arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf ·...

Transcript of arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf ·...

Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application toKondo problems

Yuto Ashida,1, ∗ Tao Shi,2, 3, † Mari Carmen Banuls,3 J. Ignacio Cirac,3 and Eugene Demler4

1Department of Physics, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan2CAS Key Laboratory of Theoretical Physics, Institute of Theoretical Physics,

Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 2735, Beijing 100190, China3Max-Planck-Institut fur Quantenoptik, Hans-Kopfermann-Strasse. 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

4Department of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA

We provide a detailed formulation of the recently proposed variational approach [arXiv:1801.05825] to studyground-state properties and out-of-equilibrium dynamics for generic quantum spin-impurity systems. Moti-vated by the original ideas by Tomonaga, Lee, Low, and Pines, we construct a canonical transformation thatcompletely decouples the impurity from the bath degrees of freedom. By combining this transformation with aGaussian ansatz for the fermionic bath, we obtain a family of variational many-body states that can efficientlyencode the strong entanglement between the impurity and fermions of the bath. We give a detailed derivation ofequations of motions in the imaginary- and real-time evolutions on the variational manifold. We benchmark ourapproach by applying it to investigate ground-state and dynamical properties of the anisotropic Kondo modeland compare results with those obtained using matrix-product state (MPS) ansatz. We show that our approachcan achieve an accuracy comparable to MPS-based methods with several orders of magnitude fewer variationalparameters than the corresponding MPS ansatz. We use our approach to investigate the two-lead Kondo modeland analyze its long-time spatiotemporal behavior and the influence of a magnetic field on the conductance. Theobtained results are consistent with the previous findings in the Anderson model and the exact solutions at theToulouse point.

I. INTRODUCTION

Out-of-equilibrium phenomena in quantum many-bodysystems are an active area of research in both ultracold gases[1–5] and traditional solid-state physics [6–10]. A broad classof problems that correspond to a quantum impurity coupledto the many-body environment are particularly important andhave been at the forefront of condesned matter physics startingwith the pioneering paper by Kondo [11]. They have provencrucial to the understanding of thermodynamic properties instrongly correlated materials [12–16], transport phenomena[17–28] and decoherence [29–31] in nanodevices, and lie atthe heart of formulating dynamical mean-field theory [32](DMFT).

A variational approach is one of the most successful andpowerful approaches for solving many-body problems. Itsguiding principle is to design a family of variational statesthat can efficiently capture essential physics of the quantummany-body system while avoiding the exponential complex-ity of the exact wavefunction. In quantum impurity problems,such variational studies date back to Tomonaga’s treatment[33] of the coupling between mesons and a single nucleon.Soon after that, Lee, Low and Pines [34] (LLP) applied simi-lar approach to the problem of a polaron, a mobile spinless im-purity interacting with phonons. Their key idea is to take ad-vantage of the total-momentum conservation by transformingto the comoving frame of the impurity via the unitary trans-formation

ULLP = e−ix·Pb , (1)

∗ [email protected]† [email protected]

where x is the position operator of the impurity and Pb is thetotal momentum operator of phonons. After employing thetransformation, the conserved quantity becomes the momen-tum operator p of the impurity as inferred from the relation:

U†LLP(p + Pb)ULLP = p. (2)

In the transformed frame, p can be taken as a classical vari-able and thus, the impurity is decoupled from the bath de-grees of freedom, or said differently, its dynamics is com-pletely frozen. This observation naturally motivates the fol-

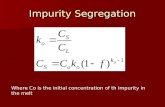

(a)

(b)

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the canonical transformation in-troduced in our variational approach. (a) In the original frame, thelocalized impurity spin can interact with mobile bath particles in anarbitrary manner, generating strong entanglement between the impu-rity spin and bath. (b) After employing the canonical transformation,we can move to the “corotating” frame of the impurity in which theimpurity dynamics can be made frozen at the expense of introducingan interaction among bath particles.

arX

iv:1

802.

0386

1v1

[co

nd-m

at.s

tr-e

l] 1

2 Fe

b 20

18

2

lowing family of variational states:

|Ψtot(ξ)〉 = ULLP|p〉|Ψb(ξ)〉, (3)

where |p〉 is a single-particle state of the impurity havingeigenmomentum p, and |Ψb(ξ)〉 is a bath wavefunction char-acterized by a set of variational parameters ξ. For example,when the bath is given by an ensemble of bosonic excitations,|Ψb〉 can be chosen as a factorizable coherent state, as hasbeen suggested in the original papers by Tomonaga [33] andLee, Low and Pines [34]. Variational approach combining thetransformation (1) with a variety of efficiently parametrizablewavefunctions has been very successful in solving both in-and out-of-equilibrium problems and thus laid the cornerstoneof successive studies in polaron physics [35–54].

Our aim is to generalize this variational approach to yetanother important paradigm in many-body physics: local-ized spin-impurity models (SIM) (Fig. 1). The most funda-mental problem in SIM is the Kondo model [11], a local-ized spin-1/2 impurity interacting with a fermionic bath. Itsequilibrium properties are now theoretically well understoodbased on the results of the perturbative renormalization group[55] (RG), Wilson’s numerical renormalization group [56–62] (NRG) and the exact solution via the Bethe ansatz [63–65]. Yet, its out-of-equilibrium dynamics is still an area ofactive experimental [5–10] and theoretical research [66–106]with many open questions. Earlier works include real-timeMonte Carlo [66–70], perturbative RG [71–75] and Hamil-tonian RG method [76–78], coherent-state expansion [79–81], density-matrix renormalization group [82–89] (DMRG),time-dependent NRG [90–96] (TD-NRG), time evolving dec-imation [97, 98] (TEBD), and analytical solutions [99–106].

In spite of the rich theoretical toolbox for studying thequantum impurity systems, analysis of the long-time dynam-ics remains very challenging. Most theoretical approachessuffer from the same fundamental limitation: they become in-creasingly costly in terms of computational resources at longtimes. For example, it has been pointed out in TD-NRG thatthe logarithmic discretization may cause artifacts in predict-ing long-time dynamics [107], and calculations based on thematrix-product states (MPS) are known to be extremely chal-lenging in the long-time regimes because the large amount ofentanglement forces one to use an exponentially large bonddimension [108]. Another difficulty intrinsic to some of themethods is to understand spatiotemporal dynamics of the bathdegrees of freedom since the latter are often integrated outor represented as a simplified effective bath, in which detailsof the microscopic eigenstates are omitted. Furthemore, thecurrently available methods have been constructed for a spe-cific class of the Kondo impurity model, in which electronsmove ballistically and interaction between the impurity spinand fermions is local. Extending these techniques to the caseof electrons strongly scattered by disorder and nonlocal in-teractions with the impurity spin is not obvious. These chal-lenges motivate us to develop a new theoretical approach toquantum impurity systems. In the accompanying paper [109],we introduce a new canonical transformation that is the core

of the proposed variational approach and provide strong evi-dence for the validity of our approach to correctly describe in-and out-of-equilibrium properties of SIM.

In this paper, we present comprehensive details of the pro-posed variational approach. For the sake of completeness,we first provide the construction of the new transformationthat generates the entanglement between the impurity and thebath. In contrast to the LLP transformation (1) of going intothe comoving frame of the mobile spinless impurity, such aconstruction of the canonical transformation in SIM is not ob-vious due to the SU(2)-commutation relation of the impurityspin operators. We discuss a general approach to construct-ing such transformations in this paper. We then combine thetransformation with Gaussian states to obtain a family of vari-ational states that can efficiently capture the impurity-bath en-tanglement. We provide a set of nonlinear equations of mo-tions for the covariance matrix to study ground-state and out-of-equilibrium properties of a generic SIM. We benchmarkour approach by applying it to the anisotropic Kondo modeland compare results with those obtained using MPS ansatz.We also analyze out-of-equilibrium dynamics and transportproperties in the two-lead Kondo model and demonstrate thatour approach can be used to compute the long-time spatiotem-poral dynamics and the influences of the external magneticfield on the conductance. The obtained results are consistentwith the previous studies in the Anderson model [84, 95] andthe exact solutions at the Toulouse point [106].

This paper is organized as follows. In Sec. II, we presenta general concept of our variational approach to SIM. In par-ticular, we discuss the canonical transformation introduced inRef. [109] that decouples the impurity from the bath degreesof freedom. We then derive the equations of motions for thecovariance matrix of fermionic Gaussian states that describethe ground-state properties and real-time evolutions of SIM.In Sec. III, we apply our theory to the anisotropic Kondomodel and benchmark it with MPS-based calculations. InSec. IV, we analyze transport dynamics in the two-lead Kondomodel in further detail and reveal long-time spatiotemporaldynamics and magnetic effects on the conductance. Finally,we summarize the results in Sec. V.

II. GENERAL FORMALISM

A. Canonical transformation

We first formulate our variational approach to SIM in a gen-eral way. The key idea is to introduce a new canonical trans-formation that completely decouples the impurity and the bathdegrees of freedom for a generic spin-1/2 impurity Hamilto-nian H by employing its parity symmetry P, i.e., [H, P] = 0

with P2 = 1. Specifically, we aim to find a unitary trans-formation U that maps this parity operator P to an impurityoperator as (c.f. Eq. (2))

U†PU = n · σimp, (4)

where σimp = (σximp, σyimp, σ

zimp)T is a vector of the impu-

rity spin-1/2 operator and n is some specific direction defined

3

by a three dimensional real vector. It then follows that in thetransformed frame the Hamiltonian commutes with the impu-rity operator [U†HU ,n · σimp] = 0 such that the impuritydynamics is frozen, i.e., the transformed Hamiltonian condi-tioned on a classical variable n · σimp = ±1 only containsthe bath degrees of freedom. The price that one pays for de-coupling the impurity spin is the appearance of nonlocal mul-tiparticle interactions between the bath degrees of freedom.In spite of the seeming complexity of the fermionic interac-tions in the decoupled frame, we show that their dynamicscan be efficiently described using Gaussian variational wave-functions, which require the number of parameters that growsat most polynomially with the system size.

