Clasissicism - Webster Article

-

Upload

sander-kintaert -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of Clasissicism - Webster Article

-

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

1/20

Between Enlightenment and Romanticism in Music History:"First Viennese Modernism" anthe Delayed Nineteenth CenturyAuthor(s): James WebsterSource: 19th-Century Music, Vol. 25, No. 2-3 (Fall/Spring 2001-02), pp. 108-126Published by: University of California PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ncm.2001.25.2-3.108.

Accessed: 20/03/2013 04:19

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at.http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range o

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new for

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

University of California Pressis collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to 19th-

Century Music

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucalhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ncm.2001.25.2-3.108?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ncm.2001.25.2-3.108?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucal -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

2/20

108

19THENTURYMUSIC

19th-Century Music, XXV/23, pp. 108126. ISSN: 0148-2076. 2002 by The Regents of the University ofCalifornia. All rights reserved. Send requests for permission to reprint to: Rights and Permissions, University

of California Press, Journals Division, 2000 Center St., Ste. 303, Berkeley, CA 94704-1223.

JAMES WEBSTER

At the beginning of the twenty-rst century,the traditional periodization of European mu-sic between 1700 and 1975late Baroque; Clas-sical; Romantic; modernseems increasinglyproblematic. Although my arguments againstthe idealizing concept of Classical Style have(I believe) contributed to a consensus on theneed for rethinking the years around 1800, thereis as yet no agreement on a music-historio-graphical alternative. My own suggestion alongthese lines is First Viennese Modernism, a

concept that I nd productive regarding notonly the music of the later eighteenth centurybut that of the early nineteenth as well.1

To give the argument in brief: althoughViennese music was decisive for the history ofthe art during the last half of the eighteenthcentury and the rst quarter of the nineteenth,this was for reasons other than those usuallyadduced under the banner of classicism. Itwas not typical of the European continent as awhole, nor was the culture that sustained it.But it wasmodern, in every sense. Moreover, itplayed a crucial role in the profound intellec-tual-cultural shift from Enlightenment to Ro-manticism, a shift that resonated with the evenbroader historical change from the ancien

rgime to postrevolutionary, industrialized,

Between Enlightenment and Romanticism

in Music History: First Viennese

Modernism and the Delayed

Nineteenth Century

An earlier, more narrowly focused treatment of this topicwas delivered at a conference in Vienna on Viennese Clas-sicism, November 2000; it will appear as Die Erste WienerModerne als historiographische Alternative zur WienerKlassik, in Der Begriff der Wiener Klassik in der Musik,ed. Gernot Gruber (in press). A version resembling thepresent one was delivered at Harvard University in May2001; I thank Reinhold Brinkmann for the invitation andfor constructive suggestions. For suggestions regarding thehistoriographical literature (and more), I thank Karol Berger,James Hepokoski, and Michael P. Steinberg.

1James Webster, Haydns Farewell Symphony and theIdea of Classical Style(Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress, 1991), pp. 33566; for First Viennese Modernism,see pp. 35657, 37273.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

3/20

109

JWVM

bourgeois society. In Vienna, the most impor-tant decades of this development comprisednot only the prerevolutionary 1780s of Haydnand Mozart and Beethovens heroic phase of180312 (both privileged by music historians),but also the postrevolutionary, if conservative1790s (which have received far less attention).

These years between Enlightenment and Ro-manticism were no mere transition, however;they constituted an equally weighty phase, onthe same historical-structural level, as thosethat preceded and followed it. Concomitantly,Romanticism as such did not become predomi-nant in music until 1815, in Viennese music(except for the Lied) perhaps not even until1828/30. For both reasons, it makes sense toregard the beginning of the music-historicalnineteenth century as having been delayed,until around 1815 or 1830.

Periods, Periodizations, andMultivalent History

All the temporal spans mentioned above areexamples of (music-)historical periods. Few gen-eral historians have systematically discussedissues of periods and periodizations during thelast quarter-century. Although on one level thisreluctance simply reects the ever-increasingspecialization of the discipline, on historio-graphical grounds it would seem to have beenoverdetermined: by the apparently simplistic,over-generalizing character of most period des-

ignations; by a desire for objectivity in histori-cal writing following World War II, signaled inthis case by the nominalistic stance that periodterms and concepts are mere labels of conve-nience, lacking explanatory value, on the onehand, and avoiding ideological overtones, onthe other; and by a preference for thickly tex-tured history and cultural studies, in opposi-tion to the traditional histories of events.2In

this shying away from periodistic thinking, theundeniable attractions of metahistory havedoubtless also played a role, particularly as itintersects with the antifoundationalist intel-lectual climate of postmodernism.3

This marginalization of period concepts, how-ever, is based on an illusion or self-deception.

Notwithstanding the ostensible sophisticationof the arguments raised against them (for ex-ample, that grand narratives in history arearbitrary, partial, self-replicating, and often ten-dentious), they remain central, even in the workof those who might wish to deny this. The factthat many histories instantiate older or morefundamental worldviews, literary genres, andrhetorical tropes (a position associated espe-cially with Hayden White)4does not affect theirorganizational and rhetorical dependence onstage narratives, which is to say on periodsand periodizations.5In this respect, period con-

cepts are analogous to plot in literary theory:plot was marginalized by the New Critics andstill is in many quarters, yet it remains themost important aspect of ction and drama(including opera).6The essentiality of both plotand periodization rests in their common status

2From the vast literature I cite Reinhart Koselleck, Fu-tures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, trans.Keith Tribe (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985); PhilippeCarrard, Poetics of the New History: French HistoricalDiscourse from Braudel to Chartier (Baltimore: JohnHopkins University Press, 1992); William A. Green, His-tory, Historians, and the Dynamics of Change (Westport,Conn.: Praeger, 1993), chaps. 2, 9; Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr.,Beyond the Great Story: History as Text and Discourse(Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1995).

3For example, although Michel Foucault erects strongly,indeed schematically, differentiated periods (based on hisdiscourse-generating epistemes), he attempts not to or-ganize them into a periodization. See The Order of Things:An Archaeology of the Human Sciences,trans. anon. (NewYork: Vintage Books, 1970).4Hayden White, Tropics of Discourse (Baltimore: JohnHopkins University Press, 1978), esp. the intro. and chaps.23; idem, The Content of Form: Narrative Discourse andHistorical Representation (Baltimore: John Hopkins Uni-versity Press, 1987). A striking music-historical exampleis Adolf Sandbergers account of Haydns compositionaldevelopment, based (unconsciously) on a fairy tale or questarchetype; see Webster, Haydns Farewell Symphony,pp. 34147.5Carrard, Poetics of the New History,chap. 2; Berkhofer,Beyond the Great Story,chap. 5.6The most useful introduction to plot and narrative inliteratureand not only because of its relative accessibil-ityremains Peter Brooks, Reading for the Plot: Designand Intention in Narrative (New York: A. Knopf, 1984).Regarding plot in opera, see Carolyn Abbates post-modernistically inspired dismissal in Unsung Voices: Op-era and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth Century(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), pp. 511,and the rehabilitation in Jessica Waldoff and James Webster,Operatic Plotting in Le nozze di Figaro, in WolfgangAmad Mozart: Essays on His Life and His Music, ed.Stanley Sadie (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), pp. 25095, 12.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

4/20

110

19THENTURYMUSIC

asnarrativethe primary means by which weorganize all types of temporal experience, in-cluding history.7 And in the long run evenmetahistory is likely to be a less effective curefor bad periodizing than a robustly revisionistperiodization, one that acknowledges, ratherthan represses, the need to organize temporally

our understanding of the past. For one cannotthink about, still less investigate, the cease-less, innitely complex ow of historical eventswithout segmenting them into time spans.

A historical period is a construction. Periodsdont just happen; still less are they given ob-jectively in the historical record, as GuidoAdler, the founder of style analysis in musicol-ogy, believed.8On the contrary, a periodizationis not so much true or false, as areading,a wayof making sense of complex data; periodizationsserve the needs and desires of those who make

and use them. The moment we inquire into thenature or limits of our chosen time spans, wealmost inevitably construe them as having beendetermined, or at least strongly characterized,by certain classes of phenomena, such that theycan be understood as effectively unied.9Thisis so whoever we are, and whether we con-ceive our historical intentions as objectiveor interest-driven.

