CHASQUI - rree.gob.pe Chasqui 31_ingles WEB.pdf · Verlaine, Paul Fort, Samain, Maeterlinck, and so...

Transcript of CHASQUI - rree.gob.pe Chasqui 31_ingles WEB.pdf · Verlaine, Paul Fort, Samain, Maeterlinck, and so...

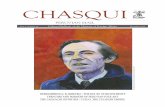

CHASQUIMinistry of Foreign Affairs Newsletter Year 14, number 31 2017

BOHEMIA DE TRUJILLO / THE FIRST NEWSPAPER OF LIMA / MIGUEL BACA ROSSI’S MAGICAL SCULPTURES / MANUEL ALZAMORA: EXPRESSIONISM AND INDIGENOUS EXPRESSIONISM / ELÍAS DEL ÁGUILA: PORTRAIT ‘AU NATUREL’ / THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE GUINEA PIG / 150 YEARS OF

PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE PERUVIAN AMAZON

PERUVIAN MAIL

Mar

iner

a by

Man

uel A

lzam

ora.

Oil

on c

anva

s. 6

7 ×

78,5

cm

, cir

ca. 1

930.

CHASQUI 2

LA BOHEMIA DE TRUJILLO1: FORWARD-LOOKING INTELLECTUAL

CIRCLE IN THE NORTH The Inca Garcilaso Cultural Center of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs pays homage to the most famous literary groups in Peru, Bohemia de Trujillo, of which Cesar Vallejo was its most famous member. This tribute is achieved

through a series of documents and images, selected by Carlos Fernández and Valentino Gianuzzi, that bring us closer to its world and show the reach of this group of young people that brought together several of the most prominent

figures of Peru’s cultural and political life.

César Vallejo has made Bohe-mia de Trujillo the most fa-mous literary group in Peru.

His literary status, however, has overshadowed the initial work and the activities of the other members of the group, who produced, apart from poems, remarkable journalism, poetic prose, tales, short stories, plays, essays, and political speeches. At the same time, the widespread consideration of Bohemia as the in-tellectual cradle of the Apra Political Party has made it difficult to study the beginnings of the group as an independent literary reality.

This exhibition tries to offer a new vision of Bohemia through documents that reveal unpublished or little-known aspects and highlight certain key events in its history: its readings, some of the controversies in which its members participated, its relationship with other arts, and other significant details about the cultural context in which they thrived. Finally, it also raises some unresolved questions about the in-tellectual biography of its members and intends to promote new archival research on the lesser-known aspects of Bohemia.

The photographs, books, and other pieces of the exhibition are mainly based on the period between the appearance of the Iris magazine, in May 1914, and the publication of the newspaper El Norte, in February 1923, because this is, despite its gaps, the best-known stage of the activities of this groups from Trujillo, as well as of its growing political activity.

With this exhibition, the Inca Garcilaso Cultural Center of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs pays homage to one of the fundamental groups of the Peruvian literary tradi-tion almost one hundred years after Juan Parra del Riego made Bohemia de Trujillo known in Lima.

Trujillo and its universityAlthough legend has the San Carlos and San Marcelo School as the edu-cational institution that made Bohe-mia possible, it is more accurate to consider the University as the space where this group became a reality.

Most the members of Bohemia came from the North, but were not necessarily born in Trujillo. However, all, except Vallejo, had studied in such school or in San Juan, another prestigious school. A significant number of the members of the group worked, while studying, in one of the schools in Trujillo.

It is worth highlighting that, despite being critical of the univer-sity —their rebelliousness against

the institution was a fundamental feature of the group, many of the Bohemians held positions in the Uni-

versity Center's governing bodies and vigorously promoted university extension, particularly Popular University.

JournalismAlmost all the members of Bohemia worked in the newsroom of a news-paper or otherwise. It was not just a form of literary learning or a way of making a living; access to the press earned them access to the cultural life of Trujillo and allowed their work to be read in other cities and media in the country.

In addition to being a way of disseminating their own work, the newspaper was a space to discuss about national and international political affairs, social news, and other leisure and cultural activities common among university stu-dents. This journalism prospered amidst the economic bonanza of Trujillo, since both La Industria and La Reforma newspapers had been established as signs of com-mercial and political progress of

Antenor Orrego, circa 1918. Vallejo looking into the Pacific, circa 1920.

Valdelomar with members of Bohemia in Chan Chan ruins, May 1918. Juan Espejo Asturriaga Archive.

CHASQUI 3

the most powerful families of the city.

On the other hand, the cultural magazines meant, for the group, gaining more prestige and growing their artistic networks nationally. Yet, the reach of these publications was much narrower and their im-pact more limited than that of the newspapers.

PoetryMost of the members of Bohemia practiced and publicly exerted poetry. All of them, including the prose writers, showed deep and true interest in poetry. As children in the 19th century, they belonged to a generation of artists who considered lyric as the highest form of expres-sion. It is not surprising then, that, through brief comments or reviews and defenses against rival attacks, the Bohemians discussed about po-etry in the pages of the newspapers in which they collaborated. Vallejo’s poetry made Antenor Orrego one of his first and most important advocates, while his prose had the same effect on José Eulogio Garrido. The poetry of Alcides Spelucín, Eloy Espinosa, Francisco Sandoval, Juan José Lora and others —Óscar Imaña, Juan Espejo Asturrizaga and Felipe Alva, who, unfortunately, did not collect their lyrical work during their lifetime— was promoted in different periodical publications.

Other ArtsAlthough the written word was the means of creation most used by Bohemia, the group was very close to other art lovers; some of them, such as Macedonio de la Torre, Camilo Blas or Carlos Valderrama, became renowned figures. In the line of French symbolism, some writings of Bohemia connected dialogue with music, dance, theater, and the plas-tic arts. In addition, in many of the events in which they participated, they coexisted with literature, so the evenings were, in fact, full of art.

On the other hand, the archae-ological development of the early 20th century contributed to the fascination that the members of Bohemia felt for the pre-Columbian world. The group leaders prompted the recovery and enhancement of the archaeological heritage of the

region and talked about them in many newspaper articles.

MemoryThis last section highlights that the history of Bohemia de Trujillo, like any other effort to recover the past, is an ongoing process. A reflection on the limits of literary historiography is proposed to the spectator and the need for future research is emphasized.

1 T.N.: aka “Bohemia trujillana” a group of intellectuals, including writers, artists, phi-losophers, and politicians from the north of Peru.

«At the time when a poet opens up to saying his first rhythms, in a faraway city in the Americas: Trujillo, an agriculturally-based village with university beliefs, with quiet and gentle lifestyle -like its green and static sugar cane fields, his growing sense of fraternity flourishes -a sense that he would never forfeit- between the words he writes and the magical creator of Trilce. He was a humble student from the highlands, with modest thirst for obtaining a doctorate degree, like so many poor Indians who mercilessly swallowed up the University. I still remember that day, vividly and blossoming in my heart, when chance put in my hands ‘Aldeana', a poem about a small rural village, with a delightful, closed and peasant atmosphere. It was the 'open sesame' that made me realize the artist’s abysmal richness. My admiration and my love surrendered to such wonderful Indian. He began to forge himself, a cordial anvil and pure hammer of life, Los heraldos negros (The Black Heralds).

Around a coffee or restaurant table, after anxiously searching, frequently unsuc-cessfully, in our pockets for those few coins that a student’s meagre budget may afford, to pay for meals and wine, we got together with José Eulogio Garrido, an Aristo-phanes-like and positively incisive thinker; Macedonio de la Torre, with multiple and superior artistic skills, perpetually distract-ed and puerile; Alcides Spelucín, unleashed

and serious like a priest; César A. Vallejo, thin, tanned and energetic concocted, with his sayings and facts of implausible infan-tile; Juan Espejo, still a stammering and shy child; Oscar Imaña, full of cordial kindness and exaggeratedly susceptible to the jokes and pranks of others; Federico Esquerre, a gentle and ironic good-hearted man, with a smile on his face; Eloy Espinosa, whom we called 'Benjamin' (the youngest one), with his exorbitant and noisy joy of life; Leoncio Muñoz, with a generous and fervid admiration; Víctor Raul Haya de la Torre, with his looming exceptional public speaking skills; and two or three years later, Juan Sotero, with his Creole and acute ironic insight; Francisco Sandoval, having undisturbed and enchanted mystical pow-ers; Alfonso Sánchez Urteaga, a painter of great strength, too young, who still had the sweetness of his mother's breasts attached to his lips, and some other boys with fresh hearts and fiery fantasy. This has been and is the poet's spiritual home.

