Cezanne and Japonisme

-

Upload

priyanka-mokkapati -

Category

Documents

-

view

126 -

download

5

description

Transcript of Cezanne and Japonisme

Cézanne and "Japonisme"Author(s): Hidemichi TanakaReviewed work(s):Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 201-220Published by: IRSA s.c.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483720 .Accessed: 23/09/2012 07:58

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae.

http://www.jstor.org

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

Cezanne and Japonisme

1 Paul Cezanne and Japanese Art

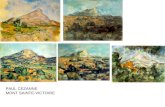

The exhibition Le Japonisme, held at the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais in Paris and the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo in 1988, represented a synthesis of current research into the influence exerted by Japanese art on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Western painting. Works by leading Impressionists or Post-Impressionists, including Manet, Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Degas, Cassatt, Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, Gaugin, Whistler and Denis, were displayed alongside others by a number of lesser artists, and it is interesting to note that the organizers also presented canvases by symbolist painters such as Moreau and Carriere. For the present writer, however, the most significant feature of the exhibition was the fact that this was the first time that a painting by Paul Cezanne, La montagne Sainte-Victoire et le Chateau-Noir (Rewald 939, circa 1904-06), was shown in the context of Japonisme.1 Although the catalogue entry by Genevieve Lacambre, while noting that Japanese art histor- ians had already pointed to the possible influence upon Cezanne of Hokusai's series Fugaku sanjurokkei [Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji], did not specify the precise source of this observation, in a private conversation Mme. Lacambre acknowledged that it was derived from my book Ex Oriente

Lux. Thanks to this book and an earlier article published in 1977, as well as the Japonisme exhibition held in 1988, the relationship between Cezanne and Japanese art has come to be more widely recognized.2

It was probably the German art historian Fritz Burger who first suggested, in 1913, the possibility of a link between Cezanne's paintings and Japanese prints in an article that noted the compositional resemblances between the French painter's bird's-eye view of L'Estaque aux toiles rouges and Utagawa Hiroshige's print of Arai from a vertical-format series of views of the Tokaido; Burger also mentioned the handling of space in Hokusai's print Shinshu Suwako [Lake Suwa in Shinano Province] as a key to understanding Cezanne's use of the "bird's-eye" viewpoint.3 Writing in 1955, Kazuo Fukumoto pointed out the connection between Hokusai's Fugaku sanjurokkei [Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji] and his three-vol- ume illustrated book Fugaku hyakkei [One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji] and Cezanne's series of studies of Mont Sainte- Victoire4, a relationship also suggested in 1951 by Pierre Francastel, who adopted the position that "what the Impressionists took from Japonisme was a confirmation of what they had already observed directly".5 In 1977 I published an article in Japanese entitled "Japonisme, Manet and Cezanne" at the request of Dr. Chisaburo Yamada, Director of

201

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

1) Paul Cezanne, ((La maison du pendu>, 1874, Musee d'Orsay, Paris.

the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo and the author of Ukiyo-e to Insh6ha [Ukiyo-e and Impressionism], who already knew my articles on the connections between Monet, Van Gogh and Japonisme, published in his museum's Bulletin

in 1971 and 1972.6 The present paper is based on those pre- vious articles, supplemented by more recent research.

In his Japonismus in der westlichen Malerei 1860-1920 (1979) Klaus Berger made some strong claims for the rela-

202

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

2) Utagawa Hiroshige, <<Takeuchi>> (from the series <<Sixty-Nine Stations on the Kisokaido Road,>), colour print, c. 1834-42.

tionship between Cezanne and Japanese art, not only proposing that Cezanne's paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire were stimulated by Monet's series of Haystacks, themselves influenced by Hokusai's landscape series, but also suggest- ing that Hiroshige's composition was close to that of Cezanne, citing Cezanne's LEstaque, effet du soir (Rewald 170, circa 1876), which he compared to Hiroshige's view of Futami Bay. Berger also made the unusual claim that in Cezanne's portraits of his wife her face bears a strong resem- blance to certain Ukiyo-e prints.7 Among Japanese researchers, in 1983 Shigemi Inaga wrote on the influence of Japanese landscape design on the French Impressionists, including Cezanne,8 while Akiko Mabuchi has expressed agreement with Berger's opinion that Cezanne learned from Monet as well as speculating that Cezanne's decision to embark on a series of paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire was partly prompted by Monet's attempts at a series on La gare de St-Lazare (1876), including the Haystack, the Row of Tall Trees and Rouen Cathedral.9 In an article for the catalogue of the Cezanne exhibition held at Yokohama Museum of Art in 1999, Hidenori Kuroda presented a survey of existing studies on the relationship between Cezanne and Japanese art, including recent work in Japan, particularly in relation to the watercolour painting of the Buddhist statue discussed later in this article,10 while Kimiko Niizeki has conducted similar research, citing not only similarities in composition but also

3) Utagawa Hiroshige, ((View of Kanbara>> (from the series <(Fifty-Three Stations on the Tokaido Road,), colour print, c. 1833-4.

issues concerning Western and Japanese artists' differing views of nature.11 In my own article I drew attention to the work of Pissarro, who lived in Pontoise, was interested in Hiroshige's prints and may have been instrumental in spark- ing Cezanne's interest in Ukiyo-e landscapes.

La Maison du pendu (Rewald 202, 1874) [Fig. 1], shown at the first Impressionist exhibition, held in 1874, is a solid painting with clear colours, quite distinct from the expressive style of Cezanne's first period. The composition, centred on a point in the middle distance marked by a bend in a slope and surrounded by houses and trees that draw the eye upwards to a high horizon topped by a clear blue sky, shows some affinities with Hiroshige's print of Takeuchi [Fig. 2] from the series Kisokaid6 rokujukyu tsugi [Sixty-Nine Stations on the Kisokaido Road]. Hiroshige's landscape, which is viewed from a high point, shares with Cezanne's the slope on the left- hand side and the horizon on the right. Niizeki noted that both artists used the same compositional device of oblique lines in the landscape, as seen in prints such as the View of Kanbara [Fig. 3] from the series T6kaido gojusan tsugi [Fifty-Three Stations on the Tokaido Road]: such views could easily be found at Auvers-sur-Oise, where Cezanne painted after 1872. In both 1872-3 and 1881 Cezanne painted landscapes incor- porating twisting roads (Rewald 490, Fig. 4), a subject also frequently selected by Hiroshige for his many series of views of Japan. Fukushima, for example, from the Kisokaid6 roku-

203

.- IJ . . 0 t -.

