Chapter 313 – RHEUMATIC FEVER - Wikispacesmop-unab.wikispaces.com/file/view/Chapter 313 -...

Transcript of Chapter 313 – RHEUMATIC FEVER - Wikispacesmop-unab.wikispaces.com/file/view/Chapter 313 -...

Use of this content is subject to the Terms and Conditions

Goldman: Cecil Medicine, 23rd ed.Copyright © 2007 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

Chapter 313 – RHEUMATIC FEVER

Alan L. Bisno

Definition

Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that occurs as a delayed, nonsuppurative sequela of upperrespiratory tract infection with group A streptococci. Its clinical manifestations include polyarthritis, carditis,subcutaneous nodules, erythema marginatum, and chorea in varying combinations. In its classic form, thedisorder is acute, febrile, and largely self-limited. However, damage to heart valves may be chronic andprogressive and cause cardiac disability or death many years after the initial episode.

Etiology

The development of acute rheumatic fever requires antecedent infection with a specific organism—the group Astreptococcus—at a specific body site—the upper respiratory tract. Cutaneous streptococcal infection, aprecursor of poststreptococcal acute glomerulonephritis, has never been shown to cause rheumatic fever.

Individual strains of group A streptococci vary in their rheumatogenic potential. In discrete epidemics of acuterheumatic fever in the United States, a limited number of group A streptococcal serotypes tend to predominate(e.g., 3, 5, 18, 24), and the infecting organisms are often heavily encapsulated, as evidenced by their growth asmucoid colonies on blood agar plates.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of acute rheumatic fever mirrors that of streptococcal pharyngitis. The peak age of incidenceis 5 to 15 years, but both primary and recurrent cases occur in adults. Acute rheumatic fever is rare in childrenyounger than 4 years, a fact that has led some observers to speculate that repetitive streptococcal infectionsare necessary to “prime” the host for the disease. No clear-cut gender predilection has been observed, althoughcertain manifestations, such as Sydenham's chorea and mitral stenosis, are more likely to develop in femalepatients.

The frequency with which acute rheumatic fever develops after untreated group A streptococcal upperrespiratory tract infection differs with the prevalence of highly rheumatogenic strains in the population and theepidemiologic circumstances. In the years after World War II, careful prospective studies were conductedamong personnel in military camps suffering from outbreaks of streptococcal infection; acute rheumatic feverdeveloped in approximately 3% of untreated patients. Among children with endemic exposure, attack rates areusually less than 1%. The magnitude of the antistreptolysin O titer increase, persistence of the infectingorganism in the pharynx, and clinically severe exudative pharyngitis are associated with a higher risk ofrheumatic fever; however, one third or more of cases occur after streptococcal infections that are mild orasymptomatic.

Patients with a history of acute rheumatic fever are susceptible to recurrent attacks after an immunologicallysignificant streptococcal infection. In one long-term prospective study of subjects with a history of rheumaticfever, one of every five documented streptococcal infections gave rise to a recurrence of the disease. The riskof recurrence is greater in patients with preexisting rheumatic heart disease and in those experiencingsymptomatic throat infections; the risk declines with advancing age and with increasing interval since the mostrecent rheumatic attack. Nevertheless, rheumatic patients remain at increased risk well into adult life.

Rheumatic fever occurs in all parts of the world, without any racial predisposition. In temperate climates, acuterheumatic fever peaks in the cooler months of the year, particularly in the winter and early spring. The majorenvironmental factor favoring occurrence appears to be crowding, as in military barracks or similar closedinstitutions and large households. Crowding favors interpersonal spread of group A streptococci and perhapsenhances streptococcal virulence by frequent human passage.

Acute rheumatic fever is common in developing areas such as the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, andmany nations of Africa. Extremely high acute rheumatic fever attack rates occur among indigenous populationssuch as the Maori of New Zealand and the Australian aborigines. In striking contrast, the incidence of acuterheumatic fever and the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease have declined both in North America and inwestern Europe during the 20th century. Rates of fewer than 2 per 100,000 schoolchildren are typical,especially in affluent suburbs. The higher incidence rates reported for blacks than for whites appear to be due tosocioeconomic rather than to genetic factors.

The mid-1980s, however, witnessed some startling developments in the epidemiology of acute rheumatic feverin the United States. Outbreaks of the disease were reported from many communities. The largest was in SaltLake City, Utah, and environs, where more than 500 cases occurred between 1985 and 2001. Equallysurprising was that in many of these outbreaks, the victims were predominantly white, middle-class childrendwelling in the suburbs. At the same time, epidemics of acute rheumatic fever occurred in military training basesin Missouri and California. Group A streptococci recovered from patients with acute rheumatic fever, theirfamilies, and the community and from training camp surveys were generally highly mucoid and belonged towell-established rheumatogenic serotypes (e.g., serotypes 3 and 18). These outbreaks demonstrate thatreemergence of rheumatic fever does occur and that appropriate treatment of underlying streptococcalpharyngitis is essential.

