006–2009

Single

ctr

Patientsat

Northwestern

Mem

orialHospital

[N=269]

2006–2009

Vascular

surgery

Postoperative

outcom

es(m

orbidity

andmortality),

adjusted

Multiv

ariate

analysisshow

edthat

hospitalsettin

gwas

notanindependent

predictorof

complications,major

adverseevents,o

rdeath,

suggestin

gno

difference

inoutcom

esbetweentheVA

andprivatesector

A/B

BondCA,

etal.,2008

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VA

hospitals

[N=84]

2006

Nat’l

Non-VA

hospitals

[N=1,041]

2006

None

Clin

ical

pharmacy

services

offered

8/15

clinical

pharmacyservices

were

morecommon

inVA

hospitals.

In-service

educationwas

higher

by25

%,clinical

research

154%,drug

protocol

managem

ent28

%,drug

therapycounselin

g80

%,participation

onrounds

38%,andadmission

drug

histories310%

(P<0.003)

A

BorzeckiAM,

etal.,2010

Safety[better]

Nat’l

IQI-related

dischargeat

VA

[N=403,828]

2003–2007

Nat’l

HCUP-N

ISIQ

I-relateddischarges

[sam

plesize

not

reported]

2003–2007

Multip

leInpatient

quality

indicators

Com

paring

VA

andHCUP-N

ISrisk-adjustedratesfrom

2003

through

2007,slopeestim

ates

forAMI,stroke,

hipfracture,pneumonia,andhip

replacem

entmortalityratesdeclined

morerapidlyin

theVA

A

ChakkeraHA,

etal.,2005

Safety[w

orse]

Nat’l

VA

patientswho

received

pretransplant

care

inVA

orpaid

byVA

[N=1,646]

1991–2001

Nat’l

Non-VA

patients

who

didnotreceive

pretransplantcare

inVA

orpaid

forby

VA

[N=77,715]

1999–2001

Kidney

transplant

Graftandpatient

survival

afterkidney

transplant,adjusted

Amongallrecipients,VA

usershada

20%

higher

risk

forgraftfailu

re(RR

1.21;95

%CI1.12–1.30)

and14

%higher

risk

ofmortality(RR1.14;95

%CI1.07–1.22)

comparedwith

non-VA

users

A

ChoiJC

,et

al.,

2009

Safety[sam

e]Single

ctr

VA

patients

[N=682]

2002–2006

Nat’l

Non-veteran

non-

VA

patients

[N=34,572]

2004

Cardio

In-hospitalmortality

rate

afterCABG,

unadjusted

Nosignificantdifference

inin-hospital

mortalityrate

formalepatients(1.6

%versus

2.4%;P=0 .20)

B

FihnSD

,et

al.,

2009

Safety[sam

e]Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=27,494]

2000–2005

Nat’l

Medicarepatients

inprivatesector

hospitals

[N=789,400]

2000–2005

IHD

Adjusted30-day

mortalityfollo

wing

AMI

Adjustedrelativ

eodds

ofdeathwere

notsignificantly

differentforVA

orprivatesector

hospitals(O

R1.02;95%

CI0.96–1.08)

A

French

DD,

etal.,2012a

Safety[w

orse]

Nat’l

Patientsin

VA

database

[N=20,191]

2007

Nat’l

Patientsin

Medicaredatabase

[N=137,726]

2007

Cataract

surgery

90-D

ayratesof

cataract

procedure

complications

Adjustedresults

resultedin

significant

odds

increasesof

correctiv

eprocedures

forroutinecataractsurgeriesperformed

inVA

(OR1.70;95

%CI1.58–1.82)

andforcomplex

cataract

surgery(O

R2.68;95

%CI2.24–3.20)

A

French

DD,

etal.,2012b

Safety[better]

Nat’l

Patientsin

VA

database

[N=19,721]

2007

Nat’l

Patientsin

Medicaredatabase

[N=129,302]

2007

Cataract

surgery

All-causemortality

follo

wingcataract

surgery,adjusted

Mortalityrisk

didnotdiffer

significantly

betweenthetwocohorts

attim

epointswith

in6months

follo

wingcataract

surgery.Medicare

patientsexperienced13–17%

excess

mortalityin

both

routineandcomplex

casesat

270and365days

A

(con

tinued

onnex

tpage

)

108 C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic Review JGIM

Table

1(con

tinue

d)

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

GonzalesR,

etal.,2006

Effectiv

eness

[worse]

Mult

ctrs

Patientsat

VA

ED

[N=1,125]

2003–2004

Mult

ctrs

Patientsat

matched

non-VA

EDs[N

=1,138]

2003–2004

Pulm

onary

Antibiotic

prescribingpatterns

inacuterespiratory

infections

Clin

ical

setting

(VAvs.non-VA)was

notindependently

associated

with

antib

iotic

prescribing.

Infour

cities,

VA

andnon-VA

EDswerevery

similar,butfarapartin

four

others.In

discordant

cases,theVA

ED

sites

show

edhigher

adjusted

ratesof

antib

iotic

treatm

ent

B

Hynes

DM,

etal.,2006

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Mult

ctrs

VA

hemodialysis

patients[N

=177]

2001–2003

Mult

ctrs

Private

sector

hemodialysis

patients[N

=131]

2001–2003

ESR

DCom

pliancewith

erythropoietin

guidelines,adjusted

Erythropoietin

was

administered

predom

inantly

subcutaneously

for52

%of

patientsin

VAversus

15%

inprivate-sector

facilities(P

<0.001)

B

Keatin

gNL,

etal.,2010

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

MaleVA

patients

[N=2,913]

2001–2005

Nat’l

Propensity

-matched

maleMedicare

patients[N

=2,913]

2001–2005

Lungcancer,

colorectal

cancer

End-of-lifecare

indicators,

propensity

adjusted

Men

treatedatVAwereless

likelythan

thosein

privatesector

toreceive

chem

owith

in14

days

ofdeath(4.6

%vs.7

.5%;P<0.001)

orto

beadmitted

toan

ICU

with

in30

days

ofdeath

(12.5vs.19.7;P<0.001),and

similarlylik

elyto

have

>1ERvisit

with

in30

days

ofdeath(13.1vs.1

4.7;

P=0.09)

A

Keatin

gNL,

etal.,2011

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=50,573]

2001–2005

Nat’l

FFSMedicare

patients

[N=143,504]

2001–2005

Colorectal,

lung,or

prostate

cancer;

lymphom

a;or

multip

lemyeloma

High-quality

cancer

care

process

measures,propensity

adjusted

Forcoloncancer,VA

hadhigher

rates

ofdiagnosisatearlierstage(P

<0.001)

andresection(P

=0.01),butsimilar

ratesof

adjuvant

chem

o.Fo

rrectal

cancer,VA

hadhigher

ratesof

diagnosisat

earlierstage(P

=0.007),

butsimilarratesof

resectionor

adjuvant

chem

o/radiation.

