BrandFinance Journalbrandfinance.com/images/upload/brand_finance_journal_issue_2.pdf ·...

Transcript of BrandFinance Journalbrandfinance.com/images/upload/brand_finance_journal_issue_2.pdf ·...

BrandFinance® Journalwww.brandfinance.com/journalissue 1• OctOber 2011

“We have to change or

we will be left

behind”–Morten Lundal–

group chief commercial officer of

Vodafone

SABMiller’s Graham Mackay on why global brands don’t work

Manchester United victory vindicates Glazers’ strategy

The Campaign for Independent Brand Valuation – where do the numbers come from?

2 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1•october 2011

Contents

4 Vodafone: Morten Lundal

18 Football: Manchester United

15 Governance: David Hensley 10 SABMiller: Graham Mackay

3 EDITORIALBrand valuation companies need to be independent and use transparent methodologies, says Brand Finance CEO David Haigh.

4 INTERVIEWStriking a fine balance Vodafone may be big, with modest overall growth, but it thinks like a medium-sized fast-growing data company, says group chief commercial officer Morten Lundal.

10 BRAND STRATEGYSwimming against the global tide Global brands are not all that Ted Levitt cooked them up to be, argues SABMiller chief executive Graham Mackay.

15 BRAND GOVERNANCEKeeping a good name In a volatile business climate, the governance of corporate brands has become a new business imperative, claims Brand Finance managing director David Hensley.

18 FOOTBALLPlaying in a different league Love them or loathe them, the Glazers’ reign at Manchester United has proved an indisputable success, says Dave Chattaway, head of sports brand valuation at Brand Finance.

24 NATION BRANDSA game of two halves Against an uncertain economic backdrop, nation brand values reflect a growing polarisation between the fortunes of ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ markets. We look at some of the winners and losers.

30 CAMPAIGNWhere do the figures come from? Brand Finance CEO David Haigh analyses the discrepancies between different consultancies’ valuations of the same brands, and calls for more transparency and independence in brand valuation.

The BrandFinance Journal is the official journal of the BrandFinance Institute, published by Brand Finance Plc

Brand Finance plc3rd Floor, Finland House, 56 Haymarket, LondonSW1Y 4RN United KingdomTel: +44 (0) 207 389 9400Fax: +44 (0) 207 389 9401www.brandfinance.com

editor David Haigh, Founder and CEO of Brand Finance [email protected]

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 3

BrAnD VALUATIOn began life in 1988 when Interbrand weighed into the bid battle for ranks Hovis McDougall.The consultancy invented the discipline of brand valuation overnight but left many ragged edges in the methodology, which others have subsequently smoothed out. To its credit Interbrand made the point that brands are highly valuable assets that are often invisible and undervalued. But in 1988 Interbrand was entirely independent and everyone listened to its point of view — long live John Murphy, the voice of independent dissent.

Scroll forward nearly 25 years and Interbrand has been subsumed into a massive global advertising agency. And although brands are now widely recognised as massively important corporate assets, typically representing between 10 and 30 per cent of total corporate value, many boards still treat them as Cinderella assets and regard brand valuation as a dark art or a joke.

Brand Finance plc has promoted the discipline of independent brand valuation for over 15 years. We have created the BrandFinance® Institute, the BrandFinance® Journal and BrandFinance® Forums to promote learning and best practice. We have participated in the development of the International Valuation Standards Council (IVSC) and International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) standards on brand valuation. We constantly push forward the boundaries of this vitally important professional activity. Yet we now face a crisis of confidence in the practice of brand valuation itself, a crisis caused by the publication of annual brand value league tables that don’t appear to comply with ISO 10668 and that, as a consequence, bring the discipline of brand valuation into disrepute.

We’ve been aware of this phenomenon for several years, yet, on the principle that you don’t foul your own nest we have remained silent. However, in the face of growing criticism of brand valuation we believe the time has come to speak up. Mark ritson’s recent ill-informed comments in Marketing Week magazine, the gist of which were to question whether brand values really mean anything at all, were the tipping point.

To this end, we are now launching the Campaign for Independent Brand Valuation to promote best practice in brand valuation techniques, transparency, independence and professionalism. We hold no grudge against anyone in the field. But we feel strongly that it is time for those who care about the integrity of the brand valuation profession to speak up and speak out.

Transparency and independence (both actual and perceived) have become major issues. The fact that Interbrand and Millward Brown publish league tables of purported brand values, yet fail to define ‘brand’, fail to state the valuation date and persist in using opaque proprietary brand valuation methods, is a major problem. All brand valuations should, according to the ISO standard, be completely transparent in terms of methods, data and assumptions.

In addition, the ISO standard requires that brand valuation appraisers must be independent and be seen to be independent. We believe consultancies that are wholly owned by major brand-building and marketing communications companies cannot credibly provide arm’s length brand valuation opinions on brands that they, or their parent companies, create and maintain. In seeking to do so, they inevitably compromise their independence.

Perceived conflicts of interest inevitably taint this newest of all professional disciplines at a time when intangible assets, including brands, are making up an ever bigger proportion of companies’ total worth. John Stuart, the former CEO of Quaker Oats, once said: “If this business were split up, I would give you the land and bricks and mortar, and I would take the brand, and I would fare better than you.”

He was right, and this is why organisations need to be able to rely on credible, independent valuations of these precious assets. We hope, therefore, that all readers of this editorial will back our Campaign for Independent Brand Valuation by arguing the case for independence and transparency to accounting and valuation standard setters, to governmental audiences and to the marketing profession. ■

Editorial

“The ISO standard requires that brand valuation appraisers must be independent and be seen to be independent”

David Haigh CEO Brand Finance plc

4 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1 • october 2011

Interview

Striking a fine balance

BrandFinance® Journal: What were your impressions of the Vodafone brand when you joined the company three years ago?Morten Lundal: The instant impression I got walking in here was ‘big, global, red and professional’. But the brand felt like a work colleague, not someone you would take out for dinner. You couldn’t see the personality. It was more ‘professional’ than ‘intimate’.

I was amazed by the brand’s reach — it has resonance from the biggest German corporations right down to individuals in rural Ghana and India. Very few — if any — brands translate from the boardroom to the field — not even Coca-Cola. Yet there was also an incredible consistency to the brand. There’s no strict policing function at a group level — no ‘brand police’. The strength and consistency of the brand personality has emerged tacitly, over time.

I was struck by the passion too. The brand is 25 years old, so you might expect arrogance, complacency and cynicism. But I found none of that. Instead I found incredible passion for the brand among both employees and customers. Vodafone’s success and strength has been driven and sustained by force of personality: there have been enough people in the management layer over the past five to ten years who have ensured the brand has progressed because they have been passionate about changing it rather than maintaining it.

It is terribly easy to lean back and

look at history. But Vodafone is a very forward-leaning company. We are hopeful about tomorrow: after all, though we are a large company with modest overall growth, we think like a medium-sized fast-growing data company.

BFJ: In what is a new role in Vodafone, how have you helped to change the brand even further?ML: I joined as a regional CEO, a role I held for two years. As part of the process of simplifying and integrating Vodafone, all group commercial ambitions and resources were rolled into one role and I took that role in november last year. I am now responsible for consumer and business products, marketing capabilities, devices, multinational customers, innovation and brand.

Big brands are usually hard to change — but the mobile industry is changing so fast that we have to change or we will be left behind. We have had 25 years where voice communication has been dominant, but the convergence of two concepts — mobile and the internet — around the world adds a whole new dimension to what we are doing. And data is a lot more complex than voice.

