Cash Flow Analysis.pdf

-

Upload

njenga-albert -

Category

Documents

-

view

64 -

download

14

Transcript of Cash Flow Analysis.pdf

Advanced Commercial Lending

Cash Flow Analysis

Omega Performance Corporation is a global consulting and training firm that increases the profitability of financial services institutions by improving the performance of their people.

Omega Performance helps financial institutions reach new levels of performance by integrating intensive skill development, comprehensive learning systems, and a motivational learning environment to create a positive, lasting behavioural change.

Since 1976, more than two million financial service professionals from over 2,500 global financial institutions have completed Omega Performance programmes in credit and risk management, and service, sales and sales management.

Omega Performance’s clients include financial service organisations of all sizes in North America, Europe, and the Asia/Pacific region.

N O T I C E This publication is protected by copyright and is licensed to be used by a single individual only.

It is illegal to reproduce this training system or any part of it in any way, to share these materials, or to lend or rent them to anyone else.

Copyright © 1989–2013 by Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

Omega Performance 2nd Floor 30-32 Mortimer Street London W1W 7RE United Kingdom

+44 (0)20 7017 7069

www.omega-performance.com [email protected]

Credit Skills Development Helpdesk

Available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

+44 (0)20 7017 7065

0113 UK-En

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Table of Contents iii

TTaabbllee ooff CCoonntteennttss Start -------------------------------------------------------------- 1

Unit 1: Principles of Cash Flow Analysis ------------------- 9 Section 1: What Is Cash Flow? --------------------------- 11

Section 2: A Three-Layer Approach to Cash Flow Analysis --------------------------------------------------- 21

Unit 2: Three Cash Flow Formats -------------------------- 31 Section 1: Quick Cash Flow ------------------------------- 33

Section 2: Cash Flow Statement------------------------- 47

Unit 3: Financial Drivers of Cash Flow ------------------- 53 Section 1: Change in Sales ------------------------------- 55

Section 2: Changes in Days on Hand ------------------- 71

Section 3: Change in Margins ---------------------------- 91

Section 4: Investment in Non-current Assets and Other Significant Uses of Cash Flow ---------------- 109

Unit 4: Nonfinancial Drivers of Cash Flow ------------- 129 Section 1: Four Critical Management Areas --------- 131

Section 2: An Example of Layer Three Analysis ----- 135

Cases -------------------------------------------------------- 159 Shepherd Ltd ---------------------------------------------- 160

Karr Photo Equipment & Supplies Ltd ---------------- 170

Appendix ---------------------------------------------------- 183 Direct Cash Flow ------------------------------------------ 183

Job Aids ----------------------------------------------------- 205 The Decision Strategy ------------------------------------ 206

Job Aid: IFRS Statement of Cash Flows -------------- 207

Job Aid: Financial Drivers of Cash Flow --------------- 209

Job Aid: Four Critical Management Areas ------------ 213

Job Aid: Direct Cash Flow Constructions ------------- 214

Job Aid: Cash Flow Summary Tips --------------------- 217

Job Aid: Target Cash Flow Analysis -------------------- 218

Quick Cash Flow Worksheet ---------------------------- 219

Financial Drivers Worksheet ---------------------------- 220

Cash Flow Summary Worksheet ----------------------- 221

Glossary ------------------------------------------------------ 223

iv Cash Flow Analysis CFA.0.000.0113.CSD.IFRS.UK.doc © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Start 1

SSttaarrtt WWhen Alpha Ltd developed several new products, its

sales grew 30% in one year. After years of stability, Alpha

suddenly needed more space, more equipment, more

employees, better invoicing and financial information,

and more cash. All of Alpha’s banks were eager to

finance the growth, but only one anticipated that Alpha

would need more financing and a longer repayment

period than the company thought. Alpha now has a new

lead financing relationship.

CCaasshh FFllooww AAnnaallyyssiiss

Builds on your understanding of a company’s asset conversion cycle.

Tests your preliminary assessments of its financial strength.

Provides a foundation for your projections of borrowing need and repayment ability.

CCaasshh FFllooww AAnnaallyyssiiss aanndd tthhee DDeecciissiioonn SSttrraatteeggyy Before continuing, review the Decision Strategy job aid on the following page to see where cash flow analysis fits into the lending process. The job aid also appears in the Job Aids section of this module.

Cash flow analysis is an important component of repayment source analysis because it yields answers to the following questions:

Has the borrower’s historical cash flow from internally generated sources been sufficient to meet its cash flow requirements?

How much annual debt service would the borrower’s cash flow support if future cash flow amounts were consistent with historical cash flow amounts?

How much could future cash flow shrink and still be sufficient, or how much will cash flow need to increase over historical levels in order to meet needs including debt repayment?

What financial and non-financial risks have had the greatest impact on the customer’s need to borrow and ability to repay?

2 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

The Decision Strategy

Opportunity assessment

Prospecting Does the prospect match the institution’s profiles?

If the prospect is a current customer, can the relationship be expanded?

Identify opportunities Review the prospect’s strategic objectives and financial structure.

What immediate and long-term needs exist for lending or non-lending services?

Preliminary analysis

Preliminary assessment What is the specific opportunity? Is the opportunity legal and within your institution’s policy?

Are the terms logically related? Do the risks appear to be acceptable?

Identify borrowing cause What caused the need to borrow? How long will the borrowed funds be needed?

Repayment source analysis

Industry and business risk analysis What trends and risks affect all companies in the borrower’s industry?

What risks must the borrower manage successfully in order to repay the lending facility?

Financial statement analysis What do the financial statement trends show about the borrower's management of the business?

What trends will influence the ability to repay?

Facility packaging

Summary and recommendation What are the major strengths and weaknesses of the lending situation? Should a lending facility be

granted?

Facility structuring and negotiation What are the appropriate facility, security, pricing, advance method, documentation, and covenants?

Facility management

Facility monitoring Is the borrower performing as expected? What caused variations?

What are the risks to repayment? How can you protect the institution’s position?

Cash flow analysis and projections Will the business have sufficient cash to repay the lending facility in the proposed

manner? Which risks will have the greatest impact on its ability to repay?

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Start 3

Armed with these insights, you will be able to proceed in the lending process:

To perform sensitivity analysis on important components of cash flow.

To project cash flow and repayment ability more reliably.

To anticipate risks you will want to manage in your loan structure and covenants.

YYoouu WWiillll BBee AAbbllee ttoo .. .. ..

Evaluate the sufficiency of a borrower’s historical internally generated cash flow to meet its future cash flow needs, using various formats for cash flow, including:

Quick cash flow (an indirect method consistent with traditional cash flow and EBITDA approaches)

Indirect Statement of Cash Flows (one of the formats provided when statements are prepared under IFRS)

Apply a deliberate, three-layer approach to cash flow analysis:

Identify the cash flow formats that will be used for your analysis. Determine the significance of four financial drivers to each

borrower. Analyse critical management areas that affect cash flow.

Unit 1, Principles of Cash Flow Analysis, covers the cash flow basics, including the distinctions between net profit and cash flow and the types of cash flow. The unit also introduces the three-layer approach to cash flow that will be explained in detail throughout this module.

Unit 2, Cash Flow Formats, discusses Layer One analysis, including quick cash flow and the statement of cash flows. Various job aids and worksheets will help you understand how to construct and interpret these cash flow formats to help you determine financing requirement and repayment ability.

Unit 3, Financial Drivers of Cash Flow, describes how to uncover the four financial drivers in a borrower’s financial statements, as well as how to measure and evaluate the effect of the drivers on cash flow. This unit introduces the Financial Drivers of Cash Flow job aid and the Financial Drivers worksheet to help you perform a Layer Two analysis.

