Benjamin Little History

-

Upload

nanka-dolidze -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

0

Transcript of Benjamin Little History

-

8/8/2019 Benjamin Little History

1/8

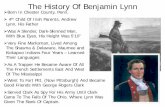

JWalter Benjamin (1892-1940) and WilliamM.lvins, Jr. (1881-1961)Bom in BerUn, Walter Benjamin moved to Switzerland in 1917 toattend the University at Beme. In 1919, he received his diplomaupon the complet ion of his thesis on the concept of art cr it ic ism inGerman romanticism. The following year, he retumed to BerUnwhere he worked on translations of works by Baudelaire andGoethe. Dver the next years, Benjamin devoted himself to the writ-ing of his major work on the history of the German Baroque drama,Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels. During the late 1920s, helaunched his professional career as a Uterary critic and essayist,contr ibut ing art ic les to many European joumals and reviews. Hebecame an ardent Marxist, writ ing cri tiques of modem society de-r iding the moral and intel lectual atti~udes of the middle class. InThe Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, he de-scribes how photography has altered the elitist nature of art worksby enabUng excellent reproductions to be disseminated amongstthe middle and lower classes.

ln 1931 Benjamin pubUshed HAShort History of Photography" inLiterarische Welt, in which he examines people's varied attitudestoward the medium, from its invention to his own time, and invest i-gates the changing influence that photography and the more tradi-tional art media have had on one another over time.Wi/l iam Ivins was also concemed with the interplay of photog-raphy with other art ist ic media. Ivins argues in Prints and VisualCommunication (1953) that, unUke any other reproducible print,the photograph has no syntax of its own - that is, no physicalmatrix inherent only to photographs into which a message is trans-lated and by which it is communicated.

A Short History of PhotographyWa1terBenjaminThe fog which obscures the beginnings of photography is notquite as thick as that which envelops the beginnings of printing.Perhaps more discemible for photography was the fact thatmany had perceived that the hour for the invention had come.Independcntly of aneh other men were striving for the same goa1- fixing th(l pll-tum" mude by a eamera obscura, itself well

199

-

8/8/2019 Benjamin Little History

2/8

-

8/8/2019 Benjamin Little History

3/8

people in the pictures can see him, so staggering in the effect oneveryone of the unaccustomed clarity and the fidelity to natureof the first daguerreotypes."These first to be photographed enter the viewing space un-famed or, rather, uncaptioned. Newspapers, then, were stillitems ofluxury, which one seldom bought but rather looked at incafes. The photographic procedure had not yet become a tool oftheirs; the fewest possible people even saw their names in print.The human face had a silence about it inwhich its glance rested.ln short, all possibilities of this portrait art rested upon the factthat the connection between actuality and photo had not yetbeen entered upon. Many imagesby Hillwere taken at the Edin-burgh cemetery of Greyfriars. Nothing is more representative ofthis early period: it is as if the models were at home in thiscemetery. And the cemetery, according to one picture that Hillmade, is itself like an interior, a delineated, constricted spacewhere gravestones lean on dividing walls and rise out of thegrass floor - gravestones hollowed out like fireplaces showingin their hearts the strokes ofletters instead oftongues offlame.But this place could never have achieved its great effect hadnot its selection been for technical reasons. The lower sensitivityto light of the early plates made necessary a longperiod of expo-sure in the open. This, on the other hand, made it desirable tostation the model as well as possible in a place where nothingstood in the way of quiet exposure. "The synthesis of expressionwhich was achieved through the long immobility of the model,"Orlik says of the early photographs, "is the chief reason besidestheir simplicity why these photographs, like well drawn orpainted likenesses, exercise a more penetrating, longer-Iastingeffect on the observer than photographs taken more recently."The procedure itself caused the models to live, not aut oj theinstant, but into it; during the long exposure they grew, as itwere, into the image.They can be sharply contrasted to the snapshot, which corres-ponds to the changed environment in which, as Kracauer hasaccurately remarked, the same fraction of a second that the ex-posure lasts determines "whether an athlete becomes famousenough for the photographers of the illustrated magazinesto takehis picture."

