Authority Usurped - Princeton

Transcript of Authority Usurped - Princeton

Authority Usurped ON THE THEOLOGICAL REPUBLICANISM OF MILTON’S PARADISE LOST

Mary Nickel | In Fulfillment of the Text in Context General Exam | April 18, 2020

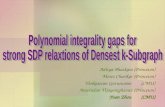

The image included on the cover page of this essay is taken from a collection of illustrations of Paradise Lost created by Gustave Doré. It is the sixth of fifty woodcuts. The plate introduces Book Two, which begins: “High on a throne of royal state … / Satan exalted sat, by merit raised / To that bad eminence and from despair / Thus high uplifted beyond hope aspires / Beyond thus high.” Doré’s dark representations set the mood for Milton’s epic poem, but particularly for the scenes, like this one, of the depths of hell. The sinister portrayal of monarchy in hell helps to answer, as I show in the following essay, a persistent puzzle in Milton interpretation concerning the committed republican’s defense of the heavenly monarchy.

“Authority Usurped” 1

Authority Usurped ON THE THEOLOGICAL REPUBLICANISM OF MILTON’S PARADISE LOST

Duorum in solidum dominium esse non posse Ulpian, Digesta 13.6.5.§15

Arbitrary governing hath no alliance with God

Samuel Rutherford, Lex Rex, Q.5

Not all Christians are theocrats. In fact, some of them have been agents for positive social

change. This, it seems, is the gist of an array of recent volumes and news stories. In an environment

where Christian identities have been aligned with conservative political identities, the existence of

Christian progressives appear idiosyncratic. Or so one would conclude in view of the news

coverage on the “emerging” religious left.1 As liberal Christianity is being rediscovered, so too are

the stories of historical Christian figures, in some cases baptizing them as prophets.2 Evocative

books explicitly highlight the constructive role that faith played the lives of political crusaders like

John Adams, Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Jane Addams, Dorothy Day, and

Martin Luther King.3 This list could easily be expanded, and without doubt it will continue to

expand. What is noteworthy is that the portrayal of the religious backgrounds of these activists has

been shifting. Where once the religious commitments of these figures may have been neglected or

even obscured, today those commitments are increasingly featured. The hope seems to be to

rehabilitate the possibility of a Christian faith that does not fall victim to conservative politics.4

With enough efforts, the progressive Christian no longer need be an endangered species.

1 See Malone, “‘Religious Left’ Emerging as U.S. Political Force in Trump Era.” More accurate headcounts describe a “revival.” See Jenkins, “How Trump Is Paving the Way for a Revival of the ‘Religious Left’”; Goodstein, “Religious Liberals Sat Out of Politics for 40 Years. Now They Want in the Game.” 2 See, for example, Raboteau, American Prophets; Dilbeck, Frederick Douglass: America’s Prophet; McKanan, Prophetic Encounters. 3 See, among others, Kittelstrom, The Religion of Democracy. 4 This is not the only purpose to which such historical accounts are offered: some also want to better understand the stories that precede ours. It is crucial that historians and political theorists understand the way religious commitments informed the efforts of abolitionists and suffragists and other political activists.

2 Mary Nickel

Perhaps the point still bears repeating: there is nothing that puts Christian faith and progressive

activism at inexorable odds. Fair enough. Yet the point ought to be made stronger. For many of

the United States’ most ardent Christian progressive crusaders, it wasn’t simply that their faith and

their politics were not incompatible, but rather that their progressive politics were inspired by their

faith. Abolitionism was, in the main, a theological project. So was the movement for women’s

suffrage.5 The civil rights movement was as successful as it was in large part because of the role

pastors and lay leaders played. It is quite difficult, in truth, to distinguish Martin Luther King’s

speeches from his sermons. Nor is King exceptional in that respect. Fannie Lou Hamer and

Lucretia Mott both habitually conveyed their demands for rights and recognition in the language

of the Bible. For these activists, theology is not incidental to activism but motivates it.

A number of theological doctrines have been marshalled in progressive political efforts; some

have received more attention than others in recent scholarship. The doctrine of the imago dei, for

example—the notion that human beings bear the image of God—is often cited as a rationale for

championing human rights. 6 Interpretations of the doctrine of the trinity that emphasize the

relationships among the three divine persons insist that humans ought to emulate God’s communal

essence.7 What has gained less attention is the way the theological doctrine of the absolute authority

of God, in particular, has repeatedly played a major role in the religious critics’ arguments against

domination. Albeit in different ways, figures like Douglass, Stanton, Lincoln, and King all affirmed

God’s absolute authority, and insisted that no human being should presume to usurp that stature

which belongs only to God. Domination—the relationship wherein one individual is subject to the

5 This feature of the history is less well known. However, it is increasingly gaining traction. See, for example, throughout the narrative in Weiss, The Woman’s Hour. History has yet to rediscover Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s interpretive work on the Bible, in which she argued using Biblical and theological resources for the liberation of women from the “usurpations” of men in church and state. See Kern, Mrs. Stanton’s Bible. 6 See, for example, Waldron, “The Image of God: Rights, Reason, and Order”; Pryor, “Looking for Bedrock.” 7 Works include, among others, Moltmann, The Trinity and the Kingdom; Volf, After Our Likeness; Boff, Trinity and Society.

“Authority Usurped” 3

other’s arbitrary will—was morally wrong for these figures precisely because it is tantamount to

usurping a prerogative that is God’s alone. The theological claim motivates the politico-ethical

claim.

After reviewing a republican sketch of domination, and why it is condemned by today’s

prevailing republican wisdom, I explore how the portrayal of domination that emerged in the

modern period relates to the notion of God as Dominus, the Latin word for “Lord.” I call this view

theological republicanism: a condemnation of domination grounded in a theology of God’s sole and

total kingship. Then, I focus on literature from Milton and his contemporaries to show how that

theological commitment was borne out in prose and poetry in modern England, with particular

attention to Milton’s Paradise Lost. The paper concludes by proposing that the theological notion of

the kingship of God can bolster, rather than undermine, republican democracy, as it necessitates

that political authority must always be limited.

THE TROUBLE WITH DOMINATION

The concept of freedom is a cornerstone in politics. What, exactly, freedom consists in remains

contested, however. In the second half of the twentieth century, scholars including Philip Pettit and

Quentin Skinner reintroduced a republican conception of freedom that they counterposed to

prevailing liberal notions of freedom. Whereas the latter emphasizes that what makes a person free

is the absence of others’ interference in one’s projects, for the republicans, freedom means not

being subject to another’s whims. It’s not enough to be able to do what you will to be free; you

must also be certain that your enduring ability to pursue your own projects does not depend on

the whims of another. To illustrate the point, Pettit is fond of using the example of Nora and

Torvald Helmer from the Danish play A Doll’s House. Like many wives in Norway in 1879, Nora is

consigned to depend on her husband to fulfill her wants and needs. On the one hand, Torvald

4 Mary Nickel

dotes on her, grants her every wish, and enables her to do what she wants (with the exception of

eating macaroons—though she does that anyway). On the other hand, she depends on Torvald for

the (semblance of) freedom she enjoys. Even though, in her case, Nora is fortunate enough to have

a husband who indulges her, she remains subject to his will, and so on Pettit’s account is unfree.

This portrayal recalls Cicero’s remark that “whether [a ruler’s] subjects are slaves to a mild master

or a harsh one, it is any case impossible for them not to be slaves.”8 For Cicero, that eminent

republican, freedom “does not consist in having a just master, but in having none.”9

Neither is it sufficient to have the confidence that your master will not interfere in your

endeavors. In Republicanism, Pettit explains that

the possession by someone of dominating power over another—in whatever degree—does not require that the person who enjoys such power actually interferes, out of good or bad motives, with the individual who is dominated; it does not require even that the person who enjoys that power is inclined in the slightest measure towards such interference. What constitutes domination is the fact that in some respect the power-bearer has the capacity to interfere arbitrarily, even if they are never going to do so.10

One who dominates need not actually mistreat his subject: the mere threat of the possibility of

mistreatment can suffice to curb the subject’s liberty. “To be dominated,” Stout writes, “is to lack

security against someone’s arbitrary exercise of power, even if that power is never in fact

exercised.”11 So long as a person owes his wellbeing to the goodwill of another, he must tread

carefully through his affairs, lest he risk the loss of that goodwill. As a result, the nature of the

relationship between the dominator and the dominated shapes both parties’ perspectives and

behaviors in the world. This sort of relationship is fundamentally unjust.