Pathobiology

The mechanism by which group A streptococci elicit the connective tissue inflammatory response thatconstitutes acute rheumatic fever remains unknown. Various theories have been advanced, including toxiceffects of streptococcal products such as streptolysins O and S, inflammation mediated by antigen-antibodycomplexes or streptococcal superantigens, and “autoimmune” phenomena induced by the similarity of certainstreptococcal and human tissue antigens (molecular mimicry).

Most authorities currently favor the theory that the tissue damage in acute rheumatic fever is mediated by thehost's own immunologic responses to the antecedent streptococcal infection. This theory is rendered morecredible by the demonstration of numerous examples of antigenic similarity between somatic constituents ofgroup A streptococci and human tissues, including heart, synovium, and neurons of the basal ganglia of thebrain. Taken together, these immunologic cross-reactions could account for most of the manifestations of acuterheumatic fever.

Patients with acute rheumatic fever have, on average, higher titers of antibodies to streptococcal extracellularand somatic antigens than do patients with uncomplicated streptococcal infections. Data relating to cellularimmunity are more limited. Patients with acute rheumatic fever exhibit an exaggerated cellular reactivity tostreptococcal cell membrane antigens, as demonstrated by in vitro inhibition of migration of peripheral bloodlymphocytes. During active rheumatic carditis, both the number of helper (CD4) lymphocytes and the ratio ofCD4 to CD8 cells are increased in heart valves and peripheral blood.

Several observations suggest that development of rheumatic fever may be modulated, at least in part, by thespecific genetic constitution of the host. These observations include the tendency of rheumatic fever to affectmore than one member of a given family, the fact that acute rheumatic fever develops in only a smallpercentage of all individuals experiencing an immunologically significant streptococcal infection, the tendency ofrheumatic individuals to experience recurrent attacks, and the propensity of rheumatic subjects to exhibitexaggerated immunologic responses to streptococcal antigens. To date, however, no consistent associationshave been demonstrated between specific class I or class II human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) andsusceptibility to acute rheumatic fever. A unique non-HLA alloantigen has been found to be strongly expressedon the B cells of virtually all patients with acute rheumatic fever but in less than 20% of controls.

Pathophysiology

Acute rheumatic fever is characterized by exudative and proliferative inflammatory lesions in connective tissue,especially connective tissue of the heart, joints, and subcutaneous tissue. The early lesions consist of edema ofthe ground substance, fragmentation of collagen fibers, cellular infiltration, and fibrinoid degeneration. In theheart, diffuse degeneration and even necrosis of muscle cells may be observed. At a slightly later stage, focalperivascular inflammatory lesions develop. These so-called Aschoff's nodules, considered virtuallypathognomonic of rheumatic fever, consist of a central area of fibrinoid surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma

cells, and large basophilic cells, some of them multinucleate. Many of these cells have elongated nuclei with adistinctive chromatin pattern, sometimes called caterpillar or owl-eye nuclei, depending on their orientation inmicroscopic cross section. Cells containing these nuclei are called Anichkov's myocytes, even though mostauthorities believe them to be of mesenchymal origin.

Cardiac findings may include pericarditis, myocarditis, and endocarditis. Foci of coronary arteritis may also beobserved. A thickened and roughened area (MacCallum's patch) is frequently present in the left atrium abovethe posterior leaflet of the mitral valve. Valvar lesions appear early as small verrucae along the line of closure (Fig. 313-1 ). Later, as healing occurs, the valves may become thickened and deformed, the chordae shortened,and the commissures fused. These changes result in valvar stenosis or insufficiency. The mitral valve isinvolved most commonly, followed by the aortic, the tricuspid, and very rarely the pulmonic valves.

FIGURE 313-1 Multiple verrucous vegetations along the line of mitral valve closure in a fatal case of acute rheumatic fever. (FromVirmani R, Farb A, Burke AP, Narula J: Pathology of acute rheumatic fever. In Narula J, Virmani R, Reddy KS, Tandon R [eds]:Rheumatic Fever. Washington, DC, American Registry of Pathology, 1999.)

On pathologic examination, the arthritis of acute rheumatic fever is characterized by a fibrinous exudate andsterile effusion without erosion of the joint surfaces or pannus formation. The subcutaneous nodules have manyhistologic features in common with Aschoff's nodules and consist of central zones of fibrinoid necrosissurrounded by histiocytes, fibroblasts, occasional lymphocytes, and rare polymorphonuclear cells. Inflammationof the smaller arteries and arterioles may occur throughout the body. Despite pathologic evidence of diffusevasculitis, aneurysms and thrombosis are not typical features of acute rheumatic fever.

Clinical Manifestations

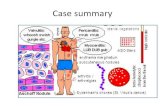

Rheumatic fever may involve a number of different organ systems, most notably the heart, joints, skin,subcutaneous tissue, and central nervous system, and the clinical picture is variable ( Table 313-1 ). Fiveclinical features of the disease are so characteristic that they are recognized as major manifestations according

to the revised Jones criteria (see later) for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever: carditis, polyarthritis, chorea,subcutaneous nodules, and erythema marginatum. Other nonspecific findings, including arthralgia, fever, andcertain laboratory findings, have been designated minor manifestations.

