Combating Dehydration in Nursing Homes

Transcript of Combating Dehydration in Nursing Homes

-

8/9/2019 Combating Dehydration in Nursing Homes

1/6

-

8/9/2019 Combating Dehydration in Nursing Homes

2/6

DIETARY MANAGER30 DIETARY MANAGER30

FeatureArticle

dehydracombating

and UTIs inLong-Term

Care

by|Lisa Stewart, CDM, CFPPHelga Longino, RNDiane Burton, RN

Angie Corder, RD

and UTIs inLong-Term

Care

-

8/9/2019 Combating Dehydration in Nursing Homes

3/6

31

ion

billion per year. (Mentes)

Burger and colleagues call the constellation of malnutri-tion, dehydration, and weight loss in nursing homes one ofthe largest silent epidemics in this country. (Burger et al.)They describe hospitalization as a stressful event for frailelders. Lack of simple nutrients can have a profound ef-fect on quality of life as well, noted Burger and colleagues:Nursing home residents who do not receive adequate nu-

trition and hydration during the last months or years oftheir lives are denied one of lifes greatest pleasurestheenjoyment of food and drink of their choice in a pleasantsocial environment. (Burger et al.)

Defining the Risk

What puts our aging population at risk for dehydration? Anumber of factors come into play:

body mass

thirds of nursing home residents, per research by Gasper)

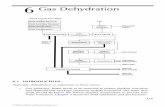

Dehydration and urinary tract infections are all-too-

common problems in long-term care. This article defines

signs and symptoms of dehydration, and discusses a

study at one facility that tried a supplement to keep

residents hydrated and reduce UTIs.

(Continued on page 32)

Dehydration is a form of malnutrition involving lifes most fundamental nutrient:water. Dehydration is defined asand often signaled bya sudden loss of 3 percent or more of body

weight. (Weinberg et al.)

Warren and colleagues define dehydration as an imbal-ance between intake and loss of fluid and the accompany-ing sodium status. They note that we tend to focus onfluid volume depletion because sodium status is not alwaysmeasured.

Dehydration may take one of several forms (Huffman):

Isotonic: balanced depletion of water and sodium,often seen with refusal of oral intake or as a result ofdiarrhea or vomiting

Hypertonic: water losses are greater than sodiumlosses, often seen with fever

Hypotonic: proportionately greater sodium loss thanwater loss, as may occur with overuse of diuretics

In long-term care, the facts are alarming:

Medicare hospitalizations. (Warren et al.)

die within 30 days. (Warren et al.)

six times more likely to be hospitalized for dehydrationthan those aged 65 to 69. (Warren et al.)

-

8/9/2019 Combating Dehydration in Nursing Homes

4/6

DIETARY MANAGER32

drink fluids

to concentrate urine

heat, fever, vomiting, or diarrhea (Garcia)

-ing fluid intake (prevalent among 39 percent of nursinghome residents, per research by Gasper)

A common standard for fluid intake is 30 ml/kg of bodyweight, with a minimum of 1500 ml per day. Another stan-

dard (Gasper) uses 100 ml/kg for the first 10 kg; then 50ml/kg for the next 10 kg; then 15 ml/kg for the remainder.

A study of 40 nursing home residents by Kayser-Jones andcolleagues identified an average actual intake of 847 ml/day. With dehydration comes the heightened risks of UTI,pneumonia, decubiti, disorientation, and electrolyte imbal-ance. (Chidester and Spangler)

Recommended strategies and solutions to dehydration in-clude assistance with meals and beverages, adequate staff-ing and staff training, beverages between meals, and hy-dration carts. (Garcia)

Signs and Symptoms of Dehydration

Clinical indicators of dehydration include the following:

Among the elderly, however, risk may be compounded bythe fact that dehydration is not always easy to detect. Ac-cording to Huffman, Classic signs of dehydration may beabsent or at least obscure. She suggests orthostatic bloodpressure or pulse measurement as better indicators.

A Hydration Trial

At Fountain Inn Nursing Home (Fountain Inn, SC), dehydra-tion is a sentinel event in our quality assurance program,and has been a target for quality improvement. Our careteam decided to augment industry best practices with aregimen built around an oral hydration formula.

