Bale Parliaments

-

Upload

david-robledo -

Category

Documents

-

view

25 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Bale Parliaments

-

Chapter 4

^00). O n the ^[1999), and, 3e, see Goct/.

^ d have not) i t t a g (2003). r and Wallace Lpolitics, espc- r ionaJ courts

t h o u g h th is

ply, it h a s

r a g e n c i e s

. Bu t w h i l e pny cu l t ura l

' t o s t e er

i s i d era b ly

1 ' s t ruc t ur e '

o l i cy var i e s

a n d (just a s

ve s o n t h e

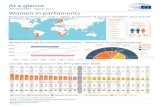

Governments a nd p a r l i a m e n t s : along way from e q u a l i ty

^ ; h e a d of s t a t e >nm m inister, cabinet an d p a r l ia m e n t a r y

government

Permutations o f parliamentary jovemment

tewmment duration an d s t a b i l it y M i n g t h e s p o i l s : 'portfolio a l l o c a t i o n '

Soverning

Parliaments: o n e house or t w o ? Pirliaments: h i r i n g and f irin g Pirliaments: t h e production of law Parliaments: scrutiny an d o v e r s i g h t

i nd g overnment t h e E u r o p e a n le v e l j i i i e t s , power and p ar t ies

hapicr 3 looked at governance, but, in addition Wtojooking at policy-making, it concentrated

m the changing architecture of the state n-elected people who help to run it, be servants or judges. Now we turn to Its - the representative part of the exec-

le elected government in almost all :aro(l|an countries must enjoy 'the confidence of ;irliainent', normally expressed in a vote when it ies rffice - a vote it has to win or, at the very tast, not lose. Europe's parliamentary govern-aentJare led by a prime minister and a group of .olla^es which political scientists call a Cabinet, itekt that cabinet members very often sit in, dinall cases are responsible to, parliament blurs jf distinction between the executive and the legis-.iiure that constitute two parts of the classical m-pan 'separation of powers' that we outlined 3 Chapter 3. This clear division of labour is

:ed sacrosanct by some Americans, yet its in Europe does not seem to exercise many IS. Conversely, Americans see nothing

in the head of state and the head of govern-;ing one and the same person; namely, the

President. However, nearly all European countries,

more or less successfully, keep the two functions separate.

D efinit ion

C a b i n e t , w h i c h m a y b e k n o w n in p a r t i c u l a r

c o u n t r i e s by a d i f f e r e n t n a m e (for i n s t a n c e , in

F r a n c e it is c a l l e d t h e C o u n c i l o f M i n i s t e rs ) is t h e

f i n a l d e m o c r a t i c d e c i s i o n - m a k i n g b o d y in a

s t a t e . In E u r o p e , t h e c a b i n e t is m a d e u p of p a r t y

p o l i t i c i a n s w h o a r e , m o r e o f t e n t h a n no t , c h o s e n

f r o m t h e r a n k s o f M P s a n d a r e c o l l e c t i v e l y (as

w e l l a s i n d i v i d u a l l y ) r e s p o n s i b l e t o p a r l i a m e n t .

I

This chapter begins by looking at the largely attenuated role of the head of state in European countries. I t then focuses on governments, and in particular cabinets. Who and what are they made up of? Do they always command a majority in parliament? How long do they last? How is i t decided who controls which ministry? What do they spend their time doing? Next, the chapter turns to Europe's parliaments. Most European legislatures have two chambers: we look at whether it makes much difference. The chapter then moves on to the basic functions of legisla-tures - hiring and firing governments, making law, and scrutiny and oversight. I t explores whether and why some of Europe's parliaments are weak and some are stronger. The chapter ends by asking why, despite the fact that some parlia-ments are relatively powerful, they are rarely a match for governments.

The head of state

Al l European countries have a head of state. In the continent's monarchies (Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Spain and the UK) , the head of state wi l l be the king or queen. In

81

-

8 2 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

B O X 4 . 1

Monsi eur le Pres iden t : Franc e 's ex ecu t ive he ad of st a t e

Under France's 'semi-presidential ' system (see Elgie, 1999), the president has executive (and especially emergency) powers that go wel l beyond those given t o other heads of state in Europe. Not only is he head of the armed forces and the negot ia tor of internat ional agreements, he can also dissolve par l iament for fresh elections w i t h o u t consul tat ion and can call a re fe rendum on policy put forward by par l iament or the gove rnment . Very o f ten , he is also in charge o f domest ic policy - but not always. As in most other European countr ies, the French presi-dent appoints a pr ime minister w h o must c o m m a n d the conf idence o f the lower house of par l iament, I'Asse m blee Nationale . The pr ime minister and cabinet ministers are then collectively and ind i v idu-ally responsible t o par l iament, wh i ch is wha t di f fer-entiates semi-presidential f r om fu l l-b lown presidential systems. This means tha t French presi-dents can exercise any th ing like ful l executive power on ly w h e n the pr ime minister and cabinet are d rawn f r o m his or her o w n party, or (as is of ten the case in France) alliance of parties. Since the mid-1980s there have been several periods (1986-88, 1993-95, 1997-2002) where this has not been the case, ob l ig ing the president t o 'cohabit ' w i t h a pr ime minister and cabinet d rawn f rom a party or parties on the other side o f the polit ical fence. While the tens ion and conf l ict arising f r o m cohabita tion has not always been as bad as it m i g h t have been, the s i tuat ion certainly obl iges the popular ly elected president t o take more o f a back seat - t h o u g h less so in fore ign and defence policy and d ip lomacy than in domest ic policy. Now that French presiden-tial elections have been re-timed t o take place every five years, and in all l ike l ihood just before parl ia-mentary elections, it may be that cohabita tion becomes much more rare.

republics, it wi l l be a president, either elected directly by the people (as in Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, France, Ireland. Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia) or 'indirectly' by the parliament. The title of 'president', however, does not mean the post holder is, like the US President, both head of state and head of government. In Europe with the sole exceptions of Cyprus (where the govern-ment is fully presidential) and France (where it is 'semi-presidential', see Box 4.1) - the two roles are kept s^arate. Outside France and Cyprus, Europe's presidents, like Europe's monarchs, do not wield executive power but are instead supposed to be above day-to-day politics. As such, they are trusted not just to represent the state diplomatically but also neutrally to carry out vital constitutional tasks such as the official appoint-ment of a prime minister as head of government, the opening of parliament and the signing of its bills into law.

It is tempting to write off Europe's presidents and monarchs as playing a merely legitimating and/or symbolic role. They are a reminder to people (and, more importantly, to elected govern-ments) that, underneath the cut and thrust of inevitably partisan politics, something more steady and solid endures. And, like the flag and certain unique traditions, they can be rallied round by all sides in times of trouble. But heads of state -particularly when elected - do constitute an alter-native locus of potentially countervailing power that can constrain the actions of governments seeking to push their mandates a litde too far or promote their friends inappropriately: examples would include refusing to ratify the appointment of an unsuitable candidate to a ministerial post, delaying the signing of legislation or petitioning a constitutional court to examine it.

This countervailing power - often as much to do with words as deeds - is supposed to be used spar-ingly and for the good of the country. But it does leave those heads of state who use it open to the accusation that they are simply trying to under-mine or obstruct an elected government with whom they (or their party) have policy disagree-ments. This happened early on in several postcom-munist countries, notably Poland, Hungary and Romania. In recent years, however, the situation

appears to have resolved itself in favour of the elected parliamentary government. Poland's 1997 constitution, for instance, significantly scaled back or curtailed the powers of the president as regards vetoing legislation and dissolving parliament. Not that the spats in the region have stopped completely: Vaclav Klaus, for instance, was prime minister of the Czech Republic from 1992 to

-

G O V E R N M E N T S A N D P A R L I A M E N T S 8 3

B O X 4 . 2

The Italian pres idency comes into its own

The scandal-fuelled collapse of the Italian party systenn in the 1990s left a vacuunn that the country 's presidents stepped in t o f i l l . As his o w n Christian Democrat ic Party imp loded , President Francesco Cossiga earned himself a reputa t ion for ou tspoken-ness and even overstepping the mark. He made it clear that , like the publ ic , he t h o u g h t l i tt le of some of his fe l low pol it ic ians and suppor ted electoral system change and fresh elections. He then surprised people by s tepp ing d o w n early. His successor, Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, played an even bigger role: in 1994 he refused t o dissolve parlia-men t at the request of Silvio Berlusconi (whose first a t t e m p t at be ing pr ime minister ended after just a few months) , hav ing earlier prevented h im f rom appo in t i ng his choice of Minister o f Justice. Scalfaro consequent ly wen t on t o appo in t a non-party ' tech-nocratic ' admin is t ra t ion wh i ch lasted just over a year unt i l it was no longer able t o c o m m a n d the suppor t o f par l iament. Scalfaro was succeeded by former central banker. Carlo Azegl io Ciampi in 1999. Ciampi, too , has not been content s imply t o sit back. When Berlusconi became pr ime minister again, Ciampi imi ta ted his predecessor by ob jec t ing t o a proposed ministerial appo in tmen t . In December 2003, he provoked the outrage of Berlusconi by exercising his r ight t o veto a bil l passed by parl ia-men t wh i ch many c la imed gave Berlusconi corfe b l a n c h e for a media m o n o p o l y in Italy (see Chapter 7). He was, however, const i tut iona l ly barred f r om ve to ing the bil l a second t ime whe n a sl ightly amended version was passed in Apri l 2004.

