Case Report The Experience of Patients with Schizophrenia Treated...

Transcript of Case Report The Experience of Patients with Schizophrenia Treated...

Hindawi Publishing CorporationCase Reports in PsychiatryVolume 2013, Article ID 183582, 5 pageshttp://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/183582

Case ReportThe Experience of Patients with SchizophreniaTreated with Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation forAuditory Hallucinations

Priya Subramanian,1,2 Amer Burhan,1,2 Luljeta Pallaveshi,1,2 and Abraham Rudnick3

1 Department of Psychiatry, Regional Mental Health Care-London, Western University, London, ON, Canada N6A 4H12 Lawson Health Research Institute, London, ON, Canada N6C 2R53Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver Island Health Authority, Victoria, BC, Canada V8R 4Z3

Correspondence should be addressed to Priya Subramanian; [email protected]

Received 16 April 2013; Accepted 15 May 2013

Academic Editors: J. S. Brar, M. Kellner, and F. Oyebode

Copyright © 2013 Priya Subramanian et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons AttributionLicense, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properlycited.

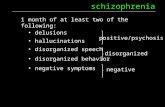

Introduction. Auditory hallucinations are a common symptom experience of individuals with psychotic disorders and are oftenexperienced as persistent, distressing, and disruptive. This case series examined the lived experiences of four individuals treated(successfully or unsuccessfully) with low-frequency (1Hz) rTMS for auditory hallucinations. Methods. A phenomenologicalapproach was used and modified to involve some predetermined data structuring to accommodate for expected cognitiveimpairments of participants and the impact of rTMS on auditory hallucinations. Data on thoughts and feelings in relation tothe helpful, unhelpful, and other effects of rTMS on auditory hallucinations, on well-being, functioning, and the immediateenvironment were collected using semistructured interviews. Results. All four participants noted some improvements in theirwell-being following treatment and none reported a worsening of their symptoms. Only two participants noted an improvementin the auditory hallucinations and only one of them reported an improvement that was sustained after treatment completion.Conclusion. We suggest that there are useful findings in the study worth further exploration, specifically in relation to the role ofan individual’s acceptance and ownership of the illness process in relation to this biomedical intervention. More mixed methodsresearch is required to examine rTMS for auditory hallucinations.

1. Introduction

Auditory hallucinations, that is, the experience of sound inthe absence of external perceptual stimuli, are a commonsymptom of individuals with psychotic disorders such asschizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. The prevalenceof auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia is reported tobe 75% [1]. Many of these individuals experience auditoryhallucinations as persistent, distressing, and disruptive. Upto 30% of individuals with auditory hallucinations respondonly partially or not at all to standard antipsychotic treatment[2, 3]. Shergill et al. [4] concluded in their review of psycho-logical treatments for auditory hallucinations that, althoughthese are of some benefit, they often result in improvementin the auditory hallucinations-associated distress, or controlover the experience, rather than in elimination or reductionin auditory hallucinations.

Low-frequency (1Hz) repetitive transcranial magneticstimulation (rTMS) in the left temporoparietal cortex (TPC)has been used for the treatment of refractory auditoryhallucinations, with some success. This area has been tar-geted because previous neuroimaging research suggests thatactivation of the bilateral superior temporal regions mayhave a role in its genesis [5, 6]. The low frequency (1Hz) ofrTMS produces sustained reductions in cortical activation[5]. It has also been shown to affect functional connectivityof the targeted region (temporo-parietal junction) and gen-eral psychopathology [6, 7]. Gromann et al. [8] concludedthat normalizing the functional connectivity between thetemporoparietal and frontal brain regions may underlie thetherapeutic effect of rTMS on auditory hallucinations inschizophrenia. Despite consistent application of rTMS to thetargeted area, results are variable. A meta-analysis of studies

2 Case Reports in Psychiatry

evaluating the effect of rTMS on the left TPC as treatmentfor auditory hallucinations suggested a significant positiveeffect for rTMS [9] but a more recent meta-analysis [10]has reported a lower effect size for TMS on the left tem-poroparietal cortex for auditory hallucinations. It is unclearwhether there are potential disorder-related and person-related factors that may predict responses to rTMS treatmentfor auditory hallucinations. We report here a case series toexplore these predictors and generate related hypotheses.