So my challenge is twofold: to make the complex simple, and to make the Vodafone brand loved as well as respected.

There have been changes already over the past three years. The operating companies have become much better

at engaging customers in the brand, by tailoring messages to the local market rather than relying on the group to broadcast them from the centre. The Zuzu advertising campaign in India, for example, has been phenomenally successful and embraced enthusiastically by the local population. It is full of personality and humour and shows deep respect for the local context. A more traditional corporation wouldn’t allow that level of deviation from brand mechanisms.

Our experience with the company we bought in Turkey in 2006 exemplifies the benefits to be derived from a combination of good local brand management and a strong group platform. The company, which became Vodafone Turkey in 2007, was one of our more challenging acquisitions. It was operationally in very bad shape, and its ‘brand’ was the worst thing about it. Within two years we have turned the company around, changing operational factors such as network, IT and distribution. But what has led the turnaround is the brand, which has become the business’s key strength. Vodafone Turkey is now the fastest-growing company in the group. More than most places, ‘brand’ in Turkey is not just a communication exercise but also a management philosophy.

not only do the operating companies now have more opportunities to engage customers, but the tone of what we do is changing too to reveal more about what goes on behind the façade. Our

By JANE SIMMS PhotograPhy PETER SEARLE

Morten Lundal took on the Vodafone brand baton when he became group chief commercial officer a year ago. He tells BrandFinance® Journal how he is helping to sustain the company’s forward momentum by making the brand offering simpler and more intimate

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 5

Morten Lundal

“My challenge is twofold: to make the complex simple and to make the Vodafone brand loved as well as respected”

6 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1 • october 2011

Interview

relationship with the McLaren Formula One racing team, whom we sponsor, illustrates that shift. In its first years it was very corporate, and was based on traditional broadcasting and big-brand affinity. We recently extended the Vodafone McLaren Mercedes sponsorship until the end of the 2013 season, and our focus now is on making it more intimate and engaging in order to reach beyond the Formula One fan base to our customers and non-racing fanatics. Our drivers Lewis Hamilton and Jenson Button meet customers in surprising ways — ‘racing’ them on airfields or ‘competing’ with them in strange vehicles around circuits, for example. This adds to both Vodafone’s and McLaren’s personality.

And when we launched our new 2011 season car in Berlin earlier this year, instead of pulling off the cloth to reveal the car, as we have traditionally done, we had customers and employees carrying different parts of the car to an assembly point, where Lewis, Jenson and the mechanics put it all together. That sort of thing is designed to forge closer connections between us and our customers by making us seem much more approachable.

BFJ: How do you manage the Vodafone brand in a way that reconciles the need for global consistency with the need to accommodate local cultural differences?ML: Getting the balance between global and local is important, but the pendulum swings back and forth. Vodafone is the sum of its acquisitions. We would not be where we are today if we had kept local names because, for customers, employees and partners, the brand acts as a sort of glue, or as a common language or shorthand for who we are and what makes us who we are.

But while we have a clear framework, we have heartfelt respect for what is best locally. Our key promise is ‘Power to you’ and we position ourselves as the approachable empowerment expert wherever we do business. There are three pillars to this: ‘more confidently connected customers’; ‘an

unmatched customer experience’; and ‘always competitive’. But the operating companies can interpret that in ways that feel right for their particular market, and may choose to emphasise the different claims as they see fit. We provide the instruments; it is up to them what sort of music they play — provided it meets our quality standard.

However, the balance companies strike between local and global brands depends to a large extent on the

“In the past, perhaps, we were a bit too prescriptive in terms of how local markets should interpret the brand”

VODAFONE FAST FACTS ↓Vodafone is the most valuable british brand, with a market value of

$30.7bnaccording to the brandFinance Global 500.

→ Vodafone, along with Hsbc, are the only british brands in a top ten otherwise comprising us titans including Google, Microsoft, Wal-Mart and ibM.

According to brand Finance, it is the sixth most valuable brand in the world, the most valuable telecoms company in the world, and made profits last year of around

£8.8bnAnnual revenues last year were

£46bn

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 7

Morten Lundal

nature of the business. Taste in beer, for example, has always been a very local matter, so SAB Miller’s more local approach is entirely sensible [see ‘Swimming against the global tide’ on page 14]. At the other end of the spectrum, products like Coca-Cola or BMW or Apple have the same appeal the world over, so their global brand positioning is appropriate for them. A company like Vodafone, however, doesn’t have a tangible ‘product’

to sell: we are selling the ability to communicate over the air. So while a consistent company positioning and core promise is as important to us as consistent product quality is to the likes of Apple, local operating companies need to be able to adapt our core offering to their particular markets.

In the past, perhaps, we were a bit too prescriptive in terms of how local markets should interpret the brand. But that not only demotivated local management,

the results had no resonance with local consumers either. So, for example, we couldn’t have turned the Turkish business around so successfully by applying our traditional global formula. It wouldn’t have worked. It is hard to write an advert in Paddington aimed at consumers in Istanbul.

But there is strong consensus for this model — global platform, local flexibility — at the moment. We describe ourselves as ‘one company with local roots’. Each

LUNDAL AT A GLANCE ↓Current job: Group chief commercial officer, Vodafone (since November 2010) – his first functional roleJoined Vodafone: June 2008, joining the executive committee five months laterPrevious job in Vodafone: Regional CEO Africa and Central EuropePrevious jobs before Vodafone: First job was financial controller at the Norwegian international explosives group Dyno. He then spent six years in consultancy before landing his first senior job, at the age of 33, as CEO of Nordic mobile operator Telenor’s internet business. He held several CEO positions within Telenor, his last role being CEO of Telenor’s Malaysian subsidiary, DiGi Telecommunications. Age: 46Education: General business education at university in Norway, followed by an MBA at IMD in Lausanne. Favourite film: ‘Comet in Moominland’, based on the book by Tove Janssen – “very important to me and to my children.”Favourite book: A Fine Balance, by Rohinton Mistry. “I read it twice, in quick succession, once to find out what happens, and the second time to savour the writing.”Favourite pastime: I play in a band with my two kids. I play a bit of everything, badly, and my kids do the same, but well.”Favourite brands: “Patek Philippe, for its longevity and the craftsmanship that goes into its watches; H&M and Ikea, because they are such well-managed brands; and BMW for its consistent brand positioning over the past 40 to 50 years.”

8 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1 • october 2011

Interview

operating company is a big company in itself, so it is seen as local, even though it is called Vodafone.

BFJ: Why is brand measurement important to you?ML: We are one of the world’s biggest advertisers, and because we invest a lot in our brand we have to take it seriously. We are also big believers in sharing best practice around the group as much as we can.

We have gone beyond brand consideration and preference towards the brand equity model. There are five components to brand equity: depth of awareness, performance/experience, uniqueness/differentiation, emotion and value, and we follow them all in detail, diligently, at a local and group level, and discuss them frequently. Formally we measure brand performance quarterly, for every country, in depth, including against the competition. At local level the brand is assessed monthly, and marketing is assessed weekly.

And we don’t leave it to the marketers. Measurement is done by general management at both local and group level. Measurement is also much more operations and marketing-oriented rather than financial management-orientated, a shift that has happened over the past five years and that is consistent with the greater commercial focus introduced by Vittorio Colao when he became CEO in 2008.

We also seek to quantify return on investment as far as possible, so we can see the relative impact of the various things we do. What’s more, the level of scrutiny and transparency this requires makes for more aware marketers. So measurement is a great discipline on marketers, and we share best practice around the group in order to continuously improve our measurement performance — and brand performance. A year ago we decided to include relative brand performance in the performance criteria of the top 200 people in the company.

