Cardano and the Gambler's Habitus

Transcript of Cardano and the Gambler's Habitus

Studies in History

Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

and Philosophyof Science

www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsa

Cardano and the gambler�s habitus

Lambert Williams

Department of the History of Science, Harvard University, Science Center 371, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

Max-Planck-Institut fur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Wilhelmstrasse 44, 10117 Berlin, Germany

Received 1 August 2004; received in revised form 6 October 2004

Abstract

Cardano�s Liber de ludo aleae is subjected to a reappraisal based largely on considerations

of practice in the 16th century gambling arena. It is argued that Cardano�s purported failure to

secure the foundations of a rigorous probability calculus can be explained as something that

occurred precisely because of his gambling exposure, not in spite of it.

� 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Girolamo Cardano; Probability; Gambling.

0039-3

doi:10.

E-m1 M2 C

Jerome Cardan a donne un traite De Ludo Aleae; mais on n�y trouve que del�erudition & des reflexions morales. (Pierre Remond de Montmort, 1713)1

In those matters in which no time is given and guile prevails, it is one thing toknow and another to exercise one�s knowledge successfully, as in gambling,war, dueling and commerce. For although acumen depends on both knowledgeand practice, still practice and experience can do more than knowledge. (Girol-amo Cardano, ca. 1564)2

681/$ - see front matter � 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1016/j.shpsa.2004.12.002

ail address: [email protected] (L. Williams).

ontmort (1713), p. xl.

ardano (1961), p. 41.

24 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

1. Introduction

On a standard narration, the probability calculus handed down to us today

finally took flight after the Pascal/Fermat correspondence of 1654, and that corre-

spondence was in turn brought about by the Chevalier de Mere�s gambling puzzle

about the division of stakes in interrupted games. And yet gambling activity goes

back millennia—tracing the origins of human gambling behavior is more a matterfor cave excavation than the hunting down of manuscripts. From these two facts

(viz., that the early theory of probability was somehow �about� gambling on the

one hand, and the large temporal gap between the commencement of gambling

and the commencement of strictly probabilistic theorizing on the other), it is all

too easy to find oneself leaping into a rather presentist framework: why did it take

so long for the extrapolation from empirical gambling data to theoretical calculus

of chance to occur? Why did so many chances to make what looks like an obvious

connection go begging?3

In this paper, I will reappraise the work of Girolamo Cardano, one of the most

fascinating and perhaps understudied characters of the pre-1654 world to be rou-

tinely accorded �near-miss� status under some version of the presentist framework.

History has been generally unkind to both him and his key work for the purposes

of the paper, Liber de ludo aleae. The verdict of Montmort on this work, given

above, appears even worse when one considers that this two-line mention is all

that Cardano receives in a tome running to more than four hundred pages.

And nor have I pulled out an exceptional case. In the foremost anglophone his-tory of probability to appear in the 19th century—that of Todhunter—Cardano�streatise is dealt with in little over two pages, some lines of which are spent on such

peripheral concerns as the treatise being �so badly printed as to be scarcely

intelligible�.4

Admittedly, one work swimming against this generally negative current came in

the form of Øystein Ore�s Cardano: The gambling scholar, but I hope to show that

in his elevation of Cardano to persecuted savant where others saw a loathsome

degenerate, Ore still flirts with a use of the presentist framework that obscures cer-tain features of Cardano�s project.5 That is, Ore is not trying simply to persuade us

that Cardano, the quintessential enfant terrible, has been misunderstood. Rather,

some part of the motivation behind his rethink is that we finally award Cardano

the crown of �father of modern probability�.6 For the purposes of this paper, how-

3 For more in this vein, see Margolis (1993), Ch. 6.4 Todhunter (1865), p. 2. Indeed, the combined contributions of Cardano, Kepler, and Galileo detain

Todhunter for a mere six pages. A small anomaly should also be noted here. Øystein Ore, of whom much

more will written in this paper, also takes Todhunter as a �marker� of the reception accorded Liber de ludo

aleae. However, he inserts �written� in place of �printed� here, giving Todhunter�s remark rather more

critical bite than was perhaps intended. See Ore (1953), p. 144.5 David (1962), p. 54.6 See, for example, Ore (1953), pp. 153–154, 167, 177.

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 25

ever, a slightly different position will be taken up. In reappraising Cardano�s rathercurious book, I admit some doubt as to how fruitful it is to regard the work as a

�hit or miss� based on a metric of how close the author came to flipping a gestalt

switch, reframing the domain of chance and successfully formulating some version

of the theory we possess today. Rather, it seems to me that Cardano was doing

something altogether different, and that the story to be told is one hinging crucially

on practice, experience and material culture in the 16th-century Italian gamblingden.

Structurally, this paper falls into two parts. The first is an exposition of the formal

content of Liber de ludo aleae. I examine three of the main achievements that have

been attributed to Cardano�s work, namely the conception of probability as the ratio

of favourable to possible cases, an anticipation of the law of large numbers, and an

anticipation of the power law for repeated events. Expanding on a distinction first

made explicit by Ore and layered in with all three of these topics, I shall sketch Card-

ano as frequently oscillating between two methods. The first, or �standard�, method isone readily understood in terms of the modern calculus. The second method seems

initially mysterious, but I hope to show that it can be plausibly glossed as an early

approximation algorithm that makes close to perfect sense once rooted in its gam-

bling context.

That said, the general motivation of the first part is to get a clean framing of

Cardano�s thinking—in old-fashioned language it would be called the internalist side

of the project. The only real contextual triggers that I squeeze in the first section are

these:

(a) The participatory nature of gambling feeding into Cardano�s attempt to grasp

mathematical expectation, and

(b) Consideration of the speed at which games were played, and, more specifically,

how the seemingly bizarre second method I have just mentioned may have

enabled crucially quick computation along with a rather pragmatic �some deci-

sion procedure is better than none� kind of reliability.