Lungcancer

outcom

eswerenon-significant.

Outcomes

weremixed

forprostateand

hematologic

cancer

A/B

Landrum

MB,

etal.,2012

Safety

[better]

Nat’l

Males

over

65diagnosed/treated

forcertaincancers

atVA

[N=26,718]

2001–2005

Nat’l

Males

over

65with

certaincancers

usingMedicareFFS

[N=118,195]

2001–2005

Colorectal,

lung,or

prostate

cancer;

lymphom

a;or

multip

lemyeloma

Tim

eto

all-cause

deathandcancer-

attributable

death),

propensity

adjusted

VA

patientshadhigher

survival

rates

ofcoloncancer

(HR0.87;95

%CI

0.82–0.93)

andnon–sm

all-celllung

cancer

(HR0.91;95

%CI0.88–0.95)

andsimilarsurvival

ratesof

rectal

cancer,sm

all-celllung

cancer,diffuse

large–B-celllymphom

a,andmultip

lemyelomacomparedto

similarFFS

Medicarepatients

A

Liu

CF,

etal.,

2008

Effectiv

eness

[worse]

Nat’l

Veteranswho

are

prim

arycare

users

at76

VA-staffed

community

clinics

[N=17,060]

2000–2001

Nat’l

Veteranswho

are

prim

arycare

users

at32

non-VA

contract

community

clinicsreceiving

capitatio

n[N

=6,842]

2000–2001

DM,

pulm

onary

Outpatient

service

utilizatio

nand

receiptof

prim

ary

care

services,

adjusted

Oddsratio

sfortheproportio

nof

contract

andVA-staffed

clinic

diabetic

patientsreceivingaretin

alexam

were

(OR0.72;95

%CI0.55-0.93)

and

COPD

patientsreceivingaflushot

(OR0.73;95

%CI0.55–0.99)

A

(con

tinued

onnex

tpa

ge)

109C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic ReviewJGIM

Table

1(con

tinue

d)

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

LuH,et

al.,

2010

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Mult

ctrs

Veteranswho

died

inaVA

facility

[N=520]

NR

Mult

ctrs

Veteranswho

died

inanon-VA

facility

[N=89]

NR

None

Perceptio

nsof

the

care

andservices

during

lastmonth

oflife

Patientswho

died

intheVAweremore

likelyto

have

hadapalliativecare

consult(67

%vs.21%;P

<0.001)

and

tohave

died

inapalliativecare

orhospiceunit(47%

vs.16

%;

P<0.001),butthey

weremorelik

ely

todiein

ICU

(26%

vs.13

%;

P=0.01)andless

likelyto

diein

anursinghome(0

%vs.26

%;

P<0.001)

B

Lynch

CP,

etal.,2010

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

Veteranswho

had

used

VA

facilities

inthelastyear

[N=1,342]

2003

Nat’l

Veteranswho

had

notused

VA

facilitiesin

thelast

year

[N=3,159]

2003

DM,

Preventive

care

Qualityof

diabetes

care,adjusted

VA

usersweremorethan

twiceas

likelyto

have

received

foot

exam

sby

aprovider

(OR2.59;95

%CI1.76–

3.83),pneumonia

shots(O

R2.30;95

%CI1.68–3.14),andflushots(O

R2.05;95

%CI1.44–2.92).VA

users

had60–70%

greaterlik

elihoodof

A1c

tests,and2+

provider

visitsin

thelast

12months

A

NelsonKH,

etal.,2011

Effectiv

eness

[ sam

e]Mult

ctrs

VA

patients

[N=150]

2009

Mult

ctrs

Patientsat

anacadem

icmedical

center

[N=150]

2009

IHD

Appropriate

use

ofstress/rest

myocardial

perfusionim

aging

(MPI),unadjusted

The

majority

ofthestudieswere

orderedforappropriateindicatio

n(67.3

%in

VAvs.74

%in

academ

icpractice)

(P=0.272)

B

ParikhDS,

etal.,2011

Effectiv

eness

[sam

e]Mult

VISNs

VA

patients

[N=378]

2005–2006

Mult

VISNs

Medicarepatients

[N=25,534]

2005–2006

ESR

DMethodof

vascular

access

forfirst

outpatient

dialysis

Adjustin

gforpatient

demographics

andcomorbiditiesonly,VA

patients

hadgreaterlik

elihoodof

arteriovenous

fistulas

(AVF)use(preferred

byguidelines)(O

R=1.70;95

%CI

1.31–2.20),butaccountin

gforpre

end-stagerenaldiseasecare

removed

thesignificantdifference

(OR1.28;95

%CI0.98–1.66)

A/B

Richardson

KK,etal.,2013

Safety[worse]

Nat’l

VA

users

[N=9,308]

2002–2008

Nat’l

Veteransat

non-VA

hospitals[N

=1,881]

2002–2008

Orthopedic

surgery

Tim

ebetween

admission

and

repair,

1-year

mortality

Likelihoodof

deathwith

in1year

ofadmission

was

21%

less

forveterans

admitted

tonon-VA

hospitals(RR=

0.79;95

%CI0.71–0.88;

P<0.001)

A

RivardPE

,et

al.,2010

Safety[w

orse]

Nat’l

VA

hospitals

[N=116]

2003–2004

Nat’l

Non-VA

hospitals

(HCUP-NIS)

[N=992]

2003–2003

None

Patient

Safety

Indicators

(PSIs),

adjusted

VA

hadhigher

composite

PSI

[VA:

1.11895

%CI(1.071–1.164),

HCUP-N

IS:0.98795

%CI

(0.977–0.997)].VA

also

hadhigher

foreignbody

leftin

during

procedure,

iatrogenic

pneumothorax,

postoperativehemorrhage,

postoperativewound

dehiscence.

