'CARTE BLANCHE' · Carte Blanche, but this need not detain us, since the entire passage is taken,...

Transcript of 'CARTE BLANCHE' · Carte Blanche, but this need not detain us, since the entire passage is taken,...

'CARTE BLANCHE'

T. C. SKEAT

ALTHOUGH in the earlier part ofthe last century it was included in the permanentexhibition of manuscripts, the Department of Manuscripts has in more recent timesbeen rather reluctant to publicize what is (or at any rate may be) one of the mostdramatic items in the whole of its collections, the 'Carte Blanche' reputed to havebeen given by Charles, Prince of Wales, the future Charles II, 'to save his father'shead' on the eve of his execution on 30 January 1648/9 (Harley MS. 6988,fol. 222).^

At the beginning of Harley MS. 6988 there is inserted a type-written note concerningthe Carte Blanche drawn up by J. P. Gilson, Keeper of Manuscripts from 1911 to 1929,for use when the document was exhibited to the Anglo-American Conference ofHistorians on 13 July 1921. The note reads as follows:

Carte Blanche of Charles II as Prince on f. 222. It seems doubtful whether any authority forthe statement that this was designed 'to save his Father's Head' exists apart from the (i8thcent.) endorsement. The story is however accepted by W. Harris, Life of Charles II (1766), i,p. 40; Sir H. Ellis, Orig. Letters, ist Ser. iii (1825), frontispiece; S. R. Gardiner, Hist, oftheGreat Civil War (1893), iv, p. 316, and others.^

Curiously, Gilson has not included in the above note a reference of which he wascertainly aware to an earlier mention of the Carte Blanche. He did, however, note thisin the copy of the Harley Catalogue which stands in the Keeper's Room, in which hehas written in the margin:

according to the story in Echard's History i (1718) p. 638, but quaere

1. If the story be true?2. If true, whether this is the paper?

Charles certainly used blanks for other purposes.

Laurence Echard's History of England does indeed contain a lengthy account oftheCarte Blanche, but this need not detain us, since the entire passage is taken, withoutacknowledgement but with a few verbal alterations to suit eighteenth-century taste,from a much earlier work, namely, Flagellum; or^ The Life and Death, Birth and Burial

25

of Oliver Cromwell, the late Usurper.,^ 2nd edn. (1663), pp. 67-9. The whole account isso detailed and circumstantial that it must be reproduced here:

There was mention made before of Coll. John Cromwell; this Gentleman upon the news theStates of Holland had received of this proceeding against the King, at the instance of OurSoveraign, then Prince of Wales residing at the Hague, to them, to mediate and interpose in thebusinesse, was pitch'd upon by them as the only fit person, because of his relation to Cromwell,(who was looked upon there as the only Contriver of this mischief) to be employed in a Messageto him, with Credential Letters from the States, whereunto was added a Blank with the KingsSignet, and another of the Princes, both confirmed by the States, for Cromwell to write his ownconditions in, if he would now preserve the life of the King.

The Collonel putting some confidence in what Oliver had formerly told him, willinglyundertook the Errand, and forthwith repaired to London (just before the Kings Martyrdome)and found him out at his house, but so recluse and lock'd up in his Chamber, with an Orderthat none should know he was within, that he could not be admitted till he had told his name.After mutual Salutations the Collonel desired a word or two in private, which being granted,he began roundly to tell him ofthe flagitiousnesse ofthe Fact, now almost ready to be committed,and how detestable it sounded abroad, adding that of all men living he never should haveimagined that he would have had a hand in it, having protested so much for the King in hishearing. Whereupon Cromwell fell to his old shifts, telling him that it was not he but the Army,that 'tis true once he did say such words, but times were altered, and Providence seemed todispose things otherwise; that he had prayed and fasted for the King but no return that waywas yet made to him; whereupon the Collonel stepping back clapt the Dore to, to the agastingof Cromwell who suspected and [sic] assassinate and coming close to him. Cousin said he it is notime to dally with words in this matter, look you here said he (pulling out the abovesaid Papersout of his pocket) Uis in your own power not only to make your self but your Posterity, Family,and Relations happy, and honourable for ever, otherwise as they have changed their names beforefrom Williams to Cromwell, so now they must be forced to change it again, for this Fact will bringsuch an ignominy upon the whole generation of them, that no time will be able to wipe away.

Cromwel here paused, and seemed to ponder with himself, and after a little space said Cousin,I desire you will give me till night to consider of it, and do you go to your Inn, but go not to bed tillyou hear from me, I mill confer and consider further about the businesse. The Collonel did so, andabout one of the Clock (within an Evening or two of the Murther) a Messenger came to himand told him he might go to Bed, and expect no other answer to carry to the Prince, for theCouncil of Officers had been seeking God as he also had done the same, and it was resolved bythem all that the King must dye.