In a late, untranslated article, Carl Dahlhausoffered a sustained meditation on music-his-torical periods; his conclusion reads as follows:

The analysis of the methodological structure of mu-sic-historical period concepts . . . implies that aperiod concept

1. belongs primarily but not exclusively to mu-sic history [as opposed to the present of the

time interval in question], as reconstructed inretrospect by the historian;

2. represents a coherence of signicance and func-tionality [einen Sinn- und Funktionszusam-menhang], which is interpretable as an idealtype in Max Webers sense;

3. can be described as a network of relationshipswithin which, without its having a center, onecan move directly or indirectly from any givenpoint to any other;

4. is a congeries [Konnex] of features, of whichthe foundational relations [Fundierungsverhlt-nisse] are indeterminate as a matter of prin-ciple, but can be determined in a given case[kasuell];

5. entails the expectationin anticipation of aunied coherence [geschlossener Zusammen-hang]that, through patient efforts of empiri-

cal research into detail, at least a portion ofthe constructed or reconstructed coherence ofsignicance and functionality [cf. point 2] canbe gradually tracked down in the documentsthat pertain to the past. Between the idealtype, which as an assumption-in-advance[Vorausnahme] remains to be realized, and thehistorical document, which as a (possibly mis-leading) testimony to reality [Wirklichkeit] re-quires interpretation, the outlines of that whichis unknown, past reality [die vergangeneRealitt], wie es eigentlich gewesen, gradu-ally emerge.10

Thus Dahlhaus agrees that (music-)historicalperiods are constructions, indeed retrospectivereconstructions, which we interpret as concep-tually coherent even though they will scarcelyhave seemed so in their own time. Webers

10Carl Dahlhaus, Epochen und Epochenbewusstsein inder Musikgeschichte, in Epochenschwelle undEpochenbewusstsein, ed. Reinhart Herzog and ReinhartKoselleck (Munich: W. Fink, 1987), p. 96; rpt. in Dahlhaus,Gesammelte Schriften,ed. Hermann Danuser et al., vol. I(Laaber: Laaber, 2000), pp. 30319. Wie es eigentlichgewesen (as it actually was) is the famous characteriza-tion of the goal of historical understanding propounded bythe nineteenth-century German historian Leopold Ranke.Dahlhauss primary example in this article is VienneseClassicism; for a similar discussion oriented toward thenineteenth century, see Foundations of Music History,trans. J. B. Robinson (Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress, 1983), pp. 14144.

7Hans Robert Jauss, Toward an Aesthetic of Reception,trans. Timothy Bahti (Minneapolis: University of Minne-sota Press, 1982), pp. 5362; Paul Ricoeur, Time and Nar-rative, 3 vols., trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and DavidPellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 198488),vol. I, pt. 2; vol. III, pt. 4, section 2; Berkhofer, Beyond theGreat Story,chap. 2.8Guido Adler, Handbuch der Musikgeschichte,2 vols. (2ndedn. Berlin: Keller, 192930), I, 69.9Fritz Schalk, ber Epoche und Historie, inStudien zurPeriodisierung und zum Epochenbegriff [Mainz:] Akademieder Wissenschaften und der Literatur: Abhandlungen dergeistes- und sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse, 1972, no. 4,pp. 1238.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

5/20

111

JWVM

ideal type (point 2), with its characteristiccombination of empirical research and general-izing speculation, was a central aspect ofDahlhauss historiography;11in other contexts,more plausibly in my view, he uses the conceptcoherence of signicance and functionalityto characterize individual artworks.12Point 3,

with its image of a network without a cen-ter, relates interestingly to his preferred meta-phors for thematicist analysis, specicallyregarding subthematicism in late-styleBeethoven and Wagners leitmotivic tech-niques.13 Point 4 means that, as a generaliza-tion applying to all periods, no assertion can bemade to the effect that one domain (aestheticideas, compositional practice, musical institu-tions, economic and social circumstances, andso forth) is foundational with respect to others,but that nevertheless such a determination canoften be made in a given individual case (as we

will see, Dahlhaus often takes major water-sheds of political-military history as founda-tional for music history). Point 5, nally,amounts to his thesis: the historical truth ofa period emerges, if at all, through dialoguebetween empirical investigation and specula-tive reection: a historiographical version ofthe hermeneutic circle.14

Recent North American musicology has pro-duced little that can be placed by the side ofDahlhauss thoughts on period construction.15

To be sure, our survey texts still tend to beorganized around the traditional style periods,but they devote little critical attention to theproblematics or historiography of such divi-sions. Indeed the inertia (or reication) of thestyle periods themselves, which have changedlittle since Adler, doubtless inhibits such

questionings. By contrast, in Europe bothJacques Handschins Musikgeschichte imberblickof 1948 and the majority of the rel-evant volumes in Dahlhauss more recent NeuesHandbuch der Musikwissenschaftproceed onthe ostensibly objective (or nominalistic) basisof simply following the centuries as determinedby the calendar.16Handschins skeptical com-ments on the traditional style periods have inmany ways never been surpassed.17Dahlhaussorganization stands in conscious opposition tothat in Ernst Bckens predecessor series, whoseallegiance to the style periods is evident from

the titles alone, for example, Heinrich BesselersDie Musik des Mitteralters und der Renais-sance and Bckens own Die Musik desRokokos und der Klassik.18In place of the styleperiods, Dahlhaus emphasizes the social andorganizational systems that shaped musicalproduction and reception, as does LorenzoBianconi in his inuential Music in the Seven-teenth Century.19 (One might speculate that

11Philip Gossett, Carl Dahlhaus and the Ideal Type,this journal 13 (1989), 4956. Although Dahlhauss appli-cation of the concept sometimes involved special plead-ingsee Gossett, pp.5256its value as a general approachto many issues of history and analysis is not thereby com-promised.12For example, Dahlhaus, Gleichzeitigkeit desUngleichzeitigen, Musica 41 (1987), 30710 (a study towhich I shall return); here, p. 310, col. 1.13Regarding Beethovenwe may ignore Wagner in this con-textsee Webster, Dahlhauss Beethoven and the Endsof Analysis, Beethoven Forum2 (1993), 21216, 22224.14See Beitrge zur musikalischen Hermeneutik, ed.Dahlhaus (Regensburg: G. Bosse, 1975), esp. his Fragmentezur musikalischen Hermeneutik, pp. 15972; trans. KarenPainter, Fragments of a Musical Hermeneutics, CurrentMusicology50 (1992), 520. For an insightful overview ofDahlhauss historiography, see James Hepokoski, TheDahlhaus Project and Its Extra-musicological Sources, thisjournal 14 (1991), 22146.15A useful (albeit resolutely Germanic) survey is ThomasHochradner, Probleme der Periodisierung von Musikge-schichte,Acta Musicologica67 (1995), 5570.

16Jacques Handschin, Musikgeschichte im berblick(Lucerne: Rber, 1948); Die Musik des 17. Jahrhunderts,ed. Werner Braun (Wiesbaden: Athenaion, 1981); Die Musikdes 18. Jahrhunderts,ed. Dahlhaus (Laaber: Laaber, 1985);Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music, trans. J. BradfordRobinson (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of Cali-fornia Press, 1989). For a (problematical) translation of therst section of Dahlhauss superb introduction to the eigh-teenth-century volume, see The Eighteenth Century as aMusic-Historical Epoch, trans. Ernest Harriss, College Mu-sic Symposium26 (1986), 16; for an insightful commen-tary on the volume, see Eugene K. Wolf, On the Historyand Historiography of Eighteenth-Century Music: Reec-tions on Dahlhauss Die Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts, Jour-nal of Musicological Research10 (1991), 23955.17Handschin, Musikgeschichte im berblick, pp. 1527,27376 (the latter passage is the introduction to his single[!] chapter entitled The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Cen-turies).18Heinrich Besseler, Die Musik des Mittelalters und derRenaissance (Postdam: Athenaion, 1931); Ernst Bcken,Die Musik des Rokokos und der Klassik (Potsdam:Athenaion, 1928).19Lorenzo Bianconi, Music in the Seventeenth Century,trans. David Bryant (Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress, 1987).

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

6/20

112

19THENTURYMUSIC

the correlation between Dahlhauss andBianconis organization by centuries rather thanstyle periods, and their increased attention toinstitutional at the expense of compositionalhistory, is not coincidental.)

