Caso Helsinski

-

Upload

jorge-vergara-castro -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Caso Helsinski

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

1/12

Environmental Policy and GovernanceEnv. Pol. Gov. 20, 135145 (2010)Published online in Wiley InterScience(www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/eet.532

* Correspondence to: Arho Toikka, University of Helsinki, Department of Social Policy, PO Box 18, Snellmaninkatu 109 Helsingin Yliopisto,Finland 00014. E-mail: [email protected]

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment

Exploring the Composition of CommunicationNetworks of Governance a Case Study on LocalEnvironmental Policy in Helsinki, Finland

Arho Toikka*University of Helsinki, Department of Social Policy, Finland

ABSTRACTGovernance (Rhodes, 1996; Kooiman, 1993, 2003; Pierre, 2000) is one of the most popular

new concepts in policy science and administrative science. The literature does not consti-tute a unified theory, but a single theme runs throughout: policy decisions are referred to asbeing made by networks of organizations. However, the network governance literature hasnot built on the previous literature on policy networks and the methods of social networkanalysis. The structure of the governance network can make a difference in policy-making,but the structures have often been neglected in governance research. Here, the combina-tion of social network analysis and governance literature is suggested as a possibility forinvestigating network structures. In particular, we investigate how and why the organiza-tions involved choose their communication partners. The methods of exponential randomgraph modelling (sometimes referred to as p* models) (Snijders et al., 2006; Robins et al.,

2007a, 2007b) enable the simultaneous modelling of structural effects and individual vari-ables and their effects on network structure. As of yet, there are few substantial applications.The aim of this paper is to evaluate the composition of a policy network and the effects ofnetwork and actor variables on the empirically observed network. The environmental policyof the city of Helsinki, Finland, is used to demonstrate the approach. Copyright 2010John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment.

Received 2 April 2009; revised 22 December 2009; accepted 19 January 2010

Keywords: governance; policy network; exponential random graph model

Introduction

ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY-MAKING HAPPENS IN COMPLEX SOCIALECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS, WHERE A GOVERNANCEsystem dictates resource use (Ostrom, 2009). The SES framework, as well as policy science in general, hasemphasized the complexity of governing when no actor holds all the necessary information or the neces-sary resources for efficient policy. In policy science, this has been conceptualized in the theory of govern-

ance (Kooiman, 2003; Pierre, 2000; Pierre and Peters, 2005; Rhodes, 1998). The government has given way to

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

2/12

136 A. Toikka

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

networks of public and private organizations, which are responsible for policy formulation and policy choice, aswell as implementation.

However, the concept of a network is often underdeveloped in governance research (Christopoulos, 2008). Inthe informal sense, networks are assumed to be simple membership structures, but real life governance systemsare complex communication structures, where the interplay of institutions produces policy. Policy depends on col-

lecting information dispersed in various organizations. As organizations seek to mobilize the information requiredfor policy-making, they form communication links. As individual organizations establish communication links, acomplex structure of interwoven links is born.

The purpose of this paper is to develop methods for evaluating the structure of this complex network. As thegovernance organizations draft policy, collect information and settle policy disputes through the network, the com-munication structure who talks with whom is important. The aim here is to model the network compositionwith structural effects and actor attributes. Do the organizations in the network choose their communication part-ners based on their previous partners, or solely on the basis of the information they hold and the status they have?

The aim is to build on the earlier literature on policy networks (see Brzel, 1997, for a review) and the methodsof social network analysis (Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Carrington et al., 2005). The policy network approachmapped the structures of political communication between organizations (Laumann and Knoke, 1987), but wascriticized for lack of theoretical focus and explanatory potential (Dowding, 1995). Connections between the method

of policy networks, governance and socialecological systems are strong, but they have not been united in full.The governance literature should benefit from applying the insights learned from policy networks, and provide theconnection between theory and method. A governance network, then, refers to a specific type of policy network,which is a subcategory of social networks.

The governance network is a collection of the collaborating actors making policy decisions. The governanceliterature has various definitions and debates over the meaning of network. Different conceptualizations of thesenetworks have ranged from corporatism to post-modern network societies (van Kersbergen and van Waarden,2006, p. 148). Whether the network is autonomous from the state (Rhodes, 1996) or the state plays an importantrole in the workings of the network (Pierre and Peters, 2005) is one of the debated features of the network. Govern-ance has even been assumed to result in different policy instruments than government (Jordan et al., 2005, p. 481).Democratic accountability and openness are pointed out as important features of the process (Hirst, 2000, p. 28).

Here, the simplest possible definition based on the policy network concept is used. The network of organizations

is charged with negotiating policy. The governance network is the set of actors, each of who may communicatewith any number of others. The network is a communication structure: policy decisions are affected by the com-munication structures that result from individual communication links between organizations. The analysis of theindividual links and the resulting structure is reported here.

