Carol Hess King of Harlem

-

Upload

olaya-aramo -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Carol Hess King of Harlem

-

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

1/19

From Buster Keaton to the King of Harlem: Musical Ideologies in Lorca's "Poeta en NuevaYork"Author(s): Carol A. HessSource: Anales de la literatura espaola contempornea, Vol. 33, No. 2, El Teatro de FedericoGarca Lorca en la Construccon de la Identidad Colectiva Espaola (2008), pp. 329-346Published by: Society of Spanish & Spanish-American StudiesStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27742556.

Accessed: 03/01/2014 17:34

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at.http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Society of Spanish & Spanish-American Studiesis collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access toAnales de la literatura espaola contempornea.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sssashttp://www.jstor.org/stable/27742556?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/27742556?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sssas -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

2/19

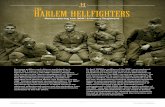

FROM BUSTER KEATON TO THEKING OF HARLEM:MUSICAL IDEOLOGIES IN LORCA'SPOETA EN NUEVA YORK

CAROL A. HESSMichigan State University

El paseo de Buster Keaton of 1925, with its discontinuityand elements of surrealism, has been said to embody Lorca'srejection of rationality and realist theater (Vilches de Frutos40). Similarly, Poeta enNueva York, the fruit of Lorca's stayin the great metropolis during 1929-30, has been tagged assurrealist (MacKinlay 157), with at least one critic notingconnections between the "sequences of images" in the poemsand the Bu?uel-influenced screenplay El viaje a la luna, alsoa New York project (Morris 134). Another point in commonbetween Buster Keaton and Poeta enNueva York is that eachinvolves a black man. In the former, he appears briefly onstage and eats his straw hat; in the latter, the "King ofHarlem" wears a janitor's uniform and wields a spoon toscoop out crocodiles' eyes or beat on monkeys' rear ends.Both images challenge our interpretive faculties; indeedPoeta enNueva York as a whole has been tagged not only asone of Lorca's "most enigmatic and challenging" works (DelRio ix) but as "opaque" and "well-nigh uninterpretable"(McKinlay 163, 167).One potential interpretive tool, however, is music. C.B.Morris has noted that the straw hat inBuster Keaton evokesthe minstrel show, a musical genre rife with racial stereo

111/329

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

3/19

112/330 ALEC 33.2 (2008)typing. For Morris, this reference to "physical and to spiritualdebasement" links theman with the straw hat to the King ofHarlem, who in turn embodies Lorca's empathy forAfrican-Americans (Morris 135). Several scholars havecommented on this empathy, which is also seen as related toLorca's "hating the abstract, the formal, the regulated; andas loving the natural, the spontaneous, the sensual"(Predmore 38). Perhaps it is not surprising that music surfaces so frequently in discussions of Poeta en Nueva Yorksince these very qualities -naturalness, spontaneity, sensuality- are widely associated with music, often consideredopen-ended, subjective, and lacking in interpretive specificity.Accordingly, much aesthetic discourse grants to music thecapacity to stand in as an ineffable Other in relation tomoreconcrete realities, a topic amply treated in aesthetics andmusic criticism (Flinn 6-7).Yet although many critics have detected musical structures inPoeta enNueva York, there is little discussion eitherof specific musical genres or of their ideological content. Thisleaves us with a fascinating lacuna. Rather than try to hearmusical structures in the poems, this essay explores thatmusical-ideological lacuna, centering on African-Americansviews on black music, black music's status as the "music ofthe oppressed," and the primitivist discourse frequently employed by both critics of black music and commentators onthe New York poems. For as Morris observes, in Poeta enNueva York "things are not what they appear to be ... peopleare not what their uniform makes them seem" (Morris 134).As it turns out, the musical elements in Poeta enNueva Yorkare not "what they seem" either; in fact, exploring their ideological status complicates rather than clarifies the alreadydifficult poems. Yet the questions thus raised enhance ourunderstanding of the environment in which Lorca pennedthese enigmatic verses. Further, a sense of musical contextcan prompt us to appreciate anew not only Poeta en NuevaYork but the rich ambivalence that confronts us whenever wehear music in Lorca.