Left at that, the grand �gambling context� I refer to would be rather an anemic

creature. So whilst I make no claim to provide an exhaustive or wholly determin-

ing context in the second part—and, for reasons mentioned towards the end, nor

would I want to—it is nevertheless in this second part that I flesh out what

gambling practice and material culture might have implied for Cardano�s proba-

bilistic project. The special case of cheating, the deployment by Cardano of the

distinction between games of chance and games of skill, the material make-up

of cards: all of these, I argue, contribute some support for claims made in thefirst part.

The conclusion that all this sets up has both its negative and its positive

dimensions. On the negative side, I spell out a few qualifiers about the occasion-

ally circumstantial and (I think necessarily) partial status of my argument that

must be taken into account. But hopefully of much greater interest is the positive

claim: Cardano�s inability to provide the foundations of a formal calculus is not

26 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

something that plausibly stands in spite of his accrued wisdom at the gaming

table. Instead, Cardano�s project took the shape it did precisely because of his

gambling.

2. Content

What I mean to examine first is the �formal� content of the book on games of

chance, in which methods for calculating odds are both worked out and put forth

for specific scenarios and games. Of course, one must be cautious in bandying the

word �formal� about for such cases as the one before us. Cardano�s book predates

by a good margin all of the notation, axioms, and rules of inference that we now

associate with the probability calculus; thus in cases where old mathematics is trans-

lated into new form one immediately smells the foul stench of possible anachronism.

However, I have deliberately kept such cases of translation to a minimum, and whereit is done my intention (crudely) is to draw out what I take to be the bare structure of

Cardano�s thinking for the purposes of exposition rather than any substantive histor-

ical argumentation. Clearly, there are no hard and fast rules on offer. A balance has

to struck between considerations of authenticity and considerations of clarity, and

hopefully I am somewhere near the mark. Moreover, at a general level the lack of

formalism cannot be too great an impediment to reading Liber de ludo aleae as at

least potentially a probabilistic text, for if the lack of rigorous axioms and notation

rule out such a consideration of Cardano�s work, then out goes the Pascal/Fermatcorrespondence as well—and arguably every other contribution made prior to Kol-

mogorov�s seminal paper of 1933 in which the now current textbook axiomatisation

of probability came into being.7 I take it that this mass junking would not represent a

particularly desirable outcome, and so will help myself to a cautious and historicized

use of �formal� for the remainder of this paper.

So what are the formal milestones that have been attributed to the book? One sug-

gestion is that Liber de ludo aleae gives the first rigorous treatment of sample spaces

by working out the number of ways in which a specified number of dice might fall.8

It is certainly true that this is carried out in Cardano�s book, but priority would seem

to fall to a much earlier poem entitled De vetula.9 However, Cardano does take vital

steps that are absent from the earlier poem. As Gliozzi states, in Liber de ludo aleae:

7 This point is echoed in Gigerenzer et al. (1990), p. xiii and s. 3.6 (�Specialized knowledge�).8 The foreword of Samuel Wilks in the Gould translation of Liber de ludo aleae embraces exactly this

view.9 This is available as Harleian MS. 5263. Some controversy exists over its dating and authorship, but a

common enough view attributes the work to Richard de Fournival, a chancellor of Amiens cathedral. This

would make a likely date for the poem sometime between 1220 and 1250. Kendall has more to say on this,

although the author is very quick to assume that its contents were quickly �lost to sight� (Kendall, 1956, p.

6) and that the central idea had to be rediscovered by Cardano. David differs on this last point, arguing

that �since (Cardano�s) reading was wide in the process of his collection of facts, it is not fanciful to assume

that he knew of De vetula� (David, 1962, p. 58). In the works cited here, neither author suggests how they

might have arrived at such differing conclusions.

10 G

upon h

the gam

also gr11 Th

hard a

greater

can sti12 C13 Ib

contrib

to just

two or

contrib

for one

an enu

higher

abstrac

quotat

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 27

The concept of probability was introduced, expressed as the ratio of favorableto possible cases; the law of large numbers was enunciated; the so-called �powerlaw� . . . was presented; and numerous problems relating to games of dice,cards, and knucklebones were solved.10

I deal with these attributed milestones in turn. That Cardano formulated the

probability of an event as the ratio of favourable to possible cases seems beyond

question. Having commenced the �technical� side of his project at Chapter Nine,11

he arrives at the following in Chapter Fourteen:

So there is one general rule, namely, that we should consider the whole circuit,and the number of those casts which represents in how many ways the favor-able result can occur, and compare that number to the rest of the circuit, andaccording to that proportion should the mutual wagers be laid so that one maycontend on equal terms.12

A brief aside on Cardano�s terminology will be useful: the �circuit� can be glossed as

something like the sample space, only without reference to the probabilities attached

to the sample points; another term cropping up frequently is �equality�, which is sim-

ply the circuit divided by two. Importantly, Cardano does not arrive at this last state-ment without some difficulties. In an important passage from Chapter Nine, entitled

�On the cast of one die�, he notes that:

One half the total number of faces always represents equality; thus the chancesare equal that a given point will turn up in three throws, for the total circuit iscompleted in six, or again that one of three given points will turn up in onethrow. For example I can as easily throw one, three or five as two, four orsix. The wagers therefore are laid in accordance with this equality if the dieis honest.13

liozzi (1971), p. 66. The games of particular interest to Cardano and those who have commented

is work include primero (a forerunner of modern poker), fritillus (a forerunner of backgammon),

e of sors, and multiple card games. Considerable time, both in primary and secondary literature, is

anted to games involving tali and astragals.

