Body Bugs NOVA | Bugs That Live on You NOVA | Bugs That Live on You.

Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

-

Upload

chelsea-green-publishing -

Category

Documents

-

view

225 -

download

0

Transcript of Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

1/10

Tree Fruits and Berries the Biological Way

The Holistic Orchard

M I C H A E L P H I L L I P S

B Y T H E A U T H O R O F T H E A P P L E G R O W E R

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

2/10

orch ar d dyna mics 115

limits upon. You too will have ideas that make inher-

ent sense for your trees and the localized dynamics

you face. Take what we understand as of this moment

and dont be afraid to tweak it.

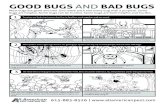

BUGS AND MORE BUGS

Learning to identify whos who and then zeroing in

on the when and where of pest vulnerability (based

on family groupings) defines the crux of the matter

when it comes to bugs in the orchard. There are some

helpful ones and a few deservedly notorious ones,

but most species are in truth absolutely innocent.

Detailed specifics about the chosen few at your site

will be found in the applicable fruit sections and in

tree fruit guides listed in the resources. Our imme-

diate goal is to understand how to balance potential

pest situations.

Insect consciousness begins with paying attention.

Seeing early signs of chewing on the edges of a bud

or a light-deflecting pinprick (indicative of a feeding

sting or an inserted egg) on developing fruit should

put you on alert. Probing for details beyond this first

impression leads to finding a tiny caterpillar curled

within the sepal leaves at the base of a flower bud orlooking for suspected culprits when cool morning dew

finds curculios sluggish but not yet in hiding. One

grower in Nebraska could not figure what was eating

the leaves on his cherry trees . . . until he went out

at night with a flashlight and found that june bugs

had come up from the ground to feed with abandon.

Different things will happen in different places

whats constant is the need to discern whats actually

going on so you can then take intelligent measures to

achieve a happy resolution.Insect injury to fruit offers an important learning

opportunity. The ability to distinguish one fruit scar

from another more often than not reveals whos actu-

ally behind the deed. Consulting with an experienced

grower or Extension adviser, looking at regional pest

guides, and perusing the words in this book are all

tools for getting your detective credentials in order.

Knowing the name of the guilty partyif indeed the

damage is significant and thus calls for specific action

in the next growing seasonleads to learning about

the life cycle of a particular pest. This in turn reveals

points of vulnerability where trapping, repelling,certain beneficial allies, and specific spray strategies

have relevance.

But first lets do the numbers. You need perspec-

tive to know the difference between tolerable damage

and a pest situation rapidly ratcheting out of control.

Research that tracked the damage done in wild apple

trees in Massachusetts over a twenty-year period gives

a fairly accurate picture of whats out there. Plum

curculio and apple maggot fly can afflict as much as

90 percent of the fruit in a bad year, with codlingmoth and one of its close cousins getting digs into

about half of these yet again. Additional damage from

all other fruit-feeding pests tallies below 10 percent

. . . not something to get concerned about by any

means. Overmanaging this situation to have all fruit

left untouched will have far too great an impact on

A russeted, fan-shaped scar speaks to the presence of plum curculio in theorchard. The female makes a crescent cut above each inserted egg as a means

of preventing fruit cells from crushing her reproductive artistry. Seeing scars on

maturing fruit indicates that the apple won the race. Photo courtesy of NYSAES.

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

3/10

116 th e holis tic orch ar d

beneficial populations and thereby induce additional

pest challenges. Its not worth the expense or crazi-

ness of doing this. Determine your must-do priorities

around those significant pests and grant that a small

portion of the crop belongs to the natural world. The

concept of balance works both ways.

S P O T L I G H T O N T H E J A P A N E S E B E E T L E

Prepare to be dismayed when this insect hits your

fruit plantings. Lets unveil the thinking process

required to cut to the quick with Japanese beetle.

Story line

Larvae of Popillia japonica came to this conti-

nent with a shipment of iris bulbs from Japan

sometime before 1912, when commodities enter-

ing this country started being inspected. In its

native land, this beetle was much less of a pest

than it was to become here. Hold that thought.

The combination of well-watered turf for larval

development, warm summer temperatures, and

the lack of a specific natural enemy has favored

the buildup of beetle populations.

The life cycle of any insect reveals certain

points of vulnerability to an inquiring mind.