The current paper describes the experiences of fourpeople treated with rTMS for auditory hallucinations relatedto schizophrenia, using guided first-person accounts. Theresearch question addressed was as follows:

what is the lived experience of people who weretreated (successfully or unsuccessfully) with rTMS forauditory hallucinations?

2. Method

The sample consisted of four participants who had previouslyreceived treatment with rTMS for auditory hallucinations,that is, 1 Hz TMS applied over the left TPC (localized throughthe 10-20-20 EEG system) by figure-of-eight air-cooled coilusing the Magstim Superrapid II machine for 5 daily sessionsper week (1600 pulses per session) for 2 weeks.The study wasinformed using a phenomenological approach [11], modifiedto involve some predetermined data structuring to accom-modate for expected cognitive impairments of participants,with a focus on lived experiences in relation to the rTMSintervention and its impact on auditory hallucinations.

Participants who were treated with rTMS were inter-viewed within 4 weeks from the last day of treatment withrTMS. Participants recruited for this study met the followinginclusion criteria: (1) age of 18 years or more; (2) a primarydiagnosis of schizophrenia with auditory hallucinations; (3)treatment with rTMS for auditory hallucinations at theauthors’ institution, completed in the past 4 weeks.

The Hallucinations Change Scale (HCS) was not partof the study but was used as a tool for monitoring theoutcome of rTMS treatment in the authors’ institution. TheHCS is a self-rated visual analogue scale personalized foreach individual based on a narrative description of auditoryhallucinations prior to treatment commencement. The base-line is set by definition to 10 and subsequent descriptionsare scored between 0 and 20 with 0 = no hallucinationsand 20 = hallucinations twice the severity of the baselineexperience. Visual analogue scales, although less useful forassessing interindividual differences, are sensitive to changesin each individual [12] and have shown satisfactory reliabilityand sensitivity to change in the area of rTMS treatment ofauditory hallucinations [5, 13]. The ratings on the HCS werecollected as data to determine successful or unsuccessfuloutcome from treatment. “Successful treatment” was definedas a 50% reduction in auditory hallucinations, that is, ascore of 5 or less on the HCS, and “unsuccessful treatment”was defined as no reduction, a reduction less that 50%, ora worsening of auditory hallucinations. Participants wereexcluded if they refused to provide informed consent or have

inability to provide consent. All treating psychiatrists, alongwith the involved mental health care teams, were informedabout the study and were able to refer potential participantsfor involvement in the study.

All four participants provided informed consent to thestudy. This study was approved by the authors’ academiccentre’s Human Research Ethics Board.

Data collection consisted of two parts: (1) individualsemistructured interviews with predetermined prompts; and(2) chart reviews to collect data required for the clinical-demographic form (CDF).

A semistructured interview was conducted with eachparticipant individually. The interview guide addressed thefollowing issues: thoughts and feelings in relation to thehelpful, unhelpful, and other effects of rTMS on auditoryhallucinations; thoughts and feelings in relation to the help-ful, unhelpful, and other effects of rTMS on well-being,functioning and the immediate environment; and thoughtsabout causation of these effects.

All the semi-structured interviews were audio recordedand transcribed verbatim and validated by research staff.Identifying confidential information was removed from allthe transcripts. Participants’ transcripts were used for theanalysis, which was informed by case study research [11, 14].

3. Results

Table 1 lists the HCS scores for each participant before rTMStreatment commencement (Day 1) and after rTMS treatmentcompletion (Day 10). Three out of four participants showeda reduction in the HCS scores to 50% or less indicatingsuccessful treatment.

The qualitative data obtained from individual interviewsis summarized below.

Participant 1. Mr. A is a 37-year-old male who received rTMStreatment for his schizophrenia-related auditory hallucina-tions. He reported a relaxing effect from the repeated tappingand described that the treatment felt like a “mental massage.”He stated that he did not have any long-term benefits fromrTMS but felt better for 30–60 minutes after the treatment.He was not sure as to why the affects wore off so quicklyafter the treatment. In relation to the negative effects of rTMS,Mr. A noted a slight discomfort in swallowing due to theneed to stay still while reclining. He stated that there wasno worsening in his psychiatric symptoms or functioning,and that there were no other negative effects. He stated thatoverall the treatment had neither positive nor negative effectson his auditory hallucinations, well-being, functioning, andenvironment. He did not find it cumbersome that he had totravel to the hospital every day during treatment.