1997, during which time he had to put up with what he regarded as unwarranted interference and sniping from the much respected former dissident, Vadav Havel. In 2003, after rehabilitating himself from the corruption scandals surrounding privati-zation that led to his fall from office, Klaus became Czech president, since when he has been more than happy to let people know when he disagrees with the government! Verbal sparring aside, there is no doubt, though, that in times of crisis, the role of president can be especially important - and can be far more influential than a quick glance at its limited formal powers would suggest (Box 4.2).

Prime minister, cab inet and parliamentary government

In all European states except France and Cyprus, the person formally charged with the running of the country is clearly the prime minister. He or she is normally the leader of (or at least one of the leading figures in) a political party that has suffi-cient numerical strength in parliament to form a government, whether on its own or (more usually) in combination with other parties.

Because of this relationship with parliament, European prime ministers arguably enjoy less autonomy than, say, an executive who is also head of state, such as the President of the US. This is not to say they are powerless. Far from it. Prime minis-ters may well have a great deal of say in the appointment of their cabinet - the group of people who are tasked both with running particular ministries and co-ordinating government policy as a whole (see Blondel and Miiller-Rommel, 1997). Moreover, the fact that they typically chair cabinet meetings means that they can wield considerable influence on what cabinet does and does not discuss, as well as over the conclusions and action points emerging from those discussions. Ultimately, too, most of them have the power to hire and fire cabinet colleagues, the exceptions being the Dutch and French Prime Ministers. The latter, though he can force ministers to resign, can also have ministers all but forced on him i f operat-ing under a president from the same party.

In general, prime ministers also have power-bases in their party and may be so popular with the

general public that ministers dare not risk deposing such a figure, even i f they feel that his or her treat-ment of them verges on the dictatorial. Ministers are also at a comparative disadvantage because it is the prime minister, by dint of his or her co-ordinating function, who knows - in as much as any one person can know - what is going on across the whole range of government activity. This does not necessarily allow the prime minister to inter-fere as much as he or she might like to in the busi-ness of the ministry - indeed, in Germany, for instance, there are strict conventions precluding

-

8 4 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

B O X 4 . 3

The Ne ther l ands ' non -par l i a men t ary ex ecu t ive

In the major i ty o f European countr ies, ministers are also parl iamentarians, t h o u g h in only a few (the UK and Ireland are g o o d examples) do they, in effect, have t o be. The Netherlands, like France, Sweden and Norway, is more unusual in the sense that , there, members o f the Tweede Ka m er are cons t i tu-t ional ly ob l iged t o give up their seats once they become ministers. Their place is taken by subst i-tutes f r o m thei r o w n party so as to mainta in the balance of party power in par l iament. They can still appear in par l iament t o answer quest ions - and do so much more f requent ly than their cabinet coun-terparts in the US, for example. Interestingly, t h o u g h , this formal ly enhanced separation between executive and legislature seems t o d o l i t t le t o increase the wi l l ingness o f the latter t o stand up t o the former : the Tweede Ka m er is not seen as one of Europe's more assertive legislatures.

such interference, notwithstanding an equally powerful convention (also included in Germany's, constitution, the Grundgesetz or 'Basic Law') concerning the Chancellor's right to set the overall direction of government policy. But the prime minister's overview does allow him or her to play one minister (or set of ministers) off against another. His or her prominence in the media may also be a source of power, and is one more thing that leads some to argue that European countries are undergoing what they call 'presidentialization' (see Poguntke and Webb, 2004).

Notwithstanding all this (and to a much greater extent than is the case with an executive president) a European prime minister must also engage in collective decision-making with his or her cabinet - even i f this often takes place outside and prior to the cabinet formal meeting which is then used simply to formalize decisions. Ultimately, he or she cannot function (or, indeed, continue in office) without its collective consent to his or her being primus inter pares or 'first among equals'. In as much as it exists in its own right, then, 'prime ministerial power' is constrained not just by contingencies of time and chance and personality, but the multiple and mutual dependencies between the prime minister and his or her cabinet.

This is not to say, of course, that the extent of this interdependence is the same in all European countries (see King, 1994). I t clearly varies accord-ing to political circumstances: for example, Polish prime ministers have frequently been far more than primus inter pares because they (and their staff) were the anchor in what (in the postcommunist period) have often been highly unstable cabinets; yet on one or two occasions they have been merely the frontmen for the party leadership (Sanford, 2002: 156, 161-2). Historical tradition and how much control a prime minister has over govern-ment appointments are also crucial. The U K prime minister, presiding over a single-party government and armed with the traditional prerogatives of the Crown, is more powerful, for instance, than his or her Dutch counterpart. This is because the latter is hemmed in by both a closely worded coalition agreement with other parties and a tradition of ministerial equality.

The relative lack of personal autonomy enjoyed by the prime minister of a European country.

however, has its upsides. Compared to, say, a US President whose hold over the legislature may be tenuous or even non-existent, the prime minister and the cabinet o f a European country can gener-ally feel confident that their decisions wi l l , where necessary, be translated into legislation. European governments are, above all, party and parliamen-tary governments. The political face of the execu-tive more or less accurately reflects the balance of power between the parties elected into the legisla-ture and wi l l often (though not always) be a multi-party coalition. The ministers who make up the cabinet formed from that coalition may or may not be MPs (Box 4.3). But they are there first and fore-most because they represent a political party whose presence in the government is required in order to secure an administration able to commancT- at least for the time being and on crucial pieces of legislation (such as budgetary matters) - what is routinely referred to as 'the confidence' of parlia-ment. Although confidence is understood by most people in 'Anglo-Saxon' or 'majoritarian' democra-cies such as Britain (see Lijphart, 1999) to mean a stable majority of the MPs in parliament, this is by no means always the case.

-

G O V E R N M E N T S A N D P A R L I A M E N T S 8 5

Table 4.1 W h i c h t y p e o f g o v e r n m e n t o c c u r s

most often In w h i c h c o u n t ry , 1 9 4 5 - 2 0 0 3 ^

Single - party Minim al Minority Oversi z ed m ajority winning govern m ent coalit ion

coalit ion

(%l (%l (%l (%l UK Germany Sweden France (100) (70) (70) (70)

Netherlands^ Italy (50) (60)

Netherlands^ (50)

Notes: 1 Figures rounded to the nearest 10 per cent.

2 Note that the UK had one very brief single - party minority government in the 1970s. 3 The Netherlands appears twice because it has had almost as many minimal winning as oversized coalitions.

Source: Calculated from Gallagher, Laver and Mair (2001) and author's own records of governments post - 1999.

Many European governments do indeed command such majorities, some even when they are made up of just one party. But, as Table 4.1 shows, a significant number qualify as minority governments, i.e. administrations made up of one or more parties which together control less than half (plus one) of the seats in parliament. Such a prospect would be anathema in some countries, inside as well as outside Europe. But in others it is a far from frightening prospect. To understand why, we need to look a little deeper into the process of government formation.