HCUP-NIS

hadmorepostoperative

sepsisthan

VA,w

ithasm

allo

verlap

ofconfidence

intervals.Nosignificant

differencesforotherPS

Isevaluated

A

(con

tinued

onnex

tpage

)

110 C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic Review JGIM

Table

1(con

tinue

d)

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

Rosen

AK,

etal.,2005

Safety[m

ixed]Nat’l

VA

users

[N=281,423]

2000–2001

Nat’l

Non-VA

(HCUP-

NIS

andMedicare)

[sam

plesizesnot

reported]

2000–2000

None

PSIs,risk-adjusted

VA-risk-adjusted

ratesarelower

than

HCUP-N

ISandMedicareeventrates

fordecubitusulcer,infectiondueto

medical

care,postoperativerespiratory

failu

re,andpostoperativesepsis.VA

PSIeventrateswerehigher

than

HCUP-N

ISandMedicareeventrates

forpostoperativephysiologicand

metabolic

derangem

entsandtechnical

difficulty

with

procedure.VA

PSI

eventrateswerehigher

than

HCUP-N

ISeventrates,butlower

than

Medicareeventrates,for

theremaining

indicators

A

Selim

AJ,

etal.,2010

Safety[better]

Nat’l

VA

users

[N=35,876]

1999–2003

Nat’l

MedicareAdvantage

cohort[N

=71,424]

1999–2003

None

2-Yearmortality,

probability

sameor

betterphysical

ormentalhealth

at2

years;adjusted

2-Yearmortalityrateswere11.8%

and

9.9%

fortheMedicareandVA,

respectiv

ely;

probability

ofbeingalive

with

thesameor

betterphysical

health

at2yearshigher

VA

comparedto

Medicare;sameor

bettermentalhealth

at2yearswas

also

significantly

higher

atVA

than

inMedicare.Propensity

scorematched

analyses

had

comparableresults

A

Tarlov

E,et

al.,

2012

Safety[sam

e]Nat’l

VA

users

[N=1,465]

1999–2001

Nat’l

MedicareFF

Susers

[N=1,042]

1999–2001

Colon

cancer

Overallandevent-

free

36-m

onth

survival,adjusted

Overallsurvival

hazard

ratio

swere

similarat

stages

1–3.

Event-free

survival

hazard

ratio

swerealso

not

significantly

different

A

Trivedi

AN,

etal.,2011

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=293,554]

2000–2007

Nat’l

MedicareAdvantage

(MA)enrollees

[N=5,768,573]

2000–2007

DM,IH

D,

HTN,

Preventive

care

Health

care

Effectiv

enessData

andInform

ationSet

(HEDIS),External

Peer

Review

Program

(EPR

P)

indicators

The

VA

hadhigher

aggregate

performance

than

MA

for10

of11

measuresin

theinitial

year

ofassessment,andall12

measuresin

the

finalyear.Adjusteddifferencesrange

from

4.3percentage

points(95%

CI

3.2–5.4)

forcholesteroltestin

gin

CHD

to30.8

percentage

points(95%

CI

28.1–33.5)

forcolorectal

cancer

screening

A/B

Vaughan-

SarrazinMS,

etal.,2007

Safety[w

orse]

Nat’l

MaleVA

users

[N=139,331]

1996–2002

Nat’l

MaleMedicare

patients

[N=1,212,729]

1996–2002

Cardio

30-,90-,365-Day

mortality,adjusted

AdjustedmortalityafterCABG

was

higher

(P<0.001)

inVA

users

comparedwith

nonusersat30,9

0,and

365days

(ORs1.07,1.07,1.09).Fo

rPCI,adjusted

mortalityat

30and90

days

was

similar(N

S),buthigher

for

VA

usersat

365days

(OR1.09)

A

WangA,et

al.,

2005

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VA

users

[N=3,391]

2000

Nat’l

Non-VA

users

[N=178,735]

2000

Overw

eight/

obesity

Associatio

nbetween

obesity

andweight

advice,adjusted

Obese

VAusersweretwiceas

likelyto

have

received

professional

advice

tolose

weight(O

R2.06;95

%CI1.64

to2.59)andas

likelyto

have

received

professional

advice

tomaintainweight

(OR1.72;95

%CI0.75

to3.97)

B

(con

tinued

onnex

tpage

)

111C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic ReviewJGIM

Table

1(con

tinue

d)

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

WangV,et

al.,

2013

Safety

[sam

e]Mult

VISNs

VA

dialysisusers

[N=381]

2007–2008

Mult

VISNs

Veteranswho

received

outpatient

dialysisexclusively

inVA-outsourced

settings[N

=659]

2007–2008

ESR

DAdjustedall-cause

hospitalizationand

mortalityat

1year,

adjusted

There

was

nodifference

inmortality

outcom

esam

ongveterans

who

received

outpatient

dialysisexclusively

inVA-outsourcedcomparedto

VA

dialysisusers(O

R0.80;95

%CI

0.48–1.3)

A

Weeks

WB,

etal.,2009

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VA

patients

[sam

plesize

not

reported]

2005–2006

Nat’l

MedicareFFS

patients[sam

ple

size

notreported]

2005–2006

Multip

leOutpatient

and

inpatient

quality

measures

The

VA

outperform

edMedicare

fee-for-serviceperformance

inone

measure

ofmam

mographyandtwo

measuresof

outpatient

diabetic

managem

ent.In

2005

and2006,the

VA

performed

betterthan

hospitals

contributin

gto

HospitalCom

pare

B

WestA,et

al.,

2006

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VA

users

[N=1,928]

2000

Nat’l

Veteran

VA

non-usersand

non-veterans

[N=12,461]

2000

None

Routin

echeckup

with

inlast2years

VA

patientsreported

higher

ratesof

seeing

adoctor

foraroutinecheckup

wi th

inthepast2years(91.6%;

P<0.001)

B

Articlesfrom

previous

review

(with

additio

nalinform

ationabstracted

asnecessary)

BansalD,

2005

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Single

ctr

VA

patients

[N=117]

2002

Nat’l

Registrynotfurther

described[sam

ple

size

notreported]

2002

IHD

Use

ofcertain

medications

among

patientswith

MI

Use

ofaspirin,

beta-blockers,ACE

inhibitors,heparin,

GP2

b/3a

inhibitors

was

higher

intheLittle

RockVA

comparedto

therestof

Arkansasand

theentireUS

B

BarnettMJ,

etal.,2006

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=123,633]

2002–2003

Nat’l

MedicareHMO

patients

[N=157,517]

2000–2001

Other

safety

Use

ofpotentially

inappropriate

medications

Com

paredwith

privatesector

patients,

VA

patientswereless

likelyto

receive

anyinappropriatemedication(21%

vs.