At other times, the fraternal feast would include goat-based meals and chi-cha2, overlooking the sedative landscape of Mansiche in the humble home of some Indian. Fresh young girls with naive and supple glimpses offered the creoles dishes. They were called Huamanchumo, Piminchumo, Anhuaman, Ñique. We were served by genuine princesses of the clearest and most legitimate Chimú lineage, direct

descendants of the powerful and magnifi-cent curacas3 of Chan.

The lonely and solemn beach of Huamán, the voracious and treacherous waves, also served as landscape for these lyrical and fervent lunch gatherings. The poetries by Darío, Nervo, Walt Whitman, Verlaine, Paul Fort, Samain, Maeterlinck, and so many others were recited in these gatherings and filled the air with a com-bination of winged, melodic words with the inarticulate sounds of the sea, which opened its ‘innumerable paths' to our fantasy of travel.

Animated, thoughtful, and cordial nightly encounters, some of them graceful and others troubled. More than once the youthful uproar troubled the quiet sleep of the old provincial city. Often the crack of dawn would catch us by surprise in these parleys, which had sweet romantic flavor, quenching like a breath, the fiery blaze of our dreams».

In: César Vallejo, Trilce [1922]. Facsimile edition published by the Peruvian Academy of Language. Lima, 2016.1 TN: Peruvian poet César Vallejo’s best-known

book, considered a lead work of international modernism and a poetic masterpiece of the avant-garde in Spanish due to its lexicographi-cal and syntactical audaciousness.

2 T.N.: a fermented or non-fermented corn beer in South and Central America.

3 T.N.: community leader in the Inca Empire.

WITNESS ACCOUNTPhilosopher Antenor Orrego recalls the adventures of the young poet César Vallejo and the Bohemios de Trujillo,

in his visionary prologue to Trilce1 (1922).

One of the group's most famed artistic evenings on June 10, 1917. In the picture Antenor Orrego, José Agustín Haya de la Torre, César Vallejo, Macedonio de la Torre, among others.

Banquet offered by Cecilia Cox to the students of the Minor University of La Libertad on April 4, 1915, in Buenos Aires Beach, Trujillo.

CHASQUI 4

THE FIRST NEWSPAPER OF LIMARESTORING OLD JOURNALS

Elio Vélez Marquina*The first of the two volumes of the oldest newspaper in the Americas, printed at the beginning of the 18th century

in Lima, then capital of the Viceroyalty of Perú1, edited.

The preface of the book in question begins as follows: «In the City of Kings, in

the royal printing house of Joseph de Contreras y Alvarado a series of newspapers, journals, and lists of official character were printed; such documents would later be compiled into a single volume. A factitious cover with no date was added with the title: Diarios y memorias de los sucesos principales y noticias más sobresalientes en esta ciudad de Lima, corte del Perú [...], con las que se han recibido por cartas y gacetas de Europa... [Newspapers and memoirs of the main events and most outstanding news in this city of Lima, court of Peru [ ...], which were reported through letters and gazettes to Europe...]. The volume contains between 112 and 116 independent printouts

arranged chronologically2». This volume depicts life in Lima and its connection with the Hispanic world. This newspaper, in all like-lihood, is the first of the Americas and, the history of journalism in this continent should be rewritten in light of a study of such paper.

This first volume covers the period from 1700 to 1705 of the collection housed in the New York Public Library. The second and final volume, covering until 1711, will be released in 2018.

The material included, which has remained practically unknown to scholars, offers us a wealth of information about the events that happened in Lima in the early 18th century and the events that shook Europe at the same time.

Because the machinery of the Contreras’ printing house was torn and worn, the surviving copies of the newspaper are difficult to read. Thus, the edition prepared by Firbas and Rodríguez Garrido rep-resents a real contribution that not only fixes the text, but also glosses it so that it may be contextualized. Also, the edition is available on the webpage of the Proyecto Estudios Indianos [Project of Indian Studies], for historians, economists, linguists and other scholars interested in the viceregal America can readily consult such information.

The Peruvian Empire in light of The Information in the Diario de LimaDuring the second half of the 17th century, Lima was not only the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru, seat of the viceregal and ar-

chiepiscopal palaces, but was also the most important geopolitical center of the Hispanic world in South America. We now know that the ships that arrived at the ports of Lima left the city with more than shipments: the news of their political, ecclesiastical, economic, and cultural activities was spread in the same way as the news of the main European Courts. Thus, power, that is, the empire of the Viceroyalty of Peru was based on something more than trade and the distribution of goods. It was supported, mostly, in managing information and in the ability to take printed material to the most remote place from its center.

The city’s local stories, its reli-gious and imperial celebrations, its tremors and natural alterations, the distribution of activities or the implementation of justice, the circulation of ships along the American coasts, all intermingle in these pages with the political ten-sion and European battles during the War of the Spanish Succession. Faced with the European war, the printing press in Lima played a fundamental political role to con-solidate loyalty to the cause of the Bourbon dynasty in the Americas; but, in addition to that clear offi-cial intervention in politics, the newspaper abounds in information and narrations on the culture and economy of the Americas and shows the impressive circulation of people, papers, and goods through the Spanish monarchy’s extensive network.

Large urban or productive centers such as Panama, Portobe-lo, Cartagena, Santa Fe, Quito, Guayaquil, Piura, Huancavelica, Potosi, Buenos Aires, Santiago, and Valparaiso are some of the cities alluded to by the newspaper due to their dependence on the court-city. From Lima came news about the matrimonial alliances of nobles, the numerous imperial feasts, the appointments and chairs of the Royal University of San Mar-cos, and abundant information about the religious orders and their churches-so much so that it earned the viceregal city the nickname of saint. Also, we now known about the details of the reconstruction of the city after the 1687 earthquake.

About the PublishersPaul Firbas is an associate pro-fessor in the Department of His-panic Languages & Literature at

We now know that the ships that arrived at the ports of Lima left the city with more than shipments: the news of their political, ecclesiastical, economic,

and cultural activities was spread in the same way as the news of the main

European Courts. Thus, power, that is, the empire of the Viceroyalty of Peru was based on something more than

trade and the distribution of goods. It was supported, mostly, in managing

information and in the ability to take printed material to the most remote

place from its center.

CHASQUI 5

February 19, 1701The town of Guancavelica repor-ted that its governor, Mr. Matías de Lagunes, Oidor1 to this Royal Audience, was very sick, possibly terminally ill. A strong earthquake shook the city nine o' clock and at two a.m. it began to rain so heavily that many people woke up in awe. They were streams of water flowing from the mountains. The Lima river has come with so much flow and strength that it has destroyed the water intakes through which the Surco, Maranga, and Molino de La Alameda valleys are irrigated.

May 20, 1701There was news about the disap-pearance of the frigate called San Jorge, manned by Captain Juan de Vechis, which coming from Co-quimbo to the port of Arica, whe-re a few passengers boarded and a shipment of silver, turned to the port of Pisco, where it was stran-ded and broke into pieces. Miracu-lously, people were safe. Since the boat ran ashore in Aguata, it was possible to rescue the shipment of silver and a portion of the ship-ment of copper; yet the glass and wheat it brought were lost.

May 25, 1701A mailman from Potosí arrived with letters from Buenos Aires re-porting on the death of King Car-los II, who is in glory, such news was given by the governor of the new colony of the Sacramento, which belongs to the Portuguese of San Gabriel. The eve of Corpus Christi, usually a time of great re-joicing and happy gathering in the main square to watch the creative fireworks-a sign of ingenuity, was dark and unimpressive, a black veil seemed to cover our hearts, sadden with the death of our king and lord; the joy of the fireworks was avoided since they are not signs of much worship to the Lord. However, the next day, the proces-sion took place with the solemni-ty and splendor that always hung beautifully on the streets, between various dances and giant mimics and other circumstances, which made the day festive and cheerful; with the attendance of His Exce-llency, with the lords of the Royal Court, the courts and the city cou-ncil, but with the mourning clai-med by the recent sorrow at the death of our King, since his last rites had not yet taken place.

February 20,1702 A new sign was seen in the sky, which seemed to bring its move-ment from east to west; the color it showed was silvery; the shape and figure, although seen several nights, has been changed depen-ding on judgments; to some it seemed like a palm, and of cour-se admitted it as the prognosis of happy events; for others, it seemed like the blade of a sword without garrison; but never shedding blood. The astrologers have not made specific judgments because they have not recognized any star in its making. God willing such comet is a bearer of good as such new things in the sky are usually numb tongues announcing stran-ge things on earth.

