Buy Now! Ghost Division: Home - World at...

Transcript of Buy Now! Ghost Division: Home - World at...

6 WORLD at WAR 38 | OCT–NOV 2014 WORLD at WAR 38 | OCT–NOV 2014 7

Ghost Division:Erwin Rommel & German Mobile Warfare in 1940

By Joseph Miranda

offi cers, that another European war was inevitable. In it the German Army would need to employ advanced tech-nologies and innovative tactics to win the decisive victory that had eluded it in 1914-18. The overall concept was the army would be composed of two types of formations: a large mass of infantry divisions providing a base for maneu-ver and the ability to hold the front, along with a smaller number of elite mobile divisions that would maneuver to set up and then win battles of encirclement and annihilation.

Von Seeckt had many followers. Heinz Guderian, a rising young offi cer, advocated for a large force of tanks. Those vehicles could provide both the maneuver capability and the fi repower needed to execute mobile doctrine.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, he supported many of the new military concepts. He became

Mobile Warfare

T he origins of World War II German mobile warfare go back to the “Black

Reichswehr,” the clandestine part of the armed forces created during the post-World War I Weimar Republic. The victorious Allies had placed limitations on the size of the German armed forc-es, as well as banning the re-institution of the general staff and the deployment of tanks and military aircraft. That didn’t long deter the Germans.

Gen. Hans von Seeckt, Reichswehrcommander from 1919 to 1926, began a covert rearmament program. Within it, he encouraged new ideas and supported the rising generation of leaders. Among other things, he promoted combined arms warfare, a regimen of tough training, and better offi cer-enlisted relations.

There was yet another dimension. Von Seeckt believed, as did many other

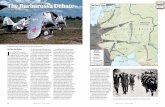

This photo shows Gen. Hans von Seekt and his staff shortly after the founding of the Reichswehr in 1919. Von Seekt is the mustachioed offi cer standing in front just to the left of center with his hands behind his back. It was these men who developed the modern-day concept of mobile warfare.

an advocate of armored and aerial warfare, as tanks and planes seemed to provide the answer to the trench deadlock he’d experienced as an infantryman in World War I. The emphasis on advanced weap-onry, motorization and aircraft, also appealed to the futurist orientation of National Socialist propaganda.

The 1930s saw debates about the mission of tank forces in Germany, as well as in other major powers’ armed forces. Traditional offi cers saw tanks as useful for infantry support, or in acting as mechanized cavalry by scouting, screening and pursuing. Guderian and his group advocated tanks be concentrated into divisions that would fi ght as an elite strike force.

Tactically the tanks were to operate similar to the Stosstruppen (infantry shock troops) of World War I, albeit faster and with more fi repower. They

would break through the front and drive deep, maneuvering the enemy out of position. That still wasn’t all: the critical aspect was the operational level. There the panzers would move cross-country to envelop entire opposing armies and destroy them in decisive battles of annihilation.

Field exercises soon showed tanks alone couldn’t gain that kind of decision. They needed to be supported by artillery (to suppress

enemy anti-tank weapons), infantry (to hold ground seized), anti-tank guns (to defend against enemy armor counterattacking), engineers (for crossing rivers and clearing obstacles), and motorized logistics (to maintain the pace of operations).

By the late 1930s, then, German panzer (armored) divisions had evolved to be organized as true com-bined arms formations. Indeed, the number of tanks in a panzer division

(over 300) was only a fraction of the unit’s total motor vehicle allotment, which also included a grand total of some 2,000 trucks, tractors and motor-cycles. The 1939 organization had one panzer brigade of two tank regiments, a Schutzen (rifl e) brigade of one motorized infantry regiment and one motorcycle battalion, an artillery regi-ment, anti-tank, pioneer (combat engi-neer) and reconnaissance battalions, plus motorized divisional services.

Buy Now!

Home

8 WORLD at WAR 38 | OCT–NOV 2014 WORLD at WAR 38 | OCT–NOV 2014 9

Rommel accepting the surrender of the British 51st Highland Division at St. Valery on 12 June.

a high-velocity 37mm gun that was useful against enemy armor and could also fi re high explosive rounds. The Panzer IV was intended for heavy close-in support, and was therefore armed with a short barrel 75mm. The Panzer I and Panzer II were by then essentially relegated to nothing more than training vehicles, the former armed with machineguns and the latter with a 20mm automatic cannon.

To fi ll out the inventory for the 1940 campaign, the Germans used Czech LT-35 and LT-38 (light) tanks that they’d taken over following the annexation of Czechoslovakia. Both models were serviceable vehicles, armed with an effi cient 37mm gun and capable of acting in the medium tank role, at least in the opening two years of the war. Nonetheless, the situation demonstrat-ed the overarching need for continued improvisation: German industry had yet to meet the panzer arm’s needs.

