Brampton - L2-I MUNICIPAL REGISTER OF CULTURAL HERITAGE … · 2014. 6. 20. · LISTING CANDIDATE...

Transcript of Brampton - L2-I MUNICIPAL REGISTER OF CULTURAL HERITAGE … · 2014. 6. 20. · LISTING CANDIDATE...

L2-I

MUNICIPAL REGISTER OF CULTURAL

HERITAGE RESOURCES

LISTING CANDIDATE SUMMARY REPORT

River Road - Cultural Heritage Landscape

November 2009

BRAMPTON HERITAGE BOARD

Antonietta Minichillo nm. January W,2fll0 Heritage Coordinator

BRAMPTOn

HERITAGE

BOARDBRAMPTON

U2.-2

PROPERTY LOCATION DATA

See individual property data sheets.ROLL NUMBER

See individual property data sheets.PIN NUMBER

See individual property data sheets.MUNICIPAL ADDRESS

PROPERTY NAME

See individual property data sheets.LEGAL DESCRIPTION

SECONDARY PLAN

ZONING

GPS COORDINATES

6WARD NUMBER

PROPERTY DESCRIPTION This area of Brampton has a distinct heritage character which consists of a rural and cottage like setting with narrow, tree lined roads, scenic views over the surrounding landscape and the ever present influence of the Credit River along with a series of vernacular buildings.

PROPOSED FUTURE MITIGATION

Indicate all that should be applied: -Historical Plaque

-Historical Plaque -Heritage Designation of individual properties

-Heritage Designation -Avoidance Strategies as Required

-Heritage Conservation Easement -Heritage Impact Assessment as Required

-Avoidance Strategies as Required -Demolition Control Protocols

-Heritage Impact Assessment as - Archaeological Impact Assessment as Required Required

-Archaeological Impact Assessment as Required

-Adaptive Reuse Plan as Required

-Demolition Control Protocols

-Minimum Maintenance / Property Standards Protocols

LZ-3

STATEMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE VALUE

Cultural Heritage Value:

The area of River Road is located within the South Slope physiographic region which forms a major portion of the southern flanks of the Oak Ridge's Moraine.

This area of Brampton has a distinct heritage character which consists of a rural and cottage like setting with narrow, tree lined roads, scenic views over the surrounding landscape and the ever present influence of the Credit River along with a series of vernacular buildings.

River Road is located along a particularly scenic portion of the Credit River Valley. Both the built and natural elements of the River Road area are features which give it a distinctive character and contribute to its merits as a cultural heritage landscape. The area retains its rural character and the built heritage fabric remains largely unaltered.

A Cultural Heritage Landscape:

Even the most ordinary landscape is of importance because it speaks to questions of human influence over space including ethnic, religious, political, environmental, and economic (Groth 1997, 18). Related literature on landscapes tells a similar story. Melnick and Alanen claim that the landscape "serves as infrastructure background for our collective existence...[and] the image of our common humanity" (2000, 15). In their examination of the landscape, Melnick and Alanen also contend that all landscapes are cultural because any space affected by the presence of human beings is, in essence, a cultural landscape (2000, 15). Therefore, each landscape is meaningful as it reveals some aspect of culture and humanity.

McMurchv Woolen Mills:

The properties along River Road were once part of Hutton Park Limited, and were affiliated with the McMurchy property.

The McMurchy Woolen Mills and Powerhouse, nearby designated structures, were originally owned by J.P. Hutton. In 1885 the Powerhouse generated 100 horsepower of hydro-electric power, which was considered an engineering phenomenon at the time. The Powerhouse powered the woollen mill and also served as a power source for the Brampton area after Mr. Hutton built a 2200 volt line to this area. The designation reports for the powerhouse state that it powered the first outdoor lamp, which was located in front of the Queen's hotel. In 1886 it powered 18 additional outdoor lights. The Powerhouse also supplied power to at least three Brampton factories.

u^-^

The electrical radial line crossed the property at Embleton Road in 1925 to bring people to the park from Toronto to Guelph. When Mr. Thomas Moorehead took over ownership from John McMurchy, he divided the northerly shoreline, in conjunction with Andre Ostrander, into a forty-two lot subdivision (D-25). These fifty foot were purchased by many Torontonians as summer retreats. For many years the cottages were a vital part of the local church and community. Mr. Moorehead added another subdivision, No. 311, at the entrance to River Road with another thirteen lots. All of these cottages have now been turned into permanent residences.

