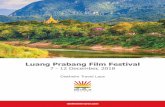

Cambridge Film Festival Review 2014 #4

description

Transcript of Cambridge Film Festival Review 2014 #4

follow www.takeonecff.com | @takeonecff | fb.com/takeonecff

Fracking Boom: THE OVERNIGHTERS

INSIDE

Director Rowan Joffe and novelist SJ Watson at the screening of BEFORE I GO TO SLEEP... COMING SOON! review and interview at takeonecff.com

Edd Elliott gets

FROZEN colouring competition

©DAVID RILEY

The scuzzy magnificence: OH BOY

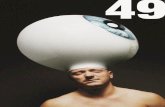

Oh BoyREVIEW

Reverting to its original title from the more accurate if neutral A COFFEE IN BERLIN, OH BOY is, on the face of it, a

shaggy dog story. Young slacker Niko (Tom Schilling) tries, and for the most part fails, to find a cup of coffee around town.

Not exactly a spoiler because this quest is soon swallowed up in the film’s deeper themes, at times coming to resemble a

yuppie nightmare similar to Scorsese’s AFTER HOURS.

Niko’s aimless lack of commitment and interest in the outside world and everyone around him is immediately apparent when

he leaves the comfort of his girlfriend’s flat, setting up in a gloomily empty apartment of his own. It’s paid for by his father, Walter’s

contribution to fees for the law studies Niko abandoned two years earlier. Discovering this, Walter closes the account which Niko

only realises when trying to use his cashcard to pay the extra euros for an exotic blend of coffee. The machine swallows the card.

He then tries to retrieve the odd change he’s dropped into a tramp’s cup, but is shamed after being spotted.

The narrative of OH BOY is built on such incidents and their unexpected consequences. Accompanied by an upbeat jazzy

score, Niko carries along through his day. The realisation dawns that the characters surrounding Niko are in a far worse mental

state than he; from the predatory shrink, who refuses to renew his driving licence after a minor drinking infraction, to Niko’s new

upstairs neighbour, a mine of too-much-information about his sex-life and his wife’s mastectomy.

The film’s centre-piece, which is both comical and unpredictably sinister, is Niko’s reunion with ‘Roly Poly Julia’, a girl he knew

at school who apparently overcame her weight issues and is now a performance artist in a grotesquely pretentious acting troupe.

The film seems dangerously close to straying into clichéd ranting-artist territory -- but what follows jolts Niko out of his apathy

and into action.

Niko becomes truly engaged after another fruitless coffee episode in a bar, when an ancient drunk suddenly opens up about

his memories of Kristallnacht in 1930s Berlin. The reality could hardly be in starker contrast to the film set Niko strays into - a

syrupy doomed romance between a sensitive SS Officer and a Jewish bookseller. OH BOY wears its historical references lightly,

but they are ever-present, like the graffiti disfiguring the urban landscape, pictured as we follow Niko on his journey from self-

absorption, to a sort of understanding in the film’s final images.

That OH BOY turns out to be a genuine crowd-pleaser (and multi award-winner after its release in Germany two years ago)

is a tribute to the charm of Tom Schilling’s performance in a difficult role. The clear vision of writer-director Jan Ole Gerster, who

juggles his themes with great self-confidence, delivering a glowing black-and-white portrait of modern-day Berlin in all its slightly

scuzzy magnificence is also to be applauded.

- Andrew Nickolds

The Overnighters

REVIEW

Jesse Moss’ documentary, which premiered at the Sundance

Film Festival this January, is a story about work, masculinity,

faith and the difficulty of doing good. The film is set against the

backdrop of the fracking-led oil boom in North Dakota, which

has attracted men from all over recession-hit America with the

promise of lucrative work. The small town of Williston has seen

a significant amount of these new arrivals.

The film focuses on Lutheran pastor Jay Reinke, who

responds to the influx by opening his church to transient

jobseekers who would otherwise be sleeping in their cars. In

addition to shelter, he offers help in finding employment and

tries to integrate them into the church services. We first see

him booking in a new arrival, laying down the rules in a no-

nonsense manner (“No weapons, no fighting, no profanity.