In this paper, we apply this approach to a spin-1/2 impurityinteracting with a fermionic bath:

H =∑lmα

hlmΨ†lαΨmα −hz2σzimp

+1

4

∑γ=x,y,z

σγimp

∑lmαβ

gγlmΨ†lασγαβΨmβ , (5)

where Ψ†lα (Ψlα) is a fermionic creation (annihiliation) op-erator corresponding to a bath mode l = 1, 2, . . . , Nf andspin-z component α =↑, ↓, hlm is an arbitrary Nf ×Nf Her-mitian matrix describing a single-particle Hamiltonian of abath, and hz is a magnetic field acting on the impurity. Thefirst term describes a noninteracting bath, the second term de-scribes a local magnetic effect acting on the impurity, and thethird term characterizes the interaction between the impurityand the bath. The impurity-bath couplings are determined byNf × Nf Hermitian matrices gγlm labeled by γ = x, y, z andcan in general be anisotropic and long-range. While the in-teraction leads to strong impurity-bath entanglement, we notethat it can also generate entanglement between bath modessince the ones that interact with the impurity are not diagonalwith respect to the eigenbasis of bath Hamiltonian hlm in gen-eral. The magnetic-field term acting on the bath can be alsoincluded; we omit that for simplicity.

Our canonical transformation relies on the parity symme-try hidden in the Hamiltonian (5). To unveil this symmetry,we introduce the operator P = σzimpPbath with a bath parityoperator

Pbath = e(iπ/2)(∑

l σzl +N) = eiπN↑ , (6)

where N is the total particle number in the bath, σγl =∑αβ Ψ†lασ

γαβΨlβ (γ = x, y, z) is a spin-density operator with

a bath mode l, and N↑ is the number of spin-up fermions.These operators satisfy P2

bath = P2 = 1. We observe thatthe Hamiltonian (5) conserves P, i.e., [H, P] = 0. This corre-sponds to the symmetry under the rotation of the entire systemaround z axis by π, which maps both impurity and bath spinsas P−1σx,yP = −σx,y while it keeps P−1σzP = σz .

We employ this parity conservation to construct the disen-tangling transformation U satisfying

U†PU = σximp (7)

such that the impurity spin turns out to be a conserved quantityin the transformed frame. Here we choose n = (1, 0, 0)T inEq. (4); other choices will lead to the same class of variationalstates. We define a unitary transformation U as

U = exp

[iπ

4σyimpPbath

]=

1√2

(1 + iσyimpPbath

). (8)

Employing this transformation, we arrive at the followingtransformed Hamiltonian ˆH= U†HU :

ˆH=∑lmα

hlmΨ†lαΨmα −hz2σximpPbath

+1

4

∑lmαβ

gxlmσximpΨ†lασ

xαβΨmβ

+1

4

∑lmαβ

(−igylmσ

y+gzlmσximpσ

z)αβ

PbathΨ†lαΨmβ . (9)

As expected from the construction, the impurity spin com-mutes with the Hamiltonian [ ˆH, σximp] = 0, and thus we cantake the impurity operator as a conserved number σximp = ±1in the transformed frame. Decoupling of the impurity spincame at the cost of introducing interactions among the bathparticles. Note that these interactions are multiparticle andnonlocal, as can be seen from the form of the operator Pbath.The appearance of the bath interaction can be interpreted asspin exchange between fermions via the impurity spin. Thisis analogous to the case of the mobile spinless impurity [34],where a nonlocal phonon-phonon interaction is introduced af-ter transforming to the comoving frame of the impurity via theLLP transformation. We emphasize that the elimination of theimpurity relies only on the elemental parity symmetry in theoriginal Hamiltonian and thus should have a wide applicabil-ity.

It follows from Eq. (9) that for the even bath-particle num-ber N and the zero magnetic field hz = 0, the Hamiltonianhas two degenerate equivalent energy sectors correspondingto the conserved quantity σximp = ±1 in the transformedframe. This is because the two sectors in Eq. (9) can be ex-actly related via the additional unitary transformation Uybath =

e(iπ/2)∑

l σyl , which maps the bath spins as σx,zl → −σx,zl . To

our knowledge, such an exact spectrum degeneracy hidden ingeneric SIM has not been pointed out except for some specificcases that are exactly solvable via the Bethe ansatz [63–65] orat the Toulouse point [110].

The explicit form of variational states is (c.f. Eq. (3))

|Ψ〉 = U |±x〉imp|Ψb〉= |↑〉impP±|Ψb〉 ± |↓〉impP∓|Ψb〉, (10)

where |±x〉imp represents the eigenstate of σximp with eigen-value ±1, |Ψb〉 represents a bath wavefunction, and P± =

(1 ± Pbath)/2 is the projection onto the subspace with evenor odd number of spin-up fermions. As we will see later,this form of variational wavefunction can naturally capture thestrong impurity-bath entanglement, which is an essential fea-ture of, for example, the formation of the Kondo singlet.

4

B. Variational time-evolution equations

1. Fermionic Gaussian states

To solve SIM efficiently, we have to introduce a fam-ily of variational bath wavefunctions that can approximatethe ground state and real-time evolutions governed by theHamiltonian (9) while they are simple enough so that calcu-lations can be done in a tractable manner. In the decoupledframe, we choose variational many-body states for the bathas fermionic Gaussian states [52, 111–113]. It is convenientto introduce the Majorana operators ψ1,lα = Ψ†lα + Ψlα andψ2,lα = i(Ψ†lα−Ψlα) satisfying the anticommutation relation{ψξ,lα, ψη,mβ} = 2δξηδlmδαβ with ξ, η = 1, 2. We describethe bath by a pure fermionic Gaussian state |ΨG〉 that is fullycharacterized by its 4Nf × 4Nf covariance matrix Γ [111–113]:

Γ =i

2

⟨[ψ, ψ

T]⟩

G, (11)

where (Γ)ij = −(Γ)ji ∈ R is real-antisymmetric and Γ2 =−I4Nf

for pure states with Id being the d × d unit matrix.Here, 〈· · · 〉G denotes an expectation value with respect to theGaussian state |ΨG〉, and we introduced the Majorana opera-tors ψ = (ψ1, ψ2)T, where we choose the ordering of a rowvector ψξ with ξ = 1, 2 as

ψξ = (ψξ,1↑, . . . , ψξ,Nf↑, ψξ,1↓, . . . , ψξ,Nf↓). (12)

We can explicitly write the bath state as

|ΨG〉 = e14 ψ

TXψ|0〉 ≡ UG|0〉, (13)

where we define the Gaussian unitary operator by UG and in-troduce a real-antisymmetric matrix (X)ij = −(X)ji ∈ R.The latter can be related to Γ via

Γ = −Ξσ (Ξ)T, (14)

where Ξ = eX and σ = iσy ⊗ I2Nf. It will be also useful to

define the 2Nf×2Nf correlation matrix:

Γf = 〈Ψ†Ψ〉G (15)

in terms of Dirac fermions

Ψ = (Ψ1↑, . . . , ΨNf↑, Ψ1↓, . . . , ΨNf↓). (16)

2. Imaginary- and real-time evolutions

We approximate the exact time evolution of a bath wave-function |Ψb〉 by projecting it onto the manifold spanned bythe family of variational states. This can be done by employ-ing the time-dependent variational principle [113–116], whichallows us to study ground-state properties via the imaginary-time evolution and also out-of-equilibrium dynamics via thereal-time evolution. Let us first formulate the former one.

The imaginary-time evolution

|Ψb(τ)〉 =e−

ˆHτ |Ψb(0)〉∥∥∥e− ˆHτ |Ψb(0)〉∥∥∥ (17)

gives the ground state in the asymptotic limit τ → ∞ ifthe initial seed state |Ψb(0)〉 has a non-zero overlap with theground state. Differentiating Eq. (17), we obtain the equationof motion

d

dτ|Ψb(τ)〉 = −( ˆH − E)|Ψb(τ)〉, (18)

where E = 〈Ψb(τ)| ˆH|Ψb(τ)〉 represents the mean energy.If we consider the covariance matrix Γ of the Gaussian state|ΨG〉 to be the time-dependent variational parameters, theirimaginary-time evolution equation can be obtained by mini-mizing its deviation ε from the exact imaginary-time evolu-tion:

ε =

∥∥∥∥ ddτ |ΨG(τ)〉+ ( ˆH − Evar)|ΨG(τ)〉∥∥∥∥2

,

(19)

where Evar = 〈ΨG(τ)| ˆH|ΨG(τ)〉 is the variational energy.This is formally equivalent to solving the projected differen-tial equation:

d

dτ|ΨG(τ)〉 = −P∂Γ( ˆH − Evar)|ΨG(τ)〉, (20)

where P∂Γ is the projector onto the subspace spanned by tan-gent vectors of the variational manifold. On the one hand, theleft-hand side of Eq. (20) gives

d

dτ|ΨG(τ)〉= UG

(1

4: ψ

TΞT dΞ

dτψ :+

i

4Tr

[ΞT dΞ

dτΓ

])|0〉,

(21)

where : : represents taking the normal order of the Dirac op-erators Ψ and Ψ†. On the other hand, we can write the right-hand side of Eq. (20) as:

−( ˆH − Evar)|ΨG(τ)〉 = −(i

4: ψ

TΞTHΞψ : +δO

)|0〉,

(22)

whereH = 4δEvar/δΓ is the functional derivative of the vari-ational energy [116] and δO denotes the cubic and higher or-der contributions of ψ that are orthogonal to the tangentialspace and thus will be projected out by P∂Γ in Eq. (20). Com-paring Eqs. (21) and (22), and using Eq. (14), we can uniquelydetermine the imaginary time-evolution equation of the co-variance matrix Γ as [113, 116]

dΓ

dτ= −H− ΓHΓ, (23)

5

which guarantees that the variational energy Evar monotoni-cally decreases and the variational ground state is achieved inthe limit τ →∞. In this limit, the error ε in Eq. (19) is equiv-alent to the variance of the energy in the reached ground stateand can be used as an indicator to check the accuracy of thevariational state.