The park was a favourite recreational place with a variety of facilities that were the centre of many social events.

The community of Huttonville is located to the immediate south of River Road. Situated on the Credit River, Huttonville was a former enterprising village that was named after J.P. Hutton, an early mill owner. Huttonville was founded in 1848 around a small lumber mill. Today, it remains a distinct part of the City with a unique village character making the area both picturesque and rich with heritage attributes.

Gooderham and Worts:

Gooderham and Worts was a Canadian company that was once the largest distiller of alcoholic beverages in Canada. Its former manufacturing facilities on the Toronto Waterfront are today the well known Distillery District.

The company was founded by James Worts and his brother in law William Gooderham. Worts had owned a mill in Suffolk, England and came to Toronto in 1831 and established himself in the same business. He built a prominent windmill at the Toronto waterfront near the mouth of the Don River. The next year Gooderham joined him in Toronto and in the business. The business prospered, processing grain from Ontario farmers and then shipping it out via the port of Toronto.

In the second half of the 19th century the firm rose to become one of Canada's most prominent industrial concerns. Under the control of William's son, George Gooderham, production increased to over 2 million gallons a year, half the production in Canada. The distillery itself expanded becoming one of Toronto's largest employers. As well as keeping interests in the milling and brewing trades, the company expanded into other ventures. It had a controlling interest in the Toronto and Nipissing Railway, one of the main lines that transported grain from the rural regions north of Toronto. In 1892 the company constructed the Gooderham Building, still a notable Toronto landmark, as its new headquarters.

HERITAGE ATTRIBUTES

Cultural Landscape

Historical / Associative

Contextual

uz-s

-Elements of built heritage (small modest vernacular cottages/buildings)

-Elements of natural heritage (mature vegetation, Credit River Valley, rural setting)

-Narrow tree lined roads, scenic views, Credit River and its steep valley sides

-This settlement area helps illustrate the significance of this stretch of the Credit River as a popular spot for cottages for Toronto residents;

-Significant associations with the growth of Huttonville and the history of Huttonville Park;

-Significant associations with the McMurchy family, the Mill and Powerhouse which were a driving force behind the development of Huttonville;

-Connection to the Gooderham and Worts Distillers

-River Road is a virtually unaltered cultural heritage landscape within the City of Brampton; as a whole, it contributes to a better understanding of this area of the City

-Mature trees and other vegetation contribute to the urban forest;

-The River Road area is an important streetscape which is still characterized predominantly by small original cottage style housing;

-Mature vegetation and close proximity to the Credit River, Huttonville, and the McMurchy Powerhouse and Mills make this landscape an important one on several levels.

1-7.-*>

CONSTRUCTION OR CREATION DATE

TYPE OF HERITAGE

RESOURCE(S)

Cultural Heritage Landscape -archaeological site

-heritage district

potential

-building

-cemetery-burial site

-structure-object

-historic site

-historical

associations

-historic ruin

-cultural heritage

landscape

CRITERIA GRADE A (as a collective whole)

CURRENT USES AND FUNCTIONS Residential/Open Space

SUBMISSION Heritage Resources Sub-Committee

EVALUATION DATE September 2009

EVALUATION BY Antonietta Minichillo

SUBCOMMITTEE November 2009

BHB DATE November 2009

Ul-7 MAPS:

Maps of the River

Road area. One can

clearly distinguish

this unique character

area through the

presence of the

Credit River. Also,

the names of close

by streets are

indicative of the

history of this area and its connection to

Huttonville.

U.Z-8

LEGEND

LAKES

N HYDROLOGY

HERITAGE PROPERTIES

• A-MOST SIGNIFICANT

B-SIGNIFICANT

• O - PART IV

PROPERTY FABRIC

BOUNDARY OFN CULTURAL HERITAGE

LANDSCAPE

This map identifies the heritage properties located in the general vicinity of River Road. The heavy concentrations of heritage resources in this area

are mostly connected with Huttonville.

The map also functions to reveal the unique lotting pattern of this area especially when juxtaposed to

the more suburban qualities of nearby streets.

Small and narrow lots backing on the Credit River Valley makeup the properties along River Road.