April 8, 1703Knighted Joseph de Contreras y Alvarado, royal printer of Lima, to hold an office in the name of His Majesty, which affords him title, privileges, rights as royal pr-inter, he wanted to celebrate this honor by placing on the door of his house and office a beautifully carved coat of arms of royal wea-pons, brought from the church

of St. Augustine, where a solemn mass was sung for the health of His Majesty and from where, in the company of the knights of the Order of Santiago, who had attended such service because it was a worship day, he brought it to be placed in his house, cele-brating the health and life of His Majesty that night with fireworks and rumor of musical instru-ments, and ended the day with a bullfight.

December 31, 1704The French ship called San Car-los, which had stopped in Pisco, docked in the port of Callao. Two French priest from the Company of Jesus order were on board; they have been assigned such mission to China by their leader and en-couraged by their king. The cap-tain has been given permission to get off and sell some trifles (as ordered by His Majesty) so that they may replenish and continue their journey to China without allowing them another type of trade.

1 T.N. a judge-highest organ of justice within the Spanish Empire.

News from Lima and the Empire

Stony Brook University. He has edited the poem Armas antárticas (2006), by Juan de Miramontes Zuázola, and the volume Épica y colonia: ensayos sobre el género épico en Iberoamérica (2008), and published numerous articles on colonial cul-ture, particularly in the Andean area. He is director of the line of research on American epic in the Project of Indian Studies (www.estudiosindianos.org).

José A. Rodríguez Garrido is senior professor at the Department of Humanities at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. He is co-editor of the volumes Edición y anotación de textos coloniales hispano-americanos (Madrid, 1999) and El teatro en la Hispanoamérica colonial (Madrid, 2008), and author of the book La Carta Atenagórica de Sor Juana: textos inéditos de una polémi-ca (Mexico, 2004). He is director of the Indiana Philology line of research in the Project of Indian Studies.

About the Indian Studies Project It is a laboratory of ideas, co-direct-ed by the University of the Pacific and the University of Navarra, to investigate, manage, and preserve the historic and documentary heritage of the Peruvian and Lat-in American baroque. It is also an effective tool to manage in a responsible manner the historic and documentary heritage that serves as the basis for the cultural and social development of the dif-ferent Hispano-American nations. The importance of the document is revived, through philological study, and is made known through the tools of the digital Humanities.

With already ten printed books, we have published a first volume of the Diario de noticias sobresalientes en Lima (which in-cludes the News of Europe). It has academic partners in 11 countries (America and Europe) and to date it has 12 lines of research, which combine classic lines of

research with newer ones such as science and technology or vicere-gal agroindustry.

Since its creation, ten volumes have been published, including the Diario de noticias sobresalientes en Lima, whose digital editions are available on its website. In 2017 and the beginning of 2018,

a second dozen studies and philo-logical editions will be published.

* Indian Studies Project Coordinator.

1 Diario de noticias sobresalientes en Lima y noti-cias de Europa (1701-1711). Edición y estudio de Paul Firbas y José Antonio Rodríguez Garrido, Nueva York, IDEA, 2017, collection Estudios Indianos, 10, 377 pages.

2 Firbas y Rodríguez, p. 9.

View of Lima from the Bullfighting Rink. Engraving by Fernando Brambila, 18th century.

CHASQUI 6

MIGUEL BACA ROSSI’S MAGICAL SCULPTURES

Guillermo Niño de Guzmán

Anthological exhibition of the sculptor Miguel Baca Rossi in the Inca Garcilaso Cultural Center of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Miguel Baca Rossi died a few months ago, just when he was going to

turn one-hundred years old in 2017. At age 99, the Lambayecan artist passed away with the same discretion with which he under-took his hard work as a sculptor, dedicated in large part to hon-oring the memory of illustrious characters. New generations may not be familiar with his name, yet, paradoxically, we have been able to appreciate his work with more frequency and perseverance than we have those of other artists. This is due to a unique feature, one that distinguishes him amongst his fel-low workers: his career is there for all to see, in the streets, buildings, and squares of Lima, like in other cities of Peru and other countries. Baca Rossi opted for monumental sculpture and, in that vein, he has been one of our most remarkable performers.

Like architecture, monumental sculpture is embedded into the ur-ban landscape and, consequently, is assimilated by our everyday gaze. It offers unusual and extraordinary linkage to artistic work: the specta-tor no longer has to go to a muse-um or a gallery to admire a piece and have an aesthetic experience. Busts, statues, friezes or reliefs of-ten decorate public spaces, which explains why, in many cases, they play a civic role, save a religious one. Hence the profusion of rep-resentations of heroes, leaders, and figures of culture. While seeking to highlight their legacy, he tries to en-hance those values that contribute to foster a national identity. These sculptures are present in many of the meeting points and recreation places used by the inhabitants of the city, who may recognize these characters, although they usually ignore the names of the creators of the effigies.

In Peru, sculpture developed more slowly than did painting. Hence, most of the pieces that adorn the monuments that were built in Lima in the 19th century

were made by European artists. In the next century, the situa-tion improved with the arrival of Spaniards Manuel Piqueras Cotolí

(responsible for designing the Na-tional School of Fine Arts’s facade) and Victorio Macho (author of the monument to Miguel Grau),

who sought refuge in Peru after the defeat of the Republic in the civil war. They cleared a path for contemporary sculpture, which would be followed by Baca Rossi, who studied at the School of Fine Arts in the forties, after a failed start as a medical student at the University of San Marcos.

Certainly, his plastic arts talent became evident early on. Born in the port of Pimentel, he surely discovered his ability to shape figures by making contact with sand and sea. He further developed his talent working in his father's foundry, creating shapes and volumes with plaster cast. When he was 18 years old, he traveled to Lima to study Med-icine. Undoubtedly, his artistic interests remained intact, but at that time, thinking about carving out a career as a sculptor in Peru was a chimera. There were no exhibition halls and no special-ized critics. Despite this, after a while, Baca Rossi discovered that he was not willing to give up his original calling and decided to take the risk. He dropped out of San Marcos and enrolled in the National School of Fine Arts, where he would graduate in 1943.

Miguel Baca Rossi (1917-2016).

El encierro. (Closed) Fiberglass. 23 × 48 × 43 cm. 1975.

CHASQUI 7

From that moment, he com-bined his artistic practice with teaching. He taught at the San Carlos School and, later, at the National University of Engineering and at the Catholic University. He also gave lessons at the School of in Fine Arts, of which he would be director between 1983 and 1985. At the beginning of the fifties, his initial enthusiasm for topograph-ic anatomy helped him to make

models of organs and parts of the human body. At the time, he used new materials, such as plastic, that would be used for pedagogical pur-poses in schools and universities in Peru, as well as in Colombia and Venezuela. Meanwhile, he was concerned with refining his

sculptural work. In the absence of galleries, he managed to open a market when he executed two large-scale works in Chiclayo. The first was a 5-meter granite mausoleum for Colonel José Leonardo Ortiz (1944). The second was a donation of a 4.5-meter granite monument to the Immaculate Virgin (1946) to the Cathedral of that city.

Baca Rossi engaged in exploit-ing two creative veins, in which he

obtained very good results. The most notorious is the monumental aspect to which we have referred and which earned him his profes-sional reputation; his most salient pieces are the statue of César Vallejo that stands in the square of the Segura theater; a statute in

homage to José Carlos Mariátegui in front of the Lawn Tennis; the monument to the liberator Simón Bolívar located in the premises of the Andean Community; and the monument to Santa Rosa de Lima located in the cemetery of the National Police in Chorrillos.

The other vein is the one con-sisting of smaller but still im-portant sculptures. Baca Rossi was a very sought-after artist to carry out works for public spaces, which meant adopting certain formal parameters and adapting to urban requirements. However, when accepting these projects, he insisted on creating something more intimate, in which he could let the magic that emanated from his hands do what he wanted. In this regard, we must say that Baca Rossi was an all-terrain sculptor, skillful in the use of granite, mar-ble or bronze, capable of carving busts and even smaller pieces with an undeniable subtlety and sen-sitivity (among these, his stylized compositions of boys and girls stand out in a scene called "First love"). His figurative interest also extended to animals, as shown in his monument to Santorín, the champion thoroughbred, and pieces of smaller dimensions that recreate Peruvian horses, donkeys

or bulls (passages of the Fiesta Brava (bullfighting) such as the exceptional work called El encierro).