Allied Strategy

The winter of 1939-40 was quiet on the western front, with the entire period being dubbed by newspaper-men and bored soldiers the “Phony War” and “Sitzkrieg,” the latter a play on blitzkrieg or “Lighting War,” the popular term for German mobile warfare. (The Germans themselves didn’t originate the use of the term “blitzkrieg”; they used Bewegungskrieg, meaning “maneuver warfare.”)

While both sides spent their time training and preparing for the next round of fi ghting, Allied planners had to contend with the stunning

German victory in Poland. There, in only a few weeks, the Wehrmacht had overrun the entire country, demonstrating the effi cacy of their mobile war concept. The debate over the mission of tanks was in that way resolved in favor of mobile war.

The Polish campaign also showed the importance of airpower. With its control of the air, the Luftwaffe directly supported German forces and also attacked Polish command centers, logistics and cities. The bombing of Warsaw, which involved up to several

Rommel & the Ghost Division

Erwin Rommel joined the German Army in 1910 and fought as an infantry offi cer in World War I with considerable distinction, being promoted to captain and decorated with Germany’s highest honors, notably for actions during the 1917 Caporetto offensive. He afterward wrote a book on tactics based on those experiences and titled Infanterie Greift An (Infantry Attacks).

He emphasized up-front battlefi eld leadership, troop mobility and shock effect. The book gained him attention, including that of Hitler, resulting in his being made commander of the dictator’s headquarters detachment at the time of the Polish campaign, a prestigious assign-ment. For 1940 he requested command of a panzer division, and in that way he got 7th Panzer.

The 7th Panzer Division had then only recently been created by being reorganized from the 2nd Light Division, and for the coming campaign it was assigned to Hoth’s XV Motorized Corps, part of von Kluge’s Fourth Army. As the campaign opened, Rommel led 7th Panzer through the Ardennes and into France. He was usually up front, often taking personal command in tactical actions but never losing sight of the bigger objective—driving to the English Channel.

Throughout the campaign Rommel emphasized speed and shock, defeating various Allied formations while still on the move as they appeared piecemeal to his front. The panzer divisions’ combined arms structure facilitated those tactics. A point Rommel made repeatedly in his account of the campaign was that concentration of fi repower, especially when supported by aerial attack, would often panic enemy troops and thus turn a seemingly desperate situation into an opportunity for further exploitation by the tanks. He also viewed as critical engineers for clearing obstacles, crossing rivers and overcoming fortifi ed positions.

That didn’t mean the Allies were incapable of effective resistance. For instance, a crisis occurred at Arras on 21 May when a British armored force counterattacked 7th Panzer. Rommel reacted quickly, though, bringing up divisional artillery and anti-aircraft guns that soon destroyed or disabled the attacking British tanks. The 7th

was then reinforced with tanks from 5th Panzer Division, and drove farther north. On 29 May, Rommel received an order to prepare for a new

offensive to the south and west. In that operation he swept along the Channel coast, taking many prisoners and capturing Le Havre.

Throughout all that, 7th Panzer became known as the “Ghost Division” because its rapid movements made it diffi cult for the Allies, and sometimes the German high command, to fi gure out where it was and where it was going. ★

Typical Panzer Division Tank Inventories, May 1940

Unit Panzer Is Panzer IIs Panzer IIIs Panzer IVs Panzer 38 (Czech)

Command tanks

1st Panzer Division

52 98 58 40 - 8

5th Panzer Division

97 120 52 32 - 26

7th Panzer Division

34 68 - 24 91 8

Note: In comparison, in the 1939 Polish campaign a panzer division typically had 120 Panzer Is, 155 Panzer IIs, six Panzer IIIs, and 18 Panzer IVs.

War

World War II in Europe broke out on 1 September 1939, when Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland. The ensuing campaign showed the panzer concept was essentially sound, but those units still needed shaking out. The panzer divisions had too many tanks, making their sub-formations diffi cult to control in the fi eld. There were also too many light tanks (Panzer Is and IIs) and not enough mediums and heavies (Panzer IIIs and IVs).

The number of tanks per regi-ment was cut back, with the surplus reorganized to form more panzer divisions, usually by also reorganizing the (too) light divisions. The motorized infantry divisions proved too unwieldy, so they each lost an infantry regiment, which for the remainder of the war became the standard pattern for them.

Within the panzer arm, the main shortfall was an overall lack of tanks. The two modern types were the Panzer III and IV. The Panzer III had

had a tank battalion plus four motor-ized infantry battalions. Rounding out the mechanized force were motorized infantry divisions, essentially standard infantry divisions but moved by trucks.