It’s not, it should be noted, that the exercise of power as such is unjust. Here an essential

distinction is made between the exercise of power and the exercise of arbitrary power. Surely, our

8 Cicero, On the Commonwealth and On the Laws, 22. That is, De Republica §1.50. It is worth noting that the word in Cicero’s Latin which Zetzel translates as “mild master” is dominus. 9 Cicero, 46. That is, De Republica §2.43. “libertas … quae non in eo est ut iusto utamur domino, set ut nullo …” 10 Pettit, Republicanism, 63. 11 Stout, Blessed Are the Organized, 302.

“Authority Usurped” 5

common social world cannot function without the exercise of power. To enforce agreed-upon

norms and hold wrongdoers accountable, someone must exercise power. What troubles republican

thinkers is the exercise of arbitrary power. It’s the arbitrariness, not the exercise of power as such,

that characterizes domination, and makes it unjust.12 In Republicanism, Pettit provides a helpful

sketch of what makes the exercise of power arbitrary. The exercise of power is arbitrary, Pettit says,

when the power holder proceeds “without reference to the interests, or the opinions, of those

affected” and “is not forced to track what the interests of those others require according to their

own judgements.”13 Power brokers ought to exercise their power for the benefit of those on the

receiving end of that exercise. Notice that a relationship may be one of domination, on Pettit’s

view, even if the power holder believes himself to act in the best interest of his subject. Torvald,

after all, imagined that Nora was best served by the kind of relationship that obtained between

them. Rather, those in power must be required to wield their authority in accord with what their

subjects believe is in their best interest “according to their own judgements.” If they do not do so, they

must be held to account.14 This accountability can either happen on the front end, by means of

procedural constraints, or on the back end, by elections and tribunals—or both.15

Republicanism has its critics, of course.16 Yet the republican view has enjoyed a great reception

in recent decades, such that scholars often write of a republican “revival.”17 Though some disputes

among republicans endure, the interpretation of freedom as non-domination (or some other similar

formulation identifying the absence of one’s subjection to arbitrary powers) is a centripetal force

12 Stout, 142–43, 213. 13 Pettit, Republicanism, 55. 14 In a negative formulation, Stout defines domination thus: “[p]ower minus accountability equals domination.” In Stout, Blessed Are the Organized, 63. 15 Pettit, Republicanism, 58. 16 For a notable exchange between Skinner and Pettit and their critics, see Laborde and Maynor, Republicanism and Political Theory. 17 Laborde, “Republicanism,” 513.

6 Mary Nickel

that unites republican thinkers.18 Freedom requires, according to republicans, that no one be in a

position to lord their power over you.

The discussion of the republican concept of domination offered heretofore only considers

relationships between human beings. What of the relationship between humans and God? Does

God hold arbitrary power over us, and so dominate us? Is God “forced to track,” in Pettit’s words,

what humans’ interests require, “according to their own judgements”?19 The theological problem is not

new: it has been raised by participants in the debate between theological intellectualists and

theological voluntarists, and considered by covenantal theologians during the reformation. Some

theologians have returned to this question in the wake of the republican revival. As I see it,

however, what ought to interest contemporary Christian republicans more than this puzzle is the

way that the doctrine of God’s kingship has been used to vindicate republican commitments. It is

to that history that I now turn.

DOMINUS DEUS

It’s no coincidence that the words domination and dominus—that is, the Latin word for “master”

or “lord”—are etymological twins.20 Domination is a thing that a master (dominus) effects: that is, a

master has absolute authority (dominatus) over that which he or she is master. In Roman antiquity,

the word dominus was used as an honorific, roughly equivalent to the modern-day “sir.” This sense

18 Insofar as non-domination means the absence of anyone able to exercise arbitrary power over you, this is accepted by republican thinkers including Philip Pettit, Quentin Skinner, Maurizio Viroli, Frank Lovett, and Cécile Laborde. The latter’s use of the concept for feminist ends is particularly noteworthy. Laborde writes that “[d]omination is a useful concept for feminists because it suggests that the mere condition of being vulnerable to others’ actions, decisions, and opinions, without necessarily being coerced or otherwise interfered with by them, may be freedom-limiting, and that such condition has importantly structural and institutional features.” In Laborde, Critical Republicanism, 152. 19 The Biblical witness suggests otherwise: humans’ demands that God make the world otherwise, to achieve what they believe to be their own good, are often not answered. At the same time, humans do nevertheless appeal to God on the basis of God’s promise, or—as in the case of Moses—on the basis of God’s self-respect. 20 This section involves some argument from etymology. I practice a healthy skepticism regarding such reasoning, as it doesn’t always follow. (The joke about driving on a parkway and parking on a driveway highlights this: the fact is, the meanings of words do not always derive from their etymological parts.) Yet, the etymological ties between dominus and domination are germane given the use of the term dominus in early Christian circles. The suggestion is that domination as such is not the issue, as long as the rightful Dominus is doing the dominating.

“Authority Usurped” 7

of the word lingers in its etymological successors: the honorifics Don, Doña, Dame, and Madam all

stem from dominus.21 But the word was also used in antiquity to identify a person who held the right

to something, whether that estate included land, livestock, or people.22 The dominus is one who has

supreme authority over his dominium—that is, that to which he owns the right. According to Roman

law, a dominus need not physically possess his dominium, though he always maintains the right to do

so. Neither does physical possession make a person a dominus. The terms do not signify a particular

behavior or treatment, but rather a relation to that which is held.23 “Dominium,” according to a

classic encyclopedia of Ancient Greek and Rome, “properly signifies the right of dealing with a

corporeal thing as a person (dominus) pleases.”24 As such, dominium could not be shared. Only one

individual could have the final say over his dominium.25 Over time, dominus was invoked in cultic

devotion to the Roman emperor, and conveyed reverence for and recognition of imperial

authority.26

It was in this context that early Christians confessed that “Iesus Dominus est”—that is, that

“Jesus is Lord.” In fact, modern scholarship on the earliest Christian communities surmises that

this was one of the earliest, if not the earliest, of the Christian confessions.27 In so confessing, they

declared the radical claim that Jesus, as God incarnate, was the Dominus—not just over this or that

estate, but over the entire universe, as its supreme and rightful governor. This was but a

21 So, too, does the word “don,” a term for a prominent academic, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. 22 This could be contrasted with imperium, a term in Roman law which names the way that rulers hold authority over a domain on behalf of the public. Whereas dominium is a matter of private ownership, imperium is exercised by those entrusted with public authority, when they punish crimes and disburse public funds. See Lee, “Sources of Sovereignty.” Though it would be fascinating to explore why God is referred to as dominus and not imperator, that is beyond the scope of this paper. 23 See also Lovett, A General Theory of Domination and Justice, 3, 236–38; Brandon, New Worlds for Old, 121. 24 Smith and Anthon, “Dominium.” For discussion, see Lee, “Sources of Sovereignty,” 88; Birks, “The Roman Law Concept of Dominium and the Idea of Absolute Ownership.” 25 For discussion, see Lee, “Sources of Sovereignty,” 88; Birks, “The Roman Law Concept of Dominium and the Idea of Absolute Ownership.” 26 Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ, 108. 27 See Hurtado, 109, 184. In Greek, the phrase is “