The sculptor was, above all, a very gifted portraitist, who im-posed an expressionist look on his creations. And, while remain-ing true to his models, he was able to take certain liberties and accentuate certain features, since he knew that ultimate challenge went beyond any technical suffi-ciency. It was about expressing the character, the vibration of a temperament. For that reason, he gave his characters a force that did not depend on the accuracy in the reproduction of the features, but on the intuition and depth of the artist to capture the mystery and raison d'être. This attitude stands out in his sculptural representa-tions -after all, that is what they are- of the Inca Garcilaso, Vallejo or Don Quixote, as well as in his stupendous «notes of nature», among these La Tomasa, that tall and strong black woman that he glanced at as he swiftly passed by a bus stop. As he revealed to his family, her proud countenance impacted him so much that he only managed to calm down when he «remade» the woman with clay in his workshop. That is, when he gave a breath of life to his creation.

Micaela Bastidas. Fiberglass. 72,3 × 59 × 42 cm. 1979.

La Tomasa. Plaster cast. 41 × 32 × 23,4 cm. 1981.

The sculptor was, above all, a very gifted portraitist, who imposed an

expressionist look on his creations. And, while remaining true to his models, he was able to take certain liberties and

accentuate certain features, since he knew that ultimate challenge went beyond any

technical sufficiency.

CHASQUI 8

MANUEL ALZAMORA YEXPRESSIONISM AND INDIGENOUS EXPRESSIONISM

The Inca Garcilaso Cultural Center of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs hosts an anthological exhibition of Manuel Alazamora (1900-1975), one of the most original and lesser-known artist of the indigenous vanguard.

The character of Manuel Al-zamora’s work depicts the dignity that he assigns to the artistic activity. Beyond rep-resenting and expressing the

social problems of his time, his paintings have the virtue of showing that reality has substance free of all speculation. The surface of his paintings never offers a sense of transience and this is clearly inherent in the poetic nature of his pic-

tures, his connection with the most direct facts of life that impact him and touch him moving him beyond the pure and simple cultural category to which certain currents are often applied. For him, art springs from the earth and from people, from loneliness and violence, from pain and despair.

This artist stands out for his stylistical-ly unitary painting and an exceptionally gifted pupil to capture the colorfulness of the Andean landscape with its trans-parent air of solar splendor. The painter did not allow himself to be seduced by the easy solutions of a local painting or

by picturesqueness, but he addressed the social issue of peasant exploitation always demonstrating a mastery of the activity characterized by delicate tones of grays, blues, and browns, as well as Andean luminosities that make Alzamora's paint-ing the most successful exponent of the social image of the types and customs of the highlands.

Born in the city of Sicuani, near Cuz-co, in 1900, Carlos Alzamora moved with his family to Arequipa when he was only six months old. In Arequipa, the artist lived most of his childhood and youth, and there he also returned to establish himself in adulthood. He completed his secondary studies at Mercedario School sharing desk with the avantgarde poet Alberto Hidalgo. Later, he entered the National University of San Agustín, where he studied two years of Liberal Arts, dropping out shortly thereafter he devoted himself to his artistic vocation and militant activism. He traveled to Chile to engage in painting; there are no data suggesting he studied in any academy or art school there. Perhaps, this means that he was a true self-taught artist.

In Arequipa, the painter gauged the distant green areas, the transparent air, and he is certain that under that bluish sky, between those walls of ashlar and trees bordering the dykes, he found the place he was looking for. When he held a brush, he felt that he could show that land of green, violet, and golden colors that stretched out before his eyes, where light and color merge and boundaries, walls, paths, trees, an idyllic world emerge.

In 1971, Manuel Alzamora, the com-bative artist, let go of brushes and colors. His body affected by a serious illness ceased to exist on July 24, 1975 at his home on Mercaderes St. 328. He was 74 years old and had abundant and valuable artistic works, now in the hands of his descendants.

Street Theater. Oil on canvas. Ca. 1930.The Fair. Oil on canvas. Ca. 1932.

Selfportrait

CHASQUI 9

MANUEL ALZAMORA YEXPRESSIONISM AND INDIGENOUS EXPRESSIONISM

The Inca Garcilaso Cultural Center of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs hosts an anthological exhibition of Manuel Alazamora (1900-1975), one of the most original and lesser-known artist of the indigenous vanguard.

Left. Market in Sicuani. Oil on canvas. Ca. 1930.

Christianing. Oil on canvas. 91 × 64,5 cm. 1930.

Selling Fish. Oil on canvas. 36,5 × 44 cm, ca. 1930.

Sunrise by the lake. Oil on canvas. 49 × 40 cm, ca. 1930.

The Castle, Cayma. Oil on canvas. 49 × 59 cm, ca. 1928.

CHASQUI 10

ELÍAS DEL ÁGUILA: PORTRAIT ‘AU NATUREL’

Carlo Trivelli*A large exhibition in Lima allows us to appreciate the work of one of the most outstanding

Peruvian photographers of the early 20th century.

From April 20 to June 4, 2017, the Centro de la Imagen (Image Center) presented the exhi-

bition «Rediscovering Elías del Águila. Photographic portrait and middle class in Lima after 1900», in the Germán Krüger Espantoso gallery of the Peruvian North Amer-ican Cultural Institute (ICPNA).

Composed of some 300 imag-es —including vintage copies and contemporary prints, the exhibi-tion was the first contemporary approach to the work of a photogra-pher hitherto practically unknown.

The only reference to Elías del Águila was a succinct entry in the documentary annex of the catalog La recuperación de la memoria. 1842-1942, el primer siglo de la fotografía en el Perú (MALi, 2001) until a few months ago when the team of the Historical Archive of the Image Center, directed by Jorge Villacorta and Cecilia Salgado, discovered that the vast collection of almost 24,000 plate glass negatives —dated between 1896 and 1934 approxi-mately— were taken by this almost forgotten photographer born in Tarapoto in the last quarter of the 19th century.

The batch of negatives —pur-chased in 2011 by Juan Mulder and stored since then in the Image Center— had been attributed, over the years, to the late stage of the famous studio Fotografía Central, a photo studio founded in Lima by the French brothers Aquiles and Eugenio Courret in 1863. This pho-to studio was undoubtedly the most renowned in Lima, even after Eu-genio Courret sold it before return-ing to France at the beginning of the 20th century. Alfons Dubreuil and then to his son René took over the business. In 1935, when the business had to close its doors, Dubreuil compensated his workers by distributing among them more than 150,000 glass plates that con-stituted the record of the studio. Of those, some 54,000 negatives have been kept in the National Library of Peru since the end of the 1980s, thanks to the initiative of its then director Juan Mejía Baca. There was no clear news about the remainder and many people thought that this batch belonged to the missing por-tion of that collection.

Story about a DiscoveryWhen Villacorta and Salgado be-gan to study the plates —a thousand of which had undergone, through-out 2014, a process of conservation and stabilization thanks to funds provided by the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies

(DRCLAS) at Harvard University, they did not find connections with those kept in the National Library. The numbering, the traces of the plate holders, the backdrops, the props of the collection under study did not match those found in the negatives of the Courret Studio. On the other hand, it was possible to trace some photographs of the collection to the Portuguese pho-tographer Manuel Moral and some members of his family.

Settled in Peru since 1883, Moral opened a photo studio in the port of Callao and, after a while, he moved his business to a store on Calle de las Mantas (today, the first block of Jirón Callao), in downtown Lima. By the early 20th century, his good name and recognized activity allowed him to leave that studio to move to a better and more opulent establishment, located in the old Café Americano (American Café)

on Calle de los Mercaderes (today, block 4 of Jiron de la Union), right in front of the famous Courret Studio. Moral would publish an advertisement in the newspaper El Comercio on April 4, 1903 in which he explained that the photo studio he had held until was «from that date onward owned by Mr. Elías del Águila, who had been his outstand-ing disciple for fifteen years». This and other clues pointing to Elías del Águila began to appear on the horizon of the investigations, until finally conclusive evidence that allowed to determine the author-ship of the collection was found. A comparative analysis between the negatives under study and a series of vintage copies bearing the seal of Elias del Águila —belonging to Herman Schwarz’s collection— showed that they had the same backdrops and the same props in both sets. Researchers found some

exact correlation between signed vintage prints and negatives of the collection under study. There was no longer any doubt: the plates bought by Juan Mulder were Elías del Águila’s file. But who was this photographer?

