CAN CHANGE SPORTS · her strip. The next day, again without any explanation, she was told to leave...

Transcript of CAN CHANGE SPORTS · her strip. The next day, again without any explanation, she was told to leave...

L10 COVERSATURDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 2014° WWW.LIVEMINT.COM

LOUNGE COVER L11SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 2014° WWW.LIVEMINT.COM

LOUNGE

Why should a natural, inherent condition prevent one of India’s most promising young sprinters from competing? It’s a question at the heart of a global debate on gender and sports

WHY DUTEE CHAND CAN CHANGE SPORTS

“Their sports career is the livelihood for their family. It is very hard to challenge this policy because it requires an interruption to one’s career, and the toll that can take is huge.”

Miles to go: (clockwise from above) Dutee Chand leading the field in the 100m at the Junior Asian Athletics Championship this year; SAI chief Jiji Thomson; Santhi Soundarajan, whose running career was derailed by a gender test; and Chand goes for an evening run at the railway training institute in Bhusaval.

ATHLETICS

B Y R U D R A N E I L S E N G U P T A & D H A M I N I R A T N A M····························

The sprinter Dutee Chandleads a quiet, disciplinedlife. It involves attending

classes for 9 hours at the ZonalRailway Training Institute inB h u s a v a l , a s m a l l t o w n i nMaharashtra almost 600km fromMumbai. At the institute’s large,leafy campus, Chand is one ofonly three women training to beticket-checkers. After classes,she heads back to her hostelroom and pores over studymaterial. She has pencillednotes—abbreviations and chap-ter headings—on the room wallsand on white charts; a desk witha laptop is within arm’s reach ofher bed. It is a life some distanceremoved from what she hasknown so far, a life revolvingaround intense sprint training,workouts and competitions.

It is even further removedfrom the storm now brewing—with her at its centre—that hasthe potential to change theworld of sports.

Though she has never com-

peted at the senior level, the 18-year-old Chand is well known. InJune, in a breakthrough in herfledgling career, she won two gold medals at the Asian Junior Athletics Championships in Tai-p e i , T a i w a n . B i g g e r s t a g e sawaited her—she was set to com-pete at the International Associa-tion of Athletics Federations(IAAF) World Junior Champion-ship in the US and her name wasunder consideration for the 2014Commonwealth Games (CWG)in Glasgow. But on 12 July, justahead of the world champion-ships and the CWG, Chand wassummoned by the doctor at theSports Authority of India (SAI)training centre in Bengaluru,where she was training. A seriesof tests were run, and three dayslater, she was told she would notbe able to compete. No reasonswere offered.

“My first thought was that Ihad been banned because Ifailed a dope test,” Chand says.“But I have never doped.” Con-fused and upset, Chand left for her home in Odisha. It was onlythere that she learnt, through

news channels, that she had failed a “gender test”. Chand wascompletely bewildered by thenews. It made no sense.

What she did have, and didnot know about, is a conditioncalled hyperandrogenism. Herbody produces a larger amountof the androgen hormone testo-sterone than the average woman.She was barred from competingbecause IAAF, the governingbody for world athletics, intro-duced a rule in 2011 which statesthat women who naturally pro-duce testosterone at levels usu-ally seen in men will be ineligibleto compete as women. The extrahormone gives them an unfairathletic advantage, IAAF’s rea-soning went. Just before the 2012Olympics in London, the Inter-national Olympic Committee(IOC) also adopted the rule.

Athletes who had hyperandro-genism had two options: Quitsports, or undergo a medicalintervention involving surgeryand long-term hormone-re-placement therapy to lowerandrogen levels.

Chand took the third option.

She decided to challenge theruling at the the Court of Arbi-t r a t i o n o f S p o r t s ( C A S ) i nLausanne, Switzerland.

“What I have is natural,” shesays. “I have not doped. I don’tdeserve the ban. This shouldnever happen to another girlagain.”