The course of a given period in any domainwhether the output of an individual artist, an

entire artistic repertory, or even the fate ofnations and empiresis usually understood interms of the organic narrative: growthmatu-ritydecay. In particular, because the conditionof maturity appears at the midpoint or cli-max, it is almost predestined to function as thefoundational metaphor for historical investiga-tions of style.20The danger is that the idealizingtendencies of organicist thinking induce us tothink of a style period in terms of any discover-able unity within it (Dahlhauss unied co-herence)as well as whatever is conceptuallymost distinct from the preceding and following

periods. A telling indication of this orientationis the tendency to graph the temporal courseof a period by means of a sine-curve or bell-shaped curve, which begins, so to speak, at 0 onthe x-axis, mounts smoothly upwards to a highpoint, more or less in the middle (occasionallytwo-thirds of the way along, corresponding tothe golden section and to the preferred place-ment of dramatic climaxes), and descends intoinsignicance (illustrations are given below).The high point represents the conceptual unityof the period (everything foreign is minimized);conversely the zero-point at the beginningand end signies the effective absence of thosecharacteristics, compared to others proper tothe preceding and following periods. Hence evenan ostensibly nominalistic period constructionis everything other than objective or value-free;the organic worldview is as value-laden as any-thing in our culture, perhaps especially when itfunctions covertly.21 This applies particularlyto the centuries: just as, during the post-Reformation transition to the modern world,the traditional sense of a century as a mere

marker of chronology gradually turned into asignifying substantive (the French equivalentto the Enlightenment was, and is, le sicledes lumires),22so Dahlhauss ideal of a music-historical century as a neutral site where wemay hope to discover wie es eigentlich gewesenis unlikely to be realized in practice.

Notwithstanding the sophistication of Dahl-hauss account of period construction, like mostrecent historians he says little about the rela-tion between a given historical period and oth-ers. And yet the attempt to understand a givenperiod in isolation is the historiographicalequivalent of solipsism: a given period makessense only in terms of its relations to its tem-poral neighbors, as an element in a periodizationor multistage narrative. This is true eventhough periodizations are more value-laden thansingle periods; many depend on a small reper-

tory of ideologically charged worldviews.23Ofthese, the most important are the originary,inwhich phenomena are seen as having enjoyedtheir perfect or ideal manifestation in their ear-liest stage, followed by decline; the organic(just described); and the teleological,in whichphenomena are interpreted in terms of the goalor end to which they are thought to lead. Obvi-ously, each worldview valorizes one of the threepossible positions within a ternary periodi-zation: beginning, middle, end.

Contiguous periods, in both verbal descrip-tions and visual representations, tend to be rep-resented as overlapping, rather than merely jux-taposed. Even with respect to generally acceptedperiod divisions, for example Renaissance toBaroque, every teacher of music history ex-plains that the latter did not commence pre-cisely on 1 January 1600, but arose via a com-plex, decades-long process of change. Theseoverlappings doubtless relate to the most per-vasive organic periodizations we know, thestages of a human life and the rhythm of theseasons, in which the boundaries cannot beprecisely determined: no single year marks the

20Dahlhaus, Foundations of Music History,pp. 1318.21On covert values in musicology, see Janet M. Levy,Covert and Casual Values in Recent Writings about Mu-sic, Journal of Musicology5 (1987), 327; for organicismin particular, Ruth A. Solie, The Living Work: Organicismand Musical Analysis, this journal 4 (1980), 14756.

22Koselleck, Futures Past,pp. 24647.23For a systematic survey of periodizations, see Webster,The Concept of Beethovens Early Period in the Contextof Periodizations in General, Beethoven Forum3 (1994),127.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

7/20

113

JWVM

change from maturity to old age, no single day(despite the solstice) the onset of winter. Al-though in the imagination (not in reality) win-ter is a zero-state of dormancy, it is not a merepoint in time but a period in its own right,indeed a teleologically charged one, pointingtoward the renewal of spring. This orientation

manifests itself verbally in the ubiquitous meta-phors of decay and rebirth to describe suchchanges, whether for individual uvresor en-tire style periods. Thus for Maynard Solomon,Beethovens transitions from one period to an-other were marked by crises, in which theprevailing style either reaches its outer limitsof development or undergoes a process of disin-tegration or exhaustion, while a new style,which will predominate in the succeeding pe-riod, may begin to emerge.24For Dahlhaus, theyears 17891814 constitute an overtly transi-tional pre-Romantic period.25Often it is pre-

cisely the metaphorical seeds produced dur-ing the maturity of the preceding period thatare thought to generate the new periods growth.

All this may explain why we often construethe transitions between periods as subsidiaryperiods in their own right. Two familiar ex-amples in music history (both borrowed fromart history) are mannerism as linking Re-naissance and Baroque, and the (now pass)Rococo as bridging Baroque and Classical.Whether such linking phases are best consid-ered transitions or small-scale, independent pe-riods cannot be generalized about, but can bedetermined only by each individual observer ineach individual case, in part on the basis of pre-rational notions as to whether or not all peri-ods must have approximately the same lengthor weight. Examples from around 1800 willbe given below.

A nal methodological issue involves the no-tion that, within a given area or culture, eventsin the various domains of human activity

politics, economics, mentalits, the arts, andso on; and similarly within the several artsreect a single Zeitgeist; or, less controver-sially, that they participate together in a struc-tural history, developing in temporally con-gruent patterns that can be related to a coher-ent general tendency, for example the rise of

modernism around 1900.26

By and large, Zeit-geist thinking in its cruder forms is now re-jected by comparative historians, in favor ofwhat Eugene K. Wolf has engagingly calledcontrapuntal history; one might also suggestmultivalent, owing to the analogy with aleading current paradigm of musical analysis.27

The thesis is simply that events in differentdomains do not necessarily run parallel: theymay differ in character or value at a givenplace and time; they may develop differentially,regarding both the dates of their beginning,middle, and end stages and their rates of devel-

opment; and these differences apply both withina given region and across different ones.28Thewatersheds between periods can occur at dif-ferent times, whether in different domains inthe same geographical area (the Renaissance inmusic both began and ended later than in thevisual arts and literatureand this is not aproblem, but an opportunity), or in a singledomain in different areas (the musical Baroquepersisted longer in Protestant Germany and theHapsburg lands than in France or Italy). Ofcourse, one can argue that even a single do-main in a single areasay, music in Vienna17801815was subject to heterogeneous oreven opposing forces and values, such that todene it as the x period privileges certain

24Maynard Solomon, The Creative Periods of Beethoven(1973), rpt. in his Beethoven Essays (Cambridge, Mass.:Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 122.25Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music,pp. 1920, 5556,and Die Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts, pp. 6268, 33545.Dahlhaus himself (p. 63) confesses his embarrassment withthe Verlegenheitsterminus Vorromantik.

26Dahlhaus, Foundations of Music History, chap. 9. Foraccessible critiques of Zeitgeistthinking, see William We-ber, Toward a Dialogue Between Historians and Musi-cologists, Musica e storia 1 (1993), 721 (here, 1518);Beyond Zeitgeist: Recent Work in Music History, Jour-nal of Modern History66 (1994), 32145.27For contrapuntal history, see Wolf, The EighteenthCentury, p. 240. The term multivalence was coined byHarold S. Powers in a (still) unpublished study of VerdisOtello,presented at a Verdi-Wagner conference at CornellUniversity in 1984. For discussion and use, see Webster,The Analysis of Mozarts Arias, in Mozart Studies,ed.Cliff Eisen (London: Clarendon Press, 1991), pp. 10199,and The Form of the Finale of Beethovens Ninth Sym-phony, Beethoven Forum1 (1992), 2562.28Jauss, Toward an Aesthetic of Reception,pp. 3639.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

8/20

114

19THENTURYMUSIC

characteristics or criteria and thereby under-states its complexity or perpetuates a covertagenda. On the other hand, in this context thecelebration of multifariousness eventuallyreaches a point of diminishing returns: even ifthe understanding of historical phenomena thatperiods offer is always partial and self-inter-

ested, the only alternative isno understand-ing at all.As a consequence of historical multivalence

(to come to this obvious point at last), a histori-cal century need not coincide with the calen-dar. The nineteenth can be construed, not ashaving lasted precisely from 1800 to 1900 but,depending on which characteristics are takenas dening, as having begun before or after1800, or ended before or after 1900, and henceas having been, as a whole, shorter or longerthan 100 years. Many historians have writtenof the long nineteenth century, beginning in

1789 or 1782 (or even around 1750) 29and last-ing until the outbreak of the First World War(this latter point is obvious, especially in thearts). But if this is true of (European) history ingeneral, it is even truer of a single domainwithin it, such as European music; for example,in Dahlhauss parsing of music history the sev-enteenth century lasted from ca. 1600 to ca.1720, the eighteenth from ca. 1720 to 1814,and the nineteenth, oddly (or interestingly), pre-cisely 100 years, from 1814 to 1914.