Participant 2. Mr. B is a 54-year-old male who has beendiagnosed with schizophrenia and cooccurring obsessivecompulsive disorder. He experienced distressing auditoryhallucinations which impact his day-to-day functioning. Hereceived rTMS as treatment for his auditory hallucinations.He stated that he experienced a slight discomfort fromthe tapping sound of the machine but became used to it

Case Reports in Psychiatry 3

Table 1: Distribution of the Hallucination Change Score (HCS)obtained from patient’s chart review.

Study participants Day 1 of rTMS Day 10 of rTMSParticipant 1 10 10 (U)Participant 2 10 5 (S)Participant 3 10 2 (S)Participant 4 10 4 (S)U: unsuccessful, S: successful.

after one or two sessions. Mr. B reported that the rTMStreatment helped him cope and better understand his illness.Although the rTMSdid not completely eliminate the auditoryhallucinations, he stated that these hallucinations were moremanageable and his thoughts were clearer as a result ofrTMS. Before rTMS, he felt that his hallucinations were verystrong and at times frightening as well as made it difficultto make decisions due to the distraction. Mr. B felt thatthere were no negative effects of the treatment but reportedan increase in his obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms.He described that after rTMS he began to obsess aboutcleanliness and engaged in washing his hands more. Hewas not sure as to whether this was a direct result of thetreatment itself. He stated that he could concentrate betterandwas less distracted by the auditory hallucinations. He alsoreported feeling happier and more alert to his surroundings.Overall, Mr. B maintained that the treatment was a successfor him and that it took repeated sessions (at least threesessions out of a total of ten planned) and a large amountof hope and positive thinking before any noticeable results(i.e., auditory hallucinations becoming quieter) occurred. Healso stated that the mere knowledge that the TMS treatmentwas available should the auditory hallucinations becomeunmanageable allowed him to “fight the voices” better.

Participant 3. Mr. C is a 32-year-old male who has been diag-nosed with schizophrenia and has been noted to experienceauditory hallucinations by his family and service providers.Mr. C received rTMS at the request of his mother whoreported significant improvement in distractibility followinga previous rTMS treatment for his auditory hallucinations.Mr. C was interviewed with his mother present (at hisrequest). Mr. C expressed no discomfort during the rTMStreatment. He reported that the rTMS helped make histhoughts more clear. Mr. C realized that rTMS treatment wasgiven for auditory hallucinations but claimed that he did notexperience any auditory hallucinations before or after rTMS.Mr. C reported that he did not experience any negative effectsor changes in his well-being, functioning, or environment asa result of rTMS.Mr. C’s mother reported an improvement inhim talking to himself and in his concentration.

Participant 4. Mr. D is a 45-year-old man who has beendiagnosed with schizophrenia and experiences auditoryhallucinations. Mr. D has received rTMS as treatment forpersistent auditory hallucinations. Mr. D expressed that therTMS helped him relax more during the treatment. He statedthat listening to the repeated tapping helped him move hisfocus away from the auditory hallucinations. He felt that

the treatment decreased his auditory hallucinations slightly.Overall, he felt that the rTMS was a good experience due tothe relaxation he felt in his mind and body. Mr. D postulatedthat there may be no predictors and that TMS may justrandomly help some people while not others (stating that alltreatments work for some and not for others). Mr. D alsoexpressed that rTMS had no negative effect on his well-being,functioning, or environment.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