But success in brand measurement depends on the amount of attention management gives to it. Management has to care — and we do.

BFJ: Do you think brand valuation analysis can help marketers raise their game?ML: Brand valuation provides an objective view of a brand’s worth, along with a view on relative brand health. So it gives you two additional ways of looking at your brands — which is valuable in itself. When you franchise your brand, as we do, it’s doubly important: knowing the impact our brand has on the bottom line of one of our partner markets helps us to set a fair partnership fee. True, there is no one accepted methodology to brand valuation — it is all a bit messy and arty, rather than scientific. But that’s OK.

BFJ: What’s your view on social media — a triumph of hype over substance, or a critical way to interact with customers?ML: no one predicted its tearaway success, nor, indeed, could have predicted it. But social media has met a need in people to connect in dramatically different and effective ways, and it will evolve in the next five to 15 years and become increasingly strong. Generally, I think people over-estimate the short-term and underestimate the long-term impact. So there is a bit of hype, but you have to take it seriously. It’s a bet you probably won’t go wrong with. You have to engage with young people, and for the young social media is the preferred way of communicating. But it will increasingly permeate other age groups over the coming decade, and for most people will become second nature.

There are, inevitably, lots of ‘dads at the disco’ keen to ‘get on down’ with the young things. But getting into it early, and experimenting while there are no rules, is a good thing. It’s about trying, failing, failing and trying again.

BFJ: What do you enjoy most about your job?ML: I enjoy working for a company that sells such a desirable ‘product’ — the ability to connect people over distances, irrespective of where they are. What was once a lifestyle product is rapidly becoming a lifeline, and it is fascinating

VODAFONE FAST FACTS ↓

→ set up by chris Gent and Gerry Whent in 1985 it grew rapidly on the back of some daring acquisitions. When it couldn’t take over the leading network provider in a country it bought a minority stake, some of which it still holds – including its 45 per cent (recently valued at £58 billion) stake in Verizon Wireless in the us.

→ Vodafone wants to be a key player in the move to data, and, under new chief executive Vittorio colao, is in the process of simplifying the structure of its minority holdings and non-controlled businesses – including selling off minority interests. → it is undergoing a cultural transformation from a process- and compliance-oriented organisation towards one that is more customer focused and effective. to that end, senior management is more streamlined, network-based, empowered and accountable.

its market capitalisation is around

$146.2bnVodafone has 85,000 staff and serves

371m subscribers

it has operations in

30 countries across five continents and works alongside partners in 40 more.

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 9

Morten Lundal

to be part of that. I also really enjoy the international dimension to my job.

The impact of some of the things we do — especially in India and Africa — is also very motivating. I am responsible for the M-PESA product, which allows people who have no access or limited access to a bank account to send or receive money via their mobiles. It has transformed communities in places like Kenya.

BFJ: What do you find most challenging about your job?ML: Striking the balance between standardisation for consistency’s sake, and respect for the local. It is not an easy balance to find, and it probably should shift back and forth. But I am very conscious of my responsibility to manage that balance. It is also intellectually very stimulating. You can’t copy what others are doing, because what we do is inextricably linked with our DnA, our history and our logic. It is interesting to see what others do, but what we do has to work in our own corporate context.

BFJ: If you had to make three predictions about the future of the global telecoms market, what would they be?ML: We will eventually — within the next ten years probably — see data connections where we have voice connections today. That will be a revolution because voice has penetrated Europe and emerging markets. If you can do the same with data — allow people to work on the move, listen to music, surf the web for news, entertainment and information — that can take you into the stratosphere. And we’re getting there. Data grew by 26 per cent to over £5 billion in 2010/11, and will continue to grow. The greatest potential is in emerging markets, where the data uptake today is relatively small.

My second prediction is that, just as we have connected people for the past 25 years, the next 25 years will be about connecting devices. There are already some applications today. For example, fleet tracking allows a delivery organisation to know where its vehicles are and to route deliveries more

efficiently. Increasingly, connecting devices will encompass more ‘smart machines’, from cars to kitchens. For example, vehicles will have increased automation allowing them to communicate with each other and with traffic signals, improving safety, reducing congestion and boosting performance as a result. And in the home you’ll be able to do things like adjust your heating and turn lights and appliances on and off remotely, improving efficiency and reducing waste. This will be a major trend that we have not yet seen the implications of.

And third, enterprises will work differently. One-third of our European revenue comes from organisations (as opposed to consumers) at the moment. Mobile internet will increasingly allow individuals to work in places other than the office, again increasing productivity, reducing costs and so on.

BFJ: To what extent has the marketing industry changed since you started working?ML: The biggest shift has been towards more aware and empowered consumers, facilitated by the internet. They are less automatically respectful because they know more — including about the alternatives. So consumers are in the driving seat and marketers have still not fully accepted that reality yet — witness their continuing reliance on broadcast messages. ■

“Brand valuation provides an objective view of a brand’s worth, along with a view on relative brand health — things that are valuable in themselves”

BrAnD FInAnCE VErDICTDavid Haigh, CEO

Vodafone is the only truly global brand in the mobile telecom sector, with global advertising and sponsorships driving its position as number one. But the brand is riding a maelstrom of change: fixed and mobile services are colliding, data is rapidly overtaking voice as the core service, prices are under regulatory and market pressure, growth has shifted from the developed to the developing world, applications, software and content are now critical success factors and access devices are dominating the future of mobile networks. The battle between Apple, Google, BlackBerry, Samsung and Nokia is brutal.

Against this background Morten Lundal advocates a global approach with greater local flexibility, a shift from a corporate to a more personal positioning, and an emphasis on content to drive data traffic. Anyone who thought Vodafone’s market was stable and mature should think again. Morten has taken the Vodafone brand mantle at a difficult time. However, he displays the good sense, flexibility and ambition to maintain Vodafone as the global leader of this still rapidly growing sector.

10 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1•october 2011

Brand strategy

Swimming against the global tide

TWEnTY-EIGHT YEArS ago last May, Ted Levitt, editor of the Harvard Business Review, wrote one of the very first articles to popularise the concept of ‘globalisation’. He asserted that a global proposition would ultimately always win over the local proposition, and that the superiority of a global offer — both the product and the marketing — would eclipse the cultural variants that country managers always asked for. He also predicted that a centrist corporate movement would prevail based on a creed of one product, one brand, one voice, one ad campaign.

There seem to be, in essence, two interlinked arguments behind this proposition: one based on emotional association, or aspiration, and the other on management practicalities. The first asserts that consumers will naturally aspire to, and drift over time towards, international brands simply because they are international. They are self-evidently better because people all over the world have sought them out. The second argument is that it is practically impossible — unmanageable or unaffordable — to replicate at a local level the quality, look and feel of global brands so the local brands don’t look as good or perform as well.

In the course of my career in consumer goods I have encountered many examples of individuals and companies that believe Levitt’s thesis explicitly. Successful products, companies and careers have been built on it. An example of the first

driver would be in cigarettes where international brands such as Marlboro have delivered a better quality — originally, anyway — and a higher cachet through sophisticated marketing when compared to local alternatives. Another obvious example is Coca-Cola. The second driver would be illustrated by household and personal care categories where consumers lack much emotional connection — for instance to cleaning products — but welcome global brands with a more sophisticated look and better functionality.

Why beer is differentBut beer is different. Alcohol is a mood-altering substance and beer in particular has a history as old as civilization. The highly emotional characteristics of beer brands themselves and their long history and association with place will always dictate a high degree of localism that sets beer brands apart in the FMCG universe. This is reinforced by the economics of producing and distributing what is a bulky, perishable product.