Permutations of parliamentary government

Minimal (connected) winning coalitions

Few political scientists, even when conducting thought experiments, think of democratic polit i-cians as purely 'office-seekers', interested in power either for its own sake or because of the personal profile, wealth, comfort and travel opportunities it can bring them. However reluctant the fashionably cynical among us might be to acknowledge it, the fact is that most people prepared to represent a

political party are also 'policy-seekers'. They want to see some real progress (however limited) made toward realizing their vision of the good society. Even i f we forget all the other aspects that may be involved (from the psychology of bargaining to the personal relationships between party leaders), this dual motivation is enough to ensure that govern-ment formation is very rarely simply a matter of putting together what political scientists call a minimal winning coalition. True, around one in three governments in postwar western Europe have been minimal winning coalitions, while only around one in ten have been single-party majori-ties. But most of these coalitions have also been what political scientists call minimal connected winning coalitions (see Table 4.2 for an example).

Given that in most countries such a coalition would be theoretically, and often practically, possible, how then do we account for the fact that so many parties in Europe hold office, either singly or together, as minority governments? In fact, the answer is quite simple: they do it because they can.

Minority governments

In some countries minority government is difficult, i f not impossible. These are countries that operate what political scientists call 'positive parliamen-tarism'. This refers to the fact that their govern-ments have to gain at least a plurality (and sometimes a majority) of MPs' votes before they

D efinit ion

A m i n i m a l w i n n i n g c o a l i t i o n is a g o v e r n m e n t

m a d e u p o f p a r t i e s t h a t c o n t r o l a s n e a r

t o j u s t o v e r h a l f t h e s e a t s in p a r l i a m e n t a s

t h e y c a n m a n a g e in o r d e r t o c o m b i n e t h e i r

n e e d t o w i n c o n f i d e n c e v o t e s w i t h t h e i r

d e s i r e t o h a v e t o s h a r e m i n i s t e r i a l p o r t f o l i o s

b e t w e e n a s f e w c l a i m a n t s a s p o s s i b l e .

M i n i m a l c o n n e c t e d w i n n i n g c o a l i t i o n s a r e m a d e u p o f p a r t i e s w i t h a t l e a s t s o m e t h i n g in

c o m m o n i d e o l o g i c a l l y , e v e n if g o v e r n i n g

t o g e t h e r m e a n s h a v i n g m o r e p a r l i a m e n t a r y

s e a t s t h a n w o u l d b e s tr i c t ly n e c e s s a r y a n d / o r

c o u l d b e f o r m e d by d o i n g d e a l s w i t h l e s s

l i k e - m i n d e d p a r t i e s .

-

8 6 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

T a b l e 4 . 2 A m i n i m a l c o n n e c t e d w i n n i n g c o a l i t i o n : t h e N e t h e r l a n d s

SP GL Pvd A D 6 6 C D A WD LPF CU SGP

.Left Left/Green Soc.Dem (Soc) Lib Ch. Dem (Neo) Lib Far-right Rellg. Relig.

9 8 4 2 6 44 28 8 3 2

Notes: 1 Shading indicates government. 2 Seats required for overall majority = = 76 (eg PvDA, D66, WD ) .

are allowed to.take office - something that is normally testea in what is called an 'investiture vote' on a potential government's policy programme and cabinet nominations. Examples include Germany, where minority government is made less likely still by a rule that insists that no government can be defeated on a vote of no confi-dence once it has been allowed to form unless the majority voting against it is ready to replace it immediately wi th another government. Other examples of countries insisting on investiture votes include Belgium, Ireland and Italy. So, too, do Poland and Spain which, like Germany, have a 'constructive' vote of confidence, where a successor government has to be ready to take over before one can be called. But Spain also reminds us that 'poli-tics' can often trump 'institutions': after the 2004 general election, the social democratic PSOE managed, in spite of the rules and conventions, to construct a minority government!

Other European countries, however, are charac-terized as operating 'negative parliamentarism'. Governments do not need to undergo an investi-ture vote or, i f they do (Sweden, where the prime minister rather than the government has to step up to the plate, is an example), they are not obliged to win the vote, merely not to lose it. In other words, they can survive as long as those voting against them do not win over half the MPs to their cause. Likewise, the government has to be defeated rather

D efinit ion

A m in o r i t y g o v e r n m e n t is m a d e u p o f a p a r t y

or p a r t i e s w h o s e MP s d o n o t c o n s t i t u t e a m a j o r -

ity in p a r l i a m e n t b u t w h i c h n e v e r t h e l e s s is a b l e

t o w i n - or a t l e a s t , n o t l o s e - t h e v o t e s o f c o n f i -

d e n c e t h a t a r e c r u c i a l t o t a k i n g o f f i c e a n d / o r

s t a y i n g t h e r e .

than actually win on motions of no confidence. This makes it much easier for minority govern-ments to form and to stay in power once they have formed. I t therefore comes as little surprise that a list of countries operating negative parliamentari-anism includes (as well as Finland, Portugal and the UK) , countries such as Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, where minority government has, since the 1970s, become the norm.

These countries are all the more likely to experi-ence minor i ty government because elections, historically anyway, have often produced what political scientists refer to as 'strong' parties. These may well be the largest party in the parlia-ment. Moreover, they are 'pivotal' in the sense that any minimal connected winning coalition would have to include them, and would, i f you filled all the seats in parliament in left-right order, have one of its MPs occupying the middle seat (and therefore known in the jargon as the 'median legislator'). Pivotal parties are always at an advan-tage, even i f they are not large: for example, the liberal FDP in Germany managed to turn its posi-t ion midway between the Social Democrats and the Christian Democrats into almost thirty-one years o f government in the forty-nine years between 1949 and 1998. But when a pivotal part)' is also parliament's largest, it is often in a great position to run a minority government. This is particularly the case when, as in Scandinavia, parties on their immediate flank (say, ex-commu-nist or green parties in the case of the social democrats or'a far-right or zealous market-liberal I party in the case of the conservatives) would not I dream of teaming up in government with parties I

,on the other side of the left-right divide or bloc | Unless these smaller, less mainstream parties arc I will ing to increase what political scientists refer to I as their 'walkaway value' by, say, threatening toj

-

G O V E R N M E N T S A N D P A R L I A M E N T S 8 7

Tab le 4.3 A m i n o r i t y g o v e r n m e n t : S w e d e n

V MP SAP C FpL K M

Left Green Soc. Dem Centre Liberal Ch. Dem Conservative

30 17 144 22 48 33 55

Notes: 1 Shading indicates government. 2 Seats required for overall majority = 175.

support the other side or precipitate a new elec-tion, they t ^ o m e , in effect, 'captive parties', whose support (or, at least, abstention) in confi-dence motions can be pretty much guaranteed (see Table 4.3).

In any case, life as what political scientists refer to as a 'support party' rather than a coalition partner, might suit all concerned. This is especially the case if it involves (as it increasingly does in Scandinavia) some kind of written contract - an understanding that may fall short of a full-blown coalition agree-ment but provides some promises on policy and consultation (see Bale and Bergman, forthcoming). The bigger party can still be in government and affect a 'respectable' distance from what might be a rather distasteful bunch of extremists. The smaller party can go into the next election hopefully combining a claim to contributing to political stability with a claim not to be responsible for all those things the government did that voters disliked! That election, or fiiture elections, may deliver them more seats by which time they wi l l not only be more experienced but better able to drive a hard bargain with a potential coalition partner.

There is another reason why minority govern-ments are more common than we might first suppose, and more common in some countries than in others (see Strom, 1990). I t is that in some systems being ' in opposition' is not nearly so thankless a task as it is in others, notably the UK. As we go on to show, some parliaments - particu-larly those with strong committee systems - offer considerably more scope for politicians whoset parties are not in the government to influence pohcy and legislation. Again, it is the Scandinavian countries that experience frequent minori ty government where this so-called 'policy influence differential' between government and opposition is

smallest. Finally, it is probably also the case, that once a country has experienced minority govern-ment on a number of occasions and has lived perfectly well to tell the tale, it is more likely to embrace the possibility in the future.

In short, the tendency toward minority or majority government has to be seen as cultural, as well as mathematical. There are few institutional barriers to minor i ty government in the Netherlands, for instance: even though the government has to get parliament to approve the often very detailed policy agreement the coalition parties spend months negotiating, there is no formal investiture vote, for example. Yet minority government continues to be almost unthinkable to the Dutch - possibly a hangover from the histori-cal need to form governments that were suffi-ciently broad-based to include representatives of both the Protestant and Catholic churches that traditionally were so important to people's iden-tity. Conversely, and rather uniquely in a PR system, Spain's two main political parties seem to be so wedded to the idea of single-parry govern-ment that, i f it also means minority government, then so be it! This almost certainly has something to do with not wanting to court accusations that they are 'selling out' the unity of Spain to the regional parties with which they would have to coalesce in order to form a majority administra-tion. Cultural 'hangovers' and cultural realities also help to explain a tendency in some countries toward the last type of parliamentary government, oversized or surplus majority coalitions.

