Body Composition and BMI Criterion for Indians related to body fat % by logistic regression"·...

Transcript of Body Composition and BMI Criterion for Indians related to body fat % by logistic regression"·...

Body Composition andBMI Criterion for Indians

A.V. Kurpad

There is a clear link between

body weight, or more specifically highbody mass index (BMI; kg/m2) andthe risk of morbidity and mortality'. Ahigh BMI is associated with severalabnormalities now collectively referredto as the metabolic syndrome2, inwhich insulin resistance with excessive adiposity appears to be the central pathogenic factor. Adiposity isusually inferred from the BMI; however, this may not be sufficient tofully explore relations between bodyfat and alterations in human health. Itwould appear that the body composition, rather than body weight, determines the risk for diseases associ

ated with ageing and other chronicdiseases', as well as mortality3. TheBMI cut-off point that identifies theproportion of people with a high riskof non-communicable diseases (NCD)is a desirable indicator, because itwill provide policy makers with information to initiate prevention programs,and assess the effect of public healthor clinical interventions4.

BMI - DISEASE RELATIONSHIPAND ITS IMPLICATIONS

The inappropriate accumulationof body fat is intrinsic to the development of chronic disease when bodyweight increases. The definition ofoverweight and obesity uses 8MI (25kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2 for overweightand obesity respectively) as the criterion'. This has been adopted globallyby public health, researchers, dieticians and clinicians. There are several questions that need to be answered in this context, however.

For instance, is there a continuumof increasing risk with increasing 8MI,or is there a BMI cut off that determines the risk? The analysis of mostBMI-disease relationship curves willshow that it is difficult to decide on asingle inflection in the relationship,that defines a cut-off; so the WorldHealth Organisation (WHO) Expert Consultation on BMI acknowledged that acontinuum exists4. The next questionis: For what outcome should the 8MIcut-off be used? For example, it is notentirely clear whether 8MI is a reliablepredictor of a mortality outcomes. Otherthan mortality, which is a unique andeasily documented outcome, does the8MI cut-off apply to all other diseaseoutcomes? A recent study of sid, leavein a Belgian workforce suggested thatBMI was not a determinant of daystaken off sick, while waist circumference was6 (Tables 1,2). The questionthen is, does the BMI paradigm referto excess adiposity alone or to thelocation of the fat as well? This was aconcern for the WHO Expert Consultation, which suggested that actionpoints based on 8MI should be refined, where possible, with measuresof central adiposity4. A detailed discussion of the issue of fat location isbeyond the scope of this paper, butbriefly, waist circumference has shownto be a reliable indicator of absenteeism due to sickness6• While some haveshown the waist - hip ratio to be abetter predictor of cardiovascularmortality7 (Figure1), others have shownthat the waist and hip have independent and opposite effects on risk forcardiovascular diseases. Finally, if adiposity is the sine qua non of the 8MI-

disease relationship, is it better tohave body fat cut-offs? The body fatpercentage varies with different racesand ethnicities, as well as with ageand circumstance (Tabte 3); risk evaluations have attempted to define cutoffs for the body fat in relation to themetabolic syndrome9.

When these issues are viewed

through a prism of differing genotypes, phenotypes and hazard exposures in Indian communities (Figure2), the fundamental question still arises:"Is it important to have specific IndianBMI cut-offs?" In order to answer thisquestion, we need to explore the bodycomposition (specifically body fat) toBMI relationship in Indians.

BMI- BODY FATRELATIONSHIP IN INDIANS

Within the cause - effect para

digm of high body fat and propensityfor disease, and bearing in mind theevidence indicating the increase inprevalence of cardiovascular diseaseand diabetes in Indians, it is necessary to demonstrate that Indians havea higher body fat for specific BMIwhen compared to other groups. It

CONTENTS• Body Composition and

BMI Criterion for Indians

1

- A.V. Kurpad

• Foundation News

4

• Integrated Child Development

Services (ICDS)

5

- Prema Ramachandran

• Nutrition News

8

TABLE 1: BMI and sick leave

Men

Age adjusted OR

BMI < 25

1

BMI = 25 - 30

1.12 (1.01-1.25)*

BMI > 30

1.50 (1.30-1.73)*

Women BMI < 25

1

BMI = 25 - 30

1.16 (0.96-1.42)

BMI > 30

1.55 (1.25-2.09)* TABLE 2: Waist circumference and sick leave

Men

Age adjusted OR

Waist

< 94 1

Waist

= 94 - 102 1.13 (1.01-1.26)*

Waist

> 102 1.48 (1.31-1.67)*

Women Waist

< 80 1

Waist

= 80 - 88 1.20 (0.97-1.50)

Waist

> 88 1.55 (1.25-1.91)*

Source: Belstress study, IJO, 2004 Source: Belstress study, IJO, 2004

Superscripts are reference numbers.