The influence ofmusic on Lorca's works and lifehas beennoted so frequently that only a representative sample of

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

4/19

CAROL A. HESS 113 I331poetic-musical commentary is necessary here. Lorca himselfidentified Amor de Don Perlimplin con Belisa en su jard?n asan "operita," as he did for Lola la comedianta, his unfinishedcollaboration with Manuel de Falla (Ucelay 207).l VirginiaHigginbotham has noted the centrality of popular songs inthe dramatic structure ofBodas de sangre, Yerma, and Do?aRosita la soltera (Higginbotham 779). Venturing intomusicalterminology -with all the risks this entails-, John Crow findsinDo?a Rosita, the "musical skeleton of statement, contrast,and re-statement of the given theme"; additionally, Crownotes that "variations are afforded by the language of flowerswhich play up and down the scales ofRosita's emotions likeunseen fingers on the harp" (Crow 91). More concretely,Christopher Maurer explores Bodas de sangre, linking portions of its text and structure to Johann Sebastian Bach'scantata no. 140, "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme" (Maurer94). Mapping musical genres onto Lorca's language also surfaces in discussions of his poetry. The Poema del cante jondo,for example, is said to draw on the siguiriya, the sole?, andthe petenera, all musical forms (Gibson 110).2 Along relatedlines, critics invariably note Lorca's skill as a pianist, hisfamiliarity with the classical piano repertory, and hisdevotion to cante jondo and traditional Spanish songs, severalof which he arranged in pleasing if conventional harmonizations. Despite his stature as a modernist author, hismusical tastes seem fairly traditional, privileging Bach andMozart, two icons of theWestern musical canon in whoseworks intellect, balance, formal clarity, and a sense of transcendent beauty are widely recognized.In the criticism of Poeta en Nueva York we find threekinds of references tomusic: biographical (detailing Lorca'smusical activities in New York), aesthetic (analyzing thepoetry itself inmusical terms), and ideological (interpretingthe poems in light of the social implications of the music towhich Lorca felt drawn).3 Before delving into the third -themost substantive- we can summarize the other two. Lorca'smusical activity inNew York was multi-faceted. By playingthe piano and singing Spanish songs for his new acquaintances in America he did not have to depend on English;

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

5/19

114/332 ALEC 33.2 (2008)indeed, Gibson suggests that Lorca's "musical abilitiesopened all doors and were the principal key to his success inNew York" (Gibson 253). Lorca served as Director of theMixed Choirs of the Instituto de las Espa?as in the UnitedStates, rehearsing and then directing a concert of Spanishsongs in summer 1929 by that student group; later, he participated in the ensemble (Eisenberg 237, 241; de On?s 324). Inaddition, it seems that Lorca learned by heart various Negrospirituals (del Rio xxxii), although we have towonder how theblack dialect in which this repertory is often performedsounded in Lorca's voice given that even after months in theStates he still pronounced "with Spanish phonetics the few[English] words he was forced to use" (del Rio xvii).As a listener, Lorca evidently absorbed a variety ofmusical styles. Crow refers to his "fascination for negro jazzorchestras," which "often led him toHarlem dives in the latehours of the night where he would listen to the music withveritable rapture" (Crow 3).4 One such jazz club was EdSmall's Paradise, towhich Lorca later referred in a lecture onPoeta en Nueva York (Lorca 351). This expensive establishment, known as the "Hottest Spot inHarlem," featured livemusic and floor shows and had a dance floor so small thatpatrons were said to be entitled to a dime's worth of spaceeach (http://www.nyupress.org/bigonion/tour03.html accessed 3 June 2007>). Lorca also appears to have heard blackmusicals in at least three Harlem theaters: the Lafayette, theLincoln, and the Alhambra (Gibson 278). We are unsure ofhis opinion of the Protestant hymns he undoubtedly heard aspart of a church service in which, as he reported to hisparents, "everything human, everything consoling, everything beautiful [was] suppressed" (Gibson 254).5 GivenLorca's love forBach, it is unlikely that the view expressed tohis parents that "the word Protestant is a synonym for absolute idiot" (Gibson 254) extended to the cantor of Leipzig;moreover, the Lutheran chorales that appear in nearly everyone of Bach's cantatas are similar in structure and melodiccontent to many a hymn by John Wesley or Lowell Mason,which Lorca might well have experienced in a Protestantservice.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

6/19

CAROL A. HESS 115 1333As for ways in which Lorca's musicality emerges in theactual poems, scholars have dealt with rhythm and soundcolor, ordinary dimensions of poetic language but considered