Japanese beetle spends the greater portion of the

year in the soil: The female burrows into moist

soil to lay her eggs 24 inches deep. Larval grubs

hatch out to feed on grass roots, eventually going

into pupation before emerging as next years

hungry adults by midsummer. The first emerging

beetles seek out suitable food plants and initi-

ate the feeding frenzy. These early arrivals will

release a congregation pheromone (odor) that is

attractive to other adults, essentially calling the

whole horde to come dine . . . on your trees and

berries!

Preferences

Japanese beetles have definite favorites in the

green world. The leaves of grape, raspberry,

juneberry, autumn olive, rose, and (surprise,

surprise) the Honeycrisp apple especially appeal.

Red clover, zinnia, common primrose, and string

beans can be surefire diversions as well.

Soil pupation

An insect species committed to a long spell in the

soil risks being undone by certain biological strat-

egies. Milky spore is a native bacterium (Bacillus

popilliae) that can be applied as a onetime soil

drench to infect grubs for many years to come.

Parasitic nematodes (Heterorhabditisspp.) can be

watered in beneath especially attractive plantings

in early fall to consume all comers. But in truth?

Everyone in the neighborhood needs to employ

one or the other for guaranteed effect.

Beneficials

Recall how Japanese beetle was held in check in

its homeland? Parasitic wasps and tachinid flies

were at work. The winsome fly has been brought

here from the Far East because of a desire to attach

its eggs to the thorax of adult beetles. Things get

rather gruesome after that. Spring tiphiid wasps

(Tiphia vernalis) specifically hunt for Japanese

beetle grubs, lured by scent alone to tunnel into

the soil to lay a single egg on the beetles larval

membrane. Each female wasp parasitizes one or

two grubs daily in this manner and can lay a totalof between forty and seventy eggs over her life

span of thirty to forty days. You encourage the

right tiphiid species by providing adult habitat

like forsythia, peonies, and tulip poplar.

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

4/10

orch ar d dyna mics 117

Who, what, and when

Every insect goes through a molting cycle that starts

from the egg. The larval and pupal stages subsequently

lead on to adulthood and the reproductive urge.

Damage to fruit trees is to either the foliage or the

fruit itself. Some of this consists of adult feeding, but

Hands-on solutions

One long-standing remedy is unabashedly gross:

Take a few handfuls of gathered beetles, macerate,

and then spray onto plants you wish to protect.

Interestingly, this may work as more than just

a repellent due to an entomopathogenic fungus

in some of those captured beetles now being

sporulated into the environment. But lets face

it: The most straightforward solution to burgeon-

ing beetle numbers is a daily scouring of valued

plants. Persistently knocking these invaders into

a bucket of soapy water morning after morning

eventually has to make headway. Pheromone

funnel traps wont accomplish as much as vigi-

lance. A mixture of the aggregation and sex pher-

omones draws 90 percent of the beetles within

sensory range of the trap, but usually catches only

6075 percent. But hey! What a nice gift to give

the neighbors, eh? Again, an area-wide approachis the ticket to success. Then theres this perma-

culture nugget: You dont have a beetle problem, you

have a duck deficiency. Folks with roaming poultry

have yet another ally in the orchard.

Sprays

Surround WP kaolin clay spray works by clog-

ging adult beetles with a coating of refined kaolin

clay picked up when crawling across leaf surfaces.

This can be used to protect fruits that are easily

washed (like that Honeycrisp apple) but will turn

berries into a white mess. Pure neem oil gets my

highest recommendation as a feeding deterrent

by causing a vomiting sensation in the feeding

adult. Of course, neem works best applied as

a preventive prior to the beetles arriving. Last

resort lies with PyGanic sprayed on trap plants

chosen from the beetles known preferences.

Powerful toxinseven organic onesshould not

be applied ecosystemwide.

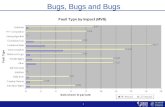

The life cycle ofany pestsuch as

Japanese beetle,shown hererevealscertain points of

vulnerability to the

astute orchardist. Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec.

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

5/10

118 th e holis tic orch ar d

more often than not its the egg hatching out a very

hungry caterpillar or grub. Lets look at family group-

ings within the insect world relevant to orcharding

as a quick means of getting a handle on potential

pest situations. The goal here is not so much ento-

mological precision as identifying similar patterns to

discern possible responses to a pest dynamic deemed

unacceptable.