8 Mary Nickel

continuation of the Jewish tradition’s substitution of (Adonai), the Hebrew word for “My Lord,”

for the unspeakable divine name.28 Given the rising trend of referring to Caesar as Dominus, the

confession of God as Dominus posited a direct competition between the two. Because dominium

cannot be shared, early Christians’ confession implied that even Caesar would be subject to the

divine Dominus. Of course, this was not enthusiastically endured; Christians went to their deaths for

their confession of Jesus as Lord. Polycarp, for example, was burned at the stake for refusing to

confess Caesar as Dominus. According to traditional accounts, a justice of the peace had tried to

persuade Polycarp to save his life, entreating him, “what harm is it to say ‘Caesar is Lord’?” To

this, Polycarp summarily answered, “how can I blaspheme my king who saved me?”29 Such

martyrdoms proved no effective deterrent for those who would claim that God had dominium over

the world, however.30 The conception of God as Dominus quickly sedimented into fundamental

expressions in the Christian idiom, in ways that linger today.31 Consider that Dominus appears in

the Vulgate translation of the Bible almost twice as many times as Deus, the word in Latin for God.32

When early Christians declared that Jesus Christ or God the Father was the supreme Dominus,

particularly in the linguistic context in which they lived, they made a claim about God’s relation

to the world. If the world and its inhabitants are God’s dominium, then the world and its inhabitants

are at God’s mercy. After all, by the very nature of their relationship, the dominus can do with his

28 Hurtado, 109. In the Vulgate translation of the Bible, Adonai is, of course, rendered as Dominus. 29 The account ends with an affirmation that Jesus is “king forever.” Hartog, Polycarp’s Epistle to the Philippians and the Martyrdom of Polycarp, 251–53; Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ, 609. 30 Jews who similarly refused to honor Caesar as Lord, too, suffered death. See Josephus’ description of the fall of Masada in Josephus, The Jewish War, 371–72. 31 For example, after Constantine made Sundays legal holidays, the official name of the day of the week changed. Whereas it had once been dies Solis (day of the Sun), it became dies Dominica (day of the Lord). Most Romance languages today bear vestiges of this shift. Consider, too, that the way years are identified as after the birth of Christ—for example, 1649 AD—is with the abbreviation “AD” for Anno Domini, or, the “year of the Lord.” 32 This is, it should be admitted, in part because Dominus is used as a substitute for the divine name in the Old Testament. Nevertheless, the statistic is remarkable. Deus appears about five thousand times in the Vulgate, while Dominus appears about nine thousand times. Fifteen hundred of the instances of the word Dominus include the formulation Dominus Deus in its various declensions.

“Authority Usurped” 9

dominium as he pleases. Early Christians earliest confession bold claimed that God is in a position

of absolute authority over the universe, and that all humans—even those in positions of authority—

live and breathe only at the mercy of the Dominus Deus.

What are we to make of this notion? Could such a relationship constitute domination? Could

God’s relationship to the universe be ineludibly unjust? It seems to me, however, that asking the

question in this manner gets the direction of the political vector wrong. The fundamental critique

of domination that Christians have historically offered doesn’t begin with the premise that

relationships of domination are wrong. They arrive at that premise. They begin, like the liturgies of

the early church, with the claim that Jesus is Lord. It’s in light of that confession that they determine

that the domination of one human over another is patently unjust. The logic proceeds in this

fashion: if God is the only rightful dominus, then those who arrogate to themselves the right of

dominus are wresting from God what is only God’s. Those who play dominus are doubly unjust, in

that they first fail to give God the honor that is due, and then wrest from God what can only

rightfully be God’s. This, I want to suggest, is the central premise of theological republicanism.

DIVINE AND HUMAN LORDSHIP: ANALOGIES AND DISANALOGIES

In his The Crisis of the Twelfth Century, the Harvard medievalist Thomas Bisson traces a shift in

European society between around 1050 and 1220 that has largely to do with who might be worthy

of the title dominus. Using the English “lordship” in lieu of the Latin dominatio, Bisson claims that his

book is a history of how “medieval lordship [that is, according to Bisson, the domination of people]

came to maturity.”33 Lordship matured, as Bisson puts it, as God’s apparent monopoly on the role

of dominus deteriorated. All had agreed that God had endowed certain persons with power, which

they justly wielded on behalf of the church and God’s people. But kings and prelates were ministers

33 Bisson, The Crisis of the Twelfth Century, ix, 3. Bisson explicitly equates the English term lordship with the Latin dominatio.

10 Mary Nickel

of God’s power, not possessors of it. Such ministers were to be held accountable to God for their

performance as custodians of divine power—in some fashion.34 Rulers, wrote the archbishop of

Reims in the late ninth century, should “understand that they are appointed for this: that they

should preserve and rule the populace, not that they should dominate and afflict [it]; nor should

they think of God’s people as their own or to be subjected to themselves to their glory.”35 In the

limited cases where persons bore the title of “Lord,” they were to do so in humility and

responsibility.36 Another ninth century bishop bemoaned the rise of the designation “senior” for

nobles, as it, in Bisson’s paraphrasing, “seemed to justify a grasping for human precedence contrary

to patristic assertions of equality before God. God meant for people to dominate animals, not one

another.”37 Yet by the twelfth century, nobles increasingly made the case that their relationship to

their subjects was analogous to God’s relationship to God’s subjects. God’s sovereign power was

demonstrated in the establishment and maintenance of order, and the order which self-promoting

lords helped to establish justified those lords’ acquisition and exercise of power.38 (No matter, of

course, that the threat of disorder came from the same ones who claimed to institute order.) For

lords in the twelfth century and thereafter, God was their exemplar, not their overseer.

The analogizing of the relationships between God and humans, on the one hand, and between

a lord and his subjects, on the other, remained operative into the early modern period. It was on

the basis of an analogy between these relationships that monarchists like James I and Robert Filmer

defended the divine right of kings.39 Indeed, for both James I and Filmer, the power exercised by

the human sovereign is God’s power. “Kings are called gods by the propheticall King David,”

34 Bisson, 10, 15. 35 As quoted in Bisson, 23. 36 Bisson, 35. 37 Bisson, 36–37. Meanwhile, Bisson writes that one of his colleagues has likened the appearance of the word “senior” to a blanket spreading across medieval Spain, in Bisson, 39. 38 Bisson, The Crisis of the Twelfth Century, 4, 64, 70. 39 Stuart, King James VI and I: Political Writings; Filmer, “Patriarcha.”

“Authority Usurped” 11

wrote James I in his Trew Law of Free Monarchies (1598), “because they sit vpon GOD his Throne in

the earth, and haue the count of their administration to giue unto Him.”40 In a letter to his son

Henry, James I even included the following lines in a sonnet on monarchy: “God giues not Kings

the style of Gods in vaine, For on his throne his Scepter do they swey.”41 The supremacy that a

king has over his people, James I reasoned, corresponds to the supremacy of God over human

beings. Filmer, too, championed the divine right of kings by means of a paternalist allegory. Just

as fathers are to be governors of their families, according to God’s command, a king serves as

divinely ordained pater patriae (father of the nation).42 Obedience to the king, for Filmer, is a form

of compliance with the fifth commandment, to honor thy father and mother.43 As such, “kingly

power is by the law of God.”44 Resistance to the king’s power is resistance to God. So argued James

I in a speech before Parliament: “to dispute what God may doe, is blasphemie,” and in the same

way “is it sedition in Subiects, to dispute what a King may do in the height of his power.”45

It was not only the monarchists who argued for the analogy of God’s rulership to kings’

rulership. Indeed, even some of the early resistance to monarchy in late sixteenth-century Europe

was put in terms of that analogy. A generation after John Calvin, the reformer who highlighted the

covenantal relationship between God and God’s people, theologians like Beza and de Mornay

began to portray monarchs similarly as parties to a covenant with their people.46 Just as God would

be duty-bound to honor the covenant God made with Israel, a king would be duty-bound to honor

the covenant that constitutes the relationship between the king and his people. If a king were to

breach that covenant, his subjects’ duty to obey him would be annulled. What is remarkable about

40 Stuart, King James VI and I: Political Writings, 64. The Biblical reference is to Psalm 82:6. This was, of course, a favorite verse of James’. 41 In Stuart, 1. 42 Filmer cites Genesis 9:7 and 27:29, in Filmer, “Patriarcha,” 10. 43 Filmer, 11–12. 44 Filmer, 35. 45 Stuart, King James VI and I: Political Writings, 184. 46 For a complete narrative of this history, see Henreckson, The Immortal Commonwealth.