especially marked in Lorca. In Poeta en Nueva York, forexample, Higginbotham sees music as a metaphorical language whose sounds and rhythms "define the fundamentalsense of space and time" (Higginbotham 784). Drawing onBarthes, she describes Lorca's absorption of New York'ssounds as an act of "decoding," of reacting to and understanding his new environment (Higginbotham 779), implicitly arguing that such "decoding" involved references to"cultivated" musical genres that contrast with the abjectcries of pain elsewhere in the poems. Among the "genresevoked" she finds the "rondo, nocturne, ode, waltz, andintermezzo (Interludio)."6 Others, however, seem less persuaded by such strategies. McKinlay, for example, notes thatalthough "Vals en las ramas" contains "recurring enumeration in threes throughout, suggesting the timing of waltzmusic," there is "little else in the poem [that] has such adefinite connection" (McKinlay 163). In short, while awareness of musical genres and forms can challenge our ear andsubliminally enhance our understanding of the poems, it ishard to be convinced that Lorca's references to them aremore than suggestive -however powerful the suggestion maybe- rather than structurally integral to the poems. Anexample is the nocturne, as found in "Ciudad sin sue?o(Nocturno del Brooklyn Bridge)." The wide-ranging expressive potential of this genre, both in form and character,becomes evident when we compare two of Chopin's essays:the graceful Nocturne in A-flat Major, op. 32, no. 2, bestknown, perhaps, in its choreographed and orchestratedincarnation in Les Sylphides, and the stormy Nocturne in Cminor, op. 48, no. 1, nicknamed "The Prisoner." Given thatthe idea of "nocturne" applies to such a variety of poeticsounds, structures, and attitudes, it is difficult to hear itspresence in a musically explicit way even as we ourselves seekto "decode" theNew York poems.References to popular genres, especially African-Americanones, are more frequent in the literature on Poeta en Nueva

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

7/19

116/334 ALEC 33.2 (2008)York. Ian Gibson notes that Fernando de los R?os, with whomLorca traveled to America, found a kinship between cantejondo and "Black music," which he discussed with Lorca(Gibson 247). Likewise, Stone equates the depth offlamenco's "?Ay " with the spirit of the blues and suggeststhat in New York, "Lorca would realize that the Gypsy cantewas just one ofmany 'dialects' pertaining to a universal language of the oppressed ... [others being] the Blues and spirituals of the Blacks" (Stone 498); Enguidanos takes a similartack (Enguidanos 1). Lorca himself made such comparisons.Early in his stay, for example, he attended a party at whichhe was the only white and at which "a boy sang religioussongs [spirituals]" and "the Blacks sang and danced" (Gibson255). Shortly afterwards, he wrote his family, exclaiming"?Pero que maravilla de cantos S?lo se puede comparar conellos el cante jondo" (Gibson 255). Here, Lorca unwittinglyanticipated the nameless protagonist of Ralph Ellison'sInvisible Man, who, upon hearing a spiritual, finds it "as fullofWeltschmerz as flamenco."

As we have seen, Lorca encountered at least four genres ofblack music in New York: blues, jazz, spirituals, and blackmusicals. We may never know exactly what music he enjoyedat Ed Small's Paradise or what spirituals, ifany, he learnedby heart. Yet this uncertainty brings us to the first of ourideological considerations. Although each of these four genreswas associated with the African-American underclass, therewas little agreement among African-Americans themselves onhow black music was to be defined and what its prioritiesshould be. This lack of consensus can be seen in an anecdoteLangston Hughes related in 1926. Among other things,Hughes refers to Clara Smith, a popular singer, and to thepractice of "shouting," one of gospel music's more exuberantelements:

A prominent Negro clubwoman in Philadelphia paideleven dollars to hear Raquel Meiler sing Andalusianpopular songs. But she told [Hughes] a few weeks before she would not think of going to hear "that woman,"Clara Smith, a great black artist, sing Negro folksongs.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

8/19

CAROL A. HESS 117 I335And many an upper-class Negro church, even now,would not dream of employing a spiritual in its services.The drab melodies in white folks' hymnbooks are muchto be preferred. "We want toworship the Lord correctlyand quietly. We don't believe in "shouting." Let's bedull, like the Nordics," they say, in effect. (Walser 56)

Evidently in some circles, Andalusian popular music wasnot equated with black music; in addition, Hughes's attack onthe "quiet and correct" church service exactly parallelsLorca's impressions of white Protestant worship. The moreimportant point is that "upper-class Negroes" encouragedtheir brethren to assimilate even before the Lord, an attitude

Hughes despised. Yet the Philadelphia clubwoman was noisolated case. African-American journalist Dave Peyton scolded his readers on the pitfalls posed by jazz (which he sometimes found "mushy" and "discordant") in his weekly columnfor the Chicago Defender "The Music Bunch." In a piece from1928, he decried the "crude" style ofmany African-Americanjazz musicians while praising "the famous white orchestraswith their smoothness of playing, their unique attacks, theirnovelty arrangement of the score and other things that ...make for fine music," commenting that "we wonder whymost of our own orchestras will fail to deliver music as theNordic brothers do" (Walser 58-59).7 Clearly Peyton is equating -in anything but flattering terms- the much vauntedspontaneity ofAfrican-American jazz musicians with lazinessand lack of technical proficiency rather than with innategenius.