Every fruit grower will experience the orchard

moth complexin some form or another. This ubiqui-

tous force can involve dozens of species, but it alwaysmeans tiny caterpillars munching away on some part

of the tree. Internal-feeding larvae go for the seeds

in developing fruit, often risking a mere twenty-four

hours of vulnerable leaf exposure before getting safely

tucked away inside. Look for a small hole in the side

of the fruit and often in the calyx end from which

orange-brown frass (poop) protrudes. Surface-feeding

larvae are content to nibble upon the skin of the fruit,

hiding beneath an overarching leaf or where two fruit

touch. Many of these are second-generation leafroller

species, which in the spring larval phase were intent

on feeding on buds and unfurling leaf tissue. Any

resulting fruit damage at this early stage often appears

as corky indentations.

Lets key in on this generational concept, for

therein lies both the amplification of the moth prob-

lem and the timing of extremely targeted solutions.A given species overwinters as a hard-to-find egg

mass, perhaps as larvae (in a dormant state known

as diapause), some in a pupal cocoon, and some even

as adult moths where mild winters allow for feeding

and procreation. Location specifics vary as well, but

mostly orchard moths favor laying eggs on leaves and

Not all players in the orchard are necessarily known . . . but without a doubt this twig looper belongs in the orchard moth complex, which includes dozens of species.

Photo by Mark Rawlings.

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

6/10

orch ar d dyna mics 119

twigs where larvae can subsequently feed. These go

on to find some secluded place to pupate: in crevices

in the bark, litter on the orchard floor, or sheltered

nooks provided by a nearby fence or wall. One way

or another, with adult emergence in spring dependent

on the development stages still to be achieved, first

flight takes place when females get impregnated and

then proceed to lay eggs on the new seasons growth.

That hatch initiates what is considered to be the first

generation of the orchard yearlimit this genera-

tion and all subsequent generations will be fewer in

number. Some species are content with a single round

of action, whereas others will achieve as many as five

or six generations of egg laying and larval feeding in

the extended growing season of warmer climes. The

vulnerability points with moths lie in adult attraction

around the times of feeding and mating, the need for

eggs to respire, larval ingestion and/or contact withbiological toxins, and exposing pupae hiding on the

tree trunk for physical destruction.

Fruit-oriented flies affect chosen fruits across

the spectrum. Fly larvae are called maggots, which

I expect reveals the gruesome scene about to be

revealed.17The female adult lays her eggs directly into

the yielding flesh of ripening fruit, with specific prefer-

ence by maggot fly species for apple, cherry, blueberry,

and so forth. All such fruit becomes a maggoty mess

of meandering tunnels and decay. Feeding attractants

are used to manipulate adult flies to a deadly mealinstead, along with sticky sphere traps that promise

the perfect nursery for junior on which to lay an egg.

Soil pupation suggests additional vulnerability points.

Pick up early drops biweekly to prevent larvae from

ever getting into the ground. Spraying the ground

beneath badly infested trees with Beauveria bassiana

in fall can help reestablish a clean starting gate: These

parasitic fungi consume the fly pupae waiting in the

soil for next season. Even more deliberately, plant a

Dolgo crab tree to draw apple maggot flies in droves

. . . use this as a trap tree to protect other apples, and

then apply beneficial nematodes in early fall (the

Steinernema feltiaespecies is recommended for AMF)

to seek out the pupae in the ground below.

Sawflies are a different category of critter alto-

gether. Wasp aspects seem to have been incorporated

with fly-like behavior in this insect, resulting in a

pollinator that in its larval form just happens to bore

into developing fruit or strip gooseberry branches of

all greenery. Pear slugs (aka pear sawflies) look pretty

much like fleshy blobs designed to skeletonize leaves.The vulnerability points here lie with sticky card

traps, desiccants like insecticidal soap and diatoma-

ceous earth, and knowing precisely when a certain

biological toxin will come in contact with apple sawfly

larvae moving from a first fruitlet to the next.

The thing about hard-backed beetles is that the

majority of these species pupate in the soil. (Those

that opt for wood tissue will get a separate designa-

tion.) Most infamous of all are the curculios, which

decimate most any tree fruit in the eastern half ofNorth America.18 Repellents form the backbone of

an organic plan for dealing with these small weevils,

with trap trees providing an effective diversion to

curtail an otherwise prolonged window of activity.