All participants reported here were adult men between theages of 30 years and 55 years. They were all consideredtreatment refractory and were on clozapine. There were nochanges to the treatment in the two months preceding,during, or one month following the low-frequency TMStreatment. Three out of the four participants in the studyself-reported auditory hallucinations. One participant (Par-ticipant 3) denied ever experiencing auditory hallucinationsalthough history fromhis clinical chart documented the pres-ence of auditory hallucinations that considerably disruptedhis social and occupational functioning and which improvedsignificantly during and after the course of TMS. All fourparticipants noted some improvements in their well-beingfollowing treatment: Participants 1 and 4 reported relaxation,Participant 2 reported happiness, improved alertness, andhope, and Participant 3 reported increased clarity of thought.However, only Participants 2 and 4 noted an improvementin the auditory hallucinations (which was corroborated byimproved HCS scores at the end of treatment), and onlyParticipant 2 reported an improvement that was sustainedafter treatment completion. These findings are similar tothose of a systematic review by Poulet et al. [15], whichsuggests that an acute course of low-frequency rTMS signifi-cantly reduces auditory hallucinations but that the effects aretypically not long-lasting (8.5 weeks on average). Qualitativeand quantitative data sometimes conflict, which can promptthe generation of hypotheses and further study. Such adiscrepancy was found in the case of patient number 3, whoreported no hallucinations at baseline in his interview butreported a reduction of his hallucinations post-rTMS on theHCS. This difference in reporting of baseline hallucinationson his part may be explained by the fact that his motherwas present when he was interviewed, which may havecaused him to deny his hallucinations, possibly as part ofdissimilation behavior, which sometimes occurs in familieswith psychopathology [16]; reporting on the HCS is lessdetailed and hence may have facilitated his disclosure ofpresumed baseline hallucinations on it. This explanationraises the possibility that standardized one-item reportingmay provide valid data even when compared to qualitativedata, which could be further explored in other research; it isalready recognized that they can provide reliable data [17].Also, removing family from such interviews as a conditionof participation could be considered, although we upholdparticipant choice in that and other matters.

Overall, none of the participants reported a worseningof their well-being or symptoms. While Participants 1 and 4

4 Case Reports in Psychiatry

reported the tapping to be a positive experience, Participant2 reported that it was a discomfort. Importantly, Participant 2reported a worsening in his obsessive compulsive symptoms.There are several case reports and retrospective studies inrelation to the worsening of obsessive compulsive disordersymptoms due to antipsychotic medications [18], includingclozapine [19]. It is thought that this worseningmay be relatedto the effects of antipsychotics on the dopamine system [20].A recent meta-analysis of rTMS by Slotema et al. [21] notedthat rTMS in the treatment of the negative symptoms ofschizophrenia, using a 10Hz frequency stimulation to theleft dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPF) [22–24] and 1Hzfrequency stimulation to the right DLPF [25], producedseveral side effects including an increase in the symptoms ofcomorbid obsessive compulsive disorder. However, rTMS isbeing studied as an intervention to treat OCDwith promisingresults [26–28].

Participant 2 noted that having repeated sessions, beinghopeful, and keeping a positive view of the treatment helpedwith the treatment process. While a placebo effect cannot becompletely ruled out, we believe that some of the benefitsthat this participant experienced may have been related toan awareness of his illness experience and an acceptanceof some of the manifested symptoms, notably the auditoryhallucinations. He also appeared to be committed to seeingan improvement in these symptoms and to be taking controlof the recovery process using the rTMS as a tool or strategyto cope with the illness. Learning to regulate activity, takingthe role as active agents, and being determined and hoping toovercome the illness and to cope with their symptoms helppeople with schizophrenia regaining a sense of responsibilityover their life [29].

Such use of biomedical treatment as part of masteryof illness has been shown to be effective in other patientpopulations, such as people with diabetes mellitus, who feeland function better when they are in control of their insulininjections.

However, there are limitations to this study. As a caseseries comprising a small sample, its findings cannot berobustly generalized. Also, the challenges in recruitmentwith this population [30] were compounded by the limitedavailability of rTMS as a treatment option at the authors’institution. This may have inadvertently led to a skewedsample of individuals who were favourably biased towardrTMS. Nevertheless, we posit that there are useful findingsin the study worth further exploration, specifically in relationto the role of an individual’s acceptance and ownership ofthe illness process in relation to this biomedical interventionas well as in relation to the effects of rTMS on cooccurringsyndromes such as obsessive compulsive disorder which iscommonly comorbid with schizophrenia.

Disclosure

The writing of this paper was not sponsored nor did anyof authors receive any financial payment for the work.The authors certify that they accept responsibility for thecontent of this paper. All authors helped write this paper,and agree with the decisions about it. All the authors meet

the definition of an author as stated by the InternationalCommittee of Medical Journal Editors, and they have seenand approved the final manuscript. Authors can attest thatthe content of this manuscript and any essential part of it,including tables or figures, is not published elsewhere nor is itbeing considered by another publication. Authors declare noconflict of interests.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded to Dr. Subramainian by Departmentof Psychiatry, Western University.

