Charlie Chaplin & the Attack of the Machine Men · Charlie Chaplin & the Attack of the Machine Men...

Transcript of Charlie Chaplin & the Attack of the Machine Men · Charlie Chaplin & the Attack of the Machine Men...

1

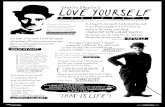

COLONIAL THEATRE 227 Bridge Street, Phoenixville, PA 19460 Tel: 610.917.1228 Fax: 610.917.0509 www.thecolonialtheatre.com

ILLUMINATING CINEMA: THE GREAT DICTATOR (1940)

Charlie Chaplin & the Attack of the Machine Men

By

Andrew Owen, PhD

For Chaplin, it supposedly began in 1937, when, writer, director and producer, Alexander Korda suggested that he make a film about mistaken identity, the two central characters being Adolf Hitler and Chaplin’s own ‘Little Tramp.’ After all, they both had the same sort of mustache. The toothbrush.

According to Chaplin, he didn’t think too much of the idea at the time it was suggested, even when Korda proposed that he, Chaplin, play both parts (Chaplin, 1964: 386). Of course, Korda wasn’t the only one who had noticed the resemblance between the hobo and the Fuhrer. For example, the April 21st issue of the British magazine The Spectator, looking beyond mere physical similarities, noted that both men were born in the same year, within a few days of each other in fact - Chaplin on April 16, 1889, and Adolf, a mere four days later, on the April 20th. The article also drew attention to a couple of other noteworthy parallels: firstly, the fact that both men possessed genius, was, to the article’s writer, at least, undeniable, and secondly, both were concerned with “the predicament of the ‘little man’ in society.”

Ultimately, Chaplin’s desire to work again (at this time in his career he was averaging a film every three to five years), as well as the opportunity to juxtapose the rhetoric of fascism, as presented by Hitler, with that of the theatrical tropes of burlesque and pantomime, was deemed too good to be missed. As Chaplin himself stated, “Hitler must be laughed at” (Chaplin, 1964: 387). However, this was before the outbreak of the Second World War. To both America and Britain, Adolf Hitler was the legal leader of a foreign nation, and therefore must be shown respect, irrespective of his actions or attitudes.

Indeed, in late 1938, the Head Secretary of the British Board of Film Censors (B.B.F.C.), Brook Wilkinson, had contacted Joseph Breen at the Hays Office in the U.S. to ascertain whether he knew what the basic outline of the plot of Chaplin’s film was, fearful that such a satirical attack on Hitler could cause a “delicate situation” to arise. Similarly, on October 31 of the same year, Dr. George Gyssling, the German Chief Consul, had also contacted Breen, again, like Wilkinson, attempting to ascertain what Chaplin’s exact intentions were, especially regarding the characterization of Hitler, adding that such a film would lead to “serious troubles and complications” (Gardner, 1987: 125-6). Breen promptly sent both communications to Chaplin, whose response has sadly not been recorded. However, he does acknowledge the difficulties in his autobiography, mentioning that the Hays Office had advised that such a film would have serious censorship difficulties, while the B.B.F.C. had stated that the film would probably be banned in

2

Britain. However, Chaplin was resolute, “determined to ridicule [the Nazis] mystic bilge about a pure-blooded race” (Chaplin, 1964: 388).

Of course, for some, this is the essential element of humor, stating that it is too banal an argument to dismiss comedy as something so simplistic as mere entertainment. To this way of thinking, humor is a specific form of deviance; a societal and cultural mechanism crafted to go against the norm in whatever its guise; be it moral, behavioral, or ideological. For example, George Orwell (1945) argues that humor must be vulgar, meaning that the comedian should not lazily wallow in obscenity or simple acts of immorality for their own sake, but should raise “topics which the rich, the powerful, and the complacent would prefer to see left alone.” For Orwell, true vulgarity is to be the “tiny revolution,” to confront topics and issues which those in power dread to hear discussed.