e implied distinction between technical and non-technical parts of the book is not intended in any

nd fast way. As the book is too much of a mixed bag for that, I justify this only by pointing to the

density of calculation coming after Chapter Nine than before. Still, even after Chapter Nine one

ll find such discussions as �why gambling was condemned by Aristotle�.ardano (1961), p. 18.

id., p. 9. Immediately after this passage comes what I believe to be a crucial remark: �these facts

ute a great deal to understanding but hardly anything to practical play�. There is some ambiguity as

how this afterthought might be interpreted. Ore�s reading is that since most games involved at least

three dice, claims about the single case are unimportant, and it is in this sense that �hardly anything� isuted to �practical play�. However, hot on the heels of Cardano�s derivation of the possible outcomes

dice, he gives us derivations for two dice and three dice. That is, the same reasoning that gives him

meration of possible outcomes for the single case are in fact carried over almost immediately to

cases. So more plausible than Ore�s reading, I think, is to interpret this remark as one about

tion. On this view, and in keeping with the general thrust of this paper, it is precisely because the last

ion invokes theoretical reasoning that it contributes to the understanding but not to the practical.

28 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

In his subsequent computations, Cardano takes a given number of favorable

cases and sometimes divides them by both the circuit and equality. By today�slights, dividing the favorable cases by the circuit is an absolutely correct method

for computing probability. Dividing the number of favorable cases by equality,

however, seems very strange indeed. However, I suggest that one can make sense

of this by training in on a sentence laid down some seven chapters before the

�formal turn� of Chapter Nine. Almost as a throwaway, Cardano instructs us ofa reason why painting, music and so on are preferable activities to gambling:

�One cannot gamble alone, whereas the (other) delights can be enjoyed even when

we are by ourselves�.14 That is, gambling is of necessity a participatory pastime.

And what Cardano is seemingly up to with his division of favourable cases by

equality comes close to an anticipation of what we now term mathematical expec-

tation, only tinged by the presumption that two people must be accounted for—a

presumption coming straight from the gaming table and into his calculations. If

true, this puts Cardano into an interesting lineage with the probabilists that wouldcome after him. For as Daston has argued, they too would construe expectation,

by this point rather more explicitly, as a natural unit of analysis:

14 Ib15 D

p. 692

What was probability about in the second half of the 17th century? The time-honored answer is: games of chance. This answer has much to be said for it, forthe pioneers of mathematical probability . . . all solved gambling problems. Butit is also incomplete and misleading: incomplete, because it omits the otherimportant applications concerning evidence, demography and annuities . . .misleading, because it suggests that gambling provided the early probabilistswith the conceptual framework in which they posed and solved their problems.Upon closer examination, the works of the early probabilists turn out to be more

about equity than about chances, and more about expectations than about

probabilities.15

Of course, this thesis regarding participation so far bears the character more of

assertion than argument. And so to cash things out in a slightly more formal register,

a player might want to determine the right amount to bet on winning an amount Qfor the occurrence of an event x. Assuming Pr(x) is known, what we now call the

expectation of the player is simply Pr(x)Q. However, in the case of gambling both

players chip in, such that Q is made up of a stake a from one player and a stake

b from the other player with a = b. From the vantage point of one of the gamblers,

it seems more natural to take expectation relative to one�s own stake than to the total

amount Q in evaluating wins or losses. In which case, the expectation E of the player

with stake a in a game looks like this:

E ¼ PrðxÞQ ¼ 2 PrðxÞa:

id., p. 2.

aston (1988), pp. 13–14; my emphasis. See also Chapter Two of the same work, and Hacking (1990),

.

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 29

And so to the punch line: this is exactly equivalent to dividing the number of

favourable cases by equality and then multiplying the result by stake a. I would

urge that it is in this vein, as a form of �proto-expectation�, that Cardano�s use

of equality shows its usefulness.16 And, what is more, this also provides the first

case in which Cardano puts forward two methods: one readily understandable

as correct in terms of the calculus we possess today, and another which seems ini-

tially mysterious and perhaps even wrongheaded, yet which on closer inspectionturns out to have a useful function once we appreciate the gambling context from

which it plausibly arose.

I now wish to suggest that this use of two methods is by no means a one-off in

Liber de ludo aleae.17 Although at the beginning of this piece I expressed a meth-

odological disagreement with Ore�s approach, one very interesting thread in his

work is the identification of two different methods for arriving at probabilities

themselves—one he calls the �standard method� and the other �reasoning on the

mean� (or �ROTM� hereafter).18 I believe one can push a little further with this dis-tinction than Ore himself did, and show that whilst the first method appears cor-

rect to the modern reader, the initially bizarre second method is some kind of early

approximation algorithm that again bears the stamp of Cardano�s gambling expe-

rience.19 In a few expository lines I shall set out what this second method is, before

then going on to expand on how it may be fairly viewed as a gambler�s rule of

thumb.

Consider the probability of throwing a six with one throw of a fair dice. In

the long run the six faces should appear equally often, and so the chance of get-ting a six in any one throw is 1/6, or 0.1667. For Cardano�s earlier statement

that �the chances are equal that a given point will turn up in three throws� tohold true, he must simply be taking this initial probability and multiplying by

the number of dice thrown. So in the two dice cast the ROTM probability

would be given by (2 · 0.1667) = 0.33 and in the three dice cast by

(3 · 0.1667) = 0.5. These numbers contrast with the correct probabilities of 0.31

for the two dice cast, and 0.42 for the three dice cast. So whilst ROTM lines

up exactly with the now standard method in the single case, it diverges evermore widely for higher casts (for reasons that will soon become clear, it is cru-

cial to note that two or three casts seems to have been the norm in actual games

16 See also Ore (1953), pp. 149–150. Other ways of casting this material have been suggested. Bellhouse

(n.d.), for example, reads this moment as one in which Cardano�s gambling project reflects a deep-seated

connection to the theme of Aristotelian justice.17 A question beyond the immediate purview of this paper is whether the double method phenomenon

crops up and does work elsewhere in Cardano�s corpus. Certainly a scan of Libri�s commentary on how

Cardano determined the weight of air in Opus novum de proportionibus suggests that two methods were

used here as well. However, at the time of writing I do not confess to know whether further scrutiny of this

might yield interesting results. See Cardano (1663) and Libri (1840), Tome III, p. 175.18 Ore (1953), p. 145.19 In fairness, Ore has allowed this as a possibility for a special case he discusses involving critical

numbers. However, admitting the possibility is more or less where the discussion stops, and no

systematically positive case is built. See Ore (1953), p. 155.