And don’t spill coffee on the carpet, it drives me crazy”).

The men come from as far as Los Angeles or New York,

though most are from the depressed South or Midwest.

Most see Williston as an opportunity to start over; some have

trouble with the law or addiction, others are simply escaping

from places with no work to be found. They tell their stories in

talking-head interviews to camera, combined with footage of

their daily routine and search for work.

These segments are interspersed with shots of the

landscape, with the picturesque rolling grasslands surrounding

Williston incongruously clashing with oil derricks and refineries.

The most surreal byproduct of this is a giant hole in the ground

constantly belching fire, which in a later sequence has been

covered over with a barn-sized steel box in a vain attempt at

camouflage.

Reinke walks a line between serving his regular

congregation, and attending to the needs of the new arrivals

out of his self-described Christian principles of hospitality and

compassion. At first he tries to defuse the tension between the

two groups with humour and understanding (“Did Jesus have

long hair?” asks a man staying in the church parking lot who

he’s asked to get a haircut. “Jesus didn’t have our neighbours”

the pastor shoots back).

The pastor is an obvious point of focus for the filmmakers;

he’s a fascinatingly quixotic character, stating his case to

camera with a mixture of folksiness and passion. His genuine

desire to do good often overrides other priorities; although

his family are broadly sympathetic, his dedication to the

“overnighters” ends up straining relations with them.

But as relations break down into open hostility, the pastor

finds himself betrayed by his own good intentions. Ultimately,

he finds that a few of the men have been dishonest with him

about their criminal records. While the facts of the cases are

disputed, the concealment puts Reinke at a disadvantage

dealing with the townsfolk and a scandal-hungry local press.

Moss offers a serious revelation late in the narrative which

provides a possible insight into Reinke’s motivations and why

he believes so strongly in the possibility of forgiveness and

second chances.

In the end, the film seems less about the titular overnighters

and more about Reinke himself. Just as they see the oil fields as

a fresh start, he wishes to make something new out of the men

who come to him. As the final shot of a refinery looming over a

pristine green field reminds us, some changes are irrevocable.

-Jim Moore

Capturing urban angst and the stress of middle age (divorce, bills and the dead end job) is a theme often covered in cinema. Loss remembered and then borne out in frustration, to be regained in moments of hope, often manifested in and by the love of others. The breakdown and the road to recovery are the meat and potatoes of many a story, but COWBOY BEN does not attempt redemption, and that is what makes the film work.

Directors Jon Shaikh and Scott Rawsthorne have to do a lot in only a little over seven minutes. Tony Burke’s script is tight enough to let you know quickly what is happening, which allows you to be aware of the rest of the room, of furtive glances here and there. It also releases the viewer to concentrate on the lead, Shaun Dooley, who is captivating. His opposite number (Ramon Tikaram, KAMA SUTRA) is no less enthralling as both bubble with pent up anger and unspoken frustration, although in the latter’s character it is totally understandable. The pumping music follows the pace of the drama perfectly. Building slowly to a skewed crescendo, a three note thumping beat acts like a leitmotif to Cowboy Ben’s emotions as he is taunted and cajoled in to the actions he ultimately takes - actions we know he has in truth already decided on.

Shanikh and Rawsthorne make a decent fist of a story that leaves the viewer less shocked than they should be; but the performances, pace and style of the film lift it above the ordinary. It is, however, the lack of compromise at the end that means the film stays with you, demanding your attention for longer than the slim running time of the piece itself. - Nick Kitchin

T1: What was your favorite thing about the film?D: [sucking thumb] The snowman and the reindeer.T1: What else did you like?D: [sucking thumb] The princess Anna and Elsa.T1: Did you like the songs, what was the best ..?D: [takes thumb out and sings:] Let it go, let it go ...

Take One’s newest critic, Daisy (aged 3 1/2) gives her conclusive assessment of Disney’s FROZEN’s characterisation and poetical lyricism.

Sing-a-long-a FrozenREVIEW

Cowboy

Ben

REVIEW The lovely Scott Rawsthorne, Tony Burke and Jon Shaikh

©DAVID RILEY

INTERVIEW

Edd Elliott: Ewan, NEKROMANTIK is a particular passion of yours. What has your and Arrow Films’ role in producing the DVD and Blu-ray been?