We must now face the former ofthe two questions which Gilson, with his customaryeconomy of words, posed, namely, if the story be true? The verdicts of historians, onlya few of which can be mentioned here, show a remarkable lack of uniformity. Someignore the story altogether, though whether because they regard it as unimportant orbecause they reject it as unworthy of credence remains unclear. Others are certainlyill-informed: for instance. Professor Charles Carlton, Charles / , the Personal Monarch(1083) p. 413, n. 18, says: 'The story that Prince Charles sent Parliament a signed andsealed blank sheet of paper on which they could write whatever terms were necessary

26

to save his father was an eighteenth-century fabrication. See note by J. P. Gilson inHarl. MSS. 9988 [sic.y On the contrary, as we have seen, the story was certainly inexistence not later than 1663, and so far as Gilson is concerned, he was careful to leavethe question of authenticity open.

S. R. Gardiner, History 0} the Great Civil War (London, 1893), vol. iv, p. 316,apparently accepted the story as historical, for he remarks: 'It was no secret that thePrince of Wales had sent a blank sheet of paper, signed and sealed by himself, on whichthe Parliament might inscribe any terms they pleased.' On the other hand. DameVeronica Wedgwood is clearly sceptical, remarking in The Trial of Charles I (London,1964), p. 170: 'Later it was said that he (the Prince of Wales) had sent a blank sheetof paper, signed and sealed, on which they {i.e. Fairfax and Cromwell) were to inscribewhatever terms they pleased for the preservation of his father's life. But in view of theKing's specific instructions to his son never on any account to allow considerations ofhis own or his father's safety to wring from him concessions that compromised theCrown or the Church, this seems improbable, and there is no hint of such an appealin the account given by Clarendon, at this time the close adviser of the Prince inHolland.' And in the note on p. 239 she adds: 'The earliest reference to the Prince'soffer is in W. Harris, Life and Reign of Charles / / , 1766, i, p. 40. The British Museumpossesses a blank paper sealed and signed by Prince Charles (Harleian MSS. 6988). Itis endorsed in an eighteenth century handwriting as his "carte blanche to save hisFather's head." But it is more probably a blank issued in connection with his currententerprises in Ireland.'

Lady Antonia Fraser, in her Cromwell, Our Chief of Men (London, 1973), p. 289, isconsiderably less sceptical: 'Among the frenzied solutions to Charles's safety whichmany tried to discover, there was one story of a mission "within a few days of themurder" by one of Cromwell's own relations, a Colonel John Cromwell who commandedan English regiment in the service of the Netherlands.' There follows a summary ofthe account in Flagellum, on which she remarks: 'the story rests on the imperfectauthority of Heath, but the language at least has a Cromwellian ring, and even ifover-dramatized by its author, it is not impossible that something ofthe sort happened,particularly as Cromwell was on amicable terms with many of his Royalist relations.. . . This same John Cromwell remained on terms with Oliver throughout the Protectorateand was even employed by him on some sort of Danish mission.'

However, by the time Lady Antonia had come to write her later volume, KingCharles II (London, 1979), p. 76, her attitude had changed to outright rejection ofthestory: 'That son [i.e. the Prince of Wales] was in the meantime in a state of turmoil anddespair. The only step he was not prepared to take on behalf of his father is the onesometimes ascribed to him in popular mythology—the presentation of a blank sheet ofpaper to the generals, bearing his signature, for them to name their own terms to savehis father's life. It had been dinned into Charles by the King that nothing was worththe sacrifice of the Church of England, whose preservation was bound up with that ofthe monarchy itself. If the generals had demanded a series of religious concessions,

27

Charles knew well his father would not have wished to live on those terms.' And inthe note at the foot ofthe same page she adds: 'The blank sheet of paper preserved inthe Bodleian Library, Oxford [sic], bearing the signature Charles P, said to be proofofthe story, is in fact some kind of Irish military instruction.'

The most bizarre account ofthe Carte Blanche is that given by Hester W. Chapman,The Tragedy of Charles II in the Years 1630-1660 (London, 1964), p. 119: 'In the thirdweek of January 1649 Prince Charles dispatched three copies of his famous carte blanche,a paper on which was written his signature and nothing else, accompanied by a letterasking Parliament to place above it whatever terms they desired in return for the King'slife. One of these was given to Charles I a few hours before his execution; he burnt it,so as not to compromise his son. Another was presented to Cromwell by a Royalistrelative. Colonel Henry Cromwell, and also destroyed. The third survived and is nowin the British Museum.' Unfortunately, the only reference Mrs Chapman gives for thisastonishing account is Baroness Suzette van Zuylen van Nyevelt, Court Life in the DutchRepublic, i638-i68g (London, 1906), p. 132. But this work not only makes no mentionwhatsoever of the Carte Blanche, but expressly disclaims any intention to discuss suchmatters, saying: 'It is unnecessary to dwell here on the fate of this embassy [i.e.the delegation from the States General], and on that of Charles's attempt to save hisfather's life at the cost of any sacrifices on his part that his enemies might be willingto accept.'