- * wt ',.

.^ * s , o.7" .W. A'.

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

5) Utagawa Hiroshige, <Fukushima, (from the series ((Sixty-Nine Stations on the Kisokaid6 Road,), colour print, c. 1834-42.

4) Paul C6zanne, <(Twisting Road,), c. 1879-82, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (R. 490).

juikyui tsugi [Sixty-Nine Stations on the Kisokaido Road] shows a section of the road near the station [Fig. 5] which is com- bined with trees in a manner reminiscent of Cezanne (Rewald 350, Fig. 6), while Hiroshige's print of Sugai from the same series also shows the road with one large tree in the centre [Fig. 7].

Cezanne was fond of compositions in which a tree is cut off by the frame of the painting, leaving the landscape visible through its branches. Le pin a I'Estaque (Rewald 55) and Auvers a travers les arbres (Rewald 39) both use this device, and compositions with trees in the middle foreground, such as Le Bassin du Jas de Bouffan (Rewald 1350) call to mind a number of Ukiyo-e landscapes including not only Sugai but also Hiroshige's View of Nakatsugawa from the same Kisokaido series. Hokusai had pioneered this type of compo- sition in his famous print Koshu Mishimagoe [Mishima Pass in Kai Province] from the earlier series Fugaku sanjirokkei [Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji]. Again, the unusual composi- tion of Cezanne's La vue de Paris (Rewald 503) with the roof occupying half of the foreground, is often seen in views of the Sumida River in Edo by both Hokusai and Hiroshige. Already a skilful painter, Cezanne renewed his style in the light of his study of the unique compositions and colours of Ukiyo-e

prints, thus overcoming the expressionist tendencies of his early period.

2 Why Did Cezanne Criticize the Techniques of Ukiyo-e?

One document which is central to our understanding of European enthusiasm for Japanese art is the art-critic Ernest Chesneau's 1878 essay in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, which describes the situation in Paris at the time of the Exposition Universelle held in that year:

"Lenthousiasme gagna tous les ateliers avec la rapidite d'une flamme courante sur une piste de poudre. On ne pou- vait se laisser d'admirer I'imprevu des compositions, la science de la forme, la richesse du ton, I'originalite de I'effet pittoresque, en meme temps que la simplicite des moyens employes pour obtenir des tels resultats... II s'est forme ainsi depuis cette date deja lointaine jusqu'au moment present de belles et rapides collections entre les mains de M. Villot, I'an- cien conservateur des peintures au Louvre, des peintres Manet, James Tissot, Fantin-la-Tour, Alphonse Hirsch,

204

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

7) Utagawa Hiroshige, <<Nakasegawa> (from the series <<Sixty-Nine Stations on the Kisokaid6 Road>,), c. 1834-42.

6) Paul Cezanne, (<Le bassin du Jas de Bouffan,, (R. 350).

Degas, Carolus Duran, Monet, des graveurs Bracquemond et Jules de Jacquemart, de M. Solon de la manufacture de Sevres, des ecrivains Edmond et Jules de Goncourt, Champfleury, Philippe Burty, Zola, de I'editeur Charpentier, des industriels Barbedienne, Christofle, Bouilhet, Fallze; des voyageurs Cernuschi, Duret, Guizet, F. Regamey. Le mouve- ment etant donne, la foule des amateurs suit."12

Not only painters like Manet, Degas and Monet, but also writers like the Goncourts and Zola were considered as japoni- sants. Emile Zola in particular, who was of course an intimate friend of Cezanne and played an important part in his artistic development, once wrote of Manet:

"II serait beaucoup plus interessant de comparer cette peinture simplifiee avec les gravures japonaises qui lui ressemblent par leur elegance etrange et leurs taches magnifiques,"13

while Cezanne's mentor Camille Pissarro was also fond of Japanese paintings, as was Monet, the only painter whom Cezanne really respected, saying of him that he was "the

strongest" among all of them and that his work "must enter the Louvre". Monet had such a deep interest in Japanese art that Cezanne could hardly have failed to feel its effects, if only at second hand.14 Cezanne also expressed his appreciation of the Goncourts in the following terms:

"II est malheureux de ne pouvoir faire beaucoup de spe- cimens de mes idees et sensations, vivent les Goncourt, Pissarro, et tous ceux qui ont des propensions vers la couleur, representative de lumiere et d'air."15

Zola's leading role in the study and promotion of Cezanne's art has tended to obscure the important part also played by Edmond de Goncourt, and it is reasonable to sug- gest that Cezanne's awareness of Japanese art was nurtured not only by his painter friend Pissarro but also by de Goncourt, who was, of course, one of the most active promoters of Japanese art, writing books on both Hokusai and Utamaro. Given Cezanne's personal circumstances it is only to be expected that he would have been deeply involved in the study of Japanese art, but most Cezanne scholars have neglected this aspect of his formation, choosing instead to

205

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

. -. .. ' _

j,. ' r -:

,/

isl

i; q a

I. ii

r,.5? ,9?!EQ I-

r 14

?*t a;lp k C5 '.

*,,

,:-

8) Watanabe Seitei, ((The Beauty of Nature,,, private collection, Tokyo.

cite a conversation with Joachim Gasquet or Emile Bernard in which he expressed a negative opinion:

"Ou bien, les plus sommaires, les Japonais, vous savez, ils cement brutalement leurs bonshommes, leurs objets, d'un trait brut, schematique, appuye, et en teintes plates on remplit jusqu'au bord. C'est criard comme une affiche, peint comme au pochoir, a I'empote-piece."16

The Cezanne scholar John Rewald passes over this point in total silence17 even though the artist's comments at least make it clear that he was sufficiently familiar with Japanese prints to be able to criticize them so harshly. Cezanne once remarked to Bernard:

"D'un autre cote les plans tombent les uns sur les autres, d'ou est sorti le neoimpressionisme qui circonscrit les

contours d'un trait noir, defaut qu'il faut combattre a toute force."18

In deploring the black outlines of "neo-impressionisme", Cezanne had pinpointed the very feature which most strongly reflected the influence of Ukiyo-e.