12 Mary Nickel

this line of critique of kingly domination is that it is based on the same analogy that monarchists

like James I presuppose. It conforms to the monarchist claim that the relationship between God

and humans resembles the relationship between a king and his subjects, but opposes monarchism

by portraying God as one who is held accountable to God’s own promise. Likewise, kings could be

held accountable to two covenants: the covenant they participated in with God, and the covenant

they participated in with their people.47 The early reformer Christopher Goodman, for example,

would thus write in 1558 that God’s covenant with the Hebrews was a model and a rubric for the

covenant that obtained between a monarch and her people.48 As David Henreckson explains, such

covenantal thinkers argued “that the people’s antecedent relationship with God provided a

normative standard for the relationship between the ruler and the ruled.”49 Kings (and queens)

who violated this standard were liable to be resisted.50

However, some covenantal theologians were also eager to point out where the analogy between

God’s relationship with human beings and a king’s relationship with his subjects came to a

screeching halt. In fact, for many of the covenantal theologians, it was the limits of the analogy

between divine-human and inter-human relationships that proved crucial. 51 The disanalogy

47 See, for example, Brutus, Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos, 37, 54, 129. The authorship of the Vindiciae is contested, though the text was likely a collaboration between Huguenots de Mornay and Languet. As it remains contested, however, I will refer to the author as “the author of the Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos.” 48 “… this was the couenant onlye that God made with them before he gaue them the Lawe in wrytinge, and the promes that they made to obserue the same Lawe, that they might therby be his deare and chosen people … This example ought neuer to departe from the eyes of all such as are, or woulde be Gods people.” Goodman, How Superior Powers Oght to Be Obeyd, 164. It further substantiates the broader claims of this paper that Goodman’s political tract was first drafted as a sermon. (The pronoun “her” is particularly appropriate here, as the infamous Queen Mary reigned in Goodman’s time.) 49 Henreckson, The Immortal Commonwealth, 126. 50 Goodman, Knox and others wrote vociferously against the Marian persecution of protestants in the 1550s. Some of the less palatable writings offered by the Marian exiles, including Knox’s The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women, include unreservedly sexist arguments for their position. 51 The covenant theologians’ contraposition of divine and human rulership was not original, however. In addition to the enduring tradition of ancient Christians’ bold claim that “Jesus is Lord,” many covenant theologians also highlight the story recounted in I Samuel, where Israel begs their prophet, Samuel, for a king. To God, the Israelites’ desire for a human king quite plainly demonstrates their rejection of God’s kingship. “[T]hey have me from being king over them,” says God (Hebrew: ). In I Samuel 8:7.

“Authority Usurped” 13

between the two relationships is what finally sets the terms of human rule. One of the earliest

advocates of this line of argument was John Ponet, the author of A Short Treatise on Political Power.52

As early as 1556, Poynet wrote that, “in a Realme or other dominion, the realme and countreie

are Goddes, he is the lorde, the people are his seruaunts, and the king or governour is but Goddes

minister or stuarde, ordained not to misuse the seruaunts, that is, the people.”53 Kings must be

brought to recognize that all power is derived from God, who is the “power of powers” and “our

lorde and the highest power.”54 Therefore “kinges, princes, and gouernours of commonwealthes

haue not nor can justly clayme any absolute autoritie.”55

The Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos, a pamphlet circulated after many thousands of Protestants were

raped and murdered on royal orders in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in France, similarly

emphasized the disanalogy between divine and human kingship. It opens by underscoring the

disanalogy between the rulership of God and that of a king56:

God rules by His own authority, but kings as if by sufferance of another: God by Himself, and kings through God: that God exercises His own jurisdiction, but kings only a delegated one … Furthermore, God created heaven and earth out of nothing, so by right He is truly the lord [dominus] and proprietor of heaven and earth … those who have jurisdiction on earth and preside over others for any reason, are beneficiaries and vassals of God and are bound to receive and acknowledge investiture from Him. In short, God is the only proprietor and the only lord [dominus]: all men, of whatever rank they may ultimately be, are in every respect his tenants, bailiffs, officers, and vassals.57

And furthermore:

if a king claims for himself both types of tribute … he is guilty of attempting to seize the kingdom; and just like a vassal who usurps regalian rights, he forfeits his fief and is most wisely deprived of it. This is all the more fair because there is some proportion between a vassal and a superior lord [dominus], but there can be none between a king and God, between some simple man and the Almighty.58

52 John Adams would later write that Ponet’s treatise “contains all the essential principles of liberty.” Adams, “A Defence of the Constitutions of the United States of America,” 225. 53 Ponet, A Shorte Treatise of Politike Pouuer, 95. 54 Ponet, 52, 76. 55 Ponet, 33. 56 Soman thinks it may have been as few as 2,000 slain, but Kelley endorses an estimate as high as 36,000, with as many as 12,000 women and girls raped throughout France. See Soman, Massacre of St. Bartholomew, viii, 199. 57 Brutus, Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos, 16–17. I have identified it per the original text in Latin. 58 Brutus, 27–28. Emphasis added.

14 Mary Nickel

For the author of the Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos—as for Ponet—no human ought to arrogate to

himself the lordship which is the prerogative of God alone. If a king were to claim to have absolute

power, he would be feigning Godhood, and stealing that which is God’s. Furthermore, no one who

confesses God’s lordship should indulge such idolatrous impiety.59

The Vindiciae was written pseudonymously—and with good reason. The French royals had

made clear in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre what the subversive Huguenots might suffer

for their publicly displayed convictions, much less their published provocations. The Vindiciae did

not need a noteworthy author, however, to enjoy widespread publication. The radical ideas did

that work on their own. In just over forty years, the pamphlet survived six editions in England.60

(Ponet’s treatise, too, was reprinted in London in 1639 and 1642.61) Neither did it take very long

for the Vindiciae to be publicly burned in England. But those flames could not put out the fire that

had swept in from the Monarchomachs on the Continent. Before long, English and Scottish writers

were disseminating similar arguments. Samuel Rutherford’s Lex, Rex—a reversal of James I’s

dictum that “Rex est Lex,” or that “the king is the law”—was one of the most striking successors

to the Vindiciae. “Arbitrary governing,” Rutherford wrote, “hath no alliance with God.”62 Indeed,

“a power ethicall, politick, or morall, to oppresse, is not from God, and is not a power, but a

licentious deviation of a power, and is no more from God, but from sinfull nature, and the old

serpent, than a license to sinne.”63

It is difficult to say decisively which anti-monarchist argument—the one highlighting the

analogy between God’s relationship to God’s people with the relationship between a king and his

subjects, or the one highlighting the disanalogy—had a greater bearing on the anti-monarchist

59 Brutus, 54–59. 60 McLaren, “Rethinking Republicanism,” 24. 61 Marian Exiles 59 62 Rutherford, Lex, Rex, 25. 63 Rutherford, 59.

“Authority Usurped” 15

movement in England or elsewhere. Yet the argument from disanalogy, insisting as it does on the

total and exclusive sovereignty of God, endured. Its resonances ricochet through the annals of the

English Revolution. “Christ, not man, is king,” went a favorite slogan of Oliver Cromwell.64 A

pamphlet circulated in London in 1652 was titled “No king but Jesus,” which was also a rallying

cry for the millenarian Fifth Monarchist movement.65 The radical Levellers, too, adopted similar

language. John Lilburne, a founder of the group, wrote in 1646:

… unnatural, irrational, sinful, wicked, unjust, devilish, and tyrannical it is, for any man whatsoever—spiritual or temporal, clergyman or layman—to appropriate and assume unto himself a power, authority and jurisdiction to rule, govern or reign over any sort of men in the world without their free consent; and whosoever doth it—whether clergyman or any other whatsoever—do thereby as much as in them lies endeavour to appropriate and assume unto themselves the office and sovereignty of God (who alone doth, and is to rule by His will and pleasure), and to be like their creator, which was the sin of the devils’, who, not being content with their first station but would be like God; for which sin they were thrown down into hell, reserved in everlasting chains, under darkness, unto the judgement of the great day.66

Of course, much separated Cromwell, the Levellers, and the Fifth Monarchists. What united them,

however, was a shared commitment to theological republicanism: the principle that God alone was

king, and that anyone who dared assume the crown was trying to usurp God’s kingly role.67 Such

usurpation, the Puritan Rutherford and Leveller Lilburne could agree, was the enterprise of devils

and the old serpent.