Multiple cases of hyperandro-genism have come to light sincethe ruling came into effect in2011, but no athlete has evertaken this step. These tests andtheir results are meant to be con-fidential, and athletes, fearing social shame and an end to theircareers, quietly accept secretivemedical intervention.

C h a n d ’ s a c t o f d e f i a n c ebrought together an interna-tional group of scientists, formerathletes and bioethicists, includ-ing Canadian Olympian andauthor Bruce Kidd, one of theworld’s leading activists forequality in sports, and medical anthropologist and author Kat-rina Karkazis from the Center forBiomedical Ethics at StanfordUniversity, US. Kidd and Karka-zis are part of an expert panel

who will testify for Chand. Jim Bunting, a lawyer who representsthe Sport Dispute ResolutionCentre of Canada, is working asChand’s legal counsel, pro bono.

“I marvel at Dutee’s courageand strength,” Karkazis wrote inan email.

By any reckoning, the oddswere stacked against Chand’sdecision to fight back. She is thethird of seven children born to apoor weaver family in Odisha’s Chaka Gopalpur village. She spent her early childhood in ahovel; her parents, both weavers,earned less than `3,000 a month.W h e n s h e w a s 4 , s h e w a sinspired by her elder sister Saras-wati’s running prowess, andwould run along with her on thebanks of the Brahmani river thatflowed past their village.

She watched as Saraswati’ssporting career—her elder sisterbecame a state-level athlete—transformed the economic for-tunes of her family. Saraswatieven got a job with the policethrough the sports quota. By thetime she was 10, Dutee was already impressive enough on a

track to win a scholarship to agovernment-run sports hostel inBhubaneswar. Then she beganwinning everything. In 2013, shebecame the first Indian to reachthe final of an international 100mevent (at the IAAF World YouthChampionships). She becamethe senior national champion in100m and 200m the same year.This May, two months before herban, she had broken the 14-year-old national junior record in100m by a large margin. Sportswas her key to a different life.

“The pressure on athletes toremain eligible is extraordinary,”Karkazis says. “Their sportscareer is the livelihood for theirfamily. It is very hard to chal-lenge this policy because itrequires an interruption to one’scareer, and the toll that can takeis huge.”

The challenge It was a breach of confidentialitythat set everything in motion.

On 16 July, the details ofChand’s test and her name weremade public by a newspaper.The leak could have had disas-trous results, but it also broughtthe case to the attention of Pay-oshni Mitra, a Kolkata-based researcher and activist in genderi s s u e s i n s p o r t s . M i t r a g o tChand’s number and called her.

“She was suspicious and con-fused,” Mitra says. “She wasremarkably stable when wespoke but she had no idea whatwas happening to her, and shesaid, ‘I don’t know why they aresaying I’m not a girl. Why arethey doing gender tests on me?’”

Mitra told her not to use theterm “gender test”, but by then SAI had released a statementconfirming that it had done a“gender test” on an athlete—itdid not name Chand. Mitra con-tacted SAI. She met the director

g e n e r a l , J i j iThomson, withw h o m s h e h a dworked earlier torehabilitate anotherathlete whose careerhad been destroyedb e c a u s e o f g e n d e rquestions—the middle-distance runner SanthiSoundarajan.

Soundarajan’s story islike an inventory of every-thing that can go wrongwhen an athlete’s most basicidentity is questioned. Shewas born into a desperatelypoor Dalit family in Kathaku-richi village in Tamil Nadu, andgrew up in a house without elec-tricity, running water, or a toilet.Her parents made a living work-ing in brick kilns, a professionrecently in the news for beingwidely regarded as being akin toslavery. Soundarajan’s athletictalent, though, was spotted early,when she was in school, and itchanged her life. By the time shewas 15, she was living in Chen-nai on scholarship and beinggroomed as an elite athlete. Tenyears and a handful of interna-tional medals and nationalrecords later, she finished sec-ond at the 2006 Asian Games inthe 800m. It was by far the big-gest win of her career—a glowingtribute to the overwhelmingodds she had sprinted throughto become an elite athlete. At theend of the race, Soundarajan,overcome with emotion and dis-belief, lay flat on her back on thetrack.