TABLE 313-1 -- THE MANY FACES OF ACUTE RHEUMATIC FEVER: POSSIBLE FEATURESHigh fever, prostration, crippling polyarthritisLassitude, tachycardia, new cardiac murmursAcute pericarditisFulminant heart failureSydenham's chorea without fever or toxicityAcute abdominal pain mimicking appendicitisVarying combinations of the above

The latent period between the antecedent streptococcal infection and the onset of symptoms of acute rheumaticfever averages 19 days and ranges between 1 and 5 weeks. When acute polyarthritis is the initial complaint, theonset is often abrupt and may be marked by high fever and toxicity. If isolated carditis is the initial manifestation,the onset may be insidious or even subclinical. Between these two extremes, diverse gradations exist in theinitial features of acute rheumatic fever (see Table 313-1 ). In most attacks, fever and joint involvement are theearliest clinical manifestations, although they may occasionally be preceded by abdominal pain localized to theperiumbilical or infraumbilical areas. At times, the location and severity of the pain as well as fleeting signs ofperitoneal inflammation may lead to a misdiagnosis of acute appendicitis. Carditis, if it is to appear, usually doesso within the initial 3 weeks of the illness. In contrast, chorea tends to occur later in the disease course,sometimes after all other manifestations have subsided. Chorea and polyarthritis rarely occur simultaneously.Epistaxis may be a feature of acute rheumatic fever occurring both at the onset and throughout the acute phaseof the illness; it may be severe.

The incidence of major manifestations varies in reported series. Overall, however, arthritis occurs inapproximately 75% of initial attacks of acute rheumatic fever, carditis in 40 to 50%, chorea in 15%, andsubcutaneous nodules and erythema marginatum in less than 10%. The frequency of individual manifestationsvaries with age. Carditis is more frequent in the youngest age groups and is relatively uncommon in initialattacks occurring in adults. Chorea occurs primarily in persons between the age of 5 years and puberty. It isseen more frequently in female patients and virtually never occurs in adult men. Thus, the majority of acuterheumatic fever attacks occurring in adults are manifested primarily by arthritis.

Arthritis

Joint involvement ranges from arthralgia alone to acute, disabling arthritis characterized by swelling, warmth,erythema, severe limitation of motion, and exquisite tenderness to pressure. The larger joints of the extremitiesare usually involved, most frequently the knees and ankles but also the wrists and elbows. The hips and smalljoints of the hands and feet are affected occasionally. Involvement of shoulders and lumbosacral, cervical,sternoclavicular, and temporomandibular joints occurs in a relatively small percentage of cases. The synovialfluid contains thousands of white blood cells, with a marked preponderance of polymorphonuclear leukocytes;bacterial cultures are sterile. Characteristically, the articular involvement in acute rheumatic fever assumes apattern of migratory polyarthritis. Migratory does not mean that inflammation in one joint disappears before thenext is attacked. Rather, a number of joints are affected in succession, and the periods of involvement overlap.Inflammation in one joint may subside while another is becoming symptomatic, so the process seems to migratefrom joint to joint. In untreated cases, as many as 16 joints may be affected, and arthritis develops in more thansix joints in about half the patients. This classic migratory pattern is not invariable, however; in some cases, thepattern may be additive, persisting in several joints simultaneously. When effective anti-inflammatory therapy isadministered early in the course of the disease, the involvement not infrequently remains monarticular orpauciarticular.

In most instances, inflammation in any one joint begins to subside spontaneously within a week, and the totalduration of involvement is no more than 2 or 3 weeks. The entire bout of polyarthritis rarely lasts more than 4weeks and resolves completely, with no residual joint damage. Some authors have described the rare

occurrence of Jaccoud's arthritis, so-called chronic post–rheumatic fever arthropathy of themetacarpophalangeal joints, after repetitive bouts of rheumatic polyarthritis. This entity is not a true arthritis buta form of periarticular fibrosis; its relationship to rheumatic fever remains unresolved.

Carditis

Rheumatic fever may involve the endocardium, myocardium, and pericardium ( Table 313-2 ), and thus thedisease is capable of inducing a true pancarditis. Carditis is the most important manifestation of acuterheumatic fever because it is the only one that can cause significant permanent organ damage or death.Although the clinical picture may at times be fulminant, it is more frequently mild or even asymptomatic and mayescape notice in the absence of more obvious associated findings, such as arthritis and chorea. The diagnosisof carditis requires the presence of one of the following four manifestations: organic cardiac murmurs notpreviously present, cardiomegaly, pericarditis, or congestive heart failure. In practice, the characteristicmurmurs of acute rheumatic fever are almost always present in cases of rheumatic carditis, unless the ability tohear them is obscured (e.g., loud pericardial friction rub, large pericardial effusion, low cardiac output, severetachycardia). The diagnosis of carditis should be made with caution in the absence of one of the following threemurmurs: apical systolic, apical mid-diastolic, and basal diastolic. Such murmurs, if they are destined todevelop, do so usually within the first week and almost always within the first 3 weeks of illness. (An exceptionto this rule may occur in patients with “pure” chorea; see later.)