MILTON’S THEOLOGICAL REPUBLICANISM IN

This same commitment to God’s total and exclusive kingship is also foregrounded by John

Milton in his critiques of monarchism.68 In both The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (1650) and The

64 The cinematic portrayal of Cromwell in the eponymous film portrays his tomb as including this slogan as an epitaph. Of course, we do not know for certain what his tomb originally looked like, as Cromwell was posthumously exhumed, hanged, and beheaded by Charles II after the restoration. 65 Haggar, No King but Jesus. The Fifth Monarchists were so extreme in their theologizing the English Revolution that they believed that their efforts were going to bring forth the second coming of Christ. The term derives from the four kingdoms that were to precede Jesus’ return to Earth. These rebels—who planned insurrections against Cromwell in 1657 and then against Charles II in 1661 after the Restoration—insisted that their cause was that of “King Jesus.” Capp, The Fifth Monarchy Men; Greaves, Deliver Us from Evil, 50–57. 66 As printed in Sharp, The English Levellers, 32. 67 McLaren writes that unlike classic republicans, early modern republicans grounded their arguments in Christian theology, and that contemporary readers tend to overlook this difference. McLaren, “Rethinking Republicanism.” 68 Milton also cites the story in I Samuel 8 referenced above in n. 51, as do Winstanley, Rutherford, and Sidney.

16 Mary Nickel

Readie and Easie Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth (1660), Milton echoes Ponet and the author of

the Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos. (In fact, Milton quotes Ponet directly in the Tenure, though he

misappropriates the citation to Anthony Gilby.69) Milton repeatedly lambastes those who dare to

seize that to which only God is entitled, as well as any who would defend such an act.70 “No

Christian Prince, not drunk with high mind, and prouder than those Pagan Cæsars that deifi’d

themselves,” Milton writes, “would arrogate so unreasonably above human condition.”71 Then,

Milton repudiates James I and his supporters explicitly, when he writes that

[t]o say Kings are accountable to none but God is the ouerturning of all Law and Government. For if they may refuse to give account, then all cov’nants made with them at Coronation; all Oathes are in vaine, and meer Mockeries, all Lawes which they sweare to keep, made to no purpose; for if the King feare not God, as how many of them doe not? we hold then our Lives and Estates, by the tenure of his meer Grace and Mercy, as from a God, not a mortal Magistrate, a position that none but Court Parasites or Men Besotted would maintain.72

Two years later, Milton declares in his Defence of the People of England that “a king will either be no

Christian at all, or will be the slave of all. If he clearly wants to be master, he cannot at the same

time be a Christian.”73

Here Milton uses a republican vocabulary, but in a profoundly theological register. If a king

were not held accountable to the people, then the lives of the king’s subjects would be left at the

mercy of that king. This is the very type of relationship that has been classified as domination. But

notice the relevant phrase: “as from a God.” To be at the mercy of another is to render them as a

God, a dominus. For Milton, humans do hold their lives and estates at God’s mere grace and mercy,

69 This is helpfully pointed out by Lim, John Milton, Radical Politics, and Biblical Republicanism, 31. The passage is in Milton, “The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates,” 41; see discussion in n. 173 on that page. 70 Stout’s paraphrase of Thomas yields similar conclusions: “giv[ing] to a creature the honor due to the creator” is “idolatry.” Similarly, religion—piety toward God—may be undermined “whenever rulers … declare themselves divinely chosen, or declare themselves worthy of worship—declare themselves deities.” In lectures one and three of Stout, “Religion Unbound.” 71 Milton, “The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates,” 12. 72 Milton, 11–12. Emphasis added. 73 Milton, “A Defence of the People of England,” 110.

“Authority Usurped” 17

for God is the rightful dominus.74 The injustice arises when a human presumes to usurp the role that

is not his to assume.

There is, of course, one human who could rightfully assume kingship without blaspheming.

“Who,” Milton wrote in his Defence, “who is worthy to hold on earth a power like that of God,

except one who is most outstanding beyond all others and is even very like God in his goodness

and wisdom? And he, in my opinion at least, can only be that Son of God for whom we wait.”75

That assumption of divine kingship would govern the narrative arc of Milton’s epic poem, Paradise

Lost. That poem, which accomplishes many other tasks—indeed, Milton explains in its opening

lines that he intends to “justify the ways of God to men”—centrally portrays the triumph of God,

especially in Christ, over “th’ aspiring dominations.”76

In appreciating Milton’s theological republicanism, we can offer a reading of Paradise Lost that

addresses an enduring puzzle about Milton’s representation of monarchy and Satan’s anti-

monarchical rebellion in the epic poem. “It has become a cliché of Milton criticism,” writes David

Norbrook, “to point to the tensions between Milton’s republicanism and divine kingship.”77 So

goes the classic puzzle: on the one hand, Milton’s Satan is clearly a sinister character, devised to

earn the scorn of Milton’s readers. But, on the other hand, Milton’s Satan is one who resents and

campaigns against his king, just as had Milton and his republican compatriots during the English

74 In fact, in a mirror image of the same argument, Milton adds that to dominate another human being—much less to sustain that position of domination over them over time—would be to violate the image of God in each human being. “No man who knows ought, can be so stupid to deny that all men naturally were borne free, being the image and resemblance of God himself, and were by privilege above all the creatures, born to command and not to obey.” In Milton, “The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates,” 8. This is, I think, at least one functional element of the famous Josiah Wedgwood’s Slave Medallion: the enslaved man, entreating his audience, “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER” not only appeals to a shared humanity but also a shared participation in the imago dei. 75 Milton, “A Defence of the People of England,” 153. 76 Milton, Paradise Lost, 18, 90. (PL I:26 and III:92.) It might deserve mention that the first, famous quotation is drawn from a prayer, in which Milton entreats God: “What in me is dark / Illumine, what is low raise and support, / That to the height of this great argument / I may assert eternal providence / And justify the ways of God to men.” 77 Norbrook, Writing the English Republic, 477. Norbrook even quotes a censure of Milton’s Readie and Easie Way to make the point. Milton, according his critic, “must prove that [Christ] erected a Republique of his Apostles, and that notwithstanding the Scripture, every where calls his Government the Kingdome of Heaven, it ought to be Corrected, and Rendred the Common-wealth of Heaven.” As quoted in Norbrook, 477.

18 Mary Nickel

Civil War. Why, critics brood, would Milton portray as wicked a character whose aspirations so

closely identified with his own? Lejosne extensively details how the Satan of Paradise Lost uses dozens

of the same tropes and reasonings as did the pamphleteer Milton during the English Civil War.78

Furthermore, the sole demon willing to defy Satan’s plan—the commendable Abdiel—articulates

arguments made by Salasmius, Milton’s royalist opponent. Why would Milton put his own words

in the mouth of Satan?

Some have suggested that this maneuver of Milton’s reveals his own conflicted conscience

about the failure of the English Commonwealth.79 Surely, the work of the later Milton reveals

development and revision on a number of political commitments. One can all too easily discover

Milton’s idealism lost. Moreover, one of the precious virtues of Milton’s work dwells in his ability

to construct a complicated, multivalent world in his writing. Perhaps Milton lamented his own

support of the ill-fated Commonwealth, while maintaining his commitment to republican

principles. However—as is so often the case in Milton—another reading is possible, and, I’d argue,

more credible. Given Milton’s immersion in the theological republicanism of his day, it would not

be surprising to see it emerge in Paradise Lost. For Milton, the theological republican, Satan’s

wickedness does not derive from his resistance to a king; it derives from his resistance to the king.80

Already in the first few dozen lines appears a description of the “infernal serpent,” who sought

“[t]o set himself in glory above his peers,” and who, “with ambitious aim / Against the throne and

monarchy of God / Raised impious war in heaven and battle proud / With vain attempt.”81 Then,

as the poem depicts humans’ fall from grace, it comes to its narrative climax in that fateful moment

78 Lejosne, “Milton, Satan, Salmasius and Abdiel,” 107–9. 79 Worden, “Milton’s Republicanism and the Tyranny of Heaven,” 235. 80 Others have promoted similar approaches; see Worden, 243; Nelson, The Hebrew Republic, 46–50. I do not claim to be the first to conceive of such a reading. However, it is the goal of this project to situate such a reading in the context of the theological republicanism that Milton was well-acquainted with. 81 Milton, Paradise Lost, 18. (PL I:39.)