In the similar way, we can derive the equation of motion forΓ in the real-time evolution

|Ψb(t)〉 = e−iˆHt|Ψb(0)〉. (24)

The projection

d

dt|ΨG(t)〉 = −iP∂Γ

ˆH|ΨG(t)〉 (25)

of the Schrodinger equation on the variational manifold leadsto the following real-time evolution equation of the covariancematrix Γ [113, 116]:

dΓ

dt= HΓ− ΓH. (26)

C. Functional derivative of variational energy

To analytically establish the variational time-evolutionequations (23) and (26) of the covariance matrix Γ, we haveto obtain the functional derivative H = 4δEvar/δΓ of thevariational energy. In this subsection, we give its explicitanalytical expression. First of all, we write the expectationvalue Evar = 〈 ˆH〉G of the Hamiltonian (9) with respect to thefermionic Gaussian state as

Evar =∑lmα

hlm(Γf )lα,mα −hz2σximp〈Pbath〉G

+1

4

∑lmαβ

gxlmσximpσ

xαβ(Γf )lα,mβ

+1

4

∑lmαβ

(−igylmσ

y+ gzlmσximpσ

z)αβ

(ΓPf )lα,mβ ,(27)

where we condition the impurity operator on a classical num-ber σximp = ±1 and introduce the 2Nf×2Nf matrix contain-

ing the parity operator as ΓPf = 〈PbathΨ

†Ψ〉G. The values of

〈Pbath〉G and ΓPf can be obtained [116] as

〈Pbath〉G = (−1)Nf Pf

[ΓF2

], (28)

and

ΓPf=

1

4〈Pbath〉G

×Σz(I2Nf,−iI2Nf

)Υ−1(Γσ − I4Nf

)( I2Nf

iI2Nf

), (29)

where Pf denotes the Pfaffian and the matrices

ΓF =√

I4Nf+ Λ Γ

√I4Nf

+ Λ− (I4Nf− Λ)σ, (30)

Υ = I4Nf+

1

2

(Γσ − I4Nf

) (I4Nf

+ Λ), (31)

are defined by Λ = I2 ⊗ Σz and Σz = σz ⊗ INf. We recall

that the matrix σ is defined below Eq. (14).Since the first and third terms in the Hamiltonian (9) are

quadratic, we can write them exactly in the Majorana basis asiψ

TH0ψ/4 with

H0 = iσy ⊗ [I2 ⊗ hlm + (σximp/4)σx ⊗ gxlm], (32)

where hlm and gxlm are understood to beNf×Nf real matrices.Thus, the functional derivative H = 4δEvar/δΓ of the meanenergy (27) is given by

H=H0 +δ

δΓ

[−2hzσ

ximp〈Pbath〉G + Tr(STΓP

f )], (33)

where we introduce the matrix

S = −iσy ⊗ gylm + σximpσz ⊗ gzlm. (34)

Taking the derivatives of 〈Pbath〉G and ΓPf with respect to the

covariance matrix Γ in Eq. (33), we finally obtain the analyti-cal expression of the functional derivativeH:

H=H0+

[hzσ

ximp〈Pbath〉G−

1

2Tr(STΓP

f )

]P

− i4〈Pbath〉G A

[VSTΣzV†

], (35)

where A[M ] = (M −MT)/2 denotes the matrix antisym-metrization and we introduce the matrices

P =√

I4Nf+ ΛΓ−1

F

√I4Nf

+ Λ, (36)

V = (ΥT)−1

(I2Nf

iI2Nf

). (37)

Integrating Eqs. (23) and (26) with the general form (35) of thefunctional derivative, one can study ground-state propertiesand out-of-equilibrium dynamics of SIM on demand.

III. APPLICATION TO THE ANISOTROPIC KONDOMODEL

A. Model

We benchmark our general variational approach by apply-ing it to the anisotropic Kondo model and comparing the re-sults with those obtained using matrix-product state (MPS)[117]. The one-dimensional Kondo Hamiltonian is given by

HK =−thL∑

l=−L

(c†lαcl+1α+h.c.

)+

1

4

∑γ

Jγ σγimpc

†0ασ

γαβ c0β ,

(38)

6

where c†lα (clα) creates (annhilates) a fermion with position land spin α. The spin-1/2 impurity σγimp locally interacts withparticles at the impurity site l = 0 via the anisotropic cou-plings Jx,y = J⊥ and Jz = J‖. We choose the unit th = 1and the summations over α, β are understood to be contractedhereafter. This model shows a quantum phase transition [29]between an antiferromagnetic (AFM) phase and a ferromag-netic (FM) phase. The former leads to the formation of thesinglet state between the impurity and bath spins, leading tothe vanishing impurity magnetization 〈σzimp〉 = 0. The latterexhibits the triplet formation and the impurity magnetizationtakes a non-zero, finite value in general.

To apply our general formalism in Sec. II, we note that inthe Hamiltonian (38) only the symmetric bath modes couple tothe impurity spin. We thus identify the fermionic bath modesΨ as

Ψ0α = c0α, Ψlα =1√2

(clα + c−lα) (39)

with l = 1, 2, . . . , L. The corresponding bath Hamiltonianhlm is given by the following (L+1)×(L+1) hopping matrixh1 of the single lead:

h1 = (−th)

0√

2 0 · · · 0√

2 0 1 0...

0 1 0 1...

... 0 1. . . 1

0 · · · · · · 1 0

. (40)

The couplings gγlm are identified as the local Kondo interac-tion Jγδl0δm0. We set the magnetic field to be zero hz = 0for simplicity.

Solving Eqs. (23) and (26) with the functional deriva-tive (35), we obtain the covariance matrix Γ correspondingto the ground state and the real-time dynamics. The associ-ated observables can be efficiently calculated in terms of thecovariance matrix. For example, the impurity-bath spin corre-lations for each direction are obtained from

χxl =1

4〈σximpσ

xl 〉 =

1

4σximpσ

xαβ(Γf )lα,lβ , (41)

χyl =1

4〈σyimpσ

yl 〉 =

1

4(−iσyαβ)(ΓP

f )lα,lβ , (42)

and

χzl =1

4〈σzimpσ

zl 〉 =

1

4σximpσ

zαβ(ΓP

f )lα,lβ , (43)

where 〈· · · 〉 denotes an expectation value with respect towavefuntion in the original frame. The impurity magnetiza-tion can be obtained from

〈σzimp〉 = σximp〈Pbath〉G = σximp(−1)Nf Pf

[ΓF2

], (44)

where we use Eq. (28) in the second equality.

B. Structure of variational ground state

In this subsection, we discuss how the entanglement in theKondo-singlet state is naturally encoded in our variationalground state. It is useful to choose a correct sector of varia-tional manifold by specifying an appropriate conserved quan-tum number. In particular, if the initial seed state is an eigen-state of the total spin-z component σztot = σzimp + σzbath withσzbath =

∑Ll=0 σ

zl , its value σztot is conserved through the

imaginary-time evolution due to [σztot, H] = 0.To show the singlet behavior explicitly, we investigate the

variational ground state by choosing the initial seed state inthe sector σztot = 0. As inferred from the definition of thebath parity (6) and the variational ansatz (10) conditioned onthe sector σximp = 1, in the original frame the spin-up im-purity | ↑〉 is coupled to the bath with even number of spin-up fermions N↑ (correspondingly, odd number of spin-downfermions N↓ = N↑ + 1), while the spin-down impurity |↓〉is coupled to the bath having odd (even) number of spin-up(-down) fermions N↑ (N↓ = N↑ − 1). It then follows that theprojected states |Ψ±〉 = P±|Ψb〉, which couple with the im-purity spin-up and -down states, respectively (c.f. Eq. (10)),are eigenstates of σzbath as follows:

σzbath|Ψ±〉 = ∓|Ψ±〉. (45)

In the deep AFM phase with σztot = 0, one can numericallyverify that the projected states |Ψ±〉 satisfy the following re-lations:

|||Ψ±〉|| = 1/2, 〈Ψ−| σ+bath |Ψ+〉 = −1/2. (46)

This automatically results in the vanishing of the impuritymagnetization 〈σzimp〉 = 0 and underscores that the variationalground state is indeed the singlet state between the impurityand the bath spins:

|ΨAFM〉 =1√2

(|↑〉imp|Ψ↓〉 − |↓〉imp|Ψ↑〉) , (47)

where we use Eq. (10) and denote the normalized spin-1/2bath states as |Ψ↓〉 =

√2|Ψ+〉 and |Ψ↑〉 = −

√2|Ψ−〉.