L/2.-^

These photographs along River Road give a sense of the natural characteristics which contribute to the

cultural heritage value of this landscape. The narrow road and the significant tree canopy are clearly visible.

L.1- tO

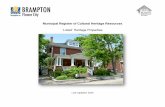

otographs of some

of the quaint cottage

type residences that

characterize this area

and contribute to its

unique character within Brampton.

10

U2.-V\

Photographs of some of the quaint cottage

type residences that characterize this area

and contribute to its

unique character

within Brampton.

11

U.Z-12

Above are a range of topographical maps for this area dating from 1918 to 1972. The maps show

the development and growth of River Road and the surrounding area.

12

U2.-I3

13

u.a-14

Various

photographs of the

range of activities

people enjoyed in Huttonville Park.

Above: Dam with

spillway built in

1923.

Centre: Entrance

into Huttonville

Park.

Below: Pavillion and

refreshment booth

built in 1909.

14

U2.-IS Additional Information - Gooderham and Worts

Gooderham and Worts was a Canadian company that was once the largest distiller of alcoholic beverages in Canada. Its former manufacturing facilities on the Toronto Waterfront are today the well known Distillery District.

The company was founded by James Worts and his brother in law

William Gooderham.

Worts had owned a mill

in Suffolk, England and came to Toronto in 1831

and established himself

in the same business. He

built a prominent windmill at the Toronto waterfront

near the mouth of the

Don River. The next year Gooderham joined him in Toronto and in the

business. The business prospered, processing grain from Ontario farmers and then shipping it out via the port of Toronto. In 1834 Worts wife, Elizabeth, died during childbirth. Two weeks later Worts killed himself by throwing himself into the windmill's well and drowning.

Gooderham served as the sole manager of the business until 1845 when he made Worts' eldest son, James Gooderham Worts, co-manager. With a surplus of wheat, in 1837 Gooderham expanded the company into brewing and distilling and soon this lucrative business became the firm's main one. In 1859 work began on a new distillery complex, the area that today is the Distillery District. It was built on the waterfront with easy access to Toronto's main train lines. In 1862, its first full year of production, the facility made some 700,000 imperial gallons of spirits. At that time it was a full quarter of all the spirits produced in Canada.

In the second half of the 19th century the firm rose to become one of Canada's most prominent industrial concerns. Under the control of William's son, George Gooderham, production increased to over 2 million gallons a year, half the production in Canada. The distillery itself expanded becoming one of Toronto's largest employers. As well as keeping interests in the milling and brewing trades, the company expanded into other ventures. It had a controlling interest in the Toronto and Nipissing Railway, one of the main lines that transported grain from the rural regions north of Toronto. In 1892 the company constructed the Gooderham Building, still a notable Toronto landmark, as its new headquarters.

By the end of the nineteenth century the company's growth began to slow. Beer and wine became more popular in Canada, reducing sales of whiskey. The rise of the temperance movement also harmed the company with the Ontario Temperance Act of 1916 banning the sale of alcohol in the province. The company survived by exporting alcohol beyond Ontario, such as to Quebec, where a good portion then would make its way back to Ontario. The firm also relied on its other ventures, most notably the production of antifreeze.

15

Background Information on Cultural Heritage Landscapes - Antonietta Minichillo

The Social Characteristics of Historic Preservation: Possibilities and Responsibilities

"For although we are accustomed to separate nature and human perception into two realms, they are, in fact, indivisible. Before it can ever be a repose for the senses,

landscape is thework ofthe mind, Its scenery is built up as much from strata ofmemory as from layers of rock" - Simon Schama

Introduction

This chapter delves into the social attributes of preservation, which present both

challenges and opportunities. It argues that the presence of heritage resources can

contribute to memory and identity. However, questions emerge when we consider whose

heritage is being preserved, which stories are being told, and for whom we undertake

preservation activities. In order to understand the complex social dimensions of historic

preservation this chapter will engage with relevant literature and explore the multiple

linkages between landscape, memory, and historic preservation.

The definition of heritage itself, the relationships between heritage and memory,

and the meaning of individual and collective memory can be contested and constantly

debated. My purpose in this chapter is not to provide the precise definitions of these terms

or the exact history of their evolution; rather, I will highlight that a relationship does exist

between people and space and that old buildings are of particular relevance in this

relationship. These connections also pose particular dilemmas in the preservation field in

terms of inclusivity and representation of all groups. And although complete inclusivity and

accurate representation might be impossible to achieve, it is important to understand the

possibilities and responsibilities when we attempt to engage with such issues in the field of

preservation.