The Photographer of the Middle ClassJust one bibliographical reference gave some clues to Elías del Águila’s work: in an article published in the magazine Variedades in 1914, the painter, photographer, and art critic Teófilo Castillo made a quick assessment of the photographic production in the capital and, af-ter explaining that the golden age of portrait, embodied by Courret, Garreaud, and Moral, had come to an end, he announced hopefully: «Luckily it seems [that] an awaken-ing begins with Gáldos [sic] and Del Águila, especially with the latter,

Sarita Ledgard. Ca. 1927.

Lorenzo Lama. Ca. 1904.

Óscar Fernández. Ca. 1916.

CHASQUI 11

who deserves the praise of some of his recent productions […] a true novelty, joy for the retinas little fatigued because of the gloominess [sic] that is seen around there...». Be-yond these compliments, however, we kept asking ourselves who Elías del Águila was and what character-ized his photography.

An interesting clue was provid-ed by the advertisements of the time. Several Ad pages of Ilustración Peruana1 in 1911 showed that, while Del Águila announced that «all good and cheap work» was done in his photo studio, Moral pointed out to a select public, stating: «If money does not matter, take you photos in Moral Photo Studio». Moreover, in several issues of the magazine Figuritas of 1912, the following can be read: «Photograph E. del Águila y Cía. The second best and cheap-est photos». Certainly, the disciple and his teacher targeted different segments of the portraits market in Lima at the beginning of the 20th century.

Another important clue con-sisted of some of the characters portrayed by Del Águila: many of whom were prominent profession-als, such as the architects Ricardo Malachowski —who designed the Government Palace, the façade of the Archbishop's Palace and the Club Nacional (National Club), among other important buildings of Lima— and Augusto Benavides Diez Canseco —known for having developed the Andean or Serrano style, particularly in the Urban-ización Los Cóndores de Chaclacayo, and for having been mayor of Lima between 1946 and 1947; the agronomist José Antonio de La-

valle, whose love for horses would inspire the «José Antonio» waltz by Chabuca Granda; the child Fernan-do Belaunde Terry, portrayed by Del Águila when we has 3 and 11 years old, when he probably did not dream of being president of Peru twice; or the German journalist and activist Dora Mayer —who founded with Pedro Zulen the Pro Indige-nous Association in 1909, among others. These characters helped us to begin to define, at least in part, the profile of Elías del Águila's cli-entele as one that can be identified with the rising middle class made up of professionals, businessmen, and merchants— many of them foreign immigrants —as well as public officers of the second half of the Aristocratic Republic (1895-1919) and of the 11-year Leguía Administration (1919-1930), when this social group experienced a considerable growth.

By integrating these clues, Elías del Águila’s figure appears as that of a professional whom the nickname of portraitist of the emerging Lima

middle class of the early 20th cen-tury seems appropriate. Adding to this characterization the important number of plaques in the collection kept in the Image Center, there is no question that we are before an ar-chive of undeniable historical value.

A New Style for a New Social ClassAlthough the investigations are still in their initial stage, it has already been possible to determine some of the characteristics of the photo-graphic work of Elías del Águila. Most prominent among these is, first of all, his delicate handling of light, as evidenced by the bride portrait of María de Abril, for ex-ample, in which the photographer uses his means with preciseness to outline with light the model’s pro-file and highlight her beauty. But in the long run, it would be more important for Del Águila's photog-raphy to emphasize his talent to make people pose with naturalness. It is something that is clearly seen when taking into account the large

repertoire of poses that he used to prepare his clients before the camera and, perhaps above all, his ability to portray children, some-thing that seems to have been one of his specialties.

In general, Del Águila’s pho-tography can be characterized as one that practiced photographic portrait circumventing solemnity and depth —unlike what was estab-lished by tradition— and, instead, he opted for creating a casual and relaxed image for the persons he portrayed. This is achieved not only with the precise handling of body language that Del Águila shows, but with an abandonment of pictorial aesthetics as an aes-thetic reference for portraits. Del Águila is, in that sense, the creator of a properly photographic language, in keeping with the times of mod-ernization and progress that he had to live and that would forever change the image of Lima and its inhabitants.

* Editor, curator, and journalist.

Eduardo Fano’s children. Ca. 1912.

María E. de Abril. Ca. 1903.

Elías del Águila. Self-portrait, ca. 1916.

Elías del Águila Pérez was born in Tarapoto between July and Au-gust, 1875. His parents were Igna-cio del Águila and Andrea Pérez. He was a student, a collaborator, and a close friend of Manuel Moral, as evidenced by the fact that he was godfather to one of Moral’s daughters, Rosa Amelia, and that the Portuguese photog-

rapher was a witness of his civil marriage with Tomasa Ana María Gaviño in 1901. Throughout his life, Del Águila lived in Calle Cotabamba 37, in Jirón Callao 152, in Dos de Mayo square, and in Jirón Bailones 148 in Breña. He had three daughters: Exilda, Gloria y Mene. He collaborated with many magazines such as

Prisma (1906-1907), Ilustración Peruana (1910), Lulú (1915), and Figuritas, among others, and his photographs illustrated the book of Centurión Herrera El Perú y las colonias extranjeras. He died in Lima on September 27, 1953. His remains lie in Presbístero Maestro Cemetery, San Rosendo D 26.Sarita Ledgard. Ca. 1927.

PHOTOGRAPHER'S PROFILE

CHASQUI 12

Ricardo Bedoya*

CHALLENGES AND TASKS OF THE PERUVIAN CINEMA

An approach to the increasing film production in Peru.

Figures for 2016 are signif-icant. 47 Peruvian feature films were shown in various

regions of Peru. Only 25 of them were projected in commercial cin-ema chains; 9 of which were seen by more than 10,000 spectators (Rojas, 2016).

Since the premiere of ¡Asu mare! (2013), Tondero is the production company that manages to lure the largest number of spectators to movie theaters. In 2016, with mov-ies like Locos de amor, Guerrero and Siete semillas, Tondero repeated the formula of proven efficacy: fiction based on the comedy repertoires or stories of personal success are the audience’s preferred genre; its protagonists are prominent and media people (television stars, an emblematic football player). Public premier is preceded by a marketing campaign that incorporates the active participation of commercial brands. A unique dynamic is then established: the film is developed as a package arranged between producers, distribution companies, the concerned «famous star», and the sponsoring brands.

Comparing Tondero's film activity in 2016 with that of the other Peruvian films released, Ro-drigo Chávez states: «The producer gathered 46,1 % of spectators (2,5 million viewers out of 5,6 million) thanks to its four premieres that year, three of them ranked in the Top 5 movies with more viewers of 2016» (Chávez, 2017)1.

These figures show that only one company catches the public’s interest, leaving behind other works, whether self-managed pro-ductions carried out in Lima or in other regions, or films promoted with the intervention of state re-sources and international funds. The showing of the two most interesting and original titles of 2016, Solos, by Joanna Lombardi (produced by Tondero), and Vid-eofilia (and other viral syndromes), by Luis Daniel Molero, was hampered by film chains that withdrew these films from the listings just days after their entry to the billboard.

Indeed, low profile films or films of fragile production face great difficulties in securing public showings, as a result they must

tempt alternative forms of dif-fusion. This is the case of the so-called «regional cinema». A re-cently published book, Las miradas múltiples. El cine regional peruano, (Multiple glances. Peruvian Re-gional Movie Theaters), the output of an investigation carried out in the University of Lima by Emilio Bustamante and Jaime Luna Victo-ria, demonstrates the dynamism of the production carried out outside the capital city. Since 1996, more than 200 feature films directed by a hundred filmmakers have been produced in Ayacucho, Puno, Cajamarca, Iquitos, Huancavelica, among other regions. In 2016, only three regional films were shown in movie theaters: Sebastian, by Carlos Ciurlizza, made in Chi-clayo; Tras la oscuridad, (Behind the Dark) by Miguel Vargas Rosas, made in Huanuco; and Venganza justa, (Fair Revenge) by Ronald A. Terrones, produced and shown in Cajamarca. Through alternative showings, however, films made in Arequipa, Cajamarca, Ayacucho, Junín, among others, produced throughout the country were shown. Multiplexes only assign slots to films that meet the expec-tations of mass taste, ignoring the others. The most striking and re-markable title of 2017, Wiñaypacha, by Óscar Catacora, filmed in Puno and in Aymara language, awaits to be released; let’s hope it happens.

