Common Acute Hand Infections Aapf

-

Upload

jorge-palazzolo -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Common Acute Hand Infections Aapf

copiously, irrigated to remove debris andpurulent material. When an abscess hasformed or pus is present, incision anddrainage are necessary. Devitalized andT

he hand can easily be in-jured during everyday ac-tivities. Any trauma to thehand, particularly a pene-trating trauma, may intro-

duce damaging pathogens. The hand’scompartmentalized anatomy may con-tribute to the development of an infec-tion. If an infection is not appropriatelydiagnosed and treated, significant mor-bidity can result.

Some general wound-care principlesapply to all hand infections.1,2 Most handinfections can be treated with an initialperiod of rest, immobilization, and eleva-tion. Splint immobilization and elevationcan protect the affected area, minimizeedema, and decrease pain. If a single digitis infected, a finger splint supporting theinterphalangeal joints in extension is usu-ally adequate. If the palm, the metacar-pophalangeal (MCP) joint, or larger por-tions of the hand are infected, splinting ina position of function (Figure 1) can helpprotect against flexion contractures andhasten rehabilitation.

Open wounds should be gently, but

Hand infections can result in significant morbidity if not appropriately diagnosed andtreated. Host factors, location, and circumstances of the infection are important guides toinitial treatment strategies. Many hand infections improve with early splinting, elevation,appropriate antibiotics and, if an abscess is present, incision and drainage. Tetanus pro-phylaxis is indicated in patients who have at-risk infections. Paronychia, an infection ofthe epidermis bordering the nail, commonly is precipitated by localized trauma. Treat-ment consists of incision and drainage, warm-water soaks and, sometimes, oral antibi-otics. A felon is an abscess of the distal pulp of the fingertip. An early felon may beamenable to elevation, oral antibiotics, and warm water or saline soaks. A more advancedfelon requires incision and drainage. Herpetic whitlow is a painful infection caused by theherpes simplex virus. Early treatment with oral antiviral agents may hasten healing. Pyo-genic flexor tenosynovitis and clenched-fist injuries are more serious infections that oftenrequire surgical intervention. Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis is an acute synovial spaceinfection involving a flexor tendon sheath. Treatment consists of parenteral antibioticsand sheath irrigation. A clenched-fist injury usually is the result of an altercation andoften involves injury to the extensor tendon, joint capsule, and bone. Wound exploration,copious irrigation, and appropriate antibiotics can prevent undesired outcomes. (Am FamPhysician 2003;68:2167-76. Copyright© 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

Common Acute Hand InfectionsDWAYNE C. CLARK, CDR, MC, USN, Naval Hospital Jacksonville, Jacksonville, Florida

COVER ARTICLEPRACTICAL THERAPEUTICS

Members of variousfamily practice depart-ments develop articlesfor “Practical Therapeu-tics.” This article is onein a series coordinatedby the Department ofFamily Medicine atNaval Hospital Jack-sonville, Jacksonville,Fla. Guest editor of theseries is Anthony J.Viera, LCDR, MC,USNR.

See page 2113 fordefinitions of strength-of-evidence levels.

FIGURE 1. The position of function, a safesplint position for the hand. The hand isheld as if holding the bowl of a wineglass. The wrist should be extendedapproximately 25 degrees and shouldallow alignment of the thumb with theforearm. The metacarpophalangeal jointshould be moderately flexed to 60 de-grees, and the interphalangeal jointsshould be slightly flexed (10 degrees forthe proximal interphalangeal joint and 5 degrees for the distal interphalangealjoint). The thumb should be abductedaway from the palm.

5°

10°60°

25°

Downloaded from the American Family Physician Web site at www.aafp.org/afp. Copyright© 2003 American Academy ofFamily Physicians. For the private, noncommercial use of one individual user of the Web site. All other rights reserved.

contaminated tissue serves as a potent culturemedium and should be promptly debrided.Minor infections may resolve with these mea-sures alone.

More severe infections require oral or par-enteral antibiotics and, possibly, surgical inter-vention. Moist heat may be used to increaselocal circulation and may enhance antibioticdelivery to the tissue. Photographs and dia-grams of the hand may be helpful in assessingthe success of therapy. All tetanus-pronewounds (e.g., soil, animal, oral, fecal expo-sure) require tetanus prophylaxis.