The paper uses the methods of exponential random graph modeling, a method of statistical social network analy-sis, to explore the composition of governance networks. Why do organizations choose the communication partnersthey do choose? The actors can base their choice of contacts on multiple criteria, based on both the network itselfand various background variables. It is assumed that there is some freedom to choose communication partners,even if one actor may be able to issue punishments for non-compliance. The goal is to explore the effects of dif-ferent background variables and the network itself on the composition of the whole network.

The exponential random graph model (Robins et al., 2007a; Snijders et al., 2006) is a statistical model where thedependent variable is the presence or absence of ties between all pairs of actors in the network, and the explanatoryvariables are different network effects and attribute variables. As the ties in the communication networks cannotbe considered independent from each other, standard regression assumptions do not hold and a special modelmaking dependence assumptions instead is needed.

The modelling enterprise is demonstrated using a data set based on the environmental governance networkin the City of Helsinki, Finland. The main body of the data is the network of communication in the drafting andplanning of environmental policy programs. As is usual with environmental policy, especially when it is conceptual-ized as policy for sustainable development, the policies made concern a wide variety of issue areas. Environmentalpolicy includes energy policy and handling pollution, but construction guidelines and education programmes too.To be able to make sensible policy for such diverse areas, the number and range of organizations needed to planpolicy is significant. The network consists of 78 political, administrative and non-profit organizations, and private

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

3/12

Exploring the Composition of Communication Networks of Governance 137

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

companies. The data was established by semi-structured interviews with organizational representatives, and com-plemented by archival records. The data is based on policy processes in a metropolitan city, but it is assumed thatthe conclusions would hold for national policy as well.

The next section describes the theoretical background in more detail and justifies the link between the theoryand the method. It is followed by a background section on the case study and data, describing the processes of

environmental decision-making in Helsinki. Then, the exponential random graph model is presented, followedby the actual results and discussion.

Networks of Decision-Making

This section discusses the modeling of governance networks and the theoretical predecessors of the present work.The current discussion on governance connects to discussions on socialecological systems and on policy net-works. The focus is on networks. A dissection of definitions of networks in governance justifies the use of explicitnetwork methodology.

The concept of governance networks has multiple meanings, as the governance literature is a multidisciplinary,non-uniform tradition. From international relations to corporate governance, these traditions share the focus on a

decision-making process where multiple actors contribute (van Kersbergen and van Waarden, 2004, pp. 151152).In public administration, the recent practices of private provision of public services, such as contracting out orpublicprivate partnership, are often used to exemplify governance. Environmental policy researchers have adopteda network approach, too (for example Cashore et al., 2007; Jordan et al., 2005). The literature has diverged intotwo strands: environmental governance and natural resource management. Environmental governance researchhas focused on the new aspects of governance: the admittance of private actors into the decision-making processthrough the mechanisms of publicprivate partnerships or voluntary agreements. The natural resource approachhas applied social network analysis for stakeholder analyses (Prell et al., 2009, p. 502).

Environmental policy and resource management have also used the conceptualization of socialecologicalsystems, where a governance system is embedded into a complex system of interacting physical properties andrules (Ostrom, 2009; Folke et al., 2005). The SES approach points to a governance network as a subsystem. Socialnetwork analysis has been used in this context, but usually for personal networks. For example, personal social

network structures have been found to contribute to local-environmental knowledge and in turn, to resource use(Crona and Bdin, 2006).

The governance networks here are social networks of organizations, with the objective of policy making. As theconcept of network has so many different applications, we need to clarify the definition of governance networkused. Here, governance network is the group of actors involved in planning public policy. The elected governmentdoes not have the resources to make complex policy decisions without utilizing the expertise of administration andpublic partners. To utilize the resources, the government has to admit private interests into the policy process.However, it is not a simple trade-off between political power and technical expertise. It is also about developingshared visions of the system and of the policy process, about games aboutrules (Stoker, 1998, 22).

The decision-making networks are autonomous, self-organizing structures (Rhodes, 1996, p. 658), or the emer-gent structures of interactions between the members of the network (Kooiman, 1993, p. 4). The network structuresare the results of interdependencies between the organizations, due to the increased complexity of the informationrequired for efficient policy-making. The governance network should be interpreted as the complete pattern ofinteractions, with vastly differing positions for actors. The theoretical foundations from the policy network traditionare linked to this pattern (Marsh, 1998; Klijn and Koppenjan, 2000, pp. 138142). The policy network traditionoffers tools to systematically differentiate between network positions. However, the policy network tradition wascriticized for sticking to simple descriptions of the networks (Dowding, 1995), with weak links between methodand substantial theory (Peters, 1998).