Other, more measured, views of black music arose fromthe leaders of the Harlem Renaissance. That artistic and intellectual movement of the 1920s, still viable during Lorca'sstay (Floyd 24), was dominated by the image of the "NewNegro," the title of a 1925 essay collection by philosopherAlain Locke. Locke envisioned the "New Negro" as ready toenter mainstream American society despite the obstacles thatlay ahead. One such obstacle was the notion, widely circulated, that at least one genre of black music, jazz, was immoral because it prompted sexual licentiousness. "Does Jazz

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

9/19

118/336 ALEC 33.2 (2008)Put the Sin in Syncopation?" was the title of a particularlyenergetic essay on the topic (Walser 32-36). Accordingly,many of the leading figures in the Harlem Renaissanceconsidered jazz, along with other types of black popularmusic, a "lower form" of expression (Floyd 4-5).What sort of music did they prefer? In general, themusical authorities of the Harlem Renaissance felt that vernacular African-American music could aspire to the formsand genres of the European canon. Maud Cuney Hare, forexample, attacked the music of "the illiterate, the unsophisticated" while praising "Art Music ... the output oftrained musicians whose creative works, composed accordingto an accepted standard of beauty, give aesthetic enjoymentto the cultured" (Cuney Hare 179-80).8 Rising to meet thischallenge were African-American composers Nathaniel R.Dett, James Weldon Johnson, and William Grant Still, toname just a few. Still, for example, drew on the Europeantradition, most noticeably in his chamber music and his fivesymphonies. Yet these works often referred to black music.For example, in the third movement of his "Afro-AmericanSymphony" of 1930 (titled scherzo, according to the European symphonic tradition), Still used a banjo, an instrumentassociated largely with African-Americans (Linn 441-42;Parsons Smith 114-51). This approach is comparable toFalla's use of cante jondo inEl amor brujo, the Madrid premiere of which in 1915 relied on a real flamenco singer,Pastora Imperio. Yet at the same time that both Still's andFalla's works could be seen as "elevated" musical expressionsof an underclass, both are complicated by musical reality.More than half the music in El amor brujo has little to dowith genuine flamenco sources (Hess 81) and in the case ofStill's scherzo, many saw the banjo as demeaning, drawing asit does on the tradition of blackface minstrelsy (Bakan 91). Asmusicologist Carl Dahlhaus would later assert in a differentbut related context, "what does and does not count as[identity] depends primarily on collective opinion" (Dahlhaus87-88).At the same time, some Harlem Renaissance figureschallenged the notion that black music should aspire to Euro

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

10/19

CAROL A. HESS 119 1337pean norms. Author Zora Neale Thurston, for example, criticized composers and performers for "taking 'good Negromusic' and making it into 'mediocre white sounds'" (Bakan35). Locke, who had no especially warm feelings toward jazz,took a middle ground. In his book The Negro and His Music,Locke did not necessarily disqualify jazz, blues, or otherforms of "Negro music." Rather, he objected to the commercialism that he felt "tarnished" them, feeling keenly the fateof black musicians who "know the folk-ways ofNegro music .. . [but] are in commercial slavery to the Shylocks [ ] of TinPan Alley, in artistic bondage to the ready cash of ourdance-halls, and the Vaudeville stage" (Bakan 31). Evenwhile evoking the specter of slavery, Locke remains optimistic, however. Although "[African-American] musicians withformal training are cut off from the people and the vital rootsof folk music," some African-American composers and performers had nonetheless "learned to openly study and admirethe folkmusic sources ofwhat ismost original and promisinginNegro music" (Bakan 31).To sum up thus far: while many whites may have viewedblack musical genres as "symbols of freedom from restraintforwhich the white intellectual longed . . . ardently" (Floyd4), African-Americans themselves disagreed on what musicbest represented them. Thus, the idea that the music Lorcaheard (and may have evoked directly in theNew York poems)was viewed unequivocally by the black community as thevoice of the "oppressed" should be approached with caution.

