CARY HISTORIC LANDMARK DESIGNATION APPLICATION

Transcript of CARY HISTORIC LANDMARK DESIGNATION APPLICATION

Page 1 of 17

CARY HISTORIC LANDMARK DESIGNATION APPLICATION

Preparing Your Application: Please type if possible. Use paper no larger than 11” x 17” for the required supporting information. Staff is available to advise on the preparation of applications.

Filing Your Application: When completed, the attached application will initiate consideration of a property for designation as a local historic landmark. The application will enable the Town of Cary Historic Preservation Commission (CHPC) to determine whether the property qualifies for designation. The CHPC will make its recommendation to the Cary Town Council. Mail the application to Town of Cary Planning Department, PO Box 8005, Cary, NC, 27512. Submitted materials become the property of the Town of Cary and will not be returned. Incomplete applications may be returned to the applicant for revision. Staff will contact applicants after receiving an application to discuss the next steps of the designation process. Please contact staff with any questions at (919) 469-4084, or at [email protected].

1. Name of Property (if historic name is unknown, give current name or street address)

Historic Name: _____Cary High School __________________________________________

Current Name: _____Cary Arts Center____________________________________________

2 . Location

Please include the full street address of the property, including its local planning jurisdiction. Wake County Property Identification (PIN) and Real Estate Identification (REID) Numbers can be found at the Wake County property information website at http://services.wakegov.com/realestate/ or by contacting the Town of Cary Planning Department.

Street Address: __________101 Dry Avenue, Cary, NC 27511________

PIN Number: ___0763498867______ Real Estate ID Number: ____0308694________

Deed Book/PG Number: Book _10352___ Page: _705__ Appraised Value:

__$6,120,953.00_____

3. Legal Owner of Property (If more than one, list primary contact)

Name: _____Town of Cary ________________________________

Address: _____316 N. Academy Street______________________

City: _________Cary___________ State: ___NC_____ Zip: ____27513_________________

Phone: _____919-469-4084______________________________________

Email: [email protected]___________________________________________

Ownership: Private Public: Local State Federal

4. Applicant/Contact Person (If other than the owner)

Name: _____Cynthia de Miranda, MdM Historical Consultants for Town of Cary ______

Address: ____PO Box 1399_______________________________________________

City: ______Durham_____________________ State: ____NC_______ Zip: _____27702________

Phone: ___919-906-3136_____________Email: [email protected]____

Page 2 of 17 5. General Data/Site Information

Date of Construction and major alterations and additions: 1939, ca. 1960, 2010-2011 Number, type, and date of construction of outbuildings: n/a Approximate lot size or acreage: 1.77 acres Architect, builder, carpenter, and/or mason: William Henley Dietrick, architect; W. W. Chafin, PWA Engineer Original Use: school Present Use: arts center

7. Classification

A. Category:

Building – created principally to shelter any form of human activity (i.e. house, barn/stable, hotel, church, school, theater, etc.) Structure - constructed usually for purposes other than creating human shelter (i.e. tunnel, bridge, highway, silo, etc.) Object - constructions that are primarily artistic in nature. Although movable by nature or design, an object is typically associated with a specific setting or environment (i.e. monument, fountain, etc.) Site - the location of a historic event, a prehistoric or historic occupation or activity, or a building or structure, whether standing, ruined, or vanished, where the location itself possesses historic, cultural, or archeological value, regardless of the value of any existing structure (i.e. battlefields, cemeteries, designed landscapes, etc.)

B. Number of Contributing and non-contributing resources on the property:

A contributing building, site, structure, or object adds to the historic associations, historic architectural qualities, or archeological values for which a property is significant because it was present during the period of significance, relates to the documented significance of the property, and possesses historic integrity or is capable of yielding important information about the period.

No. of Contributing No. of Noncontributing Buildings 1 0 Sites 0 0 Structures 1 0 Objects 0 0

Page 3 of 17

C. Previous field documentation -- when and by whom. (Contact staff to determine whether the property has been included in a previous survey): National Register Nomination, 2001, by Kelly Lally Malloy D. National Register of Historic Places status:

Status Date Entered Listed in Cary HD, 2001 Nominated Nominated and Determined Eligible

Nominated and Determined Not Eligible Removed

Significant changes in integrity since listing should be noted in section 11.F. 8. Reason for Request:

To recognize the significance of the building in Cary, and to ensure preservation of architectural fabric.