DD = Deuterium Dilution. SES = Socioeconomic Status . .4-C = .4Compartment Model.Sngpr = Singapore. Ind. = Indian. UWW = Underwater Weighing.BIA = Bioelectrical Impedance.Methods and Precisions of Measuring Body Fat Vary Across Groups.

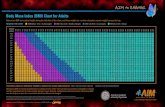

BMI related to body fat % by logistic regression"· multiple regression including age and sex30, andlinear regression2 •• 31. Where relevant, predictions of body fat at particular BMl's were for men orwomen aged 40 yrs

TABLE 3: Percent body fat at pr~sent BMI cut-offsfor overweight and obesity in different groupsMen

Women

Group

Ind.'8Ind.'6Sngpr27 White"Black"Ind.'8Sngpr27White"Black"Low SES

Low I (USA)(USA)Low (USA)(USA)Mid

SESSES n=98

n=141n= 163n=2238n=1211n=89n=160n=2446n=1.417

Method

UWWDD4-CBIABIAUWW4-CBIABIA

Overwt. 25 kg 1m2

243227212229383132

Obesity30 kg/m2

324333292836443737

has been found that for a given 8MI,Indians have more body fat than otherethnic groups, both within and outside Asia10.14(Figure 3). This is important, because measures of overallobesity and the location of body fatare strongly associated with insulinsensitivity in Indians2•13.

This relative increase in adiposity in Indians has led to the suggestion that the 8M I cut-off for non-communicable diseases should be reducedfor Indians'1 and Asians15 to about 23kg/m2 or lower. Recently a convenedWHO Expert Committee concurred butstopped short of actually suggesting

a new 8MI cut-off for Indians, insteadpreferred to refer to it as a publichealth action point at a 8MI of 23 kg/m2 (Figure 4)4. This approach seemsperfectly reasonable to define the burdenof risk of chronic disease in a population, since reducing 8MI cut-off values for overweight and obesity wouldimmediately increase their prevalencerates and therefore, increase publicand clinical awareness. However, is itideal for the long-term prevention ofdisease? If the etiological frameworkof an increased slope of the 8MI body fat is correct, then the criticalpreventive measure would be one thatreduced the slope of this line, ratherthan one that reduced the cut-off onthe pre-existing line. Health professionals are enthusiastic advocates ofweight loss, and at an individual level,this approach will be strengthened bythe reduction of the 8MI cut-off. Recent evidence suggests that body fatis more closely linked to physical activity than energy intake16. In effect,this means that the efforts of healthprofessionals should be directed towards a weight management programthat heavily emphasizes physical activity rather than diet control alone,

FIGURE 1: Cardiovascular disease deaths

3

Women _ WHR (P<0.01)

·····0···· Waist (P<0.051)

_ BMI (P<0.05)

o

02-

~~<tl

N<tl

:I:1-

3Men _ WHR (P<0.001)

·····0···· Waist (P<0.01)

_ BMI (P<0.05)

o

.Q 2-~~<tl

:;j

:I: 1 _

2

t Adiposity

'o'ecUve I PolluUoo Stress ~ other Stress

CHD, Diabetes

At least one riskoccurrence

Risks:• Blood Pressure

• Lipids• Glucose

4.6

>3020-25 25-30

BMI category

<20

FIGURE 3: Risk in Asians: A study in Singapore,looking at CVD risk and 8MI

5

4

o

Behaviour

Physical ActivityDiet

FIGURE 2:

SUSCEPTIBILITY =

Genotype + Phenotype + Environment!Psychological

FIGURE 4: Appropriate body mass index for asian populations

and its implications for policy and intervention strategies

with the goal of the restoration of aphysiologically favorable body composition balance (Figure 5). In thiscase the BMI cut-off becomes lessrelevant, but studies are required toassess if this is hypothesis is correct.This concept is also underlined by ananalysis of all cause mortality rates intwo epidemiological studies, whichshowed that weight loss in individualswho were not severely obese, wasassociated with increased mortalityrates, while fat loss was associatedwith decreased mortality rates17. Theabsolute relevance of the BMI cut-offthen needs to be considered with someskepticism.

SKELETAL MUSCLE: THE"OTHER" PART OF THEBODY COMPOSITION.

It is possible that body compositional factors other than the total body

fat, or its location, may predispose tolowering of insulin sensitivity, particularlyin populations with low levels of obesity. It has been speculated that theinsulin resistance in Indians may bepartly due physiological and structural alterations in muscle linked to a

poor nutritional status2. In a simplerframework, a lower total body musclemass, which has an independent effect on insulin sensitivity and glucosedisposal, could also determine therisk for developing insulin resistance18.Studies on Indians and Asians haveindicated that they have a relativelylow muscle mass'9.20, which is compounded by chronic undernutrition21.In India, a nutritional and lifestyle transition resulting in high fat intakes22,coupled with a low physical activity23,would not only increase total body fatmass. but may also result in a relatively lower body muscle content. This

could also explain the finding thatIndian men with a normal BMI havelower insulin sensitivity when compared to Caucasian men, independent of their body fat content or location24.