Unit 4, Nonfinancial Drivers of Cash Flow, teaches Layer Three analysis. It explains how management decisions in the four critical areas of a company’s financial performance – sales, operating cycle, expenses, and capital investment cycle – affect cash flow, and describes an analytical process for evaluating the nonfinancial drivers of cash flow – economic factors, industry factors, business strategy, and management actions.

4 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

Appendix, which presents the Direct Statement of Cash Flows. IFRS and UK GAAP have two acceptable formats, the indirect and direct methods. The majority of accountants use the indirect method. This appendix explains how the Direct Statement of Cash Flows is calculated and how to analyse the Direct Statement of Cash Flows. The appendix is for your reference and will not be part of the assessment.

UUsseeffuull PPrriioorr LLeeaarrnniinngg Each module has been designed so that it can be undertaken on a standalone basis. Nevertheless it is recognised that for anyone new to a lending role there is a preferred order of study. In this respect you may find it useful, before beginning this module, to have covered the following skills or knowledge:

Understanding of the basic principles of accrual accounting, including an understanding of the connections between the income statement (profit and loss accounts) and the statement of financial position (balance sheet).

Knowledge of the meaning and implications of the following terms:

Asset conversion cycle Operating cycle Capital investment cycle Trading assets and trading activities Trading asset financing need Industry risk factors Business strategy

These subjects are covered in the following modules: Opportunity Assessment, Borrowing Causes, Industry Risk Analysis, Business Risk Analysis, and Financial Statement Analysis.

BBee AAwwaarree TThhaatt .. .. .. The following conventions are used in this module:

Practise opportunities: Some paragraphs are marked with a question icon (Q) and followed by questions and blank spaces. These are learning and practise opportunities to help you understand and apply the material in this module. Please write your answers in the spaces below the questions, and then compare your responses to the answers that follow the spaces, which are marked with an answer icon (A).

Sidebars: Special boxes offer additional details, background information, and focused examples for those who want more detail than is available in the mainstream content.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Start 5

Formulas: All formulas are set apart with a calculator icon. This will make it easy for you to find and review formulas when you need to use them.

Points of emphasis: Essential information is emphasised with the arrow icon.

Dates: In financial statements, historical years are presented with “Y dates”: 20Y1, 20Y2, 20Y3 and so on. The first year of the financial statement is represented as 20Y1, year two as 20Y2 and so on. Future years and projected financial statements use “P dates”; 20P1 represents future year or projected year one, 20P2 indicates projection year two, etc., in the future. These dates do not correlate to actual years, but to the specific sequence of years in the example or case. Think of 20Y1 as “year one”, 20Y2 as “year two” of the case, and so on.

Numbers in brackets: Brackets around a figure generally indicate a negative number. On cash flow formats, brackets around a figure indicate a use of cash.

Financial statement presentation: Financial statement data are generally presented in order of descending dates, from left to right, with the most current year at the left. International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) allow a variety of financial statement presentation formats; we have selected a single format for this programme for consistency. While you may see a variety of formats in practise, the content of the accounts will comply with the applicable accounting standard, so the format selected by the borrower for its financial statements should not affect your analysis results. Always read the notes to the financial statements to understand the accounting standards which have been applied.

Worksheet presentation: Most lending organsations use computer-based statement spreading systems that reorganize the accountant’s financial statements for analysis, and in most cases these programs will show the financial statement spreads, ratios, and cash flow in ascending order, with the earliest date at the left and the most recent year at the right—the opposite of the original financial statement. The worksheets used in this program present information in the order in which you would see it in a spread—earliest year at the left, most recent year and projected years ascending to the right.

Financial terminology: As new terms are introduced and defined, the term used in IFRS appears first, in boldface, and other terms commonly used to mean the same thing are also presented. From that point forward in the module, only the preferred IFRS term is used.. The table that follows shows some of the differences in terminology you may encounter.

6 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

Previous terminology IFRS terminology used here

Balance sheet Statement of financial position

Profit and loss accounts Income statement, or statement of comprehensive income

Cash flow statement Statement of cash flows

Debtors Trade debtors or trade accounts receivable

Creditors Trade creditors or trade accounts payable

Turnover Sales, revenue, or sales revenue

Rounding: When calculations are performed in this module, numbers are rounded to the nearest significant digit. For example, if a calculation yields a value of 95.4567:

Round the value at two decimal places to show pounds and pence. Since the third decimal place is greater than or equal to 5, you would round the second decimal place up to 6, yielding a value of £95.46.

Round the value at no decimal places to show whole pounds. Since the first decimal place is less than 5, ignore everything to the right of the decimal and round down to £95.

On the job, you will use your judgment or your organisation’s policy to guide you in determining the significant digit for rounding purposes. Significance depends on what you are calculating and how you will use the number. In this module, we will use the following rounding convention:

Pounds are rounded to the nearest whole pound. If the amounts are expressed in £000s, figures are rounded to the nearest thousand.

Accounting Standards: Reference in these materials to any accounting standard is to International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) as implemented in an International Accounting Standard (IAS) as of December 2010, unless the materials, either directly or implied, indicate otherwise. Accounting standards are studied in order to introduce you to the foundations upon which accounting practises and procedures are built. Standards are not studied in detail but rather at a level that allows you to see, in reasonably simple terms, why and how accountants treat various accounting matters as they do. Since any reference in these materials to an accounting standard is to an international standard, the materials can be used in any jurisdiction that has harmonised its accounting standards with international standards.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Start 7

GGlloossssaarryy A glossary of terms is provided at the end of this module explaining terminology used in this programme that may be unfamiliar to you. Refer to this glossary as needed during your study.

BBee SSuurree ttoo HHaavvee .. .. .. Before you begin this module, be sure to have the following items on hand:

Pencil

Calculator

8 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 9

1 U

N I

T

PPrriinncciipplleess ooff CCaasshh FFllooww AAnnaallyyssiiss

When you have completed Unit 1, you will be able to:

Distinguish between net profit and cash flow

Distinguish between cash flow that is the result of profit and cash flow that is the result of changes in accounts on the statement of financial position, independent of profit or loss

Describe a three-layer approach to cash flow analysis that frees the analyst from dependence on a particular format of cash flow

Describe four financial drivers of cash flow

Cash flow is what repays loans. The concepts in this unit will provide you with an essential foundation on which to analyse cash flow, regardless of whether or not you are expected to actually construct a cash flow statement.

This unit contains two sections that will help you understand the importance of cash flow.

Section 1 defines cash flow and discusses how knowing the two types of cash flow can help you to make better decisions about borrowing and loan repayment.

Section 2 explains the three-layer approach to cash flow analysis, which includes exposing cash flows, analysing the financial drivers, and recognising qualitative factors affecting cash flow.

10 Cash Flow Analysis CFA.1.1.000.0113.CSD.IFRS.UK.doc © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 11

SSSeeeccctttiiiooonnn 111 WWhhaatt IIss CCaasshh FFllooww?? CCaasshh FFllooww IIss aa MMeeaassuurree ooff CCaasshh IInnffllooww aanndd OOuuttffllooww iinn aannyy PPeerriioodd Cash flow does not equal net income, since there are timing differences between cash receipt and disbursements and accrual accounting recognition of income and expenses. In addition, there are cash outlays and receipts – such as capital expenditures, dividends, and asset sales – that are not reported as income or expenses. Cash flow statements must combine cash flows recognised on the income statement with those on the statement of financial position.