30 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

discussed by Cardano). The extent of divergence for up to six dice is given as

Fig. 1.

Throughout the book Cardano often starts out with the ROTM approach, as

when he examines the probability of getting at least one given point (say, a six)

from a cast of three dice. He correctly computes the circuit as being 216 (or

6 · 6 · 6), and then using ROTM gets a probability of 108/216. However, as he

realizes in Chapter Fourteen, this is not strictly correct since it double countsthe casts in which more than one six appears. At this point he goes over to the

standard method to get his new probability of 91/216, and all subsequent calcula-

tions he performs for this specific example are correct.20 But there are other cases

in which this method switch does not occur. In Chapter Eleven, for instance, Card-

ano probes the question of how many attempts a player should be reasonably al-

lowed for a certain outcome on which bets have been laid to come about, for

example, the number of casts of two dice needed for double sixes to appear. Here

he does not switch from ROTM to the standard method, and consequently ends upwith figures at variance with the correct probabilities.21 Later in the same chapter

we see the same pattern for the probabilities pertaining to three casts of two dice.

Again the calculations do not get beyond ROTM, and Cardano ultimately leaves

the problem with only the ROTM answer and what I believe is a very telling

remark:

20 C

first six

thirty

dice 3,

(5 · 5)21 Se22 C23 Ib

This knowledge is based on conjecture, which yields only an approximation andthe reckoning is not exact in these details; yet it happens in the case of manycircuits that the matter falls out very close to conjecture.22

It now remains to argue that ROTM is essentially a gambler�s rule of thumb. Of

course, that it represents a �rule of thumb� in some general sense comes for free on the

back of the last quotation. What makes it plausibly a gambler�s rule, I would suggest,

is the speed at which calculations can be done. Speed of calculation would certainly

have been needed, for as Cardano tells us in a passage on the hard facts of gaming

practice:

It was right for Hannibal to make fun of the philosopher who had never seen abattle line and was discoursing on war. Thus it is with all games . . . when they

are played rapidly and time is not given for careful thought.23

ardano (1961), p. 17. His reasoning for the new probability must be along the following lines: if the

occurs on dice 1, then the other two dice might show any face giving (6 · 6) = 36 cases. A further

come from the case in which a six shows on dice 2 with five possible faces on dice 1 and any face on

i.e. (5 · 6) = 30. Finally, if a six shows on dice 3 with five possible faces on dice 1 and 2 we have

= 25 cases. In total, then, we have (36 + 30 + 25) = 91.

e Ore (1953), pp. 154–155.

ardano (1961), p. 12; my emphasis.

id., p. 42; my emphasis.

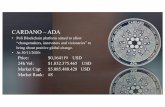

Fig. 1. Comparison between standard and ROTM methods.

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 31

At least on Cardano�s narration, rapid pace of play appears to be one regard in

which gaming has changed over the years. Even the game of chess, which in

today�s professional form at least can be a very drawn out affair, was played at a

breakneck speed in which, mixing metaphors somewhat, the participants would need

to be squarely and constantly on the ball to keep their heads above water.24

Looking again at Fig. 1, ROTM traces a straight line and the standard method

does not. Taking virtually any of the dicing problems from Liber de ludo aleae and

getting an approximate value using ROTM can be done in one�s head in seconds.The standard method takes slightly longer. And yet there are certain features of

ROTM that Cardano must have known to be empirically wide of the mark, for

instance that the probability of getting at least one six in six throws is unity. I pos-

tulate that Cardano held on to such a rule under the assumption that some algo-

rithm is better than none. For games involving up to three dice, ROTM only

diverges from the standard method at the second decimal place—perhaps good en-

ough in the heat of a gaming session to keep the shirt on one�s back. Finally, I

wish to suggest that it is Cardano�s attachment to ROTM that sometimes makesadoption of the standard method so difficult. ROTM, the gambler�s rule of thumb,

always comes ahead of the standard approach throughout Liber de ludo aleae, ex-

cept in those telling cases where there is no method switch whatsoever. I suggest,

not for the last time in this paper, that the constraints separating Cardano from a

�pure� calculus do their work exactly because he was a gambler, not in spite of his

being one.

Switching now to two other achievements attributed to Cardano�s book, the

sections in which he is commonly thought to be getting close to the law of large

24 David (1962), p. 57.

Fig. 2. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The cardsharps (I bari), ca. 1594, 94.2 · 130.9 cm. Copyright

� 2005 by Kimbell Art Museum.