The important implication of theassociation of muscle is in terms ofthe BMI reduction aim of preventivehealth messages. Particularly in thecontext of transition societies, it islikely that weight changes in individuals or populations might mask anunderlying or pre-existing low musclemass, which would progress independently as aging occurred in the population25. It is therefore possible thatthe application of a lowered 'healthy'BMI cut-off of 23 kg/m2 to individualsmay lead to both fat and muscle loss,with potentially deleterious consequences for health15. It seems reasonable to propose that an ideal population endpoint would be the achievement of a lower body fat (and a highermuscle) contentfor a given BMI, ratherthan simply a lower BM!. This can

"NO ATTEMPT TO REDEFINE CUT-OFFS" FIGURE 5:

{WHO classification} Underweight

18.5-23: Least risk of diabetes23-25 : Action points for S. Asians25-27.5: Action points for Caucasians27.5.30: Action points for Pacific Islanders

Underweight Obese I Obese II Obese III

Work towards a new slope:

• Change body composition to reflectmore muscle mass;

8MI 22 25

3

only be achieved through the recommendation of higher physical activityand exercise levels in the population.The emphasis on the body muscle tofat ratio represents a paradigm shiftfrom the body fat and BMI relationthat forms the current framework fordefining BMI cut-offs. While the roleof body fat and its location are veryimportant in increasing the risk forNCD, the present paradigm wouldsuggest that in normal to low BMIgroups, attention to body composition, in particular to the muscle mass,as well as the reduction of centraladiposity, is a useful addition to simply lowering the BMI cut-off for health.

The author is Dean and Head, Institute of Popu

lation Health and Clinical Research, Department of

Physiology, St John's National Academy of HealthSciences,Bangalore

References

1. WHO. Obesity: Preventing and managing theglobal epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation.WHO Technical Report Series 894, Geneva, 2000.

2. Misra A., Vikram N.: Insulin resistance syndrome(metabolic syndrome) and Asian Indians. CUff Sci2002,83:1483- 1496.

3. Allison D.B., Zannoulli R., Faith M.S., PietrobelliA., Van Itallie T.B., Pi-Sunyer F.X., Heymsfield S.B.:Weight loss increases and fat loss decreases allcause mortality rate: results from two independentcohort studies. Int JObes 1999, 23:603-611.

4. WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate bodymass index for Asian populations and its implication for policy and implementation strategies. Lancet 2004,363:157-63.

5. Stevens J., Juhaeri, Cai J., Jones D.W.: Theeffect of decision rules on the choice of a bodymass index cut-off for obesity: examples from African American and white women. Am J Clin Nutr

2002, 75:986-992.

6. Moreau M., Valente F., Mak R., Pelfrene E., deSmet P., De Backer G., Kornitzer, M.: Obesity, bodyfat distribution and incidence of sick leave in the

Belgian workforce: the Belstress study. Inti JObes2004, 28:574-582.

7. Welborn T.A., Dhaliwal S.S., Bennett SA: Waisthip ratio is the dominant risk factor predictingcardiovascular death in Australia. Med J Aus 2003,179:580-585.

8. Seidell J.C., Perusse L., Despres J.P., BouchardC.: Waist and hip circumferences have independent and opposite effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Quebec Family Study. Am J

Glin Nutr 2001, 74:315-321.

9. Zhu S., Wang Z., Shen W., Heymsfield S.B.,Heshka S.: Percentage body fat ranges associatedwith metabolic syndrome risk: results based on thethird National Health and Nutrition ExaminationSurvey (1988- 1994). Am J Glin Nutr 2003;78:228-35.

10. Misra A., Sharma R., Pandey R.M., Khanna N.(2001). Adverse profile of dietary nutrients, anthropometry and lipids in urban slum dwellers of north-

ern India. Eur J Glin Nutr 55:727-734.

11. Dudeja V., Misra A., Pandey R.M., Devina G.,Kumar G., Vikram N.K.: BMI does not accuratelypredict overweight in Asian Indians in northernIndia. Br J Nutr 2001 , 86: 105-112.

12. Deurenberg-Yap M., Chew S.K., DeurenbergP.: Elevated body fat percentage and cardiovascular risks at low body mass index levels amongSingaporean Chinese, Malays and Indians. ObesRev 2002,3:209-15

13. Banerji M.A., Faridi N., Atluri R., Chaiken R.L.,Lebovitz H.E.: Body composition, visceral fat,leptin,and insulin resistance in Asian Indian men. J Glin

Endocrinol Metab 1999, 84:137-144

14. Chowdhury B., Lantz H., Sjostrom L. (1996).Computed tomography-determined body composition in relation to cardiovascular risk factors inIndian and matched Swedish males. Metabolism45:634-644.