The Landscape

In order to carry out an exploration into the social attributes of preservation, it is

important to first examine the role and value of the spaces where historical buildings

reside, the landscape. It is argued that studying landscapes can reveal "the history of how

16

L2.-17

people have used everyday space - buildings, rooms, streets, fields, or yards - to

establish their identity, articulate their social relations, and derive cultural meaning" (Groth

1997, 1). Even the most ordinary landscape is of importance because it speaks to

questions of human influence over space including ethnic, religious, political,

environmental, and economic (Groth 1997, 18). Related literature on landscapes tells a

similar story. Melnick and Alanen claim that the landscape "serves as infrastructure

background for our collective existence...[and] the image of our common humanity" (2000,

15). In their examination of the landscape, Melnick and Alanen also contend that all

landscapes are cultural because any space affected by the presence of human beings is,

in essence, a cultural landscape (2000,15). Therefore, each landscape is meaningful as it

reveals some aspect of culture and humanity.

Dolores Hayden believes that the cultural landscape is "the history of human

patterns impressed upon the contours of the natural environment. It is the story of how

places are planned, designed, built, inhabited, appropriated, celebrated, despoiled, and

discarded" (Hayden 1997, 15). This speaks volumes about the pertinence of the study of

cultural landscapes; all of our surroundings, pristine and demolished, inhabited and

vacant, beautiful and unsightly, are a product of the ideologies, cultures, politics,

economics, design, aesthetics, values, and beliefs of humanity. Hence, the landscape and

its built and social fabric can be understood as a testament to change and continuity.

When developing these ideas further, it can also be argued that the landscape is a

text, a history of people, how they lived, how they worked, and how they interacted with

space. This is the power of the landscape; it functions as a story book that tells us about

our predecessors and will inform our descendants about us, what we valued, what we

accomplished, and what we have failed to attain. The landscape is a representation of its

inhabitants; it is, in its most basic and untainted form, a representation of humanity

(Hayden 1997,12).

17

Memory and Identity; History and Heritage

It is necessary to consider memory and identity as well as history and heritage, and

the changes that have occurred in the way we understand these terms. In order to do so

this section explores the work of Pierre Nora (1984) who primarily focuses on the heritage

of France but has findings that are applicable to North America as well. According to Nora

(1984), an awareness of the importance and resurgence of history emerged in France in

the 1970s, but later the effects became universal. "The explosion of memory was

worldwide. For multiple reasons and in various forms, it touched all areas of civilization

and every country" (Nora 1984, x). Consequently, the way in which people relate to the

past started changing; history, and subsequently memory, became an important part of the

everyday. People's relationship with the past has evolved in various ways and has resulted

in citizens demanding an acknowledgment of the past. As a result, there was a growing

interest in commemorative events, museums, and a general attachment to heritage (Nora

1984, x). The trends toward the resurgence of memory, both in the landscape and as a

part of people's identity, began to reshape the physical and social fabric of cities around

the world as an increasing number of museums, archives, monuments, and plaques began

to emerge as a testament of our new relationships with the past.1

The landscape began to reflect the increased desire for the recognition of the past,

and the concepts of memory and history witnessed transformations that also affected the

notion of identity. Nora (1984) asserts that history aspired to a scientific status, and that

history built itself up in opposition to the meanings associated with memory. Memory was

generally accepted to be based on private testimony, thus it was viewed as misleading or

inaccurate, whereas history was considered to be collective. With the increased

awareness and longing for the past, the ways in which history and memory were

understood changed to allow for the realization that collectives could also have memories.

1It is important to notethatNorarefers to reemergence of memory which happened in the 1970s; he acknowledges that heritage andmemoryplayed an important rolein earlier periods of manyEuropean cities in theirattempt to create a national identity. This particular aspect of hisworkfocuses on the revival of heritage worldwide, which isof particular importance ash allows for an understanding of thecurrent interest in heritage andidentity.

18

Ultimately, this changed individuals' relationships with their communities and society at

large because they began to recognize that their common memories transcended history

since they were more personal in nature (Nora 1984, xi).