32 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

numbers and the power law are also ones in which his reasoning is frequently based

on ROTM rather than the standard method. Here is Ore�s comment on ChapterThirty-Two, in which Cardano discusses �mean number�:

25 O

Cardano�s principle of the reasoning on the mean (ROTM) has alreadybeen mentioned. It is clear from this that he is aware of the so-calledlaw of large numbers in its most rudimentary form. Cardano�s mathematicsbelongs to the period antedating expression by means of formulas, so thathe is not able to express the law explicitly in this way, but he uses it asfollows: when the probability for an event is p, then by a large numbern of repetitions the number of times it will occur does not lie far fromthe value m= np.25

Again it seems that Ore could have made a further and by no means trivial point

here: Cardano�s failure to give the law of large numbers in the form that would ulti-

mately come from Jakob Bernoulli in 1713 does not, I think, hinge solely on a lack of

expression through formulas or on the fact that he lacked some conception of a limit.

What keeps his grasp of the law �rudimentary� is precisely his reliance, once again, on

ROTM. The section of Chapter Thirty-Two that Ore regards as a near miss here isworth quoting in full:

re (1953), pp. 170–171; my parenthetical addition.

26 C27 Ib28 Ib29 Ib

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 33

But in general it is to be observed, both for dice and for knucklebones, thatsince both of these complete the circuit in as many throws as there are faces,the die in six and the astragal in four, so in any one throw of any number ofeither dice or astragals, even if there should be a hundred of them, each makesup all possibilities in the same way . . . Thus, in the case of six dice, one ofwhich has only an ace on one face, and another a deuce, and so on up tosix, the total number is 21, which, divided by 6, the number of faces, gives 31/2 for one throw. However, the rule is not general; but in the case of mostthrows, it will turn out less than 3 on account of the excess of the greater num-bers, which have to be computed.26

The key claim here is to the effect that what we now call expectation and arithmetic

mean will line up for a suitably large number of repetitions. Perhaps regarding this as

close to anticipating the law of large numbers is fair, but the method used is once

again clearly that of the gambler.

Consistently enough, this very same pattern emerges in sections where Cardano

is supposedly close to the third cited achievement of his curious manual: the power

law for repetitions. The last section of Chapter Fourteen is devoted to this, and

one exemplar is the case of throwing at least one ace with three dice. Having takencorrect initial probabilities (he quotes odds of 91 to 125), he then gets a figure for

the probability of an ace in two successive casts by squaring these initial numbers,

giving odds of 8281 to 15,625, or �about 2 to 1�.27 The case of three successive casts

he derives by raising the initial odds by a power of three to get 753,571 to

1,953,125, or �very nearly 5 to 2�, and so on.28 Transferring his numbers to decimal

form, the probability for the two dice case is 0.35 and 0.28 for the three dice case,

whereas the correct values here would be 0.18 and 0.07 respectively. In the next

chapter he realizes his error by focusing on the special case of an event with oddsof 1 to 1:

But this reasoning seems to be false, even in the case of equality, as, for exam-ple, the chance of getting one of any three chosen faces in one cast of one die isequal to the chance of getting one of the other three, but according to this rea-soning there would be an even chance of getting a chosen face each time in twocasts, and thus in three, and four, which is most absurd. For if a player withtwo dice can with equal chances throw an even and an odd number, it doesnot follow that he can with equal fortune throw an even number in each ofthree successive casts.29

ardano (1961), p. 56.

id., p. 18.

id.

id., pp. 18–19.

34 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

In attempting to correct this mistake, Cardano promptly makes another by assert-

ing that in three throws of a dice there is one case with points that are all even and

eight in which there is at least one odd point. The first figure is correct, the second is

not and should be seven. The attempt at a general law is later infected by this move.

As Ore points out:

30 O31 C

When there is equality in a single throw, the general rule . . . should be that theodds are 2n � 1 to 1 for repetition in each of n casts. But Cardano states theodds as n2 � 1 to 1.30

For n = 2, the mistake will not be apparent. However for n > 2 we can see the prob-

lem emerge:

For three successive casts we shall multiply 3 by itself; the result is 9; takeaway one; the remainder is 8. The proportion of 8 to 1 is correct for 3 suc-cessive casts, and for four casts this proportion is 15 to 1, and for five, 24 to1. Thus in 125 casts, there will be only five sequences of throws in theirproper places, that is, with the same number of consecutive even throws,so that they may begin with an odd number either in the first or the sixthor the eleventh place. For otherwise there would be more than five consecu-tive even throws.31

The penultimate sentence is significant: Cardano clearly thinks that in 125 casts

there should be 5 occurrences of 5 consecutive even throws. There is no reason

for this belief in light of the standard method; it only makes sense in light ofCardano�s attachment to ROTM. Now although this particular stop-start saga

rolls on in the text for a few paragraphs beyond the point I have reached here,

enough is in place for my general argument to hold. Even where ROTM is not

being explicitly used as a basis for calculation, the gambler�s intuitions that lie

behind it still hold sway over Cardano�s thinking to such an extent that it causes

him to move in directions that appear strange at first blush. In sum, Liber de ludo

aleae is underpinned by the author�s acquired gambling practice and experience,

and not any push towards a pure abstract calculus. Just how the contingenciesof practice and experience might have constrained him is a question I now

address.

3. Practice, experience, material culture

One matter raised explicitly by Cardano, and perhaps the best route into an

assessment of the role of practice in his work, is cheating, a phenomenon that in turnrequires us to import the dimension of material culture. There is one chapter in his

book devoted to �the hanging dice box and dishonest dice� (Chapter Seven) and an-

other entitled �on frauds in games of this kind� (Chapter Seventeen). The former is in

re (1953), p. 165.

ardano (1961), p. 19.

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 35

several respects the less interesting of the two, although it still contains several points

of note. It is here that Cardano suggests �a threefold testing� to insulate oneself

against an unfavorable die, and he also claims that the slope of the dice box in

the middle of a gaming table can have serious effects on the outcome (positive if

the box slopes towards you, negative should it slope away). Finally, he states in this

chapter that:

32 Ib33 Ib34 C35 Ib

edition

rested

string

collusi

. . .if the board catches the light from the side opposite to you, then this is bad,since it disturbs your mind; on the other hand, it is to your advantage to have aboard against a dark background. Again, they say it is of benefit to take upyour position facing a rapidly rising moon.32

This short passage offers us a telling insight into the sort of book Cardano produced,

and simultaneously a reason as to why many commentators find it frustrating.