That’s not to say that the brewing industry has been immune to the forces of globalisation. At the turn of this century, the top ten brewers around the world accounted for just over one-third of beer sales volumes. Since then a mass of local and regional brewers — many of them still family owned — have been subsumed into four big players — namely SABMiller, Anheuser-Busch Inbev, Heineken and Carlsberg. These four now account for almost half of

global beer sales volumes, and about three-quarters of the profit pool.

This period of intense consolidation has undoubtedly driven the adoption of global best practice in many areas — from brewing production, to packaging and distribution. But when it comes to brand marketing, each of the brewers has a different take on where they stand in the global versus local debate. To fully understand SABMiller’s perspective and why it differs from the consensus, it’s necessary to understand where we, as a company, have come from.

SABMiller’s evolutionToday we are the biggest drinks business on the London Stock Exchange, with interests in 75 countries across six continents and over 200 brands. You’ll recognise some of them, such as Grolsch, Peroni nastro Azzurro, Pilsner Urquell, Miller Genuine Draft and, after our recent acquisition, Foster’s, but many more of them will be unfamiliar to you — despite being powerful local brands in their respective home markets.

Since coming to London in 1999, our sales and revenues have grown by over seven times to $26.3 billion and our market capitalisation has increased eight-fold. Undoubtedly the global success of SABMiller today is built upon the firm foundations and sound business principles that were laid down many years ago in South Africa.

The springboard for our expansion was the advent of democracy in South Africa, a cause actively supported by SAB. This freed us up to invest outside the country just at the moment when wider geopolitical changes were throwing up new opportunities across Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa.

In the early days, we acquired breweries from governments wanting to privatise. These assets had often

SAB Miller chief executive Graham Mackay challenges Ted Levitt’s hypothesis that the rise of global brands is inevitable and inexorable. The highly emotional characteristics of beer brands will keep beer, at least, resolutely local, he believes

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 11

SABMiller

PhotograPhS SABMILLER

“Brands consumed outside their country of origin actually still account for only about five per cent of world beer volumes”

been badly neglected under public ownership, so we focused on bringing them up to scratch, applying the disciplines that we had learned in South Africa to enhance quality, drive down costs and improve distribution. Our approach to marketing was, where possible, to build existing local brands through strengthening their associations with local heritage and cultural icons.

Despite the rapid consolidation in the beer industry over the past ten years, the beer market has remained stubbornly diverse.

Beer remains resolutely localAnd brewing has remained at its heart a very local business, steeped in culture and tradition that from its earliest beginnings has been associated with place. Up until not many years ago, most beer brands were simply the name of the town where they were brewed. In

many countries that remains the case — notably in Germany, which is why the German brewing industry is still very fragmented.

As the industry evolved, brewers realised that higher-quality beer was dependent on a particular type of water, giving rise to great brewing towns such as Burton-on-Trent, Pilsen in the Czech republic or Timisoara in romania.

Today, however, we can manipulate water to create whatever conditions we like. Hops can be processed and transported across the world. new barley strains are supporting local suppliers in markets with no previous brewing tradition, and we ourselves are experimenting with a new generation of beers which rely on an altogether different set of raw materials and production techniques.

Yet beer remains resolutely local.Of course, as consumers become

wealthier and the middle class grows they look for more sophisticated products, and some are seeking out international brands.

We do cater for that with four distinct international premium brands which talk to consumers’ emotional connections to place or culture, whether it is the Italians’ unquestionable ownership of style typified by Peroni nastro Azzurro, the quality and provenance of Czech brewing found in Pilsner Urquell, the charismatic eccentricity of the Dutch reflected in Grolsch or the American urban cool of Miller Genuine Draft.

But despite the array of imported beers which you will see in London, brands consumed outside their country of origin actually still account for only about five per cent of world beer volumes, and that proportion has changed little over the past ten years. Truly international brands,

12 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1•october 2011

Brand strategy

such as Heineken or Corona, have global market shares in the low single digits, and you need to combine more than 60 of the top beer brands to amass half of total world volumes.

Aspiring consumers are nowadays just as likely to turn to local premium beers, many of which speak to the burgeoning sense of pride and identity that comes with social and economic progress and, particularly in sophisticated western markets, to craft and speciality beers.

For example, in the US the expansion of craft brewers, and in the UK the resurgence of cask-conditioned ale, are aligned with the same concern for local provenance that we have seen in the food industry. But equally it is about place, identity and belonging.

So why are beer brands so susceptible to these associations?

Beer is emotionalMy explanation is that they are emotional constructs, far more than they are physical ones. While there are undoubtedly some highly important functional attributes to which one can appeal in beer — refreshment being the most common — in reality the intrinsic differences between different lagers of the same alcoholic strength and temperature are subtle. After a pint you would be hard pressed to tell two lagers apart in a blind tasting, but a consumer will, on most occasions, have a clear preference. Although they will generally aver that their chosen beer is the one that tastes best, this is simply a rationalisation of an instinctive, emotional choice.

Most marketers could no doubt write an advert for a beer brand, and many of them would emphasise certain recognisable human motivators, such as friendship, male bonding or national pride. But our approach is to dig below the universal nature of these assumptions.

In our view they can’t be accurately applied from one culture to the next without reinterpretation, and local sensitivity and local intimacy are critical to understanding the unarticulated, intuitive relationship that people have with the beer in front of them. For many men beer is possibly the most important

Tyskie Gronie, Poland ↑ As Poland’s largest beer brand with a market share of 18 per cent and heritage dating back to 1475, tyskie is rooted in what it means to be Polish. but while Poland’s history is rich with great artists, composers and philosophers, it is the 15th century and not the 21st which is thought to be the ‘golden age’ of Polish culture. instead its recent history is darker and more troubled, characterised by a succession of devastating wars, which means little from the past 150 years stands in its original place.

consequently, Poles feel they have lost a link to the heritage of their forefathers. they feel destined for greatness, but need external affirmation to feel positive about being Polish. so they will take an avid interest in the performance of Polish players in the english football leagues or hold up robert Kubica, the Formula one driver, as a national hero, because of his success on a global stage. they want proof — validated by a global audience — that Poles can be great.

so tyskie seeks to create and tell narratives that allow Poles to feel better about themselves, providing them with grounds for genuine pride. one example is when we changed the livery of the trucks exporting tyskie to the uK to demonstrate the brand’s status as an export brand and its popularity overseas.

And in a recent television commercial, we played on the czech republic’s reputation as a nation of beer connoisseurs, to give reflected glory to tyskie and, by extension, Poland.

tyskie Gronie in Poland has a market share of

18%

LOCAL HEROES

SABMILLER FAST FACTS ↓

Pilsener is our ‘national’ brand in ecuador with a market share of

80%castle accounts for nearly

one-fifth of our total portfolio in south Africa

These brand stories reflect what SABMiller has, through detailed research, come to understand about how different groups of people relate to their national identify.

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 13

SABMiller

brand in their repertoire of personal products, when it comes to defining who they are. But the male psyche, how men bond and what they aspire to, finds radically different expressions in different parts of the world. In many parts of Africa, fatherhood and the familial responsibility that surrounds it is highly aspirational to young men. But while beer campaigns in the UK do appeal largely to men, one which emphasised fatherhood I fear would be doomed to fail.

We believe that deep, rich and rigorous consumer insight is critical to brand building. I am sure many of our competitors would say precisely the same, but we take it to a level of granularity that borders on the obsessive in order to understand and assimilate those attitudes towards beer which are — from a consumer’s perspective — indefinable.