The triumph lasted less than24 hours. The morning after therace, Soundarajan was called bythe Athletics Federation of India( A F I ) d o c t o r , a n d m a d e t oundergo a test conducted by theOlympic Council of Asia (OCA)medical committee. The doctors

did not tell her what it was for,but they took blood, and madeher strip. The next day, againwithout any explanation, she was told to leave the Games. Afew days later, back in India,Soundarajan saw footage of herrace splashed across news chan-nels, with a report that said shehad failed a “gender test”.

Many of the reports suggestedthat Soundarajan was a man dis-guised as a woman who cheatedher way to a medal. The AFIcalled to tell her that she wasbarred from sports, and that herAsian Games medal had beentaken away. A few months later,Soundarajan drank a bottle ofveterinary poison in her village.She was saved by a friend whorushed her to hospital. ThenSoundarajan was forgotten.

In 2011, Mitra, who was work-ing in London, decided to inter-view her. In the course of theinterview Mitra learnt thatSoundarajan was never givenher medical report (a seriousbreach of protocol—such reportsare supposed to be handed overto the athlete first). Together,they filed a right to information(RTI) request for the report. Mitra made a documentary onSoundarajan to explain her con-dition. Soundarajan had femalegenitalia, but the chromosomalset-up of a man (XY instead ofXX). She produced more testo-s t e r o n e t h a n t h e a v e r a g ewoman, but she was also insen-sitive to the hormone, which raninertly through her. None ofthese conditions is uncom-mon—in fact they are far more common in elite sports than inaverage populations—and noneof them proves that Soundarajanis not a woman.

Mitra showed the documen-tary to sports officials in India,but got little response. In 2012,Soundarajan’s story got anotherjolt when it was reported in anewspaper that she was workingin a brick kiln. Suddenly, there

was a wave of sympathy andsupport. The Union ministryof youth affairs and sportsoffered her a job as a coach.

But questions about hergender continued to haunther—when she was givenadmission to the coachingcourse at SAI’s NationalI n s t i t u t e o f S p o r t s i nPatiala, administratorsdenied her a place, sayingthey could accommodateh e r n e i t h e r i n t h ewomen’s hostel nor inthe men’s hostel. Mitra

found herself up against awall—the then director

general of SAI even suggestedanother gender test to resolvethe issue. In early 2013, SAI got anew chief, Jiji Thomson, whotook an unusually sympatheticview of the case, and orderedthat NIS immediately take her inand put her in its guest houseinstead of the hostel.

Mitra was relieved, when shetook up Chand’s case, to findthat Thomson was still at the

helm. She raised the issue withhim, and Thomson took theunprecedented step of sendingout a carefully drafted state-ment saying that Chand’s gen-der was not in question, and shewas being tested only for hyper-androgenism.

“That statement had a biggereffect on the way the mediareported the story than anythingwe had done for Soundarajan,”Mitra says.

Thomson took the bold stepof making Mitra the officialm e d i a t o r f o r C h a n d , e v e nthough she had no affiliationwith SAI or the sports minis-try—“I knew my people werevery unprofessional in thingslike this, and I knew Payoshniwas the right person, so I askedher to take over,” he says.

She was sent to Chand’s vil-lage to meet her. Mitra andChand spoke on an overcast daysitting on the banks of the Brah-mani, the very place whereChand had discovered her pas-sion for running.

“She was still very cheerful,”Mitra says, “because that’s the

way she is, but her family andher older sister (Saraswati) werevery depressed. Dutee startedopening up to me. She hadmany questions about the test,about her own body, aboutandrogens.”

Neither Chand nor her familyreally understood what was hap-pening, and why anyone wouldsay their girl is not a girl. Othervillagers too stood behind her.They told her she had that“thing”—essence, not genitalia—that made her a girl.