It is plainly incredible that the Prince of Wales would have sent a copy of the CarteBlanche to his father, since this disobeyed the King's strict instructions to his son tomake no concessions. If we eliminate this part of Mrs Chapman's account, we are stillleft with two cartes blanches, one presented to Cromwell by Col. Henry [sic] Cromwell,and destroyed (by whom?), the other in the British Museum. The former is clearly amuddled version of the story in Flagellum, which, however, makes no mention of theultimate fate of the document; whether this is to be identified with the one in the BritishLibrary will be considered below.

The doubts which have been expressed about the authenticity of the story certainlycommand respect, but it does not seem to me impossible that in so desperate a situationthe Prince might have taken such an unprecedented step even in contravention of hisfather's orders. It was, after all, an empty gesture, since he had no authority to giveany undertakings in matters of state during his father's lifetime, and nothing which hecould have offered personally would have stood any chance of acceptance. Possiblyhistorians have fought shy of accepting the story because of its sensational character,although it is no more sensational than other well-attested episodes at this extraordinaryperiod of our history. And if the question be asked whether there is any parallel for sodramatic a gesture in a critical situation, the answer is, surprisingly, yes.

On 6 February 1649, only a week after the King's execution, the Duke of Hamilton,who had been in custody since his surrender at Uttoxeter after the battle of Preston,was brought to trial. He was condemned to death, and between this date and hisexecution on the 9th extraordinary efforts were made by his relatives to secure a reprieve.

28

In Edmund Ludlow's Memoirs, ed. Firth (Oxford, 1894), vol. i, p. 222, we read thatthe Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of Holland, and Lord Capel 'were executed a day ortwo after [i.e. after the Commons had rejected their petitions for reprieve] in the NewPalace-Yard before Westminster-Hall, in pursuance of a warrant signed by the courtto that purpose, the parliament refusing to hearken to the Earl of Denbigh, who proposed,on behalf of Duke Hamilton his brother-in-law, to give them a blank signed by thesaid Duke, to answer faithfully to such questions as should be there inserted'.

The nature ofthe document proposed by the Earl of Denbigh is not clear: obviouslyHamilton could have undertaken to answer questions without executing a 'blank'.Probably the intention was that a statement naming Royalist conspirators would beinserted over Hamilton's signature. There were in fact rumours at the time that he wasready to make such 'discoveries'.'^

This point is, however, of no importance for our present purpose. The crucial factis that a 'blank' was proposed to save a condemned man from the scaffold, and to thisextent the parallel with the 'blank' said to have been offered by the Prince of Walescould not be more complete. Indeed, it even seems possible that the one may have inspiredthe other. However this may be, the story of the Prince's 'blank' now appears in atotally different light, and there no longer seems any reason why we should not acceptit as a historical fact.

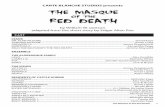

We now turn to Gilson's second question, 'If true, whether this is the paper?', andproceed to consider Harley MS. 6988, fol. 222, a photograph of which I reproduce (fig.i), I believe for the first time.^ That the signature and signet-impression are genuinelythose of the Prince of Wales is unquestionable. For comparison I also illustrate {fig. 2)another 'blank' of the Prince, a kind of promissory note, in the Public Record Office;^no doubt this is one of the 'blanks for other purposes' which Gilson had in mind inhis note quoted above.

The watermark of the Harley manuscript consists of a shield of arms coupled withthe letters VAL in monogram, surmounted by a crown. The letters VAL can of coursebe arranged in any order, and may therefore signify Liefke, Lyntje, or Lodewyk VanAelst, papermakers at Appeldorn and Veluwe in the first half of the seventeenth century.

I may add that the document itself is of course undated, but must necessarily be notlater than 30 January 1649, when the Prince automatically succeeded to the throne onthe death of his father.