Oversized or surplus majority coalitions

The traditional home of oversized or surplus majority coalitions in Europe is Finland. Because of its delicate proximity to the old Soviet Union,

-

8 8 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

sized coalitions can turn out to be the best, or even the only, option. A case in point is Belgium. There, the contemporary need to ensure a balance of parties from both the Dutch- and French-speaking communities may make oversized coalitions increasingly necessary. But other classic 'institu-tional' reasons also come into play: the federaliza-tion of the country we explored in Chapter 2 requires two-thirds votes because it entails changes to the constitution. This reminds us that a

the c i^ntry got used to putting a premium on country's 'preferred solution' to government national unity, on consensus and on including the formation can change over time as institutions and left so as not to anger its bigger neighbour. So cultures change. Another example of the latter is entrenched was the mindset that, unti l 2000, legis- the Netherlands. True, it still prefers majority lation that in most countries would have required governments, but as the differences have blurred only a simple majority in parliament required two- between religious and ideological groups - differ-thirds of MPs to vote for it. In Italy, too, there were ences that traditionally encouraged broad-based institutional reasons for oversized coalitions. Unt i l coalitions - then the country has moved from parliament stopped voting - at least, routinely - by preferring oversized to minimal winning coalitions: secret ballot, governments needed a stockpile of prior to 1975, the latter made up only one-fifth of extra votes because they could not trust enough of postwar Dutch governments; after 1975, over rwo-their highly factionalized MPs to toe the party line! thirds (see Keman, 2002: 230). The tradition of including more parties than a coalition really needs also built up over decades during which the main aim of most parties was to Government duration and Stability stand together in order to prevent the Communist Party sharing power. I t wi l l probably take longer to Much of the fear of minority government in coun-die, not least because a new electoral system tries wi th a more or less institutionalized preference encourages parties to do deals with each other for majorities results from the conviction that it is before elections that need honouring afterwards, somehow less stable. In fact, this does turn out to which is why the centre-right coalition that took be the case, but with important qualifications. A power in 2001 was bigger than it needed to be. useful rule of thumb is that single-party majority France's electoral system, though different, encour- governments last longest, generally one year more ages similar behaviour and that country, too, looks than minimal winning coalitions and twice as long likely to sustain its tendency toward surplus major- as minor i ty governments. Also important, ity government (see Table 4.4). however, is the ideological affinity or 'connected-

None of this is to suggest, however, that such ness' of the various parties that go to make up a governments are impossible or even unlikely in government. A government composed of those other countries. Under certain circumstances over- who are politically close wil l be more stable than

T a b l e 4 . 4 A n o v e r s i z e d o r s u r p l u s m a j o r i t y g o v e r n m e n t : F r a n c e

PCF Verts PS UPM UDF O ther

Left Green Soc. Dem. Conservative Liberal Various

21 3 140 357 29 27

D efinit ion

O v e r s i z e d o r s u r p l u s m a j o r i t y c o a l i t i o n s a r e g o v e r n m e n t s t h a t c o n t a i n m o r e p a r t i e s t h a n a r e

n e e d e d t o c o m m a n d a m a j o r i t y in p a r l i a m e n t , t o

t h e e x t e n t t h a t if o n e (or p o s s i b l y m o r e t h a n

o n e ) p a r t y w e r e t o l e a v e t h e g o v e r n m e n t , it

m i g h t still c o n t r o l o v e r h a l f t h e s e a t s in t h e l e g i s -

l a t ur e .

Notes: 1 Shading indicates government. 2 Seats required for overall majority = 289.

-

G O V E R N M E N T S A N D P A R L I A M E N T S 8 9

one which is not. Nor, of course, should we forget the influence of institutional rules. For instance, the rules we have already mentioned on votes of no confidence are bound to make a difference. Governments wi l l often last longer where these are hard to lose or (as in Germany, Spain and Poland with their 'constructive' confidence votes) hard to stage in the first place. O n the other hand, political culture or system traditions are also important. For example, minority governments in Sweden and Norway last longer than minority governments in Italy or Belgium. Also important is the existence or absence of comprehensive and more-or-less binding coalition agreements. In some countries (for example, the Netherlands) these work well. In others where they are uncommon (such as Italy) they might actually undermine stability by remov-ing the flexibility that particular system seems to demand.

Another qualification is that the 'durability' of European governments to some extent depends on the number of parties that actually make up (or potentially could make up) a coalition. A parlia-ment with a large number of small parties present-ing each other (and larger parties) with multiple options can mean that relatively minor shocks caused by policy or personality conflicts are enough to precipitate a collapse of the government. This is especially the case when such a collapse does not necessarily entail fresh elections. Al l this holds true for Italy, and explains in part, why (until very recently when governments have begun to last longer) it has 'enjoyed' so many more governments than other European countries. O n the other hand, Italy's impressive postwar economic performance suggests there is no easy relationship between apparent 'instability' and poor (or at least socio-economically unsuccessful) government!

Dividing the spo ils: 'portfolio allocation'

Putting together a coalition, of course, entails coming to some agreement both on policies and on the division of ministerial rewards. 'Who gets what, when and how?' is one of the classic political questions, and no more so than when it comes to what political scientists call 'portfolio allocation' -

deciding which party gets which ministries. Except in the case of single-party governments, which in Europe tend to be the exception rather than the rule, this happens in two stages. First, the parties haggle over which ministries and departments they wi l l occupy in the coalition cabinet. Next, they decide who in the party wi l l take up the portfolios they manage to get. Actually, of course, the two stages are not quite so separate: which ministries a party wants may well be conditioned in part by the need to accommodate particular politicians.

In theory, there are basically two methods governing the first stage of portfolio allocation: according to bargaining strength or according to some kind of rule of proportionality. In the first instance, parties that are part of the coalition can use their importance to that coalition as leverage wi th which to gain the highest number of seats around the cabinet table as possible - even i f this number is disproportionate to the number of MPs they bring to the government benches. The other way is simply to give each party in the coalition the number of cabinet places that best reflects the proportion of MPs wi th which it provides the coalition. For instance, a party which provides 30 per cent of the MPs on the government benches should entide it to claim around a third of the cabinet positions.

In the real world, both these systems of alloca-tion operate, but other factors come into play as well. For instance, it is often the case that certain parties have certain favourite ministries. For example, a party representing agricultural interests might ask for, and almost always get, the Agriculture portfolio. Likewise, social democrats tend to want health and social security and greens the environment. This risks sclerosis, as the party in control has little incentive for fresh thinking. O n the other hand, it does avoid damaging policy swings and can give the party a chance to make a difference. This is not something that seems to be that easy (as we go on to explore in much more detail in Chapter 9). Yet, there does seem to be some l ink between which particular party in a coalition controls a particular ministry and the policy direction of that ministry. Political scientists Ian Budge and Hans Keman (1990) looked at labour and finance ministries and found, for instance, that they tended to pursue policies to

David Robledo

David Robledo

-

9 0 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

avoid unemployment more strongly when they were controlled by social democrats rather than conservatives, who in turn were more interested in reducing the role of the state.

Governing

The formation of a government via the naming of a cabinet and the swearing-in of ministers to whom particular portfolios have been awarded is, of course, merely 'the end of the beginning'. Most politicians in Europe, even the most mainstream centrists, see themselves as having a particular job to do, above and beyond merely keeping the state ticking over. Normally, this involves the transla-tion of policy into practice. More precisely, it involves ministers overseeing the drafting of legis-lation and the progress of civil servants in imple-menting the policies that have made it through the government formation process - the policies that are included in the coalition agreements that are becoming an increasingly common phenomenon in Europe (see Muller and Strom, 2000). This, as we suggested in Chapter 3, has become more diffi-cult. Most European states are no longer simply 'top-down' affairs although, as we also saw in Chapter 3, steps have been taken to tighten the hold of politicians over non-elected parts of the 'core executive'.