With the changes in the meanings of memoryand history, a shift in the concept of

identity occurred almost simultaneously (Nora 1984, xi). Nora argues that as the notion of

memory changed from one that is individual to one that is collective, so too did the notion

of identity. Identity is generally accepted as being based on individual experiences,

however, "[it] has become a group category, a way of defining us from without....[I]dentity

like memory is a form of duty (Jew, Black, etc.)...it is at this level of obligation that the

decisive tie is formed between memory and social identity....[T]he two terms have become

all but synonymous" (Nora 1984, 6).

It is important to be critical of Nora's work as the distinctions between memory and

history, and individual and collective identity, may be too simplistic, and the North

American experience may also reveal differences in these shifts. Although this discussion

is complex and can be elaborated on extensively, the basic premise remains that new

types of connections exist between society, space, and history.

Connecting Space and Identity

The understandings of space have been broadened to incorporate notions of

identity. Gill Valentine (2001) provides an analysis of space, an overview of the way that it

has been understood and conceived by geographers, and a discussion on how it has

changed over time. Valentine's examination of the study of landscapes reveals that during

the 1960s and 1970s space was wrongly conceptualized as an objective physical surface

with fixed characteristics, and with those characteristics, social categories were made and

identities were mapped out and assumed to be permanent and mutually exclusive. The

way in which geographers understand space, society, and the interaction between the two

has been reassessed. Valentine's work builds on that of Nora's as she asserts that "space

is now understood to play an active role in the construction and reproduction of social

19

identities, and social identities and relations are recognized as producing material and

symbolic spaces" (Valentine 2001, 7).

Cities in particular are spaces that are decisively shaped by cultural forces. Culture

found in cities binds people together and creates a sense of identity rooted in history, and

found in place. Therefore, sociological conceptions of identity are affected by physical

spaces, and as a result, the interconnectedness of identity and space is revealed. Michael

Dear and Jennifer Wolch recognize the constant interplay between the social and spatial:

"social life structures territory...and territory shapes social life" (quoted in Hayden 1997,

23). This reveals a dialectic affiliation between people and place, exposing both the

complexities and potential presented by landscape's relationship to and with people.

In exploring the city, Pike Burton (1997) focuses on how art - sculptures,

architecture, literature, and paintings — reflects social, political, and economic conditions

of a given society. Burton views the city as "man's single most impressive and visible

achievement" (1997, 243). Each city is understood as having its own history, embodying a

complex nexus of the positive and negative, conscious and unconscious. The city's

features are a reflection of attitudes and values; it represents feelings towards civilization

and culture. Understanding the city as an image or representation through its physical

structures underlies the important contributions to the landscape made by people,

processes, and power structures. Acknowledgment of the efforts made by others is what

brings memory and history to life within the dynamic of the city (Burton 1997, 245). Burton

(1997) maintains that each individual, group, association, and community is an active

participant in the creation of the landscape.

Mike Crang (1998) presents arguments similar to Valentine (2001) and writes that

we cannot, and should not, see landscapes as simply material features. Rather they can,

and should, be understood as "texts that can be read...which tell...stories about...[people's]

beliefs and identity" (Crang 1998, 40). According to Crang, "the shaping of the landscape

is seen as expressing social ideologies that are then perpetuated and supported through

20

the landscape" (1998, 28). Hence, the landscape is an important text for understanding

cities, and Crang places particular emphasis on older buildings which are present in the

city. Space, therefore, has important connections to people's identities, and those

identities are important ingredients in the making of space.

Complex Landscape Meanings

Paul Shackel (2001) believes that the dynamic nature of landscape is directly

related to memories and sentiments that are associated with a particular landscape.

Memories are an important component in the creation of the landscape; "[they] can be

about a moment in time, such as a protest or a riot, or they can be about a longer term

event, such as a war or a social movement" (Shackel 2001, 2). He contends that

understanding the reasons why some things are remembered while others are not is

necessary to critically evaluate the landscape. The groups that are behind preservation

decisions dictate to some degree what will be remembered and what will not. The various

representations of history and memory, because they are in fact a choice, will ultimately

diverge in meaning and importance from one individual to another. Thus, we cannot

assume "that all groups, and all members of the same group, understand the past in the

same way. The same historical and material representations may have divergent

meanings to different audiences" (Shackel 2001, 2). It is also important to consider that

new stories or histories are constantly being created and recreated by the presence of

existing and new Canadians. Preservation activities do not have to be limited to

established landscapes or groups; they can strive to include the histories of all Canadians.