TABLE 313-2 -- CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF CARDITIS IN ACUTE RHEUMATIC FEVERMurmurs [*]

Apical systolic

Apical mid-diastolic (Carey Coombs murmur)

Basal diastolic

Pericarditis

Cardiomegaly

Congestive heart failure

* At least one of the characteristic murmurs is almost always present in acute rheumatic carditis.

Certain patients with acute rheumatic fever have echocardio-graphic evidence of valvar regurgitation in theabsence of an audible murmur. Although valvar regurgitation can also be detected in normal individuals bytwo-dimensional echo-Doppler and color flow Doppler techniques, criteria for discriminating physiologic frompathologic regurgitation have been proposed by experienced investigators. At present, so-called echocarditis isnot considered diagnostic of rheumatic carditis for the purpose of fulfilling the Jones criteria, and its prognosticsignificance remains uncertain. The issue, however, remains controversial.

A number of different rhythm disturbances may occur during the course of acute rheumatic fever. By far themost common is first-degree atrioventricular block. Second- and third-degree heart block, nodal rhythm, andpremature contractions may also be observed; atrial fibrillation, on the other hand, is usually a feature of chronicrather than acute rheumatic involvement. Conduction disturbances do not in themselves indicate acute carditis,and their presence or absence is unrelated to the subsequent development of rheumatic heart disease.

Echocardiographic studies have demonstrated that in the absence of preexisting rheumatic valvar disease,patients with acute rheumatic fever and congestive heart failure have preserved left ventricular systolic functionbut mitral or aortic regurgitation or both. Thus, the etiology of heart failure appears to be valvar dilation and notmyocarditis.

In cases of acute rheumatic fever with severe carditis, areas of patchy pneumonitis are sometimes seen. Manyobservers believe that these pulmonary infiltrates represent a specific rheumatic pneumonia. The case isdifficult to prove, however, because of the confusion induced by such confounding clinical entities as pulmonaryedema, pulmonary embolization, superimposed bacterial pneumonia, and acute respiratory distress syndrome

in these severely ill and toxic patients.

Sydenham's Chorea (Chorea Minor, St. Vitus' Dance)

This neurologic syndrome occurs after a latent period that is variable but on average longer than thatassociated with the other manifestations of acute rheumatic fever. It frequently occurs in “pure” form, eitherunaccompanied by other major manifestations or, after a latent period of several months, when all otherevidence of acute rheumatic activity has subsided. In some cases of pure chorea, echocardiographic evidenceof subclinical valvar regurgitation may be present. Chorea is characterized by rapid, purposeless, involuntarymovements, most noticeable in the extremities and face. The arms and legs flail about in erratic, jerky,uncoordinated movements that may sometimes be unilateral (hemichorea). Facial tics, grimaces, grins, andcontortions are evident. The speech is usually slurred or jerky. The tongue, when protruded, retractsinvoluntarily, and asynchronous contractions of lingual muscles produce a “bag of worms” appearance. Theinvoluntary motions disappear during sleep and may be partially suppressed by rest, sedation, or volition.

Patients with chorea display generalized muscle weakness and an inability to maintain a tetanic musclecontraction. Thus, when the patient is asked to squeeze the examiner's fingers, a squeezing and relaxingmotion occurs that has been described as milkmaid's grip. The knee jerk may have a pendular quality. Nocranial nerve or pyramidal involvement occurs, and sensory modalities are unaffected. Theelectroencephalogram may display abnormal slow wave activity.

Emotional lability is characteristic of Sydenham's chorea and may often precede other neurologicmanifestations, with teachers and parents left puzzled over apparently inexplicable personality changes. Recentinterest has focused on the possibility that in a certain subgroup of children, obsessive-compulsive disorder ortic disorders may be triggered by streptococcal infections. Studies of this putative but unproven association,known as post-streptococcal autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococci (PANDAS),are continuing.

Subcutaneous Nodules

These nodules are firm, painless subcutaneous lesions that vary in size from a few millimeters to approximately2 cm. The skin overlying them is freely movable and not inflamed. The lesions tend to occur in crops over bonesurfaces or prominences and over tendons. Sites of predilection include the extensor surfaces of the elbows,knees, and wrists; the occiput; and the spinous processes of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae ( Fig. 313-2 ).Nodules are virtually never the sole major manifestation of acute rheumatic fever; they almost always appear inassociation with carditis, and the cardiac involvement in such cases tends to be clinically severe. Nodulesordinarily do not appear until at least 3 weeks after the onset of an attack and persist for several weeks. Theymay appear in repeated crops in patients with protracted carditis. Similar nodules may be seen in systemiclupus erythematosus and in rheumatoid arthritis. Subcutaneous nodules in the latter disease are larger andmore persistent than those in rheumatic fever.