It is worthwhile to mention that, if we choose |Ψb〉 inEq. (10) as a single-particle excitation on top of the Fermisea, Eq. (47) reproduces the variational ansatz that has beenoriginally suggested by Yosida [118] and then later general-ized to the Anderson model [119] and resonant-state approach[120]. This variational state has been recently revisited [121]and shown to contain the majority of the entanglement in theground state of the Kondo model, indicating the ability of ourvariational states to encode the most significant part of theimpurity-bath entanglement. Yet, we emphasize that our vari-ational ansatz goes beyond such a simple ansatz since we con-sider the general Gaussian state that takes into account all thecorrelations between two fermionic operators. Such a flexibil-ity becomes particularly important when we consider, for ex-ample, out-of-equilibrium dynamics or FM equilibrium prop-erties.

7

Figure 2. Comparison of ground-state impurity-bath spin correlations χzl = 〈σz

impσzl 〉/4 calculated from the matrix-product state (MPS,

red crosses) and our non-Gaussian variational state (NGS, blue circles). The inset panels show the absolute values of the difference betweenthe correlations calculated from the two methods. The dimensionless Kondo couplings (j‖, j⊥) are set to be (a) (−0.1, 0.4), (b) (0.1,0.4), (c)(-0.4,0.1) and (d) (0.4,0.1) as indicated in the left inset panel of (a). System size is L = 100 and the bond dimension of MPS is D = 260.

In practice, we also monitor the formation of the Kondo-singlet formation by testing the sum rule [58] of the impurity-bath spin correlation χl = 〈σimp · σl〉/4:

L∑l=0

χl =1

8〈σ2

tot − σ2imp − σ

2bath〉 = −3

4. (48)

In the discussions below, we checked that this sum rule hasbeen satisfied with an error below 0.5% in AFM regime withJ‖ > 0. These observations clearly show that our varia-tional states successfully capture the most important featureof Kondo physics in an efficient manner, i.e., with a numberof variational parameters growing only quadratically with thesystem size L.

C. Comparisons with matrix-product states

1. Matrix-product states

To further test the accuracy of our approach, we compareour variational results with those obtained using a MPS ansatz.For the sake of completeness, here we describe the MPS-based method applied to the Kondo model. The MPS ansatzfor a generic N -body quantum system takes the form

|ΨD〉=∑{ik}

Tr(A[0]i0A[1]i1 · · ·A[N − 1]iN−1

)|i0i1 · · · iN−1〉,

(49)

where for each site k, {|ik〉} represents a finite basis of thecorresponding Hilbert space, and A[k]ik is a D × D matrixlabelled by an index ik. We note that, with open boundaryconditions, the first and last matrices reduce toD-dimensionalvectors. The parameter D is known as bond dimension, anddetermines the number of variational parameters in the ansatz.The MPS ansatz can be used to approximate ground states andlow lying excitations of strongly correlated quantum many-body systems. It can also be employed to simulate real-timedynamics and lies at the basis of the DMRG method [108,117, 122–126].

In order to find a MPS approximation to the ground stateof Hamiltonian (38), we express the Hamiltonian as a ma-trix product operator (MPO) [127]. For the sake of con-venience, we actually work in terms of the bath modes inEq. (39) and map them to spins using a Jordan-Wigner trans-formation such that Ψl↑ = Πk<l(σ

z2kσ

z2k+1)σ−2l and Ψl↓ =

Πk<l(σz2kσ

z2k+1)σz2lσ

−2l+1. A MPS approximation to the

ground state is found by variational minimization of the en-ergy over the family of MPS with fixed bond dimension D,

|Ψ0〉 = argmin〈ΨD|H|ΨD〉〈ΨD|ΨD〉

. (50)

To solve the minimization, an alternating least squares strat-egy is applied, where all tensors but one are fixed, and theproblem is transformed in the optimization for a single localtensor. Once the local problem is solved, the optimization isrepeated with respect to the next site in the chain and so onuntil the end of the chain is reached. The sweeping is iterated

8

back and forth over the chain until the energy of the groundstate is converged to the desired precision level (see e.g., Refs.[108, 117] for details of technical details). The algorithm pro-duces a MPS candidate for the ground state, and local expec-tation values and correlations can be efficiently evaluated. Toimprove the precision, the procedure can be repeated with in-creasing bond dimension using the previously found state asthe initial guess. Also the convergence criterion can be re-fined for more accurate results. For our comparisons we set aconvergence cutoff of 10−8-10−6.

We can also use the MPS ansatz for a time-evolved stateafter the quench protocol considered in this paper (see expla-nations in the next subsection). Although the initial state, i.e.,the Fermi sea of the bath (c.f. Eq. (51) below), is not an ex-act MPS, we can find a good approximation to it by runningthe ground state algorithm described above in the absence ofthe impurity. Then, the full initial state obtained by a ten-sor product with the polarized impurity is evolved with thefull Hamiltonian. To this end, the evolution operator is ap-proximated by a Suzuki-Trotter decomposition [128, 129] asa product of small discrete time steps, each of which can bewritten as a product of MPO [125, 127, 130]. The action ofthe latter on the state is then approximated by a new MPSthat represents the evolved state. This is achieved again byan alternating least squares algorithm and minimizing the dis-tance between the MPS and the result of each evolution step(c.f. Refs. [108, 117]). In general, real-time evolutions mayquickly increase the entanglement in the state, and to main-tain an accurate MPS approximation the bond dimension ofthe ansatz will need to grow with time. In order to keep trackof the accuracy of the simulations, we check convergence ofthe results at different times when we repeat the simulationswith increasing bond dimension.

2. Benchmark results

We plot in Fig. 2 the ground-state impurity-bath spin cor-relations χzl = 〈σzimpσ

zl 〉/4 of the anisotropic Kondo model

in four different regimes of the phase diagram (see the left in-set of Fig. 2(a)). We use the dimensionless Kondo couplingsj‖,⊥ = ρFJ‖,⊥ with ρF = 1/(2πth) being the density ofstates at the Fermi energy. Our variational results not onlycorrectly reproduce the formations of the singlet (triplet) pairbetween the impurity and bath spins in the AFM (FM) phase,but they also show quantitative agreement with MPS resultswith a deviation which is at most a few percent of the valueat the impurity site. We find that the agreement is particularlygood in the deep FM and AFM regimes (see Figs. 2(c) and(d)), where the difference is below 1%.

We also compare the ground-state energy Evar (Fig. 3(a))and the corresponding magnetization 〈σzimp〉 (Fig. 3(b)) acrossthe phase transition line (see the inset of Fig. 3(b)). In the FMphase, we observe that our variational results agree very wellwith the MPS results, with an error below 0.5%. Remarkably,our ansatz achieves slightly lower energies deep in the phase(the left inset of Fig. 3(a)). Close to the phase boundary, weobserve the largest deviation with respect to the MPS ansatz

j ||

j ||

grou

nd-s

tate

ene

rgy

mag

netiz

atio

n

(a)

(b)

FM

AFM

j

0 j ||

Figure 3. Comparison of (a) the ground-state energy and (b) im-purity magnetization across the phase boundary of the anisotropicKondo model calculated from the matrix-product state (MPS, reddashed line with crosses) and our non-Gaussian variational state(NGS, blue solid line with circles). In (a), we plot the variational en-ergiesEvar−Ef relative to a constant ground-state energyEf of freefermions on the lattice. The left and right insets magnify the ground-state energies in the FM phase and close to the phase boundary, re-spectively. We choose the dimensionless Kondo coupling j⊥ = 0.5and vary j‖ from −1 to 1 as schematically illustrated in the inset of(b). The calculations are done in the sector σz

tot = 0. System size isL = 200 and the bond dimension of MPS is D = 280.

both in energy (the right inset of Fig. 3(a)) and magnetization(Fig. 3(b)), with our ansatz showing a residual magnetizationclose to the transition. Finally, in the deep AFM phase (j‖ >0), the ground-state energies calculated from both methodsagain agree well with an error typically below 0.5%. In thisregime, the corresponding residual magnetization is 〈σzimp〉 'O(10−4) in MPS and O(10−5) in our variational method. Weattribute the small discrepancies between the two methods tothe finite values of the system size L and the bond dimensionD.

The comparison to the MPS results shows the great effi-ciency of our variational approach. The number of variationalparameters in MPS is approximately 4LD2 with D being thebond dimension, while that of our variational ansatz is 4L2.Since the bond dimension D in the calculations is typically

9

mag

netization

time time

(a)

mag

netization

(b)

AFM

FM

AFM

FM

Figure 4. Comparison of dynamics of the impurity magnetizationcalculated from the matrix-product state (MPS, red chain curve) andour non-Gaussian variational state (NGS, blue solid curve) at (a)SU(2)-symmetric points and (b) strongly anisotropic regimes. Thedimensionless Kondo couplings are (a) j‖ = j⊥ = ±0.35 in theSU(2)-symmetric antiferromagnetic (AFM) and ferromagnetic (FM)phases, respectively, and (b) (j‖, j⊥) = (0.1, 0.4) and (−0.4, 0.1)in the anisotropic AFM and FM phases, respectively. The inset in(b) magnifies the dynamics in FM phase. System size is L = 100and the bond dimension of the MPS for the different cases varies inD ∈ [220, 260], for which we checked that the results are convergedwithin the time window shown in the plots.

taken to be 200-300, our variational approach can achieve theaccuracy comparable to MPS with two or three orders of mag-nitude fewer variational parameters, and shorter CPU time ac-cordingly, than the corresponding MPS ansatz. This indicatesthat our variational ansatz successfully represents the ground-state wavefunction of SIM in a very compact way.