Gasquet's report of a conversation with Cezanne about Japanese art is particularly revealing. The painter said that he had "only" read two books by the Goncourts on Utamaro and Hokusai, adding that "to the creative intelligence of an artist, a hundred pages do not succeed in revealing as much as one line of a drawing or a small brushstroke".19 Since Ukiyo-e prints (other than illustrated books featuring reproductions of paintings) do not normally show drawing or brushstrokes, but lines engraved in the block, it seems unlikely that Cezanne had not seen Ukiyo-e paintings as well, and at the very least

206

3r^ Z 1 -. . y

I$`

?. .

t ..

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

9) Paul C6zanne, <<St. Victoire,, watercolour, (R. 634). 10) Paul C6zanne, <<St. Victoire>,, (R. 912).

Gasquet's words indicate that he had studied Edmond de Goncourt's two books on Utamaro (1891) and Hokusai (1896), both of which give details of the techniques of Japanese print- making.

It cannot be denied, however, that one of Cezanne's prin- cipal artistic innovations was the denial of the value of outline, in other words the very technique which lends Ukiyo-e prints much of their character. Cezanne gave expression to this denial in the famous words which he addressed to Bernard in 1904:

"Traitez la nature par le cylindre, la sphere, le cone, le tout mis en perspective, soit que chaque cote d'un objet, d'un plan, se dirige vers un point central."20

According to Cezanne's theory, the cylinder, the sphere and the cone are always to be represented on the surfaces of objects by "taches" rather than lines. The idea of eliminating lines represented nothing less than a negation of traditional academic teaching as it had been practised since the time of Vasari, who had laid such emphasis on the importance of drawing, but this critique of a particular aspect of Japanese prints, termed "cloisonnisme" in the case of Gauguin, did not necessarily imply the denial of all Japanese artistic methods.

"II y revenait sans cesse: 'Je n'avait qu'une petite sensa- tion. Monsieur Gauguin I'a volee!' II admirait pas beau-

coup, lui qui fait un tel novateur, les decouvertes et les systematisations en peinture."21

Cezanne was always negative towards Gauguin but this was simply because the latter had "stolen" his ideas. Of course Cezanne's words express his contempt for Gauguin, but they also imply that Gauguin was using a technique that both he and Cezanne had learned from Ukiyo-e. In fact, Cezanne was aware not only of Ukiyo-e, but also of another type of Japanese painting shown at the great expositions held in Paris during the closing decades of the nineteenth century. Because of his mother's illness he spent most of the year 1878 in Provence, dividing his time between Aix and I'Estaque, but a letter of 29 July 1878 suggests that he had taken the trouble to visit Paris and may have viewed the Exposition Universelle which had opened in May of the same year.

"Avant de quitter Paris, j'ai laisse la clef de mon apparte- ment a un nomme Guillaume, cordonnier. Voici ce qui a du se passer; ce gargon a du recevoir des provinciaux a cause de I'Exposition et les a loges chez moi."22

In this letter addressed to Zola, whose main purpose was to congratulate the novelist on the purchase of a summer house and garden at Medan outside Paris, Cezanne did not

207

? '. - .: ':;" .

? , . . . . ': .

-' ,f':l . .. _ '*^^j^BH|^ l; _ __S_ .n

^sf'I^H^^fS _fS^Br" ,

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

//

'S~~~' ( )?

at rIK~J*L.

P.

I

.1

Iv

,s,! N*

11) Paul Cezanne, <L'6tude d'apres un monm c. 1880, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen,

It

1&'

i Rotterdam.' .

12) A figure of the deity Idaten, Mus6e Guimet.

t'! a

ument assis,,4 Rotterdam.

12) A figure of the deity Idaten, Musee Guimet.

208

I

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

give an account of the exhibition but this does not necessari-

ly mean that he did not see it, nor that he was not impressed, as had been Chesneau and Goncourt, by the Japanese paint- ings on display. It is worth noting that the Japanese section of the display on the Champs de Mars did not include any prints, despite the fact that these were in such high regard in Europe; nevertheless it was very popular, as Chesneau reported excit- edly in his article for the Gazette des Beaux-Arts23 and Goncourt too greatly admired the Japanese display, especial- ly the "partitions" and the folding screens.24

What would Cezanne have seen at the 1878 Exposition? I think it is likely that he encountered not only examples of Japanese craft but also paintings in a quite different style: sumi-e or ink paintings, in particular works by Watanabe Seitei (1852-1918), who was awarded a bronze medal. A pupil of Kikuchi Y6sai (1788-1878), an eclectic artist and one of the most famous painters of the later Edo Period (1615-1868), Seitei had studied both traditional Japanese and Western tech- niques and as we can see from the work reproduced here [Fig. 8] did not draw the outlines of objects but instead painted their surfaces with the brush. Chesneau, who visited the Japanese section, admired the painting of "I'Ecole Sumie" and wrote:

"Lecole Sumie peint exclusivement a I'encre de Chine, en traits hardis, rapides, sommaires, precis, caracteristiques, jetes avec une suirete de main incomparable, une science du dessin merveilleuse, une verve, une legerete, un esprit et une grace qui dans I'oeuvre de son grand maitre Oksai atteinent au genie. C'est a I'admirable ecole Sumie, ou ecole croquis, que s'alimente I'art industriel japonais tout entier..."25

Chesneau was not aware of the use of colour in sumi-e, nor did he realize that Hokusai ("Oksai") was not in fact espe- cially well known as a master of this particular genre, but with- out mentioning Seitei's name he showed a genuine apprecia- tion of sumi-e technique. Cezanne, too, must surely have appreciated the value of this novel mode of painting.