The first sentence offers what looks like straightforward, practical and plausible

advice—playing into glaring light is worse than playing against a neutral back-ground if you are keen to remain focussed. And yet next, as if it were the only logical

route available, he makes his claim about the rising moon.

A further reason for bringing up Chapter Seven is that it provides a nice back-

ground for the more important Chapter Seventeen. It is in Chapter Seven, for exam-

ple, that Cardano asserts �there are even worse ways of being cheated at cards . . . one

must take note of any disparity�.33 And indeed, having spent comparatively few lines

dealing with fraud in dice games,34 Chapter Seventeen contains a fairly exhaustive

survey of the sharp practices common in cards:

As for those who use marked cards, some mark them at the bottom, some atthe top, and some at the sides. The first kind are marked quite close to the bot-tom and may be either rough or smooth or hard; the second are marked withcolor and with slight imprints with a knife; while on the edges cards can bemarked with a figure, a rough spot, with interwoven knots or humps, or withgrooves hollowed out with a file. Some players examine the appearance ofa card by means of mirrors placed in their rings. I omit the devices ofKibitzers—the organum, the consensus, and the like.35

id., p. 7.

id.

heating with dice is still mentioned quite explicitly. See Ibid., p. 6.

id., p. 27. It is instructive to reproduce a translator�s footnote that accompanies this passage in the

I have worked with: �The ‘‘organ’’ was a loose floor board under the table on which one player

his foot, receiving signals from an accomplice who moved the board slightly, usually by pulling a

from another room. The �consensus� is an unknown device; the word itself means complicity or

on�.

36 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

In other passages Cardano also explicitly mentions the practices of casting cards

away from a hand,36 soaping the deck,37 and more besides, occasionally issuing

some remedy for players finding themselves on the wrong end of such dismal strat-

agems. Note the implicit corollary: that the deployment of pared down mathematical

models in such an arena might not be all that useful for winning games. More will be

said on this point, which is further reinforced by such sketches of the gambling den

as Reith�s:

36 Ib37 Ib38 R39 C40 Ib

Unobserved and unregulated by the law . . . illegal taverns were home to ahierarchy of card sharps—�takers-up�, �versers� and �robbers�—practiced inthe various techniques by which an honest player—a �cousin�—could berelieved of his money. The clandestine goings-on in these hells frequently

made the operation of chance a mere secondary consideration in the outcome

of a game.38

Armed with this kind of information I would like to develop a locally tailoredmaterial culture argument that both sheds more light on Cardano�s own gambling

practice and (I shall argue) offers at least some insight into why his account of prob-

ability is distinct from, rather than a pale approximation of, the later project of Pas-

cal, Fermat and the research tradition they generated. Most of the odds worked out

using ROTM in Liber de ludo aleae are those arising from games of chance (or, one

might say in light of Cardano�s metaphysics, games of luck). Yet my reading of the

text leads me to suspect that (a) Cardano was interested far more in games of skill,

and, working in reverse to interrogate the obvious presupposition, that (b) it is noflight of fancy to assert that such a chance/skill distinction was clearly formed in

his mind. So, two pieces of evidence point to Cardano having grasped this chance/

skill distinction at its most general. Firstly, in the very opening chapter he explains

that

Games depend either . . . on industriously acquired skill, as at chess; oron chance, as with dice and with knucklebones; or on both, as withFritillus.39

Then in Chapter Twenty-Two he tells us:

Some games use dice, that is, the play is open, and others cards, that is,play is concealed. Each kind is again sub-divided, since some games consistsolely of chance, especially dice . . . But some join to chance the art of play,as fritillus in dice and in cards taro, ulcus, triumphus and the like. Thereforeit is established that games consist either of luck alone, or of luck andart . . .40

id., p. 24.

id., p. 27.

eith (1999), p. 71; my emphasis. See also Bellhouse (1993).

ardano (1961), p. 1.

id., p. 36.

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 37

Support for my claim that Cardano�s preference was for games of skill—and as he

tells us himself (albeit indirectly) these were generally card games—can be gleaned

from the following set of judgments in Chapter Twenty-Four, entitled �on the differ-

ence between play with cards and play with dice�:

41 Ib42 C

minim

section43 Tw

�The chhere.

44 H

In play with dice you have no certain sign, but everything depends entirelyon pure chance . . . But in cards, apart from the recognition of cards fromthe back there are a thousand other natural and worthy ways of recognizingthem which are at the disposal of a prudent man. In this connection thegame of chess surpasses all others in subtlety. It is subjected little or notat all to the arbitrariness of chance . . . So it is more fitting for the wise

man to play at cards than at dice and at triumphus rather than at other

games.41

I take it from Cardano�s ruthlessly frank autobiography, that he would certainly be

inclined towards placing himself (or at least the hybrid of him and his daimon) in thecategory of wise, and thus it would follow that his own preference would be if not for

pure games of skill then certainly for games with a good mix of skill and chance.42 As

far as material culture is concerned, there is an already noted matter of interest

regarding recognition of cards from the back. Works dealing with the history of

playing cards are in general (and, it should be said, understandably) far more inter-

ested in the front of the cards. If one�s concern is the skewing of probabilities by

cheating, however, then it is the backs of the cards that perhaps matter more. Con-

sider, for starters, the scene from Caravaggio given as Fig. 2:The unfortunate player being duped here is in possession of cards that are com-

pletely blank on the back, and, although I would not want the entire argument to

hinge on evidence from depictions, this rendering is repeated in the work of both