CCaasshh FFllooww IIss tthhee CChhaannggee iinn CCaasshh Cash flow is the term lenders use to identify the increases and decreases in a borrower’s cash and cash equivalents. The key is to understand the receipts and disbursements of cash that occur beneath the surface of accrual accounting. The actual net change in cash and cash equivalent (such as marketable securities) balances from one financial statement date to the next is the sum of all the increases and decreases, and is less revealing than the various increases and decreases and what caused them.

Remember the basic equation of financial accounting:

AAsssseettss == LLiiaabbiilliittiieess ++ SShhaarreehhoollddeerrss’’ FFuunnddss

According to the principle of double entry accounting, when one part of the basic accounting equation changes, one or more of the other elements must automatically change so that the equation will remain, always, in balance. Cash flow analysis regards this process as occurring through changes in the cash account. In real life this will frequently not be the case (a purchase of stock may be financed, for an example, by an increase in creditors with no direct impact on the cash balance), but even transactions which have no immediate effect on cash will have a potential impact. By concentrating on this potential change in cash, our attention can more easily be focused on the underlying cash impact of accounting and management actions.

We can restate the basic equation above as:

CCaasshh ++ OOtthheerr AAsssseettss == LLiiaabbiilliittiieess ++ SShhaarreehhoollddeerrss’’ FFuunnddss

12 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

And, isolating the cash account, this becomes:

CCaasshh == LLiiaabbiilliittiieess ++ SShhaarreehhoollddeerrss’’ FFuunnddss –– OOtthheerr AAsssseettss

Let’s look at an example of using the cash account to balance the basic accounting equation:

Cash = Liabilities (Creditors)

+ Shareholders’

Funds –

Other Assets (Stock)

Cash Flow Impact

Sources of cash

Uses of cash Net change in cash account

1. A company begins operations with an initial shareholder investment of £50 deposited in the bank.

50 = 0 + 50 – 0 50 0 0

2. It purchases £60 of stock from suppliers, using £10 in cash from the deposited shareholders’ funds; the remaining £50 is purchased on credit.

40 = 50 + 50 – 60 0 (10) (10)

3. Work costing £15 is carried out on the stock, so its value increases by the same amount. The work has not yet been paid for, and so increases accrued expenses (for example, wages payable). It is a potential (but not yet an actual) use of cash.

40 = 65 + 50 – 75 15 accrued

wages (15) increase in

stock 0

4. The company pays its workers their accrued wages of £15 and also pays other suppliers £15. This is now a real (and no longer a potential) use of cash. The cash balance declines by £30.

10 = 35 + 50 – 75 0 (30)

(15) wages (15) suppliers

(30)

5. Stock, valued at £50 is sold for £60. Cash sources therefore total £60, comprising £50 from the reduction in stock (stock is reduced by £50) and £10 profit (shareholders’ funds increase by £10). The cash flow impact is therefore:

70 = 35 + 60 – 25 60

50 stock 10 profit

0 60

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 13

When creditors (a current liability) increase, those creditors are, in effect, lending money to the company. If the ‘loan’ is to finance (as in the above example) the purchase of stock, the cash account (in terms of cash held at the bank etc.) will not change at this time, BUT the ‘loan’ will have to be repaid in the future, and the creditor will normally expect to receive payment in cash. The cash flow analysis therefore shows the increase in creditors as a source of cash and the corresponding increase in the asset (in this case, stock) as a use of cash. Thus an increase in a liability account is a source of cash (think of it as somebody lending money to the company), and an increase in an asset account is a use of cash (think of it as the company using ‘cash’, potential or actual, to convert it into another type of asset).

Using the same logic you will see that a reduction in a liability is therefore a use of cash, equivalent to the company repaying a loan – the creditor receives cash in settlement of the debt. A reduction in an asset is also a source – the company is converting the materials and services it has used to make the asset into cash received (or to be received) from its customers.

When these two events or transactions occur in the same period and in the same amount, the cash account balance will not change. The increase in stock, a use of cash, is offset by the increase in creditors, a source of cash. On the surface, it appears that nothing has affected the cash balance; underneath the surface, cash flows. The purpose of cash flow analysis is to uncover these ‘hidden’ changes, to show which items and transactions have the biggest impact on the cash flow of the company.

Use this chart to help you remember sources and uses of cash:

Increase Decrease

Assets (Use) Source

Liabilities and Equity Source (Use)

14 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

Try applying the chart to the following events. For each one, decide what cash flow change is necessary to keep the basic accounting equation in balance, if nothing else happens

1. The borrower makes a sale on credit so that debtors increase.

2. The borrower repays a short-term loan from the bank.

3. The borrower’s stock level falls to a seasonal low point.

4. The borrower makes a profit after taxes during the period.

1. An increase in an overall debtor balance over a period means cash is being used by the company to make a ‘loan’ to the debtors. Instead of receiving cash in exchange for its sales, it agrees to be paid later, so an increase in debtors is a negative cash flow or a use of cash. However, from a standing start (as indicated in this question), a sale on credit to a customer is cash neutral, it has neither an outflow nor an inflow of cash.

2. A decrease in a loan means cash would go down to keep the accounting equation in balance, so a decrease in loans is a negative cash flow or a use of cash.

3. A decrease in stock means cash would go up (stock is being sold to customers) to keep the accounting equation in balance, so a decrease in stock is a positive cash flow or a source of cash.

4. An increase in retained earnings means cash would go up (profits have been made on the sale of products) to keep the accounting equation in balance, so the increase in retained earnings is a positive cash flow or a source of cash.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 15

OOnnllyy CCaasshh RReeppaayyss LLooaannss When evaluating a borrower’s repayment ability, the lender must answer these questions:

When will the borrower generate enough cash to repay the loan?

How will the borrower generate that cash – what combination of positive and negative cash flows will result in the required amount of cash?

Can you be sure the cash will not be needed in the business for something other than loan repayment?

You will be able to answer these questions reliably by carefully identifying the underlying cash flows and analysing what causes them. During the process, avoid three common mistakes or myths that can mislead lenders.

Myth No. 1: Net profit will find its way into the cash account and be available to repay your loan. After all, net profit is a positive cash flow and a source of cash, and a very encouraging one at that since it signifies the economic viability of the company.

Reality: Some or all of the positive cash flow from net profit is usually offset by negative cash flows such as increases in debtors, stock, or long-term assets, especially when the borrower’s sales are growing either year on year or seasonally; most businesses require more assets to support more sales. In addition, some debtors may not pay as promised.

Myth No. 2: Loans can be repaid when debtors are collected. After all, a decrease in debtors is a positive cash flow and a source of cash.

Reality: Many times when debtors are collected, new credit sales immediately result in new debtors, so the debtors balance does not decrease. The cash collected is immediately reinvested in more debtors or more stock and is not available to repay your loan. Only when the debtors balance decreases is cash available to repay debt.

Myth No. 3: Depreciation and amortisation expense results in cash that is available for loan repayment. After all, depreciation and amortisation expense is a positive cash flow and a source of cash from two perspectives:

16 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

Depreciation and amortisation is a noncash expense, so the positive cash flow represented by net profit is actually greater than the net profit on the accrual basis income statement. Hence, it is correct to add the depreciation and amortisation expense for that period back to the net profit for the period to identify the potential cash flow from profitability.

Depreciation and amortisation expense for the period is carried to the statement of financial position and added to the accumulated depreciation and amortisation account, a contra account that reduces the balance of net long-term assets. This reduces the asset balance and is a positive cash flow.