According to the Goncourt Journal, in 1878 Matsukata Masayoshi, one of the Japanese representatives at the Paris Exposition Universelle, organised at least three demonstra- tions of Japanese traditional painting by Japanese artists, the first at his own house, the second at Charpentier's and third at Burty's. It is apparent from Edmond de Goncourt's description of the techniques they used that they did not demonstrate Ukiyo-e painting but instead worked in sumi-e style with "Chinese" ink. Goncourt was full of praise for their skill in drawing without line and contours and yet still suc- ceeding in expressing volume and "valeur" (strength of

colour and light and shade).26 Cezanne's watercolours show that he too was capable of achieving such effects [Fig. 9] and as already noted above he observed in one of his letters "D'un autre c6te les plans tombent les uns sur les autres..."27 Cezanne made particular use of this technique in his views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, placing one light colour upon another without contours or line in a manner akin to watercolour painting [Fig. 10]. In this respect, at least, it can be argued that his technique is similar to Japanese sumi-e. Goncourt does not give details of the guests who were invit- ed to the three demonstrations but of the two French hosts, Georges Charpentier (1846-1905) was the publisher of Emile Zola's novels while Philippe Burty (1830-90) was a well known art critic who wrote the introduction to the catalogue of the Impressionist exhibition in 1874; both men were included in Chesneau's list of japonisants, quoted above. At the time of the demonstrations Cezanne was not in Paris but in I'Estaque; nevertheless it is possible that he heard about them from Zola.28

One of the demonstrators at Matsukata's and Charpen- tier's residences was Yamamoto H6sui (1850-1906), who came to Paris in 1878 on the occasion of the Exposition Universelle with the intention of studying Western-style paint- ing as well as introducing Japanese cuisine to France; in his first year abroad he also exhibited landscape paintings in tra- ditional techniques.29 Goncourt mentions another Japanese artist whom he met at Charpentier's and Burty's, Watanabe Seitei, already mentioned above, who also came to Paris for the Exposition and was one of the most famous famous ink- painters in Japan as well as being one of the first traditional- style painters to visit Europe. Apart from the fact that he used ink while Cezanne painted in oils, his style, with its smooth surfaces without outlines, is sometimes very close to that of Cezanne [Fig. 8]. It is interesting to note that Cezanne's style underwent a change in that very same year, 1878, in favour of simple forms sketched with the brush.

At Matsukata's house, Goncourt also met Hayashi Tadamasa, who was in Paris for the Exposition and assisted Goncourt in his study of Japanese art. In a journal entry dated 9 May 1886, Goncourt records his admiration for some draw- ings of fish and birds by Yamamoto Baiitsu (1783-1856) which had been recommended to him by Hayashi. Goncourt owned eight kakemono [hanging scrolls], one of dogs by Maruyama Okyo (1723-1795), second, by Kishi Ganku (1749-1838), third, by Mori Sosen (1749-1821), fourth, depicting flowers, by Ogata K6rin (1658-1716), and others by Kan6 Soken (d. 1697), Yukinobu (d. 1699), Kikuchi Y6sai and Tani Bunch6 (1763- 1840). All had been purchased from Hayashi's shop, which opened in 1883.30

209

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

_ ?' .r / ,I I -

I-

,I:

c? r *

p., 5 b?I .4?

t,?k .s r ?IS .-r_. cii

P1 i?

"c: =?

?-

- _ _ J

13) Katsushika Hokusai, illustration from (<A Quick Guide to Drawing,, 1881.

If Cezanne had not observed this type of painting at Goncourt's house, he could have seen kakemono belonging to Zola. According to the catalogue of an auction held after his death, the novelist owned six scroll paintings31 which Cezanne could have studied at one of the gatherings held every Thursday at Zola's house.32 In short, it is very unlikely that Cezanne had not seen Japanese ink paintings: even with- out documentary evidence, his technical innovations are enough to suggest that he had been exposed to the tech- niques of traditional ink painting. This is apparent not only from his compositional practice but also from his way of apply-

14) Katsushika Hokusai, illustration from <(A Quick Guide to Drawing,,, 1881.

ing paint in both oils and watercolour: the flat, smooth sur- faces of the rocks and trees that show the unmistakable influ- ence of sumi-e.

3 C6zanne's Painting of a Statue of the Buddha

Cezanne's interest in the Japanese artefacts in Zola's pri- vate collection is demonstrated by his watercolour of a Japanese Buddha, Letude d'apres un monument assis [Fig. 11], executed around 1880 and preserved in the Museum

210

.. . -- .-- . - - . I l.

ji ...... I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

__ _ __C ?r I

* . .._%-

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

't-, -Jk

tip. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ) J )

1* ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ?F~Y *f

/

..

/-

- . ..

I J;1 teI

It rij r

. v S

*.1f -

ii . ,[

0

15) Katsushika Hokusai, illustration from (A Quick Guide to Drawing,,, 1881.

Boymans-Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. Showing a front view of the image, seated on a dais with its hands joined together in prayer, the sketch is drawn in pencil with most of the figure painted in light yellow with areas of brown.33 The catalogue of the former Koenigs collection describes it as a "Statue of a Chinese Deity", while Venturi, who compiled the first general catalogue of Cezanne's works, called it a "monument funeraire", an identification which has been generally accepted ever since without further investigation.34 In fact, the Etude def-

16) Katsushika Hokusai, illustration from <A Quick Guide to Drawing,,, 1881.

initely depicts a Buddhist image, most likely a figure of the deity Idaten [Fig. 12], one of the eight generals associated with Zoch6ten, one of the four Tenn6 [heavenly kings] who protects the Buddha against evil influences emanating from the south- ern quarter. He is normally shown as a standing figure, dressed in Chinese-style armour and offering up a sword that rests on his arms which are held out in a prayerful gesture. Figures of Idaten were often placed in the kitchens of Zen temples. Comparing images of Idaten with the Etude, one notices that Cezanne does not show Idaten in his complete form: he lacks the halo and sword, but there is a grimacing lion mask on his