Ewan Cant: Our focus is very much on creating a deluxe package that caters to our fan’s high expectations, and ensuring that our releases contain a wealth of interesting and informative extras. Being a big fan of Buttgereit’s work, I was particularly adamant to include some of his short films on our release, and thankfully we’ve managed to make that happen. I’ve also been working on putting together some new special features for our release. In particular, over the past few months I’ve been laying the groundwork for what I hope will become an interesting piece concerning the legacy of NEKROMANTIK in the UK. A lot of that remains work in progress...

Alongside the extras, another highly important element in the creation of an Arrow Video release is our newly-commissioned artwork. For each and every title we put out we commission an artist to concoct their re-imaging of the film, to adorn the main cover of the release . We have some great artwork in the pipeline which I’m hoping will appeal to fans old and new...

EE: What lies ahead, and what do you hope will be the outcome of NEKROMANTIK’s screenings?

EC: I was always really keen to get NEKROMANTIK included as part of Scalarama - Scalarama being a festival which celebrates the spirit of the original Scala cinema, and NEKROMANTIK being a film which, in the UK at least, made its reputation through screenings at that venue, it makes perfect sense! We actually had Jörg over for a mini-UK “tour” recently, which kicked off at London’s FrightFest... Jörg was good enough to stick around for a lengthy Q&A afterwards and he gave the audience lots of great insights into the film. We followed up the FrightFest with another screening of NEKROMANTIK+ Q&A at the CCA in Glasgow, this time preceded by the short film HORROR HEAVEN. In terms of what lies ahead, more screenings throughout September as part of Scalarama, and then our Blu-ray/DVD release of NEKROMANTIK later in the year. With the screenings, I’m really just hoping that as many fans of the film as possible get to see it on the big-screen and, of course, hopefully we’ll pick up some more fans along the way.

EE: Finally, Jorg Buttgereit returns soon for his first film in almost 20 years, GERMAN ANGST. I guess you must be pretty excited.

EC: Very much so! GERMAN ANGST is actually an anthology film which brings together three directors – Jörg Buttgereit, of course, Michal Kosakowski and Andreas Marschall. I spoke to Jörg quite a bit about his segment, called FINAL GIRL, whilst he was over in the UK. He says that it harks back strongly to his early films – so NEKROMANTIK fans have a lot to look forward to, myself included!

Ewan Cant THE ARROW FILMS PRODUCER TALKS ABOUT THE NEW RELEASE OF

NEKROMANTIK

Screens at 18.00 Friday 5th Sep at St Philip’s Church with THE BOY WHO TURNED YELLOW!

REVIEW

Glitterball

If you stopped someone on the street and asked them to name the film in which a young boy encounters a stranded friendly alien, defends it from threatening adults and helps it return to its home world, chances are the answer they would give you is E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL. It is very unlikely, except perhaps if you are conducting your survey on the streets of Cambridge over the next few weeks, that the answer you would receive is THE GLITTERBALL. But five years prior to E.T., the British Children’s Film Foundation released a film that almost serves as a plot prototype of Spielberg’s sentimental classic.