Everything in these early pictures was set up to last; not onlythe incomparable grouping of the people - whose disappear-ance was certainly one of the most precise symptoms of whathappened to society in the second halfof the century - even thefolds that a garment takes in these images persists longer. Oneneeds only look at Schelling's coat; it enters almost unnoticedinto immortality; the forms which it assumes on its wearer arenot unworthy ofthe folds in his face. In short, everything speaksto the fact that Bemhard van Brentano suspected: "that aphotographer of 1850was on the highest level ofhis instrument"- for the first and for a long time for the last time.ln order to understand the poweDUIeffect of the daguerreo-type in the age immediately following its discovery one mustconsider that the plein air painting of that time had begun toshow entirely new perspectives to the most advanced painters.Aware that even in this area photography had to take the torchfrom painting, Arago said in a historical review of the earlyexperiments of GiovanniBattista Porta: "As far as concems theeffect which depends on the incomplete transparency of ouratmosphere (and which has been labeled with the accurate ex-pression 'air perspective'), the practiced painter does not hopethat the camera obscura" - he means of the copying of theimages that appear in the camera obscura - "could be helpful tohim in reproduciog this effect exactly." At the moment whenDaguerre succeeded in fixing the images in the camera obscurathe painter had been distinguished on this point from thetechnician.The genuine victimof photography, however, was not land-scape painting but the miniature portrait. Things developed soswiftly that as ear1yas 1840most of the innumerable painters ofminiatures had become professional photographers, at first onlyon the sidebut sooo, however, exclusively. At the same time theexperience of their originalprofession came in handy. It was nottheir preparation ioart but in craft to which the highlevel of theirphotographic accomplishmentsmust be credited. Very graduallythis transitional generation disappeared; indeed there seems tohave been a sort of Biblical blessing on those first photog-raphers: Nadar, Stelzner, Pierson, Bayard alllived to ninety or ahundrcd. Flnlllly,however, businessmen from everywhere en-

204 205

-

8/8/2019 Benjamin Little History

4/8

tered the ranks of professional photographers. Later, when re-touchingofthe negative- through which bad painters took theirrevenge on photography - gradually became practiced, a sud-den decline in taste set in. Then was the time when photographalbumsbegan to appear. In the coldest places in the house, onconsoles or gueridons in the drawing room, they were mosttikely to be found: leather covered with metallatches and gilt-edged pages as thick as a finger on which the foolishly draped orembellished figures were distributed - Uncle Alex and AuntRiekehe, Trudy when she was little, Papa in his first semester.And finally to make the same complete, we ourselves: as salonTiroleans, yodeling, hats swinging against painted firs, or assailors, one leg straight and the other bent, as is appropriate,leaning against an upholstered post.The accessories in such portraits, with the columns, balus-trades and little oval tables, recall the time when one had to givethe models points of support so they could remain steady duringthe long exposure. If in the beginning people were satisfied sim-ply with head holders or knee braces, soon additional acces-sories followed, such as were present in famous paintings andtherefore had to be artistic. Next came the columns or the cur-tain. Even in the '60s accomplished men protested against thisjunk. It was said at the time in an English professional journal:"In painted pictures the columns appear plausible, but the man-ner in which they are applied to photography is absurd, for theyusually stand on a rug. But as everyone knows, marble or stonecolumns are not commonly built with carpet as their base." Atthat time arose the ateliers with their draperies and palms, gobe-lins and easels, which stand so ambivalently between executionand representation, torture chamber and throne room, as anearly portrait of Kafka testifies.There in a narrow, almost humiliating child's suit, overbur-dened with braid, stands the boy, about six years old, in a sort ofwinter garden landscape. Palm fronds stand frozen in thebackground. And as if it were important to make these up-holstered tropics even more sticky and sultry, the model holds ahuge hat with broad brim like those Spaniards wear in his lefthand. He would surely vanish into this arrangement were not theboundlessly sad eyes trying sohard to master this predeterminedlandscape.206