9. Is the property income producing? Yes No

10. Are any interior spaces being included for designation? Yes No Signatures

I have read the general information on landmark designation provided by the Cary Historic Preservation Commission and affirm that I support landmark designation of the property defined herein.

OFFICE USE ONLY: Fee: _____________ Amt Paid: _____________ Check #: __________

Rec’d by: ____________________________________________ Rec’d Date: _______________ Completion Date: _______________________________________

Owner: Date: ___________

Owner:

Date:

___________

Owner:

Date:

___________

Owner:

Date:

___________

Page 4 of 17 11. Supporting Documentation 11A. Supporting Documentation: Photographs

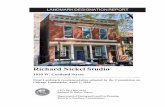

Cary High School, façade and overall view

Cary High School, front entry

Page 9 of 17

11C. Maps

Location Map: Cary High School, 101 Dry Avenue, Cary NC

Tax Map: Cary High School, 101 Dry Avenue, Cary NC

Page 10 of 17

11D. Physical Description Narrative of All Resources on the Site Cary High School is an imposing, two-story tripartite brick building rendered in Colonial Revival style. It stands at the south terminus of Academy Street in the historic core of Cary, looking north toward the commercial district and the train tracks. Founded in 1870, Cary is a railroad town in southwestern Wake County that has grown to be the county’s second-largest municipality. The school is a Contributing Building in and a focal point of the Cary Historic District (NR 2001). The district is mainly residential, where dozens of houses dating from the 1890s to about 1945 line streets arranged in a grid around the school. Academy Street is the district’s main thoroughfare. The common-bond, red-brick building stands two stories on a raised basement. The slightly taller central block has a side-gabled roof finished with stepped parapet walls. Matching gable-roofed wings extend to either side and merge into hip-roofed transverse wings that project slightly at the façade while extending mainly to the rear. The building has a shallow U-shaped floor plan. A single-story rear block set into the hollow of U historically housed an auditorium and has been extended at its rear with a two-story flytower. Columns at the façade’s pedimented two-story portico, along with window sash throughout the building, have been replaced. The work replicates the building's original appearance, reversing changes made in the later decades of the twentieth century. While the new window sashes match the original light configurations match originals, they are not wood. The building was repurposed from a school into an arts center in 2011. The building stands on a brick plaza that dates to the recent rehabilitation. A broad set of brick steps rises to the front doors, with ramps lined with brick walls zig-zagging at either side of the steps. Metal railings are used at both the steps and the ramps. Small, flowering trees in large concrete planters soften the paved space, as do small areas of lawn flanking the plaza. Brick gateposts dating to an earlier 1913 school building (not extant) survive near the street, helping define the space between the roadway and the building and recalling a campus feeling. The current building’s main block is seven bays wide and symmetrical with the more elaborately decorated three central bays sheltered beneath the Ionic-columned portico. The columns have egg-and-dart molding between volutes at their caps, but fluting of the column shaft only extends along its uppermost part. Below a band of torus molding, the length of the column is not fluted and finishes at a base formed by doubled torus molding. The pilasters have a matching design. Set into the smooth, stuccoed façade wall below the portico are three doors at the first floor paired with three windows above. The center openings are unified by an elaborate molding that include pilasters and entablature at the door and hooded molding at the window. A fanlight transom highlights the paneled, double-leaf door; the window above has a segmental arch and the new sash replicates the twelve-over-twelve pattern of the original. The partially-glazed flanking doors replaced original twelve-over-twelve windows. A new, nine-light transom is set into the uppermost part of those original window openings. The windows above the new flanking doors are segmental arched with twelve-over-twelve sash. A recessed panel fills the vertical space between door-and-window pairs. The two bays on either side of the portico in the main block have paired sets of twelve-over-twelve windows with cast stone sills and jack arches with exaggerated keystones. The cornice across the main block and at the portico’s pediment are both modillioned, and an oval window adorns the center of the pediment. The two connecting side wings are each five bays wide, featuring evenly spaced twelve-over-twelve windows with brick jack arches and cast stone sills. A pair of segmental arched roof dormers with board-and-batten siding and louvered openings vent the attic area. The front-facing end of the outermost wings are blind walls finished with brick corner quoins. Across the wings, the boxed cornice is unadorned. Side elevations each show two bands of four twelve-over-twelve windows with brick jack arches and cast stone sills at each story, including at the basement level. Light wells line the building to aid illumination in the basement. The rear-most bay in each original side elevation holds stairwells and a door at the ground level; the doors and the stairwell windows are capped by fanlight transoms under round-arched molding rendered in brick. Windows have cast-stone sills. A single, centered segmental-arch dormer as at the façade vents the side wing roofs at each wing.