211

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

17) Paul C6zanne, c(Marronier du Jas de Bouffan en hiver,, 1883-86.

abdomen which is similar to that seen on the original sculp- tures.35 There is no doubt that Cezanne saw this figure in Zola's house, since it is listed in the catalogue of his property compiled after his death in 1903,36 and is also visible in a pho- tograph of Zola in his study preserved in the Musee Zola, in which two Buddhist figures can be seen behind the novelist.37

Cezanne's understanding of some of the fundamental teachings of Buddhism is demonstrated by the following remark he made to Gasquet:

"La nature parle a tous. Eh bien! Jamais on n'a peint le paysage. L'homme absent, mais tout entier dans le pay-

212

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

18) Katsushika Hokusai, ccHodogaya), (from the series <<Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji))), colour print, c. 1829-33.

sage. La grande machine bouddhiste, le nirvana, la consolation sans passions, sans anecdotes, les couleurs! II n'y aurait qu'a accumuler, a se laisser fleurir ici. Cette terre vous porte..."38

His concept of Buddhism was related to his notion of the worship of nature, an idea which is fundamental to Japanese Buddhism, especially when assimilated to the beliefs of Japan's native religion, Shinto. How did he learn about Buddhism? There is no doubt that he moved in japonisant cir- cles even though he had very little to say himself about

Japonisme, but he did make the following observation in a let- ter to his son:

"Lidee si saine, si reconfortante et seule juste d'un deve- loppement d'art au contact de la Nature."39

This idea of the spirit of nature corresponds closely with that of much Japanese painting, as noted by Gustave Geffroy in an essay on Cezanne which, according to a letter by Monet of 23 November 1894, enjoyed the artist's general approval. Geffroy also expressed his admiration for

213

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

19) Paul C6zanne, (Mont Sainte-Victoire vue de Bellevue), 1886-8.

Japanese art in an article on Japanese landscape painting in Le Japon Artistique of 1892,40 while Emile Bernard records Cezanne's interest in the issue of outlined form, alluded to above:

"'Oui, comme ga j'ai une vision nette des plans!' Les plans! C'etait sa continuelle preoccupation. 'Voila ce que Gauguin n'a jamais compris', insinuait-il. Je devais aussi pour beaucoup prendre ma part de ce reproche et je sen- tais que Cezanne avait raison, il n'est pas de belle peintu- re si la surface plane reste plate, il faut que les objets cou- rent, s'eloignent, vivent. C'est la toute la magie de notre art."41

Cezanne was opposed to Gauguin's "cloisonnisme", by which he meant that Gauguin's outlined surfaces were exces- sively flat, and he applied the same criticism to Ukiyo-e, as noted above in his remarks to Gasquet. But as I have already suggested, his emphasis on the expression of the surface without the use of contours was an idea that he may have taken from Japanese ink painting.

There is no doubt that other artists in Cezanne's circle were much taken with Ukiyo-e. His mentor Pissarro said, "Hiroshige is an excellent impressionist and Monet, Rodin and

20) Katsushika Hokusai, (<Lake Suwa in Shinano Province, (from the series <<Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji>,), colour print, c. 1829-33.

I were fascinated by him... these Japanese artists deepened our confidence in our vision..." (27 February 1893) and in fact Cezanne's painting method was similar to that of Ukiyo-e in its use of primary colours. Bernard observed C6zanne"s palette in his studio in Aix:

"II n'en est pas de meme de celle des Impressionnistes qui, par son arret au bleu, cree I'impuissance du noir et aussi I'absence de chaleur dans I'ombre. On peut arriver a tout le relief desirable, il est vrai, avec le blanc et le noir seuls; mais alors c'est au prix de I'absence de coloris. En adjoignant au blanc et au noir les trois couleurs primaires, soit le rouge, le bleu, le jaune, on se dirige deja vers une gamme chantante, mais le grand nombre d'alterations que I'on fait subir a ces couleurs fondamentales leur enlbve leur fraicheur, et on perd alors en intensite et en eclat ce que I'on peut gagner en harmonie et en intimi- te."42

This description could be interpreted as meaning that Cezanne's painting style incorporated both the watercolour technique of Japanese painting and the colour structure of Ukiyo-e, enhancing the effect of his coloured surfaces by the use of visible brush strokes and subtle contours [Fig. 11].

214

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

4 Why Did Cezanne Paint Thirty-Six Views of Mont Sainte-Victoire?

Cezanne painted exactly thirty-six oil paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire (a figure confirmed by John Rewald's recent catalogue)43, coinciding in a sense with Hokusai's thirty-six views of Mount Fuji. It may be, of course, that new paintings will be discovered so that the number increases, but it seems difficult to believe that this number thirty-six is a complete accident and not in some way a challenge to the great Eastern master. Before coming to a conclusion on this matter, we should examine Cezanne's creative process in greater detail.

In the years leading up to 1878, the Romantic or Expressionist tendency of Cezanne's early period gradually became less prominent under the influence of Ukiyo-e. From 1878, he not only adopted some of Ukiyo-e's compositional devices but also started to work in a manner that reflects his awareness of Japanese ink painting. Despite his dislike of Ukiyo-e's tendency towards "cloisonnisme", he at least used lines to delineate the outlines of objects.

In his Ryakuga haya-oshie [A Quick Guide to Drawing],44 Hokusai shows how whole forms are basically composed of hoen [squares and circles] [Figs. 13 and 15] and recommends that artists should compose with the aid of compasses and rulers in order to preserve correct proportions. As if to under- line his point, in Torigoe no Fuji [Fuji seen from Torigoe], an illustration from Fugaku hyakkei [One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji], Hokusai depicted Mount Fuji viewed through an armillary sphere, the ho [square] of the roof in the foreground and the en [circle] of the armillary sphere emphasising Mount Fuji's conical shape.