According to some, humor has the ability (perhaps we could even say “duty”) to discuss any subject, no matter how contentious it may be; indeed “nothing is so sacred, so taboo, or so disgusting that it cannot be the subject of humor” (Dundes & Hauschild, 1988: 56). As Freud (1905) argues, humor has been created by society to allow us to communicate our aggression over a topic, group or individual, while still conforming to the rules and laws of the environment. Simply put, why risk arrest by punching someone in the nose, when you could ridicule every aspect of their lives instead. Humor is that mechanism which allows us to voice our anger or dissatisfaction at something, no matter how difficult or painful that subject matter may be.

Such observations on humor seem to epitomize much at the core of Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940). Throughout the 1930s, Chaplin had become increasingly concerned with the state of world politics; epitomized by the rise of totalitarian regimes, personified by Stalin in the Soviet Union, Hitler in Nazi Germany, Mussolini in Italy, and Franco in Spain. Found scribbled on a folio notebook amongst Chaplin’s papers is a poem dedicated, “To a dead Loyalist soldier on the battlefields of Spain.” Its single stanza contemplating the sacrifice of life that the young must make for the political rhetoric of patriotism created by those that send them to such mindless slaughter.

“Prone, mangled form, Your silence speaks your deathless cause, Of freedom’s dauntless march. Though treachery befell you on this day And built its barricades of fear and hate Triumphant death has cleared the way Beyond the scrambling of human life Beyond the pale of imprisoning spears To let you pass.” (Quoted in Robinson, 1994: 486)

Chaplin had infamously communicated his views on patriotism to a reporter in 1931, describing it as, “the greatest insanity the world has ever suffered,” arguing that, if there was to be another war, “I hope they send old men to the front next time, for it is the old men who are the real criminals in Europe today” (Quoted in Robinson, 1994: 437).

3

The early decades of the twentieth century had seen Europe become seemingly engulfed in the twin furies of hate and intolerance; their destructive aim directed towards those racial and ethnic groups that were deemed different, and therefore morally and socially problematic, by national leaders; each of whom was busy wallowing in a self-satisfied stew of vitriolic patriotism. For Chaplin, they had turned the minds of humans into machines, the organic into the mechanical, crafting, through fear, a brutal willingness to destroy all that their leaders deemed inferior to the eugenic ideal.

“In training camps men were taught how to attack with a bayonet – how to yell, rush and stick it in the enemy’s guts, and if the blade got stuck in his groin, to shoot into his guts to loosen it.” (Chaplin, 1964: 223)

Chaplin had visited such subject matter before; his previous film, Modern Times (1936), focused on how the capitalist’s greed for greater profit would relentlessly drive the worker to merciless increased productivity, enslaving them to their position in the assembly line, before literally turning them into a machine whose sole reason for existence is to increase the monetary gain of their bourgeoisie master. It is an argument akin to that of Karl Marx in his text, The Grundrisse, written during the winter of 1857-58, but remaining unpublished until 1939,

“[Capitalism] gradually transforms the workers’ operations into more and more mechanical ones, so that at a certain point a mechanism can step into their places…Hence the workers’ struggle against machinery.” (Marx, 1939)

In The Great Dictator, Chaplin’s interests lay in exposing those mechanisms able to transform a human being, an entity capable of love and compassion, into a machine fashioned to kill, seemingly devoid of all remorse. In a short story entitled Rhythm: A Story of Men in Macabre Movement (1938), Chaplin used this concept by portraying a firing squad, ordered to execute an artist whose only crime was to publicly speak out against a political regime. The artist was a man that the members of the firing squad all loved and respected, whom they hoped would be reprieved. However, disciplined into a machine, each of them could not forestall their actions once the mechanism had been engaged – ready, aim, fire – even when the reprieve that they all hoped for had been granted.

“Six men each held a gun. Six men had been trained through rhythm. Six men, hearing the shout ‘Stop!’ Fired.”

Interestingly, in his autobiography, Chaplin seems to confess a certain level of remorse for using his humor to explore these elements, stating,

“Had I known of the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made The Great Dictator; I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis.” (Chaplin, 1964)

This sentiment seems antithetical to the argument concerning the essential quality of humor as described by Orwell and Freud. Obviously, it is not difficult to understand that laughing at the actions of the Nazis might be misconstrued as somehow effectively belittling the momentous inhumanity of their policies and undertakings. However, with all humility, I would argue that

4

Chaplin’s film is the more powerful and necessary because of the horrors perpetrated by the Nazis.