It is important to assess the patient’s underly-ing medical status as well as the circumstancesof the infection (Table 1).1-10 Antibiotic selec-tion is guided by a knowledge of the organ-isms encountered in common hand infections(Table 2).

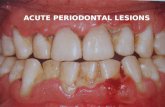

ParonychiaParonychia is an infection of the perionych-

ium (also called eponychium), which is theepidermis bordering the nail. Paronychiaresults in swelling, erythema, and pain at thebase of the fingernail (Figure 2). A review ofacute and chronic paronychia was recently

2168 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 / DECEMBER 1, 2003

TABLE 1

Host Factors and Important Considerations in Common Hand Infections

Host factor Considerations

Diabetes mellitus Higher incidence of mixed and pure gram-negative organisms (approaching 30 to 40 percent) requiring use of broader spectrum antibiotics. Susceptible to more severe infections and more likely to require surgicalintervention. Patients on renal dialysis pose the highest risk.8

Immunocompromised state More susceptible to opportunistic infections.(patients on Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis as well as cutaneous abscesses are known immunosuppressive therapy potential sequelae of disseminated Neisseria gonorrhoeae and are more and patients with HIV common in patients who are immunocompromised.1,3,5

infection or AIDS) Candidal flexor tenosynovitis infection has been reported in patients whoare immunocompromised.7

Intravenous drug use Mixed aerobic and anaerobic hand infections are common and usually caused by oral pathogens. Patients commonly present with subcutaneous abscesses and tendon sheath infections. They require the use of broader spectrum antibiotics.1-4

Tropical fish aquarium The culprit organism is more likely to be Mycobacterium marinum. This exposure organism is quite fastidious and often responsible for chronic, indolent

hand infections.9

Possible sexually transmitted Flexor tenosynovitis as well as cutaneous abscesses are known potential disease exposure sequelae of disseminated N. gonorrhoeae infection.1,3,5,6,10

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Information from references 1 through 10.

FIGURE 2. Acute paronychia of the index finger.

Reprinted with permission from Lamb DW, HooperG. Colour guide hand conditions. New York: ChurchillLivingstone, 1994:56.

The Author

DWAYNE C. CLARK, CDR, MC, USN, teaches in the Department of Family Practice atNaval Hospital Jacksonville, Jacksonville, Fla. He received his medical degree from DukeUniversity School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., and completed a residency in familymedicine at Naval Hospital Jacksonville.

Address correspondence to CDR Dwayne C. Clark, Department of Family Practice,Naval Hospital Jacksonville, 2080 Child St., Jacksonville, FL 32214 (e-mail: [email protected]). Reprints are not available from the author.

published in this journal.11 Acute paronychiais usually the result of localized trauma to theskin surrounding the nail plate. This infectionis usually the result of dishwashing, a mani-cure, an ingrown nail, or a hangnail, and usu-ally becomes evident two to five days post-trauma.12,13 Paronychia in children is usuallythe result of thumb sucking.

The responsible organisms in acute paro-nychia are usually Staphylococcus aureus andStreptococcus pyogenes; pseudomonas organ-isms are rarely responsible.3,4,11,12,14 Warmwater soaks alone may be effective if anabscess has not formed. If spontaneous

drainage does not occur or if an abscess is wellestablished, incision and drainage are war-ranted. Surgical treatment techniques are welldescribed in the medical literature.3,4,11,12

Direct damage and incision to the cuticle arenot recommended. For severe infections, anantistaphylococcal penicillin or a first-genera-tion cephalosporin should be given.3,12,14 Clin-damycin (Cleocin) or amoxicillin-clavulanatepotassium (Augmentin) may be considered ifanaerobes and Escherichia coli are suspectedorganisms.4,11 A tetanus booster should beadministered when appropriate. Chronicparonychia often is caused by a candidal infec-

DECEMBER 1, 2003 / VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 2169

TABLE 2

Common Hand Infections, Usual Offending Organisms, and Appropriate Therapeutic Regimens

Most common Condition offending organisms Recommended antimicrobial agents Comments

Paronychia Usually Staphylococcus First-generation cephalosporin or anti- Incision and drainage should be performed aureus or streptococci; staphylococcal penicillin; if anaerobes if infection is well established.pseudomonas, or Escherichia coli are suspected, oral If infection is chronic, suspect gram-negative bacilli, clindamycin (Cleocin) or a beta-lactamase Candida albicans.and anaerobes may inhibitor such as amoxicillin-clavulanate Early infections without cellulitis be present, especially potassium (Augmentin) may respond to conservative therapy.in patients with exposure to oral flora

Felon S. aureus, streptococci First-generation cephalosporin or anti- Incision and drainage should be performed staphylococcal penicillin if infection is well established.