15. WHO/IASO/IOTF. Redefining obesity and itstreatment. The Asia-Pacific perspective. 2000.

16. Yao M., McCrory M.It, Ma G., Tucker K.L.,Gao S., Fuss P., Roberts S.B.: Relative influence ofdiet and physical activity on body composition inurban Chinese adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003, 77:1409-16.

17. Allison D.B., Zannoulli R., Faith M.S., PietrobelliA., Van Itallie T.B., Pi-Sunyer F.X., Heymsfield S.B.(1999). Weight loss increases and fat loss decreases all-cause mortality rate: results from twoindependent cohort studies. Int JObes 23:603611.

18. Poehlman E.T., Dvorak R.V., DeNino W.F.,Brochu M., Ades P.A. (2000). Effects of resistancetraining and endurance training on insulin sensitivity in nonobese, young women: a controlled randomized trial. J Glin Endocrinol Metab 85:2463

2468.

19. Lee R.C., Wang Z., Heo M., Ross R., Janssen I.,Heymsfield S.B. (2000). Total body skeletal musclemass: development and cross validation of anthropometric prediction models. Am J Clin Nutr 72:796803.

20. Song M.Y., Kim J., Horlick M., Wang J., PiersonJr R.N., Moonseong H., Gallagher D. (2002). Prepubertal Asians have less limb skeletal muscle. JAppl Physiol 92: 2285-2291.

21. Kurpad AV., Regan M.M., Raj T. Vasudevan J.,Kuriyan R., Gnanou J., Young V.R.: Lysine requirement of chronically undernourished adult Indiansubjects, measured by the 24h indicator aminoacid oxidation and balance technique. Am J ClinNutr 2003,77: 101-108.

22. Ghafoorunissa (1998). Requirements of dietaryfats to meet nutritional needs and prevent the riskof atherosclerosis. In J Med Res 108: 191-202.

23. Borgonha S., Shetty P.S., Kurpad AV.: Totalenergy expenditure and physical activity in chronically undernourished Indian males measured bythe doubly labeled water method. Ind J Med Res2000; 111: 24-32.

24. Chandalia M.,Abate N., Garg A., Stray-GundersonJ., Grundy S.M.: Relationship between generalizedand upper body obesity to insulin resistance inAsian Indian men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999,84:2329-2335.

25. Janssen I., Heymsfield S.B. (2000). Skeletalmuscle mass and distribution in 468 men andwomen aged 18-88 yr. J Appl Physiol 89:81-88.

4

FOUNDATIONNEWS

• Clinical Laboratory

NFl has acquired sophisticatedlaboratory equipment, which will enable setting up of a Clinical Laboratory within the institution. This facilitywill help both NFl and CRNSS to expand the scope of their work.

• Study Circle Meetings

29th July 2005: Dr M G Karmarkar(Senior Advisor, ICCIDD, Centre forCommunity Medicine, AIIMS): lodisedDouble Fortified Salt - Is It Feasible?

25th August 2005: Ms Reva Nayyar(Secretary, Ministry of HRD, Department of Women and Child Development): Nutrition and National Development.

28th September 2005: Dr RajeevGupta (Consultant Physician DirectorResearch, Monilek Hospital and Research Centre, Jaipur): Risk Factorsfor Coronary Heart Disease- Lessonsfrom Jaipur.

• Foundation Day

On the occasion of NFl's Foundation Day, Dr Ashish Bose will deliver the C Ramachandran MemorialLecture. Dr Samlee Plianbangchang(RD, WHO, SEARO) will inaugurate atwo-day symposium on "Nutrition inDevelopmental Transition" on November 30th, 2005 at India International Centre, New Delhi. Over 60 leadingscientists are expected to participatein the symposium, the proceedings ofwhich will be published.

• NFl's Publications released

"Anaemia in Pregnancy: Interstate Differences" - The result of thestudy of 7 states of India;

"Combating Low Birth weight andIntra-Uterine Growth Retardation" showing the effect of low birth weightin pregnancy and

"Towards National Nutrition Se

curity" - Proceedings of the SilverJubilee Symposium.

• Annual General Body Meeting

The Annual GBM was held on

September 30th, 2005.

Integrated ChildDevelopment Services (ICDS)

Prema Ramachandran

ICDS is the largest, perhaps oneof the most imaginative, progressiveand ambitious programmes for human resource development to be attempted by any developing country.ICDS aims at improving growth anddevelopment during the critical intrauterine period, infancy and earlychildhood by providing an integratedpackage of the nutrition, health andeducation services right in the vicinityof their houses to both urban and

rural population. The programme wasinitiated in 1975 as a Centrally Sponsored Programme. The Centre bearsthe cost of supporting the infrastructure to implement the programme andthe states bear the cost of food supplements. Over the years, the countryhas built up a massive infrastructurefor implementation of ICDS. The presentcommunication reviews the implementation of the nutrition component ofICDS programme for preschool children in the context of ongoing socioeconomic and lifestyle transition.