The similarity does not stop there, though. The plot of THE GLITTERBALL was not unique in the Children’s Film Foundation output. It was in fact preceded by a number of other CFF films that pitted the innocent child against villainous adults, with the life of a lonely alien at stake. In SUPERSONIC SAUCER a group of school children protect an alien, Venus, from the nefarious intentions of a criminal gang. In THE MONSTER OF HIGHGATE PONDS another group of children befriends the eponymous monster. The same plot structure even underlies the popular CFF serial DANNY THE DRAGON.Founded in 1951 in response to concerns about the quality of the films post-war children were beginning to enthusiastically consume, the Children’s Film Foundation made children’s films from the 1950s to the 1980s that had an emphasis on ‘clean, healthy, intelligent adventure’. If you are thinking that sounds like the Famous Five on screen, you would not be wrong. The first adaptation of Enid Blyton’s work was in fact made by the CFF. Given the gender politics of Blyton’s work, it might also not be surprising to note that the only female character to appear in THE GLITTERBALL (other than a checkout girl) is a worthy housewife (Marjorie Yates) who tolerates the regular house moves of a forces family with good humour and industry. Her husband, Sergeant Fielding (Barry Jackson), heads up a RAF radar team. The key action, however, revolves around their son, Max (Ben Buxton) who discovers a small alien visitor with a big appetite.THE GLITTERBALL is deliberately non-rational science fiction – there is no attempt to explain where the alien puts all the food it consumes, or even how it consumes it. When Max insists that the alien is alive, Pete asks how can it be, ‘Where is its mouth?’. But the film is also a comic fantasy about boyhood in which children make instant friendships, have brilliant tree houses, get to hitch a lift on an ice-cream van and, Dukes of Hazzard-style, disembark by jumping out through its serving window. And they get to do all that, as well as knock over towers of cereal in supermarkets (who still doesn’t want to do that?) without repercussions and without interference from the adult world (apart from the essential baddy).It remains to be seen what an audience of contemporary children will make of THE GLITTERBALL. It may appeal more to the generation that grew up in the late 70s and early 80s who remember swiss rolls and lumpy custard with nostalgia. Its pre-CGI special effects and chase scenes featuring bicycles and ice-cream vans will no doubt appear clunky and slow compared to today’s slick science fictional cinematic output. But there is a sense in which the film already knows it is out of date – and that deliberate humour makes it both highly entertaining and enduringly loveable. - Sarah Dillon

REVIEW

Fiction

©TAKE ONE 2014Editor/Design: Rosy Hunt

Managing Editor: Jim Ross

Deputy Editor: Edd Elliott

Writer-director Cesc Gay specialises in explorations of male friendships and the existential crises of men questioning their life decisions. In FICTION (2006), Álex (Eduard Fernández) - a writer-director - has temporarily left his wife and children in Barcelona and gone to stay with his friend Santi (Javier Cámara) in the countryside, in order to write in peace and quiet. Not much happens in FICTION but the film quietly emphasises that the important things in life often occur in fleeting moments that can pass us by if we are not careful.

Over dinner with Santi, mutual friend Judit (Carme Pla), and her visitor Mónica (Montse Germán), Álex explains that his new script takes place over the course of one day, with a series of conversations between a group of friends discussing their crises (e.g. reaching an age where you question who you are, not who you wanted to be, and accepting the decisions that you’ve made). Besides sounding like the basis for Gay’s most recent film, A GUN IN EACH HAND (2013), the dinnertime conversation is one of several scenes in FICTION to highlight the inspiration art takes from life: Álex works through his personal problems in his writing, but is also an apparent onscreen proxy for Cesc Gay.Little-known outside of Spain, Eduard Fernández is an actor who can say more by gazing into the middle distance than many can muster with a full-blown monologue. A wordless yet eloquent example of Fernández’s emotional subtlety is the almost invisible change in his expression when Álex has a moment of self-realisation while listening to Mónica playing the piano. As with the sequences where Álex listens to the radio alone in Santi’s house, we see him immerse himself in the music, but as Fernández’s face relaxes we observe a thought emerge and bloom in Álex’s consciousness, conveyed with the barest flicker of his eyes and a twitch of his mouth.Despite its writer protagonist, FICTION relies more on glances than words. We witness Álex and Mónica fall in love during the few days they spend in each other’s company, but neither is inclined to verbalise their desire or act on it, and a series of hesitations and half-caught glances play out in front of us. In a bar scene late in the film, the sense of what is being left unsaid is palpable and clearly evident to them both: the careful body language of Fernández and Germán captures the tension of being simultaneously comfortable and awkward in the company of someone you’re falling for. Álex and Mónica stand side-by-side but facing opposite directions - the need for physical closeness being counteracted by denial - while their suddenly stilted conversation still occasionally hits a seam of unselfconscious common ground, and the sparks fly once more.A film where nothing (and yet everything) happens, with FICTION Cesc Gay made a grown up film about grown ups, and one that is intensely - and authentically - romantic. - Rebecca Naughten

FICTION screens on 6 September at 14.30 at the Cambridge Film Festival.