Our second ideological consideration relates to the commercialization of African-American music that Locke notes.Since Mamie Smith's 1920 recording of "Crazy Blues,"African-Americans had recorded and purchased blues music(Dougan 40-41), brisk sales of which reflected the strongsense of identity many African-Americans felt with thismusic. Yet after the onset of the Great Depression, the recording industry changed, and the communist party, viable inthe U.S. since 1919, surged in importance, especially inHarlem (Naison 115-65). These economic and political upheavals affected music. After several intellectual skirmishesover "proletarian music," that is,music that could speak to

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

11/19

120/338 ALEC 33.2 (2008)downtrodden workers with a sophisticated idiom (Seeger121-27), a more accessible musical language eventually wonout among white composers. This tendency to simplifymusical language coincided with efforts by the United StatesCommunist Party (USCP) to restyle itself terms of a homegrown, "American" profile. Mike Gold, for example, acolumnist for the Daily Worker, attacked "aestheticism" andcondemned the "use of Arnold Schoenberg

or Stravinsky as ayardstick [formusical criticism]" as "utopian" (Zuck 137).Nor did Gold note any particular distinction between theroles of folk and commercial music in the "working-classrevolution." "What songs do the masses of Americans nowsing?" he queried. "They sing 'Old Black Joe' and thesemi-jazz things concocted by Tin Pan Alley," adding "this isthe reality." If proletarian art had to convey "American"values, white composers now sought inspiration inAnglo-American folk music, which many had previouslydisdained.9A related phenomenon occurred in the African-Americanmusical community. In 1930, Gold could write that "theHarlem Cabaret no more represents the Negro Mass than apawnshop represents a Jew, or an opium den the strugglingChinese nation" (Bakan 90). But just a few years later, partyleaders were being instructed to defend Negro culture againstthe "white ruling class," in part, by listening to the recordings of Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, and W.C. Handy(Bakan 81). In addition, a new genre -swing- was being acclaimed as the voice of the oppressed. The term "swing" couldbe used interchangeably with jazz -black music- and the burgeoning popular music industry was quick to take it up(Bakan 5).Where do these upheavals leave our understanding ofLorca? Obviously, he did admire black music and did identifyit -along with himself- with the oppressed. Yet it is reasonable to propose that this music's status as the voice of oppressed came about in part because of increasingly Americanist sentiments during the Depression. Whatever "authenticity" or "sincerity" in the music itself (music that, aswe have seen, was criticized by some African-American lead

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

12/19

CAROL A. HESS 121 I339ers) was only part of the picture. Paradoxically, aiding andabetting this shift in status was the very commercialism-"?Ay,Wall Street "- that Lorca so passionately decried.10Our third ideological consideration regarding black musicis the critical penchant for primitivist discourse, especiallymarked in jazz criticism. As noted, some leaders of theHarlem Renaissance found jazz a "lower" musical form. Yetothers, mainly whites, viewed these supposedly primitivetraits favorably, much the way literary scholars have praisedLorca's depiction of "natural," "spontaneous," or "sensual"African-Americans. As Ted Gioia has argued, much of thisprimitivist discourse originated in France, where interest injazz was strong ever since the African-American bandleaderJames Reese toured France in the final months of the GreatWar, playing jazz-inflected numbers to great acclaim. SeveralEuropean composers were also drawing on black music, suchas Stravinsky inRagtime for Eleven Instruments and DariusMilhaud in La Cr?ation du monde, the latter inspired by avisit toHarlem in 1922. France, of course, was also a centerfor primitivism in the visual arts, as can be seen in Picasso'sinterest inAfrican masks, along with many other examples.Gioia notes that the firstmajor studies of jazz were by twoFrenchmen (Hugues Panassie and Charles Delaunay) and aBelgian (Robert Goffin). Their writings, which focus on thevirtues of primitive culture, were promptly translated intoEnglish. Panassie, for example, proposes that "primitive mangenerally has greater talent than civilized man. An excess ofculture atrophies inspiration, and men crammed with culturetend to ... replace inspiration by lush technique under whichone finds music stripped of real vitality" (Gioia 137). Goffin,also a champion of the primitive, more directly considers thequestion of race, attributing Louis Armstrong's abilities tothe fact that he is "a full-blooded Negro [who] brought thedirectness and spontaneity of his race to jazz music"; Goffinadds that while "Armstrong's gift is present in a fewNegroes," he could name "no white musician who is able toforget himself, to create his own atmosphere, and to whiphimself up into a state of almost complete frenzy" (Gioia137). As Gioia comments, these statements are "one of the

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

13/19

122/340 ALEC 33.2 (2008)earliest formulations of a stereotype which has lingered untilthe present day -a stereotype which views jazz as a musiccharged with emotion, but largely devoid of intellectual content, and which sees the jazz musician as the inarticulate andunsophisticated practitioner of an art which he himselfscarcely understands" (Gioia 137-38).