Furthermore, new Canadians might not have the same level or any level of attachment to

certain landscapes and thus, preservation is challenged in its ability to connect with all

groups. It is my belief that having historic buildings in the landscape will help new

Canadians to understand and connect with their new home, if they so desire. With the

same token, we must broaden definitions of heritage to include non-traditional elements

such as immigrant histories and foreign influenced architecture, in other words, elements

21

not exclusive to Canada's Anglo-Saxon population.

Different versions of the past are communicated through different institutions and

groups because "individual memory is closely linked to a community's collective memory,

and there is sometimes a struggle to create or subverta past byvarious competing interest

groups" (Shackel 2001, 3). As a result of the conflicting and sometimes contradictory

interpretations of history, collective memory tends to rely on various sources for a more

complete understanding of the past. The realization of the multiplicity of history is critical in

the field of preservation; ifwe fail to recognize this, we risk perpetuating limited accounts of

history through preservation activities.2

Sentiments and Symbolism

Journalist Robert Fulford identifies the power that the city landscape exerts over

citizens' relationships with one another:

Living in a city with a unique character can give life a knowable context and helps us understand ourselves as individuals. The built city can join its citizens together or push them apart, hide our collective memories or reveal them, encourage our best instincts or our worst. In a pluralistic society that lacks common beliefs, public physical structures provide an experience we all share, a common theatre of memories (1995,14).

Landscape holds power because of the symbolism found in its built form, and the same

built form functions as a tool with which cultural and collective memory is stored. Fulford

(1995) brings together the ideas of memory discussed by Nora (1984) and the importance

of the landscape asserted by Valentine (2001) because he reveals the importance of

physical structures as the foundation for common memories. In due course, the built form

becomes an integral component of our cultural and collective memory. Rypkema (2005)

feels that the city has and conveys its own memory and that its ability to do so is linked to

2Mirzoeff (2000) complicates the notions of identityandmemorypresented above byplacing themwithin theeraof globalization. Mirzoeff (2000) speaks to notions of identity in an age of globalization andpostnationalism, arguing that "in place of firm notions of identityhas come aneraof mass migrations, displacements, exile andtransition" (Mirzoeff 2000,1). As a result, there are significant implications forculture and memorybecause cultures are nolonger rooted inone nation, rather, cultures cross borders andare therefore in a constant stateof flux. This provides anotherdimension to identity, culture, andspace thatisimportant to consider inthefield of preservation asit mayhave significant consequences of the field.

22

L.2.-Z3

the significance we ascribe to places.3 "The city tells its own past, transfers its own

memory, largely through the fabric of the built environment," explains Rypkema, "[historic

buildings are the physical manifestation of memory - it is memory that makes places

significant" (Rypkema 2005, 9).

The work of Agnes Heller (2001) was written in the wake of Nora's contributions.

For her, culture is not only a significant factor in the creation and preservation of

landscapes but also in the formation of cultural memory. She states that cultural memory

is linked to places - places where a significant event has taken place or is remembered.

Cultural memory constructs identity, people create cultural memory, and cultural memory is

important to a group's existence (Heller 2001, 2). Heller believes that "the presence or

absence, the very life or decay of a people, does not depend on the biological survival of

an ethnic group, but on the survival of shared cultural memory" (Heller 2001, 2). Places

and buildings, according to Heller, are the most concrete and distinct representations of

cultural memory.

Cultural memory seems to be very strong, and many people have a desire for

memory and remembrance (Heller 2001, 4). Walter Firey made a similar argument in the

1940s when he proposed that spaces are Aa symbol for certain cultural values that have

become associated with a certain spatial area...[and] may bear sentiments which can

significantly influence the location process© (Firey 1945,143). Firey's theory allows for the

influences of people's values and beliefs to take physical expression in the landscape, both

creating it and preserving it. The work of Firey and Heller are important for understanding

why elements with historical significance have survived in societies that are based on

capitalism, in which one could assume that economic considerations would prevail and

historic structures might not. Sentiments associated with particular places and structures

3Donovan Rypkema is principal of Place Economics, aWashington, D.C-based real estate andeconomic development-consulting firm. The firm specializes in services to public and non-profit sector clients whoare dealing withdowntown and neighborhood commercial district revitalization andthe reuse of historic structures. In 2004 Rypkema established Heritage Strategies International, anewfirm created to provide similar services to world-wide clients. Healso teaches agraduate course in preservation economics atthe University of Pennsylvania (Place Economics, 2007).