Ministers also have to meet wi th and take on board (or, at least, absorb) the views of pressure groups, particularly those on whom they may rely to some degree for the implementation of policy (see Chapter 8). In addition to interest groups and parties, another source of policy (and possible trouble) is the European Union. As we noted in Chapter 2, ministers in some departments may spend two or three days a month consulting with their counterparts in the other member states. In these consultations, they are assisted both by their home departments and by their country's Permanent Representative in Brussels. This 'ambassador to the EU ' , along wi th his or her twenty-four colleagues on the intergovernmental committee routinely referred to as COREPER, works to achieve compromizes that wi l l protect and promote the 'national interest' and, quite frankly, ease the burden of work for ministers.

N o t everything can be 'fixed' beforehand, however. A trip to Brussels can often, therefore, involve ministers trying to get something done or, alternatively, trying to stop something happening. This might be at the behest of other departments, whose civil servants meet in interdepartmental committees w i th those o f the department concerned. Or it might come from pressure groups or the cabinet or even, in Denmark, parlia-ment (see Box 4.7, p. 97). Ministers therefore play a vital linkage role between the national and the 'supranational'. Indeed, they are the embodiment of the blurring of the boundaries between them that is so important a part of contemporary European politics.

In Europe's parliamentary systems, ministers, even when they are not themselves MPs, also play a vital linkage role between citizens and the state by being individually answerable and, in most cases, collectively responsible to parliament. Being indi-vidually answerable means that they can, at least theoretically, be held to account for the actions of their department. This is vital i f there is ultimately to be democratic control of the state, although not all countries follow Poland, for example, and allow parliament to officially vote 'no confidence' in an individual minister, thereby forcing him or her to resign. Being 'collectively responsible' means that ministers are expected to support government policy or else resign. This cabinet collective respon-sibility is also important in democratic terms because parliaments express their confidence (or at least their lack of no confidence!) in the govern-ment as a whole. The fiction that ministers are all pulling in the same direction has therefore to be maintained, in order to preserve the political accountability of the executive in a system where the buck stops not with one individual (as it does in presidential systems), but with government as a whole.

This supposedly constitutionally necessary convention does not, in fact, hold everywhere: Belgium's cabinet ministers, for instance, are under no such obligation (Keman, 2002: 229) and, notes one expert (Sanford, 2002: 165), their Polish counterparts certainly feel under no such obligation! Nor , o f course, even where the convention has developed, does it preclude genuine and sometimes bitter disagreement

-

G O V E R N M E N T S A N D P A R L I A M E N T S 91

United Kingdom

Area: 6 . 1 % o f EU-25 Population: 13.1 % o f EU-25 GDP: 1 5 . 7 % o f EU-25 Joined E U :1973 Capital city: L o n d o n

History: T h e U n i t e d K i n g d o m o f Great B r i t a in ( E n g l a n d , Wa les a n d Scot land) a n d N o r t h e r n I r e l and t o o k some t i m e t o a s s u m e its p r e s e n t shape. Wales was all b u t a s s i m i l a t e d i n t o E n g l a n d in t h e 1540s . But t h e u n i o n o f t h e t w o w i t h t h e k i n g d o m of S co t l and , l o n g an a l l y o f France, was n o t a c h i e v e d u n t i l 1707 a n d not assured u n t i l a f t e r a Civ i l War . This c o n f l i c t , e v e n a f t e r t h e m o n a r -chy r e t u r n e d a f t e r a sho r t - l i v e d r epub l i c , e s t a b l i s h e d t h e s u p r e m a c y of p a r l i a m e n t o v e r t h e c r o w n . By t h e n , a f t e r c e n t u r i e s o f r e l i g i o u s d i s p u t e t h a t b e g a n in t h e s i x t e e n t h c e n t u r y w h e n t h e Eng l i sh k i n g b roke w i t h t h e R o m a n C a t h o l i c c h u r c h , B r i t a in was a l a rge l y P ro tes tan t c o u n t r y .

Across t h e sea, h o w e v e r , t h e i s l and of I r e l and , w h i c h B r i t a in h a d c o n q u e r e d b u t f o u n d h a r d t o subdue , was p r e d o m i n a n t l y Catho l i c . The r e was , h o w e v e r , a P ro tes tan t m i n o r i t y in U ls ter ( t he n a m e i t g a v e t o its s t r o n g h o l d in t h e n o r t h ) - o n e d e l i b e r a t e l y t r a n s -p l a n t e d t h e r e ( m o s t l y f r o m Scot land) in o r d e r t o s t r e n g t h e n co lon ia l p o w e r . W h e n , in t h e w a k e of t h e First W o r l d Wa r ( 1914-18 ) , I re land b e g a n t o r e g a i n its i n d e p e n -dence , th i s m i n o r i t y r e j e c t e d a p lace in w h a t ( in 1948) f i na l l y b e c a m e t h e sove re i gn Ir ish Repub l i c . I n s t ead , i t ins is ted o n r e t a i n i n g its l inks w i t h Great B r i t a in . By t h e b e g i n n i n g o f

t h e t w e n t i e t h c e n t u r y , B r i t a in h a d b e c o m e t h e w o r l d ' s g r e a t e s t c o m m e r c i a l a n d i m p e r i a l p o w e r . H a v i n g b e e n f o r c e d o u t o f t h e US in t h e e i g h t e e n t h c e n t u r y , i t h a d s p e n t t h e n i n e t e e n t h c e n t u r y f i g h t i n g t h e F rench in E u r o p e a n d u s i n g t h e w e a l t h g e n e r a t e d b y its p i o n e e r i n g ro l e in t h e I n d u s t r i a l R e v o l u t i o n t o es t ab l i sh c o n t r o l o f h u g e s w a t h e s o f t h e I n d i a n s u b c o n t i n e n t a n d A f r i ca .

Th is i m p e r i a l e x p a n s i o n h e l p e d p u t t h e c o u n t r y o n a c o l l i s i on c o u r s e w i t h t h e u p - a n d - c o m i n g i n d u s t r i a l p o w e r o f G e r m a n y . A l t h o u g h t h e e n s u i n g First W o r l d Wa r r e s u l t e d in a Br i t i sh ( and F rench ) v i c t o r y , i t p r o v e d a b i g d r a i n o n t h e c o u n t r y ' s resources , j u s t as its o t h e r al ly , t h e US, b e g a n t o s u p e r s e d e i t e c o n o m i -cal ly . T h e S e c o n d W o r l d Wa r ( 1 9 3 9 - 4 5 ) , f r o m w h i c h Br i ta in a lso e m e r g e d v i c t o r i o u s , c o n f i r m e d th i s r e l a t i ve d e c l i n e , as d i d its i n e x o r a b l e s u r r e n d e r o f its overseas e m p i r e . O n t h e d o m e s t i c f r o n t , h o w e v e r , t h e a f t e r m a t h o f t h e w a r saw t h e b u i l d -i n g by t h e c o u n t r y ' s f i r s t m a j o r i t y L a b o u r g o v e r n m e n t o f a c o m p r e -h e n s i v e w e l f a r e s ta te . S ince t h e n , p o w e r has a l t e r n a t e d b e t w e e n L abou r , o n t h e cen t re- l e f t , a n d t h e Conse r va t i v es , o n t h e c e n t r e - r i g h t , w i t h t h e f o r m e r , u n d e r T o n y Blair, w i n n i n g a l a n d s l i d e v i c t o r y i n 1997 a f t e r e i g h t e e n years o u t o f o f f i c e .

E c onomy a n d soc i e ty: A f t e r d e c a d e s o f b e i n g a r e l a t i v e l y p o o r p e r f o r m e r , t h e UK e c o n o m y - w h i c h u n d e r w e n t severe r e s t r u c t u r i n g u n d e r t h e f r ee m a r k e t po l i c i e s o f C o n s e r v a t i v e p r i m e M i n i s t e r M a r g a r e t T h a t c h e r d u r i n g t h e 1980s - has u n d e r g o n e s o m e t h i n g o f a rena issance in r e c e n t years . As a resu l t , t h e c o u n t r y ' s 6 0 m i l l i o n p e o p l e - a r o u n d 6.5 pe r c e n t o f w h o m c a m e (or t h e i r p a r e n t s o r g r a n d p a r e n t s c a m e ) as i m m i g r a n t s f r o m t h e C a r i b b e a n a n d t h e I n d i a n s u b c o n t i n e n t - e n j o y a pe r c a p i t a a n n u a l i n c o m e o f a b o u t 20 pe r c e n t a b o v e t h e EU-25 a ve r age (2003 ) . T h e south-eas t o f t h e c o u n t r y a r o u n d L o n d o n , h o w e v e r , is n o t a b l y b e t t e r o f f t h a n s o m e o f t h e m o r e p e r i p h -eral r e g i o n s .