Compare these comments to a remark of Leon Bloy,quoted by Angel del Rio apropos Poeta enNueva York, namely, that "the unquestionable sign of every poet is theprophetic unconsciousness, the disturbing faculty of utteringto all men and at all times strange words, whose meaning hehimself does not understand" (del Rio xxix). Along similarlines, Richard Predmore observes that for Lorca, poetry"went beyond reason, consciousness, and social convention"(Predmore 10). And, much like the evocations ofArmstrong"whipping himself into a frenzy" just cited, Ben Belitt describes the "spontaneities of [flamenco] . . . the frenzy, theshudder, the paroxysm" and asserts that Poeta enNueva Yorkgoes even deeper than gitanismo" (Belitt xlv).Yet as critics exalt the primitive elements -the spontaneous, the natural- inPoeta enNueva York and relate themto black music, any parallel between such elements and theactual practices of jazz musicians does not hold up. Jazz isfilled with cues and patterns that are often quite complex.Jazz musicians do not simply play, reveling in some flow ofsound in which everything miraculously "comes out" allright. Rather, they practice patterns -licks- oftenmany hoursa day so that in the heat of battle, when the improvisation isgoing full tilt, there will be plenty of resources on which todraw. Also complicating the image of the unschooled jazzprimitive is the fact that even in Panassie's time, many jazzmusicians, including African-Americans, were well acquainted with the European musical tradition. These included ScottJoplin, Lil Hardin, Earl Hines, Fletcher Henderson, FatsWaller, and Art Tatum (Horn 237-57). Some, such as saxophonist Coleman Hawkins, studied music in college (Gioia140). (Henderson had a degree in chemistry but worked as asong-plugger because racial prejudice barred him from thesciences.) An oft-repeated anecdote in jazz circles concerns

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

14/19

CAROL A. HESS 123 ?341the notion that African-American jazz players were musicallyilliterate (Prouty 317-34). In fact, many could read musicperfectly well: they would, however, memorize the melodicoutlines so as to play without the score before the public, whocraved "spontaneity." In short, these noble savages were afairly disciplined lot. The idea, therefore, that black music is aprimitive utterance unmediated by intellectual rigor ormusical discipline ismisleading at best and an unfortunatestereotype at worst.11Let us return to theKing ofHarlem. As I have suggested,hearing musical structures in Lorca including actual jazzpatterns in this particular poem, may be problematic. Yetallusions to jazz are by no means absent. While some considerthe "king" motif to reflect nostalgia for a primitive Africa inwhich blacks had greater control over their destinies(Higginbotham 780), or Chorrojumo, the king of the gypsies(Gibson 256), "kings" were also common inU.S. jazz circles.Clarinetist Benny Goodman, one of several white "rulers" ofjazz's commercial empire, was known as "the King of Swing."Paul Whiteman was not only "the Man who Made a Lady outof Jazz" but the "King of Jazz"; indeed, in dedicating his1931 book to Louis Armstrong, Goffin declared him "the realKing of Jazz" (Gioia, 136). The presence of Count Basie andDuke Ellington has also prompted jokes about noble titles, anespecially grim irony given the hardscrabble lives so manyjazz musicians lived, especially African-Americans. The Kingof Harlem, trapped in his janitor's suit, embodies African-Americans' pain. Is his spoon, the only accessory Lorcaoffers him, a scepter, as some suggest? Is it a weapon withwhich to flail helplessly against the forces ofmaterialism? Oris it a percussion instrument with which to beat a relentlessrhythm, the meaning ofwhich his "subjects" dispute? WhilePoeta enNueva York emphasizes the collective plight ofAfrican- Americans, the King of Harlem is an individual, whostands out in relief from the faceless multitudes and theunforgiving landscape of industrialization and materialism.The paradox is that by presenting him as such, Lorcasuggests a unitary representation of African-American lifethat, as we have seen, was by no means precise, even in rela

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

15/19

124/342 ALEC 33.2 (2008)tion tomusic. Like the symbol ofminstrelsy in El paseo deBuster Keaton, the presumably indigestible straw hat, theKing ofHarlem's spoon can hardly be "what it seems."A final paradoxical note: neither was minstrelsy "what itseemed." At least in its early days, minstrels were rarelyblacks but whites who "blacked up" their faces with burntcork, participating, along with their public, in a play ofillusion and ritual that embodied racial tensions in the "safe"arena of the theater.12 A coherent concept of "black music" inPoeta en Nueva York remains similarly obscured. Yet theconflicting musical ideologies implicit in both it and El paseode Buster Keaton enhance our understanding of these works-and the criticism they have generated- and continue toinvite interpretation.