TIMES TRENDS IN INFANTFEEDING AND NUTRITION

In India, steps taken for the protection and promotion of the practiceof breast-feeding have been effectiveand breast-feeding is almost universal. However, the message that exclusive breast-feeding up to six monthsand gradual introduction of semisolids after that, is critical for the prevention of under-nutrition in infancy hasnot been communicated effectively.Data from National Family Health Survey - 2 (NFHS-2) indicated thatthoughbreast-feeding was nearly universal

and mean duration of lactation is over2 years, exclusive breast-feeding amonginfants in the age group of 0-3 monthsis only 55.2%'. In spite of the emphasis on the need for timely introductionof complementary food only 33.5% ofthe infants in the age group of 6-9months received breast milk and semisolid food. As a result, there is a steepincrease in under-nutrition between6-24 months1 (Figure 1).

Studies carried out at the National Institute of Nutrition (N IN),Hyderabad have shown that by providing powered cereal and pulse oilseed mixtures, it was possible to improve complementary feeding andnutritional status of infants2. In an attempt to improve appropriate complementary feeding, a nationwideprogramme (Pradhan Mantri GramodayaYojana [PMGY] Prime Minister's ruraldevelopment programme) for providing take-home weaning foods for oneweek to below poverty line (BPL) families, with infants between 7-12 monthsof age, was initiated in 2002-033. Experience gained in the last three yearsindicates that making financial provisions does not result in an increase inthe number of under-three childrengetting food supplements and improvement in timely introduction of complementary feeds. It would appear thatsupplies have to be regular and bebacked up with adequate nutrition andhealth education in the anganwadi inorderto achieve improvement in complementary feeding. Correction of faultyinfant feeding and caring practicesthrough nutrition and health education rather than providing supplements

to BPL families might be the appropriate intervention for prevention of under-nutrition in early childhood. Infant and young children need only atiny fraction of the food available athome to meet their nutrient needs.Data from studies in Karnataka4 haveshown that nutrition education canenable women from low-income groupto meet all the requirements of infantsand young children from food available at home. Strengthening the nutrition and health education component of ICDS can enable other statesto replicate the results reported fromKarnataka and achieve sustainableimprovement in nutritional status ofinfants and young children. The TenthFive-year PlanS has emphasized theimportance of nutrition education andhas set state specific goals for appropriate infant feeding practices. If theseare achieved, it will be possible toachieve the Tenth Five-year Plan goalsfor reduction under-nutrition.

TIMES TRENDS IN YOUNG CHILDFEEDING AND NUTRITION

Surveys carried out by NationalNutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB)have shown that over the last threedecades there has not been any increase in the dietary intake of thepreschool children2. Data on energyintake in preschool children, adolescents and adults from NNMB 2000 areshown in the Table2• Mean energyconsumption, as percentage of Recommended Dietary Intake (RDI) is theleast among the preschool children.This is in spite of the fact that RDI forpreschool children forms a very smallproportion (on an average 1300 Kcal/day) of the family's total intake ofaround 11000 Kcal/day (assuming afamily size of 5).

Time trends in intra-familial distribution offood from NNMB are shown

FIGURE 1: Prevalence ofundernutrition

(Weight for age % below- 250)60

50

40

30

20

10

<6 6-11 12-23 24-35Age-groups

• %-2SD • %-3SD

Source: NFHS-2, 1998-99

TABLE: Mean Energy Consumption-Children I Adolescents and AdultsAge Group

MalesFemales

Kcals RDI

%RDIKcals RDI%RDI

Pre-school

889135765.5897135166.4

School Age 1464

192975.91409187675.1

Adolescent 2065

244184.61670182391.6

Adults

2226242591.819231874102.6

Source: NNMB, 2000.

5

Figure 2: Comparison of Energy AdequateStatus of Preschool Children and Adults

50

,,40Cl

-E30

~20"Cl-10

o

.1975-80 D 1996-97

Dietary AdultAdultPreschoolIntake

MaleFemaleChildren+++

AdequateAdequateAdequate++-

AdequateAdequateInadequate---

naaequatenaaequatenaaequa e

Source:NNMB, 1999

NNMB NFHS

--- Under weight «2 SD) _ Stunting «2 SD)

-0- Wasting «2 S.O)

Source: NNMB, 2001

FIGURE 3: Trends in prevalence (%)of undernutrition in children

~ :I~ I:===tn.