Applicable organic spray options along with ground-

level strategies become cost-effective when a species

The cherry fruit fly attacks cherries throughout the eastern half of North

America. Dont worry, howeverclosely related cousins wil l find the rest of you!Photo courtesy of NYSAES.

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

7/10

120 th e holis tic orch ar d

can essentially be funneled to far fewer unprotected

trees. More innocuous sorts like earwigs and click

beetles contribute back to the ecosystem, remind-

ing me that tolerance has a place. The accompany-

ing sidebar directed at Japanese beetle is this books

example of taking a particular pest through the

biological wringer in order to fully understand what

all might be done. Rose chafers are noted for having

similar desires for peaches. Out west, look for green

fruit beetles emerging from unturned (big clue, right

there!) manure piles to wreak havoc on nearby soft

fruits.

We blur species lines in mentioning the unspeak-

able evil done by fruit tree borers. The reason for

lumping certain beetles with certain moths applies

to across-the-board damage to wood tissue. Grub

consumption of cambium and sapwood eventuallydoes in whole trees. Physical inspection and removal

involves a great deal of work on your knees with a

knife or similar grub-seeking tool like a drill spade

bit.19Some of the moths can be deterred by pheromone

trapping, but reducing beetle numbers often involves

limiting nearby alternative hosts. Sending an army of

parasitic nematodes into badly infested bark tissue by

means of a mudpack may rectify extreme situations

(see Trunk care in chapter 3, page 79), and even if

you lose a favored tree, you may ultimately save others

by having eliminated the next round of destruction.Botanical trunk sprays made with pure neem oil are

especially promising, acting as an oviposition repel-

lent and adding an element of insect growth inhibi-

tion to all such borer wars.

True bugs exhibit an occasional hankering for

fruit. These include assorted plant bugs, stink bugs,

mullein bugs, apple red bugs, and hawthorn dark

bugs. Conventional recommendations for removing

the alternative plant habitat for such bugs from the

orchard environs go against a diversity plan intended

to attract and hold important beneficials. Bug damage

often takes the form of a feeding sting, which devel-

ops into brownish rough blotches or even outright

dimples on the skin of the fruit. Pure neem oil will

deter feeding and interrupt the molting cycle on all

these guys, whichtruthfullyare rarely an all-out

force of devastation.20

Ill mention a few insect erratica, as certain regional

curveballs can and do show up on occasion. The leaf-

curling midgeis a tiny fly whose larvae set back young

apple tree growth by tightly curling terminal leaves

on the ends of shoots. Less photosynthesis means less

growth. Red-humped caterpillars seemingly are Moths

from Mars that attack apple, pear, cherry, and quince,

defoliating entire branches in just a few days in late

summer. Next years buds will make a comeback, but

meanwhile you can practice the fine art of handpick-

ing off a fleshy meal for the chickens. Pear thripsattack

all deciduous fruit trees by feeding on flower clusters,

causing a shriveled, almost scorched appearance if the

clusters dont fall off the tree altogether. Early-seasonneem oil applications will prevent the majority of

thrips invasions. Scale insects are like tree barnacles

in that they select permanent feeding sites on branch

twigs and limbs. Heavily infested trees appear to be

undergoing water stress, with leaves yellowing and

dropping. Parasitic wasps often keep scale in check

Green june beetles have an affinity for apples and all stone fruits, whether

immature or fully ripe. Feeding damage tends to be sporadic across southeasternstates and into the Lower Midwest. Photo courtesy of NYSAES.

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

8/10

orch ar d dyna mics 121

(use a magnifying glass to look for holes drilled

through the hard shell of mature scale), so unless

youve chosen to kill everything in sight, dont expect

much trouble from either San Jose or oystershell scale.

Last but far from least we must give heed to the foliar

feeders. Allowing mites, aphids, psylla, and leafhop-

pers to run amok can set back tree vigor considerably.