FIGURE 313-2 Subcutaneous nodules over spinous processes on the back of a patient with acute rheumatic carditis. (Courtesy ofS. Levine, MD.)

Erythema Marginatum

The rash begins as an erythematous macule or papule and then extends outward while the skin in the centerreturns to normal. Adjacent lesions coalesce and form circinate or serpiginous patterns. The lesions may beraised or flat, are neither pruritic nor indurated, and blanch on pressure. They vary greatly in size and appearmostly on the trunk and proximal parts of the extremities, with the face being spared. The lesions areevanescent, migrating from place to place, at times changing before the observer's eyes, and leaving noresidual scarring. The erythema may be brought out by applying heat. Individual lesions may come and go inminutes to hours, but the process may go on intermittently for weeks to months uninfluenced byanti-inflammatory therapy. Its persistence is not necessarily an adverse prognostic sign. In most cases,erythema marginatum is accompanied by carditis; it also tends to be associated with subcutaneous nodules.

Diagnosis

No single laboratory test is diagnostic of acute rheumatic fever. Usually, leukocytosis with an increase in theproportion of polymorphonuclear leukocytes is observed. A mild to moderate normocytic, normochromic anemiais the rule. Evidence of acute inflammation is prominent, including elevated serum levels of C-reactive proteinand elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. An exception is pure chorea, which may appear afterindices of inflammation have returned to normal.

The urine may contain protein, white cells, and red cells. Biopsy studies have revealed a variety of renalabnormalities, but the classic proliferative glomerular abnormalities that characterize post-streptococcal acuteglomerulonephritis occur rarely in acute rheumatic fever. Electrocardiographic and radiographic studies mayreveal evidence of rhythm disturbances, pericarditis, or congestive heart failure. Two-dimensional echo-Dopplerand color flow Doppler echocardiography may document valvar dysfunction and pericardial effusion.

The major laboratory contribution to the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever is the documentation of recent groupA streptococcal infection. Throat culture should always be performed but is positive in only a minority of cases.The low rate of culture positivity remains unexplained, although it may be due in part to the time lapse of severalweeks between the onset of the pharyngeal infection and the throat culture. The serum titer of antistreptolysin Ois elevated in 80% or more of patients with acute rheumatic fever. If two streptococcal antibody tests (e.g.,antistreptolysin O and anti–DNase B) are performed, an elevated titer of at least one is found in 90% of patientswith acute rheumatic fever. The definition of an elevated titer varies, depending on the test used, the patient'sage, and the geographic locale. At times, serial sampling may detect an increasing titer of streptococcalantibodies in patients seen early in the course of a rheumatic attack.

Differential Diagnosis

Although acute rheumatic fever is readily recognized in individuals with multiple major manifestations or inepidemic circumstances, the disease may be extraordinarily difficult to diagnose with confidence at other timesbecause of the variability of its clinical features, the frequency with which only a single major manifestation isdetected, and the fact that no definitive diagnostic laboratory test is available. Nevertheless, precise diagnosis isespecially important in this disease because of the need to advise the patient about prolonged antimicrobialprophylaxis (see later). The diagnostic criteria of T. Duckett Jones, initially proposed in 1944 and subsequentlymodified by committees of the American Heart Association, attempt to minimize overdiagnosis andunderdiagnosis ( Table 313-3 ). The most recent (1992) revision specifies that the guidelines are designed toassist in the diagnosis of the initial attack of acute rheumatic fever, but they are also applicable to patientspresenting with recurrent polyarthritis or chorea. Two major manifestations or one major and two minormanifestations indicate a high probability of acute rheumatic fever if supporting evidence of recent streptococcalinfection is present. Although a positive throat culture or rapid antigen test for group A streptococci technicallysatisfies this requirement, streptococcal carriage rates as high as 15% may occur among school-aged childrenduring the fall and winter. Elevated titers of antibodies to streptococcal extracellular products, although notdiagnostic of acute rheumatic fever, do indicate a recent, immunologically significant streptococcal infection.

TABLE 313-3 -- GUIDELINES FOR DIAGNOSIS OF THE INITIAL ATTACK OF RHEUMATIC FEVER (JONESCRITERIA, UPDATED 1992) [*]

MajorManifestations Minor Manifestations

Supporting Evidence of Antecedent Group AStreptococcal Infections

Carditis Clinical findings Positive throat culture or rapid streptococcal antigen test

Polyarthritis Arthralgia

Chorea Fever

Erythemamarginatum

Laboratory findings Elevated or rising streptococcal antibody titer

Subcutaneousnodules

↑ Acute phase reactants

↑ Erythrocyte sedimentationrate

MajorManifestations Minor Manifestations

Supporting Evidence of Antecedent Group AStreptococcal Infections

↑ C-reactive protein

Prolonged PR interval

From Special Writing Group of the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of theCouncil on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young of the American Heart Association: Guidelines for the diagnosis ofrheumatic fever. Jones criteria, 1992 update. JAMA 1992;268:2069–2073, with permission. Copyright, 1992,American Medical Association.* If supported by evidence of preceding group A streptococcal infection, the presence of two major manifestations or one major and two

minor manifestations indicates a high probability of acute rheumatic fever.