We now turn to the endorsement, which reads as follows:

Prince Charles hisCarte Blanche to the Parl*to save his Father's Head

1648

Many other documents in the volume bear endorsements in the same hand, with suchlegends as 'Given by Dr. Mead 1730/1', 'Given by Dr. Stratford', and, frequently, theinitials 'W.O.', 'W.O. 1730', or, in full, 'W. Oldys 1730', 'Wm. Oldys 1730', etc.^ There

29

Fig. I. 'Carte Blanche' of Charles, Prince of Wales. Harley MS. 6988, fol. 222. Dimensions oforiginal 30 x 20 cm

^. 2. Blank promissory note of Charles, Prince of Wales. Public Record Office, SP 16/516,no. 137. Original dimensions of portion of document reproduced 20.4 x 20.9 cm. Reproduced

by kind permission of the Controller of HM Stationery Office

can be no possible doubt that the hand of all these endorsements, and of the table ofletters at the end ofthe volume (fois. 240-57) is that of William Oldys (1696-1761),antiquary, bibliographer, and, eventually, herald, and that the documents so endorsedare part of the collections which Oldys is known to have sold to Edward Harley, 2ndEarl of Oxford, in 1731. These collections included 'manuscripts historical and political,which had been the Earl of Clarendon's, collections of Royal Letters, and other papersof state'.

Oldys is not the most impressive of witnesses: C. E. Wright, The Diary of HumfreyWanley (London, 1966), vol. i, p. lxxiv, describes him as 'an inaccurate and gossipywriter'. We have, of course, no means of knowing what evidence he had for writingthe endorsement on the Carte Blanche; the most probable explanation is that he knewthe story in Flagellum, or its repetition in Echard's History, and concluded that thiswas the document in question. Is the identification correct? Certainty is of course

unattainable, but it seems to me very difficult to fault Oldys's conclusion.^ As we haveseen, there are two well-attested cases of a carte blanche being offered as a last-ditchattempt to save a desperate situation; and the only such situation which could haveinduced the Prince to utter so dangerous a document was the imminent execution ofthe King. In these circumstances it seems almost perverse to refuse to accept the CarteBlanche as the very document with which the Prince of Wales sought to preserve hisfather's life, and the answer to Gilson's second question must therefore be: Yes.

1 It is remarkable that the good old English word'blank', common in the sixteenth and seventeenthcenturies, should have been completely ousted (itis marked as 'Obsolete' in the New EnglishDictionary) by the French term carte blanche.Perhaps the best-known historical example of itsuse is the affair of the 'Spanish blanks' whichrocked Scotland in December 1592—the discovery,or alleged discovery, of sheets of paper blankexcept for a valediction addressed to a royalpersonage (assumed to be Philip of Spain) andthe signatures of one or more Scottish noblemen.For an example of the term in everyday use cf.G. C. Moore Smith, The Letters of DorothyOshorne to William Temple (Oxford, 1928), p. 34(letter 16 of 2 April 1653): *I did receive bothyour letters, and yet was not sattisfyed butresolved to have a third: you had defeated [i.e.disappointed] mee strangly if it had bin a blank,not that I should have taken it ill, for 'tis asimpossible for mee to doe soe, as for you to givemee the occasion, but though by sending a blankwith your name to it, you had given mee a powerto please my self, yet I should ne'er have don'thalf soe well as your letter did', etc.

2 William Harris, A Historical and Critical Accountof the Life of Charles II (London, 1766): in anumber of textbooks this is quoted as if it werethe primary source of information about the CarteBlanche, although in fact it contains only a briefand inadequate mention of it, namely, 'It is said,the Prince also sent to the Parliament, to prescribe

the terms on which his Majesty's head might besecured. This is not improbable; as I know thereis in the British Museum a blank paper, at thebottom of which, on the right hand, is written,Charles P. and on the left, opposite thereunto, aseal is affixed; and on the back there is written,in another hand. Prince Charles his carte blancheto the Parliament to save his father^s head.''

3 The author is identified by Anthony Wood asJames Heath.

4 Hilary L. Rubinstein, Captain Luckless: James,First Duke of Hamilton, i6o6-i64g (London,1975), p. 231. According to Mrs Rubinstein, whoquotes Ludlow as her authority, 'it is said thatDenbigh tried in vain to persuade Parliament toissue carte blanche for Hamilton to sign'. But thisis not what Ludlow says.

5 Although there is an engraving of it, on a reducedscale, in Sir Henry Ellis's Original Letters Illustra-tive of English History, ist ser., vol. iii (1824),frontispiece.

6 SP 16/516, no. 137.7 For full details, see C. E. Wright, i^on/e^/Zar/mm ^

(London, 1972), p. 471, under Harley MS. 6988,and under the various names there listed, par-ticularly William Oldys (p. 261).

8 The account in Flagellum (and Echard) states thatthere were two 'blanks', one with a signet impres-sion and one signed by the Prince, but this mustbe an error. Obviously seal and signature mustgo together, as in the two cartes blanches illustratedhere. Oldys of course would have realized this.