Reality: This positive cash flow is often offset by the need to acquire replacement long-term (or short-term) assets. As a result, net total assets don’t necessarily decrease, and the cash flow from depreciation and amortisation is not necessarily available for debt repayment.

Remember:

Net profits don’t repay loans because the potential cash flow often is used in increasing assets.

Debtor collection repays loans only if the balance of debtors decreases.

Depreciation and amortisation expense repays loans only when the balance of net long-term assets decreases.

Does an increase in depreciation expense increase a borrower’s cash flow (exclude the impact on taxes)?

No. The increase in depreciation expense reduces profit, so when you add the two, you have the same amount of cash flow you had before, except for a possible reduction in income taxes. Depreciation is not a receipt of cash.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 17

TTwwoo TTyyppeess ooff CCaasshh FFllooww Your evaluation of a company’s repayment ability will be more reliable if you understand that there are two types of cash flow, and that each type is best suited for repaying a different kind of loan.

Type A: Cash flow from profit is the best source of repayment for long-term loans. This is often more broadly described as net income plus depreciation or as EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation) minus actual payments of interest and taxes.

Type B: Cash flow from (temporary) shrinkage of assets is the best source of repayment for seasonal, short-term loans. Even if a company is breaking even, it can still release Type B cash flow. If it is loss-making, those losses may absorb some (or all) of the cash released by asset shrinkage.

Financing Need Best Type of Cash Flow

When you consider financing for: Long-term assets Permanently higher levels of

core current assets Replacement of equity or other

long-term liabilities

Your borrower will only be able to repay if: Cash flow from profits plus

depreciation and amortisation consistently exceeds the amounts needed for long-term assets and to support permanent growth in trading assets (debtors and stock)

You need Type A cash flow.

When you consider financing for: A temporary or seasonal

increase in debtors or stock Any other short-term timing

difference in cash inflows and cash outflows

Your borrower will be able to repay you when: Trading assets shrink back to a

base level Short-term timing differences

reverse You can be repaid from Type B cash flow, even if the borrower is not making a profit, provided it is not losing money or spending the borrowed funds for other things.

18 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

OOvveerrttrraaddiinngg

A company that is growing rapidly will typically need to finance higher levels of assets. If its profitability is weak or marginal, however, it may not be able to generate sufficient Type A cash flow (cash flow from profit) to support such financing, making it difficult to justify granting a lending facility. This condition is often referred to as overtrading. These situations are usually best supported with additional equity investments.

Try matching the type of cash flow best suited to repay loans that have the following borrowing causes:

1. Financing an increase in debtors due to the borrower offering all its customers longer sales terms from this day forward.

2. Financing a large stock purchase to take advantage of a one-time discount offered by the supplier.

3. Financing the acquisition of equipment to replace worn out, obsolete equipment.

1. Type A cash flow will be needed. Because the new sales terms will be offered permanently, debtors are not likely to shrink. As a result, there may not be any Type B cash flow.

2. Type B cash flow, from the shrinkage of the stock to its normal level, will be able to repay this loan, even if the borrower only breaks even on the sales. No Type A cash flow is needed to repay this loan.

3. Type A cash flow will be required to repay this loan. Type B cash flow may provide a secondary source of repayment, but expenditures in the capital investment cycle are expected to be repaid from profit over several operating cycles.

SSuummmmaarryy

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 19

Cash flow is the activity that occurs beneath the surface of the actual change in cash and beneath the surface of accrual accounting.

Cash flow from profit is desirable, but the total is not necessarily the capacity of the company to pay debt because other cash flow sources and uses intervene.

Increases in assets are negative cash flows (uses of cash), and increases in liabilities and equity accounts are positive cash flows (sources of cash).

Identifying those underlying positive and negative cash flows, as well as what causes them, will help you make decisions about how much and when a company will need to borrow and how and when it will be able to pay you back.

When considering the most desirable repayment sources for loans, look for the two types of cash flow:

Type A cash flow is from profits plus depreciation and amortisation that exceed intervening uses of cash. Some lenders define this more broadly as EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes plus Depreciation and Amortisation). Look for Type A cash flow to repay loans for long-lived assets and permanent increases in core trading assets.

Type B cash flow is from temporary or seasonal shrinkage of assets, such as stock or debtors. Look for Type B cash flow to repay seasonal or short-term loans, even when the borrower might only be breaking even.

NNeett PPrrooffiittss DDoo NNoott NNoorrmmaallllyy EEqquuaall CCaasshh FFllooww

20 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 21

SSSeeeccctttiiiooonnn 222 AA TThhrreeee--LLaayyeerr AApppprrooaacchh ttoo CCaasshh FFllooww AAnnaallyyssiiss

PPeeeelliinngg tthhee OOnniioonn Getting beneath the change in cash from one statement of financial position to the next is like peeling the layers of an onion, always asking ‘Why?’ until you’ve reached the core.

Peeling the onion deliberately each time you need to thoroughly understand a borrower’s current and future repayment ability will:

Help you focus on the most important components of each borrower’s cash flow.

Help you to discover the most significant causes of positive and negative cash flows.

Provide insights you need to anticipate future cash flows.

LLaayyeerr OOnnee:: EExxppoossee CCaasshh FFlloowwss The first layer in an effective cash flow analysis is to peel away the effects of accrual accounting and expose all material positive and negative cash flows.

Accrual basis financial statements match revenues and expenses but obscure cash flows.

The accrual-based statement of financial position, income statement, and statement of changes in equity prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are intended to match revenues and expenses, not cash receipts and disbursements. Here are some examples: Income statement accounts report revenue when it has been earned,

not when customers pay; they report expenses when incurred, not when bills are paid.

For some kinds of expenses, such as cost of goods sold, ‘incurred’ means in the period when the associated revenues are recognised, not necessarily when the expense activity, such as production, took place.

Production costs are accumulated in the stock account until the goods are sold, which may be long after they were produced and suppliers and workers were paid.

Although matching of revenue and expense is very important to a lender’s understanding of the accumulated performance and future economic potential of the company, it does obscure the amount and timing of cash inflows and outflows that determine loan repayment ability.

Lenders and accountants have developed a variety of methods and formats for reporting cash inflows and outflows so that lenders and other users of financial statements can more efficiently and reliably measure the amounts of cash flows and analyse their components and causes.

22 Cash Flow Analysis CFA.1.2.000.0113.CSD.IFRS.UK.doc © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

In this module, you will learn to identify and analyse various cash flow formats.

You will not usually need to construct cash flow statements; borrowers will provide them. Nor will you have to perform Layer One calculations; software packages are available to perform these calculations when the information is not provided. However, in order to analyse cash flow, you will need to understand how a cash flow report is derived from the statement of financial position, income statement, and statement of changes in equity. So, we will explain and show you how the Layer One formats are put together, even if you won’t ever have to calculate them yourself.

CCaasshh FFllooww RReeppoorrttiinngg

11.. Following are some of the more common formats used in presenting cash flows: Quick cash flow, also known as indirect or traditional cash flow, is the easiest to construct, if you do not receive a cash flow statement from the borrower. It starts with the sources of cash flow from net profits and depreciation and amortisation on the income statement, and then adjusts for the major categories of cash flow use that show up on the statement of financial position: change in trading asset financing need, fixed assets, dividends, and debt service. Quick cash flow is an example of an indirect or ‘bottom-up’ approach, so called because it starts at the bottom of the income statement with net profit. Unit 2, Section 1, of this module demonstrates how to analyse quick cash flow with a simple worksheet.