NOTES1. Collaborations with Falla that did see the light include not onlythe cante jondo contest of 1922 but the theatrical production ofEpiphany (6 January) 1923, enhanced with music ranging from theseventeenth century to Stravinsky, all performed with decidedlymodernist -if not downright parodie- instrumentation (Hess 132).2. As noted, such mapping can be problematic. Classifying the Primero romancero gitano as a rondo (Garc?a-Posada 25), for example,seems forced, given that the poem's repeat structure has little incommon with that of traditional rondo form, such as that found in

the last movement of Haydn's Symphony in G Major no. 88, or thefinal movement of Beethoven's Sonata in C Minor, op. 13 (the"Path?tique").3. Certainly many other factors are treated in discussions of Poetaen Nueva York. For example, Stone emphasizes Lorca's fragile emotional state when he arrived inNew York inJune of 1929 and thepsychological challenges of reconstructing his troubled identitythere (Stone 493-96) while Paul Binding proposes that Poeta enNueva York "presents us with a vision of America from a homosexual standpoint" (Binding 18).4. As several scholars have pointed out, Crow's account of Lorca'sstay in New York must be taken with caution. Here, for example,Crow refers to Lorca being "stirred deeply" by "the slides of thetrombone and the beats of the kettle drums" (Crow 3). One wonders

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

16/19

CAROL A. HESS 125 1343what sort of jazz combo would include kettle drums (timpani), muchless in a Harlem "dive."5. Unlike del Rio, Crow insists that Lora he did not learn spirituals

"probably because he imagined the usual monotonous kind ofProtestant hymns" (Crow 3-4).6. The Cuban son of the last poem is identified as a popular ratherthan cultivated genre. Higginbotham herself "evokes" the doubleconcerto in "Poema doble del lago Eden," which she finds "borrowsfrom the musical form of the double concerto or double choir toindicate multiple voices of equal importance" so that the poet speaks"with two voices, one from his past and the other as a commentaryon his former self (Higginbotham 782). Of course, many musicalforms involve "multiple voices of equal importance."7. Peyton might well be thinking here of bandleader Paul White

man, whose smooth arrangements earned him the moniker "TheMan Who Made a Lady out of Jazz."8. Cuney Hare also weighs in on what she considers the excessiveuse of syncopation in ragtime, through which, she claims, "themusical taste of the youth was being poisoned" (Cuney Hare 133).

9. Examples include Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, ElieSiegmeister, Henry Cowell, and other composers, both of art andcommercial music, who used either folk melodies, folk style, or drewon various aspects of Americana during this time.10. Even as commercialism was occurring in the name of "thepeople," black musicians were constantly being exploited, a phenomenon widely acknowledged in both scholarship and popular culture. See, for example, the 2006 movie Dreamgirls, directed by BillCondon.11. In addition to the paradoxes just described, Lorca's interest injazz put him at odds with Spain's leading critic, his friend AdolfoSalazar. If France embraced jazz with open arms, Spain was lessfriendly. Salazar complained of "toda clase de instrumentos ruidososque se encontraron a mano" in jazz, qualifying it as "una inmundacacofon?a sin gracia ni inter?s" (Palacios 210). Feeding Salazar'sdistaste was the culture of commercialism he considered jazz torepresent, which, as we have seen, was far from monolithic. Nor didSalazar refrain from ascribing the cultural limitations he perceivedin jazz to other aspects of American musical life. Referring sharplyto "la Bolsa de la M?sica," Salazar held that music criticism in theU.S. was "una de las m?s necias e insolentes de la profesi?n, y deuna ignorancia s?lo equivalente a su comercialismo" (Palacios 209).12. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, blacks participatedin minstrelsy (as did women) as its subject matter broadened to

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

17/19

1261 344 ALEC 33.2 (2008)satirize more aspects of contemporary life, among them women'ssuffrage.

OBRAS CITADASBakan, Jonathan. "Caf? Society: A Locus for the Intersection of Jazzand Politics During the Popular Front Era." Ph.D. diss.: York

University, 2004.Belitt, Ben. Translator's Foreword. Poet in New York. London:

Thames and Hudson, 1955.Binding, Paul. Lorca and the Gay Imagination. London: GMPPublishers, 1985.

Crow, John. Federico Garc?a Lorca. Los Angeles: University ofCalifornia Press, 1945.Cuney Hare, Maud. Negro Musicians and Their Music. WashingtonD.C.: The Associated Publishers, Inc., 1936.Dahlhaus, Carl. "Nationalism and Music." Between Romanticism

and Modernism. Trans, from the German by Mary Whittall.Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1980.79-101.