Oral antibiotic therapy usually is adequate.

Herpetic Herpes simplex virus Supportive therapy Antivirals may be prescribed if infection whitlow types 1 and 2 has been present for less than 48 hours.

For recurrent herpetic whitlow, suppressive therapy with an antiviral agent may be helpful.

Consider antibiotics if secondarily infected.Incision and drainage are contraindicated.

Pyogenic flexor S. aureus, streptococci, Parenteral first-generation cephalosporin Early surgical assessment is suggested.tenosynovitis anaerobes or antistaphylococcal penicillin N. gonorrhoeae or C. albicans should be

and penicillin G suspected in sexually active or or immunocompromised patients.

Parenteral beta-lactamase inhibitor such as Incision and drainage with catheter ampicillin-sulbactam (Unasyn) irrigation of the sheath should be

Use ceftriaxone (Rocephin) or a performed if no improvement within fluoroquinolone if Neisseria gonorrhoeae the first 12 to 24 hours of conservative is suspected. therapy.

Human bite, S. aureus, streptococci, Parenteral first-generation cephalosporin or Prophylactic oral antibiotics should be clenched-fist Eikenella corrodens, antistaphylococcal penicillin and used if outpatient therapy is chosen.injury gram-negative bacilli, penicillin G Wounds should be explored, copiously

anaerobes or irrigated, and surgically debrided.Beta-lactamase inhibitor such as ampicillin- Hospitalization and parenteral antibiotics

sulbactam or amoxicillin-clavulanate often are indicated.potassium

orSecond-generation cephalosporin such as

cefoxitin (Mefoxin)

tion that may respond to treatment with atopical antifungal/steroid agent.11,12

FelonA felon is an abscess of the distal pulp or

phalanx pad of the fingertip.1,2,12,14,15 The pulpof the fingertip is divided into small compart-ments by 15 to 20 fibrous septa that run fromthe periosteum to the skin (Figure 3). Abscessformation in these relatively noncompliantcompartments causes significant pain, and theresultant swelling can lead to tissue necrosis.Because the septa attach to the periosteum ofthe distal phalanx, spread of infection to theunderlying bone can result in osteomyelitis.16

A felon usually is caused by inoculation ofbacteria into the fingertip through a penetrat-ing trauma. The most commonly affected dig-its are the thumb and index finger.15 Commonpredisposing causes include splinters, bits ofglass, abrasions, and minor puncture wounds.A felon also may arise when an untreatedparonychia spreads into the pad of the finger-

tip. Felons have been reported following mul-tiple finger-stick blood tests.12

Patients present with rapid onset of severe,throbbing pain, with associated redness andswelling of the fingertip (Figure 4). The paincaused by a felon is usually more intense thanthat caused by paronychia. The swelling willnot extend proximal to the distal interpha-langeal joint. Occasionally, the high pressurein the fingertip pad will cause a felon to spon-taneously drain, resulting in a visible sinus.

If diagnosed in the early stages of celluli-tis, a felon may be amenable to treatmentwith elevation, oral antibiotics, and warmwater or saline soaks.4,12,15 Bone and soft tis-sue radiographs should be obtained to eval-uate for osteomyelitis or a foreign body.Tetanus prophylaxis should be administeredwhen necessary.

If fluctuance is present, incision anddrainage are appropriate. The preferred tech-niques3,4,12,14,15 are a single volar longitudinalincision or a high lateral incision (Figure 5).Potential complications of a felon and felondrainage include an anesthetic fingertip, aneuroma, and an unstable finger pad. Thefamily physician’s comfort level and the avail-ability of a surgeon may determine whetherthis procedure is performed in the familyphysician’s office, or the patient is referred.

Incision techniques not recommendedinclude the “fish-mouth” incision, the “hockey

2170 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 / DECEMBER 1, 2003

FIGURE 3. The fingertip pulp, compartmentalized by 15 to 20 fibroussepta running from the periosteum to the skin. The small compart-ments contain eccrine sweat glands and fat globules. The sweat glandsprovide a potential portal of entry for bacteria. An abscess in thesenoncompliant compartments is called a felon.

FIGURE 4. Felon of the fingertip. The patientpresented with three days of increasedswelling, redness, and severe pain of the fingertip.