The modified Jones criteria are only guidelines. They are most difficult to apply confidently when polyarthritis isthe single major manifestation. Under such circumstances, the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever should bemade only after the exclusion of other causes of polyarthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Still's disease, Lymedisease, viral arthritides (e.g., rubella, hepatitis B), the early prepurpuric phase of Henoch-Schönlein purpura,and septic arthritis including gonococcal arthritis. As experience grows, the echocardiographic demonstration ofvalvar insufficiency (by use of strict criteria to differentiate physiologic regurgitation) may help clarify thediagnosis in some cases. Echocardiography is of established value in the evaluation and management of acuteand chronic rheumatic heart disease.

Some patients have been described as manifesting polyarthritis that is atypical in time of onset and duration,does not respond dramatically to salicylate therapy, and is unassociated with other clinical features of acuterheumatic fever. Such individuals have on occasion been categorized as having “post-streptococcal reactivearthritis.” The existence of this entity as a distinct syndrome, however, and its relationship to rheumatic feverremain uncertain. Pending further clarification, such individuals should be considered to have acute rheumaticfever if they fulfill the Jones criteria and alternative diagnoses have been excluded.

Serum sickness is frequently a serious consideration, particularly if the patient has received penicillin or otherantibiotics for a preceding respiratory infection. Systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell hemoglobinopathies,and infective endocarditis may involve the joints and the heart. Other differential diagnostic considerationsinclude congenital heart lesions, viral and idiopathic forms of myocarditis and pericarditis, and functional heartmurmurs. Nonfamilial forms of chorea have been described in systemic lupus erythematosus, rarely inassociation with the use of birth control pills, and in patients with neoplasms involving the basal ganglia. Theinvoluntary jerks of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome may be confused with chorea. It remains uncertain how oftenepisodes of chorea occurring during pregnancy (chorea gravidarum) represent attacks of rheumatic fever. Otherdisorders that may at times be confused with acute rheumatic fever are gout, sarcoidosis, Hodgkin's disease,and acute leukemia.

In certain circumstances, acute rheumatic fever can be diagnosed even when the guidelines set forth in Table313-3 have not been met, provided that alternative diagnoses are excluded. Because of the long latent periodbetween the antecedent streptococcal infection and the appearance of the neurologic abnormalities in somepatients with Sydenham's chorea, evidence of inflammation encompassed in the minor manifestations may nolonger be present, and previously elevated antibody titers may have declined to normal. A similar situationoccasionally occurs in patients with indolent carditis, who may not come to medical attention until a prolongedperiod after the onset of the disease.

Treatment

Antibiotics neither modify the course of a rheumatic attack nor influence the subsequent development ofcarditis. Nevertheless, it is conventional to give a course of antibiotics designed to eradicate anyrheumatogenic group A streptococci remaining in the tonsils and pharynx to prevent spread of the organismto close contacts. The recommended regimens are those conventionally used for the treatment of acute

streptococcal pharyngitis ( Chapter 312 ). Benzathine penicillin G is preferred in non–penicillin-allergicpatients. After completion of this therapy, continuous antistreptococcal prophylaxis should commence (seelater discussion).

Treatment with anti-inflammatory agents is effective in suppressing many of the signs and symptoms ofacute rheumatic fever. [1] These agents do not “cure” the disease, nor do they prevent the subsequentevolution of rheumatic heart disease. They should be avoided in mild or equivocal cases because bysuppressing the clinical manifestations, they may obscure the diagnosis. The two drugs most widely usedare aspirin and corticosteroids. Aspirin is used in patients with acute polyarthritis, as long as carditis is eitherabsent or mild and no evidence of congestive heart failure is found. Aspirin is effective in decreasing fever,toxicity, and joint inflammation. It should be given in a dosage of 90 to 100 mg/kg/day in children and 6 to 8g/day in adults administered in equally divided doses every 4 hours for the initial 24 to 36 hours; thereafter, itmay be given in four doses during waking hours. Maintenance of a salicylate level of 25 mg/dL is usuallysatisfactory. The incidence of nausea and vomiting may be minimized by starting somewhat below theoptimal dosage level and gradually increasing during a few days. The patient should be observed forevidence of significant gastrointestinal bleeding and for signs and symptoms of salicylism (e.g., hyperpnea,tinnitus). After 1 to 2 weeks, the dosage is reduced to 60 to 70 mg/kg/day for an additional 6 weeks. Thesedosage schedules represent general guidelines only. The precise aspirin dose must be determined by thepatient's clinical response, blood salicylate levels, and tolerance of the drug.