29%;P<0.001),andin

each

classificatio

n:alwaysavoid(2

%vs.5

%;P<0.001),rarely

appropriate(8

%vs.13

%;p<0.001),andsome

indicatio

ns(15%

vs.1

7%;P<0.001)

B

Berlowitz

DR,

etal.,2005

Safety

[mixed]One

VISN

Veteransin

VA

nursinghomes

[N=3,802]

1997–1999

Lrg

geo

area

Veteransin

contract

nursing

homes

[N=961]

1997–1999

Other

medical/

nonsurgical

condition

Risk-adjusted

rates

ofpressure

ulcer,

functio

naland

behavioral

decline,

mortality

Veteransin

VA

nursinghomes

were

significantly

(P<0.05)less

likelyto

developapressure

ulcer(O

R0.63)but

morelik

elyto

experience

functio

nal

decline(O

R1.6)

than

veterans

incommunity

nursinghomes.V

eteransin

VA

nursinghomes

weresimilarlik

ely

todieexperience

behavioral

decline

A

Bilimoria

KY,

etal.,2007

Safety

[sam

e]Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=513]

1985–2004

Nat’l

Academic

hospital

patients[N

=12756]

1985–2004

General

surgical,

surgical

oncology

60-D

ayand3-year

mortality

Unadjustedandadjusted

mortality

ratesat

60days

and3yearswere

comparablebetweenVA,academ

icandcommunity

hospitalsettingsfor

resectionof

stageIandIIpancreatic

cancer

B

Com

munity

hospital

patients[N

=18,299]

Cam

plingBG,

etal.,2005

Safety

[worse]

One

VISN

MaleVA

patients

[N=862]

1995–1999

Lrg

geo

Malenon-VA

patients[N

=27,936]1995–1999

Cancer

Survival

follo

wing

diagnosisof

lung

cancer

The

mediansurvival

was

6.3months

forVA

patientscomparedwith

7.9

monthsforpatientsin

therestof

the

state,andthe5-year

overallsurvival

rate

was

12%

forVA

patients

comparedwith

15%

forpatientsin

the

restof

thestate.The

hazard

ratio

for

VA

patientscomparedwith

non-VA

patientsis1.22

(P<0.001)

B

(con

tinued

onnex

tpage

)

112 C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic Review JGIM

Table

1(con

tinue

d)

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

Chi

RC,et

al.,2006

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VA

users

[N=3,265]

2003

Nat’l

Veteran

non-VA

users[N

=10,677]

2003

Preventiv

ecare

Influenzaand

pneumococcal

vaccination

Amongveterans,influenzaand

vaccinationrateshigher

forVA

users

comparedto

non-users.Fo

rveterans,

VA

care

was

independently

associated

with

influenzavaccination(adjusted

OR1.8;

95%

CI1.5–2.2)

and

pneumococcalvaccination(adjusted

OR2.4;

95%

CI2.0–2.9)

A

Non-veterans

[N=40,331]

Fink

AS,et

al.,

2007

Safety

[better]

Nat’l

FemaleVApatients

[N=5,157]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Fem

aleprivate

sector

patients

[N=27,467]

2001–2004

General

surgical

30-D

aypostoperative

morbidity

and

mortality

Risk-adjusted

mortalityratesare

comparablebetweenPSandVA

patients,although

setting

ofcare

did

notenterthemortalityregression

model.Risk-adjusted

morbidity

was

higher

inthePS

comparedwith

theVA

OR0.8(95%

CI0.71–0.90)

B

Gill

JS,et

al.,

2007

Effectiv

eness

[worse]

Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=7,395]

1995–2004

Nat’l

Privately

insuredpatients

[N=144,651]

1995–2004

Other

surgical

Tim

eto

treatm

ent

BothVA-insured

andMedicare/

Medicaid-insuredpatientswere35

%less

likelyto

receivetransplantsthan

privatelyinsuredpatients(H

R0.65;95

%CI0.60–0.70;

P<0.001).VA

patientswereless

likelyto

beplaced

onthewait-list(H

R0.71;95

%CI

0.67–0.76),buteven

thoselisted

received

transplantsless

frequently

than

theprivatelyinsured(H

R0.89;9

5%

CI0.82–0.96)

A

Medicare/

Medicaidpatients

[N=357,345]

Glasgow

RE,

etal.,2007

Safety

[worse]

Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=377]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Private

sector

patients[N

=692]

2001–2004

Other

surgical

Postoperative

outcom

esAdjustin

gforcase

mix

differences,

postoperativemorbidity

andmortality

ratesforpancreatectomywerehigher

intheVA

comparedwith

thePS

(OR

1.58;95

%CI1.08–2.31and2.53

95%

CI1.02–6.29respectiv

ely)

A/B

HallBL,et

al.,

2007

Safety

[sam

e]Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=2,814]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Private

sector

patients[N

=4,268]

2001–2004

General

surgical,

head

and

neck

30-D

aymorbidity

andmortality;

Overall30-day

morbidity

andmortality

donotdiffer

significantly

intheVAvs.