Finally, to complete the benchmark test in the anisotropicKondo model, we compare the real-time dynamics of the im-purity magnetization calculated with a MPS algorithm and ourvariational method. We consider the initial state

|Ψ(0)〉 = |↑〉imp|FS〉, (51)

where |FS〉 is the half-filled Fermi sea of the lead. At timet = 0, we then drive the system by suddenly coupling theimpurity to the lead.

First, we show the results at the SU(2)-symmetric points ofAFM and FM phases (Fig. 4(a)), which are usually of interestin condensed matter systems. The magnetization eventuallyrelaxes to zero in the AFM phase as a result of the Kondo-singlet formation, while it remains nonvanishing and exhibitsoscillations in the FM phase. The long-lasting fast oscillationfound in the FM phase comes from a high-energy excitation ofa fermion from the bottom of the band and its period 2π~/D ischaracterized by the bandwidthD = 4th (note that we choosethe unit ~ = 1 and th = 1 in the plots). Since the impurity spinwill be decoupled from the bath degrees of freedom in the low-energy limit in the FM phase (see RG flows in Fig. 3(b) inset),the oscillation can survive even in the long-time limit. TheMPS and our variational results show quantitative agreementwith an error that is at most O(10−2). Second, we comparethe results in the strongly anisotropic AFM and FM regimes(Fig. 4(b)). In the short and intermediate time regimes, theresults obtained using MPS and our variational states exhibita good agreement. In the long-time regime (t & 10), the two

methods show a small discrepancy that is about O(6× 10−2)in the AFM phase andO(1×10−2) in the FM phase. Yet, theystill share the qualitatively same features such as the exponen-tial relaxation in the AFM regime and long-lasting oscillationscharacterized by the bandwidth in the FM regime.

IV. APPLICATION TO THE TWO-LEAD KONDO MODEL

A. Model

We next apply our approach to investigate out-of-equilibrium dynamics and transport properties in the two-leadKondo model [72] (Fig. 5), where the localized spin impu-rity is coupled to the centers of the left and right leads via theisotropic Kondo coupling. The Hamiltonian is

Htwo =∑lη

[−th

(c†lηαcl+1ηα+h.c.

)+ eVη c

†lηαclηα

]+J

4

∑ηη′

σimp · c†0ηασαβ c0η′β −hz2σzimp, (52)

where c†lηα (clηα) creates (annihilates) a fermion with positionl and spin α on the left (η = L) or right (η = R) lead, thehopping th = 1 sets the energy unit, J is an isotropic Kondocoupling strength, and eVη are chemical potentials for eachlead. The spin indices α, β are understood to be contracted asusual.

In the same manner as in the single-lead case in the previoussection, only the following symmetric modes are coupled tothe impurity:

Ψ0η,α = c0ηα, Ψlη,α =1√2

(clαη + c−lηα) (53)

Figure 5. Schematic figure of the two-lead Kondo model. Thelocalized spin-1/2 impurity is coupled with the centers of the left (L)and right (R) leads via an isotropic Kondo coupling J . The bathfermions can move within each lead with a hopping th. The biaspotentials VL,R are applied to the left and right leads. The time-evolutions of the current I(t) between the two leads, the impuritymagnetization 〈σz

imp(t)〉, and spatially resolved bath properties canbe efficiently calculated by our variational method.

10

Figure 6. Out-of-equilibrium dynamics in the two-lead Kondo model. (a) The time evolutions of the current I(t) (black solid curve) and theimpurity magnetization 〈σz

imp(t)〉 (blue chain curve). The current is plotted in unit of eth/h. After the quench of the chemical potentials andthe Kondo coupling at t = 0, the current quickly reaches a steady value and exhibits the plateau, while the impurity magnetization quicklydecays to zero, indicating the Kondo-singlet formation. The current suddenly flips its sign in the middle of the time evolution at which thedensity wave returns to the impurity site after reflecting at the end of each lead. In this regime, the magnetization passingly takes a largenon-zero value. (b) and (c) Spatiotemporal dynamics of (b) the impurity-bath spin correlation function χz

l (t) and (c) the relative changes ofdensity in the left and right lead. At t ' 50, the density waves reach the ends of each lead. They return to the impurity site l = 0 at t ' 100,where the spin correlations passingly become ferromagnetic. When the density waves return to the impurity site at t ' 200 after the secondreflection at the lead ends at t ' 150, the density reproduces the initial homogeneous profile. The parameters are j = 0.4, VL = −VR = 0.25.System size if L = 100 for each lead.

with l = 1, 2, . . . , L. Our formalism in Sec. II can be appliedby identifying the bath Hamiltonian hlm as the following two-lead matrix h2:

h2 =

(h1 + eVLIL+1 0

0 h1 + eVRIL+1

), (54)

where we recall that h1 is the single-lead hopping matrixgiven in Eq. (40). The coupling matrix gγlm is given by thelocal two-lead Kondo coupling:

gγ = J

(1 11 1

)⊗ diagL+1(1, 0, ..., 0), (55)

where diagd(v) denotes a d×d diagonal matrix with elementsv. Using Eqs. (54) and (55), together with the general expres-sion of the functional derivative (35), we solve the variationalreal-time evolution (26) to study the out-of-equilibrium dy-namics and transport properties.

B. Quench dynamics

To analyze transport phenomena, we prepare the initialstate

|Ψ(0)〉 = | ↑〉imp|FS〉L|FS〉R, (56)

where |FS〉L,R are the half-filled Fermi sea of each lead and,at time t = 0, we drive the system to out of equilibrium bysuddenly coupling the impurity and applying bias potentialsVL = V/2 and VR = −V/2. We then calculate the real-timeevolution by integrating Eq. (26). Without loss of generality,we choose a bias V > 0 so that the current initially takes apositive value (particles flow from the the left to right lead).

The black solid curve in Fig. 6(a) shows the time evolutionof the current I(t) flowing between the two leads:

I(t)= ieJ

4~

[〈σimp · c†0Lασαβ c0Rβ〉 − h.c.

]= −eJ

2~Im

[σximpσ

xαβ(Γf )0Lα,0Rβ

+(−iσy + σximpσz)αβ(ΓP

f )0Lα,0Rβ

],(57)

where we recall that 〈· · · 〉 is an expectation value with re-spect to wavefunction in the original frame, and we put back

curre

nt

time

Figure 7. Time evolutions of the current I(t) after the quench forvarious bias potentials V . After transient dynamics, all the currentsreach their steady values that are shown as the black dashed lines.The current is plotted in unit of eth/h. The dimensionless Kondocoupling is j = 0.4 and we set a bias potential V = V0 + ∆V/2with ∆V = 0.01 and vary V0 = 0, 0.1, · · · , 1.1 from the bottom totop. System size is L = 100 for each lead.

11

~ when the current and conductance are under consideration.After a short transient dynamics, the current quickly reachesa steady value and forms a plateau in the time evolution. Therelaxation time here is characterized by the time scale of theKondo-singlet formation, which is roughly equal to the decay-ing time of the magnetization (blue chain curve in Fig. 6(a)).

Figure 6(b) shows the spatiotemporal development of theimpurity-bath spin correlation χzl (t), which clearly indicatesthe formation of the Kondo cloud. Figure 6(c) shows the cor-responding spatiotemporal dynamics of the changes in densityrelative to the initial value. After the quench, density wavespropagate ballistically and eventually reach the ends of leads.Then, the reflected waves come back to the impurity site atthe middle of the time evolution. This associates with thesudden flip of the current and recurrence of the magnetiza-tion (Fig. 6(a)). Also, the spin correlation passingly becomesferromagnetic at this moment (Fig. 6(b)). After the secondreflections at the ends of leads, the density in both leads turnback to the initial value as shown in Fig. 6(c). These resultsdemonstrate the ability of our variational method to accuratelycalculate long-time spatiotemporal dynamics, which is chal-lenging to obtain in the previous approaches. As we considerthe global quench protocol, the system acquires an extensiveamount of energy relative to the ground state and thus theamount of entanglement can grow significantly in time. Thisseverely limits the applicability of, e.g., DMRG calculationsin the long-time regime [87]. The predicted spatiotemporaldynamics can be readily tested with site-resolved measure-ments by quantum gas microscopy [1–4, 131–133].

C. Magnetic effects

To further check that our approach captures the essentialfeature of the transport phenomena in the two-lead Kondomodel, we study the conductance behavior under a magneticfield. For a given bias V0, we calculate the current I(t) and itstime-averaged steady value I . We then determine the differ-ential conductance G by calculating I for slightly modulated

z

(b)

mag

netiz

atio

n

(a)

timemagnetic field h

cond

ucta

nce

G[e

/h]

2

Figure 8. (a) The differential conductance G (in unit of e2/h) isplotted against a magnetic field hz for different bias potentials V .(b) Time evolution of the impurity magnetization 〈σz

imp(t)〉 after thequench under a finite magnetic field hz . The parameters are j =0.35, V = 0.8 in (b), and system size is L = 100 for each lead.

bias V

curre

nt I

Figure 9. The current-bias characteristics with different strengthsof magnetic field hz . The dashed black line indicates the perfectconductance with I/V = 2e2/h. The current is plotted in unit ofeth/h. The parameters are j = 0.35 and V = 0.8. System size isL = 100 for each lead.

biases V = V0 ±∆V as follows:

G(V0) ' I(V0 + ∆V )− I(V0 −∆V )

2∆V. (58)

We plot the typical time-evolutions of the currents relaxingto their steady values for various bias potentials V in Fig. 7.Figure 8(a) shows the conductance behavior against magneticfield hz for zero and finite bias potentials. In the absenceof bias, applying a magnetic field hz larger than the Kondotemperature TK eventually destroys the Kondo singlet andmonotonically diminishes the conductance (black circles). Incontrast, with a finite bias potential V , it has a peak aroundhz = V at which the level matching between the fermi sur-faces in the two leads occurs. Importantly, peak values of theconductance are less than the unitarity limit 2e2/h since themagnetic field partially destroys the Kondo singlet as inferredfrom nonzero impurity magnetizations shown in Fig. 8(b).