~.n.......n ().~

19

19 1920 1919

75-

88-199496-00- 92-98-

79

90 9701 9399

NNMB

NFHS

FIGURE 4: Trends in prevalence (%)of severe undernutrition in children

;i 60~ 50C 40Q) 30() 20Q; 10a. 0

--- Under weight «3 SD) _ Stunting «3 SD)

-0- Wasting «3 SD)

Source: NNMB, 2001

0--01992-93 1998-991975-79 1988-90 1994 1996-97 2000-01

80

~60CQ)

() 40Q;

a. 20

100

o

in Figure-26. The proportion of families where both adults and preschoolchildren have adequate food has remained at about 30% over the last 3decades. The proportion of familieswith inadequate intake has come downsubstantially but the proportion offamilies where the pre-school childrenreceive inadequate intake while adultshave adequate intake has nearlydoubled. It would, therefore, appearthat economic deprivation or povertyis no longer the major factors responsible for inadequate dietary intake inpreschool children. Lack of knowledge on child feeding, rearing andcaring practices are major factors responsible for the low dietary intake inpreschool children.

Time trends in nutritional statusof preschool children from NNMB andNFHS are shown in Figures 37 & 47•These cross-sectional data indicatethat there has been a 50% reductionin under-nutrition in the last threedecades. The magnitude of reductionmight be higher because during thisperiod there has been a steep fall ininfanta (Figure 5) and under-five mortality and a number of severely undernourished children survived and contributed to an increase in the pool ofunder-nutrition. The reduction in infant mortality rate, under-five mor.tal-

FIGURE 5: Time Trends in IMR140

120

0100o~ 80

'" 60Iii<r 40

20

o

~'o ~'1> 10" 10'" iO'b 9" 9"> 9'0 9'1 9'b 9'1> c<;)c" c",,'1> ,,'1> ,,'lI ,,'?J ,,'lI ,,'lI ,,'lI ,,'lI ,,'lI ,,'lI ,,'lI ••<:J ••<:J •• <:J

Years

__ IMR

Source: SRS, 2003.

ity and severe under-nutrition that thecountry has witnessed in the last threedecades is mainly due to improvedcoverage and impact of ongoing healthinterventions. But it is a matter of concern that even now over 45% of thepreschool children are under nourished1.

Data reviewed so far indicate thatcurrently under-nutrition in preschoolchildren is mainly due to poor intrafamilial distribution offood along withpoor child feeding and caring. Therefore, nutrition education on feedingand caring for the preschool childrenin anganwadi is the appropriate intervention under ICDS to achieve sustainable improvement in dietary intake and nutritional status of preschoolchildren. This should be coupled withscreening of all preschool children atleast once in three months for earlydetection of under-nutrition and providing appropriate health and nutrition care to children with varying gradesof under-nutrition. If this strategy, suggested in the Tenth Five-Year Plan, isoperationalised, it will be possible toachieve substantial reduction in under-nutrition.

PROGRESS UNDER ICDSPROGRAMME

In 1975, the Department of Social Welfare initiated ICDS in 33 blocks.The initial geographic focus of ICDSwas on drought-prone areas; blockswith a significant proportion of scheduled caste and scheduled tribe population, high level of under-nutritionand under-five mortality. Overthe years,there has been a progressive increasein number of blocks covered underICDS programme; in the nineties thenumber of blocks covered nearlydoubled. Currently the programmecovers almost all the blocks in thecountry.

Over the years there has beensubstantial increase in the centralexpenditure on the staff componentof ICDS. The nineties witnessed morethan two-fold increase in the centralfunding for ICDS; partly because ofan increase in the number of anganwadicenters and partly due to an increment in emoluments of the personnelS (Figure 6). The Tenth Plan witnessed a near doubling of the outlaysfor ICDS because of the efforts touniversalize ICDS and an increase inthe honorarium paid to the anganwadiworkers.

The outlay for food supplementsfor ICDS comes from the state budgets. Available information on planoutlays for ICDS during the late nineties indicate that there has not beenany substantial increase on states ownexpenditure for providing additionalfood grains to increasing number ofanganwadis established during the9th Plan. Taking this into account theCentre provided additional centralassistance (ACA) for Nutrition from1996-97 onwards ~initially under Basic Minimum Services (BMS) and laterunder Prime Minister Rural Development Programme. But during this period the states have not increasedtheir outlays for food supplements9

FIGURE 6: ICDS expenses over year0

00'"0

~ ~1000

coco

900

cDex>"''"

800

<Xl...ex>"

M<DcD700

cDr-:0~ 600

<D<Xl<D"' "'

o 500 ~c.;;; 400 ...