23

U2-24

can play a significant role in terms of what happens to those very spaces. One can

conclude that, on some level, many people recognize and appreciate the physical fabric of

cities and the linkages to their own sense of place and self. Once they come to

understand that the city's built fabric is actually linked to their memory and identity, historic

elements take on increased meaning and value, and the role of preservationists then

becomes an important one.

The Role of Historic Preservation

If as a society we are endowed with historic buildings, appreciate their role, and

take the necessary steps to ensure their physical protection, we must consider the role of

preservationists in representing the histories and meanings associated with them.

Because meanings and memories are manifested in historic buildings, and historic

buildings are found in landscapes, there is a clear correlation between the role of historic

preservation and memory and identity. According to Rypkema "historic preservation urges

us toward the responsibility of stewardship...of our historic built environment, certainly, but

stewardship of the meanings and memories manifested in those buildings as well" (2005,

10). Hence, preservationists are dually challenged by the social attributes of historic

buildings. They must ensure the physical protection of the built environment and also be

responsible to strive for the accurate representation of the multiple meanings and histories

connected to those physical structures.

The challenge for preservationists involves the representation of multiple forces,

which must address questions of who and why. While historic preservation, on its own, is

a step in the right direction, it is crucial to provide interpretation contextualizing the

building, district or landscape in a period or event to ensure identity and memory is based

on a more cohesive and complete history. In the eyes of Page and Mason,

preservationists have the power to change dominant narratives which falsify history (2004,

18). For example, when minority groups, immigrants, and women are included in

24

preservation endeavors and their stories are told, heritage, and in some sense history,

becomes more representative and inclusive.

The field of preservation is characterized by contested terrains in terms of what

constitutes something worthy of preservation and for whom preservation occurs.

Additionally, there is also the question of the representation and interpretation of heritage;

each of these choices can lead to complex questions surrounding preservation efforts.

Deciding which buildings to preserve and why is constantly debated because choosing

between buildings of architectural grandeur or vernacular character leads to questions of

aesthetics and social inclusion. Dolores Hayden elaborates on this inherent tension within

the preservation field by exploring the arguments made by preservationists with different

notions as to what should be preserved - the grand or the ordinary, the architecturally

significant or the socially important (1997, 4). She thoughtfully recognizes that proponents

of one or the other must be able to see both the downsides and the opportunities

presented by each as one is not necessarily exclusive of the other.

In other words, there can be downsides to preserving for solely social motivations

or for architectural reasons. For example, interpreting and preserving ghettos may lead to

an upsurge in bitter memories, while preserving an architecturally significant structure

without interpretation or public access might lead to questions from taxpayers as to why

their money was spent (Hayden 1997, 5). It does not have to be one versus the other,

grand versus ordinary, because the two can function to illuminate each other's attributes.

For example, preserving vernacular buildings provides the social and economic context in

which architectural treasures were created while, conversely, mansions can be preserved

with the intention to illustrate the skills of tradespeople (Hayden 1997, 5). Despite the

concerns and debates that may arise a common ground exists - the preservation of

landscapes is important whether rooted in aesthetic or social values. Choosing which

places to preserve and for what reasons is a reality of preservation which requires careful

25

interpretation, a commitment to social justice, and a recognition that heritage buildings,

ordinaryor grand, can function to reveal multiple significances.

Social Challenges in the Field of Preservation

Memory is an Important term in the context of preservation. In order to understand

the connections it is necessary to consider two types of memory, social and place

memory. Casey explores these terms:

Social memory relies on storytelling [and]...place memory can be used to help trigger social memory through the urban landscape. Place memory...is the stabilizing persistence of place as a container of experiences that contributes so powerfully to its intrinsic memorability. We might even say that memory is naturally place-oriented or at least place supported (quoted in Hayden 1997, 46).