Coun try Profile 4.1

Govern a nc e : T h e UK is u n u s u a l in t h a t , l ike t h e US, i t e m p l o y s n o t a PR b u t a ' f i r s t-pas t- the-post ' e l e c to ra l s y s t e m t o e lec t MPs t o its W e s t m i n s t e r p a r l i a m e n t . This a l m o s t a lways resu l ts i n s ing l e-pa r t y m a j o r -i t y g o v e r n m e n t s a n d m a k e s t h i n g s d i f f i c u l t f o r t h e t h i r d l a rges t pa r t y , t h e L ibera l D e m o c r a t s . It does , h o w e v e r , a f f o r d r e p r e s e n t a t i o n a t W e s t m i n s t e r t o n a t i o n a l i s t pa r t i es f r o m N o r t h e r n I r e l and , S c o t l a n d a n d Wales . As a resu l t o f t h e L a b o u r g o v e r n m e n t ' s p u r s u i t o f d e c e n t r a l -i z a t i o n a n d ' d e v o l u t i o n ' , t h e s e c o m p o n e n t s o f t h e UK n o w have t h e i r o w n l eg i s l a tu res , e l e c t e d u n d e r m o r e p r o p o r t i o n a l s ys tems . T h e N o r t h e r n I r e l and A s s e m b l y , h o w e v e r , has f a i l e d t o f u n c t i o n as p l a n n e d d u e t o d i s p u t e s o v e r t h e ' d e c o m m i s s i o n i n g ' o f t e r r o r i s t w e a p o n s .

T h e UK g o v e r n m e n t l ikes t o t h i n k o f i t se l f as a t t h e c u t t i n g e d g e o f n e w a p p r o a c h e s t o g o v e r n a n c e , c o n t r a c t i n g o u t c i v i l serv ice w o r k t o p u b l i c agenc i e s n o t d i r e c t l y c o n t r o l l e d b y m i n i s t e r s . It a lso p i o n e e r e d t h e p r i v a t i z a t i o n o f f o r m e r l y s t a t e - o w n e d u t i l i t i e s .

Fore i gn po l icy: T h e UK p r o v e d r e l u c t a n t t o j o i n i n E u r o p e a n i n t e -g r a t i o n u n t i l t h e l a te 1950s, w h e n i t rea l i zed its days as a w o r l d p o w e r w e r e n u m b e r e d a n d t h a t i ts e c o n o m y was s t a g n a t i n g . A f t e r severa l r e b u f f s ( f r o m France) , i t f i n a l l y j o i n e d w h a t was t h e n t h e EEC ( n o w t h e EU) in 1973 . It re ta ins its r e p u t a t i o n as 'an a w k w a r d p a r t n e r ' in t h e EU, a n d has c h o s e n so far n o t t o a d o p t t h e e u r o . EU m e m b e r s h i p is n o t seen as c o n t r a d i c t i n g e i t h e r t h e c o u n t r y ' s c o n t i n u a t i o n o f its self-s t y l ed 'spec ia l r e l a t i o n s h i p ' w i t h t h e US ( w i t h w h o m i t re ta ins c lose d e f e n c e , i n t e l l i g e n c e a n d t r a d e l inks) n o r its c o n t a c t s w i t h its f o r m e r c o l o n i e s v ia t h e Br i t i sh C o m m o n w e a l t h .

Further read ing . Budge e tal. (2003), Dun leavy e tal. (2003), Gamb le (2003) and Richards and Sm i th (2002).

-

9 2 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

within Cabinet. Studies of cabinets across western and eastern Europe suggest that many govern-ments (though not all governments, Sweden being an obvious exception) employ networks of cabinet committees to pre-cook and filter out issues different departments can agree on so as not to disrupt Cabinet itself although this technique cannot always prevent Cabinet from becoming a court of last resort between disputatious ministers rather than a collegial and collective decison-making enterprize. But those same studies also show that cabinets themselves are mostly still meaningfiil forums: their deliberations actually change policy (Blondel and Mii l ler-Rommel , 1997, 2001). The extent to which cabinets actually control ministers and prevent them from 'going native' (becoming more interested in protecting their departments than the interests of the govern-ment as a whole), however, is another matter (see Andeweg, 2000).

I t is also one that feeds into another thorny issue - the extent to which cabinets made up of pol i t i -cians from different parties, as is the norm in many countries, can actually work together. In fact, co-ordination often takes place outside the cabinet room itself In an increasing number of countries, the formation process produces a written agreement which is used to bind the coali-tion partners (and their ministers) into a common programme: the most detailed study we have comes from the Netherlands, and suggests it is quite an effective technique (see Thomson, 2001). In a few countries, the cabinet as a whole is encouraged to 'bond' by spending time wi th each other (whether they like it or not!) at 'working lunches' and the like - this is famously the case in Norway, for instance.

More often, co-ordination involves not just ministers but other party political actors. Sometimes this kind of co-ordination goes on in so-called coalition committees: the RedGreen coalition that took power in Germany in 1998 for instance quickly established a koalitionsausschuj?. But more often than not, it occurs informally. This might involve bilateral contacts by ministers or their political appointees to the civil service. In the case of disputes that are harder to resolve, it could involve troubleshooting by the prime minister and deputy prime minister who are very often from

different parties. But it may also involve meetings between party leaders, especially when, as occurs surprisingly often in Europe, those leaders do not actually play a formal role in government or even parliament (see Gibson and Harmel, 1998). In Belgium, for example, party chairmen meet frequently (often weekly) with 'their' ministers (see Keman, 2002: 228) and thus exercise a kind of 'outside' influence on Cabinet that would be considered intolerable in a country such as the UK, for example.

Excessive ministerial autonomy (or 'departmen-talitis') and intra-coalition co-ordination are not, however, the only problems facing the political part of a state's executive branch. Limited time is clearly a major - i f largely overlooked - constraint. And a government's capacity to do what it wants to do may be constrained by events beyond its control such as war, terrorism, recession and opposition from important interest groups such as trade unions or business representatives, often backed by the media. One would also expect, on both a strict interpretation of the separation of powers doctrine and the assumption that they owe their very existence in most European countries to parliament, that governments would be constrained by the second 'branch of government', the legislature. Interestingly, however, the influ-ence of Europe's parliaments over their executives - their governments - is widely dismissed as illu-sory. According to common wisdom, they are (or have over time been reduced to) talking shops and rubber stamps, while the prime minister and the cabinet call the shots. Is this really the case? Or -considering the variation in both the structure and the operation of parliaments around Europe that we now go on to discuss - is it rather more complicated than that?

Parliaments: one house or two

In most European countries, as in the US, the legislature is 'bicameral', wi th an 'upper house' that sits in addition to a 'lower house'. A minority -especially in small unitary states (the Scandinavian and Baltic states being a good example) - are 'unicameral'. They have only one chamber, although some (such as Norway) have developed

-

G O V E R N M E N T S A N D P A R L I A M E N T S 9 3

T a b l e 4 .5 O v e r w h e l m i n g l y b i c a m e r a l , b u t o n w h a t b a s i s : E u r o p e ' s p a r l i a m e n t s

Unica m eral Bica m eral Basis o f up per house

Czech Directly elected

France Electoral colleges o f main ly local pol i t ic ians, and overseas terr i tor ies

Germany Delegates f r o m state gove rnments {Lan der)

Italy 9 5 % direct ly e lected; 5% life-time appo in tmen t s

Netherlands Elected by provincia l councils

Poland Directly elected

Spain 8 5 % direct ly e lected; 1 5 % indirect ly elected by regional authori t ies

Sweden N/a

UK 8 0 % appo in ted for life; 1 5 % hereditary; 5% church

ways of dividing into what amounts to two cham-bers in order to scrutinize legislation better. In bicameral systems, the lower house (as the sole chamber in unicameral systems) is filled by MPs or 'deputies' who are directly elected by all adults entitled to vote. Upper houses, on the other hand, are not always directly elected (see Table 4.5). A couple have appointed members, including the British 'House of Lords'. Many are composed of democratically chosen representatives from local, regional - or, in federal countries, state-govern-ments and can therefore be considered 'indirectly' elected.