In parallel, the volume of docu-mentary and short film production increases. These films are made mostly by the younger filmmakers

who are waiting for a chance to make feature films. The project contests organized by the Ministry of Culture proves such increase in expectations: the number of applicants is increasing.

Despite all this activity, it is not possible to talk about a film industry per se in Peru. Founda-tions for that are not even laid. Each film undertaking has its own profile and the promotional legislation dates back to pre-digital times. Based on a system of project contests and initiatives, the legal framework in force since 1994 hin-ders the possibility of forecasting investment and estimating risks, fundamental calculations in any economic activity: the contests are random by nature and afford no room for planned investment.

Despite these uncertainties, the resources provided by the Ministry of Culture, as required by law, are crucial for films that propose different stylistic treatments or that encourage greater expressive ambitions. The most accomplished films of the first months of 2017, [wi:k], by Rodrigo Moreno del Valle; La última tarde, by Joel Calero; and Rosa Chumbe, by Jonatan Relayze, were given funds to go ahead with some of the different stages of their productions. However, those recog-nitions did not help them in being considered for the cinemas listings. They premiered after circumvent-ing many obstacles of the multiplex chains and only Calero’s remained more than two weeks thanks to an excellent bouche à oreille.

Concentration in screening and lack of visibility for many films made in the country: those are problems that must be faced. But there is more. So far in 2017, there is a decline in the number of spectators for Peruvian cinema: no premiere has managed to attract a million viewers. Without a doubt, the waters seem to return to their level, clearing the illusion of rep-licating each year the successes of ¡Asu mare! and ¡Asu mare 2! (2015), which were seen by three million viewers. These phenomena are difficult to recur.

In the last months, a new act for the film has been debated. Change is indispensable and the new cinema policies should focus on five key aspects: the stimulation of the feature and short films production (crucial for training and mastery of the activity); the allocation of a fixed percentage of public support to the projects of the youngest and of the film-makers from the different regions; the promotion of the plurality of issues, styles, and forms of cine-matographic representation; the procurement of visibility of the films, guaranteeing that they can be exhibited in cinemas with sim-ilar rights as a Hollywood movie; the undertaking of a work of train-ing of audiences and filmmakers. A central issue to develop: the presence of Peruvian cinema on digital platforms that are changing the ways of consuming the images and sounds of today's cinema.

References:Rojas, Laslo (2016). «Estas son las

47 películas que se estrenaron el 2016». (“These are the 47 films fea-tured in 2016”) Available at www.cinencuentro.com/2016/12/28/estas-son-las-47-peliculas-peruanas-que-se-estrenaron-el-2016.

Chávez, Rodrigo (2017). «Taquilla 2016 (I) – Los reyes del cine peruano». (“2016 Box Office (I) – The kings of Peruvian Movies”) Available at https://cajadeskinner.blog/2017/06/09/taquilla-2016-i-los-reyes-del-cineperuano.

* Film critic and professor at University of Lima.

1 Until September 2017, 12 titles had been released. It is not yet possible to determi-ne how many were show in alternative scenarios.

La última tarde [The Last Afternoon] (2017), by Joel Calero.

CHASQUI 13

SOUNDS OF PERU

HATUN CHARANGO,MUSIC MISCEGENATION

Abraham Padilla Benavides*

Symbolizing sound, giving it its own outlines, transmuting matter to express the inner

world is what happens whenever a human being invents, modifies, or plays a musical instrument. In this ancestral road of exploration of the sounds of stones, bones or wood, the Peruvian settlers have been refining, throughout history, their skills and technology to make instruments that reflect the complexity and richness of our society, which is diverse, mixed, and pluricultural.

Instruments that came first with the Spanish conquest and then with the inclusion of African popula-tions into our society have been add-ed to the list instruments native to Peru, many of which are still being used today such as the antaras, tinyas (drums), pinkullos (aerophones), and others. As a result, throughout the Peruvian territory, there are multi-ple variations of instruments with different morphology and tuning, which, coupled with the preference for thick and heterogeneous chimes, propitiates an idea of traditional Peruvian music full of unique colors and unusual expressive nuances. In this sense, Peruvian musicians have transformed the shape, per-formance techniques, and sound characteristics of the instruments arrived from Europe with the con-quest to be used with the typical parameters of local music. The harps, violins, guitars, drums, etc., have been massively adapted to popular subjectivity. And that is what instruments are: personal and social tools of self-expression.

For this reason, for example, traditional Andean music takes advantage of the characteristics of violins to include microtones in its themes, something essential to its musical language. Also, there are different types of harps in different locations in Peru, with different numbers, materials, and string systems. The Ayacucho gui-tar, although basically similar to the others, is played with its own techniques, meeting the expressive needs of the music of this region. All of these aspects are a clear

expression of the Peruvian sonic miscegenation.

Descendant of the vihuelas, laudes (a type of guitar), and guitars, several types of charango- a small American acute «guitarrita»- ap-peared and established in the Amer-icas. We appreciate many varieties in the current territories of Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Ecua-dor. These charangos have historically had different morphological and sonorous characteristics, with differ-ent number of strings and tunings. Starting from this great diversity, the

musicians who play charango have been gradually setting more and more standardized characteristics. In Peru, the typical Ayacucho charango looks like a small guitar with five strings (one double), with parallel lids and a thin neck. It is usually used with strumming, tremolos and sharp melodies, bringing brightness and texture to music. In general, it is used as a rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment, with some melodic interventions, within a group.

The Peruvian musical culture is alive and constantly changing. It should not surprise us that, in this unremitting quest, new forms and uses for popular instruments contin-ue to emerge from time to time. The hatun charango (hatun means ‘big’ in Quechua, a native Peruvian lan-guage) is an instrument very similar to the ordinary charango, but larger, with a wider neck and six or seven orders of strings, which gives the pos-sibility to reach a deeper register and, therefore, a wider register, allowing new repertoires to be interpreted and assigning new musical functions to the instrument, with more similar results to those developed by a guitar, but with the chime that characterizes it. Several musicians and instrument makers have made contributions to this process. In recent times, the prominent Peruvian charango player Federico Tarazona has been engaged in disseminating this instrument, also making important contributions to its modern design, along with the luthier Fernando Luna.

* Musicologist, composer, and conductor.

PIECES FOR BASSOON BY PERUVIAN COMPOSERSToma Mihaylov and the Sofia Soloist. 2017.

Toma Mihaylov, the Bulgarian bas-soonist settled in Peru for more than twenty years, has released an album with pieces for bassoon by Peruvian composers. Professor Mihaylov has de-veloped many activities promoting the study of the bassoon and the composi-tion of pieces for this instrument. As a result of these efforts, and with the contribution of the exceptional and fa-mous musicians: “The Sofia Soloists”,

led by the important director Plamen Djouroff, a flawless album with works by Alejandro Núñez Allauca, Armando Guevara Ochoa, Edgar Valcárcel, José Sosaya, and Hugo Marchand has been recorded. The works included in the al-bum range from compositions for duos with piano, trios with oboe and piano, quartet of bassoons, to bassoon music and string orchestra. All the pieces cho-sen have recognizable Peruvian musical roots. The continuity of the Peruvian musical aesthetic in these formations of academic music and their projection towards the future are also part of this infinite process of sonic miscegenation that we live every day in Peru.

TRADITIONAL MUSIC AND SONGS OF CAÑARIS. Ministry of Culture of Peru. 2015.

As part of the collection called Chapaq Ñam, name of the network of Inca ro-ads that cross the Peruvian territory, the Ministry of Culture of Peru has is-sued a publication dedicated to rescue the musical traditions of the town of Cañaris, located in the mountains of the department of Lambayeque, at the top of the Andes. The inhabitants of Cañaris are mostly Quechua speakers of a regional variety of their own. Like

many ancient Peruvian settlements, they maintain very strong musical tradi-tions associated with different periods and social events, which are usually ac-companied by dances and parties. As a result of the arrival of modernity, some musical and social traditions are trans-formed, mutated or adapted to survive in a new context. Therefore, one of the functions of musicological research in Peru is to record in sound, graphic and literary documents the traditions that, at different times, are forming as a new corpus of social identity. The publication that we review consists of two compact audio discs, a digital vi-deo disc, and a booklet with a detailed

explanation of the historical, cultural, and geographical context of the town of Cañaris. This publication includes, in a first part, musical themes that are part of the local family and community life and, in the second one, the traditional instruments that are used. All the in-terpretations are by local people. The booklet also includes the transcription to Quechua of all the themes and its translation into Spanish.