Even understanding, and combating the drivers of, alcohol misuse force an appreciation of the highly cultural nature of drinking. In the UK we have an undeniable problem among young people for whom drinking to intoxication is entirely acceptable — if not glamorous. In Italy however, where alcohol is typically considerably cheaper than in the UK, drinking to excess is taboo and considered socially unacceptable.

Yet, despite our success in building brands based on strong local consumer insight (see ‘Local heroes’ opposite), we are not infallible. Consumers’ loyalties and identities are regional as well as national, and some of our brands are deeply rooted in very small communities, which are fiercely protective of their way of life, their culture and, indeed, their beer. (See ‘When the locals got vocal’ overleaf.)

These brand stories reinforce the importance of putting consumer insight at the heart of any brand strategy, and having a marketing eco-system that can remain sensitive to the idiosyncrasies of local culture, while simultaneously deploying the most effective and efficient marketing and sales techniques.

We have worked long and hard to develop such a system within SABMiller — one that gives local marketing teams the autonomy they need to respond locally,

Pilsener, Ecuador↑ in ecuador, national identity embraces all epochs of its history, combining catholicism, pagan symbolism and a more secular ideology. When native inhabitants were forced to convert to catholicism by the spanish, the conversion was often not entirely pure, with the result that indigenous elements, such as a polytheistic belief in ‘spirits’, became part of the new religion. the spanish conquerors brought in additional populations from bolivia, Guatemala, and ultimately Africa as slaves, and they too, brought their own beliefs and traditions.

this combination of influences is most powerfully exhibited in the many thousands of fiestas which take place around the country, from the Fiesta of La Mama Negra, which aligns the power of a volcano to the mercy of the Virgin Mary, to the corpus christi celebrations of Pujili, which combine the catholic celebration of Holy communion with traditional celebrations of the harvest and offers of thanks to inti, the inca sun god.

Pilsener is our ‘national’ brand in ecuador, growing lustily and with an 80 per cent market share. its television commercials seek to reflect the complicated and deep-rooted connection of the people to their ancestors and the land.

Castle Lager, South Africa↑ With the soccer World cup taking place in south Africa last year we took the opportunity, not to showcase a global brand to the watching world, but rather to unite south Africans behind our flagship local brand, castle Lager, and build brand equity and loyalty with local consumers.

With 11 languages and a multiplicity of different cultures and political affiliations, the rainbow Nation has been trying to forge a common national identity since the decline of the apartheid state. While most people will acknowledge their south African identity at some level, this still fails to compete with powerful racial, geographic and tribal loyalties still very much in evidence today. south Africa is a country still searching for a voice that both encapsulates the country’s diversity and demonstrates a strong sense of unity to the rest of the world.

our research found one characteristic that unites all south Africans — regardless of their background — is the enormous pride taken in their reputation for hospitality and openness. castle Lager, sponsor of the national football team bafana bafana, created a commercial that encapsulated this in the build-up to the World cup.

Having been in decline for many years, castle has not only stabilised, but is in double-digit growth long after the tournament ended. it accounts for nearly one-fifth of our total portfolio in south Africa.

14 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1•october 2011

Brand strategy

but that utilises the expertise, skill and learnings available across the business. It is an important part of how we can add value and leverage the scale of the group.

This combination of discipline and freedom is cultural as much as structural. Our instincts are to employ the complete individual and empower them to develop bespoke solutions. This avoids the trap inherent in less flexible systems, which lead to ideas that in theory fit all markets, but in reality suit none — that are, in short, the lowest common denominator.

Of course there are some compromises with our local brand model. It is complex and costly, the resulting global business system is hard to manage and it is hard to achieve real scale benefits across the group. But we believe passionately that it is the way to win in beer.

We know we can’t be complacent: as consumers become more sophisticated they become more demanding, they want new and different things and search for more. This means we have to continuously review what local means to make it fresh and compelling to each new generation of consumers.

In summaryWe have embraced globalisation, but with qualifications, as we believe that the beer business is inherently local and will remain so. Our determination to build brands that resonate with local consumers is a key point of differentiation between SABMiller and its competitors.

We recognise that our approach is more costly and more complex to manage, and that in many ways we are ‘swimming against the tide’ identified all those years ago by Ted Levitt.

But we are attempting the use the best of what we know globally, to enhance our offering and delivery locally. In short, we believe we are the most local of the global brewers. And while much of consumer goods industry is focused on identifying how everyone is the same, I would say that SABMiller is trying to work out how everyone is different. ■

This article is based on the Marketing Society Annual Lecture delivered earlier this year by Graham Mackay.

When the locals got vocalthe city of Arequipa is located in the south-western part of Peru nearly 8000 feet above sea level and surrounded by three volcanoes. its rugged territory and tough climate play an important role in the psychological make-up of the people in the region. they pride themselves on being plain spoken, with a fighting spirit and tough character. bullfighting — where two bulls are pitted against one another and the one that runs away is declared the loser — is also an important part of the culture. the people feel an element of their own toughness is characterised by the two animals locking horns.

When we first entered the country, we were naturally offended by the inefficiencies of producing a small quantity of beer for such a remote community. We attempted to introduce cristal, a nationally-available beer, so that we could phase out Arequipena.

We determined that the best time to launch cristal into Arequipa was at the annual fiesta. However the community’s reaction was not what we hoped. in a dramatic, public and hostile display, crates and kegs of cristal were broken open and poured into the drains in the streets.

We learned our lesson and Arequipena thrives to this day, although the packaging and advertising have been refined to reflect more accurately the characteristics of the people and of the geography, including the addition of two fighting bulls on the label.

BrAnD FInAnCE VErDICTDavid Haigh, CEO

In 1983 Ted Levitt wrote his seminal thesis on the ‘Globalisation of Markets’. He put forward the theory that markets were inevitably globalising and that multinationals needed to globalise their brands accordingly. This led to the general belief that monolithic global brands would come to dominate world markets. As a result the intervening 28 years have seen many organisations trying to build monolithic global brands to take advantage of the ‘inevitable’ trend. Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Vodafone, Levi Strauss and Heineken have all gone down the global brand

route, crushing local cultural and taste differences to fit the theory. City analysts too have taken the view that consistent global brands are always ‘best’.

You might have thought that Unilever’s ill-fated ‘Path to Growth’ strategy in the 1990s would have stopped the theory in its tracks. But, although Unilever sacrificed many good local and regional brands at the altar of ‘high growth’ global brands, losing its CEO Niall FitzGerald in the process, the theory has remained top of mind.

However, Graham Mackay, in his quietly-spoken and practical way, finally demolished this accepted wisdom in his lecture to the Marketing Society. He believes that Heineken is really the only beer brand in the world that looks remotely like a global brand, and even Heineken is really strong in only a handful of countries. His view is that beer is a very local taste and that beer brands therefore tend to be local. For example, Fosters is a ‘global’ brand from Australia, but actually most Australians hate the stuff, preferring VB. SABMiller has just bought Fosters’ holding company to capture the VB brand. It joins a stable of similar local brands which have powered SABMiller plc’s results.

Even the stock market analysts are waking up to the fact that local or ‘glocal’ is better than global. In this article Mackay finally demolishes Levitt’s theory. So read on, and long live local brands.