<r 300"'

"''"

200"

"'i

MM100

'""~.,;

0<D

<D

~'""<Xl'" (;";' "i'ex> '"'"'"'""' 0.;, "'<b,.:.'"' 6" <Xlex>'"'"'"'"'" 0~ ~~~~~~~ 0'"

Source: Planning Commission, 2002

6

FIGURE 7: Yearwise Nutrition Outlays

••••• Children 0-3 years -.- Children 3-6 years

,C\I

C")'<tLOcoI'-co0>0or-C\I0>

0>0>0>0>0>0>0>0O'0II~ IIIII000

or-C\I '<tLOcoI'-co

C\IC\IC\I0>0>0>0>0>0>0>0>II00>0>0>0>0>0>0>0>0>0

or-or-0r- O>00

0>00

C\IC\I

FIGURE 8: Time Trends in personsreceiving food supplements

5

O+-----.-.--r----.-.--.----.-.------.---,----,

20

E 10c

.§ 15DBM S/PM GY

D State Outlay

(0 I'-coOJ0or-C\IC")

OJOJOJOJ0000I e.b~I0000LO

coC\IN~NOJOJOJOJc:f,0 NOJOJOJOJ ..-

..-..- OJ000

OJ000N NN

1400

1200

(l) 1000

e 800u.~ 600

VJ

0:: 400

200

o

Source: Planning Commission, 2003-04 Source: DWCD, 2002-03

vide practical nutrition educationto women on cooking and feedingyoung children.

However, the on-the-spot feeding programme with hot cooked foodhas several disadvantages such as:

• children especially those in the agegroup of 6-36 months cannot consume the entire amount of foodprovided because of a smaller stomach capacity;

• in older children who do eat the

food provided in the anganwadis,this acts mainly as a substitute,and not an addition, to the homefood;

• the most needy segments, that is,children in the critical 6-36 monthage group and women, who arenot able to come to the anganwadisdo not receive the food;

• providing food supplements onlyto the children from the BPL families or undernourished children

is not possible as it may be difficultto feed one child and withholdfood from the other in the sameanganwadi;

• cooking food, feeding the childrenand cleaning the vessels and theanganwadi take up most of the time

90.9

2.1 6.9MY PDS ICDS MOM

2.6

64.574.8

FIGURE 9: Strategies forcoping with drought

20

o

60 41.0

40

100

80

Source: NNMB, 2002.

programme has been evaluated byseveral agencies including NutritionFoundation of India, National Institutefor Public co-operation and Child Development, Government of India andWorld Bank'o. Some of the major lacunae identified in these evaluations are:

• The norms for funding of ICDSProgramme are uniform. Currentlyit is envisaged that 102 individualsper anganwadi should receive foodsupplements. There is huge difference in the percentage of BPL familiesand birth rates not only betweenstates but also between districts inthe same state. Both these will modifythe number of persons who requirefood supplements in the anganwadi;

• The most needy persons are notidentified and food supplementsare not given according to theirneed;

• Very few anganwadis attempt toscreen all children, identify severelyundernourished children and provide them with double rations asenvisaged in ICDS guidelines;

• The food supply is erratic in manystates. The quality and quantity ofthe food provided also varies;

• The preparations are not tasty andthe food provided is monotonus;

Initially the emphasis was on providing cooked food through on thespot feeding in the anganwadi because it was believed that

• this would ensure that the targetedchild would get food supplements,which would not be shared by othermembers of the family; and

• the anganwadi centres would pro-

EVALUATION OF ICDS

During the last two decades thenutritional component of ICDS

(Figure 7). For the year 2005-06, theoutlay for the Department of Womanand Child Development is over .Rs3500 crores because the entire central funding including central contribution for food supplements has beenrouted through the budget for theDepartment.

Data on time trends in the number of preschool children receivingfood supplement through anganwadireported by the Department of Womenand Child Development are shown inFigure 8'°. It is obvious that the increase in the number of childreneither in the 6-36 months age groupsor 3-6 years age group receivingfood supplements through ICDSduring the nineties is not commensurate with the increase in the number of ICDS blocks.

Data from NNMB surveys indicate that people are aware of the ICDSfood supplementation programme.While they may not use it regularly toimprove the nutritional status of theirchildren, they do use it in times offood scarcity. Drought surveys carried out by NIN have shown that during drought (Figure 9), ICDS programmewas fully utilized by the population tobridge the gaps in food supply, prevent reduction in dietary intake anddeterioration in nutritional status ofpreschool children". It would, thus,appear that the nutrition componentof ICDS is well accepted by the population but it s functioning more as asocial welfare programme rather thana nutrition programme.

7

of the anganwadi workers and helpers, leaving them little time for otherimportant activities such as growthmonitoring, nutrition education andpre-school education;

• in any mass cooking and feedingprogramme, the monotony of thefood provided and relatively poorquality of the preparations is a problem;

• cooking in poor hygienic conditions and keeping left-over foodmay result in bacterial contamination of food;

• under-nourished children, even thosein the 3-6 year age group, if givendouble rations, cannot consumeall the food in one sitting in theanganwadi.