“Authority Usurped” 19

when the same serpent meets Eve in the garden. There, he convinces Eve that if she and Adam

were to partake of the forbidden fruit, despite God’s prohibition, they would become “as gods.”82

This is the primeval (and abiding) temptation: to rebel against God by styling oneself as a god. The

eventual repercussions of this disobedience are disclosed in Michael’s soliloquy in Book XII,

wherein “one shall rise / Of proud ambitious heart, who not content / With fair equality, fraternal

state, / Will arrogate dominion undeserved / Over his brethren.”83 Michael adds that this first

king will—not unlike the Stuarts—“dispossess / Concord and law of Nature from the Earth …

from Heav’n claiming second sovereignty.”84 To this, Adam, ostensibly voicing Milton’s own

appalment at the fiascos of the interregnum and the restoration of the monarchy, offers the

following opprobrium: “O execrable son so to aspire / Above his brethren, to himself assuming /

Authority usurped, from God not given: / He gave us only over beast, fish, fowl / Dominion

absolute; that right we hold / By his donation; but man over men / He made not lord; such title

to himself / Reserving, human left from human free.”85 Adam’s dismay cannot but recall Milton’s

own in The Readie And Easie Way: “I cannot but yet further admire … how any man, who hath the

true principles of justice and religion in him, can presume or take upon him to be a king and lord

over his brethren, whom he cannot but know, whether as men or Christians, to be for the most

part every way equal or superior to himself.”86

Milton does not only discuss humans’ wickedness in assuming the crown, however. That

sinfulness is contrasted with Milton’s portrayal of the good, true king. God is described as a rightful,

82 Milton, 267. (PL IX:708.) 83 Milton, 352. (PL XII:25–28.) 84 Milton, 352. (PL XII:35.) 85 Milton, 353. (PL XII:64-71.) 86 Milton, “The Readie and Easie Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth,” 435. Milton’s 1660 text in turn recalls a brazen passage in Rutherford’s Lex Rex, where he writes: “no man commeth out of the wombe with a Diadem on his head , or a Scepter, in his hand.” Rather, Rutherford says, “men united in a societie may give crown and scepter to this man and not to that man.” The lesson to be drawn from this remark is that the bestowal of authority is always performed on behalf of the people in a society, and for that reason, authority can be rescinded from a ruler. In Rutherford, Lex, Rex, 10.

20 Mary Nickel

righteous king, who creates and sustains, asking merely for recognition as creator and sustainer.

Even Satan himself cannot but admit that God “deserved no such return / From me … What

could be less than to afford him praise, / The easiest recompense, and pay him thanks, / How

due!” 87 God’s rule, furthermore, does not achieve anything for his subjects other than their

happiness; nor are his laws difficult for humans to undertake.88 Rather, given that “he who rules is

worthiest and excels / Them whom he governs,” which Milton’s Abdiel says is a law of nature, it

follows that God is right to rule all.89 When God’s son Jesus is enthroned by God in Book III,

moreover, Jesus assumes his reign with the very humility Milton finds scarce among human royals.

Indeed, it was Jesus’ very willingness to lower himself for the sake of God’s beloved humanity that

occasioned God’s pronouncement that “all ye gods / Adore Him who to compass all this dies! /

Adore the Son and honor Him as Me!”90 The Son does not cling to his authority, but rather is

willing to set it down for the sake of his subjects. Even Gabriel, no monarch but a wielder of power

nevertheless, is contrasted with Satan in his willingness to acknowledge the source of his power.

“Satan, I know thy strength and thou know’st mine,” says Gabriel. “Neither our own, but giv’n.”91

(4.1005) It is clear that no human king could ever be so godly. Thus, we anxiously wait “Until one

greater man / restore us” (1.4-5). In Milton’s characteristic multidimensional style, this phrase from

the first five lines of the text could be, at first glance, interpreted as a panegyric for Charles II. Yet

as the rest of the epic poem makes clear, no human—not even a Lord Protector—can completely

resist the temptation to usurp authority. Milton wanted his readers to be certain: no Stuart could

really restore England. Only God could do that.

87 Milton, Paradise Lost, 106–7. (PL IV:42-43, 46-48.) 88 Milton, 162–63. (PL V:826-831, 842-845.) 89 Milton, 176. (PL VI:176-178.) 90 Milton, 89. (PL III:341-343.) 91 Milton, 133. (PL IV:1006-1007.)

“Authority Usurped” 21

To return to the aforementioned puzzle: we now see clearly that there is little reason to read

Paradise Lost as Milton’s lamentation of or repentance for his collaboration with revolutionary

forces.92 The republicans’ insurrection was not sinful as such. To be sure, Milton was sober minded

about the propensity of any human to yield to the temptation to “set himself in glory ‘bove his

peers,” and the degree to which Parliamentarians themselves so yielded. That, however, was not

his chief concern. The primeval evil, it will be recalled, is not to be found in rebellion against kings

in general, but in rebellion against God, the one true king. There is a remarkable inversion here.

It is true that, on a first pass, a reader might be inclined to hear echoes of Milton’s pamphlet’s in

Satan’s soliloquys. But Satan’s wrongdoing is found in his rebellion against God, his having

“trusted to have equaled the Most High.” Who in Milton’s England resembles Satan in so doing?

Not Milton, but the Stuarts.93

The theological inflection of all these political claims is striking. The politics is grounded in the

theology, and the theology is made concrete in the politics. Norbrook portrays Milton’s view in a

way that echoes Ponet, the author of the Vindiciae, and so many other theological republicans

discussed above: “It is simply invalid to make analogies between heavenly rule and earthly

government.”94 The point is neither solely political or theological. Milton was not so willing to

separate the two, according to Norbrook, and readings of Paradise Lost that depoliticize the poem

fail to appreciate both Milton’s political and theological efforts.95 Each were marshalled in the

service of the other. As Lejosne puts it, “Milton’s treatment of God's heavenly kingship and Satan’s

rebellion can be viewed as complementary elements in his republican strategy … [Milton] made

92 Norbrook puts it more strongly: “Milton certainly regarded the Restoration as a shaming disaster, but to equate it with the Fall would be to give it a metaphysical dignity it did not deserve.” Norbrook, Writing the English Republic, 436. 93 Even Satan himself confesses that he was “Forgetful what from him I still received,”; most royals are not so aware. Milton, Paradise Lost, 107. (PL IV:54.) 94 Norbrook, Writing the English Republic, 477. 95 Norbrook, 437.

22 Mary Nickel

monarchy in Heaven justify republicanism on earth.” 96 Milton’s is no mere republicanism,

therefore, but a fully theological republicanism.97

So it is that Milton decries the subjection of one person by another, on account of humans’

equal status—but with the further descriptor before God. This in contrast to the rightful reign of the

“universal Lord,” who reigns supreme.98 Milton’s analysis suggests the notion—underexplored in

his own work—that not only monarchy, but many other forms of domination amount to, as

Milton’s Adam puts it, “authority usurped.” By no means was John Milton a radical democrat, as

were the Levellers of his time.99 Yet Milton nevertheless contributed to a theological tradition

which, in contraposing human and divine kingship, advocated resistance to domination. That

tradition can rightly be called theological republicanism.