Page 11 of 17

The single-story auditorium housed in the rear wing was upgraded in the 2011 remodel with a two-story flytower. First-floor walls throughout the original section and the addition are buttressed, with twelve-over-twelve windows occurring singly at the audience area section directly behind the original building. Egress is available through doors at the rearmost bay before the flytower. Side walls of the flytower are blind, at the north and south walls, yellow brick “infill” occurs where windows would have been placed if the interior space needed natural illumination. Covering the yellow brick is an art installation consisting of projecting, triangular metal frames that hold colored transparent triangular panels. There is also a two-story, flat-roofed, brick-clad addition along the west side of the auditorium block and the flytower. The addition generally fills in the nook created by the side wing's extension past the rear wall of the main block of the building. A single-story height brick wall conceals HVAC equipment, but reads as a single-story block adjacent to the taller addition. The addition and brick walls do not extend past the west wall of the side wing of the original building and are completely hidden from view at Dry Avenue. When the building was repurposed as an arts center, a great number of interior changes were made. Very few original details and materials survive at the interior. Most prominent is the Georgian Revival-style molding at two cased openings off the main front reception space leading into the two lateral halls. Here, robust cornice molding rests on a cushioned frieze topping a trabeated architrave. The molding was moved from the main front hall when original walls were demolished and was reused on new walls. Toward the back of the rear wings, the original brick wall that separates the classroom halls from the stairwells remains. The original doors are missing, but the architraves and fanlight transoms remain. A few other rectangular transoms remain throughout the building, marking the location of original walls. 11E. Historical Background Narrative The 1939 Cary High School is the third secondary school building erected on this spot. The first followed close on the heels of the town's founding, when lumberman Allison Francis (Frank) and his wife Catherine Raboteau (Kate) Page purchased land along the tracks of the brand-new North Carolina Railroad late in 1854. They lived in a house that came with the land, and Frank Page immediately began building up the place. He established a lumber mill, a general store, and a post office, naming the latter "Cary" after a national leader in the temperance movement. In 1868, the Chatham Railroad also built a line through the area, prompting Page to lay out a village and begin selling parcels. In 1871, the state legislature incorporated the Town of Cary. The new municipality was a single square mile in area, centered on the Chatham Railroad's warehouse.1 Page reserved one of the parcels in his 1868 town plat for a school. By 1870, a two-story frame building had been erected using lumber harvested from the site and cut at Page’s mill. It housed the four rooms of Cary Academy, a private boarding school that accepted white students, both male and female. Page was one of the founders and early owners. The first principal was University of North Carolina graduate Abram Haywood Merritt; Reverend Jesse Page and Reverend Solomon Pool followed. Out-of-town students boarded in private homes, and the school quickly became a defining institution in western Wake County.2 The private academy continued to develop and grow into the early twentieth century. Page sold his ownership in 1886 to Loulie and Sarah Jones, two daughters of fellow shareholder Rufus Jones and

1 Thomas M. Byrd, Around and About Cary, 2nd ed. (Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Bros., 1994), 17, 24, 55; Cary's 100th Anniversary (Raleigh: The Graphic Press, 1971), 2.

2 Byrd, 55-56; Kelly Lally, The Historic Architecture of Wake County, North Carolina (Raleigh: Wake County Government, 1994), 325; Elizabeth Reid Murray and Todd Johnson, Wake: Capital County of North Carolina, Volume 2, Reconstruction to 1920 (Raleigh: Capital County Publishing Company, 1983), 563-564.