Cross section

Abscess (felon)

Fibrous septa

. . ...

. .

ILLU

STR

ATI

ON

BY

REN

EE L

. CA

NN

ON

Volar longitudinal or high lateral incision and drainage areindicated if a felon is fluctuant.

.

stick” (or “J”) incision, and the transverse pal-mar incision.3,4,12 These incisions are morelikely to result in painful, sensitive scars anddamage to neurovascular structures.

Postoperative care includes loose packing,splinting, and elevation of the hand forapproximately 24 hours. Dry dressing changeswith twice-daily saline soaks, range-of-motion activities and, eventually, scar massagemay accelerate return to normal activity.12

Gram stain should guide initial antibiotictherapy. As with paronychia, the most com-mon isolated organism is S. aureus. Empiricantibiotic coverage with a first-generationcephalosporin or antistaphylococcal penicillinusually is adequate treatment for an uncom-plicated felon. The recommended length oftreatment varies from five to 14 days anddepends on the clinical response and severityof infection.3,12 Methicillin-resistant S. aureushas been reported in felons and other handinfections; clinical response, as well as bacter-ial cultures, should be followed closely.17,18

Herpetic Whitlow Viral infections of the hand are rare, with the

exception of the clinical entity known as her-petic whitlow. Herpetic whitlow results fromautoinoculation of type 1 or type 2 herpes sim-plex virus into broken skin. The infection mayoccur as a complication of primary oral or gen-ital herpes lesions. Health care workers exposedto oral secretions (e.g., dental hygienists, respi-ratory therapists) can be affected if they are notusing universal precautions.

Signs and symptoms of herpetic whitlowinclude the abrupt onset of edema, erythema,and significant localized tenderness of theinfected finger. Often, the pain is out of pro-portion to the physical findings. Fever, lymph-adenitis, and epitrochlear and axillary lymph-adenopathy may be present. Small, clearvesicles initially are present. These may even-tually coalesce and, as the fluid becomescloudier, mimic a pyogenic bacterial infection.If in a distal location, herpetic whitlow maymimic paronychia or felon (Figure 6). A his-

DECEMBER 1, 2003 / VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 2171

FIGURE 5. Felon drainage. The incision location should avoid injury tothe flexor tendon sheath, digital neurovascular structures, and nailmatrix. The incision is performed under digital anesthesia, and atourniquet may be applied to enhance visualization of the surgicalfield. Of two commonly used techniques, the volar longitudinal inci-sion and the high lateral incision, the former is preferred. (A) The inci-sion starts 3 to 5 mm from the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint flexorcrease and extends to the end of the distal phalanx. The depth of theincision is to the dermis. (B) The subcutaneous tissues are then gentlydissected and explored with a small hemostat. Necrotic skin edges areexcised, and the abscess is decompressed and irrigated. The high lateralincision is made on the nonoppositional side of the appropriate digit(ulnar side of the index, middle, and ring fingers, and radial aspect ofthe thumb and fifth digit). (C) The incision starts 5 mm distal to theflexor DIP crease and continues parallel to the lateral border of the nailplate, maintaining approximately 5 mm between the incision and thenail plate border. This distance should allow for avoiding the morevolar neurovascular structures. (D) The incision is extended to endslightly distal to the unattached portion of the nail plate. The subcuta-neous tissue is sharply dissected just volar to the volar cortex of the dis-tal phalanx. The wound is bluntly dissected and explored, and theabscess is decompressed and irrigated. (E) In both techniques, thewound may be packed with sterile gauze. The gauze should beremoved in approximately 24 to 48 hours, and the wound allowed toclose by secondary intention.

ILLU

STR

ATI

ON

BY

REN

EE L

. CA

NN

ON

Volar longitudinalincision

Starts 3 to 5 mm from the distal interphalangealjoint

.

A

C

D E

B

tory of localized trauma to the nail cuticle maybe helpful in distinguishing herpetic whitlowfrom paronychia. A diagnosis of herpes sim-plex virus infection may be confirmed with aTzanck test, viral culture, or DNA amplifica-tion technique.