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 15

David hensley

Keeping a good name

“Our brand has little impact on our numbers; it’s our distribution channels that make the difference.” Senior executive in an insurance company 2011

“We leave it for the experts in our marketing team and our advertising agency to manage our brand.” Senior banker 2011

These views are no longer as common as they were a few years ago — or at least the first one isn’t. Most CEOs and CFOs would be able to at least pay lip service to the idea that the brand is one of their most valuable assets. Given the publicity that annual brand-value league tables have enjoyed in various business publications over recent years, that’s not surprising. Brand Finance’s most recent Global 100 brand league table was picked up in 749 different publications around the world in the first week after it was launched.

partners and investors too. It affects all parts of the business.

Similarly, the brand’s reputation is the product of more than just marketing communications. Actions by any part of the business can help to grow — or destroy — corporate brand reputation. In an age where reputation is increasingly influenced by recommendations and revelations in social media, every action or comment by an employee, whether in the call centre or the pub, can potentially increase or destroy brand value. If all of these actions and communications are co-ordinated you can build a strong, coherent brand reputation. If they aren’t, then your brand image will be fragmented, inconsistent and at risk.

Brand equity is the set of perceptions that sit in people’s minds about the brand, perceptions that affect their attitudes and behaviours. Whether someone chooses to buy your product or service rather than a competitor’s, or to invest in your shares, or to come and work for you, is in part determined by their concept of your corporate brand. Is your company seen as a reliable, or innovative, or friendly, or low-cost sort of organisation?

The corporate brand may be worth millions, if not billions, of pounds, Euros or dollars. Brand value typically amounts to between 10 per cent and 30 per cent of market capitalisation, but can be more for extremely strong brands. (See Chart 1 overleaf ) The brand asset is a trademark, which must be protected and has real value — it could be licensed out or sold. This value can today be calculated by reliable methods. Brand valuation may have been a mixture of art and imagination two or three decades ago, but now it is a matter of science and accounting, enshrined in international valuation standards: there

A company’s brand and reputation are invaluable assets and need to be guarded carefully, particularly in a volatile business climate. Boards must go beyond lip service and establish robust governance processes for their corporate brands, says Brand Finance managing director David Hensley

Brand governance

Brand equityin our brand valuations, brand equity is one of the elements of brand strength. We measure brand equity by analysing a combination of factors, including the following.○ Function ‒ people’s perceptions of how good the branded products and services are.○ Emotion ‒ how people feel about the brand. We gauge this from research into the image attributes of the brand versus its competitors, assessing these against driver analysis of the attributes most strongly associated with purchase in the category. ○ conduct ‒ how well the organisation is seen to be behaving on, for example, environmental, social and governance factors.○ LoyaLty ‒ how loyal customers are and the net promoter scores.We analyse each of these factors by reviewing the most comparable market research available to score the brand relative to its peers and competitors. our brand strength index then combines these with measures of the perceived corporate brand security/risk, and measures of the impact of the brand such as margins and forecast revenue growth.

But the second quote remains true for many organisations. Brand management is typically a function that sits in marketing, or marketing communications, or, less frequently, public affairs.

We believe that the corporate brand is too important to be delegated down the organisation. The corporate brand reputation doesn’t help to attract just customers, but employees, business

16 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1•october 2011

Brand governance

is even an ISO standard, ISO 10668, just for brand valuation methodology. Indeed such financial valuation is now required for the accounting of acquisitions. In future we foresee shareholders demanding to see the brand value published as part of the accounts, and movements in its value explained.

The brand has value because of its impact on the three drivers of corporate value — revenues, costs and risk.

Brand impact on revenuesA strong brand affects revenues.1/ It increases people’s propensity to purchase the products and services associated with it — either because it stands for superior or more reliable quality and so simplifies their rational decision-making, or because they feel some personal emotional attachment to it.2/ It increases people’s willingness to pay a premium for these products and services. They see the brand as a proxy for quality, and assume associated products and services will therefore

ChART 1 BRAND VALUE AS A PERCENTAGE OF MARkET CAPITALISATION ($US)

kudos of working for a strong brand means such brands often have to pay less than their weaker competitors to attract good people.

So a strong brand can save costs in operations and Hr as well as in marketing and sales.

Brand impact on riskA strong brand, loved by its customers, also reduces risk and increases the security of future income streams. Strong brands, such as Apple or Accenture, can more easily survive a product failure (iPhone4 reception problems) or a brand endorsement that loses favour (Tiger Woods) than a weaker brand. Weaker brands experiencing such problems are less quickly forgiven: reputational damage can be more severe and harder to overcome, as some people will see the problem as indicative of the character of the brand, rather than — as is the case with stronger brands — an uncharacteristic mistake.

research by Jennifer Aaker and colleagues1 has shown that the level of forgiveness also depends on what sort of image the brand has. People are more likely to forgive transgressions such as service failure by a brand that is youthful and fun than they are those by a brand that has built its reputation on its professional processes.

So a strong, trusted brand is less susceptible to reputational risk, and should therefore expect to have a more secure future cashflow and a lower beta than weaker brands.

But even strong brands are not immune to reputation crises. Toyota, which had spent many years establishing ‘quality, durability and reliability’ as its core brand attributes, suffered enormously when reports filled the news across the globe that its cars were capable of unintended acceleration and failing to slow down when the drivers were trying to brake. Toyota implemented a major vehicle recall to make a mechanical modification to the accelerator pedal, and a software update to the braking system.

Over time, having diligently followed up every claim of braking failure or unintended acceleration, they found there

brAND brAND VAL(sept 2011)

MArKet cAP(sept 2011)

brAND VAL/MKt cAP (%)

Google 48,278 166,075 29%

Apple 39,301 353,518 11%

Microsoft 39,005 208,535 19%

ibM 35,981 208,843 17%

Wal-Mart 34,997 178,880 20%

Vodafone 30,740 131,784 23%

General electric 29,060 161,337 18%

toyota 28,800 120,148 24%

At&t 28,354 169,010 17%

Hsbc 27,100 138,767 20%

be functionally superior. Some also believe they derive some personal ‘self-expressive’ value from their association with the brand — they feel other people will see them as better or smarter or part of a specific group.3/ It increases people’s readiness to try and to buy new products and services. As such it facilitates successful innovation and growth. Innovation is a safer bet for strong brands like Apple, which can expect to get far greater day one and quarter one sales for an innovative new product, than it is for a company with an unknown or untrusted brand.

Brand impact on costsA strong brand can reduce costs, relative to the competition. 1/ It increases loyalty, reducing customer churn and, in turn, the cost of acquiring new customers. 2/ It makes it easier to get into distribution channels: you have to pay less of a premium to win a store listing. 3/ It can also reduce staff costs. The

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 17

David Hensley

True, there are some leading global organisations that pay great attention to their brand. HSBC, the world’s most valuable banking brand, according to the September 2011 BrandFinance Global 100 league table, is a prime example: the bank even includes brand equity as an element in its senior executives’ long-term incentive plan.

But there are many others that don’t. Indeed, a European insurance company told me recently that it wanted to use its brand value ranking — but purely for

public affairs purposes, not as part of its management process.

If brand management and governance is so important and straightforward, why don’t all companies do it? There are three typical reasons.1/ It is judged ‘too difficult’. Companies aren’t aware that brand value can be measured objectively and by internationally recognised standards that will stand up in a court of law.2/ Many think it is ‘unimportant’. They may not appreciate that brands are often more important in business-to-business than consumer markets.3/ They think they already do it. But most actually only monitor brand value in public affairs for publicity rather than management reasons, and don’t see the brand as an essential part of good corporate governance.

But if they don’t have an explicit brand value governance process, what will they say to the investors when the next reputational crisis hits their share price? ■

The brand governance processHow should organisations manage their corporate brand and reputation? there is no one right way. Hsbc, Apple and Google are all extremely successful in managing their brands, but their processes are as individual as their cultures.