Corticosteroids are generally reserved for patients who have severe carditis manifested by congestive heartfailure, who are unable to tolerate large doses of salicylates, or whose signs and symptoms areinadequately suppressed by aspirin. As with aspirin, the dosage must be individualized. Prednisone, 40 to60 mg/day in divided doses, may be used initially. After 2 to 3 weeks, it should be withdrawn slowly duringan additional 3-week period. In cases of fulminating carditis with profound heart failure, intravenouscorticosteroids may be used, and emergent valve replacement may at times be life-saving. As for otherpatients receiving corticosteroids, the physician should be alert to problems such as gastrointestinalbleeding, sodium and water retention, and impaired glucose tolerance. Suppression of the pituitary-adrenalaxis or the host immune system is a potential problem but not ordinarily a major one during this relativelyshort course of treatment. Although nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs would appear a reasonablealternative for patients who do not tolerate salicylates but do not require corticosteroids, there is a paucity ofdata on the use of these agents in acute rheumatic fever. Two small studies, one using naproxen and onetolmetin, reported nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs equivalent to aspirin in efficacy with fewer sideeffects. Further experience with these agents is required before specific recommendations can be made.

After cessation of anti-inflammatory therapy, clinical or laboratory evidence of acute rheumatic fever mayreappear. Such therapeutic “rebounds” occur more frequently after corticosteroid therapy than aftertreatment with aspirin. They may be minimized by prolonging salicylate therapy for 9 to 12 weeks and, whencorticosteroids have been required, by continuing aspirin for a month after corticosteroid use has beendiscontinued. Congestive heart failure is managed by conventional measures but with the recognition that inpatients without preexisting rheumatic heart disease, myocardial function is usually well preserved (seeearlier discussion). If digitalis is used, the potential risk of drug-induced arrhythmias in patients with activemyocarditis must be kept in mind. Patients with Sydenham's chorea require a quiet environment.Corticosteroids and sedatives such as phenobarbital or diazepam may be helpful. Trials of plasmapheresisand intravenous immune globulin in the management of severe and intractable chorea are currently inprogress.

Prevention

Primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever consists of accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment ofstreptococcal sore throat ( Chapter 312 ). Although straightforward in theory, primary prevention is oftenfrustratingly difficult to achieve. In many of the densely populated indigent communities in which the risk of

acute rheumatic fever is greatest, children with self-limited illnesses such as sore throats may never come tomedical attention, and throat culture services are usually unavailable to aid in diagnosis. Moreover, in one thirdor more of cases, acute rheumatic fever may arise after a clinically unapparent streptococcal infection.

Perhaps the most effective strategy for avoiding the mortality and chronic cardiac disability associated withacute rheumatic fever is that of secondary prevention. This strategy focuses on the group of persons who havealready suffered a rheumatic attack and who experience a high rate of recurrence after an immunologicallysignificant streptococcal upper respiratory tract infection. Recurrent attacks tend to be mimetic in nature, sopatients who have suffered carditis with their previous attack are likely to have repetitive cardiac involvementand progressive cardiac damage. However, carditis with recurrent attacks of acute rheumatic fever may developeven in patients who experienced only arthritis or chorea in their initial attack; thus, all patients who haveexperienced a documented attack of acute rheumatic fever should receive continuous antimicrobial prophylaxisto prevent either symptomatic or asymptomatic streptococcal infections. The specific regimens to be used areindicated in Table 313-4 . The most effective of these regimens is intramuscular benzathine penicillin G. [2]

Rheumatic recurrences are unusual in compliant patients receiving an injection every 4 weeks. In areas of theworld where the incidence of acute rheumatic fever and the risk of recurrence are high, however, injectionsevery 3 weeks provide more complete protection.

TABLE 313-4 -- SECONDARY PREVENTION OF RHEUMATIC FEVER (PREVENTION OF RECURRENTATTACKS)Agent Dose Mode

Benzathine penicillin G 1,200,000U every 4 wk [*] Intramuscular

or

Penicillin V 250 mg twice daily Oral

or

Sulfadiazine 0.5 g once daily for patients ≤ 27 kg (60lb) Oral

1.0 g once daily for patients > 27 kg (60lb)

For individuals allergic to penicillin and sulfadiazine

Erythromycin 250 mg twice daily Oral

From Dajani A, Taubert K, Ferrieri P, et al: Treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis and prevention of rheumaticfever: A statement for health professionals. Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease ofthe Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the American Heart Association. Pediatrics 1995;96:758.Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics.* In high-risk situations, administration every 3 weeks is justified and recommended.