PSin

risk-adjustedmodel.Mortality

eventrate

istoolow

toaccurately

evaluate,odds

ratio

formorbidity

associated

with

VA

care

is1.25

(95%

CI0.87–1.78)

B

Adverse

eventrates,

LOS

Henderson

WG,et

al.,

2007

Safety

[worse]

Nat’l

MaleVA

patients

[N=9,409,818]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Maleprivatesector

patients[N

=18,399]2001–2004

General

surgical

30-D

aypostoperative

morbidity

and

mortality

After

risk

adjustmentforpatient

comorbiditiesandseverity

ofillness,

theodds

ofmortalityat

30days

were

higher

intheVAcomparedwith

thePS

(OR1.23;95

%CI1.08–1.41).There

was

nosignificantdifference

inmorbidity

at30

days

amongthesites

A/B

HutterMM,

etal.,2007

Safety

[better]

Nat’l

MaleVA

patients

[N=30,058]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Maleprivatesector

patients[N

=5,174]

2001–2004

Vascular

30-D

aypostoperative

morbidity

and

mortality

Risk-adjusted

mortalitywas

comparableam

ongthetwogroups.

Accountingforcomorbiditiesand

severity

ofillness,postoperative

morbidity

rateswerelower

intheVA

populatio

n,OR0.84

(95%

CI

0.78–0.92)

A/B

(con

tinued

onnex

tpage

)

113C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic ReviewJGIM

Table

1(con

tinue

d)

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

JhaAK,et

al.,

2007

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

VHA

patients

[N=33,

504-74,250]

1995–2003

Nat’l

Representative

community

sample

[sam

plesize

not

reported]

1995–2003

Preventiv

ecare

Vaccinatio

nrates

Trendsin

influenzaandpneumonia

vaccinationratesweresignificantly

differentin

theVA

comparedto

inthe

BRFS

S(P

<0.001).Pneum

onia

hospitalizationdecreasedby

50%

amongelderlyVA

enrollees

but

increasedam

ongMedicareenrollees

by15

%(P

<0.001)

B

JohnsonRG

etal.,2007

Safety

[better]

Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=458]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Private

sector

patients[N

=3,535]

2001–2004

Vascular

30-D

aypostoperative

morbidity

and

mortality

After

risk

adjustment,no

significant

difference

in30-day

mortalityrates

amongVA

andPS

femalevascular

patients.After

adjustingforseverity

ofillness,30-day

complication/morbidity

ratesweresignificantly

lower

inVA

comparedwith

PS(O

R0.60;95

%CI

0.44–0.81)

B

Keyhani

S,et

al.,2007

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

Veteransreceiving

VHA/VHA

and

FFSMedicare/

VHA

and

MedicareHMOs

[N=171/1,009/

145]

2000–2003

Nat’l

Veteransreceiving

FFS

Medicare/

MedicareHMO

[N=3,552/576]

2000–2003

Preventiv

ecare

Influenzaaand

pneumonia

vaccination,

cholesterolscreening

Veteransreceivingcare

throughVA

reported

10%

greateruseof

influenza

vaccination(P

<0.05),14

%greater

useof

pneumococcalvaccination

(P<0.01),andanon-significant6%

greateruseof

serum

cholesterol

screening(P

=0.1)

than

veterans

receivingcare

throughMedicare

HMOs

B

Krein

SL,

etal.,2007

Safety

[better]

Nat’l

VA

hospitals

[N=119]

2005

Nat’l

Non-VA

hospitals

[N=421]

2005

Other

medical/

nonsurgical

condition

Regular

useof

specific

preventio

nmodalities

anda

composite

measure

Adjustedfindings

revealed

that

VA

hospitalsweresignificantly

morelik

ely

tousechlorhexidinegluconate(O

R4.8;

95%

CI1.6–15.0)and/or

tousea

compositeapproach

(OR2.1;

95%

CI

1.0–4.2)

ascomparedwith

non-VA

hospitals

B

Lancaster

RT,

etal.,2007

Safety

[sam

e]Nat’l

Procedures

atVA

hospitals[N

=237]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Procedures

atuniversity

hospitals[N

=783]

2001–2004

General

surgical

Postoperative30-day

morbidity

and

mortalityLOS,need

forre-operatio

n,postoperativeevents

Risk-adjusted

outcom

essuggestthat

30-day

postoperativemorbidity

and

mortalityratesin

theVA

compared

with

thePS

forhepatic

resections

donotvary

significantly.After

risk

ad-

justment,morbidity

ratesandmortality

werecomparablein

VA

andPS.

Com

paring

morbidity

ofVAw/PS

OR

was

0.94

(95%

CI0.62–1.42)

and

mortalityORwas

1.62

(95%

CI

0.61–4.32)

A/B

Lautz

DB,

etal.,2007

Safety

[worse]

Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=374]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Private

sector

patients[N

=2,064]

2001–2004

Other

surgical

30-D

aypostoperative

outcom

es:morbidity

andmortality,LOS

Nosignificantdifference

inpostoperativemorbidity

ormortality

amongwom

enin

theVAversus

non-VA

settings(16.07

vs.12.02%;

P=0.21

and0.89

vs.0.42

%;

P=0.47).Unadjustedandadjusted

morbidity

rateswerehigher

among

men

treatedat

theVAversus

non-VA

(OR2.77;95

%CI1.78–4.31

unadjusted

andOR2.29;95

%CI

1.28–4.10adjusted)

A/B

(con

tinued

onnex

tpage

)

114 C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic Review JGIM

Table

1(con

tinue

d)

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

NelsonKM,

etal.,2005

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

Veteranswith

some

VA

care

[N=254]

2000

Nat’l

Adults

with

other

insurancetypes

[N=10,632]

2000

DM

Diabetesself-

managem

entand

preventiv

ecare

practices

Personswho

received

care

throughthe

VAweremorelik

elyto

reporttaking

adiabetes

educationclassandHbA

1ctestingthan

thosecoveredby

private

insurance

B

Veteranswith

all

VA

care

[N=281]

Neumayer

L,

etal.,2007

Safety

[sam

e]Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=644]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Privatesector

patients[N

=3,179]

2001–2004

General

surgical

30-D

aypostoperative

morbidity

and

mortality,LOS

After

adjustingforcomorbiditiesand

preoperativ

efactors,therewas

nosignificantdifference

in30-day

morbidity

ormortalityin

female

patientsat

theVA

comparedwith

the

PS(O

R1.40;95

%CI0.89–2.20)