The early attempts at policy network analysis in the 1980s tried to build on the observations of the changingpolity, and the criticism of these humble attempts is fair (Richardson, 2000, pp. 10061008). However, policynetworks moved on, and fully fledged modelling approaches have been become available (Thatcher, 1998). Themethods have been refined within the research tradition as well as combining the framework with other approaches

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

4/12

138 A. Toikka

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

(Thatcher, 1998, pp. 404406), using social network analysis as a method to fill the gaps in theory elsewhere.The governance network approach here is an example of the latter. Previous ways of statistical modeling of policynetworks have modelled personal networks in various settings (Christopoulos, 2006; Diani and McAdam, 2003)and the effects of organizational networks in negotiation from initial preferences to final decisions (Stokman andZeggelink, 1996).

Here, the approach is slightly different. The aim is to model communication partner choice. The developmentof new methods (Snijders et al., 2006) and more efficient computer programmes (Snijders et al., 2007) hasenabled the comparison of different motivations or factors in communication or collaboration partner choice inthe network.

Exponential random graph models are a family of statistical models where the dependent variable is the presenceor absence of a tie between a pair of actors, and independent variables are different dependencies between the ties,called network effects, and actor attribute variables (Robins et al., 2007a, p. 173). The network variables describeinterdependencies in the ties between organizations. They are different structures of the network: in effect, we aretrying to build a model for estimating the presence or absence of a single tie, taking all the other ties and the struc-tural tendencies they display as data. Starting with simple dyadic (pair-wise, or how much does an ego tie toward analter depend on the alter tie toward the ego) dependence assumptions (Holland and Leinhardt, 1981), moving intotriadic and more complex structural effects (for example, structural balance, or friend-of-a-friend-is-a-friend, explana-

tions (Pattison and Wasserman, 1999; Wasserman and Pattison, 1996), recent advances have enabled the use ofany number of interdependencies at all levels of network structure to be modelled (Snijders et al., 2006). The actorattributes correspond to regular survey data, in that they describe qualities of the actors, independently of each other.

Then, what structural and actor-level effects should we look for when looking at the governance network? Forboth, there can be local and global effects. Networks have been described through various observation points forthe actors. The actors can observe the network at different levels: actor, dyadic, triadic and global (Contractoret al., 2006, p. 687). The actors obviously prefer to have communication ties, but as argued they do not uniformlyprefer having more ties after a certain number. The ties can be said to have diminishing utility. For triadic effects,the same type of effect would be expected to be observed. Groups of three are the smallest units that form networksubgroups. Being part of these subgroups is probably beneficial to the actors involved, but as the group grows thepossibilities to take advantage of the network become more costly in time and resources.

When calculating the advantages and costs in creating ties, the actors observe not only their own position, but

also that of the prospective partner. Thus, when looking to build new connections, the actors will take into accountnot only the number of their own connections, but also that of others. As the actors have to share the time andcompromise capabilities with all others linked to a particular other, they could prefer other things equal, othersless constrained and strained by prior communication partners.

In terms of the governance literature, the forces driving the dyadic partner choice can be viewed as two alterna-tive hypotheses. First, the story of the hollowing out of the state (Rhodes, 1996, p. 661; Laumann and Knoke, 1987)depicts a network of interlinked sectors with a more-or-less hollow core. From the point of view of a single organiza-tion, communication partners with fewer connections might be favoured, because they are easier to influence, asthey are more dependent on you for their communications within the network. Second, an alternative reading ofthe proponents for the enduring importance of the state in the political process (Pierre and Peters, 2005) would bethat even in the network, the centrality of the state is sustained. As a pair-wise prestige hypothesis, the first accountsuggests that popular central actors would be shunned when new network partners are sought out. Respectively, ifthe state actors are able to retain their position, the network would steer toward a structure of hubs and peripheries,when well connected actors are preferred over others. In policy negotiations, the possible advantages of well connectedpartners arise from the ability to broadcast your message to a wide audience. Even if your influence only goes so farwith the big players, a small influence on multiple opinion leaders adds up and can go a long way.

Thus, the attractiveness of powerful communication partners might work in two different directions. Whetherorganizations seek to connect with less-connected organizations in the hope of having considerable influence overthem or with more-connected organizations in the hope of focusing their influence in the heart of the network isan empirical question.

At the level of a triad, a group of three organizations, the simplest effect is the friend-of-a-friend-is-a-friendexplanation. The importance of the third in the network context is obvious: with just two actors, the whole network

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

5/12

Exploring the Composition of Communication Networks of Governance 139

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

idea is empty. The theoretical drive behind this paper is establishing a link between governance theory and com-munication network patterns. Thus, how and why organizations form tightly knit subgroups in the network isinteresting. If the objective for communication is simply the spread of information, building links to actors whoare already linked to your communication partners is inefficient. Policy influence can be assumed to be different:duplicated communication of similar preferences can be assumed to be more influential (Borgetti, 2005, p. 59).