Cezanne's solid composition and simplification of objects is reminisicent of this guide, as is his famous advice to the young Bernard in 1904, already cited: "Treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone". In his book, Hokusai represents animals in the third dimension by means of circu- lar lines and houses by means of triangles [Figs. 13, 14 and 16]. There was no word in traditional Japanese for "three dimensions" but it is interesting that Hokusai used the phrase "as one sees things by flying freely all around them" to express the same idea.45 Hokusai's books were already known in Paris and it may be speculated that Cezanne took the idea of "cubism" from the Japanese master.46 Until now Cezanne scholars have devoted much time to explaining his theory of perspective but they have paid less attention to the origins of cubism.

In his little book, Hokusai set out not just to present series of naturalistic sketches but also to show the principles behind

them, in other words his aim was to create a popular but artis- tically valid treatise on geometrical analysis and stereometric design, the proposition being that most pictures can be bro- ken up into circles and squares. Hokusai claimed that in theo- ry at least he took his theme from an elliptical phrase in the Chinese Confucian classic Mengzi [Mencius]: "Without com- pass or ruler, even the sage cannot draw a perfect circle or square", but to this he added something of his knowledge of Western art, East and West fusing in his remarkable mind to create a brilliant adaption that belongs to neither world, but to his own special universe.47 Cezanne expounded something similar two generations later, and it seems likely that Hokusai himself derived the basic idea, directly or indirectly, from for- eign sources such as Dutch painting manuals of the mid-sev- enteenth century, perhaps through publications such as Morishima Chury6's Komo zatsuwa [Red-Fur Miscellany, or description of Europe] of 1787. Once the concept entered Hokusai's head, however, it underwent all kinds of transfor- mations, so that the result is a work of real creativity, far ahead of its time both in theory and in practice.48

The ruthless simplification of form and the bright colours Cezanne used at this period could also have been influenced by Japanese art, the Mont Sainte-Victoire series in particular exhibiting a number of parallels with views of Mount Fuji by Hokusai and Hiroshige. There are compositional similarities between Marronier du Jas de Bouffan en hiver (Rewald 531, 1883-86) [Fig. 17], and Hodogaya from Hokusai's Fugaku sanjurokkei [Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji] [Fig. 18]. Rewald photographed the same scene to demonstrate that in the painting the trees are artificially elongated and the horizon is raised. Mont Sainte-Victoire is not visible in Rewald's photo- graph but even if it could be seen it is doubtful that it would have appeared so high, and virtually certain that it would not have seemed so pointed.49 Even the hill which appears at the right of the composition may have been taken from Hokusai.

This combination of a tree or trees in the foreground and the mountain in the background is also seen in Mont Sainte- Victoire vue de Bellevue (Rewald 511) [Fig. 19], calling to mind Hokusai's Shinshu Suwako [Lake Suwa in Shinano Province] [Fig. 20], which shows trees in the centre dwarfing a tiny Mount Fuji in the background. The idea of the tree in the cen- tre foreground and the mountain in the distance clearly made an extraordinary impression on Cezanne, but he always avoid- ed the temptation to indulge in the exaggeration seen in some of Hokusai's prints. The painting of Mont Sainte-Victoire in the Musee d'Orsay, Paris (Rewald 608, c. 1890) [Fig. 21] resem- bles a reversed image of Hokusai's Sunshu Katakura [Kata- kura in Suruga Province] [Fig. 22] while in Sainte-Victoire au grand pin (Rewald 598, 1886-7) [Fig. 23] the painter puts the

215

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

21) Paul C6zanne, (<Mont Sainte-Victoire,, c. 1890, Mus6e d'Orsay, Paris.

tree aside, but retains the branches which cover the sight of Sainte-Victoire like the pine trees in Hokusai's KoshO Mishimagoe [Mishima Pass in Kai Province] [Fig. 24]; all three prints came from the series Fugaku sanjurokkei [Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji].

It was not just the composition of the Mont Sainte-Victoire paintings but also the very idea of a series of views of a spe- cific mountain which seem to have been derived from Hokusai's views of Fuji. Before Cezanne, no European painter had executed a long series of views of a single mountain, even during the romantic period when mountainous landscapes were celebrated in art, literature and music.50 On the whole,

mountains continued to be represented as symbolic, like Mont Sinai or Mount Parnassus, rather than as individual, identifi- able objects.51 In Japan, by contrast, Mount Fuji was an object of worship as early as the eleventh century and from the Muromachi period (15th century) pictures of the mountain were used as ex-votos at Shinto shrines. During the Edo Period the cult of Mount Fuji grew more widespread and it came to be seen as a symbol of the beauty of the natural world. For Hokusai, its form and colours changed from every viewpoint and at every time of the day and season of the year, so that his depictions of the sacred mountain are now univer- sally regarded as symbolic of the beauty of nature.52

216

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

22) Katsushika Hokusai, ((Katakura in Suruga Province)) (from the series ((Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji>), colour print, c. 1829-33.

Of course there are major differences between the approaches adopted by the two artists. Cezanne did not include human figures in his paintings of Mont Sainte- Victoire, nor did he drastically reduce the middle ground in the same way as Hokusai, who always gave greatest empha- sis to the foreground and background. He obviously had some special reason for selecting that particular mountain, since he certainly had the opportunity to observe other fine peaks. In the summer of 1896, for example, he could have seen mountains more than 2000 metres high when he visited Annecy, but these left him unmoved. Staying at a health resort at Talloires on Lake Annecy, he wrote to his old friend Philippe Solari:

"Quand j'etais a Aix, il semblait que je serais mieux autre part. Maintenant que je suis ici, je regrette Aix. La vie com- mence a etre pour moi d'une monotonie sepulcrale... Mon fils sera sans doute bient6t a Aix, fais-lui part de mes souve- nirs, des rappels de nos promenades aux Peirieres, a Ste Victoire... Pour me desennuyer je fais de la peinture, ce n'est pas tres drole, mais le lac est tres bien avec de grandes col- lines tout autour, on me dit de deux mille metres, ga ne vaut pas notre pays, quoique sans charge ce suit bien. - Mais quand on est ne la-bas, c'est foutu, rien ne vous dit plus."53

Cezanne claims here that his preference for Mont Sainte- Victoire was prompted by love of his home, but in reality it was

217

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

23) Paul Cezanne, (<Sainte-Victoire au grand pin,,, 1886-7, Courtauld Institute Galleries, London.

the fact that he had been so familiar with the forms of the mountain since early childhood that he felt confident enough to embark on a series of thirty-six views.