Mitra and Chand travelled toNew Delhi, where they hunkereddown for a series of meetingswith sports officials. The optionswere laid out for her: Quit sportsor put yourself through medicalintervention.

“Dutee, Payoshni and I werelocked up in a room talkingabout what to do for a longtime,” Thomson says. “At somepoint, Dutee broke down. Thenwe ate lunch together, and whenwe resumed talking, Dutee said,straight away, ‘I don’t want sur-gery or hormone therapy.’”

“When I read that my condi-tion is treatable, I thought theymeant that I could take a medi-cine, like you take a painkiller,”Chand says. “But when I wastold that it would involve chang-ing my body in some way, Ididn’t want to.” Chand’s deci-sion provided the trigger for SAIto act.

Thomson immediately begannegotiations with the sports ministry to allow the challengeto be filed, listing carefully thepotentially high expenditure oftaking the case to CAS.

“I told my minister, no onehas ever challenged this before,this is absolutely unprece-dented,” Thomson says. Theword spread. Karkazis, Kidd,Bunting, all got involved. Mitraspent all her time on the phoneor writing mails.

On 27 September, a Saturday,Thomson and Mitra waited anx-iously for a go-ahead fromBunting to file the appeal withCAS. Chand had been officiallybarred on 29 August, and CASrules mandate that an appealmust be filed within a month ofthe ban. Time was running out.

“Then the call from Buntingcame through in the evening,”Thomson says. “I had stoppedmy officers from going home justfor this. We immediately startedthe process for filing the appeal.The almost 5-hour time differ-ence saved us. Those were tenselast moments.”

The stage was set.

What makes you a woman?Why women athletes need to betested for eligibility is perhaps the last explosive question left insports, and at its centre rightnow is the hyperandrogenismpolicy. Men and women bothproduce testosterone, but mentypically have more than 10times the amount in their body. The use of synthetic testoster-one has been clinically proven toboost muscle growth and explo-sive power, and aid recoveryfrom physical activity. Usingsynthetic testosterone is simplyseen as doping, and there isagreement in the scientific orsporting community that thisshould not be permitted.

Naturally produced testosterone,on the other hand, is a completely different ball game. It is neither an external, nor an artificial, aid. And even though it plays a central role in muscle growth, there is no con-sensus on the degree to which tes-tosterone produced by the body aids athletes.

“Testosterone is only oneingredient among many thataffect athletic performance,”Karkazis says, “and there is noscientific basis for claiming that itis either the singular or the most important dividing line betweenmen and women athletes.”

S t u d i e s h a v e s h o w n t h a twomen athletes with AndrogenInsensitivity Syndrome (AIS)—like Soundarajan, their bodiesproduce extra testosterone but

TURN TO PAGE L12®

ABHIJIT BHATLEKAR/MINT

IAN WALTON/GETTY IMAGES

RAMESH PATHANIA/MINT

COURTESY DUTEE CHAND

L12 COVERSATURDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 2014° WWW.LIVEMINT.COM

LOUNGE

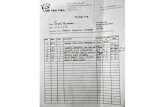

Not woman enough Gender testing in sports through the years

cannot use it—are highly over-represented in elite sports. In1996, a systematic chromosomescreening of female athletes atthe Atlanta Olympics found thatone out of every 423 athletes hadAIS—more than 200 times theestimated incidence in the gen-eral population. Some even hadCAIS—the “C” stands for “Com-plete”—which means their bod-ies could not use any testoster-one at all. More recently, duringthe 2011 IAAF World Champion-ships in Daegu, South Korea,another systematic blood testingprogramme found similar ratesof AIS in female athletes.