However, there are some basic principles for good brand governance, and these serve as a useful checklist that ceos, cFos and non-executive directors can use to ask how well the brand is being managed in their organisations.Know thE Brand’s vaLuE and what drivEs it. understand this at a detailed level, including what factors drive the brand value and how that varies across different customer segments, different geographies and different products and services. establish a monitoring and reporting system so that the board has regular – say quarterly – updates on how the brand value is growing – or not. it is also useful to show leading indicators, such as social media tracking and net promoter scores, as these will be indicative of future brand value movements.EnsurE that this KnowLEdgE is BEing appLiEd to corporatE stratEgy. it should inform decisions on where to invest in growing the brand, where to milk the brand to maximise the return on this important asset, and where to divest or bring in a partner because the brand does not provide a strong enough platform to build the business on.incEntivisE sEnior ExEcutivEs and thE Board to grow thE vaLuE oF thE Brand. include brand value growth and relative brand value performance in performance objectives or as a vesting criterion in a long-term incentive plan.

was not a single case in the USA that could be proved to be down to the failure of the car’s electronic throttle control system. Various other factors were discovered, such as the habit of some American drivers to replace their floor mats each year, placing new ones on top of the old, until the pile of carpet could catch the accelerator pedal, but these were hardly Toyota’s fault. Its reputation as a producer of high quality cars is restored, but it will never recover the sales it lost when the issue was front-page news.

A recent study by EisnerAmper2 into the attitudes of boards of directors to risk showed that boards rank reputational risk second only to financial risk: 69 per cent of them identified reputational risk as their primary concern (after financial risk).

However, most boards that we talk to still don’t have integrated measures to track their corporate reputations and brand value on anything more than an annual basis. In today’s economically pressurised times, with public scrutiny at higher levels than ever, it is surprising that the corporate governance of brand value is not a greater priority for activist investors.

“In today’s economically pressurised times, with public scrutiny at higher levels than ever, it is surprising that the corporate governance of brand value is not a greater priority for activist investors”

61%55%

51%

34% 33%

21%14%14%

ChART 2 PERCEIVED RISk

Aside from financial risk, which of the following areas of risk management are most important to your boards?

Perc

enta

ge o

f res

pond

ents

repu

tatio

nal r

isk

regu

lato

ry c

ompl

ianc

e ri

sk

CEO

succ

essi

on p

lann

ing

IT ri

sk

Prod

uct r

isk

Priv

acy

and

data

secu

rity

risk

due

to fr

aud

Out

sour

cing

risk

Tax

stra

tegi

es

Source: EisnerAmper

69%

Aaker, Fourie and Brasel, “When Good Brands Turn Bad”, Centre for responsible Business, UC Berkeley, 2008EisnerAmper Second Annual Board of Directors Survey, “Concerns about Risks Confronting Boards”, May 2011.

18 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1•october 2011

Football

Playing in a different league

TWO YEArS AGO Andy Lynch, a fund manager at Schroders and a Liverpool fan, told a reuters journalist: “Basically, football clubs are lousy investments. It’s a fantastic sport. It’s great to go and watch. But I would never ever put my money, or the money of anyone I cared for, into a football club.”

His scepticism was understandable. Over the preceding few years many clubs had delisted well below their flotation price, and of the 20-odd clubs that were listed in 2004 just one or two remained. The bottom line was that despite the hundreds of thousands of fans who flocked to pay to watch football every week, and the millions of others who watched the games on TV, generating lucrative broadcasting deals for clubs, this had not, for the large part, translated into a successful investment story.

KBC Peel Hunt analyst nick Batram was equally downbeat. “The City was originally attracted to football because it could see substantial growth in revenues and a significant increase in its intellectual property value as an entertainment product,” he said. But while this had proved to be the case, costs — not least players’ wages — had spiralled. And, as Batram said: “Clubs living beyond their means is not a sustainable business model.”

He is right, of course, and these criticisms of the football industry are

as relevant today as they were two years ago. And Batram summed up the challenge the clubs still face: “You’re dealing with different stakeholders: players, fans and shareholders. Trying to satisfy all three is a very difficult balancing act, particularly when success on the pitch doesn’t necessarily translate into greater profits.”

But the challenge isn’t insurmountable, as the stellar performance of Manchester United FC over the six years since the American Glazer family took it over, demonstrates. When the Glazers bought the club in 2005 it was already well managed — both on and off the pitch — thanks to the winning combination of manager Sir Alex Ferguson and chief executive David Gill and his predecessors. Its stock market valuation peaked at close to £1bn in 1999, but the share price also rose in late 2004 and early 2005 when the Glazers started getting involved. Indeed, the club’s strong earnings track record prompted some to ask whether the £790 million purchase price overvalued the company.

The Glazers believed otherwise, recognising what they called “the untapped commercial opportunity of the Manchester United brand” and understanding that they could exploit the on-pitch success of the club to drive greater value from the brand that would translate into financial results. The club’s latest financial results (revenues

rose to a record £331.3 million in the year ending June 2011, an increase of 16 per cent on the previous year), along with the current brand value as determined recently by Brand Finance, vindicate the Glazers’ approach. Love them or loathe them — and their ownership of Manchester United has been controversial — the business success story of the past six years is incontrovertible.

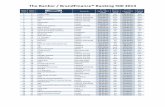

According to Brand Finance’s European Football Brands 2011 league table of the top 30 European clubs, Manchester United’s brand value has more than doubled since 2005, from £197 million to £412 million this year, making it not only the most valuable football brand in the world, but also the world’s most valuable sporting brand. Up 11 per cent on last

PhotograPh SAM KESTEVEN

Their ownership of Manchester United has been controversial, but the on- and off-pitch success the Glazers have presided over during their six-year tenure is beyond dispute. Dave Chattaway, head of sports brand valuation at Brand Finance, explains why Manchester United is the most valuable football brand in the world.

“According to Brand Finance’s ‘European Football Brands 2011’ league table of the top 30 European clubs, Manchester United’s brand value has more than doubled since 2005”

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 19

Manchester United

PhotograPh SAM KESTEVEN

year, the valuation allowed Manchester United to regain pole position from rival real Madrid.

And underpinning the brand value is a financial performance that has improved dramatically over the past six years across a raft of different measures, not least commercial, match-day and media revenue, the three central revenue streams for any football club.

The £46 million development of Old Trafford in 2006 into a 76,000-seat stadium allowed the ‘theatre of dreams’ to offer 8,000 additional seats, and to improve higher-yielding corporate hospitality. And although ticket prices have risen by over 150 per cent over the period, Old Trafford continues to sell out, with match-day revenue rising by 157 per cent to £109 million.

THEN2005

NOW2011

GLAzER GROWTH

Annual revenue (£m) £166 £331 199%

Commercial revenue (£m) £49 £103 212%

Matchday revenue (£m) £69 £110 157%

Media revenue (£m) £48 £119 247%

EBITDA (£m) (%) £46 £110 239%

Wage to turnover ratio (%) 51% 45% -6

Implied business value (£m) £790 £2,000 253%

Brand value (£m) £197 £412 209%

Brand rating AA AAA +1

Commercial partners (no) 6 20 +14

Shirt sponsor value (£m p.a) £9m Vodafone

£20m Aon

222%

Season ticket holders 43,000 54,000 126%

Average attendance 67,750 75,467 111%

Average season ticket price £487 £722 148%

League titles (no) 15 19 +4

BOX 1 ThE GLAZER GROWTh

Media revenue has gone up 247 per cent to nearly £120 million, buoyed by improved domestic and international deals. But the most significant difference between Manchester United FC and rival Premiership clubs is its approach to commercial deals. It has exploited the latent potential in its brand to hook in over 20 global partners, including nike, Audi and Aon, who together are paying over £100 million a year in order to be associated with the champions. The recent £40 million deal with DHL to sponsor its training kit demonstrates just how strong the appetite for brand association is.