In recent German historiography, nally,much has been made of the contemporaneityof the non-contemporaneous (Gleichzeitigkeitdes Ungleichzeitigen), and its converse.30 Asimple example in our eld is the commonnotion that an artwork is ahead of its time(which admittedly makes less sense the longer

one ponders it). As a generalized methodologyit encourages historians to consider events fromdifferent times and domains as belonging to-gether, notionally and possibly even essen-tially, and conversely. Although this conceptis clearly usefulthere are real advantages (aswell as disadvantages) to treating the musical

Renaissance together with those in art and lit-erature, despite its later dateit tends to pre-serve Zeitgeist thinking after all, because itstill privileges the notion of a deep or realconnectedness across domains and decades andtherefore often ignores the variety and messi-ness of history wie es eigentlich gewesen. Arelevant example is Dahlhauss astonishing as-sertion that the revolutionary stance of theEroica [Symphony] has never been denied: inthe inner chronology of world history, the workcries out to be backdated to 1789.31 This isscarcely more than the vulgar Marxism that

elsewhere he took pains to disparage: it placesthe Eroicain the position of a mere artisticevent on the ephemeral superstructure thatoverlay the real, material-political base rep-resented by the French Revolution. (For musichistorians, why shouldnt the latter equally wellcry out to be foredated to 1803?) Whatcries out for skepticismnotwithstandingBeethovens having toyed with the titleBonaparteis the uncritical assumption ofan inner chronology of world history: of anecessary connection between a political andsocial revolution in France beginning in 1789,and a symphony composed and premiered inthe very unrevolutionary Vienna of 180304.

As this example suggests, notwithstandinghis consistent problematizations of period con-struction,32 Dahlhaus often ends up reifyingtraditional watersheds of political-military his-tory. Thus his division-points within eigh-teenth-century music history fall at 1745, 1763,and 1789, while his nineteenth century tscomfortably within the years 1814 and 1914

31Dahlhaus, Ludwig van Beethoven: Approaches to HisMusic, trans. Mary Whittall (Oxford: Clarendon Press,1991), p. 16; admittedly, he attempts to relativize thissalvo in Die Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts,pp. 33639.32Dahlhaus, Die Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts,pp. 18, 7172, 13947, 22731, 33538 (plus a generalized problematiz-ing paragraph on p. 24); Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-CenturyMusic,pp. 18, 5457, 11417, 19295, 26365, 33039.

29For the year 1789, see E. J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Revo-lution, 17891848(Cleveland: World, 1962), p. 1; for 1782,see George Macauley Trevelyan, British History in theNineteenth Century (17821901) (London: Longmans,Green, 1922), p. viii; and for 1750, Hobsbawm, Industryand Empire: An Economic History of Britain since 1750(London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1968), p. 1. Cf. DavidBlackbourn, The Long Nineteenth Century: A History ofGermany 17801918(New York: Oxford University Press,1998).30Ernst Bloch, Nonsynchronism and the Obligation to ItsDialectics, trans. Mark Ritter, New German Critique11(1977), 2238; Dahlhaus, Gleichzeitigkeit desUngleichzeitigen, Musica 41 (1987), 30710; Koselleck,Futures Past,pp. 92105.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

9/20

115

JWVM

years whose signicance derives in the mainfrom political history; this premise encour-ages us to divide the century into subperiods orevolutionary stages bounded by dates such as1830 and 1848 which are regarded as turningpoints in political history.33Even the bound-ary between the eighteenth and nineteenth cen-

turies is placed at 1814 (which I would gloss as181415), marked by the collapse of theFrench empire and the Congress of Vienna. Therelative autonomy of music history, of whichin other contexts Dahlhaus made so much,34ishonored mainly in the breach.

First Viennese Modernism

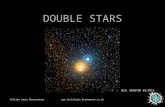

In thinking anew about the history of musicaround 1800, the rst step must be to jettisonthe traditional notion regarding the eighteenthcentury, namely that it comprised the Baroque

and Classical periods, with the former lastinguntil roughly the middle of the century, thelatter then supplanting it and being supplantedin turn by the Romantic at the beginning of thenineteenth (see g. 1a). As is true of watershedsgenerally, in this construction both divides areoften bridged by transitional phases (g. 1b):Rococo or Pre-Classical in the one case,Beethoven in the other. Today this notion seemsinsupportable, if only because it derived prima-rily from a nineteenth-century Germanichypostatization of Bach as a teleological culmi-nationin ignorance of the chronology of hischurch cantatas, and without regard for theatypicality of his music and his relative isola-tion, or the many progressive aspects of hismusical orientation and style, during the sec-ond quarter of the eighteenth century.35

Indeed, there are good reasons to maintainthat, with respect to Europe as a whole, notonly did the musical Baroque not last beyond

1720 or so, but that the years roughly from1720 to 1780 constituted a period in their ownright (g. 1c). Admittedly, there is as yet noagreement on what to name it; if one did notfear that brevity equated to insignicance, onecould call it the short eighteenth century inmusic history. It was dominated intellectually

by the Enlightenment, culturally and institu-tionally by the international system of courtopera in Italian, and aesthetically and stylisti-cally by two ideals: neo-Classicism (in the senseof an intended renaissance of the values andideals of Classical antiquity, as manifested, forexample, in tragdie lyrique,opera seria, andGluck) and thegalant,in a broad sense encom-passing not only easy listening and socialgrace, but Rousseaus ideal of melody speak-ing directly to the listener.36As of the 1760swas added the ideal of sensibility, as mani-fested, for example, in an entire subgenre of

opera buffa from Goldonis and Piccinnis Labuona gliuola (1760) to Figaroand beyond,37

and in the Empndsamkeit of C. P. E. Bachskeyboard works. Since a composite monikercovering all these aspects will not do, I suggestsimply Enlightenment/galant, notwithstand-ing the manifold historiographical problems as-sociated with the former concept and the factthat it was more a scientic-humanistic move-ment than an artistic one.38Furthermore, as isrequired of a meaningful period construction,

33Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music,pp. 1, 54.34For example, Dahlhaus, Foundations of Music History,chap. 8.35Stephen A. Crist, Beyond Bach-Centrism: Historio-graphic Perspectives on Johann Sebastian Bach and Seven-teenth-Century Music, College Music Symposium3334(199394), 5669. The original and still valuablerelativization of the traditional picture of Bach was RobertL. Marshall, Bach the Progressive: Observations on HisLater Works, Musical Quarterly62 (1976), 31357.

36In a characteristically complex argument, Dahlhaus con-cludes that even though the galant,as a primarily socialideal originating in the seventeenth century, is problem-atical when employed as a global characterization of themusical style of the mid-eighteenth, it is nevertheless de-fensible (Die Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts,pp. 24, 2432).Indeed eighteenth-century writers routinely used it as ageneral term for free styles; see Leonard G. Ratner, Clas-sic Music: Expression, Form, and Style (New York:Schirmer, 1980), pp. xv, 16; David A. Sheldon, The Con-ceptgalant in the Eighteenth Century, Journal of Musi-cological Research9 (198990), 89108.37Mary Hunter, Pamela: The Offspring of RichardsonsHeroine in Eighteenth-Century Opera, Mosaic18 (1985),6176; Stefano Castelvecchi, From Ninato Nina: Psycho-drama, Absorption and Sentiment in the 1780s, Cam-bridge Opera Journal 8 (1996), 91112; Waldoff, Senti-ment and Sensibility in La vera costanza, in Haydn Stud-ies,ed. W. Dean Sutcliffe (Cambridge: Cambridge Univer-sity Press, 1998), pp. 70119; Hunter, Rousseau, the Count-ess, and the Female Domain, in Mozart Studies,ed. CliffEisen, vol. II (London: Clarendon Press, 1997), pp. 126.38Weber, Toward a Dialogue, pp. 1314; Berkhofer, Be-yond the Great Story,pp. 22526.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

10/20

116

19THENTURYMUSIC

Baroque

a. Traditional style periods.