These network effects are supported by the actor level effects. Any number of actor attributes making them morestimulating communication partners could be hypothesized, but undoubtedly the most important when looking atgovernance networks is the attractiveness of the central government and the political and administrative organiza-tions representing it. If the state is able to control network formation, it should have advantageous network posi-tions. As we are controlling for other effects at the same time, this should be visible in basic popularity. The stateactors should be expected to have more connections than otherwise similar actors with otherwise similar situations.If the state still holds unique, indispensable resources for policy-making, the effect could even dominate all othereffects. Most likely, there is a positive effect for state actors popularity, and the strength of the effect can serve asa guideline to evaluate how the necessary resources for policy-making are dispersed in the society.

Another effect based on the different types of actor involved is to control for actors building links to similaractors. As there are multiple organizations representing the state in the process, this is also important as a controlfor the popularity effects, so the links between the administrative actors do not appear solely as state control over

the network. However, the effect is not only interesting as a control variable, for all types of actor, whether theyestablish more or fewer links to similar organizations. Any number of similarity variables could be used, buthere we settle for the simple: the typology of organizations, distinguishing between political and administrativeorganizations within the public group, and between various types of non-profit, company and research organiza-tions with the group of private organizations. How strongly each of these groups gets involved with actors withintheir own reference group could be an interesting factor in establishing the variable costs of communication. It isprobably less costly to communicate with similar organizations, due to shared organization cultures and possiblelinks outside the realm of policy-making.

As the driving force behind governance networks is the mobilization of resources, we should try to include vari-ables for different resources. Being part of the state organizations can already be viewed as a resource of sorts, butthe most discussed resource in the literature is expert knowledge. The increased complexity of policy problemsrequires a diverse knowledge, not only on a technical level, but also tacit, local knowledge about the different policy

solutions and their interactions. How to combine and liken these different expertises is a hard methodologicalproblem. Again, I use a simple variable for determination of expertise: over a defined set of policy problems, acertain set of organizations is reputed to hold the necessary expertise for problem solving.

Expertise is obviously not the single important resource in governance. Here, it is the only one included in themodel, but other resources whose importance could be stipulated include material resources for policy research.In the related policy network research, resource variables such as money and staff have been used (Laumann andKnoke, 1987). However, the measurement of these variables is complicated: the size of the organization is nota good of indicator of the amount of resources available for policy negotiations and networking. Thus, these areexcluded here, but, where data is available, they could be included as well.

Background

The analysis focuses on the policy process and communication networks in environmental policy-making in Hel-sinki, Finland. I concentrate on the process of drafting and preparing for the Helsinki Ecological SustainabilityProgramme (HESP), the main environmental policy document for the city. The HESP was an explicit productof a networked communication process, as the policy measures as well as the goals were determined in the col-laboration of city agencies and private organizations. The process was originally initiated by the City Board, theexecutive body for local policy, but their call for action was general enough to include almost any policy measures.

The collaborative drafting process of the programme started in 2003, and was completed in 2005. The draftversion put together with the help of numerous organizations passed the city legislative unanimously, andthe programme was in force from 2005 till 2008. The widespread approval of the programme is interesting: no

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

6/12

140 A. Toikka

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

political debate happened and the prepared document was accepted as is, which speaks for the governance insteadof government hypothesis, as argued by some of the most extreme governance writers (e.g. Rhodes, 1996). Theobject of analysis here is limited to the drafting phase of the process, but this at least serves to underline theimportance of the phase for policy results.

The network data analysed is based on 78 semi-structured interviews with organizational representatives. The

organizations to be included were chosen on the basis of official listings of communications for recent HelsinkiEnvironmental Policy Programmes. A single representative was chosen to be interviewed for each organization,based on job titles and meeting minutes from the process. These representatives were then questioned aboutdifferent communication links with all the other organizations in the data, and they were given the option ofbringing up new organizations as well. No organizations outside the original list were mentioned in more thana few interviews. This probably indicates that the original list was comprehensive of those actually involved: itshould be noted that any organizations wishing to influence the process but who have no connections at allare excluded from the data. This poses no problem for the present analysis, estimating the effects of the actualnetwork, but rules out the possibilities of using the data for the analysis of democratic representativeness of thenetwork, for example.

The organizations included are political and administrative actors in the city organization itself and non-gov-ernmental, non-profit organizations, as well as private corporations. The various agencies and organizations of

the city bureaucracy were treated as separate organizations, even if they are all officially supervised by the politicalactors. State agencies are semi-autonomous, as tasks are delegated downwards (van Kersbergen and van Waarden,2004, p. 154). The extent of autonomy varies between city-owned enterprises and traditional agencies, but all ofthem have some power over their own goals and the means to achieve them. Different institutionalized culturesand competing goals can put two organizations, formally both part of the city, on the opposite side of an issue.Governance literature has often emphasized the admittance of private organizations into the policy process, butfrom the network perspective the intergovernmental relations are just as important and equally relevant for thejustification of abandoning policy process models focusing on the legislative body.