We also plot the current-bias characteristics for differentstrengths of applied magnetic field in Fig. 9. As we increasethe magnetic field, the current-bias curve deviates from theperfect linear characteristics (black dashed line) due to thepartial breaking of the Kondo singlet. For fixed hz , as we in-crease the bias V , the slope of the current-bias curve becomesincreasingly sharper as long as the magnetic field remains be-low the resonance hz < V . These characteristic features ofthe conductance under the magnetic field are consistent withprevious findings in the Anderson model [84, 95] and analyt-ical results at the Toulouse point [106].

V. CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

Motivated by the original ideas by Tomonaga [33] andLee, Low and Pines [34], we have developed an efficient andversatile theoretical approach for analyzing the ground-stateproperties and out-of-equilibrium dynamics of quantum spin-impurity systems. A key idea of this approach is to introduce

12

a canonical transformation that decouples the impurity fromthe bath degrees of freedom such that the impurity dynam-ics is completely frozen in the transformed frame. We obtainthis transformation using the conserved parity operator, whichcorresponds to the discrete symmetry of the spin-impurityHamiltonians. By combining the canonical transformationwith Gaussian wavefunctions for the fermionic bath, we ob-tain a family of variational states that can represent nontrivialcorrelations between the impurity spin and the bath. In the ac-companying paper [109], we have provided strong evidencethat our approach correctly captures the nontrivial ground-state and out-of-equilibrium properties in spin-impurity prob-lems. In this paper, we provide the complete details of ourvariational method and benchmarked its accuracy by compar-ing to the results obtained with the MPS approach. Further-more, we have analyzed out-of-equilibrium dynamics of thetwo-lead Kondo model in further detail by calculating its long-time spatiotemporal dynamics and studying the influence ofthe magnetic field on the conductance.

Let us summarize the key advantages of the proposed the-oretical approach. Firstly, this approach is versatile and canbe applied to generic spin-impurity models, including sys-tems with long-range spin-bath interactions and disorder. Thecanonical transformation that we used relies only on the ex-istence of the elemental parity symmetry, and Gaussian statescan be used to describe both the fermionic and bosonic baths.The simplicity of our variational approach can provide newphysical insight into fundamental properties of challengingimpurity problems. Secondly, our method can be used topredict spatiotemporal dynamics of the total system includingboth impurity and bath in long-time regimes, which were chal-lenging to explore in the previous approaches [107, 108]. Thiscapability allows us to reveal new types of out-of-equilibriumphenomena in SIM, e.g., non-trivial crossovers in the long-time dynamics which originate from the nonmonotonic RGflows of equilibrium systems [109]. Thirdly, we note remark-able efficiency of our approach, since we achieve accuracycomparable to the MPS-based method using several orders ofmagnitude fewer variational parameters. This suggests thatour variational states can represent nontrivial impurity-bathcorrelations in a very compact way. Finally, in contrast toseveral previous methods, our approach can be used withoutrelying on the bosonization, which requires introducing a cut-off energy and using a strictly linear dispersion. This advan-tage is particularly important in view of recent developmentsof simulating quantum dynamics such as in ultracold atoms

[1–5, 131–142] and quantum dots [6–10] which allow quan-titative comparison between theory and experiments on bothshort and long time scales.

Our variational approach can be generalized in severalways. Owing to its versatility, the proposed approach canbe straightforwardly generalized to multi-channel systems[9, 26, 143], disordered systems [144], interacting bath suchas the Kondo-Hubbard models [145], and long-range interact-ing systems [146, 147] as typified by the central spin problem[31] that is relevant to nano-electronic devices such as quan-tum dots [30]. Another promising direction is a generaliza-tion to bosonic systems [148–151], which will be publishedelsewhere. Our approach can be also extended to study drivensystems and quantum pumping. Most of the previous works inthis direction were restricted to noninteracting electrons [152–155]. In this paper, we focused on the pure Gaussian state torepresent coherent dynamics of an isolated system at the zerotemperature. Generalizing our method to Gaussian densitymatrices will make it possible to explore finite temperaturesystems [156–158] and, together with the variational princi-ple for master equations [159, 160], to study Markovian openquantum systems subject to dissipation [161–164] or contin-uous measurements [165–168]. Extending our approach tomultiple impurities [169–172] would allow for studying themost challenging problems in many-body physics like com-peting orders in strongly correlated fermions [173] and con-finement in lattice gauge theories [174, 175]. We hope thatour work stimulates further studies in these directions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Carlos Bolech Gret, Adrian E. Feiguin,Shunsuke Furukawa, Vladimir Gritsev, Masaya Nakagawaand Achim Rosch for fruitful discussions. Y.A. acknowledgessupport from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciencethrough Program for Leading Graduate Schools (ALPS) andGrant No. JP16J03613, and Harvard University for hospital-ity. T.S. acknowledges the Thousand-Youth-Talent Programof China. J.I.C. is supported by the ERC QENOCOBA un-der the EU Horizon 2020 program (grant agreement 742102).E.D. acknowledges support from Harvard-MIT CUA, NSFGrant No. DMR-1308435, AFOSR Quantum SimulationMURI, AFOSR grant number FA9550-16-1-0323, the Hum-boldt Foundation, and the Max Planck Institute for QuantumOptics.

[1] M. Endres, M. Cheneau, T. Fukuhara, C. Weitenberg,P. Schauß, C. Gross, L. Mazza, M. C. Banuls, L. Pollet,I. Bloch, and S. Kuhr, Science 334, 200 (2011).

[2] M. Cheneau, P. Barmettler, D. Poletti, M. Endres, P. Schauss,T. Fukuhara, C. Gross, I. Bloch, C. Kollath, and S. Kuhr,Nature 481, 484 (2012).

[3] T. Fukuhara, S. Hild, J. Zeiher, P. Schauß, I. Bloch, M. Endres,and C. Gross, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 035302 (2015).

[4] A. M. Kaufman, M. E. Tai, A. Lukin, M. Rispoli, R. Schittko,

P. M. Preiss, and M. Greiner, Science 353, 794 (2016).[5] L. Riegger, N. Darkwah Oppong, M. Hofer, D. Rio Fernandes,

I. Bloch, and S. Folling, arXiv:1708.03810 (2017).[6] S. De Franceschi, R. Hanson, W. G. van der Wiel, J. M. Elz-

erman, J. J. Wijpkema, T. Fujisawa, S. Tarucha, and L. P.Kouwenhoven, Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 156801 (2002).

[7] H. E. Tureci, M. Hanl, M. Claassen, A. Weichsel-baum, T. Hecht, B. Braunecker, A. Govorov, L. Glazman,A. Imamoglu, and J. von Delft, Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 107402

13

(2011).[8] C. Latta, F. Haupt, M. Hanl, A. Weichselbaum, M. Claassen,

W. Wuester, P. Fallahi, S. Faelt, L. Glazman, J. von Delft, H. E.Tureci, and A. Imamoglu, Nature 474, 627 (2011).

[9] Z. Iftikhar, S. Jezouin, A. Anthore, U. Gennser, F. D. Parmen-tier, A. Cavanna, and F. Pierre, Nature 526, 233 (2015).

[10] M. M. Desjardins, J. J. Viennot, M. C. Dartiailh, L. E. Bruhat,M. R. Delbecq, M. Lee, M.-S. Choi, A. Cotter, and T. Kontos,Nature 545, 71 (2017).

[11] J. Kondo, Prog. Theor. Phys. 32, 37 (1964).[12] K. Andres, J. E. Graebner, and H. R. Ott, Phys. Rev. Lett. 35,

1779 (1975).[13] A. C. Hewson, The Kondo problem to heavy fermions (Cam-

bridge Univ. Press, Cambridge New York, 1997).[14] H. v. Lohneysen, A. Rosch, M. Vojta, and P. Wolfle, Rev.

Mod. Phys. 79, 1015 (2007).[15] P. Gegenwart, Q. Si, and F. Steglich, Nature Phys. 4, 186

(2008).[16] Q. Si and F. Steglich, Science 329, 1161 (2010).[17] L. Glazman and M. Raikh, JETP Lett. 47, 452 (1988).[18] T. K. Ng and P. A. Lee, Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 1768 (1988).[19] Y. Meir, N. S. Wingreen, and P. A. Lee, Phys. Rev. Lett. 70,

2601 (1993).[20] W. Liang, M. P. Shores, M. Bockrath, J. R. Long, and H. Park,

Nature 417, 725 (2002).[21] L. H. Yu and D. Natelson, Nano Lett. 4, 79 (2004).[22] D. Goldhaber-Gordon, J. Gores, M. A. Kastner, H. Shtrikman,

D. Mahalu, and U. Meirav, Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5225 (1998).[23] S. M. Cronenwett, T. H. Oosterkamp, and L. P. Kouwenhoven,

Science 281, 540 (1998).[24] F. Simmel, R. H. Blick, J. P. Kotthaus, W. Wegscheider, and

M. Bichler, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 804 (1999).[25] W. G. van der Wiel, S. D. Franceschi, T. Fujisawa, J. M. Elzer-

man, S. Tarucha, and L. P. Kouwenhoven, Science 289, 2105(2000).