This picture in its immeasurable sadness forms a pendant tothe early photographs inwhich people did not yet look out into aworld as isolated and godforsaken as the boy here. There was anaura around tbem, a medium that gives their glance the deptband certainty which permeates it. And again the technical equiv-alent lay close at hand; it was the absolute continuum frombrightest light to darkest shadow. Here, too, the law holds goodconcerning the advance announcement of new acbievements intbe older technology, in that portrait painting - before its de-cline - had produced a unique flourishing of the mezzotint.Tbe mezzotint method involves a technique of reproductionsuch as was united onlylater witb the new photographic one. Asin mezzotints the light inHill's work torturously wrestles its wayout of the dark: Orlik speaks of the "lights holding together"because of the long duration ofthe exposure which gives "theseearly photographs their greatness." And among the contem-poraries of the invention, Delaroche remarked on the "delicate,innovative" impression which "in no way disturbed tbe reposeof tbe masses." So much for the technical conditions of thisauralike impression.Many group pictures in particular retain a fleeting together-ness which appeared for a short while in the plate, before itdisappeared in the orignal subject. It is this breathy halo, cir-cumscribed beautifully and tboughtfully by the now outmodedoval shape of the frame. Therefore these incunabula of photog-raphy are often misrepresented by emphasis on the artistic per-fection or tastefulness in them. These images were taken inrooms where every customer came to the photographer as atechnician of the newest school. The photographer, however,came to every customer as a member of a rising class and en-closed bim in an aura which extended even to the folds of hiscoat or the turn of his bow tie. For that aura is not simply theproduct of a primitive camera. At that early stage, object andtechnique corresponded to each other as decisively as they di-verged from one anotber in the immediately subsequent periodof decline. Soon, improved optics commanded instrumentswhich eompletely eonquered darkness and distinguished ap-pearanCCRaRsharply as a mirror.Tht' "hoh)"l'lIph('f~in the period after 1880saw their task insimullllll1Wlullnllruthl'UlIghall the arts or retouehing, in partieu-

207

-

8/8/2019 Benjamin Little History

5/8

lar through what was calledoffsetting. The conquest of darknessby increased illumination had eliminated the aura from the pic-ture as thoroughly as the increasing alienation of the imperialistbourgeoisie had eliminated it from reality. So a duskier tone,interrupted by artistic reflections, became fashionable, as inJugendstil. Despite the weak light, the pose was always moreclearly defined; its stiffness betrayed the impotence of that gen-eration in the face of technical progress.Thus, what is decisive in these photographs is always the rela-tion of the photographer to his technique. Camille Recht indi-cated asmuch ina niceimage. "The violinist," he wrote, "mustform the tone himself, must seek it, findit quick as lightning;thepianist strikes the key: the tone resounds. Aninstrument is at thedisposal ofthe painter as well as the photographer. The drawingand coloring of the painter correspond to the tone formation ofthe violin; the photographer shares with the pianist a mechanismwhich is subject to laws of limitation that the violinist is not. NoPaderewski willever eam the fameor work the almost legendarymagic of a Paganini."Continuing the comparison, however, there is a Busoni ofphotography, and that is Atget.CBoth were virtuosos but at thesame time forerunners. They hold in common an unmatcheddevotion connected with the highest precision. Even their fea-tures were similar. Atget was an actor who became disgustedwith that pursuit, took off his mask and then went on to strip themakeup from reality as well. He lived in Paris poor and un-known. He gave his photographs away to admirers who couldhardly have been less eccentric than he, and he died having leftbehind an oeuvre of more than 4,000 photographs. BereniceAbbott from New York collected these, and a selection of themhas appeared in a marvelously beautiful volume published byCamille Recht.3Contemporary journalism "knew nothing of the man whomostly went around the ateliers with hispictures, throwing themaway for a few pennies, often only for the price of one of thosepicture postcards, such as showed the sights of the city around1900,beautifully dipped in blue night, with retouched moon. Hereached the pole of the highest mastery; but in the obstinatecapacity of one of great ability who always lived in the shadows,he neglected to plant his flagthere. 80 manymay believe to havediscovered the pole which Atget reached before them."208

ln fact, Atgets Paris photographs are the forerunners of Sur-realist photography, advance troops of the broader columns Sur-realism was able to field. As the pioneer, he disinfected thesticky atmosphere spread by conventional portrait photographyin that period of decline. He cleansed this atmosphere, hecleared it; he began the liberation of the object from the aura,which has been the achievement of the most recent school ofphotography. When Bifur or Varit, periodicals of the avant-garde, were showing mere details under the captions"Westminster, " "Lille," "Antwerp," or "Breslau," a piece ofa balustrade, a bare treetop whose twigs cut across a gas lantern,a stone wall, or a candelabra with a life ringon which the nameof the city is written, they are showing nothing but refinementsof motifs which Atget discovered. He sought the forgotten andthe neglected, so such pictures tum reality against the exotic,romantic, show-offish resonance of the city name; they suck theaura from reality like water from a sinking ship.What is aura? A strange web of time and space: the uniqueappearance of a distance, however close at hand. On a summernoon, resting, to follow the line of a mountain range on thehorizon or a twigwhich throws its shadow on the observer, untilthe moment or hour begins to be a part of its appearance - thatis to breathe the aura of those mountains, that twig. Now tobring things themselves closer - and closer to the masses - isas passionate a contemporary trend as is the conquest of uniquethings in every situation by their reproduction. Day by day theneed becomes greater to take possession of the object - fromthe closest proximity - in an image and the reproductions of animage. And the reproduction, as it appears in illustrated news-papers and weeklies, is perceptibly different from the original.Uniqueness and duration are as closely entwined in the latter astransience and reproducibility in the former. The removal oftheobject from its shell, the fragmentation of the aura, is the signa-ture of a perception whose sensitivity for similarityhas so grownthat by means of reproduction it defeats even the unique.Atget almost always passed by the "great sights and the so-called landmarks." He did not, however, pass by a long row ofboot lasts, or by the Parisian courtyards where from eveninguntil mornil1"hUl1d-wagonsstand in rows and groups; or by theunclearcd tllhl(\1IAndthc uncollected dishes, whichwere there atthc SUl1Il'lllltt hy 'h~ hundrcd thousands all over; or by the