B

Rehman

SU,

etal.,2005

Effectiv

eness

[better]

One

VISN

VA

patients

[N=12,366]

2001–2003

Lrg

geo

Non-VA

patients

[N=7,734]

2001–2003

HTN

Control

ofblood

pressure

below

140/90

mmHg

Blood

pressure

controlwas

comparableam

ongwhite

hypertensive

men

atVA(55.6%)andnon-VA(54.2

%)settings(P

=0.12).In

contrast,BP

controlwas

higher

amongAfrican

American

hypertensive

men

atVA

(49.4%)comparedwith

non-VA

(44.0

%)settings(P

<0.01),even

afterrisk

adjustment

A

RossJS,

etal.,2008

Effectiv

eness

[better]

Nat’l

Adults

receiving

care

atVAMCs

[N=10,007]

2000,2004

Nat’l

Adults

receiving

care

elsewhere

[N=393,873]

2000,2004

DM,IH

D,

HTN,

preventiv

ecare

Self-reporteduseof

17recommended

health

care

services

VA

care

was

associated

with

greater

useof

recommendedservices

inboth

yearsof

study(6/17services

more

used

in2000,12/17moreused

in2004)

B

Selim

AJ,

etal.,2007

Safety

[better]

Nat’l

VHA

patients

[N=16,725

atbaselin

eand

12,177

atfollo

w-up]

1998–2000

Nat’l

MedicareAdvantage

Program

patients

[N=62,614

atbaselin

eand

26,225

atfollo

w-up]

1998–2000

None

Risk-adjusted

2-year

mortality,change

inphysical

andmental

health

status

Low

errisk-adjustedmortalityin

the

VA

comparedto

MA

(2-yearmortality

7.6%

inVAvs.9.2%

inMA);VA

patientshadaslightly

higher

probability

than

Medicarepatientsof

beingalivewith

thesameor

better

mentalhealth

(71.8%

vs.70.1

%;

P=0.002)

B

Selim

AJ,

etal.,2006

Safety

[better]

Nat’l

VHA

patients

[N=420514]

1999–2004

Nat’l

Medicare

Advantage

Program

[N=584294]

1998–2004

Other

medi cal/

nonsurgical

condition

Risk-adjusted

mortality

After

adjustingforcase

mix,theHR

formortalityin

Medicarewas

significantly

higher

than

that

inVA

(HR,1.40;95

%CI=

1.38–1.43)

B

Selim

,AJ,

etal.,2009

Safety

[better]

Nat’l

Medicaid-eligible

VHA

patients

[N=2,361]

1999–2000

Nat’l

Medicaid-eligible

Medicare

Advantage

patients

[N=1,912]

1999–2000

Other

medical/

nonsurgical

condition

3-Yearrisk-adjusted

mortalityrate

The

adjusted

HRof

mortalityin

the

MA

dual

enrollees

was

significantly

higher

than

inVA

dual

enrollees

(HR

1.26;95

%CI1.04–1.52)

B

TurrentineFE,

etal.,2007

Safety

[sam

e]Nat’l

VA

patients

[N=178]

2001–2004

Mult.

ctrs

Privatesector

patients[N

=371]

2001–2004

Other

surgical

30-D

aymorbidity

andmortality

Mortalityeventrate

was

toolow

for

adjustment.Adjustin

gfor

comorbidities,the30-day

postopera-

tivemorbidity

ratio

inVAversus

the

PSwas

nolonger

significant(adjusted

OR1.33,9

5%

CI0.49–3.61compared

with

unadjusted

OR2.75;95

%CI:

1.55–4.91)

B

(con

tinued

onnex

tpa

ge)

115C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic ReviewJGIM

Table

1(con

tinue

d)

Autho

r,year

Qua

lity

dimension

(s)

[assessm

ent*]

Data

level

VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Data

level

Non

-VA

sample

[sam

plesize]

Years

collected

Con

dition

sOutcomes

Primaryfind

ings†

Final

grad

e‡

Weeks

WB,

etal.,2008

Safety

[mixed]One

VISN

MaleVA

enrollees

receivingcare

with

inVA

[N=50,429]

1998-2000

Lrg

geo

MaleVA

enrollees

receivingcare

outsideVA

[N=74,017]

1998-2000

Patient

Safety

Indicators

Risk-adjusted

rates

ofnon-

obstetric

PSIs

Rates

similarfor9of

15PSIs,ulcer,

sepsis,iatrogenic

infection,

postoperativerespiratoryfailu

re,

postoperativemetabolic

derangem

ent

lower

inVA,mortalityhigher

inVA

forlow-riskDRGs

B

Weiss

JS,etal.,

2006

Safety

[sam

e]One

VISN

VA

patients

[N=140]

1997–2002

Lrg

geo

Private

sector

patients[N

=6,949]

1997–2002

Vascular

Perioperative

mortality,stroke,

andcardiac

complications

After

risk

adjustment,having

surgery

attheVAwas

notasignificant

predictorof

death(O

R2.98;95

%CI

0.51-17.6),stroke

(OR0.95;95

%CI

0.3–3.4),o

rcardiaccomplications

(OR

1.07;95

%CI0.37–3.10)

B

Tableabbreviatio

ns:BRFSS

BehavioralR

iskFactorSurveilla

nceSystem

,CIconfidence

interval,C

OPDchronicobstructivepulmonarydisease,CABGcoronary

artery

bypass

graftin

g,DM

diabetes

mellitus,

DRG

diagnosis-relatedgroup,

ED

emergencydepartment,FFSfeeforservice,

ESR

Dendstagerenaldisease,

HRhazard

ratio

,HCUP-NIS

Health

care

CostandUtilizationProject

Nationw

ideInpatient

Sample,

HTN

hypertension,IQ

Iinpatient

quality

indicator,ICU

intensivecare

unit,

IHD

ischem

icheartdisease,

MAMedicareAdvantage,MImyocardialinfarctio

n,NRnotreported,ORodds

ratio

,PSI

patient

safety

indicator,PSprivatesector,R

Rrelativerisk,T

IAtransientischem

icattack,V

AVeterans

Affa

irs,VISNVeterans

Integrated

ServiceNetwork

*Weassessed

each

studyin

thereview

accordingto

thestatisticallysignificant

differences

inperformance

onquality

ofcare

measuresforVA

care

relativeto

anon-VA

comparisongroup.