[26] R. M. Potok, I. G. Rau, H. Shtrikman, Y. Oreg, andD. Goldhaber-Gordon, Nature 446, 167 (2007).

[27] A. V. Kretinin, H. Shtrikman, D. Goldhaber-Gordon, M. Hanl,A. Weichselbaum, J. von Delft, T. Costi, and D. Mahalu, Phys.Rev. B 84, 245316 (2011).

[28] A. V. Kretinin, H. Shtrikman, and D. Mahalu, Phys. Rev. B85, 201301 (2012).

[29] A. J. Leggett, S. Chakravarty, A. T. Dorsey, M. P. A. Fisher,A. Garg, and W. Zwerger, Rev. Mod. Phys. 59, 1 (1987).

[30] D. Loss and D. P. DiVincenzo, Phys. Rev. A 57, 120 (1998).[31] W. Zhang, N. Konstantinidis, K. A. Al-Hassanieh, and V. V.

Dobrovitski, J. Phys. Cond. Matt. 19, 083202 (2007).[32] A. Georges, G. Kotliar, W. Krauth, and M. J. Rozenberg, Rev.

Mod. Phys. 68, 13 (1996).[33] S. Tomonaga, Prog. Theor. Phys. 2, 6 (1947).[34] T. D. Lee, F. E. Low, and D. Pines, Phys. Rev. 90, 297 (1953).[35] J. T. Devreese and A. S. Alexandrov, Rep. Prog. Phys. 72,

066501 (2009).[36] J. T. Devreese, arXiv:1012.4576 (2010).[37] A. S. Alexandrov, Polarons in advanced materials (Canopus

Pub., 2007).[38] R. P. Feynman, Phys. Rev. 97, 660 (1955).[39] J. Bardeen, G. Baym, and D. Pines, Phys. Rev. 156, 207

(1967).[40] P. Nagy, J. Phys. Cond. Matt. 2, 10573 (1990).[41] W.-M. Zhang, D. H. Feng, and R. Gilmore, Rev. Mod. Phys.

62, 867 (1990).[42] T. Altanhan and B. S. Kandemir, J. Phys. Cond. Matt. 5, 6729

(1993).

[43] J. Tempere, W. Casteels, M. K. Oberthaler, S. Knoop, E. Tim-mermans, and J. T. Devreese, Phys. Rev. B 80, 184504 (2009).

[44] A. Novikov and M. Ovchinnikov, J. Phys. B 43, 105301(2010).

[45] W. Casteels, T. Van Cauteren, J. Tempere, and J. T. Devreese,Laser Phys. 21, 1480 (2011).

[46] W. Casteels, J. Tempere, and J. T. Devreese, Phys. Rev. A 84,063612 (2011).

[47] S. P. Rath and R. Schmidt, Phys. Rev. A 88, 053632 (2013).[48] J. Vlietinck, J. Ryckebusch, and K. Van Houcke, Phys. Rev.

B 87, 1 (2013).[49] J. Vlietinck, W. Casteels, K. Van Houcke, J. Tempere,

J. Ryckebusch, and J. T. Devreese, New J. Phys. , 9 (2014).[50] W. Li and S. Das Sarma, Phys. Rev. A 90, 013618 (2014).[51] F. Grusdt, Y. E. Shchadilova, a. N. Rubtsov, and E. Demler,

Sci. Rep. 5, 12124 (2015).[52] Y. E. Shchadilova, F. Grusdt, A. N. Rubtsov, and E. Demler,

Phys. Rev. A 93, 043606 (2016).[53] Y. E. Shchadilova, R. Schmidt, F. Grusdt, and E. Demler,

Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 113002 (2016).[54] Y. Ashida, R. Schmidt, L. Tarruell, and E. Demler,

arXiv:1701.01454 (2017).[55] P. Anderson, J. Phys. C 3, 2436 (1970).[56] K. G. Wilson, Rev. Mod. Phys. 47, 773 (1975).[57] R. Bulla, N.-H. Tong, and M. Vojta, Phys. Rev. Lett. 91,

170601 (2003).[58] L. Borda, Phys. Rev. B 75, 041307 (2007).[59] R. Bulla, T. A. Costi, and T. Pruschke, Rev. Mod. Phys. 80,

395 (2008).[60] H. Saberi, A. Weichselbaum, and J. von Delft, Phys. Rev. B

78, 035124 (2008).[61] L. Borda, M. Garst, and J. Kroha, Phys. Rev. B 79, 100408

(2009).[62] C. A. Busser, G. B. Martins, L. Costa Ribeiro, E. Vernek, E. V.

Anda, and E. Dagotto, Phys. Rev. B 81, 045111 (2010).[63] N. Kawakami and A. Okiji, Phys. Lett. A 86, 483 (1981).[64] N. Andrei, K. Furuya, and J. H. Lowenstein, Rev. Mod. Phys.

55, 331 (1983).[65] P. Schlottmann, Phys. Rep. 181, 1 (1989).[66] T. L. Schmidt, P. Werner, L. Muhlbacher, and A. Komnik,

Phys. Rev. B 78, 235110 (2008).[67] P. Werner, T. Oka, and A. J. Millis, Phys. Rev. B 79, 035320

(2009).[68] M. Schiro and M. Fabrizio, Phys. Rev. B 79, 153302 (2009).[69] P. Werner, T. Oka, M. Eckstein, and A. J. Millis, Phys. Rev. B

81, 035108 (2010).[70] G. Cohen, E. Gull, D. R. Reichman, A. J. Millis, and E. Ra-

bani, Phys. Rev. B 87, 195108 (2013).[71] P. Nordlander, M. Pustilnik, Y. Meir, N. S. Wingreen, and

D. C. Langreth, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 808 (1999).[72] A. Kaminski, Y. V. Nazarov, and L. I. Glazman, Phys. Rev. B

62, 8154 (2000).[73] A. Hackl and S. Kehrein, Phys. Rev. B 78, 092303 (2008).[74] M. Keil and H. Schoeller, Phys. Rev. B 63, 180302 (2001).[75] M. Pletyukhov, D. Schuricht, and H. Schoeller, Phys. Rev.

Lett. 104, 106801 (2010).[76] A. Hackl, D. Roosen, S. Kehrein, and W. Hofstetter, Phys.

Rev. Lett. 102, 196601 (2009).[77] A. Hackl, M. Vojta, and S. Kehrein, Phys. Rev. B 80, 195117

(2009).[78] C. Tomaras and S. Kehrein, Europhys. Lett. 93, 47011 (2011).[79] S. Bera, A. Nazir, A. W. Chin, H. U. Baranger, and S. Florens,

Phys. Rev. B 90, 075110 (2014).[80] S. Florens and I. Snyman, Phys. Rev. B 92, 195106 (2015).

14

[81] Z. Blunden-Codd, S. Bera, B. Bruognolo, N.-O. Linden, A. W.Chin, J. von Delft, A. Nazir, and S. Florens, Phys. Rev. B 95,085104 (2017).

[82] S. R. White and A. E. Feiguin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 076401(2004).

[83] P. Schmitteckert, Phys. Rev. B 70, 121302 (2004).[84] K. A. Al-Hassanieh, A. E. Feiguin, J. A. Riera, C. A. Busser,

and E. Dagotto, Phys. Rev. B 73, 195304 (2006).[85] L. G. G. V. Dias da Silva, F. Heidrich-Meisner, A. E. Feiguin,

C. A. Busser, G. B. Martins, E. V. Anda, and E. Dagotto,Phys. Rev. B 78, 195317 (2008).

[86] A. Weichselbaum, F. Verstraete, U. Schollwock, J. I. Cirac,and J. von Delft, Phys. Rev. B 80, 165117 (2009).

[87] F. Heidrich-Meisner, A. E. Feiguin, and E. Dagotto, Phys.Rev. B 79, 235336 (2009).

[88] F. Heidrich-Meisner, I. Gonzalez, K. A. Al-Hassanieh, A. E.Feiguin, M. J. Rozenberg, and E. Dagotto, Phys. Rev. B 82,205110 (2010).

[89] H. T. M. Nghiem and T. A. Costi, Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 156601(2017).

[90] F. B. Anders and A. Schiller, Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 196801(2005).

[91] F. B. Anders and A. Schiller, Phys. Rev. B 74, 245113 (2006).[92] F. B. Anders, R. Bulla, and M. Vojta, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,

210402 (2007).[93] F. B. Anders, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 066804 (2008).[94] D. Roosen, M. R. Wegewijs, and W. Hofstetter, Phys. Rev.

Lett. 100, 087201 (2008).[95] J. Eckel, F. Heidrich-Meisner, S. G. Jakobs, M. Thorwart,

M. Pletyukhov, and R. Egger, New J. Phys. 12, 043042(2010).

[96] B. Lechtenberg and F. B. Anders, Phys. Rev. B 90, 045117(2014).

[97] M. Nuss, M. Ganahl, E. Arrigoni, W. von der Linden, andH. G. Evertz, Phys. Rev. B 91, 085127 (2015).

[98] B. Dora, M. A. Werner, and C. P. Moca, Phys. Rev. B 96,155116 (2017).

[99] F. Lesage, H. Saleur, and S. Skorik, Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3388(1996).

[100] F. Lesage and H. Saleur, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 4370 (1998).[101] A. Schiller and S. Hershfield, Phys. Rev. B 58, 14978 (1998).[102] D. Lobaskin and S. Kehrein, Phys. Rev. B 71, 193303 (2005).[103] R. Vasseur, K. Trinh, S. Haas, and H. Saleur, Phys. Rev. Lett.