Here, the drafting network for HESP included city agencies from an energy utility and public transport companyto an education board and research organization. The differing preferences for these organizations are especiallyvisible in environmental policy. Environmental policy has important effects on the behaviour of many of theorganizations, but is only tangentially related to their main goals providing a certain service. A lot of the policy

process concerns fitting these goals together in a coherent policy document.The non-governmental organizations in the data include residents associations, environmentalist groups

and a few trade unions. Trade unions are involved in the process because of their ability to provide specialistinformation. The residents associations are more interesting: they can also provide important information tothe process, but the role of their tacit knowledge and lay-expert knowledge (Yli-Pelkonen and Kohl, 2005, p. 4)is more complicated. Local environmental policy has to account for many unique features of environmental andsocial conditions. The lay-expert knowledge locals have is more complex than just observations about their sur-roundings and information about values attached to them, but it can also complement scientific informationabout the relations of objects.

The data lists all communication links for each organization, along with certain statistics about the organizationitself. The network density, or the number of observed ties compared with the number of possible ties, is 0.207. Asargued above, the hypothesis put forward by governance theory is that in a governance network there are structuraleffects that cannot be reduced to actor level attributes. In the exponential random graph model, we would expect tofind structural effects that still hold when actor attributes are controlled for. In other words, communication partnerchoice is not just based on with whom you wish to communicate, but also with whom they already communicate.

Model

To define the endogenous network effects and the exogenous attribute effects in detail, I next explain the relationbetween the theoretical approach laid out in the previous sections and the model we apply in the analysis section.The approach and terminology of Snijders et al. (2006) is followed.

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

7/12

Exploring the Composition of Communication Networks of Governance 141

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

The first network variable is the number of connections a communication partner has, and whether a greaternumber makes it more or less attractive as a new partner. As discussed, in the governance network, popularity orprestige effects might work two ways more partners may make it either more or less attractive. Another thingwe have to account for is the relative importance of another extra tie. The difference between having one or twopartners may be huge, but the difference between 32 and 33 negligible. Making the assumption of decreasing

importance allows us to account for this, as well as solving some issues with model degeneracy (Snijders et al.,2006). The assumption is modelled with an alternating k-stars -parameter. The parameter measures popularity,but with each extra link assumed to be less important than the previous one. 1 A positive alternating k-star effectmeans a preference to connect to others with more previous connections, and a negative one a preference forthose with fewer connections.

The second variable measures whether the communication partners of ones previous partners are more (orless) attractive when building new connections. Social networks have strong tendencies for transitive triadicstructures a friend of a friend is a friend, at least statistically more often than not. This effect also carries overfor larger network structures, or larger cliques with more members. In the governance network, I expect to find apositive effect for subgroup building, even though the effect estimated is two directional, and it is possible to finda negative effect as well. As with popularity, the triangular effects or alternating k-triangles -effects are estimatedsimultaneously for all sizes of subgroups, with a decreasing importance for larger groups. Again, a positive effect

would imply a preference for connecting to the communication partners partners, a negative one a preferencefor avoiding them as partners.

However, we want to make sure the observed transitivity effect is really transitivity and the triads do not resultfrom a tendency to build open-jaw structures that are prerequisites for the triads. For a triad to occur, there needsto exist a path between two actors. If there is a tendency to build these paths between a certain pair of actors, thiscan result in what appears to be transitivity. I include an alternating k-two-paths parameter to account for this, assuggested by Snijders et al. (2006). A positive tendency for these structures would imply a network structure withtwo highly connected central actors with a starlike structure around them, but the most important interpretationsif a significant effect is found are combinations with the transitivity parameter.

Then, we use actor attribute variables to supplement the three network variables. I use three fairly simpleattribute variables: organization type, organization type similarity and an issue area expertise variable. The first twoare answers to the criticisms governance literature has received, as they measure whether governmental organiza-

tions are more attractive communication partners than others. The organization type variable has six categories:the city organization is divided into central administrative (under direct political control, with no autonomousagenda), sectoral administrative (city owned, but with own agenda and at least some decision-making power overmethods to achieve set goals) and subsidiaries (city-owned companies with still higher autonomy). The privateorganizations are grouped into for-profit companies, local associations (mainly residents associations) and othernon-profit groups, including environmentalist organizations as well as some single-issue groups.

The similarity variable uses the same data, but measures whether organizations are more or less likely tobuild connections to organizations of the same type. This is important to control for two possible effects. First,as governmental organizations have more connections in the network than non-governmental ones, we need tocontrol for the similarity effect to make sure the organization type effect actually holds. Second, controlling forthis homophily effect allows us to refine the interpretation of transitivity effects. When the organizations aremaking connections to similar partners, they might make them to partners with a similar background or partnerswith a similar set of connections. Differentiating between these two allows for better estimates of actual networkstructure influence.