22.. Statement of cash flows is the format provided by a company when its financial statements are prepared in accordance with IFRS. It typically organises sources and uses of cash flow into three categories: operating, investing, and financing activities. Its chief advantage is that the borrower provides it for you. It can be done in either a direct or indirect format. Unit 2, Section 2, of this module will show you how to use the indirect statement of cash flows to identify financing requirements or repayment capacity.

Another format, known as “direct cash flow,” is also used on occasion. This format starts with sales as the primary cash inflow and adjusts specific cash and non-cash accounts, including expenses and changes in assets and liabilities. It exposes more detail on the changes to various accounts than other methods. This method is not typically used by accountants; therefore this format is discussed in an appendix to this module, which you have the option of studying. Of note, in the future, IFRS may move to the direct method for completion of the Statement of Cash Flows.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 23

All cash flow formats:

Combine information from the accrual statement of financial position, income statement, and statement of changes in equity.

Remove the effects of accrual accounting.

Show you how cash has flowed into, and out of, the business.

Can be the basis of effective cash flow analysis.

Regardless of the format you use for the Layer One calculation of cash flow, remember that it is only the first step in cash flow analysis. Understanding the Layer One format makes your subsequent analysis easier. You must peel away more layers of the onion to understand what financial and nonfinancial factors are causing the cash flows.

LLaayyeerr TTwwoo:: AAnnaallyyssee FFiinnaanncciiaall DDrriivveerrss Layer Two of cash flow analysis quantifies the effects of major financial factors on cash flow. Four of these are so important to understanding past and future cash flows that we call them the financial drivers.

CChhaannggee iinn ssaalleess

The percentage increase or decrease in sales from one period to the next. If a company’s sales in year 1 are £100,000,000 and in year 2 are £120,000,000, the company’s change in sales has been an increase of 20%. Increases in sales tend to drive similar percentage increases in stock, debtors, and creditors. Over time, increases in sales may also drive increases in spending on non-current assets (also known as fixed assets).

CChhaannggee iinn ddeebbttoorr,, ssttoocckk aanndd ccrreeddiittoorr ddaayyss oonn hhaanndd

The increase or decrease in the number of days in the stock holding period, the debtors collection period, and the creditors payment period from one accounting period to the next. For example, if a company’s debtor days on hand (DDOH) in year 1 are 60 days and in year 2 are 65 days, the number of days in the collection period has increased 5 days. Additional days in the collection period represent a slowdown in collection, and would indicate an increase in actual debtors (unless sales are decreasing) and drive a decrease in cash flow. It is important to consider the sales value and the actual debtors balance movement in such analysis as an increase in the DDOH does not automatically mean a decrease in cash.

Similar analysis techniques can be applied to the stock holding period by calculating change in stock days on hand (SDOH) and to the creditors payment period by calculating creditors days on hand (CDOH).

24 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

CChhaannggee iinn ggrroossss pprrooffiitt aanndd ooppeerraattiinngg eexxppeennssee mmaarrggiinnss

The increase or decrease in expenses as a percent of sales. This can be further broken down into cash cost of goods sold and cash selling, general, and administrative expense (cash means excluding non-cash expenses such as depreciation and amortization). If a company’s cash cost of goods sold as a percent of sales in year 1 is 60% and in year 2 is 57%, the cash expenses have decreased and the gross profit margin has increased by 3% of sales. If that 3% carries to the bottom line net profit, the improved margin drives an increase in cash flow, just as a reduced profit margin drives a decrease in cash flow. The combined effect of changes in cash COGS and cash SG&A expense is often measured by calculating the cash operating profit margin – the percentage of sales that remains after subtracting both cash COGS and cash SG&A. This is sometimes referred to as the cash cushion because it provides a cushion for increases in production or operating expenses and a cushion for interest expense.

Another refinement is to measure EBITDA as a percent of sales, called the EBITDA margin, and then to assess the impact that each expense category has had on the EBITDA margin.

Cash COGS and Cash SG&A

Lenders can focus more closely on the cash required to meet production and other operating costs by considering cash cost of goods sold (cash COGS) and cash selling, general, and administrative expenses (cash SG&A). These terms indicate that non cash expenses for depreciation and amortisation have been excluded.

To calculate cash COGS and cash SG&A, subtract any included depreciation and amortisation from the total. To find the amount of depreciation and amortisation, look on the income statement, or look in schedules that break down cost of goods sold and operating expenses, or check for footnotes. For example, a printing company is likely to classify the depreciation of its printing presses as a cost of goods sold.

Cash COGS is important because when lenders use it to calculate stock and creditor days on hand, they obtain more precise measures of the cash required to support each day in the stock holding period and the cash provided by each day in the creditors payment period. Unit 2 has more about this technique.

Of course, in using EBITDA margin, depreciation and amortisation have already been segregated.

CCaappiittaall iinnvveessttmmeenntt aaccttiivviittiieess ((iinnvveessttmmeenntt iinn nnoonn--ccuurrrreenntt aasssseettss))

The spending for replacement and expansion of fixed assets, net of any proceeds from the sale or disposal of fixed assets. Spending for fixed assets is an application or use of cash. When spending on fixed assets in a period exceeds the depreciation and amortisation expense in that period, we can imagine the use of cash as competing with other potential uses, such as stock increases or loan repayment. Investment in fixed assets drives an immediate decrease in cash flow – although its ultimate intention is clearly to increase cash flow in the longer term.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 25

IInntteerrnnaallllyy ggeenneerraatteedd ccaasshh ffllooww

The first three of these changes (sales, days on hand, and margins) are the only areas of a borrower’s financial performance that produce (or fail to produce) ‘internally’ generated cash flow. Internally generated cash flow is important to the lender because reliable loan repayment depends more on it than on external sources of cash flow such as new debt or equity investments.

Cash flow from sales is determined, in part, by internal production and marketing decisions, days on hand are the result of management responses to purchasing, manufacturing and marketing factors, and margins reflect the management of the cost/revenue mix of the company. All are, therefore, in principle, internally controlled rather than reliant upon intervention from new external sources, or uses, of cash.

Contrasted to this, investment in fixed assets is, by its nature, designed to extend the activities of the company beyond their present level – even if it is a replacement of old equipment by new. In other words the management have decided that to realise opportunities or solve problems, they must expand or replace fixed assets.

The distinction is made to enable the lender to evaluate the ability of the company ‘as is’ to meet its obligations, and/or the need to find a solution to its problems outside the current scope of activities – for example, by buying (or selling) production assets. Identifying the amount, consistency, and trend of the impact that each of the four financial drivers is having sets you up to ask the next round of ‘Why?’ questions, ones that will get you to the heart of cash flow issues: what is causing the changes in sales, days on hands, margins, and capital spending?

LLaayyeerr TThhrreeee:: AAnnaallyyssee QQuuaalliittaattiivvee FFaaccttoorrss Layer Three of an effective cash flow analysis asks those questions that will provide cash flow insights that will tell you what is driving cash flow and what combination of external and management factors is at work.

In this third and deepest layer of analysis, you will answer these questions:

How have economic and industry factors affected the borrower’s cash flow?

Which of the factors that are influencing the financial drivers are within management’s control, and which are not?

How well has management been controlling the financial drivers?

Uncovering the qualitative issues behind the financial drivers is necessary in estimating the amount of cash flow available for future debt service and the sustainability of that cash flow.

26 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

Critical Management Area Financial Driver Analytical Approach

Sales Percentage change in sales How have external factors such as economic trends affected each financial driver?

Which factors are within management’s control, and which are not?

How effective are management’s strategies and actions in managing each driver?