Dougan, John. "Objects of Desire: Canon Formation and BluesRecord Collecting." Journal of Popular Music Studies 18.1(2006): 40-65.Enguidanos, Miguel. "Del rey de los gitanos al rey de Harlem: SobrePoeta enNueva York" ?nsula 41.476-77 (1986): 1, 20.Eisenberg, Daniel. "A Chronology ofLorca's Visit toNew York andCuba." Kentucky Romance Quarterly 24.3 (1975): 233-50.Flinn, Caryl. Strains of Utopia: Gender, Nostalgia, and HollywoodFilm Music. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.Floyd, Samuel A. Jr. "Music in the Harlem Renaissance: AnOverview." Samuel A. Floyd Jr. ed. Black Music in the Harlem

Renaissance: A Collection of Essays. New York, Westport, andLondon: Greenwood Press, 1990. 1-16.Garcia Lorca, Federico. "Unpoeta en Nueva York." Obras completas.III. Arturo del Hoyo, ed. and coord. Madrid: Aguilar, 1986. 47-58.

_. Obras completas. V. Miguel Garc?a Posada, ed. Madrid:Akal, 1992. 24-26.

_. La casa de Bernarda Alba. M- Francisca Vilches deFrutos, ed. Madrid: C?tedra, 2005.

Garc?a-Posada, Miguel. "La m?sica." Federico Garc?a Lorca. Obrascompletas. V. Miguel Garc?a Posada, ed. Madrid: Akal, 1992:24-26.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

18/19

CAROL A. HESS 127 / 45Gioia, Ted. "Jazz and the Primitivist Myth." Musical Quarterly 73.1(1989): 130-43.Gibson, Ian. Federico Garc?a Lorca: A Life. London and Boston:Faber and Faber, 1989.Hess, Carol A. Sacred Passions: The Life and Music of Manuel de

Falla. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.Higginbotham, Virginia. "Sounds of Fury: Listening to Poeta enNueva York" Hispama 69.4 (1986): 778-84.Horn, David. "The Sound World of Art Tatum." Black Music

Research Journal 20.2 (2000): 237-57.Linn, Karen Elizabeth. "The 'Elevation' of the Banjo in LateNineteenth-Century America." American Music 8.4 (1990):441-64.

MacKinlay, Neil. "The Dehumanisation of Poeta en Nueva York."Journal of Iberian and Latin American Studies 7.2 (2001):157-71.

Maurer, Christopher. "Bach e Bodas de sangre. Antonio Trudu, ed.and coord., Federico Garc?a Lorca nella m?sica contempor?nea.Milan: Edizioni Unicopli, 1986. 91-100.Morris, C.B. This Loving Darkness: The Cinema and SpanishWriters, 1920-1936. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.Naison, M. Communists inHarlem During the Depression. Urbana,

Chicago, and London: University of Illinois Press, 1983.On?s, Federico de. "Pr?logo." Colecci?n de canciones populares ant

iguas. Federico Garc?a Lorca. Obras completas. V. Miguel Garc?aPosada, ed. Madrid: Akal, 1992: 321-26. Originally published inRevista Hisp?nica Moderna 6 (1940): 369-71.Palacios Nieto, Mar?a. "El Grupo de los Ocho y lam?sica en Madriddurante la dictadura de Primo de Rivera (1923-1931)." Ph.D.diss. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2006.

Parsons Smith, Catherine. William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University ofCalifornia Press, 2000.Predmore, Richard L. Lorca's New York Poetiy: Social Injustice,Dark Love, Lost Faith. Durham, NC: Duke University Press,1980.Prouty, Kenneth E. "Orality, Literacy, and Mediating Musical

Experience: Rethinking Oral Tradition in the Learning of JazzImprovisation." Popular Music and Society 29.3 (2006): 317-33.

Riis, Thomas Laurence. Just Before Jazz: Black Musical Theater inNew York, 1890-1915. Washington: Smithsonian InstitutionPress, 1989.

R?o, Angel del. "Introduction." Poet m New York. London: Thamesand Hudson, 1955.

This content downloaded from 156.35.192.2 on Fri, 3 Jan 201417:34:45 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/13/2019 Carol Hess King of Harlem

19/19

128 / 346 ALEC 33.2 (2008)Seeger, Charles. "On Proletarian Music." Modern Music 11.3 (1934):121-27.Stone, Rob. "Quiero llorar: Lorca and the Flamenco Tradition inPoeta enNueva York." Bulletin ofHispanic Studies 11.5 (2000):

493-510.Ucelay, Margarita. "Operita de c?mara." Federico Garc?a Lorca. Don

Perlimpl?n con Belisa en su jardin. Margarita Ucelay, ed.Madrid: C?tedra, 1998.Vilches de Frutos, M? Francisca. "Introducci?n." Federico Garc?aLorca. La casa de Bernarda Alba. M.- Francisca Vilches de

Frutos, ed. Madrid: C?tedra, 2005.Walser, Robert, ed. Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History. NewYork and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.Zuck, Barbara A. A History ofMusical Americanism. Ann Arbor, MI:UMI Research Press, 1980.