Classical Romantic

Baroque

b. Traditional style periods with overlapping transitional periods.

Classical

(late) Baroque

c. European-oriented (institutional history).

?

(late) Baroque

d. Viennese-oriented (modernism).

First Viennese Modernism

International Italian operaEnlightenment

Galant

e. Viennese-European double perspective.

Haydns sublimeMozart reception

Beethoven

f. Dahlhaus.

eighteenth century

Pre-Classical

g. Finscher.

Classical

Romantic

Romantic

Romantic

Romantic

nineteenth century

Romantic

~1750 ~1800

~1750 ~1800

~1780 ~1815

~1750 180930

~1780 180915

~1720 1814

1780 1800

RococoPre-Classical

(middle)Beethoven

International Italian OperaEnlightenment

Galant

~1720~1660

~1660

Trans.Turn 1

180915Turn 2

182730

mimesis mimesis expression expression

~1720

Figure 1: Some periodizations of eighteenth-century music.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

11/20

117

JWVM

in all these respects 172080 differed funda-mentally from both the preceding years (whichmay still count as the Baroque) and the follow-ing ones. Such distinguished (and different) au-thorities as Dahlhaus, Leonard G. Ratner, andDaniel Heartz have urged various aspects ofthis interpretation,39and on the whole it seems

persuasive to me.To revert to the years around 1800, however,this construction implies that a subsequentmusic-historical period began around 1780again, one that has no name. This suggestsrenewed attention to Friedrich Blumes notionof a single Classic-Romantic period stretch-ing all the way to 1900 or 1914,40except that inmy view it must be seen as having begun notaround 1750 but rather 1780. A long nineteenthcentury indeed! Notwithstanding Dahlhaussprovisional objection (which admittedly he him-self relativizes) that important new genres such

as the Lied and the characteristic piano piecestrike a fundamentally new tone after ca. 1815,41

the coherence of structural music historyduring the period 17801900 seems incontro-vertible: see the steady expansion of both bour-geois musical life and institutions and the canonof masterworks, as well as the strong continu-ities affecting many other genres, form- andmovement-types, multimovement cyclic pat-terns, tonality, thematically based logic, nar-rative paradigms, and so on.

The aesthetic continuities were equallystrong. Like Blume, Dahlhaus projects the eigh-teenth century forward into the nineteenth,albeit only up to 1814. In place of stylistic andgeneric continuities he adduces four aestheticones: acceptance of the organism model for

musical coherence; a belief in the originalitypostulate; the aesthetic of the sublime; andthe presence of historical consciousness re-garding past music.42This composite is a near-equivalent to Lydia Goehrs regulative work-concept, likewise seen as having originatedbetween 1780 and 1800.43 This concept (in

whichever guise) dominated musical aesthet-ics throughout the nineteenth century (and re-mained regulative in many respects duringmuch of the twentieth as well). Thus systemic,stylistic/generic, and aesthetic factors all sug-gest the cogency of a music-historical periodthat bridges 1800, rather than beginning then.

Although I agree with the thesis of large-scalecontinuities beginning around 1780 and lastingwell past 1800, my own construction focusesinstead on what I call First Viennese Modern-ism (referring to both style and period). By

this I understand the music of the Vienneserealmbut only that realmfrom 1740 or 1750until 1810/15 or 1827/30 (g. 1d). Admittedly,and corresponding to the preceding argument,within this period the phase beginning around1780 has a special status, to which I shall turnin due course.

The preconditions for Viennese musical mod-ernism began to emerge around 1740: politi-cally with the death of Charles VI and the ac-cession of Maria Theresa; musically with thedeaths of Caldara and Fux and the (at leastnotionally related) emergence of an indigenousgalantinstrumental music.44This division pointdoes not correspond with the general Europeanstyle change around 1720 or 1730; indeed itcorresponds to the otherwise discredited Ba-roque/Classical division around 1750. This isnot a problem; it is simply that Baroque stylesand institutions maintained themselves longerin the Hapsburg realm than in other regionsas stated, until 1740.

39Dahlhaus, Die Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts,pp. 38 (withthe variant -1789 rather than -1780 and with the ensuing[sub]-period problematically rubricked as pre-Romanti-cism [cf. above]); Ratner, Classic Music;Heartz, Classi-cal, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians,ed. Stanley Sadie (2nd edn. New York: Macmillan, 2001),vol. 5, pp. 92429.40In Blumes articles Klassik and Romantik in DieMusik in Geschichte und Gegenwart: Allgemeine Enzy-klopdie der Musik,ed. Blume (Kassel: Brenreiter, 194968); trans. M. D. Herter Norton as Classic and RomanticMusic: A Comprehensive Survey(New York: W. W. Norton,1970), where the thesis is stated in pointed form on pp.viiviii.41Dahlhaus, Die Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts,p. 65.

42Ibid., pp. 6263.43Lydia Goehr, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works:An Essay in the Philosophy of Music (Oxford: ClarendonPress, 1992).44This reading is also found in Heartz, Viennese School,pp. xviixviii, et passim, and in The New Grove Dictio-nary, 2nd edn., vol. 26, pp. 55455 (this section of theVienna article was written not by a musicologist but byDerek Beales, the distinguished biographer of Joseph II).

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

12/20

118

19THENTURYMUSIC

Depending on the criteria, this period can beseen as having extended to either ca. 180915or ca. 182730. The 180915 divide began withthe bombardment and occupation of Vienna bythe French in mid-May 1809 (and the pathos ofHaydns death two weeks later, which con-rmed the valedictory function of the famous

performance of the Creationthe preceding year).This defeat led to the collapse of the economicsystem and virulent ination; one of its effectswas the permanent decline of the noble patron-age system for music, which until then hadfunctioned unchallenged, concretized for us bythe rapid loss in real value of Beethovens so-called annuity of 1809.45 (For those who focuson Beethovens personal style, his adoption of aless heroic and more lyrical vein beginningaround 1809 ts well into this picture.46) Thisphase ended in 181415, years marked politi-cally by the Congress of Vienna and the conser-

vative stabilization thus brought about, insti-tutionally by the founding of what would be-come the Gesellschaft fr Musikfreunde, andmusically by Schuberts mature Lieder begin-ning with Erlknigand Gretchen am Spinnradeand Beethovens temporary retreat into silence.The importance of the latter is emphasized (forus) by his subsequent turn to a very differentlate style. The latter, however, was contem-poraneous with the triumph of Rossini; indeedby the 1820s Viennese musical life had begunto assume an entirely new character, leading tothe duality Beethoven vs. Rossini (Germanvs. Italian-French, symphony vs. opera, art asKultur vs. art in culture) that dominated thehistoriography of nineteenth-century musicfrom Kiesewetter to Dahlhaus.47The later po-tential ending-divide, 182730, is dened moresimply on the basis of the deaths of Beethovenand Schubert and Viennas eclipse as a centerof European composition, not only by Berlin

and Leipzig, but even more by Paris followingthe restoration of 1830, symbolized by the pre-miere of Berliozs Symphonie fantastique inthat year.

Although any of these details might be dis-puted, the notion of a Viennese musical periodlasting from roughly the middle of the eigh-

teenth century through the rst quarter of thenineteenth is unquestionably tenable. Indeed,it may make the most sense to construe theentire span 180930 as its long nal phase (seeagain g. 1d). This corresponds chronologicallyto one of the traditional ways of parsing theClassical period, although (and this is cen-tral to my conception) my construction is geo-graphically restricted and makes no claim tovalidity in other regions, let alone for Europe asa whole. From a different perspective (to bedescribed below) the shorter period 17801815may seem to have been decisive. In either case,

however, to conceptualize these years as FirstViennese Modernism requires explication, in-deed with respect to each of its terms.

First:Obviously, if this period is to be under-stood as representing modernity in any sense,then it can only be as a rst or early one,because the concept modern as such cannotbe dissociated from the powerful and widespreadchanges in virtually all scientic, intellectual,and artistic domains at the beginning of thetwentieth century. Indeed from todays perspec-tive one construes the period ca. 190075 asthat of high modernism,48 which was fol-lowed either by postmodernism (as I believe) orby the equally troubling, eternally deferred un-nished project of late modernism, in the fa-mous phrase of Habermas.49 (Notwithstanding

45Solomon, Beethoven(2nd rev. edn. New York: Schirmer,1998), pp. 19394.46On this subperiod, see The New Grove Dictionary,2ndedn., vol. 3, pp. 96, 102; Dahlhaus, Beethoven,p. 203.47Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music, pp. 815 (TheTwin Styles); for critiques, see Gossett, Up fromBeethoven, New York Review of Books,26 October 1989,pp. 2126; Lawrence Kramer, Classical Music andPostmodern Knowledge (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Uni-versity of California Press, 1995), pp. 4651.