With the exception of Germany (Box 4.4), and to some extent Italy (see Boxes 4.4 and 4.5, pp. 94-5) and Romania, there is no doubt that in bicameral systems it is the lower house that is the more powerful, and therefore the focus of public attention. O n the vast bulk of legislation, the power of upper houses lies primarily in their ability to amend and/or delay, rather than actually to block, bills passed by the lower house. However, in some countries even this power is very limited. This might be because the lower house has the ability to bring things decisively to a head, as in France, where the senate can be overruled. Or it may be because the power is little used since the party composition of the upper house is so similar to that of the lower house, as in Spain. Despite this relative weakness, however, there seems to be no movement to dispense with them altogether in favour of unicameral systems: even in the Czech Republic,

where debate about the need for such a body and its composition was initially so heated that it almost failed to get off the ground, people seem reconciled to its existence, i f not exactly enthusiastic.

However, upper houses are not powerless. The power of delay is not necessarily to be sniffed at. Moreover, on proposed constitutional changes supported by the lower house, many of Europe's upper houses possess a power of veto. This makes sense given that their raison d'etre - especially in federal systems - is often to protect the rights and interests of sub-national government. And even where such a role is denied them, one can argue that upper houses still, potentially at least, have a valuable role to play. For instance, they provide a forum that, because it is less of a focus for media attention, is somewhat less charged and therefore somewhat more conducive to clear-headed consid-eration of issues. The U K House of Lords, for example, may be ridiculed as a bastion of entrenched conservatism, but its European Union Committee is acknowledged as performing a useful role in scrutinizing E U legislation that wi l l impact the U K .

Parliaments: hiring and firing

Generally, however, when most Europeans think of parliament, they think of the directly elected lower house. This is the place that not only passes laws, but makes and breaks - and in between hope-

-

9 4 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

B O X 4 . 4

The upper house w i th the upper hand? The Germ a n Bundesra t

Germany's upper house, the Bundesrat , is made up of sixty-eight members be long ing t o delegat ions f r o m the governments of each of the Federal Republic's sixteen states (Lander), w i t h de legat ions vary ing in s t rength f r o m three t o six members depend ing on the size of the state. These represen-tatives o f the Lander have qu i t e a large role in the passing of federal (i.e. national) legis lat ion. The Bundesrat has veto power over legis lat ion impact-ing on states - wh i ch means tha t over half o f all legislat ion has t o be vo ted on and approved there . And even w h e n a bil l does no t fall i n to this cate-gory, it is open t o the Bundesrat t o reject it . This obl iges the lower house, the Bundestag , t o produce a 'yes' vo te as b ig as the Bundesrat's 'no ' vo te in order t o overrule it. The extent t o wh i ch this makes th ings awkward for the g o v e r n m e n t depends , more than any th ing , on whe the r the party cont ro l l i ng it also controls the upper house. As in the US, this depends on it be ing able t o w i n those state elec-t ions tha t take place in be tween federal elect ions. If the oppos i t i on w in these (and they very o f ten do as the gove rnment bears the b run t o f 'mid-term blues'), the party compos i t i on o f one or more states' de legat ions changes, causing the gove rn-ment t o lose its cont ro l o f the Bundesrat . When this happens, 'd iv ided gove rnmen t ' prevails and the upper house comes in to its o w n . Perhaps t h r o u g h negot ia t ion in the Vermit t lungsausschuB ( the m e d i -at ion c o m m i t t e e f o r m e d by representatives f r o m b o t h houses), the Bundesrat o f ten obl iges the gove rnmen t in the lower house t o mod i f y those aspects of its legislative p r o g r a m m e tha t oppos i -t i on parties do not suppor t . It is this need t o take account o f the views o f oppos i t i on parties t ha t makes Germany's par l i ament (and perhaps its po l i -tics in general) so consensual. Accord ing t o critics, t h o u g h , it also makes radical re form practical ly impossible (see Chapter 9). Frustrat ion on b o t h sides led t o the sett ing up in 2003 of a bicameral commiss ion t o look in to modern iz ing the federal structure, possibly via a deal tha t sees the Lander get the r ight t o de te rmine th ings at local level in return for a reduct ion in the ir abi l i ty t o b lock measures at the federal level.

fully scrutinizes - governments. As we have seen, running European countries rests on a party or a coalition of parties being able to command a majority in confidence and supply votes in parlia-ment. Ultimately, then, parliaments are theoreti-cally the most powerful branch of government. When it comes to the crunch, it is they who retain the right to hire and fire the executive, thereby translating the results of elections into a govern-ment and forcing that government to account to those whom electors elect, and perhaps the electors themselves. But how powerful does this make them in practice?

Hir ing is indeed crucial, as we have suggested when looking at government formation. But it normally pits one party or collection of parties against another rather than the legislature as a whole against the executive. Moreover, once the task is complete, the power is essentially 'used up' unti l next time. Similarly, the power granted by the right to fire the executive lies more in the threat to use it than its actual use. The fact that it is a 'nuclear option' probably explains why, although the right of dismissal exists, it is surprisingly rarely used and few European governments are actually brought down by votes of no-confidence. This is partly, of course, because some of them choose to go before they are formally pushed. Others are sufficiently adaptable to avoid the kind of policies that would offend the MPs that originally supported their formation. Still others, when this cannot be done, are sufficiently prescient to have arranged alternative sources of support.

In a handful of cases, institutional rules make votes of no-confidence even more unlikely. In Germany, Spain and Poland, as we have seen, a government can be defeated only by a 'construc-tive' vote of no-confidence, which demands that the opposition already has an alternative govern-ment ready to take over immediately. In many countries, a government defeat in the house can -although it does not always - lead to new elec-tions that can come as a merciful release after a period of political crisis or legislative gridlock. But in Norway, where elections can be held only every four years, this option is unavailable. This makes no-confidence motions a less attractive way of 'solving' a supposedly intractable parliamen-

-

G O V E R N M E N T S A N D P A R L I A M E N T S 9 5

tary problem. The fact that a government defeat on a motion of confidence can lead to fresh elec-tions in other countries points to the fact that parliament's right to defeat the executive is, in any case, normally balanced by the executive's right to dissolve (or request the head of state to dissolve) parliament - a right that exists in all European democracies outside Norway, Switzerland and Finland. If, as an MP, your party is not likely to do well in a snap election, you are unlikely, however dissatisfied you are wi th the government, to stage a vote of no-confidence and thereby risk cutting off your nose to spite your face.

Parliaments: the production of law

Padiament's other most important function is the making (or at least the production) of law - the consideration and passing of legislation. There is provision in most countries for so-called 'private members bills'. But by far the bulk of the propos-als (and certainly the bulk of proposals that stand an earthly chance of actually ending up on the statute book) wi l l come from the government that, as we shall suggest, can pretty much rely on party discipline to get its way. Consequently, it is all too easy to buy into the caricature of European legisla-tures as merely 'rubber stamps' or 'talking shops' -or, worse, 'sausage machines' into which the exec-utive shoves its bills, cranks the handle, makes mincemeat out of the opposition, and smiles as its statutes pop out at the other end. Without going too far the other way, it is fair to suggest that such metaphors disguise a good deal of variation, but once again it is patterned variation.

Broadly, one can divide parliaments in western Europe into two groups that correspond to Lijphart's distinction between majoritarian and consensual systems (see Lijphart, 1999). In the former group, one would include the U K , and probably Spain, along with Ireland, Greece and France. In these countries, the government pursues its agenda with little regard for the input of other parties, which are more often than not clearly regarded as the opposition. This opposition knows that government is almost guaranteed to get its

B O X 4 . 5

The Italian Sena to: pow erfu l or po in t l ess?

With the except ion of a handfu l o f senators-for-life, the vast bulk of the Italian Senato is direct ly elected to an upper house tha t has equal standing w i t h the lower house, the Ca m era dei D ep utati. Italy therefore w o u l d appear t o have one of the most power fu l second chambers anywhere in the wo r ld . But, as in Spain, because elect ions t o the t w o houses take place s imultaneously the party complex ion of each is remarkably similar. Consequent ly there is far less of the partisan f r ic t ion witnessed in Germany (see Box 4.4). This does not , however, prevent disagree-ments be tween the t w o chambers on particular pieces of legislat ion, not least because local and national interest groups lobby bo th assiduously. Because bo th houses have equal power, some bills can be bat ted back and fo r th between t h e m for so long tha t they perish when new par l iamentary elec-t ions are he ld . Given this tendency t o delay legisla-t i on , Italians can be forg iven for w o n d e r i ng qu i te wha t the po in t o f bicameral ism is in the i r country . On the other hand, Italy seems headed toward a more major i tar ian and yet also a more devolved fu ture , and it seems as if the Senato may now be given a regional basis, and therefore the un ique const i tut iona l func t ion it current ly lacks. Both these deve lopments may see it emerge as more of a genu ine counterva i l ing force.

way. And anyway, it is likely to be sympathetic to the theory that its winning of the election gives it a mandate to do so. Therefore, opposition parties can do little more than offer the kind of criticism that (a) wi l l allow them to say ' I told you so' at the next election, at which hopefully the mandate wil l pass to them; and (b) hopefully undermine the government's popularity in the meantime. Parliament, in terms used by some political scien-tists, is an 'arena' rather than a truly 'transforma-tive' institution - and one that reacts to, and can do little or nothing to stop or even seriously slow up government initiatives (see Box 4.6).