Herpetic whitlow usually is self-limited andresolves in two to three weeks. Treatmentwithin the first 48 hours of symptom onsetwith acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir),or valacyclovir (Valtrex) may lessen the sever-ity of infection, but randomized controlled tri-als have not been performed.19-21 Because viralshedding continues until the epidermal lesionis healed, contact with the lesion should beavoided by keeping the affected digit coveredwith a dry dressing. Incision and drainage ofthe lesion may cause viremia or bacterial infec-tion.2-4 Patients should be advised that theinfection recurs in 30 to 50 percent of cases,but the initial infection is typically the mostsevere. Treatment with antivirals may be bene-ficial for recurrent herpetic whitlow if initiatedduring the prodromal stage.19-23

Pyogenic Flexor Tenosynovitis The flexor tendons of the hand are

enclosed in distinct synovial sheaths. Theflexor tendon sheaths of the index, middle,

and ring fingers extend from the distal pha-langes to the distal palmar crease, and gener-ally do not communicate. The sheath encom-passing the fifth finger extends from its distalphalanx to the mid-palm, where it expandsacross the palm to form the ulnar bursa. Thethumb flexor sheath begins at the terminalphalanx and extends to the volar wrist crease,where it communicates with the radial bursa.Anatomic variations are frequent. For exam-ple, the radial bursa can communicate withthe ulnar bursa at the wrist (an infection ofthis area is called a “horseshoe abscess”).Thesynovial sheaths, poorly vascularized and richin synovial fluid, provide an optimal environ-ment for bacterial growth. Once inoculated,infection can spread rapidly within the con-fines of the sheath.2 Infection of the flexortendon sheath, known as pyogenic flexortenosynovitis (Figures 7 and 8), warrantsearly surgical evaluation.2-4,14,24

Patients with pyogenic flexor tenosynovitispresent with the four cardinal signs asdescribed by Kanavel: (1) uniform, symmetricdigit swelling; (2) at rest, digit is held in partialflexion; (3) excessive tenderness along theentire course of the flexor tendon sheath; and(4) pain along the tendon sheath with passivedigit extension.25 Pain with passive extensionhas been reported as the most clinically repro-ducible of these four signs.24,26

Patients typically recall some antecedenttrauma or puncture wound. The trauma oftenis at a flexor crease; this is where the tendonsheath is most superficial. Hematogenousspread to the sheath (i.e., Neisseria gonor-rhoeae) occurs rarely but should be suspectedif there is no puncture wound or history oftrauma.5,6

Early diagnosis and treatment of pyogenicflexor tenosynovitis is necessary to preventtendon necrosis, adhesion formation, andspread of infection to the deep fascial spaces.Distinguishing a subcutaneous abscess from atendon sheath infection can be challenging. Asubcutaneous abscess should not have tender-ness over the entire sheath, and passive mobil-

2172 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 / DECEMBER 1, 2003

FIGURE 6. Herpetic whitlow mimicking afelon. In a patient with whitlow, the pulp ofthe finger pad should be soft; a felon will feelsignificantly tense.

Reprinted with permission from Lamb DW, HooperG. Colour guide hand conditions. New York:Churchill Livingstone, 1994:62.

ity of the uninvolved segments should bepainless.15 Elevated sheath pressures consis-tent with compartment syndrome pressures(i.e., higher than 30 mm Hg) have been docu-mented in flexor tenosynovitis.27 Ultrasoundexamination may show an abnormal effusionor abscess in the tendon sheath.28

Infections in the early stage may respond tononoperative treatment that includes splint-ing, elevation, and intravenous antibiotics.Rings should be removed from the affectedfinger and other fingers of the hand as soon aspossible.

Causative agents for flexor tenosynovitistypically include Staphylococcus and Strepto-coccus species.1,2,24 Mixed infections should besuspected in patients who have diabetes or areimmunocompromised.8,24 Disseminated gon-orrhea5 and Candida albicans7 infection havebeen reported as causes of flexor tenosynovitisin immunocompromised patients.

Gram stain and wound culture growthshould guide antibiotic therapy. Empiric ther-apy should include parenteral penicillin pluseither an antistaphylococcal penicillin or afirst-generation cephalosporin.1,3,4,24 Alterna-tively, a parenteral beta-lactamase inhibitormay be used as monotherapy. Tetanus pro-phylaxis should be administered if necessary.