Page 12 of 17

moved to Moore County. The Jones sisters operated the school as Cary Female Institute for a few years, but by 1896 it was renamed Cary High School and under the direction of Principal E. L. Middleton. Cary High School was open to both boys and girls. Within a few years, five teachers provided instruction to both secondary and primary grades, dividing the academic year into two five-month terms. The school reportedly enrolled 250 boarding and day students. The original frame building was still in use, expanded with classroom wings to the sides and, in 1900, a boy's dormitory at the back. A girl's dormitory stood on Academy Street, but some students were still housed in private homes as a cost of about $9 monthly. Principal Middleton was enthusiastic about promoting the school and recruiting students, and Cary High School was well known throughout the state by the turn of the century.3 Cary High School became public in 1907, just after the legislature established a statewide system of high schools for white students. Population statistics mandated that Wake County get four high schools. The county school board promptly purchased Cary High School and established schools at Holly Springs and Bay Leaf and another between Wakefield and Zebulon. Because the county used some state funds to purchase the school—and acted within days of the new law’s passage, Cary High School is considered North Carolina’s first state-funded high school.4 A year later, new principal Marcus Baxter Dry embarked on a physical transformation of the school. In 1913, a two-story-on-raised-basement brick building replaced the original frame Cary Academy building at a cost of $30,000, financed by a bond issue. The school could reportedly accommodate two hundred students, including primary students on the first floor. An auditorium could seat eight hundred—an impressive space, given that the population of the town was about four hundred. Over the next several years, two dormitories, a gymnasium, and other buildings followed, creating a small campus of brick buildings. The school offered both vocational and academic instruction, and a demonstration farm occupied some land on Walnut Street. Graduates in the 1920s could get a diploma in academics, agriculture, home economics, or teaching. The need for students to board eventually dried up as more schools were built and transportation improved. The dormitories were converted to teacher housing in 1933.5 Although the 1913 building was at one point considered “the finest rural high school building in the state,” by the mid-1930s Wake County was seeking funds for a new building. State and county officials viewed the school as a “beacon of hope and inspiration to other communities of the state,” as Governor Clyde R. Hoey would later declare. In 1935, the Chamber of Commerce began working with government agencies in Raleigh to secure PWA funding for projects. Before the end of the decade, over $5 million in projects were underway in Raleigh and Wake County. The newspaper called it the biggest public building program Raleigh and Wake County had ever seen. The PWA covered forty-five percent of the cost of the projects, which ranged from fireproofing the nineteenth-century dome of the Greek Revival capitol building to expanding Raleigh’s water works system to adding classroom buildings and dormitories at North Carolina State College. It also included $250,000 for six Wake County schools. Of that total, $132,000 was allocated to erect a new building for Cary High School, the largest in the county.6 The new building was dedicated in March 1940 with a ceremony covered prominently in the

3 Murray and Johnson, 564-565; Byrd, 55-57, 61-63; Evelyn Holland, "The Village Through Memory" and "A History of Cary High School" both in Cary's 100th Anniversary, 8, 13.

4 Murray and Johnson, 284-285; Byrd, 62.

5 Holland, "Cary High School," 14; News and Observer, September 28, 1913; Murray and Johnson, 285; Byrd, 62-64, 84; Cary population in 1910 and 1920 from Population.com, viewed April 15, 2017.