What are the implications for future cash flows?

Operating cycle Change in DDOH, SDOH, and CDOH

Expenses Change in cash COGS and cash SG&A expenses as a percent of sales

Capital investment cycle Spending for fixed assets, net of any proceeds from sale of fixed assets

SSuummmmaarryy A deliberate, three-layer cash flow analysis will improve your ability to identify a borrower’s current capacity to repay debt because the approach will lead you steadily deeper into the reasons for positive and negative cash flows.

Layer One merely exposes or calculates cash flows; this is often done for you in the Statement of Cash Flows included in the financial statements.

Layer Two identifies the cash impact of each of four financial drivers:

Percentage change in sales

Change in days in the holding, collection, and payment periods

Change in margins

Spending for fixed assets

Layer Three goes deeper to analyse the external economic and industry factors and management actions that have influenced the financial drivers.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 27

PPrraaccttiissee EExxeerrcciissee 1. Which of the following most accurately describes the relationship of

cash flow and net profit reported in accrual accounting?

a. Net profit and cash flow are the same b. Net profit is one source of cash flow c. Net profit is always greater than cash flow d. Net profit is always less than cash flow e. None of the above

2. Which of the following are accurate statements about sources and uses of cash flow? 1. An increase in debtors is a positive cash flow 2. An increase in creditors is a positive cash flow 3. Depreciation and amortisation expense do not use cash 4. An increase in net fixed assets is a negative cash flow

a. 1, 2, and 3 b. 1, 2, 3, and 4 c. 2 and 3 d. 2, 3, and 4

3. Which of the following is an objective of accurate and thorough cash flow analysis?

a. To cancel some effects of accrual accounting and expose actual cash inflows and outflows

b. To identify financial results that have influenced cash flow c. To analyse how management decisions have influenced cash flow d. To understand how conditions beyond management’s control

may have influenced cash flow e. All of the above

4. Which of the following is the measurement for change in sales as a financial driver of cash flow?

a. Returns and allowances as a percentage of sales in the most recent period

b. The cash amount of the sales increase or decrease from one period to the next

c. The percentage increase or decrease in sales from one period to the next

28 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

5. Why is the change in sales a significant driver of cash flow?

a. Because all sales result in payments from customers in the same accounting period in which the sale is made

b. Because an increase in sales usually results in a similar cash amount increase in debtors and stock

c. Because an increase in sales tends to cause a similar increase in debtors and stock

6. Which of the following is a way to organise your thinking about management decisions that affect cash flow?

a. Identify the ages of key members of the management team b. Analyse how management decisions have affected sales, the

operating cycle, expenses, and the capital investment cycle c. Find out whether a plan of management succession exists d. Calculate the change in cash and marketable securities from the

beginning to the end of the period of the cash flow e. All of the above

7. Which of the following are accurate statements about Type A and Type B cash flows? (Circle as many as you think are accurate.)

a. Type A cash flow is never used to repay seasonal or short-term debt

b. Type B cash flow, from shrinkage of assets, is always used to repay seasonal or short-term debt

c. Type A cash flow is the best source of repayment for financing of long-lived assets and permanent increases in core trading assets

d. Type B cash flow, from shrinkage of assets, is a good source of repayment for seasonal short-term loans

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Principles of Cash Flow Analysis 29

30 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

AAnnsswweerrss 1. b. Net profit is not the same as cash flow and might be more or less

than cash flow in any period, depending on the amount of noncash expense reported in the income statement and the degree of changes in statement of financial position accounts.

2. d. Increasing a liability (creditors) is a source of cash; increasing an asset (net fixed assets) is a use of cash; and a noncash expense (depreciation and amortisation) is not a use of cash. Only statement 1 is not accurate, because an increase in an asset (debtors) is a use of cash and a negative cash flow.

3. e. All choices are objectives of cash flow analysis. Option a is part of Layer One, option b is part of the quantitative analysis in Layer Two; options c and d are part of the qualitative analysis in Layer Three.

4. c. Analysts use the percentage increase or decrease so that they can apply the same percentage increase or decrease to assets such as debtors and stock and to liabilities such as creditors to isolate how the change in sales affects those statement of financial position accounts.

5. c. When sales increase, higher levels of debtors and stock are typically required. Unless the company changes the average length of its collection period and holding period, the two current asset accounts will increase at the same rate as sales.

6. b. Age of managers and existence of a management succession plan might be important to know, but are not likely to help you organise your analysis of how management decisions affect cash flow. Calculating the change in cash is not very analytical, and can be performed simply by looking at the two statements of financial position without performing a cash flow summary.

7. c and d. Statements a and b are not accurate because Type A cash flow can be used to repay seasonal or short-term debt when profits are strong even when the seasonal cycle is extended and the low point comes later than or is not as low as expected.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Cash Flow Formats 31

2

U

N

I

T

CCaasshh FFllooww FFoorrmmaattss

When you have completed Unit 2, you will be able to:

Identify the amount of the financing requirement or cash flow available for debt service as measured by different cash flow formats:

Quick cash flow (also called indirect or traditional cash flow)

Statement of cash flows prepared according to IFRS

Recognise the benefits of each format to the analysis you are performing.

Recognise the limitations of Layer One analysis and the importance of going on to perform Layer Two and Layer Three analyses before drawing conclusions about repayment ability.

This unit introduces some common formats for measuring and

presenting cash flows and contains the following:

Section 1 presents a simple, indirect method of measuring cash flow and illustrates its use to identify cash flow available for debt repayment and the major categories of cash sources and uses when you have not been provided with a cash flow statement.

Section 2 illustrates the indirect cash flow format, which is the most common option used by accountants for the cash flow presentation required under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), and explains how to use the statements to measure the financing surplus or requirement.

32 Cash Flow Analysis CFA.2.1.000.0113.CSD.IFRS.UK © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Cash Flow Formats 33

SSSeeeccctttiiiooonnn 111 QQuuiicckk CCaasshh FFllooww

WWhhaatt IIss QQuuiicckk CCaasshh FFllooww??

Quick cash flow (also known as traditional cash flow) is a simple Layer

One format that is quick and easy and doesn’t require a computer. Use

quick cash flow as your foundation for Layer Two and Layer Three cash

flow analyses when you:

Are pressed for time

Have not received a statement of cash flows from the borrower

Want to focus on Type A cash flows

Want to focus on the impact of trading asset financing need

If you need to construct a quick cash flow, you can do it on a napkin –

it’s that easy. If you prefer, you can use a worksheet, an example of which

appears on the following page. Take a look at it now.

The quick cash flow worksheet has the following significant features:

It begins with Type A cash flow, which is cash flow from profits, adjusted for non-cash expenses.

It isolates the combined cash flow impact of all changes in trading asset financing need.

It imposes a hierarchy of cash flow uses that puts debt repayment last.

You will notice that the quick cash flow worksheet has columns for multiple years and these years are listed in ascending order from left to right—earliest year on the left, and most recent year on the right—the opposite of the original financial statements. We use this presentation because most lending institutions use statement spreading software that produces reports, ratios, and cash flow information, and most of this software presents the years in ascending order from left to right. This also facilitates adding projected years to the quick cash flow.

Trading Asset Financing Need

Trading asset financing need is the net balance of those current assets and liabilities that change as a

result of business activity and business decisions – rather than as a result of financial decisions. Trading asset

financing need is generally calculated as debtors plus stock, less creditors and accrued expense. Other current

items, such as prepaid expenses or deferred liabilities, may be included if appropriate, but this decision will

depend upon the analyst’s opinion as to whether this will give a more informative and accurate picture of the

factors affecting the company’s behaviour. Debtors and stock may change because of changes in days on hand

or changes in sales. Large increases in stock and/or debtors resulting from overtrading increase risk.