If there is no improvement within 12 to 24hours, surgical intervention is warranted.Early surgical treatment should be consideredif the patient is immunocompromised or hasdiabetes.24 Surgical treatment involves proxi-mal and distal tendon exposure, and carefulinsertion of a catheter or feeding tube into thetendon sheath with copious intraoperativeirrigation.1,4,15,24,25 Postoperatively, the cathe-ter may be left in place for 24 hours to allowfor further low-flow irrigation. One retrospec-tive study29 questioned the utility of postoper-ative irrigation and found no difference inoutcome whether the catheter was left in ortaken out. Parenteral antibiotic therapyshould be continued for at least 48 hours.Comparable oral antibiotic therapy shouldthen be instituted and continued for an addi-

Hand Infections

DECEMBER 1, 2003 / VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 2173

FIGURE 7. Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis.Appreciable pain along the tendon sheathwith passive extension of the digit often is thefirst clinical sign of this hand infection.

FIGURE 8. Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis of theindex finger of the right hand.

Reprinted with permission from Lamb DW, HooperG. Colour guide hand conditions. New York:Churchill Livingstone, 1994:58.

ILLU

STR

ATI

ON

BY

REN

EE L

. CA

NN

ON

Passive extension

If medical treatment of pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis showsno improvement in 12 to 24 hours, surgery is necessary.

tional five to 14 days on an outpatient basis.Physical and occupational therapy should beinitiated to reduce long-term disability fromscarring and contractures.

Human Bite and Clenched-Fist InjuriesHuman bite injuries to the hand usually

result from a direct bite or a “fight bite” (alsoknown as a “clenched-fist” injury).30-32 Directhuman bite injuries are often visually evident.A clenched-fist injury typically is character-ized by a 3- to 5-mm laceration on the dorsumof the hand or overlying an MCP joint (Figure9). Because of the innocent appearance of thisinjury, patients may not seek medical atten-tion and commonly present with advancedinfection.

A clenched-fist wound is the result of a fiststriking an object, such as another person’sface, with considerable force. A tooth may pen-etrate an extensor tendon and MCP joint cap-sule, sometimes fracturing a metacarpal orphalangeal bone. Because the injury occurswith the MCP joint in flexion, injuries to theextensor tendon and joint capsule can be over-looked easily during examination of the MCPjoint in extension. In a study of 191 patientswith clenched-fist injuries, 75 percent had aninjury to tendon, bone, joint, or cartilage.33

Recognition of the potential severity of theinjury is important in the management of aclenched-fist injury. Radiographs should beobtained to assess for fracture, foreign body,gas, or osteomyelitis. A thorough neurovascu-lar and musculoskeletal examination shouldbe performed. Extensor tendon functionshould be documented.

Puncture wounds should be extended prox-imally and distally while the physician is look-ing for extensor tendon disruption or injury.The wound should be explored, copiously

irrigated, and surgically debrided. Material forGram stain and aerobic/anaerobic culturesshould be obtained from deep within all sup-purative wounds before therapy is instituted.Gram stain results should guide initial antibi-otic therapy. The wound should not be su-tured but allowed to heal by secondary inten-tion. The hand should be splinted in aposition of function and elevated. Occupa-tional rehabilitation can be considered oncethe infection has cleared.

Human bite infections are often more viru-lent than animal bite injuries and are polymi-crobial in nature.30,31,34 Cultures grow an aver-age of five different organisms, three of whichare usually anaerobes.30 Isolated anaerobes arecommonly beta-lactamase producers. S. aureusand streptococci also are commonly isolated.

2174 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 / DECEMBER 1, 2003

FIGURE 9. Clenched-fist injury. Also known asa “fight-bite” injury, this serious injury typi-cally is characterized by a 3- to 5-mm lacera-tion on the dorsum of the hand or overlyingthe metacarpophalangeal joint.

Reprinted with permission from Lamb DW, HooperG. Colour guide hand conditions. New York:Churchill Livingstone, 1994:60.

Three fourths of patients with a clenched-fist injury alsoincur a tendon, bone, joint, or cartilage injury.

Eikenella corrodens, an anaerobic gram-nega-tive rod, has been found in 10 to 29 percent ofinfections.30

Patients who present early with uncompli-cated wounds (i.e., no joint capsule penetra-tion or tendon injury, and the injury hap-pened less than 24 hours earlier) should begiven prophylactic antimicrobial therapy.

The use of early prophylactic antibiotics inuncomplicated wounds is supported by onesmall, randomized prospective clinical trial.35

[Evidence level B, lower quality randomizedcontrolled trial] This trial compared mechan-ical wound care alone (N = 15) with woundcare plus prophylactic oral cefaclor (Ceclor),N = 16, or intravenous cefazolin (Kefzol) pluspenicillin G (N = 17). Patients with joint cap-sule penetration, tendon injury, and bitesolder than 24 hours were excluded from thestudy. All patients were hospitalized. The trialwas terminated early because the infectionrate in the group that received mechanicalwound care alone was extraordinarily high(47 percent).