The last variable in the model is the issue area expertise. Reliable measures of a complex issue such as expertiseare difficult to attain, so I have used a rather simple and crude measure: self-reported expertise over 15 differentareas important in environmental policy making. These include both scientific knowledge and practical informa-tion, for example expertise in ecological construction, as well as local environmental knowledge. The range ofexpertise areas is from a minimum of 1 (some single issue organizations) to 13 (the city environment centre). Such

1 It would be possible to estimate this parameter or the speed of the decrease (Hunter, 2007), but I use the parameter setting suggested byRobins et al. (2007b, p. 198).

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

8/12

142 A. Toikka

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

a simple measure does not give us a very detailed picture of expertise and policy-making, so the main interestin its inclusion is to see whether the observed network effects still hold when we account for the fact that someorganizations are already more attractive partners before the networking begins.

AnalysisUsing the exponential random graph model with these variables, we obtain parameter estimates for their exponen-tial effect for the probability of a tie, similar to logistic regression coefficients (Snijders et al., 2006, p. 104). Theanalysis was carried out with the software package SIENA, Version 3.1 (Snijders et al., 2007).

The number of ties is fixed to the observed density of the network. Thus, we are trying to simulate the networkbuilding process and establish a combination of parameter estimates that produces a network with the best corre-spondence to the observed network. A stochastic Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm was run and iterated untilmodel convergence was achieved. The model converged well, implying that the inherent randomness in stochas-tic modelling should not be an issue for model stability and the results. The analysis proceeds with a backwardelimination procedure of non-significant effects. The t-ratio, parameter estimate divided by standard error, wasused to determine significance. A t-ratio of 2 was used as the cutting point (as per Snijders et al., 2006, p. 137).

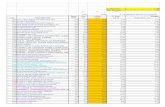

The full model displays a strong preference for transitivity, along with a negative popularity estimate with avery large standard error. The full model parameter estimates are listed in Table 1 as Model 1. The preconditionsparameter is small. The largest of the attribute effects is status similarity. This is likely explained by the pre-established connections between the different city agencies. The status effect is actually slightly negative, whichmeans organizations are more likely to build links to non-governmental organizations than governmental ones,controlling for network position, expertise and status similarity. The expertise effect is positive, but not very strong.

When the variable with the smallest t-ratio, popularity, is removed, the other parameter estimates remain stableexcept for one: when preconditions for transitivity are eliminated, the popularity effect disappears, too.

The final model (Table 1) has one very strong structural effect, with significant but smaller attribute effects.The preference for transitivity or subgroup building is the strongest influence over network partner choice. Theattribute effects are similar to those of the full model, with a medium strength status similarity effect, a small posi-tive expertise effect, and a small negative status effect. Given the task of preparing and drafting an environmental

policy for Helsinki, the various organizations that got involved were first and foremost looking for collaborationpartners that would complete small subnetworks by opening the last missing link between any two actors in thegroup. Connecting to similar organizations was preferred, possibly because it is easier to establish communicationwhen you share a certain institutionalized organization culture. The number of issue areas where an organizationhad expertise did contribute to the link building, but as the data does not estimate the strength of expertise thiseffect might be speculated to be stronger with more refined data. The weak negative status effect means that, afterwe account for subgroup building and the tendency for intergovernmental relations, the administration is actuallyless attractive than private organizations when it comes to negotiating policy.

Model 1 Model 2

est. s.e. est. s.e.

Popularity 0.858 0.737Transitivity 1.453 0.243 1.347 0.218Preconditions for transitivity 0.028 0.018Expertise 0.210 0.023 0.200 0.020Status 0.111 0.027 0.121 0.029Status similarity 0.458 0.101 0.468 0.101

Table 1. MCMC estimates for non-directed communication relation in Helsinki environmental governance network with theirstandard errors

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

9/12

Exploring the Composition of Communication Networks of Governance 143

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

The governance literature has pointed to the increased influence of non-governmental actors in policy-making.The present analysis gives empirical support to the literature. The conclusions of the model here are that tightlyknit subgroups where all the actors are familiar with each other are what the non-governmental actors prefer,when they are let into the process. Private actors have been involved in the modern policy-making processes, andthe question is whether they have any real influence. From this perspective, the policy process appears to be more

driven by mobilization of expertise and finding answers to the complex issues at hand than a traditional powerstruggle between competing factions. In environmental policy in particular, it is hard to form a two-sided cleavagein the opinions. The problem has multiple levels and dimensions. Even the ultimate goal good environment might be agreed upon by all. The differences in definition manifest themselves at the more specific level. Thestruggles over costs and sharing the costs and the collaboration over finding efficient and agreeable policy meas-ures to deal with the problems gives rise to a different policy process. Governance should be treated as a usefulframework for analysing policy processes with multiple actors and multiple dimensions rather than a theory toreplace old policy science models.