Antonin Obrdlik (1942) noticed that countries, such as Czechoslovakia, under Nazi occupation began to develop a form of humor deliberately crafted to undermine the oppressive regime that they instigated, while simultaneously succeeding in bolstering the morale of those they oppressed; effectively strengthening their desire to resist. Obrdlik referred to this style of humor as ‘gallows humor,’ noting that at the very instant that Czechs began to disappear inside concentration camps, this style of humor began to emerge. For example: A Gestapo officer asked an old Czech man whom he would rather work for, Germans or Czechs, without hesitation, the old man stated, “I would rather work for ten Germans than for one Czech.” When the Gestapo officer asked the old man his occupation, he replied, “Gravedigger.”

This form of humor has also been documented in Norway (Stokker, 1997), as well as in Nazi Germany itself (Hillenbrand, 1995), where the idea of Hitler’s impotency proved to be an unending source of comic inspiration,

“Question: Why does Hitler always hold his hands on his lower stomach just below the belt of his uniform? Answer: Because he wants to protect the last unemployed.” (Hillenbrand, 1995: 12)

Obrdlik concludes by saying that a society that incorporates a form of gallows humor demonstrates a “spirit of good morale” in which “the spirit of resistance of the oppressed peoples” is demonstrated; arguing that, “Its decline or disappearance reveals either indifference or a breakdown of the will to resist evil” (p. 712). This sentiment was echoed by W.E.B. DuBois (1926), who argued that, “all art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists.” DuBois states “in utter shamelessness” that all of his writing has been a form of propaganda designed to ensure that African-Americans gain the right of freedom and equality within a society, noting that the greatest danger is “when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.”

Consequently, Dubois’ work, like Chaplin’s film, reminds us of the oppressive nature of society and that one-sided propaganda, crafted and wielded by a powerful social group, can, if left unhindered, ultimately succeed in making the repression of a subordinate group seem both natural and justified; condemning the rest of society to a state of apathetic culpability.

Orwell (1945) argues that the comedian does not seek to degrade the world, but rather they attempt to remind their audience that the world is already degraded. This is the greatest accomplishment of Chaplin’s film - utilizing its humor to stand against a powerful regime that dominates and oppresses through fear. Such a regime, while supposedly working to strengthen society through the eradication of elements declared immoral, succeeds only in crafting a society of automatons, devoid of the basic facets of humanity. The Great Dictator, to paraphrase Chaplin’s final speech in the film, succeeds in reminding its audience that there are those that would seek to degrade the human condition; individuals possessed of unrelenting greed for monetary wealth and political power. Individuals who have “poisoned men’s souls,” who have “barricaded the world with hate.” Chaplin urges us to remember that instead of such “machinery, we need

5

humanity,” instead of cynicism and cleverness we need “kindness and gentleness,” the ability to help those in need, otherwise, “life will be violent and all will be lost.”

Bibliography

Chaplin, Charlie. 1938. Rhythm

Chaplin, Charlie. 2012 [orig. 1964]. My Autobiography. Brooklyn, New York: Melville House Publishing.

DuBois, W.E.B. 1996 [orig. 1926]. “Criteria for Negro Art.” The Oxford W.E.B. DuBois Reader. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Dundes, A. and Hauschild, T. 1988. “Auschwitz Jokes,” Chapter 3 in C. Powell, Humour in Society. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.56-65.

Gardner, Gerald. 1987. The Censorship Papers: Letters from the Hays Office 1934 to 1968. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead & Company.

Hillenbrand, F.K.M. (1995). Underground Humor in Nazi Germany 1933 -1945. London & New York: Routledge.

Marx, Karl. 1993. Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Middlesex: Penguin Books. Obrdlik,A.J. 1942. “Gallows Humor” – A Sociological Phenomenon,” in American Journal of Sociology 47(5): 709-16

Orwell, George. 1968 [Orig. 1944]. “Funny But Not Vulgar,” The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell, Vol. 3. Edited by Sonia Orwell & Ian Angus. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

Robinson, David. 1994. Chaplin: His Life & Art. New York, NY: Da Capo Press.

Stokker, Kathleen (1997). Folklore Fights the Nazis: Humor in Occupied Norway 1940-1945. Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press