It’s in this tradition that so many modern Christian political activists—including Las Casas, the

Grimké sisters, and Martin Luther King—thought, wrote, and worshipped. That tradition

preceded Milton: it included those religious voices in antiquity who resisted Caesar in their

confession that God (or Christ) is Lord. It included Dominican friars like Las Casas,100 Vitoria, and

Savonarola, who derived a theory of human equality from the theology of the imago dei and the

notion that divine law superseded positive law.101 The tradition continued beyond Milton, too.

96 Lejosne, “Milton, Satan, Salmasius and Abdiel,” 106. 97 Walter Lim helpfully writes on Milton’s “Biblical republicanism,” and his argument is well-grounded. Milton was no mere interpreter, however, and the worldview that he constructs in Paradise Lost and throughout his prose is quite theologically sophisticated. Thus, while Milton was certainly a Biblical republican—like many of the thinkers discussed here—he was also a theological republican. See Lim, John Milton, Radical Politics, and Biblical Republicanism. 98 Milton, Paradise Lost, 145, 233. The phrase appears twice, in PL V:205 and PL VIII:376. 99 We have discussed Lilburne’s theological republicanism above. Winstanley, too, was fond of contraposing divine and human rulership. See Winstanley, The Law of Freedom, and Other Writings, 93, 102, 144, 162, 194, 223. As mentioned above, Winstanley was quite fond of the narrative in I Samuel 8. 100 Las Casas would write in Sobre el título del dominio del rey to Charles V, who had been declared “dominus mundi”: “the only title that Your Majesty has is this: that all, or the greater part of the Indians, wish voluntarily to be your vassals and hold it an honour to be so,” otherwise Charles V’s seizure would violate the ancient Roman principle that what touches all must be agreed by all (Latin: quod omnes tangit ab omnibus tractari et approbari debet). As quoted in Pagden, Lords of All the World, 90. 101 The imago dei doctrine runs the contrapositional logic in reverse, on the patient side, rather than the agent side. The reason human beings ought not dominate one another does not derive from the fact that humans are not gods, and as

“Authority Usurped” 23

Franklin famously proposed that the nascent United States include on their national seal the motto,

“Resistance to Tyrants is Obedience to God.”102 The penultimate article in the 1848 Women’s

Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, signed at the first women’s rights convention, protests that

“[man] has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a

sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.”103 Lincoln echoes the Vindiciae

and Milton: “[t]hose who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves; and, under a just

God, can not long retain it.”104 A century later, in his notes on his reading of II Samuel, King

writes, “no individual is exempt from God’s holy rule, not even the king,” and that, relatedly,

kingship according to Biblical norms must entail a “constitutional, rather than an absolute,

monarchy.”105 On each of these readings, humans’ exercise of power is not identified with the

power of God, but rather is to be limited by it. Of course, adopting that principle doesn’t settle all

other matters. Differences remain between Milton and the Levellers, the suffragettes and the

abolitionists, Lincoln and King. Not all theological republicans agree about how exactly the power

afforded to human leaders will be limited; how leaders should be chosen and held accountable;

how the power to choose and hold leaders accountable should be distributed. Some—rightly, I

think—insist that we also consider how those who uphold or benefit from substantial economic

disparities dominate others, acting as if they were gods. The tradition of theological republicanism

does not resolve these disputes, but it does set the table for discussion.

such do not retain the prerogative of the dominus. Rather, humans ought not dominate one another each human being bears the image of God, and therefore ought never be an object of domination. 102 Franklin, The Compleated Autobiography, 124. 103 As printed in an appendix in McMillen, Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement, 239. 104 Lincoln, Political Writings and Speeches, 90. 105 King, “II Samuel Class Notes,” 3, 22, 32.

24 Mary Nickel

PARTNERSHIPS LOST, PARTNERSHIPS REGAINED

There is a further reason that we ought to pay attention to the theological account I offer here.

When the implications of the tradition I have expounded above are fully appreciated, the case is

made even more forcefully against those who continue to portray Christian theology and

progressive politics as mutually exclusive. We might call advocates of such accounts “Great

Separationists,” in the manner of Mark Lilla’s narrative concerning the “Great Separation”

effected between religion and politics in late modernity.106 Surely, there is reason to be concerned

by the loss of life and rights brought about by the wars of religion and ecclesial persecutions of the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Likewise, there is reason to ensure that there are legal and

institutional bulwarks against the oppression of religious and other conscientious constituencies. It

does not follow, however, that the most effective means for doing so requires jettisoning the

deployment of theological arguments for political ends. That has not been the case in American

history. Whigs, abolitionists, suffragettes, and civil rights activists have each in turn promoted

theological republicanism; denying this history wholly and harmfully fails to appreciate the

commendable religious egalitarian movements that have existed during the entire modern period.

Neither is it the case now.

We might strengthen the case against the Great Separationists by revealing the compatibility

between theological republicanism—the tradition that contraposes divine and human power—on

the one hand, and nontheological republicanism on the other. For if, as theological republicanism

insists, only God’s power may be unlimited, that means that all other forms of the exercise of power,

including that of a monarch or other public official, must be limited. Here is an alternate

justification for the framers’ principle of the separation of powers, which does not compete with

106 Mark Lilla’s The Stillborn God is a favorite whipping-boy of those who seek to make a claim like mine. Perhaps it is a straw man; not many ethicists take his argument seriously. Yet I suspect his view is quite commonplace in broader American society. See Lilla, The Stillborn God.

“Authority Usurped” 25

Montesquieu’s model, but accords with it.107 That God is all-mighty means that a person cannot

be. As Roman private law held, total dominium cannot be shared between two persons.108 If God is

Lord, no one else can claim to be. It becomes apparent here that the fact that God holds unlimited

power is crucially relevant. God’s possession of unlimited power precludes human possession of

the same.

Of course, this doesn’t ease all the Great Separationists’ anxieties about rationality or virtue.

But it nevertheless merits our attention that, in this case, the religious and non-religious views

regarding the separation of powers are not ultimately at cross purposes. It certainly behooves us to

reflect on how their rationales differ—and this paper has aimed to illuminate the theological

reasoning that has underpinned (some) Christians’ resistance to domination. One of the lessons

that emerges here, though, is that Christians’ and other religious adherents’ commitment to what

has been called the “lordship of God” might be more compatible with contemporary republican

democracy than someone like Lilla might concede. By no means is the insinuation of the foregoing

paper that one must stand in the tradition alongside ancient Christians, the author of the Vindiciae,

John Milton, and Martin Luther King to be a republican democrat. Rather, the claim is that

standing in that tradition doesn’t preclude you from being a republican democrat. In fact, it may yield

unique and forceful resources for republican democratic citizenship.109

For the modern American, the word “lord” is archaic. It is simply not used very often in

contemporary American English. With the exception of the occasional use of the phrase “lord

something over someone,” the word “lord” virtually always conjures the Christian identification of

107 Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, 157. (That is, XI.6.) 108 As quoted in the epigraph, from the Roman Digest: “Duorum in solidum dominium esse non posse.” 109 David Decosimo is currently working on a book, No Lord But God: Domination in Christianity and Islam, which will highlight the resources that Christian and Muslim traditions bring to such citizenship.

26 Mary Nickel

God, usually with an upper case “L.” This is no coincidence. Many of the first European settlers

of what would become the United States sought to establish a community free from hereditary

titles, fulfilling the Levellers’ vision of having “no more lords.”110 Indeed, the Constitution, as it

came into force in 1789, outlawed the bestowal of titles of nobility altogether.111 To be sure, the

abolition of lordship did not mean the abolition of domination—in fact, the same section of the

Constitution that outlawed hereditary titles restricted Congress from restricting the slave trade for

at least twenty years.112Yet the declining use of the term “lord” nevertheless manifests the spark

that kindled many of the most well-regarded progressive movements in American history. That

the word “lord” should come to mean God and virtually nothing else was the very aim of the

tradition described above. According to this tradition, only God’s power could be absolute; all

other such exercise of power would thereby necessarily be limited. Else, the power holder would

be acting as if she herself were a god, a blasphemous and unethical premise. No one can “arrogate

dominion undeserved over his brethren,” as Milton wrote, and still have “the true principles of

justice and religion in him.” For, according to the tradition of theological republicanism in which

Milton stood, Christians must confess with the psalmist that “the Lord alone is God.”113

110 Both Richard Overton and Henry Marten adopted the slogan. See Rees, The Leveller Revolution, 126, 242. 111 U.S. Constitution, article 1, section 9. 112 Ibid. 113 Psalm 100:3, passim.