The total duration of intramuscular or oral rheumatic fever prophylaxis remains unresolved. The risk ofrheumatic recurrence is known to diminish with increasing age and increasing interval since the most recentrheumatic attack. Patients who escape carditis during their initial attack are less likely to experience rheumaticrecurrences and are less susceptible to the development of carditis if a recurrence does ensue. These factssuggest that prophylaxis need not be perpetual for all rheumatic subjects. Recommendations of the AmericanHeart Association for the duration of secondary prophylaxis are listed in Table 313-5 . The decision to remove arheumatic subject from continuous prophylaxis should be an individualized one based on the physician'sassessment of the risk and probable consequences of recurrence and taken with the patient's informedconsent. Particular care should be taken with those at high risk of streptococcal acquisition (e.g., parents ofschoolchildren, schoolteachers, military recruits, nurses, pediatricians, and residents of areas with a highincidence of acute rheumatic fever). Patients taken off prophylaxis must be instructed to return immediately formedical follow-up whenever symptoms of pharyngitis occur.

TABLE 313-5 -- DURATION OF SECONDARY RHEUMATIC FEVER PROPHYLAXISCategory Duration

Rheumatic fever with carditis and residual heartdisease (persistent valvar disease [*] )

At least 10 yr since last episode and at least until age 40yr, sometimes lifelong prophylaxis

Rheumatic fever with carditis but no residual heartdisease (no valvar disease [*] )

10 yr or well into adulthood, whichever is longer

Rheumatic fever without carditis 5 yr or until age 21 yr, whichever is longer

From Dajani A, Taubert K, Ferrieri P, et al: Treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis and prevention of rheumaticfever: A statement for health professionals. Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease ofthe Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the American Heart Association. Pediatrics 1995;96:758.Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics.* Clinical or echocardiographic evidence.

Patients with rheumatic valvar heart disease must receive prophylaxis designed to avoid bacterial endocarditiswhenever they undergo dental or surgical procedures likely to evoke bacteremia. Such prophylaxis is notnecessary in a rheumatic subject who is free of residual heart disease. Regimens to prevent endocarditis (Chapter 76 ) are different from those prescribed for preventing acute rheumatic fever, and the fact that a patientis receiving rheumatic fever prophylaxis does not exempt that patient from endocarditis prophylaxis. Thisconcept is a frequent point of confusion not only among patients but among physicians and dentists as well.

Prognosis

The average duration of an untreated attack of acute rheumatic fever is approximately 3 months. The durationtends to be longer, up to 6 months, in patients with severe carditis. Less than 5% of patients have continuingrheumatic activity for longer than 6 months. In a few of these patients, the disease is limited to chorea and isotherwise benign. Other patients exhibit evidence of persistent inflammatory activity, including arthritis, carditis,and subcutaneous nodules. “Chronic rheumatic fever” occurs more frequently in patients who have had one ormore previous attacks; cardiac involvement in chronic rheumatic fever tends to be frequent and severe.

Congestive heart failure occurring in patients without preexisting rheumatic heart disease is not due tomyocarditis per se but rather to inflammatory valvulitis and annular dilation, accompanied in more severe casesby chordal elongation and mitral valve leaflet prolapse. Death from intractable congestive failure during theacute phase of acute rheumatic fever is rare. Once the acute attack has subsided, the only long-term sequela isthat of rheumatic heart disease, manifested primarily by scarring or calcification of the mitral and aortic valves (Chapter 75 ) and leading to insufficiency or stenosis. The prognosis from a cardiac standpoint is related to theclinical findings when the patient is initially seen. In one large study, for example, 347 patients were examinedduring an acute rheumatic attack and again 10 years later. Among patients who had been free of carditis duringtheir acute attack, only 6% had residual heart disease on follow-up. Patients with mild carditis during their acuteattack (i.e., apical systolic murmur without pericarditis or heart failure) had a relatively good prognosis in thatonly approximately 30% had heart murmurs 10 years later. About 40% of subjects with apical or basal diastolicmurmurs and 70% of subjects with heart failure or pericarditis during their acute attacks had residual rheumaticheart disease. The prognosis was worse in patients with preexisting rheumatic heart disease and in those whohad experienced recurrent attacks of acute rheumatic fever in the 10-year interval.

These data indicate that patients in whom carditis does not develop during an acute attack and who areprotected from recurrences of acute rheumatic fever are unlikely to suffer from rheumatic heart disease.Patients with pure chorea represent an exception to this rule. Some patients who have no evidence of carditiswhen they are initially examined may have rheumatic valvar disease on prolonged follow-up. Although theexplanation for this phenomenon is unknown, it is conceivable that in view of the long latent period associatedwith chorea, signs of carditis might have been present earlier but subsided by the time that the neurologicabnormality became evident. Moreover, echocardiographic studies have detected subclinical valvulitis in someof these patients.

Once the acute attack has subsided completely, the patient's subsequent level of physical activity depends oncardiac status. Patients without residual heart disease may resume full and unrestricted activity. It is importantthat patients not be subjected to unwarranted invalidism because of either their own inaccurate perceptions ofthe nature of the rheumatic process or those of parents, teachers, or employers.

Copyright © 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. - www.mdconsult.com

Bookmark URL: /das/book/0/view/1492/1119.html