IftheVA

quality

ofcare

was

show

ntobe

betterthan

quality

fornon-VA

care,the

studywas

classifiedas

BVAbetter.^

IfVA

quality

ofcare

was

betterinsomeinstancesandthesameinotherinstancescomparedtonon-VA

care

inthesamestudy,thestudywas

also

classifiedas

BVAbetter.^

Ifmultip

lequality

measureswerereported

inthestudyandVA

care

was

betterthan

non-VA

onsomeandworse

onothers,the

studywas

classified

asBm

ixed.^

Ifthequality

ofcare

intheVA

andnon-VA

didnotd

iffer,the

studywas

classifiedas

Bsam

e.^IftheVA

quality

ofcare

was

show

nto

beworse

than

non-VA

,the

studywas

classifiedas

BVAworse^

(aswerestudieswhere

thequality

ofcare

was

worse

insomeinstancesandthesamein

otherinstances)

†The

PrimaryFindingstext

hasbeen

draw

ndirectly

from

thereview

edarticlesandin

somecasesmay

besimila

ror

identical

tothearticle’stext

‡Eacharticle

was

givenan

overallassessmentof

quality

show

nin

theFinal

Grade

column.

This

assessmentwas

basedon

thefollo

wingcriteria:

timefram

es,samples

(bothVA

andnon-VA

),quality

measurements,o

utcomes,importance

ofmeasures,andstatistical

methods.E

achof

thesefactorswas

assigned

agrade(A,B

,orC)basedon

thedata

abstractiongradingguidelines

developedin

theoriginal

system

atic

review

.The

overallassessmentwas

predicated

ontheglobal

assessmentof

thearticle

consideringtheindividual

components,butwas

notan

average.

Thus,a

narticle

that

had,

forexam

ple,

acriticalfla

win

methodology

would

beaBC

,^even

ifotherissues

weresatisfactory.Articlesthat

received

anoverallgradeof

BC^wererejected

from

thereview

116 C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic Review JGIM

Quality’s (AHRQ) patient safety indicators was found to be amix of higher, lower, and similar rates at VA hospitals com-pared with non-VA hospitals.47–49

Effectiveness

Seventeen studies showed better performance in VA facilities,while three had similar performance, one was mixed, and threewere worse than non-VA settings.

Outpatient Care. Outpatient care was generally strong in VAfacilities. VA patients received higher quality care than non-veterans for one measure of preventive care mammography(85–90 % vs. 64–77 %) and two measures of outpatient diabeticmanagement (annual HbA1c test: 94–96 % vs. 70–81 %; annualeye examination: 67–85 % vs. 68–74 %) (no statistical tests).50

VA patients also received more effective care than non-veteransbased on 10 of 11 quality measures in the first study year and all12 quality measures in the second study year assessing diabetes,cardiovascular, and cancer screening care, with rate differencesranging from 4.3 percentage points (95 % confidence interval[CI] 3.2–5.4) for cholesterol testing in coronary heart disease to30.8 (95 % CI 28.1–33.5) for colorectal cancer screening.51

Receipt of diabetes education and annual HbA1c tests was higheramong VA patients compared with veterans in non-VA care.52

VA patients weremore likely than veterans receiving care outsideVA to receive recommended diabetes care, including being twiceas likely to have a foot examination and 60–70 % more likely tohave an eye examination, two ormoreA1c tests, and two ormoreproviders visits,53 a routine checkup within 2 years (91.6 %among VA patients compared to 80.6 % overall; P< 0.001),54

and influenza and pneumonia vaccinations (rates increased 10–240%),53, 55, 56 but similar rates of cholesterol screening.55 Bloodpressure control was higher among male African-American VApatients than male African-American non-VA patients (49.4 %vs. 44.0 %, P< 0.01) though similar among Caucasians.57 VApatients were more likely than non-VA patients to receive rec-ommended ambulatory preventive and disease management ser-vices,58 including influenza and pneumococcal vaccination.58, 59

These studies used a national sample comparison group of non-VA patients, which may have included both veterans and non-veterans. Obese VA patients were more than twice as likely tohave received advice to loseweight as veterans receiving non-VAcare and non-veterans and equally likely to have received adviceto maintain weight.60 However, in a study of veterans receivingprimary care at VA-staffed versus contract community clinics,veterans with diabetes at VA-staffed clinics were less likely toreceive a retinal examination (odds ratio [OR] 0.72, 95 % CI0.55–0.93) and veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonarydisease at VA-staffed clinics were less likely to receive a flu shot(OR 0.73, 95 % CI 0.55–0.99).61

Non-Ambulatory Care. In non-ambulatory settings, VA carewas generally of similar quality to care provided in non-VAfacilities. Compared with non-VA patients from the Medicarecancer patient database, VA patients had earlier diagnosis of

colon and rectal cancers, higher rates for three quality measures,similar rates for nine, and lower rates for one.62 Comparison of anacademic practice and aVAhospital found that appropriate use ofstress/rest myocardial perfusion imaging studies did not differbetween settings.63 Rates of hemodialysis via arteriovenous fis-tulas (which are preferred by guidelines over othermethods)werenot different between VA patients and Medicare patients afteraccounting for pre-end-stage renal disease care.64 VA patientsreceived higher quality care than non-veterans for nine out of tenmeasures of inpatient care and performed similarly on onemeasure.50

Medication Management. Medication management wasexamined in a number of settings, including outpatient,emergency department, and inpatient. Elderly VA patients wereless likely to receive inappropriate medication than were patientsin Medicare HMOs,65 and VA patients with acute myocardialinfarction were more likely to receive appropriate medicationsthan were non-VA patients.66 Observed compliance by providerswith erythropoietin administration guidelines was higher at VAthan in the private sector.67 Antibiotic prescribing practices weregenerally similar between seven VA and seven non-VA emer-gency departments; however, in the three cities in which pre-scription rates were not comparable between VA and non-VAsites, VA sites had much higher rates of antibiotic prescriptions.68