Karl Berger makes the assumption that Cezanne began his series of view of Mont Sainte-Victoire around 1890 and suggests that Monet, who wanted to start work on his water- lily series, made Cezanne aware of Hokusai's Fuji prints.54 In fact, however, he had already painted two views of the mountain in 1878-9 (Rewald 397, 398) and two further paint- ings in 1882 (Rewald 511, 512). It is possible that Cezanne had learned about the importance of the number thirty-six from Edmond de Goncourt's book on Hokusai, published in 1896:

"De 1823 a 1829 parait, sous le title de Les Trente-Six Vues de Fougakou (Fouzi-yama), une serie d'impressions celebres, qui dans le principe ne devait compter que 36 planches, et dont le nombre a ete porte a 46 planches. Cette serie en largeur, aux couleurs un peu crues, mais ambitieuses de se rapprocher des colorations de la natu- re sous tous les aspects de la lumiere, est I'album inspi-

24) Katsushika Hokusai, <<Mishima Pass in Kai Province,, (from the series <<Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji>,), colour print, c. 1829-33.

rateur du paysage des impressionistes de I'heure presen- te."55

The fact that Cezanne apparently painted thirty-six views suggests a secret rivalry with Hokusai. Needless to say, when he first started painting the mountain in 1870 (Rewald 156, Munich, Staatsgalerie) he was not subject to the influence of Hokusai, but when he painted the subject after 1896, he must have been aware of the Japanese artist's work, and from 1904 to 1906 he seems to have been in a hurry to complete the last eight works, devoting much of his remaining energy to painting Mont Sainte- Victoire, perhaps in a final effort to catch up with Hokusai.

Pierre Francastel, criticising the studies of Rewald, who ignored the possibility of Japanese influences on Cezanne, was apparently in no doubt that Cezanne's Mont Sainte-Victoire series was inspired by Hokusai's Fugaku sanjurokkei [Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji]. Francastel adopted the position that "what the Impressionists took from Japonisme was a confirmation of what they had already observed directly"56, but I am convinced that it was not until the discovery of Japanese art that the Impressionists were in a position to make such observations.

218

I ;1

t, . ,?:~ ...

CEZANNE AND JAPONISME

1 Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, and National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, Le Japonisme, Paris, 1988. For other exhibitions on Japonisme since 1972, see Siegfried Wichmann and Monika Goedl-Roth, Weltkulturen und moderne Kunst: Die Begegnung der europaischen Kunst und Musik im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert mit Asien, Afrika, Ozeanien, Afro- und Indo-Amerika, Munich, 1972; Cleveland Museum of Art, Japonisme: Japanese Influence on French Art, 1854-1910, Cleveland, 1975; Northern Centre for Contemporary Art, Sunderland, Japonisme: Japanese Reflections in Western Art, Sunderland, England, 1986. None of the exhibitions included paint- ings by Cezanne.

2 Hidemichi Tanaka , "Japonisme, Manet and Cezanne" [in Japanese], Taiyo, 1977; Hikari wa t5oh yori [foreign-language title: Ex Oriente Lux], Tokyo, 1986.

3 Fritz Burger, Cezanne und Hodler: Einfuhrung in die Probleme der Malerei der Gegenwart, Munich, 1913, pp. 95-6.

4 Kazuo Fukumoto, Hokusai to Inshdha, Rittaiha no hitobito [Hokusai and the Impressionists and Cubists], Tokyo, 1955; ibid., Hokusai to kindai kaiga [Hokusai and Modern Painting], Tokyo, 1968.

5 Pierre Francastel, Peinture et societe, Lyon-Audin, 1951, p. 128. 6 Yamada Chisabur6, Ukiyo-e to Insh6ha [Ukiyo-e and

Impressionism], Tokyo, 1973. Dr. Yamada, a specialist in the history of East Asian influences in early modern European art, was Director of the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo. For the present writer's articles on the connections between Van Gogh and Monet and Japonisme see: The Bulletin of the National Museum of Western Art [Tokyo], 1971 and 1972, in Japanese with French summary.

7 Kimiko Niizeki, Sezannu to Zora: sono geijutsu to yOjd [Cezanne and Zola: Art and Friendship], Tokyo, 2000, p. 317; Klaus Berger, Japonismus in der westlichen Malerei 1860-1920, Munich, 1980. For an English translation of the latter work see note 54.

8 Shigemi Inaga, "La reinterpretation de la perspective lineaire au Japon 1740-1830 et son retour en France 1860-1910", Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 49 (1983), pp. 29-46. Other recent research on this topic will be found in Kaiga no t6oh [The East in Art], Nagoya, 1999.

9 Akiko Mabuchi, Japonizumu: genso no Nihon (French title: Japonisme: Representations et imaginaires des Europeens); Tokyo, 1997.

10 Yokohama Museum of Art, Sezannu-ten [Cezanne exhibition] (exhibition catalogue), Tokyo, 1999.

11 Niizeki, op. cit., p. 317. 12 Ernest Chesneau, "Le Japon a Paris, Exposition Universelle",

Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Sept.-Nov. 1878, p. 387. 13 "It would be much more interesting to compare (Manet's) sim-

plified style of painting with Japanese prints which resemble his work in their strange elegance and magnificent splashes of colour". Emile Zola, "Edouard Manet, etude biographique et critique: Lhomme et I'artiste", in Ecrits sur l'Art, Paris, 1991, p. 152. Zola mentioned Japanese art in his novels. See Le Japonisme, op. cit., "Anthologie", XI, XIX.