48See, e.g., Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism; or, the Cul-tural Logic of Late Capitalism(Durham, N.C.: Duke Uni-versity Press, 1991), p. 55: the evaluation of what mustnow be called high or classical [!] modernism. Jamesonschap. 2, Theories of the Postmodern, is a useful, skepti-cal introduction to the contested issue of the relations be-tween modernism and postmodernism; regarding histori-cal writing, see Berkhofer, Beyond the Great Story,chaps.1, 8, 9. For a more optimistic account oriented toward mu-sic, see Kramer, Classical Music,pp. 125 et passim.49Jrgen Habermas, Die ModerneEin unvollendetesProjekt, in Kleine politische Schriften(Frankfurt am Main:Suhrkamp, 1981), pp. 44464.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

13/20

119

JWVM

the vast literature, there has been as far as Isee relatively little acknowledgment thatpostmodernism is not merely a sensibility, buta historical periodthe one we are living in.50

Perhaps this reects the general recent ten-dency to avoid periodistic thinking, describedabove. In fact, however, any time or sensibility

that sees itself as following and differing fromthat which preceded it constitutes or inhabits adistinct period.)

Of course, until recently the canonical senseof twentieth-century modernism would havefatally compromised any concept of FirstViennese Modernism before and after 1800.But twentieth-century modernism no longerenjoys its quasi-mythical status as the goal ofpostrevolutionary history in the artsa statuswhose authority depended on the belief that itwas in the course of being realized in onesown present.As just noted, it now belongs

irretrievably to the past, its hegemony broken;today, modernism functions as scarcely morethan an ostensibly nominalistic style and pe-riod designation, like any other. Moreover, dur-ing the last quarter-century postmodernism hasextended into almost as many intellectual andcultural domains as did modernism around1900, so that the latter also cannot be rescuedby an appeal to its supposedly exceptional sta-tus as Zeitgeist. These strictures apply aboveall to the heroic myth of musical modernism,with its avant-garde, scandal-ridden works ofSchoenberg (and Stravinsky) that later becamecanonized, the teleological role of serialism asthe culmination of thematic logic fromHaydn through Brahms, and all the rest. Not-withstanding its promulgation by such impor-tant gures as Adorno and Dahlhaus, it nowstands exposed as a classic example of bad oldevolutionist thinking: nobody any longer sharesDahlhauss condent belief in the ability todistinguish between those twentieth-centuryworks that will last, and those, as he liked tosay, that must be tossed into the dustbin of

history.51 Even the (by modernists) once-de-spised Richard Strauss is now increasingly seenas a legitimate exemplar, a reading that con-forms to that of Dahlhaus and other Germanscholars who employ the term modernismspecically for the subperiod 18891914 (or1918).52 Like that of modernism in general,

the hegemony of musical modernism declinedrapidly after ca. 1965, to be replaced by a still-exfoliating pluralism whose further course no-body even pretends to know.

This change is clearly acknowledged in therecent literature.53In Hermann Danusers vol-ume on the twentieth century in DahlhaussNeues Handbuch, the nal chapter is titled19501970 and includes only a brief Aus-blick on modernism, postmodernism, andneomodernism.54 To be fair, one must addthat it was published in 1984, well before theend of the chronological century; this only

makes more telling Danusers clear sense thathigh modernism had already run its course.The rst edition (1981) of Paul Grifthss widelyread volume on music after World War II wastitled Modern Music: The Avant Garde since1945, conveying the sense that high modern-ism was alive and well; in the second (1995)this was altered to Modern Music and After,with equally strong implications that are clearlyexpressed in the text (the new section devotedto modernisms afterlife is titled Many Riv-ers).55A recent political-musical study by Anne

50Again, Jameson (Postmodernism,pp. 3536, 5961) givesthis sense clearly.

51The concept of the New Music . . . serves to make aportionof the works created during the 20th century standout from the mass of the remaining ones (emphasesadded): Neue Musik als historische Kategorie (1969),rpt. Dahlhaus, Schnberg und andere: GesammelteAufstze zur Neuen Musik(Mainz: Schott, 1978), p. 29.52Walter Werbeck, Richard Strauss und die musikalischeModerne, in Richard Strauss und die Moderne: Berichtber das Internationale Symposium Mnchen, 21. bis 23.Juli 1999, ed. Bernd Edelmann et al. (Berlin: Henschel,2001), pp. 3137; Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music,pp. 33039; Danuser, Die Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts(Laaber: Laaber, 1984),pp. 1324.53Including, in one form or another, by all the participantsin the conference Music and the Aesthetics of Moder-nity held at Harvard University, November 2001 (it isplanned to publish the papers in a volume edited by KarolBerger and Anthony Newcomb).54Danuser, Die Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts, pp. 392406.55Paul Grifths, Modern Music: The Avant Garde since1945 and Modern Music and After(London: Dent, 1981;Oxford University Press, 1995).

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

14/20

120

19THENTURYMUSIC

complain about the mixture of high and lowstyle in its instrumental music, which seemedto them a violation of cogency and a breach ofdecorum.61 Even Haydns early instrumentalworks conform to this picture; publications ofhis music abroad did not begin to appear until1764,62 reviews and critical commentary not

until 176668.63

On the other hand, as Heartzemphasizes, Vienna already boasted of note-worthy achievements in the years immediatelyfollowing 1750;64 one need add only Haydnsearly string quartets, original and masterly de-spite their unassuming outward dimensions,65

and his imposing symphonic trilogy Le Matin-Le Midi-Le Soir of 1761. In short, this musichad no need of synthesis, as the evolutionistsense of Classical style must posit; it devel-oped largely on its own.

That growth was tremendous, in both vocalgenres and the rapidly developing instrumental

ones. As early as the so-called Sturm und Drangof the late 1760s and early 1770s, there musthave been a conscious demand for great mu-sic; see Haydns Quartets from op. 9 throughop. 20, perhaps composed for (unidentied)Viennese patrons,66not to mention his aston-ishing Esterhzy symphonies from the sameyears. Even against this background, however,the 1780s witnessed a new musical culture;

Shrefer places the divide as early as ca. 1965;56

the sociologically oriented Leon Botstein like-wise concludes that heroic musical modernismdied out in the mid-1970s.57Modern music,in this newly historicized and relativized sense,can no longer serve as a basis for rejecting con-cepts of earlier modernisms in music, even em-

phatic ones.

Viennese:Strictly speaking, one should em-ploy the ugly term Viennese-European. For acritical aspect of my construction is that thebeginnings of this music were local and mod-est, while its long-term effects were aestheti-cally and historically decisive across the entirecontinent. To be sure, although there were im-portant local traditions such as the sacredpastorella and Hanswurst-type dramatic pro-ductions, Viennese vocal music at midcenturydepended primarily on foreign genres and styles:

Italianate sacred vocal music and opera seria,and French ballet and opra comique(the lattertwo a hallmark of the new sensibility after1740);58in the later 1760s opera buffabecameimportant as well.59

By contrast, after 1740 Viennese instrumen-tal music was chiey local andgalantin orien-tation; the inuence of C. P. E. Bach, for ex-ample, cannot be documented there until thelate 1760s, whether in terms of the dissemina-tion of his works or compositional reception.60

Similarly, at rst this music had little reso-nance elsewhere; the theorists and journalistswho debated the burning issues of the dayscarcely took notice of Vienna, unless it was to

56Anne Shrefer, Ideologies of Serialism: The PoliticalImplications of Modernist Music, 19451965, deliveredat the Harvard conference, in which 1965 marked theend of high modernism.57Leon Botstein, Modernism, in The New Grove Dictio-nary,2nd edn., vol. 16, p. 873.58Bruce Alan Brown, Gluck and the French Theatre inVienna(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991).59Opera Buffa in Mozarts Vienna,ed. Mary Hunter andJames Webster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1997).60A. Peter Brown, Joseph Haydns Keyboard Music: Sourcesand Style (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986),chap. 7; Ulrich Leisinger, Joseph Haydn und dieEntwicklung des klassischen Klavierstils bis ca. 1785(Laaber: Laaber, 1994), chap. 7; Bernard Harrison, HaydnsKeyboard Music: Studies in Performance Practice(Oxford:Clarendon Press, 1997), chap. 5.