Georges de la Tour and Valentin de Boulogne.43 It would appear that up until some

measure of standardisation in the 19th century this was something of a norm—cards

were often completely blank or had a single one-directional design on the back. Ital-

ian cards from the period of interest in this paper, and with which we may plausibly

assume Cardano to have been familiar, stand out from those of other countries byhaving a single figure, flower or occasionally a coat of arms on the back.44 Now

blank cards are obviously easy to mark, and those with a one-directional pattern

id., p. 40; my emphasis.

ardano (1930). For reasons of space, my references to Cardano�s autobiographical corpus are

al. However, one could readily broaden the field of evidence on which my thesis rests by attending to

s of these works that treat prediction, the interpretation of signs, and so on.

o paintings by de la Tour (�The cheat with the ace of diamonds� and a very similar piece entitled

eat with the ace of clubs�), and also de Boulogne�s �The cardsharpers� are the works I have in mind

argrave (1966), p. 231.

38 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

can be put into the deck a certain way around to distinguish high cards from low

ones.45 This, I think, makes the potential for significant skewing of probabilities

quite plausible.

So now it seems possible to pull together the threads of a coherent argument:

Firstly, the notion of probability is easier to read off from games of chance than

games of skill—that Cardano would agree is borne out by the fact that most of

his �formal chapters� in which he is calculating odds (roughly speaking, chapters nineto fifteen) concentrate solely on dicing, and also by the fact that his discussion of

odds in card games has a far more qualitative feel in comparison. Secondly, I hope

to have established that games of chance were not as interesting to Cardano as games

of skill, and we have already seen that for Cardano the label of skill applied more

often than not to card games. Thirdly, even allowing that the formulation of a cal-

culus could have been channeled through his more developed interest in skill-depen-

dent card games, the actual material make up of such cards at the very least creates

conditions of possibility such that some of the games he participated in would havebeen probabilistically skewed to the extent that our now standard method might not

be noticeably recognisable as better than ROTM-esque intuitions. And even for

games in which this was not in fact the case—I leave as an interesting open question

what formal demarcation criteria for skewed versus non-skewed games might have

been at Cardano�s disposal—I have already argued above that an epistemic tension

existed between utility and precision, and that in general Cardano had grounds to

prefer more of the former at the expense of the latter.

In conclusion, then, three quick points. Firstly, this is in some ways a circum-

stantial argument relying more on intuitions about plausibility than any smoking

guns. This of course has its problems and drawbacks, but hardly singles the pres-

ent paper out in current research on the history of science. There is something

deep here for sure, but full reflection on the matter deserves consideration in its

own right. Secondly, the argument as it stands is partial, and I think necessarily

so. What I mean by this can best be seen in a comparison between this paper and

20th-century sociological and psychological analysis of the gambling persona.

Where access to first person reporting permits, 20th century research has often in-cluded certain experiential dimensions as a crucial part of the gambling story.46

To scholars in this tradition it seems perfectly reasonable to assert that such

things as the phenomenology of time or the desire for mental and physical escap-

ism should be considered.47 Theirs is a tack to which I broadly subscribe, and

Cardano and several other sources of the period do give us some very teasing in-

45 This last point is mentioned in Reith (1999). See also Sifakis (1990), p. 216.46 A good survey of this literature can be found in Reith (1999), Ch. 4.47 On the phenomenology of time, see Reith (1999), pp. 134–143. Huizinga treats the topic of physical

escapism in his classic workHomo ludens; his account of the gambler is of one �stepping out of real life intoa temporary sphere of activity with a disposition all of its own� (Huizinga, 1949, p. 8). Mental escapism is

scrutinized in the work of Caillois and Leiseur. Caillois described the joy gamblers get from their �attempt

to momentarily destroy the stability of perception and inflict on it a kind of voluptuous panic on an

otherwise lucid mind� (Caillois, 1962, p. 23). Leiseur (1984) gives a slightly different sketch of the gambler

as one living in a �twilight zone� or �dream state�.

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 39

sights that could well have been used.48 However, it is my judgment that taking

odd lines of text from a source—and that is effectively all we have—and using

these to rebuild an entire mindset would take us beyond the bounds of plausibility

arguments and uncomfortably close to outright speculation.

These first two concluding points being in some way negative, I shall close on a po-

sitive note. The argument here is not one that deploys an all-encompassing frame-

work or global worldview that purports to explain why no-one came up with aconception of probability owing to their being subsumed under a �paradigm of divi-

natory faith� or some such lofty thing. Rather, it is an argument partly and locally

explaining why Cardano might not—the reason being that this was arguably not

his intended project, that he was doing something different.49 If this is so, then what

might strike us at first as an obvious tie between experiential gambling data, practice

and the lofty theory of probability begins to unravel. I suggest that part of the reason

that probability as we now think of it failed to emerge in Cardano�s mind is because

of, not in spite of, his practices and experiences in the gambling den. Other, somewhatmore global arguments do of course exist. One particularly striking argument is that

of Daston, who maintains that Cardano�s failure to view the world deterministically is

a key factor standing between him and the formulation of the calculus.50 My own

argument is intended to provide local support for such views, not to replace them.51