References

[1] T. H. Nayani and A. S. David, “The auditory hallucination: aphenomenological survey,” Psychological Medicine, vol. 26, no.1, pp. 177–189, 1996.

[2] J. Kane, G. Honigfeld, J. Singer, and H. Meltzer, “Clozapine forthe treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind compar-ison with chlorpromazine,” Archives of General Psychiatry, vol.45, no. 9, pp. 789–796, 1988.

[3] H. Y. Meltzer, “Treatment of the neuroleptic-nonresponsiveschizophrenic patient,” Schizophrenia Bulletin, vol. 18, no. 3, pp.515–542, 1992.

[4] S. S. Shergill, R. M.Murray, and P. K. McGuire, “Auditory hallu-cinations: a review of psychological treatments,” SchizophreniaResearch, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 137–150, 1998.

[5] R. E. Hoffman, K. A. Hawkins, R. Gueorguieva et al., “Tran-scranial magnetic stimulation of left temporoparietal cortexand medication-resistant auditory hallucinations,” Archives ofGeneral Psychiatry, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 49–56, 2003.

[6] A. Vercammen, H. Knegtering, R. Bruggeman et al., “Effects ofbilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on treat-ment resistant auditory-verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia:a randomized controlled trial,” Schizophrenia Research, vol. 114,no. 1–3, pp. 172–179, 2009.

[7] A. Vercammen,H. Knegtering, E. J. Liemburg, J. A. D. Boer, andA. Aleman, “Functional connectivity of the temporo-parietalregion in schizophrenia: effects of rTMS treatment of auditoryhallucinations,” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 44, no. 11,pp. 725–731, 2010.

[8] P. M. Gromann, D. K. Tracy, V. Giampietro, M. J. Brammer,L. Krabbendam, and S. S. Shergill, “Examining frontotemporalconnectivity and rTMS in healthy controls: implications forauditory hallucinations in schizophrenia,” Neuropsych, vol. 26,no. 1, pp. 127–132, 2012.

[9] C. Freitas, F. Fregni, and A. Pascual-Leone, “Meta-analysisof the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation(rTMS) on negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia,”Schizophrenia Research, vol. 108, no. 1–3, pp. 11–24, 2009.

[10] C. W. Slotema, A. Aleman, Z. J. Daskalakis, and I. E. Sommer,“Meta-analysis of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulationin the treatment of auditory verbal hallucinations: update andeffects after onemonth,” Schizophrenia Research, no. 1–3, pp. 40–45, 2012.

[11] J. W. Creswell, Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choos-ing among Five Approaches, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks,Calif, USA, 2007.

Case Reports in Psychiatry 5

[12] R. C. Aitken, “Measurement of feelings using visual analoguescales,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 62, no.10, pp. 989–993, 1969.

[13] C. Tranulis, A. A. Sepehry, A. Galinowski, and E. Stip, “Shouldwe treat auditory hallucinations with repetitive transcranialmagnetic stimulation? A metaanalysis,” Canadian Journal ofPsychiatry, vol. 53, no. 9, pp. 577–586, 2008.

[14] R. K. Yin, Case Study Research: design and Methods, SagePublications, Thousand Oaks, Calif, USA, 2009.

[15] E. Poulet, F. Haesebaert, M. Saoud, M. F. Suaud-Chagny, andJ. Brunelin, “Treatment of shizophrenic patients and rTMS,”Psychiatria Danubina, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. S143–S146, 2010.

[16] J. Stokes, D. Pogge, B. Wecksell, and M. Zaccario, “Parent-childdiscrepancies in report of psychopathology: the contributionsof response bias and parenting stress,” Journal of PersonalityAssessment, vol. 93, no. 5, pp. 527–536, 2011.

[17] B. E. H. Schorre and I. H. Vandvik, “Global assessment ofpsychosocial functioning in child and adolescent psychiatry: areview of three unidimensional scales (CGAS, GAF, GAPD),”EuropeanChild andAdolescent Psychiatry, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 273–286, 2004.

[18] R. J. Keuneman, V. Pokos, R. Weerasundera, and D. J. Castle,“Antipsychotic treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: aliterature review,” Australian and New Zealand Journal ofPsychiatry, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 336–343, 2005.