6 News and Observer, March 5, 1940; August 17, 1935; and October 5, 1939.

Page 13 of 17

Raleigh News and Observer and attended by many state and local dignitaries. The article boasts of the modernity of the new building as it celebrates the institution’s history and preeminence. "The new building” the paper chronicled “is completely equipped and a fire-resistant construction that has latest type individual lockers for students, motion picture projection facilities, and intercommunicating loud speakers. It has vocational departments and cafeteria in the basement." Project architect William Henley Dietrick attended, as well as PWA project engineer W. W. Chafin. State officials included Governor Hoey; Clyde A. W.Erwin and J. Y. Joyner, current and former State Superintendents of Public Instruction; W. F. Credle, Director of Schoolhouse Planning in the State Department of Public Instruction; and Lloyd Griffin, Executive Secretary of State School Commission. Also attending were Wake County commissioners, members of the Cary School Committee, chairmen of other Wake County district school committees, and principals of other Wake County high schools.7 The school building continued in use for all grades for white students in Cary until the 1960 opening of a new senior high school on Walnut Street. The 1939 Cary High School building was then converted to house the elementary and junior high grades, and eventually just the elementary school. By 2003, both the junior high and elementary grades had new buildings elsewhere, and the 1939 Cary High School awaited a new use. The Town of Cary acquired the property and converted it for its current use as an arts and cultural center, which opened in 2011. The new use required installation of the flytower, but also presented the opportunity to restore the portico and install new replacement windows that restored the original light configuration. The work won an Anthemion Award from Capital Area Preservation in 2011 for the rehabilitation and reuse project. 11F. Significance Statement Cary High School is uniquely significant in the town’s history in the areas of education, politics and government, and architecture. As the third structure to house Cary High School at the original site of the precursor institution, Cary Academy, the building reflects the importance that white leaders in this small railroad town put on supporting a renowned school for students of their race during segregation. The 1939 building was a substantial PWA project, connecting it to a government program of profound consequence in American history. Finally, the building is an excellent example of Colonial Revival architecture, designed by prominent Raleigh architect William Henley Dietrick in the first half of his career. While the building was renovated and expanded in 2010-2011, it retains the essential aspects of historic and architectural integrity required for landmark designation. The edifice is in its original location, at the terminus of Academy Street two blocks south of the railroad tracks and the historic commercial core of the town. It maintains its monumental presence relative to its surroundings, which consist mainly of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century houses in the Cary Historic District and therefore retains integrity of setting. While window sash and columns have been replaced and the interior has been heavily remodeled, the building's overall massing, fenestration pattern, and red-brick exterior are all intact, preserving its integrity of design. Integrity of materials and workmanship are evident in the brick walls and architectural details at window surrounds. All these aspects combined contribute to the building's integrity of feeling and association as an important, even outsized, structure in a historically small town. Public Schools in the Town of Cary “Sometimes a town builds up a school" noted the Raleigh News and Observer in 1913, "and sometimes a school builds up a town. Cary is best known through its rural high school, number one, the first of the present 218.” The rural high school that built up the town was a private academy, open only to whites. However, the school brought eminence to the rural railroad town as an educational center in the segregated period of the state's history.8

7 News and Observer, March 5, 1940.

8 Raleigh News and Observer, August 15, 1913.

Page 14 of 17

Cary Township set up its public school system soon after its own establishment in 1872. The state's public school law of 1869 directed county commissioners and township committees to manage distributed state funds for schools. Townships were divided into districts based on population, and facilities were to be segregated. Establishing schools was apparently difficult: many township school districts within Wake County lacked facilities as late as 1884.9 The rail line divided Cary Township into two districts, which together operated four public schools by 1877. District 1 schools, north of the tracks, were located around the present-day intersection of Reedy Creek Road and North Harrison Avenue. South of the tracks, a two-room frame building just southeast of Cary High School was built for white students. Black students attended school in a loaned log cabin on Alfred “Buck” Jones's land near the current-day intersection of Walnut Street and Tanglewood Drive. These modest buildings stood in contrast to the two-story, four-room frame building for then-private Cary Academy. School terms at the public schools were short, starting in November and running through late winter. Cary was a farming community, and the schedule allowed students to remain available for agricultural work from the spring through the fall harvest. After Buck Jones died in 1895 and the town lost access to the property, the white public school students were allowed to attend the Cary High School tuition-free, and the small frame building they had been using became Cary Colored School.10 Availability of free education improved for whites with the 1907 passage of the Rural High School Act, which promoted the establishment of high schools by the county boards. Once Cary High School was converted to a public school in 1907, white students had a solid, free option to continue their education past the primary grades. Black students did not. Eventually, they attended Berry O’Kelly School, founded in 1894 and significantly expanded in 1915. The school stood six miles away in Method, a black community between Cary and Raleigh, so transportation was an issue until there was a bus.11 Three new schools were built in Cary Township in the early twentieth century. Evans Grove School, built for black students, had just a single classroom. The two new schools for white students were Reedy Creek and Cary Public School, with buildings of two and four rooms, respectively. Cary Colored School remained in use until it burned in 1936. After the fire, the Town of Cary expected primary students to attend Berry O'Kelly, but the black community was determined to have a local elementary school. After a couple of years, a one-room brick school building was erected on Boyd Street for black elementary students. It was named East Cary Elementary School, later called Kingswood Elementary.12 The middle decades of the twentieth century brought further development and significant changes. In 1945, all white students within the Town of Cary were housed in Cary High School from grades 1 through 12. Cary Colored School only offered grades 1 through 8 for black students from the Town of Cary, with students continuing on to Berry O’Kelly School for high school. This system continued until 1960, when a new Cary Senior High School opened on a 39-acre campus on Walnut Street. The 1939 Cary High School building housed elementary and junior high school grades. Cary Colored School remained unchanged. In 1963, five black students integrated Cary Senior High School at the new campus, beginning the process of school desegregation for all of Wake County’s schools (Raleigh city schools were a separate system at the time).13