ICDS IN THE TENTH PLAN PERIOD

Taking all these factors into account, the Tenth Plan envisaged thatthere will be a paradigm shift in theICDS programme from untargeted foodsupplementation to screening of allthe persons from vulnerable groups,identification of those with variousgrades of under-nutrition and appropriate management.

There will be focus on:

• strengthening the nutrition and healtheducation component so that basedon the requirement, there is anappropriate intra-familial distribution of food;

• weighing all children in the 0-72month age group at least once inthree months and identify thosewith chronic energy deficiency (CEO);

• focusing health and nutrition intervention (by providing take-homesupplements) to ensure that children in Grades III' and IV undernutrition are in Grade II by the nextquarter;

• looking for and treating health problems associated with severe under-nutrition;

• enhancing the quality and impactof ICDSsubstantially through training,supervision of the ICDS personneland improved community ownership of the programme and

• concentrating on improvementof the quality of care and intersectoral coordination and strengthening nutrition action by the healthsector.

CONCLUSION

In the changing socioeconomicscenario of the country under-nutrition, especially in preschool children,appears to be more due to poor infantand young child feeding and caringpractices rather than poverty and lackof food at home. Nutrition and healtheducation at anganwadi is critical forcorrecting the faulty feeding and caring practices and bringing about significant reduction in under-nutrition inthe preschool children. Investment innutrition and health education will paybetter dividends in terms of sustainable improvement in dietary intake andnutritional status of preschool children.This should be coupled with screening of all children in 0-6 year age groupfor undernutrition and effective healthand nutritional intervention for management of undernourished children.

There has been a long debateon the relative merits of on-the-spotfeeding and take-home supplements.Food sharing appears to be inevitable in take-home supplements whilesubstitution for home meal is the problem with on-the-spot feedingprogrammes. It is, thus, not possibleto ensure that target child gets additional food by either of these approaches. Cost of food grains andpulses to provide 300 kcal of energyand 12 grams of protein is less than50 paise; cooking cost for providingon-the-spot feeding ranges from Rs1.50 to Rs. 3.00/child. It will be possible to cover larger number of children with the same fund allocation iftake-home food grains are providedto the family. Take-home rations willmake it possible to provide food supplementation only to undernourishedchildren. If coupled with appropriatenutrition education, this would enablethe undernourished children to consume all the food, that is, about 600kcalspread over two or more meals.

Currently the available food supplied under ICDS is shared betweenall the persons who come to theanganwadi. The Tenth Plan envisagesthat preschool children will be weighed;those who are having moderate orsevere under-nutrition will be identified. Their families will be given appropriate health and nutrition education and the required take-home foodsupplement. If this strategy is fullyimplemented it might be possible toachieve 50% reduction in severe under-nutrition as envisaged in the Tenth

Plan without massive increase in financial commitment.

The author is Director, Nutrition Foundation 01India.

References

1. National Family Health Survey 1998-99, liPS,Mumbai.

2. Report of the National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau, National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad,2000.

3. Annual Plan. Planning Commission, Government of India 2002-03, New Delhi.

4. Kilaru A, Griffiths PL, Ganapathy S, Ghosh S.Community-based nutrition education for improving infant growth in rural Karnataka. Indian Pediatrics. pp 425; 42(5), 2005.

5. Tenth Five-Year Plan. Planning commission,Government of India, 2002.

6. Report of the NNMB, National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau, National Institute of Nutrition,Hyderabad, 1999.

7. Report of the NNMB, National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau, National Institute of Nutrition,Hyderabad, 2001.

8. Bulletin of Sample Registratfon System, 2003.

9. Annual Plan. Planning Commission, Gal, NewDelhi 2003-04.

10. Annual Report. Department of Women and ChildDevelopment, Gal, New Delhi, 2002-03.

11. Report of the Drought Survey, National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau, National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, 2002.

NUTRITIONNEWS

• NSI Meeting

Thirty-Seventh Annual Conferenceof the Nutrition Society of India will beheld at National Institute of Nutrition,Hyderabad during 18th and 19th November 2005.

Dr Shanti Ghosh will deliverGopalan Oration on "For better healthand Nutrition prioritis.ethe young child.Dr Subhadra Seshadri will deliverSrikantia Memorial Lecture on "IronDeficiency Anaemia and its consequences: A life cycle approach is criticalfor its control".

Two symposia will also be organized at the NSI meet:

i) Biotechnology for better Nutrition

ii) Nutrition Intervention Strategies Role of stakeholders

Edited by Mrs Anshu Sharma for the Nutrition Foundation of India, C-13, Qutab Institutional Area, New Delhi 110 016. website: www.nutritionfoundationofindia.orge-mail: [email protected] Designed and produced by Media Workshop India Pvt Ltd. e-mail: [email protected]