14 "Tres critique sur ses contemporains, sauf pour Monet, "le plus fort de nous tous", disait-il, "Monet! Je I'ajoute au Louvre! "" (con- versation with Gustave Geffroy, see P M. Doran ed., Conversation, p. 4); but compare also this quotation: "Pissarro est une vieille bete, Monet un finot, ils n'ont rien dans le ventre... il n'y a que moi qui aie du temperament, il n'y a que moi qui sache faire un rouge..." (Pissarro, quoting Cezanne's words as reported to him by Francisco Oiler, in a letter of 20 January 1906 to his son Lucien; see John Rewald ed., Camille Pissarro: Lettres a son fils Lucien, Paris, 1950, p. 397).

15 Letter to his son Paul, Aix, 3 August 1906, in John Rewald ed., Correspondance de Paul Cezanne, Paris, 1978, p. 318.

16 "...they surround human figures and objects with rough, approximate outlines and fill them from one corner to another with flat colour. Their pictures have the tawdriness of posters and the pattern- like quality of stencils". See M. Derain ed., Conversation avec Cezanne, Paris, 1977, p. 133.

17 John Rewald, Cezanne: Sa vie, son oeuvre, son amitie pour Zola, Paris, 1939.

18 Letter to Emile Bernard, 23 October 1905, Correspondance, op. cit., p. 315.

19 Edition of 1926. Gasquet proves that Cezanne at least read Goncourt's books on Japanese artists. It is reported that before he made this comment, 'Japanese and Chinese artists became the topic of conversation. When I turned the conversation in that direction, he [Cezanne] said, 'I do not know anything about those people. I have never seen any of their pictures"'.

20 "Treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything brought into proper perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point". Letter to Emile Bernard, 15 April 1904.

21 Conversation with Gustave Geffroy, Conversation, op. cit., p. 4. 22 Correspondance, op. cit., 27 July 1878, p. 169. 23 Chesneau, op. cit. 24 2 May 1878, in Edmond et Jules de Goncourt, Journal:

memoirs de la vie litteraire (edited and annotated by Robert Ricatte with a preface by Robert Kopp, 1989), vol. 3.

25 Chesneau, op. cit., 1 November 1878, p. 846. 26 Goncourt, op. cit., 6 November 1878, pp. 309-10. 27 See note 18. I. Rewald, Paul Cezanne. The Watercolors, A

Catalogue Raisonne, Boston, 1983, no. 134. 28 During this period he wrote many letters to him requesting

financial assistance. 29 Later he studied European-style painting in Paris under Jean-

Leon Ger6me, Professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. His best-known work is a Nude in the Tokyo National Museum.

30 Goncourt, op. cit., 14 December 1894, vol. III. 31 Hotel Drouot, Catalogue of the Inheritance of Emile Zola

(Auction catalogue, Paris, 9-13 March 1903). 32 Others present at this meeting included Felix Regamey, a

painter who visited Japan with Emile Guimet in 1876. 33 The reverse of this Etude, listed as C. 608, shows a portrait of

a young man and a landscape view of the Jas de Bouffan, both exe- cuted at about the same time.

34 Lionello Venturi, Paul Cezanne: Watercolours, Oxford, 1943. 35 T. Kurita, in Cezanne and Japan, op. cit., p. 161, pp. 201-2. This

identification was proposed by Mikayama Takaaki, curator at the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art.

36 Zola also owned Japanese porcelain, lacquer, ivories, armour and other items.

37 Niizeki, op. cit., p. 313. 38 Conversation with Joachim Gasquet, Conversation, op. cit., p.

117. 39 Letter to his son, 13 September 1906, Correspondance, op.

cit., p. 325. 40 Le Japon artistique (Samuel Bing ed.), December 1892, p. 434,

1. 1-5. 41 Conversation with Emile Bernard, Conversation, op. cit., p. 65. 42 Conversation with Emile Bernard, ibid., p. 73. 43 John Rewald's recent catalogue lists the views of Mont Sainte-

Victoire as follows: 156, 397, 398, 511, 512, 551, 572, 573, 574, 598, 599, 608, 651, 698, 762, 767, 768, 796, 837, 899, 900, 901, 902, 910, 911 912, 913, 914, 915, 916, 917, 918, 931, 932,.938, 939. See John

219

HIDEMICHI TANAKA

Rewald (in collaboration with Walter Feilchenfeldt and Jayne Warman), The Paintings of Paul Cezanne: A Catalogue Raisonne, New York, 1996.

44 Katsushika Hokusai, Ryakuga haya-oshie [A Quick Guide to Drawing], Edo [Tokyo], 1811.

45 In the introduction to a sequel to Ryakuga haya-oshie (1813), also by Hokusai.

46 Japanese "albums, livres a gravures" were widely diffused in the Parisian art world: see Chesneau, op. cit. p. 387.

47 Richard Lane, Hokusai: Life and Work, New York, 1989, p. 116. 48 Ibid., p. 116. 49 Pavel Machotka, Cezanne: Landscape into Art, Grosse Pointe

Shores, 1996, p. 126. 50 See the catalogue Le sentiment de la montagne, Musee de

Grenoble, 1998.

51 The Greek Mount Parnassus is not normally made the exclu- sive subject of a painting; it is more a patriotic national symbol than a regional landmark. See Albert Boime, "Cezanne's real and imaginary estate", Zeitschrift fur Kunst, 4 (1998), p. 38.

52 See Kan6 Hiroyuki, Katsushika Hokusai, GaifQ-Kaisei [Katsushika Hokusai: South Wind at Clear Dawn], Tokyo, 1994; Nagoya City Museum, The Spirit of the Japanese: The Beauty of Mount Fuji (exhibition catalogue, Nagoya, 1998) and Suzuki Susumu ed., Nihon no bi: Fuji [Japanese Beauty: Fuji], Tokyo, 2000.

53 Correspondance, op. cit., 23 July 1896, p. 253. 54 Klaus Berger, Japonisme in Western painting from Whistler to

Matisse (translated by David Britt, Cambridge, 1992), pp. 11-13. 55 Edmond de Goncourt, Hokousai, Paris, 1896; (new edition in

the series Fins de siecle, H. Juin ed., Paris, 1986), pp. 230-1. 56 Francastel, op. cit., p. 128.

220