Peruvian charango player, Federico Tarazona.

CHASQUICultural Bulletin

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

Directorate General of Cultural AffairsJr. Ucayali 337, Lima 1, PerúTelephone: (511) 204-2638

E-mail: [email protected]: www.rree.gob.pe/politicaexterior

The views expressed in the articles are those ofthe authors.

This bulletin is distributed free of charge by thediplomatic missions of Peru abroad.

Translated by:Business Communications Consulting

Mare Gordillo

Printing:Tarea Asociación Gráfica Educativa

CHASQUI 14

Teresina Muñoz-Nájar*

THE CONTRIBUTION OFTHE GUINEA PIG

For thousands of years, the noble Andean rodent - also called cuy, cobayo or guinea pig – whose meat is high in protein and low in fat- has been nourishing Peruvians. It is also a source of livelihood for hundreds of Andean

families and, chactado (cooked), stewed or spicy, a festive and celebrated asaz dish.Guinea pig meat is magical; tenuous, white, warm, silky, subtle, and mild -it is a culinary

prodigy. As if that were not enough, this meat is wrapped up with a thick, consistent and gummy skin that brings added emotions. That skin, with little promise to the naked eye and almost no charm when cooked or prepared on the grill, shows its splendor simply fried or chactada (chewed), following the traditional procedure of Andean cuisines». The quote is by the Spanish food critic, Ignacio Medina, who begins his column "The Magic of the Guinea Pig," published in the newspaper El País on January 15,2016. Like quinoa -another treasure of the Andes- the guinea pig is conquering hearts and markets every day.

Its history, like that of quinoa, goes back thousands of years. In his landbreaking book Alimentación y obtención de alimentos en el Perú prehis-pánico (Food and food procurement in pre-Hispanic Peru) (Instituto Nacional de Cultura, 2004. Second edition), Hans Horkheimer, archaeologist and researcher of Peru's past, points out that the land of origin of the guinea pig (Cavia porcellus; Cavia tschudi) is Peru. «Its name in Quechua -he writes- is quwe or akash, in Aimara, wanko, and in Akaro (ancient lan-guage, similar to the Aymara of the natives of Lima and the provinces of Yauyos and Huarochorí) is kiucho or uywa». And he continues: «Since the Spaniards were not familiar with this rodent before the conquest, they called it Indies rat or piglet (rata o cochinillo de Indias) but more often guinea pig. This last term became part of the Spanish lexicon, but the name Cuy predominates in Peru. Wild guinea pigs were domesticated by millions in the highlands, with some specimens even found in the homes of ordinary people. This promiscuity is still very frequent. In the coastal region, cuy breeding was less intensive and among the many interpretations of animals identified in the pre-Hispanic objects of the lowlands, depictions of guinea pigs are very rare. However, there are nu-merous remains in the ancient tombs and dumps».

Horckheimer led the Chan-cay Archaeological Mission in the 1960s and found a large number of cuy skeletons there. «The same thing happened to Arturo Jiménez Borja during the restoration of the Puruchuco ruins, who was able to identify a deep courtyard that was most certainly used as a hold for these rodents», he informs. «Among the thousands of decorated glasses studied in Chiclín in Lima» the researcher further states, «there are none that unequivocally reproduce guinea pigs. It is found, however, in Chimú and Mochica ceramics».

Archaeologists Guillermo Cock and Elena Goycochea wrote a book

Historia de la cocina peruana (History of Peruvian Cuisine), a collection of the lectures delivered at a seminar held at the Cultural Center of Spain from April 4 to 20, 2005 (compiler Maritza Villavicencio, co-publication of the Cultural Center of Spain and San Martín de Porres University, 2007). In it, they recount that in one of the two Inca cemeteries in Puruchuco, the one they excavated from 1999 to 2001, where they found a fardo (bundle) with a false head that later became famous with the name «The King of Cotton» they found a number of offerings: a bag with black bean pods, cuy skin, vessels of different sediments, and two bags of nets with red corn kernels. Cock and Goycochea analyzed the diet of the remains found (by analyzing the pre-served tissues) and asserted that in 5% of the funerary contexts, guinea pigs were the source of protein. «In the 2004 excavation -scientists said- what varies most is the proportion of land animal proteins. At this point, it should be noted that the guinea pig was also an important offering in the Mochica civilization (in the Uhle Platform of the Huaca de la Luna, for example).

On the other hand, many spe-cialists argue that guinea pig meat was more important in the diet of the ancient Peruvians than llama or alpaca meat. Hence, in issue No. 3 of the Arqueología and Antropología de la Universidad de San Marcos (2000), archeologist Lidio M. Valdez argued that few cuy bones were found in var-ious excavation in different sites, be-cause bones decompose with time or were eaten by dogs. «In order to verify how representative guinea pig bones

were -he explains-, an abandoned kitchen was partially excavated in the valley of Huanta, Ayacucho. In this facility, and following the traditional breeding practices, guinea pigs were raised for approximately forty years until the place was abandoned in the early 1980s, due to the actions of Shining Path and the militarization of the region. The results show that it became impossible to prove what kinds of guinea pigs were bred and consumed in the four decades in which such facility was used; only one guinea pig bone was recovered, along with others belonging to bigger animals». «This ethnoarchaeological observation shows that in order to better understand the relevance of guinea pigs in ancient Peru and to determine the archeozoological collections, it is necessary to carry out experimental studies, and only then will we be in a better position to reflect on the role of the guinea pig in ancient times», concludes the specialist».

He also wonders, "Why was cuy domesticated between 5000 and 3700 B. C.? ». According to him, it is worth noting that guinea pigs, without much care, have a high repro-duction rate, exceeded by few other animals; they begin to reproduce at three months of age and their gesta-tion period lasts between 63 and 74 days; the number of offspring varies, in general, between three and four; immediately after delivery, the female fetus goes into heat and may become pregnant while newborns do not need protection or breast milk; thus, the adult female can reproduce up to five times in a year. Finally, Valdez states «By improving our techniques

for recovering archaeological samples (for example, the use of screen boxes with mesh in millimeters), we will be able to better evaluate the role of guinea pig in ancient Peru, and as long as this does not happen, other-wise observations will simply be mere speculations".

The Conquest of CuyOne of the first descriptions of the guinea pig is made by José de Acosta in his Historia natural y moral de las Indias (Natural and Moral History of the Indies). He indicates that the Indians considered cuy «as very good food» and that in their sacrifices, they offered guinea pigs «very often». Garcilaso (1605) refers to guinea pigs in the following way: «There are domestic and wild rabbits, they are different from each other in color and flavor. Call them coy […]. The Indians, like poor people of meat, have a lot of them and eat them in great feast». Yet, it is the priest Cobo who provides us with a much more detailed painting of the small rodent because he tells us how it was cooked: «The guinea pig is the smallest of the meek, domestic animals that had the natives of these Indies had; they were bred inside their homes and in their own quarters, as they do today. The Indians eat this animal with the skin, peeling it as if it were piglet, and it is for them very gifted food; and they usually cook a stew with the whole cuy, having removed the belly, with a lot of chili and smooth river peb-bles, which they call calapurca, which means in the Aymara language, 'belly stones,’ because this stew is made with those belly pebbles of the guinea pig; which the Indians cherish much

The "chiri ucho," a typical Cuzco dish made with guinea pig and other ingredients for Corpus Christi. Photo: Andina.

Foto

: And

ina.«

CHASQUI 15

more than any other of the delicates-sen made by the Spaniards».

Doctor Fernando Cabieses un-covers why guinea pigs are called guinea pigs in Cien siglos del pan (One Hundred Centuries of Bread): «The cobayo (guinea pig) arrived in the Caribbean as a domestic animal, brought by the Spaniards from Peru, shortly after the conquest. From there, it was taken to Spain as a pet animal. As such, it soon arrived in Holland and England, where it was never accepted as food. To get to England, it followed the slave trade and stopped in Guinea, so it was nicknamed the guinea pig».