209

-

8/8/2019 Benjamin Little History

6/8

bordello at rue . . . no. 5, whose gigantic five appears in fourdifferent places on the facade. More noticeably, however, almostall of these pictures are empty. The Porte d Arcueil fortificationsare empty, as are the regal steps, the courts, the terrace cafes,and as is appropriate, the Place du Tertre, all empty.Theyare not Ionely but voiceless; the city in these pictures isswept clean likea house which has not yet found its new tenant.These are the sort of effects with which Surrealist photographyestablished a healthy alienation between environment and man,opening the field for politically educated sight, in the face ofwhich all intimacies fall in favor of the illumination of details. Itis plain that this new vision had least absorbed what one wouldotherwise most understandably indulge in - the devalued rep-resentative portrait. On the other hand, the renunciation of thehuman image is the most difficult of all things for photography.The best Russian films taught those who did not know this thatmilieu and landscape only make themselves accessible tophotographers who know how to grasp them in the namelessmanifestations which they take in the face. Even the possibilityof that is conditioned by the subject of the photograph. It was ageneration which had no ambition to go down for posterity inpictures, but rather withdrew in the face ofsuch possibilities intoits living space, somewhat shyly - like Schopenhauer, in theFrankfurt picture of around 1850,receding into the depths of hisarmchair. Just for that reason this generation let its livingspaceenter with it into the picture, but it did not bequeath its graces.Then for the first time in decades the Russian film provided anopportunity to show people in front of the camera who were notbeing photographed for their own purposes. And suddenly thehuman face entered the image with a new, immeasurable signifi-cance. But it was no longer a portrait. What was it?It is the supreme accomplishment of a German photographerto have answered this question. August Sander4 put together aseries of faces that in no way stand beneath the powerfulphysiognomic galleries that an Eisenstein or a Pudovkin re-vealed, and he did so from a scientific standpoint. "His totalwork forms seven groups, which correspond to the existingorder of society, and are to be published in about 45portfolios of12 photos each."d Sander goes from farmers. the earthboundmen, and takes the viewer through alllcvclll ~nd p,'ufessions up210

on one hand to the highest representatives of civilization anddown on the other to idiots. The creator came to this task not asa scholar nor instructed by racial theoreticians or social re-searchers, but, as the publisher says, "from direct experience."The observation is certainly an unprejudiced one, but clever,also, and tender and sensitive in the sense of Goethe's state-ment: "There is a sensitive empiricism which makes itself mostinwardly identical with the object and thereby becomes genuinetheory. " Therefore it is completely in order that an observer likeDoblin struck straightaway onto the scientific aspects in thiswork and remarked; "As there is a comparative anatomy byvirtue of which we come to a conception of nature and a historyof organs, so this photographer pursues comparative photog-raphy and thereby achieves a scientific standpoint above andbeyond that of photographic details."It would be a shame if economic conditions prevented thefurther publication of this extraordinary corpus. To the pub-lisher, however, we can offer a more specific encouragement inaddition to general ones: ovemight, works like those of Sandercan grow into unsuspected actuality. Power shifts, such as weface, generally allow the education and sharpening of thephysiognomic conception into a vital necessity. One may comefrom the right or from the left - he will have to get used to beingviewed according to where he comes from. One willhave to seeothers the same way. Sander' s work is more than a book ofpictures: it is a book of exercises."There is no work of art in our age so attentiV'elyviewed asthe portrait photography of oneself, one's closest friends andrelatives, one's beloved," Lichtwark wrote as early as 1907,andthereby moved the investigation out of the realm of estheticdistinctions into that of social functions. Only from that anglecan it strike out further. It is significant that the debate becomesstubborn chief1ywhere the esthetics ofphotography as art areinvolved, while for example the much more certain social sig-nificance of art as photography is hardly accorded a glance.And the effect of photographic reproduction of works of art isofmuchgreater importance for the function orart than the moreor less artistic figuration or an event which ralls prey to thecamera, Indced the amateur returning home with his mess orartistic photoHfaphsis moregratified than the hunter who comes