34 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

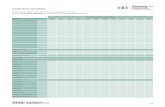

Quick Cash Flow (in £s) Company Name:

+ -

TAFN (U) S

GFA (U) S

Year 1 Year 2 Year 3

Net profit

Plus: Depreciation, amortisation expense

Plus: Inte est expense

Plus decrease (or less increase): Trading asset financing need

Equals: Cash after operating c cle

Plus (or less): Gross non-current assets

Equals: Cash after capital investment cycle

Less: Dividend declared

Equals: Cash available for all debt repayment

Less: Current portion long-term debt (prior year)

Less: Interest expense

Equals: Cash available for other debt repayment

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors

Plus: Stock

Less: Creditors

Less: Accrued expenses

Equals: Trading asset financing need

Closing trading asset financing need

Less: Opening trading asset financing need

Equals: Trading asset financing need Year 1

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors

Plus: Stock

Less: Creditors

Less: Accrued expenses

Equals: Trading asset financing need

Closing trading asset financing need

Less: Opening trading asset financing need

Equals: Trading asset financing need Year 2

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors

Plus: Stock

Less: Creditors

Less: Accrued expenses

Equals: Trading asset financing need

Closing trading asset financing need

Less: Opening trading asset financing need

Equals: Trading asset financing need Year 3

Are any changes in income taxes payable, interest payable, prepaid expenses, investments, or

miscellaneous other accounts large enough to distort quick cash flow?

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Cash Flow Formats 35

Quick cash flow is conservative because it shows the effect on debt

repayment capacity if increases in stock and debtors, non-current assets,

and dividends are allowed to absorb internally generated cash flows.

Debts will only be repaid from internally generated cash flows after those

other uses have been satisfied. With that clarity, lenders and borrowers

can decide if some uses of cash flow will be financed, or if some uses of

cash flow can safely be deferred or reduced.

Let’s look at some examples:

An overdraft facility may be available to provide cash needed for growth in trading asset financing needs. If so, the borrower’s internally generated cash flow may be sufficient to pay for non-current assets and dividends, and to make payments on a scheduled long-term loan.

Lenders may be willing to finance investments in non-current assets, with the result that internally generated cash flow may be sufficient to fund growth in stock and debtors and payment of dividends.

The borrower may be able to reduce expenditures on non-current assets, perhaps by establishing operating leases, or some expenditures may be deferred a year or two without damaging productivity. If so, more internally generated cash flow will be available for debt repayment and other uses.

Sales and Days on Hand Drive Trading Asset

Financing Need

A company’s need to finance trading assets grows for two reasons: the amount of financing required each day

on average and the time for which it is needed.

Amount: If sales grow, either permanently or seasonally, the amount required to finance trading

assets each day increases by the same percentage that sales grew.

Timing: If the operating cycle gets longer or the payment period gets shorter, either permanently or

temporarily, the number of days for which financing for trading assets is required gets longer. This

number of days is the cash flow timing difference.

Cash flow timing difference is the length of the operating cycle less the number of days of spontaneous

financing provided by creditors and accruals. If sales for a company grow 10%, the company’s need for

financing trading assets will also grow 10%, unless there is a change in the cash flow timing difference.

If the cash flow timing difference Then the company’s need for financing trading assets

Gets longer… Will grow by more than the percentage increase in sales

Gets shorter… Will grow by less than the percentage increase in sales

36 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

AAnnaallyyssiinngg QQuuiicckk CCaasshh FFllooww

Study the background information, statement of financial position, and

income statement in Shepherd Ltd, Part I, in the Cases section of this

module, and the Shepherd Quick Cash Flow worksheet that follows.

Then answer the following questions to confirm your understanding of

how to analyse quick cash flow.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Cash Flow Formats 37

Quick Cash Flow (in £s) Company Name: Shepherd Ltd

+ -

TAFN (U) S

GFA (U) S

20Y2 20Y3

Net profit 285 1,792

Plus: Depreciation, amortisation expense 1,765 1,744

Plus: Interest expense 1,430 1,271

Plus decrease (or less increase): Trading asset financing need 11,304 (8,633)

Equals: Cash after operating cycle 14,784 (3,826)

Plus (or less): Gross non-current assets (2,944) (71)

Equals: Cash after capital investment cycle 11,840 (3,897)

Less: Dividend declared (1,068) (1,222)

Equals: Cash available for all debt repayment 10,772 (5,119)

Less: Current portion long-term debt (prior year) (1,374) (1,734)

Less: Interest expense (1,430) (1,271)

Equals: Cash available for other debt repayment 7,968 (8,124)

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors 24,549 17,469

Plus: Stock 25,743 20,519

Less: Creditors 6,937 6,410

Less: Accrued expenses 3,615 3,142

Equals: Trading asset financing need 39,740 28,436

Closing trading asset financing need 28,436

Less: Opening trading asset financing need 39,740

Equals: Trading asset financing need (11,304) 20Y2

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors 17,469 22,233

Plus: Stock 20,519 27,865

Less: Creditors 6,410 8,810

Less: Accrued expenses 3,142 4,219

Equals: Trading asset financing need 28,436 37,069

Closing trading asset financing need 37,069

Less: Opening trading asset financing need 28,436

Equals: Trading asset financing need 8,633 20Y3

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors

Plus: Stock

Less: Creditors

Less: Accrued expenses

Equals: Trading asset financing need

Closing trading asset financing need

Less: Opening trading asset financing need

Equals: Trading asset financing need

Are any changes in income taxes payable, interest payable, prepaid expenses, investments, or

miscellaneous other accounts large enough to distort quick cash flow?

38 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

1. How much were Shepherd’s Type A cash flows in 20Y2? Where do

you find them in the company’s financial statements, and where do

they show up on the quick cash flow worksheet?

2. Why is the change in trading asset financing need in 20Y2,

£11,304,000, added to the Type A cash flows?

3. Why is the change in trading asset financing need in 20Y3,

£8,633,000, subtracted from the Type A cash flows?

4. Why do you think quick cash flow uses the change in gross non-

current assets when computing cash after capital investment cycle?

5. Why does the quick cash flow use £1,734,000 and £1,374,000 for

current portion long-term debt in 20Y3 and 20Y2, respectively?

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Cash Flow Formats 39

1. Shepherd’s Type A cash flows in 20Y2 were £2,050,000. You find

them on the company’s income statement for 20Y2, being careful to

pick up all three amounts for depreciation and amortisation. Profits

are on the first line of Quick Cash Flow worksheet and the sum of

depreciation and amortisation are on the second line. Notice that we

have rounded to the nearest thousand on the worksheet.

2. Shepherd’s trading asset financing need actually decreased

£11,304,000 in the year ending 31/12/Y2. Since a decrease in trading

asset financing need is a source of cash flow, the amount is added on

the worksheet rather than subtracted.

3. In 20Y3, Shepherd’s trading asset financing need increased by

£8,633,000. The increase in trading asset financing need is a use of

cash flow, so the amount is subtracted from Type A cash flows in the

computation of cash after operating cycle.

4. Because quick cash flow specifically includes depreciation and

amortisation expense as a source of Type A cash flow. Using net fixed

assets could overstate the impact of depreciation and amortisation on

cash flow.