The statement «that it was never accepted as food» is apparently not that true. Cabieses himself tells us that in a cook book written in 1570 by Scappi, Pope Pius V’s cook, he gives instructions on how to cook it and it is said that «not only in Rome but in other Italian cities it was con-sidered a pleasant dish». And even if cuy did not have greater culinary success in other European countries, no one can refute Cabieses' assertion: «The good that this little animal has done to humanity by being used as a 'guinea pig' in all the most important experiments in bacteriology, pharma-cology, toxicology, infectious diseases, and genetics is incalculable. » «The health of the human race -says the doctor- is owed to the ancient Peruvi-an inhabitant who domesticated cuy early in its history. »

The significance of the Ande-an rodent in traditional Peruvi-an medicine is also noteworthy. Cleansing and clearing with guinea

pigs is an ancestral practice used to diagnose and cure diseases, besides absorbing impressions (scare, for example) and negative energies of patients.

21st Century CuyThe last National Agricultural Cen-sus, carried out in 2012, revealed that there are more than 12 million guinea pigs in Peru and that the regions with the greatest breeding are Cajamarca, Arequipa, Áncash, Cuzco, Junín, and Ayacucho. While Lima and Lambayeque stand out on the coast, Amazonas and Loreto stand out in the jungle.

At that time, we also learned that the technical management of guinea

pig breeding allowed to create micro and small businesses and that such businesses have been growing in recent years thanks to the availability of fodder resources. According to INEI, it is in the Peruvian highlands «where the largest number of guinea pig producers is concentrated; they rely on this species for their liveli-hood and food support and whose activity contributes to food security, empowerment of peasant women, and business development of many families».

Not for nothing did the National Agrarian University organize the Cuyese World Congress from October 11 to 15. One of the speakers was the Ecuadorian engineer Roberto

Moncayo, owner of the largest guinea pig farm in the world.

Cuy and Cooking The best way to eat guinea pig is the traditional way. Fried, roasted or chactado -it is served with head and legs which can be removed-, in a pot (spicy), and cooked in the oven. It should be tender if it ends up in the frying pan or roasted, and maltón if cooked as a stew. It should always sit for at least four hours. It is pertinent to mention an emblematic dish of the Cuzco cuisine: the «chiri ucho» (cold chili), a forceful proposal that is served, above all, at the Corpus Christi feast. It consists of a number of preparations: boiled chicken, chalona, flour tortillas, toasted corn, cheese, blood sausage, ochayuyo (algae), chorizo, cau cau (fish eggs), rocoto (chilly-like) and, in the place of honor, the tasty baked guinea pig. But, as Ignacio Medina rightly points out, whose words we used to begin this article, «there is no better way than the chactado. » He had one at La Glorieta restaurant in Tacna, and then gave us the recipe: «They heat a good amount of oil until it starts to smoke. It is then poured into a metal con-tainer and the cuy is put in opened up and with the skin facing upwards. The cuy is covered with a stone and left until the oil cools down, causing the meat to cook. Then the skin is sprinkled with crushed dried corn and fried again in very hot oil. The best part is the head; it is just a matter of overcoming one’s prejudice».

* Journalist and food researcher.

RECIPESCUY APANADO [Breaded Guinea Pig]IngredIents3 big guinea pigs1 cup breadcrumb 2 tablespoons ají panca chili pepper paste2 green chili peppers without veins and seeds, washed, cut into thin strips4 garlic cloves2 red large onions into julienne stripsred wine vinegar, olive oil2 oregano branches6 medium potatoes, boiled and peeledolive oil, salt1 small cup llatan (Arequipa sauce)

PreParatIonWash and air the guinea pigs for one hour. Cut them in four and place in brine for 15 minutes. Strain, add a little salt, pass the guinea pigs through the breadcrumb and brown them in plenty of oil until they are crispy. Simultaneously, brown the mirasol chili pepper paste and the chopped garlic in a saucepan with a jet of oil; add the green chili in strips and the onions until they are translucent; add salt, leafless oregano, three tablespoons of wine vinegar. Stir and reserve hot.At the same time, brown the boiled potatoes in a little oil or smearing them with an additional tablespoon of red pepper paste. Serve two pieces of guinea pig by diner, with a split potato, the hot onion sauce on top and some llatan on the side.

CUY CHACTADO [Fried Guinea Pig]IngredIents6 tender guinea pigs200g chochoca (dried corn, ground)1l pure vegetal oil, salt6 medium potatoes, boiled and peeled1 small cup llatan¼kg boiled fava beans

PreParatIonWash the guinea pigs with salted water and air for an hour. Pour a little salt and pass them through the ground corn. Fry them in a saucepan or large pan, in abundant hot oil and under an oval stone (pebble or chaquena that today usually has a wire handle). Fry on both sides and, when they are crispy, remove and serve with the potatoes, the llatan and a handful of fava beans.

CUY AL HORNO [Baked Guinea Pig]IngredIents6 tender guinea pigs3 tablespoons ají panca chili pepper½ white wine bottlewhite wine vinegar6 ground garlic, salt, cumin3 allspicesolive oil1 peppermint branch1 cup llatan6 medium potatoes, peeled½kg boiled fava beans1 dish green beans and carrots salad

PreParatIonWash the guinea pigs, air them and marinate them the day before with the chili, the garlic, the wine, two tablespoons of vinegar, the minced peppermint, salt, pepper and cumin. Grease a baking tray, arrange the guinea pigs and the potatoes, pour the mash, some oil and bake at 180ºC for thirty minutes or until they are cooked, sprinkling them with their juice. Serve with salad, potato, fava beans, and llatan.

PICANTE DE CUY (Ancash version) [Spicy Guinea Pig]2 guinea pigs6 boiled potatoes150g ground garlics200g ají panca chili pepper, groundSalt to taste, Oil

PreParatIonCut the boiled potatoes into halves or slices. Set aside.Cut the guinea pig (four or two pieces per guinea pig, depending on size).Season the guinea pig piece with salt and garlic.Fry the piece on both sides in very hot oil.Once the guinea pigs are fried, in the same pan add the boiled potatoes, the ají panca chili pepper with the ground garlic, plunging them into the dressing. Roast lightly this mix for 5 or 6 minutes. Serve accompanied by Creole sauce and white rice garnish.

Recipe from Libroderecetas.comRecipe by Paolo Caffelli

Cuy (Guineapig) Anonymous. Paris, 1890.

CHASQUI 16

IN THE LAND OF THE AMAZONAS (FEMALE WARRIORS)

Manuel Cornejo y Christian Bendayán*An all-embracing exhibition, a journey covering 150 years of photographs from the Peruvian Amazon.

The Amazon has been perceived as a feminine territory, not only because

of the legend of the indomitable Amazon female warriors, brought from the mythical European world but also by being perceived as a land of conquest and dream, fertile, and mysterious. A place where words had to be discovered to tally those unpublished images that seduced and terrified con-querors. This exoticization lived through centuries and landed in the new Republic.

In the 19th century, when photography first began in the Amazon, the possibilities it offered unfolded, both to fulfill a documentary role and to subli-mate that exotic and seductive imaginary of the jungle that came from our colonial heritage. The oldest photographs corres-pond to exploration mission to the Amazon region promoted by the State in the late 1860s. These contain portraits of indigenous people, including photographs taken in photo studios in the ca-pital and other cities around the country. Since then, it is possible to find splendid family studio portraits to tricked photographs that served -decades later- to de-nounce and defend the abuses committed by rubber workers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a phenomenon descri-bed by Jean Pierre Chaumeil as a "war of images". Nowadays, pho-tography has possibly played the most important role in forming a "Memoire of the Amazon," since

it not only understands what we consider real: the foundation of villages, dream landscapes, the everyday life of the jungle settler, the violence of the days, but also a certain construction of what was imagined, delirium, adventu-re, trying to seize the future and eternal and wild fiction.

The exhibition "In the Land of the Amazonas (Female Warriors)" brings together this 150-year journey of photography in the Peruvian jungle, a docu-mentary and artistic exploration as vast as this region, as complex as its history, and as diverse as its nature and culture.

* Researchers and curators of the exhibition "En el país de las amazonas" (In the Land of the Amazonas (Female Warriors).

Top left. Frank Gaudlitz. Naturaleza muerta con congompes. (Still life with congompes.) 2013.

Top right. Anonymous. Pampa Camona, Chanchamayo. Tricolor postcard edited by Eduardo Polack Schneider. circa 1901-1919. Richard Bodmer Collection.

Right. Carlos Meyer. Balsa de naturales, Perené. (Raft of naturals, Perene). Postcard edited by Luis Sablich. 1890. Source: Lima Metropolitan Municipal Library.

Bottom right. Nicolas Janowski. From the Liquid Serpent series.