None of the patients treated with antibioticsdeveloped a subsequent infection. The authorsconclude that, in the treatment of uncompli-cated clenched-fist injuries, mechanicalwound care alone is insufficient, and oral andintravenous antibiotics are equally efficaciousfor prophylaxis. This trial was emphasized in arecent Cochrane systematic review on antibi-otic prophylaxis for mammalian bites.36

Outpatient management for uncompli-cated wounds (as described above) can beconsidered after the wound has been ade-quately cleaned and explored. In outpatienttherapy, one of three treatment optionsshould be used: (1) amoxicillin-clavulanatepotassium; (2) penicillin (to cover E. corro-dens) plus an antistaphylococcal penicillin(such as dicloxacillin); or (3) penicillin plus afirst-generation cephalosporin. First-genera-tion cephalosporins are not effective asmonotherapy because some anaerobic bacte-ria and E. corrodens are resistant. In patientswho are allergic to penicillin, clindamycin plus

either a fluoroquinolone or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra) shouldprovide adequate coverage. A tetanus boostershould be administered if necessary.

Some clinicians believe that all clenched-fistinjuries warrant hospital admission and surgi-cal consultation.34 If treated on an outpatientbasis, the patient should return at 24 hours fora wound check. Hospital admission with par-enteral antibiotic administration should beconsidered for patients with any of the follow-ing: (1) diabetes or peripheral vascular disease;(2) immunocompromised state (secondary todisease or drugs); (3) wound older than 24 hours; (4) wound that involves injury to theextensor tendon, joint capsule, or bone; (5)questionable follow-up or compliance withantibiotic therapy; (6) systemic symptoms(e.g., fever, chills); or (7) cellulitis.30 If thepatient is hospitalized, a broad-spectrum par-enteral antibiotic (such as ampicillin-sulbac-tam [Unasyn] or ticarcillin-clavulanate potas-sium [Timentin]), or a second-generationcephalosporin such as cefoxitin (Mefoxin)should be administered.

Differential Diagnosis Several noninfectious conditions, some of

which can be difficult to distinguish, canmimic a hand infection.37,38 Crystalline depo-sition disease (e.g., gout, pseudogout), pyo-genic granuloma, acute calcium deposition,acute nonspecific flexor tenosynovitis, brownrecluse spider bites, rheumatoid arthritis, andforeign-body reactions can mimic an acutehand infection and should be considered inthe differential diagnosis.

The opinions and assertions contained herein arethe private views of the author and are not to beconstrued as official or as reflecting the views of theU.S. Navy Medical Corps or the U.S. Navy at large.

The author indicates that he does not have any con-flicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

Figure 1 provided by David Klemm. Figure 4 pro-vided by Anthony J. Viera, LCDR, MC, USNR.

Hand Infections

DECEMBER 1, 2003 / VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 2175

Hand Infections

REFERENCES

1. Hausman MR, Lisser SP. Hand infections. OrthopClin North Am 1992;23:171-85.

2. Nathan R, Taras JS. Common infections in thehand. In: Hunter JM, Mackin E, Callahan AD, eds.Rehabilitation of the hand: surgery and therapy.4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1995:251-60.

3. Moran GJ, Talan DA. Hand infections. Emerg MedClin North Am 1993;11:601-19.

4. Brown DM, Young VL. Hand infections. South MedJ 1993;86:56-66.

5. Krieger LE, Schnall SB, Holtom PD, Costigan W.Acute gonococcal flexor tenosynovitis. Orthope-dics 1997;20:649-50.

6. Schaefer RA, Enzenauer RJ, Pruitt A, Corpe RS.Acute gonococcal flexor tenosynovitis in an ado-lescent male with pharyngitis. A case report and lit-erature review. Clin Orthop 1992;281:212-5.

7. Townsend DJ, Singer DI, Doyle JR. Candidatenosynovitis in an AIDS patient: a case report. J Hand Surg [Am] 1994;19:293-4.

8. Gunther SF, Gunther SB. Diabetic hand infections.Hand Clin 1998;14:647-56.

9. Bhatty MA, Turner DP, Chamberlain ST. Mycobac-terium marinum hand infection: case reports andreview of literature. Br J Plast Surg 2000;53:161-5.