Martin Ritzen, emeritus pro-fessor at the Karolinska Institute,Sweden, and a former memberof the IOC Medical Commission,who helped shape the hyperan-drogenism rule, was one of theco-authors of a paper based onthe Daegu tests, and publishedin The Journal Of Clinical Endo-crinology And Metabolism inAugust. The paper states that“there is no clear scientific evi-dence proving that a high level ofT (testosterone) is a significantdeterminant of performance infemale sports…”

Ritzen did not respond toemails requesting an interviewfor this article. Arne Ljungqvist,IOC member and vice-presi-dent of the World Anti-DopingAgency, who was also part ofthe committee that worked onthe hyperandrogenism rule,declined an interview, sayinghe will “not comment on anongoing case”.

The principal logic behind thehyperandrogenism policy is thatmen and women produce dis-tinctly different levels of testo-sterone, and these levels areresponsible for the vast differ-ence in their performance. But alarge-scale, 2009 study on eliteathletes conducted by GH-2000,a project co-funded by the IOCa n d t h e E u r o p e a n U n i o nthrough the Growth HormoneResearch Society, found a signifi-cant overlap in testosterone val-ues in men and women. Around5% of the women tested in the“male range”, and 8% had levelsabove the “female range”. Evenmore tellingly, 25% of the men,including some Olympic medal-lists, were below the “malerange”, with a large number test-ing in the “female range”.

The difference in male andfemale athletic performance,especially in explosive eventslike sprints, is truly large. Thewinner of the 2012 OlympicWomen’s 100m sprint would not

® FROM PAGE L11

even qualify for the men’s event.But these differences are notexplained by testosterone alone.

“There is no stigma for menwho are strong and fast,” saysKarkazis. “There are no tests formen to weed out those who pro-duce more testosterone thanother men. Why not?”

The hyperandrogenism rule isunique in the sporting world forbeing the only policy that pro-hibits a natural phenomenon. Inevery other way, sports is anincredibly sophisticated andwell-funded machinery aimed atrecognizing and developing theinnate gifts of athletes.

Michael Phelps, the swimmerwho holds the record for themost number of Olympic goldmedals won by a single athlete,has a rare genetic disorder calledMarfan’s Syndrome, which ischaracterized by hyperflexibility,long limbs and long, thin fingers.The Finnish skier Eero Mänty-ranta, who won seven Olympicmedals in skiing in the 1960s,has a mutation in somethingcalled the EPOR gene, whichimproves the oxygen-carryingcapacity of a person’s blood by25-50%.

“Usain Bolt was born with verylong legs. He completes the100m race in 41 strides. Hisnearest competitor takes 45.Should we ban Bolt?” asks

had been secretly, and withouther knowledge, subjected to agender test. As she was runningthe race, the test was leaked tot h e p r e s s . W h e n s h e w o n ,Time.com ran a headline whichread, “Could this women’s worldchamp be a man?”

A s s h e w a s s u b j e c t e d t ointense and humiliating scrutiny,Semenya received overwhelmingsupport from her country. The South African government pur-sued the case aggressively withIAAF and the IOC, and it came tolight that IAAF’s gender policydid not have a single litmus testfor determining sex. Instead, itrelied on consensus, withoutdefining the criteria that must beused. Yet it could investigate anyathlete if anyone raised a ques-tion. Semenya was tested after ablog post called her a man(Chand too was tested after an anonymous complaint).

As in the case of Chand, peoplewere appalled at these revela-tions. In July 2010, IAAF clearedSemenya to run again, and beganto look yet again for a gender test.It came up with hyperandrogen-ism.

The fact remains that there isno single scientific marker thatseparates men from women, andthis is the stumbling block forsports’ governing bodies. AliceDreger, professor of clinical med-ical humanities and bioethics atthe Feinberg School of Medicine,Northwestern University in Chi-cago, said in a 2009 New Yorkerarticle on Semenya: “People always press me: ‘Isn’t there onemarker we can use?’ No. Wecouldn’t then and we can’t now,and science is making it more dif-ficult and not less, because it ends up showing us how much blending there is and how manynuances, and it becomes impos-sible to point to one thing, oreven a set of things, and say that’swhat it means to be male.”