The good news is that much of this is indeed takencare of by numerous beneficial species given a little

time. Commercial orchardists have far more problems

with soft-bodied invaders because many of the chemi-

cal toxins used for significant pests kill the good guys

that would otherwise checkmate foliar feeders, thus

increasing these sorts of problems dramatically. Its

far simpler to count on natural dynamics like preda-

tor mites to get the job done. You can pinch aphid

infestations off terminal shoots on young trees if

necessary, or shut down the ant highway by applying

sticky goo to plastic wrap on the trunk.21If a certain

plum variety appears overwhelmed by honeydew

secretions from aphids and thus accompanying sooty

molds cover most of the canopy, I rely on pure neemoil applications (made at a 0.5 percent concentration

every four to seven days) on that particular tree while

an especially severe problem persists. Woolly, rosy, or

plain green . . . aphids do not like neem. Leafminers

(the larvae of a small moth) tunnel into the cellular

layers of the leaf to feed, but you will rarely see much

Lesser peachtree borer initially makes its presence known by pushing frass out

entry holes in a frenzied assault on cambium tissue at branch junctures. Photocourtesy of USDA Agricultural Research Service.

The resulting gummosis surrounding that larvae is the trees attempt at turning

out the varmint. Photo courtesy of USDA Agricultural Research Service.

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

9/10

122 th e holis tic orch ar d

of this damage in a home orchard because certain

braconid wasps know their duty. Thats the rub in a

sense . . . we actually needlow numbers of foliar feeder

populations to maintain helpful species to a sufficient

degree to keep those same foliar feeders in balance.

Lets consider that next.

Beneficial mathematics

Natural predators are too often judged as being insuf-

ficient at providing complete control of a pest prob-lem. What an appropriate moment to say poo pah!

Dismissing helpful allies in the orchard ecosystem for

not providing a complete solution on a species basis is

exceedingly shortsighted, and frankly arrogant. How

much better it is to understand that several partial

solutions add up to substantial biocontrol. And that

this might just be diversitys way of doing higher math.

Lets consider the codling mothalmost anyone

anywhere will deal with this pest of apples, pears,

quince, and even some apricots and plums. Eggs are

laid singly in proximity to the developing fruit, often

on a nearby leaf if not on the fruitlet itself. Each

female moth will deposit thirty to a hundred pinhead-

sized eggs. These sit exposed for six to fourteen days

before hatching. Certain parasitic wasps can sense

precisely where they are and will lay their eggs insideeach moth egg to provide a feed for their young. Call

that a 2060 percent advantage . . . provided plenty

of flowering diversity exists to support the presence

of plenty of adult wasps.22Just-hatched codling moth

larvae have significantly better odds of avoiding bene-

ficial predators than most moth caterpillars, as this

Tarnished plant bug damage to buds and developing fruit is typically minimalprovided these bugs are not pushed up into the fruit trees by exuberant mowing of allnearby ground cover in spring. Photo courtesy of Alan Eaton, University of New Hampshire.

-

7/30/2019 Bugs and More Bugs: An Excerpt from The Holistic Orchard

10/10

orch ar d dyna mics 123

internal-feeding species bores into the fruit generally

within twenty-four hours. A spined soldier bug or an

especially astute chickadee might end this passage,

however. Still other parasitic wasps lay their eggs in

the larva itself to provide a feed for their young.23

Score that 5 percent given the short duration of expo-

sure. Codling larvae eat the seeds in the fruitlet and

then exit some two to three weeks later, either by

dropping to the ground in a fallen fruit or by crawl-

ing back toward the trunk. Yellow jackets gather suchcaterpillar meat for their young . . . spiders weave,

pounce, and otherwise frolic . . . ground beetles never

let creamy flesh walk on by. Lets take away another

520 percent. Surviving larvae spin a cocoon in which

to pupate beneath bark scales on the trunk or in a

sheltered place at the base of the tree. Woodpeckers

and nuthatches work this situation; tachinid flies

arent averse to sticking an egg within that cocoon to

facilitate a pupal feast. That puts codling moth down

another 1020 percent.

Beyond letting all this happen by fostering biodi-

versity, our job on the insect balance front should

be considered blessedly small in comparison! The

advantages spoken of here apply to all pests to vary-

ing degrees. Spend some time getting to know your

friends and revering their limited contributions in thegrand scheme of things.

est options

Nudging the remaining portion of problematic pests

in line with a human take on reasonable balance for

fruit production is up to us as orchardists. The organic

Green peach aphids are the main vector of plum pox virus in the East. Spring applications of neem oil (part of the holistic spray mix) and numerous beneficials keep

foliar feeders like these guys in check. Photo courtesy of NYSAES.