“Authority Usurped” 27

WORKS CITED

Adams, John. “A Defence of the Constitutions

of the United States of America.” In The Political Writings of John Adams, edited by George W. Carey, 105–303. Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 2001.

Birks, Peter. “The Roman Law Concept of Dominium and the Idea of Absolute Ownership.” Acta Juridica, 1985, 1–37.

Bisson, Thomas N. The Crisis of the Twelfth Century: Power, Lordship, and the Origins of European Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Boff, Leonardo. Trinity and Society. Translated by Paul Burns. Eugene, Or.: Wipf & Stock, 2005.

Brandon, William. New Worlds for Old: Reports from the New World and Their Effect on the Development of Social Thought in Europe, 1500-1800. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1986.

Brutus, Stephanus Julius. Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos, or, Concerning the Legitimate Power of a Prince over the People, and of the People over a Prince. Edited by George Garnett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Capp, Bernard. The Fifth Monarchy Men: A Study in Seventeenth-Century English Millenarianism, 2012.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. On the Commonwealth and On the Laws. Edited by James E. G. Zetzel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Dilbeck, D. H. Frederick Douglass: America’s Prophet. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Filmer, Robert. “Patriarcha.” In Patriarcha and Other Writings, edited by Johann Sommerville, 1–68. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Franklin, Benjamin. The Compleated Autobiography. Edited by Mark Skousen. Washington: Regnery Publishing, 2006.

Goodman, Christopher. How Superior Powers Oght to Be Obeyd of Their Subiects: And Wherin They May Lawfully by Gods Worde Be Disobeyed and Resisted. Geneva: John Crispin, 1558.

Goodstein, Laurie. “Religious Liberals Sat Out of Politics for 40 Years. Now They Want in the Game.” The New York Times, June 10, 2017, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/10/us/politics/politics-religion-liberal-william-barber.html.

Greaves, Richard L. Deliver Us from Evil: The Radical Underground in Britain, 1660-1663. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Haggar, Henry. No King but Jesus, or, The Walls of Tyrannie Razed and the Foundations of Unjust Monarchy Discovered to the View of All That Desire to See It. Giles Calvert: London, 1652.

Hartog, Paul, ed. Polycarp’s Epistle to the Philippians and the Martyrdom of Polycarp: Introduction, Text, and Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Henreckson, David P. The Immortal Commonwealth: Covenant, Community, and Political Resistance in Early Reformed Thought. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Hurtado, Larry W. Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

Jenkins, Jack. “How Trump Is Paving the Way for a Revival of the ‘Religious Left.’” Washington Post, December 14, 2016. http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith/wp/2016/12/14/how-trump-is-paving-the-way-for-a-revival-of-the-religious-left/.

Josephus, Flavius. The Jewish War. Edited by E. Mary Smallwood. Translated by G. A. Williamson. London: Penguin Books, 1981.

Kern, Kathi. Mrs. Stanton’s Bible. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

28 Mary Nickel

King, Martin Luther. “II Samuel Class Notes.” The Archive of The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change. Accessed September 24, 2017. http://www.thekingcenter.org/archive/document/ii-samuel-class-notes.

Kittelstrom, Amy. The Religion of Democracy: Seven Liberals and the American Moral Tradition. New York: Penguin Press, 2015.

Laborde, Cécile. Critical Republicanism: The Hijab Controversy and Political Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

———. “Republicanism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies, 513–35. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Laborde, Cécile, and John W. Maynor, eds. Republicanism and Political Theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008.

Lee, Daniel. “Sources of Sovereignty: Roman Imperium and Dominium in Civilian Theories of Sovereignty.” Politica Antica, no. 1 (2012): 79–94.

Lejosne, Roger. “Milton, Satan, Salmasius and Abdiel.” In Milton and Republicanism, edited by David Armitage, Armand Himy, and Quentin Skinner, 106–17. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Lilla, Mark. The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics, and the Modern West. New York: Vintage, 2008.

Lim, Walter S. H. John Milton, Radical Politics, and Biblical Republicanism. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2006.

Lincoln, Abraham. Political Writings and Speeches. Edited by Terence Ball. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Lovett, Frank. A General Theory of Domination and Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Malone, Scott. “‘Religious Left’ Emerging as U.S. Political Force in Trump Era.” Reuters, March 27, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-religion-idUSKBN16Y114.

McKanan, Dan. Prophetic Encounters: Religion and the American Radical Tradition. Boston: Beacon, 2011.

McLaren, Anne. “Rethinking Republicanism: ‘Vindiciae, Contra Tyrannos’ in Context.” The Historical Journal 49, no. 1 (2006): 23–52.

McMillen, Sally G. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Milton, John. “A Defence of the People of England.” In Political Writings, edited by Martin Dzelzainis and Claire Gruzelier, 51–255. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

———. Paradise Lost. Edited by Philip Pullman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

———. “The Readie and Easie Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth.” In John Milton Prose: Major Writings on Liberty, Politics, Religion, and Education, edited by David Loewenstein, 426–47. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

———. “The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates.” In Political Writings, edited by Martin Dzelzainis and Claire Gruzelier, 3–50. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Moltmann, Jürgen. The Trinity and the Kingdom: The Doctrine of God. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1981.

Montesquieu, Charles de Secondat. The Spirit of the Laws. Edited by Anne M. Cohler, Basia Carolyn Miller, and Harold Samuel Stone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Nelson, Eric. The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Norbrook, David. Writing the English Republic: Poetry, Rhetoric and Politics, 1627 - 1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

“Authority Usurped” 29

Pagden, Anthony. Lords of All the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France c. 1500–c. 1800. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Pettit, Philip. Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government. Oxford Political Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Ponet, John. A Shorte Treatise of Politike Pouuer: And of the True Obedience Which Subiectes Owe to Kynges and Other Ciuile Gouernours, with an Exhortacion to All True Naturall Englishe Men. Strasbourg: W. Köpfel, 1556.

Pryor, C. Scott. “Looking for Bedrock: Accounting for Human Rights in Classical Liberalism, Modern Secularism, and the Christian Tradition.” Campbell Law Review 33 (November 17, 2011): 609–40.

Raboteau, Albert J. American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals and Their Struggle for Social and Political Justice. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Rees, John. The Leveller Revolution: Radical Political Organisation in England, 1640-1650. London: Verso, 2016.

Rutherford, Samuel. Lex, Rex: The Law and the Prince, a Dispute for the Just Prerogative of King and People. London: John Field, 1644.

Sharp, Andrew, ed. The English Levellers. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Smith, William, and Charles Anthon. “Dominium.” In A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 421–23. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1843.

Soman, Alfred, ed. Massacre of St. Bartholomew: Reappraisals and Documents. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 2013.

Stout, Jeffrey. Blessed Are the Organized: Grassroots Democracy in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

———. “Religion Unbound: Ideals and Powers from Cicero to King.” Lectures presented at the 2017 Gifford Lectures, Edinburgh, May 2017.

Stuart, James. King James VI and I: Political Writings. Edited by Johann Sommerville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Volf, Miroslav. After Our Likeness: The Church as the Image of the Trinity. Sacra Doctrina. Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans, 1998.

Waldron, Jeremy. “The Image of God: Rights, Reason, and Order.” In Christianity and Human Rights: An Introduction, edited by John Witte and Frank S. Alexander, 216–35. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Weiss, Elaine F. The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote. New York, New York: Viking, 2018.

Winstanley, Gerrard. The Law of Freedom, and Other Writings. Edited by Christopher Hill. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Worden, Blair. “Milton’s Republicanism and the Tyranny of Heaven.” In Machiavelli and Republicanism, edited by Gisela Bock, Quentin Skinner, and Maurizio Viroli, 225–45. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.