[19] Y. Levkovitch, Y. Kronnenberg, and B. Gaoni, “Can clozapinetrigger OCD?” Journal of the American Academy of Child andAdolescent Psychiatry, vol. 34, no. 3, p. 263, 1995.

[20] W. K. Goodman, C. J. McDougle, L. H. Price, M. A. Riddle, D.L. Pauls, and J. F. Leckman, “Beyond the serotonin hypothesis:a role for dopamine in some forms of obsessive compulsivedisorder?” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, vol. 51, no. 8, pp. 36–43,1990.

[21] C. W. Slotema, J. D. Blom, H. W. Hoek, and I. E. C. Som-mer, “Should we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatmentmethods to include repetitive transcranialmagnetic stimulation(rTMS)? A meta-analysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatricdisorders,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, vol. 71, no. 7, pp. 873–884, 2010.

[22] P. B. Fitzgerald, S. Herring, K. Hoy et al., “A study of theeffectiveness of bilateral transcranial magnetic stimulation inthe treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia,”BrainStimulation, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 27–32, 2008.

[23] A. Mogg, R. Purvis, S. Eranti et al., “Repetitive transcranialmagnetic stimulation for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: arandomized controlled pilot study,” Schizophrenia Research, vol.93, no. 1–3, pp. 221–228, 2007.

[24] R. Prikryl, T. Kasparek, S. Skotakova, L. Ustohal, H.Kucerova, and E. Ceskova, “Treatment of negative symptomsof schizophrenia using repetitive transcranial magneticstimulation in a double-blind, randomized controlled study,”Schizophrenia Research, vol. 95, no. 1–3, pp. 151–157, 2007.

[25] E. Klein, Y. Kolsky, M. Puyerovsky, D. Koren, A. Chistyakov,and M. Feinsod, “Right prefrontal slow repetitive transcranialmagnetic stimulation in schizophrenia: a double-blind sham-controlled pilot study,” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 46, no. 10, pp.1451–1454, 1999.

[26] P. Alonso, J. Pujol, N. Cardoner et al., “Right prefrontal repeti-tive transcranial magnetic stimulation in obsessive-compulsivedisorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study,” AmericanJournal of Psychiatry, vol. 158, no. 7, pp. 1143–1145, 2001.

[27] J. Prasko, B. Paskova, R. Zalesky et al., “The effect of repetitivetranscranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on symptoms inobsessive compulsive disorder. A randomized, double blind,sham controlled study,” Neuroendocrinology Letters, vol. 27, no.3, pp. 327–332, 2006.

[28] P. S. Sachdev, C. K. Loo, P. B. Mitchell, T. F. McFarquhar, andG. S. Malhi, “Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation forthe treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: a double-blindcontrolled investigation,” Psychological Medicine, vol. 37, no. 11,pp. 1645–1649, 2007.

[29] D. Roe, M. Chopra, and A. Rudnick, “Persons with psychosisas active agents interacting with their disorder,” PsychiatricRehabilitation Journal, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 122–128, 2004.

[30] J. Hamann, B.Neuner, J. Kasper et al., “Participation preferencesof patients with acute and chronic conditions,” Health Expecta-tions, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 358–363, 2007.

Submit your manuscripts athttp://www.hindawi.com

Stem CellsInternational

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

MEDIATORSINFLAMMATION

of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Behavioural Neurology

EndocrinologyInternational Journal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Disease Markers

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

BioMed Research International

OncologyJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

PPAR Research

The Scientific World JournalHindawi Publishing Corporation http://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Immunology ResearchHindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Journal of

ObesityJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine

OphthalmologyJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Diabetes ResearchJournal of

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Research and TreatmentAIDS

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Gastroenterology Research and Practice

Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com Volume 2014

Parkinson’s Disease

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Volume 2014Hindawi Publishing Corporationhttp://www.hindawi.com

![Case Report Acupuncture in the Treatment of a Female ...downloads.hindawi.com/journals/crips/2016/6745618.pdf · from Chronic Schizophrenia and Sleep Disorders ... (PANSS) [] lled](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5ad5ea9c7f8b9a571e8e1e8d/case-report-acupuncture-in-the-treatment-of-a-female-chronic-schizophrenia-and.jpg)