Kidd advocates an elegantsolution to the problem: If you s a y y o u a r e a w o m a n , i t i senough. In the world of sports,where scrutiny is anyway intense,this suggestion is not as fanciful as it may seem at first. There hasnever been a confirmed case of aman pretending to be a woman at an international athletic event.

“It is a far-fetched idea, a ghostconcern that men will start com-peting as women,” Karkazis says.“People who suggest this are notthinking what it would mean fora man who does not feel himselfto be a woman to live his life inand out of sports as a woman.”

Under the knifeWhat might have happened ifChand had succumbed to medi-cal intervention to lower herandrogen levels?

A study based on the treatmentof four athletes who were foundto have hyperandrogenism at the2012 Olympics provides distress-ing testimony. The athletes werenot named in the study, which

was published in The Journal OfClinical Endocrinology And Metabolism in 2013, but weredescribed as 18-21 years of age,tall, slim, muscular, flat-chested,and “from rural mountainousregions of developing countries”.They had “excessive pubic hairand clitoromegaly (enlargedclitoris)” and hidden testes but“none of them reported malesex behaviour”. To make themfit for competing as women,they were taken to a hospital inFrance where their gonads wereremoved, even though the studysays, “...leaving male gonads inpatients carries no health risk,each athlete was informed thatgonadectomy would most likelydecrease their performancelevel but allow them to continueelite sport...”

Gonadectomy (the removal ofan ovary or testis) in womencauses loss of bone and musclestrength, and may lead to diabe-tes, chronic fatigue, depression,and poor libido. It necessitateslifelong hormone replacementtherapy. More chillingly, in thecase of the four athletes, the gonadectomy was followed by aseries of cosmetic surgeries thathad nothing to do with loweringandrogen levels: Their clitoriwere partially removed, a prac-tice that the medical communityrenounces, and they underwent“feminizing vaginoplasty”.

“When I read the paper, I wasabsolutely shocked,” Mitra says.“Why on earth would anyoneneed cliterodectomy? It seemed l i k e a p p e a r a n c e w a s m o r e important than anything else.Does this woman look like awoman? Does she have breasts?”

Can Dutee run?Chand is wearing a buttoned-down cream shirt and blackjeans, as she walks back to herinstitute from the Bhusaval rail-way station. She has returnedfrom a day-trip to a temple in anearby town. She has an easyand wide smile that she breaksinto quickly and often. She issmall—5ft-nothing—and tiesher hair in a severe ponytail.Waiting for her case to move for-ward, Chand has allowed hernails to grow, and painted thema dark pink. When she speaks, itis with a surety and softness thatbelies her age—she speaks fast,like she runs.

“I’ll leave sports but I will neverchange my body,” she says.

But then she adds: “My sisterwanted me to earn a medal forIndia in the Olympics and I haveto do that. I feel like there is aspeed breaker in my life now. Ijust have to overcome this and Ican go back to running.”

By the middle of next year,perhaps earlier, Chand will knowif she can do what she loves best.If she is allowed to run again, itwill be a victory worth more thanan Olympic medal.

Thomson. Just about every ath-lete at the elite level is a physi-cal outlier.

Karkazis suggests thatwhat is at stake here isnot a scientific problembut a social anxiety. In atelevised debate on Al-Jazeera on hyperandro-genism, Ritzen said womenwith hyperandrogenism have an“in-born” error. Hida Viloria, theUS-based chairperson of theOrganization Intersex Interna-tional, responded: “Fifty yearsago, Norman Cox, an Olympicofficial, said that about blackwomen who have a different physicality, that the IOC shouldcreate a special category of com-petition for them: the unfairlyadvantaged hermaphrodites.”

There is no reason to go back50 years. Last month, the head ofthe Russian Tennis Federationand IOC member Shamil Tarpis-chev referred to Serena Wil-liams, the women’s World No.1in tennis, and her sister Venus asthe “Williams brothers”, addingthat “it’s scary when you reallylook at them”.