211

-

8/8/2019 Benjamin Little History

7/8

back from his encounters withmasses of animals which are use-ful only to the trader. And the day seems to stand before thedoor when there will be more illustrated periodicals for photog-raphers than game and poultry shops. So much for snapshots.But the accents change completely if we turn from looking atphotography as an art to art as photography. Anyone willbe ableto observe how much more easily a painting and above all, asculpture, or architecture, can be grasped inphotographs than inreality. The temptation is to attribute this to the decay of con-temporary artistic perception. But preventing it is the recogni-tion that at about the same time as the formation of the technol-ogy for reproduction the conception of great works waschanging. One can no longer view them as the productions ofindividuals; they have become collective images, so powedulthat capacity to assimilate them is related to the condition ofreducing them in size. In the final effect, the mechanicalmethods of reproduction are a technology of miniaturizationand help man to a degree of mastery over the works withoutwhich they no longer are useful.ff any one of the current relations between art and photog-raphy is clear, it is the unsettled tension which comes betweenthe two through the photography of works of art. Many of thosephotographers who determine the current aspects of thistechnique came from painting. They turned their backs on thatmedium of expression after efforts to put in a clear, living con-nection with contemporary life. The more aware their sense ofthe nature of the times, the more problematic has grown theirpoint of departure. For again, as 80 years ago, photographypicked up the torch from painting. "The creative possibilities ofthe new," Moholy Nagy said, "are mostly discovered slowly,through old forms, old instruments, old structures which arefundamentally injured by the appearance of new things butwhich, under the pressure of the new, emerging things, aredriven up into a last, euphoric flourishing."So, for example, futurist painting delineated the self-destructive, tightly constricted problematic of simultaneity ofmotion, the figuration of the moment in time; and this at a mo-ment when filmwas known but for a long time would still not beunderstood. Just so, one can - with caution vicw a few of thepainters working today in representntivc. ubjcclivc modes

212

(Neoclassicists and veristes) as forerunners of a new, represen-tative, optical figuration which uses only mechanical, technicalmeans." And Tristan Tzara, 1922:"When everything that calleditself art grew palsied, the photographer ignited his thousand-candle-power lamp and step by step the light sensitive paperabsorbed the blackness of a few useful objects. He discoveredthe carrying power of a tender delicate untouched flash, whichwas more important than all the constellations given us to sootheour sight." The photographers who came to photography out ofthe comfort of the plastic arts, not out of opportunistic daring,not accidentally, today form the avant-garde among their col-leagues, because they are to some degree assured by their courseof devdopment against the greatest danger of current photog-raphy, the tendency toward the applied arts. "Photography asart," says Sasha Stone, "is very dangerous territory."When photography has extracted itself from the connectionsthat a Sander, a Germaine Krull, a Blossfeldtgave it, when it hasemancipated itself from physiognomic, political, scientific in-terests - that is when it becomes "creative."Concern for the objective becomes merelyjuxtaposition; thephotographic artists smock makes its entrance. "Spirit, con-quering mechanics, gives a new interpretation to the likenessesof life." The more the crisis of current sodal order expands, themore firmly moments enter into oppositions against each other,the more the creative principle - by nature a deep yearning forvariants, contradiction its father, imitation its mother - is madea fetish, whose features owe their life only to fashionablechanges of lighting. The "creative" principle in photography isits surrender to fashion. Hsmotto: the world is beautiful. In it is

unmasked photography, which raises every tin can into therealm of the All but cannot grasp any of the human connectionsthat it enters into, and which, even in its most dreamy subject, ismore a function of its merchandisability than of its discovery.Because, however, the true face of this photographic creativityis advertising or association; therefore its correct opposite isunmasking or construction. For the situation, Brecht says, iscomplicated by thc faet that less than evcr does a simple repro-duction ql r('(ll/tvCXP"O!lSumcl:hin"IIhuut I'mdily.A photo", 'uph 01'11h'K"lIrr wOI'k.M1 01'Ilw A.H.O. revealsalmost nUlhl"w"l'Ollt Ih,'IH'11I..lIllIlIolIM'hr "t'liI I'I.mlityhas