The biggest source of disagreement between governance writers and their critiques has been the diminishingrole of the state. This role should an empirical question, and the use of governance terminology should not beread as an argument for a historical change from government-led policy to completely private decision-making.

Conclusion

The aim of the analysis here was to demonstrate how policy network structures come to be, as results of individualcommunication partner choices accumulating. As the literature on governance highlights the importance of net-works, the network position of potential partners was assumed to be one of motivations behind organizationschoices, but the governance literature has been fairly vague in its definition of networks, and has not incorporatedthe insights from earlier work on policy networks and the new methodology developed with the social networkanalysis tradition.

Here I used a network definition explicitly based on social network analysis. A network is a list of relevant actorsand a list of all of their links for a single relation, in our case a general communication relation. Such a simpledefinition of a network avoids many debates over what constitutes a network and what does not, as we do not have

to discuss whether new public management is really pervasive or not, for example.In the single network analysed, the empirical analysis gave support to this governance hypothesis. The network

has an effect beyond the individual characteristics of the network participants. The network effect was stronger thanthe effects of actor attribute variables. The preference for transitive structures, or building completely connectedsubgroups, was very strong. This effect overwhelmed the effects of the publicprivate divide and the amount ofexpertise in the policy area under scrutiny.

Still, the result should not be read to suggest that governance has, indeed, replaced government. However, itshould be taken as providing some justification for governance as a theoretical framework for policy analysis andthe processes of decision-making. The governance approach highlights a different aspect of policy than most others:the development of a detailed policy document from the starting point of a general, even vague, idea or goal. Thisprocess is characterized by a balancing act between political struggles, or settling differences in opinion and pref-erence, and the mobilization of expertise. The organizations, too, are simultaneously trying to find informationand combine knowledge bases into usable data, as well as positing themselves at advantageous network positions.

This networking should be at the core of further governance research. Here, the data is a single observation froma single network. Using exponential random graph modelling, the next step should be to move into longitudinaldata from multiple networks. The most fruitful would be panel data over numerous observations, but such data isnot easily accessible, and has problems with reliability. If resources are available, the best data would be collectedby observations, as longitudinal data also suffers from memory recall issues if collected by interviews. Data frommultiple networks would allow a comparative approach, but also establishing a range of parameter values for thedifferent effects. The comparison could enable at least two different goals: first, the comparison of different gov-ernance cultures, for example in different issue areas, in different legislations, or at varying levels of government;second, the comparison of effect sizes when the amount of autonomy given to the network varies. The task of the

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

10/12

144 A. Toikka

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

network given by the legislator might range from technical solutions for a set goal to almost full-blown autonomy,where goal-setting is part of the task and the network itself arises from need, not from government mandate.

Even abandoning the exponential random graph models, the explicit network should stay at the epicentre ofgovernance research. The theme of networks is evident throughout the governance literature. Without a definitionthat enables empirical research of network structures, network terminology is just hollow buzzwords. This paper

has aimed to demonstrate one possible approach to explicit network research. Hopefully, the research approachand the results presented have convinced readers of the fruitfulness of the endeavour.

References

Borgetti SP. 2005. Centrality and network flow. Social Networks27: 5571. DOI: 10.1016/j.socnet.2004.11.008Brzel T. 1997. Whats so special about policy networks? An exploration of the concept and its usefulness in studying European governance.

European Integration Online Papers 1(16). http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/1997-016a.htm [1 March 2010].Carrington PJ, Scott J, Wasserman S. 2005. Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis. Cambridge University Press Cambridge.Cashore B, Egan E, Auld G, Newsorn D. 2007. Revising theories of nonstate market driven (NSMD) governance: lessons from the Finnish

forest certification experience. Global Environmental Politics7: 144.Christopoulos D. 2006. Relational attributes of political entrepreneurs: a network perspective. Journal of European Public Policy13: 757778.

Christopoulos DC. 2008. The governance of networks: heuristic or formal analysis? A reply to Rachel Parker. Political Studies56: 475481.Contractor NS, Wasserman S, Faust K. 2006. Testing multitheoretical, multilevel hypotheses about organizational networks: an analyticalframework and empirical example. Academy of Management Review31: 681703.

Crona B, Bdin . 2006. What you know is who you know? Communication patterns among resourceusers as a prerequisite for co-manage-ment. Ecology and Society11(2): 7. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss2/art7/ [1 March 2010].

Diani M, McAdam D (eds). 2003. Social Movements and Networks: Relational Approaches to Collective Action. Oxford University Press: Oxford.Dowding K. 1995. Model or metaphor? A critical review of the policy network approach. Political Studies43: 136158. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-

9248.1995.tb01705.xFolke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J. 2005. Adaptive governance of socialecological systems. Annual Review of Environmental Resources30:

441471.Goldstein J. 1999. Emergence as a construct: history and issues. Emergence: Complexity and Organization 1: 4972.Hirst P. 2000. Democracy and Governance. In Debating Governance. Authority Steering and Democracy, Pierre J (ed.). Oxford University Press:

Oxford.Holland PW, Leinhardt S. 1981. An exponential family of probability distributions for directed graphs (with discussion).Journal of the American

Statistical Association76: 3365.Hunter D. 2007. Curved exponential family models for social networks. Social Networks29: 216230. DOI: 10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.005Jordan A, Wurzel RKW, Zito A. 2005. The rise of new political instruments in comparative perspective: has governance eclipsed government?