“Policing women’s testoster-one exacerbates one of the ugli-est tendencies in women’s sportstoday: the name-calling andinsinuations that an athlete is‘too masculine’, or worse, thatshe is a man,” says Kidd.

“Policing women’s testosterone exacerbates one of the ugliest tendencies in women’s sports today: the namecalling and insinuations that an athlete is ‘too masculine’, or worse, that she is a man.”

Bad scienceIt is this very fear, that menmasquerading as women will

compete in women’s athleticsevents, that led to gender testingin the first place. It has a mud-dled and embarrassing history.While gender screening goesback to the 1936 Olympics, itbecame mandatory in 1966,partly in response to a Cold Warparanoia that East European countries were sending men dis-guised as women to win medals.All female athletes were requiredto drop their pants and have theirgenitals tested. Two years later,amid outrage over the humilia-tion of these “nude parades”, theIOC switched to a DNA test. It was simple—men have XY chro-mosomes and women have XX.Except when they don’t.

The scientific communitystood unified in opposition to theIOC, telling the sports body thatthere was just no way to dividemen and women neatly by look-ing at their chromosomes since all kinds of things can and do happen when parents’ DNAs arelining up to form the genetic combination for a baby. By 1990,chromosome testing had been dropped.

Yet the fear of “masculine”women never went away. CasterSemenya went through the sameordeal in 2009, when she wonthe 800m at the IAAF WorldChampionships in breathtakingfashion. A few weeks earlier, she

Polish runner Stanisława Walasiewicz accuses the US’

Helen Stephens of beinga man after losing toher in the 100m finalat the Berlin Olympics.Stephens undergoes anunspecified test and is

declared a woman.

1936

IAAF introduces standardized, onsite sex testing for all female athletes at the European Athletics Championships. The test involves an inspection of the genitals by a panel of three doctors. Athletes complain of humiliation and the method is discontinued two years later.

1966

1968Austrian skier Erika Schinegger is the first woman to be disqualified by the Barr body test.

1985

Spanish hurdler Maria MartinezPatino fails the Barrbody test at the WorldUniversity Games and istold to retire from sports

feigning injury. MartinezPatino, who had XY chro

mosome but also CAIS,begins a battle against theruling. Her records and medalsare taken away and she isbanned from sports.

1988IAAF drops chromosome testing and goes back to visual tests. MartinezPatino is reinstated.

1992IAAF drops all gender testing, since new doping regulations require athletes to pass urine in front of doctors. The IOC continues to test, introducing a genetic test which looks for a single gene called the sex determining region Y or SRY gene.

1996

Eight women fail the genetic test at the Atlanta Olympics, but are declared eligible to compete as women after further tests.

1999

The IOC drops mandatory sex tests, but reserves the right to test if “suspicions are aroused”.

Santhi Soundarajanfails the gender testafter the 2006 AsianGames. She loses hermedals.

2009

Caster Semenya fails the gender test. The South African government fights the verdict.

2010

Semenya is reinstated.

2011IAAF and IOC introduce the hyperandrogenism rule.

2006

IAAF introduces a rule requiring female athletes to carry medical certificates issued by their countries declaring that they are women.

1946

The IOC adopts the Barr body test—cheek swabs taken from athletes are tested for chromosomal setup: XX is women, XY, men.

1967

Outliers: (extreme left)

Serena Williamshas often faced

ridicule for beingmuscular; and South

Africa’s Caster Semenya, whose case

highlighted the problemswith gender testing in sports.

JULIAN FINNEY/GETTY IMAGES

MIKE HEWITT/GETTY IMAGES

JAMIE SQUIRE/GETTY IMAGES

WIKIMEDIACOMMONS

TOSHIFUMI KITAMURA/AFP

Stanisława Walasiewicz

Maria MartinezPatino

Santhi Soundarajan