211

-

8/8/2019 Benjamin Little History

8/8

shifted over into the functional. The reification of human rela-tions, for instance in industry, makes the latter no longer reveal-ing. Thus in fact it is to build something up, something artistic,created. The accomplishment of Surrealism was to havepioneered such photographic construction. A further stage in theopposition between creative and constructive photography isshown by Russian film. It is not too much to say that the greataccomplishments of its directors were only possible in a countrywhere photography did not proceed on impulse and suggestionbut on experiment and instruction. In this sense - and only init- can we stillmake sense today ofthe greeting whichthe roughidealist painter Antoine Wiertz offered photography in 1855:"The fame of our age was born a few years ago: a machinewhich, day in and day out, has been the astonishment of ourthought and the terror of our eyes. Before a century has passed,this machine will be the brush, palette, colors, grace, experi-ence, patience, dexterity, sureness, hue, varnish, sketch, com-pletion, extract of painting. ff you do not believe that thedaguerreotype kills art, well, when the daguerreotype, this giantchild, has grown up, when all its art and strength have beenrevealed, then geniuswillsuddenly slapa hand on the back ofitsneck and call out loud: Here, you belong to me now! We willwork together."How sober, even pessimistic, on the other hand, are the wordsin which Baudelaire, in the Salon oj 1857, two years later, ac-quainted his readers with the new techniques. No more than thepreceding words can they be read without a gentle shift of ac-cent. But while they imply the opposite ofWiertz's words, theyhave kept their good sense as the sharpest rebuke to all theusurpations of artistic photography: "In these lamentable days anew industry has emerged, which has helped not a little instrengthening plain stupidity in its belief . . . that art is nothingother than - and can be nothing other than - the exact repro-duction of nature. . . . A vengefulGod has heeded the voices ofthe crowd. Daguerre is becoming its messiah." And: "If photog-raphy is allowed to help complete art in a few of its functions,then art willbe as quickly ruined and cast out by it, thanks to thenatural alliance which will grow up between photography andthe crowd. It must therefore return to its own duty. which con-sists in being a servant girlto the sciences Hndthl' nrts."214

One thing, however, was not grasped either by Wiertz or byBaudelaire, and that is the direction implicit in the authenticityof the photograph. It will not always be possible to link thisauthenticity with reportage, whose clichs associate themselvesonly verbally in the viewer. The camera willbecome smaller andsmaller, more and more prepared to grasp fleeting, secret imageswhose shock will bring the mechanism of association in theviewer to a complete halt. At this point captions must begin tofunction, captions which understand the photography- whichturns all the relations of life into literature, and without which allphotographic construction must remain bound in coincidences.Not for nothing were pictures ofAtget compared with those ofthe scene of a crime. But is not every spot of our cities the sceneof a crime? every passerby a perpetrator? Does not the photog-rapher - descendant ofaugurers and haruspices - uncover guiltin his pictures? It has been said that "not he who is ignorant ofwriting but ignorant of photography will be the illiterate of thefuture." But isn't a photographer who can't read his own pic-tures worth less than an illiterate? Willnot captions become theessential component of pictures? Those are the questions inwhich the gap of 90 years that separates today from the age ofthe daguerreotypes discharges its historical tension. It is in thelight of these sparks that the first photographs emerge so beauti-fully, so unapproachably from the darkness of our grandfathers'days.

Benjamin's own notes are indicated with numbers, translator'snotes with letters.1. HelmuthTh. Bossert andHeinrich Guttmann,Aus derFruhzeitderPhotographie, 1840-/870. A Volume of Pictures Prom 200 Originals.Prankfurt, 1930.Heinrich Schwarz, David Octavius HilI, der Meisterder Photographie. With 80plates. Leipzig, 1931.2. Karl Blossfeldt, Urformender Kunst. Photographs ofPlants. Pub-lished with an introduction by Karl Nierendorf. 120 plates. Berlin,1930.3. Atgut,PI/(lto}lr(lph.~.ublishodby CamilleRecht. Paris and Leip-zig, 1931.4. AUMIllItIImlrl, /)/1,1'\/ltllt. dl'" /orlt, Btwlin,1930.

215