10. Gomperts BN, White LK. Gonococcal hand ab-scess. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2000;19:671-2.

11. Rockwell PG. Acute and chronic paronychia. AmFam Physician 2001;63:1113-6.

12. Jebson PJ. Infections of the fingertip. Paronychiasand felons. Hand Clin 1998;14:547-55.

13. Roberge RJ, Weinstein D, Thimons MM. Peri-onychial infections associated with sculpturednails. Am J Emerg Med 1999;17:581-2.

14. Harrison BP, Hilliard MW. Emergency departmentevaluation and treatment of hand injuries. EmergMed Clin North Am 1999;17:793-822.

15. Stern PJ. Selected acute infections. Instr CourseLect 1990;39:539-46.

16. Watson PA, Jebson PJ. The natural history of theneglected felon. Iowa Orthop J 1996;16:164-6.

17. Connolly B, Johnstone F, Gerlinger T, Puttler E.Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a fin-ger felon. J Hand Surg 2000;25:173-5.

18. Karanas YL, Bogdan MA, Chang J. Community ac-quired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureushand infections: case reports and clinical implica-tions. J Hand Surg 2000;25:760-3.

19. Mohler A. Herpetic whitlow of the toe. J Am BoardFam Pract 2000;13:213-5.

20. Crumpacker CS. Herpes simplex. In: Freedberg IM,Fitzpatrick TB, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology ingeneral medicine. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill,1999:2414-26.

21. Schwandt NW, Mjos DP, Lubow RM. Acyclovir andthe treatment of herpetic whitlow. Oral Surg OralMed Oral Pathol 1987;64:255-8.

22. Gill MJ, Arlette J, Buchan K, Tyrrell DL. Therapy forrecurrent herpetic whitlow. Ann Intern Med1986;105:631.

23. Laskin OL. Acyclovir and suppression of frequentlyrecurring herpetic whitlow. Ann Intern Med 1985;102:494-5.

24. Boles SD, Schmidt CC. Pyogenic flexor tenosynovi-tis. Hand Clin 1998;14:567-78.

25. Kanavel AB. Infections of the hand. A guide to thesurgical treatment of acute and chronic suppura-tive processes in the fingers, hand, and forearm.7th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1939.

26. Neviaser RJ. Tenosynovitis. Hand Clin 1989;5:525-31.

27. Schnall SB, Vu-Rose T, Holtom PD, Doyle B, Ste-vanovic M. Tissue pressures in pyogenic flexortenosynovitis of the finger: compartment syn-drome and its management. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]1996;78:793-5.

28. Cardinal E, Bureau NJ, Aubin B, Chhem RK. Role ofultrasound in musculoskeletal infections. RadiolClin North Am 2001;39:191-201.

29. Lille S, Hayakawa T, Neumeister MW, Brown RE,Zook EG, Murray K. Continuous postoperativecatheter irrigation is not necessary for the treat-ment of suppurative flexor tenosynovitis. J HandSurg 2000;25B:304-7.

30. Griego RD, Rosen T, Orengo IF, Wolf JE. Dog, cat,and human bites: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol1995;33:1019-29.

31. Kelleher AT, Gordon SM. Management of bitewounds and infection in primary care. Cleve Clin JMed 1997;64:137-41.

32. Perron AD, Miller MD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pit-falls in the ED: fight bite. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:114-7.

33. Patzakis MJ, Wilkins J, Bassett RL. Surgical findingsin clenched-fist injuries. Clin Orthop 1987;220:237-40.

34. Dellinger EP, Wertz MJ, Miller SD, Coyle MB. Handinfections. Bacteriology and treatment: a prospec-tive study. Arch Surg 1988;123:745-50.

35. Zubowicz VN, Gravier M. Management of earlyhuman bites of the hand: a prospective random-ized study. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991;88:111-4.

36. Medeiros I, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis formammalian bites (Cochrane Review). CochraneDatabase Syst Rev 2003;2:CD001738.

37. Louis DS, Jebson PJ. Mimickers of hand infections.Hand Clin 1998;14:519-29.

38. Matsui T. Acute nonspecific flexor tenosynovitis inthe digits. J Orthop Sci 2001;6:234-7.

2176 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 68, NUMBER 11 / DECEMBER 1, 2003