48 A few examples may be desired. In the last note I mentioned such categories as the phenomenology of

time and escapism, and Cardano touches on both of these topics. On the topic of time, and in a statement

blending perfectly with the picture of gambling temporality as a series of constantly refreshing �now�moments, Cardano writes that �play with cards requires only judgment of one�s present holdings and of one�sopponent�s. To conjecture about the present is more the part of a prudent man� (Cardano, 1961, p. 39). Thenon the issue of what motivated him to gamble, he tells us that �it was not a love of gambling, not a taste for

riotous livingwhich luredme, but the odiumofmy estate and a desire to escape, which compelledme� (ibid., p.73). Again this lines up with latter day commentary such as that of Huizinga. In attempting to sketch the

experiential dimension of early gambling, though, perhaps the last word should go to Charles Cotton. InThe

compleat gamester, he wrote that �gaming is an enchanting witchery . . . an itching disease . . . a paralytical

distemperwhich drives the gamester�s countenance, always in extreams, always in a storm so that it threatens

destruction to itself and others, and, as he is transported with joy when he wins, so, losing, is he tost upon the

billous of a high swelling passion, til he hath lost sight both of sense and reason� (Cotton, 1674, p. 1).49 It has been pointed out to me by Tony Grafton that this sort of locality argument could well serve as a

bridge between Cardano�s gambling pursuits and his astrological project. In astrology, Cardano was

insistent that the reading of a horoscope was a deeply important task that could never be framed in

absolute rules. He described such work as analogous to inspecting a jewel, involving a degree of tacit

knowledge that cannot be boiled down to a readily communicable decision procedure. So the claim would

be something like this: both in gambling and in astrology, the most pressing type of analysis for Cardano

was local, concrete and situationally embedded: a less than ideal background for arriving at an abstract

and general conclusion (private communication, 1 March 2004).50 Daston (1988), esp. pp. 36–37. Her view is nicely summed up in two sentences from this excerpt:

�determinism, far from stifling mathematical probability theory, actually promoted it. A calculus saddled

with Cardano�s daimon had no future�. See also Gigerenzer et al. (1990), and the very nice treatment of

Siraisi (1997).51 My compatibilist take on the local and global arguments appears to be one that Daston herself might

agree with, for she mentions what I take to be examples from both classes in Daston (1988), p. 124: �thecombination of skill and chance in many games, the irregular casting of dice and other gambling devices,

belief in streaks of good and bad luck, and sharp dealing must have all conspired to obscure the idea of

equiprobable outcomes�.

40 L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41

The upshot of both types of argument is, I think, complementary: examined in con-

text, the site at which we might think of figures such as Cardano being most likely to

put together modern probability might not have been so likely after all.

Acknowledgement

My thanks to Mario Biagioli, Lorraine Daston and Tony Grafton for their com-

ments on an earlier draft of this paper. I am also indebted to David Bellhouse for

several suggestions that have resulted in improvement.

References

Bellhouse, D. (n.d.). Decoding Cardano�s Liber de ludo aleae. Unpublished manuscript.

Bellhouse, D. (1993). The role of roguery in the history of probability. Statistical Science, 8, 410–420.

Caillois, R. (1962). Man, play and games (M. Barash, Trans.). London: Thames and Hudson.

Cardano, G. (1961). The book on games of chance (Liber de ludo aleae) (S. Gould, Trans.). New York:

Holt, Rinehart and Winston. (First completed ca. 1564).

Cardano, G. (1930). The book of my life (De vita propria liber) (J. Stoner, Trans.). New York: E.P. Dutton.

(First completed ca. 1575).

Cardano, G. (1663). Opus novum de proportionibus. In idem, Opera omnia (C. Sponi, Ed.) (10 vols.) (Vol.

IV, pp. 463–603). Leiden.

Cotton, C. (1674). The compleat gamester or, instructions how to play at billiards, trucks, bowls, and chess,

together with all manner of usual and most gentile games either on cards or dice, to which is added the arts

and mysteries of riding, racing, archery, and cock-fighting. London: Printed by A.M. for R. Cutler.

Daston, L. (1988). Classical probability in the Enlightenment. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

David, F. (1962). Games, gods and gambling: The origins and history of probability and statistical ideas from

the earliest times to the Newtonian era. New York: Hafner.

Gigerenzer, G., Swijtink, Z., Porter, T., Daston, L., Beatty, J., & Kruger, L. (1990). The empire of chance:

How probability changed science and everyday life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gliozzi, M. (1971). Girolamo Cardano. In C. C. Gillespie (Ed.). Dictionary of scientific biography (Vol.

III, pp. 64–67). New York: C. Scribner�s Sons.Hacking, I. (1990). Probability and determinism, 1650–1900. In R. Olby, G. Cantor, J. Christie, & M.

Hodge (Eds.), Companion to the history of modern science (pp. 690–701). London & New York:

Routledge.

Hargrave, C. (1966). A history of playing cards. New York: Dover.

Huizinga, J. (1949). Homo ludens: A study of the play element in culture. London: Routledge and Kegan

Paul.

Kendall, M. (1956). Studies in the history of probability and statistics, II. The beginnings of a probability

calculus. Biometrika, 43, 1–14.

Kolmogorov, A. (1933). Grundbegriffe der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung. Ergebnisse der Mathematik, 41,

269–292.

Leiseur, H. (1984). The chase: Career of the compulsive gambler. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Books.

Libri, G. (1840). Histoire des sciences mathematiques en Italie (4 vols.). Paris: Jules Renouard & Cie.

Margolis, H. (1993). Paradigms and barriers: How habits of mind govern scientific beliefs. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Montmort, P. Remond de (1713). Essay d�analyse sur les jeux de hazard (2nd ed.). Paris: Jacques Quillau.

Ore, Ø. (1953). Cardano: The gambling scholar. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Reith, G. (1999). The age of chance: Gambling in Western culture. London: Routledge.

L. Williams / Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 36 (2005) 23–41 41

Todhunter, I. (1865). A history of the mathematical theory of probability from the time of Pascal to that of

Laplace. London: Macmillan.

Sifakis, C. (1990). The encyclopedia of gambling. New York: Facts on File.

Siraisi, N. (1997). The clock and the mirror: Girolamo Cardano and Renaissance medicine. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.