110, 240601 (2013).[104] S. Ghosh, P. Ribeiro, and M. Haque, J. Stat. Mech. Theor.

Exp. 2014, P04011 (2014).[105] M. Medvedyeva, A. Hoffmann, and S. Kehrein, Phys. Rev. B

88, 094306 (2013).[106] C. J. Bolech and N. Shah, Phys. Rev. B 93, 085441 (2016).[107] A. Rosch, Eur. Phys. J. B 85, 6 (2012).[108] U. Schollwock, Ann. Phys. 326, 96 (2011).[109] Y. Ashida, T. Shi, M.-C. Banuls, J. I. Cirac, and E. Demler,

arXiv:1801.05825 .[110] G. Zarand and J. von Delft, Phys. Rev. B 61, 6918 (2000).[111] C. Weedbrook, S. Pirandola, R. Garcıa-Patron, N. J. Cerf, T. C.

Ralph, J. H. Shapiro, and S. Lloyd, Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 621(2012).

[112] J. Mitroy, S. Bubin, W. Horiuchi, Y. Suzuki, L. Adamow-icz, W. Cencek, K. Szalewicz, J. Komasa, D. Blume, andK. Varga, Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 693 (2013).

[113] C. V. Kraus and J. I. Cirac, New J. Phys. 12, 113004 (2010).[114] R. Jackiw and A. Kerman, Phys. Lett. A 71, 1 (1979).[115] P. Kramer, J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 99, 012009 (2008).[116] T. Shi, E. Demler, and J. I. Cirac, arXiv:1707.05902 (2017).

[117] F. Verstraete, V. Murg, and J. I. Cirac, Adv. Phys. 57, 143(2008).

[118] K. Yosida, Phys. Rev. 147, 223 (1966).[119] C. M. Varma and Y. Yafet, Phys. Rev. B 13, 2950 (1976).[120] G. Bergmann and L. Zhang, Phys. Rev. B 76, 064401 (2007).[121] C. Yang and A. E. Feiguin, Phys. Rev. B 95, 115106 (2017).[122] S. R. White, Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2863 (1992).[123] F. Verstraete, D. Porras, and J. I. Cirac, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93,

227205 (2004).[124] G. Vidal, Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 147902 (2003).[125] G. Vidal, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 040502 (2004).[126] A. J. Daley, C. Kollath, U. Schollwock, and G. Vidal, J. Stat.

Mech. Theor. Exp. 2004, P04005 (2004).[127] B. Pirvu, V. Murg, J. I. Cirac, and F. Verstraete, New J. Phys.

12, 025012 (2010).[128] H. F. Trotter, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 10, 545 (1959).[129] M. Suzuki, J. Math. Phys. 26, 601 (1985).[130] F. Verstraete, J. J. Garcıa-Ripoll, and J. I. Cirac, Phys. Rev.

Lett. 93, 207204 (2004).[131] M. Miranda, R. Inoue, Y. Okuyama, A. Nakamoto, and

M. Kozuma, Phys. Rev. A 91, 063414 (2015).[132] Y. Ashida and M. Ueda, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 095301 (2015).[133] R. Yamamoto, J. Kobayashi, T. Kuno, K. Kato, and Y. Taka-

hashi, New J. Phys. 18, 023016 (2016).[134] A. Recati, P. O. Fedichev, W. Zwerger, J. von Delft, and

P. Zoller, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 040404 (2005).[135] D. Pekker, M. Babadi, R. Sensarma, N. Zinner, L. Pollet,

M. W. Zwierlein, and E. Demler, Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 050402(2011).

[136] J. Bauer, C. Salomon, and E. Demler, Phys. Rev. Lett. 111,215304 (2013).

[137] Y. Nishida, Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 135301 (2013).[138] Y. Nishida, Phys. Rev. A 93, 011606 (2016).[139] M. Nakagawa and N. Kawakami, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 165303

(2015).[140] R. Zhang, Y. Cheng, H. Zhai, and P. Zhang, Phys. Rev. Lett.

115, 135301 (2015).[141] R. Zhang, D. Zhang, Y. Cheng, W. Chen, P. Zhang, and

H. Zhai, Phys. Rev. A 93, 043601 (2016).[142] M. Kanasz-Nagy, Y. Ashida, T. Shi, C. P. Moca, T. N.

Ikeda, S. Folling, , J. I. Cirac, G. Zarand, and E. Demler,arXiv:1801.01132 .

[143] Z.-q. Bao and F. Zhang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 187701 (2017).[144] E. Miranda, V. Dobrosavljevic, and G. Kotliar, J. Phys. Cond.

Matt. 8, 9871 (1996).[145] H. Tsunetsugu, M. Sigrist, and K. Ueda, Rev. Mod. Phys. 69,

809 (1997).[146] K. S. Kleinbach, F. Meinert, F. Engel, W. J. Kwon, R. Low,

T. Pfau, and G. Raithel, Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 223001 (2017).[147] F. Camargo, R. Schmidt, J. D. Whalen, R. Ding, G. Woehl, Jr.,

S. Yoshida, J. Burgdorfer, F. B. Dunning, H. R. Sadeghpour,E. Demler, and T. C. Killian, arXiv:1706.03717 (2017).

[148] G. M. Falco, R. A. Duine, and H. T. C. Stoof, Phys. Rev. Lett.92, 140402 (2004).

[149] S. Florens, L. Fritz, and M. Vojta, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 036601(2006).

[150] M. Foss-Feig and A. M. Rey, Phys. Rev. A 84, 053619 (2011).[151] T. Flottat, F. Hebert, V. G. Rousseau, R. T. Scalettar, and G. G.

Batrouni, Phys. Rev. B 92, 035101 (2015).[152] F. Romeo and R. Citro, Phys. Rev. B 80, 165311 (2009).[153] R. Citro, F. Romeo, and N. Andrei, Phys. Rev. B 84, 161301

(2011).[154] M. Diez, A. M. R. V. L. Monteiro, G. Mattoni, E. Cobanera,

T. Hyart, E. Mulazimoglu, N. Bovenzi, C. W. J. Beenakker,

15

and A. D. Caviglia, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 016803 (2015).[155] Y. Peng, Y. Vinkler-Aviv, P. W. Brouwer, L. I. Glazman, and

F. von Oppen, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 267001 (2016).[156] T. A. Costi, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1504 (2000).[157] R. Bulla, T. A. Costi, and D. Vollhardt, Phys. Rev. B 64,

045103 (2001).[158] P.-H. Chou, L.-J. Zhai, C.-H. Chung, C.-Y. Mou, and T.-K.

Lee, Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 177002 (2016).[159] J. Cui, J. I. Cirac, and M. C. Banuls, Phys. Rev. Lett. 114,

220601 (2015).[160] H. Weimer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 040402 (2015).[161] A. J. Daley, Adv. Phys. 63, 77 (2014).[162] G. Barontini, R. Labouvie, F. Stubenrauch, A. Vogler, V. Guar-

rera, and H. Ott, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 035302 (2013).[163] R. Labouvie, B. Santra, S. Heun, and H. Ott, Phys. Rev. Lett.

116, 235302 (2016).[164] T. Tomita, S. Nakajima, I. Danshita, Y. Takasu, and Y. Taka-

hashi, Sci. Adv. 3, e1701513 (2017).[165] H. Carmichael, An Open System Approach to Quantum Optics

(Springer, Berlin, 1993).[166] T. E. Lee and C.-K. Chan, Phys. Rev. X 4, 041001 (2014).[167] Y. Ashida, S. Furukawa, and M. Ueda, Nat. Commun. 8,

15791 (2017).[168] Y. S. Patil, S. Chakram, and M. Vengalattore, Phys. Rev. Lett.

115, 140402 (2015).[169] C. Jayaprakash, H. R. Krishna-murthy, and J. W. Wilkins,

Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 737 (1981).[170] B. A. Jones and C. M. Varma, Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 843 (1987).[171] A. Georges and Y. Meir, Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3508 (1999).[172] R. Zitko and J. Bonca, Phys. Rev. B 74, 045312 (2006).[173] M. Vojta, Y. Zhang, and S. Sachdev, Phys. Rev. B 62, 6721

(2000).[174] K. G. Wilson, Phys. Rev. D 10, 2445 (1974).[175] J. Kogut and L. Susskind, Phys. Rev. D 11, 395 (1975).

![Page 1: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

![Page 2: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/2.jpg)

![Page 3: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/3.jpg)

![Page 4: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/4.jpg)

![Page 5: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/5.jpg)

![Page 6: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/6.jpg)

![Page 7: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/7.jpg)

![Page 8: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/8.jpg)

![Page 9: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/9.jpg)

![Page 10: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/10.jpg)

![Page 11: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/11.jpg)

![Page 12: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/12.jpg)

![Page 13: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/13.jpg)

![Page 14: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/14.jpg)

![Page 15: arXiv:1802.03861v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 12 Feb 2018cmt.harvard.edu/demler/PUBLICATIONS/ref279.pdf · Variational principle for quantum impurity systems in and out of equilibrium: application](https://reader039.fdocuments.us/reader039/viewer/2022031003/5b85ffab7f8b9ad1318bfcf1/html5/thumbnails/15.jpg)

![arXiv:0808.0496v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 4 Aug 2008 Physical ...qpt.physics.harvard.edu/p185.pdf · Edge and impurity response in two-dimensional quantum antiferromagnets Max A. Metlitski](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/611bd77962489878e372c03a/arxiv08080496v1-cond-matstr-el-4-aug-2008-physical-qpt-edge-and-impurity.jpg)