Availability of Services. The structure of women’s health carediffered at eight VAwomen’s health centers and 13 Departmentof Health and Human Services Centers of Excellence. Preventivecancer screening and general reproductive services wereavailable at all centers, while VA centers were less likely tooffer extensive reproductive services but more likely to offermental health care.69 Eight of 15 clinical pharmacy serviceswere more commonly provided in VA hospitals than non-VAhospitals [in-service education was 25 % higher (P = 0.003),clinical research 154 % higher (P< 0.0001), drug protocol man-agement 28 % higher (P < 0.0001), drug therapy counseling80 % higher (P< 0.0001), participation on rounds 38 % higher(P = 0.001), and admission drug histories 310 % higher(P< 0.0001)].70 VA patients and Medicare/Medicaid-insured pa-tients were less likely to receive kidney transplants than werepatients with private insurance.71

End-of-Life Care. VA tended to avoid inappropriate care andutilize palliative care at end of life. Increasing use ofchemotherapy at the end of life is associated with higher ratesof in-hospital deaths and later admission to hospice, which arelinked to lower quality end-of-life care.72–75 When comparingmale VA patients andMedicare patients with lung and colorectalcancer, VA patients were less likely to receive chemotherapywithin 14 days of death or to be admitted to an ICU within30 days of death, and they were similarly likely to have morethan one emergency room visit within 30 days of death.76

Among veterans who died in VA facilities, palliative care con-sults (67 % vs. 21 %, P < 0.001) and death in a dedicated

117C. O’Hanlon et al.: VA Quality of Care Systematic ReviewJGIM

palliative care, hospice unit, or intensive care unit were morecommon (47 % vs. 16 %, P< 0.001), and death in a nursinghome was less common (10 % vs. 26 %, P< 0.001) than amongveterans who died in non-VA facilities (all unadjusted results).77

Timeliness, Equity, Efficiency,and Patient-Centeredness

Since fewer than ten studies were found that related to each of thedimensions of timeliness, equity, efficiency, and patient-centeredness, we do not discuss the results of these studies indetail (results and evidence tables in Online Appendix). Thesingle study that addressed timeliness of care showed worseperformance among veterans in VA facilities relative to non-VAfacilities for time between hospital admission for hip fracture andsurgical repair.37 Four studies examined equity, with one studyshowing better performance on several chronic disease and pre-ventive measures,51 one study showing worse performance inVA facilities for emergency room visits among cancer patients inthe last month of life,76 and two studies showing similar equity in30-day post-admission mortality78 and graft failure.27 Nine arti-cles compared efficiency using utilization, with six studies show-ing worse performance in VA facilities on outcomes such asaverage length of stay and service utilization for patients ondialysis,32, 61, 79–82 two showing better performance for visits/admissions83 and generic drug utilization,84 and one with mixedresults for utilization-related inpatient quality indicators. Fivestudies examined patient-centeredness; three studies demonstrat-ed better patient and family satisfaction in VA facilities77, 85, 86

and two demonstrated similar performance in perceptions ofracial discrimination and satisfaction in transitional programsfor homeless veterans.87, 88

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we identified 69 studies comparingquality of care provided in VA facilities to non-VA care. Studiesof safety and effectiveness indicated generally favorable perfor-mance by VA facilities compared to non-VA facilities, with 22 of34 studies of safety and 20 of 24 studies of effectiveness showingthe same or better quality of care in VA facilities and the remain-der showing mixed (four studies) or worse (12 studies) perfor-mance. In terms of safety, VA facilities performed similarly orbetter in most, but not all, studies comparing morbidity andmortality. Results from studies about complications and patientsafety indicators were more mixed. In terms of effectiveness, VAfacilities had similar or superior quality to non-VA facilities withrespect to preventive, recommended, and end-of-life care, as wellas managingmedications. Non-ambulatory care studies indicatedsimilar care quality between VA and non-VA settings. However,studies on service availability hadmixed results. A comparison ofstudies included in the previous review, which included studiesfrom 1990 to 2009, and those identified in this review (2005 to2014) showed that while numerous studies have been publishedin the last 5 years, no stark trends can be observed in terms of

whether older or newer studies demonstrate systematically betteror worse performance in VA settings (Table 2).In keeping with the findings of the prior review, we find that

VA is generally more adherent to recommended care processesthan other systems of care. However, better processes did notnecessarily achieve better outcomes, as we observed few differ-ences in adjusted mortality. Although easy to obtain, mortalitymay not be the optimal outcome for comparison for severalreasons, some of which were noted in the prior review.7–9 Whilenearly every study we included attempted to risk-adjust theveteran and non-veteran populations, some excess baseline mor-tality risk may still be present, since veterans have comparativelyworse health status than the general population.89–91 Mortalityrates are also known not to be sensitive in detecting differences inthe quality of health care provided.92–94 Other outcomes, such ascomplications specific to a disease or procedure of interest, mightbe more revealing about meaningful quality differences in VAsettings than those included in this review.Our review builds on a previous review conducted in this

area,7–9 but both updates and expands upon it. Updating theresults of the prior review up to 2015 is critically important giventhe ongoing interest in the quality of care provided at the VA.95 Inaddition to categorizing the studies published since the priorreview, we also categorized the studies contained in the priorreview to provide a broad picture of quality at theVAover the lastdecade along the dimensions of health care quality proposed bythe IOM.11. This categorization allows us to highlight the gaps inresearch by dimension, whichmay help inform the investment ofresources for research and improvement by VA stakeholders.This study is subject to a number of limitations. The search

strategy employed was narrowly defined to align with themethods of the previous review, but this may have excludedrelevant studies. Most studies were not conducted with perfectlymatched comparison groups (i.e., veterans receiving care in VAand non-veterans in non-VA settings). While we used risk-adjusted or otherwise comparable results wherever possible, thismay not have accounted for unobservable differences betweenveterans and non-veterans. Although we included confidenceintervals or levels of significance in the evidence tables (Table 1and Online Appendix), it was not always possible to determinewhether lack of a significant difference was due to an underpow-ered study versus evidence of a lack of a difference. However,while many of the studies used large, nationally representative

Table 2 Comparison of studies included in the prior and currentreview

Outcomes Articles

Better SameMixedWorse Total