The same can be said of 'consensual' parlia-ments, such as those in Germany, the Netherlands

-

9 6 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

B O X 4 . 6

Franc e 's fe eb l e par l i a men t

Most observers agree tha t t h e Asse m blee Nationale is one of Europe's weakest legislatures. Its members do themselves no favours by of ten staying away in order t o a t tend t o the affairs o f local gove rnment , in which many cont inue t o ho ld elected off ice and have their main power-base. The gove rnmen t controls parl iament's agenda. It can insist on it tak ing a yes/no 'package vote ' on a bill in its unamended state. It has n o t h i ng t o fear f r o m unwie ldy, oversized commit tees . And it has at its disposal a host of procedural techniques t o over-come any residual power of delay. Parl iament, const i tut ional ly , can legislate only in certain prescribed areas outs ide o f wh i ch gove rnmen t can issue wha t a m o u n t t o decrees. The censure m o t i o n necessary t o oust any gove rnment de te rmined t o insist on t reat ing a particular bil l as a mat ter of conf idence is d i f f icu l t t o employ . Moreover, parl ia-ment is const i tut ional ly unable t o pass a n o n -governmenta l bil l or a m e n d m e n t that w o u l d involve lower ing state revenues or increasing expendi ture !

Fortunately, France's const i tut iona l cour t (see Chapter 3) has recently made decree laws subject t o much greater constraint. In add i t ion , regulat ions can be amended by the Assembly. Theoretical ly, it also gets to subject all bills t o c o m m i t t e e scrut iny before the plenary session and n o w even gets t o meet all year round , not just the six months init ial ly a l lot ted t o it . But the picture pa inted is nonetheless one of weakness. This came about by design rather than by chance: the framers of the 'Fifth Republic' that began in 1958 were reacting - some m igh t say overreact ing - to a history o f governments tha t were of ten powerless in the face o f an Assembly riven by ideological and geographical disputes.

(and Belgium), Sweden (and other Scandinavian countries) and Italy, but not without some quali-fication. While they are still essentially 'reactive' (at least when compared to the US Congress) parliaments in these countries tend to feature more constructive criticism and operate at least sometimes in 'cross-party' rather than always 'inter-party' mode (King, 1976). These tendencies are, or have become, culturally ingrained, though

they may be institutionally supported. For instance, parliament's agenda might require the unanimous (or near-unanimous) consent of all parties (as in Scandinavia, and the Germanic and low countries, as well as Spain and Italy) rather than being decided by the government majority (as in the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Greece and Portugal) - something frequently used as an indicator of the overall power of parliament (see Table 4.6).

The parliaments of Central and Eastern Europe are harder to locate in such a schema. At first, a combination of volatile party systems, arguments between presidents and prime ministers, and weak bureaucratic support for the executive seemed to suggest that parliaments in the region had, i f not the upper hand, then rather more power than in the more established democracies (see Kopecky, 2003). Certainly, the Polish Sejm (which, it must be said, has a proud history stretching back over centuries) could claim to be one of Europe's more independent legislatures: it has a powerful committee system (a generally accepted indicator o f strength, as we see below) whose members can initiate legislation, up to half o f which (a very high proportion in relative terms) passes (see Sanford, 2002: chapter 5). Yet, it is hard to know how much of its strength is institu-tional and how much derives from the difficulties Polish governments face because of the unusually large number of parties and 'party-hopping' by Polish MPs, all of which makes things difficult for governments. Across the region as a whole, however, decreasing turnover among, and increas-ing professionalization of, MPs and the declining number of parties in most of its parliaments, have made them easier to manage. Also important in strengthening governments' hands have been the fast-track procedures brought in to ensure that parliaments could get through the huge body of legislation needed to meet the requirements of accession to the E U . I t w i l l be interesting to see whether such procedures are used for other purposes now that the accession process is complete.

The differences between consensual and majori-tarian parliaments are visual as well as rule-based. Some countries even have seating systems designed to take some of the heat out of the more adversar-

-

GOVERNMENTS AND PARLIAMENTS 9 7

Tab le 4 . 6 E u r o p e a n p a r l i a m e n t s : t h e s t r o n g a n d t h e w e a k

Strong parlia m ent Weak parlia m ent

(Sets own agenda; strong co m mittee syste m) (Govern m ent sets agen da; weak co m mittees)

Germany Sweden Italy Poland Netherlands Czech Rep. UK Spain France

ial aspects of parliamentary politics: Sweden, for example, makes its MPs sit in regional blocs rather than according to party, and many parliaments in Europe avoid the adversarial layout of the British House of Commons (see Andeweg and Mijzink's chapter in Dot ing , 1995, for the layout o f European legislatures). Perhaps most important, however, for both the facilitation of cross-party activit)' and the overall power of parliament is the existence of powerful legislative committees. These are especially prevalent in Scandinavian parlia-ments (see Box 4.7), in Germany and in some of the newer democracies in Central and Eastern Europe, especially Poland. In many countries in those regions, such committees get to make

amendments to (and in some cases redraft) bills before they are debated on the floor of the house by all interested MPs in what is known as 'plenary session'. I n majoritarian systems, committees usually get to go over the bil l only once it has received at least one, and possibly two, readings in plenary, by which time party positions have already hardened up and legislation is more 'set in stone'. Unlike in their consensual counterparts, commit-tee membership in these systems may not even be distributed according to each party's share of seats. In more consensual systems, proportionality is taken as given and (especially where there are minority governments) increases the chances of committees taking an independent line.

B O X 4 . 7

Power outs ide the p l enary: D an i sh par l i a m en t ary comm i t t e es

Although o ther Scandinavian par l iaments - and Germany and Poland - boast inf luent ia l commi t tees , and although some Italian commi t t ees t rad i t iona l l y had the r ight o f f inal assent on some minor legis lat ion, experts agree that the Danish Folk e ting possesses Europe's most power fu l par l iamentary commi t tees . It has twenty-four standing (i.e. permanent ) commit tees , each w i t h seventeen members , w i t h member sh ip rough ly p ropor-tional t o the party d i s t r ibu t ion o f seats in par l iament . Most commi t t ees cover the w o rk of one part icular ministry. When a minister proposes a bi l l , he or she can expect a f l oo d of w r i t t en quest ions by c o m m i t t e e members and may wel l be asked t o appear in person, t oo . Delay is not advisable because any bill tha t does not make it t h r o u g h all its stages in the par l iamentary session in w h i c h it is in t roduced wi l l have t o start all over again. The commi t tees ' report on the bi l l out l ines the parties' pos i t ions and amendmen t s tha t they hope t o see adopted in the second reading. In many par l iaments tha t w o u l d be it, bu t in Denmark an MP can d e m a n d tha t the bill go back t o c o m m i t t e e after the second reading for a supp lementary report !

All Folk e ting commit tees are potent ia l l y power fu l because, as in other Scandinavian countr ies, minor i t y gove rn-ment is so c o m m o n , mean ing tha t the execut ive wi l l rarely have a major i ty in commi t t ee . But the t w o most powerful are, w i t h o u t doub t , the Finance Commit tee , whose say on the budge t is much greater than its counter-parts in other legislatures, and the European Affairs Commi t tee , wh i ch is able t o dictate t o the country 's minis-ters the stand they must take on certain issues when vo t i ng in Brussels. Ministers are first answerable t o the Committee, and only then t o their colleagues for the i r EU-related actions. This loss o f executive au tonomy is seen as a price w o r t h paying by governments keen t o ensure tha t rows over 'Europe' do not break t h e m apart or cause other parties t o w i t h d r aw thei r support .

-

9 8 E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

Parliaments: scrutiny and oversight