Given the hydration risk factors outlined above, we believeits not enough to just hand a resident a glass of water andhope that succeeds. In addition, we find that popular caf-feinated beverages, such as coffee or tea, are often coun-ter-productive to hydration objectives because they causeadditional fluid loss. Furthermore, for individuals withdiabetes, we want to avoid beverages with simple sugar,

which could cause hyperglycemia, polyuria, and electro-lyte imbalance. A third consideration is the osmolality offluid supplements offered. In some individuals, a high-os-molar drink may trigger diarrhea, compoundingratherthan improvingthe problem of dehydration.

Most importantly, supplemental electrolytes are easilyoverlooked in nursing home hydration programs. Given theimportance of maintaining adequate sodium intake along

with fluid, we were interested in determining whether a

supplement of electrolytes as well as fluid could help pre-vent dehydration.

In April 2008, we began a trial of a lemon-flavored pow-dered drink mix supplement formulated for the fluid andelectrolyte needs of seniors*. We selected 10 residentsbased on the following criteria:

FeatureArticle (Continued)

We found that popular

caffeinated beverages, such

as coffee or tea, are often

counter-productive to hydration

objectives because they cause

additional fluid loss.

*GeriAide: 40 mg sodium, 20 mg potassium, 0 mg phosphorous per 4

oz serving; provided by Medtrition, Inc.

-

8/9/2019 Combating Dehydration in Nursing Homes

5/6

-

8/9/2019 Combating Dehydration in Nursing Homes

6/6

DIETARY MANAGER34

References

Burger, Sarah Greene, J. Kayser-Jones, and J. Prince Bell. Malnutrition and dehydration in nursing homes: key issues in prevention and treatment. National Citizens

Coalition for Nursing Home Reform 2000.

Chidester, JC and AA Spangler. Fluid intake in the institutionalized elderly. J Amer Dietetic Assn 97 (1997): 23

Gasper, PM. Water intake of nursing home residents. J Gerontol Nurs 1999 25 (4), 23-9.

Grabowski DC, OMalley J, Barhydt, N. The Costs and Potential Savings Associated With Nursing Home Hospitalizations. Health Affairs. 2007; 26 (6): 1753-1761.

Huffman, GB. Evaluation and management of dehydration in the elderly. American Family Physician, April 1996.

Kayser-Jones et al. Factors contributing to dehydration in nursing homes. J Am Geriatrics Society 1999. 47 (10): 1187.

Mentes, JC. Hydration management. Nursing standard of practice protocol. Evidence-based content. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, 2008.

National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & K idney Diseases. Overcoming bladder disease, 2002.

Warren, JL et al. The burden and outcomes associated with dehydration among US elderly. American Journal of Public Health, 84 (8), 1994.

Weinberg, AD and KL Minaker. Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Assn. Dehydration: evaluation and management in older adults. JAMA 1995. 274:19:

1552.

The nations healthcare costs could be

reduced dramatically through proactive

management of dehydration and other

factors in nursing homes.

Lisa Stewar t, CDM, CFPP is a Certified Dietary Manager at Fountain Inn Nursing Home in Fountain Inn, SC; Helga Longino, RN, is Director of Nursing; Diane

Burton, RN, is Assistant Director of Nursing and Infection Control Specialist; and Angie Corder, RD, is a Consultant Dietitian at Fountain Inn.

DM

FeatureArticle (Continued)

Costs of Dehydration and UTIs

The annual cost of UTIs in the US is $1 billion (Nation-al Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases).Grabowski and colleagues examined hospital admissionsfor nursing home residents in the state of New York and

concluded that the nations healthcare costs could be re-duced dramatically through proactive management of de-hydration and other factors in nursing homes. Specifically,they noted that:

hospitals in New York (2004) were $972 million.

New York costs $1.24 billion.

-tions leading to hospitalization, with a cost of $89.1million for New York alone during the study period.

-ing for healthcare costs of $200.9 mill ion for New Yorkalone during the study period.

dehydration is increasing.

A Proactive Approach

We need to recognize that many nursing home residentsare at risk for dehydration, and that simply offering bev-erages is not enough to prevent any unnecessary illness,achieve quality assurance objectives, contain healthcarecosts, and ensure the highest possible quality of life for

each individual. Our findings at Fountain Inn suggest thatit is effective to provide a fluid and electrolyte supplementin tandem, directly with meals to improve resident well-ness. Hydration management cannot be a passive endeav-or, and it requires a concerted, consistent effort from allhealthcare team members.