But this financial success is underpinned by on-pitch success — and the simple formula that the Glazers used to restore the Tampa Bay Buccaneers

to winning ways (the US football team won the Superbowl four years after the Glazers bought it) has proved equally effective in turning the already successful Manchester United into a beacon of excellence in an otherwise murky world where the combination of sporting and financial success still eludes even the top clubs.

It is no coincidence that its 2010/2011 performance cemented Manchester United’s record as the most successful football team in English football history. It won the top football division for the 19th time (including in four of the past five seasons) and reached its third Champions League final in four years. Such success drives the fan base, which in turn drives media, match-day and commercial revenues, which allows for

20 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | issue 1•october 2011

Football

MANChESTER UNITED FAST FACTS ↓

old trafford continues to sell out, with match-day revenue rising by 157 per cent to

£109mMedia revenue has gone up 247 per cent to nearly

£120m

investment in players, which drives on-pitch success. It’s a virtuous circle. (See Box 2)

The value of Manchester United could be crystallised in the proposed IPO, in which the Glazers hope to realise around $1 billion (£600 million) by listing between 25 per cent and 35 per cent of the club on the Singapore Stock Exchange. If they achieve that price it will value the whole club at around £2 billion — not a bad return on the Glazers’ investment if they chose to sell and could find a buyer with deep enough pockets. The IPO itself will allow them to retain control, wipe out some of the club’s debt (which stands at £308.3 million this year) and expand the Asian operation, while at the same time providing an exit route.

But the Glazers haven’t had an easy ride. The takeover in 2005 was heated and fears about the Glazers’ short-termism and the amount of debt they took on to buy the club led to high-profile opposition in the form of the Green and Gold campaign to overthrow them. But a mooted takeover bid by the red Knights, a group of wealthy supporters, was aborted in 2010 after it transpired that the Glazers put a much higher value on the club than the expected £1 billion offer.

The club’s storming success has done much to quell the dissent, and campaigners’ arguments that the £434 million in interest payments and fees that has flowed out of the club since 2005 could have been invested in players and facilities and in keeping costs down have become ever more hollow as the commercial and on-pitch results go from strength to strength. There is another argument too: that success has come not from the Glazers’ ownership of the club but from the consistently steady hands of the two shrewd men at the helm — Ferguson and Gill.

During his 25-year tenure Ferguson has become one of the most respected and admired managers in the history of the game, for his continuing ability to fashion youthful, exciting squads on a relatively modest budget (the wage to turnover ratio has fallen from 51 per cent in 2005 to 45 per cent today) and for the strong

£103m}

Manchester united’s brand value has more than doubled since 2005, to

£412 m

BOX 2 ThE GLAZERS’ BUSINESS MODEL

are among the brands paying a collective

to be associated with the champions.

Alluring footballand continuedon-pitch success

► champions League football

► Domestic success► cup victories

► Overseas tours► New media► Multi-language► Website

Fanbase growth

► Merit payments► stadium yield

management► More commercial

partners/avenues

Drive media, match-day and commercial revenues

► superstars► Youth programme► english players

On-pitch investment

since 2005

since 2005

october 2011•issue 1 | BRANDFINANCE JOURNAL | 21

Manchester United

Munich match in September. The club has had 18 different managers during Ferguson’s 25 years at Manchester United, including four during the past six years. It is also losing tens of millions of pounds a year. If any club demonstrates the folly of believing it can buy success, Manchester City is it.

Manchester City’s approach is typical of clubs in both the UK and the rest of Europe. Manchester United shows that its blueprint for commercial and sporting success is not easily copied. Things have moved on since the 1990s when clubs were run more like hobbies, but the injection of professional management has done little to remedy the common problem afflicting clubs — the clash between sport and business ‘values’ — which threatens to kill the game.

Some observers believe UEFA’s new Financial Fair Play regulations, which require clubs to live within their means, will bring much-needed discipline and force clubs to balance their books. The choice clubs have is to cut costs or buy in superstars who will generate additional revenue for them. Most won’t entertain the former so are gambling on the latter, but while they may comply with the letter of the law, many are expected to seek ways round the legislation.

The current state of play is unsustainable, and if clubs can’t regulate themselves, it is likely to take some high-profile casualties — a rich backer pulling out, a club having to cancel a game or unable to pay its players — to bring them to their senses. It is not a question of whether the bubble will burst, but when.

In the meantime we are likely to see a polarisation between the best and the rest. While emulating Manchester United’s success may be a pipe dream for many, there are steps clubs can take to improve their fortunes. The combined brand value of the top four European teams surveyed by Brand Finance is over £1.7 billion — more than the combined brand value of the other 26. The ones at the top have been able to convert their on-pitch success into off-pitch commercial returns. Driving the divide is consistent domestic success and Champions League presence; large commercial, developed and fully

team ethos at the club. Gill, a chartered accountant who

became chief executive in 2003 after six years as finance director at Manchester United, has proved equally adept at juggling the club’s finances. Last year’s record pre-tax losses of £79.2 million were affected by one-off costs related to a £526 million bond issue, but were deftly turned into a record pre-tax profit of £29.7 million this year, and Gill’s repeated insistence that the club can shoulder the interest burden and still compete for the best players is borne out in the results.

But one of the strengths of the Glazers’ management has been to value the best of what they have and work hard to retain and build on it. Keeping a man like Ferguson, the club’s ultimate brand manager, by giving him the resources and autonomy that allow him to continue to deliver consistent footballing success in the way he knows best, is no mean feat and unusual in both footballing and business circles

Where the Glazers have really upped the club’s game is on the commercial front. revenues have risen by 212 per cent, from £49 million in 2005 to £103 million today, nudging over £100 million for the first time this year after an annual increase of 27 per cent. They have expanded the commercial team from two to 50 people, bolstering it with talent and experience from the entertainment and consumer goods sectors from both sides of the Atlantic. Commercial activities are sharper and more professional.

When the AIG shirt sponsorship was nearing its end the commercial team sent the top 50 brands they had targeted as potential successors a Manchester United shirt emblazoned with the respective logos to hook them in. But they didn’t go with the highest bidder, rejecting a big conglomerate in favour of the arguably more neutral Aon. They are also better than other clubs at showing potential partners what return they can get for their investment, and use the reassurance of the strong Manchester United brand to support their sales pitch.

new commercial deals since the overhaul of commercial operations in 2008 has brought into the Manchester

United fold partners including Chilean vineyard Concha y Toro, South Korean tyre manufacturer Kumho Tyres and, most recently, Malaysian snack brand Mister Potato, which targets United’s five million-strong fan base in Malaysia.

Manchester United’s commercial director richard Arnold called the deal “an excellent example of the global appeal of Manchester United and its ability to attract well-established but ambitious companies into partnership.”

But while Manchester United’s slick commercial approach may be unique in football, it’s common in heavily branded industries from technology to fashion. All Manchester United is doing is taking best practice from companies like Apple or Prada and applying it to their own business.

Fans from rival clubs must look at the Glazer family detractors with incredulity, because what they have achieved during their six-year reign is the difficult balance between on-and off-field success that eludes every other club. You’ve only to compare United’s record with its cross-town rival Manchester City to see how easy it is to get things out of kilter.