61Ratner, Classic Music,p. xv.62Joseph Haydn: Werke,XII/1, critical report, p. 25; Webster,The Chronology of Haydns String Quartets, MusicalQuarterly61 (1975), 35, n. 43.63Extensive quotations in H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn:Chronicle and Works,vol. 2, Haydn at Eszterhza, 17661790(Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1978), pp.12832, 15455 et passim; Gretchen Wheelock, HaydnsIngenious Jesting with Art: Contexts of Musical Wit andHumor(New York: Schirmer, 1992), chap. 3.64Heartz, Viennese School,chap. 2.65Webster, Freedom of Form in Haydns Early String Quar-tets, in Haydn Studies: Proceedings of the InternationalHaydn Conference, Washington, D.C., 1975,ed. Jens Pe-ter Larsen et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1981), pp. 52230; Haydns frhe Ensemble-Divertimenti: GeschlosseneGattung, meisterhafter Satz, in Gesellschaftsgebundeneinstrumentale Unterhaltungsmusik des 18. Jahrhundert,ed. Hubert Unverricht (Tutzing: H. Schneider, 1992), pp.87103.66There are no original sources for these works survivingfrom the Esterhzy court, and Burney described a raptur-ously attended performance of Haydn quartets (presum-ably op. 17 or op. 20) in Vienna in 1772: The Present Stateof Music in Germany,vol. I (2nd edn. London, 1775; facs.New York: Broude, 1969), p. 294.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

15/20

121

JWVM

indeed Viennese intellectual and cultural lifealtogether ourished under Joseph II as neverbefore, nor would again until the later nine-teenth century.67The court assumed a far moreimportant role in public musical life; in 1778Joseph founded the National-Theater for Ger-man drama and Singspiel (for which Mozart

composed Die Entfhrung aus dem Serail), fol-lowed in 1783 by the new opera buffa troupe(for which he composed Figaro and Cos fantutte). A local music printing industry emergedfor the rst time, led by Artaria (likewisefounded in 1778), who quickly became Haydnsleading publisher; it fostered tremendous growthin genres that appealed to both connoisseursand amateurs and hence could be composedexpressly for publication (primarily chambermusic, but also music for orchestra and solokeyboard, as well as Lieder).

Of particular signicance, in part because it

established a pattern that lasted well past 1800,was a new convergence between the activitiesof inuential patrons and composers own ar-tistic strivings. As of 177980 Haydn enjoyed asignicantly increased degree of compositionalindependence from the Esterhzy court (a factwhose wide ramications have only recentlybecome evident).68 Notwithstanding his re-stricted residence in Vienna of two months peryear, he secured patronage from, among others,Baron Gottfried van Swieten; HofratFranz Salesvon Greiner, whose wife presided over the lead-ing Viennese salon and whose daughter laterbecame famous as Caroline Pichler; Anton Liebevon Kreutzner, a wealthy provisioner to theHapsburg court; HofratFranz Erhard von Kee;and Michael Puchberg, better known as therecipient of Mozarts pathetic begging lettersfrom the late 1780s. Of course, Mozarts arrivalin 1781 had already led to his and Haydnsfriendship, which, whatever the (somewhat con-tested) truth about its character or intensity,was of incalculable importance for both com-posers compositional development.

The rest (as they say) is history. Beginning in

the 1780s Viennese music witnessed a steady

rise in productivity, compositional technique,and artistic pretension. Until 1809, the sys-tems that sustained itmodes of composi-tion and publication, noble patrons, musicalinstitutions (including theaters, academiesand private establishments, as well as middle-class musical activity), generic preferences, and

so onremained essentially unchanged, not-withstanding the death of Joseph (and hence ofthe opera buffa) and the increased degree ofpolitical repression under Leopold II and FrancisII, motivated in the rst instance by the FrenchRevolution. As this music developed, it gener-ated not only increasingly impressive examplesin the new instrumental styles, but also radicaland programmatic masterworks such as theSeven Last Words on the Crossand the EroicaSymphony, as well as humanistically upliftingworks on the largest scale, such as DieZauberte,the Creation,and Leonore/Fidelio.

Beyond that, its reception became increasinglypositive and enthusiastic until, around 1800, itculminated in a pan-European triumph, sym-bolized by the reception of the Creation(and ofMozart, after his death). It is this double tri-umphcompositional and in terms of recep-tionthat justies making this music, despiteits local origins, the basis of a historical period.

Modernismon at least four grounds:(1) Viennese instrumental music oriented to-

ward thegalantbegan to be critically discussedelsewhere in the mid-1760s. Although its ini-tial reception was not only spotty but disap-proving, even then it was uniformly understoodas new; from around 1780 on it was almostalways hailed as pathbreaking, unprecedented;in a word, as modern (cf. point [3] below). Itsmodernity is therefore not compelled to emergefrom a retrospective assessment, as is the casewith its so-called Classicism (or any classicart).69 On the contrary, except in the case ofBeethoven, its later reception as Classicalhas precisely hindered our appreciation of it asmodern.

67Derek Beales, Vienna, in The New Grove Dictionary,2nd edn., vol. 26, p. 558.68Webster, Haydn, Joseph, ibid., vol. 11, p. 181.

69As even Charles Rosen acknowledges in WashingtonHaydn Conference 1975,p. 345.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

16/20

122

19THENTURYMUSIC

(2) With the exception of Handels oratoriosin England, this music (in its post-1780 phase)is the earliest repertory that has enjoyed anunbroken tradition of performance and studyfrom its own day to ours. Put another way, itwas an essential component of the originalcanon of masterworks created in the late eigh-

teenth and (especially) early nineteenth centu-ries, against which, in turn, twentieth-cen-tury modernism was created.70These links con-stitute the primary justication for claimingthat this repertory was modern in an emphaticsense, even while denying an analogous statusfor other new musics of the past such as thears nova of the fourteenth century or theseconda pratticathe nuove musichearound 1600.71A telling (if amusing) indicationof this linkage was the function of the Classi-cal troika, Haydn-Mozart-Beethoven, as modeland hoped-for legimitization of the Second

Viennese School, Schoenberg-Berg-Webern.(3) It was in Vienna before and after 1780

that the rst quasi-autonomous instrumentalmusic developed. Like many others before him,E. T. A. Hoffmann called Haydn and Mozartthe creators of modern instrumental music(die Schpfer der neuern Instrumentalmusik);like nobody before him, he also called themand especially Beethoven the rst musical Ro-mantics (which is to say, moderns) and thusrecruited them for the future canon of abso-lute music.72Haydn and Beethoven were therst composers systematically to exploit whatlater came to be called musical logic.73With-

out employing the term, Charles Rosen bril-liantly describes Haydns modernity: Thissense that . . . the development and the dra-matic course of a work all can be found latentin the material, that the material can be madeto release its charged force so that the music . .. is literally impelled from withinthis . . .

new conception of musical art changed all thatfollowed it.74 One can go further: likeBeethoven, Haydn composed music aboutmusic: works that not only aremusic but alsoproblematize it. For Beethoven this assertionmay count as self-evident; for Haydn it willsufce to cite the tonally ambiguous openingof the String Quartet, op. 33, no. 1 (and itsconsequences), and the nale of op. 33, no. 2;the latter, far from being merely the joke thathas lent the work its nickname, is a profoundessay in what it means to end, or to begin, amusical composition in the rst place.75Self-

reexivity of this kind is a hallmark of mod-ernism in the artswith the proviso, asReinhold Brinkmann has recently pointed out,that mere self-reexivity is not enough; tobe genuinely modern such phenomena musttake on historical; i.e., broad and lasting, sig-nicance (cf. point [2]).76

(4) Most importantly, this music coincidedwith the beginnings of modern (i.e., post-revolutionary) history.77 Nineteenth-centuryGerman historians named the eighteenth, em-phatically, die neueste Zeit(as opposed to themere Neuzeit,equivalent to our early modernhistory, which had begun around 1500).78Eversince, historians and literary-cultural scholars

70On the formation of the canon, see William Weber, TheRise of Musical Classics in Eighteenth-Century England:A Study in Canon, Ritual and Ideology(Oxford: Clarendon,1992); Marcia Citron, Gender and the Musical Canon(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).71Dahlhaus, Neue Musik als historische Kategorie, p.71; cf. the text corresponding to n. 76. Thus I would rejectthe implication conveyed by Leo Schrades title Monteverdi:Creator of Modern Music(New York: Norton, 1950).72In his famous review of Beethovens Symphony No. 5(1810), rpt. in Hoffmann, Schriften zur Musik; Nachlese,ed. Friedrich Schnapp (Munich: Winkler, 1963), p. 35; trans.in Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, ed. ElliotForbes (New York: W. W. Norton, 1971), pp. 15152. (Thecomparative neuer is aptly translated as modern inthis context.)73Not, of course, that Mozart lacks logic, but his seemsto be of a different kind; at any rate, it has not been a topicof musicological discourse in the same way. This issuewarrants a separate study.