Political Studies53: 477-496. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00540.xKlijn H, Koppenjan JFM. 2000. Public management and policy networks. Foundations of a network approach to governance. Public Manage-

ment2: 135158.Kooiman J. 1993. Modern Governance. New GovernmentSociety Interactions. Sage: London.Kooiman J. 2003. Governing as Governance. Sage: London.Laumann EO, Knoke D. 1987. Organizational State: Social Change in National Policy Domains. University of Wisconsin Press: Chicago, IL.Marsh D (ed.). 1998. Comparing Policy Networks. Open University Press: Buckingham.Olsson J. 2009. Sustainable development from below: institutionalizing a global idea-complex. Local Environment 14: 127138. DOI:

10.1080/13549830802521436Ostrom E. 2009. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of socialecological systems. Science325: 419422.Pattison PE, Wasserman S. 1999. Logit models and logistic regressions for social networks. II. Multivariate relations. British Journal of

Mathematical and Statistical Psychology52: 169194.

Peters GB. 1998. Policy networks: myth, metaphor and reality. In Comparing Policy Networks, Marsh D (ed.). Open University Press:Buckingham; 2132.

Pierre J (ed.). 2000. Debating Governance. Authority, Steering and Democracy. Oxford University Press: Oxford.Pierre J, Peters GB. 2005. Governing Complex Societies: Trajectories and Scenarios. Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke.Prell C, Hubacek K, Reed M. 2009. Stakeholder analysis and social network analysis in natural resource management. Society and Natural

Resources22(6): 501518. DOI: 10.1080/08941920802199202Rhodes RAW. 1996. The new governance: governing without government. Political Studies44(3): 652677. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.

tb01747.xRhodes RAW. 1998. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability. Open University Press: Buckingham.Richardson J. 2000. Government, interest groups and policy change. Political Studies48(5): 10061025.Robins G, Pattison P, Kalish Y, Lusher D. 2007a. An introduction to exponential random graph models (p*) models for social networks. Social

Networks29: 173191. DOI: 10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.002

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

11/12

Exploring the Composition of Communication Networks of Governance 145

Copyright 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and ERP Environment Env. Pol. Gov.20, 135145 (2010)

DOI: 10.1002/eet

Robins G, Snijders T, Wang P, Handcock M, Pattison P. 2007b. Recent developments in exponential random graph (p*) models for socialnetworks. Social Networks29: 192215. DOI: 10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.003

Snijders T, Pattison PE, Robins G, Handcock M. 2006. New specifications for exponential random graph models. Sociological Methodology36:99153. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9531.2006.00176.x

Snijders T, Steglich CEG, Schweinberger M, Huisman M. 2007. Manual for SIENA Version 3.1. University of Groningen ICSDepartment ofSociology/University of Oxford Department of Statistics: Groningen.

Stoker G. 1998. Governance as theory: five propositions. International Social Science Journal155: 1728.Stokman FN, Zeggelink EPH. 1996. Is politics power or policy oriented? A comparative analysis of dynamic access model in policy networks.Journal of Mathematical Sociology21: 77111.

Thatcher M. 1998. The development of policy network analyses. From modest origins to overarching frameworks.Journal of Theoretical Politics10: 389416.

Thompson G. 2003. Between Hierarchies and Markets: the Logic and Limits of Networked Forms of Organization. Oxford University Press: Oxford.Toikka A. 2009. Local networked governance and the environmental policy process environmental strategy drafts in the City of Helsinki,

Finland. In Urban Governance, Eckhardt F, Elander I (eds). Berliner: Berlin: 7192.van Kersbergen K, van Waarden F. 2004. Governance as a bridge between disciplines: cross-disciplinary inspiration regarding shifts

in governance and problems of governability, accountability and legitimacy. European Journal of Political Research 43: 143171. DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00149.x

Wasserman S, Faust K. 1994. Social Network Analysis. Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.Wasserman S, Pattison PE. 1996. Logit models and logistic regressions for social networks. I. An introduction to Markov graphs and p*.

Psychometrika61: 401425.Yli-Pelkonen V, Kohl J. 2005. The role of local ecological knowledge in sustainable urban planning: perspectives from Finland. Sustainability:

Science, Practice, and Policy1: 314.

-

7/27/2019 Caso Helsinski

12/12

Copyright of Environmental Policy & Governance is the property of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. / Business and its

content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's

express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.