9 Murray & Johnson, 259-261; Byrd, 57-58.

10 Lally, 325; Byrd, 57-58; Peggy Van Scoyoc, Just a Horse-Stopping Place (Cary: Passing Time Press, 2006), 102-103.

11 Van Scoyoc, 101.

12 Byrd, 61; Van Scoyoc, 103-108; Cary News in Raleigh News and Observer, February 12, 2014.

13 Byrd, 120-121.

Page 15 of 17

The decade of desegregation in Cary’s schools coincided with the beginning of the dramatic growth that transformed the historically agricultural small town into a sprawling, diverse, and significantly larger community. Growth occurred both in population and land area. The development of the Research Triangle Park contributed heavily to the rapid population growth, as well as to the change in demographics, bringing in large numbers of Northern transplants working for companies like IBM, Burroughs Wellcome, and other companies with a global reach. By the early twenty-first century, Cary’s town limits encompassed fifty-five square miles and its population had doubled every decade since 1960. The growth resulted in more public schools throughout Cary and the rest of Wake County as well as significant updates to or replacement of facilities.14 Politics/Government The Public Works Administration (PWA) had been engaged in school repair and building since the early 1930s in Wake County. The PWA provided labor funding for basic maintenance like painting or gutter and minor roof repair at many Wake County schools, though predominantly at the schools for white students. Cary High School requested and received $75 in PWA funding to pay painters 12-1/2 cents an hour to paint an estimated nine thousand square feet of building exteriors at its early twentieth century campus in May 1933.15 Much more substantial funding was soon available. In July 1935, Clyde Erwin, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction and W. F. Credle, the Director of Schoolhouse Planning, issued a letter urging public school superintendents to apply for public works funding for new school buildings. Within weeks, the Chamber of Commerce began working with state agencies to secure funds from the WPA. Raleigh and Wake County were very successful in securing approval for a large portfolio of projects, and Cary High School benefitted more than any other rural high school in the county. The school's brick campus of six buildings was deemed in need of replacing with a state-of-the art, fireproof building and was generously funded.16 Architecture The Colonial Revival style was popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; in the later part of the period, the style was characterized by references to the Georgian Revival and Federal styles. The symmetrical massing and fenestration, monumental portico, and attention to the entry seen in the Cary High School building are all key elements of the style. The corner quoins, modillioned cornice, and pedimented portico also allude to classical antecedents. The PWA completed 805 school-related projects across North Carolina before 1937, according to an agency newsletter. Of these hundreds of projects, forty-five were "outright new buildings." The newsletter highlighted the Rustic Revival-style architecture favored in the mountains, but the PWA also built in the Colonial Revival style in the eastern parts of the state.17 One example is the Perry School in Franklin County. The frame, 1941 building was based on a

14 Interview with Gwendolyn Matthews by Peggy Van Scoyoc, December 9, 1999, K-0654, in the Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Peggy Van Scoyoc, Desegregating Cary, 4.

15 Department of Public Instruction, Division of Schoolhouse Planning, Miscellaneous Items, Box 2, Folder: Wake County, State Archives, Division of Archives and History, Raleigh.

16 Department of Public Instruction, Division of Schoolhouse Planning, General Correspondence, July 1934-Junes 1936, Folder: Miscellaneous-Forms, State Archives, Division of Archives and History, Raleigh; News and Observer, August 17, 1935.