The preservation of historic places can help citizens define and connect with their past

(Hayden 1997, 46). I believe that historic elements are the ingredients, landscape is the

medium which records and houses history, preservation functions to protect heritage, and

individual and collective memories are the final product. Acknowledging the relationship

between heritage, landscapes, preservation, and memory can be both problematic and

rewarding, and the possibilities presented by these connections result in challenges for

preservationists.

Often, "[h]ow to preserve is as much debated as what to preserve" (Hayden 1997,

54). Inclusivity and representation of minority and ethnic groups call for new and creative

ways of selecting, representing, and contextualizing heritage. We must promote "culture

and ethnic diversity in preservation, [as the need] to find processes for simultaneously

engaging social and architectural history is pressing" (Hayden 1997, 61). By embracing a

more dialogical history, one where both architectural history and public meaning are

acknowledged and appreciated, we are offered the opportunity to represent history in a

more inclusive and meaningful way. Preservation aimed at connecting with the general

populace cannot succeed without collaboration from scholars, the public, governments,

and private agencies.

26

U2-27 Expanding preservation efforts to address issues of inclusivity and representation

requires new relationships which can present barriers. Yet, the outcome can be both

rewarding and cost-effective. Exploring this further, Hayden explains how the participants

in this type of preservation must transcend their traditional roles:

For the historian, this means leaving the security of the library to listen to the community's evaluation of its own history and the ambiguities this implies....It also means exchanging the well-established role of academic life for the uncertainties of collaboration with others who may take history for granted as the raw material for theirown creativity, rather than a creative work in itself....For the artist or designer [it means] seeking a broader audience in the urban landscape than a single patron or a gallery or museum can provide, it means being willing to engage historical and political material....For the public art curator, environmental planner, or urban designer, it means being willing to work for the community in incremental ways, rather than trying to control grand plans form the top down...For the community member or local resident, it means being willing to engage in a lengthy process of developing priorities for a place, and working through their meanings with a group (1997, 76-77).

Ensuring whether or not all participants will embrace or even partake in this type of

preservation is an unknown, and undoubtedly this type of collaboration would be difficult to

implement. The point is, however, that preservation has this potential; it can connect

people with places in many ways which may be more engaging and inclusive of all

residents.

Aspiring to more accurately represent minority and ethnic groups, although a

compelling objective, creates another series of questions that must be addressed by

preservationists. Stipe questions the long-term effects of emphasizing this diversity and

asks whether it "[w]ill...lead to a greater appreciation and acceptance of groups, or...to

resentments and alienation? Will these efforts knit the nation together into a coherent

whole, or...lead to the unraveling of national unity?...[H]ow many approaches can the

nation sponsor and still contribute to a sense of national identity, in addition to group

identity?" (2003, 403). To what degree should or can Canadian municipalities with

ethnically diverse populations define a threshold of inclusivity within their historic

preservation practices? We cannot ignore this heterogeneity and yet the extent to which it

should be included is problematic. Aspiring to be more representative and inclusive of

27

U2-2S diverse histories presents great possibilities for people and for preservation efforts, yet it

also creates questions and responsibilities which cannot be taken lightly by

preservationists.

Conclusion

Distinct connections exist between people and their surroundings. Historic

preservation can function to not only protect these surroundings, but also provide the

interpretation of their architectural and social importance. People's connections with

spaces are both individual and collective, and historic structures and other elements of the

landscape can essentially encapsulate and contribute to individual and collective

memories and identities.

The social considerations associated with historic preservation raise vital questions

that are difficult to answer - what do we preserve; how do we preserve it; for what

reasons; for whom; and what are the implications? Remaining objective when attempting

to answer these questions is a demanding task. It is made more arduous by the under-

representation of minorities in history and the increased presence of new Canadians. On

the one hand, we are given an unparalleled opportunity to tell the untold stories of the

common people and the ability to work collaboratively with other fields in new ways. On

the other hand, scholars question the effects of all-encompassing historic preservation on

national unity.

It seems as though there are no simple answers to the dilemmas presented by

preservation. The subject matter is inherently problematic, but this does not mean that we

should shy away from the potential of historic preservation as a vehicle for public history.

Rather, we could seek for creative ways of engaging with our landscapes all the while

promoting a democratic and inclusive interpretation of heritage. Despite its complexities,

historic preservation remains a powerful vehicle in contributing to people's memory and

identity, and to some degree, social justice.

28