The Wehrmacht (as the German armed forces offi cially became known in 1935) also organized several Leichte (light) divisions, intended to act as a kind of mechanized cavalry. They each

The divisional insignia of 7th Panzer Division in 1940. It has no heraldic signifi cance; rather it was merely a quickly identifi able icon to aid German military police and logistics offi cers in identifying units in the fi eld.

10 WORLD at WAR 38 | OCT–NOV 2014 WORLD at WAR 38 | OCT–NOV 2014 11

offensive in the west. They expected them to use some variant of the 1914 Schlieffen Plan, but enhanced by mobile divisions and airpower. Thus their main thrust was anticipated to be through northeastern Belgium (as in World War I) and possibly

hundred planes in each raid, also appeared to vindicate the interwar theories of airpower that held attacks on cities could destroy enemy morale.

The question for French and British planners, then, was centered on where the Germans would concentrate their

spearheads. Essentially, Plan D called for a strategic offensive to be followed by a tactical defensive.

Plan D wasn’t particularly inspired, but it suited the Allied perception of the overall situation. Essentially, it narrowed the active front to a limited sector where the French and British could maintain a local parity in tanks. It also provided the benefi t of fi ghting alongside the Belgians, adding their divisions to the order of battle.

Plan D left one opening, and that was in the Ardennes, the region of forests and hills in southern Belgium and Luxembourg. The French high command dismissed the area as impassible to tanks. In retrospect that seems an amazing underestimation of the potential threat on that front, but there was some justifi cation for that evaluation at the time.

One reason for that went back to Belgium’s neutrality. The Belgian military refused to coordinate with the Allies for fear it would provoke Germany into belligerency. From the perspective of simple military effi cien-cy, then, once the Germans did bring Belgium into the war, the Anglo-French counter-move would have to be along the most effi cient axes of advance. They were in central and northern Belgium, where there was an extensive road network as well as relatively open terrain over which large numbers of tanks could be deployed. Moving Allied divisions in via the Ardennes could easily bog down and miss the expected main German drive in the north.

As it was, Belgium was supposed to secure the Ardennes. Its army actually had a dedicated force for that mission, the Chasseurs Ardennes, trained to operate specifi cally along that front.

Manstein’s Plan

When France and Britain declared war on Germany, the latter’s armed forces high command (OKW or Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) had to come up with a plan to fi ght in the west. It was codenamed Fall Gelb (Operation Yellow), and the original concept was indeed based unimagi-natively on the 1914 Schlieffen Plan.

That plan, which had been formulated by Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and refi ned by Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke (“the Younger”) in the years before World War I, called for an invasion of Belgium, primarily

also the Netherlands, as that was where the best tank country lay. While both of those countries were neutral when the war opened, Germany had shown no hesitation in violating borders in 1914 and there was no reason to think Hitler would respect neutrality in the new war.

Even so, the situation held some promise for the Allies. If the Germans didn’t go through Belgium, they would have to make their offensive into Alsace-Lorraine, west of the Rhine. German attacks there could be shattered against the extensive lines of French fortifi cations. If the Germans did break though, they would be met by counterattacks from Allied mobile forces held in reserve and deploying considerable numbers of tanks.

If the Germans invaded Belgium, the French and British were prepared to go into that country. Several operational plans were developed, and the one fi nally settled on was called “Plan D” for the Dyle River, a small watercourse in central Belgium. Allied mobile forces would drive to that line and there await the German

by advancing across the open terrain of the northern portion of that country and then going along the Channel coast to outfl ank the French armies deployed farther south. The ultimate objective was to fi ght a grand battle of annihilation somewhere in north-eastern France (exactly where remains a matter of historical debate) on terms favoring the Germans, thereby winning the war in one campaign.

Of course, the plan failed in 1914. German logistics couldn’t support so rapid an advance and that, in combination with the friction of Allied countermoves, caused

Schlieffen’s timetable to break down. Years of trench warfare followed.

For 1940 the OKW therefore initially decided on a less grandiose objective: they would again push through Belgium, but only far enough to seize the industrial regions of northeastern France and then stop. The fi nal operational objective was the Somme River. Britain would then be kept off-balance by a combined aero-naval siege based on the newly acquired forward bases along the Channel coast. The war was expected to end in some kind of negotiated settlement.

continued on page 14 »

The motorcycle reconnaissance unit quickly took the lead.

A scene from the start of the British counterattack at Arras.

The Panzer I: despite the fact it was already obsolescent, it was one of the two mainstay tank models in the German armored divisions in 1940.

Buy Now! Schlieffen’s timetable to break down.

For 1940 the OKW therefore initially

Schlieffen’s timetable to break down. Home