17 Rural Project Issue, North Carolina WPA: Its Story, Vol II, No. 8, 1937.

Page 16 of 17

Rosenwald plan, the six-room Nashville plan. Standing at a single story, the building is much more modest than the Cary High School, but the buildings share a basic massing, with transverse end wings and a portico at the center of a gabled center wing.18 The 1939 Cary High School was designed by William Henley Dietrick, a classically trained architect who had studied at Columbia University. He arrived in Raleigh in 1924. Dietrick is known for a number of early Modern buildings in Raleigh dating to the late 1930s and later, but in the 1920s and through most of the 1930s he worked in historically based eclectic styles popular at the time. Dietrick's design for Cary High School was likely guided by style manuals from the PWA and/or from Division of Schoolhouse Planning at the state Department of Public Instruction. A letter from Dietrick to PWA Regional Director H. T. Cole references "the Manual" as well as the Building Code of the National Board of Fire Underwriters. Dietrick took care to add "fire towers" at the ends of the building, stairwells separated by thick brick firewalls from the classroom and other areas of the building. No mention is made of requirements for architectural style or materials. However, in 1940, the state's schoolhouse planning director W.F. Credle remarked in a letter that "in old communities a simple form of colonial architecture can and should be used. It is possible to use a colonial design, and yet obtain a maximum amount of instructional space." The Cary High School building did just that, fitting a modern facility into the colonial-style edifice.19 11G. Landmark Boundary The boundary for the landmark designation coincides with the tax parcel line for the property at 101 Dry Avenue, also known by PIN 0763498867, which is the original site of the 1939 Cary High School building as well as the original site of the precursor institution, the nineteenth-century Cary Academy. The Cary High School building is the only building on this parcel. Immediately west of the building is a parking lot, accessed from Faculty Avenue. The brick plaza fills the area in front of the building, and landscaped open space occupies roughly the northeast third of the parcel. The brick gateposts from the 1913 building survive but appear to be outside the tax parcel boundary. Historically, the Cary High School Campus occupied a larger parcel that extended to the south. The parcel has been subdivided, however, and the south portion of the original high school campus now is home to Cary Elementary School. 11H. Bibliography Published Sources Byrd, Thomas M. Around and About Cary, 2nd ed. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Bros., 1994. Cary's 100th Anniversary. Raleigh: The Graphic Press, 1971. Holland, Evelyn. "The Village Through Memory" and "A History of Cary High School." Both in Cary's 100th Anniversary. Raleigh: The Graphic Press, 1971. Lally, Kelly. The Historic Architecture of Wake County, North Carolina. Raleigh: Wake County Government, 1994. Murray, Elizabeth Reid, and Todd Johnson. Wake: Capital County of North Carolina. Volume 2, Reconstruction to 1920. Raleigh: Capital County Publishing Company, 1983. Van Scoyoc, Peggy. Desegregating Cary, North Carolina. Cary: Passing Time Press, 2009. ---. Just a Horse Stopping Place. Cary: Passing Time Press, 2006. "Rural Project Issue," North Carolina WPA: Its Story, Vol II, No. 8, 1937.

18 Jennifer Martin, "Perry School National Register of Historic Places Nomination," Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh, available online at http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/FK0549.pdf.

19 William Henley Dietrick to H. T. Cole, September 8, 1938, Department of Public Instruction, Division of Schoolhouse Planning, General Correspondence, July 1938-June 1939, State Archives, Division of Archives and History, Raleigh; Credle quoted in Martin, 23.

Page 17 of 17

Raleigh News & Observer. Various dates. Unpublished Sources Black, David. "Early Modern Architecture in Raleigh Associated with the Faculty of the NCSU School of Design, Raleigh, North Carolina, Wake County." MPDF, Historic Preservation Office, viewable online at http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/wa7245.pdf. Department of Public Instruction, Division of Schoolhouse Planning Records. State Archives, Division of Archives and History, Raleigh. Little, Ruth. "The Architecture of William Henley Deitrick & Associates from 1926-1960." MPDF on file at the Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh, NC. Martin, Jennifer. "Perry School National Register Nomination." Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh. Available online at http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/FK0549.pdf. Matthews, Gwendolyn, interviewed by Peggy Van Scoyoc. December 9, 1999, K-0654. Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.