5. Because they each represent the amount that was scheduled to be

repaid during the period of the quick cash flow statement. £1,374,000

showed on the notes to the financial statements for 20Y1 as the

amount due to be paid within the next 12 months, which is the period

of the 20X2 quick cash flow.

IInntteerrpprreettiinngg QQuuiicckk CCaasshh FFllooww

Even before going on to Layer Two and Layer Three cash flow analysis, a

lender is able to make some useful interpretations from quick cash flow.

You can:

Compare the amount of cash available for all debt repayment to the principal amortisation and interest for any existing and proposed additional debt.

Consider whether any of the cash uses, such as increases in trading asset financing need or increases in non-current assets, were financed with debt.

Compare the amount of Type A cash flow to each category of cash use.

Compare each line item of use or source to the total of cash flow available for all debt repayment.

Anticipate how future cash flows may be like, or unlike, the historical cash flows.

40 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

These interpretations are components of answering the key Layer One

question: Is cash flow sufficient to repay debt?

Quick cash flow is especially helpful in answering another Layer One

question: What is the impact of the change in trading asset financing

needs? Growth in stock and debtors is what causes overtrading risk. Be

careful not to overlook or underestimate its impact in the evaluation of

debt repayment capacity.

Which of the following interpretations can you reliably make from the

Shepherd Ltd. Quick Cash Flow worksheet? Making some notes of your

calculations will help you see the significance of each interpretation.

1. Without the substantial decrease in trading asset financing need in

20Y2, Shepherd would have been unable to make scheduled debt

payments from internally generated cash flow.

2. Shepherd in 20Y3 was unable to finance its growth in trading asset

financing need with internally generated funds.

3. If Shepherd’s lenders were willing to finance 75% of the growth in

trading asset financing need in 20Y3, Shepherd still would have been

unable to make scheduled payments on long-term debt without

further borrowing.

4. If Shepherd’s increase in gross fixed assets in 20Y3 had been a more

typical £2,000,000, instead of the atypical £71,000, the company’s

cash available for all debt repayment would have been an even larger

negative number, necessitating more new debt.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Cash Flow Formats 41

You can reliably make all four interpretations based on the quick cash

flows for 20Y2 and 20Y3. Here is why:

1. The 20Y2 decrease in trading asset financing need generated

£11,304,000 and cash available for all debt repayment was positive

£10,772,000. Without the cash flow from the lower trading asset

financing need, cash available for all debt repayment would have been

negative £532,000.

2. Internally generated funds were only £3,536,000, which was not

enough to fund the growth in trading asset financing need of

£8,633,000.

3. If lenders have financed 75% of the £8,633,000 growth in trading

asset financing need (perhaps secured by the debtors and stock), that

would bring in £6,474,750 of loan proceeds. However, cash available

for all debt repayment was negative £5,119,000 and scheduled debt

payments were £1,734,000, plus interest expense of £1,271,000.

Shepherd would still have been short by £1,649,250 in making the

debt payments. More borrowing would have been needed.

4. Shepherd’s very low expenditures for non-current assets in 20Y3

minimised the strain on cash flow. If spending had been £2,000,000

instead of the insignificant £71,000, cash available for all debt

repayment would have been negative £7,048,000 (worse by

£1,929,000).

So now we come to the key Layer One question: Is Shepherd’s cash flow

in 20Y2 and 20Y3 sufficient to repay its debt?

We have to say ‘no’, not as the debts are presently structured. Quick cash

flow shows us that Shepherd has insufficient Type A cash flows to pay

dividends and current portion of long-term debt plus interest. Positive

cash flows in 20Y2 are misleading, because they were due almost entirely

to shrinking trading asset financing needs and were therefore not

repeatable in 20Y3.

We can’t be so sure of the answer if we modify the question to ask, ‘Will

Shepherd’s cash flow in the future be sufficient to repay its debt?’

Certainly if cash flow amounts are the same in the future as in the past,

they will be insufficient. However, we can’t reliably anticipate cash flow

without a thorough understanding of Layer Two drivers and Layer Three

issues. We must remember that with all the measuring and thinking about

quick cash flow so far, we are just in Layer One of our analysis.

42 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

SSuummmmaarryy

Quick cash flow is a simple, indirect, Layer One format for cash flow

analysis. Its chief advantages are its:

Simplicity

Focus on Type A cash flow

Focus on trading asset financing need

It is conservative because it imposes a hierarchy of thinking about uses of

cash flow that assumes all uses are satisfied before any cash flow is

available to repay any debt.

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Cash Flow Formats 43

PPrraaccttiissee EExxeerrcciissee

Directions: Use the background information, financial statements and

Quick Cash Flow Worksheet in Karr Photo, Part I, in the Cases section

of this module to complete the following exercise.

44 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

Quick Cash Flow (in £s) Company Name: Karr Photo Equipment and Supplies

+ -

TAFN (U) S

GFA (U) S

20Y2 20Y3

Net profit 246,500 226,630

Plus: Depreciation, amortisation expense 57,250 167,200

Plus: Interest expense 83,210 199,150

Plus decrease (or less increase): Trading asset financing need (1,205,370) (446,930)

Equals: Cash after operating cycle (818,410) 146,050

Plus (or less): Gross non-current assets (568,100) (750,750)

Equals: Cash after capital investment cycle (1,386,510) (604,700)

Less: Dividends declared 0 0

Equals: Cash available for all debt repayment (1,386,510) (604,700)

Less: Current portion long-term debt (prior year) (300,000) (300,000)

Less: Interest expense (83,210) (199,150)

Equals: Cash available for other debt repayment (1,769,720) (1,103,850)

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors 1,613,580 2,471,350

Plus: Stock 3,633,700 7,078,700

Less: Creditors 1,665,620 4,521,630

Less: Accrued expenses 326,830 568,220

Equals: Trading asset financing need 3,254,830 4,460,200

Closing trading asset financing need 4,460,200

Less: Opening trading asset financing need 3,254,830

Equals: Trading asset financing need 1,205,370 20Y2

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors 2,471,350 3,449,770

Plus: Stock 7,078,700 9,364,910

Less: Creditors 4,521,630 7,573,850

Less: Accrued expenses 568,220 333,700

Equals: Trading asset financing need 4,460,200 4,907,130

Closing trading asset financing need 4,907,130

Less: Opening trading asset financing need 4,460,200

Equals: Trading asset financing need 446,930 20Y3

Change in trading asset financing need OPENING CLOSING

Debtors

Plus: Stock

Less: Creditors

Less: Accrued expenses

Equals: Trading asset financing need

Closing trading asset financing need

Less: Opening trading asset financing need

Equals: Trading asset financing need

Are any changes in income taxes payable, interest payable, prepaid expenses, investments, or

miscellaneous other accounts large enough to distort quick cash flow?

© Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved. Cash Flow Formats 45

1. Which major category of cash use or source had the largest impact on

Karr’s cash flow available for all debt repayment in 20Y2? In 20Y3?

2. Based only on the quick cash flow, is Karr’s cash flow sufficient to

repay its debt?

3. If lenders were willing to finance 75% of Karr’s non-current asset

expenditures in 20Y3, how much cash would Karr have raised from

that source, and how would that change your assessment of Karr’s

cash flow?

46 Cash Flow Analysis © Omega Performance Corporation. All rights reserved.

AAnnsswweerrss

1. 20Y2: Change in trading asset financing need, a cash use of

£1,205,370

20Y3: Change in gross long-term investments, a cash use of £750,750

2. No. Cash available for all debt repayment is negative in both years.

3. Using the change in gross non-current assets as the amount of non-

current asset expenditures, Karr Photo would generate £563,063 if