74Rosen, The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven(New York: Viking, 1971), p. 120.75On No. 1, see Webster, Haydns Farewell Symphony,pp. 12731 (earlier discussions rely on a banally corrupttext that vitiates Haydns point); on No. 2, the most inter-esting of many discussions are perhaps Wheelock, HaydnsIngenious Jesting with Art, chap. 1; Gerhard J. Winkler:Opus 33/2: Zur Anatomie eines Schlueffekts, Haydn-Studien6 (1994), 28897.76Brinkmanns point was in response to a paper by Danuseron the self-reexive category of operas about opera, de-livered at the Harvard conference cited in n. 53.77As was emphasized in Karol Bergers lead paper at thesame conference (from which some of the following refer-ences are drawn).78Koselleck, Futures Past,pp. 23166.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

17/20

123

JWVM

have conceptualized the (later) eighteenth cen-tury as having constituted the decisive phasein the creation of our world: Mircea Eliade andMarcel Gauchet as the disenchantment of theworld, the supplanting of faith by reason;79

Ernst Robert Curtius and Jacques Le Goff asthe nal dying-out of medieval mentalitsun-

der the pressure of the Industrial Revolution;80

Foucault as the age of normalization;81

Reinhart Koselleck as the Janus-faced Sattelzeit(saddle-period; i.e., cusp) in which many ofthe essential historical terms and concepts ofmodernity assumed their present guise;82HansRobert Jauss, in terms more explicitly relevantto this study, as the beginning of literary mod-ernism.83 Similarly, Kants critical philoso-phy and its subsequent dialectical historiciza-tion by Hegel, whose joint foundational roleinto our own day is undeniable, spanned pre-cisely the fty years 17801830.

During the same years, music realized itsnew destiny as the highest and most Romanticof the arts, while yet, in distinction to genuineRomanticism, maintaining its traditional aes-thetic function as mimesis; the age of abso-lute music dawned only later.84As Dahlhausemphasized, Hoffmanns apotheosis of thetroika as Romanticsthat is, as modernsrepresented the transfer of a sensibility thathad developed a half-generation earlier, in Prot-estant Germany, in a literary-aesthetic context,

to music from Catholic Austria: Not untilBeethoven did the symphony become thatwhich it had always claimed to be, but withoutactually being so.85 (He should have writtenHaydn, meaning the Haydn of the Londonsymphonies, especially since he dismissesMozarts G-Minor Symphony merely on the

grounds that it scarcely . . . penetrated theconsciousness of the musical public; this doesnot affect the larger point.) Musics role in thesedevelopments was not a matter of merecontemporaneity, but of cultural deeds no lesssignicant or inuential than those of Kantand Hegel. Adornos writings on Beethoven havebeen seminal in this regard,86although his un-derestimation of Haydn and Mozart, for whomhe proposed no link to Kant comparable to theone he posited between Beethoven and Hegel,is no longer sustainable. The Kantian interpre-tation of Mozart and Beethoven as critical

composers (Haydn still being marginalized) wasrst argued seriously in English by RoseRosengard Subotnik; she speculates interest-ingly that Adornos relative lack of interest inHaydn and Mozart may have derived from whatseemed to him their excess (as it were) of per-fection, their total integration of sound andmeaning.87

What is missing from these and similar ac-counts is an adequate sense of howthis musicbecame something that could be placed along-side philosophy.88As I have argued elsewhere,it did so most obviously by means of a newdynamic sublime (precisely in Kants sense),which was apotheosized in Haydns Creation

79Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return, trans.Willard R. Trask (New York: Pantheon, 1954); Gauchet,The Disenchantment of the World: A Political History ofReligion,trans. Oscar Burge (Princeton: Princeton Univer-sity Press, 1997).80Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages,trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: Harper and Row, 1963),pp. 1924, 58596; Le Goff, Limaginaire mdival: essais(Paris: Gallimard, 1985).81Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison,trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), pp.17094.82See Kosellecks intro. to Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe:Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache inDeutschland, ed. Otto Brunner et al., vol. I (Stuttgart: E.Klett, 1972), p. xv; compare Das achtzehnte Jahrhundertals Beginn der Neuzeit, in Epochenschwelle,ed. Herzogand Koselleck, pp. 26982.83Hans Robert Jauss, Der literarische Prozess desModernismus von Rousseau bis Adorno, Epochenschwelle,pp. 24368.84Dahlhaus,The Idea of Absolute Music,trans. Roger Lustig(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), chap. 2.

85Dahlhaus, E. T. A. Hoffmanns Beethoven-Kritik unddie sthetik des Erhabenen,Archiv fr Musikwissenschaft38 (1981), 7992 (here, 90), and cf. Romantische Musik-sthetik und Wiener Klassik, ibid., 29 (1972), 289300.86Adorno, Beethoven: The Philosophy of Music, ed. RolfTiedemann, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford: StanfordUniversity Press, 1998).87Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Developing Variations: Styleand Ideology in Western Music (Minneapolis: Universityof Minnesota Press, 1991), chaps. 4, 7 (originally publ.197982); the speculation is found on p. 50. The sameapplies to Dahlhaus, esp. regarding Mozart; see Webster,Dahlhauss Beethoven, pp. 21112.88Notwithstanding Subotniks claims for Mozarts last threesymphonies (Developing Variations,chap. 6). But see Pe-ter Glkes suggestive comments about Haydn in Nahezuein Kant der Musik, Musik-Konzepte41 (1985), 6773.

This content downloaded from 193.191.129.220 on Wed, 20 Mar 2013 04:19:18 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Clasissicism - Webster Article

18/20

124

19THENTURYMUSIC

both artistically and culturally-politically.89In-deed, the sublime was exploited by all threecomposers, most obviously by Haydn from 1791to 1802 and Beethoven from 1803 to 12, duringwhich the sublimity of Mozarts Requiem, DonGiovanni,and La clemenza di Titowas graspedas well, and the musical sublime rst theorized

by Christian Friedrich Michaelis andHoffmann.90And, to repeat, the triumph of thismusic was pan-European; the Haydn-Mozart-Beethoven style was imitated virtually every-where until the rise of musical Romanticismin the emphatic sense, which, however, oc-curred only after 1810. The vast majority ofFields and Dusseks Romantic piano musicoriginated in the second decade of the century;the same applies to Webers Lieder and pianoworks; the Lied is commonly regarded as hav-ing become a Romantic genre with Schubertsworks of mid-decade.

Hence, although this climactic phase doesnot yet have a name, it must be understood notas a mere transition, but as a period in its ownright (see g 1e). It grew out of the Enlighten-ment, whichVienna still lagging behind othercenters in this respectremained a decisiveforce at least up to 1800, as works like DieZauberte and the Creation abundantly tes-tify. Again like the Kantian period in philoso-phy, itlinksthe Enlightenment with Romanti-cism, rather than dividing them. Neither thetraditional black-and-white division of a Clas-sicalfroma Romantic period of music his-tory (g. 1a) nor a straightforward periodization

according to centuries la Dahlhaus (g. 1f)can do justice to the character and effects ofthe music of the period 17801815. The con-cept of musical modernism is far more adequateto all this than either Classicism orDahlhauss pre-Romanticism, whereby thefact that thismodernism ourished in a rela-

tively conservative (not reactionary) intellec-tual-social context doubtless contributed to itsstaying power in the long term.

Haydn, Beethoven, and the

Delayed Nineteenth Century